Abstract

This article provides the first systematic examination of Dazang shengjiao jieti, a catalogue of Buddhist scriptures compiled by the prominent Qing dynasty scholar-official Wang Chang and the earliest Buddhist catalogue by a literatus of the Qing period, to explore how Confucian literati approached Buddhist canonical materials. The extant version is a partial manuscript copy of only six surviving juan, excerpting prefaces to scriptures and biographies of translators, with over one hundred annotations by Wang. Through detailed textual analysis of the book, this study identifies three distinctive methodological features in Wang’s cataloguing work: systematic comparison of case numbers, character codes, and volume sequences across the Ming and Qing canonical editions; integration of official historical sources to trace textual transmission; and incorporation of Buddhist stone inscriptions into canonical lineage studies. Faced with the vast flood of knowledge, Wang Chang developed a mode of textual organization that integrated Confucian and Buddhist perspectives based on the Confucian scholarly tradition, reflecting the reading practices and intellectual preferences of contemporary scholar-officials. By examining these details, this research reveals that Wang’s evidential approach differed fundamentally from monastic cataloguing traditions and, by maintaining a Confucian scholarly foundation, significantly improved the accessibility and practical value of Buddhist canonical materials for literati readers.

1. Introduction

Scholarship on Chinese Buddhist canons has centred primarily on compilation histories, textual lineages, and institutional contexts. Although scholars have thoroughly documented canonical production and monastic usage, the question of who actually read and studied these texts beyond religious communities has received little attention. As Lewis Lancaster () has observed, understanding the scope of the “audience” for Buddhist canonical materials is essential for grasping their broader cultural impact. Within this scholarly context, the Qing period presents a particularly complex case. The dynasty inherited multiple woodblock canonical editions from previous periods while simultaneously producing the Qing Canon (Qingzang 清藏, or Qianlong dazangjing 乾隆大藏經, or Longzang 龍藏), the final imperially sponsored Buddhist canon in traditional Chinese history. This accumulation of canonical resources created an unprecedented wealth of reading materials, attracting diverse groups of readers beyond the monastic community. Scholar-officials formed one of the key groups with access to Buddhist canonical materials during the Qing period, but their reading practices and interpretive methods remain poorly understood. Examining how educated officials engaged with Buddhist canons helps us understand the wider circulation of Buddhist materials among intellectuals and their incorporation into Confucian scholarly traditions. Such studies are vital for understanding how Buddhist scriptures served both as spiritual resources and as objects of scholarly inquiry in eighteenth-century China.

While traditional scholarship has characterized Qing Buddhism as declining after the late Ming revival, recent social historical research reveals that literati engagement with Buddhism remained vibrant throughout the period. Phenomena such as “escape to Chan (taochan 逃禪)” among Ming loyalists and the rise in lay Buddhism during the Qianlong era demonstrate continued scholar-official involvement in Buddhist activities. However, this typically manifested through personal practice and temple patronage rather than systematic textual scholarship. This pattern of literati engagement represents a manifestation of Buddhist vitality in eighteenth-century China, where religious texts increasingly served as objects of scholarly investigation alongside their traditional spiritual functions. Understanding how literati engaged with Buddhist canonical materials through systematic scholarly methods is, therefore, crucial for several interconnected reasons. First, it reveals the specific mechanisms through which Buddhist and Confucian knowledge traditions interacted, moving beyond general discussions of syncretism to examine concrete practices of intellectual integration. Second, such research contributes to reconstructing Qing intellectual history by illuminating how evidential scholarship expanded beyond classical texts to encompass religious materials. Third, examining literati approaches to Buddhist texts provides insights into how scholar-officials redefined their intellectual identities and religious engagement within Confucian frameworks. Finally, this line of inquiry elucidates the broader processes by which the religious literature was transformed into academic resources, offering a model for understanding cross-cultural knowledge appropriation in late imperial China.

Wang Chang 王昶 (1725–1806) was a prominent scholar-official during the Qianlong 乾隆 (1736–1795) and Jiaqing 嘉慶 (1796–1820) eras of the Qing 清 dynasty (1644–1911). He pursued a wide range of scholarly interests. Renowned in his youth for his poetry, he later studied under Hui Dong 惠棟 (1697–1758), who was a leading figure in the evidential scholarship movement of the Qing dynasty, and followed the philological method of Han Learning (Hanxue 漢學) in his classical studies, represented by his rigorous textual criticism. In his readings of Confucian classics such as the Book of Songs 詩經 and the Book of Rites 禮記, he followed the commentarial traditions established during the Han dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE). When it came to doctrines concerning human nature and the Way, he held the Neo-Confucian philosopher Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200) in the highest esteem, while also drawing upon later thinkers such as Xue Xuan 薛瑄 (1389–1464) and Wang Yangming 王陽明 (1472–1528) (). These diverse influences reflect Wang’s broad intellectual outlook. Beyond his official duties, Wang Chang devoted himself to the collection of stone inscriptions and rubbings and composed the monumental epigraphic work, Jinshi cuibian 金石萃編 in his later years.

He was also deeply versed in Buddhist learning. Throughout his life, his official career coexisted with his study of Buddhism. Reading sutras, visiting renowned temples, and contemplating Buddhist teachings had long become part of his daily life. Wang Chang himself recognized his distinctive position among the literati of his time in terms of Buddhist learning. In his own assessment, he identified himself as one of only four scholar-officials in the entire empire who possessed a genuine understanding of Buddhist doctrine, noting that most other literati merely appropriated superficial Buddhist terminology without grasping the fundamental principles of Buddhist philosophy and practice (). This self-evaluation underscores the exceptional rarity of serious Buddhist scholarship among Confucian literati and highlights Wang Chang’s unique position as both a committed Confucian scholar and a serious student of Buddhism. Scholars have long recognized the distinctiveness of his religious interests among the literati class. Wu Yunqing 武雲清 (), drawing on Wang Chang’s biography and literary works, has explored the close connections between his Chan practice, scriptural reading, and poetic writing, and analyzed how Wang maintained a mindset of “finding retreat through official duty” (yi li wei yin 以吏爲隱) amid the vicissitudes of political life, grounded in his moral cultivation and philosophy of conduct. Yin Zongyun 尹宗雲 (), for his part, has examined Wang’s correspondence with senior monks at Yuanjin Monastery 圓津禪院, along with his diaries and writings, to provide a detailed account of his Buddhist learning and religious practices. He demonstrates that Wang not only maintained long-standing connections with Buddhist communities and studied Buddhist scriptures in depth, but also actively engaged in the compilation, editing, and restoration of Buddhist texts.

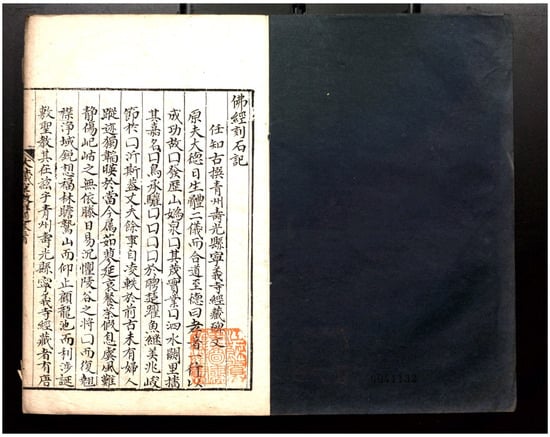

In contrast to the monastic lifestyle centred on cultivation and practice, Wang Chang’s religious activities bore a distinctly literati character. His Buddhist practice was not limited to interactions with monks and Buddhist scholarly discussions but also focused intently on the reading and editorial organization of Buddhist scriptures, and devoted considerable effort to it. Wang Chang’s approach was grounded in the evidential scholarship (kaozhengxue 考證學) characteristic of his era, which emphasized empirical verification and historical contextualization over doctrinal interpretation, distinguishing his work from traditional Buddhist exegetical practices. Dazang shengjiao jieti 大藏聖教解題 (Annotated Bibliography of the Sacred Teachings in the Buddhist Canon, hereafter abbreviated as Jieti) is a bibliographic catalogue of Buddhist scriptures compiled by Wang Chang based on the Qing Canon. The extant version of this work is a six-juan 卷 incomplete manuscript copy, with material features such as blank frame borders (baikou 白口, referring to the absence of inked lines at the top and bottom of the folio centre) and a single black fish-tail notch (yuwei 魚尾, a small wedge-shaped mark engraved near the top of the folio centre to guide the folding of the printed sheet). The page layout follows a standard format, consisting of ten lines per half folio and twenty-one characters per full line (Figure 1). It is preserved in the Nanjing Library 南京圖書館. Due to its fragmentary content and the fact that it survives as a single copy, the Jieti has seen little scholarly use. Previous references to this work have been scant and often contain errors regarding the title or authorship.1 The Jieti represents not only the most systematic and concentrated outcome of Wang Chang’s long-term engagement with Buddhist scripture reading and editorial work, but also the first Buddhist catalogue compiled by the scholar-official community during the Qing dynasty in extant sources. Yet its nature, compilation background, and transmission history require further clarification.

Figure 1.

Copy of the Dazang Shengjiao Jieti, the prefatory section (juanshou 卷首).

Therefore, I centre this study on Wang Chang’s Dazang shengjiao jieti, drawing on sources such as private book catalogues and epigraphic annotations to examine his reading, compilation, and organization of Buddhist canons. This research addresses a significant gap in understanding how Confucian evidential scholarship was systematically applied to Buddhist textual studies. Wang’s transplantation of rigorous philological methods, including textual collation, cross-referential verification, and historical contextualization, into Buddhist canonical research represents a methodological innovation that provided literati with new approaches to locating, reading, and utilizing Buddhist canonical materials. I demonstrate that his approach reflects a deep orientation toward practical learning and reveals how a significant literatus actively engaged with Buddhist canonical materials in eighteenth-century China. The article unfolds in three parts. The first part outlines the structure, compilation history, and transmission of the Jieti, showing how Wang conceived the project during his official editorial work related to the Qing Canon and resumed it in his later years. The second part investigates his methods of classification and textual selection, with particular attention to his treatment of different canons compiled during the Ming and Qing dynasties. The third part situates Wang’s work within Qing intellectual contexts, exploring how his engagement with canons embodies both philological rigour and cross-traditional inquiry. This analysis, I hope, sheds light on broader patterns of literati scholarship and how Buddhist texts were integrated into Confucian scholarly frameworks.

2. The Nature, Compilation, and Transmission of the Dazang Shengjiao Jieti

Lai Xinxia 來新夏 was among the earliest scholars to take note of this catalogue. In his Qingdai mulu tiyao 清代目録提要 (Annotated Bibliographies of Catalogues in the Qing Dynasty), he provided a summary outlining the work’s content, format, and key features. As he mentions, the extant portions of the work include juan 1, 9, and 20 through 23. Juan 1 contains sutras from the Prajñāpāramitā section of the Mahayana scriptures in the Qing Canon; juan 9 includes individually translated sutras from the Āgama section of the scriptures of the lesser vehicle; juan 20 to 23 feature the Chinese indigenous writings. Additionally, six stele inscriptions are appended to the beginning of the work, including “Fojing keshi ji 佛經刻石記” (Stone Inscription of Buddhist Sutras) and “Nanzang kejing beiji 南藏刻經碑記” (Stele Records on the engraving of Nanzang). The Jieti is a representative example of the compilation style of bibliographic catalogues, recording the titles, volume (juan 卷) and case (zhi 帙) numbers, and authors of the texts, and primarily compiling the prefaces of the scriptures. It also notes the storage location of each listed Buddhist scripture using a shelving system based on the Qianziwen 千字文 (Thousand Character Classic). Each entry specifies the character code as classified in the Qing Canon (e.g., from character X to character Y, dazang mou zi zhi mou zi hao 大藏某字至某字號) and the case number it occupies (fan mou han 凡某函) (). The term “compilation style” (jilu ti 輯録體) refers to a bibliographic format that extensively compiles materials related to given works to illuminate their content and offer commentary (). Lai Xinxia regarded the Jieti as “compilation style” based on the method of Jieti’s compilation, and it proved to be remarkably accurate. In fact, when examined from the perspective of its intended function, the Jieti may also be regarded as a reading-oriented catalogue (duzang mulu 讀藏目録), following the organizational structure of the sections, volumes, and case numbers of the Qing Canon. By citing scriptural prefaces and monastic biographies, the Jieti aimed to guide not only Buddhist practitioners but also literati readers in approaching and understanding Buddhist textual traditions (; ).

Evidence suggests that Wang Chang began formulating the conceptual framework for the Jieti around the thirtieth year of the Qianlong era (1765), as indicated by his inclusion of Zhi Sheng’s 智昇 (699–740) Kaiyuan shijiao lu lüechu 開元釋教録略出 (Digest of Catalogue of Buddhist Works Compiled During the Kaiyuan Period) in juan 22 of the Jieti. This particular work was expurgated by imperial decree in 1769, implying that Wang had already started collecting and composing annotations for the Jieti before that date. An imperial edict from 1773 records Emperor Qianlong’s (r. 1736–1796) order to eliminate texts such as the Digest of Catalogue of Buddhist Works Compiled During the Kaiyuan Period and other writings from Xuzang 續藏 (the supplement of the Qing Canon), following prior instructions from Emperor Yongzheng 雍正 (r. 1723–1735) regarding the removal of miscellaneous and unorthodox content ().2 Two key episodes in Wang Chang’s career appear to have played a formative role in shaping his conception and eventual compilation of the Jieti. The first occurred in 1764, when he was appointed a supervising editor (Shouzhangguan 收掌官) at the Imperial Bureau for Military Histories (Fanglüeguan 方略館). Acting under the direction of Liu Tongxun 劉統勛 (1700–1773), he took part in the revision of the Qing Canon.3 Another formative experience came in 1767, when Wang Chang served concurrently in the Bureau for the Collation of Scriptures and Mantras (Jingzhouguan 經咒館). Entrusted by Zhu Yun 朱筠 (1729–1781), he participated in matters concerning the translation and storage of Buddhist scriptures (; ). These two events played a pivotal role in motivating Wang’s compilation of the Jieti. It was during this period of textual engagement that Wang conceived the Jieti and began drafting collation notes and critical annotations, which would eventually constitute the backbone of the work.

The Jieti was ultimately completed in Wang Chang’s later years. In the early Jiaqing era, having retired from office and suffering from worsening eye problems, Wang enlisted the assistance of several literati in compiling and editing his writings. In the spring of 1802, he invited Zhu Wenzao 朱文藻 (1735–1806) to the Sanmao Fishing Retreat (Sanmaoyuzhuang 三泖漁莊). Zhu Wenzao collaborated with Wang Chang in the collation and editing of several major works, including the most notable epigraphic work Jinshi Cuibian. The compilation of the Jieti was probably undertaken during the same period.4 Supporting evidence can be found in the prefatory portion of the Jieti, where a stele inscription titled “Qingzhou shouguangxian ningyisi jingzang beiwen 青州壽光縣寧義寺經藏碑文” (Inscription for the Buddhist Canon at Ningyi Monastery in Shouguang County of Qing Province) by Ren Zhigu 任知古 is followed by an annotation authored by Zhu Wenzao. In this annotation, Zhu provided detailed examinations of the historical figures, places, and Buddhist temples mentioned in the inscription, revealing key aspects of his editorial engagement with the text. As he noted: “The Ming Jiajing Shandong tongzhi records that the temple was [established] in the first year of Zhenguan, but the new Zhi does not include this inscription, making it impossible to verify its lacunae. 明嘉靖《山東通志》貞觀元年[建]寺,新《志》不載此碑,無從校其缺泐。” Using local gazetteers to verify inscriptions was a common research method in Qing dynasty epigraphical studies.

In the approximately fifty years following the compilation of the Jieti, complete copies of the work remained in circulation. One such copy was kept in Qingyin’ge 清吟閣, the private book repository of Qu Shiying 瞿世瑛 (fl. 1820–1890), a noted Qing-dynasty bibliophile based in Hangzhou 杭州. At the beginning of the Qingyin’ge shumu 清吟閣書目 (Catalogue of the Pure Chanting Pavilion), a complete sixteen-juan manuscript copy of Dazang shengjiao jieti is recorded, with authorship mistakenly attributed to Zhu Wenzao. The Qingyin’ge shumu includes an annotation under the table of contents stating, “compiled and edited in the author’s own hand in the autumn of the sixth year of the Xianfeng reign (1856) 咸豐丙辰秋手訂” (), indicating that a complete copy of the Jieti was still extant at that time. The Qingyin’ge shumu also lists more than twenty other works compiled, edited, or authored by Zhu Wenzao (), suggesting that the Jieti may have entered the Qingyin’ge along with Zhu’s other writings.

The extant partial manuscript copy of the Jieti bears the seal of the “Jiangsu Provincial First Library” (Jiangsu shengli diyi tushuguan 江蘇省立第一圖書館) on each fascicle (ce 册), offering tangible evidence of its archival history. This institution was a predecessor of the present-day Nanjing Library. Between 1919 and 1927, the library underwent several name changes, from the Jiangnan Library (Jiangnan tushuguan 江南圖書館) to the Jiangsu Provincial First Library, and eventually to the Jiangsu Provincial National Studies Library (Jiangsu shengli guoxue tushuguan 江蘇省立國學圖書館), its most commonly used name thereafter. According to the Jiangsu shengli guoxue tushuguan tushu zongmu 江蘇省立國學圖書館圖書總目 (the General Catalogue of the Jiangsu Provincial National Studies Library), the library holds a three-fascicle manuscript copy titled Dazang shengjiao tijie大藏聖教題解, authored by Wang Chang of Qingpu 青浦 in the Qing dynasty, with only six juan extant (). This suggests that the partial manuscript copy was accessioned into the Jiangsu Provincial First Library between 1919 and 1927 and has been preserved there ever since.5

3. Wang Chang’s Methods and Characteristics in Editing the Buddhist Catalogue

In addition to accessing the Qing Canon through his official duties, Wang Chang also built up a private collection of Buddhist sutras. According to the Shunan shuku mulu chubian 塾南書庫目録初編 (Preliminary Catalogue of the Shunan Library), his holdings included nearly fifty sutras, such as the Brahmajāla Sūtra, the Saṃdhinirmocana sūtra, the Lotus Sūtra, and two variant translations of the Śūraṃgama Sūtra.6 For a scholar-official of his time, this represented a remarkably rich collection, suggesting that his study of Buddhist texts was not incidental, but part of a systematic and sustained intellectual pursuit. Wang Chang consistently applied evidential approaches to examine the transmission and structural formation of canonical texts, focusing on editions, catalogues, collation, and practices of collection. By compiling catalogues, collating textual versions, and composing annotations, Wang Chang formulated a working procedure for the study of Buddhist texts. The following section analyzes three key aspects of Wang’s practice. These three methodological features include the systematic comparison of canonical editions, the integration of dynastic historical sources, and the incorporation of epigraphic materials. Each approach represents a significant departure from traditional monastic cataloguing practices and collectively demonstrates how Wang adapted Confucian evidential scholarship to Buddhist textual studies. By analyzing these distinctive methodological features, this study demonstrates that Wang Chang’s approach differed fundamentally from established Buddhist cataloguing traditions and provided scholar-officials with more efficient means to access and utilize canonical materials.

3.1. Collating Ming and Qing Canons

The first of these methodological features concerns Wang Chang’s systematic approach to textual comparison. The extant manuscript copy of the Jieti records a total of 225 entries for Buddhist texts, 105 of which are accompanied by Wang Chang’s annotations. These annotations indicate that one of Wang Chang’s most important and distinctive undertakings was the comparative analysis and verification of canonical editions from the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing dynasties. Through this process of collation, Wang Chang made at least three achievements.

Wang Chang’s first achievement concerns the textual positioning of scriptures in the Ming and Qing canons. In the Jieti, most entry records the Thousand-Character case number in the Qing Canon, and the accompanying annotation specifies its corresponding placement in Mingzang 明藏. For example, the Ji zhi guo jing 寂志果經 (Śrāmaṇyaphala sūtra) is listed under the second case of number shan 善 in the Qing Canon, while the annotation notes that in Mingzang, it is catalogued under the character huo 禍 (). Such notations appear frequently throughout the Jieti. They not only facilitate readers in locating each scripture’s position within the Ming and Qing canons but also reflect Wang Chang’s effort to explore textual relationships among different Buddhist canons produced in the Ming and Qing dynasties. It is worth noting that the term “Mingzang” in Wang Chang’s annotations primarily refers to Yongle Nanzang 永樂南藏 (Yongle Southern Canon),7 compiled under imperial commission in Nanjing during the Ming dynasty, though in some cases it also indicates reference to Yongle Beizang 永樂北藏 (Yongle Northern Canon).8 By nature, the two Buddhist canons were imperially commissioned projects of the Ming dynasty, distributed to major monasteries across the empire. In comparison, the Yongle Northern Canon, noted for its superior woodblock carving, served as the textual foundation for the Qing Canon and shares substantial overlaps with it in the main part of the canon (Zhengzang 正藏). As an official serving at the Imperial Bureau for Military Histories, Wang Chang was presumably well aware of this basic fact. His editorial decision during the collation process was likely informed by examinations of both the structural features and the relative accessibility of different editions. There is evidence to suggest that the Yongle Southern Canon was more readily available than its Northern counterpart. In Nanjing, many commercial print shops were involved in the printing and binding of the southern edition.9 During the early Qing period, officials across various regions also requested the printing of the Southern Canon due to local administrative needs ().

His second achievement concerns the timing of a work’s inclusion in the Buddhist canonical system. In his comparison of the Ming and Qing canons, Wang Chang also focused on when certain texts were incorporated into the Buddhist canonical system, particularly those that were newly included during the Yongzheng era. For instance, the Da fangguang fo huayan jing puxian xingyuan pin biexing shuchao huiben 大方廣佛華嚴經普賢行願品别行疏鈔會本 (Collected Commentaries on the Practices and the Vows of Samantabhadra Bodhisattva from the Avataṃsaka Sūtra) is absent from both the Southern and Northern Ming editions. Wang’s annotation thus identifies its inclusion in the Buddhist canonical system as occurring in the thirteenth year of the Yongzheng era (1735) (), which marked the beginning of the compilation of the Qing Canon.

His third achievement focuses on the division and combination of textual volumes. In his comparison of the Ming and Qing canons, Wang Chang’s analysis went beyond matching the corresponding case numbers based on the Thousand Character Classic. He also examined discrepancies in the quantity of sutra volumes and variations in scriptural titles. For example, the annotation to Bie yi za ahan jing 别譯雜阿含經 (Alternate Translation of the Miscellaneous Āgama Sūtra) notes: “(According to earlier editions) this scripture was originally divided into twenty juan but has now been combined into sixteen. 按此經……本分二十卷,今併合爲十六卷” () In other cases, several short Buddhist scriptures are grouped together within a single fascicle in the Qing Canon. For instance, in the fifth case of yuan 緣, three scriptures are compiled in one fascicle, including Foshuo qiuyu jing 佛説求欲經 (Sūtra on Desire, translated during the Western Jin 西晉 by Faju 法炬, fl. 290–306), Foshuo shousui jing 佛説受歲經(Sūtra on Adding Monastic Years, translated by Dharmarakṣa, pp. 239–316), and Foshuo fanzhi jishui jing jing 佛説梵志計水净經 (Sūtra of the Brahmanʼs Estimation of Purification by Water, translated during the Eastern Jin dynasty 東晉, pp. 317–420). Thus, the annotation notes: “Three scriptures in one fascicle. 按三經同卷” ()

These three contributions demonstrate that Wang Chang prioritized systematic connections between different canonical editions from the Ming and Qing dynasties, which indicates that he regarded the compilation of Buddhist canons not as a static collection, but as an ongoing process of supplementation and revision. This perspective remarkably anticipates modern scholarly approaches to understanding Buddhist canonical development. His meticulous comparative analysis not only illuminated the textual variations and editorial differences between these canonical collections but also provided subsequent scholars with a comprehensive guide for consulting Ming and Qing Buddhist materials.

3.2. Referencing the Bibliographical Sections in Dynastic Histories

Wang Chang’s second innovative approach centred on his systematic use of official historical documentation. In the process of organizing the catalogue, Wang Chang frequently consulted the bibliographical sections of official dynastic histories to verify the transmission and provenance of individual entries, as well as to situate them within the broader system of Chinese classical texts. This method appears primarily in the “Indigenous writings” (Citu zhushu 此土著述) section, and involves a total of thirteen Buddhist works, including: Ji shamen buying bai su deng shi 集沙門不應拜俗等事 (Collected Accounts on Why Śramaṇas Should Not Pay Homage to Secular Authorities), Lidai sanbao ji 歷代三寶紀 (Records of the Three Treasures Throughout the Successive Dynasties), Zhongjing mulu 衆經目録 (Catalogue of Scriptures), Ji gujin fodao lunheng shilu 集古今佛道論衡實録 (True Accounts of Historical and Contemporary Buddhist–Daoist Polemics), Datang neidian lu 大唐内典録 (Catalogue of Buddhist Works in the Great Tang), Fayuan zhulin 法苑珠林 (Pearl Forest of the Dharma Grove), Ji shenzhou tasi sanbao gantong lu 集神州塔寺三寶感通録 (Collected Records of Miraculous Responses to the Three Treasures at Pagodas and Monasteries across the Divine Land), Datang xiyu ji 大唐西域記 (Record of Travels to Western Lands), Shimen bianhuo lun 十門辯惑論 (Treatise on Clarifying Doubts in Ten Categories), Datang xiyu qiufa gaoseng zhuan 大唐西域求法高僧傳 (Biographies of Eminent Monks who Sought the Dharma in the Western Regions), Zhenzheng lun 甄正論 (Treatise of Revealing the Correct), Yongjia ji 永嘉集 (Collected Works of Yongjia), and Shoulengyanjing yihai 首楞嚴經義海 (Ocean of Meaning in Śūraṃgama Sūtra). These works represent various genres, such as Buddhist catalogues, Buddhist histories, encyclopedic collections, and biographies. Compared to the sutras preserved in the main canon, they are more thoroughly embedded within the textual lineage of dynastic histories.

Taking Fei Changfang’s 費長房 (fl. late 6th century) Records of the Three Treasures Throughout the Successive Dynasties as an example, Wang sequentially cited records from three catalogues (Table 1, ):

Table 1.

Citation of Fei Changfang’s work.

The mutual corroboration of these three bibliographical records not only helps to recover missing information about specific editions but also sheds light on the authorship and the historical evolution of textual structure. A survey of traditional Chinese Buddhist catalogues shows that systematic references to official dynastic bibliographies like the Yiwenzhi and Jingjizhi are rare in monastic cataloguing works, though they appear more frequently in Buddhist historical texts such as the Fozu Tongji 佛祖統紀. This observation underscores the exceptional nature of Wang Chang’s systematic integration of secular bibliographical sources into Buddhist cataloguing practice. By turning to non-Buddhist texts, he sought to supplement the documentary evidence for tracing the transmission of Buddhist works. This integration of secular and religious documentation not only provided more comprehensive historical context for Buddhist works but also legitimized Buddhist materials within established scholarly frameworks familiar to literati readers.

3.3. Valuing Epigraphic Materials

The third distinctive feature of Wang Chang’s methodology was his incorporation of epigraphic materials into Buddhist canonical studies. As a renowned scholar of epigraphy (jinshi xuejia 金石學家) of the Qing dynasty, Wang Chang was widely recognized for his extensive knowledge of stone inscriptions. His Jinshi Cuibian contains over 400 Buddhist stone inscriptions, including temple stelae, records of Buddha’s statues and stone pillars. These entries are accompanied by detailed transcriptions, citations of earlier scholarship, and Wang’s own annotations. Among them are several Buddhist stone sutras, such as the Fengyu huayan jing shibei 風峪華嚴經石碑 (Avataṃsaka Sūtra Stele at Fengyu, engraved during the reign of Empress Wu, pp. 690–705) (see ). In his efforts to compile the catalogue, Wang Chang also placed particular value on both the textual and material significance of stone inscriptions, regarding them as important versions beyond those transmitted through conventional canonical editions.

This feature is first evident in the prefatory section (juanshou 卷首) of the Jieti. There, Wang transcribed six stone inscriptions, organized under two thematic headings. The first, “Fojing shike ji 佛經石刻記” (Stone Inscription of Buddhist Sutras), includes two texts: the Ren Zhigu’s 任知古 (fl. late 8th century) “Inscription for the Buddhist Canon at Ningyi Monastery in Shouguang County of Qing Province” and the Liao 遼 monk Zhicai’s 志才 (fl. early 12th century) “Zhuozhou zhuolushan yunjusi xu mizang shijing ta ji 涿州涿鹿山雲居寺續秘藏石經塔記” (Inscription on the Stone Sutra Pagoda of the Supplement to the Secret Treasure at Yunju Monastery on Zhuolu Mountain of Zhuo Province). The second, “Stele Records on the engraving of Nanzang,” consists of four Ming inscriptions: Feng Mengzhen’s 馮夢禎 (1548–1605) “Yi fu huacheng yuanyin 議復化城緣引” (Proposal for Reviving the Huacheng Canon Project), Huang Ruheng’s 黄汝亨 (1558–1626) “Chongxing huachengsi shu 重興化城寺疏” (Memorial for the Restoration of Huacheng Monastery), Wu Yongxian’s 吴用先 (fl. late 16th century) “Ti chongxing huacheng jiedai si shu 題重興化城接待寺疏” (Commentary on the Memorial for the Restoration of Huacheng Guest Monastery), and Wang Zaijin’s 王在晉 (1568–1643) “Chongfu shuangxi huacheng jiedaisi beiji 重復雙溪化城接待寺碑記” (Stele for the Reconstruction of Shuangxi Huacheng Guest Monastery).10 When comparing the Jieti with corresponding transcriptions in literary anthologies and local gazetteers, textual discrepancies can be observed in the same inscriptions. This indicates that Wang Chang likely consulted stone rubbings or other epigraphic sources during the compilation process.

These stone inscriptions offer contemporaneous documentation of the formation and transmission of different Buddhist canons. The “Inscription for the Buddhist Canon at Ningyi Monastery in Shouguang County of Qing Province” records how a bhikṣuṇī surnamed Ren 任, in commemoration of her parents, established a Buddhist canon at Ningyi Monastery 寧義寺. The inscription listed a total of 41 collections comprising 3100 juan, covering both the sūtra and vinaya texts. The “Inscription on the Stone Sutra Pagoda of the Supplement to the Secret Treasure at Yunju Monastery on Zhuolu Mountain of Zhuo Province” recounts the history of carving Fangshan stone canon 房山石經 from the Sui 隋 (581–618) to the Liao (916–1125) dynasties. The stele explicitly records that “the stone blocks were similar to printing blocks, with front and back sides both utilized, engraving scriptures equivalent to two sheets [of manuscript prepared specifically for stone carving] 石類印板,背面俱用,鐫經兩紙,” revealing detailed practices of layout and carving techniques employed in the production of stone sutras.11 The term “Southern Canon” in “Stele Records on the engraving of Nanzang” refers specifically to the Jiaxing Canon (Jiaxing zang 嘉興藏, also known as the Jingshan zang 徑山藏), a Buddhist canon carved and compiled by private efforts in the late Ming and early Qing. The four stone inscriptions listed under this section mostly concern the donation, relocation, and installation of the woodblocks used for carving the Jiaxing Canon. The four stone inscriptions not only document the historical development of Huacheng Guest Monastery 化城接待寺 from the Song 宋 (960–1279) to the Ming dynasties but also reflect the active involvement of Jiaxing’s local gentry and monastic communities in the reconstruction of the monastery and the formation of the Jiaxing Canon. Overall, preserved as material remains in the local context, stone inscriptions offer valuable records of the production, compilation, storage, and circulation of Buddhist canons. They even retain specific name lists of Buddhist scriptures, which provide many details that extant texts fail to fully represent, thereby aiding later scholars in constructing a more comprehensive understanding of Buddhist canons. Wang Chang’s inclusion of these inscriptions may reflect a similar concern. An annotation by Wang Chang is appended to the “Inscription on the Stone Sutra Pagoda of the Supplement to the Secret Treasure at Yunju Monastery on Zhuolu Mountain of Zhuo Province”, in which he notes the following:

[Author’s] Note: This pillar is approximately five chi in height, and is located in Fangshan County… The inscription refers to the Yunju Monastery stone canon. During the Liao dynasty, Emperor Shengzong (r.982–1031) and Emperor Xingzong (r.1031–1055) both imperially sponsored the continued carving of the canon. At this point, Emperor Daozong (r.1055–1101) again granted funds for its production, yet it still remained incomplete. In the ninth and tenth years of the Da’an reign period (1079–1080), the canon was engraved twice, producing a total of 4080 stone tablets bearing sutras, organized into 44 cases. Subsequently, catalogs of successive sutra production were listed. Every ten juan constituted one case. Each case used characters from the Thousand Character Classic as labels, in a bibliographic system consistent with that of the present canon.12按此幢約高五尺,在房山縣。……記稱雲居寺石經,遼時聖宗、興宗皆賜錢續造。至是則道宗又賜錢造之,而猶未圓。至大安九年、十年兩次鐫經,凡碑四千八十庁,經四十四帙,後列歴次辦經目録。每十卷爲一帙,皆標千字文爲號,與今大藏同例。

Through close reading of the stone inscriptions, Wang Chang concluded that the stone canon engraved in Liao already employed a cataloguing and labelling system consistent with that of the Qing Canon, thereby confirming the long-standing origins of this method of canon compilation. In addition to the textual arrangement, Wang Chang was equally attentive to the material features of Buddhist scriptures across diverse formats. He once identified earlier visual precedents for the frontispiece illustrations (feihua 扉畫) found at the beginning of the woodblock printed Buddhist canons through stone carvings.

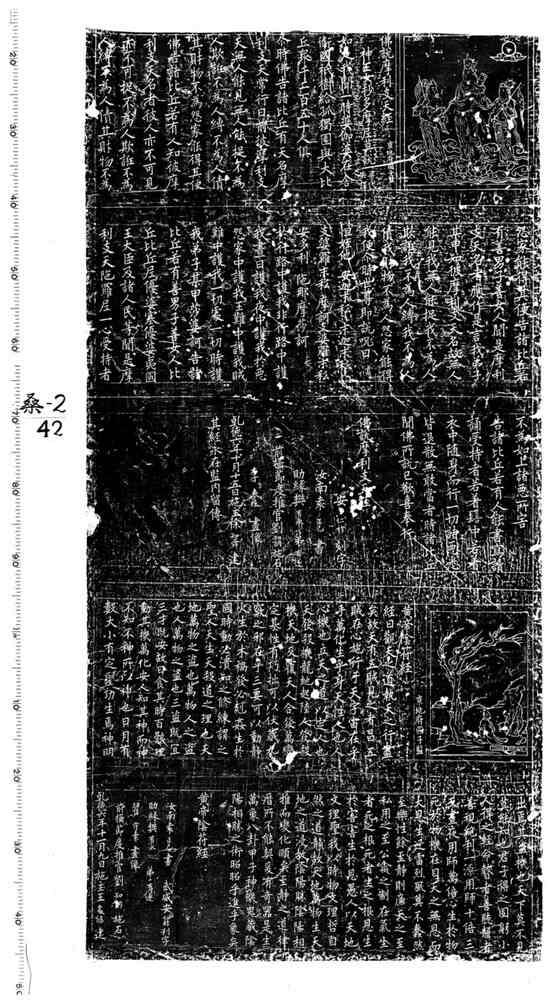

At the head of the scripture [on the Stele of the Mārīcī and Other Sutras (Figure 2, Molizhitian deng jing bei 摩利支天等經碑)] is an engraved buddha image based on a drawing by Li Fenggui (fl. late 10th century) and Zhai Shousu (922–992). Additionally, the Stele of the Changqingjing and Other Sūtras is likewise inscribed with a bodhisattva image. In the present canons, every juan begins with a buddha illustration, a convention which appears to have originated here.()

(《摩利支天等經碑》)經首刻李奉珪、翟守素二人畫佛像。又《常清静等經碑》亦有菩薩畫像。今大藏每經卷首必有佛像,權輿于此。

Wang Chang’s observations were based on the materials available to him at the time. The later discoveries, particularly the manuscripts from Dunhuang 敦煌, have since revealed that the use of frontispiece illustrations at the beginning of Buddhist scriptures predates the examples he referred to.13 The Stele of the Mārīcī and Other Sūtras was carved in the sixth year of the Qiande 乾德 era of the Northern Song (968), and the Stele of the Changqingjing and Other Sūtras dates to the fifth year of the Taiping Xingguo 太平興國 era (980). Both were produced at a slightly later time, so they cannot serve as the true origin. Nevertheless, Wang Chang’s attempt to trace the origins of Buddhist illustrations through stone carvings reveals that, confronted with different canon editions, he was concerned not only with textual content and structural arrangement, but also with material features such as layout, images, and carvers (kegong 刻工). This reflects his effort to incorporate epigraphic materials into the genealogy of canonical editions, enabling broader and more systematic comparison and interpretation.

This incorporation of epigraphic evidence represents Wang Chang’s third methodological innovation, demonstrating that he expanded Buddhist cataloguing beyond traditional textual boundaries to include material and physical dimensions. By treating stone inscriptions as reliable sources for canonical history, Wang Chang established a more comprehensive approach to Buddhist bibliography that integrated physical artefacts with textual records. This methodology not only enhanced the empirical foundation of his cataloguing work but also reflected his broader commitment to evidential scholarship principles that valued material evidence alongside documentary sources. The systematic inclusion of epigraphic materials in canonical studies established a precedent for more integrated approaches to Buddhist textual research.

Figure 2.

Rubbing of the Stele of the Mārīcī and Other Sūtras, collection no. sou0011x, Institute for Research in Humanities, Kyoto University 京都大學人文科學研究所, Kyoto.

In summary, Wang Chang’s Jieti demonstrates a clear evidential approach. First, he established the correspondences across the Ming and Qing imperially sponsored Buddhist canons by comparing case numbers and juan divisions. Second, he cited the catalogues of official dynastic histories to investigate the recording and transmission of canonical texts across historical periods. Third, he actively utilized epigraphic materials to supplement information on the production and dissemination of Buddhist canons, reflecting a bibliographical perspective that placed equal emphasis on transmitted literature and material remains. These methods, at a technical level, resonate with textual collation and cataloguing compilation found in Chinese Buddhist bibliographical traditions. Yet Wang Chang’s intellectual orientation and ultimate aims diverged significantly. The following section demonstrates how Wang Chang, from the perspective of a Confucian literatus, regarded Buddhist scriptures as an additional textual resource worthy of reading and critical application.

4. Wang Chang’s Understanding of Classical Canons: Between Confucian and Buddhist Texts

The Ming and Qing dynasties witnessed imperial policies that were generally tolerant toward religion, which provided favourable conditions for the further spread and adaptation of Buddhism. As a corpus of texts that could be read, organized, and critically compared, Buddhist canons gradually entered the view of the literati and came to serve as new material for evidential scholarship. The involvement of the literati enabled Buddhist scriptures to function not only as objects of religious devotion but also as materials for the study of textual and intellectual history, thereby extending and transforming their cultural value beyond the realm of religion.

Wang Chang was a typical Qing scholar-official. As Li Tiangang 李天綱 (; ) has documented, Wang Chang’s residence adjacent to Yuanjin Monastery 圓津禪院 facilitated regular scholarly gatherings that brought together prominent literati of his time. Through Wang Chang’s connections, figures like Qian Daxin 錢大昕 (1728–1804) and others frequently visited the monastery, engaging in literary exchanges that exemplified the syncretic intellectual culture of the Qianlong era. These interactions demonstrate how Qing scholar-officials seamlessly integrated Confucian, Buddhist, and Daoist elements in their scholarly pursuits, embodying what Li Tiangang describes as the “Three Teachings Rooted in One” (sanjiao tongti 三教通體) approach that characterized late imperial intellectual culture. Wang Chang’s engagement with the Qing canon must be understood within this context of syncretic scholarly culture.

His relationship with Chinese Buddhist canons was not that of a central figure within the religious community, with the authority to transmit its teachings, but rather that of a marginal participant situated at the intersection of multiple knowledge networks. Rather than being a monk or a professional translator of Buddhist scriptures, he was a gentry scholar who trained in Confucian learning and specialized in textual research, with a general knowledge of Buddhist teachings. As mentioned earlier, his involvement in official proofreading tasks provided him with systematic access to the complete Qing canon. His approach to the Qing Canon was deeply influenced by the academic trends of the Qianlong and Jiaqing eras, with an emphasis on textual lineage, philological evidence, and comparative analysis of variant versions. From this non-sectarian perspective, Wang Chang attempted to respond to the complexity and fluidity of canonical knowledge by using familiar cataloguing methods and textual organization techniques. The Jieti was precisely the outcome of his work at this marginal and intersecting point.

There is no doubt that reading Buddhist canons exerted a lasting influence on Wang Chang throughout his life. In the 35th year of the Qianlong era (1770), Wang Chang accompanied the army into Yunnan 雲南. During this journey, his longstanding Buddhist interests also shaped his itinerary. In order to fulfil a long-cherished wish, he took leave to visit the renowned scenic spot of Jizu Mountain 雞足山, which is traditionally venerated in Chinese Buddhist culture as the place where Buddha’s disciple Mahākāśyapa is said to have entered into meditative concentration (samādhi). Located in western Yunnan, this mountain has long been a pilgrimage site associated with esoteric practices and the transmission of the Buddha’s robe, and it remains one of the most sacred Buddhist mountains in China.14 At the beginning of his travelogue, Wang Chang wrote the following:

Twenty years ago, when I was reading Buddhist canons, I came across the account that Mahākāśyapa, after the Buddha’s parinirvāṇa, took the saṃghātī robe15 and entered Great Mount Jizu to await the descent of Maitreya. I found this particularly remarkable.()

Even in his later years, Wang Chang remained committed to compiling the Jieti, which clearly demonstrates his persistent dedication to the study of Buddhist canons. Nevertheless, he consistently regarded himself as a Confucian scholar, and his stance never wavered. His exploration of Buddhist scriptures did not alter his fundamental academic orientation.余二十年前讀藏經,云摩訶迦葉於世尊入滅後,持僧金黎伽衣入大雞足山,竢慈氏下生,異之。

The above discussion of Wang Chang’s reference to the bibliographical sections in dynastic histories like Songshi yiwen zhi not only provides supplementary evidence for the compilation, translation, and dissemination of Buddhist scriptures but also reveals his attempt to examine and position Buddhist scriptures within the Chinese philological tradition. This constitutes the very starting point of Wang Chang’s understanding of Buddhist texts. In the entry for the Modengjia jing 摩登伽經 (Mātaṅga sutra, translated by Zhu Lüyan 竺律炎 and Zhi Qian 支謙 during the Three Kingdoms period, pp. 220–80) in the Jieti, there is an annotation stating:

The lower juan of this scripture, in the ‘Chapter on Observing Calamities and Auspicious Signs’, discusses the signs of good and ill associated with the movements of the stars, which can be cross-referenced by what is said in Confucian writings on astronomy and the Five Phases.()

When reading Buddhist scriptures, Wang Chang intentionally brought them into dialogue with traditional Chinese theories of yin 陰 and yang 陽, seeking to find conceptual resonances between the two traditions. His purpose in writing annotations was not only to record his own scattered insights, but also to demonstrate a particular approach to reading scriptures. As such, it offered not merely a textual comparison but also a methodological inspiration. This juxtaposition between Buddhist scriptures and Confucian texts finds further expression in a broader comparison of the two classical systems. Wang Chang compared the transmission of canonical texts in both traditions and highly praised the compilation, printing, and preservation of Buddhist scriptures:此經下卷《觀災祥品》言星紀所行善惡之相,可與儒書言天文五行者參考。

As for Buddhism, however, this was not the case. The total number of sutras, vinayas, and treatises from the Mahayana and the lesser vehicle traditions amounted to 4660 juan. Some of their disciples traveled tens of thousands of miles to bring these scriptures into Zhendan (i.e., China); others passed through dozens of winters and summers journeying to search for them. Once they obtained these scriptures, they cherished and protected them like their own head, eyes, brain, and marrow, collecting and preserving them, recording their dates, marking the names of their translators, and continually adding Chinese writings as supplements. The disciples not only copied and printed by themselves, but also sought assistance from officials, elders, and laypeople, and moreover persuaded the rulers of this world into carving and printing for them, storing [the scriptures] separately in famous mountains and ancient monasteries. Thus, from the Han dynasty, Wei-Jin, Five Dynasties, and Tang, none of the translated scriptures were lost. Looking at our Confucian books, they became increasingly lost through transmission. How could they possibly be spoken of in the same breath! Now, our Confucian scholars of classical learning and literary composition mostly came from the Central Plains, unlike India and Sindhu,16 which lay beyond the distant frontiers in the southwest, where one must climb mountains and cross seas, brave dangers, traverse flowing sands and piled rocks, before obtaining them. After the seal and clerical scripts came the standard script. Based on the patterns [of these scripts], one could understand the meaning. Both the learned and the unlearned could comprehend them. This was unlike the Sanskrit characters from India,17 which had to be repeatedly translated by Dharma masters, written down by hand, and refined in literary style before they could be read.18 That Confucian texts should be lost to such an extent, while Buddhist scriptures remain so fully preserved. It clearly shows that our Confucians’ interest in antiquity falls far short compared to the treasuring and protecting of the Buddhist disciples.()

This inscription was written for Xingshan Monastery 興善寺 in Xi’an and inevitably contains some praise, but its critical awareness should not be overlooked. Wang Chang pointed out that Buddhist scriptures were vast in number and often not written in Chinese, making them difficult to read. However, owing to the treasuring and careful preservation by disciples, and the combined efforts of translators, compilers, and rulers, they were kept intact without loss. In contrast, the Confucian classics, though grounded in a native script and transmitted by native scholars, were “increasingly lost through transmission.” Such an evident difference suggests that the survival of texts depended more on social and cultural commitment than on linguistic or regional advantages. Behind this, Wang Chang likely intended to use Buddhism as a mirror to reflect on Confucianism, hoping to encourage scholars to pay more attention to the preservation of Confucian texts.若釋氏不然,大小乘經、律、論爲數至四千六百六十卷,其徒或歴數萬里,挾以入震旦;或閲數十寒暑,而往求焉。比其得,愛䕶如頭目腦髓,彙而藏之,著其時代,標以譯人姓名,又以支那譔述隨時增入。其徒既自書寫剞劂,復丐宰官長者居士助之,且聳動世主爲之鏤刻,分貯於名山古寺。故兩漢、魏晉、五代曁唐,譯出之經無有遺佚者。視吾儒之書,寖傳寖失,豈可同日語哉!夫吾儒經術文章之士,多出於中原,非若印度、身毒,在西南絶徼之外,必梯山航海,冒危險,歴流沙積石,而後可得之也。篆隸之後,繼以楷書,因文考義,智愚共曉,非若西天梵字,必法師重譯,執筆潤文,而後可讀也。而遺佚若此,全備若彼,是吾儒之好古,較諸釋氏之寶䕶,弗如遠甚明矣!

Wang Chang’s understanding of Buddhist canons stemmed not only from his personal education in Confucianism and training in classical studies but was also closely connected to the textual classification and scholarly order of his time. Another major cultural project during the Qianlong reign was the compilation of Siku Quanshu 四庫全書. Many scholars have noted that the Siku Quanshu’s selective inclusion and critical treatment of Buddhist texts emphasize the marginalized status of Buddhist works within the Siku Quanshu and the underlying expression of official will and Confucian stance.19 To some extent, such conclusions treat religion and central political authority as opposing forces. This paper seeks to reexamine from the perspective of knowledge how Qing scholars responded to and organized the overwhelming abundance of texts. As a scholar has pointed out, the Siku Quanshu’s classificatory structure is fundamentally based on the notions of directionality and orientation, and the treatment of religious content within the collection reflects a broader ecumenical spirit (). Wang Chang, as an important scholar-official in the Qing court and a literatus, was likewise situated within this mainstream scholarly current. A careful comparison between the Jieti and the Siku Quanshu Zongmu 四庫全書總目 reveals similar intellectual orientations. Among the Buddhist texts included in the Siku Quanshu, Zhi Sheng’s 智昇 Catalogue of Buddhist Works Compiled During the Kaiyuan Period (Kaiyuan shijiao lu lüechu 開元釋教録) had a particularly close connection to Wang Chang, as the edition in the Siku Quanshu came from Wang’s personal collection. The Siku Quanshu Zongmu discusses this work, not only comparing the organizational principles of the Kaiyuan Shijiao Lu with Zhu Yizun’s 朱彝尊 (1629–1709) classical studies work Jingyi Kao 經義考, but also systematically tracing how Buddhist scriptures entered the bibliographic traditions. It points out that bibliographical sections in dynastic histories contained many omissions in their documentation of Buddhist texts; thus, Siku Quanshu Zongmu preserved selected works for scholarly reference (). This approach bears striking similarities to the direction found in Jieti’s annotations.20 Both the Siku Quanshu Zongmu and the Jieti can be viewed as specific responses to the Qing dynasty’s intellectual challenge of managing an overwhelming abundance of textual materials. As () has argued in his study of the Siku Quanshu, the Qing court’s editorial enterprises were driven not merely by ideological imperatives but by an epistemological need to organize, delimit, and make sense of the ever-expanding corpus of inherited texts. Wang Chang’s compilation of the Jieti similarly responded to this challenge. As a canon catalogue, the Jieti broke free from religious contexts and did not aim to reaffirm the sanctity or religious authority of Buddhist canons. Rather, by including multiple versions and diverse sources, Wang Chang sought to position and reconstruct knowledge, reflecting a philological intention that emphasized both compilation and application. Without departing from the Confucian scholarly tradition, he actively engaged in the integration and interpretation of Buddhist texts, undertaking a mode of textual organization that combined both Confucian and Buddhist perspectives. This practice not only reflects his scholarly interest in Buddhism but also illustrates how Qing scholars, amid the torrent of diverse knowledge, sought to endow classical texts with a new order and meaning through comparison and reconfiguration.

This process of textual reordering resonates with recent theoretical insights into the epistemic functions of Buddhist catalogues. As Feng Guodong () has pointed out in his Studies on Chinese Buddhist Catalogues, the evolution of catalogue structures often reflects shifts in the cataloguer’s knowledge interests, meaning what kinds of information were prioritized, and knowledge boundaries, meaning what was understood or remained obscure within a given historical moment. Although Wang Chang did not alter the institutional structure or textual sequence of the Qing Canon, his application of philological and bibliographic methods enabled Buddhist canonical knowledge to circulate within more accessible, secularized scholarly frameworks. In this sense, the Jieti exemplifies a broader pattern of change and innovation in Buddhist bibliography from the late Ming to the modern period.

5. Conclusions

Contemporary scholarship has come to recognize that the Chinese Buddhist canon is not a static and sealed collection of scriptures, but rather a historically evolving, multi-layered system infused with centuries of annotation, translation, and editorial selection. Each stage of a canon’s formation, from copying and editing to printing, distribution, and cataloguing, was shaped by the collective efforts of a wide range of social groups, including monks, literati scholars, court officials, printers and engravers, and the local gentry. The readers and interpreters of Buddhist canons were no longer merely passive recipients of established doctrine, but active practitioners who, under specific historical conditions, engaged with canons and contributed to their interpretation and understanding.

Building on the perspective above, this study has examined Dazang shengjiao jieti, Wang Chang’s catalogue of the Qing canon, as both a personal reading record and a broader scholarly intervention. Wang Chang’s engagement with Buddhist materials exemplifies a broader pattern of literati participation in Buddhist studies during the Qing dynasty, though his systematic application of evidential scholarship methods to canonical cataloguing appears to have been unique among his contemporaries. As Wang Chang’s Jieti represents the earliest Buddhist catalogue compiled by a literatus during the Qing dynasty, no previous studies have examined this unique form of cross-traditional scholarship. This research, therefore, fills a significant gap in our understanding of how Confucian scholar-officials engaged with Buddhist canonical materials and contributes to both Buddhist catalogue studies and Qing intellectual history by revealing previously unexplored mechanisms of knowledge integration across religious and secular scholarly traditions. What distinguishes the Jieti is not only its content but its producer and methodology. Compiled by a Confucian literatus rather than a monastic editor, the work brings together Buddhist classificatory logic with evidential and philological methods cultivated in Qing scholarly traditions. This synthesis reflects both Wang’s deep engagement with his intellectual milieu and his capacity to adapt Confucian analytical tools to religious knowledge domains. Wang Chang’s work also addressed a practical need created by the limited availability of cataloguing aids. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, several different Buddhist canons were produced by both imperial and private efforts, creating an increasing need for works that could guide canon reading. However, for the Qing Canon, apart from the official catalogue Daqing Sanzang Shengjiao Mulu 大清三藏聖教目録, related reading catalogues were absent. Wang Chang addressed this gap when compiling the Jieti. The Jieti was not merely a personal memorandum for his own canonical work but served as a guide to the Qing Canon for other scholars, particularly literati readers. Thus, the Jieti emerged as a unique canonical guide that embodied a form of Buddhist canon reading distinctive to Qing scholar-officials.

Wang Chang’s scholarly practice has revealed that literati engaged in the study and interpretation of these texts in ways shaped by their social identities, intellectual commitments, political contexts, and the conditions of textual production, resulting in a variety of complex interpretive approaches. Within a predominantly Confucian epistemological order, Qing’s literati participation in the study of Buddhist canons cannot be reduced to a binary of acceptance or rejection, nor merely to declarations of religious stance. Rather, their interpretive acts reflected conscious evaluation and repositioning concerning the classification of knowledge, the textual value of Buddhist scriptures, and their scholarly utility. Wang Chang’s approach constituted one of the key modes through which scholars integrated insights from Confucian practical learning and Buddhist scholarship. More significantly, his systematic application of Confucian evidential methods to Buddhist canonical research represents a methodological innovation that enhanced the accessibility of Buddhist materials for the literati community while demonstrating how rigorous philological approaches could be productively adapted across different intellectual traditions. This study has provided a philological framework for understanding how canonical materials circulated, were received, and reinterpreted across intellectual traditions, revealing that in eighteenth-century China, Buddhist canonical traditions inspired Confucian scholar-officials’ scholarship in multiple dimensions, including textual content, cataloguing practices, and material characteristics. Further investigation into Wang Chang’s broader corpus, including his poetry, essays, and epigraphic commentaries, may yield deeper insights into how he understood and reinterpreted Buddhist teachings within his Confucian scholarly framework.

Beyond these contributions to cross-traditional scholarship, Wang Chang’s work also anticipates certain modern approaches to Buddhist studies. Although Wang Chang’s work clearly belongs to the Qing tradition of evidential learning and philological scholarship, some of his textual strategies, such as his emphasis on dynastic histories and his use of epigraphic materials, show a remarkable proximity to modern scholarly perspectives and methods in the study of Buddhist texts. While he was not engaged in Buddhist philology in the modern disciplinary sense, his treatment of Buddhist scriptures as objects of rigorous textual inquiry rather than purely religious devotion reflects a significant shift in intellectual approach. His Jieti illustrates that the Buddhist literature began to be reorganized as a form of knowledge resource, aligning with the broader transformation of Buddhist cataloguing practices since the late Ming period.

Funding

This research was funded by the Youth Project of the Chinese National Social Science Fund “Compilation and Research on Buddhist Stone Inscriptions Recorded in Jinshi Cuibian and Baqiongshi Jinshi Buzheng” “中國國家社會科學基金青年項目《金石萃編》《八瓊室金石補正》所載佛教石刻文獻的整理與研究” (25CZJ010).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Zhongguo guji zongmu (zibu) 中國古籍總目(子部) () erroneously records the title as “Dazang shengjiao tijie 大藏聖教題解” and omits the volume count. This error appears to derive from Jiangsusheng li guoxue tushuguan tushu zongmu (). There is also a record attributing this work to Zhu Wenzao 朱文藻 (1735–1806) (), but the extant copy shows “Compiled by Wang Chang whose courtesy name was Defu, a native of Qingpu (now part of present-day Shanghai) 青浦王昶德甫譔集” at the beginning of each fascicle (), confirming that the compiler was undoubtedly Wang Chang. |

| 2 | The revision and suppression of the Qing Canon woodblocks was an important procedure reflecting state power in the formation of Buddhist canons. After the completion of the Qing Canon, the Qianlong Emperor conducted three rounds of destruction and revision of the woodblocks used in the canon. The first occurred in 1765, when Qian Qianyi’s 錢謙益 (1582–1664) commentary to the Śūraṃgama Sūtra (Da fo ding shou lengyan jing shujie meng chao 大佛頂首楞嚴經疏解蒙鈔) was removed. The second took place in 1769, when texts such as Da ming renxiao huanghou meng gan fo shuo diyi xiyou da gongde jing 大明仁孝皇后夢感佛説第一稀有大功德經 were withdrawn. The third occurred in 1776, when prefaces by Empress Wu Zetian 武則天 (r.690–705) were removed from sutras such as the Avataṃsaka Sūtra. The deletion of the Digest of Catalogue of Buddhist Works Compiled During the Kaiyuan Period occurred during the second round of block removals (; ). Some scholarly works mistakenly record the deleted catalogue title as “Kaiyuan Shijiao Lu Lüe 開元釋教録略” (e.g., ; ), which is an error. |

| 3 | Wang Chang recorded this event as occurring in 1763 in his Huhai shi zhuan 湖海詩傳: “In the guiwei year of the Qianlong reign, His Majesty wished to revise and correct the Xuzang Jing. Liu Wengong of Zhucheng entrusted Kanggu and me with this task. Our examination and decisions on what to retain or remove all met with imperial approval. 乾隆癸未,上欲删正《續藏經》,諸城劉文正公屬予與康古任之,考訂去取,俱稱上旨。” () Kanggu refers to Wang Mengjuan汪孟鋗 (1721–1770), who undertook this task together with Wang Chang. This can be corroborated by another poem “Fengming Tong Wang Sheren Kanggu Yue Xuzang Jing奉命同汪舍人康古閲續藏經” (). |

| 4 | Dongcheng ji yu 東城記餘 by Yang Wenjie 楊文傑 (1808–1878) of the Qing dynasty (). |

| 5 | The copy currently held in Nanjing Library may be related to the one formerly held in Qingyin’ge. After the dispersal of the Qingyin’ge collection, some materials were acquired by the Baqian juan lou 八千卷楼 of the Ding family in Hangzhou. During the early period of the War of Resistance Against Japan, the Jiangsu Provincial National Studies Library (predecessor to Nanjing Library) acquired collections from various private libraries in Jiang region 江南 (literally “south of the river,” refers to the prosperous region south of the Yangtze River, encompassing areas of present-day southern Jiangsu, northern Zhejiang, and Shanghai), including materials from the Ding family collection. This suggests that the Jieti may have passed through a transmission sequence from Qingyin’ge to Baqian juan lou to Nanjing Library. However, this particular work is not recorded in the catalogue of Baqian juan lou, so the exact transmission path remains unclear and requires further investigation (; ). |

| 6 | Among these Buddhist scriptures, Wang Chang particularly treasured a Song dynasty edition of the Lotus Sutra. In a letter to Abbot Huizhao 慧照 (fl. late 18th century) of Yuanjin Monastery 圓津禪院, he mentioned: “I have found in my collection a Song edition of the Lotus Sutra in seven ce and two juan, with a postscript by Siweng 思翁 at the end. It is truly a dharma treasure that can protect the monastery. (家中)檢出宋版《妙法蓮華經》七册二卷,末有思翁書跋語,實爲法寶,可以鎮山。” Siweng refers to Dong Qichang 董其昌 (1555–1636) (; ). |

| 7 | There are different scholarly views regarding the editions of the imperially commissioned Southern Canon in the early Ming dynasty. For ease of understanding, this paper follows the mainstream view by referring to the Buddhist canon printed at the Tianxi Monastery 天禧寺 in Nanjing during the Yongle era and widely transmitted in later generations as the “Yongle Southern Canon,” also known as the “Re-carved Southern Canon.” See (; ). A new theory argues that the “Yongle Southern Canon” was actually a revised and supplemented edition of the Hongwu 洪武 Canon and does not essentially exist as a separate work (). |

| 8 | This situation is frequently seen in the “Indigenous writings” (Citu zhushu 此土著述) section. When the Yongle Southern Canon did not include relevant writings, Wang Chang’s reference to “Ming Canon” actually refers to the Yongle Northern Canon. For instance, under the entry for Huayan huiben xuantan huixuan ji 華嚴會本懸談會玄記, he notes “also found in Mingzang from the ju 鉅to the ting 庭,” while Zheyi lun 折疑論 and Huayan yuanren lun jie 華嚴原人論解 are noted as “both found in Mingzang under zi 茲,” all of which were included in the Northern Canon. However, some entries exist only in the Northern Canon but were not mentioned by Wang Chang, such as Chanlin baoxun 禪林寶訓 (; ). |

| 9 | Long, Darui. “Managing the Dharma Treasure: Collation, Carving, Printing, and Distribution of the Canon in Late Imperial China” (). |

| 10 | Most of these inscriptions are not included in Jinshi Cuibian. There are two possible reasons for this: first, such as Ren Zhigu’s work, it was likely not available during the compilation and was later supplemented by Zhu Wenzao; second, the four Ming dynasty inscriptions were excluded because the editorial principles of the Jinshi Cuibian did not include Ming and Qing period inscriptions. |

| 11 | Lothar Ledderose’s comparative analysis of the Qidan Canon 契丹藏 and the Buddhist stone scriptures at Fangshan reveals systematic differences in format specifications between stone and woodblock sutra production, including variations in characters per line, lines per sheet, and sheets per fascicle. See (). |

| 12 | This stone inscription and the accompanying annotation by Wang Chang can be found in the Jinshi Cuibian, with roughly the same content (). |

| 13 | The Mogao Cave 17 was discovered accidentally by a Daoist Abbot named Wang Yuanlu 王圓禄 in 1900, which contained numerous Buddhist sutra scrolls that provide evidence of earlier practices. For instance, the influential scroll Or.8210/P.2, a printed copy of Jingang jing 金剛經 (Diamond Sutra, Skt. Vajracchedikā prajñāpāramitā sūtra) in the ninth year of the Xiantong 咸通 era of the Tang dynasty (868), features a woodcut illustration at the beginning of the scroll, which shows the Buddha expounding the Dharma. International Dunhuang Project. Dunhuang Manuscript Collections. Available online: https://idp.bl.uk/collection/51FDAEAFB4A24E2E9981692A98130BC8/?return=%2Fcollection%2F%3Fterm%3DOr.8210%252FP.2 (accessed on 31 August 2025). |

| 14 | Following the pattern of Chinese Buddhist sacred site construction, Jizu Mountain represents a simulacrum of the original Indian Kukkutapāda-giri (). () has pointed out that Mount Jizu in Yunnan rapidly became a Buddhist sacred landscape from the mid-Ming onward under the multiple influences of local agency, acculturative pressures, state-building imperatives, late-Ming Buddhist revival, literati networks, and the strategic mobilization of symbolic capital. Wang Chang’s yearning for Mount Jizu reflects this broader cultural transformation that made the mountain an attractive destination for literati seeking spiritual and intellectual experiences. |

| 15 | The term “僧金黎伽衣” is likely a mistaken transcription of “僧伽梨衣,” a common Chinese rendering of the Sanskrit saṃghāṭī, referring to the large patchwork robe worn by monks on formal occasions. The phrase “僧金黎伽衣” has no known usage beyond this instance. The character 黎 may be a phonetic error for 梨, as both are pronounced lí. |

| 16 | Both “India” (Yindu 印度) and “Sindhu” (Shendu 身毒) refer to the same geographical region. The relationship between these terms is explained in Buddhist dictionaries such as the Yiqie jing yinyi 一切經音義 (The Sounds and Meanings [of all the words in] the Scriptures, compiled by Xuanying 玄應 of the Tang dynasty). Wang Chang’s Jinshi cuibian 金石萃編 includes inscriptional commentaries by Bi Yuan 畢沅 (1730–1797) and Qian Daxin 錢大昕, both of whom referenced Xuanying’s work (). Given Wang Chang’s close associations with these scholars, it is reasonable to assume his familiarity with this source and awareness that Yindu and Shendu refer to the same place. |

| 17 | Wang Chang’s original text uses “Xitian 西天” (literally “Western Heaven”), a traditional Chinese Buddhist term for India, reflecting India’s position as the western source of Buddhism for China. |

| 18 | In the classical Chinese Buddhist translation system, sutras were often translated through a collaborative, multi-stage process. Runwen 潤文refers to a stage known as stylistic polishing, in which literati or assistants would revise the Chinese text for clarity and fluency, without necessarily consulting the Sanskrit original. During the Tang dynasty, the practice of runwen was also referred to as runse 潤色. As Buddhist translation activities gained imperial attention, high-ranking officials were occasionally appointed to oversee this stage of stylistic refinement. However, this role was not institutionalized, nor was runwen a formal official title at the time. During the Song dynasty, the Runwenguan 潤文官, a formal office responsible for literary refinement, began to take shape within the sutra translation system (; ). |

| 19 | Apart from the entries recorded in the Buddhist section of zibu 子部, the Siku Quanshu also included Buddhist-related works such as poetry collections by monks and monastery gazetteers (; ; ). |

| 20 | Wang Chang maintained close associations with the Siku Quanshu editorial group. The project’s earliest director, Liu Tongxun, was the same official who had entrusted Wang with revising Xuzang. Many of Wang’s friends, including Weng Fanggang 翁方綱 (1733–818) and Shao Jinhan 邵晉涵 (1743–96), participated in the Siku Quanshu compilation. Based on the official positions mentioned when books were submitted, Wang Chang’s involvement with the Siku Quanshu likely occurred in the 1740s, when he was observing the mourning period for his mother and remained out of office for three years. The composition and compilation of the Zongmu took place during this same period, suggesting the possibility that Wang Chang participated in writing the abstracts for Buddhist texts. |

References

- Cao, Ganghua 曹剛華. 2021. Siku Quanshu Zongmu dui Fojiao Shiji de Zhulü he Pingshu 《四庫全書總目》對佛教史籍的著録和評述 [Bibliographic Records and Commentaries on Buddhist Historical Texts in the Siku Quanshu Zongmu]. Journal of Historiography 史學史研究 2: 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Li 陳立. 2015. Nanjing Tushuguan Guji Zhengli Yanjiu yu Tuiguang 南京圖書館古籍整理研究與推廣 [The Collation and Promotion of Ancient Books at the Nanjing Library]. Studies on Ancient Book Preservation 古籍保護研究 1: 280–86. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Xiaodan, and Liang Li. 2025. The Thirteen Yamen and the Printing of the Yongle Nanzang in the Shunzhi Reign. Religions 16: 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Guodong 馮國棟. 2025. Hanwen Fojiao Mulu Yanjiu 漢文佛教目錄研究 [Studies on Chinese Buddhist Catalogues]. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe 上海古籍出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Yiqiang 付壹强. 2019. Qianlong Dazangjing de Kanke yu Liuchuan 乾隆《大藏經》的刊刻與流傳 [The Carving and Circulation of Qianlong Canon]. Fayin 法音 4: 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gandolfo, Serena. 2020. The Streams of Knowledge: Organising the Siku Quanshu 四庫全書. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- He, Mei 何梅. 2005. Ming Yongle Nanzang Yanjiu 明《永樂南藏》研究 [A Study of the Yongle Southern Canon of the Ming Dynasty]. Zhongguo Dianji yu Wenhua Lunsong 中國典籍與文化論叢 8: 52–73. [Google Scholar]

- He, Mei 何梅. 2013. Lidai Hanwen Dazangjing Mulu Xinkao 歷代漢文大藏經目録新考 [A New Study of Catalogues of the Chinese Buddhist Canon Throughout History]. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press 社會科學文獻出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Chenguang 胡晨光. 2020. Beilu Er Zhong zhi ‘Qingyin’ge Chaoben’ Bianxi 《碑録二種》之“清吟閣抄本”辨析 [An Analysis of the “Qingyin Pavilion manuscript copy” Version of Two Kinds of Stele Records]. Library Research and Work 圖書館研究與工作 7: 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Qijiang 黄啓江. 1990. Songdai de Yijing Runwenguan yu Fojiao 宋代的譯經潤文官與佛教 [The Stylistic Editors in Song-Dynasty Sutra Translation and Buddhism]. The National Palace Museum Research Quarterly 7: 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jiangsu Shengli Guoxue Tushuguan 江蘇省立國學圖書館, comp. 1931. Jiangsu Shengli Guoxue Tushuguan Tushu Zongmu 江蘇省立國學圖書館圖書總目 [General Catalog of the Jiangsu Provincial National Studies Library]. Lead-printed edition. no. 樵0172, 0173. Ningbo: Tianyige Library 天一閣. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Xinxia 來新夏. 1991. Gudian Muluxue 古典目録學 [Classical Bibliography]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company 中華書局. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Xinxia 來新夏. 1997. Qingdai Mulu Tiyao 清代目録提要 [Annotated Bibliographies of Catalogues in the Qing Dynasty]. Jinan: Qilu Shushe 齊魯書社. [Google Scholar]

- Ledderose, Lothar. 2006. 石類印板:房山雲居寺石經與契丹藏 The Stones Resembled Printing Blocks: The Engraved Buddhist Stone Scriptures at Yúnjū Monastery of Fángshān and the Qìdān Canon. In Studies in Chinese Language and Culture: Festschrift in Honour of Christoph Harbsmeier on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday. Edited by Christoph Anderl, Halvor Eifring and Jens Braarvig. Oslo: Hermes Academic Publishing, pp. 319–29. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jianzhong 李建中, and Huangkun Wu 吳煌坤. 2022. Cong Siku Zongmu Shijia Lei ‘Xiao Sibu’ Kan Siku Guancheng de ‘Duanxing Siwei’ 從《四庫總目》釋家類“小四部”看四庫館臣的“端性思維” [Examining the Qing Compilers’ Moral Categorization through the “Minor Four Divisions” in the Buddhist Section of the Siku Quanshu Zongmu]. Humanities Journal 人文論叢 2: 181–93. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Shunchen 李舜臣, and Jianglin Ouyang 歐陽江琳. 2006. Siku Quanshu Zongmu zhong de Shiseng Bieji Piping 《四庫全書總目》中的詩僧别集批評 [Critiques of Buddhist Poets’ Collected Works in the Siku Quanshu Zongmu]. Journal of Wuhan University (Humanities Edition) 武漢大學學報(人文科學版) 5: 571–75. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Tiangang 李天綱. 2015. Sanjiao tongti: Shidafu de zongjiao taidu 三教通體:士大夫的宗教態度 [Unity of the Three Teachings: The Religious Attitudes of the Literati]. Xueshu Yuekan 學術月刊 5: 108–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Cheng 呂澂. 1991. Lü Cheng Foxue Lunzhu Xuanji 呂澂佛學論著選集 [Selected Writings on Buddhist Studies by Lü Cheng]. Jinan: Qilu Shushe 齊魯書社. [Google Scholar]

- Nanjing Tushuguan Zhi Bianxiezu 《南京圖書館志》編寫組, comp. 1996. Nanjing Tushuguan Zhi (1907–1995) 南京圖書館志(1907–1995) [Gazetteer of the Nanjing Library (1907–1995)]. Nanjing: Nanjing Chubanshe 南京出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Qing Shilu 清實録. 1985. [The Veritable Records of the Qing Dynasty]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company 中華書局. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Shiying 瞿世瑛. n.d. Qingyin’ge Shumu 清吟閣書目 [Catalogue of the Qingyin Pavilion Collection]. Manuscript copy, no. 目440 8756.2. Beijing: National Library of China 國家圖書館.

- Robson, James. 2010. Buddhist Sacred Geography. In Early Chinese Religion, Part Two: The Period of Division (220–589 AD). Edited by John Lagerwey and Pengzhi Lü. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1353–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Yuan 阮元. 1993. Gaoshou Guanglu Dafu Xingbu You Shilang Wang Gong Chang Shendaobei 誥授光祿大夫刑部右侍郎王公昶神道碑 [Epitaph for Minister Wang Chang, Right Vice Minister of Justice and Grand Master for Glorious Happiness by Imperial Grant]. In Beizhuan Ji 碑傳集 [Collected Inscriptions and Biographies]. Compiled by Qian Yiji 錢儀吉. Collated by Jin Si 靳斯. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company 中華書局, vol. 37, pp. 1061–64. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Dingyuan 釋定源. 2024. Hongwu Zang yu Jianwen Zang Xinshi 《洪武藏》與《建文藏》新識 [New Insights into the Hongwu Canon and Jianwen Canon]. Studies in World Religions世界宗教研究 9: 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Chang 王昶. 2013. Chunrong tang ji 春融堂集 [Collected Works from the Chunrong Hall]. Edited and punctuated by Mingjie Chen 陳明潔, Huiguo Zhu朱惠國 and Fengshun Pei 裴風順. Shanghai: Shanghai Culture Publishing House 上海文化出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Chang 王昶, comp. 2018. Huhai Shichuan 湖海詩傳 [Annotated Poetry Anthology from Lakes and Seas]. Xinggen Zhao 趙杏根, Xianghuai Lu 陸湘懷, and Heng Zhao 趙衡, eds. Nanjing: Fenghuang Chubanshe 鳳凰出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Chang 王昶. 2020. Jinshi Cuibian 金石萃編 [Collected Inscriptions on Bronze and Stone]. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe 上海古籍出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Chang 王昶. n.d.a. Dazang Shengjiao Jieti 大藏聖教解題 [Annotated Bibliography of the Sacred Teachings in the Buddhist Canon]. Manuscript n copy, no. GJ/EB/41132, Guoxue Hall 國學館. Nanjing: Nanjing Library 南京圖書館.

- Wang, Chang 王昶. n.d.b. Shunan Shuku Mulu Chubian 塾南書庫目録初編 [First Compilation of the Shunan Book Repository Catalogue]. Woodblock print, no. GJ/EB/42577. Nanjing: Nanjing Library 南京圖書館.

- Wang, Guoping 王國平, and Zhijian Chen 陳志堅, eds. 2014. Wulin Zhanggu Congbian (13) 武林掌故叢編(十三) [Collected Anecdotes of Wulin]. Hangzhou: Hangzhou Publishing House 杭州出版社, vol. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Lianxi 翁連溪. 2015. Cong Longzangjing Jingban Zhengli Zhong Xin Faxian de Wenti Kan Qianlong Huangdi dui Wenzhang de Shangai yu Chehui 從《龍藏經》經版整理中新發現的問題看乾隆皇帝對文章的刪改與撤毀 [Revisions and Suppressions by the Qianlong Emperor: New Issues Found in the Woodblock Organization of Longzang Canon]. Studies on Ancient Book Preservation 古籍保護研究 1: 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Jiang, and Lucille Chia, eds. 2015. Spreading Buddha’s Word in East Asia: The Formation and Transformation of the Chinese Buddhist Canon. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Jiang 吴疆, and Qiyuan Wang 王啓元, eds. 2021. Fofa yu Fangfa: Ming Qing Fojiao ji Zhoubian 佛法與方法:明清佛教及周邊 [Buddhism and Method: Ming-Qing Buddhism and Its Peripheries]. Shanghai: Fudan University Press 復旦大學出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Yunqing 武雲清. 2017. Wang Chang de Chanxue zhi Shi yu “Li Yin” Xintai 王昶的禪學之嗜與”吏隱”心態 [Wang Chang’s Interest in Chan Buddhism and His “Finding Retreat through Official Duty” Mentality]. Journal of Northwest Normal University (Social Sciences Edition) 西北師範大學報(社會科學版) 6: 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Jianhua 徐建華. 1990. Zhongguo Gudai Duzang Mulu Xulüe 中國古代讀藏目録敘略 [A Brief Account of Ancient Chinese Catalogues for Reading Buddhist Canons]. Wenxian 文獻 4: 225–36. [Google Scholar]