Abstract

This essay expands the canon of sources for liberative theologies by examining the artwork of leading Caribbean muralist Sir Dunstan St. Omer. In conjunction with his close friend—Nobel Laureate Sir Derek Walcott—St. Omer pioneered a form of artistic expression which he used to great and imaginative effect as counter-narrative to dehumanizing colonial myth. The essay presents two of the artist’s best-known murals, discusses their significance in the arc of Caribbean religiosity, and extrapolates critical insight for a contemporary Black Catholic mysticism.

1. Introduction: Ancient Wounds

The St. Lucian Nobel Laureate in literature, Sir Derek Walcott, in his epic poem Omeros (the “most ambitious English language poem of the decolonized Third World”, Ramazani (1997)), evokes the trope of a wound to signify the Caribbean colonial experience (Walcott 1992). The poem is partly set on the Caribbean island of St. Lucia. Philoctete—a black fisherman and the descendent of slaves—is one of its main characters.

The poem opens with Philoctete describing to a group of tourists how a canoe was made from a tree. He also has a severe wound on his leg made by a rusted anchor, which is now covered in scar tissue.

‘This is how, one sunrise, we cut down them canoes.Philoctete smiles for the tourists, who try taking his soul with their cameras.[…] For some extra silver, under a sea-almond,he shows them a scar made by a rusted anchor,rolling one trouser-leg up with a rising moanof a conch…. He does not explain its cure.“It have some thing”—he smiles—“worth more than dollar.”(I, i; pp. 3–4)

In Walcott’s poem, Philoctete’s wound is a complex symbol of colonial injury; it is a site of both pain and cure, of wounding and healing, of victimization and agency. As a symbol, it hearkens to the legacy of pain and colonization endured by the people of the Caribbean, as well as to the legacy of resistance, re-creation and self-determination by which modern day Caribbean life was constituted (Mintz 1974).

Caribbean Theology has offered one vehicle for giving voice to this experience of ancient woundedness. Subjected to forced displacement, African natives were divorced from the semiotic system of native culture, community and ecology (Jennings 2010). Stripped of name, relationships, and other identity signifiers, denuded of human subjectivity, the slave could be commodified, sold as property, completing the reconfiguration of the displaced body (Johnson 1999). Their descendants bear the legacy of this colonial wound, and their theologies populate a matrix of symbols for finding and expressing meaning in this complex existence.

This essay’s thesis is that the theological representation of Caribbean wounded existence has revealed important vistas of a contemporary Black Catholic mysticism. Specifically, by examining the sacred art of St. Lucian muralist Sir Dunstan St Omer, this essay proposes three characteristics of a contemporary mysticism: (1) It has an inherent sacramentality; (2) It privileges a responsibility to memory; and (3) It necessarily converges with the political.

To support these claims, this work draws on the broad methodological influences of Caribbean theologies of liberation. While the contours and nuances of the Caribbean theological tradition resist easy summary, in the main it has served to counter the denigration of human being in history. Dehumanization has been constitutive in the establishment of Caribbean society when African slaves were redefined as capital, allowing for the subjugation and abuse of their bodies. Today, as inheritors of this legacy, Caribbean persons are often deemed insignificant on the world stage, hybridized products of more venerable mother/European cultures. While Caribbean colonial religion has largely been complicit in the project of enslavement—interpreting the biblical narrative to serve the exclusive interests of the ruling planter class and fostering a slave spirituality of docility and subservience (Augier and Gordon (1962))—more significantly, slave religion and theology have served as radical counter-narrative and counter-memory (Erskine 2023; Hemchand and Murrell 2000). This essay utilizes and privileges the interpretive lens of the oppressed.

Three presuppositions must be made explicit at the onset. First: the essay draws liberally on the Caribbean poetic and artistic impulse to (re)present the sacred. This is in keeping with liberative theologies that have extended their canon to include the cultural fragments by which the oppressed have pursued dignity and self-expression (Hamid 1973), including through music, dance, poetry, and art. Some Caribbean theorists have questioned the adequacy of customary classifications of the religious to the task of interpreting the Caribbean postcolonial experience (Darroch 2009). In particular, poets and artists have broadened our understandings of religion—resisting simple descriptions in terms of structures or systems of belief and reaching for more general understandings concerning how a people find and communicate “ultimate significance in [their] place in the world” (Darroch 2009, p. 5).

Second, the term black is employed to denote people of African heritage, particularly referencing those communities in the Caribbean and in the United States. This use may indeed be reductionistic in the face of the multitudinous and varied experiences that fall under the category of black experience. However, the risk is necessary for identifying convergences in the black experience, for focusing on common legacies of oppression and survival, and for providing a launching point for reflecting on the Black mystical experience.

Finally, Catholic mysticism encompasses a tremendously complex, varied, sophisticated and often enigmatic corpus of experiences, whose summary is well beyond the boundaries of this work. Rather than attempt such a comprehensive treatment, this essay will focus on the mystical experiences of Black Catholics, both personal and communal. This should not detract readers from seeking out broader resonances from the particular experiences of Black people of faith.

The rest of the essay is structured in three distinct sections: First: two images that embody the Caribbean religious imagination will be presented. These are murals from the St Lucian artist the late Sir Dunstan St. Omer, painted in villages churches on the island. St. Omer offers a theological vision interwoven in Caribbean commonplaces and in the struggle for justice and self-determination. This section summarizes his cultural and theological influences and presents his murals for examination and reflection. The next section outlines a few contours from the Christian mystical tradition for context. Finally, three defining dimensions of a uniquely Black Catholic Mysticism are proposed and explicated, hearkening back to St. Omer’s work, but also finding resonances with the work of other Black Catholic artists and authors.

2. Two Murals

Sir Dunstan St. Omer was born on 24 October 1927 on the Caribbean Island of St. Lucia—an independent nation of approximately 180,000 people in the English-speaking Eastern Caribbean—and passed away there in May 2015. By the time of his death, he had received several honors, including a Papal Medal from the Roman Catholic Church, a knighthood from the Queen of England, The St. Lucia Cross—the country’s second highest award—and recognition as a national cultural hero (Cultural Development Foundation of St. Lucia 2022).

His early affinity for art was nurtured by cultural pioneer Harold Simmons, who also mentored St. Omer’s friend (and future Nobel Laureate in literature) Sir Derek Walcott. In an interview with the magazine Caribbean beat, St. Omer reminisced, “what [Harold Simmons] taught us was to paint our own experience. Up until then, the art I had known was European. Harry took the St. Lucian peasant and made him a hero” (Popovic 1995).

Rather than replicating European style and technique, St. Omer began to paint from his own context and experience—encoding nationalistic and postcolonial sensibilities in the dramatic interplay of Caribbean people, landscapes and seascapes. St. Omer saw his art—particularly his many murals painted in churches across the St. Lucian countryside—as expressions of a distinctly Roman Catholic Caribbean faith. He believed that God had created his people in God’s image, and that seeing local representations of the divine was essential for faith formation.

Reflecting on the European religious art popular in Caribbean churches in his day, St. Omer writes, “one of the most important breakthroughs I made was that if [Jesus] Christ cannot be black, he is of no use to us. A white Christ was always used to dominate blacks, and in Jacmel [village], I painted my first black Christ” (Popovic 1995).

2.1. Theological Influences

With these words, St. Omer echoed Caribbean liberative theologies, particularly as developed in the wellspring era of the 1970s to 1990s. Theologians such as Hamid (1973), Davis (1982, 1983, 1990), Erskine (1981), Moseley (1991), Williams (1994) and Gregory (1995) reinterpreted the Christian narrative within the Caribbean context, subverting colonial religious frameworks by articulating a new theological imaginary of God’s presence in the lived experience and historical journey of the Caribbean people. For his part, Idris Hamid—in a 1973 address entitled Theology and Caribbean Development—articulated a vision for a postcolonial Caribbean theology that recovered the truth of God’s presence in Caribbean reality. This truth had been occluded by a colonial brand of Christianity that proved, in many ways, to be irrelevant to the everydayness of island life. In this region, Hamid argued, “God had to do a lot of God’s work underground” (Hamid 1973, p. 123).

Where then did God work if God’s work within the main-line churches was thwarted? God worked in and through the cultural fragments that were there among the oppressed…. God was present more in the canefields than in the cathedrals, more in the baracoons than in the basilicas, more in the ‘protest’ than in the ‘obedience,’ more in [the sorrows of the oppressed and downtrodden] than in the sacraments of the Church.(Hamid 1973, p. 125)

These incendiary words were poignant for the time, and very necessary for occasioning a seismic shift in theological thought away from colonial categories and interpretations. Hamid further added that “the task of theology would be to point out ways in which [Caribbean] creativity and cultural heritage could become a vehicle to receive and express faith. For this is where [humanity] really is and God meets [them]” (Hamid 1973, p. 125). St. Omer would take up this challenge with his artwork, using religious iconography to express a faith that resisted colonial categories and countered narratives of racial and cultural inferiority. In doing this, his work contributed to a broader tradition of subversive Black Catholic expression in the Caribbean and wider Black Atlantic region. (For further examples see Ruiz (2025), Franchina (2025), and Dewulf (2022)).

2.2. The Holy Family Mural

The first mural (Figure 1) is a portrayal of the Holy Family; it adorns the wall to the rear of the altar in a small, village church in Jacmel, St. Lucia.

Figure 1.

Church of the Holy Family, Jacmel, Roseau (Photo taken by author, 14 October 2017).

The mural, replete with shades of blue, brown and green, is St. Omer’s re-imagining of island commonplaces. It features banana trees (the main agricultural crop of the island), a small hut nestled in a verdant clearing, and two iconic volcanic peaks called The Pitons, emblematic of St. Lucia. In the top right corner, a figure blows a conch shell, in keeping with the tradition of welcoming fishermen from a day’s labor. In the top left-hand corner, the village songstress—the chantwèl—leads a festive call-and-response song.

The placement of these characters is deeply symbolic. In St. Omer’s vision, the conch-shell blower and the chantwèl occupy the stead of angels found in traditional religious iconography, serving as heralds of the sacred within the scene. The banana trees and other elements of the natural landscape are similarly elevated, portrayed as manifestations of the divine. The mural also includes a mother and child, instrumentalists, a figure mending a fishing net, a farmer, a couple dancing, and others—each contributing to a vibrant sacred celebration of Caribbean life and place.

St. Omer’s placing of the Madonna and child Jesus (with Eucharist) at the center of the mural is also richly symbolic. From them light and life emanate outwards in concentric circles, seemingly revealing and animating the surrounding characters. The sacred and the profane coalesce in this vision; boundaries are blurred, and lines are crossed. The mural holds the transcendent in tension with the contingency and travail of ordinary Caribbean existence, embodying what philosopher Richard Kearney (2006) has called an epiphany of the everyday.

For island folk, the Holy Family mural remains an indispensable vision of life as counter-narrative to denigrating colonial judgments. In the nineteenth century, novelist and historian James Anthony Froude wrote in his influential text The English in the West Indies, “there has been no saint in the West Indies since Las Casas…There are no people there in the true sense of the word, with a character and purpose of their own” (Froude 1900, p. 347). The Black Caribbean descendent, displaced by slavery from ancestral culture and myth, was deemed a non-entity on the world stage—a deficient derivative of venerable European society. The Jacmel mural’s prophetic imaging of the sacred-profane is the text of a collective riposte to this narrative. It asserts the dignity of a way of life that took shape as a creole hybrid of ancient cultures.

2.3. The La Rose Mural

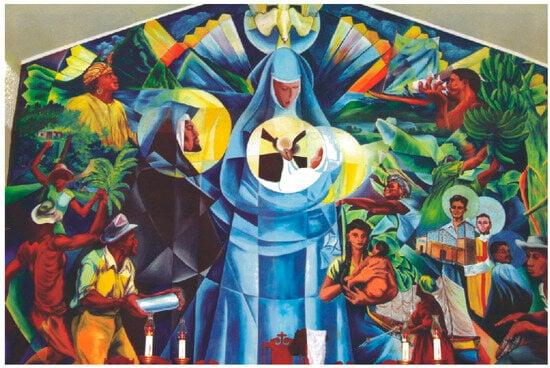

The second mural for consideration (Figure 2) is from the Roman Catholic parish of St. Rose of Lima in the village of Monchy. It features a popular cultural festival on the island, whose symbol is the rose flower.

Figure 2.

Mural in St. Rose of Lima Parish, Monchy, St. Lucia. Photo taken by Embert Charles. Reproduced with permission.

While little is known of its origin, The La Rose flower festival reflects the unique cultural hybridity of St. Lucian society—with African, English and French influences. One highlight is the annual street parade during the month of August. The parade takes the form of mimetic royal escorts. The king and queen, dressed in fineries befitting their estate, form the nucleus of the parade. They are followed by princes and princesses, public servants and professionals (such as nurses and police officers), and others dressed in a variety of colorful traditional outfits. The structure is hierarchical, with members enacting roles that reflect the structure of colonial society (Anthony 1985).

It would be wrong to regard these roles as superficial or transient. Their mimetic performance is also very different from the mimicry of, say, carnival celebrations. For, whereas Caribbean carnival lasts only for the duration of its season, in this floral society one can assume the performative role of a king or queen of the La Rose society for several years. Moreover, the roles do not merely reflect wider (or colonial) social hierarchies but instead confer honor within the internal structure of the floral societies (Anthony 1985). Thus, the farmer who takes on the role of the king, receives equivalent recognition in daily life. In effect, each group constitutes itself as a mimetic microcosm of colonial society. Participation in confraternal practices becomes not only a form of cultural expression, but also a means of social (re)construction and political empowerment. The La Rose festival closely parallels other public festivals and celebrations in the Black Atlantic, such as those described by Fromont (2019), Hidalgo and Valerio (2022) and Valerio (2022), which similarly function as expressions of resistance and empowerment within subaltern communities.

One more feature of consequence: The La Rose festival is distinguished because of its explicitly Roman Catholic sensibilities. Indeed, it may be regarded as a religious festival in secular garb. The society looks to the Peruvian Rose de Lima as its patron saint, veneration of whom is integral to the groups’ identity and ritual life. Feast day celebration includes a pre-dawn Catholic mass followed by a large street parade.

The significance of the Monchy mural is that it places the La Rose society right at the heart of sacred tradition. As in the previous mural, colonial narratives are subverted by grounding a vision of everyday Caribbean life in a sacred story. What makes this more remarkable is that, over the course of its history, the La Rose society has enjoyed an ambiguous reception from the institutional Catholic church, ranging from periods of popularity and fecundity to events of open antagonism, ecclesial suppression and even excommunication. By imagining ordinary people in the stead typically reserved for the saints, St. Omer’s murals serve as subversive text that mediates a radical vision of both faith and society and invites formation of a nuanced sacramental existence.

3. Soundings of a Black Catholic Mysticism

Earlier, this essay described the Black Caribbean experience as being constituted by an ancient wounding. This historical injury, signified in the character Philoctete’s scar and in St. Omer’s murals, gives the Black Catholic mystical experience a unique tenor. More to the point, the Black Catholic mystical tradition witnesses to the God of love who reassembles the fragments of black identity and selfhood from historical injury.

What follows then are three dimensions of a Black Catholic mysticism, gleaned from the witness of Caribbean sacred artists. These are by no means exhaustive; they are meant to be illustrative of the unique contours of a Black Catholic spirituality, and suggestive of areas for further reflection.

The three proposed dimensions of a Black Catholic mysticism are:

- Its inherent sacramentality

- Its responsibility to memory

- Its necessary convergence with the political (the mythical-political)

Before unpacking these three dimensions, it is instructive to contextualize Black Catholic mysticism against the broad corpus of the Christian mystical impulse.

3.1. Christian Mysticism

The Christian practice of mysticism is ancient. According to the Jesuit Harvey Egan (1998, p. 1) the word mysticism does not appear in the Bible and was first associated with Hellenistic mystery religions. The mystical “referred to the cultic or ritual secrets” revealed only to those initiated in these religions. In time, the early Greek fathers of the church attached it to the allegorical interpretation of the Christ event in the Hebrew scriptures, and to the hidden presence of Christ in the sacraments, especially the Eucharist.

Egan proposes that mysticism, as Christian practice, traces its origin to late 5th century theologian Pseudo-Dionysius who “taught a mystical contemplation that permitted a person to know God as the ‘Divine Darkness’ by way of unknowing.” (Egan 1998, p. 2). This understanding of the mystical journey as an inward sojourn towards knowledge of God, or loving (even ecstatic) union with God, would dominate Christian spirituality to this day. Notable exemplars of this way over the centuries include the anonymous author of the fourteenth century manual The Cloud of Unknowing, Julian of Norwich and St. Theresa of Avila, and St. John of the Cross. The latter is perhaps most famously associated with his mapping of the dark night of the soul, the process by which the desires are purified, and ego dismantled as a person faces desolation and emptiness in the inner landscape. More recent figures in the Christian mystical heritage include Thomas Merton, Teilhard de Chardin, Martin Luther King Jr., and Howard Thurman.

A more contemporary understanding of the Christian mystical experience, however, is from the early twentieth Episcopalian mystic Evelyn Underhill (1960) who described it as the art of union with Reality. She teaches that visions, locutions, ecstasies, and raptures, while characteristic of the mystical experience of some, must be seen against this larger understanding. Indeed, a person may never have visions and raptures but that does not preclude them from claiming a mystical experience. This way is available to those who engage the complexity of reality in hope, faith and love; who face reality with “eyes wide open” (so to speak) in faith that the God of love is present.

A more contemporary (and broader) understanding of Christian mysticism therefore is of a type of spiritual awakening that both exults in the presence of God-in-Christ in all things, while engaging in the transformations necessary for the fulness of God’s reign of love. As Carmelite sister Constance FitzGerald reminds the mystical contemplation of Reality is “not a validation of things as they are … but a constant questioning and restlessness that waits for and believes in the coming of a transformed vision of God … capable of creating a new politics and generating new social structures.” (FitzGerald 2021b, p. 102).

It is in this way that the Black Christian experience has represented a unique genius within the Christian mystical tradition. Martin Luther King Jr. and Howard Thurman confronted conceptions of the mystical journey as solely inward and aimed towards achieving self-purification and union with God, adding that it must be lived in social activism. The experience of mysticism and contemplative prayer is not the prerogative of a select few who are blessed with a kind of second sight. Rather, it is the vocational calling of all people of faith. Moreover, as Barbara Holmes (2017) reminds, Black mysticism transcends the limit of personal piety. It resists individualism to emphasize the communal elements to divine communion. As St. Omer’s murals witnessed, God is present in the midst of community and is to be contemplated as such.

3.2. Three Dimensions of a Black Catholic Mysticism

Three dimensions of a specifically Black Catholic Mysticism may be added to this legacy. They illustrate areas of convergence with the broader Christian and Black Christian traditions (for instance in the latter’s privileging of social activism), while also revealing distinctive frequencies. They represent means by which Black Catholics have pursued wholeness and healing amidst the woundedness of life—the hybridity of Philoctete’s scar. Indeed, in what follows, each dimension will be presented over and against a distinctive wound of Black existence—that of desacralization, ambiguous memory, and alienation.

Despite the ever-expanding volume of Black Catholic Theological scholarship (both in Caribbean theology and in the American church), precious little has been written under the specific title of Black Catholic mysticism. More voices are needed to engage this important legacy. However, it is also true that there is a wealth of wisdom to be learned from those whose expressions and reflections on Black spirituality and worship, like the art of Dunstan St. Omer, speak clearly to the mystical experience of faith. As such, in explicating the three proposed dimensions of a Black Catholic mystical impulse, the sacred poetry of St. Lucian John Robert Lee will also be drawn upon, as well as theologians Kortright Davis, M. Shawn Copeland, Diana Hayes, and C. Vanessa White, whose writings resonate with contemplation of the transforming presence of God in the midst of daily life.

- 1.

- Its Inherent Sacramentality

An integral part of St. Omer’s art as discussed above was its witness to the presence of the divine in the midst of the daily life of local denizens. This point resonates with the understandings from other artists. St. Lucian poet John Robert Lee (2017, p. 29), for instance, has gifted us with the following verse:

Come, kneelscratch, scrapedig herewith your handsbeneath this dry groundis fresh water

Lee beckons readers to commit to experiencing the depth dimensions of black existence; to find life even within the barrenness and woundedness of that experience.

One expression of such woundedness is in what could be called the desacralizing of the ordinary. African cosmologies held by Caribbean slaves were inherently sacramental; suffused with the belief that we share community with ancestral spirits and deities, and that creation is the arena for these relationships (Stewart 2004). Indeed, this cosmology is still present in the folklore of the island of St. Lucia. Caribbean woundedness lies in the illusion that—in the daily struggles of life, the interminable busyness, the work of overcoming the challenges of the day—we are alone.

Slave colonial society handed over a legacy of what Barbadian theologian Kortright Davis (1990) called the absentee God of Europe, whose representation in the colonial church had no meaning for the Black Caribbean native. Instead, Black Catholic mystical experience, (re)presented in St. Omer’s art, breaks the illusion that we are alone in the barrenness of life’s humdrum. John Robert Lee further captures this sacramental vision in his poem Prodigal (Lee 2017, p. 32):

… Above Soufriere descending earlymorning heals the night in sulphur bathscovers over all in fine rain and light,and among the mists, below the road’s steep edge,see Christ, the charcoal burner,perfection raking wood and leavesspirit with bare feet of earth.His sweet blue smoke climbs steady up to heaven.

The Black Catholic mystic is a witness to Emmanuel God-with-us; that God’s loving and lifegiving presence is to be found here, right here—Christ, the peasant charcoal burner! The mystical summons is to come, kneel, to dig just here, for beneath this dry ground of daily life is fresh water.

St. Omer’s work commends us to a sacramental vision that confronts the illusion of an absent God. It is one of divine love at the center of black life; love and light that mothers, illuminates and vivifies the joys, celebrations, travail, and sufferings occasioned by historical injury. This vision is a reminder of what has been at the heart of the Black mystical experience:

- That God has, is and always will be faithful. God is the one who delivered God’s people through the cauldron of the middle passage, through the evils of slavery, into God’s light of subjectivity self-realization. And it is this God, who has loved us into ourselves, who moves with irresistible power. As the popular Caribbean hymn has proclaimed:The right hand is writing in our landWriting with power and with love,Our conflicts and our fears,Our triumphs and our tearsAre recorded by the right hand of GodThe right hand of God is healing in our land,Healing broken bodies, minds and souls,So wondrous is its touchWith love that means so muchWhen we’re healed by the right hand of God.

- That Black Catholic Mysticism resists easy demarcation between the sacred and the secular. It admits to pluriformity in the ways that a wounded people may voice and express deepest meanings and evokes faith and hope in divine assistance. As the 10 Black Catholic Bishops of the United States stated in 1984 “every place is a place for prayer because God’s presence is heard and felt in every place. Black spirituality senses the awe of God’s transcendence and the vital intimacy of his closeness. God’s power breaks into the ‘sin-sick world’ of everyday.” (What We Have Seen and Heard 1984, p. 8).

- That Black Catholic Mysticism spotlights the sacramentality of embodied existence. As C. Vanessa White notes, “black people use their entire bodies to express their love of God; their joy is expressed in movement, dance, song, art, sensation, thanksgiving, and exultation.” (White 2021, p. 122). The dancing body, the sensual body, the body at play, but also the suffering body—these can no longer be cast aside in the din of history. The presence of God is summons and challenge to remember the body of Christ broken and given at the table and in history and society.

- 2.

- Its Responsibility to Memory

Another dimension of Black Catholic mysticism is its responsibility to memory. The sacramental vision is consoling, but that by no means dulls its challenge. It is challenged and wounded by what the Carmelite theologian Constance FitzGerald (2021a, p. 430) called the ambiguities of memory.

Black memory is complicated! It bears the pain of history and the survival of history. It summons to mind and heart the times when God has delivered us from trials, as well as times of crying out in anguish to a seemingly absent God. Black faith wrestles with the dark night of memory. It brings the joy, affirmation, and warmth of remembered family and community. Then it raises the specter of past trauma, of lost ones, forced separations and other injuries. It threatens revenge in the face of violence but also stirs up courage to resist and the Black legacy of overcoming and non-violent resistance. Then, some memories are just too painful to be stirred up.

In the Caribbean, colonial memory is locked in the land, in its architecture, buildings, and in the soil which bore the blood, sweat and toil of generations. As Martin Carter (1977, p. 15) writes in the poem Listening to the land:

I bent downListening to the landAnd all I heard was tongueless whisperingAs if some buried slave wanted to speak again

In her Black Catholic Studies Reader essay entitled We’ve Come This Far by Faith, Diana Hayes describes succinctly how Black faith is born of the ambiguous memory “of struggle, of perseverance, of hope, of faith, and of survival against all odds and all obstacles placed in our path” (Hayes 2021, p. 100). She importantly adds,

as a holistic people … the pain does not outweigh the hope, the struggle does not diminish the faith. We rejoice in the intertwining, rather than the separation, of the many strands of our life […] We therefore cherish our memories, painful though they may often be, for they serve as subversive memories, memories that turn all of reality upside-down, as Jesus Christ did in his life, death, and resurrection.(pp. 100–1)

Black Catholic mysticism privileges subversive memory as an essential category: memories that turn “all of reality upside down;” memories that counteract narratives of dehumanization and hearken to the dignity of Black life (Hayes 2021, p. 95).

This mystical impulse summons us to truth; it remembers the broken bodies of society and history and locates this in the dangerous memory of the broken body of Jesus. It summons us to lament, which is that crying out to God that seeks to break the impasse of existential angst (Massingale 2010). At the same time, Black Catholic mysticism summons us to hope: to the hope-full memory of Jesus’ resurrection and to the promise of God’s future that animates our work for earthly redemption for all victims of history and society.

- 3.

- Its Necessary Convergence with the Political (Mystical-Political)

Lastly, the Black Catholic mystical vocation necessarily converges on the political. The specific wound addressed here is that of alienation of black being from authentic embodiment, from identity, from safety, and from basic human rights (Davis 1990). The mystic confronts injustice, admitting that the mystical journey is not solely inward, and that the journey into the dark night of the soul is also a journey into the darkness and moral impasse that too often postpones justice today (FitzGerald 2021b). The demons to be overcome by Black folk are not only internal!

Writing about what can only be described as the mystical quality of Black spirituality, C. Vanessa White writes, “the journey to a closer union with God brings not only personal freedom and authenticity but also invokes a community striving for liberation from all forms of oppression” (White 2021, p. 124). This is mystical-political discipleship that recognizes and alleviates hungers—whether for food or truth or justice—as a loving response to the God of love who calls us to transformation.

M. Shawn Copeland (2010) has rightly argued that Catholic mystical-political discipleship is essentially Eucharistic. It is lived through solidarity with the injured bodies of history. In the Eucharist, Black Catholic faithful present their lives, bodies and memories to the table of the Lord. They evoke and are renewed in the memory of the broken and resurrected body of Jesus. Eucharist is indeed the ritual memorializing and enactment of God’s radical solidarity with the embodied life experience of those at table, and with all broken bodies of history and society (Copeland 2010).

If a Black Catholic mysticism is Eucharistic, then it is inherently communal (White 2021). Indeed, it is as much communal as it is personal. Again, it resists uniform identification with the interior journey, admitting to a communal solidarity at the heart of the mysticism. Its ultimate horizon is the communion of saints, wherein black folk, both alive and with God, unite in the common experience of wounding and overcoming.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anthony, Patrick A. B. 1985. The Flower Festivals of St. Lucia. Culture and Society Series. No. 1. St. Lucia: Folk Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Augier, Fitzroy Richard, and Shirley C. Gordon. 1962. Sources of West Indian History. London: Longmans. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Martin. 1977. Poems of Succession. London: New Beacon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, M. Shawn. 2010. Enfleshing Freedom: Body, Race, and Being. Innovations: African American Religious Thought. Edited by Anthony B. Pinn and Katie G. Cannon. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cultural Development Foundation of St. Lucia. 2022. Gwan Gwèk Kilté: Celebrating Our People—Sir Dunstan St. Omer, SLC. Available online: https://www.cdfstlucia.org/gwan-gwek-kilte-celebrating-our-people-sir-dunstan-st-omer-slc (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Darroch, Fiona. 2009. Memory and Myth: Postcolonial Religion in Contemporary Guyanese Fiction and Poetry. Amsterdam: Rodopi, vol. 103. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Kortright. 1982. Mission for Caribbean Change: Caribbean Development as Theological Enterprise. Frankfurt am Main and Bern: Verlag Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Kortright. 1983. Cross and Crown in Barbados: Caribbean Political Religion in the Late 19th Century. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Kortright. 1990. Emancipation Still Comin’: Explorations in Caribbean Emancipatory Theology. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Dewulf, Jeroen. 2022. Afro-Atlantic Catholics: America’s First Black Christians. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, Harvey D. 1998. Christian Mysticism: The Future of a Tradition. Eugene: Wipf and Stock. [Google Scholar]

- Erskine, Noel Leo. 1981. Decolonizing Theology: A Caribbean Perspective. New York: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Erskine, Noel Leo. 2023. Black Theology and Black Faith. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald, Constance. 2021a. From Impasse to Prophetic Hope: Crisis of Memory. In Desire, Darkness, and Hope: Theology in a Time of Impasse: Engaging the Thought of Constance Fitzgerald, Ocd. Edited by Laurie Cassidy and M. Shawn Copeland. Collegeville: Liturgical Press Academic. [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald, Constance. 2021b. Impasse and Dark Night. In Desire, Darkness, and Hope: Theology in a Time of Impasse: Engaging the Thought of Constance Fitzgerald, Ocd. Edited by Laurie Cassidy and M. Shawn Copeland. Collegeville: Liturgical Press Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Franchina, Miriam. 2025. ‘New to Freedom but by No Means New to Faith’: Visions of an Abolitionist Black Catholic Church in Early Haiti (1808–1825). Slavery & Abolition 46: 124–48. [Google Scholar]

- Fromont, Cécile, ed. 2019. Afro-Catholic Festivals in the Americas: Performance, Representation, and the Making of Black Atlantic Tradition. Edited by Sylvester A. Johnson and Edward E. Curtis IV. Africana Religions. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Froude, James Anthony. 1900. The English in the West Indies: Or, the Bow of Ulysses. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, Howard, ed. 1995. Caribbean Theology: Preparing for the Challenges Ahead. Kingston: Canoe Press, University of the West Indies. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, Idris. 1973. Theology and Caribbean Development. In With Eyes Wide Open: A Collection of Papers by Caribbean Scholars on Caribbean Christian Concerns. Edited by David I. Mitchell. Trinidad: CADEC, pp. 120–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Diana L. 2021. We’ve Come This Far by Faith: Black Catholics and Their Church. In Black Catholic Studies Reader: History and Theology. Edited by David J. Endres. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hemchand, Gossai, and Nathaniel Samuel Murrell, eds. 2000. Religion, Culture, and Tradition in the Caribbean, 1st ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, Javiera Jaque, and Miguel A. Valerio, eds. 2022. Indigenous and Black Confraternities in Colonial Latin America: Negotiating Status Through Religious Practices. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, Barbara. 2017. Joy Unspeakable: Contemplative Practices of the Black Church, 2nd ed. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, Willie James. 2010. The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Walter. 1999. Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney, Richard. 2006. Epiphanies of the Everyday: Toward a Micro-Eschatology. In After God: Richard Kearney and the Religious Turn in Continental Philosophy. Edited by John Panteleimon Manoussakis. New York: Fordham University Press, pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, John Robert. 2017. Collected Poems 1975–2015. Leeds: Peepal Tree Press. [Google Scholar]

- Massingale, Bryan N. 2010. Racial Justice and the Catholic Church. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mintz, Sidney Wilfred. 1974. Caribbean Transformations. Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Moseley, Romney M. 1991. Becoming a Self Before God: Critical Transformations. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Popovic, Caroline. 1995. Hail Mary: The Art of Dunstan St. Omer. Caribbean Beat Spring, No. 13. Available online: https://www.caribbean-beat.com/issue-13/hail-mary-art-dunstan-st-omer (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Ramazani, Jahan. 1997. The Wound of History: Walcott’s Omeros and the Postcolonial Poetics of Affliction. Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 112: 405–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, Jesús G. 2025. Freedom, Faith & Sovereignty: The 1796 Boca Nigua Revolt as an Afro-Catholic Royalist Rebellion. Slavery & Abolition 46: 100–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, Dianne M. 2004. Three Eyes for the Journey: African Dimensions of the Jamaican Religious Experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Underhill, Evelyn. 1960. Practical Mysticism: A Little Book for Normal People. New York: Dutton. [Google Scholar]

- Valerio, Miguel A. 2022. Sovereign Joy: Afro-Mexican Kings and Queens, 1539–1640. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walcott, Derek. 1992. Omeros, first paperback ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- What We Have Seen and Heard: A Pastoral Letter from the Black Bishops of the United States. 1984. Cincinnati: St. Anthony Messenger Press. Available online: https://www.usccb.org/resources/what-we-have-seen-and-heard.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- White, C. Vanessa. 2021. “Gonna Move When the Spirit Say Move”: A Black Spirituality of Resistance and Resilience. In Black Catholic Studies Reader: History and Theology. Edited by David J. Endres. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Lewin L. 1994. Caribbean Theology. Research in Religion and Family Black Perspectives. Edited by Noel Leo Erskine. New York: Peter Lang, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).