Abstract

Investigating the later stages of life, this study aims to outline a specific personal context shaped during this phase, approached from various perspectives: theological, medical, psychological, and social, each highlighting distinct challenges. Theologically, the focus is on the afterlife and preparation for meeting the Righteous Judge. Medically, the emphasis is on health deterioration, culminating in the cessation of bodily existence. Psychologically, the study mentions the decline in cognitive functions, anxiety, and depression. Social aspects include isolation, marginalization, adaptation to change, and the loss of loved ones. Considering the impact of these factors on human life, this research examines to what extent the Sacrament of Communion, from an Orthodox perspective, offers answers to all these challenges. Based on a qualitative research method (content/thematic analysis) of liturgical texts using MAXQDA software, the study focuses on the prayers preceding and following this Sacrament. It highlights the complex nature of the Sacrament of Communion, its multiple faces, and its extended benefits, as well as the risks of partaking without proper preparation. The results provide arguments for the significance the Orthodox Church grants to the mystical union between man and God in the Sacrament of Communion, also emphasizing the importance of an authentic spiritual life.

1. Introduction

Elderhood represents an existential constancy, often ignored by young people, misunderstood by adults, and later experienced with profound personal impact among the elderly. Despite all the challenges, many find ways to embrace their senior years by adapting to new lifestyles and finding joy in quieter moments. The key to aging beautifully lies in balancing several aspects—accepting the normality of growing old, bravely facing its challenges, and taking advantage of all the help you find. The “graying” of populations around the world also presents unique challenges. By 2030, all baby boomers will be older than 65, significantly altering the demographic composition of societies. This demographic shift is expected to slow population growth, age the population considerably, and lead to a more racially and ethnically diverse population (Lazzara 2020).

In recent decades, the global demographic landscape has undergone a significant shift, with an increase in the elderly population becoming a universal trend across all regions and countries (United Nations 2019; Bloom et al. 2015). This phenomenon is especially pronounced in Europe and Northern America, where the aging population is growing at a notably faster rate compared to other parts of the world. While regions like Latin America, Asia, and even Sub-Saharan Africa are also experiencing this shift, the extent and impact of aging are most substantial in the Western world (Secretary-General of the UN 2014; Nations Unies 2014). This demographic transition is primarily attributed to factors such as increased life expectancy, declining birth rates, and improved healthcare, all of which have contributed to a notable expansion of what is often termed the ‘third age’ (Su et al. 2023; Aburto et al. 2020). This syntagm represents the stage of life characterized by retirement and post-retirement years, typically spanning from the mid-60s onwards. It is marked by a period of reduced work-related commitments and greater leisure time. While this extended lifespan is undoubtedly a result of advances in healthcare and overall living standards (Hao et al. 2020; Li et al. 2018; Crimmins 2015), it also brings forth a set of unique challenges that affect nations, communities, and individuals as well. One of the foremost challenges associated with the ‘third age’ are the issues of healthcare and eldercare. As individuals age, they often require increased medical attention and long-term care, straining healthcare systems and resources. This poses a significant economic burden on governments and families alike, necessitating comprehensive strategies for providing quality healthcare and support services to the elderly (McMaughan et al. 2020). At the same time, social isolation and mental health issues among the elderly also become pertinent concerns in the ‘third age’. As individuals transition from active work lives to retirement, they may experience feelings of loneliness and a loss of purpose (Fakoya et al. 2020). Addressing these sociological and psychological aspects is crucial for maintaining a high quality of life during the ‘third age’.

Europe is also experiencing a significant demographic change marked by an aging population. As of 2022, the median age in Europe was 44.4 years, meaning half of the population was older than this age. The variance in median age among EU countries is notable, with Italy having the highest at 48 years and Cyprus the lowest at 38.3 years (Eurostat 2023). This aging trend is more pronounced among women, with a higher proportion of older women compared to men. In 2019, for every man aged 65 or older, there were 1.33 women in the same age group in the EU-27, a ratio expected to decrease to 1.24 by 2050. The old-age dependency ratio is also increasing. By 2050, it is projected that there will be fewer than two working-age individuals for each person over 65, a significant change from the 34.1% ratio in 2019. This demographic shift has substantial implications, especially for healthcare and pension systems. Additionally, life expectancy is on the rise, with projections suggesting it will reach 84.6 years for men and 89.1 years for women by 2060 (Eurostat 2020). In the context of the significant demographic changes mentioned in Europe, studying the “third age” phenomenon is essential. Understanding these challenges is crucial for developing effective strategies for the elderly. The interplay of increased susceptibility to diseases, physical fragility, and mental health deterioration and an approach to the end of life requires a compassionate and comprehensive approach to healthcare and support for the elderly. To address the multifaceted nature of this particular stage, a comprehensive approach is required, which includes, at a minimum, perspectives from medical, social, psychological, and theological domains. Moreover, this holistic approach not only recognizes the inherent complexity of the aging process but also provides a more dignified and compassionate framework for comprehending and assisting individuals as they confront the distinctive challenges and opportunities of the ‘third age’.

The primary objective of our study is to identify and analyze the challenges that accompany the ‘third age’, through a comprehensive review of relevant literature. This research aims to neutrally explore the possible impact of engagement in religious practices, particularly the Sacrament of Communion, on the aging process. We intend to investigate the relationship between an active spiritual life, marked by participation in Communion, and the aging experience, assessing both positive contributions and other possible outcomes in different areas (medical, psychological, sociological, and theological). The study will examine how religious involvement might provide resilience and support to older individuals while also considering a range of effects on their well-being. Given the significant role of religion in many lives, our analysis will aim to objectively assess its benefits and limitations, thereby contributing to a more nuanced understanding of religious involvement in navigating the challenges of the third age. By highlighting the diverse roles of religiosity and religious practices, we seek to foster a balanced and empathetic approach to aging. Ultimately, this research aspires to offer insights that can inform and guide support strategies for the elderly, ensuring that the study encompasses a broad spectrum of perspectives on the influence of religious practices during this critical phase of life.

1.1. Medical Perspectives

Late adulthood, a critical phase of the human lifespan, is marked by a unique set of health challenges. This period is characterized by increased vulnerability to diseases, due to a natural decline in the body’s immune response, making older adults more susceptible to both acute and chronic illnesses. Recent studies provide substantial evidence of this increased vulnerability (Lopez and Piedra 2022; Mori 2020). As people age, their physiological resilience declines, making their bodies less capable of recovering from illnesses or enduring various medical treatments. This decreased resilience is a crucial factor in the overall health profile of the elderly. Furthermore, the concept of fragility, or physical weakness, is another significant hallmark of this life stage. Factors contributing to this fragility include diminished muscle mass, reduced bone density, and decreased physical endurance (Estebsari et al. 2020; Kornadt et al. 2020). This fragility not only increases the risk of injuries, like fractures from falls, but also complicates the recovery process.

Mental health issues in late adulthood, such as cognitive decline and increased risk of mental health conditions like depression, anxiety, and dementia, are of significant concern. The National Institute of Mental Health in the US highlights the importance of taking care of mental health as people age, noting that life changes such as coping with a serious illness or losing a loved one can impact mental health, leading to conditions like depression and anxiety. Effective treatment options are available to help older adults manage their mental health and improve their quality of life (NIMH 2023). A study exploring cognitive failures in old age, which focused on the effects of social context on cognitive failures during late adulthood while controlling for depressive symptoms, revealed that depressive symptoms were significantly correlated with cognitive failures. This indicates the profound influence of mental health on cognitive functioning. Furthermore, the study emphasized the role of social context in shaping cognitive experiences in late adulthood, underscoring the importance of considering both mental health and social factors in understanding and addressing cognitive decline (Hitchcott et al. 2017). Similarly, a decline in cognitive functions such as memory, attention, and problem-solving abilities in late adulthood, and the consequent rise in mental health conditions were highlighted by other studies (Carpenter et al. 2022; Palgi et al. 2021; Kyriazis 2020). This intersection of cognitive decline and mental health challenges in late adulthood underscores the need for a holistic approach to elder care, one that encompasses mental health support, social engagement, and cognitive stimulation.

The inevitability of mortality is a significant aspect of late adulthood. The culmination of various health challenges, along with the natural decline in bodily functions, leads to an increased mortality rate in this age group (Mao et al. 2022; Maresova et al. 2019). Therefore, understanding and managing death and dying become crucial components of healthcare and support for individuals in their third age. This comprehensive perspective on the challenges of late adulthood emphasizes the need for a multidisciplinary approach to addressing the health needs of the elderly. It involves not just medical interventions, but also psychological, social, and even environmental considerations. As the population continues to age, these insights become increasingly relevant for healthcare providers, policymakers, and researchers in gerontology. The goal is to not only extend lifespan but also enhance the quality of life in the later years, ensuring that the elderly live their final years with dignity, comfort, and a sense of fulfillment.

1.2. Sociological Viewpoint

From a sociological standpoint, aging and elderhood are profoundly influenced by social elements, encompassing the roles, relationships, and societal status of older individuals. Researchers have delved into the dynamics of intergenerational relationships and the crucial social support systems for this demographic (Bengtson et al. 2000). Notably, the concept of ageism, as introduced by Butler in 1969, emphasizes the discrimination older adults face, manifested through social exclusion, workplace bias, restricted access to healthcare, and the undervaluation of their societal contributions (Butler 1969). Beyond the traditional demographic changes associated with aging populations, ageism is a complex phenomenon intertwined with cultural and societal values. Addressing ageism requires considering both demographic factors and cultural dimensions within a society (Ng and Lim-Soh 2021).

While ageism significantly affects the societal roles and perceptions of older adults, another critical aspect that emerges in this context is the issue of loneliness. This emotional state, deeply entwined with social dynamics, further elucidates the complexities faced by the elderly. Studies illustrate the multifaceted nature of elderly loneliness, shaped by a lifetime of social interactions and significantly impacting day-to-day life and existential well-being (Graneheim and Lundman 2010). Another study highlights the influence of age on loneliness, noting its potential to accelerate age-related physiological decline (Hawkley and Cacioppo 2007). Further research shows the increase in loneliness in later years is attributed more to rising disabilities and declining social integration than to aging itself (Jylhä 2004). Additional research underlines the importance of considering both personal and spousal health in understanding loneliness, revealing notable gender differences in its experience (Korporaal et al. 2008).

In today’s society, the marginalization of the elderly is a pressing issue, marked by their systematic exclusion from various societal sectors, including social, economic, and cultural realms. This marginalization, which extends beyond ageist attitudes, indicates deeper systemic flaws. Marginalization in sociology is defined as the relegation of certain groups to society’s fringes, hindering their access to vital resources and opportunities for well-being. This often results in older adults experiencing reduced social engagement, weakened financial independence, and limited healthcare access. Studies have demonstrated that older adults frequently encounter barriers to social inclusion due to prevalent stereotypes and prejudices, thereby exacerbating their isolation (Carlson et al. 2020; Dionigi 2015). In healthcare contexts, older individuals frequently encounter age-based discrimination, impacting the quality and accessibility of their medical care (Doty et al. 2022).

The marginalization of older adults, encompassing limited social engagement and restricted access to resources, highlights the broader sociological challenges within our contemporary society. This observation compels us to consider aging as not just a biological process but as a multifaceted social phenomenon deeply ingrained in the cultural, economic, and structural fabric of our communities. Addressing the challenges faced by the elderly requires concerted efforts from all societal sectors, fostering an inclusive environment that recognizes and supports the elderly’s valuable contributions.

1.3. Psychological Insights

The psychological landscape of aging is both complex and profound, making it a subject of major interest in the field of psychology. As previously discussed, this period in a person’s life is marked by significant medical and social challenges. Physical frailty, increased prevalence of diseases, and the nearing presence of mortality are critical aspects that shape the elderly’s experience. Complementing these are the societal issues of marginalization and social isolation, which are equally impactful. Thus, aging emerges as a multifaceted stage of life (Tornstam 2005; Erikson 1994). From a psychological standpoint, old age is far more than a mere decline; it represents a multifaceted stage replete with unique opportunities and inherent challenges (Carstensen 2021; Cumming et al. 1960). This period of life demands deep understanding and empathy, focusing on emotional well-being and existential satisfaction (Carstensen 2021; Baltes and Baltes 1990).

The emotional experiences of older adults can be profound, characterized by a search for fulfillment and joy amidst physical and social changes. Adaptation plays a crucial role during this stage (Tornstam 2005; Cumming et al. 1960), particularly in terms of adjusting to altered social roles and relationships (Erikson 1994). This adaptation is not just about managing losses or changes but is also about discovering new ways to engage, contribute, and find meaning. Furthermore, aging must be recognized as a continuous developmental process. It presents avenues for ongoing personal development, learning, and introspection. This perspective reshapes our understanding of aging, viewing it not as a static phase but as a time rich with potential for continued development (Tornstam 2005; Baltes and Baltes 1990), the pursuit of new interests, and the acquisition of wisdom.

One of the most common and significant psychological challenges faced by the elderly is anxiety. This is a complex issue that modern psychology has increasingly recognized as crucial. This demographic, often sidelined in mental health discourse, confronts unique challenges that significantly influence both the prevalence and effects of anxiety. Despite their high incidence, anxiety disorders in the elderly are frequently underdiagnosed or undertreated, particularly when compared to conditions like depression. The overlap of anxiety symptoms with other age-related health issues contributes to this underdiagnosis, leading to a lack of proper recognition and management. Elderly individuals often display physical symptoms, such as gastrointestinal or cardiac issues, which can be misconstrued as purely medical problems, thereby complicating accurate diagnosis and delaying appropriate treatment (Kim 2020). The roots of anxiety in the elderly are diverse, spanning from health complications and the emotional toll of losing a life partner to social isolation, cognitive decline, and changes in socio-economic status (National Institute on Aging 2019). These elements collectively heighten the risk and severity of anxiety disorders in this age group. Older adults may suffer from a variety of anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorders, specific phobias, and social anxiety disorder, each necessitating distinct approaches to treatment and care. The impact of anxiety on their quality of life is profound, affecting their physical health, disrupting sleep and social interactions, and hampering their ability to adapt to the aging process (Ribeiro et al. 2020; De Beurs et al. 1999).

Another major and frequent challenge of later life is the complexity of depression among the elderly, a condition deeply understood in modern psychology. Often underdiagnosed or inadequately treated, depression in older adults is one of the most prevalent mental health issues in this age group (Zenebe et al. 2021). The underdiagnosis largely stems from a common misinterpretation of symptoms, which are sometimes mistaken as part of the natural aging process or misconstrued as other medical conditions. In elderly individuals, the manifestation of depression can differ significantly from that in younger people. Rather than displaying overt sadness, older adults are more prone to experiencing physical symptoms like fatigue, pain, or digestive issues, complicating the task of accurate diagnosis and effective treatment. The risk factors for depression in the elderly are multifaceted, encompassing social isolation, the loss of a spouse, chronic health conditions, functional decline, and shifts in socioeconomic status. These factors can considerably influence the onset and exacerbation of depression in this demographic (Fiske et al. 2009; Gottfries 1998). Moreover, depression in older adults often co-occurs with other medical conditions, such as heart disease and diabetes, further impacting their overall health (Birk et al. 2019; Windle and Windle 2013). This comorbidity highlights the necessity for a comprehensive approach to care and management. Crucially, social support and engagement in activities play a vital role in preventing and treating depression among the elderly, enhancing their life quality, and mitigating depressive symptoms (Lee et al. 2022; Zhu and Chou 2022; Bulut 2019).

Cognitive decline is also a notable challenge in the third age, marked by a gradual deterioration in cognitive abilities, including memory, problem-solving skills, and executive functions. This decline is more than just occasional forgetfulness; it can significantly impact daily living, decision making, and independence in older adults (Murman 2015). Such cognitive changes are not only a natural part of aging but can also be accelerated by various factors like chronic health conditions, lifestyle choices, and genetic predisposition (Röhr et al. 2022; John L. Woodard et al. 2012). This decline can range from mild cognitive impairment, which only slightly affects daily activities, to more severe forms like dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Understanding and addressing cognitive decline is essential in elderly care, as it plays a crucial role in maintaining the overall quality of life and independence for older individuals.

1.4. Theological Reflections

Dementia is often perceived as a dramatic and irreversible deterioration of cognitive functions. However, it has also been described as “a journey from the mind to the heart,” highlighting a profound transition beyond mere cognitive decline (Dementia and the Eucharist—Growing Old Grace—Fully 2024). This condition raises significant questions regarding the administration of the Eucharist to believers, especially considering the prerequisite of Confession for adults and elders. The authenticity of confessions from individuals with dementia, who may lack complete self-awareness or a clear memory of their actions, becomes a topic of meditation.

The Church’s stance on this matter is deeply rooted in the dichotomous nature of humanity as outlined in Scripture and by the Church Fathers, emphasizing the inseparable psychosomatic union of the material body and the immaterial soul. It suggests that when an interior member, such as the brain, is impaired, it is not the nature of the soul that is compromised, but rather the functions performed through these organs (Larchet 2005). This perspective underlines that the spiritual well-being and needs of the individual remain intact, even as cognitive faculties decline.

The Orthodox Church’s care for the spiritual growth of individuals is also evident in the practice of administering communion to young children. This approach can be somewhat paralleled to the condition of dementia, where the state of an individual not yet fully conformed to Christ resembles that of childhood (Larchet 2000). This implies that the soul of the recipient comprehends the significance of the Eucharist, even if the conscious mind does not, reinforcing the belief that the grace imparted by the Sacrament of Communion for the healing of the soul and body is a crucial benefit that should not be withheld, especially in such cases.

Arguing for the normalcy and importance of administering the Sacrament of Communion to those suffering from dementia, it is essential to recognize that elders affected by this condition need the Eucharist just as much as they need food, water, and medicine. The administration of the Eucharist in these instances is not merely a ritualistic act but a profound manifestation of the Church’s understanding and compassion towards all its members, irrespective of their cognitive abilities. It underscores the belief that the Eucharist serves as a vital source of spiritual sustenance and healing, offering grace and comfort to those journeying from the mind to the heart amidst the trials of dementia.

In Orthodox Christian theology, the journey of aging is examined from a dual perspective, distinguishing between spiritual and physical elderhood. This nuanced perspective, deeply embedded in the wisdom of both the Old and New Testaments (Biblia 2018), recognizes the inevitable difficulties of physical deterioration while simultaneously highlighting the potential for significant spiritual growth and maturity. This dualistic approach nurtures a balanced understanding of aging, valuing both the physical and spiritual dimensions as integral to the holistic human experience. The bifurcation of aging into spiritual and physical realms encourages deeper contemplation of human existence. It suggests that while the body is subject to the ravages of time, the spirit can transcend these physical constraints, growing richer and deeper with the passage of the years. The physical decline is juxtaposed with an opportunity for spiritual ascension, where the true essence of a person—their faith, wisdom, and inner strength—can flourish even as the body weakens.

Spiritual old age, as delineated in the Wisdom of Solomon, is characterized by wisdom and a life unmarred by earthly desires (Wisdom 4:8–9), signifying that a venerable maturity comes not from years but from a life lived in pursuit of spiritual truth. In the New Testament, this theme continues. Paul’s letter to the Corinthians speaks of a renewal of the inner self day by day, despite the outer self-dying (2 Corinthians 4:16). This reflects the understanding that while physical strength wanes, spiritual strength can and should continually grow. Similarly, in his letter to Titus, Paul advises the older men to be temperate, dignified, and self-controlled (Titus 2:2), highlighting that spiritual maturity is an ongoing process, achievable and desirable in one’s later years. Contrastingly, the physical aspect of aging, as poignantly illustrated in Ecclesiastes, describes the decline and frailty of the human body (Ecclesiastes 12:3–5). The metaphor of the grasshopper burdened by age and the fear of heights and terrors on the way (Ecclesiastes 12:5) symbolize the inevitable physical limitations that come with aging. The Book of Psalms also contributes to this portrayal. Psalm 70:10 pleads, “Do not cast me off in the time of old age; forsake me not when my strength is spent”. This verse encapsulates the physical vulnerabilities and the reliance on divine support that characterize biological old age.

For the elderly in Orthodox Christianity, the principal theological focus should be on recognizing and embracing the spiritual essence of their later years. As their physical abilities wane, greater importance is placed on deepening their relationship with God, transcending physical constraints to seek inner peace and wisdom. This stage offers a profound opportunity for spiritual reflection, nurturing a more intimate bond with the divine, and contemplating life’s journey through the prism of faith. Trust in God’s guidance becomes essential in this phase as elders prepare for the transition from temporal existence to eternal life. This preparation, centered around faith, repentance, and seeking harmony with God and others, is pivotal, marking a significant step in their spiritual pilgrimage towards the anticipated encounter with the Righteous Judge at life’s end.

Death is a necessary and significant moment in life’s journey, marking the transition from earthly existence to eschatological fulfillment. Additionally, biological death, which was not specific to the perfectly created Adam, is perceived as a form of punishment and thus instills fear in the hearts of people. But for Christians, death has profound significance. Through death, Christ leads us into full communion with God, elevating our level of intimacy with Him and, consequently, granting us the fullness of life. Death must be seen as a gateway to a higher reality and a means through which humanity can attain a superior level of relationship with God and experience a complete and perfect life (Staniloae 1996).

Biological death is not inherently frightening. It becomes a source of fear and apprehension primarily when it takes individuals by surprise, finding them unprepared for its inevitability. This is where the role of liturgical life within the Orthodox Christian tradition comes into play. Liturgical practices and rituals hold a central place in the Orthodox faith, serving not only as acts of worship but also as a means of spiritual formation and preparation for life’s ultimate transition: death. Within this framework, the Orthodox Church views death not as a final endpoint but as a transformative process (Hatzinikolaou 2003). It is seen as an opportunity for individuals to shed the burdens of sin, repent, and be reborn in Christ. The continuous engagement in liturgical activities, such as Baptism, regular participation in the Divine Liturgy, fasting, prayer, and confession, is akin to a rehearsal for the moment of death. Through these liturgical practices, Orthodox believers constantly remind themselves of the need to die to sin, shed their spiritual impurities, and prepare to be resurrected in union with Christ.

Incorporating the “Disability Theology” perspective into the liturgical and pastoral framework of the Orthodox Church would enrich our understanding of inclusivity within the religious community, especially for those facing disabilities in their later years. “Disability Theology” not only challenges traditional perceptions of disability within Christian theology but also advocates for a church that fully embraces every member’s dignity and spiritual worth, regardless of physical or cognitive limitations (Creamer 2012). It suggests a path toward a more compassionate and inclusive church, reflecting on how the Church’s liturgical life can better support individuals with disabilities, including elders, thus fostering a community that mirrors the full spectrum of human experience (Cooreman-Guittin and Van Ommen 2022).

The entire Orthodox liturgical life serves as a spiritual training ground, equipping individuals with the tools and mindset necessary to confront death not with fear but with hope and anticipation (Denysenko 2017). It emphasizes the belief that death is not the end but a gateway to a deeper communion with God, where the soul is purified and made ready for eternal life. In Orthodox Christianity, the preparation of man in the face of death is a fundamental priority of the Church. This priority is a reflection of the Church’s deep commitment to the spiritual well-being and salvation of its members, emphasizing guidance through the final journey and understanding death as a significant moment of spiritual transition, rooted in the hope of resurrection. Central to this journey is the Holy Liturgy, perceived within the Orthodox tradition as a missionary journey in itself (Sonea 2018). The Liturgy and the Sacrament of Communion serve as transformative experiences for the faithful, turning each participant into a missionary (Bria 1978). Furthermore, the sacred mysteries compel Christians to engage in the Church’s mission (Sonea 2017), extending their liturgical experience into daily life as an active expression of their faith. In the Orthodox tradition, the emphasis on pastoral care is paramount, often taking precedence over the external mission of evangelism (Himcinschi 2015). This approach reflects the view that salvation is a communal journey, with the Church accompanying each individual through all stages of life.

The sanctifying work of Grace represents the main way to assist the faithful in their journey towards eternal life. Among all the mysteries and liturgical acts preserved in the Church, the Sacrament of Communion constitutes the culmination point. Through Communion, man enters into perfect communion with the Lord Jesus and, thereby, with the entire Holy Trinity (Staniloae 1996). This teaching is based on the very words of the Savior, who repeatedly says: “Whoever eats My flesh and drinks My blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day” (John 6:54), or “For he who eats My flesh and drinks My blood, abides in Me, and I in him” (John 6:56), or “who eats Me, shall live through Me” (John 6:57); or “Whoever eats this bread (which came down from heaven) will live forever” (John 6:58). But this frightening approach of man to God, of creatures to the Creator, requires thorough preparation. This includes the Sacrament of Confession, for the remission of sins (Filaret and Ciocioi 2007).

In the realm of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, liturgical practices and sacramental participation vary significantly across different national churches. Among these, the Romanian Orthodox Church emphasizes particularly the preparatory process of confession for its faithful before partaking in the Sacrament of Communion. This Church holds that, in certain circumstances, the priest or bishop administering confession has the authority to withhold the Eucharist from a believer. This practice underscores a profound theological understanding that receiving the Body and Blood of Christ requires a state of reconciliation and readiness that is disrupted by sin. Such preparation is a natural prerequisite for those who, through sin, have created a distance or contradiction between themselves and God (Stăniloae 1997). For individuals whose liturgical life includes infrequent confessions—perhaps only once or a few times a year—the Sacrament of Confession becomes an indispensable condition for receiving the Sacrament of Communion (Deciu et al. 2015; Filaret and Ciocioi 2007). This distinct emphasis on confession as an integral part of the communion process highlights the Romanian Orthodox Church’s unique approach within the broader Orthodox tradition.

Consequently, the social and communitarian aspects of the Eucharist in the Romanian Orthodox context differ markedly from those observed in other Christian communities, including other Eastern Orthodox traditions such as the Greek Orthodox Church. In this light, the Sacrament of Communion emerges not merely as a personal act of faith but as a communal expression deeply intertwined with the moral and spiritual preparation of the individual, reinforcing the communal integrity and spiritual unity of the church body.

In addition to purification through Confession, preparation also involves the completion of a prayer canon. In the Orthodox tradition, this canon is divided into three parts: on the day preceding Communion, the faithful recite a canon consisting of nine odes, authored (possibly) by Saint Simeon the New Theologian. On the day of Communion, before the Holy Liturgy, twelve prayers are read, authored by prominent Church Fathers who lived between the 4th and 10th centuries: Saint Basil the Great, Saint John Chrysostom, Saint John Damascene, Saint Simeon the New Theologian, and Saint Simeon Metaphrastes. After Communion, five thanksgiving prayers composed by Saint Basil the Great, Saint Cyril of Alexandria, and Saint Simeon Metaphrastes are recited (Daniel 2012). In the Orthodox Church, there’s a customary practice of incorporating the initial private prayers of certain saints into public worship. This tradition arises from the belief that the extent to which one comprehends the profound mystery of human proximity to God is contingent upon their spiritual maturity. Consequently, this elevates eminent saints as benchmarks for understanding the Mystery.

Besides the distinct theological matters concerning death and, by implication, individual judgment, alongside topics like the state of sin and life’s purpose, other topics previously addressed here also resonate in the religious experiences of the elderly. These include physical pain, frailty, and community belonging, among others.

Summarizing this complex approach to aging from the perspective of the four dimensions, the main specific challenges are found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main challenges of elderhood.

Throughout our study, we delve into the Sacrament of Communion as interpreted by the Holy Fathers, whose prayers form the Communion canon, to understand its response to various challenges. The article specifically focuses on the analysis of theological texts related to this Sacrament, including the odes and prayers that precede and follow its administration. Our objective is to examine whether the stated effects of the Sacrament of Communion directly address the unique challenges encountered by elderly individuals. This exploration is aimed more at understanding the Sacrament’s impact from a theological perspective than evaluating its alignment with the recommendations from diverse scientific disciplines. By doing so, we seek to shed light on the significance and potential benefits of these ancient practices and their relevance to the lives of the elderly within the faith community.

2. Results

2.1. Inter-Rater Cohen’s Kappa

In this study, Cohen’s kappa (K) was calculated to assess the level of agreement between two evaluators in identifying text fragments that articulate the effects of the Sacrament of Communion. This statistical measure was employed to determine the consistency of the evaluators’ judgments, providing a quantifiable metric to evaluate the reliability of their assessments. By applying Cohen’s kappa, we aimed to establish a robust understanding of how well the evaluators aligned in their interpretations, particularly in distinguishing relevant text segments that effectively convey the impact of this Sacrament. The inter-rater results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of the inter-rater evaluation.

The resulting K value of 0.807 reflects an almost perfect agreement between the evaluators. This high Kappa score indicates a remarkable level of consensus in their interpretations and judgments, with P0 (Observed Agreement) reaching an impressive value of 0.943. The Pe (Expected Agreement by chance) value, which represents the agreement expected by random chance alone, is calculated at 0.707. This comparison between P0 and Pe underscores the substantial extent to which the evaluators’ agreement surpasses what would be anticipated through random chance alone. The remarkable consensus achieved by the evaluators vividly illustrates that the texts under scrutiny are well-structured and unambiguous. This exceptional agreement highlights the accessibility of the textual content. It is evident that the examined texts are so clear and comprehensible that different evaluators arrived at congruent interpretations with ease. This clarity not only facilitates our research but also contributes to the overall transparency and validity of our findings.

2.2. Homogeneity and Diversity of Analyzed Documents

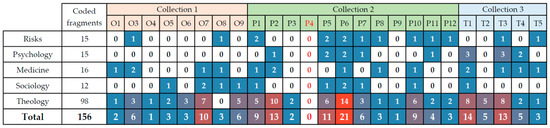

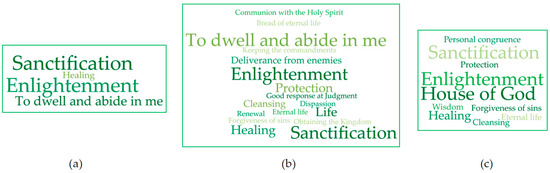

In the scholarly endeavor to dissect the nuances within our selected corpus, a comprehensive analysis was undertaken. This in-depth examination has unveiled a juxtaposition of homogeneity and diversity among the analyzed documents. As expected, a recurrent thematic element comes to light: barring a lone exception, each document in the corpus is intricately embroidered with references to the manifold effects of Communion, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Documents Comparison.

In addition to the originally applied lenses—Psychology, Medicine, Sociology, and Theology—our analytical journey revealed a new theme: the potential risks associated with partaking in Communion in an unprepared state, adding a layer of complexity to the thematic diversity.

Quantitatively, the documents exhibit a compelling progression in the frequency of coded segments, reflective of both homogeneity in thematic focus and diversity in thematic intensity. The initial collection, the ‘Odes’, sets a baseline with an average of four coded segments per document, indicating a moderate engagement with thematic content. This number shows a significant increase in the second collection, ‘Pre-Communion Prayers’, with an average of seven segments, suggesting a deeper thematic exploration. The top of this thematic density is observed in the third collection, ‘Thanksgiving Prayers’, averaging eight coded segments, indicative of the most profound engagement with the Communion theme across the collections.

The spectrum of homogeneity and diversity in our analysis is framed by two distinct outliers. The Fourth Prayer of St. Simeon the Metaphrast (P4) is devoid of any coded segments, thereby diverging from the common thematic thread. In stark contrast, the Sixth Prayer of St. Basil the Great (P6) exemplifies diversity with its dense aggregation of twenty-one coded segments, making it the most thematically rich document in terms of discussing the effects of Communion.

2.3. In-Depth Examination of the Densest Text

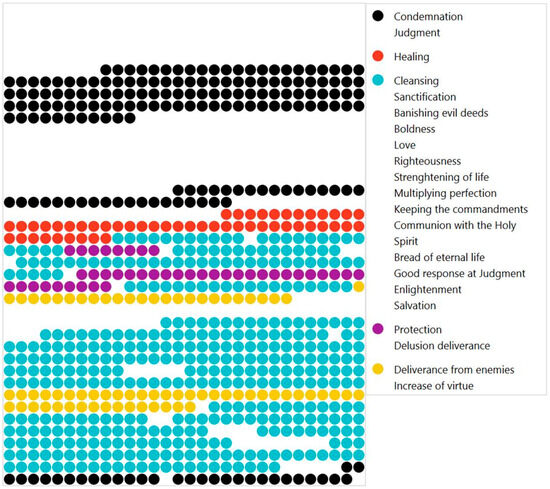

In the intricate tapestry of the Sixth Prayer of St. Basil the Great (P6), a significant portion of the text is devoted to elucidating the manifold effects of Communion. This prayer, a cornerstone in liturgical texts, presents a comprehensive exploration of Communion’s impact, spanning across all five distinct domains. These domains include risks (represented in black), psychological aspects (in purple), medical implications (in red), social dimensions (in yellow), and theological perspectives (in turquoise), each color-coded to facilitate a clearer understanding of their respective representations, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Portrait of the Sixth Prayer (St. Basil the Great).

The theological complexity encapsulated within this prayer is particularly noteworthy. It reflects the profound spiritual experience of its author, St. Basil the Great, whose elevated spiritual life significantly influenced his theological contributions. This depth of spiritual experience is not only evident in the prayer itself but is also affirmed by subsequent theological discourse. The rich theological aspects explored in the prayer stem from St. Basil’s profound spiritual insights, which have been consistently recognized and validated by later theological scholarship. His personal spiritual experience contributes to the enduring significance of prayer and its comprehensive coverage of the various effects of Communion.

2.4. The Thematic Evolution of St. Basil the Great, as Author, across Collections

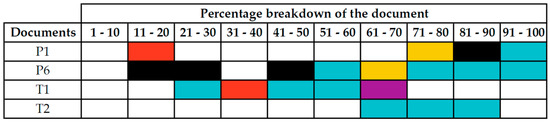

As shown in Figure 3, in the corpus of contributions of Saint Basil the Great, a remarkable consistency is observed across all four of his texts.

Figure 3.

Thematic Evolution.

This consistency is particularly evident in the thematic focus and theological depth he brings to each piece. Notably, the theme of the risks associated with unworthy participation in Communion—a significant aspect of Saint Basil’s texts—is exclusively addressed in the prayers preceding the act of Communion itself. This thematic placement underscores the importance of spiritual preparedness and the seriousness with which Communion should be approached.

Focusing on the post-Communion prayers, the First Thanksgiving Prayer (T1) engages predominantly with theological aspects, reflecting a deep immersion in doctrinal exploration. However, this prayer also integrates medical and psychological dimensions, albeit to a lesser extent. These elements are not treated as peripheral but are woven into the overarching theological narrative, demonstrating Saint Basil’s recognition of the interconnectedness of physical, mental, and spiritual well-being. The social aspects, while present, are addressed only marginally, indicating a prioritization of personal spiritual reflection over communal or societal implications.

In contrast, the Second Thanksgiving Prayer (T2) is exclusively dedicated to exploring the theological effects of Communion. This prayer focuses solely on the spiritual ramifications of the Eucharistic experience. The absence of other domains such as social, medical, or psychological underscores a deliberate emphasis on the transformative spiritual power of Communion, as understood and articulated by Saint Basil. This prayer serves as a clear illustration of his theological focus, offering a deep dive into the spiritual dynamics of Communion without the distraction of other thematic elements.

2.5. General Perspective on the Texts

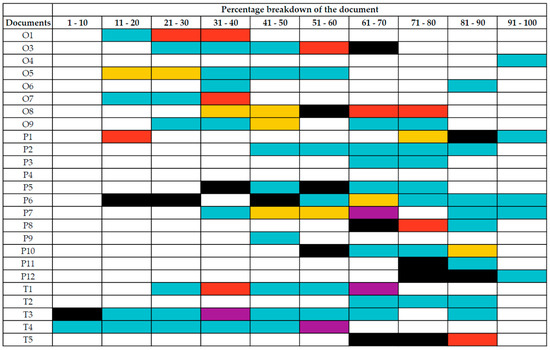

The study of these liturgical texts reveals that the effects of the Sacrament of Communion on the believer emerge as a principal theme, with the notable exception of the text labeled P4—Figure 4.

Figure 4.

General Thematic Perspective.

A predominant focus is observed on theological implications (in turquoise), overshadowing the medical, psychological, or social aspects. This emphasis on theology aligns with the inherent nature of the Sacrament of Communion as a deeply religious sacrament, thus steering the narrative towards a more spiritual exploration.

A pattern becomes evident when examining the distribution of segments coding the effects of the Sacrament of Communion throughout the liturgical process. As the faithful journey through the prayers of the preceding day, followed by the prayers before Communion, and culminating in the post-Communion prayers, there is a noticeable increase in the density of segments that articulate these effects. This trend suggests a crescendo in the intensity and complexity of the Sacrament’s impact as the liturgical process unfolds, mirroring the spiritual progression of the believer.

Moreover, the placement of these coded segments predominantly in the central portions of the prayers is noteworthy. This central positioning may be indicative of the core significance these effects hold within the overall structure of the prayers. It highlights the central role of the Sacrament of Communion in the spiritual life of the believer, as these crucial segments are embedded at the heart of the prayers, symbolically mirroring its position at the center of Christian worship and belief.

2.6. Evolution of the Message among the Collections

In analyzing the liturgical texts, it becomes evident that there is more to consider than just the increase in size and frequency of segments addressing the effects of the Sacrament of Communion. An important aspect to highlight is the thematic evolution within these segments. To understand this evolution more clearly, we applied the technique of ‘code cloud’ analysis, which allows for a visual representation of themes and their prevalence across different texts. When this technique is applied to the three collections of prayers (Odes, Prayers, and Thanksgiving), a potential thematic evolution becomes apparent. This evolution is not just in the number of references to the Sacrament of Communion’s effects but also in the nature of these references. The thematic progression observed in these collections suggests a deepening and expanding understanding of its impact over the course of the liturgical process.

Moreover, the approach to analyzing these effects is dichotomous, focusing on two main aspects: the potential benefits and the associated risks. This dichotomy provides a comprehensive view of these Sacrament’s effects, acknowledging both the positive spiritual and communal impacts as well as the risks associated with improper participation or understanding. The balance of these two aspects offers a nuanced perspective on the Sacrament of Communion, reflecting its complex role in the spiritual lives of believers and in the broader context of Christian worship.

2.6.1. Benefits

The analysis of the texts reveals a thematic and ideational constancy, marked by a dominant theological perspective. The central focus of these texts is on sanctity and enlightenment, key tenets in understanding the transformative power of the Eucharistic experience—Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Evolution of Benefits Presented in (a) the Odes, (b) the Prayers, and (c) the Thanksgiving.

A profound aspect of this thematic constancy is the emphasis on the concept of holiness. The texts frequently explore the sanctification of the believer through participation in the Sacrament of Communion, highlighting the journey towards becoming more aligned with divine will and purpose. This journey is not just seen as an aspiration but as an active process of transformation, where the faithful are continuously moving towards a state of greater holiness and spiritual enlightenment. There is a noticeable thematic migration in the texts, which evolves from the initial invocation to ‘dwell and abide in me’ to the realized concept of becoming a ‘House of God’. This transition signifies a deepening understanding and experience of the Sacrament of Communion. Initially, the emphasis is on the invitation for divine presence to reside within the believer, a plea for spiritual indwelling. As the texts progress, this plea transforms into a recognition of the believer’s transformation into a sanctuary for the divine—a ‘House of God’. This represents not only the physical and spiritual union achieved through the Sacrament of Communion but also reflects a shift from a state of seeking to a state of realization and embodiment of divine presence.

The consistent thematic focus and its evolution within these texts underscore the richness of the theological perspective in understanding the Sacrament of Communion. It highlights how it is perceived not just as a ritual act, but as a pivotal event in the spiritual life of the believer, leading to sanctity and the embodiment of divine presence.

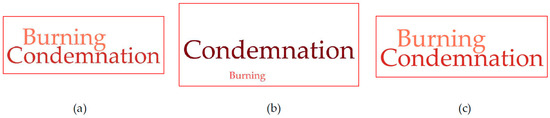

2.6.2. Risks

A notable consistency of the authors in their thematic and ideational perspectives is revealed. As seen in Figure 6, a particularly striking aspect of this thematic constancy is the emphasis placed on the risk of condemnation due to a lack of understanding or proper engagement with the Sacrament of Communion.

Figure 6.

Evolution of Risks Presented in (a) the Odes, (b) the Prayers, and (c) the Thanksgiving.

The authors emphasize the importance of approaching the Holy Eucharist with reverence, understanding, and a profound sense of its sanctity. They caution against superficial or unworthy engagement with It, pointing out that such an approach can lead to spiritual peril rather than blessing. This theme recurs across various authors, indicating a shared concern within the Christian tradition about proper understanding and participation in this sacrament. The authors contend that inadequate comprehension of the Holy Eucharist’s significance can lead to a genuine form of self-condemnation. The consistency in the thematic and ideational perspectives of these authors, particularly regarding the emphasis on the risks associated with improper engagement with the Sacrament of Communion, underscores the depth and seriousness with which this sacred mystery must be approached.

2.7. Specific Responses for Senior Challenges

Beyond the general elements related to the analyzed texts and the information/directions they provide, shifting perspective, and looking at the already highlighted issues in the four domains, the results reveal the following realities:

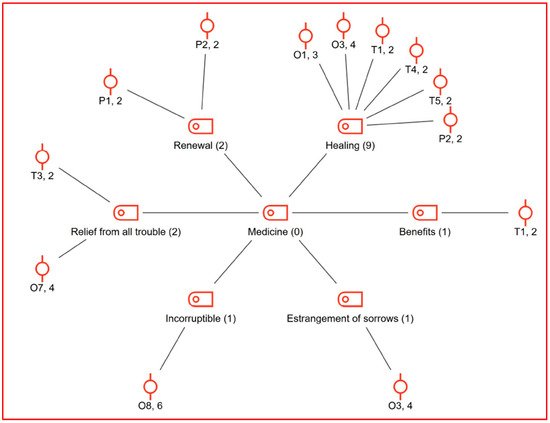

2.7.1. Medical Challenges

A multitude of medical effects have come to light, with a predominant focus on healing, relief from all troubles, and fostering renewal, as mentioned in Figure 7, under a code-subcode-text segment visualization.

Figure 7.

Subcodes and Text Segments of the Medicine Area.

The Sacrament of Communion is seen as a means to seek relief from all forms of suffering and difficulties, providing solace to those who partake in it: “estrangement from passions and sorrows” (Ode 3). It is also depicted as a source of renewal and regeneration. It is said to renew both the soul and the body, offering a sense of spiritual and physical rejuvenation. This renewal process extends to the entirety of one’s being: “through Thine own Blood Thou hast renewed our human nature” (Prayer 1), or “renew me entirely” (Prayer 2). The texts highlight Communion as a source of healing for both the soul and the body. It is perceived as a means to achieve overall well-being, addressing both spiritual and physical health concerns: “be for my purification and healing” (Prayer 6), “to receive Thy Most Pure Body and Thy Most Precious Blood for the healing of my soul and body” (Prayer 8), and “let Them be for the healing of soul and body” (Thanksgiving 1).

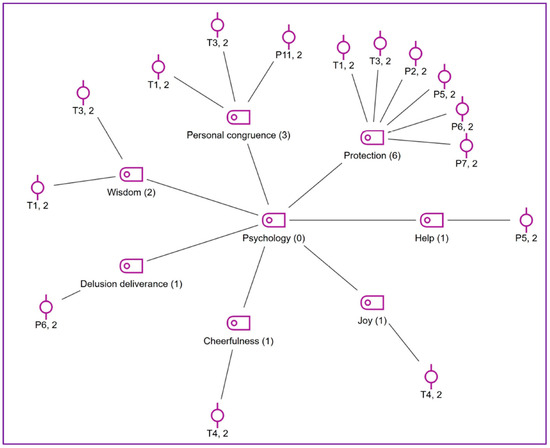

2.7.2. Psychological Issues

While Communion is primarily a spiritual practice, the texts highlight its psychological benefits in terms of alleviating anxiety, depression, and cognitive decline. Through its transformative influence on the human psyche, this Sacrament offers solace and inner strength, illuminating the path to emotional well-being and mental resilience.

The texts underscore Communion as a source of inner strength and support. This psychological bolstering can help individuals cope with anxiety by providing a sense of stability and resilience in the face of adversity: “But let them be […] a defense and a help and a repulsion of every evil attacker” (Prayer 5). The Sacrament of Communion is portrayed as a means of protection against diabolical forces. Partaking in the sacrament is believed to fortify the mind, creating a psychological shield against negative influences that can contribute to anxiety and fear “for the repulsion of every tempting thought and action of the devil which works spiritually in my fleshly members” (Prayer 6). The texts present the Sacrament of Communion as fostering harmony within the soul, a state that contributes to emotional well-being. The pursuit of wisdom, facilitated by this Sacrament, can enhance psychological resilience and emotional stability, counteracting depressive tendencies: “the peace of my spiritual powers […] the fulfilling of wisdom” (Thanksgiving 1). The Sacrament of Communion’s influence on cognitive function is also mentioned, referencing the illumination of the senses: “Illumine my five senses!” (Thanksgiving 3). This illumination suggests a potential cognitive enhancement, which can represent a real aid in counteracting cognitive decline. Partaking in Christ’s Supper is also associated with the acquisition of wisdom: “Give me understanding” (Thanksgiving 3). This wisdom may have a profound psychological impact, promoting emotional well-being and resilience against anxiety and depression. The abundance of directions can be observed in Figure 8, which provides a visual representation of the various aspects discussed in the text.

Figure 8.

Subcodes and Text Segments of the Psychology Area.

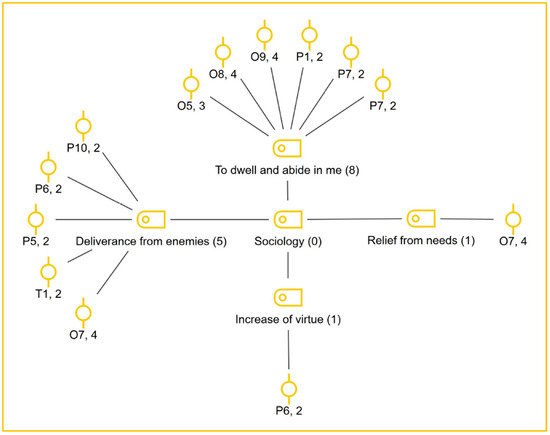

2.7.3. Social Concerns

According to the analyzed texts, the Sacrament of Communion plays a vital role in addressing social aspects of human existence. By fostering a sense of union, providing protection, and banishing adversarial forces, it actively combats marginalization and loneliness, contributing to a sense of inclusion and belonging within the faith community and God Himself.

The Sacrament of Communion serves as a means of defense against adversaries. Partaking in the sacrament is believed to offer protection, thereby diminishing the sense of marginalization or vulnerability to external threats: “may I be delivered from […] enemies” (Ode 7). The texts illuminate the concept of union through Sacrament of Communion, emphasizing that individuals unite not only with the divine but also with fellow believers. This union can alleviate feelings of isolation and loneliness, fostering a sense of belonging within a community of faith: “having You living in me with the Father and the Spirit” (Ode 9), or “partaking of Your Holy Things, I […] may have You dwell and abide in me, with the Father and Your Holy Spirit” (Prayer 1), and “When I partake of Your Divine and Deifying Grace, I am no longer alone—I am with You, my Christ, the Light of the Triple Sun Which enlightens the world! May I not remain alone without You” (Prayer 7). The texts explicitly mention the act of repelling all adversaries: “the repelling of every adversary” (Thanksgiving 1). This concept extends to the removal of any external factors that may lead to social marginalization or loneliness. The complete portrait of the social aspects is presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Subcodes and Text Segments of the Social Area.

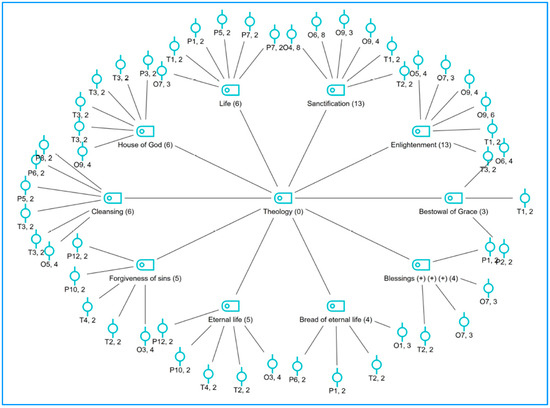

2.7.4. Theological Insights

The texts under study not only elucidate the theological effects of the Sacrament of Communion but also highlight its predominant resonance within the theological realm. As can be anticipated, the lion’s share of the Sacrament of Communion’s reverberations occurs at the theological level, attributable to its deep spiritual significance and theological ramifications. The sacrament, rich in spiritual and theological meaning, naturally catalyzes profound effects within this sphere. It is in the fertile soil of this theological dimension that the essence and ramifications of Communion are deeply explored and understood. This domain provides the context for some of the most insightful and profound interpretations of Communion, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of its role and significance in the faith community (Figure 10). The texts reveal profound theological insights into the effects of the Sacrament of Communion on the believer, emphasizing themes of sanctification, enlightenment, life, and transformation into a dwelling place for the Divine. The Sacrament of Communion is consistently portrayed not just as a ritual act but as a profound encounter with the sacred, carrying transformative effects.

Figure 10.

Subcodes and Text Segments of the Theological Area.

Central to these texts are the themes of sanctification and purification. Repeatedly, the Holy Eucharist is described as a means of cleansing the soul and body, burning away sins and passions: “may Thy Most Pure Body and Divine Blood be for the remission of my sins, the Communion of the Holy Spirit, […] and estrangement from passions” (Ode 3), or “May Thy Body and Most Pure Blood, […] be to me as fire and light! May they set flame to my sinful matter, burning the thorns of passions and fully enlightening me” (Ode 9). This purification is not merely external; it penetrates the heart and mind, leading to a holistic transformation of the believer: “for the most perfect removal and destruction of my evil thoughts and reasonings and intentions, fantasies by night” (Prayer 9) or “Consume the thorns of my transgressions! Cleanse my soul and sanctify my reasonings!” (Thanksgiving 3).

Enlightenment and spiritual illumination are other key themes. The Holy Eucharist is depicted as a source of divine light, dispelling the darkness of ignorance and sin and illuminating the believer’s path: “May the Burning Coal of Thy Body, O God and Word of God, be a Light in my darkness” (Ode 5), or “May Thy Body and Most Pure Blood, my Savior, be to me as fire and light!” (Ode 9), or “Thou shalt enter and enlighten my darkened reasoning.” (Prayer 9), “and enlighten my spiritual senses” (Prayer 11), and “O my Christ, and make me, Thy servant, a child of light!” (Thanksgiving 3). This spiritual enlightenment goes hand in hand with the idea of gaining wisdom and understanding, crucial for the believer’s journey towards God “let Them be for […] the illumining of the eyes of my heart,” (Thanksgiving 1).

The transformation of the believer into a ‘House of God’ is a significant theme. Through partaking in the Sacrament of Communion, the believer becomes a dwelling place for the Divine, a temple where the Holy Spirit resides: “May I become Thy dwelling through Communion of the Sacred Mysteries, having Thee living in me with the Father and the Spirit” (Ode 9) or “Show me to be a temple of Thy One Spirit” (Thanksgiving 3). This transformation underscores the intimate union between the believer and the Divine, facilitated by the Eucharistic experience: “Consume me not, O my Creator, but instead enter into my members, my reins, my heart!” (Thanksgiving 3).

Some Other Aspects

The aspect of life—both eternal and renewed spiritual life—is also emphasized. The Holy Eucharist is repeatedly referred to as the ‘Bread of Eternal Life’ and a means to eternal communion with God: “May Thy Holy Body and Precious Blood, O Lord, be my Bread of everlasting life” (Ode 1) or “provision for the journey of eternal life” (Prayer 1). Partaking in Christ’s Supper is not just a promise of life after death but a means of living a sanctified life here and now: “I may partake of Thine Undefiled and Most Holy Mysteries, which enliven” (Prayer 7).

In the realm of the texts, the Sacrament of Communion holds a significant role in preparing the faithful for the Final Judgment. This sacrament is not merely a ritual of remembrance but acts as a conduit of divine grace, equipping believers to stand confidently before the Throne of Judgment. As articulated in Prayer 1, it is seen as a means to ensure “an acceptable answer at Thy dread judgment seat”. This statement underscores the belief that participation in the Sacrament of Communion can positively influence the believer’s standing in the afterlife, specifically during the divine judgment. Further supporting this view, another fragment offers a poignant prayer, beseeching that through partaking in the Holy Mysteries, one may be deemed worthy to receive “a place at the right hand with the saved through Communion of Thy Holy Mysteries!” (Prayer 3). This imagery of being placed at the right hand is deeply symbolic in Christian theology, representing favor, righteousness, and salvation. The Holy Eucharist, therefore, is perceived as a vital element in attaining this coveted position. Other text reinforces this concept, again mentioning “a good and acceptable answer at Thy dread judgment” (Prayer 6). The repetition of this theme in multiple prayers indicates a strong theological consensus on Its role in the eschatological narrative. Through the Sacrament of Communion, the faithful are not only reminded of Christ’s sacrifice but are also imbued with the grace needed to face the ultimate divine scrutiny.

The complex aspects of the theological domain, as they emerge from the analysis of the texts, can be observed in Figure 10.

3. Discussion

3.1. Inter-Rater Reliability and Textual Clarity

The significant Cohen’s Kappa value of 0.807 indicates an exceptional agreement level between evaluators, surpassing chance (P0 = 0.943, Pe = 0.707). This suggests that the texts articulate the Sacrament of Communion’s effects with unusual clarity, aligning with the idea of a structured nature of liturgical texts and contradicting the expected subjectivity in religious text interpretation. The clarity observed implies less ambiguity in these theological texts than is typically assumed. Future studies might explore if this clarity is a unique characteristic of Communion-centered texts or a common feature in other religious writings.

3.2. Homogeneity and Diversity in Themes

The dual nature of the texts shows both thematic homogeneities, with consistent references to Communion’s effects, and diversity, marked by the evolution of themes, including the unforeseen risks of unworthy participation. This complexity reflects the multifaceted nature of religious texts, where an overarching theme can branch into diverse elements. This aligns with the inherent richness of religious texts, which often encompass a broad spectrum of themes. Future studies could examine the evolution of these themes across various religious traditions or within different Christian sacraments.

3.3. Thematic Depth in St. Basil’s Prayers

St. Basil’s prayers display deep theological consistency, particularly highlighting the risks of unworthy Communion participation and the importance of spiritual preparedness. This sheds light on the early Christian liturgical emphasis on moral and spiritual purity, complementing existing literature. Comparative studies of thematic focuses among various Church Fathers or across different Christian periods could offer a broader view of liturgical practice evolution.

3.4. General Thematic Evolution

The increase in thematic density and complexity suggests a purposeful design in liturgical texts, supporting the hypothesis that these texts are crafted to reflect the worshippers’ spiritual journey, beyond mere doctrinal conveyance. Comparative analysis of this thematic progression in various liturgical traditions or its influence on individual spiritual experiences could deepen understanding of liturgical text roles in religious rituals.

3.5. Medical Benefits of the Sacrament of Communion

The findings emphasize its role in spiritual and physical healing and rejuvenation, resonating with the traditional view of sacraments as divine grace channels influencing overall well-being. This extends the interpretation of healing in religious texts to physical health. Future research could investigate the physiological impacts of spiritual practices, potentially bridging faith and medical science.

3.6. Psychological Impacts

The Sacrament of Communion’s role in alleviating psychological distress, such as anxiety and depression, aligns with the hypothesis that spiritual practices benefit mental health. This adds to the literature on the positive psychological effects of religious observances, suggesting their crucial role in emotional and mental resilience. Future research could examine the psychological effects across various demographics or compare these effects with those of other spiritual practices.

3.7. Social Implications

The results highlight the role of Sacrament of Communion in addressing social challenges like marginalization and loneliness, enhancing the communal aspect of this sacrament. This aligns with sociological research on religion, emphasizing the significance of communal rituals in fostering social cohesion and belonging. Future studies could explore its role in community building across cultures or its impact on social dynamics within religious groups.

3.8. Theological Insights and Eschatological Implications

The role of the Sacrament of Communion in purification and sanctification aligns with Christian sacraments’ traditional view as divine grace channels. This not only symbolizes purification but also embodies a transformative process affecting the believer’s entire being. Comparative theological research could explore various Christian denominations’ sacramental theology, focusing on purification and its spiritual growth implications.

The Sacrament of Communion as a source of divine light and wisdom highlights sacraments as enlightenment conduits, playing a crucial role in the believer’s cognitive and spiritual awakening. This contributes to theological discussions on divine revelation and human understanding within sacramental participation. Future research might explore the connection between sacramental practices and cognitive–spiritual enlightenment, possibly uncovering the psychological and neurological bases of these experiences.

The transformation of believers into a ‘House of God’ through Communion reflects the intimate divine–human union, central to Christian mysticism and sacramental theology. Comparative studies with other traditions having similar divine indwelling concepts could broaden this theological understanding.

The Sacrament of Communion’s eschatological role in preparing believers for the Final Judgment, transcending ritual remembrance to active divine grace participation, enriches eschatological studies in Christian theology. It highlights sacramental practices’ impact on beliefs about the afterlife and divine judgment. Future research into eschatological themes’ historical development in Eucharistic theology could deepen our understanding of their influence on Christian life and afterlife beliefs.

4. Materials and Methods

The study is based on qualitative research, with a specific focus on the Romanian Orthodox Communion Canon prayers, comprising the nine odes (O1–O9), the twelve pre-Communion prayers (P1–P12), and the five post-Communion thanksgiving prayers (T1–T5). The preference was given to the Romanian version of these texts since it is the authors’ native language. Textual data was obtained from online sources, specifically the official website of the Orthodox Metropolis of Moldavia and Bucovina (Doxologia 2011a, 2011b), and compared with the printed version of the official Hieratikon/Liturgikon (Daniel 2012), published by the Publishing House of the Biblical and Orthodox Mission Institute of the Romanian Patriarchate. The English texts used for exemplifications in this article were collected from the official site of St. Symeon Orthodox Church, a parish of the Orthodox Church in America, Diocese of the South (St. Symeon Orthodox Church 2023a, 2023b, 2023c). In addition to the specified materials, it is important to clarify that the qualitative analysis undertaken in this study focuses primarily on the examination of prayers and their theological and pastoral content and not on the effects experienced by the faithful. This analysis is not underpinned by empirical research in the traditional sense. Instead, it delves into the intrinsic qualities and meanings within the prayers of the (Romanian) Orthodox Communion Canon, encompassing their liturgical, theological, and pastoral dimensions.

The research was carried out by a team of three researchers. Initially, two researchers independently extracted fragments related to the effects of the Sacrament of Communion. Both direct and indirect references were separately recorded. To assess the agreement between the two initial raters, Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated (Cohen 1960). The kappa statistic serves as a measure of inter-rater reliability, specifically indicating the extent to which raters assign uniform ratings to the same variables beyond what would be expected by chance. It assesses the accuracy of the collected data in portraying the variables under examination (Syed and Nelson 2015). A kappa value falling between 0.8 and 0.9 signifies a strong level of agreement, while values exceeding 0.9 indicate nearly perfect agreement (McHugh 2012). Any discrepancies between the initial two raters were resolved through a third-party resolution method, as suggested by Syed and Nelson (2015), with the decision of the third member of the research team.

The qualitative analysis software Maxqda (version 2022, by VERBI) was used for coding and analyzing the selected texts. We examined how the described effects of the Sacrament of Communion, as interpreted by the Holy Fathers through their prayers that constitute the Communion canon, address the specific challenges typically faced by the elderly. Given the diversity of authors, styles, and text structures, the unit of analysis was determined to be the word count. The results were generated using the same Maxqda (version 2022, by VERBI) software.

Beyond the relevance and response to the issue of aging and its specific challenges, the research also pursued other aspects of the studied texts: the identification of common themes and differences among the three collections (the nine Odes, the twelve pre-communion prayers, and the five post-communion prayers) and comparisons of writings by the same author across different collections.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study underscores the efficacy and normality of employing content analysis tools in examining religious texts, demonstrating that such methods can yield profound insights into the thematic structure and depth of liturgical content. This comprehensive understanding of the Sacrament of Communion’s multifaceted impact not only contributes significantly to theological discourse but also serves as a vital means of fulfilling the Church’s missionary mandate. By deeply engaging with current pastoral practices and elucidating their profound spiritual significance, this study paves the way for a more effective and holistic approach to ministry, one that fully embraces and articulates the rich tapestry of Christian liturgical tradition and its relevance in contemporary religious life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.C.T., S.A.C. and H.V.B.; methodology, T.C.T., S.A.C. and H.V.B.; validation, S.A.C.; formal analysis, H.V.B.; investigation, T.C.T. and H.V.B.; resources, S.A.C. and H.V.B.; data curation, H.V.B.; writing—original draft preparation, H.V.B.; writing—review and editing, T.C.T. and S.A.C.; visualization, H.V.B.; supervision, T.C.T. and S.A.C.; project administration, H.V.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our profound gratitude to Stavrophore Maria Asaftei, Mother Superior of the Monastery of St. Elisabeth in Cluj-Napoca, Romania. Her support, encouragement, and professional guidance have been essential in the course of our research. We are deeply appreciative of the insights and expertise she provided, which were instrumental in the successful completion of our work. Additionally, our thanks go to Archimandrite Simeon (Stefan) Pintea, Lecturer at Babeș-Bolyai University Cluj-Napoca, for his scientific support to our research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aburto, José Manuel, Francisco Villavicencio, Ugofilippo Basellini, Søren Kjærgaard, and James W. Vaupel. 2020. Dynamics of Life Expectancy and Life Span Equality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117: 5250–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltes, Paul B., and Margret M. Baltes. 1990. Psychological Perspectives on Successful Aging: The Model of Selective Optimization with Compensation. In Successful Aging, 1st ed. Edited by Paul B. Baltes and Margret M. Baltes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtson, Vern L., Roseann Giarrusso, Merril Silverstein, and Haitao Wang. 2000. Families and Intergenerational Relationships in Aging Societies. Hallym International Journal of Aging 2: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biblia. 2018. Biblia sau Sfânta Scriptură. București: Editura Institutului Biblic și de Misiune Ortodoxă. [Google Scholar]

- Birk, Jeffrey L., Ian M. Kronish, Nathalie Moise, Louise Falzon, Sunmoo Yoon, and Karina W. Davidson. 2019. Depression and Multimorbidity: Considering Temporal Characteristics of the Associations between Depression and Multiple Chronic Diseases. Health Psychology 38: 802–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, David E., David Canning, and Alyssa Lubet. 2015. Global Population Aging: Facts, Challenges, Solutions & Perspectives. Daedalus 144: 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bria, Ion. 1978. The Liturgy after the Liturgy. International Review of Mission 67: 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, Sefa. 2019. Socialization Helps the Treatment of Depression in Modern Life. Open Journal of Depression 8: 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Butler, Robert N. 1969. Age-Ism: Another Form of Bigotry. The Gerontologist 9: 243–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, Kristy J., David R. Black, Lyn M. Holley, and Daniel C. Coster. 2020. Stereotypes of Older Adults: Development and Evaluation of an Updated Stereotype Content and Strength Survey. Edited by Rachel Pruchno. The Gerontologist 60: e347–e356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, Brian D., Margaret Gatz, and Michael A. Smyer. 2022. Mental Health and Aging in the 2020s. American Psychologist 77: 538–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, Laura L. 2021. Socioemotional Selectivity Theory: The Role of Perceived Endings in Human Motivation. Edited by Suzanne Meeks. The Gerontologist 61: 1188–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1960. A Coefficient of Reliability for Nominal Scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement 20: 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooreman-Guittin, Talitha, and Armand Léon Van Ommen. 2022. Disability Theology: A Driving Force for Change? International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church 22: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creamer, Deborah Beth. 2012. Disability Theology. Religion Compass 6: 339–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimmins, Eileen M. 2015. Lifespan and Healthspan: Past, Present, and Promise. The Gerontologist 55: 901–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, Elaine, Lois R. Dean, David S. Newell, and Isabel McCaffrey. 1960. Disengagement—A Tentative Theory of Aging. Sociometry 23: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel. 2012. Liturghier cuprinzând Vecernia, Utrenia, dumnezeieştile Liturghii ale Sfinţilor: Ioan Gură de Aur, Vasile cel Mare, Grigorie Dialogul, (a Darurilor mai Înainte Sfinţite), Rânduiala Sfintei Împărtăşiri şi alte rugăciuni de trebuință. Bucureşti: Editura Institutului Biblic şi de Misiune Ortodoxă. [Google Scholar]

- De Beurs, E., A. T. F. Beekman, A. J. L. M. Van Balkom, D. J. H. Deeg, R. Van Dyck, and W. Van Tilburg. 1999. Consequences of Anxiety in Older Persons: Its Effect on Disability, Well-Being and Use of Health Services. Psychological Medicine 29: 583–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deciu, Nicuşor, Bogdan Scorţea, and Ştefan Voronca, eds. 2015. Învăţătură de credinţă creştină ortodoxă. București: Editura Institutului Biblic şi de Misiune Ortodoxă. [Google Scholar]

- Dementia and the Eucharist—Growing Old Grace—Fully. 2024. Available online: https://www.growingoldgracefully.org.uk/dementia/dementia-and-faith/dementia-and-the-eucharist/ (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Denysenko, Nicholas. 2017. Death and Dying in Orthodox Liturgy. Religions 8: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionigi, Rylee A. 2015. Stereotypes of Aging: Their Effects on the Health of Older Adults. Journal of Geriatrics 2015: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doty, Michelle M., Celli Horstman, Arnav Shah, Morenike Ayo-Vaughan, and Laurie C. Zephyrin. 2022. How Discrimination in Health Care Affects Older Americans, and What Health Systems and Providers Can Do. April 21. Available online: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2022/apr/how-discrimination-in-health-care-affects-older-americans (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- Doxologia. 2011a. Rugăciuni înainte de Împărtășirea cu Dumnezeieștile Taine|Doxologia. February 17. Available online: https://doxologia.ro/rugaciuni-inainte-de-impartasirea-cu-dumnezeiestile-taine (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Doxologia. 2011b. Rugăciunile de mulțumire după Dumnezeiasca Împărtășire|Doxologia. February 17. Available online: https://doxologia.ro/rugaciunile-de-multumire-dupa-dumnezeiasca-impartasire (accessed on 22 August 2023).