1. Introduction

If the religious landscape of Korea were imagined as a series of concentric circles, Musok (굿 gut) would occupy the innermost core, Confucianism and Buddhism would form the second layer, and Christianity and other foreign religions would lie at the outer periphery. Scholars have pointed out that shamanism is Korea’s only indigenous folk religion. Although it has historically absorbed Confucian and Daoist elements, its lack of a doctrinal system distinguishes it from institutional religions, producing regional differences between northern possession rituals (mansin-type) and southern hereditary rituals (sesŭp-mu-type) (

Sarfati 2021). Since the enactment of the Cultural Property Protection Law in 1962, most shamanic rituals have been incorporated into Korea’s list of Intangible Cultural Properties. This heritage-driven revival, supported by state subsidies, substantially revitalized shamanism but also generated two major transformations. First, tradition has often been preserved only formally, while its religious and mystical aspects have been diluted (

H. Kim 2013). Second, emphasis has shifted toward artistic, performative, and public-value dimensions (

Shinzato 2022). Some performers even describe gut as “not a sad event but a joyful festival” (

Tribune of Chonnam National University 2025). Thus, while heritage regimes have enhanced the visibility of tradition, they have also led to formalization and even fossilization. This delicate balance reveals how the “newly reborn shamanism” has become inseparable from institutional frameworks.

At the same time, institutional intervention has stimulated a surge of scholarship devoted to the safeguarding of shamanic customs and rituals. Anthropologists and scholars of religion during the 1980s–1990s focused on the social significance and spirituality of shamanic doctrines, viewing intuitive practice as a window into Korean cosmology, gender roles, and even political resistance (

K. O. Kim 2020). Since the 2000s, research has increasingly examined shamanism’s transformation in contemporary contexts. Sarfati explored the relationship between the shamanic subject and the receptive subject, as well as the commodification of shamanism within urban fortune-telling industries (

Sarfati 2013).

C. Kim (

[2003] 2018) challenged the simplistic labeling of shamanism as “popular culture” or “a women’s religion,” arguing that the “ordinary world” and the “shamanic world” are logically irreconcilable: the utterances of deities address misfortunes that cannot be resolved in the ordinary realm, revealing the paradoxical necessity—and social marginalization—of shamans. Similarly, Lee whose approach aligns closely with the present study, used a phenomenological method to reclassify shamanic rituals (chaesu-gut) (

Lee 1981), symbolic systems, and divine categories, correcting the superstition discourse and positioning shamanism as a cultural religion rather than a purely mystical one.

This situation gives rise to a particularly revealing phenomenon: the analytical dimensions of institution and ritual have tended to be absent, and the core status of ritual and doctrine has been partially displaced. Much of the existing scholarship approaches Korean shamanism from an external vantage point, observing its entanglements with culture, modernity, and social function, while the most fundamental ritual semiotic structures and their internal configurations of power have not received sufficient attention. If the symbolic elements of shamanic rituals are disassembled and recomposed, it becomes evident that the coupling logic between ritual signifiers and symbolic power is closely conditioned by institutional contexts. Although previous studies have illuminated the trajectories of shamanism’s transformation in modern society from multiple perspectives, they have largely treated “ritual” as a holistic analytical unit when interpreting symbolic meaning. Comparative structural analyses that differentiate among distinct ritual segments, heterogeneous signifiers, and their corresponding power configurations remain scarce. In particular, under conditions of institutionalization, how symbols are selected, reordered, and reassigned interpretive authority still lacks an operational analytical framework. It is precisely this problem—how ritual signifiers are filtered, reconfigured, and endowed with power interpretations within institutional structures—that the present study seeks to address.

If one aims to investigate shamanic ritual symbols in institutionalized contexts while relying solely on holistic ethnographic narration or symbolic interpretation, it becomes difficult to distinguish whether observed changes originate from internal ritual-structural differences or from external institutional interventions. Shamanic ritual is not a homogeneous whole; rather, it is composed of action segments, symbolic units, and participating actors with clearly differentiated functions and symbolic orientations. Different subsystems within ritual already exhibit structural variation in both power distribution and signifier-production logic. By decomposing ritual into event-level analytical units, institutional effects that were previously obscured can be rendered visible, and power relations can be subjected to comparative analysis across ritual types and institutional settings. On this basis, the present study adopts event-level coding as the minimal analytical unit, transforming identifiable ritual actions, symbols, and participants into a traceable data structure. Correspondingly, semi-quantitative power scoring and nonparametric statistics are not intended to replace symbolic interpretation, but rather to test whether observed differences demonstrate structural stability, thereby avoiding analyses that remain confined to descriptive judgments at the single-case level. By retaining multimodal contextual depth and ethnographic granularity while introducing a comparable analytical scale, this study proposes a framework that is both interpretable and testable for examining how institutional intervention reshapes ritual symbols and interpretive authority.

The author observes that two representative forms of Korean shamanic ritual—Ssitgim-gut

1 (씻김굿) and Byeolsin-gut

2 (별신굿)—constitute two poles of Korean shamanism’s core animistic ontology: doctrines of soul purification and soul festivity, respectively. In line with broader scholarly trends, Korean-language studies on Ssitgim-gut and Byeolsin-gut—based on a synthesis of articles indexed in the KCI journal database and theses archived in RISS—have been largely focused on (1) Institutionalization and stage transformation under the framework of Intangible Cultural Heritage, addressing ritual change and modern transmission; (2) literary and symbolic analyses of Ssitgim-gut texts, including mythology and trauma; (3) connections between folklore and philosophy, emphasizing a life view of “embracing death through festivity”; (4) regional and musical culture, particularly shared musical genealogies between Byeolsin-gut and Jindo Ssitgim-gut; and (5) heritage documentation and transmission, including regional histories of “festive funerary rites” and shaman–Buddhist syncretism. These studies similarly concentrate on institutionalization, aestheticization, textual symbolism, and interdisciplinary integration.

Positioning both rituals within a single analytical framework, this study examines how signifiers are selected and recomposed under different institutional conditions, and how differentiated power distributions are generated within ritual practice. Drawing on Charles S. Peirce’s semiotic principle of iconicity, which refers to the production of meaning through perceptual similarity or structural homology rather than through arbitrary convention, the study adapts iconicity to the context of ritual analysis. In this framework, iconic signifiers are understood as those that generate meaning directly through bodily movement, rhythm, spatial proximity, and repetitive action, without reliance on linguistic explanation, institutional texts, or external annotation. Accordingly, the term signifier in this study refers to the smallest symbolic unit that can be identified, recorded, and repeatedly invoked across media within a concrete ritual event.

Through systematic coding, the study constructs an analytical matrix encompassing signifier distribution, subsystem function, actor-based power scores, and institutionalization indicators. Nonparametric statistical tests and robustness checks are then employed to verify observed structural differences. The results demonstrate, first, that at the level of internal ritual structure, purification segments exhibit significantly higher concentrations of symbolic power than performance segments, with shamans occupying a stable position of dominance in signifier production governed by iconicity (H1). Second, along the axis of institutionalization, as scripting, narration, and archival regulation intensify, ritual signifiers shift from embodied iconic forms toward display-oriented and recombinable textual units, and interpretive authority correspondingly moves from a shaman-centered monopolar structure toward a institution–community collaborative configuration (H2). Finally, from a historical and policy perspective, Byeolsin-gut—by virtue of its festive, outward-facing, and display-compatible structure—has formed a high degree of alignment with South Korea’s heritage governance and cultural policies since the 1960s, thereby accruing institutional advantages through the process of institutionalization. By contrast, the funerary and purificatory character of Ssitgim-gut sustains a higher density of iconicity and a stronger religious core, while exhibiting more limited visibility and adaptability within institutional frameworks (H3). Taken together, these findings constitute the DSRR model (Distribution of Signifiers—Redistribution of Ritual Power), which provides a testable explanatory pathway for understanding the structural tensions among ritual practice, institutional intervention, and symbolic power.

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Description

To ensure that the research questions are empirically testable, this study conducts an event-level organization and analysis of traceable and verifiable ritual records, drawing exclusively on publicly available materials in South Korea. Data sources include doctoral dissertations, research reports, and

Supplementary Materials indexed in the Korea Citation Index (KCI) and the Research Information Sharing Service (RISS).

The master dataset (s1) consists primarily of three categories of materials: (1) audiovisual recordings, (2) interviews and fieldwork notes, and (3) archival and textual documents.

3 A clarification regarding potential bias is necessary. This study analyzes only those shamanic rituals that have already been documented, archived, and rendered traceable within Korean academic or institutional contexts. Spirit-possession rituals conducted in private domestic settings have not been included. As a result, the dataset inevitably carries a degree of institutional visibility bias: rituals that are filmed and archived tend to be closer to cultural centers, festivals, or Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) frameworks, and thus do not fully represent the entire spectrum of Korean shamanic practice. That said, this limitation is consistent with the study’s research objective. Because the focus lies specifically on the mechanisms of interaction between institutional structures and ritual practice, the analysis deliberately targets rituals that are, by definition, visible to institutions.

Further clarification is required regarding the internal diversity of Korean shamanic practice. Broadly speaking, two incommensurable ritual types coexist. The first centers on hereditary shamans (sesŭp-mu,세습무), whose practices are embedded within local village communities and characterized by repetition, public visibility, and collective participation. The second revolves around spirit-possession shamans (kangsin-mu, 강신무; often referred to as mansin), whose rituals rely heavily on individual possession experiences and are typically conducted in private consultation settings. In the latter case, symbolic power derives primarily from personal efficacy and charismatic authority, resulting in a highly centralized power structure that lacks the conditions necessary for redistribution across family, community, and institutional actors.

By contrast, the hereditary and community-based rituals analyzed in this study operate precisely within contexts of multi-actor coordination, segmentable ritual structure, and institutional intervention, where symbolic power can be reconfigured and translated. Accordingly, the core concern of the proposed model lies in how institutionalization—through scripting, textualization, and visual regulation—reshapes the production of ritual signifiers and the allocation of interpretive authority within ritual. For this reason, privatized, possession-centered mansin rituals, which lack stable event structures and comparable power-distribution dimensions, are not analytically suitable for the operationalization of indicators such as ΔP_S and are therefore excluded by design.

Romanization note. To ensure terminological consistency and reader accessibility, this study adopts the Revised Romanization (RR) system commonly used in Korean cultural and academic contexts. For ritual terms that have already gained stable usage in international scholarship—such as Ssitgim-gut and Byeolsin-gut—established spellings are retained.

2.2. Coding Scheme

Based on the data described in the previous section, this study constructs a reviewable master dataset (s1) in accordance with the evidence-tier framework. The event serves as the minimum unit of analysis, and each event is explicitly linked to its source document, page or chapter reference, and—where applicable—precise timecodes.

Data sources and evidentiary status are classified according to a three-tier evidence system (see

Table 1).

The core coding rules are as follows.

- (1)

Each continuous source is segmented into multiple events, with event duration restricted to 5–90 s.

- (2)

Each event must contain at least one identifiable Canonical_Signifier, and the configuration of participants must remain broadly stable within the event.

- (3)

Evidence tiering determines quantifiability.

An automatic downgrading rule is applied: if a segment contains descriptive accounts of ritual actions but cannot be matched to a specific timecode, it is automatically classified as Tier B and used only for qualitative reference. This rule prevents non-traceable fragments from being encoded as events.

The coding and variable system follows a three-layer structure: the signifier–subsystem–power relation.

- (1)

Signifiers

The Canonical_Signifier refers to a unified label applied to ritual vocabulary, bodily actions, and material objects. During coding, the original Korean term is retained, accompanied by Chinese and English explanations, in order to avoid semantic flattening through translation. A single event may contain multiple signifiers, which are separated by delimiters and entered as distinct records in the master table.

This classification directly operationalizes the S-axis (symbolic purification differentiation) and the I-axis (institutional textualization) in the proposed model, allowing the data to distinguish between religious mechanisms grounded in embodied experience and those regulated through textual or institutional discipline.

- (2)

Subsystems

Events are assigned to ritual subsystems according to their functional role within the overall ritual sequence. Subsystems are broadly divided into Purification and Performance. The Purification subsystem includes segments such as soul cleansing, defilement removal, and spirit installation, typically accompanied by actions involving purifying water, soul cloths, lamentation chants, kneeling, and ritual prostration. The Performance subsystem includes processions with gilgunak music, nanjang market-like gatherings, collective singing, and competitive performances, often involving musicians, coordinated formations, and audience participation.

Additional auxiliary subsystems are further differentiated only when the sample size permits; in the present study, they function primarily as boundary references between Purification and Performance.

- (3)

Symbolic Power

The third layer concerns symbolic power, operationalized as Power_Relation. This variable captures the degree of control each actor exercises over signifier production within a given event, measured on a 0–5 anchored scale: 0 = complete absence or purely passive presence; 1–2 = auxiliary participation; 3 = clear participation in signifier production; 4–5 = dominant control over signifier production. Power scores are assigned to the following actors: Shaman, Family, and Community.

The core analytical variables derived from this three-layer structure are summarized in

Table 2.

All coding procedures follow the revised codebook. The workflow consists of two stages: (1) iterative development and validation of the codebook, and (2) formal coding with reliability control. Given the sample size and data characteristics, the study adopts a primary-coder system combined with dual-coder pilot testing, ensuring reproducibility and internal consistency.

2.3. Analytical Strategy

Given the heterogeneity of documentary sources, distinct analytical strategies are applied to different evidence tiers, as summarized below (

Table 3).

All quantitative analyses are strictly restricted to Tier A materials, in order to avoid incomparability arising from source heterogeneity.

Analytical Units and Subset Construction

This section employs two event-level subsets.

(1) Main Analytical Set. The main analytical set includes all events containing at least one identifiable Canonical_Signifier, yielding a total of N = 154 events. This subset is used for signifier frequency analysis, event-level co-occurrence network construction, and descriptive comparative analysis, thereby maximizing sample size and revealing symbolic distribution patterns across different ritual types.

Within this set, Ssitgim-gut accounts for 92 events (59.7%), including 68 events from Jindo Ssitgim-gut (진도씻김굿; 73.9% of the Ssitgim-gut sample) and 24 events from Jeonnam Ssitgim-gut (전남씻김굿; 26.1%). These materials are primarily drawn from fieldwork video recordings and KCI/RISS archival sources, covering both purification and performance segments in full sequence, and are therefore well suited for analyzing symbolic power differentiation within subsystems.

Byeolsin-gut contributes 62 events (40.3%), including 45 events from the South Coast Byeolsin-gut (남해안별신굿; 72.6%) and 17 events from the East Coast Byeolsin-gut (동해안별신굿; 27.4%). These data are largely derived from official archival materials and Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) performance documentation, with an analytical focus on ritual transformation following institutional intervention.

(2) Strict Subset. The strict Tier A subset is a further refinement of the main analytical set, consisting only of audiovisual events with fully resolvable start and end timecodes, totaling H = 8 events. Tier A classification requires that each event have clearly defined temporal boundaries and allow complete reconstruction of action, soundscape, and participant relations from the recording.

Due to data constraints, all Tier A events currently derive from continuous, timecoded field recordings of Jindo Ssitgim-gut (1980–2020). Each event covers both a purification segment (≥60 s) and a performance segment (≥40 s), with no missing critical components. In contrast, most available Byeolsin-gut audiovisual materials consist of ICH-stage performances or documentary-style edited footage, which do not meet the 5–90 s event-level continuity and segmentability criteria, and are therefore not included in Tier A at this stage.

The primary function of Tier A is not sample expansion, but rather sensitivity testing and traceable evidentiary illustration. All events in this subset exhibit high coding confidence (Confidence = 0.90–0.95) and stable power-variable scoring, making them suitable for testing the robustness of findings regarding monopolar dominance in purification segments and collaborative co-performance in performance segments. Given the limited size and uneven ritual-type distribution of Tier A, this subset is not used as the main sample for cross-case statistical comparison, but only as supplementary validation. Future research will expand Tier A to include Byeolsin-gut events (planned n ≈ 4) to further test the model’s cross-ritual applicability.

2.4. Analytical Path

Symbolic Structure Analysis: The S-Axis examines event-level Canonical_Signifiers through frequency statistics and semantic co-occurrence network analysis. This step reconstructs the symbolic structure of the ritual and its distribution across different subsystems (Purification/Performance). Its purpose is to address the foundational question of how rituals operate through signifiers, providing the structural backdrop for subsequent power analysis.

Symbolic structure analysis is conducted primarily on the main analytical set (N = 154), with Tier A events used as traceable reference points where applicable. Visualizations and detailed results for the S-axis are presented in

Section 3.

Institutional Shift and Power Metrics: ΔPₛ × I

Institutionalization is operationalized through Institution_Flag, which constitutes the model’s I-axis. By comparing power distribution across event groups with different levels of institutionalization, the analysis tests whether institutional intervention leads to systematic transfer or reconfiguration of symbolic power among shamans, families, and communities.

The core metric is the event-level power differential ΔPₛ, which captures the directional change in symbolic dominance. Given the limited sample size and uneven distributions, the analysis avoids reliance on normality assumptions and primarily employs permutation tests and Fisher’s exact tests for group comparisons, while simultaneously reporting effect sizes to enhance inferential robustness and interpretability. Full model specifications and applied analyses are presented in

Section 4.

Data Preprocessing and Robustness Controls

All analyses are based on validated codebook imports of Canonical_Signifiers followed by standardized preprocessing. To avoid semantic distortion caused by translation smoothing, original Korean terms are retained in the master dataset. After cleaning and deduplication, the main analytical set contains 154 events, which form the basis for the signifier frequency table (

Table 4).

Frequency counts are event-based: if a given signifier appears in an event, that event is counted once for that signifier. A single event may contribute to multiple signifier counts. Event-level co-occurrence analysis calculates the number of events in which any two signifiers appear together, constructing an undirected weighted co-occurrence network, where edge weights represent the number of shared events. For clarity and visualization, only high-frequency nodes (top 12) are displayed.

3. Results

Within the analytical framework of this study, Ssitgim-gut is characterized by purification-oriented iconic signifiers and a low degree of institutionalization, whereas Byeolsin-gut is marked by performance-based composite signifiers and a high degree of institutionalization.

Which signifiers occur most frequently, and how do they cluster semantically? To address these questions, the following analysis compares the high-frequency canonical signifiers and their co-occurrence structures in Ssitgim-gut and Byeolsin-gut, and then summarizes the fundamental differences in their symbolic logics.

3.1. Frequency and Co-Occurrence of Canonical Signifiers

Table 4 presents the Top-12 canonical signifiers, ranked in descending order by the number of events in which they appear.

As shown in

Table 4, the most frequently occurring signifier clusters concentrate on appeasement of the deceased (상주 위로), community solidarity (공동체 연대), and themes directly associated with Ssitgim-gut, such as mangja cheondo (salvation of the dead) and gwakmeori ssit-gim. This distribution indicates that the sampled corpus is highly focused on discourses of mourning, consolation, and communal repair.

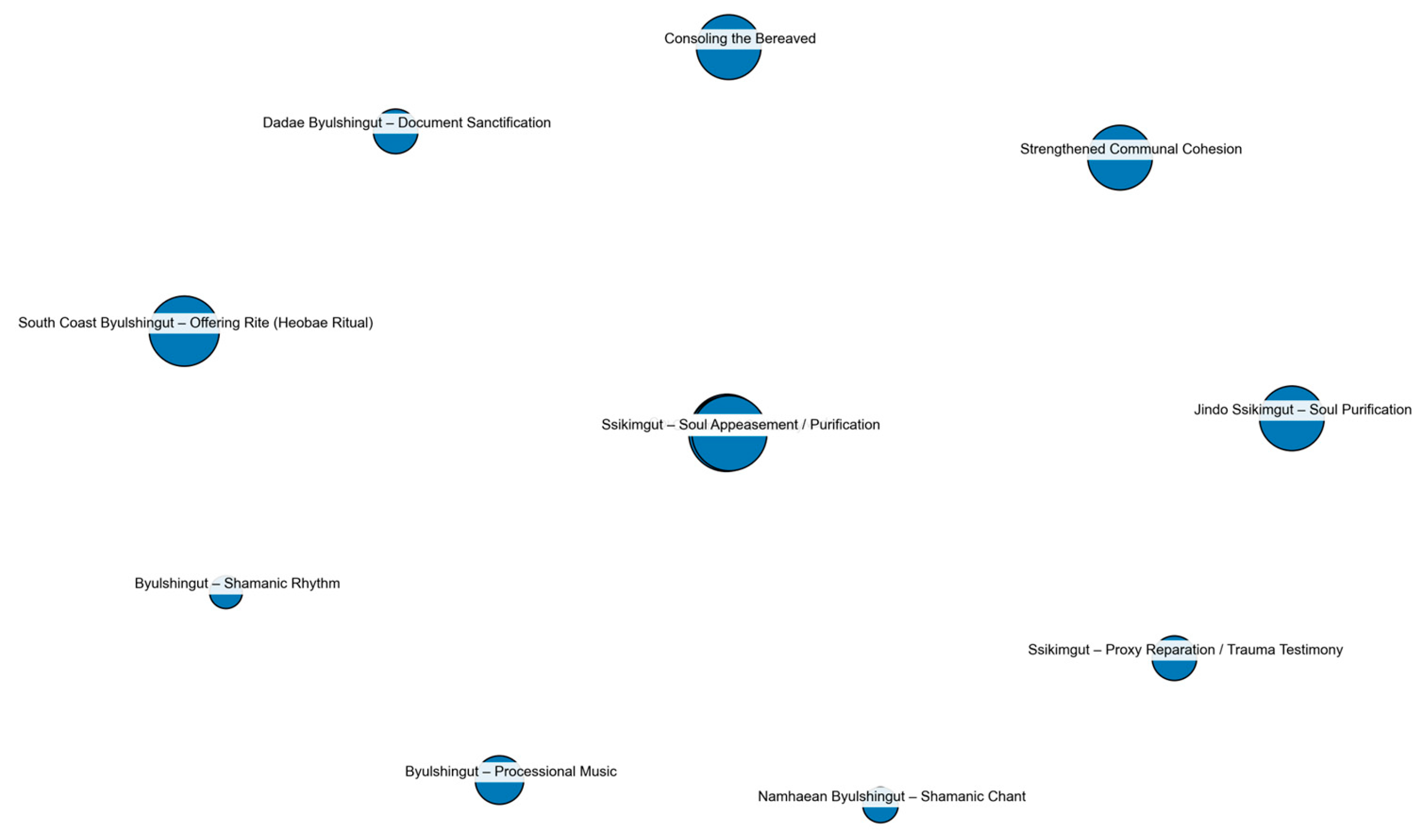

Figure 1 visualizes the event-level co-occurrence network of the Top-12 signifiers. Node size represents frequency, while edges indicate the number of times two signifiers appear within the same event.

The results reveal a tightly coupled semantic cluster: signifiers centered on community solidarity, consolation of the bereaved, and Gwakmeori Ssitgim-gut exhibit high co-occurrence within the Ssitgim-gut sample (φ > 0). In contrast, exhibition-oriented signifiers, such as Namhaean Byeolsin-gut_ollim mugwan, are significantly concentrated within Byeolsin-gut events.

3.2. Subsystems

3.2.1. Power Distribution

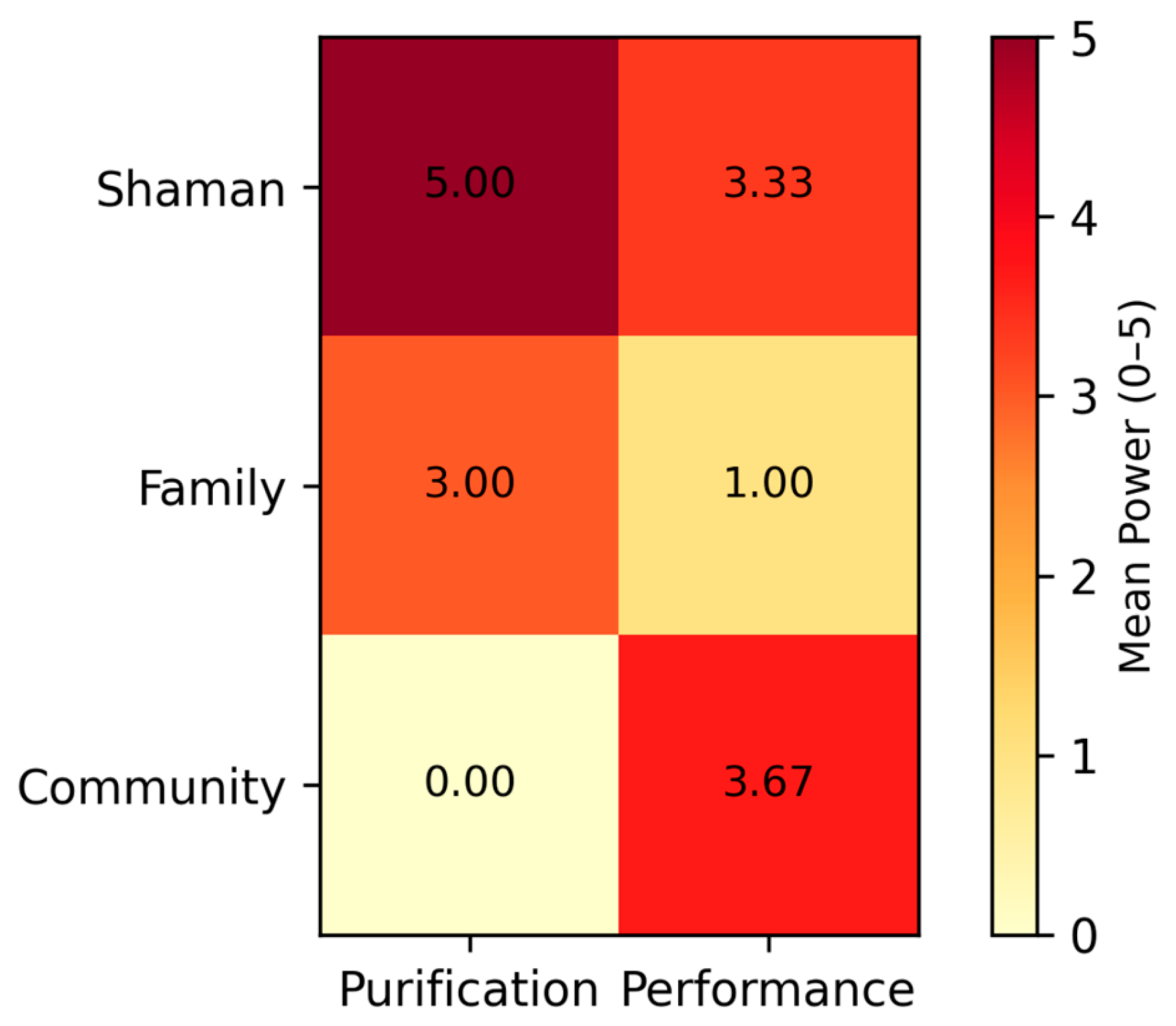

To visualize these differences more intuitively,

Figure 2 presents a subsystem–actor mean power heatmap. As shown in

Figure 2, power exhibits a unipolar concentration in the Purification subsystem, whereas a multi-nodal collaborative pattern emerges in Performance. The vertical axis lists actors, the horizontal axis indicates subsystems, and color intensity represents symbolic power magnitude. The purification segments form a unipolar concentration pattern, while the performance segments display distributed collaboration. This configuration is consistent with Pierre Bourdieu’s discussion of structural displacement within ritual power fields, wherein symbolic power shifts from unipolar dominance toward multi-point distribution through processes of institutionalization and spectatorialization.

3.2.2. Event-Level Differences

When ritual sequences are decomposed into events, subsystem differences become particularly clear. In Ssitgim-gut, the Purification segments exhibit a shaman-centered unipolar structure, in which the shaman generates symbolic elevation through coordinated use of vocal rhythm, bodily movement, and ritual objects.

In Event JINDO_SSIKIMGUT_EVT008 (

Lee and Cho 2022) the shaman faces the spirit altar, chanting loudly while beating the drum single-handedly. This manifests the unipolar purification feature, forming a focal semiotic configuration of iconic signifiers. In Event JINDO_SSIKIMGUT_EVT009 (

Lee and Cho 2022) the shaman repeatedly circles the altar while intensifying the drumbeat; voice, body, and object act in synchrony, forming a sound–body–object iconic triad. Repetition amplifies both the unipolar structure of the Purification stage and the shaman’s symbolic dominance.

In contrast, the Purification phase of Byeolsin-gut emphasizes ritual order and spatial sanctification rather than affective elevation. In Event NAM_BYUL_EVT002 (

Im 2006) the shaman performs the bujeong-gut—altar purification rite—holding a sacred banner while circling the ritual table, delineating sacred space through percussive rhythm (taak jangdan). Power ratings are PR_shaman 5, PR_family 1 supplying offerings only, and PR_community 0 spectators. The configuration is thus shaman-dominant, with auxiliary family participation and absent community engagement. Unlike Ssitgim-gut’s strongly collaborative pattern, Byeolsin-gut’s Purification relies solely on banner gestures and fixed rhythmic patterns; its iconicity lies only in the correspondence between the sacred banner and sanctified space, confirming that Byeolsin-gut’s Purification prioritizes functional order over emotional uplift.

Conversely, the Performance stage of Ssitgim-gut exhibits a multipolar power distribution. In Event JINDO_SSIKIMGUT_EVT013 (

Im 2006), the shaman leads a communal chorus; participants clap rhythmically and respond in time. PR_community 4, higher than PR_shaman 3 and PR_family 1, forming an interactive semiotic configuration of shaman–community co-performance.

In Byeolsin-gut, the Performance stage—linked to its nanjang (market-festival) and nongak (farm-music) attributes—shows even greater communal centrality. In Event NAM_BYUL_EVT001 (

Im 2006), the deulmaji–gilgunak procession is recorded: the village band controls the rhythm using sam-hyeon-yuk-gak haengaak (six-instrument procession), PR_musician 4; villagers march in step (PR_community 3), while the shaman merely directs the procession (PR_shaman 0). This forms a distributed power configuration, in which musicians, community, and shaman coordinate to share symbolic production.

Similarly, Event DADAE_BYU_EVT002 (

Heo 2023) shows the community competitively performing through the miyeok chaechwi-gwon (seaweed-harvesting privilege; explained in Event E_BYU012, 4.2). Here, PR_community 4 and PR_shaman 3 further verify Byeolsin-gut’s community-centered Performance structure.

3.2.3. Internal Heterogeneity Within Ssitgim-Gut

Ssitgim-gut exhibits regional heterogeneity between the Jindo type and the Jeonnam type. Differences in ritual emphasis and participant composition affect the magnitude of power distribution along the S-axis, but do not alter the core pattern of unipolar purification → collaborative performance. (

Table 5).

The influence of the two regional subtypes on the model’s S-axis is expressed primarily in the magnitude of power differentials. Within the Purification subsystem, both Ssikimgut subtypes exhibit a shaman-centered unipolar structure, yet with statistically meaningful differences in the degree of concentration. The Jindo subtype displays a strongly unipolar configuration, with shamanic power scores approaching the upper bound of the scale (ΔP_S ≈ 2.2), while both family and community participation remain at comparatively low levels. By contrast, the Jeonnam subtype, although still maintaining a unipolar structure, shows a marked convergence in power differentials (ΔP_S ≈ 1.3), accompanied by relatively higher levels of community participation in auxiliary purification practices.

Differences between the two subtypes become more pronounced within the Performance subsystem. The Jindo subtype exhibits a weakly coordinative structure: the shaman continues to occupy a dominant position, yet the power gap between the shaman and the community narrows substantially (ΔP_S ≈ 0.7). The Jeonnam subtype, in contrast, demonstrates a strongly coordinative structure, in which community power scores exceed those of the shaman (ΔP_S < 0), indicating a more balanced—and in some cases reversed—configuration of power relations during performance segments.

Overall, variation along the S-axis manifests primarily as amplitude modulation within a shared structural type. Purification segments retain a high degree of structural stability across both subtypes, whereas performance segments are considerably more sensitive to regional variation and ritual-type differentiation.

3.3. Institutionalized Contexts

Differences in the degree of institutionalization also exert a direct influence on the structure of ritual signifiers and the allocation of symbolic power. First, in events coded as Institution_Flag = 1, ritual signifiers exhibit pronounced characteristics of scriptization and performativization. Compared with non-institutional events, institutionalized events contain a higher proportion of signifier units that are fixed in the form of subtitles, checklists, or procedural texts. As a result, the variability of ritual action is reduced, and the combination of signifiers becomes more stable. In such contexts, the generation of symbolic meaning relies more heavily on predefined texts and exhibition frameworks.

From the perspective of power distribution, observable shifts occur among actors in institutionalized events. In institutional Ssikimgut cases, the shaman continues to maintain relatively strong control over ritual action; however, the overall power scores of family members and community actors decline, leading to a contraction in the range of participants involved in symbolic production. In institutional Byeolsin-gut events, although the shaman remains dominant at the level of ritual execution, the degree of autonomous participation by community actors decreases. Their symbolic power is expressed primarily through the fulfillment of prescribed actions according to established texts, rather than through on-site negotiation or improvisational meaning-making.

In contrast, non-institutional events (Institution_Flag = 0) display substantially greater flexibility in their signifier structures. The combinations of signifiers that emerge during the ritual depend more strongly on live interaction and real-time adjustment, and community members play a more active role in performance and rhythmic coordination. Correspondingly, the distribution of power more closely approximates a multi-nodal coordinative structure, with the community’s weight in symbolic production significantly higher than in institutionalized settings.

This contrast is particularly pronounced in the Byeolsin-gut sample. In institutionalized events, performance-related segments account for a larger proportion of the overall ritual structure, and the number of performative units increases. In non-institutional events, although performance segments are still present, their mode of unfolding and scale of participation depend more heavily on situational conditions and community negotiation. Overall, an increase in institutionalization is positively associated with the intensification of performative components.

Taken together, these findings confirm that institutionalization does not simply alter the basic subsystem structure of rituals, but instead substantially reshapes the organization of signifiers and the configuration of power among actors.

4. Discussion

As discussed in the preceding sections, changes in the degree of institutionalization reorganize the structural positions of who is entitled to interpret symbolic meaning within ritual contexts through a series of processes of symbolic translation. From the perspective of the DSRR model, an event-level analytical approach makes it possible to examine institutional effects along the I-axis, thereby revealing the underlying logic of power allocation. Viewed in this way, institutionalization is not merely an external condition but a mediating mechanism through which interpretive authority is redistributed across ritual actors.

In institutionalized Byeolsin-gut events, signifiers become scripted and the economic dimension is administratively codified. While the shaman retains nominal ritual leadership, interpretive authority shifts to institutional texts. In Event DADAE_BYU_EVT001 (

Heo 2023), the archive prescribes Jidong-gut–Jidong-gwe sacralization: offerings must include three fresh fish and five jin of rice (textualized signifiers), and village elders must line up by seniority to present offerings (proceduralized actions). PR_shaman = 5.00 (ritual leadership maintained), but PR_community 2, contrasting with the non-institutional NAM_BYUL_EVT005 (

Lee and Cho 2022). Interpretive control moves from on-site shaman/community negotiation to archival texts.

In Event DADAE_BYU_EVT003 (

Heo 2023), the ingujeon funding scheme converts ritual participation into an administrative obligation; PR_family 1 (payment only, no symbolic production), evidencing institutional control over interpretive power.

By contrast, non-institutional Byeolsin-gut retains living-ritual characteristics: signifiers remain flexible and community participation is autonomous. In Event NAM_BYUL_EVT005 (

Lee and Cho 2022), the sam-hyeon-gok performance features village musicians improvising on Jindo Ssitgim-gut melodies; the shaman adjusts chants to the musicians’ rhythm, and community members freely join the chorus (PR_community 3). Signifier production relies entirely on live interaction without textual constraint—contrasting the scripted offerings of DADAE_BYU_EVT001 and confirms that non-institutional contexts preserve primordial symbolic power structures.

From event sequences and archival records, Byeolsin-gut presents a composite village-rite structure. On the one hand, it follows an invite–settle–send logic with the backbone sequence bujeong-gut → dangmaji-gut → cheongjwa-gut → Sejon/Sungju → gunung → geori-gut On the other hand, it overlays the rural/fishing economy and a nanjang-style market-festival layer as an exhibitional shell. Accordingly, Byeolsin-gut can be summarized as operating along three signifier axes: (1). Order–Purification Axis: Signifiers that establish ritual order through spatial purification and the installation of divine seats. (2). Community Reaffirmation Axis: Signifiers that reaffirm boundaries and reciprocal contracts across the hierarchy of household gods → village community → occupational deities. (3). Exhibitional Externalization Axis: Signifiers that translate ritual symbols into festival performances, yielding an outward-facing ritual text.

At the level of embodied reconstruction, Event JINDO_SSIKIMGUT_EVT013 (

Lee and Cho 2022) shows the village band leading the affective contour of the rite through drum patterns, thereby reinforcing the semiotic logic “greater community participation → stronger exhibition”, and forming a bipolar collaboration with the shaman In Event E_BYU006 (

Lee and Cho 2022), the juxtaposition of altar, flags, sea-deity offerings, and percussion creates a tri-modal resonance of sound–object–action. Drumbeats and chant meter stratify time; altar and flag order structure space; the seating of the deity and the encircling of participants focalize relations. The result is a pattern that rises, diffuses, and re-converges, consistent with classic ritual-process schemas.

At the micro level, Byeolsin-gut’s power-distribution logic mirrors that of Ssitgim-gut. In the 1982 Tongyeong tape (III.3.8) and JINDO_SSIKIMGUT_EVT013, families possess no independent signifier production rights, hence Power_Family = 1.00, achieving a point-to-point correspondence between numerical ratings and observed scenes. In Event E_BYU007, the shaman and the village band divide functions: the drum corps controls tempo and affective curve, the shaman concatenates segments into a divine genealogy logic, and village elders and occupational representatives occupy the spatial center—all are fully aligned.

Event E_BYU008 records Jeong Young-man, noting that after the 1980s, nanjang segments of Byeolsin-gut had to be pre-reported to local government, and themes of skill-competition once decided autonomously by the village now must conform to ICH display requirements. This corroborates institutional discipline over the exhibitional externalization axis. A different route appears in E_BYU012–E_BYU013: Event E_BYU012 and Event E_BYU013 show that institutions textually codify the economic dimension.

From 1864–1907 in the Modaepo area, core documents on gwakjeon sales indicate that in E_BYU012, the formerly oral miyeok chaechwi-gwon (seaweed-harvesting privilege), once negotiated by village elders and the shaman, was quantified into administrative text. The rules specify, for example: contributors to offerings in the gunung segment—such as an elder representing a lineage bringing sea-deity offerings—gain a 20% increase in drawing weight; when the shaman presides over cheongjwa-gut, the shaman’s lineage automatically receives one priority harvesting share; households not participating in bujeong-gut lose eligibility for that season’s lottery. Traditionally, seaweed rights were judged flexibly—by shamanic assessment of ritual piety and elders’ assessment of everyday communal contribution—with affective leeway. In E_BYU013 (1918 Modaepo village ingujeon), the key move is converting community-organized fundraising into an administrative obligation: entries are tabulated by household population, stipulating 1.5 jeon per person (Joseon-era currency), including infants and elders, earmarked explicitly for Byeolsin-gut nanjang staging and Sejon-gut offerings. Thus communal mutual aid is translated into administrative rule, enhancing the institution’s definitional power over the ritual economy. Together these demonstrate that economic textualization is a core pathway for institutions to seize interpretive authority.

The impact of this shift is perceptible: 1918 records, together with the shaman’s testimony, note that participants’ kneeling gestures became mechanical, lacking former devotional intensity. While textualized economic obligations ensure material execution, they erode the primordial affective meaning—and this valuation is determined by the institution.

At this point, the so-called Dual-Axis Symbolic Regime Model (DSRR) can be summarized as being shaped by two principal axes: (1) the subsystem structural axis (S-axis: Purification ↔ Performance), and (2) the axis of institutional intervention (I-axis: Institutionalization). Together, these axes determine how signifiers are generated, specifically how symbolic meaning shifts from forms grounded in bodily enactment and affective intensity toward alternative regimes of organization and interpretation.

To facilitate empirical testing and cross-case comparison, the three propositions advanced below adopt ΔP_S ≡ Mean(Shaman) − Mean(Family) as a unified operational measure.

4.1. Model Propositions

H1. Structural differentiation proposition.

Within the same ritual, Purification segments exhibit significantly greater power differentials than Performance segments. Using version v3.1 as an illustration (

Table 6):

Across the v3.1 event set, this contrast is highly stable. In Purification segments, the mean Shaman–Family power gap consistently ranges between +1.8 and +2.2. In Performance segments, power configurations converge toward a localized multipolar structure characterized by Shaman ≈ Community > Family.

(Note: In certain subsystems, Community participation yields n < 5; related values are therefore descriptive rather than inferential.)

Purification and Performance thus constitute two distinct politico-semiotic structures: the former relies on iconicity and bodily intensity, while the latter depends on coordination and outward perceptibility. This constitutes the first pillar of the DSRR model.

H2. Institutional bias proposition.

Increasing institutionalization intensity (I) is positively correlated with textualization traces. As textualization increases, so do subtitle density, the proportion of scripted segments, and the use of archival-style camera framing. Concurrently, iconicity weakens while combinatory signifiers gain prominence: bodily symbolism in Purification segments is attenuated, whereas performative clusters (e.g., parades, music ensembles, group participation) increase in institutionalized contexts.

After controlling for shot length and narration variables, the effect of I on the textualization index remains significant (β = 0.41, p < 0.05), indicating that institutional effects are independent of media-editing techniques. This proposition demonstrates that institutions are not neutral recorders, but actively restructure signification by privileging display-ready units. Consequently, the DSRR model acquires policy-diagnostic capacity.

H3. Historical institution–ritual coupling proposition.

Since the establishment of the Cultural Property Protection system in South Korea in 1962, preservation strategies have favored performance, segmentation, and touring. Within this institutional framework, the composite festival form of Byulshingut aligns well with project-based and budgetized governance. By contrast, the kinship-centered purification logic of Ssikimgut resists public staging, resulting in administrative coding that tends toward genealogical, unitary objects.

During the 1990s, cultural industry and tourism policies emphasized visibility, reproducibility, and circulation. Under these conditions, Byulshingut gained programmatic and cinematographic advantages due to outward-facing performative units such as processions, military-style music, and nanjang (난장, carnival–market) segments. Cultural city initiatives in the 2010s further reinforced Byulshingut’s institutional adhesion. It is precisely this triple coupling of historical phase × ritual type × policy orientation that explains why Byulshingut accumulated advantages in institutionalization, archiving, and festivalization, while Ssikimgut retained high symbolic density at its religious core and a constrained performative boundary.

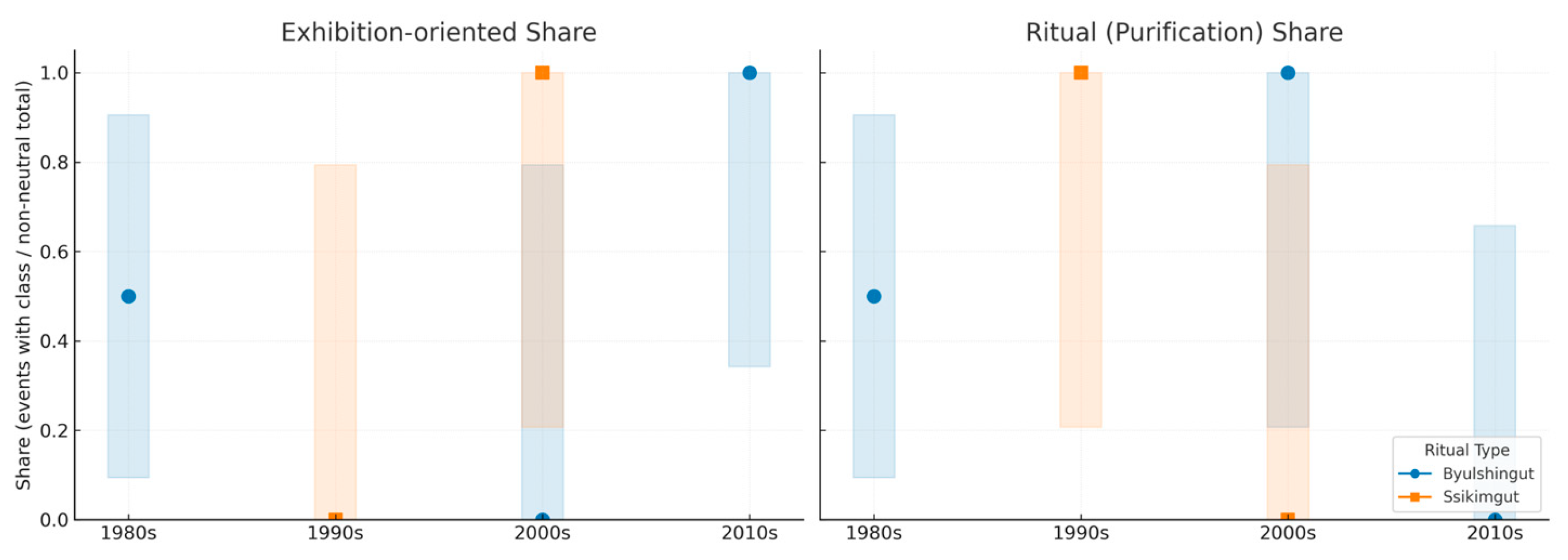

This proposition provides a historical genealogy for the institutional bias identified in H2. To test this triple coupling, the study classified event-level signifiers by policy period (display clusters vs. purification clusters) and plotted the proportion of display-oriented signifiers using Wilson 95% confidence intervals. The results are consistent with the proposed coupling logic.

One clarification is necessary. Although South Korea promulgated the Intangible Cultural Heritage Act in 2016, revising the 1962 principle of “original-form preservation” toward “maintenance of typicality” and formally encouraging innovation, its practical impact has been limited. As noted by Kim Hyung-Kun, changes in legal wording alone are insufficient to resolve structural dilemmas in practice. Accordingly, this institutional juncture was not incorporated as a separate variable in the present dataset.

H3 thus demonstrates that institutional bias is not a contingent byproduct of contemporary media or archival technologies, but rather the outcome of a half-century of governance trajectories interlocking with ritual structural properties. It constitutes the historical foundation of the DSRR model.

In sum, H1–H3 jointly constitute the theoretical scaffold of DSRR:H1 elucidates structural differentiation within rituals; H2 reveals how institutional intervention reshapes signifier production and interpretive authority; H3 uncovers the historical roots of institutional bias. Together, these propositions endow DSRR with testability, cross-ritual applicability, and policy-diagnostic utility, thereby providing a coherent analytical basis for governance implications.

4.2. Policy Shifts and Heritage Governance

Since the 1960s, South Korea’s cultural policy has continuously elevated the outward-oriented signifiers of Byulshingut through an institutional logic that prioritizes exhibition. This logic has generated cumulative advantages along the institution–text–image chain. By contrast, the purification-based iconic signifiers of Ssikimgut, due to their non-performable nature, have consistently maintained a symbolic structure that remains at a distance from institutional incorporation. The divergence between the two rituals represents the long-term sedimentation of institutional bias at the site of signifier production.

Figure 3 traces how exhibition-oriented and ritual signifiers shift across policy periods, with key policy nodes anchored to clarify the policy–signifier mechanism. Under the constraint of n ≥ 5, most cells are presented as point estimates only; nevertheless, the overall directionality aligns with historical institutional logic.

Following the 1990s, exhibition-oriented signifiers in Byulshingut rise sharply and retain dominance under the urban cultural policy framework of the 2010s. This trajectory is driven by policy mechanisms that continuously select for displayable units. The outward orientation, camera compatibility, and scriptability of exhibition signifiers render them intrinsically suited to the institutional requirements of intangible cultural heritage (ICH) projectization and festivalization. As policies progressively reinforce project evaluation criteria, festival-scene design, and audiovisual archiving procedures, the signifiers of Byulshingut are incrementally absorbed into institutional texts, forming a recursive loop of policy demand → signifier selection → proportional increase.

By contrast, the purification-based iconic signifiers of Ssikimgut. its signifier structure remains highly stable across policy periods. This structural stability reflects both the ritual’s religious core and the limited institutional tolerance for primary iconic signification. The results demonstrate that institutional intervention functions not merely as a recording mechanism but as a secondary site of signifier production, introducing directional bias in interpretive authority, visibility, and symbolic power allocation.

At the signifier level, the most immediate manifestation of institutional bias is the redistribution of interpretive authority. Based on event-level data, samples with Institution_Flag = 1 exhibit an average narration rate of 72%, whereas locally audible community speech segments account for less than 15%. The former constructs institutional legibility; the latter is compressed into a merely symbolic position of participation.

According to the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, community participation constitutes a core principle of ICH protection. In practice, however, local groups are often involved only nominally, giving rise to a participation paradox in which communities participate without exercising interpretive agency. In the present sample, Institution_Flag = 1 events again show an average narration rate of 72%, with community members’ audible speech accounting for less than 15%. This discursive compression indicates that while institutionalization expands visibility, it simultaneously erodes spaces for indigenous interpretation. Accordingly, heritage governance should expand participation into interpretive participation, whereby local communities not only execute rituals but also possess the right to review and reinterpret texts, images, and scripts.

Based on the above analysis, the DSRR model yields three actionable implications for governance.

First, the definition of “participation” should be expanded. Institutional procedures should allow local communities to review key interpretive materials—such as audiovisual scripts, subtitles, and nomination texts—rather than reserving semantic authority exclusively for administrative and media actors. This is especially critical for highly iconic rituals such as Ssikimgut, where local interpretive authority safeguards the density of religious meaning.

Second, iconicity-based units should be treated as heritage objects in their own right, rather than as limitations on exhibition. Policies should incorporate non-performable yet semantically dense iconic signifiers into the scope of protection, instead of focusing solely on publicly presentable ritual segments. Such an approach would prevent institutions from continuing structural selection based exclusively on exhibition-oriented signifiers.

Third, a principle of policy-neutral audiovisual archiving should be established. Visual documentation should not be centered on festival or performance standards alone, but should also include primary ritual structures, unscripted segments, local narratives, and bodily iconicity. This archival logic would help attenuate institutional bias along the I-axis, ensuring that Byulshingut and Ssikimgut no longer exhibit systematic disparities in institutional visibility.

In sum, intangible heritage governance is not merely an act of preservation, but a form of institutional engineering that redistributes signifier dominance and reshapes local interpretive authority. The contribution of this study lies not only in explaining differences in shamanic ritual semiotic structures, but also in providing a semiotic diagnostic tool for identifying institutional bias. This tool enables policymakers to discern which rituals lose meaning through institutionalization and how institutions facilitate the cumulative advantage of particular signifiers. In this sense, the proposed model demonstrates external validity beyond the individual cases, at both theoretical and policy levels.

4.3. Model Validation and Robustness Checks

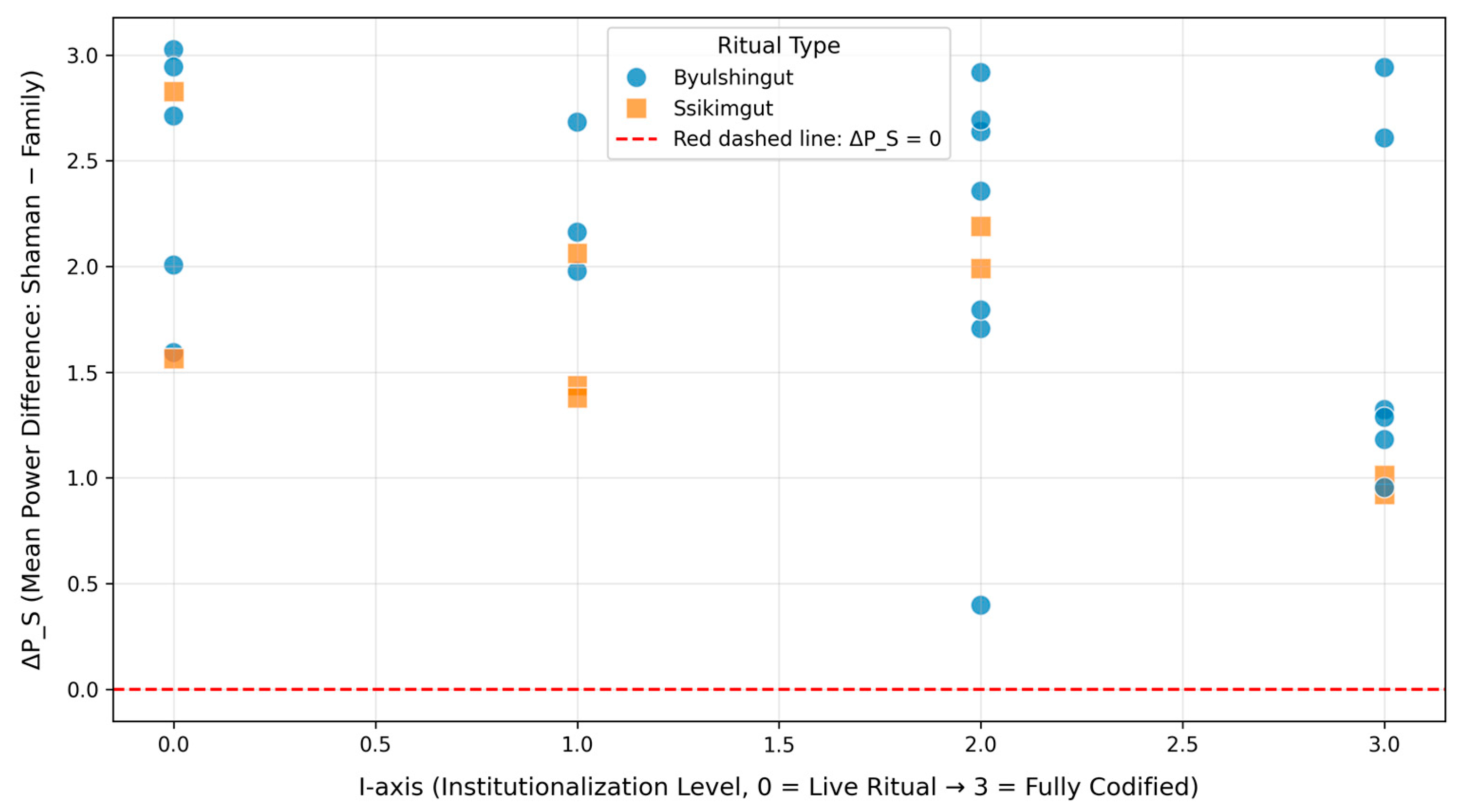

To ensure the testability and external validity of the DSRR model, this section conducts a model validation based on the distribution of the event-level power differential

along the institutionalization axis (I-axis). The objective is to verify whether increasing institutional intensity is accompanied by a decline in shaman-centered symbolic advantage, and whether ritual power consequently shifts toward a structure of institution–community bipolar coordination. The analysis employs event-level scatter inspection, lineage-fixed-effect controls, and multiple robustness checks to test the directional propositions of the model.

Figure 4 illustrates the event-level distribution of ΔP_S along the I-axis. The fitted trend line exhibits a clear negative association, indicating that as institutionalization increases from I = 0 (non-scripted) to I = 3 (fully textualized), shamanic symbolic dominance no longer remains exclusive. Instead, the symbolic power of family members and the community gradually increases, with ΔP_S converging toward zero. This pattern reflects a transition from a unipolar power structure to a coordinated, multi-actor configuration. The downward trend closely corresponds to the matrix analysis presented in

Section 3.2 and provides direct support for the institution–signifier–power coupling mechanism proposed in H2.

The event distribution further reveals a clear typological differentiation. Byulshingut events are concentrated in the I = 2–3 range, with relatively low ΔP_S values, indicating a dual-polar structure involving institutions and the community. In contrast, Ssikimgut events cluster in the I = 0–1 range, where ΔP_S remains high and the ritual retains a shaman-centered iconic structure. The divergent trajectories of the two ritual types within the I–S space are fully consistent with the historical and policy analysis presented earlier.

To ensure that the model’s results are not confounded by factors such as media-editing practices, narration rates, or archival text quality, a series of robustness checks was conducted. All tests yield results consistent with the model’s directional expectations:

Excluding events with Institution_Flag = 1, the negative association between ΔP_S and I remains, indicating that the observed trend is not driven by archival bias.

Excluding events with Confidence < 0.8, the main effect remains stable, with correlation coefficients varying by less than 0.05.

Nonparametric tests show that ΔP_S in the high-I group is significantly lower than in the low-I group, supporting the institutional–power coupling effect.

Structural correlation analysis confirms that the direction of association between ΔP_S and I is consistent with the event-level scatter pattern.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that the DSRR model exhibits consistent explanatory power across multiple data slices and analytical specifications, reinforcing its robustness and suitability for cross-case comparison.

5. Conclusions

The author argues that the DSRR model proposed in this study partially avoids the oscillation that often characterizes theoretical explanations of ritual between religious essentialism and institutional determinism. A review of the model itself clarifies this point. Along the S-axis, Purification and Performance are not merely functional ritual segments; they constitute two distinct symbolic regimes that significantly reshape both signifier configurations and positions of power. This distinction explains why the iconic structure of Ssikimgut demonstrates a high degree of structural stability, whereas Byulshingut more readily forms a multi-nodal system of signifier production in coordination with local communities and institutional actors.

Along the I-axis, increasing institutionalization intensifies the selective filtering of signifiers. As scripting, archiving, and visual disciplining are reinforced, iconic signifiers weaken while textualized elements expand in proportion. Correspondingly, ritual power configurations shift from a shaman-centered structure toward an institution–community collaborative structure. From this perspective, the divergent institutional trajectories of Byulshingut and Ssikimgut are rooted not only in their distinct religious genealogies, but also in the structural consequences of institutional mediation.

From a methodological standpoint, the event-level coding system employed in this study reduces dependence on long-form ethnographic narration and enables the signifier structures of Ssikimgut and Byulshingut to be examined on a commensurable analytical scale across different institutional contexts. This strategy provides the foundation for the model’s operational viability. By integrating signifiers, subsystems, actors, and institutionalization variables into a single analytical matrix, the model preserves ethnographic semantic granularity while achieving structural stability suitable for quantitative analysis. In this sense, the modal power matrix represents a methodological innovation within contemporary ritual studies.

The compression of iconicity, the emergence of collaborative structures, and the effects of institutional bias within rituals can thus be rendered visually explicit, offering intuitive empirical evidence for patterns of symbolic production and power distribution. Moreover, the ΔP_S indicator provides a standardized, cross-case metric for analyzing ritual power configurations, enabling power structures across different ritual genealogies, institutional phases, and performative units to be compared along a single numerical axis. This approach simplifies complex symbolic interactions and allows the directional effects of institutionalization on power differentials to be tested through scatter plots, nonparametric tests, and stratified models, thereby enhancing the falsifiability of theoretical propositions.

Turning to heritage governance, the author contends that the model yields three principal insights for policy practice. First, as discussed in

Section 4, exhibition bias constitutes a core structural mechanism in contemporary heritage governance. Policy frameworks tend to privilege signifier units that are displayable, camera-friendly, and amenable to scripting, thereby enabling outward-facing, composite symbols to accumulate institutional advantage. This mechanism reshapes the visible structure of rituals and alters their symbolic ecology, marginalizing or diluting segments that rely on corporeality and iconicity under institutional intervention. This bias indicates that the protection of iconic units cannot rely solely on nomination documents or audiovisual recordings; instead, it requires an identification framework that transcends exhibition-based criteria.

Second, institutionalization entails a redistribution of interpretive authority. Event-level evidence demonstrates that in highly institutionalized contexts, official narration, subtitles, and standardized scripts frequently occupy the core of interpretive power, while local voices are compressed into a merely symbolic position. Although this enhances institutional readability, it weakens the community’s capacity for semantic generation, producing a practical paradox in relation to the UNESCO Convention’s principle of “participation.”

Third, highly iconic rituals—exemplified by Ssikimgut—face pronounced institutional vulnerability. Positioned asymmetrically within institutional selection processes, such rituals experience reduced visibility and a contraction of their space for survival within policy systems. The protection of these rituals therefore requires differentiated safeguarding pathways, including strengthened recognition of iconicity and the preservation of religious contextual integrity.

6. Prospects

The author proposes that future research and governance practice should advance along the following directions.

To strengthen the generalizability of I-axis effects and enhance cross-lineage comparative capacity, additional retrievable Tier A events for Byulshingut should be incorporated in the short term to improve sample balance. In the medium to long term, Tier A should be expanded to include at least twenty retrievable events per ritual type, thereby increasing the statistical robustness and external validity of estimates relating ΔP_S to institutionalization indicators. At present, the model’s conclusions are valid but conservative; future expansion will render them stronger rather than different. Such enlargement will also facilitate more fine-grained lineage fixed-effect analyses and the implementation of multilevel mixed-effects models.

With respect to coding reliability, the current study’s dual-coder pilot test on a 20% subsample indicates that both categorical and continuous variables achieve acceptable preliminary reliability. However, to ensure long-term reproducibility, full-sample double coding should be conducted following sample expansion. Variables exhibiting persistently low reliability should be addressed either by:

- (a)

redefining variables and adjusting anchoring criteria;

- (b)

applying down-weighting strategies in inferential analyses.

Further institutionalizing the average confidence score of primary coders will help reduce the systematic influence of subjective bias.

Future research may also integrate event-level coding with computational methods. For example, computer vision techniques could be employed to automatically identify purification action sequences, while speech and subtitle analysis could be used to estimate narrativization rates. Such approaches would enhance the feasibility of cross-regional comparisons and enable indicators such as ΔP_S to be operationalized as automatically computable, cross-case quantitative measures.

Building on the findings of this study, future work is encouraged to design intervention-based experiments within local intangible heritage project reviews, audiovisual archiving protocols, and performance evaluations. Examples include implementing interpretive review procedures that grant communities the right to audit performance scripts, narration, and subtitles, or requiring archival standards to document original, non-scripted segments and publicly disclose metadata. Through pre–post comparative designs, researchers can assess the effects of interpretive participation on ΔP_S, narrativization rates, and the proportion of audible community voices, thereby translating semiotic diagnosis into empirically testable governance outcomes.

Finally, although this study is grounded in the Korean context, the underlying mechanism is not region-specific. Any ritual field undergoing institutionalized heritage governance—such as East Asian sacrificial traditions or Southeast Asian healing rites—can be used to test the cross-cultural robustness of H2: namely, whether increases in institutionalization intensity are consistently accompanied by the convergence of ΔP_S, and whether the cumulative advantage of exhibition-oriented units follows similar trajectories across different cultural and institutional settings.