Abstract

Wang Lingguan is a significant deity in Chinese Daoist beliefs and folk worship. His belief’s formation and proliferation are rooted in specific spatial contexts. This paper introduces a spatial perspective to provide a fresh interpretation of Wang Lingguan’s belief, examining it through the lenses of ritual, temple, and geography. In Daoist rituals that bridged sacred and secular spaces, Wang Lingguan emerged as Sa Shoujian’s protector, manifesting his divine power to devotees. For the purposes of ritual simplification and spatial solidification, believers constructed Daoist Temples as emblems of sacredness and reimagined Wang Lingguan as the protector of these temples in their design. The active involvement of the Ming royal family in building Daoist Temples significantly contributed to establishing regional belief centers for Wang Lingguan. During the Qing Dynasty, although Wang Lingguan’s royal patronage waned, his belief spread across most of China, becoming more localized and secularized. The dynamic interplay of ritual, temple, and geographical factors illuminates the establishment, dissemination, and evolution of Wang Lingguan’s belief throughout China.

1. Introduction

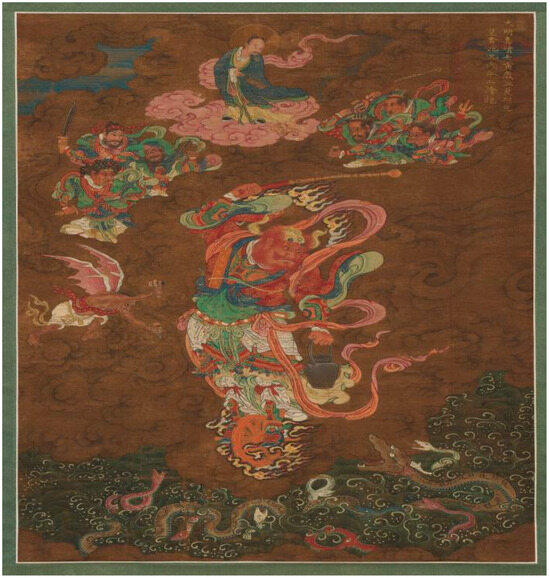

Wang Lingguan 王靈官, also known as Wang Shan 王善, Wang E 王惡, Wang Tianjun (王天君 Lord Wang), and Wang Yuanshuai (王元帥 Marshal Wang), has the status of Sanwu huoche leigong (三五火車雷公 Lord of Thunder), Yushu huofu tianjiang (玉樞火府天將 Jade Pivot Fire Mansion Heavenly General), Zhenwu dadi zuoshi (真武大帝佐使 The general of True Martial Great Emperor), Wubai Lingguan tongshuai (五百靈官統帥 Commander of the five hundred Lingguans), and other identities. In addition, he is probably better known as one of the most important protectors of Daoist temples (Figure 1). Wang Lingguan possesses a ruddy complexion, three eyes, dons armor, and wields a steel whip (Figure 2). He is tasked with judging and punishing evil, safeguarding the ordinary people between heaven and earth. Consequently, he earns admiration, with people praising him as follows: “With three eyes, he observes all affairs; with one whip, he awakens the people of the world 三眼能觀天下事,一鞭驚醒世間人”.

Figure 1.

Wang Lingguan’s statue at Baopu Daoist Temple (抱樸道院, Baopu daoyuan) Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province. Photographed by the author.

Figure 2.

Wang Lingguan’s statue at Guanghui Palace (廣惠宮 Guanghui gong), Nanxun District, Huzhou City, Zhejiang Province. Photographed by the author.

The belief in Wang Lingguan has a long and profound history in China, exerting widespread influence as a national deity within the “Stratum Accumulation” (層累 cenglei) and secularization of Daoism. Wang Lingguan has garnered extensive attention from various scholars. Li Fengmao conducted a comparative analysis of relevant texts, unveiling the crucial characteristics of Wang Lingguan’s dependence on Sa Shoujian 薩守堅, the Daoist priest of the Shenxiao Sect (神霄派 Divine Empyrean Daoism) during the Southern Song Dynasty (Li 1988, pp. 159–61). In another study, he further asserted that the ritual pairing of Ancestor Sa Shoujian and Protector Wang Lingguan could be a deliberate innovation by the newly formed Shenxiao Sect during the late Song and early Yuan Dynasties (Li 1997, p. 266). Zhang Zehong 張澤洪 offered a detailed examination of Zhou Side 周思得, a Ming Dynasty Daoist priest pivotal in promoting Wang Lingguan as a national deity (Zhang 2006, pp. 18–22). Li Lihe and Li Yuanguo further revealed the evolving relationship between the beliefs in Wang Lingguan and Daoist priests Sa Shoujian and Zhou Side (Li and Li 2021, pp. 97–111).

In addition to historical scrutiny, the religious content associated with the belief in Wang Lingguan has become a focal point of scholarly research. Florian C. Reiter paid attention to the case of the Wang Lingguan Temple at Mount Qiqu in Sichuan Province and made a detailed analysis of his identity as a protector and the characteristics of Daoist thunder spells (Reiter 1998, pp. 323–42). In addition, Yoshihiro Nijidou conducted a meticulous investigation into the category of Yuanshuai deities to which Wang Lingguan belongs (Nikaido 2006, pp. 206–16). Vincent Goossaert argued that closely related ritual techniques such as controlled spirit-possession, ritual theatre, and spirit-writing shaped the divine persona of the Wang Lingguan, and that his divine persona remained coherent in different contexts (Goossaert 2022, pp. 45–76). These discussions have laid the foundation for our research and enhanced our understanding of the beliefs surrounding Wang Lingguan. However, the method of analysis that relies solely on texts and stories leaves some important questions unresolved, such as the following:

- (1)

- How was the belief of Wang Lingguan as a guardian deity within Daoism accepted by the groups other than Daoists?

- (2)

- As a companion deity to Daoist Sa Shoujian, how did Wang Lingguan evolve into a protector deity revered by Daoist Temples nationwide?

- (3)

- Over the lengthy historical period of the Ming and the Qing Dynasties, how did the belief in Wang Lingguan evolve, and in what specific aspects did it change?

These inquiries collectively address a core question: How do secular individuals perceive and worship Wang Lingguan, the Daoist deity? The recording and depiction of the veneration of Wang Lingguan, coupled with its acceptance and spread among followers, essentially represent a concrete process through which Daoist deities manifest their sanctity in the secular world. Consequently, our analysis of the belief system surrounding Wang Lingguan could lead to a deeper investigation into the processes of its sacralization and secularization.

Following the “Spatial Turn”1 in various disciplines, the spatial analysis of religion has advanced, establishing space as a pivotal concept in understanding faith. The structural elements that constitute religious space and the socio-historical backdrop essential for spatial construction have been integrated into the research trajectories of religious scholars.2 However, it is important to note that scholars have conducted few comprehensive studies exploring the spatial aspects of belief for specific Chinese deities.3 As previously noted, the spatial relevance of Wang Lingguan, especially as a national guardian deity in Daoist temples and landscapes, has been underemphasized. Consequently, this article endeavors to adopt a spatial perspective, transcending the conventional narrative reliant on texts and stories. It aims to weave spatial elements that are in play in Daoist rituals, Daoist temples, and Daoist understandings of geography into the analytical framework, thereby offering a novel interpretation of Wang Lingguan’s belief within a dynamic spatial context.

2. Ritual: The Establishment of Divinity and the Manifestation of Belief

In the Daoist worldview, despite the clear distinction between the celestial realm (仙界 xianjie) as a sacred space and the mundane realm (凡界 fanjie) as a secular one, deities and mortals still manage to forge connections and interactions through a variety of means and intermediaries. Li Fengmao highlighted several modes of human–divine encounters during the Wei, Jin, Southern, and Northern Dynasties, including meditative resonance (冥通 mingtong), divine possession (降神 jiangshen), inadvertent entry (誤入 wuru), and purposeful quest (探訪 tanfang) (Li 2010, pp. 1–20).

As history has progressed, the methods facilitating communication between the sacred and secular realms have evolved into a complex array of rituals This corpus of ritual knowledge is perpetuated among Daoist practitioners through canonical texts and ritualistic practices and is also acknowledged and replicated by lay followers in their religious pursuits. The reverence for Wang Lingguan is entrenched in such historical and religious milieus, conforming to specific doctrinal regulations and spatial hierarchies. In the forthcoming discussion, we will explore how Wang Lingguan’s role as a protective deity is affirmed through Daoist rituals, his elevation to the sacred space, and the diverse Daoist rites through which he manifests his divine influence within the secular space.

2.1. From the Secular to the Sacred: The Ritual Establishment of Wang Lingguan’s Protector Deity

The historical accounts of Wang Lingguan’s life are somewhat ambiguous. In the Daoist “Xianjian” (Immortals’ Biographies) and the folk “SoushenJi” (In Search of the Supernatural), Wang Lingguan is associated with the legendary tales of the Daoist priest Sa Shoujian, albeit with minor variations in the narratives presented in these texts. Li Fengmao posited that these discrepancies reflect the diverse origins of the legends surrounding Wang Lingguan at the time (Li 1988, p. 159). Florian C. Reiter, in his translation of Wang Lingguan’s story, also advised readers to note the differing accounts of his tale (Reiter 1998, pp. 334–37). This paper does not aim to provide a detailed analysis of these narrative differences. Instead, it seeks to reveal a set of common spatial transformation regulations used in these stories. That is, a clear distinction is drawn between secular and sacred spaces, and bridging or communicating between these realms requires specific rituals. The spatial concepts and ritual order embedded in these stories are not only tied to the establishment and propagation of Wang Lingguan’s veneration but also reflect his followers’ consensus on the framework of their worldviews.

Before delving into the narrative of Wang Lingguan, it is crucial to elucidate the relationship between the Daoist pantheon and spatial order. Guo Wu 郭武 argues that the organization of Daoist deities primarily reflects Daoism’s conception of the cosmic structure and is additionally influenced by the hierarchical system prevalent in human society, thus establishing distinct tiers of divinity. He further clarifies the dynamic interaction between the divine system and spatial order, highlighting that Daoism includes three principal spatial dimensions: heaven, earth, and the human world. Each realm has its respective class of deities, with the most venerated residing in heaven, followed by those in the underworld, and the human world being the most subordinate layer (Guo 1995, pp. 103–15).

Diverging from the conventional narratives of mortals ascending to divinity, the texts concerning Wang Lingguan primarily illustrate the ascent of Wang Shan from being a city god (城隍 chenghuang) and temple deity (廟神 miaoshen) to a celestial figure, specifically a protector within the Thunder Division (雷部 leibu) of the heavenly realm. Wang Lingguan’s tale is intricately tied to the Daoist priest Sa Shoujian. To facilitate our analysis, we categorize their interaction into four prevalent scenarios. The first entails Sa Shoujian demolishing Wang Lingguan’s Daoist Temple. The second depicts Wang Lingguan tracking and monitoring Sa Shoujian. The third scenario unfolds with their negotiation and conciliation by the river. The concluding sequence involves Sa Shoujian endorsing Wang Lingguan to the Jade Emperor (玉帝 Yudi), the sovereign of heaven, for the role of his protective deity.

In the initial account of temple destruction, Wang Lingguan is known as Wang Shan in various texts, identified either as a City God (Zhao 1988) or a Temple Deity (Qin 1990). According to Shi Yanfeng and Zhang Xingfa’s deity classification, both roles are considered the lowest echelons of earthly deities (Shi 2008, pp. 187–88; Zhang 2001, p. 60), intimately linked with secular space and dwelling in tangible temples. Displeased with Daoist priest Sa Shoujian residing in his temple, City God Wang Shan resorts to dreams to communicate with local officials, urging them to oust Sa Shoujian, who subsequently employs Daoist magic to incinerate the temple. In a different narrative, the Temple Deity Wang Shan’s abode is also set ablaze by Sa Shoujian, but this act is provoked by Wang Shan’s grievous consumption of young children, a misdeed uncovered by Sa Shoujian.

The narratives underscore spatial order in two respects: firstly, Wang Shan’s abode distinctly manifests as a secular space, accessible to individuals like Sa Shoujian or officials. For instance, it is noted that when the temple is set aflame, “the fire did not spread to the common people’s homes” (Zhao 1988, vol. 4), signifying the temple’s location within a populated area and its secular nature. Secondly, in terms of spatial norms, although both the City God and Temple Deity are considered lower-tier terrestrial spirits with their temples situated within the secular realm, they maintain their sacred status and do not directly interact with Daoist priests or laypeople. The City God Wang Shan communicates solely through dreams to officials, and while the Temple Deity Wang Shan rebukes Sa Shoujian for the temple’s arson, he does not manifest physically. These subtleties confirm that even deities associated with secular spaces observe specific spatial protocols.

In the second narrative, the City God Wang Shan appeals to the Jade Emperor (the sovereign of the sacred realm) to censure Sa Shoujian’s actions and acquires the authority to investigate Sa Shoujian, as well as an axe intended for his potential punishment Conversely, in another account, the Temple Deity Wang Shan, constrained by his own misdeeds, refrains from confronting the Jade Emperor and opts to clandestinely track Sa Shoujian, biding his time for retribution. This episode reveals that, under specific conditions, the City God can traverse from the secular to the sacred domain, present his case to the Jade Emperor, and obtain a degree of empowerment. Similarly, the Temple Deity appears to possess analogous abilities but refrains from utilizing them for personal reasons. In the tales, City God Wang Shan covertly follows Sa Shoujian for three years, and Temple Deity Wang Shan for twelve, yet neither manages to find any misdoing on Sa Shoujian’s part or engages in direct interactions with him within the secular sphere.

The third episode unfolds by the river, where City God Wang Shan materializes and clarifies the genesis of his conflict with Sa Shoujian (Figure 3). Impressed by Sa Shoujian’s esteemed character after careful observation and evaluation, Wang Shan expresses his readiness to comply with his directives and serve as his protective deity. The situation with Temple Deity Wang Shan slightly diverges; Sa Shoujian, having amassed considerable merit and potent divine powers, has earned a position in the celestial court of the sacred realm. Unable to exact vengeance, Temple Deity Wang Shan eventually resorts to negotiation with Sa Shoujian. Like City God Wang Shan, Temple Deity Wang Shan aspires to accompany Sa Shoujian into the sacred realm, thereby also offering to become his protective deity. In this story, the river acts as a pivotal spatial metaphor, mirroring unique presences. Thus, it is by the river that Sa Shoujian initially discerns the divine essence of Wang Shan in the mundane world and engages him directly.

Figure 3.

Wang Shan and Sa Shoujian. Sanjiao Yuanliu Shengdi Foshuai Soushen Daquan.4

In the concluding episode, Sa Shoujian presents the situation of City God Wang Shan to the Jade Emperor in the sacred realm and nominates him as his protective deity. In another narrative, due to the Temple Deity’s previous misconduct, Sa Shoujian only forwards his nomination to the Jade Emperor after receiving an oath of allegiance from the Temple Deity. Notably, in this episode, the Temple Deity Wang Shan expressly states, “The true man’s accomplishments are eminent, and he is appointed to the Heavenly Pivot” (Qin 1990, p. 518), which refers to a position within the celestial court of the sacred realm. Daoists, by accumulating merit and virtue through their cultivation, may ascend or be transformed to serve in the sacred realm. Sa Shoujian exemplifies this path. As recorded in the texts, both City God Wang Shan and Temple Deity Wang Shan ultimately succeed in becoming protective deities for Sa Shoujian, thereby earning their places in the sacred realm as well.

Overall, despite variations in narrative details, both the City God and the Temple Deity adhere to the stringent hierarchical order and spatial regulations amongst deities. Importantly, Wang Shan’s transition from a lower-tier deity in the secular realm to an elevated protective deity in the sacred realm is significantly influenced by the endorsement of Daoist priest Sa Shoujian. This endorsement fundamentally involves Sa Shoujian conducting Daoist rituals that bridge the two realms. Within the corpus of Daoist ritualistic knowledge, Daoist priests can create ephemeral conduits to the sacred realm within secular spaces through the arrangement of altars, the crafting of talismans, the utterance of incantations, and other methods. Once established, these conduits allow the priests to write and send special petitions to the celestial court, thereby communicating their requests to the deities in the sacred realm.

In the narrative texts about Wang Lingguan, the descriptions of communication rituals are notably succinct, only mentioning Sa Shoujian’s actions of “petitioning the Jade Emperor” and “recommending as a divisional general”. This conciseness is typical in discussing communication rituals because these divine biographies are more concerned with elucidating the origins and stories of the deities than detailing the complexities of Daoist rituals. There are specific Daoist texts that provide detailed accounts of these communication rituals with the sacred realm. We will delve into these rituals more comprehensively in the next section. However, before we do so, it is vital to emphasize the significance of the narrative texts pertaining to Wang Lingguan.

The aforementioned Daoist and folk narrative texts corroborate that Wang Lingguan accomplished the transition between two realms and solidified his status as a protective deity through the communication rituals led by Daoist priest Sa Shoujian. In essence, the narrative texts reveal that both the Daoist community and the lay public abide by a unified set of spatial orders and ceremonial rules. This widespread agreement establishes the fundamental logic for Wang Lingguan’s subsequent manifestations of sanctity within the secular sphere.

2.2. From the Sacred to the Secular: The Ritual Manifestation of Wang Lingguan’s Divine Power

As Sa Shoujian’s sect spread, Wang Lingguan evolved into a prominent figure within Daoist veneration and garnered exceptional popularity among the Ming dynasty’s royal family. A pivotal contributor to the widespread veneration of Wang Lingguan was the Hangzhou Daoist priest Zhou Side. The Xuande Emperor notably referenced Zhou Side and the ascent of Daoist exorcism of Lingguan (靈官法 Lingguan fa) in Imperial Inscription of the Dade Daoist Temple (御製大德觀碑 Yuzhi Dadeguan bei). This inscription details the following:

The Daoist priest Zhou Side garnered widespread fame in the capital for his profound understanding of Wang Yuanshuai’s incantations. Known as Wang Lingguan, this Yuanshuai is a celebrated general of the celestial realm. Renowned for his efficacy, Wang Lingguan is universally responsive to supplicants and possesses the uncanny ability to predict disasters, with all his prophecies invariably coming true. My ancestor, Emperor Yongle, commissioned multiple verifications of these forecasts, all of which were remarkably accurate. Wang Lingguan is particularly proficient in banishing evils and eradicating plagues. Responding to his divine prowess, Emperor Yongle ordered Zhou Side to construct a Daoist Temple west of the imperial palace dedicated to Wang Lingguan. Subsequent to Emperor Yongle, the rituals and ordinances for worshiping Wang Lingguan were officially integrated into the state’s codified laws.(Shen 1982, vol. 18, pp. 196–97)

According to Qingxi Mangao (青溪漫稿 The Qingxi Manuscript), Ni Yue 倪岳, a scholar from the Ming dynasty, elucidated that Zhou Side’s Lingguan fa essentially encompasses possessing the body and responding to supplications, described as “spiritual possession and prayer response” (Ni 2019, p. 192). Specifically, Zhou Side’s performance of possession rituals aligns with the “Transfiguration and Invocation of Generals” as delineated in the “Leiting Sanwu Huoche Lingguan Wangyuanshuai Mifa (雷霆三五火車靈官王元帥秘法 Esoteric Methods of Wang Lingguan)”.

Based on the ritual texts of Mifa, we can delineate Zhou Side’s specific ritual practices. Initially, Zhou Side constructs a “Lei Tan” 雷壇, an altar essential for ritual execution. As John Lagerwey has elucidated, Daoist altars extend beyond mere tables, encompassing the entire space designated for the ritual (Lagerwey 1987, p. 25). The altar serves as an intermediary space bridging the secular and the sacred, a nexus of the two realms. Upon preparing the altar, Zhou Side employs distinctive Daoist hand gestures to connect with the divine realm. He positions his left hand before his heart with the “Yuwenjue” (玉文决 “The Yuwen Gesture”) and his right hand wields the “Jianjue” (剑决 “The Sword Gesture”) at his waist, all while chanting heavenly decrees. During these rituals, Zhou Side immerses himself in meditation, intuitively feeling the presence of the celestial deities.

Upon establishing a connection with the deities of heaven, Zhou Side proceeds to burn incense (焚香 fenxiang), invoking the presence of Wang Lingguan from the divine realm. The ascending smoke serves as a conduit, transmitting messages from the earthly domain to the celestial court. To prevent miscommunication with unintended deities, Zhou Side summons designated divine messengers to oversee and ensure the accuracy of the invocation. The texts include directives such as “Command the altar’s marshals to swiftly open the heavenly gates” and “As the messenger of Gongcao are present, kindly convey this sincere offering of incense to the Thunder Mansion, and urgently call Wang Shan to the altar for this summoning”. The descriptions of burning incense and the summoning process vividly illustrate the demarcation between the mundane and sacred realms and the operational traces of the ritual.

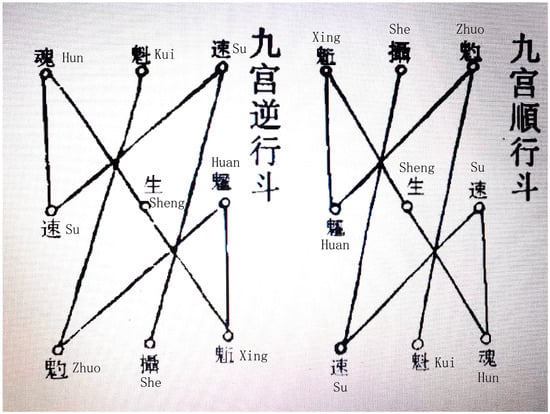

Zhou Side served as a conduit, immersing himself in meditative concentration (存思 cunsi) and empathetic resonance (通神 tongshen). During the communication rituals, with the internal echo of thunder, Wang Lingguan, donned in armor and brandishing a golden whip, effectively connected with Zhou Side. To enable Wang Lingguan’s descent from the divine realm into the earthly domain and to possess him, Zhou Side, besides holding the seal and articulating spells, also moved in the distinctive Daoist pattern that emulates the celestial bodies’ motions (步斗踏罡 budou tagang) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Daoist patterns emulating the orbit of stars and constellations, including nine palaces in sequential order dipper (九宫顺行斗 jiugong shunxing dou) and nine palaces in reverse sequence dipper (九宫逆行斗 jiugong nixing dou). Sourced from Leiting Sanwu Huoche Lingguan Wangyuanshuai Mifa.

Following a sequence of intricate rituals, Wang Lingguan accomplished his sacred manifestation in the secular realm, as documented: “The marshal approaches the altar, offerings of incense and lamps are made. Briefly wielding his thunderous authority, he assumes command of the prayers” (Anonymous 1988, pp. 488–92). This passage signifies that Wang Lingguan is now prepared to answer prayers within the earthly domain. It is important to note that in invoking Wang Lingguan’s divine powers for blessings or exorcisms in the mundane world, Zhou Side continues to employ incantations, talismans (including those penned in blood), and other Daoist ceremonial elements.

Analyzing the esoteric texts reveals that Zhou Side’s linkage with Wang Lingguan is dependent on a series of rituals that facilitate the interplay between the divine and earthly realms, aspects often omitted in Sa Shoujian’s narratives. Nonetheless, there is no fundamental difference between the communications of Sa Shoujian with the Jade Emperor and Zhou Side with Wang Lingguan. Both the narrative and esoteric texts, overtly or covertly, demonstrate that there are distinct demarcations between the celestial and the mortal, and these realms are governed by structured rules and order. Adherence to specific Daoist rituals is imperative for bridging and communicating across these distinct spaces. For Wang Lingguan, it is through such Daoist communication rituals that he solidifies his protective deity status and manifests his divine influence within the interplay of the secular and sacred realms. The tales of Sa Shoujian and Zhou Side underscore that these elaborate spatial communication rituals are predominantly understood and practiced by Daoists across various ages.

3. Daoist Temple: Ritual Reproduction and Imagery Shaping

Daoist Temples serve as pivotal locations for the divine presence in the secular world and as vital conduits for expressing faith. For adherents of Wang Lingguan, the architectural design of these temples represents more than just a ritualistic depiction of his origin story; it is also a significant method for evolving and reshaping the representation of their beliefs.

3.1. Ritual Simplification and Spatial Solidification

While Daoist priest Zhou Side can proficiently summon Wang Lingguan through ritualistic creation of sacred spaces, the Daoist Thunder technique necessitates considerable personal spiritual development and involves complex and specialized rituals beyond the scope of ordinary individuals. Consequently, a simplified ritual utilizing the deity’s statue has been employed to embody Wang Lingguan’s sanctity in the mundane world. Wang Lingguan’s effigy first emerged during Emperor Yongle’s campaigns in the Ming Dynasty. Yehangchuan 夜航船 (The Night Boat) details that “Emperor Yongle obtained a rattan statue of Wang Lingguan in the East Sea. He devoutly worshipped and prayed to it continuously, and it accompanied him on all military expeditions. On reaching the Jinchuan River 金川河 in one campaign, the statue grew inexplicably heavy, rendering it immovable. In a private consultation, Zhou Side informed the Emperor that the Jade Emperor had decreed the war’s boundary, and even Wang Lingguan must adhere to this celestial limit; thus, the campaign was destined to conclude there” (Zhang 2020, vol. 14, p. 499).

Observing Emperor Yongle’s devout veneration and his insistence on carrying the rattan image of Wang Lingguan during military expeditions underscores a reliance on the sacred space manifested through this venerated object. The rattan effigy as a miraculous symbol effectively manifested its scope of influence within the mundane world. The “unmovability” of the image during the Yuchuan campaign and Zhou Side’s explanation that “the divine has its bounds” both highlight Wang Lingguan’s delimited presence in the secular realm. While Zhou Side’s possession ritual signifies a personal conduit for Wang Lingguan’s transition from the divine to the earthly realm, Emperor Yongle’s cherished rattan image symbolizes a material medium for such transformation. Although both methods exalt Wang Lingguan’s sanctity, the latter not only facilitates ease of worship but also solidifies a more stable representation of the sacred in the spread of belief.

In his Zhuchuang Suibi 竹窗隨筆 (Random Notes by Bamboo Window), the late Ming Buddhist Master Lianchi 蓮池大師 recorded an instance where a soul attained liberation by “regularly venerating the image of Wang Lingguan at his bedside” (Zhu 2013, p. 20). Similarly, in Lu Can’s 陸燦 Gengsi Bian 庚巳编 (Gengsi Compilation) from the Ming era, Daoist Zhang Bixu 張碧虛 provided a remedy for villagers plagued by malevolent forces by “advising them to welcome the worshipped image of Wang Lingguan into their homes for consecration” (Lu 1987, vol. 6, p. 65). These accounts demonstrate that during the Ming dynasty, the effigy of Wang Lingguan was revered by both the clergy of Buddhism and Daoism, as well as the laity, as a miraculous object capable of creating a protective and potent sacred space. While Daoist practice involves intricate rituals and divine summoning, the simplicity and accessibility of sacred images raise the issue of ensuring their spiritual potency. In the Collected Commentary on Gao Shang Yuhuang Ben Xing Jing (高上玉皇本行經集註 Gao Shang Yuhuang Ben Xing Jing Jizhu), Quanzhen Daoist Zhou Xuanzhen 周玄貞, speaking through Wang Lingguan, introduced a chanting technique predicated on “aligning one’s heart” (心合 xinhe) with the divine:

Why need skillful hands to depict my likeness when all I desire is for your heart to resonate with mine? When one’s heart resonates with the divine, virtue and blessings proliferate, signifying the true recitation of benevolence. The remainder entails diligent scripture recitation, mindful speech, and disciplined contemplation. While long-term reverence and faith yield merits and blessings, their significance is contingent upon the extent of inherent goodness, thereby ranking secondary.(Zhou 2004, vol. 1, p. 332)

While aligning one’s heart with the divine through scripture recitation safeguards faith’s purity, it undeniably demands greater cultural proficiency from devotees and acknowledges the inherent limitations of individual spiritual practices. Consequently, the optimal strategy involves establishing a permanent sanctuary for the divine effigy and engaging Daoist priests in consistent scriptural chants, spiritual cultivation, and reverent incense offerings, thus ensuring the sacred space’s sanctity. This method is more palatable to lay believers, leading to the widespread construction of Daoist Temples venerating Wang Lingguan across the country post the Ming dynasty.

3.2. The Reproduction of Rituals in the Daoist Temple Layout

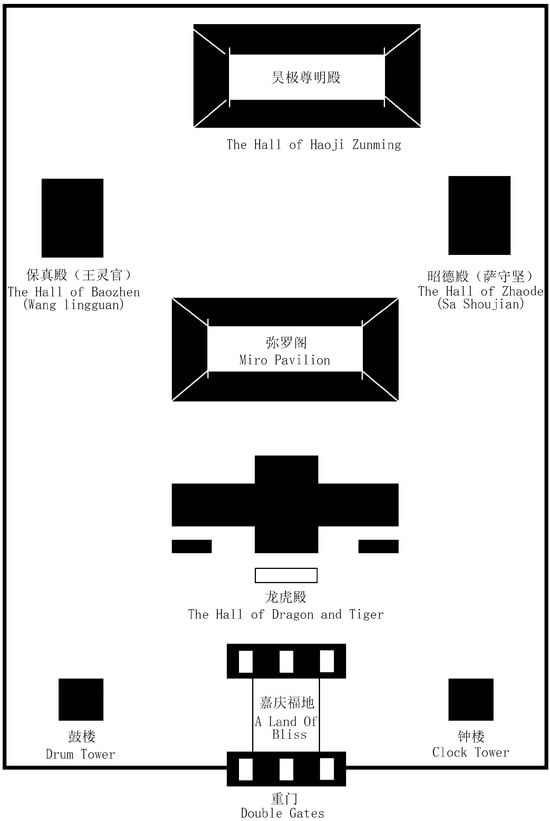

As the most influential adherent among Wang Lingguan’s followers during the Ming Dynasty, Emperor Yongle’s devotion was evident not only through his daily worship of Wang Lingguan’s statue but also in the establishment of a Daoist temple in the capital expressly for him, thereby creating a lasting sacred space for the deity. Ming Shi 明史 (The Dynastic History of the Ming) notes that during the Yongle era, attributed to Zhou Side’s proficiency in transmitting the Lingguan method, Heavenly general Temple (天將廟 Tianjiang miao) and the Patriarch Hall (祖師殿 Zushi dian) were constructed west of the Forbidden City (Zhang 1974, vol. 50, p. 1309). While specific details of Tianjiang Temple’s interior are not provided in the records, under the auspices of five emperors from Yongle to Jingtai, Zhou Side led several expansions of the temple. Notably, Emperor Xuande’s transformation of Tianjiang Temple into Dade Daoist Temple included extensive modifications to the architectural design, offering valuable insights into the early architectural manifestations of Wang Lingguan Daoist temples. The Imperial Inscription of the Dade Daoist Temple details the following:

Since my ascension to the throne, the divine power of Wang Lingguan has become unmistakably prominent. The capital, teeming with a vast population, witnesses people devoutly coming to worship from dawn till dusk, overwhelming the capacity of the original Daoist Temple. Consequently, I decreed the expansion and renovation of the Daoist Temple. The refurbished Daoist Temple stands resplendent and awe-inspiring, adorned with solemn and imposing divine statues. At its zenith is the Jade Emperor Pavilion, a tribute to Daoism’s roots. Adjacent to it, the Patriarch Hall provides insight into the deep lineage and history of Daoism. Flanking the Daoist Temple are the clock and drum towers to the east and west, establishing a rhythmic sanctity, while dual-layered main gates at the forefront mitigate the worldly clamor. Encircled by tranquil cloisters, the Daoist Temple’s grandeur exudes a peaceful aura. These architectural enhancements have transformed the abode of the divine, elevating its sanctity and reverence. Consequently, I have aptly renamed this Daoist Temple as the Dade Daoist Temple.(Shen 1982, vol. 18, p. 197)

According to its description, the Dade Daoist Temple largely retained the Tianjiang Temple’s structure while introducing a new pavilion dedicated to the Jade Emperor. It effectively established a complex sacred space where the three deities—the Jade Emperor, Sa Shoujian, and Wang Lingguan—coexisted, adhering to an intrinsic logic of “sectarian lineage”. In early narratives, Sa Shoujian is depicted engaging with the Jade Emperor in the sacred realm via Daoist rituals. Following Sa Shoujian’s endorsement and the Jade Emperor’s sanction, Wang Lingguan underwent a pivotal transformation, culminating in his elevation as a protective deity. The architectural enhancements undertaken by Emperor Xuande thus represent a comprehensive reenactment of the entire ritual narrative chronicled in the tales of Wang Lingguan, illustrating the profound integration of ritualistic elements into the spatial configuration of the Daoist Temple.

Post-Xuande, the Dade Daoist Temple underwent two additional reconstructions during the Chenghua and Jiajing periods of the Ming Dynasty. According to Dijing jingwulue (帝京景物略 Scenery of the Imperial Capital), authored by Liu Dong 劉侗 and Yu Yizheng 于奕正, “At the onset of the Chenghua period, the emperor commanded the officials to expand the Dade Daoist Temple, renaming it the Palace of Dade Jingling 大德景靈宮, and to erect the Miro Pavilion (弥罗阁 miluo ge) for deity worship” (Liu and Yu 2001, vol. 4, pp. 260–61). The new Miluo Pavilion served a similar purpose to the Jade Emperor Pavilion, resulting in minimal changes to the spatial layout. During the Jiajing period, as the records of the Imperial Tablet of the Palace of Dade Jingling (御製大德景靈宫碑 Yuzhi Dade jinglinggong bei), new additions included the Hall of Haoji Zunming 昊极尊明殿 dedicated to the Jade Emperor’s parents and the Hall of Dragon and Tiger (龙虎殿 Longhu dian) dedicated to Zhenwu 真武 (Shen 1982, vol. 18, pp. 197–98). Clearly, the Daoist Temple incorporated some elements not present in the original rituals. Nonetheless, the Miro Pavilion for the Jade Emperor and the Halls of Baozhen 保真殿 and Zhaode 昭德殿 dedicated to Wang Lingguan and Sa Shoujian, respectively, still preserved evident markers of ritual reproduction as depicted in the narrative texts (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Wang Lingguan and Sa Shoujian were worshiped in the left and right halls, respectively. Drawn according to the text.

3.3. The Shaping of Imagery through the Daoist Temple Layout

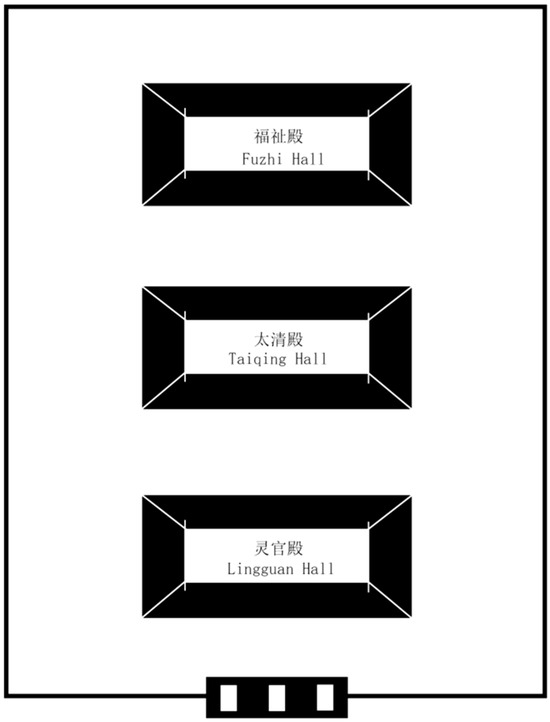

Distinct from reproducing textual rituals in the architectural layout of the Dade Daoist Temple, the spatial configurations of other Daoist temples played a significant role in shaping the imagery of Wang Lingguan. Notably, the positioning of the Lingguan Hall within the Daoist Temple’s layout was instrumental in crafting the image of the temple guardian. In reality, beyond the Dade Daoist Temple, other Daoist temples venerating Wang Lingguan during the early Ming Dynasty typically lacked a dedicated area for worshipping Sa Shoujian. Instead, these Daoist temples often erected a distinct Lingguan Hall prominently at the forefront of the central axis, specifically to honor Wang Lingguan.

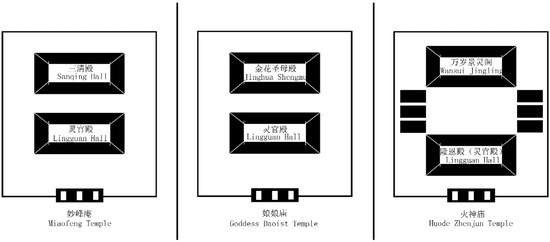

The architectural design of such Daoist temples was still associated with Zhou Side, renowned for his mastery of Wang Lingguan’s Mifa. In the 10th year of the Zhengtong era (1445), when Zhou Side sought retirement at the age of 86, Emperor Zhengtong specifically ordered the establishment of the Taiqing Daoist Temple 太清觀 on Fenghuang Mountain5 to serve as his retirement abode (Xi 1998, vol. 19, pp. 175–76). According to the Encyclopedia of Beijing—Mentougou Volume (北京百科全書·門頭溝卷 Beijing Baikequanshu—Mentougoujuan)—the Daoist Temple housed three main halls: the first being Lingguan Hall dedicated to the Daoist protector Wang Lingguan, the second Taiqing Hall to the Supreme Venerable Sovereign (太上老君 Taishang Laojun), and the third Fuzhi Hall 福祉殿 to Zhenwu and the emperor (Beijing Encyclopedia Editorial Committee 2001, p. 288). Notably, Taiqing lacked a hall for Sa Shoujian, placing the Lingguan Hall prominently at the Daoist Temple’s forefront (Figure 6). Approximately a decade later, in 1456, Beijing’s renowned Baiyun Daoist Temple 白雲觀 also established a Lingguan Hall (Li 2003, p. 72). Although Zhou Side had passed, it was his disciples who continued constructing Lingguan Halls (Koyanagi 1934, pp. 105–12). This suggests that the spatial organization of Lingguan Hall and its role in delineating Wang Lingguan’s imagery as a Daoist protector were significantly influenced by Zhou Side and his Daoist lineage.

Figure 6.

The spatial layout of the Taiqing Daoist Temple, with the Lingguan Hall at the forefront. Drawn according to the text.

While it is difficult to ascertain the precise number of Daoist temple layouts influenced by Zhou Side and his disciples, the image of Wang Lingguan as a Daoist temple protector became increasingly standardized in the late Ming Dynasty as the Lingguan Hall gained prominence. For example, during the Jiajing period of the Ming Dynasty, the Miaofeng Temple 妙峰庵 in the capital had only two halls, yet one was dedicated to Wang Lingguan. Similarly, the Goddess Daoist Temple (娘娘廟 Niangniang miao) constructed in Tongzhou 通州 during the same period primarily venerated the Goddess of Birth, but prominently featured the Lingguan Hall in its first courtyard. Furthermore, the Lingguan Hall had also become a critical component of the spatial layout in the Huode Zhenjun Daoist Temple (火德真君廟 the god of fire), dedicated to the god of fire, within the capital (Figure 7). These instances illustrate the pervasive influence and establishment of Wang Lingguan’s guardian role across various Daoist temples.

Figure 7.

The Lingguan Hall is located at the forefront of the various temples. Drawn according to the text.

Turning our attention to areas far from the Ming capital, the Wudang Mountain 武當山 was renowned for the Zhenwu Daoist Temple. Shen Defu 沈德符, a prominent writer of the late Ming Dynasty, mentioned that Lingguan Hall was a ubiquitous presence throughout the Wudang Mountain (Shen 1959, vol. 4, p. 917). Similarly, Zhang Dai 張岱 recorded that the sound of Wang Lingguan’s whip, akin to thunderbolts, was a common occurrence on Mount Qiyun 齊雲山 in Anhui Province (Zhang 2020, vol. 2, p. 82). Consequently, irrespective of whether the primary deities were the Jade Emperor, Zhenwu, the Goddess, the God of Fire, or others, the imagery of Wang Lingguan as the protector of Daoist temples had transcended the textual deity system and become more dependent on the representation within Lingguan Hall and its spatial positioning in the temple. Intriguingly, Pan Lun’en 潘綸恩 of the Qing Dynasty once remarked the following:

Maitreya (韋陀 Weituo) serves as the guardian of Buddhist temples, while Wang Lingguan fulfills the same role for Daoist temples. Commonly referred to as Linguan Yuanshuai (靈官元帥 Marshal Lingguan) by the faithful, Wang Lingguan stands out as the most remarkable among all the divine marvels I’ve encountered. Interestingly, Mount Jiuhua 九華山, known as the spiritual center of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva (地藏菩薩 Dizang pusa), inexplicably features Wang Lingguan as the sentinel at Buddhism’s threshold. This mountain is a constant hub of devotion, with a ceaseless influx of pilgrims throughout the year, and the tales of Wang Lingguan’s miraculous deeds there are innumerable.(Pan 1998, vol. 12, p. 266)

The passage above demonstrates that during the Qing Dynasty, not only did Daoist temples prominently feature Wang Lingguan as their guardian, but there were also instances where Buddhist temples, such as those found at Mount Jiuhua, incorporated spatial layouts that positioned Wang Lingguan as the guardian of their mountain gates. Consequently, the adage “If you want to ascend a mountain, pay homage to Wang Lingguan first” truly reflected the widespread recognition of Wang Lingguan as the guardian of temples among the people.

4. Geography: Spatial Dissemination and Expansion of Belief

The Daoist Temple serves as Wang Lingguan’s residence during his transition from the sacred to the secular space, and it also stands as a significant symbol of the dissemination of his belief within the secular community. Examining the construction of Daoist temples from a geographical perspective not only offers insights into the spatial distribution of belief propagation but also enables us to discern specific long-term changes in the dissemination of these belief.

4.1. The Core Area of Wang Lingguan’s Belief in Ming Dynasty

As previously noted, the Daoist temple, serving both as a ritual simplification and a means of spatial solidification, became a pivotal mode of worship for followers of Wang Lingguan. As his cult spread, the construction of dedicated Daoist temples to Wang Lingguan proliferated within secular society. It is important to recognize that during the Ming Dynasty, the establishment of Daoist temples necessitated imperial approval to be deemed legitimate.6 Temples erected without such sanction not only lacked protection but also faced the imminent threat of demolition. Thus, the early Ming Dynasty’s construction of Daoist temples honoring Wang Lingguan was closely intertwined with the patronage of the Ming imperial family and the intervention of influential figures.

Yongle Emperor established the Tianjiang Temple in Beijing, marking the first palace dedicated to Wang Lingguan. Successive emperors, including Xuande and Chenghua, renamed and expanded it into the Dade Daoist Temple 大德觀 and Dade Jingling Palace, respectively, heralding an era of flourishing for the Daoist temple. From its inception as the Tianjiang Temple to its evolution into the Palace of Dade Jingling, it served fundamentally as an imperial sanctuary, essentially the royal inner shrine. Xu Youzhen 徐有貞 of the Ming Dynasty highlighted that the shrine of Dade was the state’s secret shrine (Xu 1987, vol. 3, p. 116). Beyond the Palace of Dade Jingling, the Jiajing Emperor also established the Hall of Qin’an 欽安殿 within the Imperial City to honor Zhenwu. Wang Lingguan, recognized as one of the twelve Thunder Generals, was also depicted in the murals of this hall (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Mural of Wang Lingguan in the Hall of Qin’an. Located in the Forbidden City, Beijing (Tao 2015).

Fueled by the devotion of Ming emperors, their consorts, Daoist priests, eunuchs, and vassal kings intimately linked with the royal court, an early community of believers emerged, significantly bolstering the cult of Wang Lingguan. The Metropolitan Museum of Art houses a Ming Dynasty portrait of Wang Lingguan (Figure 9), wherein a line of small script documents the following: “On the first day of April in the 21st year of the Jiajing era, Imperial Consort Shen commissioned this painting 大明嘉靖壬寅歲孟夏朔旦, 皇貴妃沈氏命畫工繪施”. This inscription underscores the deep influence of Wang Lingguan’s belief even among the concubines of Emperor Jiajing.

Figure 9.

Wang Lingguan’s portrait collected by the Metropolitan Museum of New York, USA.

Beyond the Xuande Emperor and his consorts endorsing Wang Lingguan’s belief, Zhou Side, the Daoist priest at the helm of the royal secret shrines, managed Daoist institutions and mentored a multitude of disciples during the Ming Dynasty. These disciples were instrumental in constructing Lingguan Halls within Daoist temples across the capital, including Taiqing Daoist Temple, Guandi Daoist Temple 關帝廟, and Huode Zhenjun Daoist Temple. Consequently, given the quantity of Daoist temples and their intimate ties with the imperial court, the capital was arguably the epicenter for constructing Wang Lingguan’s Daoist temples during the Ming Dynasty and served as the principal hub for revering Wang Lingguan.

Nanjing, another capital during the Ming Dynasty, also constructed a shrine devoted to Wang Lingguan relatively early. The Tablet Record of the Lingying Temple (靈應觀碑略 Lingyingguan beilue) notes: “In the southwest of the capital lies a mountain known as Mount Wulongtan 烏龍潭山… In the spring of the 7th year of Xuande, the grand commandant eunuch of Nanjing (南京守備太監 Nanjing shoubei taijian), Luo, erected a shrine dedicated to Wang Lingguan on the mountain’s east side” (Ge 2011, vol. 2, p. 48). The epitaph of Luo Zhi 羅智 elaborates that the emperor entrusted him with the governance of Nanjing. Known for his diligence and proficiency, especially in engineering and construction, Luo Zhi personally oversaw the building of tombs, temples, and city walls wherever needed (Zhou 1999, pp. 135–43). As a supervisory eunuch closely connected to the emperor, Luo Zhi’s initiative to construct Wang Lingguan’s shrine in Nanjing was essentially a manifestation of the emperor’s devoutness towards Wang Lingguan.

The palaces in the Wudang Mountains shared a similar stature as the secret shrines in the capital and Nanjing. Influenced by the Yongle Emperor’s reverence for Zhenwu and Wang Lingguan, Daoist temples constructed in the Wudang Mountains during his reign included statues of Wang Lingguan. Notably, a bronze statue crafted in the Yongle period still stands in the Yuanhe Daoist Temple 元和觀. Given its significance as a site for royal prayers and ceremonies, the Wudang Mountains garnered attention from successive Ming Dynasty emperors. Consequently, it received numerous statues and scrolls of Wang Lingguan from these emperors, establishing itself as another regional hub for the veneration of the deity.

Hangzhou, the hometown of Zhou Side, became another focal point for establishing Wang Lingguan’s shrines following his retirement. As Tian Rucheng 田汝成 of the Ming Dynasty recorded, “During the Chenghua period, Zhou Side’s disciple, Chang Daoheng 昌道亨, found favor with the emperor. By imperial decree, Xuanyuan Daoist Temple 玄元觀 was relocated next to Zhou Side’s tomb, transforming his former residence into Baoji Daoist Temple 寶極觀” (Tian 1958, vol. 21, p. 268). The rebranded Baoji Temple featured Yousheng Hall 佑聖殿 at its center, Chong’en Hall 崇恩殿 to the left, Long’en Hall 隆恩殿 to the right, Taiqing Pavilion 太清閣 at the rear, and the Hall of the Four Generals (四聖殿 Sisheng dian) at the front (Shen 1979, vol. 11, pp. 722–23). Long’en Hall and Chong’en Hall were designated for Wang Lingguan and Sa Shoujian, evidently inspired by the Dade Daoist Temple’s layout in the capital. Chang Daoheng’s title as “the spiritual master of Dade Xianling” further underscores Baoji Daoist Temple’s strong connection to the Palace of Dade Jingling in the capital.

During the Ming Dynasty, vassal kings were proactive in constructing Daoist temples that enshrined Wang Lingguan. Notably, the Jingjiang Prince, stationed in Guangxi Province, was a prominent vassal king who established the Lingguan Shrine on Duxiu Peak 獨秀峰 within his domain (Wang 1990, vol. 16, p. 7). This shrine, situated within the prince’s residence, served as his private sanctuary, underscoring the significance of Wang Lingguan’s cult to him. Moreover, owing to the Yongle Emperor’s fusion of Wang Lingguan and Zhenwu beliefs, halls and statues dedicated to Wang Lingguan became staples in Zhenwu Daoist Temples. Consequently, local vassals’ contributions to Zhenwu Daoist Temples often encompassed reverence for Wang Lingguan. Richard G. Wang’s study indicates that there were as many as 22 Zhenwu Daoist Temples sponsored by vassal kings during the Ming Dynasty, representing the most prevalent form of Daoist Temple in their religious practices (Richard 2012, p. 84). This trend demonstrates that their devotional patterns closely mirrored those of the emperors.

With the Ming emperors’ endorsement of Daoism, the worship of Wang Lingguan permeated all societal strata. The widespread folk tales about Wang Lingguan significantly accelerated this process, leading ordinary individuals to erect their own temples and shrines in his honor. The Ming Dynasty novel The Journey to the North (北遊記 Beiyouji), dating from the Jiajing period, recounts the mythical tale of Wang Lingguan. Initially, his temple was destroyed by Sa Shoujian, but he was later subdued by the God of Zhenwu and became one of his celestial generals (Yu 1994, pp. 208–20). Another well-known epic, Journey to the West (西遊記 Xiyouji), elaborates on Wang Lingguan’s role as Zhenwu’s envoy in a confrontation with the Monkey King at the Lingxiao Palace (Wu 2014, p. 94). Similar narratives are echoed in folk literature like Curse of Jujube Records (薩真人咒棗記 Sa Zhenren Zhouzaoji) (Deng 1994, pp. 83–91) and Summary of Romantic History (情史類略 Qingshi Leilue) (Feng 1984, vol. 9, p. 261), reflecting the extensive reach and influence of Wang Lingguan’s legend across various layers of society.

The widespread portrayal of Wang Lingguan in various art forms significantly resonated with the public, propelling the establishment of Wang Lingguan’s Daoist Temples across different locales. For instance, the Gazetteer of Yuanshi County in Zhending Prefecture of the Chongzhen Era (崇禎) 直隸真定府元氏縣志 mentioned “Laowanggou” 老王溝 as a place named after a local Wang Lingguan Temple (Zhao and Hu 2000, vol. 1, p. 261). Similarly, the Records of the Newly Built Qingshan Xinggong (新建靑山行宮記 Xinjian Qingshan Xinggong Ji) from 1629 describes a newly erected temple in Cao County, Heze City, Shandong Province, featuring a Guanyin Hall (觀音殿 Mercy Goddess Hall), Fumo Daoist Temple (伏魔觀 Demon Suppression Temple), Shengdi Shrine (聖帝祠 The Shrine of the Holy Emperor), and a Wang Lingguan Hall (Chen and Pei 2004, vol. 17, pp. 482–83). Unlike in Beijing or Nanjing, the proliferation of Wang Lingguan Daoist temples in these regions was largely supported by local gentry and villagers. This expansion signifies the broadening appeal and recognition of Wang Lingguan’s cult during the late Ming Dynasty, reflecting a shift in the demographic and geographic spread of his worship.

4.2. The Regional Diffusion of Wang Lingguan’s Belief in Qing Dynasty

Unlike the Ming Dynasty, where the royal family, including emperors, consorts, eunuchs, and vassal kings, constituted a significant belief community centered around Wang Lingguan, the imperial families of the Qing Dynasty were less focused on venerating the deity. They did not construct Daoist Temples and palaces dedicated to him as extensively as their predecessors. However, following the widespread acceptance of Wang Lingguan in the post-Ming era, his imagery became firmly entrenched among the populace. Subsequent records in local chronicles and customs notes7 increasingly referenced Wang Lingguan’s Daoist temples and halls (Table 1). By examining the distribution of these sacred sites, we gain insight into the geographical breadth and depth of Wang Lingguan’s worship during the Qing Dynasty, indicating a continuation and evolution of his veneration beyond the confines of imperial patronage.

Table 1.

Statistics of Wang Lingguan’s Palaces and Temples in Qing Dynasty.

The Qing Dynasty’s adherence to Wang Lingguan’s belief was geographically extensive, spanning from Jilin 吉林 in the northeast to Yunnan 雲南 in the southwest, and from Qinghai 青海 in the northwest to Taiwan 臺灣 in the southeast, with temples and halls dedicated to him established across the nation. This widespread veneration marks a significant departure from the Ming Dynasty, where worship was predominantly centralized in regional hubs like Beijing and Nanjing. The historical records may not fully document the rise and fall of numerous Lingguan temples within civil society, and given the common practice of housing Wang Lingguan statues within other Daoist temples, the actual territorial reach of his cult is likely even broader than archival materials suggest. This expansive distribution underscores the depth and spread of Wang Lingguan’s belief throughout the country during the Qing period.

After the Qing Dynasty, the belief in Wang Lingguan continued to spread widely, increasingly incorporating regional legends and narratives, thus demonstrating its localization and secularization. For instance, Tianfu Palace 天符宫 in Jianli County 監利縣, Hubei Province, was once dedicated to the Heavenly Talisman Great Emperor (天符大帝 Tianfu Dadi) and Wang Lingguan. Tianfu Dadi was one of the Jade Emperor’s civil ministers, while Wang Lingguan served as a guardian deity of the Heavenly Court and a martial general of the Jade Emperor. Locally, Wang Lingguan was revered as a fusion of a Buddhist Bodhisattva and a secular king (王爺菩薩 Wangye pusa) (Xi 2015, p. 33). Another illustration is the belief in Princess of the Azure Clouds (碧霞元君 Bixia Yuanjun), prevalent in the Mount Tai 泰山 area of Shandong Province, where local legends narrate that Wang Lingguan, as the guardian deity, split the mountain with his whip to create a path for the faithful (Liang et al. 1996, p. 39). Additionally, in the Fujian region, Wang Lingguan’s origin story was adapted to align with local historical and cultural contexts. As a result, in Fujian, he has been associated with various identities, including a pirate, a butcher, and even as the son of Geng Jingzhong 耿精忠, the king of Yunnan (Zhuang 2015, pp. 17–19). These adaptations highlight the diverse, localized, and secular interpretations of Wang Lingguan’s identity and role in various communities post-Qing dynasty.

Generally, throughout the Qing Dynasty, the belief in Wang Lingguan across different regions increasingly exhibited typical traits of localization and secularization. This adaptability, or the characteristic of “changing with the customs,” played a crucial role in the sustained and widespread propagation of the belief, even after it ceased to receive the full endorsement of the royal family as it had previously. This adaptability reflects the dynamic nature of the belief in Wang Lingguan, allowing it to evolve and resonate with diverse communities and cultural contexts over time.

5. Conclusions

The spatial interpretation of Wang Lingguan’s belief vividly demonstrates the dynamic interplay between ritual, Daoist Temple, and geography. This analysis emphasizes the role of spatial concepts and diverse communities in embodying and sustaining Daoist beliefs and divine worship. Notably, while the content of narrative and ritual texts about Wang Lingguan varies to cater to different audiences, they consistently adhere to established divine hierarchies and spatial boundaries. The Daoist priesthood, proficient in this belief system, commands specialized rituals that effectively bridge and communicate with the divine realm. Through the ritual practices conducted by Daoist priests such as Sa Shoujian and Zhou Side, Wang Lingguan established his role as a guardian deity and manifested his divine authority to the believers.

To mitigate the complexities of Daoist rituals, the community of believers led by the Ming Dynasty emperors embraced a strategy of ritual simplification and spatial solidification, which involved positioning statues of Wang Lingguan within Daoist temples. Initially, the layout of these temples was a ritualistic reproduction of Wang Lingguan’s textual image. As the belief spread and temple construction increased, Wang Lingguan gradually moved beyond his textual pairing with Sa Shoujian and was singularly positioned at the front of temples. This spatial placement, functioning as a form of “welcoming and safeguarding,” reshaped Wang Lingguan’s role and image, allowing him to be freely integrated into various Daoist temples of differing faiths, including those of Zhenwu, Taishang Laojun, and the Fire God. Consequently, Wang Lingguan eventually evolved into a guardian deity of Daoist temples nationwide, and formed a stereotypical image similar to that of the Buddhist Vedanta.

The geographical spread of Wang Lingguan’s Daoist temples demonstrates the evolving and widespread nature of his belief across regions. Unlike the Ming Dynasty, where the royal family extensively promoted Wang Lingguan’s belief, the Qing Dynasty’s imperial family did not actively engage in fostering this faith. Consequently, the Ming Dynasty’s politically influenced regional centers like Beijing, Nanjing, Hangzhou, and Wudang Mountain did not maintain their prominence during the Qing era. Instead, as belief in Wang Lingguan became ingrained in the populace, the Qing period witnessed a grassroots spread of this faith, leading to its gradual prevalence across the majority of the nation. This development highlighted the belief’s adaptability, showing significant trends towards decentralization, localization, and secularization.

In conclusion, the establishment, dissemination, and evolution of Wang Lingguan’s belief are more clearly illustrated through a spatial perspective composed of rituals, Daoist temples, and geography. This research reveals that there are structural factors in the interaction between religious beliefs and socio-cultural processes, the relationships between which can be further understood and utilized.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.H.; methodology, Z.H.; validation, Z.H. and X.M.; formal analysis, Z.H. and X.M.; investigation, X.M.; resources, X.M. and Z.H.; writing—original draft preparation, X.M. and Z.H.; writing—review and editing, Z.H. and X.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The main data are derived from local gazetteers and field research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For studies on the spatial turn, one may refer to the following: (Warf and Arias 2008). |

| 2 | For insights into the application and critical reflection of spatial theory, the following references may be consulted: (Knott 2005; Kilde 2014). |

| 3 | The following scholars have made recent academic contributions by utilizing spatial theory to analyze the phenomena of religious belief in China, which may serve as useful reference materials: such as Yiwei Pan, Weiqiao Wang and Yu Han, see (Pan and Yan 2021; Wang and Yan 2023; Han 2023). |

| 4 | Wang Shan and Sa Shoujian were negotiating and communicating by the river. Anonymous. Sanjiao Yuanliu Shengdi Foshuai Soushen Daquan三教源流聖帝佛帥搜神大全 (The Complete Collection of Holy Emperors, Buddhas, and Taoist Masters in the Origins of the Three Religions). Xiyue tianzhuguo cangban. Published in the Qing Dynasty. https://old.shuge.org/ebook/san-jiao-yuan-liu-sou-shen-da-quan/ accessed on 3 February 2024. |

| 5 | Scholars have different views on where the Taiqing Daoist Temple was located. Chen Wenlong 陳文龍 and Zheng Hengbi 鄭衡泌, after examining the evidence, believe that Zhou Side’s Taiqing Daoist Temple was located in Beijing’s Fenghuang Mountain, not Hangzhou (Chen and Zheng 2015). |

| 6 | In 1391, Hongwu Emperor of the Ming Dynasty ordered that “All nunneries and temples that did not comply with the amount previously set by the state should be demolished”. Anonymous. 2005. Ming Shilu明實錄 (The Veritable Records of the Ming Dynasty). Volume 2. Beijing: Xianzhuang Shuju, p. 250. Yongle Emperor and Zhengtong Emperor of the Ming Dynasty also issued similar edicts prohibiting the construction of private temples. |

| 7 | Listed in the table are some of the palaces and temples related to Wang Lingguan’s beliefs that have been verified through palace remains or oral interviews on the basis of documentary records. Due to the historical changes of the palaces and temples, the lack of textual records, and the fact that folk deities were often worshipped together in the same place, the actual geographic distribution of Wang Lingguan’s beliefs in the Qing Dynasty should be more extensive than the information contained in the table. |

References

- Anonymous. 1988. Leiting Sanwu Huoche Lingguan Wangyuanshuai Mifa 雷霆三五火車靈官王元帥秘法. In Zhengtong Daozang 正統道藏 (The Zhengtong Daoist Canon). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian, Tianjin: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe, vol. 30, pp. 488–92. [Google Scholar]

- Beijing Encyclopedia Editorial Committee. 2001. Beijing Baikequanshu—Mentougoujuan 北京百科全書·門頭溝卷 (Beijing Encyclopedia—Mentougou Volume). Beijing: Olympic Chubanshe, p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Siliang 陳嗣良, and Jinghu Pei 裴景煦 [清]. 2004. Xinjian Qingshan Xinggong Ji 新建靑山行宮記 (Records of the Newly Built Qingshan Xinggong). In Guangxu Caoxianzhi (光緒) 曹縣志 (Cao County Gazetteer of the Guangxu Era). Nanjing: Fenghuang Chubanshe, pp. 482–83. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Wenlong, and Hengbi Zheng. 2015. The Zhou Side-Doctrine School and the Daoist Records Division of the Ming Dynasty. World Religion Studies 4: 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Zhimo 鄧誌謨 [明]. 1994. Feijianji and Zhouzaoji Erzhong 飛劍記、咒棗記二種 (Flying Sword Records and Curse of Jujube Records). Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe, pp. 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Menglong 馮夢龍 [明]. 1984. Qingshi Leilue 情史類略 (Summary of Romantic History). Changsha: Yuelu Shushe, p. 261. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Yiliang 葛寅亮 [明]. 2011. Jinling Xuanguanzhi 金陵玄觀志 (Chronicle of the Daoist Temple in Jinling). Nanjing: Nanjing Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Goossaert, Vincent. 2022. Ritual Techniques for Creating a Divine Persona in Late Imperial China: The Case of Daoist Law Enforcer Lord Wang. Journal of Chinese Religions 50: 45–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Wu 郭武. 1995. On the Structure and Significance of the Daoist Deities System 論道教神仙體系的結構及其意義. In Daojiao Wenhua Yanjiu 道 教文化研究 (Daoist Culture Studies). Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe, vol. 7, pp. 103–15. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Yu. 2023. Spatial Study of Folk Religion: “The Direction of Xishen” (喜神方) as a Case Study. Religions 14: 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilde, Jeanne Halgren. 2014. Approaching religious space: An overview of theories, methods, and challenges in religious studies. Religion and Theology 20: 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, Kim. 2005. Spatial Theory and Method for the Study of Religion. Temenos—Nordic Journal for the Study of Religion 41: 153–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyanagi, Jikita 小柳司氣太. 1934. Baiyunguan Zhi:fu Dongyuemiao Zhi 白雲觀志: 附東嶽廟志 (Chronicle of the Baiyun Daoist Temple with a Chronicle of the Dongyue Temple). Tokyo: Tokyo Research Institute of the Institute of Oriental Culture, pp. 105–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lagerwey, John. 1987. Taoist Ritual in Chinese Society and History. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fengmao 李豐楙. 1988. A study on Deng Zhimo’s Sazhenren Zhouzaoji 鄧志謨⟪薩真人咒棗記⟫研究. Hanxue Yanjiu 漢學研究 (Studies in Sinology) 6: 159–61. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fengmao 李豐楙. 1997. Sa Shoujian and Wang Lingguan’s Leifa and Jiyou—An Examination from Song to Ming 薩守堅、王靈官的雷法與濟幽——從宋到明的考察. In Xu Xun and Sa Shoujian: A Study of Deng Zhimo’s Daoist Novels 許遜與薩守堅—鄧志謨道教小說研究. Taipei: Taiwan Student Book Company, p. 266. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fengmao 李豐楙. 2010. Xianjing yu Youli: Shenxian Shijie de Xiangxiang 仙境與遊歷:神仙世界的想像 (Immortal Land and Traveling: The Image of the Immortal World). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Lihe 李黎鶴, and Yuanguo Li 李遠國. 2021. From Sa Shoujian to Wang Lingguan—A few points on the Shenxiao sect 從薩守堅到王靈官——關於神霄派的幾點考辨. Laozi Xuekan 老子學刊 (Journal of Laozi) 2: 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yangzheng 李養正. 2003. Xinbian Baiyunguan Zhi 新編白雲觀志 (New Edition of the Baiyun Temple Chronicle). Beijing: Zongjiao Wenhua Chubanshe, p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Xingchen 梁興晨, Ying Wu 武鷹, and Yanhui Wang 王延輝. 1996. Taishan Fengwu Chuanshuo 泰山風物傳說 (Legends of Mount Tai’s Scenery). Beijing: Huayi Chubanshe, p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Dong 劉侗, and Yizheng Yu 于奕正 [明]. 2001. Dijing Jingwulue 帝京景物略 (A Brief Account of the Imperial Capital's Scenery). Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe, pp. 260–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Ch’ung 陸粲 [明]. 1987. Gengsi Bian 庚巳編 (Gengsi Compilation). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Mount Jiuhua Editorial Committee 九華山編輯委員會. 1990. Jiuhuashan Zhi 九華山志 (Record of Mount Jiuhua). Hefei: Huangshan Shushe, p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Yue 倪岳 [明]. 2019. Qingxi Mangao 青溪漫稿 (The Qingxi Manuscript). Hangzhou: Zhejiang Guji Chubanshe, p. 192. [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido, Yoshihiro 二階堂善弘. 2006. The Transformation of the Marshal God in Daoism and Folk Beliefs 道教・民間信仰における元帥神の変容. Osaka: Kansai University Press, pp. 206–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Lun’en 潘綸恩 [清]. 1998. Daoting Tushuo 道聽途說 (The Hearsay). Hefei: Huangshan Shushe, p. 266. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Yiwei 潘逸煒, and Aibin Yan 閆愛賓. 2021. Legends, Inspirations and Space: Landscape Sacralization of the Sacred Site Mount Putuo. Religions 12: 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Zijin 秦子晉 [元]. 1990. Xinbian Lianxiang Soushen Guangji 新編連相搜神廣記 (Newly compiled records of Lianxiang's collection of deities). In Huitu Sanjiao Yuanliu Soushen Daquan 繪圖三教源流搜神大全 (Drawings of the Three Religions and Their Sources and Streams of Searching for Deities). Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe, p. 518. [Google Scholar]

- Reiter, Florian C. 1998. Some Notices on the “Magic Agent Wang” (Wang ling-kuan) at Mt. Ch’i-ch’ü in Tzu-t’ung District, Szechwan Province. Zeitschrift Der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 148: 323–42. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, G. Wang. 2012. Ming Prince and Daoism: Institutional Patronage of an Elite. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Bang 沈榜 [明]. 1982. Wanshu Zaji 宛署雜記 (Wanping County Miscellany). Beijing: Beijing Guji Chubanshe, pp. 197–98. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Chaoxuan 沈朝宣 [明]. 1979. Jiajing Renhe Xianzhi 嘉靖仁和縣志 (Renhe County Gazetteer of the Jiajing Era). In Zhongguo Fangzhi Chongshu 中國方志叢書 (The Chinese Gazetteers Series). Taipei: Cheng Wen Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Defu 沈德符 [明]. 1959. Wanli Ye Huo Bian 萬曆野獲編 (In Unofficial Gleanings of the Wanli Era). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, p. 917. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Yanfeng 石衍豐. 2008. The Collection of the Nameless: Shi Yanfeng’s Religious Research Essays 無名集: 石衍豐宗教研究論稿. Chengdu: Bashu Shushe, pp. 187–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Jin 陶金. 2015. Qin’an relics: Song Huizong’s jade slips and paintings of twelve thunder generals in the Qin’an Hall 欽安遺珍—欽安殿藏宋徽宗玉簡與十二雷將神像畫. Forbidden City 5: 66–81. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Rucheng 田汝成 [明]. 1958. Xihu Youlan Zhi 西湖遊覽志 (Records of Visiting West Lake). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, p. 268. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Sen 汪森 [清]. 1990. Guangxi Fanfeng Zhi 廣西藩封志 (A chronicle of the division of the feudal lords of Guangxi). In Yuexi Wen Zai 粵西文載 (Collected Works of Guangxi Literature). Nanning: Guangxi Renmin Chubanshe, p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Weiqiao 王偉僑, and Aibin Yan 閆愛賓. 2023. Body, Scale, and Space:Study on the Spatial Construction of Mogao Cave 254. Religions 14: 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warf, Barney, and Santa Arias, eds. 2008. Spatial Turn. Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Oxfordshire: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Cheng’en 吳承恩 [明]. 2014. Journey to the West 西遊記 (Xiyouji). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, Jing 習經 [明]. 1998. Xunle Xi Xiansheng Wenji 尋樂習先生文集 (The Collected Works of Jing Xi). In Sikuquanshu Cunmu Congshu Bubian 四庫全書存目叢書補編 (Supplement to the Collectanea of the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries, Books Not Included). Jinan: Qilu Shushe, vol. 97, pp. 175–76. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, Shanxin 習善新. 2015. Lishishang de Jianli Tianfumiao 歷史上的監利天府廟 (History of the Temple of Tianfu in Jianli). China Taoism 中國道教 5: 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Youzhen 徐有貞 [明]. 1987. Zeng Taichang Boshi Gu Weijin Xu 贈太常博士顧惟謹序 (Preface to Dr. Gu Weijin). Wugongji 武功集. In Wenyuange Sikuquanshu 文淵閣四庫全書 (Wenyuan Pavilion Edition of the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries). Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe, p. 116. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Xiangdou 余象鬥 [明]. 1994. Zushi Henan Shou Wang E 祖師河南收王惡 (The Ancestor Master subdued Wang E in Henan). In Beifang Zhenwu Zushi Xuantian Shangdi Chushen Zhizhuan 北方真武祖師玄天上帝出身志傳 (Biography of theTrue Martial Great Emperor). Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe, pp. 208–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Dai 張岱 [明]. 2020. Yehangchuan 夜航船 (The Night Boat). Hangzhou: Zhejiang Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Tingyu 張廷玉 [清]. 1974. Ming Shi 明史 (The Dynastic History of the Ming). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, p. 1309. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xingfa 張興發. 2001. Daojiao Shenxian Xinyang 道教神仙信仰 (Daoist Immortal Beliefs). Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe, p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Zehong 張澤洪. 2006. The Daoist priest Zhou Side of the Ming Dynasty and the Theurgy of Lingguan 明代道士周思得與靈官法. Zhongguo Daojiao 中國道教 (China Taoism) 3: 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Daoyi 趙道一 [元]. 1988. Lishi Zhenxian Tidao Tongjian Xubian 歷世真仙體道通鑒續編 (Continued Records of Daoist Practice through True Immortals Across the Ages). In Zhengtong Daozang 正統道藏 (The Zhengtong Daoist Canon). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian, Tianjin: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Wenlian 趙文濂, and Yue Hu 胡岳 [明]. 2000. Chongzhen Zhili Zhendingfu Yuanshi Xianzhi (崇禎)直隷真定府元氏縣志 (Gazetteer of Yuanshi County in Zhending Prefecture of the Chongzhen Era). In National Library of China Local History and Genealogy Documentation Centre: Selected Chronicles of the Ming Dynasty 明代孤本方志選 (Mingdai Guben Fangzhi Xuan). Beijing: National Library of China Document Microcopy Reproduction Centre, p. 261. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Xuanzhen 周玄真 [明]. 2004. Gao Shang Yuhuang Ben Xing Jing Jizhu 高上玉皇本行經集註 (The Collected Commentary on Gao Shang Yuhuang Ben Xing Jing). In Zhonghua Daozang 中華道藏 (The Daoist Canon of China). Beijing: Huaxia Chubanshe, vol. 6, p. 332. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Yuxing 周裕興. 1999. The Eunuch System of the Ming Dynasty as Seen from the Unearthed Tombstones in Nanjing 由南京地區出土墓誌看明代宦官制度. Ming Qing Luncong 明清論叢 (A Collection of Essays on the Ming and Qing Dynasties) 1: 135–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Hong 袾宏 [明]. 2013. Pingxin Jian Wang 平心薦亡 (A thought of fairness can save the souls of the dead). In Zhuchuang Suibi 竹窗隨筆 (Random Notes by Bamboo Window). Shanghai: East China Normal University Chubanshe, p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Hengkai 莊恒愷. 2015. The localisation of Daoist Deities from the Legend of Wang Tianjun in Mindi 從閩地王天君傳說看道教神祇的本地化. Journal of Changchun Engineering College (Social Science Edition) 長春工程學院學報 (社會科學版) 3: 17–19. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).