Abstract

This paper discusses the Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao, or “chart of Lord Lao” for short, a document drawn up, preserved, and utilized by a local Taoist altar in the border region of Hunan and Jiangxi provinces in southeastern China. This chart illustrates the body of the Most High Lord Lao (Taishang Laojun), with various parts labelled with sacred spaces, deity names in textual form, and ritual instructions. As such, the document elucidates the interconnectedness between the body, cosmos, and rituals within local Taoist beliefs. This article aims to analyze the chart of Lord Lao by comparing it with ritual texts, the liturgical tradition of the Taoist altar, and texts from the Ming dynasty Taoist Canon. Through this analysis, it becomes evident that the chart of Lord Lao and its associated practices reflect an intricate relationship between different layers of Taoist traditions. This includes the connections between classical Taoism and the emerging ritual traditions of exorcism during the Song and Yuan dynasties, as well as the interplay between these emerging traditions, such as the Correct Rites of the Heart of Heaven, and more local traditions of exorcism, such as the Rites of Mount Lü.

1. Introduction

Exploration of the relationship between the body, cosmos, and ritual is a fundamental theme in Taoist studies. Previous research has primarily focused on analyzing written records of transmitted Taoist texts. Kristofer Schipper’s discussion on Taoist perspectives on the body is informed by texts such as the Zhuangzi 庄子, Basic Questions on the Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi neijing suwen 黄帝內經素問), and Central Scripture of Laozi (Laozi zhongjing 老子中經) (Schipper 1995, [1982] 2007, pp. 137–53), while John Lagerwey has analyzed the Central Scripture of Laozi (Lagerwey 2004). Schipper’s work references the Diagram of Inner Canon of the Limitless (Wuji neijing tu 無极内經圖) from the Mingshan Bookstore 明善書局 in Tainan (Schipper [1982] 2007, p. 143), but does not delve further into its analysis. A significant study that focuses on images as a primary source is Catherine Despeux’s systematic examination of the Chart for the Cultivation of Perfection (Xiuzhen tu 修真圖). Despeux’s monograph, first published in 1994, is divided into four main sections: charts of Taoist human body based on the Chart for the Cultivation of Perfection; the main body parts depicted in the chart; the human body, Heavenly Realm, and Taoist Hells; and Taoist ritual methods (Despeux 1994, 2012, 2018a, 2018b). Louis Komjathy analyzes the Taoist perspective on the body using the Diagram of Internal Pathways (Neijing tu 內經圖) as a primary source (Komjathy 2008, 2009). While Despeux and Komjathy’s studies primarily draw from images in the classical tradition, the works of Brigitte Baptandier, Patrice Fava, and Liu Jinfeng are primarily based on local images discovered during their fieldwork. Baptandier analyzes the Chart of the Residence of the Buddhist Holy Spirits (Fosheng suoju zhi tu 仸聖所居之圖) and Chart of the Catching of Ghosts (Zhuogui zhi tu 捉鬼之圖), preserved and utilized by the masters of the school of Mount Lü 閭山派 in Eastern Fujian (Baptandier 2016). Among these documents, the Chart of the Residence of the Buddhist Holy Spirits, despite being labeled with the term “Buddhist” (fo 仸, i.e., 佛), in fact aligns with the Taoist system of deities and falls within the realm of Taoist imagery with a distinct influence from the Rites of Mount Lü. Fava’s examination of the Chart of Body for the Cultivation of Perfection (Xiuzhen shenxiang zhi tu 修真身像之圖) and Chart of the Skeleton of Lord Lao (Laojun kulou tu 老君骷髏圖), found in the Alchemical Secrets of the Supreme Ultimate (Taiji lianmi 大極鍊秘), an early Qing (1644–1911 CE) Taoist manuscript from western Jiangxi, focuses on exploring the connections between this chart of Lord Lao and a separate chart for the Taoist liturgy of presenting petitions (Fava 2014, pp. 88–91; 2018). In 1998, Liu Jinfeng discovered the Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao (Laojun daofa tu 老君道法圖, Figure 1) at the Shanglong Altar in Chongyi county, southern Jiangxi. His recent report delves into the relationship between this chart and Taoist ritual practices (Liu 2024, pp. 4–14).

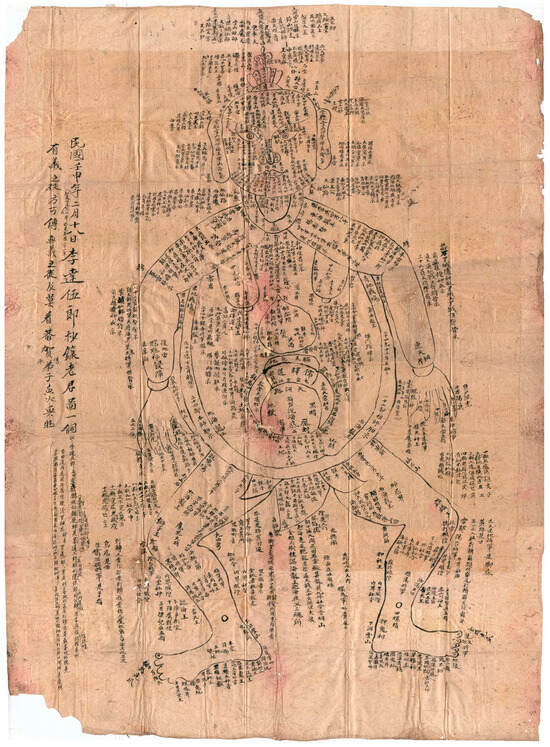

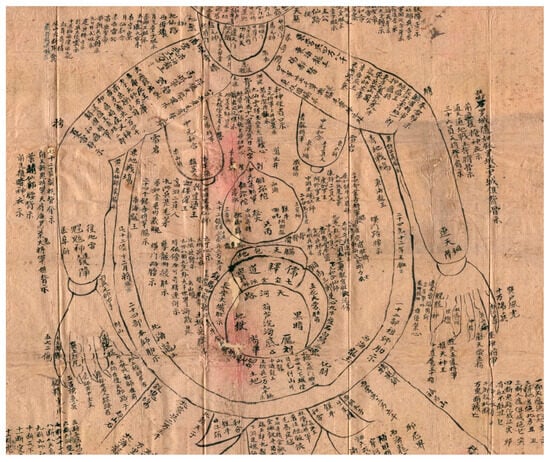

Figure 1.

The Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao at Shanglong Altar.

With the assistance of Liu Jinfeng, the author visited Shanglong Altar over the past two years and collected the Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao along with related ritual texts. This collection contains valuable information, particularly regarding the interplay between the body, cosmos and rituals as contained within local Taoist beliefs. While Liu has conducted a thorough analysis of the relationship between the chart of Lord Lao and contemporary Taoist ritual practices, there remains ample room for further discussion on the spatial and historical dimensions of this chart, as well as its origins. Therefore, with Liu Jingfeng’s approval, the author plans to expand upon Liu’s research and conduct a more in-depth analysis of this chart to enhance our understanding of its significance. This article aims to analyze the structure and content of the chart of Lord Lao, examining its significance in ritual practices by comparing it with ritual texts, the liturgical tradition of the Taoist altar, and texts from the Taoist Canon 道藏 of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 CE). Through this analysis, it becomes evident that the chart of Lord Lao and its associated practices reflect an intricate relationship between different layers of Taoist traditions. This includes connections between classical Taoism and the emerging ritual traditions of exorcism during the Song and Yuan dynasties (960–1368 CE), as well as the interplay between these emerging traditions, such as the Correct Rites of the Heart of Heaven (Tianxin zhengfa 天心正法), and more local exorcistic traditions, such as the Rites of Mount Lü (Lüshan fa 閭山法).

2. The Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao and Related Texts of the Shanglong Altar in Southern Jiangxi

The Shanglong Altar1 上壠壇 (Altar of Upper Ridge) examined in this paper is located in Junyuan village, Shangbao township, Chongyi county, Ganzhou city, southern Jiangxi. Like other Taoist altars in Shangbao, Shanglong is a hearth-dwelling 火居 Taoist altar whose masters marry and live domestically. Masters perform both military/Yang 武/陽 and civil/Yin 文/陰 rituals. Military rituals involve, primarily, worshipping the heavens, repaying the gods, praying for good fortune, healing illness, controlling fire, and pacifying and purifying the earth, representing the “pure” rituals 清事 that are part of the local Taoist tradition of Jiao 醮 (sacrificial offering) liturgy and exorcism. Civil rituals focus on the salvation of the deceased and are known as “salvation” rituals 濟度法事. In most Taoist altars, funeral salvation rituals exhibit a strong Buddhist influence, mainly derived from the Buddho–Taoist tradition of the Pu’an school 普庵教. In contrast, salvation rituals of some altars derived from the Anterior Heaven school 先天教, which is basically a Taoist tradition with a slight Buddhist influence. Both schools incorporate military rites, particularly in the ritual of “refinement for liberation” 鍊度 and the “Audience for Departure from the Mountain” 出山朝. The former ritual aims to release the souls of those who have died violently, while the latter, also known as “liturgy of announcement” 奏科, is dedicated to deceased Taoist priests, “laymen” with their souls “locked up” 上鎖 in the Official Residence of Lord Lao 老君衙 for protection and given a ritual name, as well as mediums and hunters who set up altars in their homes.2 It is particularly worth noting that when the Taoist priests of Shanglong Altar participated in their own ordination rituals, they collectively referred to the ritual knowledge acquired as “Civil and Military Formulas of the Correct Rites of the Heart of Heaven, by the Most High and the Three Principles” 太上三元天心正法文武口訣一宗 (Liu 2000, pp. 308–9).3

The name “Shanglong Altar” originates from the altar’s founding in Shanglong village, Haotou township, Rucheng county, Hunan province, located less than 5 km from Junyuan village, Chongyi county. The founder of the altar was one Zhang Sheng Erlang 張聖二郎; the suffix “lang” 郎 is obviously a ritual name.4 The first eleven generations of this altar were predominantly passed down within the Zhang clan. However, from the 12th generation onward, with no one within the clan willing to inherit the “incense fires”, the altar was transferred to a new clan to continue the succession. The 12th-generation head was Liao Chan Yilang 廖闡一郎, a relative of the Zhang clan, who transmitted to Liao Sheng Sanlang 廖盛三郎 and Guo Xian Yilang 郭顯一郎. Liao Sheng Sanlang transmitted to Liu Yuan Sanlang 劉遠三郎, who then transmitted to his son Liu Yun Wulang 劉運五郎. Liu Yun Wulang latter passed on the tradition to his maternal nephew Luo Qidong 羅棲東 (1927–2003), who became the 16th-generation master. While Liu Yun Wulang hailed from Shanglong village, Luo Qidong, a native of Junyuan village, had been raised in Haotou township and learned Taoism from his maternal grandfather and uncle. In 1947, Luo was ordained by Pan Xian Jiulang 潘顯九郎, head of Zhangxi Altar 漳溪壇 in Haotou township, taking the position “Master of the Great Banner” 大幡師 and assuming the ritual name Luo Kui Yilang 羅逵一郎. Following his ordination, Luo Qidong practiced Taoism along the Hunan–Jiangxi border and served underground for the CPC Hunan–Jiangxi guerrillas until 1949, when he returned to Junyuan following his marriage. Luo subsequently assumed the role of head of Shanglong Altar. He also inherited responsibilities for Zhangxi Altar, which had no successor after Pan Xian Jiulang. Consequently, Luo became the chief master of both Shanglong and Zhangxi altars. This event marks the shift of the altar center from Houtou in Hunan to Shangbao in Jiangxi. It is noteworthy that Zhangxi Altar possesses a copy of an ordination certificate granted to Kang Sheng Yilang 康勝一郎 by the Office of the Governor of the Heavenly Master’s residence 天師府知事廳 in the 43rd year of the Kangxi reign (1704), indicating the early influence and recognition of Zhangxi Altar by the Heavenly Master’s residence at Mount Longhu 龍虎山 in the early 18th century (Liu 2000, pp. 225–26, 263).

The chart of Lord Lao from Shanglong Altar measures approximately 90 cm in length and 60 cm in width. It is painted in black ink on paper that has yellowed and shows slight damage at the edges and in the middle. The chart was mounted and restored by Liu Jinfeng in 1999. Overall, the chart remains in good condition, with clearly recognizable image and text content. The main focus of the chart is the depiction of the body of the Most High Lord Lao, with various parts labelled in text corresponding to sacred spaces, including the Three Realms of the Three Pure Ones 三清三境, Hell of Darkness, and the names of deities including the generals of the Three Principles (Tang, Ge and Zhou 唐葛周), the Heavenly Master Zhang, and the 18 arhats. Additionally, the chart includes instructions on ritual performance, providing a comprehensive guide for practitioners.

On the right side of the chart are two rows of large characters with the following inscription: “On the 18th day of the second month of the renshen year of the Republic of China (1932), Li Da Wulang 李達五郎 copied a chart of Lord Lao. Only those possessing righteousness can pass it on, and those without do not cast eyes on it. Wish (me) the disciple the prosperity of the incense! [有義之徒方可傳,無義之徒及莫看。恭賀弟子香火興旺!]” Beneath this inscription, in three lines of small characters, is an accompanying text that reads as follows: “Li Da Wulang, (secularly) named Li Xipeng, was the alliance-witnessing master 證盟師of Luo Kui Yilang, ordinated under the great banner of Pan Xian Jiulang. His intimate transmission master 親度師 was Liu Yuan Sanlang, (secularly) named Liu Zhouchen. Liu Yuan Sanlang was the father of Liu Yun Wulang, (secularly) named Liu Shanzheng. As Li had no disciples, before his death he transmitted the Taoist methods he had learnt, along with this chart, to Luo Qidong, whose ritual name is Luo Kui Yilang. Luo is the direct nephew and favorite disciple of Liu Shanzheng. Li Xipeng resided in Xiashan corner of Miaoqian village, while Liu Zhouchen lived in Yanggu’ao corner of Miaoqian village. Li’s son, Shanzheng, lived in Jiaoyelong [corner] of Shanglong village. Qidong resides in the ‘Old house field,’ Xiaohedong corner of Junyuan village”. From the contents of the text, it can be determined that the large-print inscription remained at the time of the drawing. The note in small characters was added later by Luo Qidong, the chief master of Shanglong Altar.

Judging from the inscription, this chart of Lord Lao was copied by Li Da Wulang in 1932. The chart of Lord Lao was copied among local Taoist priests, mainly between masters and disciples, so it is likely that Li Da Wulang copied the chart from his own master, Liu Yuan Sanlang. Since Li Da Wulang had no disciples, prior to his death, he imparted all Taoist methods he had learned, along with this chart, to Luo Qidong. It is important to note that the term “no disciples” likely signifies that the master did not have any disciples deemed truly worthy of receiving teachings, i.e., “disciples with righteousness”, rather than having no disciples at all. The relationship between Li Da Wulang and Luo Qidong is multifaceted. Firstly, Li Da Wulang served as Luo’s alliance-witnessing master during his ordination through the performance of a Jiao ritual of the Great Banner in Zhangxi village in 1946 (Liu 2000, p. 226). Secondly, Li Da Wulang was the disciple of Liu Yuan Sanlang, Luo’s grandfather in both blood relationship and Taoist lineage. Essentially, Li Da Wulang was Luo’s uncle in terms of Taoist transmission. According to research by Liu Jinfeng, Luo Qidong began living with his grandfather at the age of seven or eight, and by 13, he began to accompany his grandfather in the practice of Taoism, honoring his uncle, Liu Yun Wulang (1916–1989), as his intimate transmission master (Liu 2000, p. 226). That Luo Qidong and Liu Yuan Sanlang shared an exceptionally close bond, with Liu Yuan Sanlang often directly imparting Taoist knowledge and techniques to Luo, is hardly surprising. Given that Li Da Wulang was Liu Yuan Sanlang’s disciple and fellow villager—residing in Miaoqian village,5 he would have a long history of interaction and collaboration with Luo Qidong. In one of the esoteric manuals copied by Luo, Luo mentioned that Li Da Wulang “frequently instructed (me) in many secrets of the Taoist rituals”.6 In light of these circumstances, it is understandable that Li chose to pass on Taoist methods and the chart of Lord Lao to Luo on his deathbed, given the absence of other disciples deemed suitable for such teachings.

At Shanglong Altar, two esoteric manuals are directly associated with the chart of Lord Lao. The first manual is titled the “Precise General Points of the Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao” (Jingmi Laojun daofa zongdian tu 精密老君道法總點圖). This manual spans six and a half pages, contains over 2000 characters, and bears the inscription on the front cover: “Copied by Luo Kui Yilang…in 1981”. The title page states: “This chart was copied from the Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao. It is considered invalid if not transmitted by the master to his own disciples or if copied secretly without the master’s consent. Copied by Luo Kui Yilang”. The inner pages are titled “Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao”, with a preamble preceding the main text: “The ancestral masters of high antiquity passed down the saying that: If there is no Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao, the Thunder altar is not orthodox. [上古宗師傳言:若無老君道法圖者,乃不正之雷壇也。]”. The contents of this manual can be categorized into four categories. Firstly, the manual covers basic Taoist knowledge related to the human body, such as the Eight Trigrams 八卦, Three Corpses 三屍, Five Phases 五行, Seven Holes 七孔 Nine Orifices 九竅, and other corresponding parts of the human body not explicitly indicated in the chart of Lord Lao. Secondly, it delves into the positioning of relevant deities within the human body, including details such as “The Yellow Springs are located on the upper part of the left side. King Asura, the Five Furies and Seven Furies fend off (the evil spirits) [左脅為黄泉,阿修羅王退,五七二傷退。]”. This section aligns directly with the labels in the chart of Lord Lao, with the narrative unfolding based on body parts. Thirdly, there are two notes regarding the source of the esoteric manual and guidance for Taoist learners. One note states, “This belongs to the School of the Patriarch ‘Primordial Emperor’ and Zhang Zhao Erlang. It is entrusted to those who learn ritual methods in the world to cut off the path of Yin and Yang demons, which is foolproof. [此係元皇祖師、張趙二郎流派,留與世間學法之人,斷絕陰陽邪鬼之路,萬無一失。]” The other note reads, “In the context of learning in the ritual school, paramount importance is placed on showing reverence to Heaven and Earth. Similarly, in the pursuit of cultivating perfection and practicing the Tao, the utmost respect for one’s master is deemed essential”. The preceding statement implies a connection between the ritual tradition depicted in the chart of Lord Lao and the exorcistic practices prevalent in the central region of Hunan. Furthermore, the final paragraph of the manual delves into the theories concerning Yin and Yang, the Five Phases, the qi 氣 (energy of vitality) and destiny. This is evidently related to Taoist cultivation.

The second manual, titled “Explanation of the Chart of Lord Lao and Miscellaneous Esoteric Instructions” (Laojun tujie zayong mijue 老君圖解雜用密訣), is included at the beginning of the fifth volume of the Esoteric Instructions of the Great Banner (Dafan mijue 大番密訣) and was transcribed by Luo Kui Yilang in 1996. In this manual, Luo explicitly clarifies that its content has been derived from the chart of Lord Lao, although with some exceptions, leading to varying interpretations of the same subject matter. In such instances, guidance provided should be based on the chart itself. Compared to the preceding manual, this text places a stronger emphasis on the practical utilization of the chart of Lord Lao within ritual practices, particularly highlighting its significance in exorcism. The contents of this manual are structured not according to the specific body parts but rather based on the ritual framework, grouping together the relevant deities associated with different bodily regions. These deities are the same frequently invoked by Luo in conjunction with the chart of Lord Lao during his rituals. It is noteworthy that this manual contains several expressions with dialectal nuances, indicating that the chart of Lord Lao and its associated practices bear a distinct local flavor.

3. Structure and Content of the Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao

This section will provide a detailed description and analysis of the structure and content of the Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao. The chart of Lord Lao can be broadly categorized into six regions: the head (Figure 2), the neck, the torso and upper parts of the limbs, the forearms and hands, the bladder, and the lower legs and feet.

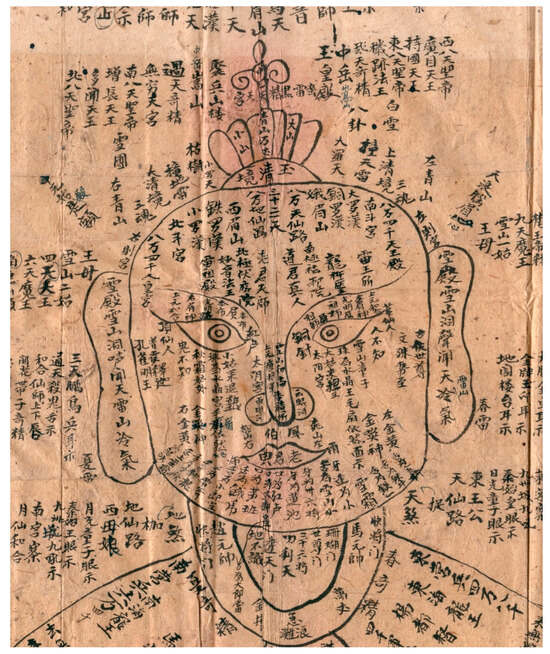

Figure 2.

Head Region from the chart of Lord Lao.

The celestial realm depicted in the overhead space is dominated by the heavens, with several sacred mountains, including Mount Sumeru of the Roofless Heavenly Palace 無頂天宮須彌山, the Heaven of the Numinous Vulture 靈鷲天, the Tuṣita Heaven 兜率天, the Thirty-three Heavens, the Jade Emperor’s Palace 玉皇殿, Heaven of the grand net 大羅天, Heaven of the little net 小羅天, Realms of the Three Pure Ones 三清, Withered Tree 枯樹, Central Sacred Peak 中嶽嵩山, Mount Emei 峨眉山, and Mount Penglai 蓬萊山. Deities include Guanyin of the Southern Heaven 南天觀音, arhats of the Western Heaven, ancestral master True Warrior 真武祖師, Ritual Lord of Mount Mao 茆山法主, Ancestral Master of the Snow Mountain 雪山祖師, King Pangu 盤古王, Dharma King of Filthy Tracks 穢跡法王 (i.e., Ucchusma), Holy Emperors of the Eastern Eight Heavens 東八天聖帝, Holy Emperors of the Southern Eight Heavens, Holy Emperors of the Western Eight Heavens, Holy Emperors of the Northern Eight Heavens, the Black Spirit of the Barbarian Thunder 蠻雷黑精, Four Heavenly Kings including Heavenly King Dhritarashtra 持國天王 of the East, Heavenly King Virudhaka 增長天王 of the South, Heavenly King Virupaksa 廣目天王 of the West and Heavenly King Vaisravana 多聞天王 of the North.

The forehead-to-brow portion likewise relates primarily to the heavenly realm. The forehead is labeled as the Hall of Primordial Origin 元始殿, and to the left and right we find the Palace of the Southern Dipper 南斗宮, the Palace of the Northern Dipper 北斗宮, the Palace of the Heavenly King 天王殿, and the Palace of the Emperor of Mankind 人皇宮. Three souls are located at the corners of the head. The Celestial Wave Brain 天浪腦 is located at the point between the eyebrows, moving from left and right are the Exorcism Court of the Southern Pole 南極祛邪院, the Court for Quelling Demons of the Northern Pole 北極伏魔院, the Office of the Thunder King雷王所, the Thunder Patriarch’s Hall 雷祖殿, as well as the deities including the Realized Person Lord of the Tao 道君真人, the Heavenly Master Lord Lao 老君天師, the Healer King Nâgârjuna 龍樹醫王, the Dharma King Mañju-ghosa 妙音法王, the Queen Mother 王母, the First Aunt of the Snow Mountain 雪山一姑, the Second Aunt of the Snow Mountain 雪山二姑, the Demon King of Nine Heavens 九天魔王, the Four Great Heavenly Kings 四大天王, the Buddhist King Śakra-devānām-indra 梵王帝釋, and the Demon King of Six Heavens 六天魔王. The back of the head is the Snow Mountain of the Upper Cave 上洞雪山. The left eyebrow is the Palace of the Boluo Heaven 波羅天宮. The right eyebrow is the Heavenly Palace of Darkness 黑暗天宮. Under the left eyebrow is the Hall of the Ancestral Masters 祖師殿 and the Hall of Light 光明殿. Under the right eyebrow is the Hall of the Proper Masters 本師殿 and the Path of Light 光明路. The two eyes represent the gods of harmonization of the superior principle 上元和合, the Palace of Great Yang 太陽宮 and the Palace of Great Yin 太陰宮, the Sunlight Lad 日光童子 and the Moonlight Lad 月光童子. The eyeballs are the Crystal King 水晶王 and the Crystal Palace 水晶宮. On the left cheek there are Manjushri 文殊 and Mahāsthāmaprāpta 勢至, Samantabhadra 普賢 and Shakyamuni 釋迦; on the right cheek there are the Ancient Buddha Honored by the World 古佛世尊 and Mahamayuri 孔雀明王. The left and right ears represent both the Snow Palace 雪殿 and Snow Mountain Cave 雪山洞. Nest to the left ear is Spring Thunder 春雷, and, next to the right ear, Summer Thunder 夏雷. The nose is the Palace of Pacifying Plague 和瘟宮, the Palace of the Treasure King 寶王宮, Mount Luofu 羅浮山, the Heavenly Pillar Tree 天柱樹, General Tang of the Superior Principle 上元唐將軍, Monk of the Snowy Mountain 雪山和尚, Upper Cinnabar Field 上丹田, and the Hall of Accumulating Incense 香積所. The left and right nostrils are the River of Cloudy Eyes 雲眼河 and the River of Rainy Eyes 雨眼河. The ears are the Earth Pavilion 地閣樓臺, the Roc bird of the Three Heavens 三天鵬鳥, the Gold Plaque and Jade Seal 金牌玉印, the Golden Roc Bird 大鵬金鳥, and the Great Yellow Palace 大黄宮. The skin of the lips is the Earl of Winds 風伯, and the corners of the lips are the Master of Rain 雨師. Mouth for the Palace of Lord Lao 老君殿, Red Furnace 紅爐, Dalang who takes responsibility 大郎當, Yellow-marking 黄斑, the Commissioner who Makes Peace with the Deities 和神使者, the Master who Encourages Virtuous Deeds 勸善大師, lips for the Immortal Masters of Harmonization 和合仙師, the Commissioner of the Three Heavens who Probes for and Reports News 三天報探使者, teeth for the Lotus Pond 蓮池, the Thirty-Six Generals 三十六將, the Thirty-Six Cavern-Heavens 三十六洞天, and the Small Snow Frost 小雪霜. The Patrol Checkpoint of the Five Camps 五營羅關 is represented by the combined teeth. The tongue represents the Small Snow Mountain 小雪山, Iron Cow 鐵牛, Golden Bridge 金橋, Hungry Tiger 餓虎, Xiaolang who takes responsibility 小郎當, Thunder Axe 雷斧, Lone Dragon 獨龍, Golden Loach 金鰍, the Bridge to Ferry the Soldiers 度兵橋, the Soldiers who Swim in the Ocean to Expel Geese 遊海祛鵝兵, the Iron Barrier Extending to the Sky 連天鐵障, and so on. In addition, the Nine Orifices are the Castles of the Nine Regions 九州城.

Around the neck region, at the throat are the Sharp Wave Shore 急浪灘, the Golden Well of Ten Thousand Fathoms 萬丈金井, the Fire Pit of Ten Thousand Fathoms 萬丈火坑, the Great Commissioner who Moves Soldiers 行兵大使, and the Cave of Concealing Soldiers 藏兵洞, and to the left and right are Marshal Ma 馬元帥, Marshal Zhao 趙元帥, the Deity for Capturing Heavenly Evil Spirits 捉天煞, and the Deity for Shackling Terrestrial Evil Spirits 枷地煞.

The region of the torso and upper limbs is essentially centered on the torso, with the arms and legs corresponding to the four directions, and is depicted as a ring-shaped structure with a combination of upper and lower layers. The spaces corresponding to the four directions are the Division of the Eastern Sacred Peak Mount Tai 東嶽泰山司, Division of the Southern Sacred Peak Mount Heng 南嶽衡山司, Division of the Western Sacred Peak Mount Hua 西嶽華山司, Division of the Northern Sacred Peak of Mount Heng 北嶽恆山司; Eastern Buddhist Kingdom 東仸國, Jambu Heaven 浮提天, the Effective Station of Ten Thousand Miles 萬里效所, and the Yeni Realm 耶尼界. The deities corresponding to the Five Directions are the Dragon Kings of the Five Seas 五海龍王, the Troops and Horses of the Five Camps 五營兵馬, and the Troops and Horses of the Five Directions 五方兵馬. The Deities Corresponding to the Four Directions are Cyan-marking Yilang 青斑一郎, Red-marking Erlang 赤斑二郎, White-marking Sanlang 白斑三郎, Black-marking Silang 黑斑四郎; and the Thunders of the Four Seasons. Additional important deities include the Heavenly Master Zhang and Governor Yang 楊都督 on the left shoulder; the Heavenly Master Li and General Ma 馬將軍 on the right shoulder; Realized Person Wu 吳真人 and Realized Person Xu 許真人, the 24 Jinwu generals 金吾將軍 on the left side, the old immortal master Huang 黄老仙師 and the 24 Yinwu Generals 銀吾將軍 on the right side; and the immortal master Ye Jing 葉靖仙師 on the back of the waist. The left rib shows 24 qi 炁, Kings of the Twelve Years 十二年王 and Ancestral Masters of the Twelve Departments 一十二部祖師. The right rib shows 72 hou 候 (phenological phenomenon), Generals of the Twelve Months 十二月將, and Proper Masters of the Twenty Departments 二十部本師. Among the flank hair are 4000 military prefectures 軍州, 7000 grass counties 草縣, and 80,000 soldiers. The left elbow is labelled the character “fetter” 縛 and the right elbow “torture” 拷. The back of the left shoulder shows the Thirty-Six Celestial Generals 三十六員天將, and the back of the right shoulder shows Seventy-Two Assistant Generals 七十二員副將. The backbone of the spine shows the King of the Battle who Communicates with Heaven 通天通地戰王, the Yellow Dragon 黄龍 and the Mori Heavenly Palace of the Eighteen Arhats 十八羅漢莫日天宮. The back indicates the Heaven-Facing General who Beheads Ghosts 朝天斬鬼將軍 and the General Black-Killer of the Temple of the Heavenly Palace 天府廟黑殺將軍, while the backbone indicates the Castle of the Iron Patrol 鐵羅城, the Castle of the Stone Patrol 石羅城, the Castle of the Silver Patrol 銀羅城, and the Castle of Earth Patrol 土羅城. The garments show the God of Front Covering and Back Covering 前遮後掩神, and the God of Front Lighting and Rear Darkness 前光後暗神. The five viscera are the soldiers of the Wooden Castle 木城, Metal Castle 金城, Fire Castle 火城, Water Castle 水城 and Earth Castle 土城. Among them, the soldiers of the Earth Castle can also be shown in the umbilicus. Under the umbilicus are seven po souls 七魄. In addition, at the left breast, there are General Cyan-Dragon 青龍, the Station of the Eastern Mountain 東山所, the Lake of the Eastern Ocean 東洋湖, and Realized Person Li 李真人, while at the right breast, there are General White-Tiger 白虎, the Station of southern mountain 南山所, the Lake of the Southern Ocean 南洋湖, and Realized Person Zhao 趙真人.

A large gourd is painted in the median of the breasts down to the abdomen. On the upper half of the gourd are General Ge of the Median Principle 中元葛將軍, Copper Mituo 銅彌陀, Iron Mituo 鐵彌陀, Blood Lake 血湖, Floating Sands 浮沙, Qijing of the Median Cave 中洞奇精, Total Fire 總火, Six Bing 六丙, One-Legged Dragon 獨腳龍, One-Legged Crane 獨腳鶴, Nezha 哪吒, Iron Ox 鐵牛, the Station of the Three Officials 三官所, and the Station of the Three Departments 三省所. The upper half of the gourd is flanked by the stellar lords 星君 of the 24 qi and 72 hou. The lower part of the gourd and the position of the stomach correspond to the center of the text “Gourd Sinking to the Bottom of the Ocean 葫蘆沉海底”, for the Hell of Darkness 黑暗地獄, there are the Four Marshals Pang 龐, Liu 劉, Gou 苟, and Bi 畢. The stomach is also the Camp of Tying Hands Behind One’s Back 五花大營 and Chang’an Castle 長安大城. Below the gourd is the Department of Subcelestial City Gods 天下城隍司 and the Earth God for Burning Paper Money 化財土地, among other deities.

The region of the forearms and hands is dominated by the deities who catch and exorcise demons, as well as by exorcistic spaces. Among them, the left forearm is the Copper barrier extending to the sky 連天銅障, and the right forearm is the Iron Barrier Extending to the Sky 連天鐵障, and is labelled with the Demon of Drought 旱魃神, the Thunder of Earth Restoration 復地雷, and the Office of Master Kuang Fu 匡阜所. The fingers represent the Generals who Capture (Demons) Alive 生擒活捉將軍, and the Demon Kings of the Ten Paths 十道魔王. The left palm is the Divine king who Pushes Heaven 推天神王, the five fingers are the Thunder Shoveling the Heaven 鏟天雷, and the Generals of the Five Paths who Roam through the Heavens 遊天五道將軍, the thumb is the Demon of Drought, the forefinger is the Station of Imprisoning Plague qi/demons 收瘟所, the ring finger is the Earth God who Guides Soldiers 引兵土地, and the little finger is the Great Commissioner who Raises Troops 招兵大使. The right hand is the Marshal who Guides Soldiers 引兵元帥, the five fingers are the 500 Soldiers of Strong Fish 強魚兵, and the little finger is the Vanguard of Little King 小王先鋒.

Next is the region of the bladder. In the median of the two legs, there are King Changsha 長沙王, the King who supports the Battle Formation 扶陣王, General Liu 柳將軍, Qijing of the Lower Cave 下洞奇精, the soldiers of Golden Loach and Poisonous Dragon 金鰍毒龍兵, the Soldiers of Golden Loach and Iron Ox 金鰍鐵牛兵, General Zhou 周將軍, Epidemic Father 瘟公, Epidemic Mother 瘟母, Zhang Wulang 張五郎, Nine Dragons and Two Tigers 九龍二虎, the Bewitching Immortal Master of the Lower Cave 下洞迷魂仙師, and other deities.

As for the region of the lower legs and feet, at the left and right calves, there are 300 military prefectures and 7000 grass towns, as well as General Zhou of the inferior principle 下元周將軍, the Official residence of sacred peak 嶽府, the City God 城隍, the Temple King 廟王, and the Earth God 社令. At the left foot, there is the Destiny director of the proper household 本家司命. At the heel of the left foot is the Village of Escorting Ghosts 押鬼村, and at the heel of the right foot is the Office for Clamping Ghosts 夾鬼所. The left toes are the Claws of Golden Refined Radiance 金精光爪, and the right toes are the Claws of Silver Refined Radiance 銀精光爪. The soles of the feet are the General who Crosses the Sky and Earth 過天過地將軍, and there are also important exorcistic spaces, such as the Pit of Stinking Ghosts 臭鬼坑, the Well for Burying Ghosts 埋鬼井, the Hell of Darkness 黑暗地獄, and the Office of the Demon of Drought 旱魃所.

With regard to ritual instructions inscribed on the chart of Lord Lao, there are esoteric instructions for summoning the Ancestral Masters 祖師, the Proper Masters 本師, the Three Masters of the Canon, and Registry and Transmission 經籍度三師 under the palm of the right hand; instructions for breaking plague demons and evil spirits on both sides of the thighs; and instructions for taming and driving out evil spirits on both sides of the knees. Among these, the instructions for breaking plague demons and evil spirits read as follows: “Firstly, cut off the heavenly plague demons in this place (pinching the knuckle corresponding to hai 亥 or zi 子). Secondly, extinguish the terrestrial plague demons in this place (chou 丑). Thirdly, eliminate the human plague demons (si 巳 or yin 寅). Fourthly, transform the Ghost Path into the River (yin 寅or mao 卯). [The ghosts] will dare not cross even if there are boats (si 巳). [The ghosts] dare not walk even when there are paths (shen 申). Thousands of evil spirits will be henceforth cut off, and ten thousand ghosts henceforth destroyed. Fifthly, cut off the ‘five plague qi/demons’ 五瘟 and the 24 qi (chen 辰). Sixthly, remove the ghosts of the Six Caves of Fengdu 酆都六洞鬼 (si 巳). Seventhly, exorcise the Kings of the Seventy-two hou (wu 午). Eighthly, cut off the dark clouds of the eight heavens (wu 午). Ninthly, eliminate the Earth Gods of the Nine Regions (shen 申). Tenthly, remove the demons of terrestrial grievances (you 酉). Eleventhly, cut off the grievance demons and evil spirits (xu 戌). Twelfthly, eliminate the devils to perish (hai 亥)”.

In summary, the body of Lord Lao presents a hierarchical system of cosmic spaces, the deities inhabiting these spaces, and the corresponding Taoist ritual methods. There are three main aspects worth noting. Firstly, in terms of overall structure and components, the chart of Lord Lao is predominantly Taoist, with some Buddhist elements. For example, the core of the region above the top of the head is labelled “Mount Sumeru of the Roofless Heavenly Palace”. The “Roofless Heavenly Palace” is likely that mentioned in Marvelous Scripture of the Karmic Retribution of the Merit of the Ten Epithets from the Dongxuan Lingbao Canon (Taishang dongxuan lingbao shihao gongde yinyuan miaojing 太上洞玄靈寶十號功德因緣妙經), a Taoist text of the Tang Dynasty. Here, the palace is described as being “above the Heaven of Free Wandering and Grand Network, named Supreme Superior [逍遙大羅之上, 名無上之上]”, with the deity residing there being the High Emperor 高皇 (DZ337, Daozang 6: 130). Regarding Mount Sumeru, the Song text Cloudy Bookcase with Seven Labels (Yunji Qiqian 雲笈七籖) cites the Chart of the Three Realms (Sanjie tu 三界圖), which reads “At the center of all the heavens, there is Mount Kunlun, also known as Mount Sumeru. The mountain is high and broad, surrounded by the Four Directions, with the sun and the moon circling around it, creating day and night. [其天中心皆有崑崙山,又名須彌山也。其山高闊,傍障四方,日月繞山,互為晝夜。]” (DZ1032, juan 21, Daozang 22: 163). Heaven of the Numinous Vulture and the Tuṣita Heaven on the left and right sides of Mount Sumeru, as well as Guanyin of the Southern Heaven and the Arhat of the Western Heaven, clearly belong to Buddhist tradition. Additionally, the Four Heavenly Kings sitting overhead, as well as Manjushri and Mahāsthāmaprāpta, Samantabhadra, Shakyamuni, the Ancient Buddha Honored by the World and Mahamayuri on the cheeks, are also distinctly associated with Buddhism.

Secondly, a significant portion of the chart’s content is rooted in classical Taoism. Apart from the Roofless Heavenly Palace and Three Realms of the Three Pure Ones, there is the Celestial Wave Brain situated on the point between the eyebrows, or more simply the Celestial Brain 天腦 or Niwan 泥丸 (Muddy Pellet). According to the early 13th-century text Great Rites of the Book of Universal Salvation from the Lingbao Canon (Lingbao wuliang duren shangjing dafa 靈寶無量度人上經大法), “[The site] between the brows and three inches straight in is named the Palace of Muddy Pellet, where the Supreme Emperor of Primordial Origin 元始上帝 resides” (DZ219, juan 26, Daozang 3: 758). This clarifies the notation marked in the chart of Lord Lao that “The Palace of Primordial Origin is located on the forehead”, as the forehead is directly above the point between the eyebrows. The Realized Person Lord of the Tao and the Heavenly Master Lord Lao depicted on the forehead are likely references to the Most High Lord of the Tao 太上道君 and the Most High Lord Lao 太上老君 mentioned in the Great Rites of the Book of Universal Salvation from the Lingbao Canon just cited. According to this text, “[The place] between the brows and four inches straight in is named the Palace of the Moving Pearl 流珠宮, where the Most High Lord of the Tao resides”; “[The place] between the brows and two inches straight in is named the Palace of Cavern Chamber 洞房宮, where the Most High Huang Lao 太上黄老 (i.e., the Most High Lord Lao) of the center resides” (DZ219, juan 26, Daozang 3: 758–759). It is also noteworthy that the “withered tree” positioned on the right side of Lord Lao’s head likely symbolized the visualization used during Taoist rituals called “transformation into a divine body” 變神/變身. Since the Song and Yuan dynasties, the masters of the Correct Rites of the Heart of Heaven and other schools frequently visualized themselves as a withered tree. According to the Correct Rites of the Heart of Heaven of the Shangqing Tradition (Shangqing tianxin zhengfa 上清天心正法), compiled by Deng Yougong 鄧有功 of the Southern Song Dynasty, during the transformation of divine bodies, the master would visualize himself as a withered tree and guide the fire of the heart towards the posterior fontanelle. Subsequently, the master then envisions the fire consuming his body until only one genuine qi 炁 (i.e., 氣, energy of vitality) remains, which gradually congeals into a fetus. At this point, the master can visualize that his own body has transformed into the Heavenly Master, Marshal Tianpeng 天蓬 or the True Warrior (DZ566, juan 2, Daozang 10: 611). The fire of the heart burns to the posterior fontanelle, indicating that the withered tree is located at the posterior fontanelle. Correspondingly, the “withered tree” is marked next to the top of the head in the chart of Lord Lao. According to a rite of exorcising plague demons included in the Taoist Methods United in Principle (Daofa huiyuan 道法會元)—the 15th century compendium of late Tang through early Ming ritual texts, the master can visualize his body as a thousand-year-old or ten thousand-year-old withered tree, five fires burning his body into ashes, leaving only two points, which then transform into a fetus and eventually evolve into the Realized Person of Primordial Destiny 元命真人 (DZ1220, juan 232, Daozang 30: 451). Furthermore, the Eastern Buddhist Kingdom 東仸國 marked on the left shoulder (representing the east), the Futi Heaven 浮提天 on the right shoulder (south), and the Yeni Realm 耶尼界 on the left thigh (west) likely correspond to “the Fuyudai Heaven of the East” 東弗于岱天, “the Xiqu Yeni Heaven of the West” 西瞿耶尼天, and “the Yanfuti Heaven of the South” 南閻浮提天, respectively, mentioned in the Taoist Methods United in Principle (DZ1220, juan 228, 240, Daozang 30: 424, 484).

Thirdly, among the overhead deities in the chart, in addition to the aforementioned Buddhist deities, there are also significant deities associated with regional Taoist traditions such as the True Warrior, the Ritual Lord of Mount Mao, the Dharma King of Filthy Tracks, and the Black Spirit of the Barbarian Thunder. These deities are positioned above the Three Realms of the Three Pure Ones, indicating the significant influence of local Taoist traditions within the framework of the chart. The content below the head of the chart also demonstrates a strong connection to Taoist exorcistic traditions. For instance, the deity for capturing heavenly evil spirits and responsible for shackling the terrestrial malevolent forces at the neck, along with the characters “fetter” 縛 and “torture” 拷 at the elbows, collectively represent a group of exorcistic deities mentioned in the 1996 Manual for Sending Generals and Building Ritual Arena (Chaijiang zaotan yizong 差將造壇一宗) of Shanglong Altar: the Generals of Capturing, Fettering, Shackling, and Torturing. Additionally, Marshal Ma and Marshal Zhao on the neck, as well as Generals Pang, Liu, Gou, and Bi in the lower abdominal region, are described in the 1982 Manual for Activating the Masters to Consecrate the Water (Qishi zaoshui ke 起師造水科) of Shanglong Altar, where they are identified as gods associated with the Eight Thunder Departments. To a certain extent, this demonstrates the connection between the chart of Lord Lao and exorcistic traditions, such as the Correct Rites of the Heart of Heaven and the School of Pure Tenuity 清微, known for their thunder rites since the Song and Yuan dynasties. Furthermore, deities such as the Dharma King of Filthy Trace, the Healer King Nâgârjuna, Governor Yang, General Ma, the generals of the Three Principles, the combination of the Heavenly Master Zhang and the Heavenly Master Li, King Asura, King Changsha, General Liu, Zhang Wulang, and the spaces such as the 300 Military Prefectures can mostly be correlated with the contents of the ritual texts at Shanglong Altar. This observation also sheds light on the connections between the chart of Lord Lao and the schools of Mount Lü and Mount Mei 梅山, with a particular emphasis on the school of Mount Lü. Additionally, entities such as the Plague Palace, Plague Father, Plague Mother, the Office of Master Kuang Fu, and the Master who Encourages Virtuous Deeds are likely associated with the plague-exorcising rituals prevalent in southern Jiangxi.

4. The Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao and the Space of Ritual Arena

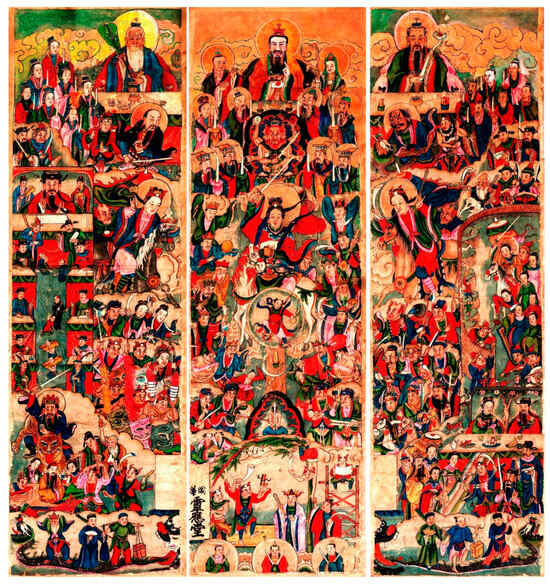

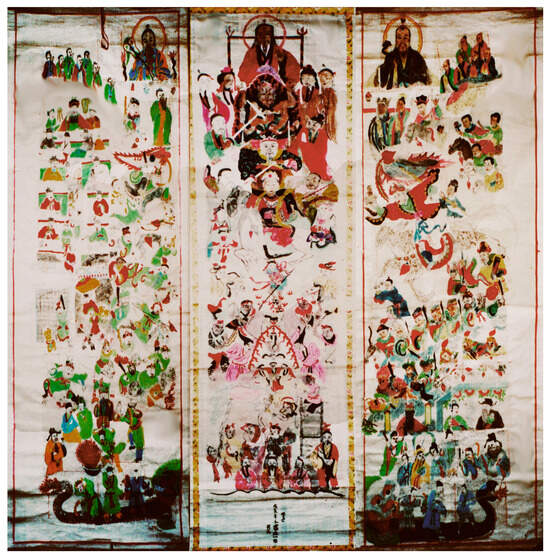

Liu Jinfeng has previously highlighted that, in terms of the associated deities, the regions of Lord Lao’s body can be categorized as follows: the overhead region represents the Realm of Worthies 尊境, the head and face region symbolizes the Realm of Saints 聖境, while the upper and lower body regions, respectively, signify the Realm of Immortals 仙境, the Realm of Humans 人境, and the Realm of Demons 鬼境 (Liu 2024, p. 8). This structure, in fact, reflects the relationship between the body and the cosmos. Moreover, this structural organization bears a resemblance to that found in Taoist ritual paintings and the spatial layout of the ritual arena. Given that the chart of Lord Lao was primarily utilized in the context of exorcism at Shanglong Altar, with its exorcistic methods rooted in the tradition of Mount Lü, the author aims to elucidate this connection by drawing parallels with the ritual painting of the Three Altars 三壇 (Figure 3) and the ritual arena of Lingying Altar 靈應堂 (Hall of Efficacious Response) in western Fujian Province. The exorcistic methods of Lingying Altar also align with the tradition of Mount Lü centered around the worship of the Three Ladies—Chen, Lin and Li 陳林李三夫人.7 Moreover, in the exorcism arena of Shanglong Altar, a set of ritual paintings called “middle altars of military rituals” (wu zhongtai 武中臺) is hung (Liu 2000, pp. 252–53; Figure 4), whose structure and content are basically the same as those of the three-altar painting of Lingying Altar (Wu 2019, pp. 129–35, 1698–700), in which the arrangement of deities mirrors that within the chart of Lord Lao, displaying a vertical stratification from high to low. The Three Pure Ones positioned at the pinnacle correspond to the Realm of Worthies contained in the chart of Lord Lao, while slightly below, the Six Deities of the Southern Dipper and Seven Deities of the Northern Dipper align with the Realm of saints. Further down, deities such as the Dharma King of Filthy Tracks, the True Warrior, the Healer King Nâgârjuna, and the Three Ladies correspond to the Realm of Immortals. Subsequently, a multitude of ritual masters performing rituals can be associated with the Realm of Humans, and the depiction of demons being refined by fire corresponds to the Realm of Demons.

Figure 3.

Hanging scrolls of the three-altar Painting, Lingying Altar.

Figure 4.

Hanging scrolls of the military-altar Painting, Shanglong Altar (painted by Luo Kui Yilang in 1988, photo by Liu Jinfeng).

According to Master Luo Qidong, the Realm of Humans in the chart of Lord Lao mainly refers to the space occupied by the ritual masters and their divine troops, such as the Troops and Horses of the Five Directions.8 The human realm is presented in more detail in the three-altar painting of Lingying Altar, where three categories of individuals are depicted: those journeying to acquire ritual knowledge and their followers, ritual masters, and faithful believers. Among these groups, the ritual masters constitute the majority and are all engaged in performing various rituals, such as the Hundred Deliverances on the Sword Mountain 刀山百解, the Turning of the Bamboo with a Banner 和旛轉竹, the Supplication for an Heir and the Healing of Emperor Song Renzong 宋仁宗, among others. In essence, when referencing the structure of the chart of Lord Lao, the human realm is primarily represented by the presence of ritual masters, with space for ritual performances being the ritual arena. Therefore, whether examining the chart of Lord Lao or the three-altar painting, the human realm is symbolized by a ritual arena where the ritual masters hold sway. Descriptions of the chart of Lord Lao indicate that this region “is essentially centered on the torso …, depicted as a ring-shaped structure with a combination of upper and lower layers” (Figure 5). When compared with the three-altar painting, it becomes apparent that this ring-shaped structure with its upper and lower layers corresponds to the ritual arena controlled by the ritual masters. While the ritual master remains invisible in the chart of Lord Lao, he is believed to transform into Lord Lao himself during the performance of rituals. Thus, both the chart of Lord Lao and the three-altar painting serve as a ritual arena awaiting activation, with the ritual master who conducts the rituals within this arena serving as the activator of the sacred space.

Figure 5.

The median region of the chart of Lord Lao of Shanglong Altar.

The ritual arena serves as a crucial element in understanding why different spatial sections of the chart often intersect, particularly between the realms of immortals, humans and demons. Within this context, deities associated with the Immortal Realm are primarily those masters are obliged to invoke during rituals—referred to as “Immortal Deities” 仙神 in the context of Lingying Altar. Masters operating within the human realm were required to summon the deities of the immortal realm in order to preside over the alliance of or partake in rituals aimed at expelling the malevolent spirits of the demon realm. The spatial layout of the chart of Lord Lao and the three-altar painting typically follows a vertical layering from top to bottom, akin to the horizontal layering observed in the physical layout of the ritual arena, which is typically arranged horizontally from the innermost to the outermost regions. In the exorcistic ritual arena of Lingying Altar in western Fujian, the three-altar painting is positioned in the innermost section, with the altar table placed in front, housing the painted tablets of the Most High Lord Lao, the Three Ladies, and Marshal Yin Jiao 殷郊, along with the spirit tablet of the ancestral masters. The altar table serves as the central space where the masters conducted rituals. The ritual for reconciling with and dispelling evil spirits 和神解煞 took place on the floor in front of the altar table. A straw-man made of thatch 茅人, adorned with depictions of a white tiger and five ghosts on his body, was placed on the floor. The spirit tablet of Marshal Yin Jiao was positioned on a stool or a small table next to the straw-man, facing inward towards the three-altar painting and the altar table. The master would squat on the floor and face outwards towards Marshal Yin Jiao and the straw-man, to perform the ritual of reconciling with evil spirits. The ritual culminated in sending the straw-man out the door to a three-way intersection or a stream for incineration (Wu 2019, pp. 98–99, 114–18). Evidently, the space in the three-altar painting and the ritual arena exhibits an isomorphic and overlapping nature. The convergence of the realms of immortals, humans and demons was apparent in both the overall spatial structure and in the space where specific rituals were being conducted. For instance, the ritual space designated for reconciling with and dispelling evil spirits pertained to the realm of demons within the broader ritual arena. However, this space encompassed elements such as Yin Jiao as an immortal deity, the priests and believers as humans, and the straw-man made of thatch as a representation of demons.

In the chart of Lord Lao, a space analogous to the ritual for reconciling with and dispelling evil spirits at Lingying Altar can be identified. This site is located in the lower part of the gourd at Lord Lao’s belly, known as “the gourd sinking to the bottom of the sea”, which represents the Hell of Darkness. Within this realm, four gods—Pang, Liu, Gou, and Bi—would be invoked by the masters. Pang and Liu are referenced in the Taoist Methods United in Principle 154 as “Generals of Heavenly Souls of the Cave at the Eight Trigrams, Pang Ling 八卦洞神天魂正將龐靈” and “Assistant General of Terrestrial Souls of the Cave of the Eight Trigrams, Liu Tong 八卦洞神地魄副將劉通” respectively. An exorcistic incantation in the Taoist Methods United in Principle 196 mentions “the Two Marshals Pang and Liu” (DZ1220, juan 154, Daozang 29: 803; juan 196, Daozang 30: 240). Regarding Gou and Bi, the Taoist Methods United in Principle 34 describes Pang and Liu as “the two thunder lords Gou and Bi of the Divine Fire of Yin and Yang of Supreme Purity” 上清神烈陰陽苟畢二雷君. Additionally, the Taoist Methods United in Principle 41 indicates that Gou and Bi would sometimes be accompanied by “the Heavenly Lord Zhang of the Velley of raising sun, great god who executes the command” 行令大神暘谷張天君, a common occurrence in the ritual texts of Pure Tenuity. Furthermore, the Taoist Methods United in Principle 55 provides an account of the two thunder lords searching and apprehending demons (DZ1220, juan 34, Daozang 28: 874; juan 41, 55, Daozang 30: 26, 130).

As for the Hell of Darkness, as outlined in the “Rite of imprisoning evil masters” 收邪巫法 from the Taoist Methods United in Principle 240, “Thunder rites of Swing Sleeves in the Meadow Field of Six Yin Presided Over by the Marshal of the Mysterious Altar of Orthodox Unity” 正一玄壇元帥六陰草野舞袖雷法:

The master initiates the rite by first summoning the Marshal (of the Mysterious Altar) to command (spirit soldiers) to apprehend evil masters and soldiers, escorting them to the altar and imprisoning them. The master constructs a prison of well by reciting: “I am the Army Office Lord of the Six Countries, I am the Army Office King of the Six Countries. The Heavenly Master acknowledges me as his master, the Terrestrial Master honors me as Ancestral Master. What order doesn’t work? What god cannot be driven away? … May the divine generals shackle the evil (masters and soldiers) and imprison them in the Hell of Darkness. Unable to move!” Following the incantation, the master visualizes the capture of the evil spirits and utilizes hand mudras to confine them within the prison, rendering them immobile. The mudra of four vertical and five horizontal lines, as well as the mudra of Mount Tai, is employed to seal the prison. Subsequently, the master takes the evil qi, spurts a mouthful of (consecrated) water towards it, and recites the Incantation of the Subsequent Imperial Rescript on Administration: “An Mou Mou! The gods bow; the demons convert themselves to the Orthodox (Way). Those who dare refuse to obey are rapidly turned into dust. Immediately follow the statutes and command of the Original Forces of Jade Emperor on High!”凡行用,先召元帥,指揮收捉邪巫邪兵赴壇,押入獄中,作一井獄。念云:「吾是六國都司主,吾為六國都司王。天師拜吾為師父,地師拜吾為師祖,何令不行,何神不驅……神將枷邪入禁黑暗地獄,無動無作。」呪畢,想收到,以訣押邪盡入獄中,並無動作,加四縱五横及太山訣封壓。取煞炁以水一噀,即念後敕轄呪曰:「唵吽吽!眾神稽首,邪魔歸正。敢有不伏,化作微塵。急急如玉皇上帝元降律令敕煞攝。」(DZ1220, juan 240, Daozang 30: 485)

The concept of the Dark Hell serves as a space of containment for malevolent masters, evil soldiers and demons, bound by divine generals. In the chart of Lord Lao, the Dark Hell also functions as a location for detaining evil spirits, restrained by the four marshals Pang, Liu, Gou and Bi. It is worth noting that in the ritual practices of Shanglong Altar, the place where evil spirits and demons are held captive is referred to as the “Yangping Prison” 陽平牢獄 or “Heavenly and Terrestrial Prison” 天牢地獄. The four deities tasked with apprehending and imprisoning evil spirits in this context are the Queen Mother and the generals of the Three Principles (Luo 1998, p. 390; Liu 2000, pp. 275–76), although Pang, Liu, Gou and Bi are also mentioned in ritual texts at the altar. However, references to the Hell of Darkness can be found in the traditions of other Taoist altars in southern Jiangxi. For instance, the 1984 manuscript of the Esoteric Manual of the Talismans and Water of the Earth Ministry (Disi fushui miben 地司符水秘本), an esoteric manual of the Lingzhen Miaoying Thunder Altar 靈真妙應雷壇 (Thunder Altar of Efficacious Perfection and Marvelous Response) in Dayu county, mentions that “all evil qi are imprisoned in the Dark Prison of Golden Well 金井黑獄 to be eliminated”. Similar to the rites of Marshal Zhao in the Taoist Methods United in Principle 240, the master is instructed to utilize a symbol of four horizontal and five vertical lines, as well as the mudra of Mount Tai, so as to seal the prison.9 The “Dark Prison” of Miaoying Altar evidently corresponds to the Hell of Darkness mentioned in the chart of Lord Lao and Taoist Methods United in Principle.

It is also noteworthy that the gourd depicted upon Lord Lao’s belly shares similarities with Nezha of the median altar and the space designated for refining demons in the three-altar painting. In the upper section of the gourd within the chart of Lord Lao, we find General Ge of the median principle and Qijing of the median cave, mirroring the location of Nezha in the three-altar painting. Furthermore, Nezha has also been positioned in the upper part of the gourd within the chart of Lord Lao. While there may not be demons specifically present in the Dark Hell below the gourd in the chart of Lord Lao, it is understood that the Dark Hell serves as a containment space for evil spirits, akin to the cave and furnace-like space in the three-altar painting, where demons undergo refinement through fire. Additionally, evil spirits confined in the Dark Hell are bound by Pang, Liu, Gou and Bi, mirror the presence of four deities responsible for binding evil spirits within the demon-refining space depicted in the three-altar painting.

5. The Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao and Ritual Practices

The least understood aspect of the relationship between the chart of Lord Lao and ritual practices lies in how Taoist priests executed specific physical movements, essentially controlling their bodies in accordance with the chart of Lord Lao during ritual performances. Thanks to Liu Jinfeng’s intensive investigations, we have gained a better understanding of this intricate process. Let us consider the ritual for imprisoning plague demons and evil spirits 收瘟收煞 as an illustrative example:

Regarding “transforms himself into a divine body”, it refers to the transformations of the ritual master into the true body of Patriarch Pu’an, Guanyin of the Southern Sea 南海觀音, Ancestral Masters, Proper Masters, or Masters of Oral Transmission 口教師公, etc. (Liu 2000, pp. 274–75) However, regardless of which deity or ancestral master the ritual master transforms into, he is one with Lord Lao when exorcising plague demons and evil spirits. This is because the sacred space and residing deities on the body of Lord Lao are completely corresponding to those on the master’s body. The master’s body is Lord Lao’s body. Accordingly, while performing the exorcism ritual, each crucial action of the ritual master’s body corresponds with the sacred space depicted in the chart of Lord Lao and the residing deities. Whether invoking the deities and ancestral masters, warding off evil spirits, or deploying troops and detaining malevolent entities, the body of the ritual master serves as a ritual arena. For instance, locations such as the Well of Torturing Ghosts and Station of Sinking the Heavens and Destroying the Earth, where evil spirits are contained, are also symbolically present on the body of the ritual master—Lord Lao.The Taoist master first invites the deities, transforms himself into a divine body 變身, consecrates the water, and prepares a fire bowl (by drawing a symbol of five horizontal and four vertical lines with burning paper money on a porcelain bowl containing water and small lumps of charcoal, then wrapping the bowl with a piece of paper). He then paces outward in the Constellation of the Three Terraces 三台罡. Next, he kneels with his left foot on the ground while half-squatting with his right foot. He is positioned this way because on the left sole are the Pit of Extricating Ghosts, the Well of Burying Ghosts, the King who Grabs Ghosts, and the King who Overlays the Earth; on both knees are Generals of the Yin and Yang Steps; on the calves are General Zhou of the Lower P Principle, White-marking Sanlang, Black-marking Silang, and the three hundred military prefectures. Additionally, he utilizes his left heel against his anus, known as “plugging the hole” (if this action is not explained by Master Luo, we would simply not understand). This is because there is the Village of Escorting Ghosts on the left heel, and the anus is one of the seven orifices. By plugging the anus, evil spirits will not be able to sneak into the human body. The master then covers the heel with the divine garments (with the God of Front Covering and Rear Covering, and the God of Front Lighting and Rear Darkness on the garments). Subsequently, the master holds a number of rice grains (representing the soldiers and generals) with the five fingers of the right hand (there are 100,000 Yang soldiers and 500 Valiant soldiers), then straightens the (right) arm (where the Marshal who guides the soldiers is located), and throws the rice grains in the distance. This action is known as “sending troops to catch the evil spirits” 發兵捉邪. After sending off the troops, the master performs specific mudras: he pinches the second knuckle of the left thumb (known as “the mudra for summoning ancestral masters”, as there is the place for the ancestral masters), followed by pinching the third knuckle of the right thumb (known as “the mudra for summoning proper masters”) and then the third section of the right thumb (representing the gen 艮 position of the eight trigrams, symbolizing “Mount Gen Plugging the Ghost Pathts”). Next, he moves the right arm (where the Marshal who guides the soldiers is located), starting from the right heel (the Station of Torturing Ghosts), passing through the upper part of the body (where the Venerable Immortal Master Huang resides), reaching the bridge of the nose (where General Tang of the Superior Principle is located), then moving to the chest (where General Ge of the Median Principle resides). Finally, he pinches the right thumb and forefinger together to press the left forefinger (the Station of Imprisoning Plague Demons), signifying the mobilization of ancestral masters, proper masters, the Marshal who guides the soldiers, the Venerable Immortal Master Huang, General Tang of the Superior Principle, General Ge of the Median Principle and other deities. Together, they escort the captured evil spirits and gather them together at the Station of Imprisoning Plague Demons, where they are then cast into the water and fire prisons.After confining the evil spirits, the master proceeds to deliver a forceful blow with his right foot on the ground. This action is performed because the right sole contains the Well of Torturing Ghosts and the Station of Sinking the Heavens and Destroying the Earth. By executing this blow, this signifies that all the evil spirits have been confined within the Well of Torturing Ghosts and the Station of Sinking the Heavens and Destroying the Earth.(Liu 2024, pp. 10–11)

In fact, this concept of viewing the body as a ritual arena has already been presented in similar forms in earlier Taoist literature. For example, the “Rite of Enslaving Evil Ghosts” 役邪鬼法 as described in the Taoist Methods United in Principle 240, as follows:

To begin, (the Master) should establish a camp within the ritual arena to position the (Divine) Troops. Following the offering to the troops, he dispatches the commander-in-chief to apprehend the lesser ghosts. The Master then indicates the location with the Mudra of sunlight rays and assumes an esoteric mudra with hands on the waist, visualizing darkness all around with a luminous path leading to the ghosts. Subsequently, he visualizes towards the direction of the incense fumes, perceiving the troops of the Five Camps, and inscribes the character “yan” (a flash of fire) in the sky as their order. Upon sighting the signal, the soldiers assemble before the master, ready to follow his commands. The master visualizes that his head faces upwards to the sky, with his feet on the ground, his five viscera transformed into the Five Camps, and his mouth into the soldiers’ cave. Next, the master opens his mouth and inhales the qi in the incense, reciting “The ferocious soldiers of the five tigers of the five directions enter my body, establish camps and take position within”. …… He visualizes Marshal (Zhao) apprehending the evil spirits in the air, awaiting their confinement. Following this, he exhales a breath and recites as follows: “The ferocious soldiers of the eastern cyan tiger come out to arrest a certain ghost (exhale), the ferocious soldiers of the southern red tiger come out to capture the evil ghosts (exhale), the ferocious soldiers of the western white tiger come out to catch the evil ghosts (exhale), the ferocious soldiers of the northern black tiger come out to seize the evil ghosts (exhale), the ferocious soldiers of the center yellow tiger come out to apprehend the evil ghosts (exhale)”. Once the evil spirits are captured, the master visualizes the ferocious soldiers and tiger generals biting and subduing them … then raises the Mudra of opening and closing, turns to glance behind, and inscribes (a symbol of) four vertical and five horizontal lines, visualizing (this symbol) as the Iron Barriers Extending to the Sky, obstructing the path of the evil spirits.先就壇起營,駐劄兵馬。祭犒畢,差主帥去收下鬼。用霞光訣指其所,又暗訣叉腰,存四外皆黑,止有一條光路直到鬼處。次對香烟上,存五營兵馬無數,乃虛書出一「欻」字號令於前。將兵見號,齊集來前聽役。却想自己頭頂天,足踏地,五府為五營,口為兵洞。次開口於香上吸,念云:「五方五虎猖兵,入吾身中駐劄立營。」……存元帥在虛空中捉下邪鬼,聽候收禁。却自己噓炁一口,念云:「東方青虎猖兵出為擒下某鬼(呵炁一口),南方赤虎猖兵出為擒下邪鬼(呬炁一口),西方白虎猖兵出為擒下邪鬼(吹炁一口),北方黑虎猖兵出為擒下邪鬼(呼炁一口),中央黄虎猖兵出為擒下邪鬼(噓炁一口)。」收擒訖,存五方猖兵虎將咬伏邪鬼……却下開合訣,回身望後頭,畫四縱五横,想為連天鐵障,抵塞邪路。(DZ1220, juan 240, Daozang 30: 485–486)

In summary, the master visualizes the troops of the Five Camps, with his five viscera transforming into the Five Camps and his mouth becoming the soldiers’ cave. He summons the ferocious soldiers to enter and station within his body, to emerge and apprehend the evil spirits for imprisonment. These troops of the Five Camps mirror the soldiers of the five directions in the chart of Lord Lao—“soldiers of the Nine Yi 九夷 (eastern barbarian regimes) represented by the left hand, soldiers of the Eight Man 八蠻 (southern barbarian regimes) represented by the right hand, soldiers of the Six Rong 六戎 (western barbarian regimes) represented by the left thigh, soldiers of the Five Di 五狄 (northern barbarian regimes) represented by the right thigh, soldiers of the Three Qin 三秦 (central civilized regimes) represented by the head”, as well as the troops of the Five Phases stationed within the five viscera. The transformation of the mouth into the soldiers’ cave is akin to the transformations depicted in the chart of Lord Lao, where the tongue becomes the Bridge to Ferry the Soldiers, the collective teeth form the patrol checkpoint of the Five Camps, and the throat represents the Cave of Hiding Soldiers.

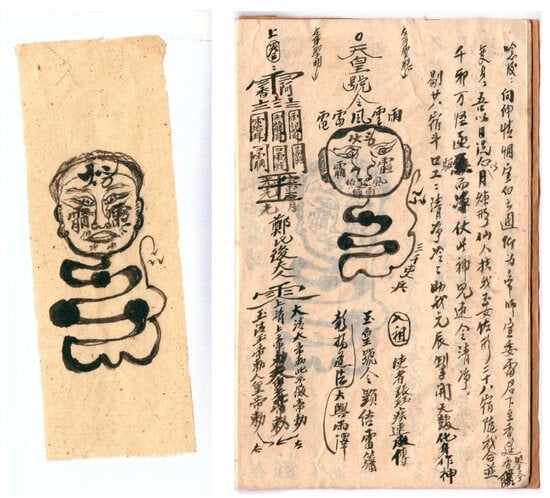

Also worth noting is the connection between the chart of Lord Lao and the practice of banner rites at Shanglong Altar. During my visit to Shanglong Altar in July 2023, I observed two pieces of paper within the page lining of the Liturgy of Thunder Banner (Leifan ke 雷旛科), which had been transcribed by Luo Kui Yilang in 1981, and were also titled “Liturgy for knotting the banner” 結旛科 or “Thunder banner knotted by Zhang” 張結雷旛. The chief deity in this ritual text is Commissioner Zhang Jue 張珏使者, or “Heavenly Lord Zhang Jue, Commissioner of the thunder gods of the five directions”, who is the same Heavenly Lord Zhang mentioned above in the discussion of the thunder lords Gou and Bi. The reverse side of the first page of the text featured an illustration of the “ritual template of Zhang Lei’s rain-praying banner” 張雷祈雨旛法式 (Figure 6). This illustration carried talismanic symbols, such as the “Symbol for commanding the Heavenly Emperor” 天皇號令, and depicts the image of Commissioner Zhang. One piece of paper (Figure 6) portrayed Commissioner Zhang’s image as seen in the “ritual template of Zhang Lei’s rain-praying banner”, showcasing the commissioner’s face with symbols such as the “Fire Dipper” 火斗, “Great Yang” 太陽 (below the left eye), “Great Yin” 太陰 (below the right eye), “Sacred Intelligence” 聖聰 (left ear), “Sacred Brightness” 聖明 (left ear), as well as the Earl of Winds (below the nostrils) and the Master of Rain (corners of the mouth). Notably, the positions of the Great Yang, the Great Yin, the Earl of Winds, and the Master of Rain align with those in the chart of Lord Lao.

Figure 6.

Ritual template of Zhang Lei’s rain-praying banner (right) and one of two pieces of lining paper (left) included in the Liturgy of Thunder Banner of Shanglong Altar.

The second piece of paper, shaped like a human head, bears a note on the back reading “This image was left over from the liturgy of presenting (the ordinand) for office (and seeking a ritual) lang name 奏職郎 for Luo Donghong 羅東紅, celebrated in Gengzitou village from the 13th to 15th days of the 12th month in the dingmao year (1987). The thunder banner was a golden banner drawn according to this human head, and was later knotted as a dragon head. [雷旛照此人頭畫的金旛,後結為龍頭乙隻。]”. Luo Donghong (1968–), ritual name Luo Ying Liulang 羅迎六郎, hailing from Jilong township, Guidong county, Hunan province, was a disciple of Luo Qidong accepted post-1981 (Liu 2000, pp. 226–27). The inscription on the back of the head-shaped paper cutout was authored by Luo Qidong, indicating its association with him. The golden banner, raised by Taoist priests of the military altar during the Jiao ritual of the Great Banner, was crafted from blue cloth, with the upper portion adorned with talismanic symbols drawn in ink and the lower half torn into five lengthy strips. Following the banner’s erection, the five strips were intertwined to form a specific-shaped ball, serving as a measure of the ritual’s success (Liu 2000, pp. 298–99). The human head depicted in the golden banner erected during Luo Donghong’s ordination ritual likely corresponds to the head of Commissioner Zhang in the “ritual template of Zhang Lei’s rain-praying banner”. Given the decisive significance of banner knotting for the ritual life of Taoist priests (Mozina 2021), this demonstrates the importance of Commissioner Zhang within the tradition of Shanglong Altar.

6. Concluding Remarks

There are clear differences between the Chart of Lord Lao of Shanglong Altar and the Chart for the Cultivation of Perfection or the Diagram of Inner Canon which have received more attention in previous studies. The Chart for the Cultivation of Perfection primarily pertains to internal alchemy practices, while the Diagram of Inner Canon is associated with both internal alchemy and medicine. In contrast, the Chart of Lord Lao of Shanglong Altar is primarily linked to Taoist exorcism. In terms of the emphasis on exorcism, the Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao falls within the same category of images as the Chart of the Skeleton of Lord Lao analyzed by Patrice Fava and the Chart of the Residence of the Buddhist Holy Spirits, and Chart of the Catching of Ghosts examined by Brigitte Baptandier. However, all these charts and diagrams belong to the realm of Taoist body charts. The concept that the body depicted in these images is connected to sacred space and cultivation rituals that have ancient origins, probably dating back to the Central Scripture of Laozi, an ancient Taoist text focusing on the cultivation of immortality (Lagerwey 2004). It is believed that the Central Scripture of Laozi was composed during the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 CE) and contained as one of its themes a description of the journey to the divine realm, originally accompanied by illustrations of the cosmic scenes described in the scripture (Schipper 1995). According to research by Catherine Despeux, the earliest complete Taoist human body charts emerged in the mid-10th century, directly stemming from the early development of Taoist internal alchemy techniques in the late 9th and 10th centuries (Despeux 2018b, p. 2). Therefore, the Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao and other Taoist body charts emphasizing exorcism likely postdate the charts for the cultivation of perfection and other Taoist body charts focusing on cultivation, drawing inspiration from the latter.

In the context of the Hunan–Jiangxi border region, Taoist body charts primarily aimed at exorcising malevolent spirits can be traced back to the Chart of the Skeleton of Lord Lao copied in the 36th year of the Kangxi reign (1697). Both the Chart of the Skeleton of Lord Lao and a chart for cultivation of perfection are encompassed within the Alchemical Secrets of the Supreme Ultimate, also known as the “Alchemical Rite of the Supreme Ultimate of the Marvelous Jewel” 靈寶大極鍊法, of Xianying Altar 顯應壇 (Altar of Conspicuous Response) in western Jiangxi.10 The Alchemical Secrets of the Supreme Ultimate is a text intended to release the deceased from purgatory through the ritual of refinement, although the principle of refinement aligns closely with Taoist cultivation practices. Upon perusing the Alchemical Secrets of the Supreme Ultimate, it becomes apparent that the Chart of the Skeleton of Lord Lao was not directly linked to the ritual of refinement, which does not necessitate specific exorcisms. The inclusion of the Chart of the Skeleton of Lord Lao in this text likely stems from the fact that this chart presented a frontal view of the human body, distinct from the side view depicted in the chart for cultivation of perfection. This distinction would have aided Taoist priests in comprehending the content related to the Taoist human body within the ritual texts of refinement.

The distinction between the Chart of the Skeleton of Lord Lao of Xianying Altar and the Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao of Shanglong Altar is noteworthy. The former predominantly features space and deities that can be traced back to emerging Taoist texts from the Song and Yuan dynasties, such as the Correct Rites of the Heart of Heaven. It bears the structure and certain elements of Taoist body charts for cultivation originating from classical Taoism, with the exception of the “King Changsha who Destroys Temples on the Left Hand” and “General Liu on the Right Hand”, likely originating from the rites of Mount Lü. In contrast, the distinctive characteristics of the latter include the presence of numerous deities from Mount Lü, as well as some from the Pu’an School and the rites of Mount Mei. Additionally, the inclusion of the gourd space at the belly, symbolizing the Hell of Darkness and bearing a strong influence of Mount Lü, sets it apart. It is crucial to recognize that the Chart of the Skeleton of Lord Lao incorporates elements of classical Taoism and the emerging exorcistic rituals of the Song and Yuan dynasties, as seen in the ritual practices of Xianying Altar. Conversely, the Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao features a trinity of the Heavenly Worthy of Primordial Origin, the Realized Person Lord of the Tao and the Heavenly Master Lord Lao (derived from classical Taoism), along with the four marshals Pang, Liu, Gou, and Bi (derived from the emerging exorcistic traditions of the Song and Yuan dynasties) as prominent figures. These elements had minimal influence on the ritual practices of Shanglong Altar. This suggests that the Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao does not represent the original tradition of the school of Mount Lü, but rather borrowed elements from charts such as the Chart of the Skeleton of Lord Lao, which focused on the emerging exorcistic rituals of the Song and Yuan dynasties. This illustrates the overall evolution of Taoist body charts since the Song and Yuan dynasties. Firstly, the early Taoist body charts, with their focus on cultivation, laid the foundation for the development of Taoist body charts centered around exorcism. Secondly, within the category of Taoist body charts emphasizing exorcism, earlier examples are likely those rooted in the emerging exorcistic rituals of the Song and Yuan dynasties, which subsequently paved the way for the creation of Taoist body charts based on the tradition of Mount Lü.

The characteristics of the Chart of the Skeleton of Lord Lao and the Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao are closely linked to the liturgical traditions of the Taoist altars to which these charts belong. Based on texts such as the Alchemical Secrets of the Supreme Ultimate and Petitioner’s Journey Through the Heavens (Zhangmi yunlu 章秘雲路) at Xianying Altar,11 it is evident that the liturgical tradition of this altar was rooted in classical Taoism, incorporating a blend of classical Taoist rituals and emerging exorcistic rituals from the Song and Yuan dynasties. In contrast, Shanglong Altar was characterized by the dominance of the rites of Mount Lü and the Pu’an school, with its exorcistic traditions stemming from the Song and Yuan dynasties and influenced by the school of Mount Mei in central Hunan. The Chart of the Skeleton of Lord Lao and the Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao effectively reflect the structure of their respective Taoist altars’ liturgical traditions. While the former represents a fusion of classical Taoism and the emerging exorcistic rituals of the Song and Yuan dynasties,12 the latter embodies a combination of the emerging exorcistic rituals of those dynasties and traditions that are more local, such as the school of Mount Lü. The term “local” in this context signifies a later and less extensive integration into Taoism, with related texts not yet included in the Taoist Canon, the officially recognized national compilation of Taoist literature. However, from the perspective of the Chart of the Taoist Rituals of Lord Lao, despite the pronounced “local” colour in the liturgical tradition of Shanglong Altar, it is already an integral part of the Taoist tradition. This is because its ritual arena, ritual practices, and masters had all “harmonized with the Tao to achieve perfection” 與道合真—the Tao being embodied in the form of its incarnation, Lord Lao.

Funding

This research was funded by National Social Science Fund of China, grant number: 18CZJ021.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

I am most grateful to the journal’s reviewers, Jing Li, Edward Allen for their very useful comments, as well as Luo Ranyi 羅燃裔, Liu Jinfeng 劉勁峰, Zhu Zhongfei 朱忠飛, and Patrice Fava for their help in collecting the firsthand materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In this essay, “altar” (tan, 壇) refers to the space centered on a home altar, as well as to the masters of this altar, not just the altar of ancestral masters set up at the chief master’s home. |

| 2 | Cf. Liu (2000, pp. 232–52, 260–61). The Pu’an school is a regional ritual tradition with the Buddhist Chan Master Pu’an 普庵 (1115–1169) as its patriarch, initially centered at the Cihua Temple in the Yuanzhou prefecture (modern Yichun City) of northwestern Jiangxi. The Pu’an school was mainly popular in Fujian, Zhejiang and Jiangxi provinces of southeastern China. With the development of the cult of Pu’an and the Pu’an school came a transformation towards Taoism within the cult. Accordingly, the identity of the masters of the Pu’an school is variously Buddhist, Taoist, or Buddho–Taoist (Tam 2021). The Anterior Heaven school in Shangbao is said to have been introduced from Xingning county in northern Guangdong province and transmitted for more than twenty generations. Regarding the Anterior Heaven school in northern Guangdong, the Qianlong Nanxiong fuzhi 乾隆南雄府志 (1753, juan 3) mentions the “Masters of the Anterior Heaven” who celebrated the Festival of the Nine Emperors 九皇會. These Anterior Heaven masters are most likely Taoists. As for the situation of the Anterior Heaven school in other parts of southern Jiangxi, the Kangxi Longnan xianzhi 康熙龍南縣志 (1709, juan 10) records the Taoist priest Wang Tongxuan, who was “proficient in methods for eliminating demons of the Anterior Heaven school” 精先天教誅邪. According to the Daoguang Yudu xianzhi 道光雩都縣志 (1830), the eminent Taoist Liu Yuanran 劉淵然 (1351–1432) was taught the “Thunder rites of Anterior Heaven and Orthodox Unity” 先天正一雷法 (juan 25); Yuan Shi, also lived in the Ming Dynasty, was versed in the “School of Anterior Heaven and Pure Tenuity” 先天精[清]微之教 (juan 26). Judging from these clues, the Anterior Heaven school should be a Taoist tradition. |

| 3 | This phenomenon can also be observed at Taoist altars of the Lüshan tradition in western and northern Fujian Province; see Li (2011, pp. 229–40). It is also worth noting that the sacred mountain of Tianxin Zhengfa, Mount Huagai in Fuzhou (Hymes 2002), has been an important pilgrimage center for believers in southern Jiangxi. The pilgrimage groups sometimes also included Taoist priests, see Daoguang Ganzhou fuzhi 道光贛州府志 (1848), juan 60; Tongzhi Huichang xianzhi 同治會昌縣志 (1872), juan 25. Moreover, during my fieldwork in southern Jiangxi, I discovered that there are indeed Taoist altars that have an inherent connection with the Tianxin Zhengfa tradition. |

| 4 | Names with the character “lang” 郎 or “fa” 法 have been popular among (Taoist) ritual masters in Fujian, Guangdong and Jiangxi regions since Song and Yuan dynasties. It was even customary for these masters to perform rituals to give lang or fa names for lay believers (Chan 1994, 1995; Liu 2000, pp. 168–70, 222–31, 263; Wu 2019, p. 23). In Chongyi, the ritual names of Taoists are mainly of two kinds: fa names and lang names. Among them, fa names are obtained by the apprentice Taoists during the ritual of their graduation and ordination, which are equivalent to the junior rank, and the ritual is known as “initiation of the audience” 開朝 or “first ordination” 初度. A Taoist priest who has a fa name can further obtain a lang name, and this requires him to participate in the “three-day ordination ritual of the Great Banner of the Yangping (Diocese) 三天陽平大幡傳度儀式”. Only Taoists who have acquired a lang name can take on disciples and celebrate large-scale rituals on their own (Liu 2000, pp. 245–46, 326, 345). |

| 5 | With regard to the other two place names mentioned in the inscription, the Shanglong where Luo Qidong’s master, Liu Yun Wulang, lived should be the present-day Shanglong natural village in Miaoqian administrative village, Haotou township, Rucheng county; Luo’s Junyuan village should be Shangbao township, Chongyi county, less than 10 miles away from Shanglong (Liu 2000, p. 225). |