Abstract

While extant research has centered religious microaggressions in therapeutic contexts, there has been little research on non-religious populations in psychotherapy, although evidence suggests the presence of negative therapeutic encounters for this minoritized population. The purpose of the current study was to both quantify and explore the prevalence of non-religious microaggressions in therapy and to identify their impact on the therapeutic working alliance and therapeutic continuity. Utilizing a mixed-methods approach, participants (N = 120) were asked to report on religious/spiritual (R/S) conversational contexts and behaviors in their most recent therapeutic relationships. Quantitative analyses revealed that almost half of our participants experienced non-religious microaggressions from their counselor (e.g., assumptions about client religiosity, endorsing stereotypes, etc.)—which significantly impacted the continuation of therapy as mediated by therapeutic working alliance. Qualitative conceptual analyses showed a significant presence of counselor avoidance of R/S topics and, when discussed, negative client experiences. Suggestions for the importance of standardizing R/S clinical training are discussed alongside the unique nature of being non-religious within a predominantly religious country.

1. Introduction

Atheists are among the least trusted groups of people in the United States, with data from nationally representative surveys indicating strong, persistent anti-atheist moral concerns when compared to other ‘cultural outsider’ groups (Edgell et al. 2016). While decades of U.S. polling indicate negative social attitudes towards atheists, researchers have specified that the negativity appears detached from the social category “atheist” and attached to the general idea of ‘non-belief’ (Swan and Heesacker 2012). Openly identifying as non-religious is relatively uncommon in the U.S.: only about 17% of Americans use the term “atheist” for themselves (Pew Research Center 2024), although approximately 28% report no religious affiliation. Some analysts suggest that the true number of atheists is higher than reported (around 20%) when accounting for those reluctant to adopt the label (Gervais and Najle 2018). This discrepancy in identification and prevalence likely reflects stigma: many non-believers conceal their secular identity to avoid social disapproval (Abbott et al. 2020, 2022).

The United States remains a religious and spiritual outlier among other industrialized nations, maintaining a high level of religiosity even as secularism rises globally (Norris and Inglehart 2004; Public Research Religion Institute 2021). However, the U.S. has not been able to escape global patterns: younger generations of Americans report much higher rates of non-religiosity when compared to previous generations (Twenge et al. 2015), perhaps indicating a generational swing towards secularism or, at the very least, religious disaffiliation. Still, fear of social and professional backlash may dissuade many from being open about their lack of belief (Abbott and Santiago 2023). These concerns are not unwarranted: openly non-religious individuals often face discrimination or unequal treatment—including social, workplace, and military discrimination (Cragun et al. 2012) and familial rejection (Zimmerman et al. 2015)—highlighting the personal costs of being ‘outed’ as a non-believer.

1.1. Discrimination Against the Non-Religious

Stereotypes persist about atheists being “non-conformist, skeptical, cynical, and joyless” individuals due to the assumption that atheists find life to be meaningless—stereotypes that do not hold up to empirical inquiry (Caldwell-Harris et al. 2011, p. 1). Regardless, this negativistic stereotyping is harmful to non-believers, as the preconceived notions can damage relationships before they begin. Discrimination against non-believers exists in many cultures, and atheists are commonly one of the more distrusted groups in our global society: the 2024 edition of the Freedom of Thought Report indicated that blasphemy laws exist in 91 countries, affecting 57% of the global population (Humanists International 2025). Reportedly, leaving a religion is punishable by imprisonment in 60 of those countries, with another 12 implementing the death penalty for those non-believers who disaffiliate from their religion. This is exemplified by the standing belief that non-religious individuals are more commonly associated with anti-social behaviors, such as murder or bestiality (Grove et al. 2019). A tertiary analysis of the literature indicates that the moral distrust of atheism has a long history with cultural perpetuity in the United States (Dabbs and Hutchins 2024).

Due to the frequency of stereotyping and fear of discriminatory practices, atheists tend to be more reserved in revealing their non-believer identities (Burris 2022). However, the choice to conceal one’s non-believer identity comes with a cost. Outcomes for non-religious individuals who actively conceal their identities include lower levels of psychological and physical well-being, and the inverse is true for those who disclose their identity (Abbott and Mollen 2018). Thus, while benefits and opportunities may be lost by revealing a non-believer identity, actively concealing this identity can be exhausting and will likely lead to negative outcomes through micro- and macro-level discrimination.

1.2. Microaggressions: Basic Concepts

The conceptual origins of microaggressions in the United States are related to racism. Overt acts of racism are less likely to be explicit (macroaggressive) and are often exhibited through subtle remarks and behaviors (Trusty et al. 2022). These comments and behaviors, while covert and oftentimes unintentional, are nonetheless harmful due to their frequency in everyday interactions and the negative cumulative psychological impact (Cheng et al. 2018). The microaggression construct has been extrapolated beyond race to include ethnicity, sex, gender, religion, age, ability status, body size, and a host of other social demographic and identity factors. Of particular interest in the current study is the way in which non-religious (secular) identity fuels microaggressive behaviors in the predominantly religious U.S.

Perhaps the earliest iteration of psychometric interest in studying non-religious microaggression in recent history includes the development of two separate atheist-specific scales: the Scale of Atheist Microaggression (SAM; Pagano 2015) and the Measure of Atheist Discrimination Experiences (MADE; Brewster et al. 2016). Both of these scales, while different in their development and constructs of interest, centered on the reality of atheist discrimination in North American contexts. Furthering this pattern, researchers expanded the atheist-specific microaggression umbrella to include non-believers (atheists, agnostics, “nones,” etc.). Cheng et al. (2018), in developing the Microaggressions Against Non-Religious Individuals Scale (MANRIS), found that experiencing non-religious microaggression was a significant predictor of depressive symptomatology in participants. Despite the demonstrated negative effects of microaggressions against non-religious individuals, there is a dearth of research on the subject. While there has been a rapid growth of racial microaggression research since the publication of Racial microaggression in everyday life (Sue et al. 2007), there has been little focus on microaggressions against non-believers, especially within the context of psychotherapy.

1.3. Religiosity and Mental Health Counselors

Evidence for discrimination against non-believers is naturally reflected in the psychotherapeutic practice of mental health counselors (MHC). MHCs are trained to regard all client beliefs, despite personal perspectives, including spiritual or religious beliefs (D’Andrea and Sprenger 2007). However, there does seem to be an implicit positive bias towards religious or spiritual stimuli compared to nonreligious or atheist stimuli using the Implicit Association Test (IAT) (Winkeljohn Black and Gold 2019). These researchers found that implicit, negative associations between client attributes and nonreligious stimuli seem to reflect negative perceptions of nonreligious people in the media. Implicit biases against nonreligious people might drive counselors to treat nonreligious clients differently from religious clients.

Generally, both religious and non-religious clients have noted poor interactions in therapeutic settings regarding their religiosity. Non-religious clients reported a range of experiences: 36% of MHCs starting unwanted religious dialogues and 29% explicitly recommending religious-based interventions (Byrne 2021). This therapeutic approach affected the therapeutic alliance and overall efficacy of treatment, with non-religious clients reporting feeling targeted by MHCs with strong religious beliefs (D’Andrea and Sprenger 2007) and feeling invalidated about their non-religious status. A case study from Jahangir (1995) outlines techniques to alleviate symptoms of psychopathology by encouraging atheist clients to re-establish their connection with God—perhaps indicative of general attitudes in the mental health fields of the therapeutic necessity of religion. Differences emerge in clinical efficacy due to MHC (in)ability to respond effectively to religious attitudes and adapt treatment to individual religious values (D’Andrea and Sprenger 2007).

1.4. Current Study and Guiding Theory

Recent scholarship in the realm of clinical efficacy has pointed to the working alliance (also called the therapeutic alliance) as a quintessential component in the success of psychotherapy (Stubbe 2018). This is not new information: metanalysis dating back nearing 35 years have pointed to the reliable impact that working alliance has on therapeutic outcomes (Horvath and Symonds 1991). Working alliance is operationalized in different ways but is characterized by a tripartite model of relational collaboration, affective bond, and client/professional agreement on direction of therapy (Stubbe 2018). In general, the more trust, respect, and collaboration exist within a therapeutic relationship, the better the outcome. In this way, microaggressive experiences could harm the connection between client and therapist, causing ruptures and impasses to relational formation or continuity.

The therapeutic relationship is one in which client identities may remain hidden unless purposefully broached and bridged by their clinician (Lee et al. 2022). For minority-identified clients, the broaching of cultural topics is strongly predictive of working alliance and therapeutic satisfaction (Depauw et al. 2023). However, performed insensitively or without the appropriate training, the therapeutic relationship could become a microcosmic mirror to the same discrimination and bias that the client experiences towards their concealable stigmatized identity outside of the helping relationship (Abbott and Mollen 2018).

The current study aims to expand on results found by Trusty et al.’s (2022) investigation into religious microaggressions in psychotherapy by adapting and extending its methodology to apply to the non-religious population. Based in the theories of Concealable Stigmatized Identity and Working Alliance, the current study seeks to (a) quantify the prevalence of microaggressions against non-religious people in psychotherapy, (b) test associations between non-religious microaggression and strength of the therapeutic working alliance, (c) explore the impact of microaggressions on therapeutic continuity, and (d) explore the nature of non-religious microaggressions in psychotherapy. Similarly to Trusty et al. (2022) hypotheses regarding religious clients, we hypothesize that microaggressions against the non-religious will be negatively associated with the therapeutic working alliance and therapeutic continuity.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a mixed-method approach utilizing both quantitative analyses and conceptual content analysis to understand our prevalences and relationships of interest.

2.1. Participants and Sample Size

We recruited participants in the current study via Prolific, a vetted online research participant database, using a standard U.S.-based sample. Participants were included in the study if they were over the age of 18 and met the following Prolific prescreen verifications: (a) non-religious identity (including agnostic, atheist, irreligious, naturalist, or none/rather not say), (b) religious affiliation (including non-religious, agnostic, atheist, no religion, and paganism), and (c) involved in mental health treatment (including psychological therapy and participating in your own care). From Prolific, participants were taken to a Qualtrics survey, which presented an informed consent process. All participants (N = 120) resided in the United States with a mean age of 36.63 years (SD = 10.66; range 20–75). While we had a total of 139 participants, 19 were removed for incomplete data. Our participant demographics skewed White (82.5%), previously religious (57.6%), presently irreligious (99.2%), college educated (89.2%), and female (50.8%). Complete demographics can be found in Supplementary Table S2.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Microaggressions Against Non-Believers

The prevalence and types of microaggressions against non-believers were measured through scores on both the Microaggression Against Non-Religious Individuals Scale (MANRIS; Cheng et al. 2018) and the Racial Microaggression in Counseling Scale (RMCS; Constantine 2007), adapted to measure non-religious microaggressions. The MANRIS is a 31-item questionnaire that measures microaggressions across five subscales: assumptions of inferiority, denial of non-religious prejudice, assumptions of religiosity, endorsing non-religious stereotypes, and pathology of a non-religious identity. Items on the MANRIS included such statements as “others have assumed that I would be selfish because of my lack of religion,” and “others have dismissed my experiences as a non-religious individual to be an overreaction.” Questions were anchored by five numeric options: never, 1–3 times, 4–6 times, 7–9 times, and 10 or more times. For the purposes of our study, we changed the language of the MANRIS to read “my counselor” instead of “others” to prime the counseling relationship (e.g., “my counselor has assumed that I would be selfish because of my lack of religion”). Internal consistency and reliability analysis for the MANRIS in our study showed favorable results (α = 0.93).

The Racial Microaggressions in Counseling Scale (RMCS; Constantine 2007) was also used as a redundant measurement for microaggression due to its use in the work by Trusty et al. (2022), of which the current work has based some of its method. The RMCS is a 10-item questionnaire that measures instances of topical exchange that could take place in the counseling relationship, with items such as “my counselor avoided discussing or addressing racial issues in our session(s),” and “my counselor sometimes was insensitive about my racial group when trying to understand or treat my concerns or issues.” We adapted the wording of this measure to prime religion instead of race (e.g., “my counselor avoided discussing or addressing religious issues in our session(s)”). The RMCS is anchored with three response options per question: this never happened to me, this happened, but it did not bother me, and this happened, and I was bothered by it. Internal consistency and reliability analysis for the RMCS in our study showed favorable results (α = 0.84).

2.2.2. Working Alliance

The Working Alliance Inventory–Short Revised (WAI-SR; Hatcher and Gillaspy 2006) was used to assess alliance strength between non-believer clients and their counselors. The revised scales’ selection was due to its implementation by Trusty et al. (2022), as well as the scales’ brevity. The WAI-SR is a 12-item questionnaire measuring the perceived strength of the relationship between client and mental health counselor via three subscales: task, goal, and bond. These subscales assess perceived agreement on therapeutic tasks (Tasks), agreement and accuracy of therapeutic goals (Goals), and strength of the interpersonal relationship between client and counselor (Bond), respectively. Items on the WAI-SR included such statements as “my counselor and I are working towards mutually agreed upon goals,” “I feel that the things I do in therapy will help me to accomplish the changes that I want,” and “my counselor and I respect each other.” For the purposes of our study, we filled in the blank items with “my counselor” rather than instructing participants to substitute the blank items with their counselor’s name. Questions were anchored by a 7-point Likert-like scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Internal consistency and reliability analysis for the WAI-SR in our study demonstrated favorable results (α = 0.94).

2.2.3. Therapeutic Continuity

Therapeutic continuity was measured through three questions concerning intent to continue the participants’ most recent therapeutic relationship. These questions included: “I wanted to continue the therapeutic experience with this mental health counselor,” “I considered discontinuing my therapeutic experience many times,” and “How long did you continue the therapeutic experience with this mental health counselor?” The first two questions were measured on a seven-point Likert-like scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ while the second was measured on a seven-point Likert-like scale from ‘less than one month’ to ‘more than one year.’ Due to its inverse nature, the second question was reverse-coded, and then a composite score was created to obtain a total therapeutic continuity score, which was used in all analyses.

2.3. Qualitative Analysis

Survey Questions

Survey questions were developed through an iterative process to better understand the realities of the irreligious in psychotherapy. Previous research in this area suggests chronic dismissal of irreligious identities (Abbott 2021; Khanolkar 2024); thus, questions were framed around exploring this reality. Question development took place in a laboratory setting, comprising the authors of the current manuscript and laboratory assistants, using an iterative approach to defining the concepts of interest. After three rounds of conceptual refinement, the following questions were developed and presented to participants:

- Please spend one minute expanding on the similarities or differences between how your counselor treated you due to your non-religious identity and how people in your daily life treat you because of your non-religious identity.

- Please describe your experience(s) of instances when religion was avoided as a topic of discussion during therapeutic settings. Was a conversation about religion ever initiated by the therapist or you? If so, was the discussion overall positive or negative for your therapeutic experience?

- Describe a situation where you felt that your therapist treated you in a way that made you uncomfortable because of discrimination towards or stereotypes about the non-religious.

2.4. Procedures

All participants in the current study completed an informed consent process approved by the corresponding author’s Institutional Review Board. The informed consent described the purpose of the study to the participants, noted potential risks, and inclusion criteria. It also informed participants that they were free to leave the study at any time and the repercussions for doing so (i.e., no monetary compensation). The median participation time was 13 min and 56 s, and participants were paid the equivalent of $17.22/h.

Our study was divided into two main components. The first was a series of quantitative psychometrics concerning experiences of microaggressions and working alliance. The second was a series of short-answer qualitative questions asking participants to elaborate on specific instances of microaggression (if faced) and therapeutic experiences. Qualitative questions were structured such that participants were presented with a one-minute timer and were not permitted to advance the survey until the timer had expired—we engaged in this practice to facilitate data-dense qualitative responses. We presented participants with questions 1–3 above, although only a subset of participants (n = 58) completed question two, as it was presented through survey logic. Participants were selected for question two if they reported having experiences of psychotherapeutic avoidance of religious topics.

Throughout the survey, we implemented two attention checks structured such that if participants missed the first, they were met with a notice that they had just missed an attention check and informed that, if they missed another, their survey would close. If they then missed the second attention check, their survey ended. No participants were excluded from the study due to failed attention checks, indicating investment in the survey process.

2.5. Data Analysis

Each participant’s responses were coded in full by three coders with varying personal religious and spiritual views. The team of coders remained consistent throughout the analysis process. Due to an interest in quantifying the presence and experiences of our irreligious participants, we analyzed each response using a conceptual content analysis procedure that revolved around our iteratively developed concepts of interest (and, transitively, the questions we asked participants). Two coders utilized Excel for their coding process, while one coder utilized NVivo v. 15.2.1.

Through our a priori method, we developed seven top-level concepts of interest by question:

- Question 1

- Negative experiences

- Instigated by the participants’ counselor

- Instigated by someone besides the counselor

- Instigated by both

- Tolerant counselor behavior

- Question 2

- Conversation initiation and subjective experiential direction

- Counselor-initiated (positive or negative experience)

- Self-initiated (positive or negative experience)

- Experiences of counselor avoidance of religious/spiritual topics

- Question 3

- Stereotype/prejudice experiences

- Discriminatory experiences

- Never experienced the above

While the above were our concepts of interests, another concept regularly emerged as coders engaged in the process: the concept of irrelevance. That is, within questions one and two, participants regularly noted that they did not have these experiences because religion was just not relevant or important to their lived experience in any way, and, therefore, it did not come up within or outside of therapy. Because of the prevalence of this experience, we added two a posteriori concepts of ‘irrelevance’ to our coding for questions one and two. Combined, we coded for nine top-level concepts in our analysis.

Rules for coding were straightforward, given the concepts for which we were coding and the ways we asked participants to engage around these concepts (e.g., to denote whether an experience was positive or negative). To code instances of stereotype, discrimination, and prejudice, coders agreed to use those definitions provided by the American Psychological Association Dictionary of Psychology (American Psychological Association n.d.). We used Fleiss’ kappa to measure the inter-rater agreement between our three coders, alongside the narrative classification guidelines reported by Altman (1999) (as cited by Laerd Statistics 2019). We present the frequencies of conceptual presence as an averaged percentage of ratings across our three raters. This method led to good strength of agreement, as elaborated upon in Section 3.

3. Results

Analyses for the current data included both quantitative and qualitative analyses required to address our stated research questions: exploratory differential methods, mediation analyses, and conceptual content analysis were used to assist in our understanding of our participants’ experiences.

3.1. Prevalence of Microaggressions Against Non-Religious in Therapy

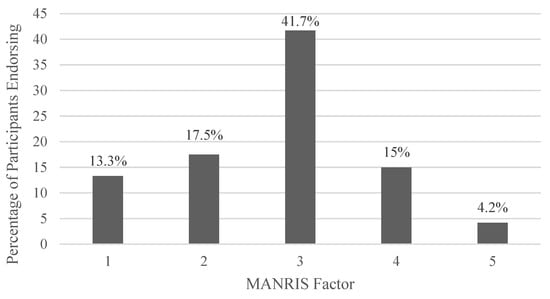

Total MANRIS scores in the current study ranged from 0 to 35 (possible range: 0–124), with at least one instance of non-religious microaggression endorsed by 45% of participants. The three most endorsed MANRIS items included: “my counselor assumed I was religious” (Q17; 8.3%), “my counselor assumed I attend places of worship without first asking if I’m religious” (Q18; 4.2%), and “my counselor told me to express thanks to God or Gods for an event” (Q20; 4.2%). These three most-endorsed questions comprise a portion of the third factor of the MANRIS: Assumptions of Religiosity. Of the five MANRIS factors, the third factor was the most endorsed (by 41.7% of participants). In comparison, the next most endorsed, Factor 2, was endorsed by 17.5% of participants. Complete factor endorsement rates can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Endorsement Rates of Non-Religious Microaggression Factors in Psychotherapy. Note: N = 120. Bars represent the percentage of participants who endorsed at least one item within each factor of the Microaggression Against Non-Religious Individuals Scale (MANRIS). Factor endorsement was defined as any score greater than zero on the respective factor subscale. Factor 1: Assumption of Inferiority; Factor 2: Denial of non-religious prejudice; Factor 3: Assumptions of religiosity; Factor 4: Endorsing non-religious stereotypes; Factor 5: Pathology of non-religious identity.

Participants were asked to compare their experiences regarding their non-religious identity in their therapeutic relationship with that of their general life by use of a slider mechanism (where 0 = not similar in the slightest to 100 = completely the same experience). Percentile exploration indicated that the range of scores skewed towards the upper limit, with the 50th percentile encompassing scores of 75 or greater (n = 65). To elaborate on this quantitative score, participants were asked to write for one minute about their experiences of being non-religious in their everyday life as compared to their therapeutic relationship (Q1).

Interrater reliability analysis with Fleiss’ kappa for the concepts of import for Q1 ranged from moderate agreement about Avoidance (κ = 0.53, p < 0.001) to good agreement about Tolerant Counselor Behavior (κ = 0.74, p < 0.001). Complete inter-rater agreement statistics can be found in Supplementary Table S1. Overall, participants endorsed negative experiences with their irreligious identities outside of therapy with a much higher frequency than within therapy (33.3% and 2.2%, respectively). Five participants (4.2%) indicated negative experiences both inside and outside therapy. Relatedly, 23.3% of our participants described experiences of tolerant counselor behaviors regarding their irreligious identity. Around 35% of our participants noted that conversations of religiosity or spirituality did not occur inside or outside of therapy for a variety of factors (e.g., therapist irreligion, participant irreligion, lack of environmental interest, etc.).

3.2. Associations Between Non-Religious Microaggressions and Working Alliance

While we collected data using both the RCMS and the MANRIS, the RCMS was used as a redundant measure of religious microaggression for parity with comparison literature (Trusty et al. 2022). Correlations between the RCMS and MANRIS total scores were high (r = 0.65; p < 0.001); thus, the MANRIS and its subscales were used to ensure data saturation due to their more robust factor structure. We conducted Pearson product-moment correlations to examine associations between non-religious microaggressions (MANRIS) and therapeutic working alliance (WAI).

Results indicated a significant negative correlation between MANRIS’ total scores and overall working alliance (r = −0.289, p < 0.01), indicating an inverse relationship between microaggression and therapeutic alliance. This relationship accounted for 8.4% of the variance in working alliance scores. Score descriptions can be found in Table 1. Subscale analyses revealed differential associations across alliance factors. The Task subscale showed the strongest negative correlation with microaggressions (r = −0.334, p < 0.001), followed by Goal (r = −0.222, p < 0.05), and Bond (r = −0.213, p < 0.05). These patterns of results suggest that, of the three factors associated with the therapeutic working alliance, microaggressions and therapeutic tasks and procedures are particularly related, followed by therapeutic goal setting and the clinical bond, respectively.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between MANRIS and Working Alliance.

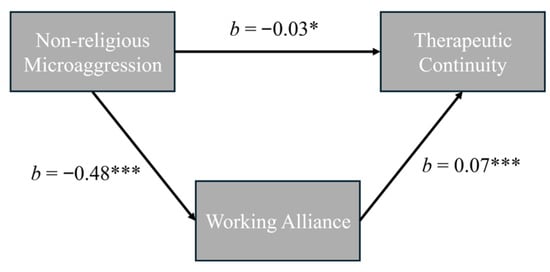

3.3. Working Alliance as a Mediating Variable

A mediation analysis was conducted via SPSS (v. 30 with PROCESS v. 5.0) with 5000 bootstrap samples to test whether working alliance mediated the relationship between non-religious microaggressions and therapeutic continuity. Results indicated that non-religious microaggressions were significantly associated with reduced working alliance (path a; b = −0.48, SE = 0.015, p = 0.001, 95% CI [−0.76, −0.19]), and working alliance was significantly associated with greater therapeutic continuity when controlling for microaggressions (path b; b = 0.07, SE = 0.009, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.05, 0.09]). A path diagram can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Working alliance mediating the relationship between non-religious microaggression and therapeutic continuity. Note: * p < 0.05, *** p ≤ 0.001.

The direct effect of microaggressions on therapeutic continuity, controlling for working alliance, was significant (path c’; b = −0.03, SE = 0.02, p < 0.05, 95% CI [−0.06, −0.001], although the bootstrapped confidence interval approached so closely to zero that the relationship may be weak. Similarly, the indirect effect was significant (path ab; b = −0.03, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [−0.06, −0.01]), indicating that working alliance significantly mediated the relationship between microaggressions and therapeutic continuity. Mediation analysis statistics can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mediation analysis of working alliance between non-religious microaggressions and Therapeutic Continuity.

3.4. The Nature of Non-Religious Microaggressions in Therapy

To address this research question, we asked participants to spend at least one minute responding to two narrative questions. The first question asked participants to reflect on times in which religious conversation had been avoided or initiated in the therapeutic setting. The second question, with the same one-minute timer, asked participants to reflect on instances in which they had been made uncomfortable in therapeutic settings because of non-religious discrimination or stereotypes (Qs 2 and 3, respectively).

Fleiss’ kappa inter-rater agreement scores for Q2 top-level codes ranged from moderate agreement about Avoidance (κ = 0.54, p < 0.001) to good agreement about Conversational Dynamics (κ = 0.69, p < 0.001). Of the 58 participants presented with Q2, 6.8% of participants reported a negative experience regarding R/S discussions in therapy, with most of those negative conversational experiences (59%) being initiated by the counselor. Conversely, 21.7% of our participants indicated experiencing positive conversations about R/S in therapy; 9.7% of the positive conversations were counselor-initiated. Around 22% of our participants indicated that their clinician actively avoided discussing R/S topics in therapy, with another 48.5% indicating that R/S conversations were irrelevant, so they did not come up in therapy.

Inter-rater agreement scores for Q3 top-level codes ranged from poor regarding Stereotype/Prejudice (κ = 0.10, p > 0.05) to very good regarding Never Experiencing (κ = 0.839, p < 0.001). Given the lack of top-level inter-rater agreement for Stereotype/Prejudice, we conducted additional inter-rater analyses to better understand the output. Authors S.K. and C.H. had substantial inter-rater agreement when analyzing with Cohen’s kappa (κ = 0.78, p < 0.001), and it was the ratings of author C.D. that reduced the inter-rater agreement substantially. We hypothesize this is because C.D. took a much stricter definition of discrimination in coding, specifically, as the behavioral manifestation of prejudice—an overlapping conceptual category.

Because prejudice is included in the APA definition of discrimination, we collapsed C.D.’s discrimination coding to include rated instances of stereotype/prejudice. After this collapsing, the new category of Discrimination, Stereotype, and Prejudice dramatically improved inter-rater agreement across the three raters (κ = 0.78, p < 0.001). Based on this collapsed category, approximately 22.5% of our participants experienced instances of counselor prejudice, stereotype, and/or discrimination regarding their irreligious identity, while most participants denied these experiences.

4. Discussion

Using a mixed-methods approach, we aspired to a four-fold interrogation with intent to: (a) quantify the prevalence of microaggressions against non-religious people in psychotherapy, (b) test associations between non-religious microaggression and strength of the therapeutic working alliance, (c) explore the impact of microaggressions on therapeutic continuity, and d) explore the nature of non-religious microaggressions in psychotherapy. We hypothesized (like Trusty and colleagues’ 2022 work on religious microaggression) that microaggressions against the non-religious would be negatively associated with the therapeutic working alliance and therapeutic continuity. While previous literature has regarded the irreligious in therapy, this is the first study to attempt to understand the presence and impact of non-religious microaggressions within the therapeutic relationship from a mixed-method vantage in a majority-religious cultural framework.

4.1. Minority Stress and Non-Religious Microaggression

Consistent with minority stress theory, a theory that highlights the ways in which discrimination, minoritization, and prejudice impact well-being, our participants’ scores indicated that the presence of non-religious microaggression impacts the likelihood of therapeutic continuity by way of the working alliance. Trust, respect, curiosity, empathy, agreement on goals, and humility undergird a positive working alliance (Andrusyna et al. 2001; Stubbe 2018). Some of these facets are reified in the factor structure of the Working Alliance Inventory (goal, task, bond). When these foundational components of the working alliance are harmed (e.g., through microaggressive practices) clients are likely to divest from treatment.

While many negative experiences could potentially harm the therapeutic alliance, our results indicate that non-religious microaggression is one of these significant harms. Specific to our population was the presence of MHC assumptions of client religiosity. The process of assuming is one that is antithetical to curiosity, one of the underlying facets of a strong working alliance. From the U.S. vantage, in which most of the population is religious (predominantly Christian), this assumption can invalidate a client’s lived realities—actively marginalizing them within the therapeutic context. Approximately 40% of our participants reported experiences of their counselor assuming that they were religious. Concealing minoritized identities is one way in which individuals who hold those identities protect themselves from the assumptive stereotypes we see in our participants’ data. As noted by Participant 109 in their written response to question 3: “I fear coming out as an atheist more than as queer.”

4.2. Counselor Avoidance and RSS Competence

In qualitative studies, MHCs have described how they often steer away from discussions of religiosity because the topic is interpreted to be a more controversial cultural dimension (when compared to other dimensions like gender or ethnicity) and discussions surrounding religion tend to stray from the scientific mindset used in counseling (Magaldi-Dopman et al. 2011; Magaldi and Trub 2014). Additionally, when being interviewed for these studies, MHCs tended to relate religious, spiritual, and secular (RSS) topics to broader cultural contexts to avoid specific focus on religiosity, likely due to discomfort with the topic (Magaldi and Trub 2014; Oxhandler and Parrish 2017).

The personal RSS identities of MHCs can be just as complex and tumultuous as their conflicted clients’; these identities tend to affect their therapeutic practice, whether intentional or not (Magaldi-Dopman et al. 2011). When MHCs uphold negative assumptions about atheists or agnostics in general, non-believer clients may receive a lower quality of care (Bishop 2017). Focusing on “should” and “ought” solutions based on the MHC’s own religious beliefs or common reassurances housed in religious frameworks (e.g., “everything happens for a reason”) can be detrimental to non-believer clients in psychotherapy (D’Andrea and Sprenger 2007; Bishop 2017). RSS identity can be central to a client’s experience, so clients may benefit from MHC awareness of the best practices to navigate these topics in a way that fits the client’s needs (Captari et al. 2022).

While we did not ask participants about the training level of their clinicians, there does seem to be some relation between religiosity/spirituality (R/S) and level of training. A 2025 study of Coloradan psychologists, licensed professional counselors (LPCs), marriage and family therapists (MFTs), and clinical social workers (CSWs) showed that psychologists had lower positive attitudes towards R/S integration when compared to LPCs and MFTs (Bedi et al. 2025). These findings also indicated that MFTs and LPCs had higher intrinsic religiosity than either CSWs or psychologists and were more likely to have courses in R/S topics during training. In a similar study out of Texas, researchers found MFTs and LPCs to hold more R/S characteristics than CSWs or psychologists, with fewer religious nones across CSWs, MFTs, and psychologists than the general population (Oxhandler et al. 2017).

Psychologists, while less religious than their clients on average, do purport a belief in the benefits of religion for mental health (Delaney et al. 2007). Psychiatrists, too, tend towards irreligion and are the most irreligious subfield of physicians (Curlin et al. 2007). In general, across multiple regions, master’s level mental health professionals tend to report higher levels of religiosity than doctoral level providers. This is an important recognition given that, according to the U.S. Department of Labor’s (2025) O*Net database, there are more than seven times the number of master’s-level MHCs (698,100 PCs, MFTs, and CSWs) than doctoral-level MHCs (103,400 clinical/counseling psychologists, and psychiatrists)—clients are much more likely, on average, to see a master’s-level than a doctoral-level MHC.

Around 22% of our participants indicated that religion and spirituality were actively avoided as a psychotherapeutic topic by their MHC. It is likely that this is an underestimate, as the entirety of these claims of avoidance was hinged on behavioral and conversational cues. The thought processes of MHCs are not transparent, so it is probable that there is avoidance that does not rise to the level of behavioral manifestation (whether conscious or otherwise). Illuminating the sources of this avoidance is beyond the purview of the current manuscript, but there are logical contenders.

Researchers have reported that the lack of agreed-upon training competencies in spiritual and religious backgrounds, beliefs, and practices (SRBBPs) may contribute to the low rates of addressing RSS issues in therapy and have proposed training standards (Vieten and Lukoff 2022). In the current environment sans standards, 75% of psychology training programs do not provide any courses in religion or spirituality, and only 56% of program directors indicate that religious or spiritual knowledge is an important part of an MHC’s expertise (Schafer et al. 2011). While psychology has yet to adopt formal standards, the Association for Spiritual, Ethical, and Religious Values in Counseling (a division of the American Counseling Association) has denoted 14 competencies in addressing religious/spiritual needs in counseling (ASERVIC n.d.). Because of the lack of educational standards, MHCs have been forced into an untenable position in bearing the brunt of self-directed education regarding clients’ spiritual and religious needs.

Due in part to the dearth of standards, counselors may feel unsettled or uncomfortable in their abilities to broach and bridge in cross-cultural religious/spiritual exchanges. Researchers have indicated that the outcomes of lack of competence in broaching/bridging include both testimonial and hermeneutic injustice (Lee et al. 2022). When an MHC decenters their irreligious client’s experiences of cultural marginalization, testimonial injustice has occurred. When the MHC removes the irreligious client’s opportunity to share their experiences, thus denying the opportunity for a shared understanding, hermeneutical injustice has occurred. Clinicians, as the empowered professionals in the therapeutic relationship, bear the burden to broach and bridge cross-cultural topics—not avoid them in their wait for clients to act as clinicians. However, this burden would ideally be shared by training and continuing education programs that set clinicians up for success in these spaces.

4.3. The Complexity of the Irreligious

Additionally, some may wonder why it might be important to discuss religious and spiritual needs in therapy with clients who identity as atheist or agnostic. The reality of the religious ‘nones’ (also called religious unaffiliated)—the group that includes atheists and agnostics—is one that is diverse and complex. For example, most religious nones believe in a biblical God or other higher power (69%; Pew Research Center 2024). Looking beyond religious beliefs, about half (49%) of religious nones indicate that spirituality is very important to them, and 54% indicate that they engage in behaviors (e.g., meditating, yoga, spending time in nature) that ground them to something bigger than themselves (i.e., a transcendent quality).

Particularly in the United States, a majority-religious country, many religious nones are better categorized as religious ‘dones.’ That is, they were once religious but have since disaffiliated, as seen in many populations historically marginalized by religions (e.g., queer people; Baird et al. 2024). Of our participants, 58% indicated that they had once been affiliated with a denominational religion (including Catholicism, Orthodox Christianity, Baptist, Pentecostalism, Methodism, Lutheranism, Mormonism, Judaism, Buddhism, and Hinduism). This is important to note, because religious dones are quantitatively and qualitatively different than people who have never been religious. A significant difference between these populations is the presence of “religious residue”—cognitive, emotional, and behavioral processes linked to religious cultural learning that persist after religious deidentification (Van Tongeren et al. 2021). Religion and spirituality, as cultural variables, impact individuals—even those deidentified—as deeply as other cultural variables commonly taught in clinical training programs. To avoid a client’s RSS history is to ignore a core facet of who they are as a person.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

Our study possesses notable strengths in its participant data collection and methodology. Our use of a vetted online research participant platform facilitated our collection of quality data from our motivated participants and allowed us to collect a large enough sample to achieve adequate power for our quantitative analyses. Our sample generally matched the demographic window for our population, with an oversampling of irreligious individuals who are Black and Latinx. Additionally, our use of open-ended questions allowed us to collect deep, rich data about our participants’ therapeutic experiences.

While much of our sample matched the relevant demographic frame of comparison, we did experience an oversampling of groups that included White and college-educated individuals, which should be considered during interpretation. One of the primary limitations of our methodology is the interpretive nature of our conceptual content analysis. Our inter-rater agreement was generally high, which could be interpreted as a feature of our question development process and our coding rule agreement. However, because two of the coders were previous students of the corresponding author (although over two years in the past, at the point of analysis), a more critical interpretation of the inter-rater agreement could center on shared interpretive lenses. A future team may ensure interpretivist heterogeneity by interrogating the relationships between coders.

5. Conclusions

Using a mixed-method approach, we provided evidence that non-religious psychotherapy clients face unique challenges stemming from microaggressive experiences, including assumptions of religiosity and counselor avoidance of religious/spiritual discourse. Our results indicate that these experiences are associated with significantly weakened therapeutic alliances and reduced therapeutic continuity, which highlight the importance of clinician competence in addressing inherently cultural-laden religious, spiritual, and secular identities. Our conceptualization of irreligious identities as concealable stigmatized identities reaffirms both the risks of disclosure and concealment in therapeutic settings. Our results affirm that the therapeutic working alliance is vulnerable to subtle forms of bias and that mental health counselors must be equipped to broach and bridge diverse religious, spiritual, and secular experiences. Attending to these often-avoided dimensions is essential for ensuring a holistic understanding of our clients, fostering trust, and strengthening therapeutic outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/rel16121576/s1, Table S1: Inter-rater agreement across conceptual codes.; Table S2: Complete participant demographic information.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R.D., C.H.H. and S.E.K.; data curation, C.R.D.; formal analyses—quantitative, C.R.D.; formal analyses—qualitative, C.R.D., C.H.H. and S.E.K.; investigation, C.R.D.; methodology, C.R.D., C.H.H. and S.E.K.; project administration, C.R.D. and C.H.H.; supervision, C.R.D.; validation, C.R.D.; visualization, C.R.D.; writing—original draft—introduction, C.H.H. and S.E.K.; writing—original draft—method, results, discussion, C.R.D.; writing—review and editing, C.R.D., C.H.H. and S.E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Valparaiso University (VUID 25-04, 20 February 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to the sensitive nature of our participants’ narratives.

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author would like to thank various members of the CRIB Lab at both Knox College and Valparaiso University for their collaboration and ideas that supported this work. In addition, we would like to thank Anastasia Kildeeva, University of Lethbridge, for her assistance in preparation of the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbott, Dena M. 2021. Psychotherapy with nonreligious clients: A relational-cultural approach. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 52: 470–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, Dena M., and Debra Mollen. 2018. Atheism as a concealable stigmatized identity: Outness, anticipated stigma, and well-being. The Counseling Psychologist 46: 685–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, Dena M., and Hali J. Santiago. 2023. Rural atheists in the United States: A critical grounded theory investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology 70: 377–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, Dena M., Debra Mollen, Jessica A. Boyles, and Elyxcus J. Anaya. 2022. Hidden in plain sight: Working class and low-income atheists. Journal of Counseling Psychology 69: 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, Dena M., Michael Ternes, Caitlin Mercier, and Chris Monceaux. 2020. Anti-atheist discrimination, outness, and psychological distress among atheists of colour. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 23: 874–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. n.d. APA Dictionary of Psychology. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Andrusyna, Tomasz P., Tony Z. Tang, Robert J. DeRubeis, and Lester Luborsky. 2001. The factor structure of the working alliance inventory in cognitive-behavioral therapy. The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research 10: 173–78. [Google Scholar]

- ASERVIC. n.d. Spiritual and Religious Competencies. Available online: https://aservic.org/spiritual-and-religious-competencies/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Baird, Rebecca, Camryn H. Hutchins, Seth E. Kosanovich, and Christopher R. Dabbs. 2024. Queer Experiences of Religion: How Marginalization Within a Religion Affects Its Queer Members. Sexes 5: 444–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, Robinder P., Thomas B. Douce, Virginia R. Dreier, and Betty Cardona. 2025. Integrating clients’ religion/spirituality into practice: A comparison between psychologists, counselors, marriage and family therapists, and clinical social workers in colorado. Journal of Clinical Psychology 81: 964–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, Brittany. 2017. Advocating for atheist clients in the counseling profession. American Counseling Association 63: 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, Melanie E., Joseph Hammer, Jacob S. Sawyer, Austin Eklund, and Joseph Palamar. 2016. Perceived experiences of atheist discrimination: Instrument development and evaluation. Journal of Counseling Psychology 63: 557–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burris, Christopher T. 2022. Poker-faced and godless: Expressive suppression and atheism. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 14: 351–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Stephen J. 2021. Experiences of the non-religious in psychotherapy: Implications for clinical practice and therapist education. Secular Studies 3: 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell-Harris, Catherine L., Angela L. Wilson, Elizabeth LoTempio, and Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi. 2011. Exploring the atheist personalty: Well-being, awe, and magical thinking in atheists, Buddhists, and Christians. Mental Health, Religion, & Culture 7: 659–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Captari, Laura E., Richard G. Cowden, Steven J. Sandage, Edward B. Davis, Andrea O. Bechara, Shawn Joynt, and Victor Counted. 2022. Religious/spiritual struggles and depression during COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns in the global south: Evidence of moderation by positive religious coping and hope. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 14: 325–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Zhen Hadassah, Louis A. Pagano, Jr., and Azim F. Shariff. 2018. The Development and Validation of the Microaggressions Against Non-Religious Individuals Scale (MANRIS). Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 10: 254–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantine, Madonna G. 2007. Racial microaggressions against African American clients in cross-racial counselling relationships. Journal of Counseling Psychology 54: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragun, Ryan T., Barry Kosmin, Ariela Keysar, Joseph H. Hammer, and Michael Nielsen. 2012. One the receiving end: Discrimination toward the non-religious in the United States. Journal of Contemporary Religion 27: 105–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curlin, Farr A., Shaun V. Odell, Ryan E. Lawrence, Marshall H. Chin, John D. Lantos, Keith G. Meador, and Harold G. Koenig. 2007. The relationship between psychiatry and religion among U.S. physicians. Psychiatric Services 58: 1193–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbs, Christopher R., and Camryn H. Hutchins. 2024. Moral Distrust of Atheism. In Encyclopedia of Religious Psychology and Behavior. Edited by Todd K. Shackelford. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, Livia M., and Johann Sprenger. 2007. Atheism and nonspirituality as diversity issues in counseling. American Counseling Association 51: 149–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, Harold D., William R. Miller, and Ana M. Bisonó. 2007. Religiosity and Spirituality Among Psychologists: A Survey of Clinician Members of the American Psychological Association. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 38: 538–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depauw, Hilde, Alain Van Hiel, Barbara De Clercq, Piet Bracke, and Bart Van de Putte. 2023. Addressing cultural topics during psychotherapy: Evidence-based do’s and don’ts from an ethnic minority perspective. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research 33: 768–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgell, Penny, Douglas Hartman, Evan Stewart, and Joseph Gerteis. 2016. Atheists and other cultural outsiders: Moral boundaries and the non-religious in the United States. Social Forces 95: 607–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, Will M., and Maxine B. Najle. 2018. How Many Atheists Are There? Social Psychological and Personality Science 9: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, Richard C., Ayla Rubenstein, and Heather K. Terrell. 2019. Distrust persists after subverting atheist stereotypes. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 23: 1103–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, Robert. L., and J. Arthur Gillaspy. 2006. Development and validation of a revised short version of the working alliance inventory. Psychotherapy Research 16: 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, Adam O., and Dianne Symonds. 1991. Relation between working alliance and outcome in psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology 38: 139–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humanists International. 2025. The Freedom of Thought Report: A Global Report of the Rights, Legal Status and Discrimination Against Humanists, Atheists and the Non-Religious. Available online: https://fot.humanists.international/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/FOTR-PAGE.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Jahangir, Syeda F. 1995. Third force therapy and its impact on treatment outcome. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 2: 125–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanolkar, Kimaya. 2024. Impact of Atheist Identity Disclosure on Experience of Microaggressions in Therapy. Master’s Thesis, Minnesota State University, Mankato, Minnesota. Available online: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds/1453/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Laerd Statistics. 2019. Independent-Samples T-Test Using SPSS Statistics. Statistical Tutorials and Software Guides. Available online: https://statistics.laerd.com/spss-tutorials/independent-samples-t-test-using-spss-statistics.php (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Lee, Eunjung, Andrea Greenblatt, Ran Hu, Marjorie Johnstone, and Toula Kourgiantakis. 2022. Developing a model of broaching and bridging in cross-cultural psychotherapy: Toward fostering epistemic and social justice. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 92: 322–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaldi, Danielle, and Leora Trub. 2014. (What) do you believe?: Therapist spiritual/religious/non-religious self-disclosure. Society for Psychotherapy Research 28: 484–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaldi-Dopman, Danielle, Jennie Park-Taylor, and Joseph G. Ponterotto. 2011. Psychotherapists’ spiritual, religious, atheist or agnostic identity and their practice of psychotherapy: A grounded theory study. Society for Psychotherapy Research 21: 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, P., and Ronald Inglehart. 2004. Religion and politics in the Muslim world. In Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. Edited by Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 133–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxhandler, Holly K., and Danielle E. Parrish. 2017. Integrating client’s religion/spirituality in clinical practice: A comparison among social workers, psychologists, counselors, marriage and family therapists, and nurses. Journal of Clinical Psychology 74: 680–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxhandler, Holly K., Edward C. Polson, Kelsey M. Moffatt, and W. Andrew Achenbaum. 2017. The Religious and Spiritual Beliefs and Practices among Practitioners across Five Helping Professions. Religions 8: 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, Louis Anthony. 2015. Development and Validation of the Scale of Atheist Microaggression. Doctoral Dissertation, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, ND, USA. Available online: https://commons.und.edu/theses/1691/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Pew Research Center. 2024. Religious ‘Nones’ in America: Who They Are and What They Believe. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2024/01/24/religious-nones-in-america-who-they-are-and-what-they-believe/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Public Research Religion Institute. 2021. Competing Visions of America: An Evoling Identity or A Culture Under Attack? Available online: https://www.prri.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/PRRI-Oct-2021-AVS.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Schafer, Rachel M., Paul J. Handal, Peter A. Brawer, and Megan Ubinger. 2011. Training and education in religion/spirituality within APA-accredited clinical psychology programs: 8 years later. Journal of Religion and Health 50: 232–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbe, Dorothy E. 2018. The Therapeutic Alliance: The Fundamental Element of Psychotherapy. Focus (American Psychiatric Publishing) 16: 402–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue, Derald Wing, Christina M. Capodilupo, Gina C. Torina, Jennifer M. Bucceri, Aisha M. B. Holder, Kevin L. Nadal, and Marta Esquilin. 2007. Racial microaggression in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist 62: 271–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, Lawton K., and Martin Heesacker. 2012. Anti-atheist bias in the United States: Testing two critical assumptions. Secularism and Nonreligion 1: 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trusty, Wilson T., Joshua K. Swift, Stephanie Winkeljohn Black, A. Andrew Dimmick, and Elizabeth A. Penix. 2022. Religious microaggressions in psychotherapy: A mixed methods examination of client perspectives. Psychotherapy 59: 351–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, Jean M., Julie J. Exline, Joshua B. Grubbs, Ramya Sastry, and W. Keith Campbell. 2015. Generational and Time Period Differences in American Adolescents’ Religious Orientation, 1966–2014. PLoS ONE 14: e0221441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Labor. 2025. O*NET Occupation Keyword Search. Available online: https://www.onetonline.org (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Van Tongeren, Daryl R., Nathan C. DeWall, Sam A. Hardy, and Philip Schwadel. 2021. Religious identity and morality: Evidence for religious residue and decay in moral foundations. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 11: 1550–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieten, Cassandra, and David Lukoff. 2022. Spiritual and religious competencies in psychology. American Psychologist 77: 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkeljohn Black, Stephanie, and Amanda P. Gold. 2019. Trainees’ cultural humility and implicit associations about clients and religious, areligious, and spiritual identities: A mixed-method investigation. Journal of Psychology and Theology 47: 202–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, Kevin J., Jesse M. Smith, Kevin Simonson, and Benjamin W. Myers. 2015. Familial Relationship Outcomes of Coming Out as an Atheist. Secularism and Nonreligion 4: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).