Abstract

This paper focuses on the crucial role played by Ifa Fuyū, the “father of Okinawan studies,” in articulating ideas related to Okinawan-Japanese identity. Starting with a brief overview of Ifa’s life and work, especially his pioneering work in Ryukyuan linguistics, the author observes how Ifa’s progressive and reformist perspective shapes his discourse on religion, language, and history. The author then moves into analyzing a recently discovered wartime article that Ifa wrote in 1945, when he learned in Tokyo that the battle of Okinawa broke out between Japan and the U.S. Ifa’s controversial article shows how a strong sense of nationalistic identity was imposed upon Okinawans, on the one hand, while also revealing Ifa’s intention to fight prejudice toward Okinawans, on the other. This leads to the broader context of Japan’s emergence as a “nation state.” Problematizing the question of identity, the author argues that alternative histories of Japan should be taken into account for its proper understanding. Comparing Ifa’s view with historian Amino Yoshihiko’s thesis on Japan and modernization, the author envisions how identity can be seen as a growing network of plural identities rather than an abstractly imagined monolithic identity.

1. Introduction

The life and work of Ifa Fuyū (1876–1947),1 the “father of Okinawan studies” (Okinawagaku no chichi), continue to garner attention in postwar Okinawa–Japan discourse. His pioneering work in Ryukyuan linguistics, history, folklore, art, and religion have gained considerable respect over the three-quarters of a century since they were first published. Considered a multifaceted thinker, and despite his well-deserved fame, Ifa’s reputation as a public intellectual has also been questioned in recent years. Kano Masanao, a renowned scholar of modern Japanese history, prefaces his study of Ifa Fuyū with a remark on the “prima facie ambiguous character of Ifa’s thought,” considering it “a reflection of the multilayered contradictions inherent to Okinawa’s modern times.”2

There is, however, little need to portray Ifa’s position as being shaped by a tragic and insolubly complex nature of Okinawan identity that Japan’s rapid modernization brought about after the Meiji Restoration in 1868. As we shall see below, Ifa was by and large a reformist thinker who gave prevalence to the modernist discourse over what belonged to history, since he believed people should not be fettered to the past, though he was not as simple-minded as to consider that the modern concept of national identity exhausts one’s identity either. Ifa was of the opinion that if an Okinawan-Japanese identity is to be sought for, it shall necessarily reveal a hybrid nature, a view that may carry significant implications for future visions of identity.

Born in Naha in 1876, Ifa grew up in a time of political and cultural assimilation.3 Japan’s annexation of the Ryukyus began in 1872. After seven years of domestic and diplomatic struggles, Okinawa prefecture replaced the Ryukyu Domain in 1879. Cultural, political, and educational reform followed to integrate Okinawa into Japan, ranging from changes in hairstyle and attire to the promotion of standard Japanese and State Shintoism. Ifa himself started to learn standard Japanese at age eleven in a primary school attached to Okinawa Prefectural Normal School. After being expelled from his middle school for participating in a student protest,4 Ifa moved to a private middle school in Tokyo. He graduated from Third Higher School in Kyoto, and in 1906 became the first Okinawan to graduate from Tokyo Imperial University, majoring in linguistics. Ifa’s early aspirations, however, gravitated more toward politics than linguistics.5

The linguistic training Ifa received at Tokyo Imperial University helped him unveil the ancient Ryukyuan world dimly transmitted through Omoro sōshi, a compilation of Ryukyuan poems, songs, and oracles, which he later collated and published in 1925. He not only deciphered a language that had become largely impenetrable by the end of the nineteenth century but also made a number of discoveries that linked the Ryukyuan language to the Japanese language.6 In particular Ifa accumulated concrete evidence that the Ryukyuan language contains a wealth of features closely identified with features of classical Japanese.7 He concluded that the Ryukyuan and Japanese languages branched off a common linguistic stem long before the Nara period (710–784 CE), a view supported broadly by historical linguists today.8

Based on his research, Ifa often said that the Japanese and Ryukyuan languages were “sister languages” (shimai-go),9 and also held that the people of Okinawa were a “distant kin of the Japanese people” (Nihon minzoku no tōi wakare). Toward Japanese mainlanders, Ifa wished to appeal to commonality and equality so as to win their respect for Okinawans. As for the people of Okinawa, he wanted them to modernize and attain higher social and economic standards—in short, to “catch up” with mainlanders. From 1906 through 1925, Ifa offered over 360 public lectures on a variety of subjects, including psychology, genetics, public hygiene, education for women, Christianity, and so forth, in addition to drawing on his extensive repertoire in Ryukyuan studies. He always gave his talk in fluent dialect so that the local audience could understand. In this respect Ifa was not just a scholar but also a social reformer and a progressive community leader.10

2. Changing Social Institutions to Serve the People

Ifa’s characteristic way of thinking is revealed in a short essay he wrote in 1919. On Boys’ Day, 5 May, Ifa fondly described what he perceived as “the Okinawan philosophy of clothing” expressed in a traditional Okinawan verse, which his wife often sang to their young son. “Its intended meaning is,” Ifa writes, “Oh new clothes, falling apart at the seams and tattered when no longer needed; oh little child, do not worry about your clothes, outgrow them as you wish.”11 Ifa then continues:

A nation having institutions and organizations is the same as the body having clothes. As the “people,” the substance of the nation, start to develop, we need to reconstruct or abolish older institutions and organizations, and to adopt new ones, which is like remaking or selling off clothes to get new ones for the child to wear, when the clothes we got a year or two before are outgrown by the child. We ought to know that, when the substance has developed, and we do not recognize that the form that used to contain it is outdated, the form cannot help changing into a prison.12

The point Ifa makes is simple: Social institutions are functions of the society, which should continue to change in order to serve people—the “substance” of the nation—as opposed to the people serving the institutions. In Ifa’s view, this applies to religion as well. After spending much of his lifetime studying Omoro sōshi, Ifa did not maintain that Ryukyuan Shintoism, which was thought to retain old features of mainland Shintoism, should be preserved. Echoing the Marxist scholar Kawakami Hajime,13 Ifa wrote:

Any beautiful system, once it completes its mission, would have it as its own ideal to yield its position to a new system and disappear. On the contrary, if it exerts powerful influence after its usefulness is exhausted, it would be liable to changing into a prison and enslaving people. […] Viewed this way, it must be considered a natural outcome that Ryukyuan Shintoism, a politically necessary system and institution up to a certain time, successfully fulfilled its mission and declined, once the hearts and minds of the people became united and fused together.14

The latter half of the passage reflects the long and complex history of the second Shō Dynasty of the Ryukyu Kingdom (1470–1879), but the idea Ifa presents is general: Religion is a social function whose fate is to be determined by people, not the other way around.

By the same token, Ifa did not think that the Ryukyuan or Okinawan language should be preserved at all costs, though he was a historical linguist par excellence. “The national language (kokugo) is the respiration of the people (minzoku no kokyū),” Ifa once wrote, continuing: “The Omoro people likewise breathed in their language of miseseru [the religious language of Omoro rituals].”15 In this sense language is tantamount to the very life of people. Nevertheless it is the respiration of the people that should constitute the life of language. We are not subordinate to language: It is language that must live or die as people and society move forward. Ifa writes:

Observe how one language of a country changes under the influence of the language of another country. First the vocabulary, then pronunciation, and then idiomatic usage—changes take place in this order. One can tell how far the changes have gone in the Okinawan language over the last forty years from the fact that an older person around sixty or seventy now cannot understand the Okinawan language used by young people today. The Okinawan language is on its way to extinction. I do not see this as a pity. […] After all, language has its own life. When its mission is fulfilled, it is only natural that it disappears.16

In Ifa’s view, a language can die out when its life comes to an end. Given Japan’s modernization and changing relationship to the West, Ifa wrote: “I do not think that a long life is left to the Ryukyuan language. I am aware that my own Ryukyuan language is becoming old-fashioned. The Ryukyuan language is thus collapsing, but it cannot be helped.”17 It is noteworthy that a pioneering scholar of Ryukyuan religion and language is almost condoning their natural extinction, provided that they are not facing extinction by external coercion. The Australian linguist Hugh Clarke wrote that Ifa “felt that inevitably the local dialects would be replaced by standard language. While he saw no need to hasten the process, neither did he advocate trying to preserve the dialects.”18

3. Ifa Fuyū’s Perspective on the Past

It might appear counterintuitive that Ifa did not fight for the preservation of dialects. As a historical linguist, he knew that hundreds of languages had actually disappeared, some naturally, some as the result of oppression. Even an epidemic could cause a fatal decline in language users. However, whatever the situation is, Ifa suggested that we always consider people first, especially given the social, economic, and political situation of Okinawa. At the same time, it is worth noting that no social institution becomes extinct without leaving traces behind. In the case of language, old word forms, including phonetic variations and loan words, continue their lives into a modern language even after the original language they belonged to dies out. In agreement with other linguists, therefore, Ifa writes: “From this too we can see that language is not like bamboo shoots just growing into bamboo stems; it is more like numerous streams joining together as they rush forward, cumulating impurity upon impurity and fattening up.”19

In this connection it is interesting to see how Ifa reinforces his view with his remarks on the Japanese diaspora and the Japanese language in Hawai‘i. During his visit to the islands in 1928,20 Ifa observed that “the disappearance of the Japanese language in Hawai‘i is indeed a matter of time” and further argued that Americans “had better not arouse anxiety among the Japanese diaspora who made great contributions to the industrial development of Hawai‘i; instead they should wait for their children to dissolve into the social and ethnic melting pot.”21 What Ifa has in mind here is not only the simple fact that the Japanese language may not be spoken by second- and third-generation Japanese in Hawai‘i, but the much subtler fact that culture grows thicker even when one culture merges into another; the debris of a disappearing culture, including language and religion, fertilizes the soil for future growth in unexpected directions.

In Ifa’s view, any religion or philosophy that refuses to take on new forms in interaction with other traditions tends to become a prison for people. For example, Ifa observes that intellectuals in Okinawa had long been obsessed with the teachings of Zhuxi such that their minds became enslaved for centuries. After the annexation of the Ryukyus to Japan, Ifa believed that the people of Okinawa were finally exposed to a variety of thoughts:

Okinawans, after being slavishly devoted to Zhuxi’s doctrine for a few hundred years, have suddenly been introduced to a number of ways of thinking. They have now familiarized themselves with living Buddhism, with the teachings of Wang Yangming, Christianity, naturalism, and many other new ideas. Is this not a phenomenon that deserves celebration? Through exposure to so many ideas, it is abundantly clear that Okinawa, now and into the future, should produce individuals the likes of which have never been seen before. From where we stand today, the old Ryukyu Kingdom was certainly undernourished. If so, we must rather rejoice over the resuscitation of the Ryukyuan people following the dismantlement of the half-dead Ryukyu Kingdom.22

Note that it is the people of the Ryukyus, not the collapsing Kingdom, that Ifa concerns himself with in this passage. It was along these lines that Ifa Fuyū, the father of Okinawan studies, welcomed modern science, Christianity, and other ideas, tirelessly lecturing on new knowledge in addition to Ryukyuan themes. This might be regarded as part of his complexity—the prominent historian and linguist who studied the past in great depth was hardly fixed upon perpetuating the past.

Heralding the advent of the new field of Okinawan studies, Ifa became an eminent scholar who assembled thousands of historic Ryukyuan documents as the first director of Okinawa Prefectural Library. Through his intense work, a progressive, humanist, and scholarly image of Ifa Fuyū was established. A helpful summary pointing in this direction is found in historian George Oshiro’s words: “[Ifa Fuyū] probably continued to the end of his life to be concerned with humanistic values and goals. Thus, though he clearly sympathized with men such as Kawakami Hajime in their fight against authoritarianism and imperialism, Ifa himself did not play an active role in political issues and movements. In his last twenty years of life, after he returned from his lecture trip abroad [to Hawai‘i and mainland U.S.], he concentrated the greater part of his remaining energies to the furthering of his research on Okinawan and Ryukyuan culture.”23

4. The Discovery of a Wartime Article

In 2007 a different perspective emerged, when a researcher at the University of the Ryukyus, Isa Shin’ichi (1951–), discovered a short wartime newspaper article bearing Ifa’s name. Published in Tokyo Shimbun on April 3 and 4, 1945, under the opening title “Opportunity to Prove True Merit,” Ifa’s two-part article urges the people of Okinawa, or so it appears, to see the imminent battle of Okinawa as an opportunity to prove themselves loyal citizens of the Empire of Japan. The U.S. Navy had occupied the smaller Okinawan islands by 31 March 1945, and on April 1 began the invasion of the main island of Okinawa. On hearing the news in Tokyo, Ifa began the article with the following words:

The enemy has finally made a landing on the main island of Okinawa. Imagining how the Ryukyuan people, equipped with an intrepid nature, are now fighting ever so bravely in their beloved province that has become the battlefield, I have earnest feelings welling up in my heart. And I cannot help recalling the tense atmosphere that prevailed in Okinawa around the time of the First Sino-Japanese War when I was still in middle school.24

After reacting against the U.S. Navy’s landing in the first two opening sentences, Ifa’s narrative flashes back to his middle school experience in 1894, the year the First Sino-Japanese War broke out. Half a century earlier, Ifa was attending the Okinawa Prefectural Middle School where a volunteer corps was formed by students in response to rumors that China’s South Sea Fleet might attack Okinawa. The subtitle of the article, “Middle Schoolers Armed for the First Sino-Japanese War,” reflects this, while another small caption, “The Decisive Battlefield: Main Island of Okinawa,” resonates with the war propaganda that dominated the Japanese media at the time.

Before moving further into the article, however, it should be noted that what Ifa says here contains noticeable repetitions of his earlier publications. Although never clarified by Isa Shin’ichi, the discoverer of the wartime article, the core material of the first part of Ifa’s Tokyo Shimbun article had in fact appeared at least five times in print before 1945.25 The experience of being an “armed” middle schooler, for example, is recounted in Ifa’s well-known 1926 autobiographical essay, where he recollects in lighthearted words, “Every day we sharpened swords, prepared bullets, and conducted shooting and other military drills under the blazing sun …”26 Next in the newspaper article follows an anecdote about boating with school friends toward a flagship that appeared off the coast of Naha, which the same 1926 essay goes over in greater detail.27 A condensed sketch of Ryukyuan history from ancient times to the end of the Ryukyu Kingdom comes in four more sentences. The first half of the two-part article then closes with Ifa’s remark: “After the promulgation of the [Meiji] Constitution [in 1889], there was a period tinged with colonial colors [in Okinawa], but the Sino-Japanese War [1894–1895] made Ryukyus’ position definite, which decided its policy continuing into the present day. The opportunity has arrived to demonstrate its true merit.”

The second half of the two-part article opens with conversations Ifa held many years before with two military generals after the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), when Ifa was the director of the Okinawa Prefectural Library. These conversations formed part of Ifa’s 1915 essay,28 in which “Nagata,” one of the generals in the Tokyo Shimbun article, originally appeared as “Nagatani.” In both narratives, the two generals observe and admire the strong potential of Ryukyuan soldiers. In the wartime 1945 article, Ifa associates this with modern Japanese education, writing, “In my opinion what was greater and more valuable than sharing ethnicity and the blood burning with love for one’s homeland was the power of Japan’s national education.” He then returns to the approaching battle:

Up to the First Sino-Japanese War, pro-Japan groups consisted only of bureaucrats and middle school and normal school teachers, but thanks to the spread of standard Japanese and national education, the Ryukyus must now be uniting together as self-aware citizens of the Japanese Emperor, fiercely fighting against the enemy. The enemy has reduced Naha to dust and ashes through their recent extreme bombing, and has resolved to make an outrageous landing on the main island of Okinawa.

Until the First Sino-Japanese War came to an end, some Okinawans, especially descendants of the traditional ruling class, were pro-Chinese, reflecting the long tributary relationship that the Ryukyu Kingdom had maintained with China. Japan’s victory over China in 1895 resulted in a power shift. In Ifa’s view, modern education—including Japanization education (kōminka kyōiku)—gave Okinawans the opportunity to thrive in the new world, but it also imposed on them a strong sense of nationalistic identity, as indicated in Ifa’s wording “self-aware citizens of the Japanese Emperor.” After hinting at an infamous air raid of Naha in October of the previous year, Ifa closes the second part of the article with the following words:

Fortunately, our home province, blessed with a warm climate, is entering the taro harvest time. There is no worry over food shortages, and combined with the geographical advantage, nothing is lacking to crush the enemy’s ambition. I hold high expectations for Ryukyuans engaged in this brave fight where the graves of their forefathers lie.

The discovery of Ifa’s 1945 article stunned Ifa scholars and the Okinawan public to some extent as well. It was unexpected coming from Ifa Fuyū, widely revered as a progressive academic who dedicated much of his life to the study of Omoro sōshi. Had he been yet another unfortunate intellectual who ended up spreading war propaganda like other numerous journalists, literary critics, philosophers, and wartime Buddhists?29 Was Ifa’s mind more amenable to militarist slogans and values than Ifa scholars had thought? Isa Shin’ichi, the one who discovered the Tokyo Shimbun article, thinks this was the case, and argues that “an inferred, imagined progressivist portraiture of Ifa Fuyū” had been shaped through postwar reflections on Okinawa’s wartime ordeal, which promoted Ifa as “a proud independent scholar in that time of darkness who never compromised his unyielding, anti-militarist principles.”30

Isa’s reading of Ifa Fuyū is contentious, challenging us to revisit the “father of Okinawan studies.” My own interpretation of the intent and import of Ifa’s article differs markedly from Isa’s contention. To begin with, it is only the opening and ending of the article—about a fifth of its entire length—that uses pro-war language. These passages were likely added in response to the strict censorship of the media imposed by the military authorities, which was wide practice in Japan during the Pacific War. The rest of the article consists of decades-old boyhood anecdotes, a summary of Ryukyuan history, remarks on the positive qualities of the Ryukyuan people, and comments on the worth of national education. The article is content-wise out of proportion to be considered a straightforward piece of militaristic propaganda.

It is not likely either that Ifa believed there was any hope of Japan winning the war, despite the high-spirited message of the article. “From the very beginning of the war,” Ifa’s second wife Fuyuko recalls, he “used to say that Japan would lose the war. Furthermore, he predicted early on that Okinawa would be attacked first in Japan.”31 Nakasone Seizen (1907–1995), a close student of Ifa, also notes: “When the war broke out, Ifa, who had visited the United States and seen the country with his own eyes, deplored: ‘What stupid thing Japan does. Fighting against such a huge country is sheer stupidity’.”32 Besides, news of the war, including shattering reports from Okinawa, was becoming harder to keep secret after the summer of 1944. For instance, Yanagita Kunio writes in his diary on 4 April 1945, the day the second half of Ifa’s article appeared in Tokyo Shimbun, how dreadful the air raid was the night before in Tokyo, and notes that Ifa and his friend visited him and “talked about Okinawa’s terrible situation.”33 The discrepancy between Ifa’s private remarks on the war and the propaganda-like language found at the beginning and end of the article hints at unexpressed motives behind his words.

Further, Ifa could not have expected Okinawans, now under fierce fire during the invasion of the island, to pick up the Tokyo Shimbun and feel empowered by his article. The mail system was no longer functioning such that delivering mainland newspapers to Okinawa was a sheer impossibility. This means Ifa had a different audience in mind. At this critical point in the war, when questions of loyalty, competency, and merit were in the air, accompanied even by rumors of conspiracy,34 it is far more likely that Ifa was guarding against deep-rooted prejudice toward the Okinawan people. In the article Ifa describes the Ryukyuan people as intrepid, competent, and loyal to the country, but it is important to note that mainland Japanese had associated the exact opposite traits to Okinawans for more than half a century. Discrimination against Okinawans was a common experience for Ifa’s generation. They were thought to lack competence and were often accused of disloyalty.35 In hindsight Ifa’s remarks are particularly strategic when he states in the article that Ryukyuan soldiers are “fit for defense” but “unfit for spies.” A number of Okinawans were falsely accused of being spies for the United States and were brutally and unjustly executed by the Japanese army in the following months.36 It must be noted that there is no mention of spying in the 1915 source essay discussed earlier.37 Clearly, Ifa made this addition intentionally when he wrote the 1945 article. It may also help to compare the context with the Japanese American internment during World War II and the organization of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a unit composed almost entirely of Japanese Americans, whose narratives contributed significantly to the formation of Japanese American identity. Although the analogy does not go all the way—the 442nd Regimental Combat Team consisted of volunteer soldiers, whereas the people of Okinawa, including civilians, were drafted into service—demonstrating competence and loyalty to the nation was vital in both cases. Ifa devotes nearly a third of the Tokyo Shimbun article to underscore the Ryukyuan character, letting one of the military generals admire a unit consisting exclusively of Ryukyuan soldiers. “To tell the truth,” Ifa borrows the general’s words, “I fought as a commander of a company composed entirely of Ryukyuan soldiers and made considerable accomplishments, which resulted in great honors.” The original 1915 essay, however, only alludes to “Okinawan soldiers,”38 not to an all-Ryukyuan unit. Ifa changed the more general talk about “Okinawan soldiers” into a report of “a company composed entirely of Ryukyuan soldiers.” We can see from this how Ifa modifies his language to fight prejudice, as he did practically all his life, which often becomes as important as fighting the actual enemy for wartime minorities.

A further reflection on the question of identity must be made. What Ifa argues for in the Tokyo Shimbun article is for the most part political or national identity, which does not need to coincide, for instance, with one’s linguistic, cultural, or religious identity. To take an example, one’s national identity can be American, ethnic identity Asian, religious identity Buddhist, linguistic identity English, cultural identity Okinawan, and so forth. In Ifa’s view, the Japanese people themselves “were probably able to form a healthy nation because they absorbed a number of ethnic groups and a multitude of new thoughts.”39 Likewise the Japanese language, despite the creation of “standard” Japanese, was in Ifa’s view “a hybrid language (konsei-go) that was formed on the main island of Japan,”40 such that language alone cannot constitute one’s identity either.41 Identity in its genuine sense reveals complexity, not simplicity. It reflects Ifa’s view on Okinawa, Japan, and Asia, which is worthy of further consideration.

5. Alternative Histories of Japan

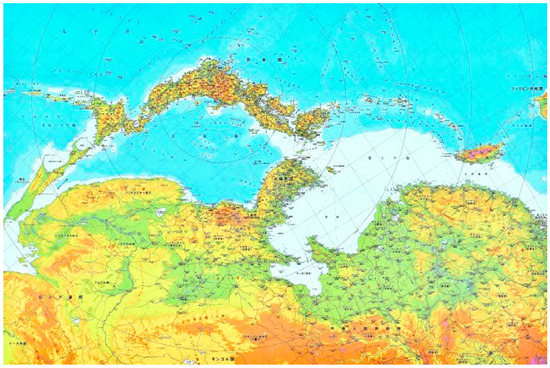

In observing alternative histories of Japan, often suppressed in mainstream narratives, Carol Gluck points out that Ifa Fuyū “played a pioneering role in the scholarly articulation of the abiding ambivalence of Okinawans caught between a desire to be fully accepted as Japanese and a wish to retain a distinctive identity derived from their own history and culture.”42 It is equally important not to underestimate the disruptive influences brought about by “identity questions.” A quick visual metaphor may help clarify the point. Figure 2 below is known as the Map of East Asian Countries on the Sea of Japan Rim (Kan-nihonkai Higashi-ajia Shokoku-zu). It is a south-side-up reversed image of East Asia with Japan appearing on the upper-middle-left ocean side. Amino Yoshihiko (1928–2004), a widely read and respected historian of Japan, contributed to the popularity of the map. He invited readers to interpret it as follows:

The impression we receive from this map is genuinely refreshing in that we are presented with an image of Japan that is completely different from that of Japan found in the ordinary world atlas. […] It offers a visual confirmation of the extremely short distance that allows a clear view of the Korean Peninsula on fine days from the north edge of Tsushima. Further, the Japanese Islands and the Southwestern Island Chain appear as connecting bridges (kakehashi); the Sea of Japan and the East China Sea on the map are reminiscent of the inland seas (uchi’umi) formed between the islands and the continent; this appears to be the case with the Sea of Japan, which vividly retains its image of a lake resting under the arms of the islands that were once linked to the continent.43

Figure 2.

Map of East Asian Countries on the Sea of Japan.45.

Pushing his point further, Amino calls the reader’s attention to the “false image of Japan” as an “island nation (shima-guni)” isolated from the rest of Asia, which was in his view an image instilled in the Japanese mind by the Meiji government in the modernization process after 1868.44

What I should emphasize here is that the standard image of Japan and the reversed image do not exclude or replace each other. It does not make sense to ask, “Which is the correct map?” Instead, what I take to be much closer to the way Ifa Fuyū charts Asia and its history is to recognize such alternate perspectives as complementing each other to form a richer sense of identity. In real history, ethnic, national, religious, linguistic, and territorial identities rarely match, and they do not need to match. Collapsing them into one abstractly imagined concept of identity—implicitly demanding a monolithic, oversimplified concept of identity—is reductive and potentially violent. By the same token, asking “What is the true Japanese identity” or “What is the true Okinawan identity?” involves misleading conceptualization. In the past a stronger sense of converging identity might have felt natural, when people generally remained in their local communities, spoke the same dialect, followed similar marriage patterns, and so on. However, modern anthropology, linguistics, ethnography, and other related studies, many of which pertain to Ifa Fuyū’s work, have convincingly shown us that culture, language, and ethnicity are always deeply complex. Ifa contrasts this fact with the more pervasive “island mentality” that he perceived in his own time. He writes:

As I stated before, Japanese people in ancient times absorbed the bloods of various ethnic groups, on the top of which they digested Chinese culture and Indian thought rather well, such that they grew very healthy both in terms of body and mind, exhibiting considerable ability of assimilation, but as a political system oriented toward national isolation was perfected after medieval times, they eventually became negative, exclusive, and self-flattering. And it was probably out of this situation that the so-called island mentality (shima-guni konjō) arose, the mentality with which Japanese people today are trying to face other newly added ethnic groups [including the people of the Ryukyus].46

In the present day it is even more imperative to view identity as a growing network of plural identities—we live with transitional and provisional identities rather than with some final identity. In the context of Okinawan studies, Okamoto Keitoku (1934–2006), an Okinawan author of wide-ranging literary works who taught at the University of the Ryukyus, reflects on such a changing sense of identity in the following illuminating words:

The world, as I stated a moment ago, is fluidizing with increasing intensity, as cultural blending pushes itself further alongside economic globalization. This is by no means confined to Okinawa, for there will be nothing in such a world that guarantees the self-sameness of people, place, and culture. If we seek afresh for a ground of identity, it would be made possible only through our reacquainting ourselves with the place that we live in and through creating a culture that fits it. This means that, in the case of Okinawans, we must have a clear will to “reinhabit” Okinawa as our place.47

It is true for many of us that identity is intimately and instinctively associated with our hometown, culture, and people. Nonetheless Okamoto suggests “reinhabitation” (sai-teijū). The idea is not to encourage cultural or historical amnesia, but to replace naively assumed notions of identity with a self-aware will that commits itself to the place where it chooses to belong. In doing so we must avoid impulsive identification with preconceived images that tend to generate identity politics.

As we have seen, Ifa Fuyū was an outstanding Okinawan historian who did not wish to see people fettered to the past. One of Ifa’s favorite quotes was “We are trampled down by history.” The complete quote from Remy de Gourmont (1858–1915) reads: “Abolish history altogether. That is, in each generation we agree to erase useless traits of the past completely ….—That sounds interesting, my friend, now that we are trampled down by history.”48 A slightly elusive tone remains in the quote, but one thing is clear: In view of where Japan stands today, careful studies of the past must lead to a productive transformation of our visions for the future. Ifa made Gourmont’s words an epigraph to his last book, A Historical Story of Okinawa (Okinawa rekishi monogatari, 1947), which he finished a month before his death. The book was given a telling subtitle: “An Epitome of Japan.”49 From Ifa’s perspective Okinawa was a mirror and touchstone for Japan.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Uehiro Foundation on Ethics and Education. I am very grateful to the officers of the Foundation for their continued support and encouragement. I also thank an anonymous reviewer for helpful comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Amino, Yoshihiko 網野善彦. 2000. “Nihon” to wa Nani ka 「日本」とは何か (What is “Japan”?). Nihon no rekishi日本の歴史 (History of Japan). Tokyo: Kōdansha, vol. 00. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, John R. 2008. A Linguistic History of the Forgotten Islands: A Reconstruction of the Proto-language of the Southern Ryūkyūs. Folkestone: Global Oriental. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, John R. 2015. Proto-Ryukyuan. In Handbook of the Ryukyuan Languages: History, Structure, and Use. Edited by Patrick Heinrich, Shinsho Miyara and Michinori Shimoji. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, Basil Hall. 1895. Essay in Aid of a Grammar and Dictionary of the Luchuan Language. Yokohama: Kelly & Walsh. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Hugh. 1997. The Great Dialect Debate: The State and Language Policy in Okinawa. In Society and the State in Interwar Japan. Edited by Elise K. Tipton. London: Routledge, pp. 193–217. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Hugh. 2015. Language and identity in Okinawa and Amami: Past, present and future. In Handbook of the Ryukyuan Languages: History, Structure, and Use. Edited by Patrick Heinrich, Shinsho Miyara and Michinori Shimoji. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 612–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gluck, Carol. 2005. Ifa Fuyū. In Sources of Japanese Tradition, vol. 2, 1600 to 2000, 2nd ed. Edited by Wm. Theodore de Bary, Carol Gluck and Arthur Tiedemann. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 1256–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gourmont, Remy de. 1922. Nouveaux Dialogues des Amateurs sur les Choses du Temps 1907–1910 (Epilogues, Ve série). Paris: Mercure de France. [Google Scholar]

- Hattori, Shirō 服部四郎. 1976. Ryūkyū Hōgen to Hondo Hōgen 琉球方言と本土方言 (Ryukyuan Dialects and Mainland Dialects). In Okinawa Gaku no Reimei: Ifa Fuyū Seitan Hyakunen Kinenkai Shi 沖縄学の黎明:伊波普猷生誕百年記念誌 (The Dawn of Okinawan Studies: A Commemorative Publication for the 100th Anniversary of Ifa Fuyū’s Birth). Tokyo: Okinawa Bunka Kyōkai, pp. 7–55. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, Patrick. 2015. Japanese language spread. In Handbook of the Ryukyuan Languages: History, Structure, and Use. Edited by Patrick Heinrich, Shinsho Miyara and Michinori Shimoji. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 593–611. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, Patrick, Shinsho Miyara, and Michinori Shimoji, eds. 2015. Handbook of the Ryukyuan Languages: History, Structure, and Use. Handbooks of Japanese Language and Linguistics 11. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Hiyane, Teruo 比屋根照夫. 1981. Kindai Nihon to Ifa Fuyū 近代日本と伊波普猷 (Modern Japan and Ifa Fuyū). Tokyo: San’ichi Shobō. [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi, Daigaku 堀口大學. 1985. Horiguchi Daigaku Zenshū 堀口大學全集 (Collected Works of Horiguchi Daigaku). Tokyo: Ozawashoten, Supplementary vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ifa, Fuyū 伊波普猷. 1974–1976. Ifa Fuyū Zenshū 伊波普猷全集 (Collected Works of Ifa Fuyū). Edited by Hattori Shirō 服部四郎, Nakasone Seizen 仲宗根政善 and Hokama Shuzen 外間守善. Tokyo: Heibonsha, 11 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Isa, Shin’ichi 伊佐眞一. 2007. Ifa Fuyū Hihan Josetsu 伊波普猷批判序説 (Prolegomenon to a Critique of Ifa Fuyū). Tokyo: Kageshobō. [Google Scholar]

- Kano, Masanao 鹿野政直. 1993. Okinawa no Fuchi: Ifa Fuyū to Sono Jidai 沖縄の淵:伊波普猷とその時代 (Okinawa’s Abyss: Ifa Fuyū and His Times). Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Kinjō, Seitoku 金城正篤, and Kurayoshi Takara 高良倉吉. 1972. Ifa Fuyū: Okinawa Shizō to Sono Shisō 伊波普猷:沖縄史像とその思想 (Ifa Fuyū: Images of Okinawan History and His Thoughts Thereof). Tokyo: Shimizu Shoin. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, Wayne. 2015. Lexicon. In Handbook of the Ryukyuan Languages: History, Structure, and Use. Edited by Patrick Heinrich, Shinsho Miyara and Michinori Shimoji. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 157–73. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Sean, and Toshikazu Hasegawa. 2011. Bayesian Phylogenetic Analysis Supports an Agricultural Origin of Japonic Languages. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 278: 3662–69. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto, Masachi’e 中本正智. 1990. Nihon Rettō Gengo-Shi no Kenkyū 日本列島言語史の研究 (A Study of the History of Languages in the Islands of Japan). Tokyo: Taishūkan Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Nakasone, Seizen 仲宗根政善. n.d. Ifa Fuyū ni tsuite 伊波普猷について (On Ifa Fuyū). In Nakasone Seizen Gengo Shiryō 仲宗根政善言語資料 (Nakasone Seizen Materials on Language and Linguistics). Unpublished manuscript at the University of the Ryukyus Library.

- Okamoto, Keitoku 岡本恵徳. 2007. Okinawa ni Ikiru Shisō: Okamoto Keitoku Hihyōshū 「沖縄」に生きる思想:岡本恵徳批評集 (Thoughts about Living in “Okinawa”: Criticism by Okamoto Keitoku). Tokyo: Miraisha. [Google Scholar]

- Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education 沖縄県教育委員会. 2017. Okinawa Kenshi, Kakuron Hen 6, Okinawa sen 沖縄県史 各論篇 6 沖縄戦 (Okinawa Prefectural History, Subject-Based Series 6, The Battle of Okinawa). Naha: Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Ōshiro, Masayasu 大城将保. 1987. Okinawa himitsu sen ni kansuru shiryō 沖縄秘密戦に関する資料 (Documents Concerning Covert Operations in Okinawa). Jūgonen Sensō Gokuhi Shiryō Shū 十五年戦争極秘資料集 3 (Top Secret Documents of the Fifteen Years War Series, vol. 3). Tokyo: Fuji Shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Oshiro, George M. 2007. Hawai‘i in the Life and Thought of Ifa Fuyū, Father of Okinawan Studies. In Uchinaanchu Diaspora: Memories, Continuities, and Constructions. Social Process in Hawai’i. vol. 42, pp. 35–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ōta, Masahide 大田昌秀. 1976. Okinawa no Minshū Ishiki 沖縄の民衆意識 (The People’s Mind in Okinawa). Tokyo: Shinsensha. [Google Scholar]

- Pellard, Thomas. 2015. The Linguistic archeology of the Ryukyu Islands. In Handbook of the Ryukyuan Languages: History, Structure, and Use. Edited by Patrick Heinrich, Shinsho Miyara and Michinori Shimoji. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 13–37. [Google Scholar]

- Serafim, Leon Angelo. 2003. When and from Where Did the Japonic Language Enter the Ryukyus?: A Critical Comparison of Language, Archaeology, and History. In Perspectives on the Origins of the Japanese Language. Edited by Osada Toshiki and Alexander Vovin. Kyoto: International Research Center for Japanese Studies, pp. 463–75. [Google Scholar]

- Shinzato, Rumiko, and Leon Angelo Serafim. 2013. Synchrony and Diachrony of Okinawan Kakari Musubi in Comparative Perspective with Premodern Japanese. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV. [Google Scholar]

- Vovin, Alexander. 2009. Ryūkyūgo, jōdai Nihongo to shūhen no shogengo: Saikō to setten no sho mondai 琉球語、上代日本語と周辺の諸言語:再構と接点の諸問題 (Ryukyuan language, old Japanese and neighboring languages: Problems of reconstruction and contact). Nihonkenkyū 日本研究 (Japanese Studies), Series 39, 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wakukawa, Seiyei 湧川清栄. 1981. A Brief History of Thought Activities of Okinawans in Hawaii. In Uchinaanchu: A History of Okinawans in Hawaii. Honolulu: Center for Oral History, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, pp. 233–42. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagita, Kunio 柳田国男. 1964. Teihon Yanagita Kunio Shū 定本柳田国男全集 (Authentic Edition: Complete Works of Yanagita Kunio). Tokyo: Chikumashobō, Supplementary vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Ifa Fuyū is often transliterated as Iha Fuyu or Iha Huyu, but Ifa Fuyū is the spelling he preferred because it reflected the old Ryukyuan pronunciation better. The spelling was adopted in the first edition of Ko Ryūkyū (Old Ryukyu, 1911), a monumental work that established Ifa’s reputation. See (Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 1, p. 536), and the handwriting on Ifa’s photograph in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Ifa Fuyū (c. 1912).

|

| 2 | Kano 1993, p. vii. |

| 3 | Ifa’s chronology, including a list of his writings, can be found in (Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 11, pp. 533–89). Most of the dates given here draw on this source. |

| 4 | The incident, consisting of a complicated sequence of events, reflected Okinawa’s educational system at the time. The main conflict was triggered when the principal of Ifa’s school announced his decision to remove English instruction from the school curriculum. Since English was becoming a core requisite for higher education in Japan, this decision appeared to be a form of discrimination against Okinawan students. For Ifa’s own narrative of the incident, see (Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 7, pp. 365–76). |

| 5 | In Ifa’s words: “I made up my mind to become a politician someday and to work hard for my insulted brothers” (Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 1, p. 12). |

| 6 | Ifa’s early linguistic work benefited from Basil Hall Chamberlain’s Essay in Aid of a Grammar and Dictionary of the Luchuan Language (Chamberlain 1895). Ifa’s debt to Chamberlain is outlined well in (Nakamoto 1990, pp. 89–119). For a summary sketch of Ifa’s place in the historical development of Ryukyuan linguistics, see (Bentley 2015, pp. 41–42). |

| 7 | Besides lexical and grammatical similarities between old Japanese and classical Ryukyuan, Ifa paid special attention to kakari musubi, a syntactic phenomenon found in both languages, which requires a specific predicate ending form that agrees with kakari particles in the sentence. Ifa’s pioneering and lasting contribution to the study of kakari musubi is acknowledged in (Shinzato and Serafim 2013). |

| 8 | A classical and influential work that endorses Ifa’s position is (Hattori 1976). The general perspective is also shared in (Serafim 2003) and (Bentley 2008), though the latter considers a different branching pattern of proto-Japanese and the proto-Ryukyuan language. Taking a new approach, (Lee and Hasegawa 2011) offers a timeline that is convergent with Ifa’s. For a general overview of the linguistic separation of the Ryukyuan and Japanese languages, see (Pellard 2015). Readers may also benefit from other selective chapters in (Heinrich et al. 2015), some of which are discussed in this article. |

| 9 | The Japanese language can be seen as comprising two major families: Mainland Japanese and Ryukyuan. The plural term “Japonic languages” is favored by linguists today given the enormous internal diversity of each family. Regarding the Ryukyuan language family, Wayne Lawrence reports: “There are over 750 distinct Ryukyuan dialects—approximately 250 spoken on the Amami Island group, over 400 on Okinawa Island and surrounding islands, about 70 Miyako dialects, and around 25 Yaeyama dialects” (Lawrence 2015, p. 157). Alexander Vovin points out: “Hardly any linguist today would doubt that the Ryukyuan and Japanese languages are sister languages” (Vovin 2009, p. 11). |

| 10 | It is worth noting that progressivism of this kind worked across sectarian currents in Japan from late Meiji through the Taisho period (see the article by James Mark Shields in this special issue). Ifa’s social activities in Japan’s southernmost prefecture of Okinawa can be seen as part of this broader movement. See also (Hiyane 1981) for Ifa’s place in view of this movement. |

| 11 | (Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 11, p. 269). |

| 12 | (Ibid., vol. 11, p. 270.) |

| 13 | Kawakami Hajime (1876–1946) was a notable Marxist whom Ifa met in 1911. After their first encounter, a sense of friendship continued for three decades without explicit interaction. The two scholars reconnected in 1943 when Ifa sent Kawakami his latest book, Okinawa-kō (Reflections on Okinawa), which had been published the previous year. |

| 14 | (Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 1, p. 484). Compare this with Ifa’s remark on “the death of the [Ryukyuan] gods” and his reference to Gustave Le Bon (1841–1931) in (Ibid., vol. 2, pp. 207, 262–63). For the same reason the “revival of Ryukyuan Shintoism” was not a critically relevant matter for Ifa, as he notes in (Ibid., vol. 5, pp. 355, 535). |

| 15 | (Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 3, p. 427). For a similar remark see (Ibid., vol. 9, p. 204). |

| 16 | (Ibid., vol. 11, p. 280). |

| 17 | (Ibid., vol. 8, p. 459). |

| 18 | (Clarke 1997, p. 204). Observing dialect hybridization and changes of linguistic behavior in Okinawa today, Clarke elsewhere writes: “As language is a social artefact, no matter how strong an individual’s commitment to its preservation might be, it will not survive unless it serves a useful function within society” (Clarke 2015, p. 646). Ifa is likely to accept a view like this, though he also remarked at one point: “When I hear a dialect dispraised like this, I feel urged to advocate for it. I do not consider it a shame that we [Okinawans] have a dialect. Nor are we responsible for having it. […] As you know, language is a social product” (Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 11, pp. 278–79). For Ifa’s later comment on the extinction of dialects and the difficulty of spreading a common Okinawan language, see (Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 10, pp. 430–32). |

| 19 | (Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 9, p. 191). Earlier on, Ifa attributed this view to Japanese linguist Kobayashi Hideo (1903–1978), the world’s first translator of Ferdinand de Saussure’s Cours de linguistique générale (1916) into a foreign language (see Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 8, pp. 224–25). |

| 20 | Ifa was invited to Hawai‘i by Okinawan immigrants Tōyama Tetsuo (1883–1971) and Higa Seikan (1887–1985). Tōyama was a successful journalist in Honolulu who also invited such figures as Kagawa Toyohiko (1888–1960) and Nishida Tenkō (1872–1968) to the islands. Ifa was sympathetic with Kagawa and had also worked closely with Higa to establish the Okinawa Kumiai Kyōkai (Okinawa Congregational Church) in the mid-1910s. According to Wakukawa Seiyei, Higa Seikan “preached by roadside the doctrines of Toyohiko Kagawa [the foremost Christian leader in Japan at the time] and Tenko Nishida [another Japanese religious leader]” (Wakukawa 1981, p. 23). In this special issue, see also Michel Mohr’s discussion of Nishida Tenkō and cross-sectarian religious movements in Japan at that time. |

| 21 | (Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 11, p. 339). |

| 22 | (Ibid., vol. 1, p. 68). |

| 23 | Oshiro 2007, p. 56. |

| 24 | Ifa’s original article, previously unknown and hence not included in Ifa Fuyū Zenshū (Ifa 1974–1976), was reprinted in Ryūkyū Shimpo, May 21 and 23, 2007, accompanied by Isa Shin’ichi’s interpretive essay. Quotations from this article are based on the reprint version. |

| 25 | The first appearance of the material goes back to Ifa’s early essay “Impressions of Twenty-Five Years Ago” (Ryūkyū Shimpo, 24 September 1917); the second appearance to “Recollections of Middle School” (Okinawa Kyōiku, 1 April 1924); the third to “Recollections of Middle School by University Graduate Mr. Ifa, the Director of the Prefectural Library” (Yōshū, No. 31, December 1924); the fourth to “Recollections of Middle School” (published as an appendix in Ryūkyū Kokonki [Records of the Ryukyus from Ancient to Modern Times], 1926 [see (Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 7, pp. 357–77)]); and the fifth to “Recollections of When I Was Still in [Middle] School” (Yōshū, No. 35, July 1934). |

| 26 | (Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 7, p. 369). This corresponds to the fourth appearance mentioned in the previous note. |

| 27 | (Ibid., vol. 7, p. 370). |

| 28 | (Ibid., vol. 10, pp. 352–53). |

| 29 | In this special issue, drawing on the diary of a young priest, Kunihiko Terasawa explores nationalistic and militaristic trends in wartime Japanese Buddhism. |

| 30 | Isa 2007, p. 184. |

| 31 | Ifa Fuyuko’s remark quoted in (Kinjō and Takara 1972, p. 193). |

| 32 | (Nakasone n.d., p. 226), item 261. Isa Shin’ichi is correct to point out that some ambiguity remains regarding the exact source and date of these words (Isa 2007, pp. 168–69). Yet it is reasonably clear from the context that Ifa made the remark not long after his return from Hawai‘i and the mainland U.S. in 1929. |

| 33 | (Yanagita 1964, p. 181). Yanagita Kunio (1875–1962), Japan’s prominent folklore scholar, remained influential in Ifa’s life and work. As a side note, when Yanagita met with Ifa in 1921, he persuaded Ifa to shift from what appeared to be the strenuous life of a social activist to the life of a more dedicated academic. This constituted one of the reasons Ifa left Okinawa and moved to Tokyo in 1925, after which he could devote more of his time to the study of Omoro sōshi and other Ryukyuan materials. Hence it was from Tokyo, not Okinawa, that Ifa contributed his 1945 article to Tokyo Shimbun. |

| 34 | Some of the rumors went so far as to speculate that Okinawan locals were all spies for the United States, a theory known as Okinawajin sō spai setsu (Okinawans are all spies theory). Primary documentation and an overview can be found in (Ōshiro 1987). |

| 35 | The historical formation of such discrimination is described in (Ōta 1976), with insightful references to Ifa Fuyū and his contemporaries (see especially chapters 6 and 7). |

| 36 | Okinawans were executed for a number of reasons: For speaking Okinawan; for not appearing to respond favorably to Japanese military orders; for showing independent or self-directed leadership in the community; for having encountered—and hence believed to have interacted with—Americans; and so on. For further details, see (Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education 2017). |

| 37 | See note 28 and pertinent discussions in the text. |

| 38 | (Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 10, p. 352). |

| 39 | (Ibid., vol. 1, p. 486). |

| 40 | (Ibid., vol. 4, p. 32). |

| 41 | Ifa repeatedly emphasized that language is not innate but is socially acquired. “It is wild,” he also says, “to try to decide ethnic lines based on language alone, which is an acquired quality” (Ibid., vol. 8, p. 431). |

| 42 | (Gluck 2005, p. 1257). |

| 43 | Amino 2000, p. 36. |

| 44 | Although unmentioned by Amino, we should bear in mind that the accelerated language shift from Ryukyuan dialects to standard Japanese took place in Okinawa during the same period. After reminding readers that Ifa Fuyū started to learn Japanese at the age of eleven, Patrick Heinrich remarks: “The rapid spread of Japanese across the Ryukyus is yet more astounding considering the fact that Japanese compulsory school education initially met with little enthusiasm from the side of Ryukyuan parents” (Heinrich 2015, p. 596). |

| 45 | Reprint permission granted for this article by Toyama prefecture, including the map (H24, Jōshi 情使, no. 238). |

| 46 | Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 1, p. 490. |

| 47 | Okamoto 2007, p. 211. |

| 48 | (Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 7, p. 380). The quote is based on Horiguchi Daigaku’s translation (Horiguchi 1985, p. 57). Remy de Gourmont (1858–1915) was a French social and literary critic who was popular in Japan during Ifa’s time through translated editions of his work. The context of the original passage can be verified in (Gourmont 1922, pp. 331–32). For Ifa’s other allusions, direct and indirect, see (Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 2, pp. 94, 284, 338, 450, 452; Ibid., vol. 7, p. 283; Ibid., vol. 10, pp. 315, 322; Ibid., vol. 11, pp. 295, 299). |

| 49 | (Ifa 1974–1976, vol. 2, p. 329). A facsimile image of Ifa’s handwritten inscription of this short English phrase is included in (Ibid., vol. 2, p. 569). |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).