Abstract

Scholarship on representations of sonic events in the medieval world has often focused on literary productions, analysing the ways in which texts describe sounds and their effects with words. What has not been thoroughly examined is the relationship between such literary representations and their manifestations in material culture, most prominently in the form of manuscript images. Employing a combined approach drawing from neurobiological predictive processing and Liam Lewis’s framework of the ‘sound milieu’, this article examines representations of sonic events in British Library, Harley MS Y.6, which pictorially depicts the life of St Guthlac in 18 roundels, in conversation with textual depictions in various vitae of the saint. Through this analysis, the article demonstrates that early medieval images were encountered multimodally, with sound milieus created from the sonic information in illustrations allowing an immersive interaction with subjects like St Guthlac.

1. Introduction

Spiced incense on the air, song reverberating off stone, flare of light on gold, the hope of the divine brushing human skin, healing body and soul. It is hard to overstate the intense sensory experience of medieval English saint’s shrines. From the lowly stone marker to the bejewelled and towering reliquary, the sacred centres of saint’s cults were locations of physical, mental, and spiritual immersion. They were environments structured to shape multisensory engagement with their respective saint, with one of the most important sensory avenues being sound.1 While scholarship on representations of sonic events in the medieval world has grown substantially in recent years, particularly in relation to literary productions and the ways texts describe sounds and their effects, one area has remained relatively unexamined: the relationship between literary representations of aural information and their manifestations in material culture, most prominently in the form of manuscript images.2 For many pilgrims, excepting those of high status and literate education, sound would have functioned as one of if not the primary means by which they could access information about the saint, their miracles, and, by verbal prayer, call for their intercession. This article will argue that medieval English images based on literary constructions were often encountered multimodally, and that visual depictions of sonic events in the context of saints and their attendant pilgrimage locations functioned by sounding silent ink and pigments in a variety of ways.

The interwoven relationships between sonic information at the heart of this research, whether textual, visual, or experiential, can be helpfully conceptualised through a combination of recent advances in neurobiology and the theoretical framework of the ‘sound milieu’, as applied in Liam Lewis’ Animal Soundscapes in Anglo-Norman Texts (Lewis 2022).3 In the former, this article will employ a narrow form of auditory imagery based within the model of predictive processing, which can be defined in the following way: the human brain generates predictions of sensory input based on lived experience, even to the point where silent images strongly associated with specific sounds (a static image of a dog barking) lead to subtle activation of the auditory cortex (areas of the brain associated with processing sound).4 These auditory images have been demonstrated to affect human perception of artistic imagery, including features like aesthetic value and level of immersive experience (Iosifyan et al. 2022). In the latter, drawing from Jakob von Uexküll’s ‘notion of umwelt (‘world-around’, also translated as ‘milieu’)’, Lewis theorises the sound milieu as describing ‘the immersive in-betweenness (‘mi-lieu’) of sounds, emphasising what produces sound, who hears the sound, and the emergence of a vibration that establishes a relationship between different agents’ (Lewis 2022, p. 40). The result of this combined approach highlights not only that the emergent relationship between physical vibrations of air molecules, human neurobiology, and representations of that sonic information, whether textual or illustrative, aided interactions with saints and their cults, but also that such materials were sometimes deliberately crafted to elicit such a response. Radomil Novák refers to this last point as ‘auditivization’, or the ‘process of encoding with the intention of creating an auditive text in the broad sense—using sounds as material or attempting to imitate or describe these sounds’ (Novák 2020, p. 154).5

In order to examine the ways in which sonic information was utilised in medieval hagiographical images, this article will focus on a single manuscript which pictorially depicts the life of the early medieval English Saint Guthlac in eighteen roundels: British Library, Harley MS Y.6.6 The Harley Roll, while drawing heavily from the first and most influential vita of the saint, Felix’s Vita sancti Guthlaci (c. 730–40), was likely composed within a decade or so of the second translation of Guthlac’s body in 1196.7 As Emma Nuding and others note, this places the creation of the Roll in the abbacy of Henrey de Longhamp (1191–1236) who, as will be discussed below, was responsible for a range of efforts to revitalise the cult of Saint Guthlac, primarily in terms of raising the status of Crowland as a centre for pilgrimage.8 Stylistically, the tinted images likewise attest to a Lincolnshire provenance, with Roberts highlighting Nigel Morgan’s argument that ‘the same artist was probably responsible for the drawings in the Cambridge Bestiary’ (Cambridge, University Library, MS Ii.4.26) (Roberts 2020, p. 262).9 The purpose and contemporary use of the Harley Roll remains a matter of debate, including its use as cartoons for stained glass windows in Crowland Abbey, which are no longer extant but for which there is plausible evidence (Roberts 2020, pp. 262–63); plans for wall paintings, enamel plaques, or wood carvings (Roberts 2020, p. 262, n. 41; Nuding 2022, pp. 120–23);10 or, as suggested by Nuding, as an interpretative aid for ‘shrine custodians’ (Nuding 2022, p. 123). All these potential uses for the Scroll, however, centre it in a Crowland context with direct relation to the period of Longchamp’s concentrated restoration of Guthlac’s cult in the late twelfth to early thirteenth centuries. The relational network of human, image, tradition, physical sonic vibration, and the ways these multimodal sound milieus centred on the Harley Roll, can be examined in two interrelated areas: first, in terms of auditory imagery being elicited unintentionally by general visual elements; second, in terms of the Roll’s deliberate sonifying of an episode from the life of Saint Guthlac.

2. Auditory Imagery: Predictive Processing and Sonified Environments

Auditory imagery is an expansive domain centring on the ‘complex process by which an individual generates and processes mental images in the absence of sound perception’ (Lima et al. 2015, p. 4639). This can include descriptions of sonic events in text and language, static images or representative paintings, as well as musical notation and onomatopoeia (Proverbio et al. 2011). In concert with developments in cognitive neuroscience and sub-fields like neuroaesthetics, auditory imagery provides a helpful tool by which to analyse the reception and experience of sonic elements in medieval English material cultural productions.11 First, research using the predictive processing model reveals that the viewing of static images strongly associated with sound production, such as an image of two hands clapping, is enough to activate the auditory cortex (Hsieh et al. 2012). Second, this activation is, in part, tied to the brain’s attempt to predict the likely sensory information that will follow, here the ‘clap’, and induces a form of auditory imagery, the clap resounding in a person’s mind. A static scene depicting events with clear and strong sonic associations can therefore be said to function, in part, by utilising auditory imagery as a means of interaction with the scene, a sound milieu in which the sonified images resonate in the mind of the viewer.

The Harley Roll, as mentioned above, was likely created as part of Lonchamp’s revitalisation of Guthlac’s cult and, as has been noted by numerous scholars, clearly seeks to contemporise important events of the saint’s life, particularly as they connect to the abbey at Crowland.12 A secondary effect of this updating is the production of visual material that sonifies late twelfth- to early thirteenth-century fenland life, and which allows for the creation of sound milieus that generate immersive auditory imagery in the relational space between viewer and depiction. In roundel 4, for example, the artist depicts Guthlac’s journey through the fenland streams, led by Tatwine, to the empty island of Crowland, where he would set up his eremitic retreat. The scene has its origins in Felix’s Vita S. Guthlaci (VSG):13

Quo audito, vir beatae recordationis Guthlac illum locum monstrari sibi a narrante efflagitabat. Ipse enim imperiis viri annuens, arrepta piscatoria scafula, per invia lustra inter atrae paludis margines Christo viatore ad praedictum locum usque pervenit; Crugland dicitur.

Felix’s text is rich with descriptive detail which, as I have argued previously, is a deliberate attempt to depict the physical environment in a realistic and vivid way, in order to render the reader an ‘eyewitness’ to the events in the fens (B. E. Brooks 2019, pp. 173–82). The primary descriptive information in the VSG is, however, environmental rather than focused on the structure of the boat, the motions of the individuals within it, and the manner in which the boat is propelled through the ‘invia lustra’ (‘trackless bogs’). Felix’s use of the nondescript Anglo-Latin noun scaphula (‘small boat’), modified by the adjective piscatorius (‘of or relating to fishing or fishers’), gives little imaginative detail; likewise, the common verb pervinere (‘to come through to, arrive at’) semantically portrays not much more than the successful end of a journey.15 The other textual iterations from which the Harly Roll’s illustrator could potentially have drawn echo Felix’s narrative, providing even less descriptive detail. The anonymous late ninth-century Old English Prose Guthlac (OPEG) mentions Tatwine and a boat, utilising the equally vague Old English noun scip (‘ship’), removing Felix’s adjectival addition, and depicting the journey with common Old English verbs of motion, gan (‘to go’), faran (‘to go, travel, or journey’), and cuman (‘to come’) (Kramer et al. 2020, p. 156). In both Orderic Vitallis’ early twelfth-century paraphrase and Peter of Blois’ prose from the late twelfth to early thirteenth century, Felix’s wording is maintained with no additional detail: ‘scafula […] piscatoria’ (‘fishing boat’), with equally general lexis of motion being employed, the verb veho ‘to bear, carry, convey, draw’) in Orderic, and the past participle ‘adductus’ from the verb adducere (‘to bring (a thing) to (a place or person)’) in Peter, respectively (Chibnall [1969] 1990, pp. 326–27; Horstmann 1901, p. 701).16 Even in Henry of Avranches’ later florid verse, there is only a slight variation with the noun cymba (‘boat’), the familiar adjectival designation ‘piscatoria’, and the slight shift in motion to Guthlac implying he will take himself to Crowland with the verb transferre (‘to carry across from one place to another’) (Townsend 2014, pp. 24–25).17(‘Guthlac, the man of blessed memory, on hearing this, earnestly besought his informant to show him the place. Tatwine accordingly assented to the commands of the man and, taking a fisherman’s skiff, made his way, travelling with Christ, through the trackless bogs within the confines of the dismal marsh till he came to the said spot; it is called Crowland’)(Colgrave 1956, pp. 88–89).14

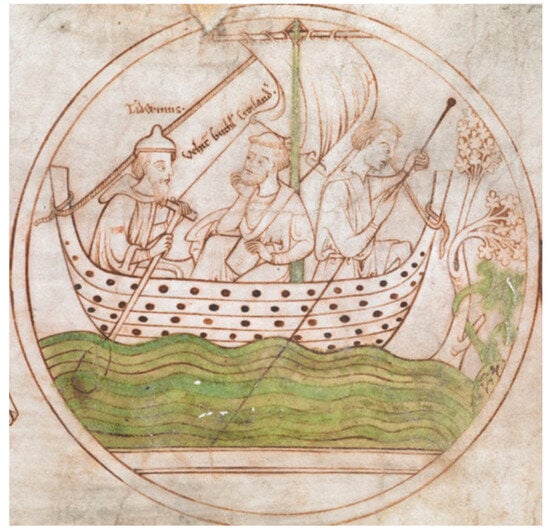

The Harley Roll illustrator expands on this textual tradition and centres it instead on the boat and its occupants as they make the journey, the details not only locating it chronologically, but also forming a sonically rich material aurality. As can be seen in Figure 1, the nondescript ‘scafula […] piscatoria’ has become a distinctive clinker-built boat of overlapping wooden planks with a mast and square sail set amidship.18 The nautical details appear consonant with archaeological evidence, mirroring, for example, many of the features of the slightly earlier tenth-century Graveney boat (McGrail 2001, pp. 218–20). While it is unlikely that a small fishing boat meant to navigate the winding, silted, and shifting waterways in the twelfth-century fens would have featured a mast and sail, as evidenced by the larger Graveney boat, it is not impossible. The titulus identifies the figure in the stern as Tatwine who, following Felix’s narrative, guides Guthlac to Crowland, here by steering the boat with a long oar or side rudder, another accurate contemporary detail, as many watercraft used this form of steering.19 Nuding, following Gillian Hutchinson, sees the scene as inflecting ‘its presentation of fenland pilgrimage with the texture of fens’ acquired from what she calls ‘contactual experience’, in the depiction of the character in the bow of the ship wielding the long pole as a kind of sounding rod to ‘check that the boat is keeping to the navigable part of the channel’, a necessity in the often silty fenland waterways (Nuding 2022, p. 124).20

Figure 1.

From the British Library Collection: Harley MS Y.6, Roundel 4.21

When considered within the framework of predictive processing and the sound milieu, the static image of Guthlac’s journey, rendered with contemporary details, would likely have given rise to activations in the auditory cortex and connected auditory imagery in the minds of viewers, as can be demonstrated by focusing on three specific portions of the image. First, the strikingly tinted water, vibrant and functioning as the pictorial foundation, is depicted in bold lines, curving, overlapping, which convey a sense of aqueous motion. The overarching soundscape of such a journey, water against wooden hull, lapping, slapping, would have been deeply familiar, as travel via streams and rivers by boat would have been widespread, with Della Hooke noting that ‘[r]ivers were the lifelines of early and high medieval England’ (Hooke [2007] 2014, p. 37).22 Second, in order to both steer and propel boats like the one in the Harley Roll, wooden implements like Tatwine’s oar and the unnamed figure’s setting pole would have been pushed in and out of the water countless times. Such actions create noticeable sonic occurrences, the steady poling of flat-bottomed boats through peat-black water, splash after splash, and the turning of oar against tide and small wave, all contextually familiar associations between actions and sound. Third, the square cloth sail that billows with wind, propelling the saint towards his ordained eremitic retreat, whipping, clacking, ropes humming. Again, the prevalence of such a sonic environment in late twelfth and early thirteenth century Crowland, given the widening of waterways, the coming and going of boats and ships along rivers, means the likelihood of association between the image and experience of its sound would have been high.23 Mark Gardiner, for example, highlights how ‘labour services owed’ to Crowland Abbey by tenants from the manors of ‘Oakington, Cottenham, and Dry Dayton’ were fulfilled by ‘moving goods by water’, and how corn and malt were still being delivered via river travel from Cottenham in the early fourteenth century (Gardiner [2007] 2014, pp. 89–90). The image, then, is ripe with aural potential, calling to mind a host of aqueous vibrations drawn from the watery soundscapes encountered by pilgrims on their journey to Crowland. The sound milieu created within the relational sonic space between Roll, viewer, and their mutual soundscape foundations, allows a rich and sensorially potent engagement with the power of Guthlac by those viewers, fenland damp dripping from their own riverine journeys.24

The contemporising of the Guthlac narrative, and its potential for eliciting auditory imagery, are likewise evident in the roundel 5. The subject of the image, narratively situated after roundel 4’s journey to the island, is Guthlac’s creation of his hermitage on Crowland. The episode as related in Felix’s VSG is fundamental to the depiction of the saint as an Antonian miles Christi, echoing the austere examples of the desert hermits, particularly in the location’s remoteness, wildness, and solitude:25

Erat itaque in praedicta insula tumulus agrestibus glaebis coacervatus, quem olim avari solitudinis frequentatores lucre ergo illic adquirendi defodientes scindebant, in cuius latere velut cisterna inesse videbatur; in qua vir beatae memoriae Guthlac desuper inposito tugurio habitare coepit.

The depiction, while deliberately echoing eremitic precedent, continues Felix’s emphasis on the vivid physicality of the Fens, including his lengthy description of the much-debated tumulus upon which the hermitage is set.26 The subsequent Guthlac textual corpus once again largely follows Felix, emphasising the tumulus and the saint’s small dwelling, though both Orderic and Guthlac B omit the scene.27 The OEPG employs geographical lexis from charters with the noun hlæw (‘barrow, burial mound’) while employing the nondescript noun hus (‘building, house’) for the structure; Peter uses the broader noun cumulus (‘heap, mound, or barrow’) and copies Felix’s tugurium (‘hut, shelter, small dwelling’); Henry, as Nuding highlights, includes place-based details, including the local materials from which Guthlac constructed his hut: ‘stature modice de limo construit et de/paruis uiminibus cannisque palustribus edem’ (‘he built a structure of moderate size from mud and small rushes and canes’) (Kramer et al. 2020, pp. 160–61; Horstmann 1901, p. 703; Townsend 2014, ll. 295–96; Nuding 2022, pp. 129–31).28 The rendering of the episode in Guthlac A is something of an outlier, not only in its divergent topography, wooded hills rather than sodden fens, but also in its overarching emphasis on Guthlac’s spiritual battle over the land.29 Scholarly debate on the lexical choices of the poet, with Guthlac as bytla (‘builder’) raising up the structure (‘arærde’), and its relationship to dating the poem continues, but the scene, whatever its spiritual implications, depicts Guthlac as lone builder.(‘Now there was in the said island a mound built of clods of earth which greedy comers to the waste had dug open, in the hope of finding treasure there; in the side of this there seemed to be a sort of cistern, and in this Guthlac the man of blessed memory began to dwell, after building a hut over it’).

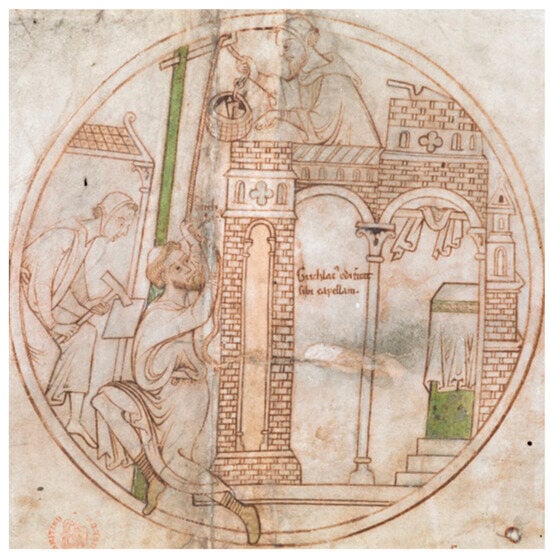

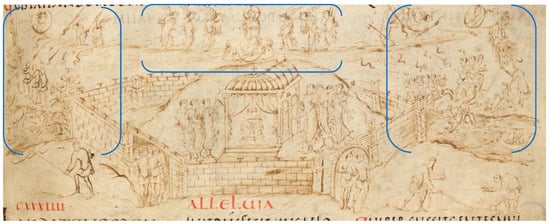

The Harley Roll, as numerous scholars have noted, presents a vastly different scene, where Guthlac’s construction of a solitary eremitic locus is transformed into a coenobitic exercise highlighting the saint’s role in Crowland Abbey’s founding (Roberts and Thacker 2020, pp. xxxviii–xxxix; Bacola 2020, p. 85; Kelly 1989, pp. 3–4; Black 2004, pp. 152–55). The roundel, as seen in Figure 2, includes the titulus ‘Guthlacus edificat sibi capellam’ (‘Guthlac builds himself a chapel’) and, as John R. Black notes, depicts ‘an elaborate Romanesque chapel featuring archways, windows, and an altar’, which Guthlac is building along with two labourers (Black 2004, p. 152). Late-twelfth- to early-thirteenth-century Norman features abound, from round-headed arches to elaborate stone brickwork, to Guthlac’s monastic habit.30 The emphasis, as discussed above, connects with the overarching aims of the Longchamp revival, particularly with the need to solidify Crowland’s claims to its contested lands.31 Yet this transformation and chronological updating also create a potent material aurality, functioning together with the viewer in creating a sound milieu of industrious monastic building works. On the left side, there is a young worker dressing a small slab, the mason’s hammer just in contact with the stone. The harsh ring of metal on rock, lithic crack followed by slivers falling to the ground, would have formed part of the common percussive aural experience of anyone living near or visiting a Norman Abbey like Crowland.32 Guthlac himself contributes sonically, the rubbing hum and creak of the winch he uses to lift stone bricks to the bearded labourer rising from the roof a likewise deeply known sonic component of such locations. It must be remembered that the site was, akin to many medieval religious centres, an environment characterised by building and rebuilding. This includes rebuilding after a disastrous fire in 1091, construction related to the translation of Guthlac into the newly rebuilt Romanesque church in 1136, repairs from another fire in 1147, and further construction for the translation of Guthlac into an opulent new shrine in 1196 (Roberts and Thacker 2020, pp. 346–47; Sharpe 2020, pp. 494–96; Alexander 2020, pp. 305–6). In such a context, the force of these familiar sonic connections, from hammer clang to rope swish, would likely have elicited auditory imagery for those viewing the Roll, their direct experience of equivalent soundscapes functioning together with the Roll’s imagery in the production of vibrant sound milieus. This resonant relationship would have directly allowed a more immersive interaction with the pictorial display of Crowland’s divinely sanctioned founding, supported by the ongoing aural environment of construction surrounding the 1196 translation of the saint.

Figure 2.

British Library, Harley MS Y.6, Roundel 5.

3. Sounding Silent Ink: Auditory Imagery and the Bestial Horde

The relational vibrations of the Harley Roll’s sound milieu include not only those discussed above, where the chronological updating of Guthlac’s life led to features likely to induce auditory imagery in viewers, but also, importantly, to a deliberate attempt in the Roll to sonify a specific moment in the textual tradition. As an eremitic miles Christi, Guthlac engages in spiritual warfare, and in one particular scene, demons in the guise of animals surround his cell and attempt to dissuade him from his saintly pursuit by way of sonic attack. The episode is an adaptation of Ch. IX in the Vita Antonii and, as I have previously argued, functions by Felix transplanting it into the Fens, removing non-native species from the list (lion, leopard, scorpion, asp), while adding the familiar horse, stag, boar, and raven, in order to ‘demonstrate Guthlac’s stabilitas in the face of this sonic attack created from the biophonic environment of eighth-century Anglian life’ (B. E. Brooks 2021, p. 164). Felix’s auditivisation here functions by creating a literary soundscape, a cacophony of animal sounds recognisable from contemporary everyday life:

The Guthlac corpus, in general, retains the aural focus, the OEPG emphasising the antagonistic harshness of the sounds with the noun grymettung (‘roaring, bellowing’) while echoing even the onomatopoeic terminology of Felix (Latin ‘corvus crocitum’ with Old English ‘hræfne cræcetunge’) (Kramer et al. 2020, p. 176); Peter removing much of the visual aspects, thereby emphasising the sonic, though he also omits all avians from the list; Henry overstuffing the episode with classical allusions to Cerberus, Lycaon, and Midas, as well as adding further animals including an owl and toad (‘bubo tremit’ and ‘bufo pipat’, respectively); and the poem Guthlac B eliding the specific sonic productions into indefinite bestial cries: ‘Hwilum wedende swa wilde deor/cirmdon on corðre’ (‘Sometimes raving like wild animals/they shrieked, cried out together’) (Bjork 2013, ll. 907–8a).34

| Nam leo rugiens dentibus sanguineis morsus rabidos inminebat; taurus vero mugitans, unguibus terram defodiens, cornu cruentum solo defigebat; ursus denique infrendens, validis ictibus brachia commutans, verbera promittebat; coluber quoque, squamea colla porrigens, indicia atri veneni monstrabat, et ut brevi sermone concludam, aper grunitum, lupus ululatum, equus hinnitum, cervus axatum, serpens sibilum, bos balatum, corvus crocitum ad turbandum veri Dei verum militem horrisonis vocibus stridebant.33 | (‘Thus a roaring lion fiercely threatened to tear him with its bloody teeth: then a bellowing bull dug up the earth with its hoofs and drove its gory horn into the ground; then a bear, gnashing its teeth and striking violently with either paw alternately, threatened him with blows: a serpent too, rearing its scaly neck, disclosed the threat of its black poison: to conclude briefly—the boar with its grunting, the wolf with its howling, the horse with its whinnying, the stag with its belling, the serpent with its hissing, the ox with its lowing, the raven with its croaking, made harsh and horrible noises to trouble the true soldier of the true God’) (Colgrave 1956, pp. 114–15). |

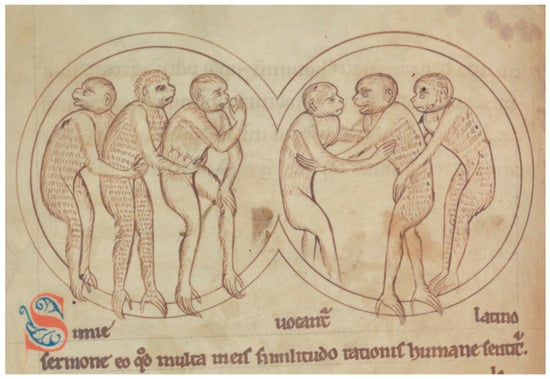

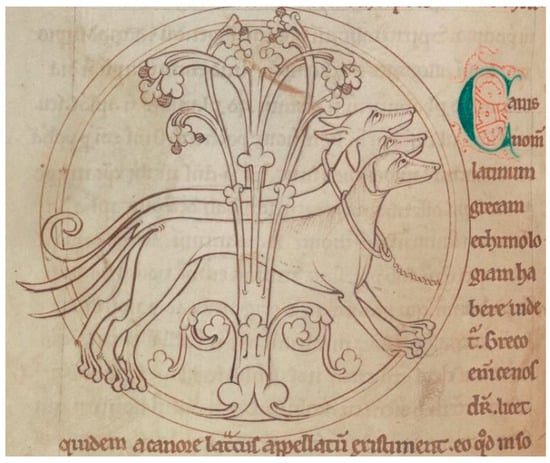

In roundel 9 of the Harley Roll, this central emphasis on the sonic nature of the attack is being rendered visually, relying partly on the auditivity of its audience to increase its immersive effect. As can be seen in Figure 3, Guthlac stands centrally within the Romanesque Norman chapel, surrounded by six demons, each with the head of an animal.35 Given the specificity of the faunal list, the Roll’s choice of animal depiction requires consideration. Roberts has suggested that the figures on the left are, from top to bottom, an ape, hound, and donkey (Roberts 2020, p. 253). Comparison with the Cambridge Bestiary, which, as mentioned earlier, the Roll artist arguably was involved with, helps to clarify some ambiguity, as well as gesture towards reasons for choices that depart from the wider Guthlac tradition. The furthest departure, in that I can find no connected hagiographical precedent, is the grinning ape-like creature on the top left of the roundel. As can be seen in Figure 4, the Cambridge Bestiary’s depiction of apes on f. 10v is strikingly similar to the Roll’s, particularly with the ape in the centre of the right-side circle.

Figure 3.

British Library, Harley MS Y.6, Roundel 9.

Figure 4.

Cambridge, University Library, MS Ii.4.26, f. 10v.36

The choice of an ape to form part of the bestial horde is, at first, discordant. Not only does it not appear in any other material related to Guthlac, but also the choice strays from Felix’s localising of the saint’s narrative in the fenland landscape. A potential reason can be found in the wider philosophical and theological traditions regarding animals and their meanings in texts like the Cambridge Bestiary.37 The accompanying textual description interprets the animal’s visual unpleasantness as a figure for the devil, who began as an angel in heaven but was internally a ‘hypocrite and deceiver’ (‘Diabolus inimicum habuit cum esset in celis angelus. Sed hypocrita et dolosus fuit intrinsecus’).38 The allegorical valencies of the ape lend themselves well to the Guthlac narrative, as the purpose of the demonic attacks is always to dissuade him from his holy pursuit and turn to sin.39

The demon just beneath the ape, identified as a hound by Roberts, is likewise a departure from Guthlacian tradition. Other than Henry’s reference to Cerberus (‘Latrare/Cerberon audires’, ‘You/might hear Cerberus bark’), the only canine representatives are wolves (Townsend 2014, ll. 761–62). Comparison with the Cambridge Bestiary, Figure 5, does indeed reveal a correspondence, particularly in terms of the snout, eye and head shape of f. 18v, though the ears of the creature in the Roll are noticeably thinner and longer.

Figure 5.

Cambridge, University Library, MS Ii.4.26, f. 18v.

- There is, arguably, an equal correspondence with the wolf on f. 17r (Figure 6), with similar snout, eye, head shape, and a similar thicker eyebrow-like line (though the forms are not identical).

Figure 6. Cambridge, University Library, MS Ii.4.26, f. 17v.

Figure 6. Cambridge, University Library, MS Ii.4.26, f. 17v. - Given the prevalence of the wolf in every text that includes the bestial horde scene, apart from Guthlac B, it is possible that a wolf might be intended here.40 The animal on the bottom left of Figure 3 is clearer, a donkey or wild ass, which is referenced only in the later texts, with Peter’s ‘asinus rudens’ (‘ass braying’) and Henry’s reference to Midas, ‘rudere Mydam’ (‘Midas brays’) (Townsend 2014, l. 763; Horstmann 1901, p. 708). This departure could also be connected to the allegorical traditions evidenced in the Cambridge Bestiary, as the onager or wild ass on f. 25r is said to symbolise the devil sonically, braying about night and day seeking his prey.41

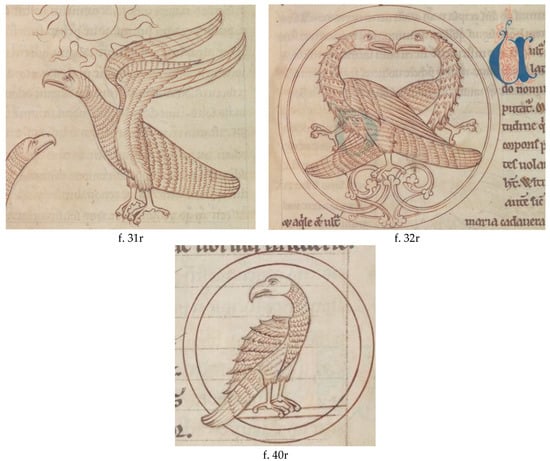

The demonic beast on the top right shares features with numerous avians in the Bestiary, as can be seen in Figure 7 below, including the eagles on f. 31r, particularly in terms of their large nostril holes; the vultures on f. 32r; and the hawk on f. 40r, particularly in terms of its curved beak.42

Figure 7.

Cambridge, University Library, MS Ii.4.26, ff. 31r, 32r, and 40r.

- Guthlac textual tradition only mentions a crow or raven, and though the Cambridge Bestiary has lost several folios, one of which likely included an image of these birds, connected bestiary manuscripts reveal little similarity between the Roll and depictions of those birds. In keeping with the animals on the left of the Roundel, it is possible a hawk was intended here, as the animal allegorically represents the devil as tempter of worldly riches (Beal 2025, pp. 173–74). The head in the middle of the right side of Figure 3 is the most enigmatic, corresponding to no animal I can find in the secondary family Bestiary tradition, with Roberts’ cat unlikely for both allegorical and visual reasons.43 The final bestial demon, about to be whipped by Guthlac, is either a bull or ox, both of which are mentioned in the texts.44

Roundel 9’s refashioning of the bestial horde scene, from eremitic wilderness to Romanesque Abbey, from eighth-century fenland animals to a combination of experiential and allegorical figures, includes a further, important feature. Each demonic beast, excepting the grinning ape, is depicted with mouths, snouts, and beaks wide open, accusing fingers gesturing towards Guthlac to indicate the direction and focus of their sonic actions. Echoing the textual tradition, none of the demons are presented physically assaulting Guthlac, but instead breach the walls with their acoustic clamour.45 The Roll artist is here sonifying the scene in two ways. First, by way of predictive processing, eliciting auditory images from the easily recognisable animal forms. A viewer coming upon the Roll would likely have been deeply familiar with the bellows of an ox or bull, the braying of an ass, the howls of wolves or calls of hounds, and the sharp cries of eagles and hawks, and where exact aural connection was impossible, the overarching sonic categories would have come into play: bird, canine. Second, the non-native and unfamiliar ape, as well as the difficult-to-identify figure, aid in the uncanny nature of the sonic attack, with the ape’s grin echoing the grins of the demons in roundel 7, reminding viewers these are not animals, but demons dressed as them.46 The material aurality of the image, therefore, creates a sonic milieu in which the acoustic attack upon the saint can be heard internally by pilgrims and others visiting Crowland, the place reverberating with the bustling contemporary soundscape of Guthlac’s victory: Abbot Lonchamp’s thriving and demon-free Benedictine Abbey of Crowland.

4. Material Auralities: Image and Song

The multimodal encounter with St Guthlac via the Harley Roll can be extended further when considered with another type of sonic creation in its monastic Crowland milieu. During roughly the same period as the composition of the Harley Roll, somewhere near the end of the twelfth and beginning of the thirteenth centuries, as Henry Parkes has highlighted, ‘the Crowland monks turned their creative energies towards the Mass’ and created a number of sung sequences for St Guthlac, which were ‘large musical canvases for original creative expression, customarily sung between the Alleluia and Gospel on principal feasts’ (Parkes 2020, p. 292). One such sequence is British Library, Egerton MS 3759, a thirteenth-century Gradual from Crowland titled ‘Regi regum laus’. Parkes identifies this as typical of twelfth and thirteenth century sequence composition and argues that it is ‘likely a product of the events of 1196’, the second translation of the saint (Parkes 2020, p. 293). There is an earlier sequence from the same manuscript, ‘Exultet cum angelis’ (likely a product of Guthlac’s own community from the eleventh century), which follows Felix’s VSG closely in the order of events it describes. ‘Regi regum laus’, on the other hand, departs from the VSG in order as well as form, adding, for example, a mention of two angels to whom Guthlac entrusts everything (Parkes 2020, p. 293).47 Given the likelihood of both the Roll and Sequence being produced on or near the 1196 translation of the saint, I would like to argue that they are more connected than Parkes suggests, particularly in terms of the important sonic attack depicted in roundel 9 (Figure 3). In Versicle 5 (a and b), there appears to be a reference to the bestial horde scene, as its lexical pieces echo closely the depiction in Felix’s VSG:

Egerton: 5a. Iam insurgunt tempramenta/et diuersa in tormenta/hinc propellit zabulus. b. Set contempsit blandimenta/penas spernens et figmenta/hostis dei famulus.

(‘Now people rise up against his moderation and in hostile torments the devil drives him away. /But he has despised the enticements, scorning the enemy’s punishments and inventions, a servant of God’)(Parkes 2020, p. 297).48

VSG: ‘Sanctus itaque Christi famulus, armato corde signo salutari, haec omnia fantasmatum genera despiciens, his vocibus usus aiebat’.

The description of the end of the bestial horde scene, when Guthlac has successfully warded off the demon-animal’s attack, is mirrored here in Versicle 5, where ‘dei famulus’ echoes the VSG’s ‘Christi famulus’, and ‘penas spernens et figmenta hostis’ echoes the VSG’s ‘omnia fantasmatum genera despiciens’. While the terms are not identical, they are synonymous in general meaning. The centrality of the bestial horde scene, with its inclusion in all but Orderic Vitalis’ summary of Felix’s text, is being reflected here in the sequence. The potential for a unified multimodal engagement with the saint’s narrative, in which vibrations of meaning and sound abound, relying on both the power of predictive processing and deliberate auditivisation, through both the Roll and sequence is tantalising.(‘And so the holy servant of Christ, arming his breast with the sign of salvation and despising all phantoms of this sort, uttered these words’)(Colgrave 1956, pp. 114–15).

5. Material Auralities: Beyond Hagiography

The methodology employed in this article, while relying in great part on the unique connection between a singular saint and specific locations in the fens, has the potential for non-hagiographic contexts as well. Material aurality, based as it is upon predictive processing and the interaction between forces that create sound milieus, can equally be applied to other instances of both unintentional and intentional sonification. One potential example is the famous Harley Psalter (British Library, Harley MS. 603), likely created in the first half of the eleventh century.49 The de lux manuscript is an adapted copy of the early ninth-century Utrecht Psalter, and was the product of the scriptorium at Christ Church Canterbury, involving at least twelve hands working over a number of years, though the majority of the work was completed within a decade or so of its beginning (Noel 1995, pp. 1–6, 136–40, and 185). While the illustrations of the Harley Psalter are generally copied faithfully, certain sections, as William Noel and others have noted, deviate widely, often in ways reflecting the contemporary world of eleventh-century south-eastern England (Noel 1995, pp. 80–81). Space does not allow a full examination, but in quires ten through eleven, illustrated by artist F, there appear to be deliberate adaptations of the Utrecht Psalter that sonify elements drawn from contemporary eleventh-century life.50

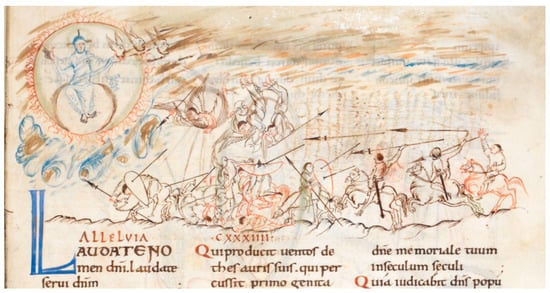

These transformations can helpfully be seen by comparing the illustrations for Psalm 134 (135) in the Utrecht and Harley Psalters. As can be seen in Figure 8 and Figure 9, the Harley Psalter’s illustrations bear only passing resemblance to their exemplar, with artist F taking the surrounding vignettes in Utrecht (highlighted with blue brackets), which illustrate verses seven and eight, and expanding them to be the illustration for the entire psalm, with a clear focus on verses seven and ten.51 Further still, these changes include a sonic focus not present in the Utrecht Psalter, which can be seen in two specific areas: God and his storm, and the battle scene beneath him. Unlike Utrecht, God is presented in the Harley Psalter directly casting the storm from his left hand, which roils beneath him as blue and brown clouds extending out over the battlefield, bringing wind (brown), lightning (yellow), and rain (blue/brown). This chaotic presentation, in which the swirling blue clouds beneath the mandala crash into one another, and the whirling mess of colour stretches across the page, renders the divine storm visually and aurally. The sonic connection between a lightning bolt and its accompanying thunder would likely have elicited auditory imagery for an audience familiar with such storms in quotidian life.52 The power of God in storm now resonates in the mind.

Figure 8.

Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS Bibl. Rhenotraiectinae I Nr 32, f. 76r.53

Figure 9.

From the British Library Collection: Harley MS. 603, f. 69r.54

In the bottom half of the scene in the Harley Psalter, the artist has taken the hints of battle imagery in Utrecht, with its few horses running with closed mouths, and developed it into an extraordinary conflict in which riders hurl spears at one another, spears stick in shields, horses gallop, fall, and even trample a fallen rider. The battle, like any battle, is a noisy one, but rendered here by artist F with an attempt at literal physicality, which by its nature sonifies the presentation. Akin to the bestial horde scene in the Roll, the horses here have mouths agape, blowing and snorting in their furious charge. More aurally striking is the central section, where one horse has been speared and is caught in the act of falling, its lower jaw just crashing into the ground with its eyes closed, mouth wide open, a spear embedded in its belly. Likewise, the horse immediately left of it, who has just been speared and is turning towards the wound, crying out. While it is difficult to argue that those working in the scriptorium creating and reading the Harley Psalter had been in battles on horseback, the sounds associated with the actions depicted are familiar ones: a horse crying out in pain; the sound of metal piercing wood; the moans of wounded people.55 The sound milieu created here, embedded sonic information within the image eliciting auditory imagery in the viewer, the viewer aiding the construction from experience of lived soundscapes, functions together in the sounding of a potent material aurality.

6. Conclusions

The multisensory environment of medieval saint’s pilgrimage locations, especially high-status institutions like Crowland during the time of the Longchampe revival, provided rich avenues for the faithful to seek contact with the respective saints, and via their intercession, with the power of God. One of the primary areas of sensory engagement was sound, from prayer to homily, sung sequence to hagiographical retelling on feast days. Within this context, static visual representations of sonic events would have aided in the immersive experience of the viewer, as demonstrated in the rich material aurality of the Harley Roll. The sound milieu created between viewer and Roll stems from both unintentional sonification, where pictorial representations elicit auditory imagery from depictions of the contemporary world, and intentional sonification, in which sonic information is deliberately being encoded (auditivisation) with the expectation of the audience recognising it (however unconsciously) in order to further connection with the subject(s) of the image (auditivity). While both the purpose and viewing location(s) of the Harley Roll remain open for debate, its creation and use set it within a Crowland milieu, the physical landscape and monastic structures layered with narratives from Guthlac’s various vitae, all functioning together to provide rich ground for the creation of auditory imagery. From the splash of water on clinker-built ship on roundel 4, to the deliberately sonified bestial horde attacking St Guthlac in roundel 9, the Harley Roll resonates with material aurality.

The critical potential of engaging with sonic information through material aurality extends well beyond hagiography. As demonstrated by the aurally vivid Harley Psalter, pictorial representation in medieval material culture could be encountered multimodally, with sound milieus created from the sonic information in the illustrations allowing a richer and more immersive interaction with subjects ranging from St Guthlac fighting bestial demons to God thundering down upon His enemies. The resonant and reflexive relationship between image, viewer, and external vibratory soundscape, which comes together in creating a sound milieu, will allow novel insight into the ways in which literary representations of sounds manifest in material culture.

Funding

This work was supported by The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science: Grant Number KAKENHI (19K13100).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For discussions on the prominent role of sound and hearing in medieval religious experience, see (Keller 2014, pp. 195–216, esp. p. 200). I would like to thank the following for their invaluable help in the research and development of this article: Francis Leneghan, Mike Bintley, and Helen Appleton. |

| 2 | See, for example, (B. E. Brooks 2021, 2022; F. Brooks 2016; Butler 2019; Shores 2021). |

| 3 | There is some overlap between my combined methodology and (Foys 2014, pp. 459–62), particularly in his critique of ocularcentrism and reflections on the ‘linguistic noise of Beowulf’ and, citing Richard Brilliant, the graphic noise of the Bayeux Tapestry (p. 462). |

| 4 | For an overview of these ideas see (Lauwereyns 2018; Chow et al. 2014; Ogi et al. 2019; Tiihonen et al. 2024). |

| 5 | It should be noted that this is connected to his wider notion of ‘Auditivity’ in which ‘auditive competence—a person’s basic ability to hear sounds’ is combined with their ‘auditive literacy—i.e., the ability, based on a person’s experience of listening to various sounds, to decode their meanings in a specific socio-cultural context or to refer to such sounds’ (p. 155). |

| 6 | Guthlac’s tradition lends itself to such study as the extant Guthalc material covers a wide chronological range, several genres, and several forms, with the saint appearing in prose and poetic vitae (in Old English, Anglo-Latin, and Middle English), in manuscript images, as well as in stone sculpture. While the Roll as extant is largely intact, it should be noted that there are likely two or three missing drawings in the beginning of the sequence as the manuscript has been cut. See (Roberts 2020, p. 243). The manuscript will hereafter be referred to as the ‘Harley Roll’. |

| 7 | See, for example, (Roberts 2020, p. 262), who notes that the translation ‘provides a plausible terminus post quem for the Harley Roll; the script used in titles and labels is best described as protogothic, supporting a date not much beyond c.1200’. See also (Bacola 2012, p. 145; Nuding 2022, p. 120), who likewise place the creation of the role in the late twelfth century. |

| 8 | See (Nuding 2022, p. 119; Bacola 2012, pp. 144–45). |

| 9 | The text will hereafter be referred to as the ‘Cambridge Bestiary’. |

| 10 | See (Roberts 2020, p. 262, n. 41) for the wood carvings, and (Nuding 2022, pp. 120–23) for wall paintings and enamel decorations. |

| 11 | The application of such approaches to the medieval period are confronted with the inherent difficulty of chronological and contextual difference, arising as they do from our contemporary moment and its cultural, historical, linguistic, and philosophical milieu. Scholars have long interrogated the ways in which medieval experience, emotional, intellectual, physical, spiritual, are encoded in text and image, from Vincent Gillespie’s exploration of the sensorium (Gillespie 2014), to Barbara Rosenwein’s argument for situating emotional experience in what she calls ‘emotional communities’ (Rosenwein 2015, p. 3), to Mary Carruthers wok on memory (Carruthers 2008, 2013), to recent embodied participatory approaches as seen in Lauren Mancia’s Cambridge Element, Embodied Epistemology as Rigorous Historical Method (Mancia 2025). All this complexity notwithstanding, there is little evidence that the fundamental structure of the human brain, however embedded within and developed from its historical and cultural milieu, has changed dramatically enough in the intervening centuries for the approaches used in this article to be invalid. |

| 12 | See (Bacola 2012, pp. 47–54), who describes the period as the ‘Longchampe Revival’, and how after being installed as abbot of Crowland in 1191, ‘his forty-six year abbacy marked an even more prolific stage in Crowland’s development in which new texts were commissioned, visual representations and architectural settings constructed and new relics promoted’ (p. 47), and (Roberts and Thacker 2020, p. xxxvii). |

| 13 | Of the possible textual influences for the image, the following do not include the scene: the Old English poems Guthlac A and Guthlac B. |

| 14 | All references to and translations of the VSG from (Colgrave 1956). |

| 15 | Felix does not seem to employ the verb with any special significance here or elsewhere in the VSG. Pervenio appears twelve times, and with the exception of a single use describing Easter Day arriving (‘dies Paschae pervenit’, p. 154), refers to people mundanely coming to a location, including Guthlac to Repton (‘monasterium Hrypadun usque pervenit’, p. 66), and Æthelbald returning to see Guthlac’s corpse after he died (‘ad corpus ipsius pervenit’, p. 164). All definitions for Latin come from (Ashdowne et al. 2018) unless otherwise indicated. |

| 16 | For the dating of the texts, see (Chibnall [1969] 1990, p. 46; Roberts 2020, p. 267). |

| 17 | Roberts convincingly argues that it is unlikely the Roll artist would have used Henry’s text, particularly given the dating of the Roll to within a decade of 1196. See (Roberts 2020, p. 267). |

| 18 | For an authoritative discussion of clinker-built boat construction, see (McGrail 2001, pp. 207–17). |

| 19 | It should be noted that the episode’s importance to the post-conquest Guthlac cult was such that a version of it likely appears in the bottom of the famous tympanum sculptures over the west doorway of the extant abbey church. Though elemental erosion has made precise comparison difficult, most scholars agree these are related. See, for example, (Roberts 2020, p. 265; Bacola 2012, p. 52). |

| 20 | See also (Hutchinson 1994, p. 188). |

| 21 | All images of the Harley Roll are reproduced by kind permission of the British Library. |

| 22 | See also (Carver 2014). |

| 23 | See, for example, (Chisholm 2010). |

| 24 | It should be noted that the Harley Roll artist is working within established conventions, particularly concerning the depiction of moving water through a green tinted wash. A similar style, for example, can be seen in several slightly later manuscripts of Matthew Paris, including Royal MS 14 C VII, ff. 134v and 116v, as well as Corpus Christi College Cambridge MS II, f. 50v, though these all depict journeys at sea. Similarities can also be found in the Aberdeen Bestiary, particularly f. 1v showing the creation of the waters and firmament. The Harley Roll’s use is, however, distinct in its specific connection to the surrounding landscape, its riverine focus, its narrative and hagiographical importance to the Guthlac cult, and its reception context which often involved river journeys in order for the Roll itself to be viewed. |

| 25 | See (B. E. Brooks 2019, p. 180), where I highlight Felix’s use of both the Evagrian Vita Antonii and St Jerome’s Vita Pauli. |

| 26 | Scholarship on Guthlac’s chosen mound is extensive, often analysing it via several texts together. See, for example, (Noetzel 2014; Clarke 2006; Wright and Willmott 2024; Estes 2017, pp. 98–107; Semple 2002, pp. 252–53; Hooke 1998, p. 99). |

| 27 | Orderic does later in Book 14 describe Guthlac returning to his ‘chosen hermitage’ (‘electam heremum’), while Guthlac B references the eremitic cell with the curious plural form of the noun wic in l. 894a (‘a dwelling, settlement, or a collection of houses’) (Chibnall [1969] 1990, pp. 326–27). |

| 28 | Text and translation for Henry’s text from Townsend’s edition (Townsend 2014). |

| 29 | See (B. E. Brooks 2019, pp. 260–85; Clarke 2012, pp. 46–47; and Frenze 2018). |

| 30 | For an overview of Crowland Abbey and its architectural development, see (Alexander 2020). |

| 31 | See, for example, (Nuding 2022, pp. 63–64) with relation to Guthlac A and land disputes, and pp. 132–41 with relation to ongoing land disputes in the thirteenth-century as seen in Henry’s verse Life of Guthlac. |

| 32 | While it is difficult to ascertain the specific intensity of such an event without extensive archaeoacoustic research, modern studies can be used as reasonable analogues to get a sense of the level of sound produced. For example, a report by the University of Washington found that masonry restoration workers dressing stone with hand tools like hammers experience sound in the 87–105 dB (A) range (the study did not distinguish between hammers, mallets, and sledges), above the level (85 dB) at which hearing protection is required. See https://depts.washington.edu/occnoise/content/masonryrestorationIDweb.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025). |

| 33 | Italics added for emphasis and comparison. |

| 34 | Guthlac B, ll. 907–8a. Orderic and Guthlac A omit this episode. All references to Guthlac B from (Bjork 2013). |

| 35 | The number of bestial demons alters from text to text. Roberts notes that the ‘roll’s six beasts, as opposed to the ten named by Felix, come closer to the revolving tally of seven deadly sins so often symbolized by animals’ (Roberts 2020, p. 253). |

| 36 | All images of Cambridge, University Library, MS Ii.4.26 are reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library. |

| 37 | For an overview see (Clark 2006; Cavell 2022). |

| 38 | All quotations taken from the digital manuscript, which I have normalised here. See also (Beal 2025, p. 172), who discusses the equivalent text in the Aberdeen Bestiary. |

| 39 | See (B. E. Brooks 2021, p. 165). |

| 40 | There is also considerable allegorical potential with the wolf, as the Bestiary tradition attests. See (Beal 2025, pp. 166–68). |

| 41 | The animal depicted in f. 25r is a close resemblance to the Roll, though it must be said that the eyebrow in the Roll is closer in form to the curly eyebrow of the assinus on the top of the folio rather than the onager on the bottom. |

| 42 | While Roberts sees this as an eagle, the host of positive allegorical interpretations of eagles makes this somewhat unlikely. |

| 43 | See Cambridge Bestiary, f. 28r. The most closely related manuscripts consulted for this article are the following: Aberdeen, University Library, MS 24; Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Ashmole 1511; London, British Library, MS Add. 11283; and the Worksop Bestiary, New York, Morgan Library and Museum, MS M.81. |

| 44 | Felix specifies it as an ox, ‘bos balatum’, while the OPEG, Peter, and Henry, all specify it as a bull (fearr and taurus respectively). |

| 45 | Compare with roundel 7 in which the demons bodily carry St Guthlac into the air. |

| 46 | See Harley Roll, f.8r. |

| 47 | Parker further notes that in both the sequence and the image in roundel 6, they ‘choose to mention angels much earlier in the narrative of Guthlac’s life—specifically, after the building of a church and before the appearance of the devil—and the fact that this conjunction occurs in two creations from Crowland, possibly both from the twelfth century, may be evidence of their interaction’ (293). |

| 48 | Text and translation from (Parkes 2020, p. 297). |

| 49 | It should be noted that some sections were likely created later. |

| 50 | For example, see (Noel 1995, p. 81), who highlights how a harp on f. 70r by Artist F is ‘very different in form to the ones in Utrecht’, and was likely drawn from ‘artist F’s own experience with harps’. It should be noted that the text for the psalms, while modelled on the Utrecht Psalter, comes from the Romanum version rather than Utrecht’s Gallican version, and also that the scribe for quires ten and eleven of the Harley Psalter (Scribe 1), did not follow the exemplar in the physical placing of the psalm text. Further still, Scribe 1 completed his text before artist F drew the illustrations. This situation allows Noel to argue that the ‘the mould of the illustrations was determined by the script, and it differed radically from Utrecht that recreation of its compositions was frequently impossible’, and therefore artist F’s illustrations consequently stem partly from this situation (pp. 76–77). |

| 51 | Psalm 134: 7: ‘Educens nubes ab extremo terrae, fulgura in pluviam fecit; qui producit ventos de thesauris suis’ (‘He brings up clouds from the end of the earth: he has made lightnings for the rain. He brings forth winds out of his stores’); 10: ‘Qui percussit gentes multas, et occidit reges fortes’ (‘He smote many nations, and slew mighty kings’). Latin biblical quotations from (Weber and Gryson 2007), and all translations are my own. |

| 52 | It should also be noted, given the monastic context of the manuscript, that the notion of clouds crashing together to make thunder was part of established descriptions of the workings of God’s world. See Bede, De natura rerum, XXXVIII (Jones et al. 2003, p. 221). |

| 53 | All images for the Utrecht Psalter from Utrecht University’s online special collections: https://psalter.library.uu.nl/page/159 (accessed on 15 May 2025). |

| 54 | All images of the Harley Psalter are reproduced by kind permission of the British Library. |

| 55 | It should also be noted that the early eleventh century, during which the principal work of the Harley Psalter was accomplished, saw the Danish raids on Canterbury, during which Archbishop Ælfheah was taken hostage and eventually killed in 1012. |

References

- Alexander, Jennifer S. 2020. Crowland Abbey Church and St Guthlac. In Guthlac: Crowland’s Saint. Edited by Jane Roberts and Alan Thacker. Donington: Shaun Tyas, pp. 298–315. [Google Scholar]

- Ashdowne, Richard, David Howlett, and Ronald Latham, eds. 2018. Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bacola, Meredith Anne. 2012. Dissemination of a Legend: The Texts and Contexts of the Cult of St Guthlac. Ph.D. thesis, Durham University, Durham, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Bacola, Meredith Anne. 2020. Vacuas in auras recessit? Reconsidering the Relevance of Embedded Heroic Material in the Guthlac Narrative. In Guthlac: Crowland’s Saint. Edited by Jane Roberts and Alan Thacker. Donington: Shaun Tyas, pp. 72–85. [Google Scholar]

- Beal, Jane. 2025. The Devil’s Threat in Medieval Bestiaries: Recognizing and Resisting Evil in the Dragon, Serpent, Wolf, Fox, Ape, Whale, Hawk, Partridge, and Raven. Ítaca. Revista de Filologia 16: 149–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjork, Robert E., ed. and trans. 2013. The Old English Poems of Cynewulf. Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Black, John R. 2004. Tradition and Transformation in Text and Image in the Cults of Mary of Egypt, Cuthbert, and Guthlac: Changing Conceptualizations of Sainthood in Medieval England. Ph.D. thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, Britton Elliott. 2019. Restoring Creation: The Natural World in the Anglo-Saxon Saints’ Lives of Cuthbert and Guthlac. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, Britton Elliott. 2021. Biophonic Soundscapes in the Vitae of St Guthlac. English Studies 102: 155–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Britton Elliott. 2022. The Sound-World of Early Medieval England: A Case Study of the Exeter Book Storm Riddle. In Ideas of the World in Early Medieval English Literature. Edited by Mark Atherton, Kazutomo Karasawa and Francis Leneghan. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 203–22. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, Francesca. 2016. Sight, Sound, and the Perception of the Anglo-Saxon Liturgy in the Exeter Book Riddles 48 and 59. In Sensory Perception in the Medieval West: Manuscripts, Texts, and Other Material Matters. Edited by Simon Thomas and Michael Bintley. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 141–58. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Shane. 2019. Principles of Sound Reading. In Sound and the Ancient Senses. Edited by Shane Butler and Sarah Nooter. London: Routledge, pp. 233–55. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, Mary. 2008. The Book of Memory: A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, Mary. 2013. The Experience of Beauty in the Middle Ages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, Martin. 2014. Travels on the Sea and in the Mind. In The Maritime World of the Anglo-Saxons. Edited by Stacey S. Klein, William V. Schipper and Shannon Lewis-Simpson. Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Cavell, Megan, ed. 2022. The Medieval Bestiary in English: Texts and Translation of the Old and Middle English Physiologus. Peterborough: Broadview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chibnall, Marjorie, ed. and trans. 1990. Orderic Vitalis. Historia ecclesiastica. In The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis. Oxford: Clarendon Press, vol. 2. First published 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, Michael. 2010. The Medieval Network of Navigable Fenland Waterways I: Crowland. Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society 99: 125–38. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, Ho Ming, Raymond A. Mar, Yisheng Xu, Siyuan Liu, Suraji Wagage, and Allen R. Braun. 2014. Embodied Comprehension of Stories: Interactions between Language Regions and Modality-Specific Neural Systems. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 26: 279–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, Willene B. 2006. A Medieval Book of Beasts: The Second-Family Bestiary: Commentary, Art, Text and Translation. Woodbridge: Boydell. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Catherine A. M. 2006. Literary Landscapes and the Idea of England, 700–1400. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Catherine A. M. 2012. Writing Power in Anglo-Saxon England: Texts, Hierarchies, Economies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colgrave, Bertram, ed. and trans. 1956. Felix’s Life of Saint Guthlac: Texts, Translation and Notes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Estes, Heidi. 2017. Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes: Ecotheory and the Environmental Imagination. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foys, Martin K. 2014. A Sensual Philology for Anglo-Saxon England. Postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies 5: 456–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenze, Maj-Britt. 2018. Holy Heights in the Anglo-Saxon Imagination: Guthlac’s Beorg and Sacred Death. The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 117: 315–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, Mark. 2014. Hythes, Small Ports, and Other Landing Places in Later Medieval England. In Waterways and Canal-Building in Medieval England. Edited by John Blair. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 86–109. First published 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, Vincent. 2014. The Senses in Literature: The Textures of Perception. In A Cultural History of the Senses in the Middle Ages, 500–1450. Edited by Richard G. Newhauser. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 153–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hooke, Della. 1998. The Landscape of Anglo-Saxon England. London: Leicester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hooke, Della. 2014. Uses of Waterways in Anglo-Saxon England. In Waterways and Canal-Building in Medieval England. Edited by John Blair. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 37–54. First published 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Horstmann, Carl, ed. 1901. Peter of Blois. Vita Sancti Guthlaci. In Nova Legenda Anglie: As Collected by John of Tynemouth, John Capgrave, and Others, and First Printed, with New Lives, by Wynkyn de Worde. Oxford: Clarendon Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Po-Jang, Jaron T. Colas, and Nancy Kanwisher. 2012. Spatial Pattern of BOLD fMRI Activation Reveals Cross-Modal Information in Auditory Cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology 107: 3428–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, Gillian. 1994. Medieval Ships and Shipping. The Archaeology of Medieval Britain, 3. London: Leicester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iosifyan, Marina, Anton Sidoroff-Dorso, and Judith Wolfe. 2022. Cross-Modal Associations between Paintings and Sounds: Effects of Embodiment. Perception 51: 871–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, Charles W., Calvin B. Kendall, M. H. King, and Fr. Lipp, eds. 2003. Bede Venerabilis: Opera Didascalica, Corpus Christianorum Series Latina, 123 A. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, Hildegard Elisabeth. 2014. Sensory Media: From Sounds to Silence, Sight to Insight. In A Cultural History of the Senses in the Middle Ages. Edited by Richard G. Newhauser. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 195–216. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Kimberly. 1989. Forgery, Invention and Propaganda: Factors behind the Production of the Guthlac Roll (British Museum Harley Roll Y.6). Athanor 8: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Johanna, Hugh Magennis, and Robin Norris, ed. and trans. 2020. Anonymous Old English Lives of Saints. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lauwereyns, Jan. 2018. Beyond Prediction: Self-Organization of Meaning with the World as a Constraint. In Advances in Cognitive Neurodynamics (VI): Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Cognitive Neurodynamics–2017. Singapore: Springer, pp. 383–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Liam. 2022. Animal Soundscapes in Anglo-Norman Texts. Cambridge: Boydell & Brewer. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, César F., Nadine Lavan, Samuel Evans, Zarinah Agnew, Andrea R. Halpern, Pradheep Shanmugalingam, Sophie Meekings, Daniel Boebinger, Manuel Ostarek, Carolyn McGettigan, and et al. 2015. Feel the Noise: Relating Individual Differences in Auditory Imagery to the Structure and Function of Sensorimotor Systems. Cerebral Cortex 25: 4638–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancia, Lauren. 2025. Embodied Epistemology as Rigorous Historical Method. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McGrail, Seán. 2001. Boats of the World: From the Stone Age to Medieval Times. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Noel, William. 1995. The Harley Psalter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Noetzel, Justin T. 2014. Monster, Demon, Warrior: St. Guthlac and the Cultural Landscape of the Anglo-Saxon Fens. Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies 45: 105–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, Radomil. 2020. Sound in Literary Texts. Neophilologus 104: 151–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuding, Emma. 2022. Fenland Pilgrimage: A Literary History of Guthlac of Crowland, Medieval to Modern. Ph.D. thesis, University of York, York, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Ogi, Manabu, Tatsuya Yamagishi, Hiroaki Tsukano, Nana Nishio, Ryuichi Hishida, Kuniyuki Takahashi, Arata Horii, and Katsuei Shibuki. 2019. Associative Responses to Visual Shape Stimuli in the Mouse Auditory Cortex. PLoS ONE 14: e0223242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkes, Henry. 2020. Musical Portraits of St Guthlac. In Guthlac: Crowland’s Saint. Edited by Jane Roberts and Alan Thacker. Donington: Shaun Tyas, pp. 277–97. [Google Scholar]

- Proverbio, Alice Mado, Guido Edoardo D’Aniello, Roberta Adorni, and Alberto Zani. 2011. When a Photograph Can Be Heard: Vision Activates the Auditory Cortex within 110 ms. Scientific Reports 1: 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, Jane. 2020. Guthlac on a Roll: BL, Harley MS Y.6. In Guthlac: Crowland’s Saint. Edited by Jane Roberts and Alan Thacker. Donington: Shaun Tyas, pp. 242–73. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Jane, and Alan Thacker. 2020. Introduction to Guthlac’s Life and Cult. In Guthlac: Crowland’s Saint. Edited by Jane Roberts and Alan Thacker. Donington: Shaun Tyas, pp. xv–xlvi. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwein, Barbara. 2015. Generations of Feeling: A History of Emotions, 600–1700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Semple, Sarah. 2002. Anglo-Saxon Uses and Perceptions of Prehistoric Monuments in Anglo-Saxon Society. Ph.D. thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, Richard. 2020. The Twelfth-Century Translation and Miracles of St Guthlac. In Guthlac: Crowland’s Saint. Edited by Jane Roberts and Alan Thacker. Donington: Shaun Tyas, pp. 485–553. [Google Scholar]

- Shores, Rebecca. 2021. Sounds of Salvation: Nautical Noises in Old English and Anglo-Latin Literature. In Meanings of Water in Early Medieval England. Edited by Carolyn Twomey and Daniel Anlezark. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 109–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tiihonen, Marianne, Niels Trusbak Haumann, Yury Shtyrov, Peter Vuust, Thomas Jacobsen, and Elvira Brattico. 2024. The Impact of Crossmodal Predictions on the Neural Processing of Aesthetic Stimuli. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 379: 20220418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, David, ed. 2014. Life of Guthlac. In Saints’ Lives: Henry of Avranches. Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Robert, and Roger Gryson, eds. 2007. Biblia Sacra Iuxta Vulgatam Versionem, 5th ed. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Duncan W., and Hugh Willmott. 2024. Sacred Landscapes and Deep Time: Mobility, Memory, and Monasticism on Crowland. Journal of Field Archaeology 49: 280–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).