Abstract

This study investigates different types of self-identification in terms of religiosity and/or spirituality and some psychosocial correlates of these categorizations. An Italian adult sample (N = 594) was divided into four groups: Religious and Spiritual (RS), Spiritual but not Religious (SnR), Religious but not Spiritual (RnS), and neither Religious nor Spiritual (nRnS). Participants completed measures assessing centrality of religion, spiritual orientation, religious orientations, and main motives in life. Statistical analyses (ANOVAs, t-tests) showed that RS individuals scored highest across all religiosity and spirituality dimensions, with a predominantly intrinsic orientation and strong focus on all life motives, especially self-realization. SnR individuals reported low religiosity but high spirituality, especially concerning meaning and sacredness of life, along with attributing importance to different life motives, particularly to self-realization and meaning. RnS participants showed limited engagement in both religiosity and spirituality, valuing primarily ideological and meaning-related aspects, while nRnS reported minimal scores in religiosity and spirituality, though the pursuit of meaning remained salient. Overall, meaning emerged as a central dimension across all groups, suggesting its role as a universal human motivation. Findings underscore the non-overlapping yet interrelated nature of spiritual and religious identities and their different implications in individual experiences and motives in life.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, Western societies have undergone significant social transformations regarding how individuals experience their existential dimension in relation to traditional religious institutions (Marshall and Olson 2018), with an increasing tendency toward scientific objectification—based on the assumption that only quantifiable phenomena can be adequately represented and analyzed. Consequently, engagement with the transcendental and religious aspects of individual life has progressively lost cultural importance (Hill et al. 2000; Richardson 2013).

Within these sociocultural shifts, the search for transcendence (Richardson 2013) has progressively evolved into forms of “religious individualism” namely, the inclination to cultivate and experience one’s own religious dimension within a private and personal sphere, without adherence to institutional affiliations or formal religious services (Ammerman 2013; Marshall and Olson 2018). This trend addresses a persistent “need for transcendence in the postmodern world,” conceived as the pursuit of spiritual and transcendental experiences cultivated also outside traditional religious frameworks (Havel 1985).

Recent survey data substantiate these changes. The Pew Research Center (Kramer et al. 2022) reported a decrease in self-identified Christians in the United States from 78% in 2007 to 63% in 2019, alongside an increase in those identifying as non-religious from 16% to 26% (Simmons 2021). Marler and Hadaway (2002) observed that 18–20% of the U.S. population self-identified as “spiritual but not religious”, consistent with data from Willard and Norenzayan (2017), who reported that approximately 30% of U.S. citizens identified with this category from 2009. Streib and Hood (2011) later found that nearly 37% of members of religious organizations described themselves as “more spiritual than religious.”

A similar picture has been observed in the Italian context. The Italian Religion and Spirituality Project (Palmisano 2010) reported that, in 2006, 25% of respondents identified as not religious or only slightly religious, while 31% expressed an interest in cultivating their spiritual life. Moreover, 80% believed in the possibility of a spiritual life independent of organized religion, and 36% disagreed with the importance of church or community membership. Notably, 72% reported having a spiritual life, including 26% of non-religious respondents. More recent Italian data (CENSIS 2024) showed that, despite 70% of Italians self-identifying as Catholic, 40% did not feel represented by the institutional Church, 21% were “non-practicing Catholics”, and 56% reported not participating in religious services because “they live their faith internally.”

This changing cultural and historical framework has received growing attention from psychologists interested in exploring how individuals live and experience their religiosity in terms of meaning, salience, and intensity. Allport and Ross (1967), distinguished between intrinsic religiosity—characteristic of individuals viewing their religious beliefs as a primary motivational drive or life goal—and extrinsic religiosity—present when religion serves as an instrumental means to achieve social acceptance or other personal benefits. Batson and Schoenrade (1991) further conceptualized religion as a means (an instrumental approach to religiosity) and as an end (when it becomes a value in itself). He also introduced a third orientation, named quest, characterized by an open and ongoing search for religious and existential understanding.

Glock and Babbie (1973), see also Stark and Glock (1968) further delineated five core dimensions of religiosity (see also Huber and Huber 2012): the intellectual, or the degree of knowledge about one’s religion and ability to explain religious issues; the ideological, or the beliefs about the existence and essence of a transcendent reality; the ritualistic, differentiated into public practices and private practices; and the experiential, referring to the direct and emotional experience of the transcendent.

In line with this in-depth investigation of the psychological meanings and changes in religiosity, scholars have drawn a distinction between being religious and being spiritual. While “religious” generally refers to an individual who adheres to an organized, communal, and doctrinal system (Ammerman 2013; Lindeman et al. 2019), “spiritual” relates to a more individualized search for meaning, purpose, and the sacred, typically associated with enhanced connections to oneself, others, nature, or the transcendent (Chen et al. 2023; de Jager Meezenbroek et al. 2010; Harris et al. 2018; Johnson et al. 2018; Heelas and Woodhead 2005).

In this sense, spirituality implies a sense of transcendence beyond the self and the routine and incidental experiences and activities of daily life (Richardson 2013), often manifesting as a multifaceted connectedness with a higher power, divinity, or supernatural realm, as well as with nature, others, humanity, or the cosmos (Schnell 2012; Streib and Hood 2013; Williamson and Ahmad 2019). These dimensions can be consistent with institutional religious teachings, but not necessarily.

Accordingly, spirituality and religiosity can be understood as non-overlapping dimensions, outlining four possible categories of individuals (Marshall and Olson 2018; Simmons 2021).

1. “Religious and spiritual”: individuals who consider spiritual experience integral to their religious identity and cultivate their spiritual life within an institutionalized religion.

2. “Spiritual but not religious”: this increasingly used category describes individuals who express spirituality without religious involvement. Rather than denying the possibility of a deity, they typically reject institutionalized forms of theism (Lindeman et al. 2019). Such individuals often define spirituality in terms of a general and holistic sense of connectedness—with self, nature and other people—and ethical actions (Steensland et al. 2018).

3. “Religious but not spiritual”: those who identify with an institutional religion—often practicing rituals and adhering to dogmas—without giving importance to the transcending feelings of connection that generally characterize spirituality (Simmons 2021).

4. “Neither religious nor spiritual”: individuals reporting the absence of religiosity and spiritual engagement (Chen et al. 2023).

Many authors have explored how religious and spiritual dimensions relate to conceptions of well-being and to the motivations underlying their pursuit, conceptualizing well-being as either hedonic—focused on immediate pleasure and the avoidance of suffering (Huta and Ryan 2009)—or eudaimonic—emphasizing self-realization, personal growth, and meaning-making through the development of one’s potential (Ryff 1989, 2021). Subsequent research has delineated several, non-mutually exclusive motives for pursuing well-being—from the search for hedonistic pleasure to the eudaimonic pursuit of self-realization and existential meaning (Huta and Ryan 2009; Huta and Waterman 2013). To these, Oishi et al. (2019) added the idea of a “good life,” understood as “rich” in new experiences, stimuli, and sensations capable of broadening or transforming one’s perspectives (Oishi and Westgate 2022).

Overall, the degree to which people identify with religiosity and spirituality appears to shape both their subjective well-being and the motivations underlying its pursuit. Religiosity and spirituality are closely linked to personal values, goals, and the search for meaning (Schnell 2012), as well as life satisfaction, social support (VanderWeele 2017), and the ability to cognitively restructure events (Ryff 2021). Moreover, possessing a spiritual dimension is associated with self-awareness, generativity, a sense of connectedness with nature, and social engagement (Schnell 2012), but it is also linked to subjective well-being through self-transcendent emotions—such as awe, hope, love, and forgiveness (Davis et al. 2013; de Brito Sena et al. 2021).

While these studies demonstrate the significance of religious and spiritual identification, no research investigates in depth the psychological correlates of self-definition across the four combinations outlined above.

Within this theoretical framework, the present study aimed to explore, within an Italian sample, the different types of self-identification in terms of religiosity and/or spirituality and the possible differences between these categorizations in centrality of religion, religious orientations, spiritual experiences and beliefs, and main motives in life.

2. Materials and Method

For this study, we employed a quantitative cross-sectional comparative design using self-report measures. This approach is appropriate for detecting group-level differences at a single time point across naturally occurring self-categorizations in religiosity and spirituality. The study procedure was approved by the Ethical Committee for Psychological Research of the University of Padova, protocol #1528-a. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 29.0.1.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA)

2.1. Participants

Participants were recruited by a research assistant and by students enrolled in a psychology course at the University of Padua in return for course credits. Each student invited six Italian adults (if possible, three women and three men) to complete an online questionnaire. Eligibility criteria were: willingness to participate in the study; not being students in the same course; and not having frequent interactions with one another, to reduce potential dependence among observations. Information regarding the study’s purposes, the anonymity of responses, and the right to withdraw at any time was provided within the informed consent form. Participation was voluntary and not compensated. A total of 598 participants answered the questionnaire. Given the aims of the present study—focusing on religious and spiritual self-categorization—four participants were excluded because they did not categorize themselves as either religious or non-religious and as either spiritual or non-spiritual. This self-identification operationalization is common in research on religious/spiritual (R/S) identity (Ammerman 2013). No additional exclusion criteria were applied. The final sample thus comprised 594 subjects aged 18–76 years (M = 36.07, SD = 15.95); 55% were female and 45% male. Regarding educational level: 8% attained a high level of specialization; 32% were students; and 5% were retired, unemployed or housekeepers.

2.2. Measures

Respondents were asked to complete an online module. Before the questionnaires, participants had to provide some socio-demographic information and indicate whether they considered themselves religious (and, if so, to which religion they belonged), spiritual, atheist, or agnostic. The scales included in the questionnaire are reported below.

The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS; Huber and Huber 2012) measured the degree of religious centrality across five dimensions: public practices (belonging to a religious community and participation in rituals and collective activities); private practices (personal engagement with the transcendent dimension through prayers, activities, and personal rituals exercised in private settings); experience (direct, personal, and emotional contact with a transcendent essence); ideology (personal convictions about the existence of a transcendent and/or divine dimension); and intellectual dimension (personal knowledge and elaboration of thoughts on religious themes). Before completing the scale, participants were told to respond according to their personal idea of “God” or “something divine”, leaving each person free to define it according to their own experience. The scale included 20 items with different response formats: a 5-point scale (from 1 = not at all to 5 = very much), an 8-point scale (from 1 = several times a day to 8 = never) and a 6-point scale (from 1 = more than once a week to 6 = never) for items exploring frequency of prayer, meditation and religious service attendance. To facilitate comparability across dimensions, responses on the 8- and 6-point formats were rescaled to a 1–5 metric. For the present research, we used an Italian translation of the scale. Reliability was good for intellectual (α = 0.83) and excellent for ideology (α = 0.93), public practice (α = 0.91), private practice (α = 0.91), and experience (α = 0.92).

The Spiritual Orientation Inventory (SOI; Elkins et al. 1988) is a multidimensional measure of humanistic spirituality—understood as spiritual experience not necessarily linked to a specific religious faith. We administered an Italian translation of 44 out of the 85 items originally included in the full scale1, tapping seven dimensions: transcendence (belief that there is a transcendent dimension of life based on experience, which goes beyond the here and now); meaning/purpose of life (experiencing a search for meaning and purpose, with an awareness that life is profoundly meaningful); mission in life (a sense of vocation, a feeling of having a personal calling to respond to); sacredness of life (belief that life is sacred, with a feeling of reverential awe towards all its facets, even the mundane ones); (non) material values (predominance of spiritual goods over material goods in achieving ultimate personal satisfaction); awareness of the tragic (awareness of the tragic dimensions of human existence, which enhances the appreciation and valuing of life); and fruits of spirituality (experience of the positive effects of spirituality on one’s life and on relationships with oneself, others, and transcendence). The original scale also included the dimensions of idealism and altruism, which were excluded as they primarily assess dimensions that are consequent to (or related to) spirituality rather than constitutive of it2. Items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (from 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree”). Internal consistency spanned from sufficient (meaning: α = 0.61; sacredness of life: α = 0.67) to acceptable (awareness of the tragic: α = 0.78), good (mission: α = 0.84; non-materialism: α = 0.86), and excellent (transcendence: α = 0.91; fruits of spirituality: α = 0.95).

The Religious Life and Orientations Scale (Voci et al. 2017) is an instrument designed to measure three religious orientations: intrinsic/end, extrinsic/means, and quest. The scale consists of 18 items, selected by Voci et al. (2017) from the Religious Orientation Scale (Allport and Ross 1967) and the Religious Life Inventory (Batson et al. 1993), divided into the three subscales. Responses were provided on a 7-point Likert scale (from 1 “the statement does not describe me at all” to 7 “the statement describes me very well”). Reliability was acceptable to good across the subscales: extrinsic: α = 0.70; quest: α = 0.74; intrinsic: α = 0.88.

The Four Motives in Life (FML) is a scale designed for this study to assess four primary life motives: meaning (striving to find profound significance in what one does), pleasure (enjoyment of life and its offerings), rich life (seeking new, complex, interesting, and sometimes challenging experiences that broaden one’s perspective), and self-realization (developing one’s potential). The scale consists of 12 items, divided into four subscales mirroring the four motives, with responses provided on a 7-point Likert scale (from 1 “not at all like me” to 7 “very much like me”). The reliability of the four subscales spanned from sufficient (meaning: α = 0.68; rich life: α = 0.68) to good (self-realization: α = 0.82; pleasure: α = 0.86).

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Given the observational, cross-sectional nature of the study, we interpreted effects as between-group differences, without inferring causality. First, we defined four groups of participants based on the intersection of self-categorization in terms of religiosity and spirituality: Religious and Spiritual (RS); Spiritual but not Religious (SnR); Religious but not Spiritual (RnS); Neither Religious nor Spiritual (nRnS).

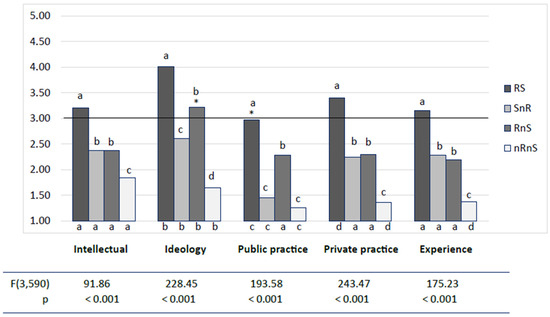

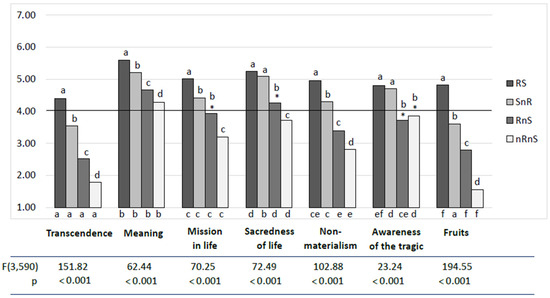

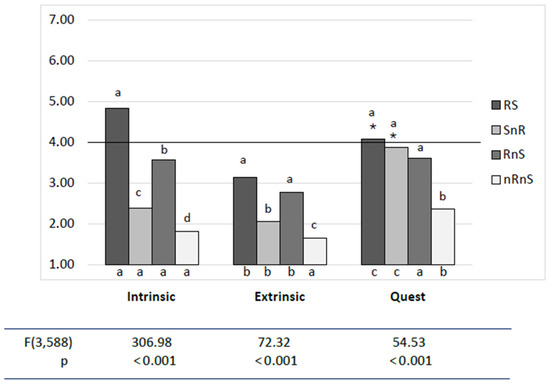

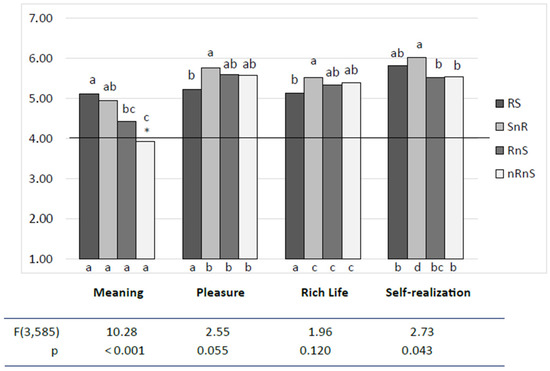

Then, we conducted a series of one-way ANOVAs and post hoc comparisons using the Bonferroni correction to examine mean differences across the four groups for each construct or dimension. ANOVA results are reported in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4; results of the post hoc comparisons are indicated by letters placed above the histogram bars (different letters indicate different means, with p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Centrality of Religiosity: Mean Scores and Comparisons. Note. RS = Religious and Spiritual; SnR = Spiritual but not Religious; RnS = Religious but not Spiritual; nRnS = neither Religious nor Spiritual. For each dimension, different letters above histograms indicate different means between groups, with p < 0.05. For each group, different letters below histograms indicate different means between the dimensions, with p < 0.05. Asterisks indicate non-significant differences between mean scores and scale midpoint.

Figure 2.

Spiritual orientations: Mean Scores and Comparisons. Note. RS = Religious and Spiritual; SnR = Spiritual but not Religious; RnS = Religious but not Spiritual; nRnS = neither Religious nor Spiritual. For each dimension, different letters above histograms indicate different means between groups, with p < 0.05. For each group, different letters below histograms indicate different means between the dimensions, with p < 0.05. Asterisks indicate non-significant differences between mean scores and scale midpoint.

Figure 3.

Religious orientations: Mean Scores and Comparisons. Note. RS = Religious and Spiritual; SnR = Spiritual but not Religious; RnS = Religious but not Spiritual; nRnS = neither Religious nor Spiritual. For each dimension, different letters above histograms indicate different means between groups, with p < 0.05. For each group, different letters below histograms indicate different means between the dimensions, with p < 0.05. Asterisks indicate non-significant differences between mean scores and scale midpoint.

Figure 4.

Four motives in life: Mean Scores and Comparisons. Note. RS = Religious and Spiritual; SnR = Spiritual but not Religious; RnS = Religious but not Spiritual; nRnS = neither Religious nor Spiritual. For each dimension, different letters above histograms indicate different means between groups, with p < 0.05. For each group, different letters below histograms indicate different means between the dimensions, with p < 0.05. Asterisks indicate non-significant differences between mean scores and scale midpoint.

Furthermore, through a series of paired-sample t-tests, we compared the means of the different subscales within each of the four groups. The results of the paired-sample t-tests are shown in the figures using letters placed below the histogram bars (different letters indicate different means, with p < 0.05).

Finally, using one-sample t-tests, we compared each score, within the four groups and for the different subscales, with the midpoint of the respective response scales. In the figures, asterisks are used to denote non-significant differences between mean scores and scale midpoints. Missing data were handled pairwise (available-case).

3. Results

3.1. Self-Definition of Participants

Of the 594 participants, 309 (52%) self-identified as religious and 354 (60%) as spiritual. Regarding self-categorization along the two dimensions of religiosity and spirituality, 242 participants (41% of the sample) self-identified as both “religious” and “spiritual” (RS), 112 (19%) only as “spiritual” (SnR), 67 (11%) only as “religious” (RnS), and 173 (29%) as neither “religious” nor “spiritual” (nRnS).

3.2. Centrality of Religiosity Scale

As shown in Figure 1, the one-way ANOVAs yielded significant results for all the CRS subscales. The dimensions of ideology and public practice exhibited a similar trend: both were highest among RS, less present for RnS, lower for SnR, and almost absent for nRnS. The particularly high ideology scores among RS participants (and subsequently, within RnS) suggest that this dimension is closely tied to the presence of a religious component, which tends to decrease when this component is absent. Similarly, public practices, although generally lower across all groups, appeared more frequent among individuals with a religious orientation (RS and RnS), whereas SnR showed significantly lower scores, consistent with a more private and individualistic expression of their spiritual experience. A partly similar pattern emerged for the intellectual, private practice, and experience dimensions: RS scored highest across all three dimensions, followed by SnR and RnS (whose mean scores did not differ significantly), and finally nRnS, which consistently reported very low scores.

3.3. Spiritual Orientation Inventory

One-way ANOVAs showed significant results for all the SOI subscales (Figure 2). A similar pattern was observed across the dimensions of transcendence, meaning, non-materialism, and fruits of spirituality: the highest scores were present among RS, followed by progressively lower scores for SnR, RnS, and nRnS. Notably, these dimensions—particularly the search for meaning and the perceived fruits of one’s spirituality—were more pronounced among individuals with a personal spiritual dimension and appeared reinforced in RS by the adherence to a religious tradition. Interestingly, the search for meaning was still present among nRnS participants, although with lower mean scores compared to the other groups.

The perception of having a mission in life and a sense of fulfillment not based on material possessions were particularly strong among RS, followed by SnR; both dimensions were less present among nRnS individuals, with significantly lower scores also found for RnS with respect to non-material values.

Finally, the dimensions of sacredness of life and awareness of the tragic were similarly present in both RS and SnR, reflecting the predominance of the spiritual dimension over the religious one. Significantly lower scores on both dimensions were observed in RnS and, for sacredness of life, also among nRnS.

3.4. Religious Orientations

A significant variation among the four groups was observed for religious orientations, as reflected by the significant results of the ANOVAs (Figure 3). For intrinsic orientation, the highest mean score, above the scale midpoint, was found for RS, followed by progressively lower scores for RnS, SnR, and nRnS. Results for quest orientation were more homogeneous, with consistently high scores across all groups except for nRnS participants. This suggests that respondents in our sample who have a religious and/or a spiritual dimension in their life generally tend to adopt an open-ended, questioning approach to religious issues and existential questions.

Lower scores were found across all categories of participants for the extrinsic orientation, with comparable means for RS and RnS, and significantly lower scores for SnR, probably reflecting a more inward and private approach to spirituality with limited involvement in institutional religious communities.

3.5. Four Motives in Life

Examining motives in life (Figure 4), the ANOVAs showed significant results for meaning and self-realization. For meaning, high and comparable scores were observed in RS and SnR, with nRnS reporting a significantly lower mean; RnS scored midway between nRnS and RS, but lower than RS participants. This pattern suggests that the motivation for meaning may be particularly associated with the cultivation of a personal spiritual dimension. The motivation for self-realization was notably present in both SnR and RS, whereas RnS and nRnS participants reported significantly lower scores compared to SnR. This motivation, too, appeared to be linked to a certain degree of spirituality.

Finally, slight differences between groups were found for pleasure and rich life, which showed a similar pattern: their scores were higher for SnR than RS, with intermediate levels for RnS and nRnS.

4. Discussion

The results of this study allow us to observe the experiences and motivations connected to self-identification in terms of religiosity and spirituality. Specifically, it emerged that those who identify as both religious and spiritual (RS) present high levels for most dimensions of religiosity, particularly ideology—consistent with adherence to an institutionalized faith—and moderate participation in public practices. Similarly, RS participants also scored highly on all spirituality dimensions, with particular emphasis on meaning and sacredness of life. These patterns are consistent with a predominantly intrinsic religious orientation, lower scores on extrinsic orientation and intermediate scores for quest orientation within this category of participants. Finally, RS participants attribute importance to all four life motivations, with particular attention to the drive for self-realization.

Regarding participants who considered themselves spiritual but not religious (SnR), the situation differs: religiosity dimensions were not particularly relevant, specifically participation in publicly shared practices. This aligns with literature emphasizing how this category experiences spirituality as primarily experiential and private, rejecting adherence to institutionalized faith and community practices (Ammerman 2013; Zinnbauer et al. 1997). Spirituality dimensions were generally high, particularly meaning and sacredness of life, with less relevant values for transcendence and fruits. The predominance of meaning and importance attributed to the sacred are consistent with the spiritual experience of these participants, characterized by a particularly experiential search for sacredness outside religiously coded contexts (Streib and Hood 2011). This also aligns with the intermediate values reported by SnRs for quest orientation, specifically aimed at research and deeper understanding of religious and existential contents, in contrast with markedly lower levels reported for intrinsic and extrinsic orientations. Finally, all main life motivations have relevant scores for this category, particularly self-realization and pleasure, perhaps due to an individualistic and/or hedonistic tendency that can characterize the spiritual experience for some. Future research should further analyze motivations leading a person to seek spiritual and transcendent dimensions outside an institutional religious context and investigate potential individual differences.

Results regarding RnS individuals pertain to a category that remains poorly delineated in the literature. Consistent with previous works that distinguished religiosity (organized, communal, doctrinal involvement) from spirituality (an individualized search for meaning, purpose, and the sacred; e.g., Heelas and Woodhead 2005; Hill et al. 2000; Zinnbauer and Pargament 2005), we use the label “religious but not spiritual” (RnS) as in Simmons (2021). A plausible profile for RnS may involve formal identification with a religious tradition and social/ritual participation, coupled with limited private spiritual cultivation (e.g., baptized but non-practicing individuals). However, these examples are illustrative rather than definitional, underscoring the need for further work to specify the contours of the RnS category. Compared to the RS group, RnS individuals generally reported lower levels in all the variables related to religiosity and spirituality, showing the effect of the lack of a spiritual dimension. The only religious and spiritual dimensions that seemed relatively relevant for them are ideology and meaning, confirming these aspects as particularly associated with self-perception as a religious person (Steger et al. 2010). Moreover, RnS showed similar levels in intrinsic and quest religious orientations, with values slightly below the midpoint of the scale, plausibly in line with a mere adherence to a religious cult. Particularly relevant for this group are motivations of self-realization, rich life, and pleasure. Given the complexity of these results, and the possible heterogeneity within this category, further research is needed to investigate more deeply the features that characterize this peculiar self-categorization.

Finally, individuals reporting to be neither religious nor spiritual (nRnS) showed, coherently, almost absent dimensions of religiosity and religious orientations. However, the spiritual dimension of meaning was relevant, and dimensions of awareness of the tragic and sacredness of life were present at intermediate, or at least not particularly low levels. With respect to life motives, nRnS showed high scores for pleasure, rich life, and self-realization, attributing significantly less importance to meaning.

It is notable that the SOI dimension of meaning was present, and in some cases predominant, across all groups. This confirms that the search for meaning—whether religiously coded or not—can be considered as a human need (Heine et al. 2006), although it may manifest in different ways depending on the presence or absence of religious and spiritual dimensions. For example, meaning may be theologically and communally anchored among RS, immanent and relational among SnR, identity- and value-based among RnS, and secular/project-driven among nRnS; however, these interpretations remain speculative. Future work should complement self-report measures with qualitative methods (e.g., in-depth interviews, narrative/goal content analyses, experience sampling) to elicit first-person understandings of what ‘meaning’ entails in each group.

Another relevant finding is that those who define themselves as spiritual (both RS and SnR) tend to place considerable importance on sacredness of life. This is particularly relevant among SnR individuals, who—consistent with prior literature—show diverse understandings of the sacred and the divine (Streib and Hood 2011; Zinnbauer and Pargament 2005), referring to how such realities are conceptualized and experienced. Specifically, the literature indicates that, alongside individuals who do not endorse structured religious interpretations, there are those who conceive of God in a traditional sense or, more commonly, as an impersonal/mystical force immanent within human beings and nature (Chen et al. 2023; Palmisano 2010; Wixwat and Saucier 2021). Notably, an immanent understanding of sacredness may also be relevant for non-spiritual respondents (RnS and nRnS), given that the perception of sacredness of life was present to a certain degree for them as well.

Moreover, it is possible that even the main life motives take on different meanings depending on the individual’s religious and/or spiritual orientation (Emmons et al. 1998). For example, while self-realization was salient across groups, it would be informative to examine how its content differs by self-categorization, potentially revealing more or less individualistic orientations.

This study has some limitations. First, we relied exclusively on self-report measures; given the subjective nature of the focal constructs (religious centrality, spiritual orientation, and motives in life), self-report is appropriate, but future research could complement these measures with qualitative data (e.g., open-ended prompts, interviews) to deepen construct content. Second, group assignment relied on self-identification rather than behavioral indicators or doctrinal assent, which makes it difficult to determine how these identities map onto practices or specific commitments. Third, the administered questionnaires did not provide a clear definition of spirituality distinct from religiosity, which may have introduced non-uniform understandings of the proposed categorizations. Fourth, despite the breadth of the general sample obtained, the reduced size resulting from its subdivision into four subgroups could have impacted on the strength and potential value of some of the emerged results, particularly for the less numerous RnS group. Finally, socio-demographic variables were collected for descriptive purposes only and were not analyzed for group differences.

To overcome these limitations, future studies should: (a) collect data from larger samples to ensure adequate sizes for the different groups investigated; (b) provide participants with clear operational definitions of religiosity and spirituality to ensure a comparable interpretation of self-categorization across respondents; (c) adopt hybrid classification rules that combine self-identification with behavioral thresholds (e.g., religious service attendance, private practice frequency, experiential endorsement) or derive groups via latent profile analysis from CRS/SOI indicators; (d) employ mixed-methods (e.g., in-depth interviews, narrative/goal-content analyses, experience sampling) to add depth to first-person understandings of religiosity, spirituality, and existential values; and (e) examine whether age, gender, education, or occupational status moderate the observed patterns. It would also be useful to explore how people understand spirituality across profiles—for example, distinguishing between vertical spirituality, connected with a divine and immaterial dimension, and horizontal spirituality, linked to material dimensions such as humanity, nature, or the cosmos (Voci 2024).

In conclusion, we believe that this research may offer a contribution to understanding people’s religious and spiritual dimensions. The findings suggest that these dimensions are distinct yet neither fully overlapping nor perfectly orthogonal (the RnS group appears to be significantly smaller than the others) and that self-categorization in terms of religiosity and spirituality is characterized at the same time by notable differences and interesting similarities in terms of religious and spiritual experiences and feelings, as well as important motives in life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.U., E.P. and A.V.; methodology, E.P. and A.V.; formal analysis, A.V.; data curation, E.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.U.; writing—review and editing, E.P. and A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee for Psychological Research of the University of Padova (protocol #1528-a, approved 9 October 2025) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymised raw data are available at figshare; https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30692393.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | We conducted a selection process on the original scale items to reduce potential redundancy in formulations and retain only those items whose content fully aligned with their respective spiritual dimensions. |

| 2 | See note 1 above. |

References

- Allport, Gordon W., and J. Michael Ross. 1967. Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5: 432–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2013. Spiritual but not religious? Beyond binary choices in the study of religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 258–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C. Daniel, and Patricia A. Schoenrade. 1991. Measuring religion as quest: 2) Reliability concerns. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 30: 430–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, Charles Daniel, Patricia Schoenrade, and W. Larry Ventis. 1993. Religion and the Individual: A Social-Psychological Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- CENSIS. 2024. Italiani, Fede e Chiesa. Una Ricerca Censis-Essere Qui per il Cammino Sinodale. Roma: CENSIS. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Zhuo Job, Richard G. Cowden, and Heinz Streib. 2023. More spiritual than religious: Concurrent and longitudinal relations with personality traits, mystical experiences, and other individual characteristics. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 1025938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Don E., Everett L. Worthington, Jr., Joshua N. Hook, and Peter C. Hill. 2013. Research on religion/spirituality and forgiveness: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 5: 233–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito Sena, Marina Aline, Rodolfo Furlan Damiano, Giancarlo Lucchetti, and Mario Fernando Prieto Peres. 2021. Defining spirituality in healthcare: A systematic review and conceptual framework. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 756080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jager Meezenbroek, Eltica, Bert Garssen, Machteld van den Berg, Dirk Van Dierendonck, Adriaan Visser, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2010. Measuring spirituality as a universal human experience: A review of spirituality questionnaires. Journal of Religion and Health 51: 336–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkins, David N., L. James Hedstrom, Lori L. Hughes, J. Andrew Leaf, and Cheryl Saunders. 1988. Toward a humanistic-phenomenological spirituality. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 28: 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, Robert A., Chi Cheung, and Keivan Tehrani. 1998. Assessing spirituality through personal goals: Implications for research on religion and subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research 45: 391–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glock, Charles Y., and Earl R. Babbie. 1973. Religion in Sociological Perspective: Essays in the Empirical Study of Religion. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Kevin A., Desiree S. Howell, and Don W. Spurgeon. 2018. Faith concepts in psychology: Three 30-year definitional content analyses. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 10: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havel, Václav. 1985. Forgetting we are not God. First Things 51: 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Heelas, Paul, and Linda Woodhead. 2005. The Spiritual Revolution. Why Religion Is Giving Way to Spirituality. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Heine, Steven J., Travis Proulx, and Kathleen D. Vohs. 2006. The meaning maintenance model: On the coherence of social motivations. Personality and Social Psychology Review 10: 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, Peter C., Kenneth II Pargament, Ralph W. Hood, Jr., Michael E. McCullough, James P. Swyers, David B. Larson, and Brian J. Zinnbauer. 2000. Conceptualizing religion and spirituality: Points of commonality, points of departure. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 30: 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Stefan, and Odilo W. Huber. 2012. The centrality of religiosity scale (CRS). Religions 3: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huta, Veronika, and Alan S. Waterman. 2013. Eudaimonia and its distinction from Hedonia: Developing a classification and terminology for understanding conceptual and operational definitions. Journal of Happiness Studies 15: 1425–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huta, Veronika, and Richard M. Ryan. 2009. Pursuing pleasure or virtue: The differential and overlapping well-being benefits of hedonic and Eudaimonic motives. Journal of Happiness Studies 11: 735–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Kathryn A., Carissa A. Sharp, Morris A. Okun, Azim F. Shariff, and Adam B. Cohen. 2018. SBNR identity: The role of impersonal god representations, individualistic spirituality, and dissimilarity with religious groups. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 28: 121–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, Stephanie, Conrad Hackett, and Kelsey Beveridge. 2022. Modeling the Future of Religion in America. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Lindeman, Marjaana, Michiel Van Elk, Jari Lipsanen, Pinja Marin, and Uffe Schjødt. 2019. Religious unbelief in three western European countries: Identifying and characterizing unbeliever types using latent class analysis. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 29: 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marler, Penny Long, and C. Kirk Hadaway. 2002. “Being religious” or “Being spiritual” in America: A zero-sum proposition? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, Joey, and Daniel V. A. Olson. 2018. Is ‘Spiritual but not religious’ a replacement for religion or just one step on the path between religion and non-religion? Review of Religious Research 60: 503–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, Shigehiro, and Erin C. Westgate. 2022. A psychologically rich life: Beyond happiness and meaning. Psychological Review 129: 790–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oishi, Shigehiro, Hyewon Choi, Nicholas Buttrick, Samantha J. Heintzelman, Kostadin Kushlev, Erin C. Westgate, Jane Tucker, Charles R. Ebersole, Jordan Axt, Elizabeth Gilbert, and et al. 2019. Psychologically rich life questionnaire. PsycTESTS Dataset. [CrossRef]

- Palmisano, Stefania. 2010. Spirituality and Catholicism: The Italian experience. Journal of Contemporary Religion 25: 221–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, Frank C. 2013. Investigating psychology and transcendence. Pastoral Psychology 63: 355–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, Carol D. 1989. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57: 1069–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, Carol D. 2021. Spirituality and well-being: Theory, science, and the nature connection. Religions 12: 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, Tatjana. 2012. Spirituality with and without religion—Differential relationships with personality. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 34: 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J. Aaron. 2021. Religious, but not spiritual: A constructive proposal. Religions 12: 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Rodney, and Charles Y. Glock. 1968. American Piety: The Nature of Religious Commitment. Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steensland, Brian, Xiaoyun Wang, and Lauren Chism Schmidt. 2018. Spirituality: What does it mean and to whom? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 57: 450–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, Michael F., Natalie K. Pickering, Erica Adams, Jennifer Burnett, Joo Yeon Shin, Bryan J. Dik, and Nick Stauner. 2010. The quest for meaning: Religious affiliation differences in the correlates of religious quest and search for meaning in life. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 2: 206–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streib, Heinz, and Ralph W. Hood. 2011. “Spirituality” as privatized experience-oriented religion. Implicit Religion 14: 433–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streib, Heinz, and Ralph W. Hood. 2013. Modeling the religious Field. Implicit Religion 16: 137–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, Tyler J. 2017. Religion and health: A synthesis. In Spirituality and Religion Within the Culture of Medicine: From Evidence to Practice. Edited by Michael J. Balboni and John R. Peteet. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, pp. 357–401. [Google Scholar]

- Voci, Alberto. 2024. L’importanza della dimensione religiosa e spirituale nel fine vita. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia 4: 833–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voci, Alberto, Giulia L. Bosetti, and Chiara A. Veneziani. 2017. Measuring religion as end, means, and quest: The Religious Life and Orientation Scale. TPM—Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology 24: 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, Aiyana K., and Ara Norenzayan. 2017. “Spiritual but not religious”: Cognition, schizotypy, and conversion in alternative beliefs. Cognition 165: 137–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, W. Paul, and Aneeq Ahmad. 2019. The bidirectional spirituality scale: Construction and initial evidence for validity. Spiritual Psychology and Counseling 4: 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wixwat, Maria, and Gerard Saucier. 2021. Being spiritual but not religious. Current Opinion in Psychology 40: 121–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinnbauer, Brian J., and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2005. Religiousness and Spirituality. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York and London: The Guilford Press, pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer, Brian J., Kenneth I. Pargament, Brenda Cole, Mark S. Rye, Eric M. Butfer, Timothy G. Belavich, Kathleen Hipp, Allie B. Scott, and Jill L. Kadar. 1997. Religion and spirituality: Unfuzzying the fuzzy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 4: 549–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).