Abstract

In the digital age, social media platforms homogenize beauty standards and intricately link clothing choices to social norms and class identities. Grounded in Pierre Bourdieu’s concepts of cultural and social capital, supplemented by Erving Goffman’s theory of stigma, this study examines how social media amplifies pre-existing socio-cultural pressures that influence Turkish women’s decisions to abandon the hijab. The research has practical implications for understanding and addressing hijab abandonment. It employs a qualitative design based on semi-structured interviews with 13 participants, analyzed through a phenomenological approach. The findings reveal that the pursuit of social acceptance and resistance to social exclusion are more decisive factors in hijab abandonment than direct social media influence. While social media serves as a crucial amplifier of aesthetic ideals and a gateway to digital legitimacy, the primary drivers are deeply rooted in the pursuit of social acceptance and resistance to long-standing mechanisms of socio-cultural exclusion, stigmatization, and symbolic violence—processes intensified and mediated through digital platforms. The analysis uncovers the operation of a dual-sided neighborhood pressure, whereby women face scrutiny from both religious communities enforcing idealized piety norms and secular circles perpetuating stigmatizing labels such as backwardness or ignorance. Crucially, participants reported that unveiling was strategically employed as a means of overcoming barriers to professional advancement, gaining access to elite social spheres, and escaping the constant burden of representation. The study concludes that hijab abandonment emerges as a complex strategy of social navigation, where digital platforms act as powerful accelerants of pre-existing class- and identity-based conflicts.

1. Introduction

The hijab remains one of the most visible and potent symbols of individual faith and cultural identity within modern Turkish society. It stands at the center of heated debates concerning women’s modernization, personal freedoms, and the enduring legacy of secularist policies. The act of removing the hijab (unveiling) is rarely a simple individual choice; rather, it is often entangled with historical legacies, including past hijab bans and ongoing social pressures. In this complex landscape, social media emerges as a critical arena where these deeply personal processes gain visibility, become subjects of public debate, and are fundamentally reshaped.

Digital technologies have become inextricably intertwined with daily life across the globe, offering connectivity while presenting complex challenges that reshape social norms and individual identities (Bingaman 2023; Khamis 2024). Social media platforms, in particular, function as powerful agents of transformation, influencing domains ranging from personal aesthetics to religious expression (Campbell 2005). Fashion and clothing once primarily matter of personal preference, now function as curated markers of identity shaped by the relentless pursuit of digital validation (Han 2024). These platforms have also become contested spaces where religious symbols, such as the hijab, are continuously reinterpreted, commodified, and sometimes discarded, reflecting broader tensions between tradition and modernity (Akdemir 2020; Kurmanaliyev et al. 2024).

While a significant body of academic literature explores how social media and modernization processes transform individuals’ relationships with religious symbols (Young et al. 2014; Zaenuri et al. 2020; Arab 2022; Manaf and Wok 2019; Baulch and Pramiyanti 2018), a critical gap remains. Specifically, the role of digital platforms in shaping practices of hijab unveiling remains underexplored, particularly from a theoretical lens that connects online practices to offline structures of power and capital.

This study aims to address this gap through the argument that social media does not operate as an isolated cause of hijab abandonment but rather serves as a catalytic field that intensifies pre-existing socio-cultural pressures. It functions as a platform in which the hijab is increasingly aestheticized; class-based exclusions are digitally reproduced, and the burden of representation is both heightened and contested. Consequently, the decision to abandon the hijab emerges at the intersection of offline social stratification and online performativity. While previous research has explored social media’s impact on body image, fashion, and beauty standards, fewer studies have examined its role in religious practices such as hijab removal. Drawing on Bourdieu, this study frames hijab removal as a practice shaped by the interplay of social and cultural capital within these interconnected digital and real-world fields.

This study establishes its conceptual foundation by integrating Pierre Bourdieu’s theoretical framework with the socio-political and digital dynamics surrounding the hijab in Türkiye. Bourdieu’s key concepts—habitus, capital, and symbolic violence—provide a lens to understand women’s strategic negotiations of identity and social positioning. The hijab is situated within the broader Turkish socio-cultural and political context, where modernization processes and shifting power relations influence its meanings. Social media is considered a digital field that mediates these negotiations, shaping perceptions, aesthetic choices, and practices.

This research is guided by the following overarching question: In what ways do social media, socio-cultural pressures, and the negotiation of cultural and social capital influence Turkish women’s decisions about unveiling the hijab, and how are these processes reflected in their perceptions and practices?

1.1. Conceptual Framework and Literature: Bourdieu, the Hijab, and the Digital Field

1.1.1. Introducing the Bourdieusian Toolkit: Habitus, Capital, and Symbolic Violence

Bourdieu’s concepts form an interconnected whole. Individuals are positioned within specific social fields based on the type and volume of capital they possess. This position shapes their habitus—the system of embodied dispositions, perceptions, and appreciations that structures experience. Capital and habitus provide individuals with an intuitive “practical sense” of what is possible and impossible within a social context. However, these fields of struggle are not neutral; certain forms of capital and habitus are deemed more valuable and symbolic violence—the often-invisible mechanism through which power relations are legitimized—reinforces these hierarchies. This study situates the practice of hijab abandonment at the intersection of these concepts, analyzing it as individuals’ efforts to convert existing capital to acquire a new social position and inhabit a different habitus.

Habitus internalized through socialization, class origin, and life experiences constitues a ‘second nature’ guiding pattern of thought, evaluation and action. This study examines the dissonance between an individual’s habitus derived from a veiled background and the habitus required by new social fields they seek to enter (e.g., a secular professional environment). This internal conflict has been observed in various contexts. For instance, Hopkins and Greenwood (2013) demonstrated how the hijab shapes social experiences of identity and visibility in the UK. Meanwhile, Hamdan (2007) revealed that in France, women adopt the hijab as a means of expressing identity, highlighting the negotiation of habitus in a secular republic. However, this article examines whether veiled women’s desire to belong to a different habitus influences their decisions to abandon the hijab and whether hijabi versions of themselves are accepted within certain social fields.

Bourdieu emphasizes that social struggle is not limited to economic capital (material resources) but also involves social capital (networks and connections) as well as cultural capital (education, diplomas, language skills, manners, and bodily posture-hexis). This study interprets the decision to abandon the hijab as a strategy developed by individuals to overcome barriers encountered in the public sphere, particularly in employment or status, and to gain access to the forms of social and cultural capital valid in these fields. The transformation of the hijab into a form of aestheticized cultural capital is evident in the global rise of the ‘hijabista’ or ‘veiled influencer’ phenomenon (Arab 2022; Baulch and Pramiyanti 2018; Karakavak and Özbölük 2023), where religious symbols intersect with consumer culture and digital visibility.

Symbolic violence is Bourdieu’s critical concept for analyzing domination. It is the process whereby power relations are perceived not as arbitrary but as legitimate and natural. It is a type of violence where neither the perpetrator nor the victim is fully aware; the victim eventually begins to view themselves through the eyes of the oppressor and internalizes the domination. Symbolic violence operates through symbolic means like stigma, exclusion, disdain, and implication. This study aims to shed light on the mechanisms of domination to which veiled individuals are subjected. As a new ‘field’ (Bourdieu 1991), social media functions as a crucial site where symbolic violence is both exercised and resisted. Platforms like Instagram and X are arenas where aesthetic norms (a form of cultural capital) are enforced, often alienating those who do not conform (Bourdieu 1984; Han 2017). Conversely, they also provide spaces for counter-narratives and community support, as seen in online platforms like yalnizyurumeyeceksin.com in Turkiye (Okumuş 2022) or global movements like #NoHijabDay (Syahrivar 2021).

1.1.2. The Hijab in the Turkish Context: From Political Symbol to Digital Performance

In Türkiye, the hijab occupies a complex position at the intersection of individual, social, and political dimensions (Şişman 2015; Göle 2019). Since the founding of the Republic, the female body has been central to the ideology of secular modernization. From the 1980s onwards, hijab debates have been framed through the dichotomy of the “modern, liberated republican woman” versus the “pious, veiled woman,” thereby positioning the hijab not merely as a religious practice but as a marker of social identity, class, and embodied cultural capital. During this period, women wearing the hijab faced bans in universities and public institutions, and debates focused intensely on the female body (Gemici 2023). These restrictions created significant tensions between individuals and the state, profoundly affecting women’s social and psychological well-being (Navaro-Yashin 2002). Moreover, the headscarf was banned on the grounds that it was considered a “political symbol”.

With the rise of social media, perceptions and practices of the hijab have undergone further transformation. Social media has altered the practice of the hijab into a hybrid field that integrates personal belief, fashion, lifestyle, and digital performance. This digital reconversion of capital is evident in the diversification of veiling styles and the popularity of hijab fashion (Sayan-Cengiz 2018; Aygün 2022), which both challenges and, at times, reinforce existing class and cultural hierarchies. This digital transformation has also made the act of unveiling more visible. Additionally, social media campaigns on X and Instagram illustrate hijab removal trends. While hashtags such as #HandsOffMyHijab respond to hijab bans, hashtags including #FreeFromHijab, #MyStealthyFreedom, and #NoHijabDay allow women to publicly express their decision to remove the hijab (Reuters 2021; Syahrivar 2021). In Turkiye, trends such as the #10yearchallenge, where women shared images of their past veiled selves after removing the hijab, have sparked significant public debate (Kalafat 2019).

1.1.3. Expanding the Framework: Stigma, Dual-Sided Neighborhood Pressure, Perfect Muslim Woman Stereotype, and the Burden of Representation

This analysis is not limited to the Bourdieusian framework. Based on our empirical findings, we also draw on Erving Goffman’s concept of ‘stigma’ to better explain the management of a ‘spoiled identity’ (Goffman 1963). Besides, in the Turkish context, we employ Şerif Mardin’s notion of ‘neighborhood pressure’ (mahalle baskısı) to capture the communal dynamics of social control (Mardin 2006; Çakır 2008).

Furthermore, the concept of the ‘burden of representation’ (Ataman and Sağırlı 2024) complements Bourdieu’s notion of symbolic violence, describing the psychological pressure on veiled women to flawlessly represent an entire identity group. Ultimately, this study proposes the concepts of ‘dual-sided neighborhood pressure’ which describes the dual mechanism of domination women face from both religious and secular communities, and the ‘perfect Muslim woman stereotype’ which defines the idealized norms operating in this process. These concepts work with Bourdieu’s toolkit to reveal the multi-layered nature of social pressure and identity negotiation.

In conclusion, Bourdieu’s interconnected set of concepts offers an analytical depth for understanding the practice of hijab abandonment, moving it beyond simplistic narratives of ‘loss of faith’ or ‘personal liberation’ to read it as a complex social strategy entangled in struggles over capital, habitus transformation, and symbolic violence. This framework lends visibility to the individual’s internal conflicts and the surrounding power structures, social norms, and mechanisms of inequality.

However, while extensive scholarship examines the impact of social media on hijab fashion (Baulch and Pramiyanti 2018; Kavakci and Kraeplin 2017), critical gaps remain regarding how digital platforms reconfigure the practices of unveiling, particularly through a Bourdieusian lens that connects online practices to offline structures of capital and power. This study aims to fill this gap by analyzing hijab abandonment in Turkey as a complex social strategy situated at the intersection of digital culture, social memory, and the pursuit of legitimacy within multiple, often conflicting, fields.

The practice of wearing the hijab in Turkey exposes women to diverse experiences in social life, which in turn shapes their psychological and social well-being. Studies on the hijab indicate that the issue is influential across social, psychological, and political contexts. Some perspectives suggest that the hijab can be used as a mechanism of control by men over women in society (Mernissi 1991). In European countries, debates on the hijab are structured around religious freedom, gender equality, secularism, and security concerns. Since the 1970s, Muslim women migrating to Europe have struggled to maintain the hijab, considered a religious obligation, while local societies often perceived this practice as foreign and unusual. In Western contexts, the hijab has frequently been interpreted as a symbol of women’s oppression, a viewpoint that has fueled rejections and bans, particularly within feminist circles and certain political debates. Media representation has further contributed to the negative shaping of social perceptions (Ab Halim et al. 2022).

Research highlights diverse dimensions of the hijab. Hopkins and Greenwood (2013) demonstrated in the UK how the hijab shapes individuals’ social experiences through identity and visibility, while Alayan and Shehadeh (2021) found in Palestine that the hijab transcends its religious identity dimension to become a symbol of political resistance. Hammami’s (1990) studies during the Intifada emphasized the potential of the hijab to shift from an individual choice to a societal norm. Similarly, Hamdan (2007) revealed in France that women adopt the hijab as a means of expressing their identity. These studies collectively illustrate that the hijab functions as a dynamic symbol across different geographies and contexts, encompassing both individual belief and social significance.

In Türkiye, the hijab occupies a position at the intersection of individual, social, and political dimensions. Since the founding of the Republic, the female body has been central to the ideology of secular modernization. From the 1980s onwards, hijab debates have been framed through the dichotomy of the “modern, liberated republican woman” versus the “pious, veiled woman,” thereby encoding the hijab not merely as a religious practice but as a marker of social identity. During this period, women wearing the hijab faced bans in universities and public institutions, and the debates were centered on the female body (Gemici 2023). Restrictions on the hijab and other religious symbols in public spaces created tensions between individuals and the state, affecting women’s social and psychological well-being (Navaro-Yashin 2002).

In the 1990s, postmodern trends began to influence the emergence of veiling fashion (Adıgüzel 2023). Following the relaxation of bans in education and public sectors in the 2000s, forms of hijab expression diversified, and hijab fashion gained popularity (Sayan-Cengiz 2018). With the rise of social media, perceptions of the hijab have further evolved, resulting in significant shifts in body image and styles of veiling. Social media has transformed the practice of the hijab into a hybrid space that integrates personal belief, fashion, lifestyle, and digital performance.

The majority of women in Turkey wear the hijab (Uğur 2019). Both in Turkey and Europe, many women choose to wear the hijab despite opposition from the state, men, and even their families, a decision that requires significant resistance, sacrifice, and resilience. A 2015 Open Society Foundation study involving 122 hijab-wearing women in the United Kingdom revealed that family pressure was rarely a factor compelling women to wear the hijab; rather, pressure was more commonly directed at removing it (Albayrak 2023). Popular culture (e.g., the film Büşra) and field research indicate that the hijab is not merely an ideological symbol, but an element continuously re-signified through everyday practices at the intersection of individual subjectivity and spatial politics (Gökarıksel 2011).

However, various restrictions on hijab use persist in different countries, and discussions on the topic continue predominantly on social media platforms. Social media provides individuals with the opportunity to freely express their views regarding the hijab (Jakku 2018). This phenomenon is particularly relevant to the focus of our study, which is hijab removal. Social media campaigns on platforms such as X (formerly Twitter) and Instagram serve as prominent examples of hijab removal trends. While hashtags such as #HandsOffMyHijab respond to hijab bans, hashtags including #FreeFromHijab, #MyStealthyFreedom, and #NoHijabDay allow women to express themselves through their decision to remove the hijab (Reuters 2021; Syahrivar 2021). In Turkey, trends such as the #10yearchallenge, where women shared images of their past veiled selves after removing the hijab, have sparked public debate (Kalafat 2019). Furthermore, some women, dissatisfied with political practices, have begun to express themselves by removing their hijabs and announcing this decision on social media platforms, highlighting the significance of this issue (Ensonhaber 2025; Yıldız 2025).

In the literature, women who transform the hijab into a consumable and aestheticized form in digital showcases are often referred to as “hijabistas” or “veiled influencers” (Arab 2022; Baulch and Pramiyanti 2018; Karakavak and Özbölük 2023). Aygün (2022) emphasizes that hijab identities are reproduced within a cycle of supply and display on Instagram and operate according to the logic of the culture industry. As Yanıkoğlu (2014) emphasizes, in the Turkish context, the hijab is not merely a matter of personal attire, but rather a complex socio-political symbol situated at the intersection of women’s identity, agency, and representation. Despite its centrality in public and political discourse, women’s own voices and experiences often remain marginalized within these debates.

According to Küçük (2020), social media has become a tool for women in Turkey to express their religious identities, while Arab (2022) and Zaenuri et al. (2020) show that visual representation reinforces the “ideal Muslim woman” through a class-based, consumption-oriented aesthetic. The meaning of the hijab has also shifted across generations: Generation Z tends to view veiling as an aesthetic and individual expression, whereas Generation Y interprets it within collective belief and solidarity frameworks (Özensel 2023; Latiff and Alam 2013; Young et al. 2014).

Research on unveiling indicates that it is not merely a religious departure, but a complex psychosocial process shaped by social expectations, family dynamics, and digital culture (Syahrivar 2021; Izharuddin 2021; Horozcu 2023; Yalçi 2023). Horozcu particularly emphasizes its psychological dimensions, while Ataman and Sağırlı (2024) introduce the notion of the “burden of representation”.

Contextual meanings of the hijab also vary in Iran; “bad hijabi” practices operate as micro-resistance against state-imposed modesty laws (Bayat and Hodges 2024), whereas in Palestine, it functions as a symbol of national and religious identity (Alayan and Shehadeh 2021). In Canada, Muslim women digitally negotiate their identities and relationships with the hijab across different platforms (Mohammadi 2020).

Anonymous online platforms in Türkiye (e.g., yalnizyurumeyeceksin.com) illustrate how individual experiences of unveiling are transformed into collective narratives and social support (Okumuş 2022). Overall, unveiling cannot be reduced to secularization or religious detachment; rather, it represents a multi-layered process of identity reconstruction. While much scholarship examines the impact of social media on hijab fashion (Baulch and Pramiyanti 2018; Kavakci and Kraeplin 2017), critical gaps remain regarding how digital platforms shape the practices of unveiling.

1.2. Method

This section will present the research method, provide information about the participants, and explain the procedures of data collection and analysis.

1.2.1. Research Design and Participant Selection

This study utilizes a phenomenological approach within a qualitative methodology to examine the lived experiences of individuals who have abandoned the hijab. Phenomenology seeks to reveal the deeper meanings of lived experiences for individuals who have encountered the phenomenon. The study employs semi-structured in-depth interviews as the primary data collection method.

The study included 13 Turkish Muslim women who voluntarily decided to stop wearing the hijab. Announcements were shared on the researchers’ social media platforms to invite women meeting the criteria to participate voluntarily. The inclusion criteria focused on young adult women from Generation Z and Millennials (20–38 years old) who were active social media users and were either university students or graduates. Exclusion criteria involved women who had removed their hijab solely due to immediate external pressures and those who did not use social media. The participants’ ages ranged from 20 to 38 (M = 26), and all possessed a high level of education. We acknowledge that our sample, recruited through social media and consisting of educated, urban, middle-class women, limits the generalizability of our findings (see Appendix A, Table A1). This study does not represent the experiences of women from rural areas or lower socioeconomic backgrounds, who may face different pressures and maintain a different relationship with social media. This constitutes a significant limitation regarding class bias.

1.2.2. Researcher Positionality and Reflexivity

The researchers acknowledge their positionality as veiled Muslim women within the Turkish socio-cultural context. While we have not personally abandoned the hijab, our social circles include numerous friends and relatives who have undergone this transition, whether accompanied by significant class mobility and environmental change or not. Furthermore, we share a lived experience of social exclusion and the legal and social restrictions historically imposed on veiled women in Turkey. As active social media users ourselves, we are keenly aware of its transformative potential in shaping lifestyles and identities.

We recognize that this insider(emic) perspective inherently shapes the research process, potentially influencing participant rapport, the framing of interview questions, and the interpretation of data. To mitigate the risks of bias and ensure analytical rigor, we have engaged in continuous reflexivity throughout the research process. This involved maintaining a critical self-awareness during data collection and analysis, consciously bracketing our preconceptions, and seeking to represent the participants’ experiences in their own terms, thereby striving to balance empathy with scholarly objectivity.

1.2.3. Data Collection and Data Analysis

This study investigates the influence of social media on the increasing tendency among young women in Türkiye to abandon the hijab, analyzing their motivations through Bourdieu’s conceptual framework of cultural and social capital. Situated within Türkiye’s broader socio-cultural context, the research adopts a qualitative methodology based on semi-structured interviews to examine how digital platforms not only transform consumption habits but also shape religious and cultural expressions. Accordingly, in-depth interviews were conducted with 13 self-identified Muslim Turkish women who had voluntarily ceased wearing the hijab.

The study employed purposive sampling, targeting participants who could provide rich and relevant insights for the research questions. Specifically, a criterion-based purposive sampling approach was used, focusing on educated women who had removed their hijabs and were active social media users. A total of 13 participants were recruited through social media platforms and personal networks. While this criterion-based approach ensured the relevance of participants to the research focus, it also resulted in a sample predominantly composed of educated, middle-class women. No new themes emerged after the fourteenth interview, indicating that data saturation had been reached. This limitation suggests a potential class bias and underscores the importance of future studies engaging with a more socioeconomically diverse participant base to better capture the heterogeneity of experiences surrounding hijab removal in Türkiye. Future research should include women with rural backgrounds or lower education levels to test the universality of these findings. Interviews were conducted both face-to-face and online, depending on participants’ preferences and availability. With participants’ informed consent, all interviews were audio-recorded. The recordings were then transcribed verbatim and prepared for thematic analysis by the researchers.

The interviews, which lasted between 80 and 100 min on average, were conducted both in-person and via various social media platforms, consistent with the qualitative design of the study. All participants’ identities were kept confidential and anonymous during the data analysis process. Selected quotations from the interviews were included in the article to reflect participants’ perspectives in their own words. One notable challenge encountered during data collection was that a significant number of women who had decided to remove their hijabs declined to participate from the outset. Furthermore, it was observed that participants who agreed to be interviewed often displayed signs of emotional distress during the sessions, with many becoming tearful while recounting their experiences.

Qualitative research analysis involves the formation of codes and categories as well as the thorough exploration of themes. The information gathered and the interviewer’s observations of the participants’ conduct are described comprehensively in the interpretation. Systematizing and combining comparable expressions in the received data is how content analysis is carried out. Themes are identified by a certain category, and comparable data is coded. The data in this study are analyzed using the thematic analysis method (Creswell 2016). Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analysing, and presenting themes in data. It organises and describes your data set in detail (Braun and Clarke 2006). The texts were scanned by the thematic analysis method and were read several times by the researchers. Accordingly, the interviews which are all in Turkish language-were first transcribed and repeatedly read to ensure familiarity with the content. Initial codes were then generated from meaningful segments of the data, and similar codes were clustered to form coherent themes. These themes were reviewed against the dataset to ensure consistency and comprehensiveness. Finally, the themes were clearly defined, named, and reported with direct quotations from participants to illustrate the findings.

2. Results

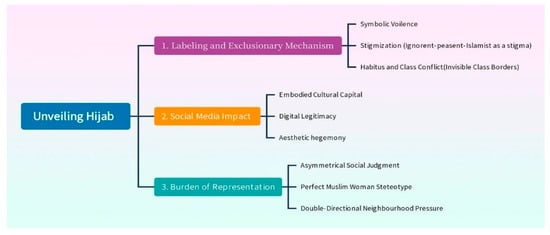

As a result of analyzing the interviews with the participants, certain themes emerged. The factors affecting the decision to abandon the hijab were grouped under three main themes: the influence of social media, labeling and exclusionary mechanisms, and the burden of representation. Following the coding process, various sub-themes were developed based on these main themes. Information on the themes is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Unveiling Hijab.

2.1. Labeling and Exclusionary Mechanisms: The Hijab as a Barrier to the Elite Habitus in Türkiye

The study observed that the lack of acceptance of the headscarf within Turkish society, particularly within certain circles, influenced participants’ decisions to abandon it. Participants also reported that wearing a hijab came with invisible pressures and various mechanisms of stigma and exclusion. This theme reflects stigmatization, labeling, and the hijab as indicators of symbolic violence, a type of internalized stigma that sustains cultural and class-based marginalization.

Analysis of the interview data revealed that these mechanisms operate in a self-reinforcing and reproducing manner. Pejorative labels such as yobaz (backward), cahil (ignorant), and köylü (peasant) not only trigger social exclusion but also transform the hijab into a class barrier—a symbolic boundary demarcating habitus. In turn, the internalization of these stigmas (i.e., symbolic violence) further legitimizes exclusion, creating an endless loop of marginalization.

2.1.1. Symbolic Violence: “I Felt That People Put Me in the Place of a Human Being: Internalized”

The labels and stigmas mentioned above influenced almost all participants to abandon their hijab; moreover, they caused some participants to internalize them. This situation aligns with the concept of symbolic violence which can be summarized as the oppressed person viewing themselves through the oppressor’s lens often unperceived by both the victim and the oppressor. (Mahmood 2005).

Hagar stated that she experienced both openness and concealment at the age of 18, recalling that she called her mother after unveiling, and said ‘I finally feel like people see me as human.’” This sentiment is echoed by Nalan, who explained that after unveiling, she began interacting with “more intelligent people,” and by Yusra, who admitted to not wanting to be examined by veiled doctors due to perceived egotism, and asserted that all veiled people were political Islamists. This labeling echoes the historical discourse during the post-modern coup period, which framed “the hijab as a political symbol”. Besides, the label of political Islamist seems quite the same as the discourse of “hijab is a political symbol” discourse back in the post-modern coup period. These statements indicate an internalization and acceptance of the stigmatized view. Collectively, these statements reflect the internalization of stigmatized views and the psychological impact of symbolic violence.

It is clear that the hijab is not merely a religious symbol but a field where cultural capital is contested. The interview excerpts clearly demonstrate that the hijab functions as a significant barrier to cultural capital in Turkish society. The hijab constitutes a significant cultural capital barrier in Turkish society, leading to humiliation, workplace mobbing, and severely restricted access to upper social classes. Viewed through Bourdieu’s concepts of cultural capital when evaluated through Bourdieu’s concepts of cultural capital (embodied, objectified, and institutionalized) and social capital, it becomes evident that veiled women face not only economic but also significant cultural and symbolic barriers that reproduce social inequalities. Hijabi individuals face not only economic but also deep cultural and symbolic barriers, which reproduce social inequalities. This provides a clear example of how acquired cultural capital can be devalued due to specific identity characteristics, restricting social mobility. In other words, hijabi women navigate a dual burden: exclusion from elite habitus and the internalization of a stigmatized identity, a process that perpetuates social immobility and underscores how secularist doxa sustains inequality.

The veiling of women represents one of the most visible markers of religious identity. However, such visible expressions may not always be welcomed in secular societies, where the most explicit embodiment of secularism is often inscribed on the female body (Tarlo 2010). In this regard, veiled women—particularly in public spaces—are frequently subjected to symbolic violence, which manifests in subtle yet pervasive forms of exclusion, stigmatization, and social pressure. For some women, this experience proves to be psychologically distressing, leading to feelings of humiliation and alienation (Uysal 2019). This study found that participants’ decisions to remove their hijab were significantly influenced by their desire to avoid social marginalization and the symbolic violence associated with veiling. For many, unveiling did not necessarily reflect a change in religious conviction but served as a strategic response. For many, unveiling was not necessarily indicative of a shift in religious conviction, but rather a strategic response to exclusionary pressures and stigmatizing discourses in secular public spaces. Sözeri’s (2022) study similarly shows that participants sought to integrate into modern lifestyles while maintaining their faith, a dynamic that reshaped their religiosity. In Sözeri’s (2022) study, participants’ desire to integrate into modern lifestyles while maintaining a connection to their faith emerges as a key dynamic in transforming their religiosity. This is reflected in their decisions to remove the hijab, which can be interpreted as an adaptation to a more secular environment. However, a critical question remains: Does symbolic violence and stigmatization truly end once women remove the hijab? The more critical question is whether symbolic violence and stigmatization truly cease once women remove their hijabs. This concern highlights the deeply entrenched nature of gender norms within society, which are far more rigid and pervasive than often assumed. The persistence of stereotypes suggests that visibility, conformity, or resistance—whether veiled or unveiled—does not necessarily shield women from normative judgment or social regulation.

2.1.2. Stigmas: “You Could Speak Flawlessly, Hold Degrees; However, When Veiled, You’re Instantly Becoming Ignorant”

The use of the veil has a dual and complex effect on both physical and social life (Bhatia et al. 2025). Participants’ statements reveal significant prejudice against veiled women in Turkiye (Yoldaş and Uysal 2023). The most frequently mentioned, most repeated, and striking stigmas in our interviews were ignorant (cahil), backward (yobaz), grandmother, and peasant (köylü). Expressions such as Syrian, looter, and Sümeyye were also used as stigmatizing labels were also noted. Another frequently repeated label was political Islamist. This label, rooted in the February 28 discourse that framed the hijab as a political symbol, persists today in the form of “Political Islamist” applied to women who wear the hijab. This expression, a continuation of the thesis that the hijab was a political symbol during the February 28 period, is still used in the form of “Political Islamist” as a label for the women wearing the hijab. It was observed that this pressure was a significant factor in the decisions of women who gave up their hijab.

Despite attaining education, hijabi women are often framed as uneducated. Aisha, a university graduate, noted: “You could speak flawlessly, hold degrees; however, when veiled, you are instantly ‘cahil.’” Another participant (Esra) emphasized this perception: “They see veiled women as ignorant, as if they are women who do not know anything, who are intellectually behind, who do not have much potential.” The belief that veiled women are ignorant thus appears to force hijabi women into a constant cycle of proving themselves “intellectually sufficient” and “educated.” Participant Handan stated: For example, there, like, a non-hijabi woman can exist with all her ignorance, okay? If I may put it this way, these are what we call dumb blondes. Nevertheless, for example, for you to exist as a veiled woman, you constantly have to say, ‘Oh, I am also this educated, this knowledgeable, this cultured.’ This is so tiring.”

The prejudice that “hijabi women are ignorant” is a long standing phenomenon in Türkiye. Sociologist Nilüfer Göle argues in her book, Modern Mahrem: that “Veiling is generally perceived through the lens of ‘ignorance bias’ and is often identified with the slavish obedience of women, because it is interpreted as a kind of attack on the current concepts of ‘liberation of the sexes’ and ‘universal progress’ that blur the oppositions between religion and modernity” (Göle 2019). Historically, veiled women in Türkiye have been deprived of educational rights, perpetuating the myth of their ignorance. This suggests that the real issue is not education but that, from Bourdieu’s perspective, hijabi women do not fit into the secular doxa in Türkiye.

This study’s data also show that the hijab is associated with rurality. For instance, Hagar reported that her teacher consistently called her an “Anatolian girl” instead of using her name, effectively erasing her individuality and to frame her as an outsider. Bourdieu’s concept of habitus clarifies this dynamic: urban elites construct secular lifestyles as doxa, rendering the hijab illegible in high-status fields (e.g., corporate jobs, elite universities). Participant Nalan explained that at Hacettepe University, one of Türkiye’s most prestigious institutions, veiled women are labeled as “backwards,” a view commonly held: “But in this business, they say that women who wear hijab are backwards, that they are outdated.” Well, even using such words is very funny currently. We are still in 2025, but here we are at school, at university. Another participant, Zahra, adds, “It seems to me that hijabi people are seen as backwards in this society.”

Another issue some participants noted was the association of veiling a hijab with being mature and unveiling with youth. Marwa noted, “…I looked older next to her. That is how I felt. With my current style of dress, I feel like I look younger and better.”

For many participants, the decision to unveil represented an escape from the reductive label of being a “political Islamist”—a stereotype that reduced their complex identities into a single, politicized narrative. As Hagar observed, “Veiling is also difficult because of political issues. The current generation has rigid ideas; there is no middle ground.” This polarization constrains veiled women to a single ideological category, regardless of their beliefs. This polarization forces veiled women into an ideological box regardless of their actual beliefs. Another participant explained: “When you unveil, the political Islamist label is lost. Your identity becomes more multidimensional; people try to get to know you. Your views, politics, education, and beliefs can all be different. However, when you are veiled, you are reduced to a single stereotype in people’s eyes.” The hijab functioned according to Esra “a disadvantage”—a visible marker of immediate political categorization. A visible marker inviting immediate political categorization.

The psychological toll of this stereotyping was clear in Esra’s experience of public harassment: “A man on the ferry judged me based on my clothes and humiliated me in front of everyone. That moment was a breaking point. I realized I was not the simple person he reduced me to be.” This incident illustrates how the political labeling of veiled women is not merely an abstract social issue but a daily reality that can manifest as hostility. For many, unveiling became a strategy for reclaiming their right to be seen as individuals rather than as political symbols. Here, it is possible to say these women internalized the discourse of “hijab is a political symbol, not a religious duty”. The reason why this study describes these unseen pressures as “symbolic violence”. Since these women began to view themselves as secular people see them.

Existing studies underscore that the hijab phenomenon in Turkiye is deeply embedded within broader political culture dynamics, reflecting tensions between secularism, religious expression, and state ideology (Mavi 2012). These narratives reveal a paradox: while the hijab has been central to political debates for decades, the women who wear it are often denied political agency. Therefore, the act of unveiling, emerges as both personal liberation and a response to commentary on the persistent politicization of women’s bodies in the public sphere (Secor 2002).

Amid the secularization process in Turkiye, religious symbols, especially the hijab, were often associated with “ignorance” and “backwardness” within modernization discourse. This has positioned the hijab not only as a sign of faith but also as a perceived marker of tradition. Secular discourse has further legitimized this representation, associating it with the figure of the “obedient woman.”

This discursive structure has historically linked women wearing hijab to religious identity; however, at the same time, lower socioeconomic status codes them as individuals lacking cultural and economic capital. The historical foundations of this perception are evident in various forms of popular culture. Turkish cinema, in particular, offers significant reflections of these representations. During the post-Republican period, hijabi women were frequently portrayed as maids, nannies, or lower-class figures, reproducing their culturally and economically marginalized position. Consequently, the hijab became a symbol of the “other,” excluded from the project of modernization (Şan and Serdar 2021).

Although visual and media representations have shifted in recent decades, social perceptions have remained largely unchanged. As participant narratives reveal, the headscarf continues to be associated with social class distinctions. For some individuals, the desire to feel aligned with a higher class underscores the persistent influence of historical representations and the secular modernization discourse. This dynamic aligns with Bourdieu’s (2014) concept of symbolic violence; wherein dominant groups reproduce social hierarchies by naturalizing the perception of hijabi women as inherently deficient in cultural capital. Participant testimonies further indicate that many internalized these symbolic labels, and this internalization functioned as a form of social pressure that shaped their decisions to abandon the headscarf.

2.1.3. Habitus and Class Conflict: “Even Süslümans Are Never Seen as Upper-Class”

The interviews revealed that even when women have access to resources, such as possessing advantages like higher education and economic capital, they are still not entirely accepted by the Turkish secular elite if they wear the hijab. The hijab is perceived as a barrier to accessing the upper class. This is reflected in Fatimah’s statement: “Today, even ‘süslüman’ women [a portmanteau of ‘süslü’ (fancy) and ‘Müslüman’ (Muslim), referring to hijabi women who adopt luxury fashion] are not truly accepted into upper-class spaces.” This finding resonates with Bourdieu’s (1984) assertion that cultural capital—embodied in dress, taste, and lifestyle—serves as a gatekeeping mechanism for class mobility. Regardless of its aesthetic appeal or economic alignment, the hijab remains fundamentally incompatible with the secular elite habitus.

A widely recognized newspaper headline—“Halk plajlara hücum edince vatandaş denize giremedi” (“When the public flooded the beaches, citizens could not swim”)— exemplifies secular elitism. In this context, “halk” (the public) and “vatandaş” (citizen) are strategically differentiated: the former denotes lower-class groups (often coded as religious or conservative), while the latter signifies the secular middle and upper class individuals entitled to exclusive spaces. This mirrors Bourdieu’s (1986) concept of distinction. An incident related by participant Esra involved a famous person at a luxurious beach abroad who, unaware of her past veiling, commented on a girl in a hijab swimsuit: “Are you here to swim or stay veiled? Decide—you cannot do both.” Esra expressed her discomfort: “I was mortified. I hope she is not Turkish. If she is, we have been disgraced… I did not know there were still people like him. I thought that way of thinking had disappeared—but it has not.” Her concern about disgrace indicates that bullying a hijabi woman is more socially accepted and normalized in Türkiye than abroad. Another anecdote from participant Aminah illustrates how the hijab contributes to class division: “In middle school, I was ashamed for wearing Kinetix shoes instead of Nike. I did not know these brands back then. This shame extended from the brand of my father’s car to my mother’s hijab both marked us as ‘outsiders.’” This account underscores how class distinctions are materially and symbolically inscribed, echoing Bourdieu’s (1984) analysis of objects as class markers. The hijab, like the brand of a car, becomes a visible determinant of class identity. The fact that a middle-school student internalized this stigma highlights the depth of symbolic violence, revealing how embodied religious identity operates as cultural capital within Türkiye’s secular habitus (Bourdieu 1984).

As Bourdieu and Wacquant (1992) note, “When habitus encounters a social world of which it is the product, it is like a fish in water: it does not feel the weight of the water, and it takes the world about itself for granted.” The stigma attached to the hijab is not always consciously recognized by those enforcing or internalizing it. However, those seeking acceptance in elite secular contexts profoundly experience its impact.

Participant Esra articulated prejudices against veiled women in the upper class: “When I see someone on Instagram who is very rich but veiled, I think it is fake—it cannot be real. They must be stealing or cheating. I definitely believe there is a class boundary. They do not accept me, and they do not believe me. Does this exist in our society? Yes, of course it does. How can you be conservative and live such a high society or elite lifestyle? How can you live so luxuriously?”

Hagar described the “sunroof” hijab style—a semi-veiled appearance—as a form of negotiation for class mobility: “With ‘sunroof’ styling, the ‘lower-class’ stigma faded— but only halfway.” This partial assimilation reflects what Bourdieu (1986) calls “reconversion strategies”, whereby marginalized groups modify their cultural capital to better align with the dominant field yet still inscribe the body as a site of class struggle.

Nalan noted that although her aunts were more secular, and her mother wore the hijab, her aunts consistently regarded her mother as belonging to a lower class. Aisha reinforced this observation: “People in the upper class do not find you judgmental or condescending when you unveil.” These accounts underscore that the hijab marks women as socially inferior, reinforcing class-based exclusion and inhibiting upward mobility, functioning as “negative social capital” (Bourdieu 1986).

In her study of Âlâ magazine, Sayan-Cengiz (2018) discusses status differentiation among veiled women based primarily on economic capital. This indicates a shift from the hijab as a religious symbol to a status marker reflecting both economic and cultural capital. Critiques of the hijab, through Bourdieu’s class theory, highlight the reproduction of social class, status, and cultural capital.

The workplace is another key dimension reinforcing habitus. Participants reported that veiled women are excluded from certain professions through unwritten rules. Some workplaces refuse to hire them altogether; others restrict them from public-facing roles, and many deny promotion opportunities. These discriminatory practices were frequently cited as reasons for unveiling.

Aisha described feeling ignored, humiliated, and subjected to prejudice in her professional environment. Esra noted the normalized nature of such discrimination: “It is the same in companies. There are still companies that do not hire veiled employees. It is not written anywhere, but they do not.” These narratives exemplify Bourdieu’s concept of institutionalized cultural capital, wherein secular norms become embedded in labor market structures, rendering religious identity incompatible with professional advancement in many elite or secular workplaces despite formal legal equality.

In addition to adjusting their habitus, some participants sought to transform their lifestyle and clothing to gain more acceptance in their new social environments. While some maintained their previous routines after unveiling, others began socializing in establishments where alcohol is served. Fatimah reported that she had consumed alcohol while wearing the hijab but began frequenting pubs more openly after unveiling. In contrast, Hagar criticized veiled women who consumed alcohol in such venues, expressing discomfort and framing it as an issue of moral and spatial appropriateness: “Just as I do not enter a mosque with my head unveiled, I should not enter a club with my hijab on.” This contrast reveals a deeper negotiation of moral boundaries and social belonging among participants. While Hagar’s stance reflects an effort to preserve symbolic consistency between faith and public behavior, Fatimah’s experience illustrates a pursuit of social and cultural mobility. Unveiling is not merely a change in appearance but a transition toward accessing different social spaces and forms of capital—what is colloquially described in Türkiye as “changing one’s neighborhood.”

Significant differences exist between lower socioeconomic strata and elites regarding religious beliefs and practices (Akşit et al. 2012). Recent qualitative research indicates that the decision to remove the hijab is not solely rooted in shifts in religious belief but is also influenced by a desire to adopt a more secular lifestyle and participate more actively in public life. Başak’s (2022) study reveals that a primary motivation for unveiling is the aspiration to join modern society and escape the social pressure associated with the hijab. This aligns with our findings, where participants sought to escape the symbolic violence of being labeled “backward” and to gain access to elite social and professional circles.

2.2. Social Media Impact

Social media is a powerful tool that shapes perceptions, lifestyles, and identities. It offers a space where users can observe diverse lifestyles, compare themselves with others, and internalize new social norms. This section examines how social media acts as a catalyst for abandoning the hijab, focusing on its role in normalizing unveiling, facilitating social comparison, and enabling the performance of alternative identities.

2.2.1. Embodied Cultural Capital: “There Is a Social Media Network That Judges Everything”

With the rise of digitalization, the self has increasingly become a site of exhibition and display (Schwarz 2021). On social media platforms, individuals present themselves—and everything they embody—as commodified products. According to Bourdieu (1986), “embodied cultural capital” refers to the symbolic value acquired through conscious or unconscious investment in the body. Features such as weight, posture, clothing, cosmetic procedures, and makeup represent cultural markers reflected on the body, which also contribute to social positioning.

Today, platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, and X have rendered bodily capital visible, measurable, and subject to public evaluation. These digital environments cultivate distict standards of wealth and beauty. Displaying branded accessories, vacationing abroad, dining in upscale restaurants, practicing yoga or Pilates, and undergoing cosmetic procedures have become visual indicators of a luxurious lifestyle. While these practices require a certain level of economic capital, displaying them as embodied cultural capital is equally important.

In the capitalist system, the notions of happiness and freedom are increasingly equated with levels of consumption. Social media reinforces the arguments of a secular lifestyle, promoting visibility, display, and performance. This secular, consumption-driven culture transforms individuals into profile-oriented subjects, where self-worth is measured by digital approval and aesthetic presentation. According to Han (2017, 2020), the individual is no longer a subject in the traditional sense but rather becomes an object—one that performs prescribed behaviors dictated by the logic of digital platforms. In this framework, agency gives way to algorithmic conformity, and self-expression is supplanted by strategic self-exposure.

The more successful individuals showcase such elements, the more likely they are to attract followers—and, in some cases, even job opportunities. Participants in this study were acutely aware of this imposed model of digital display and offered critical reflections on its influence. Hagar, one of the participants, critically reflected on the judgmental nature of social media, stating: “There is a social media network that judges everything—people’s behavior, the way they dress, talk, look—literally everything.” She also shared that she felt unattractive while wearing the hijab: “When they took pictures, I didn’t even want to look at them a second time. Because I wasn’t happy seeing myself that way. I wasn’t happy being like that, and during that time I was veiled.”

Hagar’s experience can be interpreted as a reflection of her perceived incompatibility with the dominant forms of embodied cultural capital. Her sense of unattractiveness was not necessarily a result of the hijab itself, but rather of its dissonance with prevailing aesthetic norms promoted through social media. Within these digital spaces, visibility and recognition are closely linked to conformity with specific bodily and beauty standards.

This tension is further illustrated by a viral quote from a well-known Turkish influencer, Nihal Candan, who tragically passed away at age 30 after battling anorexia nervosa. This condition reportedly stemmed from the pressure to achieve an ideal body image. As she once stated, “people like me more when I post photos of luxury items, but not when I share images from an organic market” (Çağlayan 2024). Her comment encapsulates the way aesthetic performance is rewarded within digital platforms, while deviations from these standards are often overlooked or dismissed.

These dynamics suggests that social media audiences tend to favor visual content associated with higher socioeconomic status. Individuals who do not conform to these aesthetic and materialistic standards often experience algorithmic invisibility negatively affecting self-perception and sense of value. Nalan, another participant, recalled a trend on X (formerly Twitter) in which women posted about removing their hijab and equated it with liberation: “It was disgusting—people spewing hatred, saying it’s backward, it’s outdated. There was a trend on Twitter, you might have seen it. ‘I took it off (Hijab), I’m free now.’”

The proliferation of internet platforms has significantly increased the visibility of hijab fashion, transforming the headscarf from a solely religious symbol into a dynamic site of aesthetic, cultural, and commercial negotiation. Online hijab fashion retailers now reach broader and more diverse audiences, facilitating the rearticulation of veiling within contemporary consumer culture and mediating its public re-coding in ways that both challenge and reinforce existing norms (Tarlo 2010). In this respect, social media significantly influences both the transformation of hijab styles and the decision to unveil.

As a result of the analysis, all participants reported using social media actively, with some describing near-constant exposure, referring to their interaction with digital platforms as “24/7.” Such intensive engagement contributes to the internalization of a particular aesthetic regime and shapes individuals’ perceptions of self, beauty, and belonging through a continuously reinforced repertoire of cultural capital (Verwiebe and Hagemann 2024). Digital platforms can also influence the dissemination of hijab fashion and the styles of head coverings. For instance, Muslim women born in the United States are concerned with issues such as what to wear, how to style their hijab, how to manage transitional periods, and how the hijab may affect their professional, familial, and social relationships. Following the negative stereotypes that emerged after September 11, aligning their beliefs with their appearance has become more challenging. Converts living geographically distant from Islamic societies may overcome isolation and seek support through online blogs, videos, shopping websites, and forums, while also following developments in the Islamic fashion industry (Akou 2015).In her qualitative study, Sözeri (2022) observed that the process of modernization exerts a notable influence on religious beliefs. Factors such as the promotion of individualization through modernization and the increased accessibility of religious knowledge via digital platforms were found to play a significant role in shaping participants’ religious orientations. The recurring association between unveiling and personal freedom, particularly within digital discourse, reveals how the hijab is sometimes framed as a symbol of oppression among younger users. This perception may reflect a broader tension between traditional religious practices and the embodied forms of cultural capital celebrated in digital environments.

2.2.2. Digital Legitimacy: “I Got Good Job Offers from LinkedIn After I Unveiled Hijab”

Drawing on Goffman’s (2009) dramaturgical metaphor of the theatrical stage, individuals on social media present curated versions of their lives to a digital audience, resembling performers in a public exhibition. Just as everyday social interaction is shaped by implicit norms and expectations, digital platforms likewise impose a range of performative roles and aesthetic conventions—roles that continually shift following prevailing cultural and technological trends.

In Goffman’s theory of self-presentation, the concepts of performance, showcase, and setting are key. When translated into the context of social media, the showcase can be understood as the platform itself—Instagram, TikTok, or X—where visibility and display are fundamental. Performance corresponds to users’ activities including livestreaming, posting curated images, and sharing updates. The setting encompasses visually coded elements such as fashionable clothing, branded items, and popular locations that reflect prevailing digital aesthetics.

Importantly, the criteria for legitimacy and recognition on these platforms often prioritize external appearance over personal or intellectual qualifications. Fatimah, reflecting on her experience while wearing the hijab, articulated this tension as follows: “After I removed the hijab and I created a LinkedIn profile, I got job offers from places I never expected. I received good job offers.”

Fatima’s statement reveals how visibility is a legitimizing force in digital media. The job offers she receives when she makes herself visible, possibly through her profile photo, choice of clothing, or aesthetic appearance, show that the door to digital legitimacy is predominantly related to a secular appearance. Accordingly, the social codes associated with “hijabi” and “non-hijabi” women are differently recognized and validated within social media.

The prominence of the performing subject is related to how actively she utilizes the showcase, and which sets she includes. As the performing subject realizes these arguments due to the demand, her followers increase. Over time, the actions and choices of such figures come to be perceived as legitimate or authoritative, positioning them as reference points within their respective fields. These figures, in turn, function as models for others by signaling which practices are socially acceptable or desirable.

The dynamic is especially evident on visual platforms like Instagram, wherethe experiences of famous figures who remove the hijab serve as influential examples for those contemplating a similar decision.

As Nalan explains: “You see people who take off their hijabs, and when you see people who do, you realize that they have also gone through this process, so you can guess how it will continue… If you are twenty percent affected by a person in normal life, I think it is eighty percent on social media.” Nalan describes the internal conflict experienced in removing the hijab and highlights the amplified influence of social media in this decision-making stage. The visibility of other women who have removed their hijabs is a form of validation and normalizes the experience.

Echoing this observation, Handan reflects on a broader shift, stating that “this thing that we can call the coming out of fury has increased much more with social media,” suggesting that unveiling has become a collective and more visible act within the digital space. Social media provides observational cues and acts as a space for experimentation and soft disclosure. Duha further articulates this process, stating: “Instead of saying ‘I am thinking of something like this’, it is easier to post a story (with her hijab off). I liked the responses of those who responded positively to the story on Instagram.” These positive reactions serve as social reinforcement, easing the emotional burden of the decision. Finally, Mariam illustrates how unveiling reshapes digital presence: “When I was wearing a hijab, I did not post much on Instagram or Facebook, but now, if I do not post one day, I post the next day.” Taken together, these narratives reveal how social media operates as a backdrop and an active, legitimizing force in unveiling. Within Bourdieu’s framework, these comments illustrate how social media redistributes cultural and social capital while at the same time reinforcing it by privileging secular self-presentation.

It is evident that some participants learned about the processes they might encounter after removing the hijab through influencers. In this sense, influencers facilitated the decision-making process by guiding participants through this difficult decision. Additionally, several participants started to use social media more after unveiling the hijab. This situation also shows that social media is used as a legitimization tool.

Existing scholarship supports these observations. Studies have shown that social media influenced the decision to remove the hijab through lynch culture, desire to be liked, and influencer effects (Horozcu 2023; Karakavak and Özbölük 2023). Between 2002 and 2022, a total of 303 articles retrieved from the Scopus database were examined through bibliometric analysis. The major research on the headscarf primarily focused on the internet and social media platforms (Saimassayeva et al. 2025). Social media plays a significant role in the decision to remove the hijab and in reshaping its meaning and practice. In Saraç’s (2019) qualitative study, for instance, participants reported that the clothing styles and behaviors of veiled women on social media—which are perceived as incongruent with the traditional values associated with the hijab—have a meaningful influence on other hijabi women.

2.2.3. Aesthetic Hegemony: “I Have Trouble Finding Hijab Versions of the Clothes I Like on Pinterest”

Social media has imposed certain body molds called the “Barbie doll effect”, which have been normalized as dominant beauty criteria. For this reason, it is known that plastic surgeries have become increasingly common, especially among phenomena and influencers, and bodily fitness aligned with and conforming to certain beauty patterns has become a prerequisite for visibility on social media.

Moreover, it is seen that there are certain standards on platforms such as Instagram. This situation shows that aesthetic hegemony continues on social media. The use of social media increases the likelihood of women comparing their appearance with that of influencers and famous models. This comparison leads women to adapt their bodies to aesthetic standards. This conformity is enacted through practices such as investing significant time in taking, editing, and selecting photos to present an idealized self (Ma 2023).

Zainab’s remark that “I want to dress in these colors, and when I search for them on Pinterest, I find it very difficult to find their hijab versions. Because it is more for non-hijabi people. There are more options for them. There are more options for open clothes on social media. There are no hijab alternatives.” If we analyse this dialogue, although the participant is an active content producer on social media, her complaint about the lack of aesthetic representations for headscarved women, when analyzed through Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital, reveals that dominant aesthetic norms in digital spaces are constructed to favor secular and unveiled individuals.

In this study, some of the participants stated that they were influenced by Instagram influencers. Although some of them stated that social media was not effective in their decision to remove the hijab, they nonetheless expressed a desire to buy exactly that model and colors of the clothing they saw on the influencers. This contradiction that individuals may be under the influence of social media without realizing it. The fact that some of the participants stated that they did not like their appearance while wearing hijab suggests that their perception of beauty is closely alighted with secular aesthetic norms.

Marwa recounts that before unveiling, she felt the hijab did not suit her appearance “Before I unveiled the hijab, I hated myself and my body… Maybe I wouldn’t have worn it if there were alternative clothes. I was short, it didn’t suit me at all, I looked like a labut.”. She explains that only after removing it did she experience increased self-respect and greater attention to self-care. Similarly, Fatimah reports that unveiling enabled her to engage in beauty practices and sports as part of investing in her self-image, “When I took off the hijab, I started spending time on myself, going to the beauty parlor, and taking care of myself. I do sports.”

The majority of the participants find themselves ugly while veiled. Duha stated that the hijab made her feel “ugly and insecure,” and Aisha stated that she “looked like a grandmother”. These descriptions suggest that veiling has become symbolically associated with unattractiveness. In research conducted, studies have also revealed that the use of social media commodifies everything, including hijab, and that influencers affect the perception of hijab (Aygün 2022; Küçük 2020; Özensel 2023).

As participants explicitly stated, the primary reason for unveiling was the desire to feel beautiful. As Nalan noted, “If 10 people make such a decision, 8 do so for purely visual reasons, to feel more beautiful or happier at work.” The female body is among the areas where aesthetic hegemony is imposed most intensely. In addition, it is both easier and more profitable to shape perception with the female body due to “beauty anxiety”. In social media, women are exposed to both the search for likes and the pressure to shape their “bodily capital” according to these norms. The fact that the participants feel ugly is because the current perception of beauty is not aligned with the hijab. This profile of women with excessive make-up, aesthetics, and constantly struggling with their skin is a difficult and expensive way of beautification, not only for hijab wearers but also for secular women. Hagar observed that individuals who do not conform to conventional beauty standards—such as having a small hazelnut-shaped nose, straight teeth, or slanted eyes—are often perceived as less beautiful. This perception, reinforced by societal norms, is further intensified by social media, which has reshaped our understanding of beauty through a 180-degree shift in perception.

Social media plays a significant role in shaping beauty-related behaviors, including increased interest in plastic surgery and other cosmetic procedures. Research indicates that the earlier young women are exposed to appearance-focused content on social media, the more likely they are to internalize idealized beauty standards, experience body dissatisfaction, and report heightened appearance-related anxiety (Ma 2023). The influence of social media has even been linked to decisions to undergo surgical interventions (Seekis and Barker 2022). Comparing oneself to others on social media can lead to an identity crisis as well (Avci et al. 2024). A meta-review by Mwangi and Buvár (2024), covering studies from January 2015 to May 2023, confirmed the significant impact of social media on perceptions of beauty and the body. While some counter-discourses exist, the prevailing beauty ideal still tends to align with Western aesthetic standards. Similarly, Özçelik (2016) argues that social media undermines the traditional notions of modesty and privacy associated with the hijab. This shift is further reinforced by the aesthetic norms and visual culture promoted on social media.

Bourdieu (1984) emphasizes that clothing style is a bodily expression that reveals the deep dispositions of habitus. Zainab’s decision to alter her clothing choices to skateboard, or her difficulty finding modest fashion alternatives that align with current social media trends, illustrates how dress and bodily aesthetics reflect the relationship between social norms and cultural capital. As one ascends the social hierarchy, bodily refinement, beauty, and the ability to maintain aesthetic distance become increasingly important to mark distinction.

Mahmud and Swami (2010) investigated the impact of wearing a hijab on men’s perceptions of women. The study involved 57 non-Muslim and 41 Muslim male participants, who were presented with photographs of women, half wearing a hijab and half unveiled, and asked to evaluate them in terms of attractiveness and intelligence. The findings indicated that veiled women were rated more negatively than unveiled women on both attractiveness and intelligence. While participants’ religious affiliation did not generally have a significant effect on attractiveness ratings, non-Muslim men rated unveiled women higher than veiled women. Regarding intelligence ratings, non-Muslim men assigned higher scores than Muslim men across both conditions. Moreover, the scores given by Muslim men to veiled women were positively correlated with their self-reported religiosity. These results suggest that, even among men, there exists a perception that unveiled women are more attractive.

Although the decision to remove the hijab is shaped by various identity-related factors (Izharuddin 2021; Yalçi 2023), the influence of social media, particularly in reinforcing beauty ideals that align with Western cultural codes, is undeniable. These shifting beauty norms are reflected not only in general fashion choices but also specifically in modest dress practices. This influence appears to be especially pronounced during adolescence and early adulthood. For women, the consequences are both psychological and social: removing the hijab may enhance one’s visibility and followership in digital spaces, which, in turn, may offer a greater sense of validation. From the perspective of embodied capital, social media offers a relatively accessible pathway for individuals to align themselves with higher-status aesthetic standards.

As a result, all the analyses of this study revealed that social media had a significant influence on the participants. The ability to express themselves freely, display their physical beauty, and receive social validation through likes and comments were key factors that motivated their decision to remove the hijab. However, the extent of social media’s influence requires further examination. According to prior studies, individuals with lower self-esteem, those prone to social comparison, and those undergoing identity-sensitive developmental stages, such as adolescence or early adulthood, are more susceptible to social media influence (Nesi and Prinstein 2015; Vogel et al. 2014). In this context, the participants’ youth amplifies their responsiveness to online visibility and validation dynamics.

2.3. Burden of Representation: “You Are Not Just Yourself; You Represent All Veiled Women”

Interview data reveal that the individual behaviors of veiled women are attributed to all Muslim women or directly to Islam, and therefore, they carry a heavy “burden of representation.” This burden has been conceptualized as a psychological pressure stemming from the expectation to represent a Muslim-conservative identity that women involuntarily assume due to their hijab (Ataman and Sağırlı 2024). Participants emphasize that this burden requires a constant effort to “prove themselves,” and that this situation restricts their free expression of identity.

Participants draw attention to gender inequality in religious representation and the individual burden it creates. Fatimah clearly expressed her discomfort with the burden of representing the Muslim identity solely through women stating, “If Islam is an equal religion, a man should carry its burden just as I carry it.” The fact that men do not have a similar visible religious identity has been seen as the main reason why women are subject to more discrimination and mobbing in the public sphere. Esra also expressed her desire to be free from this burden of representation by saying, “I don’t want to represent anything. No one should understand anything when they look at me.” Yusra stated that she decided to give up her hijab because she felt she could not “carry this burden properly” and that this brought responsibility. The participant conveyed this inner conflict with the words, “When I took it off, I first felt like God was upset with me, then I felt like God got rid of me because I could not carry it properly.”

It has been observed that many of the women who are unveiled feel that their responsibility to represent religion with the hijab has become a burden, along with the issues mentioned above. Fatimah, who has spent at least half of her life abroad, stated that she conducted a study showing that 80% of individuals who are subjected to racism abroad are women who wear hijab. In addition, she stated that if Islam is to be represented, it is not fair for this responsibility to be only on women and that her husband should also shoulder this burden.

As a result, this burden of representation has created constant pressure on the personal choices and lifestyles of veiled women, preventing them from freely expressing their identities. This pressure compels them to conform to a particular universe of meaning and turn their public visibility into an object of “symbolic consumption” (Yalçi 2023).

2.3.1. Asymmetrical Social Judgment: “They Criticize Me When I Wear a Hijab and Ride a Bike with My Child, but Suddenly I Become a Caring Mother When I Unveil”

Our research reveals the existence of distinct social norms for women who wear the hijab and those who do not in contemporary Turkish society. While women with hijabs are strongly expected to conform to specific behavioral patterns, the same behaviors can be interpreted differently and even appreciated in unveiled women. This situation emerges in the different reactions that participants who left their hijab received during the same actions, both while wearing the hijab and after removing it. This dual structure leads to the assumption that women being judged solely on their clothing choices, regardless of their personal preferences.

Some of the most striking examples of this differential evaluation involve the same individuals engaging in the same actions while veiled and unveiled: Elmas reported that when she showed interest in children selling tissues on the street while veiled, she was perceived as strange; however, when she did the same after removing her hijab, the behavior was praised as a ‘virtuous’ act. Marwa stated that, during the time she wore a hijab, she received disturbing reactions from her surroundings while playing football and riding her bike with her son. However, after she took it off, she was instead appreciated for being a caring mother. This situation is a concrete example of asymmetric judgment in society. Similarly, participants (Aminah, Handan) stated that when they voiced support for the Palestinian issue while wearing the hijab, their ideas were not taken into consideration; however, once unveiled, they were not only taken seriously but also appreciated.