Abstract

In the human-centered research on automated driving, it is common practice to describe the vehicle behavior by means of terms and definitions related to non-automated driving. However, some of these definitions are not suitable for this purpose. This paper presents an ontology for automated vehicle behavior which takes into account a large number of existing definitions and previous studies. This ontology is characterized by an applicability for various levels of automated driving and a clear conceptual distinction between characteristics of vehicle occupants, the automation system, and the conventional characteristics of a vehicle. In this context, the terms ‘driveability’, ‘driving behavior’, ‘driving experience’, and especially ‘driving style’, which are commonly associated with non-automated driving, play an important role. In order to clarify the relationships between these terms, the ontology is integrated into a driver-vehicle system. Finally, the ontology developed here is used to derive recommendations for the future design of automated driving styles and in general for further human-centered research on automated driving.

1. Introduction

Both globalization and urbanization lead to a rapid increase in traffic volume and present global challenges for existing mobility systems [1]. In contrast, automation of mobility offers the potential to enhance traffic efficiency, traffic safety, and the driving comfort of drivers [2]. Automated driving has been developed at various automation levels, whereby the dynamic driving task is incrementally transmitted from the driver to the automation system [3]. While the vehicle assumes the role of an automatic machine and performs the respective driving task independently, the driver can take on an observer role and intervene in the driving process if necessary [4]. In contrast to lower automation levels, such as partially (SAE level 2) and conditionally (SAE level 3) automated driving, such intervention and observation is not necessary during highly automated driving (SAE level 4) in specific operational design domains and during fully automated driving (SAE level 5) [3].

Many terms used to describe vehicle guidance, such as ‘driving style’ [5], ‘driving behavior’ [6], ‘driving experience’ [7], and ‘driveability’ [8], are based on non-automated driving. The definitions of these terms have been modified in recent years by various researchers (e.g., [9,10,11,12,13,14]). In general, definitions of terms are neither incorrect nor correct, but are possibly not suitable for one specific research purpose or another [15].

In the human-centered research on automated driving, it is common practice to conduct studies on automated vehicle behavior (e.g., [16,17,18,19,20]) and in this process, to use various definitions related to non-automated driving (e.g., [5,12]). However, some of these definitions are not suitable for automated driving. In particular, there is currently no solution for the conceptual distinction between the driving style of an automated vehicle and the driving style of a driver, so that the same definitions are used in the community for different characteristics of driver-vehicle systems. For this reason, this paper aims to choose, customize, and create suitable definitions of various terms and compile them into a coherent ontology for automated vehicle behavior. Ontologies are used in computer science and philosophy to describe the world and parts of it, and thus contribute to a common understanding [21]. In this paper, the ontology is intended to resolve the aforementioned confusion and disagreement about describing automated vehicle behavior and provide a basis for future research publications.

In the following, automated vehicle behavior is seen as part of the dynamic human–machine interface (dHMI) [22] and includes all aspects of information perception and processing, and in particular the resulting way an automated vehicle drives. Due to the effects on the driving comfort [17], the consideration of automated vehicle behavior in relation to the vehicle occupants is classified as being quite relevant for further research on automated driving. Thus, appropriate dynamic driving parameters, such as proper vehicle velocities and accelerations [23], along with cooperative driving styles [24], can contribute to enhanced driving comfort and play an important part in this paper. In addition to the vehicle, the intended ontology takes into account the vehicle occupants.

2. Method

In this section, the method for developing an ontology for automated vehicle behavior is presented and divided into three parts. Initially, a review of previous human-centered research on automated vehicle behavior was carried out and design recommendations for the behavior were summarized. This review served to identify terms and definitions that are commonly used to describe automated vehicle behavior in the relevant literature. In order to ensure the validity of this review, only studies published in either scientific journals or conference proceedings and that had at least twenty participants [25] were considered. For the same reason, studies performed in a vehicle, dynamic driving simulator, or fixed-base driving simulator were taken into account.

In the second step, the terms frequently used in the review to describe automated vehicle behavior were examined in more detail. Therefore, a comprehensive literature search based primarily on the Google Scholar database and the keywords ‘driving style’, ‘driving behavior’, ‘driving experience’, and ‘driveability’ was performed by the authors. Common definitions of these terms are explained in Section 4, and we evaluated the extent to which they are suitable for usage in the intended ontology. In consideration of the defined objective of this paper, the following requirements were placed on the ontology and the definitions:

- With regard to the various levels of driving automation [3], the ontology should cover the entire spectrum from assisted driving (SAE level 1) to fully automated driving.

- The ontology should include a conceptual distinction between the characteristics of vehicle occupants and those of the automated vehicle.

- As a basis for further research, the ontology should allow a reproducible description of driving styles of automated vehicles, independent of the vehicle’s software and hardware.

In the third step, suitable definitions for the ontology are selected in consideration of the preceding evaluation and, if necessary, customized or redefined. However, it should be ensured that there is an obvious coherence between the classic meanings of the terms and the customized definitions. Based on this, the chosen definitions were compiled into a coherent ontology with the help of a driver-vehicle system.

3. Review

This section presents a review of human-centered research on automated vehicle behavior. Particular attention is paid to how the automated vehicle behavior is usually described and to design recommendations. Since the expectations of potential customers should not be ignored in the development of automated driving [9], these are also briefly listed in the following. Therefore, the driving comfort and perceived safety of highly automated [26] and future vehicles in general [27] are elementary aspects of these expectations. Furthermore, system reliability [26], environmental compatibility, and suitability for everyday use [27] are considered important. In addition, Schoettle and Sivak [28] indicated that potential customers prefer to observe the traffic during highly automated driving or to engage in non-driving related tasks, such as reading.

Lange [29] (p. 39 et seq.) summarized the common vehicle dynamics particularly for non-automated driving and concluded how automated vehicle dynamics have to be designed to be accepted. In line with this, ten recommendations for longitudinal accelerations from −3.5 to 2.3 m/s2, lateral accelerations from 0.7 to 1.3 m/s2, and the duration of lane changes from 1.7 to 6.5 s are presented. ISO 15622 [30] presents further suggestions for assisted driving, such as a maximum longitudinal acceleration of 2 m/s2 and a minimum selectable time headway of 0.8 s. Furthermore, reference is made to a doctoral thesis [31] which recommends a selectable time headway from 0.6 to 2.0 s with the aim of increasing driving comfort. In comparison, the human perception threshold of longitudinal accelerations ranges between 0.02 and 0.8 m/s2 and the human perception threshold of lateral accelerations is in a range between 0.05 and 0.1 m/s2 [32].

In addition to Lange [29], Table 1 considers further studies which focus on variations of automated vehicle behavior and associated effects on the feeling of vehicle occupants. The study designs are described on the basis of the automation level referring to SAE J3016 [3], the study environment, the driving maneuver with the range of the velocity v, and the metrics used to evaluate the automated vehicle behavior. Some results of these studies and recommendations of the respective authors are presented on the basis of the following driving parameters: longitudinal time headway t, longitudinal acceleration a, longitudinal jerk j, duration of lane changes t, lateral acceleration a, and lateral jerk j.

Table 1.

Human-centered research on automated vehicle behavior in addition to [29] (p. 39 et seq.).

In the studies listed in Table 1, the description of automated vehicle behavior is based on the terms ‘driving style’ and rather ‘automated driving style’ (e.g., [16,17,19,35,37,38]). In a few cases ([16,17]), reference is thereby made to existing definitions used by Elander et al. [5] and Sagberg et al. [12], which, however, are not adapted to automated driving. In the other cases, the term ‘driving style’ is not defined further, but individual driving characteristics, such as velocity and acceleration (e.g., [19]), along with trajectories (e.g., [37]), are assigned to it. In addition to the description of automated vehicle behavior, the term ‘driving style’ is also used in some of the selected literature (e.g., [17,19,35,37,38]) to describe the driver’s way of driving. The term ‘experience’ is thereby mainly used to describe the perception and feeling of the vehicle occupants. Furthermore, the selected literature sporadically mentions the acceleration behavior (e.g., [17]), the trajectory behavior (e.g., [37]), the system behavior (e.g., [18]), and other specifications of the term ‘driving behavior’.

In addition to the literature mentioned in this review, there are further studies on human-centered design of the automated vehicle behavior. However, in several of these studies, the variations of automated driving styles are either explained incompletely or imprecisely (e.g., [39]), and thus are not considered in this section. The influence that weather conditions (e.g., [20]), the performance of non-driving related tasks (e.g., [16]), and various human characteristics, such as personality (e.g., [17]), age (e.g., [35]), and the individual human driving style (e.g., [19]), have on the evaluation of automated vehicle behavior has already been considered in several studies.

4. Definitions

The aforementioned review reveals that current human-centered research on automated vehicle behavior particularly uses the terms ‘driving style’, ‘driving behavior’, and ‘driving experience’. Accordingly, in this section, various definitions of these terms are discussed in more detail and the extent to which they are suitable for usage in the ontology is evaluated. In addition, the term ‘driveability’, which is based on non-automated driving [8], will also be discussed.

4.1. Driving Style

The term ‘driving style’ was already defined in 1993 by Elander et al. [5] (p. 279) with respect to non-automated driving:

“Driving style concerns the way individuals choose to drive or driving habits that have become established over a period of years. It includes choice of driving speed, threshold for overtaking, headway, and propensity to commit traffic violations.”

Due to these individual driving habits and characteristics, various drivers have several driving styles and react differently to driving situations [40]. Consequently, an individual driver can have different driving styles depending on time and environment [41]. Wu et al. [14] understand driving style to be how the driver performs the vehicle guidance in general and describe that other definitions of this term especially take the aggression of the driver into account. Based on an additional definition [13], the personal attitudes and beliefs concerning driving are attributed to the driving style. Sagberg et al. [12] reviewed the previous research and usage of the term ‘driving style’ and considered Elander et al. [5], among others. Based on this, the driving style is defined as the “habitual way of driving, which is characteristic for a driver or a group of drivers” [12] (p. 1251).

In addition, the term ‘driving style’ is also used in various studies to describe the way an automated vehicle drives (see Section 3). However, the term itself is not described any further. Only various driving parameters, such as accelerations, jerks, and headway distances [42], are assigned to the driving style. Griesche et al. [43] (p. 102) used the term ‘driving style’ for highly automated driving, “as a linguistic description of observable patterns of parameter sets related to the maneuver and trajectory planning level.”

4.2. Driving Behavior

Various definitions with different meanings are used for the ‘driving behavior’, that can be regarded as a generic term [12] or merely as individual characteristics [14] of driving styles. According to Wu et al. [14], the term ‘driving behavior’ solely considers the decisions of the driver, such as braking or accelerating. According to another definition [6], current velocities and accelerations are understood to be driving behavior, which varies greatly depending on gender [44], cultural parameters, and environmental conditions [45].

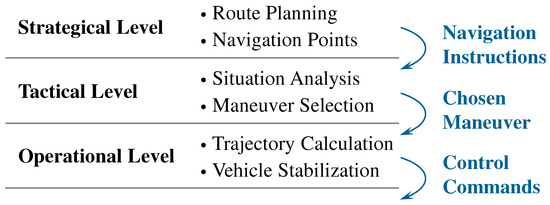

With respect to automated driving research, Lange [29] summarized the relevant literature ([46,47,48,49,50]) and clarified that an automation system consists of the subsystems perception and so-called ‘behavior generation’, whereby the latter is responsible for the driving task and can thus be divided into various levels (e.g., [51,52,53,54]). With regard to existing architectures of non-automated driving (e.g., [51]) and robotics (e.g., [55]), Matthaei [50] developed a hierarchical system architecture for automated vehicles (Figure 1). Referring to Matthaei [50] and Donges [51], the strategical level represents the highest hierarchical level and contains the route planning for the navigation of the vehicle.

Figure 1.

Components of the behavior generation referring to [50].

Depending on the perceived environment, appropriate driving maneuvers are derived from navigation instructions within the tactical level. Based on this, the target trajectory and thus the temporal and spatial target positions of the vehicle are calculated on the operational level and in combination with further information passed on to various vehicle controllers. Dynamic driving parameters, such as velocity of the vehicle, are therefore defined in this level. The respective driving trajectory is carried out by transferring the control commands to the vehicle’s motor, brake, and steering [50].

4.3. Driving Experience

Various parameters of driving style and behavior, such as velocity and acceleration, have significant effects on the driving experience [16]. The latter is defined as a complex feeling of the driver, which is derived from the interaction between himself and the vehicle, and is thus perceived subjectively [56]. A similar definition of driving experience was created by Bengler [9] (p. 80), who stated that this term “is especially focused on the experiences effected exactly by and during the negotiation of the driving task”.

With regard to automated driving, Kuoch et al. [57] and Martin et al. [58] report that the driving experience will change rapidly. Further information on the effects of automated vehicle behavior and individual driving parameters on the driving experience are summarized in the review in Section 3. The general concept of user experience is further explored for human-centered design for interactive systems in ISO 9241-210 [59].

In contrast to the previously presented definitions, other publications describe driving experiences as the length of time the driver has a driving license [7] and the number of driven kilometers [11]. According to this approach, an increase in driving experience is accompanied by an improvement of the driver’s driving skills [60].

4.4. Driveability

Based on Hurter [8], driveability refers to the reliability and running smoothness of the powertrain of a vehicle. In contrast, Mitschke and Wallentowitz [10] describe driveability as the vehicle reactions induced by the driver and external disturbances during driving curves. According to another definition [61], driveability represents the holistic behavior of a system comprising a driver, a vehicle, and the environment.

4.5. Evaluation of the Definitions

In conformity with the requirements mentioned in Section 2, an evaluation of the extent to which the existing definitions are suitable for the intended ontology is presented in the following. In line with Section 4.1, the term ‘driving style’ is variously defined for non-automated driving as the way a human drives, and for automated driving is used to describe how an automated vehicle drives. However, these definitions do not distinguish between the driving style as a characteristic of a human and as a characteristic of a vehicle. It follows that there is no uniform definition of the term ‘driving style’ for the entire spectrum of automated driving. For the development of the intended ontology, a redefinition of this term is considered useful.

Similarly to the term ‘driving style’, the term ‘driving behavior’ is mainly used to describe the way a human drives manually (see Section 4.2). In contrast, the term ‘behavior generation’ also has become established for automated driving. Due to various existing definitions for the behavior generation of automated vehicles, a customization of this term is not considered useful or necessary at this point. For the sake of completeness, the term ‘driving behavior’ is clarified in the context of automated driving for usage in the ontology.

As shown in Section 4.3, the term ‘driving experience’ is primarily used to describe the emotional state of drivers. Accordingly, it can be transferred to automated driving and all vehicle occupants.

Referring to Section 4.4, the term ‘driveability’ is especially used to describe the driving characteristics of a vehicle to various extents. Assuming that the automated driving style and driving behavior refer to the automation system of a vehicle, various definitions of driveability can still be used to describe further characteristics of automated vehicles that are independent of the automation system. In consideration of these circumstances, an existing definition of driveability is selected and extended in Section 5.2.

All in all, on the basis of a redefinition of the term ‘driving style’, a clarification of the term ‘driving behavior’, and extensions of existing definitions of the terms ‘driveability’ and ‘driving experience’, a holistic description of the automated vehicle behavior is expected.

5. Ontology for Automated Vehicle Behavior

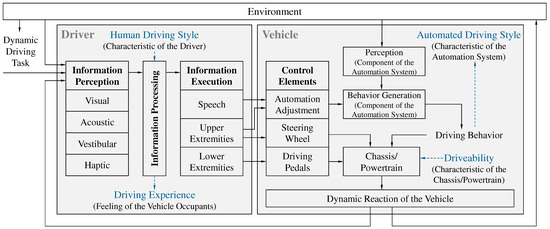

In consideration of the previous sections, an ontology for automated vehicle behavior is developed in the following and presented on the basis of a driver-vehicle system in Figure 2. With regard to the driver’s cognitive processes, the driver is represented by a partial cognitive driver model based on Bubb [62] (p. 333) and is classified into information perception, information processing, and information execution. While signal flows are marked by black arrows, influences are depicted by blue and dashed ones.

Figure 2.

Ontology for automated vehicle behavior referring to [5,10,50,56,62] (p. 333).

5.1. Redefinition of the Term Driving Style

In conformity with the aforementioned requirements for the ontology, both the driver and the automation system have to be considered. Accordingly, in addition to the classic ‘human driving style’, the term ‘automated driving style’ is also used, which describes how an automated vehicle drives and can therefore be classified as a characteristic of the automation system. The fundamental distinction between the human driving style and the automated driving style is evident in the driver-vehicle system shown in Figure 2. In the case of a cooperative vehicle guidance, such as the H-Mode, the driver can interact with the automation system [63] and thus the two driving styles merge to one driving style of the driver-vehicle system. Further definitions for cooperative vehicle guidance and the shared execution of the dynamic driving task by a human and an automated vehicle were clarified by Flemisch et al. [64]. Due to the fact that the driver takes over the role of a passenger during highly and fully automated driving [3], the human driving style becomes irrelevant under these circumstances.

In accordance with the second requirement for the ontology (see Section 2), the existing definition from Elander et al. [5] that is highlighted in Section 4.1 is expanded and customized for the automated driving style. This definition is selected for this purpose because of the frequent usage (e.g., [12,16,17,42]) and the transferability from a human to an automation system.

For human driving styles, the definition created by Elander et al. [5] and highlighted in Section 4.1 is retained and supplemented by all further parameters of the way of driving, such as the choice of driving maneuvers. The automated driving style is defined at this point by referring this definition not to the driver but to the vehicle’s automation system.

Due to the resulting consideration of the time, similarly to the human driving style [41], the automated driving style of a vehicle can therefore change over time. Automatic adaptions of automation systems are recommended for the entire dynamic driving task, with the exception of navigation [65]. Non-driving related tasks of the driver or different automation levels [3] might have an influence on the driving styles. This statement goes hand in hand with the recommendation of Oliveira et al. [38] that earlier versions of automated vehicles should drive human-like and be more conservative and in later versions drive more assertively and be progressive with regard to the acceptance of the system.

5.2. Extension of the Term Driveability

As a characteristic of the automation system, the automated driving style is independent of other hardware and software of the vehicle, and thus of the vehicle’s chassis and powertrain characteristics. For the description of these classic characteristics the term ‘driveability’ is suitable.

By extension of the definition by Mitschke and Wallentowitz [10] presented in Section 4.4, driveability is defined as the vehicle reactions induced by the driver, external circumstances, and the automation system. In addition to this definition, all driving situations and not only driving curves are considered in terms of driveability at this point.

5.3. Clarification of the Term Driving Behavior

In contrast to the automated driving style, which, according to Section 5.1, describes all aspects of automated driving and can thus be described subjectively by individual adjectives, such as comfortable or economic, the driving behavior refers to the purely objective output of the behavior generation. The latter is referring to Matthaei’s hierarchical system architecture for automated vehicles [50] responsible for navigation and route planning, for situation analysis and maneuver selection, and for trajectory calculation and vehicle stabilization.

Driving behavior is defined as the direct control commands for the automated dynamic driving task that result from the behavior generation. Accordingly, the driving behavior includes instructions for vehicle actuators, such as steering and braking systems, and results in the automated driving style of the vehicle.

The studies summarized in Table 1 provide fundamental recommendations on how to design a human-centered driving behavior and indicate that subsequent kinematic output parameters, such as positions, velocities, and accelerations, are of high importance. Furthermore, it can be seen that a suitable driving behavior depends on the environment, the driving maneuver, and the metrics used to evaluate the automated vehicle behavior. A possible adjustment of the behavior generation by, for example, the driver’s upper extremities, can result in an adaption of the driving behavior and thus in a variation of the automated driving style. This issue is shown in Figure 2 and enables the automated vehicle behavior to be adapted to the individual needs of the vehicle occupants.

5.4. Extension of the Term Driving Experience

Taking into account the definitions already presented and the aim of a general and holistic description of automated vehicle behavior, Schöggl’s [56] definition of driving experience is considered appropriate as a basis for the extension.

Driving experience describes the complex feeling of the driver that results from the interaction between himself and the vehicle [56]. With a view to the adoption of the partial or complete dynamic driving task by the automation system depending on the automation level [3], driving experience at this point is related to all vehicle occupants and not only to the driver.

According to this customized definition, ‘driving experience’ is regarded as a generic term that can be described in more detail by further metrics, such as driving comfort and driving pleasure. Referring to Naujoks et al. [66], interactions between the driver and the vehicle, and thus the perceived trust and usability, are mainly influenced by the human–machine interface (HMI). This suggests that in general, the latter has a significant influence on the driving experience.

At this point, it is important to note that vehicle occupants may have different expectations about the automated vehicle or perceive the automated vehicle behavior differently (see Section 3). It follows that the driving experience of vehicle occupants can differ (see Section 4.3). A more detailed discussion of this issue and the implications for recommended designs of automated driving styles follow in Section 6.3.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper, the development of an ontology for automated vehicle behavior was explained using a 3-part method. In the following, the review presented in Section 3, which served as a fundamental preparation for the development of the ontology, is discussed. In addition, the developed ontology is explained in more detail and, based on this, recommendations for the further research on automated driving styles are derived.

6.1. Human-Centered Research on Automated Vehicle Behavior

The review listed in Section 3 points out that human-centered research on automated vehicle behavior was focused mainly on individual parameters of the direct longitudinal and lateral vehicle dynamics. Accordingly, the effects of different driving dynamics on driving experience were investigated in particular. In this process, various terms are used to describe the automated vehicle behavior, which are not defined or only incompletely defined. In addition, definitions are used which are basically suitable for non-automated driving and have not been adapted for automated driving. In particular, the term ‘driving style’ is often but also very differently used in the literature. Furthermore, in several studies, the exact variations of automated driving styles and how the vehicle really behaves are not described in detail, which may reduce the reproducibility of studies and the validity of the results.

On the basis of this review, the problem to be solved, which was already defined in Section 1, could be clarified and relevant terms for the ontology identified. However, it must be critically stated that despite an extensive literature search, it cannot be guaranteed that all relevant publications were considered in the aforementioned review and in the subsequent evaluation of the selected terms (see Section 4). On the other hand, this approach and the summarized information are considered appropriate and sufficient as a basis for the development of an ontology.

6.2. Ontology for Automated Vehicle Behavior

The ontology developed in this paper and shown in Figure 2 is characterized by various features. In accordance with the requirements defined in Section 2, the ontology was designed to be suitable for various levels of automated driving and to provide a conceptual distinction between driver and vehicle characteristics. Accordingly, there is a clear difference between an automated driving style as a characteristic of the automation system of the vehicle and the human driving style as a characteristic of the driver. Furthermore, within the automation system, a distinction was made between the objective driving behavior and the subjective automated driving style, which should enable a description of the latter independent of the automation implementation. However, the authors recommend further investigations to describe automated driving styles independently of the vehicle’s hardware and software. In addition, the ontology uses the term ‘driveability’ to distinguish between the classic characteristics of the chassis and powertrain, and the characteristics of the automation system.

In summary, the ontology takes into account various aspects of the automated vehicle guidance and provides an expedient way of describing automated vehicle behavior through the usage of suitable definitions. Nevertheless, further influencing factors that should not be disregarded in designing automated driving styles, such as pedestrians, surrounding vehicles, and other characteristics of the environment, were not considered in detail. However, this issue does not affect the validity and applicability of the ontology created in this paper and the definitions it contains. Therefore, the ontology can be used to emphasize various recommendations for future and customer-oriented automated driving styles.

6.3. Recommendations for Automated Driving Styles

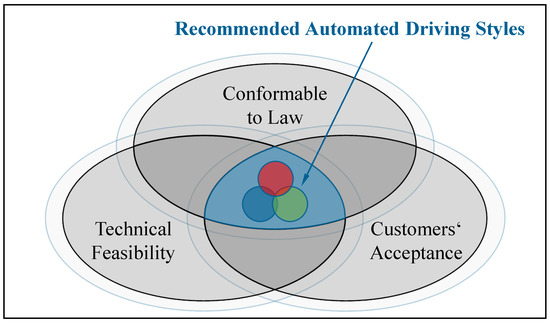

Figure 2 shows that automated driving styles are generated, influenced, and technically limited by the preceding behavior generation and perception capabilities, such as limited sensor ranges of the automation system. However, there are also various customer requirements and expectations (see Section 3) that have to be met by automated driving styles. As presented in Figure 3, automated driving styles should therefore be included in the intersection of technically feasible automated driving styles and those desired and particularly accepted by potential customers. In addition, regulatory requirements and standards have to be considered [9], and can thus contribute to safe traffic. According to this, relevant system limitations, such as maximum accelerations and minimum distances to other objects, should be specified by official guidelines and ensured by the vehicle manufacturers. Due to technical progress and possible changes in customer and regulatory requirements, the transitions in Figure 3 are depicted as being smooth.

Figure 3.

Recommendations for automated driving styles.

As indicated in Section 3, evaluation of automated driving styles depends on human characteristics, such as age (e.g., [35]) and personality traits (e.g., [17]). Moreover, the acceptance of automated vehicles, which represents a fundamental condition for the success of automated driving [67], is also influenced by the specific driver’s mental model of the automation system [68]. In addition to acceptance and comfort frequently mentioned in Table 1, the holistic driving experience should be considered in the process of developing automated driving styles. In particular, aspects resulting from the automation of the dynamic driving task, such as performance of non-driving related tasks and associated motion sickness [69], should not be neglected. To meet as many individual customer requirements as possible, we recommend, along with other researchers (e.g., [16,35,39,70]), to offer options to individualize the automated vehicle behavior and thus to implement diverse automated driving styles in automated vehicles (see three colored areas in Figure 3). According to various authors, human driving styles are often subdivided, among others, into calm, normal, and aggressive [71]; or conservative, moderate, and aggressive [72]. Previous research has revealed that a part of the population wants to be driven differently from their human driving styles (e.g., [73]), which is why transferring human driving styles to automated driving styles should be questioned. Accordingly, we recommend a distinction between human-like and machine-like automated driving styles.

With respect to safe and efficient traffic, the design of automated driving styles should not be based solely on the human-centered perspective of a specific driver-vehicle system. Accordingly, in order to achieve an optimum of the entire traffic, the environment and thus other road users should also be considered in the development of automated driving styles.

6.4. Conclusions

Taking into account a large amount of relevant literature, numerous definitions, and the international standard SAE J3016 [3], an ontology for automated vehicle behavior was developed. SAE J3016 [3] addresses the description of the automated vehicle behavior itself merely in a cursory manner. Our ontology focuses especially on the applicability for different levels of automated driving and a strict separation of characteristics of an automated vehicle and vehicle occupants.

To summarize, the ontology contributes to a clear description of the vehicle behavior of assisted, partially automated, conditionally automated, highly automated, and fully automated vehicles, along with the interactions between the driver and the vehicle. Therefore, the ontology is suitable for human-centered research on automated driving and can be used as a basis for further investigations in this field. Consequently, this paper contributes to a standardization of the description of automated vehicle behavior. The clarification of a fact that according to Busse et al. [21] represents the central objective of an ontology is accordingly fulfilled by the developed one. The suitability of the ontology for more general fields of automated driving, such as marketing or politics, is also considered possible by the authors. However, the suitability for these purposes cannot be guaranteed without further investigations by experts in the respective fields.

In future, experimental validation of the ontology and included terms should also be addressed. Consequently, it is necessary to investigate how driving behavior can be quantified and described clearly on the basis of technical and kinematic parameters, such as accelerations, torques, forces, and the resulting trajectory. Furthermore, the developed ontology can be used to evaluate how and to what extent automated driving styles can be described independently of the vehicle’s hardware and software. A greater reproducibility of studies and more general research purposes could be the result. In addition to the characteristics of the vehicle, the metrics that can be used to describe the driving experience in a holistic way should also be investigated in the future. Due to individual feelings and expectations about automated driving, future studies should increasingly consider the characteristics of vehicle occupants and thus various personas.

Furthermore, the authors recommend that in the future, automated vehicle dynamics should not be only examined separately. The question of how various driving maneuvers have to be carried out automatically in order to achieve a positive driving experience should be extended by the question regarding accepted and desired moments for specific maneuvers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.O. and S.C.; methodology, J.O. and S.C.; investigation, J.O.; data curation, J.O.; writing—original draft preparation, J.O.; writing—review and editing, J.O., S.C., and K.B.; visualization, J.O.; supervision, S.C. and K.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by AUDI AG.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks are due to Alexander Lange for the assistance in the methodological work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- VDA. Automatisiertes Fahren 2018. Available online: https://www.vda.de/de/themen/innovation-und-technik/automatisiertes-fahren/automatisiertes-fahren.html (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Gasser, T.M.; Schmidt, E.A.; Bengler, K.; Chiellino, U.; Diederichs, F.; Eckstein, L.; Flemisch, F.; Fraedrich, E.; Fuchs, E.; Gustke, M.; et al. Bericht zum Forschungsbedarf: Runder Tisch Automatisiertes Fahren–AG Forschung 2015. Available online: https://www.bmvi.de/SharedDocs/DE/Anlage/DG/Digitales/bericht-zum-forschungsbedarf-runder-tisch-automatisiertes-fahren.html (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- SAE. Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles–J3016; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bubb, H.; Bengler, K.; Grünen, R.E.; Vollrath, M. (Eds.) Automobilergonomie; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elander, J.; West, R.; French, D. Behavioral Correlates of Individual Differences in Road-Traffic Crash Risk: An Examination of Methods and Findings. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 113, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, I.M. The Effects of Driving Style and Vehicle Performance on the Real-World Fuel Consumption of U.S. Light-Duty Vehicles. Master’s Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rochon, J.; Swain, L.; O’Hara, S. Exposure to the Risk of an Accident: A Review of the Literature, and the Methodology for the Canadian Study; Transport Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1978.

- Hurter, D.A. A Study of Technological Improvements in Automobile Fuel Consumption Volume II: Comprehensive Discussion; U.S. Department of Transportation: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974.

- Bengler, K. Driver and Driving Experience in Cars. In Automotive User Interfaces; Meixner, G., Müller, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Mitschke, M.; Wallentowitz, H. Dynamik der Kraftfahrzeuge, 5th ed.; VDI-Buch, Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothengatter, T.; Alm, H.; Kuiken, M.J.; Michon, J.A.; Verwey, W.B. The driver. In Generic Intelligent Driver Support; Michon, J.A., Ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1993; pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sagberg, F.; Selpi; Piccinini, G.F.B.; Engström, J. A Review of Research on Driving Styles and Road Safety. Hum. Factors 2015, 57, 1248–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Akamatsu, M. Development of an Interference System for Drivers’ Driving Style and Workload Sensitivity from their Demographic Characteristics. In Advances in Human Aspects of Transportation Part III; Stanton, N., Landry, S., Di Bucchianico, G., Vallicelli, A., Eds.; AHFE Conference: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Li, H.; Ding, H.; Zhang, L. Who Has Better Driving Style: Let Data Tell Us. In Intelligent Systems and Applications. IntelliSys 2019. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Bi, Y., Bhatia, R., Kapoor, S., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bänsch, A.; Alewell, D. Wissenschaftliches Arbeiten, 11th ed.; Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH: München, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Festner, M.; Eicher, A.; Schramm, D. Beeinflussung der Komfort- und Sicherheitswahrnehmung beim hochautomatisierten Fahren durch fahrfremde Tätigkeiten und Spurwechseldynamik. In 11. Workshop Fahrerassistenzsysteme und Automatisiertes Fahren; Uni-DAS e.V.: Darmstadt, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bellem, H.; Thiel, B.; Schrauf, M.; Krems, J.F. Comfort in automated driving: An analysis of preferences for different automated driving styles and their dependence on personality traits. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 55, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, A.; Maas, M.; Albert, M.; Siedersberger, K.H.; Bengler, K. Automatisiertes Fahren – So komfortabel wie möglich, so dynamisch wie nötig. In 30. VDI/VW-Gemeinschaftstagung Fahrerassistenz und Integrierte Sicherheit; VDI Verlag: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, S.; Schubert, D.; Dettmann, A.; Hartwich, F.; Bullinger, A.C. Wie will der “Fahrer” automatisiert gefahren werden? Überprüfung verschiedener Fahrstile hinsichtlich des Komforterlebens. In 32. VDI/VW-Gemeinschaftstagung Fahrerassistenzsysteme und Automatisiertes Fahren; VDI Verlag: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Siebert, F.W.; Wallis, F.L. How speed and visibility influence preferred headway distances in highly automated driving. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 64, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, J.; Humm, B.; Lübbert, C.; Moelter, F.; Reibold, A.; Rewald, M.; Schlüter, V.; Seiler, B.; Tegtmeier, E.; Zeh, T. Was bedeutet eigentlich Ontologie? Informatik-Spektrum 2014, 37, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengler, K.; Rettenmaier, M.; Fritz, N.; Feierle, A. From HMI to HMIs: Towards an HMI Framework for Automated Driving. Information 2020, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, S.; Dettmann, A.; Hartwich, F.; Pech, T.; Bullinger, A.C.; Wanielik, G. How the driver wants to be driven—Modelling driving styles in highly automated driving. Paper Presented at 7. Tagung Fahrerassistenz, München, Germany, 25–26 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Dolan, J.M.; Litkouhi, B. Autonomous Vehicle Social Behavior for Highway Entrance Ramp Management. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Gold Coast City, QLD, Australia, 23–26 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, A.; Neumann, M.; Brockmann, M.; Walz, R.; Winkle, T. Code of Practice for the Design and Evaluation of ADAS 2009. Available online: http://www.acea.be/publications/article/code-of-practice-for-the-design-and-evaluation-of-adas (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Simon, K.; Jentsch, M.; Bullinger, A.C.; Meincke, E.; Schamber, G. Sicher aber langweilig? Auswirkungen vollautomatisierten Fahrens auf den erlebten Fahrspaß. Z. Arbeitswissenschaft 2015, 69, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AutoScout24 GmbH. Unser Auto von Morgen 2015: Einschätzungen, Wünsche und Visionen 2015. Available online: http://about.autoscout24.com/de-de/au-press/2015_as24_studie_auto_v_morgen.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Schoettle, B.; Sivak, M. Public Opinion about Self-Driving Vehicles in China, India, Japan, the U.S., the U.K., and Australia; Technical Report No. UMTRI-2014-30; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, A. Gestaltung der Fahrdynamik beim Fahrstreifenwechselmanöver als Rückmeldung für den Fahrer beim automatisierten Fahren. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Munich, München, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. Intelligent Transport Systems—Adaptive Cruise Control Systems—Performance Requirements and Test Procedures, 15622:2010; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hoedemaeker, M. Driving with intelligent vehicles: Driving behaviour with Adaptive Cruise Control and the acceptance by individual drivers. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft University Press, Delft, The Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Heißing, B.; Kudritzki, D.; Schindlmaister, R.; Mauter, G. Menschengerechte Auslegung des dynamischen Verhaltens von PKW. In Ergonomie und Verkehrssicherheit; Bubb, H., Ed.; Herbert Utz Verlag: München, Germany, 2000; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Siebert, F.W.; Oehl, M.; Pfister, H.R. The influence of time headway on subjective driver states in adaptive cruise control. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2014, 25, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, F.W.; Oehl, M.; Bersch, F.; Pfister, H.R. The exact determination of subjective risk and comfort thresholds in car following. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2017, 46, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festner, M.; Baumann, H.; Schramm, D. Der Einfluss fahrfremder Tätigkeiten und Manöverlängsdynamik auf die Komfort-und Sicherheitswahrnehmung beim hochautomatisierten Fahren. In 32. VDI/VW-Gemeinschaftstagung Fahrerassistenzsysteme und Automatisiertes Fahren; VDI Verlag: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, S.; Blenk, T.; Albert, M.; Sauer, D. Evaluation of different driving styles during conditionally automated highway driving. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Europe Chapter 2019 Annual Conference; de Waard, D., Toffetti, A., Pietrantoni, L., Franke, T., Petiot, J.F., Dumas, C., Botzer, A., Onnasch, L., Milleville, I., Mars, F., Eds.; HFES: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.hfes-europe.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/CramerBlenk2019.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Rossner, P.; Bullinger, A.C. Do You Shift or Not? Influence of Trajectory Behaviour on Perceived Safety During Automated Driving on Rural Roads. In HCI in Mobility, Transport, and Automotive Systems. LNCS 11596; Krömker, H., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, L.; Proctor, K.; Burns, C.G.; Birrell, S. Driving Style: How Should an Automated Vehicle Behave? Information 2019, 10, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossner, P.; Bullinger, A.C. How Do You Want to be Driven? Investigation of Different Highly-Automated Driving Styles on a Highway Scenario. In Advances in Human Factors of Transportation. AISC 964; Stanton, N., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.W.; Fang, C.Y.; Tien, C.T. Driving behaviour modelling system based on graph construction. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2013, 26, 314–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Xi, J. Statistical-based approach for driving style recognition using Bayesian probability with kernel density estimation. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 13, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellem, H.; Schönenberg, T.; Krems, J.F.; Schrauf, M. Objective metrics of comfort: Developing a driving style for highly automated vehicles. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2016, 41, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesche, S.; Krähling, M.; Käthner, D. CONFORM – A visualization tool and method to classify driving styles in context of highly automated driving. In 30. VDI/VW-Gemeinschaftstagung Fahrerassistenz und Integrierte Sicherheit; VDI Verlag: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2014; pp. 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Li, K.; Lu, X.Y. Effect of Human Factors on Driver Behavior. In Advances in Intelligent Vehicles; Chen, Y., Li, L., Eds.; Academic Press: Kidlington, UK, 2014; pp. 111–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wang, M.; Duan, L. Letting Drivers Know What is Going on in Traffic. In Advances in Intelligent Vehicles; Chen, Y., Li, L., Eds.; Academic Press: Kidlington, UK, 2014; pp. 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardelt, M.; Coester, C.; Kaempchen, N. Highly Automated Driving on Freeways in Real Traffic Using a Probabilistic Framework. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2012, 13, 1576–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.R.; Dolan, J.M. A Case Study in Behavioral Subsystem Engineering for the Urban Challenge. IEEE/RAM Special Issue on Software Engineering in Robotics. 2008. Available online: https://www.ri.cmu.edu/pub_files/2009/3/ram2008-FinalSubmission.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Bartels, A.; Berger, C.; Krahn, H.; Rumpe, B. Qualitätsgesicherte Fahrentscheidungsunterstützung für automatisches Fahren auf Schnellstraßen und Autobahnen. In 10. Braunschweiger Symposium Automatisierungssysteme, Assistenzsysteme und Eingebettete Systeme für Transportmittel; GZVB: Braunschweig, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hohm, A.; Lotz, F.; Fochler, O.; Lueke, S.; Winner, H. Automated Driving in Real Traffic: From Current Technical Approaches towards Architectural Perspectives; SAE Technical Paper 2014-01-0159; SAE: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthaei, R.W.H. Wahrnehmungsgestützte Lokalisierung in fahrstreifengenauen Karten für Assistenzsysteme und automatisches Fahren in urbaner Umgebung. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University Braunschweig, Braunschweig, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Donges, E. Aspekte der Aktiven Sicherheit bei der Führung von Personenkraftwagen. Automobil-Industrie 1982, 27, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer, M. Flexible Automatisierung von Straßenfahrzeugen mit Rechnersehen. Ph.D. Thesis, Bundeswehr University Munich, Neubiberg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, J.; Bender, P.; Schreiber, M.; Lategahn, H.; Strauss, T.; Stiller, C.; Dang, T.; Franke, U.; Appenrodt, N.; Keller, C.G.; et al. Making Bertha Drive—An Autonomous Journey on a Historic Route. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2014, 6, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donges, E. Fahrerverhaltensmodelle. In Handbuch Fahrerassistenzsysteme; Winner, H., Hakuli, S., Lotz, F., Singer, C., Eds.; Springer Vieweg: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015; pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzberg, J.; Lingemann, K.; Nüchter, A. Mobile Roboter: Eine Einführung aus Sicht der Informatik; Springer Vieweg: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöggl, P. Objektivierung und Optimierung der Fahrbarkeit im Fahrzeug und am dynamischen Prüfstand. In Subjektive Fahreindrücke Sichtbar Machen; Becker, K., Ed.; Expert Verlag: Renningen-Malmsheim, Germany, 2000; pp. 122–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kuoch, S.K.; Nowakowski, C.; Hottelart, K.; Reilhac, P.; Escrieut, P. Designing an Intuitive Driving Experience in a Digital World. Preprints 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, H.; Tschabuschnig, K.; Bridal, O.; Watzenig, D. Functional Safety of Automated Driving Systems: Does ISO 26262 Meet the Challenges? In Automated Driving; Watzenig, D., Horn, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 387–416. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction—Part 210: Human-Centred Design for Interactive Systems, 9241-210:2010; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Abendroth, B.; Bruder, R. Capabilities of Humans for Vehicle Guidance. In Handbook of Driver Assistance Systems; Winner, H., Hakuli, S., Lotz, F., Singer, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zomotor, A. Fahrwerktechnik: Fahrverhalten, 1st ed.; Vogel Buchverlag: Würzburg, Germany, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bubb, H. Informationswandel durch das System. In Ergonomie; Schmidtke, H., Ed.; Carl Hanser Verlag: München, Germany, 1993; pp. 333–390. [Google Scholar]

- Flemisch, F.O.; Bengler, K.; Bubb, H.; Winner, H.; Bruder, R. Towards cooperative guidance and control of highly automated vehicles: H-Mode and Conduct-by-Wire. Ergonomics 2014, 57, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemisch, F.; Abbink, D.A.; Itoh, M.; Pacaux-Lemoine, M.P.; Weßel, G. Joining the blunt and the pointy end of the spear: Towards a common framework of joint action, human–machine cooperation, cooperative guidance and control, shared, traded and supervisory control. Cogn. Technol. Work 2019, 21, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentsch, M.; Roßner, P.; Missbach, A.; Bullinger, A.C. Adaptivität oder Adaptierbarkeit im Fahrzeug – Leitfaden und Konzepte zur optimalen Fahrerunterstützung. In 61. Frühjahrskongress der Gesellschaft für Arbeitswissenschaft; GfA: Dortmund, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Naujoks, F.; Hergeth, S.; Wiedemann, K.; Schömig, N.; Forster, Y.; Keinath, A. Test procedure for evaluating the human-machine interface of vehicles with automated driving systems. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2019, 20, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhoff, S.; Kyriakidis, M.; van Arem, B.; Happee, R. A multi-level model on automated vehicle acceptance (MAVA): A review-based study. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci. 2019, 20, 682–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beggiato, M.; Krems, J.F. The evolution of mental model, trust and acceptance of adaptive cruise control in relation to initial information. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2013, 18, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, T. Motion Sickness in Automated Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on Advanced Vehicle Control (AVEC’16); Edelmann, J., Plöchl, M., Pfeffer, P.E., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Beggiato, M.; Hartwich, F.; Krems, J. Der Einfluss von Fahrermerkmalen auf den erlebten Fahrkomfort im hochautomatisierten Fahren. Automatisierungstechnik 2017, 65, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphey, Y.L.; Milton, R.; Kiliaris, L. Driver’s Style Classification Using Jerk Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Workshop on Computational Intelligence in Vehicles and Vehicular Systems, Nashville, TN, USA, 30 March–2 April 2009; pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedar-Dongarkar, G.; Das, M. Driver Classification for Optimization of Energy Usage in a Vehicle. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2012, 8, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwich, F.; Beggiato, M.; Krems, J.F. Driving comfort, enjoyment and acceptance of automated driving—Effects of drivers’ age and driving style familiarity. Ergonomics 2018, 61, 1017–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).