1. Introduction

While mass shootings represent a small percentage of gun-related deaths in the United States, they generate a great deal of media coverage and public concern (

Healy 2015;

Greenberg et al. 2018). Mass shootings occur more frequently in the United States than in other comparable countries, with some of the most lethal incidents occurring in just the last few years. In October 2017, 56 people died in a shooting at a music festival in Las Vegas, Nevada. The next month, a shooting at a Baptist church in Sutherland Springs, Texas claimed 26 victims. Several incidents have occurred at schools or universities: Virginia Tech in 2007, Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012, and, most recently, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School and Santa Fe High School in 2018. These and other shootings have intensified debate over the divisive issue of gun control. Many surveys show broad popular support for some policies, such as universal background checks for gun purchases, federal tracking of gun sales, and banning assault-style weapons and high-capacity magazines (

Pew Research Center 2017). Predictably, public opinion falls along political partisan lines (

Pew Research Center 2017). Increasingly, public opinion reflects growing concern and interest over the issue of mental health as it relates to mass shootings (

Jones et al. 2013). Surveys also point to religious cleavages in views of gun policy, with evangelical Protestants most wary of gun control (

Jones et al. 2013).

Religious defenses of gun rights and calls for looser gun policies are common. After high-profile shootings, particularly in schools, content and memes shared on social media often blame a secularizing society and the decline of traditional values. One set of especially popular memes suggests that school shootings occur because God and prayer are disallowed in public schools. Prominent political leaders and conservative media both echo and reinforce these ideas. After the shooting at Sandy Hook, former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee suggested on a TV appearance, “We ask why there’s violence in our schools but we’ve systematically removed God from our schools” (

Merica 2012). Bryan Fisher of the American Family Association has argued, “we have mass school shootings because we don’t have enough God on our campuses and we don’t have enough guns,” going on to lament the removal of prayer from schools and to call for concealed carry policies on schools and campuses (

Fisher 2018). At the 2018 annual convention of the National Rifle Association (NRA), Texas governor Greg Abbott stated, “The answer (to gun violence) is to strengthen Second Amendment rights for law abiding citizens of the United States of America. It is to ensure we get guns out of the hands of criminals, and out of those mentally unfit to have guns. The problem is not guns. The problem is hearts without God. It is homes without discipline and communities without values” (

Chang 2018). These and similar arguments suggest that flawed individuals, family dysfunction, and irreligious societal values are to blame for gun violence, and that looser gun control could be a defense against future violence.

Religion receives relatively less attention than other factors in discussions of gun control, including research on Americans’ attitudes toward gun policies. Understandably, scholars and media analysts point to political ideology, cultural divides, race, gender, and geography as factors that shape individuals’ relationships with firearms (

Kleck et al. 2009;

O’Brien et al. 2013;

Pew Research Center 2017;

Wolpert and Gimpel 1998). Recent research, however, sheds light on the complex relationship between religion, gun ownership, and gun policy preferences. Religion has an important influence on individuals’ and groups’ cultural tool kits, or the ways that they organize experience and evaluate reality (

Swidler 1986). Since these cultural tools are transposable, or extended to a range of situations, they shape how people respond to claims about social problems and what should be done about them. The current study uses data from a nationally representative survey conducted in 2012 to examine the relationship between Americans’ religious identities and their attitudes toward a range of gun-related policies and proposed solutions to address mass shootings. Following recent research, I focus primarily on white evangelical Protestants, who tend to have higher rates of gun ownership and opposition to gun control than do Americans who identify with other faiths (

Zylstra 2017).

2. Religion and Guns

Several recent studies investigate the complex relationship between religion and guns. Noting that religion often appears only as a control variable in studies of gun ownership,

Yamane (

2016) examines how religious affiliation, theological conservatism, and religious participation are related to personal handgun ownership. Using data from the nationally representative General Social Survey (GSS), Yamane demonstrates that evangelical Protestants are more likely to own a gun compared to the general population. Net of demographic controls, however, evangelical Protestants are significantly more likely than only mainline Protestants and those who identify with “other religions,” a category that consists of mostly non-Christian faiths. Theological conservatism is positively associated with handgun ownership, which the author suggests could reflect a sort of “risk reduction” strategy, given the link between theological conservatism and lower generalized trust. Finally, the study finds that religious involvement is negatively associated with personal handgun ownership.

Mencken and Froese (

2017) examine the symbolic functions of gun ownership. Using the nationally representative Baylor Religion Survey, they develop an eight-item “gun empowerment” index that measures an owner’s level of moral and emotional attachment to guns. Items measured, for example, the degree to which gun ownership makes the respondent feel safe, responsible, confident, more in control, and more valuable to others. The relationship between gun empowerment and religion is complex. Self-estimated religiosity decreases gun empowerment, while church attendance has a curvilinear relationship with gun empowerment. Gun owners who attend somewhat regularly report greater empowerment than those who never attend, but this effect reverses for weekly attenders. Furthermore, in multivariate analyses, religiosity is associated with support for banning semi-automatic weapons and high-capacity clips. They argue that more devout individuals may have less time or need for guns, while also being wary of excessive violence and force. Pew Research Center surveys also find that more regularly attending Americans are less likely to own a gun. However, more religiously committed gun owners are more likely than less committed owners to belong to the NRA (

Zylstra 2017).

Stroope and Tom (

2017) also examine the link between religion and guns. Using nationally representative data from the Add Health study, they show that evangelical Protestant adolescents in the United States are more likely to have easy access to a gun at home compared with adolescents in other religious groups. They discuss several possible reasons for evangelical Protestants’ attachment to and ownership of guns. They note an evangelical Protestant emphasis on individual autonomy and self-sufficiency. This relates to gun ownership and views of gun policy in at least two ways. First, this emphasis corresponds with a preference for less government involvement and interference in individuals’ and families’ lives. Second, it leads evangelical Protestants to make dispositional rather than situational attributions for wrongdoing (

Grasmick and McGill 1994). In other words, evangelicals emphasize that individuals are to blame or credit for outcomes, rather than broader social circumstances or social structural factors. Presumably, this emphasis informs how evangelical Protestants think about gun violence and gun control as well.

Celinska (

2007) situates the issues of gun ownership and gun control attitudes in the struggle between individualism and collectivism in American society. Individualists emphasize self-reliance and personal achievement and possess a lack of faith in the institutionalized, collective means of security. Using GSS data, the author finds that Protestants score higher than others on two separate indexes of individualism, while Protestant affiliation and individualism are both predictive of gun ownership and opposition to a gun permit requirement.

Stroope and Tom (

2017) point to still more factors that could explain the link between evangelical Protestants and guns. A cultural emphasis on masculinity and traditional gender roles could positively incline adherents toward gun ownership, informed by the position that a man’s responsibility is the protection of others, particularly family. Additionally, evangelical Protestants’ reading of American history leads them to see divine influence in the founding of the nation and in the Constitution. Thus, the Second Amendment, interpreted as ensuring the right to personal gun ownership, is granted religious legitimation and is intended to guarantee other rights, such as freedom of religion. Finally, a tension between evangelical Protestants and secular institutions in society contributes to their stance on firearms. A wariness toward the information provided by secular educational institutions and scientific research could incline evangelical Protestants to discount expert recommendations regarding gun control and safety procedures.

Drawing on the cultural tool kit metaphor,

Emerson et al. (

1999) shed light on how evangelical Protestants construct social problems and possible solutions. While their research focuses on how these cultural tools shape evangelical Protestants’ understandings of inequality, particularly racial inequality, they also argue that these cultural tools are transposable to a variety of issues and situations. One important cultural tool is an emphasis on “accountable freewill individualism,” a cultural trait noted by other scholars as well. From this view, people are individually accountable for their own actions—accountable to both other people and to God. Complementing the emphasis on individualism is the cultural tool of “anti-structuralism,” or a profound wariness toward attributions of individual or social problems that point to social structure, or the “system,” as responsible, rather than individual choices. Finally, evangelical Protestants emphasize “relationalism” by assigning great importance to interpersonal relationships. This is apparent in a “strong emphasis on family relationships, friendships, church relationships, and other forms of interpersonal connections. Healthy relationships encourage people to make right choices. As such, white evangelical Protestants often see social problems as rooted in poor relationships or the negative influence of significant others” (

Emerson et al. 1999, p. 401). Thus, they favor a strategy of personal influence, particularly religious influence, as a means of improving social relationships and addressing social problems.

The aforementioned cultural tools of evangelical Protestants likely shape their attributions of gun violence, including mass shootings, as well as their preferred solutions. Reflecting their anti-structural and relationship-centered understanding of social problems, evangelical Protestants are wary of laws or policies designed to restrict firearm access or regulate them further. Evangelical Protestants are likely to favor solutions that do not target private gun ownership. They are also likely to attribute gun violence and mass shootings to the individual shooters or to relational factors like parenting or family relationships. While some scholars argue that evangelical Protestants wish to see their religious values inform public policy (

Wald 2003),

Smith (

1998) asserts that evangelicals favor a “personal influence strategy.” Specifically, they “… see themselves as uniquely possessing a distinctively effective means of social change: working through personal relationships to allow God to transform human hearts from the inside-out, so that all ensuing social change will be thorough and long-lasting” (

Smith 1998, p. 188). This view of social change is apparent in many of evangelical Protestants’ responses to gun violence and mass shootings, in calls for cultural changes that start with individual action and a greater presence of religion in schools and other institutions.

Adherents of other religious traditions differ from white evangelical Protestants in their relationship to guns and gun policy. Mainline Protestants are distinct from evangelical Protestants in their comparatively modernist theology and generally more moderate stances on social and moral issues. While mainline Protestants’ gun ownership rates tend to be higher than those in non-Protestant faiths (

Yamane 2016), they tend to be more open to stricter gun laws (

Jones et al. 2013) and have historically been more likely than evangelical Protestants to support social reforms intended to address social problems. African American Protestants are less likely than their white counterparts to own a gun and more likely to support stricter gun laws. Black Protestant support of gun control stems partly from black communities’ direct experience with gun violence. African Americans are more likely than other Americans to know someone who has been shot (

Pew Research Center 2017). These factors make black churches and their adherents more likely to engage in gun control activism as well. The African American Church Gun Control Coalition, for example, brings together numerous predominantly black denominations to work for local and national reforms (

Banks 2013).

Beyond Protestants, other notable differences exist. For example, Catholics’ well-known pro-life ethic may apply broadly, including support for stricter gun laws to curb gun violence. Catholics who identify as “pro-life” are far more likely than like-minded evangelicals to support more gun control (

Jones et al. 2013). In addition, gun control has institutional support from the Catholic church. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops has publicly called for a range of gun control measures, including expanding background checks, banning certain high-powered weapons, and increased safety measures (

Catholic News Agency 2017). In contrast, gun control tends to have less institutional support from predominantly white evangelical denominations, like the Southern Baptist Convention (

Farmer 2017). Interfaith efforts at gun control exist as well, typically bringing together mainline Protestants, Catholics, black Protestants, and non-Christian communities like Muslims and Jews. For example, a campaign in the Northeast called Heeding God’s Call focuses on local and legislative remedies for reducing gun violence (

The Coalition to Stop Gun Violence 2018).

Using national survey data, I examine how adherents of major religious groups evaluate a range of gun policies, particularly proposals to make gun control laws stricter, more strictly enforce existing laws, or loosen existing laws. I also examine how respondents think specifically about mass shootings and what proposed remedies they find most appealing.

3. Data and Methods

The current study uses data from the 2012 PRRI/Religion News Survey. The survey was designed by the Public Religion Research Institute. Survey results were based on bilingual (Spanish and English) random digit dialing (RDD) telephone interviews conducted August 8–12, 2012 by professional interviewers under the direction of Social Science Research Solutions (SSRS). Interviews were conducted among a random sample of 1006 adults 18 years of age or older in the continental United States (304 respondents were interviewed on a cell phone). The data set was downloaded from the Association of Religion Data Archives website (

www.TheARDA.com). The recommended weight variable is used for all analyses.

The key independent variable is religious tradition. On the survey, respondents were asked, “What is your present religion, if any? Are you Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, Mormon, something else, or nothing in particular?” Respondents who indicated that they are “Protestant” or “Christian/Non-denominational Christian” (

N = 487) were also asked, “Would you describe yourself as a ‘born-again’ or ‘Evangelical Christian,’ or not?” Response options were “yes” or “no.” I created a new variable that places respondents into one of several major religious groups, modeled after the widely used RELTRAD scheme (

Steensland et al. 2000). Non-black respondents who identified as “born-again” or “Evangelical Christian” were coded as “evangelical Protestant” (the resulting category is 90% non-Hispanic white). Non-black respondents who did not identify as such were coded as “mainline Protestant.” Black respondents who identified as “Protestant” or “Christian” were coded as “black Protestant.” The new variable also included the categories of “Catholic,” “None” to indicate respondents who selected “nothing in particular,” and “Other religions” for respondents who identified as anything else. Descriptive statistics are shown in

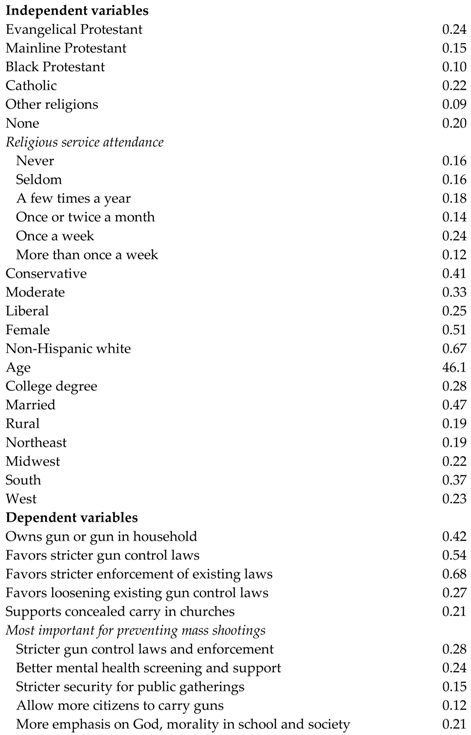

Table 1.

Several additional independent variables were used in multivariate analyses. Religious service attendance was measured with the following item: “Aside from weddings and funerals, how often do you attend religious services … more than once a week, once a week, once or twice a month, a few times a year, seldom, or never?” I reverse coded the six-item scale such that higher values indicate more frequent attendance. Political orientation was measured with the following item: “Generally speaking, would you describe your political views as … very conservative, somewhat conservative, moderate, somewhat liberal, or very liberal?” For regression analyses, I created dummy variables for conservative (1 = “very conservative” or “somewhat conservative”) and moderate (1 = “moderate”), leaving respondents who identify as liberal as the reference group. Demographic control variables include sex (1 = female), race (1 = non-Hispanic white), age, whether the respondent has a college degree (1 = four-year degree or more), marital status (1 = married), whether the respondent lives outside a metro area (1 = rural), and region (dummy variables for the Northeast and Midwest, and West; South is the reference group).

A measure of gun ownership is used both as a dependent variable and as an independent variable in multivariate analyses. Respondents were asked, “Do you or does anyone in your home own a gun?” Response options were “yes, self,” “yes, someone in household,” “yes, both you and someone else in your household,” and “no.” I recoded the variable to indicate whether anyone in the household, respondent or otherwise, owns a gun (coded 1) or not (coded 0).

Measures of support for proposed gun control policies serve as dependent variables. Respondents were asked, “Now, I’d like to get your views on some issues that are being discussed in the country today. All in all, do you strongly favor, favor, oppose, or strongly oppose …?” Respondents were then presented with three items: “Passing stricter gun control laws,” “Stricter enforcement of existing gun control laws,” and “Loosening current gun control laws.” To simplify bivariate and multivariate analyses, I created binary variables for each item by collapsing “strongly favor” and “favor” (coded 1) and “oppose” and “strongly oppose” (coded 0). Given the current study’s focus on religion and guns, I also use a measure of support for concealed carry of firearms in places of worship. Respondents were asked, “In general, do you think people should be allowed or not allowed to carry concealed guns in a church or place of worship?” Response options were “yes, should be allowed” and “no, should not be allowed.”

Finally, I use a measure of what respondents consider to be the most important remedy for preventing future mass shootings. Respondents were asked, “What do you think is the most important thing that could be done to prevent mass shooting from occurring in the United States?” Response options were “stricter gun control laws and enforcement,” “better mental health screening and support,” “stricter security measures for public gatherings,” “allow more private citizens to carry guns for protection,” and “put more emphasis on God and morality in school and society.” In the results that follow, I present both bivariate analysis of how religious preference relates to each dependent variable, as well as logistic regression analyses predicting support for each gun control policy. For the item on preventing mass shooting, I perform a multinomial logistic regression with “stricter gun control laws and enforcement” as the reference category. This category is meaningful because a plurality of respondents chose it and the current study is interested in examining specifically evangelical Protestants’ support for solutions that do not involve restrictions on firearms.

4. Results

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for each of the dependent variables. Forty-two percent of respondents report either owning a gun themselves or that another household member owns a gun. Support for gun control is mixed. A slim majority of respondents (54%) either favor or strongly favor stricter gun control laws. Stricter enforcement of existing laws is more popular, with 68% of respondents favoring this proposal. Loosening existing gun control laws is less popular. About a quarter (27%) of respondents favor or strongly favor loosening current laws. Allowing concealed carry of guns in churches is relatively unpopular, with only 21% of respondents in support. Finally, when presented with five proposals to reduce the occurrence of mass shootings, respondents are divided. A plurality of respondents (28%) think that “stricter gun control laws and enforcement” is the “most important thing” for preventing mass shootings. Slightly fewer respondents selected “better mental health screening and support” (24%) or “put more emphasis on God and morality in schools and society” (21%) as the most important actions. Less popular are “stricter security measures for public gatherings” (15%) and “allow more private citizens to carry guns for protection” (12%).

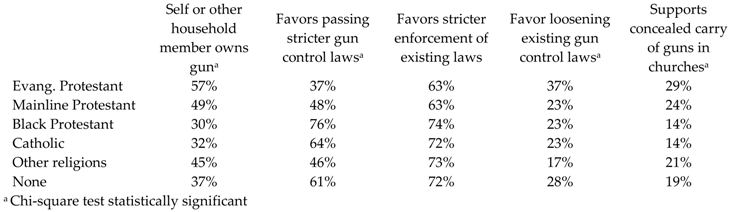

Table 2 reports data on gun ownership and support for gun control proposals by religious tradition. Only among evangelical Protestants do a majority of respondents report having a gun in the household (57%). Nearly half of mainline Protestants (49%) and adherents of “other religions” (45%) report gun ownership. Only 37% of those with no religion report having a gun, followed by 32% of Catholics and 30% of black Protestants. Support for passing stricter gun control laws varies widely by religious group. Evangelicals are least likely to favor stricter gun control, at only 37%. Black Protestants are most supportive (76%), followed by Catholics (64%) and religious “nones” (61%). Mainline Protestants and those of “other religions” are both about equally split between favoring and opposing. Less variation exists in support for stricter enforcement of existing gun control laws. A solid majority of respondents in every religious tradition favor more enforcement, with evangelical and mainline Protestants both slightly less supportive. Evangelical Protestants are most in favor of loosening existing gun laws, but only 37% register support. Adherents of “other religions” are least supportive (17%), while between 23–28% of respondents in the remaining traditions favor a loosening of gun laws. Finally, while evangelical Protestants are most likely to support concealed carry of guns in churches, only 29% do so. Twenty-four percent of mainline Protestants support it, as do 21% of those in “other religions.” Among Catholics, black Protestants, and those with no religion, less than 20% expressed support for concealed carry in churches. Finally, note that for all but stricter enforcement of existing gun control laws was the relationship between religious tradition and the variable in question statistically significant, according to chi-square tests.

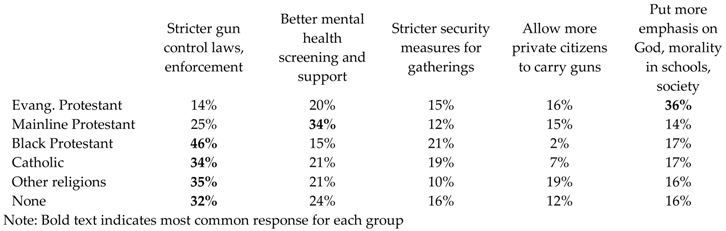

The relationship between religious tradition and respondents’ favored remedies to address mass shootings is examined in

Table 3. Among black Protestants, Catholics, adherents of “other religions,” and the religiously unaffiliated, a plurality of respondents indicated that stricter gun control laws and enforcement are the most important thing to do. Black Protestants were most likely to do so (46%). Notably, only 14% of evangelical Protestants selected this option, and 25% of mainline Protestants. A plurality of evangelical Protestants (36%) indicated that putting more emphasis on God and morality is the most important, while a plurality of mainline Protestants (34%) selected better mental health policies as the most important. Notably, less than 20% of respondents in every other religious tradition suggested that putting more emphasis on God and morality is the most important way to prevent mass shootings. Allowing more citizens to carry guns is most popular among evangelical Protestants (16%), mainline Protestants (15%), and those of “other religions” (19%). Notably, only 2% of black Protestants and 7% of Catholics favored this remedy. Better mental health policies and stricter security measures for public gatherings show less variation by religious tradition.

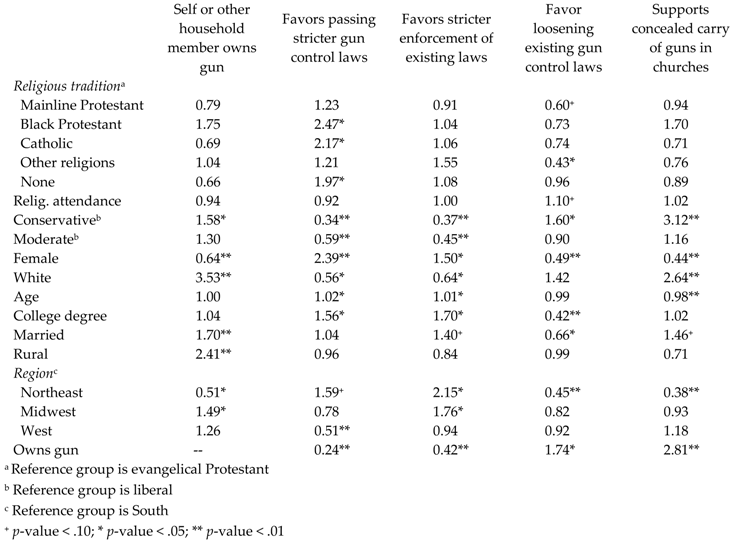

Table 4 reports estimated odds ratios from a series of logistic regression analyses predicting gun ownership and support for gun control proposals. Before adding other independent variables to the model, evangelical Protestants are significantly more likely than black Protestants, Catholics, and the religiously unaffiliated to report that they or someone in their household owns a gun (not shown in

Table 4). In the full model, however, religious tradition is no longer a significant predictor. Conservatives, non-Hispanic whites, married respondents, and rural respondents are all significantly more likely to report gun ownership. Women are less likely than men to report owning a gun.

Compared with southerners, those residing in the Northeast are less likely, while those living in the West are more likely to report gun ownership in the home. As for favoring stricter gun control laws, before demographic controls, evangelical Protestants are significantly less likely compared with black Protestants, Catholics, and the unaffiliated (not shown). The gap between evangelical Protestants and mainline Protestants approaches significance (p-value = 0.067). Notably, in the full model, black Protestants, Catholics, and “nones” are still significantly more likely than evangelical Protestants to favor stricter gun control. Predictably, conservatives and moderates are less likely than liberals to favor stricter gun control, as are whites, gun owners, and those residing in the West. Women and those with a college degree are more supportive than men and those with less than college degree.

Before adding control variables, respondents in every tradition but mainline Protestants are more likely than evangelical Protestants to favor stricter enforcement of existing gun control laws (not shown). In the full model shown in

Table 4, however, there are no differences by religious tradition. Conservatives and moderates are less likely than liberals to favor stricter enforcement, while whites and gun owners are also less supportive. Women and the college-educated are more supportive than men and those without a degree, while those in the Northeast or Midwest are more supportive than those in the South. When considering support for looser gun control laws, before adding other independent variables, evangelical Protestants are significantly more supportive than respondents in every other religious tradition (not shown). In the full model shown in

Table 4, however, only those of “other religions” differ significantly, while the difference between mainline Protestants and evangelicals approaches significance (

p-value = 0.069). Conservatives and gun owners are more likely than liberals and non-gun owners to favor loosening gun control laws. Women and those with a college degree are less likely than men and those with less than a college degree to favor such a loosening of gun laws. Finally, before adding additional variables, evangelical Protestants are significantly more likely than black Protestants, Catholics, and the unaffiliated to support concealed carry of guns in churches (not shown). In the full model, however, evangelical Protestants’ support for concealed carry does not differ from any other tradition. Once again, conservatives, whites, and gun owners are more supportive, while women are less supportive. Those residing in the Northeast are less likely than those in South to support concealed carry in churches.

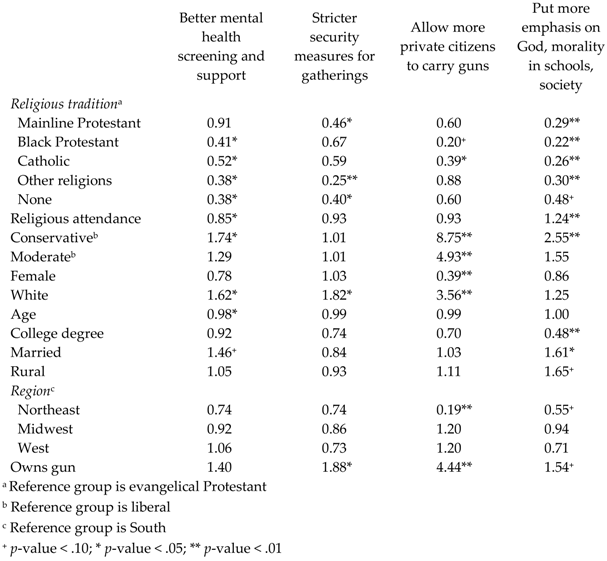

Table 5 contains estimated odds ratios from a multinomial logistic regression analysis predicting respondents’ choice of the “most important thing” that can be done to prevent mass shootings. “Stricter gun control laws and enforcement” is the reference category in the model. Thus, odds ratios are interpreted as the likelihood of choosing each option over stricter gun control laws. Controlling for a range of other factors, black Protestants, those in “other religions,” and those with no religion are significantly less likely than evangelical Protestants to indicate that better mental health screening and support are the most important over stricter gun control. Respondents who attend religious services more frequently are also less likely to do so. Conservatives and whites are more likely than liberals and non-whites to select better mental health policy as the most important to do instead of stricter gun control. Mainline Protestants, those in “other religions,” and the unaffiliated are all significantly less likely than evangelicals to indicate that stricter security measures at public gatherings are the most important remedy instead of stricter gun control. Whites and gun owners are more likely than non-whites and those who don’t own a gun to favor stricter security measures at public gatherings over stricter gun control. Net of other independent variables, only black Protestants (

p-value = 0.08) and Catholics are less likely than evangelical Protestants to favor more citizens carrying guns as the most important remedy for mass shootings. Political orientation, race, and gun ownership are especially strong predictors of support for this proposal. Conservatives and moderates are far more likely than liberals to favor more citizens carrying guns as a means of preventing mass shooting, and whites are much more likely than non-whites. Women are significantly less likely than men to favor more citizens carrying guns.

The final column of

Table 5 shows which variables predict selecting “put more emphasis on God and morality in schools and society” over stricter gun control as the most important thing that can be done to prevent mass shootings. Net of all other independent variables, evangelical Protestants are significantly more likely than respondents in every other religious tradition to indicate that more emphasis on God and morality is the most important thing that can be done. Those who attend religious services more frequently are also more likely to favor putting more emphasis on God and morality. Conservatives and married individuals are more likely to do so compared with liberals and those who are not married. Living in a rural area and being a gun owner approach significance in terms of being predictors of favoring more emphasis on God and morality. Finally, those with a college degree are less likely than those with less education to suggest that this is the most important intervention instead of stricter gun control laws.

5. Discussion

Media analysts and researchers often depict the gun control debate as stemming from deep cultural and political divides between rural and urban Americans, gun owners and non-gun owners, whites and non-whites, and liberals and conservatives. The current study finds that each of these variables relates to gun control attitudes in predictable ways. My findings also suggest that religion contributes to individuals’ understandings of gun violence and views of gun control. Evangelical Protestants consistently oppose stricter gun control laws and even support looser gun laws. In contrast, Americans in other religious traditions, particularly black Protestants, Catholics, and the nonreligious, consistently favor stricter gun control laws. Notably, these group differences persist even when numerous demographic characteristics are controlled for, along with gun ownership. Adherents of different religious groups in the United States also have contrasting views of mass shootings. Evangelical Protestants are much less likely than those in other religious traditions to view stricter gun control as an important way to prevent mass shootings. As

Table 5 shows, evangelical Protestants are significantly more likely than those in other traditions to favor other remedies, particularly improving mental health treatment or infusing religion into schools and society.

These findings are consistent with the evangelical cultural tool kit described by

Emerson et al. (

1999): an emphasis on personal responsibility, anti-structuralism evident in their attributions of social problems and opposition to government intervention in citizens’ lives, and a belief that healthy and religiously-based relationships are most effective at addressing social ills.

Stroope and Tom (

2017) argue that an emphasis on “rugged masculinity” and religious legitimation for the Second Amendment also contribute to a link between evangelical Protestants and guns. This is not to suggest that other Americans do not also possess these cultural tools. Individualism and anti-structuralism, for example, are widely held schemas among Americans. Rather, they are uniquely strong elements of evangelical Protestants’ worldview and therefore contribute to how they view social problems generally, and gun violence specifically in this case. In contrast, my findings suggest that black Protestants, Catholics, the nonreligious, and to a lesser extent, mainline Protestants, tend to be more supportive of stricter gun control laws and enforcement as a means of reducing gun violence. Furthermore, these differences in support for gun control are not entirely attributable to race, education level, political ideology, region, gun ownership, and other variables accounted for in the multivariate analyses.

Religious service attendance displayed limited predictive power as a variable in the current study. In the multinomial logistic regression analysis, attendance was negatively associated with choosing “better mental health screening and support” over “stricter gun control laws and enforcement,” and positively associated with “put more emphasis on God and morality in schools and society” as the most important thing to do to prevent mass shootings. Other studies have suggested a complex relationship between religiosity and gun ownership and gun policy preferences. More frequent attenders may have less attachment to or ownership of guns, relative to less frequent attenders (

Mencken and Froese 2017;

Pew Research Center 2017). More research is needed, however, to examine how religiosity influences Americans’ relationships with firearms.

The current study has limitations. First, the relatively short survey and small sample size limit what data analyses can be performed. There are also few religion items on the survey, making it difficult to probe more complex questions about the link between religion and gun control attitudes. Second, the survey was conducted in 2012. Some of the most lethal mass shootings in American history have occurred in the years since, generating new media coverage and concern over the issue. There is some evidence of a shift in gun control attitudes in the United States, with growing support for new gun restrictions, even among Republicans (

Khalid 2018) and evangelical Protestants (

Jones et al. 2013). Future research should continue to take religion seriously as a contributor to Americans’ gun control attitudes and probe for factors that mediate the relationship between religious tradition and support for or opposition to gun control. A recent study demonstrates that gun owners and non-gun owners have different attributions for mass shootings, with gun owners inclined to blame popular culture and parenting and non-gun owners more likely to blame the availability of guns (

Joslyn and Haider-Markel 2017). Evangelical Protestants, too, may be more likely to have attributions that reflect their concern with individual responsibility and interpersonal relationships.

Research suggests that availability of guns and rates of gun ownership are positively related to gun-related deaths, including homicides and suicides (

Harvard Injury Control Research Center 2018). While experts argue that more research is needed, there is some evidence that stricter gun control reduces gun-related injuries and deaths (

Santaella-Tenorio et al. 2016;

Webster et al. 2014), and could do so in the United States (

Cook and Goss 2014;

RAND 2018). Furthermore, experts argue that the growing focus on the role of mental health may be somewhat misguided and misleading, as gun violence committed by those with mental illness represents only a very small percentage of overall gun violence and the United States does not have higher rates of mental illness than other countries (

Knoll and Annas 2016;

Kodjak 2018). As religious influences steer Americans’ understandings of gun violence toward individualistic and cultural factors and away from effective gun policies, building political support for reform will be difficult. Researchers, activists, and religious leaders should explore ways to engage with religious communities in the United States on this contentious issue.