Abstract

This paper investigates the complex interrelation between national identity and religion in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), moving beyond binary conceptualizations by integrating multiple forms of national belonging, religiosity, and spirituality. Drawing on data from the Pew Research Center’s Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe survey across 16 post-communist countries, we performed a k-means cluster analysis that identifies a robust threefold typology of national identity—nationalist, ethnic, and patriotic—arranged along a continuum from exclusivist to inclusive orientations. The nationalist type combines patriotic pride and respect for the country’s laws and institutions with an emphasis on ethnic origin and cultural superiority, and represents the most exclusionary form of national identification. The ethnic type remains exclusivist through its emphasis on ancestry, but lacks chauvinistic elements. The patriotic type, by contrast, embodies an open, non-exclusivist orientation that links national pride to respect for the country’s laws and institutions, while rejecting ethnic criteria of belonging and chauvinistic positions. Overall, exclusivist understandings of national identity predominate across the region, though their prevalence varies systematically according to confessional context, with nationalist identities particularly widespread in countries with an Orthodox majority. The findings also show that religious dogmatism and institutional religiosity reinforce exclusivist orientations, whereas non-religious, individualistic spirituality aligns rather with inclusive patriotism. The study thus provides an empirically grounded typology and highlights the heterogeneous, non-monolithic character of the religion-nation nexus in CEE.

1. Introduction: National Identity and Religion in the West and East

In times when nation states are being challenged by globalization, by (perceived or real) ethnic and cultural diversity, and by other external threats, the question of the foundations and content of national identity has regained importance not only for the societies concerned but also for academia. In this context, it is repeatedly emphasized that Central and Eastern Europe differ from Western Europe in terms of the characteristics and concepts of national identity. Particularly influential in this regard has been the approach of Hans Kohn, who distinguished between a predominantly politically oriented Western nationalism based primarily on the principle of citizenship and a non-Western form based on culture, traditions, and myths, and oriented towards the national community (Kohn 1944). According to this approach, while Western nationalism manifested itself within existing states as a struggle for a pluralistic society and has an inclusive, open, voluntary, and civil character, the non-Western type emerged before or beyond state formation and therefore assumed a more exclusive, ascriptive, closed ethno-national character from the outset (Spohn 1998, p. 112; Hirschhausen and Leonhard 2001, p. 16; cf. also Brown 1999). This dichotomy has been repeatedly criticized on conceptual-theoretical, empirical, and methodological grounds, and attention has been drawn to the heterogeneity within regions with regard to ideas and principles of nationality (Kymlicka 2000; Schulze Wessel 2001; Weil 2001; Shulman 2002; Tižik 2012; see also the historical overview in Piwoni and Mußotter 2023 and our comments in the next section). Nevertheless, quantitative empirical studies continue to use this distinction as a “useful theoretical tool” (Kunovich 2009, p. 574: note 1; see, for example, Brubaker 1992; Greenfeld 1992; Jones and Smith 2001a, 2001b; Bahna et al. 2009; Helbling et al. 2016; Ariely 2020; Guglielmi and Piacentini 2024).

Against the backdrop of the continuing influence that historical legacies and current dynamics have on identity-formation in the region, national identity appears to be more closely linked to religion in large parts of Central and Eastern Europe than in Western Europe (Martin 1978; Casanova 1994; Spohn 1998; Triandafyllidou 2024). At the same time, the relationship between religion and national identity has not been and is not static. Political constellations, geostructural relationships, historical and contemporary dynamics, including the persistence and collapse of imperial empires, and processes of secularization and globalization—these have all repeatedly led to shifts in attitudes towards religion and its role in identity formation (Brubaker 1996). According to Spohn (1998, 2012), who draws on the work of Martin (1978), religious identity-formation can be observed primarily where religion did not occupy a central position in the respective geopolitical and geocultural context during the early stages of nation-state formation, but rather had a peripheral position as the religion of ethnic and national minorities within imperial empires. This was the case in most countries of Central and Eastern Europe.1

Historical circumstances clearly continue to have a lasting effect and are intertwined with later developments: in Western Europe, national identities increasingly took on a secular character, albeit with restrictions and exceptions. In post-communist Europe (especially in the Catholic and Orthodox societies of Eastern and Southeastern Europe, and to a clearly lesser extent in Protestant countries), the religious components of national identity gained in importance, initially as a counter-movement to the secularism of the former communist state, and later as a reaction to perceived threats in the wake of processes of globalization and migration (cf. Spohn 1998, 2012; Tižik 2012; Grzymala-Busse 2019; Barry 2020).

The relationship between nationalism and religion is not always easy to determine. As Grzymala-Busse (2019, p. 4ff.) points out, both phenomena can coexist, substitute for each other, or even reinforce one another. A common view regarding today’s Central and Eastern Europe is that the collapse of communism left a political and moral vacuum in societies, which, in conjunction with the challenges of an ever-faster-changing and increasingly complex world, led to religion being rediscovered as an answer to the search for and consolidation of meaning. Against this backdrop, where the religious foundations of society had survived communist rule, at least beneath the surface, a nationalization and politicization of religion took place, and national and religious identities converged to the point of religious nationalism (Hoppenbrouwers 2002; Pew Research Center 2017; Triandafyllidou 2024). The strengthening of the role of religion in national identity is sometimes, but by no means always, accompanied by a general religious revival (cf. Spohn 1998; Barry 2020). Tižik (2012, p. 120ff.) emphasizes in this context that religion sometimes also fulfils a purely “performative function as a symbol of collective identity”, which often manifests itself in an idealized notion of a religious past and is found above all in countries that have few other ideological and mobilizing roots (see also Borowik 2002).

This paper takes up the debate on the character and particularities of national identity in Central and Eastern Europe. We seek to distinguish different types of national identity and explore how they relate to religion, religiosity, and spirituality. First, we present the state of research on national identity in quantitative social research (Section 2) and on the connection between national identity, religion, and religiosity (Section 3). We then explain our objectives in more detail and formulate our research questions and hypotheses (Section 4). We then describe (Section 5) the data used (Subsection 5.1), the measuring instruments (Subsection 5.2), and the methods of analysis (Subsection 5.3), before presenting our empirical findings (Section 6). Here, we first introduce a newly developed typology of national identity and show the distribution of the diverse types (nationalist, ethnic, patriotic) across the countries of the CEE region (Subsection 6.1). We then show how a religious and denominational concept of national belonging relates to the types of national identity identified, and explore the relationship between the types of national identity and different forms of religiosity and spirituality (Subsection 6.2). The article concludes with a summary of the most important findings, a discussion of its limitations, and an outlook on any research questions still open (Section 7).

2. National Identity in Quantitative Social Research

In empirical social research, the phenomenon of national identity can often be embedded in the conceptual framework of Social Identity Theory. According to this theory, belonging to a social group such as a national community is associated with access to certain individual and collective resources, such as social support and material advantages. However, the central motivation for wanting to belong to a group is considered to be people’s desire for a positive social identity or their wish to achieve and maintain self-esteem. The in-group is seen as positively distinct from relevant out-groups (Tajfel and Turner 1979; Tajfel 1982). This does not necessarily have to go hand in hand with a devaluation of the out-groups (Brewer 1999). However, negative stereotyping and, as a result, discrimination and devaluation of out-groups can occur, especially when one’s own group is perceived as threatened (Stephan et al. 2002), is in competition for scarce goods (Sherif 1966), and/or there are certain personality dispositions such as a tendency towards authoritarianism (Adorno et al. 1950; Allport 1954).

In quantitative social research, national identity is usually measured either in its cognitive dimension (where are the national boundaries?) or in its more emotional-affective dimension (how is the bond to the nation formed?—Ariely 2020). The former component is primarily assessed by investigating certain conditions of national belonging, which can often be condensed into concepts of belonging. The second component is primarily assessed by distinguishing between nationalism and patriotism.

As mentioned in the introduction, the conceptualization and operationalization of concepts of belonging is largely based on the dichotomy between open/voluntarist/civic and closed/ascriptive/ethnic types (Jones and Smith 2001a, 2001b; Ariely 2013). Many quantitative and comparative studies are based on the instrument to measure national identity developed by Citrin et al. (1990) and used repeatedly in the International Social Survey Programme (module “National Identity”, conducted in 1995, 2003, and 2013). Respondents were asked about various characteristics that a person must have to “truly” belong to the national community. Among other things, respondents were asked whether it is important to have ancestors who belong to the ethnic majority, to belong to the nationally dominant religion, to have been born in the country, and whether it is important to speak the national language, to respect political institutions and laws, and to have citizenship of the country. Based on the respondents’ answers, attempts were made (mostly using factor analysis) to map the civic-ethnic dichotomy. This was partially successful, but also revealed inconsistencies and contradictions that continue to fuel discussion to this day. In addition to the difficulty of assigning some of the items to meaningful categories, the fact that individual items loaded on different factors in different countries raised doubts about the comparability between countries. For example, the language item has proven to be ambivalent in both respects (Jones and Smith 2001a; Kunovich 2009; Reeskens and Hooghe 2010; Ariely 2020), there is disagreement as to whether the characteristic of religion should be understood as ethnic or civic (Jayet 2012), and, although the items “born in country” and “have […] ancestry” often load on the same factor, they represent two diametrically opposed concepts of citizenship law, particularly in immigrant societies (jus soli vs. jus sanguinis; cf. Helbling et al. 2016, p. 746). Another fundamental difficulty lies in the lack of clarity between the two concepts in that respondents do not perceive them as alternatives, but rather as correlated—primarily because most of those who advocate a narrower ethnic concept also consider the less restrictive and exclusive characteristics to be important (Hjerm 1998; Reeskens and Hooghe 2010; Helbling et al. 2016). Some researchers have attempted to solve this problem by calculating sum or difference values (Kunovich 2009; Bahna et al. 2009; Reeskens and Wright 2014; Helbling et al. 2016). Others have therefore argued that the boundaries of the nation should not be understood orthogonally in terms of the civic-ethnic dichotomy, but rather as a continuum on a single dimension, and have proposed a measurement using a single scale with ethnic and civic identity concepts at opposite ends (Smith 1991; Westle 1999; Wright 2011a, 2011b; Wright et al. 2012). Some have also suggested adding a cultural (or “mixed”) dimension (Kymlicka 2001; Shulman 2002; Westle 2012) or using a ranking rather than a rating (Wright et al. 2012; Ariely 2020).

Given these inconsistencies and problems, as well as the different approaches, it is hardly surprising that the results for Central and Eastern Europe are not uniform. Nevertheless, for many European countries, patterns that closely resemble the civil-ethnic dichotomy could be reproduced, and a fundamental West–East difference could also be observed (Jones and Smith 2001a, 2001b; Molnár 2006; Bahna et al. 2009; Kunovich 2009; Ariely 2013; Reeskens and Wright 2014; Helbling et al. 2016; Larsen 2017). In addition, it has been generally shown that the two concepts of belonging also discriminate in relation to other attitudes that signal openness or closedness (such as attitudes towards immigrants and immigration; Hjerm 1998; Kunovich 2009; Hochman et al. 2016).

Parallel to the research on concepts of belonging, another strand of research has developed in the field of studies of expressions of national identity, this research focusing on different types of attachment to the nation and revolving around the concepts of nationalism and patriotism. The first systematic implementations of concepts for empirical measurement, which have strongly influenced later research, were carried out by Kosterman and Feshbach (1989) and Blank and Schmidt (2003). Although there are many different variants of specific conceptualization and empirical implementation, the general understanding can be summarized as follows. While both concepts involve a positive view of or positive attachment to one’s own nation, they differ primarily in their reference to “the other”: nationalism is based not only on a positive attitude towards one’s own country, but also on a comparison between one’s own nation and others. It is generally accompanied by the idealization of one’s own nation and is associated with the idea that one’s own country is superior to others. In this respect, there is a certain similarity to the phenomenon of chauvinism. On the other hand, patriotism, defined primarily as love for or pride in one’s own country in general, pride in certain attributes of the country or its institutions, does not necessarily have to be accompanied by hostility towards other groups (Kosterman and Feshbach 1989; Hjerm 1998; Blank and Schmidt 2003; Li and Brewer 2004; Davidov 2010; Latcheva 2011; Huddy 2016; Huddy et al. 2021).

The operationalization and measurement also vary. As in the case of concepts of belonging, many empirical studies, especially cross-national studies, draw on the ISSP “National Identity” module, which contains around 20 items that can be assigned to one of the two concepts. Items such as “Generally speaking, [country] is a better country than most other countries” and “The world would be a better place if people from other countries were more like the [e.g., Germans]” are often used as examples of nationalism. Patriotism was measured by asking questions about what people are proud of—their own nationality, scientific, technical, economic, sporting, and cultural achievements, democracy, the social system, etc. However, even in studies that use these instruments, some of the conceptual, normative, and empirical differences and inconsistencies that are characteristic of this line of research are already apparent (cf. Fleiß et al. 2009; Mußotter 2022; Piwoni and Mußotter 2023). Different researchers used different indicators from the spectrum provided (Hjerm and Schnabel 2010; Ariely 2012, 2020; Huddy et al. 2021). Piwoni and Mußotter (2023, p. 915) pointed out in this context that, even in the two seminal works by Kosterman and Feshbach (1989) and Blank and Schmidt (2003), the conceptual definition of patriotism differs significantly in terms of content. While the former primarily address emotional attachment based on love for and pride in one’s own country, the latter pursue a Habermasian approach and focus on constitutional patriotism, which is based on pride in democratic and humanistic achievements. Sometimes the same item is assigned to nationalism in one case and to patriotism in another (e.g., pride in one’s own nationality; see Blank and Schmidt 2003; Kemmelmeier and Winter 2008; see also Piwoni and Mußotter 2023, p. 916).

Overall, criticism of the concepts has led only to minor modifications and further developments. For example, it has been suggested that the term nationalism should be abandoned due to its vagueness and replaced by chauvinism (Citrin et al. 2001). The problem of the lack of clarity in the concepts of nationalism and patriotism, which was already pointed out in the 1960s (Doob 1964), has been addressed in various ways by creating scales that refrain from making a dual distinction between nationalism and patriotism, and instead reflect the intensity of national attitudes or nationalist sentiments (Dekker et al. 2003; Kasianenko 2020).

Despite all their weaknesses and the criticism that has been levelled at them, however, many scholars still consider the concepts useful, including their operationalization as in the ISSP, and they are widely used today (cf. Piwoni and Mußotter 2023, p. 917). Similar to the ethnic and civic concepts of belonging, nationalism and patriotism prove to be positively correlated, but often have different effects with regard to certain other attitudes, with nationalism showing mainly positive correlations with anti-immigrant attitudes, while patriotism shows negative or no correlations (Blank and Schmidt 2003; De Figueiredo and Elkins 2003; Kunovich 2009; Grigoryan and Ponizovskiy 2018; Huddy et al. 2021). The fact that the correlations for patriotism are not as clear-cut as for nationalism is likely to be due not only to the different and inconsistent operationalization, but also to the fact that, as has already been shown in the relationship between ethnic and civil concepts of belonging, the same effect is evident here: namely, that the two phenomena are not mutually exclusive, in that nationalists can also be patriots at the same time (cf. Kasianenko 2020, p. 354).

Although the two strands of research on national identity not only share a common overarching theme and pursue similar questions, but also exhibit some parallels and overlaps in conceptual, normative, and empirical terms, it is also the case that “both strands have tended to ignore each other and have thus largely developed independently” (Piwoni and Mußotter 2023, p. 907). Attempts to define the relationship between all four dimensions—ethnic belonging, civic belonging, nationalism, and patriotism—are still rare. Huddy et al. (2021) subjected 25 items from the ISSP to confirmatory factor analysis, but then subsumed the belonging items in their two-factor solution under the overarching dichotomy between nationalism and patriotism. Kasianenko (2020) deliberately dissolves the four-way division, partly to overcome the implicit normative foundations of the dimensions, and presents different intensities of nationalist sentiments on a single Mokken scale. However, the items that she used for the concepts of belonging again form two subcategories, both of which represent “weak” nationalism (in her terminology, the categories “national identity” and “national consciousness”), while patriotism and national pride were differentiated according to two further gradations and represent the “moderate” spectrum of the scale. In the case of strong expressions, she distinguishes between “superiority” and “xenophobic nationalism”. Ariely (2020) made a systematic attempt to maintain the four dimensions in a cross-country study by correlating them with each other. He found a consistent positive correlation between nationalism and the ethnic concept of belonging, as well as a negative correlation between nationalism and the civic concept of belonging. However, the obvious assumption—namely, that the two “constructive”, universalistic variants of national identity, patriotism and the civic concept of belonging—correlated positively with each other is not confirmed. Instead, patriotism correlates positively with the ethnic concept of belonging. One possible reason for these unexpected results is that, although Ariely attempted to resolve the overlap between the two concepts of belonging by creating a difference indicator, he allowed overlaps between nationalism and patriotism (Ariely 2020, pp. 72, 74). In our opinion, it is still necessary to create a typology that is as selective as possible, but that does not dissolve the dimensions that are still theoretically convincing.

3. The Connection Between National Identity, Religion, and Religiosity

There has been a growing intertwining of national ideas and religious identities worldwide since the end of the 20th century. Huntington (1993) claimed that, with the end of the Cold War and against the backdrop of growing global interdependence and post-imperial or post-colonial constellations, international conflicts are increasingly dominated by cultural aspects, with religion representing a mobilizing factor. There have been an increasing number of voices in the sociology of religion that have noted a “re-enchantment” and “de-privatization” of religion (Berger 1999; Casanova 1994, 1998). Even staunch advocates of the secularization thesis concede that, when it can be linked to issues of national self-determination or the defence of cultural symbols, values, or norms, religion can persist or be revitalized (cf. the “cultural defence” thesis in Bruce 2002).

Within the framework of the concept of national identity, religion can be understood as a specific symbolic boundary that fulfils different functions and can have different effects. As a central feature of the collective identity of a group or society, it can make a positive contribution to self-esteem. At the same time, though, it forms a boundary between the in-group and the out-group, between “us” and “them”, which can have a conflictual and polarizing effect (Kunovich and Hodson 1999, cf. also Trittler 2017, p. 710). In fact, the connection between religion and national identity is often seen as problematic, since this alliance often has exclusivist traits (Kunovich 2006, p. 437; Karpov et al. 2012; Warhola and Lehning 2007). When it comes to the dichotomous taxonomies of national identity (“closed/ethnic/exclusivist” vs. “open/civil/inclusive”), religion is often assigned to the former (cf. Jones and Smith 2001a; Helbling et al. 2016; Ariely 2020; Guglielmi and Piacentini 2024). An ethnic and religious national-conservative conception of nation, often associated with the general demand to prevent or restrict immigration, is particularly attributed to Eastern European societies (cf. Larsen 2017, p. 985f.; Sarkissian 2024, p. 301f.).

Some approaches emphasize the denomination-specific characteristics of the relationship between religion and national identity. With regard to Central and Eastern Europe, particular reference is made to the specific intertwining of Eastern Orthodoxy, the state, and the nation (Tomka 2006; Breskaya and Zrinščak 2024). According to Roudometof (1999, 2014), the 19th-century “nationalization of Orthodoxy” is the key process that generated religious nationalism and, later, Orthodox chauvinism. Churches that were originally transnational became state-bound institutions legitimizing national identity and political sovereignty. Thus, Orthodoxy became a symbolic resource for nation-building—it sanctified national myths, territorial claims, and ideas of cultural superiority. Ramet (2019) also claims that Eastern Orthodoxy tends to sacralize national identity and can provide a fertile ground for national chauvinism. Orthodoxy often presents itself as the defender of authentic spirituality against the West’s “decadence”. After 1989, countries with Orthodox traditions witnessed a rebirth of the fusion of nation and religion, and of the ideology of moral superiority.

At the individual level, too, it seems necessary to distinguish between different forms of religiosity. Studies on (political) tolerance and prejudice suggest that different forms of religiosity may be linked to national identity in different ways. Empirical studies have repeatedly found correlations between various indicators of individual religiosity and church attendance on the one hand, and authoritarian or ethnocentric attitudes on the other (cf. Wulff 1991, p. 219f.). However, the assumption that there is a general connection between religiosity per se and authoritarianism has proven unfounded (Altemeyer and Hunsberger 1992, p. 114). Allport and Ross (1967, p. 441) found that people with an extrinsic religious orientation and those characterized by “undifferentiated thinking” and a “dogmatic spirit” are particularly prone to discriminatory attitudes and prejudices towards other social groups. In this sense, attitudes such as intolerance, devaluation of others, and authoritarianism function as a means of coping with the uncertainties and ambiguities of everyday life (cf. also Adorno et al. 1950). In emphasizing the link between relatively rigid, conservative-doctrinal, or fundamentalist forms of religious belief and (political) intolerance, the studies by Wilcox and Jelen (1990), Ellison and Musick (1993), Doktór (2001), and Karpov (2002) also highlight the crucial importance of different forms of religiosity. However, it has also been proven that liberal, open, and reflective forms of religiosity that emphasize universal principles such as mercy and charity, and that point to the general questionability of religious dogmas, promote benevolent, tolerant, and integrative attitudes towards others (Adorno et al. 1950; Allport 1954; Batson et al. 1993; Hunsberger 1995). Spirituality also seems to be associated with tolerant attitudes (Hughes 2013). In this context, Trittler (2017, p. 710) has pointed out, with explicit reference to the issue of national identity, that religiosity can also have an integrative effect in connection with ideas of national belonging.

Against this backdrop, it is not surprising that empirical findings on the relationship between religion, religiosity, and national identity are inconsistent and ambivalent. As a component of national identity, religion (in the sense of affirming the statement that only those who profess the “right” religion can be good members of the national community) is usually attributed to the ethnically ascribed concept of belonging (Bahna et al. 2009; Helbling et al. 2016; Storm 2011; Alemán and Woods 2017). Such a religious and ethnic based concept of belonging is often associated with anti-immigrant and anti-minority attitudes, and stems from a desire to see cultural homogeneity and to preserve national traditions (Grzymala-Busse 2019, p. 10).

Studies on national identity often only consider the factor of religiosity in a rudimentary way as a correlate or predictor: often due to the data available, quantitative studies usually limit themselves to including indicators of traditional church religiosity, measured primarily by religious affiliation and church attendance (cf. Jones and Smith 2001b; Kunovich 2009; Pew Research Center 2017, 2018a). In general, there are often positive correlations between national identity, national attachment, and religiosity, although overly strong causal statements are largely avoided. For example, there is a positive correlation in predominantly Christian societies between individual affiliation to Christianity and agreement with the statement that it is important to be a Christian to be part of the national community (Kunovich 2006; Storm 2011; Silver et al. 2025). According to Trittler (2017, p. 714), belonging to the majority religion correlates particularly strongly with a religious concept of national belonging when it is accompanied by a strong group identity (measured on the basis of religious self-assessment) and by a perceived ethnic threat. Grzymala-Busse (2015, 2019) also repeatedly found a positive correlation between church attendance and a religious concept of national belonging. Several studies have found that people with religious ties (usually also measured by church attendance) are ethnically oriented (Jones and Smith 2001b, p. 110; Kunovich 2009, p. 586), but there are also isolated reports of a negative correlation (see Storm 2011, p. 841 for Great Britain). People without church ties tend to favour a civil-voluntarist concept of belonging, although the correlations here are rather weak (Jones and Smith 2001a, p. 55f; this also tends to be the case in Kunovich 2009, p. 586). For the region of Central and Eastern Europe, Guglielmi and Piacentini (2024, p. 474) have reported that religiosity correlates positively with both the ethnic and civil concepts of belonging. In a pan-European comparison, Tomka and Szilárdi (2016, p. 93) found consistently positive correlations between church attendance and national pride, with the correlations being stronger in Central and Eastern than in Western Europe and, within Central and Eastern Europe, being even stronger in Catholic and Orthodox countries than in Protestant countries. Doktór (2007) also found positive correlations between church attendance and national pride in Central and Eastern Europe. A decade after the political upheavals in 1989–90, Tomka and Zulehner (2000, p. 116) concluded from the findings of their New Departures study that the connection between religiosity and national sentiment extends across all social groups and all countries in Eastern (Central) Europe, but is somewhat stronger in the less socioeconomically developed countries than in the more “advanced” countries.

4. Objectives, Research Questions, and Hypotheses

Based on the theoretical and operational considerations outlined above, our study has two objectives. First, to develop an empirical typology that is based on all four categories of national identity (concept of ethnic belonging, concept of civic belonging, nationalism, and patriotism) while accounting for the fact that they overlap empirically. Second, to investigate how this typology correlates with different forms of religiosity (institutionalized religious practice, religious dogmatism) and spirituality.

Our empirical study of religion and national identity in Eastern and Central Europe seeks answers to four research questions:

- Can we identify a clear common typology of national identity in Central and Eastern Europe based on categories of nationalism, patriotism, ethnic and civic concepts of national belonging?

If we can, then the following questions arise:

- 2.

- To what extent are the types identified represented in the countries of the region? What differences can be observed between the countries?

- 3.

- How does a religious and denominational concept of national belonging relate to the types of national identity identified?

- 4.

- What is the relationship between the types of national identity and different forms of religiosity and spirituality?

As our research on typology formation is mainly exploratory in nature, we have not formulated formal hypotheses for the first question. Regarding our second question, given the discussion surrounding Kohn’s dichotomy between “Western” and “Eastern” nationalisms and the prevailing tenor of recent quantitative research on national identity (Jones and Smith 2001a, 2001b; Bahna et al. 2009; Helbling et al. 2016; and others), we expect exclusivist positions to be widespread throughout the region. Given the historically close connection between Orthodoxy and nationhood, as well as the resurgence of Orthodox civilizational chauvinism after 1989 (Roudometof 1999, 2014; Ramet 2019), we also expect forms of national identity associated with exclusivism and superiority to be particularly prevalent in countries with Orthodox traditions. As for the third question, we expect, based on the majority classification in the literature to date (cf. Jones and Smith 2001a; Helbling et al. 2016; Ariely 2020 or Guglielmi and Piacentini 2024), a religiously defined concept of belonging to be more closely linked to exclusivist concepts of national identity than to more open concepts. Regarding the fourth question, we expect, in agreement with Trittler (2017), different forms of religiosity to be associated with different expressions or conceptions of national identity. Given the findings of classical social-psychological research on prejudice and the results of research on political tolerance (see Section 3), we expect religious dogmatism, as an expression of a generally rigid and exclusivist way of thinking, to be most strongly associated with exclusivist and ascriptive types of national identity. It is difficult to formulate a definitive and universally valid hypothesis regarding institutionalized religious practice. Ultimately, the specific context of the institution, its norms and teachings, and its position on the nexus between religion and the nation, are likely to play a significant role here. Following the claim made by Spohn (1998, 2012) and others (see Section 1) that religion acts more strongly as a symbolic boundary in Central and Eastern than in Western Europe, we nevertheless expect institutionalized religious practice also to exhibit a proximity to exclusivist forms of national identity. In contrast, being a more open and individualistic concept (see Hughes 2013), spirituality should go hand in hand with more open and inclusive forms of national identity.

5. Data and Methods

5.1. Data

Our empirical analysis is based on a secondary analysis of existing international data. While many international comparative analyses of national belonging use the “National Identity” module of the International Social Survey Program (ISSP) research series as their data source, we opted for a different database: namely, the Pew Research Center’s “Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe” study (Sahgal and Cooperman 2024). We did so for several reasons. First, this study is somewhat more recent than the latest available database of the ISSP “National Identity” module (2013).2 Second, it covers the Central and Eastern European (CEE) region much more extensively than the ISSP, which only included a few selected countries from CEE. Third, unlike the ISSP module, the Pew study contains a wider range of religiosity variables, which allows us to capture religiosity more broadly in terms of our research question.

The Pew study was conducted as a face-to-face survey in 18 Eastern and Central European countries between June 2015 and July 2016. Since an important factor for us in terms of examining the region was the shared communist past, we excluded the only non-post-communist state, Greece, from our study. We also excluded Kazakhstan, which is geographically not part of the region that we studied. In addition, for methodological reasons, we also did not include Belarus in the analysis, as it showed a very different pattern to all other countries in terms of the relationship between types of national identity.3

Having selected the countries, we then narrowed the data used for our analysis further. Since the questions on national affiliation and patriotism were formulated in relation to the survey countries, we conducted our analysis, as Coenders (2001) also suggests, only on persons belonging to the dominant ethnic group in the country concerned. The obvious reason for this is that, for persons belonging to ethnic minority groups (e.g., Russians in Latvia, Hungarians in Romania), the question about the characteristics of the majority national identity is not necessarily related to their own identity.

5.2. Measures

To create the most efficient and clear typology of national identity possible, we operationalized the underlying concepts of nationalism, patriotism, ethnic and civic belonging with a single question from the questionnaire used in the study. In making our selection, we focused on items that the literature has shown to be empirically unambiguous and/or most convincing in terms of content and concept.

5.2.1. National Identity

To measure a descriptive-ethnic concept of belonging, we followed the recommendations of Kunovich (2009), Reeskens and Hooghe (2010), Wright et al. (2012), and Ariely (2020), and selected a question that focuses on the importance of “correct” family ancestry.4 Also following the same authors, we took as the criterion for a voluntarist-civic concept of belonging the fulfilment of basic civic duties in the form of respecting the country’s institutions and laws.5

As for nationalism, we follow the line of thinking that views it as an attitude that, in addition to positive references to one’s own nation, disparages others (Citrin et al. 2001). Accordingly, we measure it using a question that links national sentiment with a chauvinistic sense of superiority.6 We understand patriotism as a concept that refers positively to one’s own nation but is not necessarily associated with the devaluation of others (Kemmelmeier and Winter 2008). We measure patriotism by asking about the extent of general national pride.7

5.2.2. Religion, Religiosity, and Spirituality

We measure a religiously oriented concept of belonging based on agreement with the statement that, to be a “true” member of the national community, a person must belong to the “right” religion.8

Regarding individual religiosity, we first use one of the most common indicators for traditional institutionalized religiosity: namely, the frequency of participation in religious services.9 Second, we measure religious dogmatism using a question that expresses the exclusivity of one’s own religion by capturing the opinion that there is only one interpretation of one’s own religion.10

Additionally, we measure spirituality on the basis of a question that focuses on the deep connection with nature and the earth. However, when measuring spirituality, the question arises as to what extent it overlaps with traditional religiosity (Zinnbauer et al. 1997; Pollack and Rosta 2017). To separate spirituality and religiosity, we follow the idea of building a category “spiritual but not religious” (SBNR; Fuller 2001; Ammerman 2013). Unlike others who measure this category directly with a single question, though, we derive it from a combination of separate measurements of religiosity and spirituality. Since the questionnaire did not include a direct question on religious self-identification, we combined religious centrality, i.e., the individual importance of religion, with the question on spirituality to create a group of people who are spiritual but do not consider religion important in their lives.11

5.3. Data Analysis

To create common types of national identity, we performed k-means cluster analysis on a joint sample of the 16 countries included in the analysis, first with random initial cluster centres, then with cluster centres specified according to the results and theoretical considerations.12 We started from the assumption that the elements of the two concepts will overlap, with most people who can be characterized as nationalists also being patriots (but not necessarily vice versa), and a significant proportion of people who profess ethnic-based national affiliation also identifying with the civic criterion (but not necessarily vice versa). We also used results based on a similar Pew study on Western Europe (Pew Research Center 2018b), where we were able to identify four clusters that formed a kind of scale: nationalism representing the most extreme form of national identification, having a high degree of agreement with all four statements; a second group being not nationalist but patriotic and having an ethnic-based concept of nationhood; a third group having patriotic attitudes associated with a civic concept of national belonging; and a fourth group characterized only by a civic concept of nationhood, without nationalist, ethnic or patriotic attitudes.

In a second step, we examined the frequency of the classification in the countries of the region to emphasize regional differences based on the prevalence of the types. Finally, we used bivariate analyses to examine on a country-by-country basis the relationship between the typology of national identity, religious dogmatism, institutionalized religious practice, and spirituality. Here, we focused on the differences in the prevalence of certain types of national identity within different forms of religiosity.

6. Results

6.1. A Typology of National Identity

As already mentioned, one of the goals of our study is to detect certain types of attitudes towards the nation while considering their empirical overlaps. With the help of k-means cluster analysis on the common database of 16 countries, based on the silhouette values13 and theoretical interpretability, we decided on a three-cluster solution. These three clusters demonstrate the scale-like nature of the typology. In the case of a four-cluster solution, the fourth cluster no longer follows this scale pattern, but shows middle-range values for all four variables, making it difficult to interpret. Thus, in our typology, unlike in Western Europe, the fourth type, “civic,” does not form a separate cluster.

Members of the first type (“nationalist”) agree with all four statements, meaning that they are not only proud of their nation, but also feel a sense of superiority towards it, and expect not only respect for the country’s laws and institutions, but also that members of the nation will have family ties. The second type (“ethnic”) is not chauvinistic, but national pride is associated with an ethnic image of the nation (which, however, also includes acceptance of the legal system and institutions). In the third type (“patriotic”), non-chauvinistic national pride is associated with a civic interpretation of national identity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Types of national identity and their characteristics.

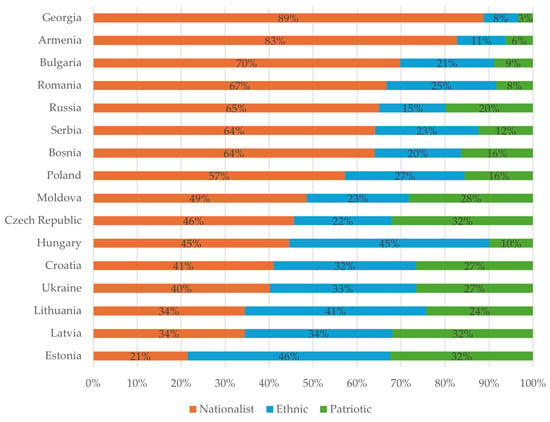

Looking at the distribution of the three types in Figure 1, it is immediately apparent that nationalist and ethnic concepts of national identity are widespread throughout the region. This confirms our assumption that concepts of national identity in CEE are characterized by a pronounced exclusivist nature.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of the types of national identity by country. (Source: Sahgal and Cooperman (2024), own computation).

As regards the differences between countries, what appears at first glance to be a decisive factor is the respective degree of secularization. Highly religious countries such as Georgia, Armenia, and Romania appear to have a higher proportion of nationalists than less religious countries such as Estonia and Latvia. However, “outliers” such as Croatia and the Czech Republic indicate that the decisive factor is not the level of secularization but rather the confessional context. The nationalist type dominates in most countries with an Orthodox majority (e.g., Russia, Georgia, Serbia). In countries with a Catholic tradition (Poland, Croatia, Hungary), the proportion of nationalists is smaller but still significant. At the same time, in the Baltic states and Hungary, the ethnic type is at least as prominent as the nationalist type, indicating a strong emphasis on ancestry and ethnic heritage without necessarily implying chauvinism. Patriotism is most widespread in Protestant-influenced contexts (Estonia, Latvia, but also the Czech Republic). Regarding our second research question, the expectation is confirmed that Orthodoxy, in comparison to Catholicism and Protestantism, is particularly strongly associated with chauvinistic and exclusivist notions of nationality.

6.2. National Identity, Religion, Religiosity, and Spirituality

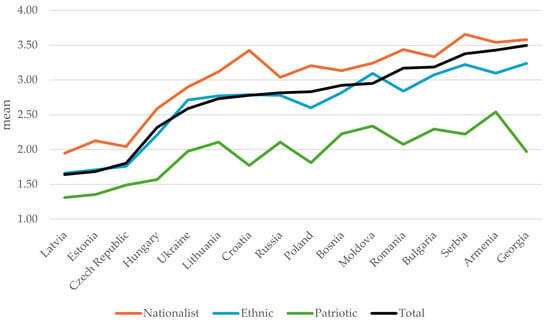

We will now turn our attention to the question of how the diverse types of national identity relate to a religious understanding of national belonging, various forms of religiosity, and spirituality. Regarding the relationship between types of national identity and the importance of religion for national belonging, we can observe a characteristic pattern in all countries of the CEE region (Figure 2). Nationalists consistently consider a person’s affiliation to the dominant religion to be of above-average importance for national identity. This applies even in highly secularized countries such as Estonia and the Czech Republic. The ethnic type that roughly corresponds to the respective national average in most countries ranks second in terms of the importance of religion for national identity. For patriots, religion plays a rather minor role in national identity. Overall, the difference between countries in terms of the general importance of religion for national identity is much less pronounced among patriots than among the other two types. The results reflect the fact that ethnic and religious boundaries are often blurred in the region. Religion indeed functions as a symbolic boundary marker, which, however, not only has an ethnically exclusivist effect, but is also often associated with chauvinism.

Figure 2.

Importance of dominant confession for national belonging, by type of national identity and country. (Source: Sahgal and Cooperman (2024), own computation).

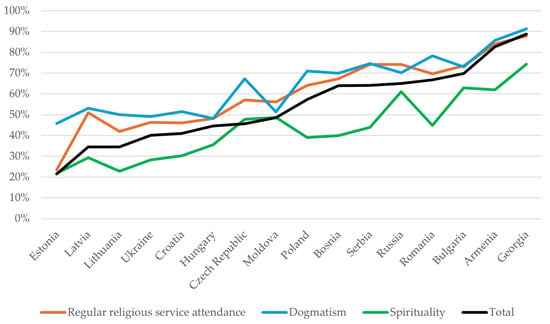

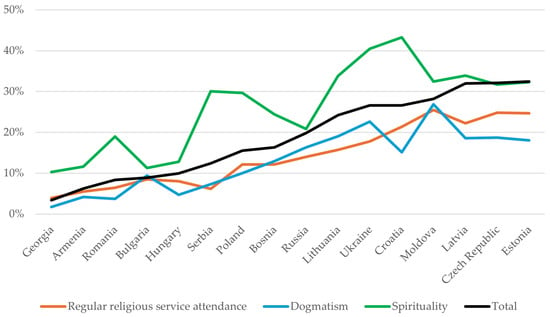

Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 reveal systematic associations between religious dogmatism, institutionalized religious practice, spirituality, and national identity in Central and Eastern Europe. In line with our expectations, the nationalist type is overrepresented among those sharing a dogmatic view of their own religion, and underrepresented among those with a spiritual but not religious (SBNR) orientation (Figure 3). Institutionalized religious practice (attending churches or mosques) tends to fall between the other two forms, but in almost all countries, it is associated with nationalist attitudes at an above-average rate. This confirms not only our assumption that institutionalized religious practices in Central and Eastern Europe tend to go hand in hand with ethnically oriented, exclusive forms of national identity. Like religious dogmatism (albeit to a lesser extent), institutionalized religious practice often accompanies chauvinistic attitudes.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of nationalism, by religiosity and spirituality. (Source: Sahgal and Cooperman (2024), own computation).

Figure 4.

Prevalence of ethnic national identity, by religiosity and spirituality. (Source: Sahgal and Cooperman (2024), own computation).

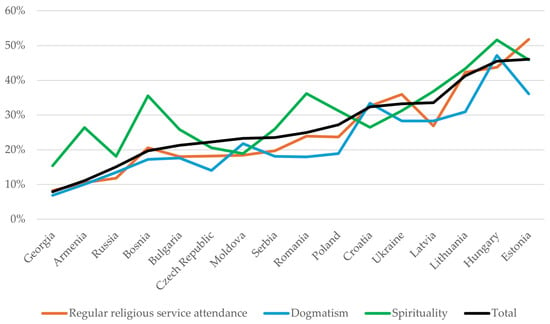

Figure 5.

Prevalence of patriotism, by religiosity and spirituality. (Source: Sahgal and Cooperman (2024), own computation).

However, there are also interesting differences between countries. In countries with a high proportion of nationalists like Russia, Georgia, and Armenia, the relationship between religiosity, whether in its dogmatic form or as a regular practice, and nationalism is less striking—simply because nationalism is widespread in all strata of society. Here, religious dogmatism and regular religious practice do not have a significant distinguishing effect on national identity. In more secular and less nationalist countries (the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, and partly Hungary), where religiosity per se cannot be considered as a general norm, the minority of religious people are much more likely to be nationalist than the non-religious majority. This applies in particular to religiously dogmatic individuals, but also to those who regularly practise their religion. So, religiosity in general is a strong predictor of nationalism precisely where nationalism itself in its pure form is rather rare (Figure 1). This might fit with the cultural defence thesis (Bruce 2002): in societies where both religion and nationalism are weaker, religious people, as a minority, are more likely to fuse their faith with national identity as a way of preserving distinctiveness. In other words, religiosity serves as a “carrier” of nationalism in secular contexts, even if nationalism is not broadly shared.

The ethnic type shows the weakest association with religiosity and spirituality at the country level (Figure 4). The differences between those who regularly attend religious services, dogmatic believers, and SBNR persons are smaller than what we see for the nationalist or patriotic types. The relative frequency of this type can be considered close to average among the dogmatic believers, regular service attenders, and SBNR individuals in most countries. This might be explained by the fact that, if religiosity strengthens ethnic identity, it is more likely than average to be accompanied by nationalist-chauvinistic attitudes, as we saw in the previous Figure.

In contrast to the pattern that we found in the case of nationalism, patriotism is underrepresented among individuals with dogmatic orientations and among those who practise regularly, which again indicates that not only religious dogmatism but (to a lesser extent) also traditional institutional religiosity in Central and Eastern Europe tend to align more with exclusivist conceptions, rather than with civic conceptions. In contrast, patriotism is overrepresented among the group of SBNR persons, which supports the hypothesis that spirituality, compared to religious dogmatism and institutionalized religious practice, is more closely associated with civic and inclusive forms of national identity.

In some countries (Serbia, Croatia, Ukraine, Poland), the patriotic type is particularly overrepresented among SBNR persons, while in other countries in this group it is represented rather averagely. This suggests that in some countries of the region, there is a particularly significant polarization of attitudes towards national identity along dogmatic and institutionalized forms on the one hand, and non-institutionalized spirituality on the other (Figure 5).

7. Conclusions

Our study examined the complex relationship between national identity, religion, and religiosity in Central and Eastern Europe by going beyond established dichotomies on the one hand, and including various forms of religiosity and spirituality in the investigation on the other. Our first objective was to develop a nuanced empirical typology of national identity that integrates four key dimensions (nationalism, patriotism, ethnic, and civic concepts of belonging), taking conceptual overlaps into account. In line with our second objective, we investigated the prevalence of the different types of national identity in CEE, and how this typology correlates with a religiously oriented concept of national belonging as well as with different forms of religiosity (institutional religious practice and religious dogmatism) and non-religious spirituality.

Using k-means cluster analysis on data from the Pew Research Center’s Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe survey across 16 post-communist countries, we identified a robust, three-cluster typology of national identity. The nationalist, ethnic, and patriotic types that we found form a conceptual scale of exclusionary and inclusive attitudes.

The nationalist cluster represents the most exclusivist form of national identity. Members of this group show a high level of agreement with all four variables: respecting laws and institutions (civic criteria), exhibiting national pride (patriotism), adhering to ethnic criteria (family background), and, crucially, feeling a sense of superiority towards other cultures (chauvinism/nationalism). The ethnic type combines patriotism and a civic understanding of national belonging with the emphasis of ethnic affiliation criteria for national belonging, and thus also represents a rather exclusive position about national identity, albeit without any chauvinistic components. The patriotic type represents the most open, non-exclusivist orientation, associating national pride primarily with the civic interpretation of national identity and rejecting ethnic and chauvinistic criteria. While exclusivist positions predominate overall in all countries, the prevalence of the respective types varies systematically between countries and corresponds to the historical and cultural contexts. It is particularly noteworthy that the nationalist type is most prevalent in countries with an Orthodox tradition. Eastern Orthodoxy does indeed seem to provide particularly fertile ground for chauvinistic positions.

Our analysis of the relationship of national identity with religion, religiosity, and spirituality revealed clear and significant patterns. There is a distinct hierarchy regarding the perceived importance of religion for national belonging: nationalists consistently rate it as being of above-average importance, followed by the ethnic type near the national average, and patriots, who view it as less important. This pattern, which holds even in secularized nations, reflects the regional blurring of ethnic and religious boundaries, where religion functions as an ethnically exclusive symbol, often even accompanied by chauvinism.

Religious dogmatism and, to a lesser extent, institutionalized religious practice show a positive correlation with exclusivist positions. It is noteworthy that not only religious dogmatism, which is perhaps less surprising, but also institutionalized religious practice is associated not with ethnically oriented concepts of belonging solely, but with nationalistic and chauvinistic positions, too. This seems to confirm those voices that attribute an often-problematic role to religion in connection with national identity (cf. Kunovich 2006; Ariely 2020; Guglielmi and Piacentini 2024).

However, our analyses have also shown that it is important to consider different forms of religiosity or spirituality, as not all of them have the same effect. Open, individualistic, and undogmatic forms can have an integrative effect: non-religious spirituality shows an above-average affinity for non-exclusivist patriotism.

In conclusion, this paper makes two key contributions. First, it offers an empirically grounded typology that captures the overlapping yet distinct nature of national identity in Central and Eastern Europe. Second, it demonstrates conclusively that the link between religion and national identity is not monolithic. The findings underscore the critical importance of distinguishing between different forms of religiosity and spirituality: while particularly religious dogmatism, but also traditional, institutionalized religiosity, tend to reinforce exclusive nationalist-chauvinistic attitudes, non-institutional spirituality aligns rather with more inclusive, civic attitudes. This distinction is crucial for understanding the complex connection between religion and national identity in the region.

Our study is, of course, far from providing a comprehensive answer to the question of the relationship between national identity and religion in Central and Eastern Europe. Our primary concern here was to uncover characteristic patterns from a quantitative and comparative perspective. We could not provide deeper insights into the historical peculiarities of individual countries and path dependencies at this point. Regarding current contextual factors beyond denominational tradition, we were also unable to go into detail in this article. In-depth case studies could consider aspects such as the development of civil society, the level of socioeconomic development, the degree of democratization, and specific experiences with the transformation process as determining factors. Furthermore, we do not have a satisfactory explanation for all the patterns that we found. It would certainly be worthwhile to investigate the differences between Catholic and Protestant-dominated countries in terms of the prevalence of exclusivist and inclusive concepts of national identity. The question of the relevance of minority and majority constellations within countries for the relationship between national identity and religion should also be examined in more detail in further studies. The specificity of religion in Central and Eastern Europe could be brought into even sharper focus if a systematic East–West comparison was to be conducted. Finally, we must point out that, based on the available data, we are presenting the situation as it was around ten years ago. In view of the partly dramatic changes in the political situation in the region in recent years, it would be desirable for future studies to address these issues based on more recent data or even from a longitudinal perspective. This would make it possible to find out how predetermined and stable the attitudes and correlations we have examined are.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.M. and G.R.; methodology, O.M. and G.R.; software, G.R.; validation, O.M. and G.R.; formal analysis, O.M. and G.R.; investigation, O.M. and G.R.; resources, O.M. and G.R.; data curation, O.M. and G.R.; writing—original draft preparation, O.M. and G.R.; writing—review and editing, O.M. and G.R.; visualization, G.R.; supervision, O.M.; project administration, O.M.; funding acquisition, O.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Excellence Initiative 2019–2025 of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (EXC 2060: Religion und Politik. Dynamiken von Tradition und Innovation; grant number 390726036).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. We used an existing database for secondary analysis; no new data collection was conducted.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The PEW data used in this paper can be obtained here: https://www.pewresearch.org/dataset/eastern-european-survey-dataset/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank David West for linguistic corrections.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CEE | Central and Eastern Europe |

| ISSP | International Social Survey Programme |

| SBNR | Spiritual but not religious |

Notes

| 1 | Russia, as the centre of the Tsarist Empire, was an exception, where the dominant Orthodox Church was also able to develop into a vital component of national identity, partly because of its traditionally close ties to the state (cf. Spohn 2012, p. 41). |

| 2 | The integrated database for the fourth wave of this module (2023) is not yet accessible and is expected to be published in early 2026. |

| 3 | In investigating whether the types found via cluster analysis form a Guttman or Mokken scale, Belarus showed much lower values than the other countries in terms of both the Coefficient of Reproducibility and Loevinger’s coefficient H. We can only guess the reason for this, but the fact that the results are difficult to comprehend might be due to the authoritarian conditions under which the survey was conducted. |

| 4 | The wording of the question is as follows: “Some people say that the following things are important for being truly [SURVEY COUNTRY CITIZENSHIP]. Others say that they are not important. How important do you think each of the following is?—To have (SURVEY COUNTRY CITIZENSHIP) family background” (4-point scale, 1 = not at all important, 4 = very important; recoded into the reversed direction). |

| 5 | For the wording of the question, see the previous note. Item text: “To respect the country’s institutions and laws”. |

| 6 | “Please tell me if you completely agree, mostly agree, mostly disagree or completely disagree with the following statement(s)?—Our people are not perfect, But our culture is superior to others” (4-point scale, 1 = completely disagree, 4 = completely agree; recoded into the reversed direction). |

| 7 | “How proud are you to be a citizen of (survey country)? Very proud, somewhat proud, not very proud, or not proud at all (4-point scale, 1 = not proud at all, 4 = very proud; recoded into the reversed direction). |

| 8 | The item comes from the same set of questions as the other items pertaining to belonging. For the wording of the question, see note 4. The item is “To be a (INSERT DOMINANT DENOMINATION OF SURVEY COUNTRY, FOR EXAMPLE RUSSIAN ORTHODOX, GREEK ORTHODOX ETC.)”. |

| 9 | The Pew study measured this with a separate question among Muslims and other respondents. While non-Muslims were generally asked about how often they participated in religious services other than weddings and funerals, Muslims were asked how often they attend the mosque for salah, the daily ritual prayers. The combined frequency of ceremony attendance was computed by combining these two questions. Question wording for non-Muslims: “Aside from weddings and funerals, how often do you attend religious services … more than once a week, once a week, once or twice a month, a few times a year, seldom, or never?” For Muslims: “On average, how often do you attend the mosque for salah? More than once a week, once a week for Friday afternoon Prayer, once or twice a month, a few times a year, especially for Eid, seldom or never?” |

| 10 | The wording of the question: “Please tell me whether the first statement or the second statement is most similar to your point of view—even if it does not precisely match your opinion” (1 = There is only one true way to interpret the teachings of my religion, 2 = There is more than one true way to interpret the teachings of my religion, 3 = neither/both equally). This question was only asked of those who have a religious affiliation. |

| 11 | In doing so, we relied on the recognition that although religiosity and the individual importance of religion are not identical concepts, they are closely related, as indicated by the strong positive correlation between the two (Huber and Huber 2012; Svob et al. 2019). The wordings of the questions from which we constructed the SBNR category are: “How often, if at all, do you feel a deep connection with nature and the earth” (4-point scale, 1 = never, 4 = often; recoded into the reversed direction); “How important is religion in your life—very important, somewhat important, not too important or not at all important?” (4-point scale, 1 = not at all important, 4 = very important; recoded into the reversed direction). We considered those who scored 3 or 4 on the spirituality question and 1 or 2 on the importance of religion to belong to the SBNR category. |

| 12 | Cluster analysis is a method of multivariate data analysis that divides objects into groups (clusters) based on several characteristics in such a way that the elements within a cluster are as homogeneous (similar) as possible, but the clusters themselves are as heterogeneous (dissimilar) as possible (Everitt et al. 2001). |

| 13 | The silhouette coefficient is an internal clustering validity index that measures how well each object lies within its assigned cluster compared to other clusters (Kaufman and Rousseeuw 1990). |

References

- Adorno, Theodor W., Else Frenkel-Brunswik, Daniel J. Levinson, and R. Nevitt Sanford. 1950. The Authoritarian Personality. New York: Harper & Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Alemán, José M., and Dwayne Woods. 2017. Inductive Constructivism and National Identities: Letting the Data Speak. Nations and Nationalism 24: 1023–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, Gordon W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Reading: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, Gordon W., and J. Michael Ross. 1967. Personal Religious Orientation and Prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5: 432–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemeyer, Bob, and Bruce Hunsberger. 1992. Authoritarianism, Religious Fundamentalism, Quest, and Prejudice. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 2: 113–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2013. Spiritual But Not Religious? Beyond Binary Choices in the Study of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 258–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariely, Gal. 2012. Globalisation and the Decline of National Identity? An Exploration Across Sixty-three Countries. Nation and Nationalism 18: 461–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariely, Gal. 2013. Nationhood across Europe: The Civic-Ethnic Framework and the Distinction between Western and Eastern Europe. Perspectives on European Politics and Society 14: 123–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariely, Gal. 2020. Measuring Dimensions of National Identity across Countries: Theoretical and Methodological Reflections. National Identities 22: 265–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahna, Miloslav, Magdalena Pisková, and Miroslav Tižik. 2009. Shaping of National Identity in the Processes of Separation and Integration in Central and Eastern Europe. In The International Social Survey Programme 1984–2009. Charting the Globe. Edited by Max Haller, Roger Jowell and Tom W. Smith. London: Routledge, pp. 246–66. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, David M. 2020. The Relationship Between Religious Nationalism, Institutional Pride, and Societal Development: A Survey of Postcommunist Europe. Journal of Developing Societies 36: 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C. Daniel, Patricia Schoenrade, and W. Larry Ventis. 1993. Religion and the Individual: A Social-Psychological Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter L., ed. 1999. Desecularization of the World. Resurgent Religion and World Politics. Washington, DC and Grand Rapids: Ethics and Public Policy Center/Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, Thomas, and Peter Schmidt. 2003. National Identity in a United Germany: Nationalism or Patriotism? Political Psychology 24: 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowik, Irena. 2002. Between Orthodoxy and Eclecticism: On the Religious Transformations of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine. Social Compass 49: 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breskaya, Olga, and Siniša Zrinščak. 2024. Religion, Moral Issues and Politics: Exploring Profiles in CEE. In Change and Its Discontents: Religious Organizations and Religious Life in Central and Eastern Europe (Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion 15). Edited by Olga Breskaya and Siniša Zrinščak. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 42–75. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, Marilynn B. 1999. The Psychology of Prejudice: Ingroup Love and Outgroup Hate? Journal of Social Issues 55: 429–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, David. 1999. Are There Good and Bad Nationalisms? Nations and Nationalism 5: 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, Rogers. 1992. Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, Rogers. 1996. Nationalism Reframed: Nationhood and the National Question in the New Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Steve. 2002. God Is Dead: Secularization in the West. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 1994. Public Religions in the Modern World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 1998. Between Nation and Civil Society: Ethnolinguistic and Religious Pluralism in Independent Ukraine. In Democratic Civility: The History and Cross-Cultural Possibility of a Modern Political Ideal. Edited by Robert W. Hefner. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, pp. 203–28. [Google Scholar]

- Citrin, Jack, Beth Reingold, and Donald P. Green. 1990. American Identity and the Politics of Ethnic Change. The Journal of Politics 52: 1124–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citrin, Jack, Cara Wong, and Brian Duff. 2001. The Meaning of American National Identity: Patterns of Ethnic Conflict and Consensus. In Social Identity, Intergroup Conflict, and Conflict Reduction. Edited by Richard D. Ashmore, Lee Jussim and David Wilder. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 71–100. [Google Scholar]

- Coenders, Marcel. 2001. Nationalistic Attitudes and Ethnic Exclusionism in a Comparative Perspective. An Empirical Study of Attitudes Toward the Country and Ethnic Immigrants in 22 Countries. Ph.D. dissertation, Catholic University of Nijmegen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Davidov, Eldad. 2010. Nationalism and Constructive Patriotism: A Longitudinal Test of Comparability in 22 Countries with the ISSP. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 23: 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Figueiredo, Rui J. P., Jr., and Zachary Elkins. 2003. Are Patriots Bigots? An Inquiry into the Vices of In-Group Pride. American Journal of Political Science 47: 171–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, Henk, Darina Malová, and Sander Hoogendoorn. 2003. Nationalism and Its Explanations. Political Psychology 24: 345–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doktór, Tadeusz. 2001. Discriminatory Attitudes towards Controversial Religious Groups in Poland. In Religion and Social Change in Post-Communist Europe. Edited by Irena Borowik and Miklós Tomka. Kraków: NOMOS, pp. 149–62. [Google Scholar]

- Doktór, Tadeusz. 2007. Religion and National Identity in Eastern Europe. In Church and Religious Life in Post-Communist Societies. Edited by Edit Révay and Miklós Tomka. Budapest and Piliscsaba: Loisir, pp. 299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Doob, Leonard W. 1964. Patriotism and Nationalism: Their Psychological Foundations. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, Christopher G., and Marc A. Musick. 1993. Southern Intolerance: A Fundamentalist Effect? Social Forces 72: 379–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, Brian S., Sabine Landau, and Morven Leese. 2001. Cluster Analysis. London: Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Fleiß, Jürgen, Franz Höllinger, and Helmut Kuzmics. 2009. Nationalstolz zwischen Patriotismus und Nationalismus? Empirisch-methodologische Analysen und Reflexionen am Beispiel des International Social Survey Programme 2003 „National Identity”. Berliner Journal für Soziologie 19: 409–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, Robert C. 2001. Spiritual, But Not Religious: Understanding Unchurched America. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfeld, Liah. 1992. Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grigoryan, Lusine K., and Vladimir Ponizovskiy. 2018. The Three Facets of National Identity: Identity Dynamics and Attitudes Toward Immigrants in Russia. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 59: 403–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzymala-Busse, Anna. 2015. Nations Under God. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grzymala-Busse, Anna. 2019. Religious Nationalism and Religious Influence. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. New York: Oxford University Press. 21p. [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmi, Simona, and Arianna Piacentini. 2024. Religion and National Identity in Central and Eastern European Countries: Persisting and Evolving Links. East European Politics and Societies 38: 455–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbling, Marc, Tim Reeskens, and Matthew Wright. 2016. The Mobilisation of Identities: A Study on the Relationship Between Elite Rhetoric and Public Opinion on National Identity in Developed Democracies. Nations and Nationalism 22: 744–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschhausen, Ulrike von, and Jörn Leonhard. 2001. Europäische Nationalismen im West-Ost-Vergleich: Von der Typologie zur Differenzbestimmung. In Nationalismen in Europa: West- und Osteuropa im Vergleich. Edited by Ulrike von Hirschhausen. Göttingen: Wallstein, pp. 11–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hjerm, Mikael. 1998. National Identity: A Comparison of Sweden, Germany and Australia. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 24: 451–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjerm, Mikael, and Annette Schnabel. 2010. Mobilizing Nationalist Sentiments: Which Factors Affect Nationalist Sentiments in Europe? Social Science Research 39: 527–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochman, Oshrat, Rebeca Raijman, and Peter Schmidt. 2016. National Identity and Exclusion of Non-ethnic Migrants. In Dynamics of National Identity: Media and Societal Factors of What We Are. Edited by Jürgen Grimm, Leonie Huddy, Peter Schmidt and Josef Seethaler. London: Routledge, pp. 64–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppenbrouwers, Frans. 2002. Winds of Change: Religious Nationalism in a Transformation Context. Religion, State & Society 30: 305–16. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan, and Odilo W. Huber. 2012. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). Religions 3: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddy, Leonie. 2016. Unifying National Identity Research. In Dynamics of National Identity: Media and Societal Factors of What We Are. Edited by Jürgen Grimm, Leonie Huddy, Peter Schmidt and Josef Seethaler. London: Routledge, pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Huddy, Leonie, Alessandro Del Ponte, and Caitlin Davies. 2021. Nationalism, Patriotism, and Support for the European Union. Political Psychology 42: 995–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Philip C. 2013. Spirituality and Religious Tolerance. Implicit Religion 16: 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsberger, Bruce. 1995. Religion and Prejudice: The Role of Religious Fundamentalism, Quest, and Right-Wing Authoritarianism. Journal of Social Issues 51: 113–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, Samuel P. 1993. The Clash of Civilizations? Foreign Affairs 72: 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayet, Cyril. 2012. The Ethnic-Civic Dichotomy and the Explanation of National Self-Understanding. European Journal of Sociology 53: 65–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Frank L., and Philip Smith. 2001a. Diversity and Commonality in National Identities: An Exploratory Analysis of Cross-National Patterns. Journal of Sociology 37: 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Frank L., and Philip Smith. 2001b. Individual and Societal Bases of National Identity. A Comparative Multi-Level Analysis. European Sociological Review 17: 103–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpov, Vyacheslav. 2002. Religiosity and Tolerance in the United States and Poland. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: 267–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpov, Vyacheslav, Elena Lisovskaya, and David Barry. 2012. Ethnodoxy: How Popular Ideologies Fuse Religious and Ethnic Identities. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 638–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasianenko, Nataliia. 2020. Measuring Nationalist Sentiments in East-Central Europe: A Cross-National Study. Ethnopolitics 21: 352–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Leonard, and Peter J. Rousseeuw. 1990. Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmelmeier, Markus, and David G. Winter. 2008. Sowing Patriotism, But Reaping Nationalism? Consequences of Exposure to the American Flag. Political Psychology 29: 859–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, Hans. 1944. The Idea of Nationalism: A Study in Its Origins and Background. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kosterman, Rick, and Seymour Feshbach. 1989. Toward a Measure of Patriotic and Nationalistic Attitudes. Political Psychology 10: 257–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunovich, Robert M. 2006. An Exploration of the Salience of Christianity for National Identity in Europe. Sociological Perspectives 49: 435–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunovich, Robert M. 2009. The Sources and Consequences of National Identification. American Sociological Review 74: 573–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunovich, Robert M., and Randy Hodson. 1999. Conflict, Religious Identity, and Ethnic Intolerance in Croatia. Social Forces 78: 643–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kymlicka, Will. 2000. Nation-Building and Minority Rights: Comparing West and East. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 26: 183–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kymlicka, Will. 2001. Politics in the Vernacular: Nationalism, Multiculturalism, and Citizenship. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, Christian Albrekt. 2017. Revitalizing the ‘Civic’ and ‘Ethnic’ Distinction. Perceptions of Nationhood across Two Dimensions, 44 Countries and Two Decades. Nations and Nationalism 23: 970–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latcheva, Rossalina. 2011. Cognitive Interviewing and Factor-analytic Techniques: A Mixed Method Approach to Validity of Survey Items Measuring National Identity. Quality & Quantity 45: 1175–99. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Qiong, and Marilynn B. Brewer. 2004. What Does it Mean to Be an American? Patriotism, nationalism, and American identity after 9/11. Political Psychology 25: 727–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, David. 1978. A General Theory of Secularization. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Molnár, Attila K. 2006. Civil or Ethnic Religion: The Case of Hungary. In Religions, Churches and Religiosity in Post-Communist Europe. Edited by Irena Borowik. Krakow: NOMOS, pp. 279–90. [Google Scholar]

- Mußotter, Marlene. 2022. We Do Not Measure What We Aim to Measure: Testing Three Measurement Models for Nationalism and Patriotism. Quality & Quantity 56: 2177–97. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2017. Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe. Report. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2018a. Being Christian in Western Europe. Report. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2018b. Being Christian in Western Europe. Dataset. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]