Abstract

Descola describes western culture, influenced by the Christian worldview, as “naturalist”. However, semiotic and ethnographic research shows that different perspectives about the relationship between humans and animals coexist with mainstream naturalism. In particular, the introduction of animals in churches is not rare in Italy today, even though it fuels an ongoing debate. The relationship with animals is central in Saint Anthony’s figure and feast, which includes the blessing of animals. This article first focuses on the figure of Saint Anthony, finding in its first sources the seeds of a worldview based on love for creation that fully flourishes centuries later with Saint Francis, then it contextualizes the blessing of animals in the context of a changing sensitivity towards animals, which are often considered from an affective perspective and as part of an ecological standpoint that is also expressed in the institutional discourse of the Catholic Church. Then, the patronal feast of Saint Anthony and the blessing of animals in two different urban communities of Turin (Italy) are the subject of an ethnosemiotic analysis highlighting the animals’ position (inside or at the border of the sacred space), the rite’s structure and the relation between the verbal discourse and the performance of celebrants and worshipers. The position of the animals is thus considered as the expression plane of semantic values about their status in relation to the family.

Keywords:

ethnosemiotics; animals; analogism; ontology; Catholic church; urban context; Saint Anthony; worship; sacred space; blessing 1. Introduction

Philippe Descola (2013, p. 122) classifies cultures according to four ontologies: animism, totemism, naturalism and analogism:

- -

- Animist cultures recognize that physically different beings, such a man and a tiger, can share similar interior features, thus recognizing some animals as men and vice-versa.

- -

- Totemist cultures recognize similarities between beings in both physical and interior features. They typically justify the relation between social groups referring to the relation between species of animals.

- -

- Naturalist cultures classify beings according to their physical similarities, despite possible interior differences. In these cultures, a discontinuous gap divides humans from other animals.

- -

- Analogist cultures acknowledge both physical and interior differences between beings. In these cultures, a continuum of small differences divides humans from animals, but some human features are recognized in specific kinds of animals.

Descola’s perspective is widely debated since it tries to enrich Levi-Strauss’ analysis of totemism, in the attempt to actualize structuralist methods and perspectives. Many authors adopted it (e.g., Viveiros de Castro 2014). For this reason, it seems worth discussing whether this general classification of cultures holds at the ethnological observation of human–animal relations in everyday experience. In particular, though a culture can be described, in general, as “naturalist”, it is possible that in specific social discourses the semantic frontier between humans and animals is less rigid and subject to negotiations.

In the frame of his classification, the author describes western culture as naturalist: “Humans are distributed in different collectives that exclude nonhumans. The structure and properties of collectives of humans are indexed to the difference between humans and nonhumans” (Descola 2013, p. 277). According to the author, religion has a role in structuring collectives: “for the nature of the Modern to come into being, a second operation of purification was necessary: humans had to become external to nature and superior to it. Christianity was responsible for this second upheaval, with its twofold idea of man’s transcendence and a universe created from nothingness by God’s will” (Descola 2013, p. 66).

Different cultures attribute moral qualities and human features to nonhumans. For example, “it is also perfectly normal that analogical collectives subjected to Christianization should enthusiastically recruit the Catholic saints, along with the powers that each of them is recognized to possess, into the regiments of nonhumans” (Descola 2013, p. 275).

Descola’s categorical classification seems challenged by ethnographic observation. In today’s Italian Catholic churches, it is not rare to see animals: in many cases, families bring their pets to mass. Catholic websites report different opinions on the subject, thus testifying to the spread of this phenomenon. For this reason, the authors of the present paper decided to use ethnosemiotic methods to observe what happens during an important ceremony: the patronal feast of Saint Anthony and the blessing of the animals.

In particular, the observation will highlight the position of the animal in relation to the sacred space and will analyze the structure of the rite and the relation between the verbal discourse and the performance of celebrants and worshipers. Animals can be forbidden in the sacred space1; they can be allowed or obliged to remain in liminal spaces internal or external to the church. The position and the interaction of the animal will be considered as the expression plane of semantic values about its status in relation to the family in the urban postindustrial context.

It is very important to emphasize that our intention is not the realization of a diachronic study about continuity and change in Catholic theology and its sensitivity toward animals. Semiotic methodology is synchronic. The focus is on our present and the actual relation between worshipers and their pets. In what follows, references to the figure of St. Anthony in Italian folklore and to early hagiographical sources are functional to understand the virtual meanings associated with the relation between two figures: a saint and an animal. In the countryside, this configuration is associated with rituals involving bonfires and divination, while in contemporary cityscapes, observation reveals different meanings.

1.1. Ethnosemiotics: Scope and Methods

Ethnosemiotics was described by Algirdas J. Greimas (1976) as a collaboration between semiotics and ethnology, aimed to avoid Eurocentric biases in the construction of the theory of meaning. Developed in Italy during the 1980s by Maurizio Del Ninno (2007), it was further defined by Francesco Marsciani (2007) as an inquiry on the conditions of possibility of ethnography. “These are nothing less than the significant conditions of life in common, conditions that are significant to the extent that they articulate and categorize the intersubjective experience of the lived world (Marsciani 2020, p. 6)”. Ethnosemiotics has been applied on different occasions to religious practices (Petrini 2021; Galofaro 2022, 2024).

In the present case, ethnographic observations have been preceded by a list of research questions, in order to orient the participation of the researcher. The comparison between rituals and the exposition of the results in Section 4 are organized accordingly. The definition of the research questions and the narrowing of the scope of the observation is crucial: the position of the viewer influences the results in many ways: events outside the field of observation are undetermined (cf. Galofaro 2024), and people in the observer’s field of presence could be disturbed. Research questions help to define the observables: for example, a central question implies observing whether the limit of the sacred space is transgressed by animals or not: while blending into the crowd, the observer must try to keep an eye on the entrance of the church and on the walls. The importance of maintaining cover and not disturbing the participants of the ritual affects also the methodology: on different occasions, e.g., during the blessing of the animals, many worshipers record the ritual, and so does the researcher. In other cases, e.g., during the mass, worshipers maintain a composed demeanor. Some quick ethnographic notes can still be taken with the smartphone and elaborated in a field diary after the ceremony, using a tablet.

It is possible to ask why we did not interview the participants in the ritual. Of course, this could have been possible. However, the application of ethnosemiotic methods aims to let meaning emerge from semiotic systems other than language in the strict sense. In this perspective, meaning is more the product of the interactions taking place in the ritual (e.g., spaces, boundaries and movements between them; conjunction and disjunction between actors) than of the verbalizations of the participants.

Every ethnographical description gains in depth what is lost in amplitude. Further field work is needed to confirm our first impressions.

1.2. Semiotics and Ethnosemiotics: Affinities and Divergencies

In what follows, semiotic tools and notions will be applied to field notes resulting from observation. Thus, for example, pets crossing the border of the sacred space will be compared to the hero of the folktale, moving through different spaces and cultures. What legitimates this kind of generalization?

Ethnosemiotics is not semiotics (Marsciani 2020, p. 2), for different reasons. Semiotics is a method usually applied to already given data, considered by semioticians as texts. But, in a semiotic perspective, a text is, in turn, the result of the application of semiotic analyses (Hjelmslev 1961). Thus, semiotics does not recognize texts in the world; semioticians construct the objects of their studies by projecting their categories onto the world.

The prefix “ethno”, then, does not just represent an empirical practice of collecting data. Ethnosemiotics is an investigation into the conditions of sharing the same world by intersubjective instances. At the same time, ethnosemiotics does not acknowledge any a priori distinction between culture and ontology. It is more interested in testing it against the conditions that make objects exist, that make things appear and take on meaning. Some semiotic schemas can indeed create the false impression of a dichotomy between meaning and ontology. For example, according to Umberto Eco (1979, p. 14), two different instances mediate between the expression plane of the text and the actualized content plane, i.e., its meaning: first, culture, considered as a repository of dictionaries, codes, ready-made sentences, scenarios and ideologic frames; second, the concrete circumstances of utterance, allowing the receiver of a message to select a meaning among different possibilities. According to Eco, the first medium introduces the abstract, conceptual structures of the meaning, while the second medium allows the text to refer to the concrete word.

However, as Eco writes, in fictional texts, the circumstances are reproduced in the narrative context. In a similar way, when observing the world (the “circumstances”), one finds more or less explicit cultural codes: dress codes, auditory signals, gestures, functionalized architectural spaces. At the same time, circumstances are a chaosmos in which the culturally based interpretations of the observer are continuously challenged and should not be confused, in philosophical terms, with ontology.

2. The Re-Elaboration of the Figure of Saint Anthony and a Pioneering Definition of a Respectful and Harmonious Relationship with Animals and Creation

Saint Anthony the Great (251–356) was an Egyptian hermit, one of the key charismatic figures at the basis of the development of monasticism (Giorda 2008). The most important sources on this desert father are his biography by Athanasius, who knew Anthony personally, as well as a corpus of sayings (Apophthegmata) and letters attributed to Anthony himself.2 In the course of time, hagiographies, legends and iconographic themes flourished, enriching the episodes narrated in Athanasius’ work and also adding different facets to the character of Anthony. According to Di Nola (1976, p. 207, my translation), “In the reuse that has been made of it by the subaltern European religions, the model has undergone radical transformations, to the point that an unbridgeable gap has opened between the popular image and the learned hagiographic tradition. It is not unlikely, although difficult to document, that stratifications belonging to ancient beliefs and remote pagan rituals of the peasant plebs have accumulated on the saint, in a syncretistic process that appears quite clear from the twelfth century onwards.” The reworking of the figure of Anthony continues to this day, as part of a dense network of intertextual and intermedial discourses that prove that the story of the saint contains archetypal themes that still seem relevant and attractive in today’s culture, where they are also the subject of research from many different theoretical perspectives.3 Indeed, if all saintly figures are part of the immaterial cultural heritage, as the product of a polyphonic and progressive codification,4 Saint Anthony is a particularly interesting case study, precisely because his character changed greatly over time, embodying different values, being associated with different themes, elements and beings and also changing his temperament to some extent.5

Several scholars have explained the historical and cultural processes that led to the association of Anthony with animals as well as with a variety of other symbols, including the bell, the stick and fire. As for animals and fire, which are of particular interest for the present purpose, Di Nola (1976) and Fenelli (2006, 2011), for example, show how they are related to the attribution to Anthony of patronage over the disease commonly known as “Saint Anthony’s fire”, which the saint was not only supposed to cure but sometimes also to cause as a punishment. The spread of this disease went hand in hand with the founding and flourishing of the congregation of the Hospital Brothers of Saint Anthony, who in turn were known for breeding pigs that were allowed to circulate freely in the cities. From this first association with the pig, which produced a successful iconographic theme and was accompanied and supported by a rich corpus of legends in which the saint himself interacts with this animal, the patronage of Saint Anthony was extended to all domestic animals in general. The veneration of Saint Anthony as the patron saint of domestic animals spread throughout Europe and is still alive today, especially in the Mediterranean region.

In scholarly reconstructions of the transformation of the hagiographic figure of Saint Anthony, there is a recurring tendency to draw a rather radical contrast between the figure of the hermit, as portrayed in the earliest sources, and that of the protector of animals, which is usually characterized by the layering of legendary narratives from popular piety. Some scholars even speak, for the former, of a “zoophobic characterization” (Di Nola 1976, pp. 210–11), a claim that is supported by reference to some episodes reported in Athanasius’ Life, such as the fact that the demons took the form of wild animals in their attacks on the holy hermit (Athanasius of Alexandria 2015, chps. IX, XXIII, XXXIX) or the episode in which Anthony scolds the wild animals that are damaging his orchard and admonishes them to stay away:

But after this, seeing again that people came, he cultivated a few pot-herbs, that he who came to him might have some slight solace after the labor of that hard journey. At first, however, the wild beasts in the desert, coming because of the water, often injured his seeds and husbandry. But he, gently laying hold of one of them, said to them all, “Why do you hurt me, when I hurt none of you? Depart, and in the name of the Lord come not nigh this spot.” And from that time forward, as though fearful of his command, they no more came near the place. (Athanasius of Alexandria 2015, chp. XLIX6).

However, this episode in particular can provide the basis for a different interpretation, which does not involve a radical opposition but finds in the first sources about the hermit some themes and isotopies that are further developed in the later hagiographical accounts. In the passage under consideration, for example, animals damage the saint’s orchard simply because it is in their path to the water, not as some kind of attack. The hermit has a quite friendly—if stern—attitude towards the animals: He holds one of them gently and acknowledges it as a creature by speaking to it (rather than using more physical language or punishing it, for example), and the animal listens and understands, and it and its fellows obey.7 Anthony establishes, therefore, a relationship with animals based on mutual respect, which could hardly be classified as “zoophobic”.

In another episode, the wild beasts surround Anthony and threaten him with their open jaws, but Anthony speaks to them and says that they can devour him if they have received power from God to attack him, but if they have been sent by the demons they must flee away, and so they do (Athanasius of Alexandria 2015, chp. LII). In this episode, then, the animals seem to have been incited by the demons, but again they respond positively to the saint’s words. In general, “the demons rather fled from him, and the wild beasts, as it is written, ‘kept peace with him.’” (Athanasius of Alexandria 2015, chp. LI). Anthony’s behavior towards animals is always non-violent and based on communication and respect. Undoubtedly, animals have a disturbing connotation in Athanasius (in fact, many of them, such as crocodiles, not only naturally represent a danger to humans, but their shape is also imitated by demons, and in at least one case, in the episode just mentioned, their behavior is determined by demons), and they are kept at a distance and not admitted as companions in the saint’s ascetic life; nevertheless, they are not presented in an absolutely negative way, since they are interlocutors of the saint (although, of course, subordinate) and establish an overall peaceful and respectful relationship with him.

This depiction of Anthony in harmony not only with the animals, but generally with the whole of creation, is reinforced by a passage from the first of his letters (Anthony 1995, p. 242, my translation): “The Spirit sets a limit to the eyes, to lead them to an upright and pure gaze, because we no longer have anything extraneous; it guides the ears to hear with peace, and they no longer want to listen to the curses and injuries of men, but to hear words of benevolence and mercy for all creatures.” From this point of view, elements such as animals and fire, which can initially appear quite heterogeneous in the iconography of the saint as well as in the associated devotional practices, appear closely linked in a coherent worldview. Indeed, Anthony seems to make an important contribution to the development of a cosmological perspective based on a relationship of love and respect for all creatures and for the world, which is seen as God’s creation. In this sense, the figure of the Egyptian hermit, as it appears in the Life by Athanasius and in the writings attributed to him, seems to be a precursor of several hagiographic themes that are then developed in the literature about many saints who have a relationship of communication and even friendship with animals.8 In semiotic terms, this hagiographic text presents a discursive configuration (i.e., a “motif”. Cf. Greimas and Courtés 1982, pp. 49–50): in Athanasius, this configuration it is represented by a stable connection between three figures. First, the figure of a hermit, a monk or a friar; second, a figure representing one or more animals; third, the figures associated with wilderness. These figurative micro-structures are autonomous from the themes that are associated with them. Configurations represent the condition of possibility of ethno-literary studies (Bertetti 2013, pp. 109–12). For this reason, a configuration can be received, and often reinterpreted, by posterior hagiographic literature, shaping a new worldview. It seems interesting to consider in this light the Franciscan sources, where this micro-structure becomes the basis of the way of life practiced by the Saint and proposed to the faithful.

3. The Contemporary Cultural Context and Devotional Formulas in Catholicism

This worldview has become increasingly relevant in contemporary Catholic culture. Since the 1970s at the latest, the Church seems to be increasingly concerned with environmental issues. In response to these issues, important papal documents propose and progressively define an ecological perspective based on spiritual values such as respect and love for creation. Among the most important magisterial interventions in this regard are Paul VI’s apostolic letter Octogesima Adveniens (1971),9 John Paul II’s apostolic exhortation Inter sanctos (1979),10 in which the pontiff praises Saint Francis and declares him patron saint of promoters of ecology, and Benedict XVI’s encyclical letter Caritas in veritate (2009).11 The Franciscan model became a central theme during Pope Francis’ pontificate. The encyclical letter Laudato si’ (2015),12 in particular, stresses the idea of “integral ecology”, related to the emphasis on love and care for the planet and the respectful consideration of all creatures as brothers and sisters, as part of a harmonious whole that encompasses creation in all its richness and diversity.

In contemporary culture, the ecological perspective is paralleled by changing attitudes towards animals, especially in urban contexts, where animals are no longer seen so much as labor or food, but mainly as companions, while more and more parts of society and institutions recognize that they should be granted legal protection and basic rights.13 The relationship with pets, in particular, is in fact an affective and non-utilitarian one. These changes in intangible cultural heritage also play an important role in the way in which material heritage is interpreted and lived. This becomes clear in the case of churches. In recent years, at least in Italy, there has been a lively debate about whether animals should be brought into churches. The Code of Canon Law does not explicitly prohibit the bringing of animals into churches, and the lack of a specific rule to be followed results in different and contradictory interpretations. As a consequence, many religious institutions appeal to common sense by not prohibiting the access of animals but restricting it as much as possible.14 However, the opinions of believers differ: some are openly against the admission of animals, especially during rituals,15 while others, on the contrary, claim that they should be freely admitted as creatures of God. For example, this position was taken publicly in 2017 by Licia Colò, a well-known TV presenter, and her statement of course stimulated discussion in the media.16 According to the media, Pope Francis himself intervened about this issue several times, stating that choosing pets over kids is selfish, and that treating animals as children is a form of cultural degradation.17

This controversy has interesting and important implications because it involves the redefinition and negotiation of the boundaries of sacred space, the status of animals (the reduction of the hierarchical distance between animals and humans) and the way in which the faithful interact with (for instance how they move, act, stay, pray, etc.) and inhabit the codified space of the church. In particular, the relationship between tangible and intangible cultural heritage—i.e., between the cultural definition of the relationship between humans and animals and their integration into the religious sphere and the way in which the materiality of the church building and its surroundings is interpreted and lived—seems to be changing due to the growing importance attached to emotions, namely the affective bond between humans and pets, which takes the place of a more traditional relationship that, as I argue below, does not exclude respect but is mainly based on a hierarchical distinction between humans and animals that is also functional to a certain economic system in which animals are primary resources.

The worldview based on the idea of a harmonious relationship with creation and the changed consideration of animals have an influence on contemporary devotional practices on the occasion of the feast of Saint Anthony, which is celebrated on January 17. In addition to the blessing of animals, there is a tradition in several Italian villages and towns of celebrating the feast of the Saint with a bonfire. These two ritual moments have a double transversal nature: a diachronic and a synchronic one. On the diachronic level, the rituals with bonfires certainly have a pre-Christian origin, and on the synchronic level, the ritual during the feast of Saint Anthony can be compared with other occasions where the celebration of religious events is still accompanied by bonfires (e.g., in June, in connection with the solstice or Saint John the Baptist’s feast). On a diachronic level, the blessing of animals also has ancient roots and has interesting enduring features too. For example, although animals were key elements in the economic structure of society in the peasant tradition, there are clear traces that there was also a kind of affective or at least moral sensitivity towards them. Di Nola (1976, p. 211) thus reports that, in some communities, Saint Anthony was believed to encourage the ethical treatment of animals and punish those who violated the taboo of making animals work on the day of the Saint’s feast. In the Marche region, moreover, “Saint Anthony visits all the stables on the night of the eve and asks the animals how they were treated by their masters, blessing or cursing them depending on what the animals tell him” (Di Nola 1976, p. 211). This traditional form of respect (attested, again, by the act of speaking with them and caring for their wellbeing) can be read as the root of today’s attitude, in which respect is increasingly linked to an affective commitment towards domestic animals. On a synchronic level, the feast of Saint Anthony is not the only occasion on which animals are blessed, just as with fire.

This synchronic transversality can be seen in the blessing formulas used during the feast of Saint Anthony. Such formulas are mainly taken from the official Italian translation of the liturgical book Ritualis Romani De Benedictionibus, whose Italian title is Benedizionale (1992). The title is translated in English as Book of Blessings. We refer to the Italian edition, since “the Italian edition of the ‘Benedizionale’ has been elaborated in successive phases—a partial version of the Latin typica, experimentation, adaptation and new texts—through multiple experiences and skills with a focus on the receivers, individuals and communities, in a vast range of ecclesial and social situations” (Benedizionale 1992, p. 13).

In the part dedicated to “Blessings for popular devotion”, there is a formula specifically dedicated to fire. Among the special occasions that could entail a blessing of fire, the Benedizionale mentions Christmas, the feast of Saint Joseph, the Easter rite and the Assumption, but not the feast of Saint Anthony, which is thus subject to the general formula reserved for “other circumstances”. In some parts of this ritual, fire18 is incorporated into a symbolism of light, which in turn is linked to the theme of love (i.e., charity) and to a cosmological perspective, as expressed, for example, in the prayer of blessing (Benedizionale 1992, p. 663, my translation):

Blessed be thou, God the Father Almighty:

- In the beginning you created light

- and you kindled in man,

- made in your image,

- the spark of your love; with a light column

- You led your wandering people in the desert

- towards the promised land;

- in the fullness of time you sent your Son

- to bring into our darkness

- the burning light of truth and grace,

- and after his glorious ascension

- you poured out the flame of your Spirit

- on the nascent Church.

- Bless this fire on the feast of [Name] …

- And make it blaze in our hearts

- the fire of your charity.

The blessing of animals is also not linked to a single, specific feast, but has a more general character. There are two alternative prayers of blessing, and both are well representative of the general evaluation of animals in the Benedizionale; although they are part of a harmonious and beautiful creation, they are subordinate to man as his helpers:

- O God, source of all good,

- who in animals hast given us a sign of your providence

- and a help in our daily toil,

- through the intercession of Saint [Name]

- grant that we may know how to make wise use of them,

- recognizing the dignity and limitations

- of our human condition.

[…] Or:

- O God, who hast disposed all things with marvelous wisdom,

- and hast conferred dominion over all creatures

- upon man made in thy image,

- stretch out thy hand,

- so that these animals may be of help to us and

- relief in our needs,

- and grant that in a harmonious relationship with creation,

- we may learn to serve and love you above all things.

- Through Christ our Lord.

- Amen.

The first of these two formulas is the one used in both blessings observed in our ethno-semiotic research. It is evident, then, that the rules and traditional formulae of the Church are still imbued with a more traditional sensibility and barely adhere to the contemporary valorization of animals. This new perspective is particularly evident in urban contexts, where animals are mainly seen as pets but where, nevertheless, there is no univocal interpretation about their position in the sacred space. Accordingly, there are a variety of orientations and, consequently, practices in cities, and the feast of Saint Anthony provides a rich basis for fieldwork to explore similarities and differences between urban communities.

4. Ethnosemiotic Analysis

4.1. List of the Observations

Though limited, the observations included different types of ritual: mass, procession, vespers and blessing of the animals:

- Mass celebrating the patronal feast of Saint Anthony the Great, followed by a procession in honor of Saint Anthony. Parish of Saint Anthony in Turin. 14 January 2024 (Sunday morning).

- Vespers, followed by the blessing of the animals. Parish of Saint Anthony in Turin. 17 January 2024 (Wednesday late evening).

- Mass celebrating the feast day of Saint Anthony the Great. Followed by the blessing of the animals. Parish of Saint Agnes in Turin. 24 January 2024 (Sunday morning).

The two parishes are different. Saint Anthony is a big parish in the Northern suburbs. The mass is crowded with lower class worshipers and immigrants; Saint Agnes is central, close to the park near the River Po, and frequented by middle-class Italian faithful.

4.2. The Space of the Ritual

The Church of Saint Anthony is a big, modern, concrete church. It has a trapezoidal plan, and it is wider than it is long. There are some icons of Saint Anthony, painted in an oriental style, but figures of animals are absent. The only exception is the processional banner and the statue of the Saint, in which Anthony is painted beside a piglet—thus, mobile elements. During the mass, a couple of dog owners remain in the back of the church, near the entrance. The number of families with pets is very limited. The church is mainly occupied by different brotherhoods participating in the following procession: some Italians are dressed as crusaders, while some immigrants, wearing a white cloak with two blue stripes, belong to an association devoted to the Virgin Mary (Misioneros de la Reyna de la Paz, established in Turin in 2013). There is also the marching band of the tram-drivers.

Unlike the blessing, the mass is not dedicated only to pets. However, some of them also participate in the procession. They occupy liminal spaces: behind the procession or on the sidewalks. This is probably because worshipers do not walk as fast as dogs and the latter risk being stampeded by the crowd. In these spaces, families with pets interact with families with children. During the procession, many families with babies and pets observed the ritual from the balconies, another liminal space.

During the vesper in the parish of Saint Anthony, the hall of the church is less crowded. About 40 worshipers are present. They are Italian: immigrants and brotherhoods are not present. Four middle-aged couples with dogs and without kids are present: two of them occupy the space near the entrance, while the other two take their place between the pews, in the middle of the church. The ceremony does not refer to animals: the reading from Saint Paul regards predestination, and the topic of the sermon is the controversy between Luther and the Catholic church. The ritual of the blessing is performed outside, in the churchyard.

The mass in Saint Agnes is different. It is a small, neo-gothic, three-nave church with a cozy atmosphere. The priest is very elderly and substitutes the parish priest, and worshipers encourage him with applause. Despite the crowd, the majority of the families with animals take seats in the main nave and in the lateral benches near the presbytery. The number of families with animals is higher than in Saint Anthony. Many kids are present, and music is performed by a religious pop band. Only the biggest dogs are kept near the entrance, to avoid disturbance. In spite of territoriality, the dogs are quiet; they could be accustomed to the presence of other animals. In the church, there is a coherent animal figurative isotopy:19 the statue of Saint Agnes holds a lamb in her arms; in a stained-glass window, Christ is depicted next to a lamb. As in Saint Anthony, the ritual of the blessing is performed in the churchyard.

4.3. Circumstances of Utterance

The animals present in Saint Anthony are exclusively dogs, while in Saint Agnes there is also one cat, locked in its crate. Due to the urban context, there are only pets, and no farm animals. As reported in other ethnographic descriptions, in the countryside, during Saint Anthony, agricultural tools are blessed too: “The spread of the rite is attested for the past in many European agro-pastoral realities and is even still present in several towns (…) even if motorized vehicles and/or domestic animals have often replaced the traditional working or breeding animals” (Pirovano 2003).

The circumstances of utterance play a mediation role in actualizing the content of a message: “In this connection between sentence and utterance (énoncé and énonciation), the addressee of any text immediately detects whether the sender wants to perform a propositional act or another kind of speech act” (Eco 1979, p. 16). According to Eco, the receiver of the message connects the received expression with the act of utterance and with the external environment. Depending on the latter, the semantic value of a given message can be antithetical. “Thus/aye/means ‘I vote yes’ in the framework of certain types of formal meetings and ‘I will obey’ in the framework of the Navy” (Eco 1979, p. 19).

In both the observations, the instrumental value associated with the animals is indeed present in the discourse of the priest, but it is softened (in Eco’s terms, it is narcotized). This effect is strengthened by the animals’ clothing. Except for large dogs, all the pets are dressed. During the vespers, a poodle wears two pink bows around its ears.

An important distinction concerns the way in which animals are referenced in the priests’ and in the family members’ speeches. While the priests do not speak directly to animals, avoiding humanizing them, family members assimilate pets to little babies, using a language of affection. For example, after the blessing in Saint Anthony, a woman asks her dog to be patient, since she wants to pray the crucifix. Gestures and caresses remind one of those made to keep well behaved those babies that are too small to participate in the ceremony. In Saint Agnes, this impression is strengthened due to the presence of many families with a child and a pet. While in Saint Anthony the ceremony is more intimate, in Saint Agnes, it is similar to a party: there is a religious pop band and a bench where commemorative medals are distributed to the babies.

4.4. The Blessing

4.4.1. Before the Blessing

In the parish of Saint Anthony, during the sermon of the vespers, the priest explains that human beings should pray for animals, since they do not have the gift of speech. In Saint Agnes, during the prayer intentions of the mass, animals are considered as instruments, a godsend. The intentions echo Saint Francis’ Laudes creaturarum. In the second case, the distance between humans and animals is wider, since the expression “to pray for” does not apply to tools or utensils.

4.4.2. The Rite of the Blessing in Saint Anthony

In the parish of Saint Anthony, the rite is performed according to the Benedizionale (1992, p. 34). The book can be described as a set of instructions to construct the rite, step by step:

- It provides some formulas, which can be seen as overcoded syntagms. According to Eco (1979, pp. 17, 19, 22), the term “overcoding” describes the correlation between given, ready-made expressions (single terms, sentences or entire textual sequences) associated with pieces of encyclopedic knowledge by rhetorical, stylistic or ideologic rules.

- The circumstance of utterance invites the celebrant to concatenate the syntagms and to fill the gaps. For example, a gap must be filled with the name of the saint called as intercessor.

- This way, the generated benediction is well formed. It is canonical and consistent; it is adequate to the circumstances; sacred values are actualized in compliance with Catholic theology.

In the classical semiotic perspective proposed by Hjelmslev (1961), the book can be seen as a metasemiotic, the function of which is to link the expression plane and the content plane of the benedictions. At the same time, the relation between the two planes is mediated by the circumstances of utterance and by cultural codes (rhetoric, theology, tradition …).

Of course, it is not possible to codify every circumstance. For this reason, as with every system, the Benedizionale contains different void squares (case vide) allowing diachronic change (Martinet 1952). In a classic structuralist perspective, one could say that these system gaps represent the condition of possibility of cultural change, since systems tend to fill the gaps to reach a balance. This point will be developed in the conclusion.

- At the beginning of the rite, the priest is on the stairs.

- As the deacons hold the book, he reads the passage (A):

(A) In the plan of God the Creator, even the animals that populate the sky, the earth and the sea participate in the human story. Providence, which embraces the entire scale of living beings, uses these precious and faithful friends of man and their image to signify the gifts of salvation. Saved from the waters of the flood by means of the ark, they participate in some way in the covenant pact with Noah20; the lamb recalls the paschal sacrifice and the liberation from slavery in Egypt; a large fish saves Jonah from shipwreck; the ravens feed the prophet Elijah; the animals, with men, are involved in the penance of Nineveh and with all creation they are part of the plan of universal redemption.

Let us therefore invoke God’s blessing [through the intercession of Saint Anthony]21 upon these creatures and, giving thanks to the Creator who has placed them at our service, let us ask to always be able to walk in his law and never to fail in our human and Christian dignity (Benedizionale 1992, p. 1065, Introductory monition).

- Then, the priest omits different parts of the rite and selects the prayer (B):

- (B) O God, source of all good,

- who in animals hast given us a sign of your providence

- and a help in our daily toil,

- through the intercession of Saint [Anthony]22

- grant that we may know how to make wise use of them,

- recognizing the dignity and limitations

- of our human condition.

- (Benedizionale 1992, p. 1073, Prayer of blessing).

- Before the blessing, the priest reads the passage (C):

- (C) Revive in us, O Father,

- in the sign of this holy water

- the adherence to Christ,

- the first fruits of the new creation

- and source of every blessing. (Benedizionale 1992, p. 1075, Prayer of blessing).

- Then, while the deacons await, the priest descends the church steps, approaches each dog, asks for their name and says hello, before blessing each of them. Apparently, water has already been blessed before the ceremony. Considering the syntagm (C) remembering the baptismal promises, the situation cannot but remind one of a baptism. Finally, the priest returns to the stairs and reads the formula (D):

- (D) May God, who created the animals of the earth

- as help and support in our earthly life,

- always protect and guard us.

- Together with the worshipers, the priest praises Christ, pronounces the invocation “Saint Anthony the Abbas, pray for us”, and greets bystanders.

4.4.3. The Rite of the Blessing in Saint Agnes

- In Saint Agnes, the churchyard is very crowded. The rite is longer and more articulated.

- The celebrants start the rite on the staircase.

- While the deacons shoot some photos with their tablets, the priest explains the medieval origin of the association between Saint Anthony and the pigs—providing the ritual with a meaning in terms of tradition. He remembers how different animals have their own patrons (e.g., Saint Martin protects horses).

- The priest reads Gn (2, pp. 19–20)23. The passage describes how Adam named the animals.

- The priest then reads the Introductory monition A, already reported in the previous section, associating Saint Agnes to Saint Anthony the Abbas in the invocation.

- The priest invites a volunteer to read the prayer of the faithful (Benedizionale 1992, p. 1071). The intentions recall many passages from the Scriptures. The final one seems interesting, since it refers to Saint Francis’ Laudes creaturarum:

- Blessed be You, Lord,

- for all Your creatures

- who invite us to sing Your praise.

In this manner, this intention of prayer establishes a relation between Saint Anthony the Abbas and Saint Francis. This nexus seems very important, since the Catholic church refounded his ecologist perspective on the Laudes creaturarum—see Section 3.

- Worshipers say the Lord’s prayer.

- The celebrant reads the alternative blessing formula (B), reported in the previous section.

- The celebrant reads the conclusive formula (D), invoking Saint Anthony.

- The celebrant descends and blesses the presents, humans and animals, collectively. As in the parish of Saint Anthony, water has already been blessed.

- Finally, the celebrant greets bystanders, inviting them to take the celebrative ribbons.

- The rite is followed by a collective song.

After the blessing, near a red table, multicolor ribbons are distributed with some bells. There is also a piggy bank for the offerings.

4.5. Comparison

The two ceremonies differ in many ways. The first is similar to a baptism: the syntagm (C) in the benediction echoes the renewal of the baptismal promises performed by parents during the baptism. The benediction is not collective: the priest benedicts each animal. The second ceremony and the collective blessing reveals a more traditional point of view on the relationship between humans and animals: by allowing Adam to name the animals, God grants him a power over lesser creatures and establishes a hierarchy. In semiotic terms, to give a name is a speech act, an action performed through language. The attitude toward animals in the parish of Saint Anthony is only apparently more conservative. Animals are located at the border of the sacred space; rites involving animals are performed in the evening, on weekdays. Despite all this, the ritual in Saint Anthony is more similar to a baptism than the one in the parish of Saint Agnes, even if animals are allowed to enter the sacred space during Sunday mass. In Saint Anthony, the blessing is individual and follows the utterance of the proper name of each animal, while, in Saint Agnes, humans and animals are addressed collectively. The text of the blessing in Saint Agnes recalls the performative speech through which Adam named animal species. This opposition between the collective and the individual focus causes the ceremony in Saint Agnes to resemble a blessing of objects more than a baptism.

4.6. Liminal Spaces

The frontier between internal and external space is crucial for two reasons: first, in plastic semiotics, this distinction is used to express categorial oppositions between abstract semantic values; second, according to Lotman, each culture draws this frontier in the world, classifying elements as internal and external. Thus, the frontier between the internal and the external space can be used to manifest a second, abstract opposition, between sacred and profane (Lotman 1975, pp. 104–6). At the same time, in folk narrative, the hero is the mobile element of the text, capable of crossing the border and of returning. This seems relevant to the present case: “the mobile heroes conceal within themselves the possibility of destroying the given classification and establishing a new one or of representing the structure not in its invariant essence but through its multifaceted variation” (Lotman 1975, p. 103). In a similar way, pets crossing the border between the external, profane space and the internal, sacred space challenges the traditional Catholic valorization of living beings.

4.7. Morphodynamic Transformations

In semiotic terms, the difference between the syntactic structures of the two ceremonies consists of a morphological change starting from the simpler structure of the ceremony in Saint Agnes. (On the semiotic notion of morphogenesis, see Sarti et al. 2014). First, let us recall the semiotic definition of actant: “An actant can be thought of as that which accomplishes or undergoes an act, independently of all other determinations (Greimas and Courtés 1982, p. 5)”. From this point of view, an actant is a type of syntactic unit. At the same time, in semiotic terms, syntax is generalized from the description of language to every kind of interaction involving action. The notion of actant is formal: actants are functions. Actants are embodied by actors of all kinds: “the concept of actant (…) applies not only to human beings but also to animals, objects, or concepts (Greimas and Courtés 1982, p. 5)”.

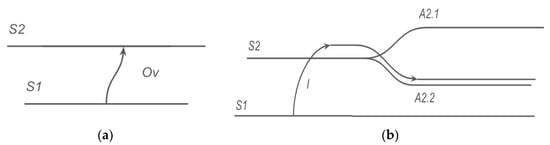

To represent the syntactic difference between the two rites, René Thom’s graphs can be useful (Figure 1). The syntax of the ceremony in Saint Agnes involves three actants: a first subject (embodied by the celebrant) transfers to a second subject (embodied by a collective actor formed by both humans and animals), a value through an object (holy water). The ceremony in Saint Anthony adds an extra dimension, involving four actants: using an instrument (embodied by the holy water), a first subject (the celebrant) splits a second subject (embodied by a collective actor formed by both humans and animals) into two different actants: the family and the blessed pet (Thom 1968).

Figure 1.

Two Thom graphs representing (a) the blessing in Saint Agnes as a catastrophe (in the mathematical sense) of the “gift” type; (b) the blessing in Saint Anthony as a catastrophe of the “ablation” type. S1 = “Priest”; S2 = “Collective actor consisting of both humans and animals”; Ov and I = “Holy water”; A2.1 and A2.2 = “Individual actors—blessed animals”. Thom’s graphs have been developed to represent the syntax of Tesniere’s bivalent and trivalent verbs.

5. Discussion

In Section 1.1, ethnosemiotics was defined as an inquiry into the conditions of the possibility of ethnography, identified, in turn, with the phenomenological conditions of sharing the same world by intersubjective instances such as humans, pets and a Creator. This is why the paper describes the spaces of the ritual in relation to the morphological relations between human beings and specific pets, trying to highlight how their meaning changes. This goal cannot probably be achieved other than in relation to a specific research question. In the present case, the hypothesis is that, in a culture which can generally be described, in Descola’s terms, as “naturalist”, one can find specific social discourses, practices and rituals, attributing specific human semantic traits to pets. This happens in urban contexts where the animal is not seen mainly as an instrument24 and is adopted by the family.

5.1. From Morphology to Meaning

The form of the ritual carried out in the parish of Saint Anthony reflects the modification of the family from a partitive to an integral totality: in the first model, the family is composed of different living beings (humans and nonhumans); in the second model, the status of human is, at least in part, granted to pets. The morphology of the rite changes accordingly: in the form adopted in the parish of Saint Agnes, it confers value to a partitive totality; in the form adopted in Saint Anthony, it gives value to a member of an integral totality25. This reading is reinforced by the fact that in Saint Agnes many children are present, while in Saint Anthony, only adult couples with pets participate in the ritual. The rite in Saint Anthony is not addressed to young participants. While, for example, in some Italian parishes, a specific Sunday mass is adapted for children and takes place in the morning, the vespers do not try to involve children as regards the sermon or the choice of songs. The blessed pets in Saint Anthony are not just playmates for babies; they are part of the family. Of course, the traditional text of the ritual still reflects the western naturalism and its rigid frontier between human and nonhuman and the subordination of the second to the first: animals are instruments and a gift of God. However, the morphology of the ritual resembles a baptism, thanks to the void squares (case vide) in the system of the Benedizionale (see above, Section 4.4.2).

5.2. Cultural Change as Friction of Codes

This conclusion can be counterintuitive. The parish of Saint Agnes seems more progressive in the style of the mass: from an aesthetic point of view, it is more pop, and pets are accepted between the benches. Furthermore, in the parish of Saint Anthony, animals are confined in liminal spaces and times. Here, innovation is freer; as Lotman (2009) writes, the innovation of codes occurs at the border of the semiosphere, leading to friction with the codes of the kernel. In particular, the friction concerns the ritual and the textual part of the blessing, which strongly subordinates animals to men by referring to the Book of Genesis. However, the opposition between animal and man is somehow weakened and moved to the background, since the opposition between creator and creature is highlighted. This effect is achieved also by referring to Saint Francis’ Laudes creaturarum, the bases of the new Catholic ecologism promoted by Pope Francis.

5.3. An Incomplete Change of Ontology

The ritual confers upon pets an intermediate status. Since it mirrors a baptism, pets are somehow infantilized. In this way, they are still kept in a subordinate role: they will never become adults as it regards the sacraments. This feature seems important to distinguish the weakened naturalism of urban culture from animism. To exemplify his definition of animism, for example, Descola writes that Siberian hunters used to attribute a human status to their prey; a shift to analogism occurred with domestication and animal protection (Descola 2013, pp. 365–90). The weakening of the rigid frontier between humans and animals and the graduality of the interior qualities which distinguish each animal tend toward analogism. After all, according to Descola (2013, pp. 202–7), western culture became naturalist only in recent times, from the 18th century; previously, at least from the time of Plato, western culture was analogist. Probably, this periodization does not exclude that naturalist, analogist and even animist points of view can coexist in our culture, depending on the circumstances in which the human–animal relation is enunciated (e.g., religious/secular; urban/rural; scientific/popular). To realize this, it should suffice to think of Disney movies.

5.4. Human and Animals: A Semantic System

The graduality of the distinction between humans and animals seems confirmed by the collected ethnographic data: the great majority of the blessed animals are small dogs. There are a good number of big dogs and only one cat. Other domestic animals were absent: hamsters, birds (although some of them, such as the Ara parrots, can be involved in deep emotional relations with humans), turtles, iguanas, snakes, spiders. Let us consider that the animals represented in the poster of the ceremony in the parish of Saint Agnes include a fish in the bow, a canary, different rodents, two frogs and a rabbit, not present at the blessing.

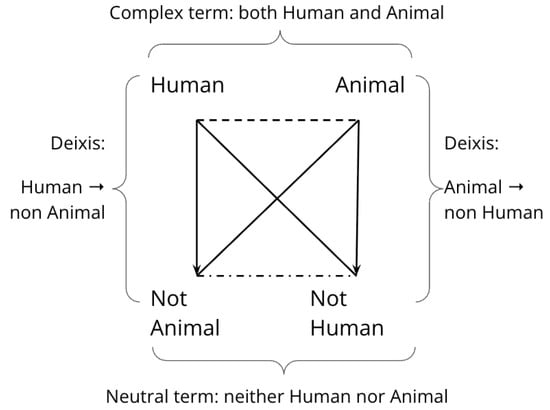

It is possible to represent the situation with a classic semiotic square (Figure 2, Greimas and Courtés 1982):

Figure 2.

A semiotic square representing the Human vs. Animal category.

Traditional Catholic theology distinguishes between humans and animals (e.g., lizards, rats, salmon) and does not foresee nuances, which can be seen, in semiotic terms, as complex terms subsuming the whole category (“both human and animal”). In our observations, they are embodied by pets, especially dogs. The absence of complex terms is the void square in the Catholic system. The presence of this gap is the condition of possibility of diachronic change, since, according to Martinet (1952), the system tends toward balance. For this reason, the hiatus between culture, progressively recognizing the nuances between human beings and animals, and Catholic tradition led the second to reduce, in recent times, the distance, without changing the theological frame: “Other texts, however, admit that animals also have a vital breath or breath and that they have received it from God. In this respect, man, who came from the hands of God, appears to be in solidarity with all living beings” (Wojtyła 1990). In its text, Pope John Paul II quotes Psalm 104:27–30 and concludes: “The existence of creatures therefore depends on the action of the breath-spirit of God, who not only creates, but also preserves and continually renews the face of the earth”.

5.5. Semantics Is Not Ontology

From a semiotic point of view, it is not surprising how the hierarchy between human and nonhuman animals can be crossed and discussed by attributing human semantic values to animals and vice versa. As Umberto Eco (1984, pp. 46–86) writes, in a tree-classification system, the decision on what is considered hypernym or hyponym is conventional: semantics is not ontology. From an encyclopedic point of view, humans, plants, gods and animals are interconnected in a net of semantic features, allowing the creation of different classifications: “A natural language is a flexible system of signification conceived for producing texts, and texts are devices for blowing up or narcotizing pieces of encyclopedic information” (Eco 1984, p. 80). Ethnosemiotics develops this concept by generalizing it to different semiotic systems, such as rituals, and by individuating the device that allows recombining the involved semantic values in the relation between utterance and circumstances.

To conclude, the current practices studied during the feast of Saint Anthony seem to actualize a set of values that cross the cultural history of Christianism, finding a more central or peripheral place in the semiosphere across time and in different cultural contexts. These values find an early and embryonic formulation in the early writings surrounding Saint Anthony, know a relevant development in the Franciscan sources, and appear central today, when the relationship between humans and animals is undergoing a deep change that challenges radical taxonomies and allows one to hypothesize that animals will be growingly accepted as constitutive parts of enlarged religious communities that can already be observed in germ.

Author Contributions

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Angelica Federici for her support in reviewing and editing the final version of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This prohibition has not been directly observed. However, it is present in the ceremony program of different parishes. For example, https://sguardisutorino.blogspot.com/2024/01/domenica-21-gennaio-giorno-dedicato.html?fbclid=IwAR2kXM0rRQx_lqdEF-VP49VYUMfNJB8i73ATFuCGIwaU64w1fBCIbUHSmpk&m=1 (accessed on 10 July 2025). |

| 2 | On these sources, see Cremaschi (1995) and Baldi (2015). |

| 3 | To name just two examples, Abt-Baechi (1983) proposes a psychological reading of the archetypal elements associated with the Saint that may explain the enduring appeal of his figure, while Leone (2020) reconstructs the intertextual and intermedial relationships between different representations of Anthony and shows how this figure, particularly through the mediation of Flaubert, has been represented by Barthes, Foucault and other relevant 20th-century intellectuals. |

| 4 | On the modelization of sanctity, see, for instance, Ponzo and Galofaro (2024). |

| 5 | Di Nola (1976, pp. 208–10, 242–44), for instance, observes the ambivalent features of Anthony’s character: on one hand, a hermit and a terrible authority that can punish sacrilegious acts and immoral behaviors and, on the other hand, a benign and hilarious old peasant, protecting the faithful and mocking and tricking the demons. |

| 6 | The English translation for this and the following passage is taken from https://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/03d/0295-0373,_Athanasius,_Vita_Antonii_[Schaff],_EN.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025). |

| 7 | Even when Anthony and his companions have to cross a canal full of crocodiles, his prayer is enough to overcome the obstacle peacefully (Athanasius of Alexandria 2015, chp. XV). |

| 8 | See in this respect Ponzo (2024), Caprettini (1974) and Roche (1948, chp. 7). |

| 9 | https://www.vatican.va/content/paul-vi/it/apost_letters/documents/hf_p-vi_apl_19710514_octogesima-adveniens.html (accessed on 10 July 2025). |

| 10 | https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/it/apost_letters/1979.index.html (accessed on 10 July 2025). |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | For some semiotic reflections about these issues, see, e.g., Ventura Bordenca (2018) and Marrone and Mangano (2018). |

| 14 | E.g., https://www.diocesi.torino.it/site/cani-in-chiesa-rispetto-e-buon-senso/ (accessed on 10 July 2025); https://www.famigliacristiana.it/articolo/i-cani-possono-entrare--in-chiesa-il-parere-dei-lettori.aspx (accessed on 15 November 2024). |

| 15 | E.g., https://it.aleteia.org/2015/06/26/durante-la-messa-si-possono-portare-in-chiesa-animali-domestici (accessed on 10 July 2025). |

| 16 | |

| 17 | Cf. for instance: https://www.repubblica.it/vaticano/2024/09/27/news/papa_francesco_cani_gatti_bambini-423520624/ (accessed on 10 July 2025); https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-59884801 (accessed on 10 July 2025). |

| 18 | Fire is also blessed in the Easter rite. The fire used to light the Easter candle is also blessed first. |

| 19 | An Isotopy is a coherent semantic layer of reading. See Greimas and Courtés (1982). |

| 20 | The Benedizionale reports the references to the Bible: Noah (Gen 9:9–10); the lamb (Exodus 12:3–14); Jonah (Jonah 9:9–10); Elijah (1 Kings 17:6); and the penance of Nineveh (Jonah 3:7). |

| 21 | The Benedizionale leaves to the celebrant the choice of the appropriate saint. |

| 22 | See n. 17. |

| 23 | The Benedizionale (1992, pp. 1066–67) allows the priest to choose between the two alternative tales of the creation reported in Gn. The other possible (and longer) reading is Gn (1:20–28). |

| 24 | Actually, we do not want to claim that in this urban context animals are seen only as pets; indeed, animals can still be seen as food as well as instruments, but, in the considered cases and contexts, the consideration of animals as pets was undoubtedly predominant. |

| 25 | The opposition between integral and partitive totality was proposed by Greimas (1976). |

References

- Abt-Baechi, Regina. 1983. Der Heilige und das Schwein. Zuerich: Daimon Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony the Great. 1995. Detti-Lettere. In Athanasius of Alexandria, Vita di Antonio, Antonio Abate Detti-Lettere. Edited by Lisa Cremaschi. Milan: Paoline, pp. 223–85. [Google Scholar]

- Athanasius of Alexandria. 2015. Vita di Antonio. Edited by Davide Baldi. Rome: Città Nuova. [Google Scholar]

- Baldi, Davide. 2015. Introduzione. In Athanasius of Alexandria, Vita di Antonio. Edited by Davide Baldi. Rome: Città Nuova, pp. 5–31. [Google Scholar]

- 1992. Benedizionale; Roma: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Available online: https://liturgico.chiesacattolica.it/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2022/04/08/Benedizionale-DEFINITIVO-.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Bertetti, Paolo. 2013. Lo Schermo Dell’apparire. Bologna: Esculapio. [Google Scholar]

- Caprettini, Gian Paolo. 1974. San Francesco, il lupo, i segni. Turin: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Cremaschi, Lisa. 1995. Introduzione. In Athanasius of Alexandria, Vita di Antonio, Antonio Abate Detti-Lettere. Edited by Lisa Cremaschi. Milan: Paoline, pp. 9–102. [Google Scholar]

- Del Ninno, Maurizio. 2007. Etnosemiotica: Questioni di Metodo. Roma: Meltemi. [Google Scholar]

- Descola, Philippe. 2013. Beyond Nature and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Di Nola, Alfonso M. 1976. Gli Aspetti Magico-Religiosi di una Cultura Subalterna Italiana. Turin: Boringhieri. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, Umberto. 1979. The Role of the Reader. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, Umberto. 1984. Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fenelli, Laura. 2006. Il Tau, il Fuoco, il Maiale. I Canonici Regolari di Sant’Antonio Abate tra Assistenza e Devozione. Spoleto: Fondazione Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo. [Google Scholar]

- Fenelli, Laura. 2011. Dall’eremo Alla Stalla. Storia di Sant’Antonio Abate e del suo Culto. Rome and Bari: Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Galofaro, Francesco. 2022. Appunti di pellegrinaggio. Il turismo religioso e l’etnosemiotica. E/C 35: 163–78. [Google Scholar]

- Galofaro, Francesco. 2024. L’osservazione partecipante: Sul problema degli osservabili in etnosemiotica. E/C 41: 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Giorda, Mariachiara. 2008. La paternità carismatica di Antonio. In Direzione Spirituale e Agiografia: Dalla Biografia Classica alle vite dei Santi Dell’età Moderna. Edited by Michela Catto, Isabella Gagliardi and Parrinello Rosa Maria. Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso, pp. 39–65. [Google Scholar]

- Greimas, Algirdas J. 1976. Sémiotique et Sciences Sociales. Paris: Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Greimas, Algirdas J., and Courtés Joseph. 1982. Semiotics and Language an Analytical Dictionary. Edited by Thomas A. Sebeok. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hjelmslev, Louis. 1961. Prolegomena to a Theory of Language. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leone, Massimo. 2020. Form and Force of the Sacred: A Semiotic Study of the Temptations of Saint Anthony. In Sign, Method and the Sacred: New Directions in Semiotic Methodologies for the Study of Religion. Edited by Jason Cronbach Van Boom and Thomas-Andreas Põder. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 267–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lotman, Juri. 1975. On the Metalanguage of a Topological Description of Culture. Semiotica 14: 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotman, Juri. 2009. Culture and Explosion. Berlin and New York: Mouton De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Marrone, Gianfranco, and Dario Mangano. 2018. Semiotics of Animals in Culture: Zoosemiotics 2.0. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Marsciani, Francesco. 2007. Tracciati di Etnosemiotica. Milano: Franco Angeli. [Google Scholar]

- Marsciani, Francesco. 2020. Etnosemiotica: Bozza di un manifesto. Actes Sémiotiques Online 123: 1–12. Available online: https://www.unilim.fr/actes-semiotiques/6522 (accessed on 10 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Martinet, André. 1952. Function, Structure, and Sound Change. Word 8: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrini, Chiara. 2021. La Pratica Religiosa al Tempo del Coronavirus. Bologna: Esculapio. [Google Scholar]

- Pirovano, Massimo. 2003. Sant’Antonio Abate: La Festa a Brivio e la Devozione Diffusa. Brivio: Comitato Festeggiamenti Burg di Tater. [Google Scholar]

- Ponzo, Jenny. 2024. Saintly animals: A semiotic perspective on changing models of sanctity and personhood. Ocula 31: 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ponzo, Jenny, and Francesco Galofaro. 2024. Semiotics and the representation of holiness. Ocula 25: 1–116. [Google Scholar]

- Roche, Aloysius. 1948. A Bedside Book of Saints. London: Burns Oates & Washbourne Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Sarti, Alessandro, Federico Montanari, and Francesco Galofaro. 2014. Morphogenesis and Individuation. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Thom, René. 1968. Topologie et signification. L’age de la Science 4: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura Bordenca, Ilaria. 2018. Martyrdom in contemporary animalist discourse. Lexia 31–32: 315–36. [Google Scholar]

- Viveiros de Castro, Edoardo. 2014. Cannibal Metaphysics. Minneapolis: Univocal Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wojtyła, Karol. 1990. Udienza Generale del 10 Gennaio. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/it/audiences/1990/documents/hf_jp-ii_aud_19900110.html (accessed on 10 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).