Abstract

Feminist biblical criticism of Proverbs 1–9 has decried the figure of “Dame Folly” as reinforcing pejorative stereotypes of women that blame women for “the world’s sin and corruption.” To be sure, in the history of Christian biblical interpretation, Proverbs has been read in precisely this way—and with tragic consequences. In fact, Proverbs was used as fuel for the witch-hunting craze that infected the Christian West in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with its particular focus on women as being especially “addicted” to heresy and “evil superstitions.” Nonetheless, as this essay demonstrates, a reading which denigrates all women universally as blameworthy is not really native to post-exilic Judaism or biblical literature in general before the Hellenistic period. Instead, it emerges with the influence of Hellenism and the misogynist stereotypes endemic to Greek literature, mythology, and even philosophy that distort and blur the lens through which Hellenistic Jews (and later Greco-Roman Christians) read their Scriptures. Through a reading of Proverbs in its own language, its own post-exilic Jewish world, and its own literary context, this essay both recovers the wise women of Israel, so esteemed and valued in post-exilic Judaism, and uncovers the identity of the real fool of Proverbs 9.

1. Introduction

In an insightful article on the portrayal of the feminine of Proverbs 1–9, Gale A. Yee objects to what she describes as the “personification in a woman’s form of all that is evil and destructive,” claiming that “subliminally in the minds of men ever since Eve, women have been considered responsible for the world’s sin and corruption.” Given the erotic imagery surrounding both Lady Wisdom and her wily foil, the “foolish woman,” Yee laments that “the most profoundly unsettling message that comes across particularly to the female reader is that only man pursues Wisdom like a lover, and it is a woman who seduces him away from her.” She questions if a woman can “ever seek and ultimately find Wisdom,” or if a woman must “simply suffer the fate” of the “foolish woman,” scorned as “an object of aversion and ever condemned” (Yee 1989, pp. 66–67). Taking up Yee’s concerns, Claudia V. Camp, linking the “foolish woman” (כְּסִילוּת אֵשֶׁת, literally, “woman of stupidity”) of Proverbs 9:13 with the “strange woman” (זָרָה אִשָּׁה) of Prov. 2:16, 5:3, 7:15, charges that “in Proverbs, strangeness, not of nationality but of gender, is given its fullest expression,” and that “Proverbs … makes the metaphorical connection between woman and the strange, thus identifying woman as that which is not proper to ‘Israel.’ National/ethnic distinction has been assimilated to and named by gender distinction” (Camp 2000, pp. 59–61).

To be sure, the Book of Proverbs, like other literature from the ancient Near East and the Mediterranean basin, is androcentric, written by men for men.1 Moreover, the history of biblical interpretation of the foolish, promiscuous woman of Proverbs 1–9 points to the tragic consequences that can result when such a portrayal is taken out of its original context and universalized to women in general.2 For this reason, Yee’s and Camp’s charges are important, not easily to be dismissed. In what way, however, are such charges justified when reading the text of Proverbs, particularly Proverbs 1–9 and its juxtaposition of Lady Wisdom and “the foolish woman”? In other words, does the problem lie with the Book of Proverbs itself or, instead, with a misogynist reading of the text, a reading shaped more by the worldview of the reader than that of the biblical author? What is the original intention of Proverbs 9? Is it, as Yee claims, to hold women responsible for men’s sins? Or, as Camp believes, to “identify woman as that which is not proper to Israel”? To address these questions, this essay will examine the figures of Lady Wisdom and the “foolish woman,” or “Dame Folly,” of Proverbs 9 in their historical and literary contexts, their relation to the rest of the prolog of the Book of Proverbs, and their relevance to other pertinent passages in the Hebrew Scriptures with a particular focus on what these texts reveal about attitudes toward women in post-exilic Judah.

2. A Brief Overview of the Prolog to Proverbs: Authorship, Date, Historical Context, Structure

The first nine chapters of the Book of Proverbs form a prolog to the rest of the book and are thought by most scholars to have been appended as an introduction to the מִשְׁלֵי שְׁלֹמֹה, the “proverbs of Solomon,” largely a collection of aphorisms similar to those found in the wisdom literature of Israel’s neighbors. Some of these aphorisms are ascribed to various personages, such as Hezekiah (25:1), Agur (30:1), and Lemuel (31:1) and, while the Book of Proverbs itself is attributed to King Solomon (1:1; 10:1), few today would argue on behalf of Solomonic authorship.3 While some parts of Proverbs are clearly ancient, evidencing an adaptation of Egyptian wisdom literature known from the second millennium B.C.E., this biblical book is nonetheless notoriously difficult to date simply because it resembles the “international character of the wisdom tradition” in antiquity and offers no historical reference (Nickelsburg and Stone 1983, p. 203).

In regard to setting a date for the prolog itself, while its supposed archaicisms would suggest a pre-exilic dating,4 the majority of scholars today, however, believe that, at least in their final form, chapters 1–9 date to the post-exilic period.5 To be sure, parts of Proverbs may indeed be ancient, with roots going back centuries into the oral and written traditions of the ancient Near East; nevertheless, the prolog, particularly the figure of the “foolish woman” of 9:14–18, ties in thematically with post-exilic prophetic injunctions against abandonment of Yahwism, as will be explained below. Blenkinsopp suggests that this sad female figure, whom he labels the “Outsider Woman,” situates Proverbs 1–9 in “the complex realities of Judean society during the two centuries of Iranian rule… [with its] socially and economically dominant elite. The anxiety of this elite to preserve its social status and economic assets may … have been an important factor in generating the language in which the Outsider Woman is described and her activities denounced” (Blenkinsopp 1991, p. 466).

Because nothing in the prolog makes any mention of the poor or even hints at anything related to economic survival, many commentators believe it reflects the world of the social elite, with the leisure necessary for study and the “pursuit of wisdom” or … the pursuit of women outside the community of the returned exiles. Noting the “upper-class origin and ethos of wisdom literature in general, and Proverbs 1–9 in particular,” Blenkinsopp believes that the warnings against the seductions of the “Outsider Woman” were addressed to the social elite and priestly families of Babylonian origin who formed the ruling class in the post-exilic period (Blenkinsopp 1991, p. 472). Camp concurs, arguing that the presence of the “outsider” or “foolish” woman of Proverbs 1–9 is an indicator of the problems inherent in the tensions of the post-exilic quest to settle upon questions of Jewish identity:

These tensions resulted from the return of some of the descendants of the exiled Judean leadership group (the golah, ‘exile’) from Babylon. The return led first to the contested rebuilding of the Jerusalem temple and then to ongoing struggles for both power and survival between those who had returned, those who had remained in the land and those who had entered the land in the interim. At stake behind the more material concerns was the fundamental matter of Jewish identity—who would be regarded as inside and outside the congregation, and who would decide(Camp 2000, pp. 41–42).

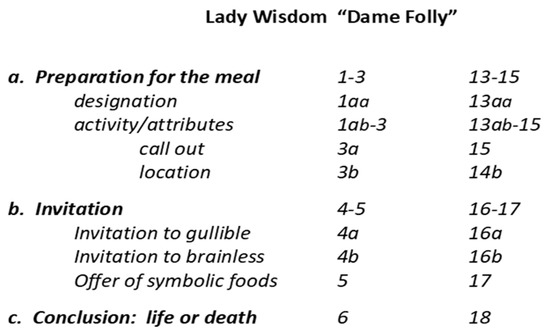

Composed as the conclusion to the prolog, Proverbs 9 is set as a diptych summarizing the basic choice before a young man—the old Deuteronomistic choice for life or death (Dt 30:15,19) now recast as a choice for wisdom or folly (Clifford 2016, pp. 2–3). On one side of the diptych is the sumptuous, carefully prepared banquet of Lady Wisdom (9:1–6); on the other is the enticing but fatal promise of “Dame Folly” (כְּסִילוּת אֵשֶׁת, literally, “the woman of folly”) to provide a meal of “sweet stolen water” and “tasty secret loaves” (9:13–18). He who is simple or naïve (פֶתִי) and accepts the invitation to Lady Wisdom’s banquet (9:4) must “forsake ‘stupid things’” (literally, “simple” or “naïve” things or persons: פְתָאִים, 9:6). Only in this way, he “will live” (וִחְיוּ) and advance along the way of “understanding” (בִּנָה). If, on the other hand, he accepts “Dame Folly’s” invitation, he will naively enter a tomb from which he will never leave: “He does not know that the shades of the dead are there, that her guests are in the depths of Sheol” (Prov 9:18; cf. 7:27). The invitations of Lady Wisdom and Dame Folly each appear attractive; a mature discernment is required to make the choice that leads to life. In fact, as Bruce Waltke points out (Figure 1), the invitations of the two very different ladies are nearly identically structured:

Figure 1.

(Waltke 2004, p. 430).

Indeed, one is a foil for the other; only the discerning will know how to tell them apart. Both are depicted in enticing, even erotic terms, so that the one presents a reverse image of the other, with Lady Wisdom offered as a counter to Dame Folly even as the practice of wisdom is offered by the sage to counter morally and religiously aberrant behavior (Blenkinsopp 1991, p. 466; Perdue 2000, p. 133).

3. Wisdom Personified: The Figure of Lady Wisdom

Even as the personification of Wisdom as a woman is presented metaphorically by Jewish sages as a “counter” to “Dame Folly,” Proverbs 8 nevertheless points to Wisdom as a divine figure overseeing the work of creation, a figure as puzzling as it is intriguing. This personification of Wisdom as both female and divine is perplexing in light of the strict post-exilic Jewish monotheism from which she arises. For this reason, modern scholarship has been both tireless and creative in its search for Lady Wisdom’s mythological roots and literary prehistory in Egypt, Canaan, Babylon, Iran, and Greece; indeed, she has commonly been held to be a Hebraicized version of Ma’at, meaning “Justice, Order, Truth,” the “the fundamental principle of reality underlying the Egyptian wisdom books,” sometimes personified as a goddess (Day 1995, p. 68).6

Within the various pantheons of Israel’s Semitic neighbors are more tantalizing parallels for Lady Wisdom. John Clifford, for example, puts forward a fourteenth-century BCE Ugaritic text, the Legend of Aqht, as providing the mythological origin for the figure of Lady Wisdom because of what he believes are “striking similarities in vocabulary and motifs to Proverbs 1–9, especially to Proverbs 9” Clifford 1975, p. 298). Because of her association with the “tree of life” (Prov. 3:18; 11:30; 13:12; 15:4), some scholars believe she derives from the goddess Asherah whose sacred symbol was a stylized tree (Smith 1990, p. 95). Bernhard Lang (1986, pp. 25–26) suggests that Lady Wisdom, prior to the emergence of Yahwistic monotheism, was the Canaanite goddess called Hokhmah (Wisdom), the “goddess of scribes and administrators.”7 More convincing, however, are the parallels to the personification of Wisdom in the Wisdom of Ahiqar, a non-Jewish Aramaic work dating to the 5th century BCE:

‘[From] heaven the peoples are [fa]voured; [W]isdom i[s of] the gods. Indeed, she is precious to the gods; Her kingdom is et[er]nal. She has been established in the he[aven]s. Yea, the lord of the holy ones (or Baal Qdshn) has exalted her’(quoted in Day 1995, p. 69).

Whatever Lady Wisdom’s mythological prehistory, and there is no consensus among scholars on this point, in Proverbs she is described as divine, present with God at the dawn of the cosmos (8:22ff), assisting playfully in the work of creation as God’s companion and confidant (8:30). While transcending creation, Wisdom is profoundly immanent, the intimate companion of God who welcomes, even seeks out, the intimacy of human beings. She is a gift of God to all those who seek her (2:6); she saves from the “way of evil” and the “man who speaks perversely” (2:12), as well as from the “strange woman,” the “outsider woman” (זָרָה אִשָּׁה, 2:16; 7:5). She is a “cure for the body, a tonic for the bones” (3:8), a “tree of life” (3:18). Happy the one who finds her (3:13)!

Just as Lady Wisdom first appears in personified form in 1:20–33, following an extended discourse to the young sage on avoiding the enticements of sinners (חַטָּאִים), her presentation in the extended poem of 8:1–9:7 is followed by the prolog’s concluding poem on avoiding sin’s seductions (personified as Dame Folly) in 9:13–18. Unlike Proverbs 8, however, in 9:1 Lady Wisdom is referred to as חָכְמוֹת (ḥōkhmōt, a Hebrew feminine plural noun, literally, “Wisdoms”),8 just as she is in 1:20, rather than the feminine singular noun חָכְמָה (ḥōkhmah).9 In the preceding chapter, she has assisted God with the work of creation; thus in 9:1 she has “built her house,” perhaps a reference to the created world as her dwelling. There likely is a reference to 14:1 as well (“The wisest of women builds her house, but folly tears it down with her own hands”).10 Wisdom is presented as industrious, creative, and inviting. The seven pillars indicate a spacious, welcoming, and palatial building with room enough for a huge crowd of guests. “Seven” symbolizes perfection and may also represent the number of planets known in the ancient world (Waltke 2004, p. 433). Summarizing the various ways that Wisdom’s palace can be understood, Leo Perdue observes the following:

The meaning of the building of the house has been understood in a variety of ways, ranging from the creation of the cosmos, much as an architect would design and then build the world, to the construction of a palace or temple, to the formation of the wisdom tradition, to the literary construction of a poem (the one in chapter 9) or the larger collection of ten instructions and several wisdom poems (in chapters 1–9), to an aristocratic house, to a place of study in which students also resided. If the earlier images of Woman Wisdom in the striking poem of chapter 8 are kept in mind, it would seem that her building likely represents several levels of meaning: the one who designs and builds the cosmos (Prov. 8:30: ʾāmōn as “builder”; Wisdom of Sol. 7:22), the queen of heaven who inaugurates her reign with the construction of her palace and its dedication with a great banquet (Prov. 8:12–21), and a house of study for those who take up her course of study (Prov. 8:32–36). In merging these images with the “building” of a magnificent poem, Wisdom is the divine creative and sustaining power that originates and maintains the cosmos, teeming with life, and who, incarnate in both the wisdom tradition and its teachers, offers life and well-being to all who choose to learn of her(Perdue 2000, pp. 149–50).

After constructing a palatial home to accommodate all who will accept her invitation to join in her feast, Wisdom prepares her meat for the sumptuous banquet.11 Literary texts from Ugarit and the Hebrew Bible both attest to women as well as men being involved in food preparation and hosting a banquet (Marsman [2003] 2021, p. 724). Meat and wine were too costly to be consumed by common people and were thus associated with special festivals, particularly those commemorating royal inaugurations. Wisdom’s banquet, then, is a celebration of her rule as she offers her feast to the unlearned, a feast that brings them life (Perdue 2000, p. 151). Wisdom’s associates, her servant girls, are female, in all likelihood reflecting the situation of women of the upper class with numerous maidservants in attendance.12 What is remarkable about Wisdom’s invitation is that it is addressed specifically to the “simple,” the “senseless,” not to any special elite. It is an open invitation to all, publicly announced from the heights of the town,13 not secretly or privately delivered. Indeed, Wisdom has no favorites save only those who accept her invitation: “Those who love me I love, and those who seek me will find me” (8:7). Her call from the highest places competes with that of Dame Folly whose house is also located there.14

Wisdom’s call is urgent; 9:5–6 is cast as a welcoming invitation in direct contrast to the reproaches which she issued in 1:20. The parallelism of verses 5 and 6 points to the equations between (a) partaking of Wisdom’s banquet and forsaking “simpleness” and (b) drinking Wisdom’s wine and walking in the way of understanding:

“Come, eat my food and drink the wine that I have mixed;15

Forsake simpleness and live, walk straight in the way of understanding.”16

To eat her food and drink requires leaving behind “simpleness,” literally, “simple ones” or “dullards,”17 those associates who would distract the young sage from pursuing wisdom: “He who walks with the wise becomes wise, but he who is a companion of fools comes to grief” (13:20).18 Mixed with spices, hers is no ordinary wine. To drink it is to walk in sobriety, with understanding.

Wisdom’s direct address to the simple and senseless changes in 9:7–12 into a short collection of aphorisms quite like those found in other parts of Proverbs with similar themes, e.g., the correction of the scoffer (15:12; 19:25; 21:11) and the “fear of the Lord.”19 These verses, with the possible exception of 9:11, seem out of context and can be completely eliminated with no loss of meaning to the poem of 9:1–6.20 For this reason, there is a debate among scholars regarding their original placement. What is worth noting about their placement here, however, immediately after Wisdom’s urgent call, is that they form part of Lady Wisdom’s own direct instruction, not that of the sage giving his son or disciple advice.21 What is remarkable about this is that teaching and instruction are put on the lips of a female figure in Israel’s wisdom literature. This is true not only in regard to Lady Wisdom as metaphor, which has parallels in the ancient Near East, but also and most especially in regard to the wise mother’s instruction in Proverbs 1:8; 6:20; 31:1, which has no parallels. As McKinlay (1996, p. 101) explains,

… The very first reference to woman as teacher comes in 1.8, where the mother’s teaching parallels the father’s instruction; a similar parallelism occurs in 6.20. Both of these lines head passages of formal ‘instruction,’ a literary genre used in common with surrounding cultures, and particularly with Egypt. But what is not shared is this inclusion of the mother, which appears to be peculiar to the Israelite writers.

4. Wisdom’s Foil: Dame Folly’s Early Post-Exilic Context and Multiple Meanings

In contrast to Lady Wisdom, “Dame Folly” (כְּסִילוּת אֵשֶׁת, 9:13), literally, “woman of stupidity,” is all too human; indeed, she is as much a caricature of antiquity’s femme fatale as she is a personification of stupidity and foolishness. Her epithet כְּסִילוּת (kᵉsîlûṯ, “stupidity”)22 shows up only here in the Hebrew Scriptures.23 The root of כְּסִילוּת (kᵉsîlûṯ), כסל (ksl), is derived from a word meaning “thick, plump, fat,” and is associated with “loins” (כְּסָלִים) and positively can denote “confidence,” or negatively “stupidity,” “folly” (כִּסְלָה ,כֶּסֶל).24 It is worth noting that, in the Hebrew Bible, the application of the noun כְּסִילוּת (kᵉsîlûṯ) as an adjective exists only in its masculine form (כְסִיל) and is used more than fifty times in the TNK to refer to males.25 Dame Folly’s description in 9:13–18 has obvious parallels with the adulterous “strange” or “outsider” woman (אִשָּׁה זָרָה) and the “foreign” woman (נָכְרִיָּה) woven throughout the prolog (2:16–19; 5:3–11; 7:5–27), with additional parallels with the “evil woman” (אֵשֶׁת רָע, 6:24)26 and “the harlot” (6:26). While זָרָה and נָכְרִיָּה are not specifically used in Proverbs 9, they are used throughout the prolog in such a way as to call to mind Dame Folly. In other words, even before being specifically named in 9:13, Dame Folly (כְּסִילוּת אֵשֶׁת) is also the “strange” woman, the “outsider” woman.27 This is no surprise since, as Blenkinsopp (1991, p. 463) insists, “in the moralising didactic literature of ancient Egypt, the influence of which on Israelite and early Jewish wisdom is incontestable, the femme fatale is typically a foreigner or at least an outsider with respect to the society in which the recipient of the advice moves (e.g., ‘The Instruction of Ani,’ ANET 420).”

Whether Folly is outside the post-exilic Jewish community as a foreigner (and, unlike the Moabite Ruth, a practitioner of a foreign religion) or a social outcast, however, is difficult to tell. Nearly all commentators agree that the negative representations of female waywardness throughout the prolog become subsumed into the figure of Folly in Proverbs 9. Indeed, viewed from within the entire context of chapters 1–9, she looms large, even larger, as some scholars have argued, than Lady Wisdom. As Roland E. Murphy (1988, p. 600) points out, more lines are given to her than to any other woman, even Lady Wisdom. Indeed, because of all the attention devoted to her, Blenkinsopp (1995, p. 159) is convinced that it is the Outsider Woman/Dame Folly, rather than Lady Wisdom, who is the “primary symbolic figure” throughout Proverbs 1–9. Throughout the prolog she pops up repeatedly as a sharp contrast to Wisdom, a contrast which reaches its literal peak in Proverbs 9, where her symbolic value intensifies into the personification of all that is harmful both to the youth seeking Wisdom and to Israel (Waltke 2004, p. 429).

Not surprisingly, then, nailing down the exact identity of Dame Folly has proven as elusive and puzzling as the quest for Lady Wisdom’s mythological origins and provoking about as much disagreement. Is she an adulteress or cultic prostitute, a fallen woman or goddess, a foreign woman or the metaphoric representation of “Daughter Judah/Zion” unfaithful to her covenant with YHWH (Prov. 2:17; Hos. 3:1; Lam. 2:1,5,13; Micah 1:13; 4:8)? To scholars such as Waltke (2004), she represents (understatedly) nothing more than sexual seduction and infidelity in its extreme. Certainly, as Crawford (1998, p. 365) reminds us, “while Wisdom’s gifts cover all aspects of life (e.g., riches, insight, a life of ease), Folly’s snares are almost entirely sexual,” despite the number of verses in Proverbs 1–9 disparaging other forms of evil or foolish behavior, such as robbery, deception, murder, and arrogance (cf. 1:11–19; 4:24; 6:12–19).

In every way, Folly opposes Wisdom. Wisdom is industrious, whereas Folly just sits in the doorway of her house (9:14); Wisdom prepares a wonderful feast with mixed wine and meat, while Folly can only offer “stolen water” and “furtive bread” (9:17).28 Yet in an eerie imitation of Wisdom, Folly calls to all “from the heights of the town” (9:14) and, like Wisdom, invites the simple (9:15–16). Unlike Wisdom, however, whose banquet means life to those who accept her invitation (9:6), what Folly offers only leads to the lifeless depths of Sheol where only the shades of the dead reside (9:18).

While she is the antithesis of Wisdom, metaphorically Folly functions in the same way as Wisdom. In other words, as Wisdom is herself more than the teachings contained in Proverbs, so Folly is more than sexual seduction (Murphy 1995, p. 225). The wiles of Folly have as much to do with religious infidelity as marital infidelity; the two become inseparably linked as adultery becomes a metaphor for apostasy. As Blenkinsopp (1995, p. 159) observes:

The Outsider Woman’s seductive arts are described graphically, not to say luridly, and in some detail. There is even the motif, common to ancient and modern fiction, of the husband absent on business (7:19–20). We would therefore be led to think of this portrait as serving the purpose of moral admonition, and, indeed, the point about marital infidelity is made explicitly and in moralizing terms (5:15–20; 6: 25–35). If, however, we recall the frequent association in the Hebrew Bible between sexual immorality and idolatry (e.g., 1 Kgs. 11: 1–9 and Hos. 1–3), we shall see that this portrait of the femme fatale also stands for the allure of foreign cults and therefore warns against religious infidelity. One has only to think of the foreign wives of Esau or Solomon or the measures taken by Ezra against marriages with women outside the civic-religious community.

Indeed, more than in the rest of the prolog, Proverbs 9:14 hints at some possible cultic connection in the presentation of Folly as sitting on “a chair at the heights of the town,” (TNK).29 The Hebrew word translated into English as “chair” is כִּסֵּא, which, out of 136 usages in the Hebrew Bible, 131 times clearly means the “throne”30 upon which royal or religious figures sit.31 For example, the word כִּסֵּא is used for what recognized religious personages sit upon, such as Eli (1 Sam 1:9; 4:13,18) and Elisha (2 Kgs. 4:10).32 In 1 Kings 2:19, the Queen Mother, Bathsheba, is given a throne (כִּסֵּא) to sit upon by her son Solomon. Additionally, throughout the TNK, the God of Israel is described as seated upon a throne (כִּסֵּא), not unlike other ancient Near Eastern deities.33 Notice how Isaiah makes a connection between a “throne” (כִּסֵּא) and “sitting” upon a “summit” where pagan gods are worshipped in his mockery of a Babylonian king’s hubristic aspiration to build a temple tower reaching to the gods: “Higher than the stars of El will I set my throne. I will sit in the mount of assembly, on the summit of Zaphon” (Isaiah 14:13).34 As this passage from Isaiah makes clear, summits or “high places” were locations of shrines in antiquity. Read in this light, Folly’s throne upon the heights of the city in Prov 9:14 suggests a sanctuary at odds with Yahwism and its centralized cult in the temple. According to Perdue (2000, p. 154), Folly’s throne represents “the location of power, either that of a god or a royal figure. This image intimates that [Folly] possessed a position, status, and esteem, either religiously or politically, in the social and religious structure of postexilic Judah.” Many scholars agree with Perdue’s observation (Perdue 2000, pp. 132–33), that behind the figure of Dame Folly “may be a poetic, metaphorical description of something even more fundamentally dangerous to Judaism: the allure of foreign religion and culture and their threat to [Israel’s] religion and culture,” described in graphic terms in both pre-exilic and exilic prophetic books as sexual seduction and adultery, metaphors for apostasy (e.g., Hosea 1–3; Jer. 3:2–4,12–13, 20; 4:30–31; Ezekiel 16).

While some have postulated that Folly is a devotee of a fertility goddess or perhaps a cultic prostitute,35 she may simply represent Israel unfaithful to its covenant with YHWH, an infidelity which is thought to begin with the intermarriage of those outside the covenant community, as is seen in Deuteronomy 7:1–6:

Indeed, marriage to foreign women was what led to the fall from wisdom of King Solomon (1 Kgs 11:4):When the LORD your God brings you into the land that you are about to enter and occupy, and he clears away many nations before you—the Hittites, the Girgashites, the Amorites, the Canaanites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites, seven nations mightier and more numerous than you—and when the LORD your God gives them over to you and you defeat them, then you must utterly destroy them. Make no covenant with them and show them no mercy. Do not intermarry with them, giving your daughters to their sons or taking their daughters for your sons, for that would turn away your children from following me, to serve other gods. Then the anger of the LORD would be kindled against you, and he would destroy you quickly. But this is how you must deal with them: break down their altars, smash their pillars, hew down their sacred poles, a and burn their idols with fire. For you are a people holy to the LORD your God; the LORD your God has chosen you out of all the peoples on earth to be his people, his treasured possession(NRSV).36

King Ahab, marrying the foreign woman Jezebel, is described in similar terms (1 Kings 16:30–32):In his old age, his wives turned away Solomon’s heart after other gods, and his heart was not as wholly given to the LORD his God as the heart of his father David had been.

Ahab son of Omri did evil in the eyes of the LORD, more than all who were before him. As if it were a light thing for him to follow the sins of Jeroboam son of Nebat, he took as his wife Jezebel, daughter of King Ethbaal of the Sidonians, and he went and served Baal and worshiped him. He erected an altar to Baal in the temple of Baal which he built in Samaria.

Is Dame Folly, then, as אִשָּׁה זָרָה (“strange woman”) and נָכְרִיָּה (“foreign woman”) symbolic of foreign religion and of the foreign women who tempt their partners away from Yahwism? While this is quite likely, she could also be symbolic of faithless Israel who was first described by the eighth century BCE northern prophet Hosea in similar terms because of Israel’s participation in idolatrous worship:

Hosea, however, is an eighth-century BCE prophet in the northern kingdom of Israel. What about post-exilic Judah? Some scholars believe that worship of the “Queen of Heaven,” known in pre-exilic Judah, continued even into the post-exilic period. Jeremiah 7:18 laments that “the children gather wood, the fathers kindle fire, and the women knead dough to make cakes for the Queen of Heaven.” Jeremiah 44 describes how even the “kings and princes” of Judah were involved in the cult of the “Queen of Heaven” (Jer. 44:17, 21), a cult which extended into the Temple in Jerusalem with the ritual mourning of the Queen’s dead lover, Tammuz (Ezek. 8:14). If, as Susan Ackerman (1989, p. 117) suggests, Jeremiah 44 can be dated to a century after Jeremiah the prophet, then this pre-exilic worship of the Queen of Heaven continued into the fifth century B.C.E. with the dedication of a temple to the Queen of Heaven by the descendants of Judahites fleeing the Babylonian invasion. It is not surprising, then, that even in post-exilic times, Third Isaiah would use language similar to that of Hosea against the people of Judah:They shall eat, but not be satisfied; they shall prostitute themselves, but not multiply; because they have forsaken the LORD to devote themselves to prostitution. Wine and new wine take away the understanding. My people consult a piece of wood, and their divining rod gives them oracles. For a spirit of prostitution has led them astray, and they have prostituted themselves, forsaking their God. They sacrifice on the tops of the mountains, and make offerings upon the hills, under oak, poplar, and terebinth, because their shade is good. Therefore your daughters prostitute themselves, and your daughters-in-law commit adultery. I will not punish your daughters when they prostitute themselves, nor your daughters-in-law when they commit adultery; for the men themselves go aside with prostitutes, and sacrifice with temple prostitutes; thus a people without understanding comes to ruin. Though you prostitute yourself, O Israel, do not let Judah become guilty(Hosea 4:10–19, NRSV).

Upon a high and lofty mountain,

you have set your bed,

and there you went up to offer sacrifice(Is. 57:7, NRSV).

What is especially worth noting in the above passages from Hosea 4:10–19 and Isaiah 57 and 65 are the similar motifs shared with Proverbs 9, i.e., the connection of idolatry with “prostitution,” the worship of foreign deities in high places, and the metaphor of the unsatisfying meal of idolatry vs. the food and drink enjoyed by YHWH’s faithful servants.But as for you who forsake the LORD, forgetful of my holy mountain, who set a table for Luck and fill cups of mixed wine for Destiny: I will destine you for the sword, you will all bow down to the slaughter, because I called, but you did not answer; I spoke, and you did not listen. You did what was evil in my eyes, and what I do not delight in you chose. Therefore, thus says the Lord GOD: my servants shall eat, and you shall hunger; my servants shall drink, and you shall thirst; my servants shall rejoice, and you shall be shamed; my servants shall shout in good-hearted gladness, and you shall wail in anguish, howling in heartbreak(Isaiah 65:11–14, NRSV).

Nearly a century after the return from Babylon, the prophet Malachi would take up the same reproach of Judah’s infidelity to YHWH:

Denouncing the easy divorces sought by Jewish men who had “forsaken the wife of their youth” to marry women who were devotees of foreign cults, Malachi shares two recurring motifs with Proverbs 1–9 and its depictions of the “strange”/“outsider” woman: breaking the “covenant” with the wife of one’s youth (Prov. 2:17: “she forsakes the companion of her youth and disregards the covenant of her God”) and marrying the “daughter of a foreign god” (נֵכָר בַּת־אֵל), i.e., an “outsider” or “idolatrous woman.” In Malachi, the men of Judah are reproached for faithlessness to their wives; what is more, a man’s infidelity to his wife becomes equivalent to and identified with infidelity to YHWH.Have we not all one father? Has not one God created us? Why then are we faithless to one another, profaning the covenant of our ancestors? Judah has been faithless, and abomination has been committed in Israel and in Jerusalem; for Judah has profaned the sanctuary of the LORD, which he loves, and has married the daughter of a foreign god. May the LORD cut off from the tents of Jacob anyone who does this—any to witness or answer, or to bring an offering to the LORD of hosts. And this you do as well: You cover the LORD’s altar with tears, with weeping and groaning because he no longer regards the offering or accepts it with favor at your hand. You ask, “Why does he not?” Because the LORD was a witness between you and the wife of your youth, to whom you have been faithless, though she is your companion and your wife by covenant. Did not one God make her? Both flesh and spirit are his. And what does the one God desire? Godly offspring. So look to yourselves, and do not let anyone be faithless to the wife of his youth. For I hate divorce, says the LORD, the God of Israel, and covering one’s garment with violence, says the LORD of hosts. So take heed to yourselves and do not be faithless. You have wearied the LORD with your words. Yet you say, “How have we wearied him?” By saying, “All who do evil are good in the sight of the LORD, and he delights in them.” Or by asking, “Where is the God of justice?”(Malachi 2:10–17 NRSV).

When Proverbs 1–9 is read in tandem with Malachi, Dame Folly becomes not just any woman but, on the contrary, a caricature of the type of woman for whom only a simpleton (פֶּתִי) would be stupid enough to leave his much more lovely Jewish wife (Prov. 5:18–19). At the same time, when viewed in the context of Israel’s prophetic literature, she represents not only the allurements of foreign religion and its female practitioners—allurements which, as Proverbs 9 tells us, will be ultimately unsatisfying and lead to ruin—she also represents Israel’s faithlessness both to YHWH and to each other. This faithlessness, both to fellow members of the community of Israel and to the God of Israel, will ultimately lead to that community’s undoing as its traditions, virtues, and values become increasingly eroded (Perdue 2000, p. 148). Nothing less than the survival of post-exilic Judaism is what is at stake as its national, cultural, and religious identity become threatened by the allurements of alien religion and culture. Dame Folly, then, is all of the above—adulteress, foreign goddess, foreign woman, and unfaithful Israel. In her original post-exilic context, she represents not all women in general but, instead, all that which threatens to erode Israel’s fidelity to its Covenantal relationship.

5. Reading “Folly” out of a Post-Exilic Context: Hellenistic Jewish Distortions and Misogynist Stereotypes

It will not be until centuries later, with the arrival of Hellenism and its promulgation of Greek language, literature, and culture around the eastern Mediterranean, Levant, and Ancient Near East, bringing with it the persistent, centuries-old negative stereotypes of women propagated by Greek writers since at least Hesiod, that the figure of Dame Folly will become reinterpreted as applying to women in general. At least in Western literature, negative stereotypes of women can arguably be traced to eighth century BCE Hesiod’s stories of human origins in Works and Days, 47–105 (WD) and Theogony, 507–616 (Th). In Hesiod’s creation accounts, before the first woman is created, men are happy just as they are, “remote and free from ills and hard toil and heavy sickness” (WD, 90–93). However, after men steal fire from Zeus, he designs the first woman, Pandora, as a punishment upon unsuspecting men, “an evil thing in which men will all delight while they embrace their own destruction” (WD, 57–58). It is through this first woman that “sorrow and mischief [come] to men,” including “countless plagues” and diseases; indeed, the earth and sea become full of evils, thanks to her (WD, 94–103). Later on, Hesiod will assert that all women are deceitful: “any man who trusts a woman trusts a deceiver” (WD, 374). In the Theogony, Hesiod adds that Pandora, a “beautiful evil” (καλόν κακόν, Th, 585), is the origin of “the race of women and female kind: of her is the deadly race and tribe of women who live amongst mortal men to their great trouble” (Th, 590–92).37

As Hesiod’s writings become widely shared around the Mediterranean and the Ancient Near East with the spread of Hellenism, his creation stories, along with his universally applied pejorative stereotypes of women, would profoundly influence later generations for centuries to come: Greeks, Hellenistic Jews, and Romans alike. Hesiod’s views would even shape ideas about morality and law around the Hellenistic (and later Hellenistic Roman) world, as well as later biblical interpretation among Hellenistic Jews and their Greco-Roman Christian inheritors.38

The influence of Hellenism, particularly the misogyny inherited from Greek writers and thinkers after Hesiod,39 becomes especially apparent when contrasting the way women are portrayed in biblical literature before the Hellenistic period with portrayals of women in Jewish literature, both biblical and extrabiblical, in the Hellenistic period. For example, 2 Samuel, likely with sources in Israel’s early first millennium BCE oral and written traditions, has no difficulty describing a woman as “wise” (e.g., “the wise woman of Tekoa” in 2 Sam 14:2).40 Nor does Proverbs. When reading Prov 9:10 (“The fear of the LORD is the beginning of wisdom”) alongside Prov 31:30 (“a woman who fears the LORD is to be praised”), as well as the wise teachings of King Lemuel’s mother in Prov 31:1–9, it becomes clear that Proverbs, just like 2 Samuel, can also recognize wisdom in a woman.41 In stark contrast with these passages in the TNK composed before Hellenism’s arrival in the Levant, the author of Ecclesiastes can find “no wise woman at all” (Ecclesiastes 7:28). This negative stereotype in Ecclesiastes, dated to somewhere in the early Hellenistic period, is unique to the rest of the TNK and betrays a Hellenistic influence.42 In the same way, Sirach, a Jewish wisdom book from the second century BCE patterned after Proverbs, offers another undeniable example of Hellenistic influence on a book that will eventually become accepted as canonical in the Christian Bible. Unlike anything in the TNK, and even moving beyond Ecclesiastes 7:28, Hebrew Sirach 42:14a asserts the superiority, not only of a man over a woman, but even of an evil man over a good woman: “better an evil man than a good woman” (אשה רע איש מטוב טוב). In 42:14b, Hebrew Sirach then laments that a daughter is to be dreaded more than any reproach (חרפה מכול מפחדת ובת). The Greek paraphrase of LXX Sirach 42:14 is even stronger: “Better an evil man than a woman who does good; a woman brings shame and disgrace” (κρείσσων πονηρία ἀνδρὸς ἢ ἀγαθοποιὸς γυνή, καἰ γυνὴ καταισχύνουσα εἰς ὀνειδισμόν).43 All this follows suit, of course, from Sirach’s reading of Genesis 3 in the light of Hesiod’s Pandora, as seen in Sirach 25:24: “From a woman sin had its beginning; because of her, we all die.”44 The Testament of Reuben, a work of Hellenistic Jewish origin dated somewhere between 100 BCE-100 CE, represents an even greater departure from more traditionally positive Jewish portrayals of women prior to the advent of Hellenism: “For women are evil my sons, and by reason of their lacking authority or power over man, they scheme treacherously how they might entice him to themselves by means of their looks. And whomever they cannot enchant by their appearance they conquer by a stratagem” (5:1–3).45 To be sure, Ecclesiastes 7:28 and Sirach 42:14 are notable exceptions in the canon, as nowhere else in the Jewish Scriptures is there a universally applied negative stereotype of women.46 It is likewise significant that the Testament of Reuben never gained canonical acceptance in either Judaism or Christianity. With that in mind, perhaps the best way to read Ecclesiastes 7:28 and Sirach 42:14 is in the light of the more balanced portrayals of women found in the TNK, composed as they were prior to the rise of Hellenism and its profound influence on the eastern Mediterranean and Levant, including Judaism and its literature.47

6. Recovering Post-Exilic Esteem for Israel’s “Wise Women” and the Real Fool of Prov. 9:1–18

In summary, with the spread of Hellenism and its mythological and philosophical literature equating women as a whole with the entrance of evil in the world, Scripture in general—and Proverbs in particular—will become read and interpreted through a Hellenistic Jewish (and later Greco-Roman Christian) lens which blurs in a substantial way what would otherwise be a positive biblical portrait of women in the TNK.48 Due consideration must therefore be given to the legitimate concerns of feminist scholarship troubled by the negative portrayal of women in antiquity and the continued and pervasive influence of such a portrayal upon Western thought, religion, politics, and culture. Even so, one must still nonetheless question Yee’s comment that Dame Folly, as the final editors of Proverbs present her, is the “personification in a woman’s form of all that is evil and destructive” (Yee 1989, p. 66), simply because Folly is not the only such personification. Lady Wisdom, too, as Folly’s foil, personifies “in a woman’s form” all that is good and life-giving; she is emulated by the God-fearing “woman of strength” (31:10) who teaches wisdom49 to her children (1:8; 6:20; 31:1–9) and more than capably cares for her family and manages her household (31:10–31). The juxtaposition of the two female figures Wisdom and Folly represents poetically, in Deuteronomistic categories, the basic choice for good or evil, for fidelity to YHWH’s legitimate demands or a rejection of those demands, a choice for life or death (Dt. 30:15,19). The fact that the prolog itself begins with a discourse to avoid the enticements of “sinners” in language that imagines men as sinners who, like Folly, also entice to evil (Prov. 1:10–18), is evidence that the author of Proverbs has no intention of singling out women as seductresses. On the contrary, a careful study of Proverbs reveals a notable balance between caricatures of both men and women (Bellis 2024, pp. 86–87). Not only do men entice other men to do evil in Proverbs but, even worse, a “devious man” (נָלוֹז)50 is “an abomination to the Lord” (3:32), strong language which is nowhere in Proverbs applied directly to a woman. Further, nowhere in the prolog or the rest of Proverbs is there any indication that Dame Folly or אֵשֶׁת כְּסִילוּת (ʾēšeṯ kᵉsîlûṯ) is representative of all womankind—again, in contrast to Ecclesiastes 7:28, Sirach 42:14, and the Testament of Reuben 5:1–3. Instead, the “wife of one’s youth,” described in glowing terms, is to be valued and held onto (Proverbs 5:15–19) since “to find a wife is to find a good thing,” a sign of God’s good will (18:22), even as “a prudent wife” is a genuine gift of God (19:14).51 Indeed, a “gracious woman” is honorable (11:16) while “the woman who reveres God is to be praised” (31:30).

In contrast to Folly, therefore, to choose Wisdom is the moral equivalent of making a choice for fidelity both to one’s marital commitment and to the God of Israel. Thus, for the Jewish sage, wisdom implies a choice for one’s own wife over another woman, one’s own God over a foreign god, a woman of one’s own people who “fears the Lord” (Prov. 31:30) over a woman outside the community of Israel who does not. To choose Wisdom is to make those practical choices which keep the sage within the community of Israel and in exclusive fidelity to one’s wife in parallel with Israel’s exclusive covenant with her God.52 Folly, then, at least in Proverbs, is not really representative of womankind in general. On the contrary, Folly is that which would distract the sage from fidelity to his wife and his God, a fidelity which, ultimately, far beyond the allure of easy sex and facile religious practice devoid of commitment or demands, will alone lead to true enjoyment of all the good things life has to offer.

To put it another way, when read on its own terms, in its own post-exilic Jewish world, Proverbs represents a clear advancement in the status of women over that of contemporary Greek antiquity where a wife’s value lay only in the legitimate male heirs she could provide for her husband who, in turn, owed her no exclusive sexual fidelity, either culturally, religiously, or legally; on the contrary, outside of Judaism, the cultural expectation in Greek and Roman households was that a wife would be exclusively sexually faithful to her husband but without any reasonable expectation of her husband’s reciprocal exclusive sexual fidelity to her.53

Hence, for Proverbs, the only woman that is not “proper to Israel” (to use Camp’s terms) is the non-Jew who will not abandon the gods of her people for the God of Israel.54 Accordingly, since “the beginning of wisdom is reverence for the LORD” (9:10), Wisdom is to be found in that dedicated, industrious, and faithful “woman of strength” who reveres the God of Israel by lovingly providing for her family and generously caring for the poor, day in and day out (Proverbs 31:10–31). Wisdom is to be found in her teaching (Prov 1:8–9; 6:20; 31:1), and her children are commanded to treat her with care and love into her old age (23:22,25). In Proverbs, so esteemed and valued is such a wise woman that her children are sternly warned against failing to show her due respect (10:1; 15:20; 19:26; 20:20; 28:24; 30:17). In short, despite later interpreters who read Proverbs through the distorted lens of Greek misogyny, and notwithstanding the doubts of some feminist scholarship, Proverbs itself assures us that so wise a woman can indeed be found and that, moreover, her husband should not be fool enough to lose her.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This being said, however, we would be wrong to presume that all women remained outside the boundaries of the literate elites of antiquity. Marsman ([2003] 2021, p. 724), for example, reports that “professional female scribes… are attested in Mesopotamia and Egypt, and possibly in the Hebrew Bible, but their occurrence is rare and they often, if not mostly, seem to have worked for other women.” See also Plant (2004). Regarding the androcentrism of Proverbs, see note 52 below. |

| 2 | For example, the Malleus Maleficarum (“The Hammer of Witches”), written by two Dominican theologians and first published in 1486 as a guidebook for the Inquisition in its identification and prosecution of witches, draws from (among other biblical, Christian, and classical sources) the lurid portrayal of the adulterous woman of the Book of Proverbs, even directly referring to it: “For men are caught not only through their carnal desires, when they see and hear women… All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable. See Proverbs XXX: There are three things that are never satisfied, yea, a fourth thing which says not, ‘It is enough’; that is, the mouth of the womb… It is sufficiently clear that it is not matter for wonder that there are more women than men found infected with the heresy of witchcraft. And in consequence of this, it is better called the heresy of witches than of wizards, since the name is taken from the more powerful party. And blessed be the Highest Who has so far preserved the male sex from so great a crime…” (Question 6, Part One, “Why it is that Women are chiefly addicted to Evil Superstitions” in Kramer and Sprenger (1971), p. 41. Sadly, during the two and a half centuries following its original publication, approximately 300,000 women were executed as witches by ecclesial authorities, both Protestant and Catholic, with some estimates as high as nine million. See Ewen (1929); Dworkin (1973). For a brief review of the use of biblical wisdom literature in Malleus Maleficarum, see Fontaine (1998, pp. 137–68); Noonan (1998, pp. 169–74), both in Wisdom and the Psalms, Ahalya Brenner and Carole Fontaine, eds. (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press 1998). |

| 3 | Waltke (2004, pp. 31–35) is a notable exception. Pointing to Kitchen (1977, pp. 69–114), Waltke argues in favor of Solomonic authorship, stating that “no scholar has refuted Kitchen’s data and arguments that Solomon composed and compiled Proverbs 1–24” and that “labeling Proverbs a pseudepigraphon is the real fiction.” Blenkinsopp (1995, p. 19), however, believes that Proverbs is a pseudonymous work rather than pseudepigraphal: “Anonymity is normal in the ancient world. Pseudonymity arises in response to the need to legitimate and confer authority on a composition by linking it with a normative history and a great figure in the tradition. So, for example, Deuteronomy is attributed to Moses and Psalms to David. The practice of putting one’s name to a book is attested only towards the end of the biblical period, the earliest extant example being Jesus ben Sira (Ecclus. 50:27). While the sayings of Agur and Lemuel are the exception in Proverbs in this respect, by the time of the Mishnah (c. 200 CE) it was common.” |

| 4 | Albright (1955, p. 709); Dahood (1968, pp. 123–52); Clifford (1975, p. 299). In support of Albright’s conclusions is Lang (1986, p. 4) who argues that post-exilic vocabulary is notably absent in the prolog. For an argument against Albright’s conclusions, see Day (1995, p. 69). Lang (2002, p. 26) suggests that the Book of Proverbs “may qualify as the oldest extant piece of Hebrew literature,” and that it was already quite ancient by the time of the prophet Amos, in the eighth century BCE. |

| 5 | See Ansberry (2024, pp. 54–56). See also Perdue’s discussion on the dating of Proverbs, both as a composite document and in its final post-exilic form (Perdue 2000, pp. 2–3); Hadley (1995, p. 239); Blenkinsopp (1991, p. 466); Murphy (1985, p. 11). |

| 6 | John Day points out that Ma’at is not personified in Egyptian wisdom literature, and when she is personified (outside of wisdom literature), she “never speaks in the first person, or indeed at all” as does Lady Wisdom of Proverbs. For a helpful summary of the Ma’at parallels with Lady Wisdom, see (Blenkinsopp 1995, p. 161). |

| 7 | Day (1995, p. 69), however, dismisses Lang’s assertions, insisting that there is not a “scrap of evidence that any such goddess ever existed.” |

| 8 | Albright (1955, p. 8) believes that חָכְמוֹת is a vestige of an older Phoenician word. Waltke (2004, p. 197), however, takes חָכְמוֹת as either an intensive plural or an abstract noun. As the plural, “Wisdoms,” חָכְמוֹת used in reference to Wisdom as a personification is found only in Proverbs 1:20 and 9:1. Elsewhere it can be reasonably translated as a plural adjective, which is its usual grammatical meaning: Judges 5:29 (“wisest of princesses”); Ps 49:4 (“wise things”); Prov. 14:1 (“wisest of women”); 24:7 (“wise things”). Not surprisingly, in Proverbs 1:20 and 9:1, the LXX (Σοφία), VUL (Sapientia), and the Targum Proverbs (TgProv, חכמתא) use the singular noun for wisdom, not the plural. |

| 9 | Only twice in Proverbs 9 is “Wisdom” referred to: in 9:1 as חָכְמוֹת (ḥōkhmōt, the feminine plural noun “wisdoms”), and in 9:10 as חָכְמָה (ḥōḵmah, the feminine singular noun “wisdom”). |

| 10 | חַכְמוֹת נָשִׁים בָּנְתָה בֵיתָהּ וְאִוֶּלֶת בְּיָדֶיהָ תֶהֶרְסֶנּוּ. In an understandable attempt to distance “folly” from the feminine, the Jewish Publication Society TNK (2003) offers a non-gendered translation of this verse (“its hands.”). The Hebrew, however, reads “her hands,” as translated here. |

| 11 | Literally, “slaughtered her slaughter” (טָבְחָה טִבְחָהּ). The root טבח is used for non-sacrificial meals; a similar root, זבח, would be used in reference to an act of sacrifice. While this meal is thus not presented in the Hebrew text as a cultic one, the LXX translates this as ἔσφαξεν τὰ ἑαυτῆς θύματα, with an undeniable connotation of “sacrifice.” For example, in Homer, the verb ἔσφαξεν (σφάζω) is used in a sacrificial sense (Od. 1.92; cf. 9.46; 23.305; Il. 1.459; 9.467); the word θύματα similarly refers to sacrificial offerings or sacrificed meat. Interestingly, rather than following the non-cultic context of the Hebrew text, the VUL follows the sacrificial interpretation of the LXX: Immolavit victimas suas. |

| 12 | While both the TgProv (טליתהא) and VUL (ancillas) follow the Hebrew text, the LXX prefers to change the “servant girls” into male servants (δούλους). |

| 13 | In 8:2 we are told that she takes her stand at the “topmost heights” (בְּרֹאשׁ־מְרוֹמִים). |

| 14 | 9:14 uses the same language as 9:3: מְרֹמֵי קָרֶת. See the discussion below on the “high places” associated with Folly. |

| 15 | In 9:5, the LXX adds “for you” (ὑμῖν); the VUL follows suit with the second person plural “vobis.” The TgProv, not surprisingly, follows the Hebrew closely: תו אכלו לחמי ואשׁתיו חמרא דמזגית. |

| 16 | All translations are the author’s own, unless otherwise indicated. |

| 17 | The literal meaning of פְתָאִים, a masculine plural noun, is “simple ones” or “dullards” (8:5; 14:18; 27:12), e.g., foolish, immature, or naïve (male) companions. Unlike its use in Ps. 116:16, in Proverbs, its connotation is negative. The LXX translates with a feminine singular noun, ἀφροσύνην, “thoughtlessness,” “foolishness,”or “senseless,” which completely eliminates the image of foolish male companions implied by the Hebrew masculine plural פְתָאִים. Following the LXX, the VUL translates infantiam, “childishness,” “immaturity.” |

| 18 | Here the word for “fools” is כְסִילִים, with the same root, כסל, as the word used for Dame Folly in 9:13: אֵשֶׁת כְּסִילוּת. See the discussion below. |

| 19 | Prov 1:7, 29; 2:5; 3:7; 8:13; 9:10; 10:27; 14:26f; 15:16, 33; 16:6; 19:23; 22:4; 23:17; 24:21; 29:25. |

| 20 | For a helpful summary of the debate, see Byargeon (1977, pp. 367–75). The LXX offers additional material to these verses, what Cook (1994) explains as an “effort to avoid misunderstanding of [the] Hebrew Vorlage.” |

| 21 | Except in the LXX. See Cook (1994, p. 472). |

| 22 | The Dictionary of Classical Hebrew, David J. A. Clines, editor, Volume IV (ל–י), Sheffield, 2011, 444 (from here on abbreviated to DCH). (Clines 2011). |

| 23 | Avraham Even-Shoshan, ed. A New Concordance of the Bible: Thesaurus of the Language of the Bible (Hebrew and Aramaic Roots, Words, Proper Names, Phrases and Synonyms), Jerusalem: Kiryat Sefer, 1998, 555 (Even-Shoshan 1998). |

| 24 | Francis Robinson Brown, Edward Driver, S. R. Briggs, The New Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament (Brown et al. 1979), 492. See also DCH, p. 444. |

| 25 | Ps 49:11; 92:7; 94:8; Prov 1:22, 32; 3:35; 8:5; 10:1, 18, 23; 12:23; 13:16, 19f; 14:7f, 16, 24, 33; 15:2, 7, 14, 20; 17:10, 12, 16, 21, 24f; 18:2, 6f; 19:1, 10, 13, 29; 21:20; 23:9; 26:1, 3ff; 28:26; 29:11, 20; Eccl 2:14ff; 4:5, 13, 17; 5:2f; 6:8; 7:4ff, 9; 9:17; 10:2, 12, 15. |

| 26 | Depending on the vocalization, אשׁת רע could also be read as the “wife of a friend,” “neighbor,” or “fellow” (רע), which explains the Septuagint’s translation as γυναικὸς ὑπάνδρου. However, the VUL (muliere mala) and the TgProv (איתתא בישׁא) both follow the Masoretic reading. Both the NABRE (“another’s wife”) and NRSV (“the wife of another”) follow the LXX while the JPS, of course, follows the MT, translating as “evil woman.” |

| 27 | It is worth noting that זָרָה (“strange,” “outsider”) and נָכְרִיָּה (“foreign”) are not exclusively reserved for women. Camp (2000, pp. 40–41) observes that these terms “have a variety of connotations, often overlapping, in the Hebrew Bible. They can refer to persons of foreign nationality, to persons who are outside one’s own family household, to persons who are not members of the priestly caste, and to deities or practices that fall outside the covenant relationship with YHWH. |

| 28 | These would be metaphoric references to sexual relations. Proverbs 5:15 advises the young man to “drink from your own cistern,” which in context refers to keeping sexual relations limited to his own wife rather than seeking sexual satisfaction elsewhere. |

| 29 | . וְיָשְׁבָה לְפֶתַח בֵּיתָהּ עַל־כִּסֵּא מְרֹמֵי קָרֶת The TgProv uses the equivalent of the Hebrew כִּסֵּא, which can have the connotation of “throne” (TAR: על תרע ביתה על כורסיא רמא ועשׁינא ויתבא). In contrast, the LXX (ἐκάθισεν ἐπἰ θύραις τοῦ ἑαυτῆς οιἔκου ἐπἰ δίφρου) and the VUL (sedit in foribus domus suæ, super sellam in excelso urbis loco) use a word for “seat,” or “chair” rather than “throne.” Similarly, the NRS and NAB both translate as כִּסֵּא “seat.” |

| 30 | Gen 41:40; Exod 11:5; 12:29; Deut 17:18; Judg 3:20; 1 Sam 2:8; 2 Sam 3:10; 7:13, 16; 14:9; 1 Kgs 1:13, 17, 20, 24, 27, 30, 35, 37, 46ff; 1 Kings 2:4, 12, 19; 1 Kings 2:24, 33, 45; 3:6; 5:19; 7:7; 8:20, 25; 9:5; 10:9, 18f; 16:11; 22:10, 19; 2 Kgs 10:3, 30; 11:19; 13:13; 15:12; 25:28; 1 Chr 17:12, 14; 22:10; 28:5; 29:23; 2 Chr 6:10, 16; 7:18; 9:8, 17f; 18:9, 18; 23:20; Esth 1:2; 3:1; 5:1; Job 26:9; 36:7; Ps 9:5, 8; 11:4; 45:7; 47:9; 89:5, 15, 30, 37, 45; 93:2; 97:2; 103:19; 122:5; 132:11f; 9:14; 16:12; 20:8, 28; 25:5; 29:14; Isa 6:1; 9:6; 14:9, 13; 16:5; 22:23; 47:1; 66:1; Jer 1:15; 3:17; 13:13; 14:21; 17:12, 25; 22:2, 4, 30; 29:16; 33:17, 21; 36:30; 43:10; 49:38; 52:32; Lam 5:19; Ezek 1:26; 10:1; 26:16; 43:7; Jonah 3:6; Hag 2:22; Zech 6:13. |

| 31 | In Zech. 6:13 (MT), both king and priest are on a כִּסֵּא, whereas the LXX resists placing the priest on a throne with the king, instead putting him “at his right.” |

| 32 | In both the case of Eli and Elisha, the LXX translates כִּסֵּא as δίφρος, “seat,” “chair,” “stool” (VUL: sella). In all other 112 usages of כִּסֵּא, the LXX translates θρόνος, “throne” (VUL: solium, “seat,” “chair,” “throne”). |

| 33 | 1 Kings 22:19; 2 Chron. 8:18; Ps. 9:5,7; 11:4; 45:7; 47:9; 89:15; 93:2; 97:2; 103:19; Is. 6:1; Is.66:1; Jer. 49:38; Lam. 5:19; Ez. 43:7. |

| 34 | (.מִמַּעַל לְכוֹכְבֵי־אֵל אָרִים כִּסְאִי וְאֵשֵׁב בְּהַר־מוֹעֵד בְּיַרְכְּתֵי צָפוֹן) In Canaanite mythology, Mt. Zaphon, located near the Orontes River in northern Syria, was the mountain of the gods (Hector Arevalos, “Mount Zaphron,” ABD 6:1040). |

| 35 | For example, Perdue (2000, pp. 132–33) reads the שְׁלָמִים (šᵉlāmîm) sacrifice, offered by the adulterous woman “dressed like a harlot” in Proverbs 7:14 (that is, Dame Folly), as a sacrifice to a fertility goddess, even as he wants to give this chapter of Proverbs a post-exilic date. However, Day (1995, p. 69) points out that any insistence upon a post-exilic date for Proverbs 1–9 would preclude an association of Dame Folly with cultic prostitution, when such a practice was less in evidence. |

| 36 | Linking sexual partnerships with foreign women with the worship of the women’s pagan gods, Numbers 25 describes the harsh consequences meted out against those Israelite men who did not marry within Israel. |

| 37 | Hesiod, The Homeric Hymns, and Homerica Selections, Hugh G. Evelyn-White, trans., Loeb Classical Library, Cambridge: Harvard University, 1995, 3–9. |

| 38 | For Hesiod’s widespread impact in antiquity, see Thomas Alan Sinclair, ed., Hesiod: Works and Days (London: Macmillan, 1932), xxxvi. For Hesiod’s profound influence on later Hellenistic Jewish and Greco-Roman Christian biblical interpretation, particularly in the way his story of Pandora becomes imposed upon biblical Eve, see also Phipps (1988). For a discussion on Hesiod as the origin of misogyny in Western literature, see Fantham et al. (1994, pp. 39–42). For a discussion on the pervasive and universally applied pejorative stereotypes against women in Greco-Roman antiquity, see Cantarella (1987). |

| 39 | This also includes, but is not limited to, the profound influence of Plato and Aristotle on the Greco-Roman world and Christianity. For example, Plato rewrites Hesiod’s mythical misogyny by transforming it into his own myth of human origins (the Timaeus), where the souls of men (ἄνδρες), if they lead a just life, will return to the distant planet from whence they came and, if they lead an immoral life, will be reincarnated as women. In other words, by her very conception, a woman is morally inferior to a man. See (Plato 1975). Plato’s pupil, Aristotle, going beyond the language of mythology, offers “scientific” reasons for the inherent moral and physical inferiority of women as “misbegotten males” in his treatise On the Generation of Animals, accepted well into the Roman period as a medical textbook. See Aristotle, GA, 737a). Regarding the widespread distribution of Aristotle’s writings throughout the Hellenistic world, see Dean-Jones (1994, pp. 21–22). |

| 40 | For a discussion regarding a date for the earliest text of 1 and 2 Samuel in the early monarchy sometime in the tenth century BCE, as well as later redactions during the time of Josiah in the late seventh century BCE and, finally, a Deuteronomistic redaction in the sixth century BCE, see Alter (2013, p. 226). |

| 41 | While scholars today, in general, would give Proverbs (in its final form, at least) a post-exilic date, no scholar argues for a date after the Persian period. In other words, Proverbs is unquestionably dated prior to the spread of Hellenism into the Levant. For a discussion on the dating of Proverbs, see Section 2 above. |

| 42 | For a Hellenistic dating of Ecclesiastes, see Ceresko (1999, pp. 92–93). |

| 43 | Perhaps because LXX Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) is a book known and read in the early Church (with Hebrew copies discovered only in the last 130 years), the NRSV translates this verse according to the LXX: “Better is the wickedness of a man than a woman who does good; it is woman who brings shame and disgrace.” The NABRE, however, in a way that goes beyond the LXX Sirach 42:14 in search of a pastorally friendly translation, offers a much softer paraphrase in verse 14a and then gives a nod in verse 14b to Hebrew Sirach: “Better a man’s harshness than a woman’s indulgence, a frightened daughter than any disgrace.” |

| 44 | Whereas the original story in Gen 3:1–6 shows both the first man as well as the first woman equally complicit in the first sin, with the woman’s sin being one of commission while the man’s sin is omission (he is a silent accomplice, offering no objection to the woman eating the forbidden fruit or passing it to him), there is no such consideration in Sirach for the first man’s silence, complicity, or failure to exercise moral responsibility, initiative, and leadership. See Trible (1978, p. 113). |

| 45 | The Testament of Reuben, part of a larger work known as “The Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs,” has traditionally been regarded as a Hellenistic Jewish text. For a fascinating discussion of its late Second Temple Jewish contexts, see M.D. Jonge (2003), chapters five and seven; for a discussion on its Christian transmission, see chapter six. |

| 46 | Sirach, also known as Ecclesiasticus (i.e., “the Church’s book”), was popular among early Christians and eventually added to the canon by the late fourth century CE. Rabbinic Judaism never accepted it into the Jewish canon. For a discussion of the writings included and excluded from the Jewish and Christian canons of Scripture, see Collins et al. (2020). |

| 47 | For a thoughtful and balanced way to read the women in the TNK, see the work of notable Jewish biblical scholar Frymer-Kensky (2002). See also Meyers (2013), especially the epilogue, “Beyond the Hebrew Bible,” pp. 203–12. |

| 48 | It is beyond the scope of this paper to offer further examples detailing the negative and pervasive influence of Greek misogyny on Jewish and Christian biblical interpretation from the Hellenistic period on. However, for an insightful discussion of the pervasive influence of Greek misogyny on later Jewish and Christian biblical interpretation in a way that deviates significantly from the TNK, see Phipps (1988); Meyers (2013, pp. 203–12); Parker (2013). See also Schroer (2000) and the distinction she makes between the figure of Lady Wisdom in Proverbs and how Lady Wisdom becomes distorted and masculinized in Sirach (a text from the Hellenistic period). |

| 49 | Literally, “torah,” “teaching” (“the ‘torah’ or ‘teaching’ of your mother”: תּוֹרַ֥ת אִמֶּֽךָ), which in later Second Temple Judaism becomes understood as “Torah,” or “the Law” (“instruction”) of Moses. |

| 50 | As a noun, נָלוֹז is also found in Prov 14:2. In both occurrences in Proverbs, this word is used as a masculine noun, in other words, only in reference to a man, never a woman. |

| 51 | Contrast the injunction in Proverbs 5:15–19 to value, be faithful to, and even “rejoice in” one’s wife with (1) fourth century BCE Pseudo-Demosthenes: “We have wives to bear us children, concubines [pallakas] for the daily care of our persons, mistresses [hetairas] we keep for the sake of pleasure” (Against Neaera 59.122); (2) Fifth century BCE Aristophanes, Lysistrata 1038–9: “A true saying and well-said: you can’t live with the cursed creatures or without them,” quoted in note 25 of Lefkowitz and Fant (2016, p. 156, note 25). An echo of Aristophanes can be found centuries later in the Roman world. According to Livy (Per. 59), in an address to Roman senators, Augustus quoted the comment of second century BCE Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus, “If we could survive without a wife, citizens of Rome, all of us would do without that nuisance; but since nature has so decreed that we cannot manage comfortably with them, nor live in any way without them, we must plan for our lasting preservation rather than for our temporary pleasure” (Fr. 6 in E. Malcovati, ed., Oratorum Romanorum Fragmenta, Turin, 1955), cited in Lefkowitz and Fant (2016, p. 128). |

| 52 | As acknowledged from the outset, the presentation of wisdom vs. folly in Proverbs is undeniably androcentric. That said, androcentrism (written by men, for men, with a focus on men’s concerns), while endemic to ancient literature in general, should not be confused with misogyny (contempt and disdain for women generally, the belittling of women in general, or an ingrained bias against women). Accordingly, a fair reading of these ancient texts will take into consideration that which can be found in them which moves the tradition forward despite the androcentric world of the biblical author. Such a reading emerges only when the text is read on its own terms, in its own language and context, according to its own time and place in history, not ours. That women are presented in Proverbs as possessors of wisdom (see the discussion below) and worthy of their husband’s exclusive fidelity (Prov 5:15–19) are subtle correctives that should make us take notice if only because such a presentation is without parallel among ancient Judah’s Gentile neighbors; nothing like it will be found in the Gentile world until the Christian period, thanks to Christianity’s inheritance of Jewish sexual ethics. As the “subtle correctives” in the biblical text gain growing acceptance, they can move the human family forward in important ways. For example, in a way that the author of Proverbs 5:15–19 could only applaud, Augustine of Hippo (formerly a womanizer until his conversion to Christianity) as a Gentile Christian bishop demands that husbands be mutually sexually faithful to their wives (Excellence of Marriage, 6); what is more, Augustine goes even further by commanding Christian wives not to tolerate their husband’s infidelities (Sermon 392). (See note 53 below). |

| 53 | In the Gentile world, adultery was defined as sexual relations of a married woman with a man not her husband. With this definition, a married man could have relations with anyone he wanted and it was not considered adulterous unless he had relations with a married woman, not his wife. Plutarch, for example, while insisting on a wife’s sexual fidelity to her husband, advises wives to tolerate their husband’s sexual escapades with other women. Plutarch’s double-standard is representative for the Gentile world around the Mediterranean (Advice to Bride and Groom, 140:16); See also Pomeroy (1999). For a discussion on views regarding sexual morality in ancient Greece and Rome, see McClure (2002) and Langlands (2006). It is not until Christianity, with its inheritance of Jewish sexual ethics that require also a husband’s mutually exclusive sexual fidelity to his wife (Prov 5:15–19; Malachi 2:10–17; summarized in Jesus’s teachings in Mt 5:28,32; 19:9; Mk 10:11–12; Lk 16:18; and reinforced in Paul’s teachings to his Gentile converts in 1 Cor 5–7), that adultery becomes redefined as sexual relations of either partner with someone not one’s spouse. (See note 52 above). |

| 54 | In contrast to the “foreign woman” of Proverbs is the Moabite woman Ruth who does leave her people and her people’s gods to embrace the Israelite people and their God. The Book of Ruth, and its story of Ruth’s incorporation into King David’s family tree, offers a way out of the strict demands of post-exilic biblical literature to eschew all marriage with non-Jewish women. |

References

Primary sources

Aristotle. 1953. Generation of Animals. Translated by A.L. Peck. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Augustine of Hippo. 1995. Sermon 392: “To Married Couples.” In The Works of St. Augustine: Sermons. Translated by Edmund Hill. Hyde Park: New City Press, vol III/10, pp. 341–400.Augustine of Hippo. 1999. Excellence of Marriage. In The Works of Saint Augustine. Translated by Ray Kearney. Edited by David G. Hunter. “Marriage and Virginity.” New York: New City Press, vol. 9.Avalos, Hector. 1992. Mount Zaphon. In Anchor Bible Dictionary. Edited by David Noel Freedman. 6 vols. New York: Doubleday, vol. 6, pp. 1040–41.Camp, Claudia V. 1987. Woman Wisdom as Root Metaphor: A Theological Consideration. In The Listening Heart: Essays in Wisdom and the Psalms in honor of Roland E. Murphy. Edited by Kenneth G. Hoglund. Sheffield: JSOT Press, pp. 45–76.Hesiod. 1932. Works and Days. Edited by Thomas Alan Sinclair. London: Macmillan.Hesiod. 1995. Hesiod, the Homeric Hymns, and Homerica Selections. Translated by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University.Plato. 1975. Timaeus, Critias, Cleitophon, Menexenus, Epistles. Translated by R. G. Bury. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.Plutarch. 1928. Advice to Bride and Groom. In Plutarch’s Moralia II. Translated by Frank Cole Babbitt. LCL. The Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Plutarch. 1999. Plutarch’s Advice to the Bride and Groom and a Consolation to His Wife. Edited by Sarah B. Pomeroy. New York: Oxford University Press.Pseudo-Demosthenes. 1939. Against Neara 122. In Demosthenes: Private Orations III. Translated by A.T. Murray. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard.Secondary sources

- Ackerman, Susan. 1989. ‘And the Women Knead Dough’: The Worship of the Queen of Heaven in Sixth-Century Judah. In Gender and Difference in Ancient Israel. Edited by Peggy L. Day. Minneapolis: Fortress, pp. 109–24. [Google Scholar]

- Albright, W. F. 1955. Some Canaanite-Phoenician Sources of Hebrew Wisdom. In Wisdom in Israel and in the Ancient Near East. Edited by Martin Noth, D. Winton Thomas and Harold H. Rowley. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Alter, Robert. 2013. Ancient Israel: The Former Prophets Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings. New York: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Ansberry, Christopher B. 2024. Proverbs. In Zondervan Exegetical Commentary on the Old Testament: A Discourse Analysis of the Hebrew Bible. Edited by Daniel I. Block. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Bellis, Alice Ogden. 2024. Gender Roles and Translation in the Book of Proverbs. The Bible Translator 75: 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph. 1991. The Social Context of the ‘Outsider Woman’ in Proverbs 1–9. Biblica 72: 457–73. [Google Scholar]

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph. 1995. Wisdom and Law in the Old Testament: The Ordering of Life in Israel and Early Judaism, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Francis Robinson, Edward Driver, and S. R. Briggs. 1979. The New Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Byargeon, Rick W. 1977. The Structure and Significance of Proverbs 9:7–12. Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 40: 367–75. [Google Scholar]

- Camp, Claudia V. 2000. Wise, Strange and Holy: The Strange Woman and the Making of the Bible. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cantarella, Eva. 1987. Pandora’s Daughters: The Role and Status of Women in Greek and Roman Antiquity. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ceresko, Anthony R. 1999. Introduction to Old Testament Wisdom: A Spirituality of Liberation. Maryknoll: Orbis. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, Richard J. 1975. Proverbs 9: A Suggested Ugaritic Parallel. Vetus Testamentum 25: 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, Richard J. 2016. Proverbs: A Commentary. The Old Testament Library. Louisville: Westminster John Knox. [Google Scholar]

- Clines, David J. A., ed. 2011. The Dictionary of Classical Hebrew. Volume IV: ל–י. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, John J., Craig A. Evans, and Lee Martin McDonald. 2020. Ancient Jewish and Christian Scriptures: New Developments in Canon Controversy. Louisville: Westminster John Knox. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Johann. 1994. אִשָּׁה זָרָה (Proverbs 1–9 Septuagint): A Metaphor for Foreign Wisdom? Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 106: 458–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, Sidnie. 1998. Lady Wisdom and Dame Folly at Qumran. Dead Sea Discoveries: A Journal of Current Research on the Scrolls and Related Literature 5: 355–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahood, Mitchell J. 1968. The Phoenician Contribution to Biblical Wisdom Literature. In The Role of the Phoenicians in the Interaction of Mediterranean Civilization. Edited by W. A. Ward. Beirut: American University of Beirut. [Google Scholar]

- Day, John. 1995. Foreign Semitic Influence on the Wisdom of Israel and Its Appropriation in the Book of Proverbs. In Wisdom in Ancient Israel. Edited by John Day, Robert P. Gordon and Hugh Godfrey Maturin Williamson. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Dean-Jones, Leslie. 1994. Women’s Bodies in Classical Greek Science. Oxford: Clarendon. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin, Andrea. 1973. Woman Hating: A Radical Look at Sexuality. New York: Feminist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Even-Shoshan, Abraham, ed. 1998. A New Concordance of the Bible: Thesaurus of the Language of the Bible (Hebrew and Aramaic Roots, Words, Proper Names, Phrases and Synonyms). Jerusalem: Kiryat Sefer. [Google Scholar]

- Ewen, C.E. 1929. Witch Hunting and Witch Trials: The Indictments for Witchraft from the Records of 1373 Assizes Held for the Home Circuit A.D. 1559–1736. New York: The Dial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fantham, Elaine, Helene Peet Foley, Natalie Boymel Kampen, Sarah B. Pomeroy, and H.A. Shapiro. 1994. Women in the Classical World. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine, Carole R. 1998. ‘Many Devices’ (Qoheleth 7.23–8.1): Qoheleth, Misogyny and the Malleus Maleficarum. In Wisdom and the Psalms. Edited by Ahalya Brenner and Carole Fontaine. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, pp. 137–68. [Google Scholar]

- Frymer-Kensky, Tikva. 2002. Reading the Women of the Bible: A New Interpretation of Their Stories. New York: Schocken Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hadley, Judith M. 1995. Wisdom and the Goddess. In Wisdom in Ancient Israel. Edited by John Day, Robert P. Gordon and H. G. M. Williamson. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 234–43. [Google Scholar]

- Jonge, Marinus de Jonge. 2003. Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament as Part of Christian Literature: The Case of the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs and the Greek Life of Adam and Eve. Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson. 1977. Proverbs and Wisdom Books of the Ancient Near East: The Factual History of a Literary Form. TB 28: 69–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, Heinrich, and James Sprenger. 1971. The Malleus Maleficarum. Translated by Montague Summers. New York: Dover. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, Bernhard. 1986. Wisdom and the Book of Proverbs. New York: Pilgrim Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, Bernhard. 2002. The Hebrew God: Portrait of an Ancient Deity. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langlands, Rebecca. 2006. Sexual Morality in Ancient Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz, Mary R., and Maureen B. Fant. 2016. Women’s Life in Greece and Rome: A Source Book in Translation, 4th ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University. [Google Scholar]

- Marsman, Hennie J. 2021. Women in Ugarit and Israel: Their Social and Religious Position in the Context of the Ancient Near East. Leiden Boston: Brill. First published 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McClure, Laura K., ed. 2002. Sexuality and Gender in the Classical World: Readings and Sources. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]