Abstract

This article explores how Christian faith communities respond to challenges in health care. These challenges are described, and a broader context is sketched, through an exploration of an ethics of care. Subsequently, two examples of Christian communities who respond intentionally to the need for care are presented and studied by using four sub-elements of care (attentiveness, responsibility, competence, and responsiveness) as a heuristic lens. Next, the relationship between care and salvation is discussed. Concludingly, the article argues that Christian communities of care are well equipped for sustainable caregiving because of their spiritual resources, and because they provide a life-context well-suited for caregiving.

1. Introduction

In many Western societies, care has become a major challenge. Among current crises threatening the general wellbeing of citizens, worries surrounding the availability, quality, and sustainability of health care provision loom in the background. Speaking theologically, the problems of a shortage of available care is one way that people experience (the threat of) evil in our time. In this article, we ask whether there is something to say about what ‘salvation’ might entail with regards to this experienced evil. We do so in a practical-theological way. That is, we explore practices in which care is embodied in a hopeful way, practices that answer to the needs of a society that fears a shortage of care. In these practices, we explore what they teach us about the nature of salvation.

To concretize the problems surrounding health care, we take our own Dutch context as an example. According to a recent report by the Dutch Social and Economic Council (SEC), people generally have a high esteem of the current state of health care, but they are highly worried about problems arising in the very near future (SER 2020a, 2020b). Currently, one out of every seven people in the Dutch workforce work within the broad field of care. However, an increasing number of vacancies are not filled. Because of an aging population, expectations are that these shortages in care workers will only grow. At the same time, the shortages are the highest amongst the youngest group of workers. Many students already drop out during their internships, stating that, because of the shortages, the work they are asked to do is beyond their capacities as interns. Many others choose career paths outside of the field of care within their first two years of working there. Because of these problems, employers in the field of health care often contract self-employed workers. Self-employed workers often charge higher fees and have much more freedom in planning their work, leaving the less desirable slots in time schedules understaffed. They do not build long term relationships with those they care for. Looking at it from a financial perspective further underscores the imminent problems. Between 1998 and 2018, the cost of healthcare per capita doubled. The SEC report projects a further increase in costs for the coming years. The conclusion of these developments can only be that care in its current form is not sustainable.

What stands out from the SEC report, is that the problems are identified and described but not traced to their roots. What are the deep-seated reasons for the rising costs? Why is it so difficult to find people who are willing to work in the field of care? Why do many workers lose motivation, become frustrated, or suffer from burnouts?

The developments described here are not new, neither are they limited to The Netherlands. In 1995, John McKnight (1995), professor emeritus of education and social policy at Northwestern University coined the term ‘the careless society’. McKnight argues that because of the professionalization of the field of care, time-tested sources of care within informal communities have deteriorated. Nowadays, we seek care primarily from doctors or other professionals. According to McKnight, this ‘counterfeit for community’, affects our society’s capacity for care in negative ways. Joan Tronto, an American professor of political science, earlier wrote that this context of professionalization of care leads to a ‘privileged irresponsibility’(Tronto 2015, p. 29). Care has become a commodity that those who have the financial means can afford to pay for.

In this article, we explore in which ways faith communities respond to the developments outlined above. As research in the European context shows, many Christian faith communities are already impacted by these developments. Whereas the prominence of Christian faith communities in terms of membership and influence is decreasing, the appeal by wider society for these communities to contribute to problems in the welfare state is increasing (Pettersson 2011). This is one way Christian faith communities fit within the problems around ‘care’ in Western societies: they might be sources of additional informal care, as they are close-knit communities and their members are statistically more active in volunteer work than the average population (de Hart and van Houwelingen 2018, pp. 65–67). But might these communities also have a role in challenging a ‘careless society’? Might it be possible that they could transform their members, and those around their communities, from being ‘privilegedly irresponsible’, to being ‘their brother’s keeper’?

This is the question we address in this article: how can Christian faith communities faithfully respond to the needs of a society that faces fundamental challenges surrounding care?

We will further address this question by sketching a historical ‘turn to care’ in the movement of the ‘ethics of care’ in Section 2. This broad movement, started by the above mentioned Tronto and others, seeks to build an ethics of care in which care is not a commodity but rather a fundamental aspect of being human. It is understood as, “a species of activity that includes everything we do to maintain, contain, and repair our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible. That world includes our bodies, ourselves, and our environment, all of which we seek to interweave in a complex, life-sustaining web.” (Tronto 1993, p. 103). This definition of care seems to be very close to Christians’ understandings of what Christian faith communities are called to do. Subsequently, in Section 3, we look into two Christian webs of practices in which care takes center stage. We seek to find out in which ways care is understood and embodied within these webs of practices. A next step is to reflect on this from a theological and ecclesiological viewpoint (Section 4). What is really at stake in these practices and how does this relate to broader theological reflections on the calling of the Church in the world? Finally, we sketch out the implications of our findings for practices of care in Section 5.

2. A Turn to Care

During the 1980s, the psychologist Carol Gilligan started to criticize the mainstream approaches to morality of her time. The initial trigger for her was Kohlberg’s theory of stages of moral development. We cannot go into the details of this theory and other theories of her time, but Gilligan found that in Kohlberg’s theory, and others, “the individual is prioritized over relations, rights are prioritized over responsibilities, and justice is upheld as the supreme standard for morality.”(Mannering 2020, p. 2). Gilligan asserted that this led to a one-sided moral ideal that was in line with modernist, neo-Kantian thinking. Based on research and her experience as a nurse, she stated that in many cases women adopted a care perspective rather than a justice perspective (Mannering 2020, p. 3). They valued relationships higher than the individual’s interest; they thought in terms of responsibility rather than rights. According to Kohlberg, this would place women on a lower level of moral development. But why would that be so? Why would justice be the supreme standard for morality and why could care not be equally such a standard?

Gilligan then became one of the feminist thinkers who started to develop an approach to morality that became known as ‘Ethics of Care’ or ‘Care Ethics’ (we will use the terms interchangeably). Debates are ongoing as to the demarcations of this approach and whether it should be considered an academic discipline of its own (Leget et al. 2019; Klaver et al. 2014). What is clear however, is that within this broad approach, care is not seen as the field of application of ethical reflection, but rather as “the perspective from which ethical reflection departs (such as virtue ethics, theological ethics or feminist ethics).” (Leget et al. 2019, p. 19). Care is seen as a fundamental aspect of humanity, or a (or the) supreme standard for morality. Care is intrinsically moral in this understanding.

The ethics of care then, are not only relevant to health care professionals. They are in fact an alternative approach to morality for every person. Important aspects of this approach include, “a relational anthropology, valuing of emotion, skepticism towards abstraction and universalism, and the recontextualization of the divide between private and public life.” (Mannering 2020, p. 3).

Within the ethics of care, care is hence not primarily seen as a commodity, something that can be purchased when needed and is practiced only by professional caregivers in a commercial setting. We already quoted the influential definition of care, given by Joan Tronto, namely, care is “a species of activity that includes everything we do to maintain, contain, and repair our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible. That world includes our bodies, ourselves, and our environment”.

This ‘species of activity’ is part of every human life and, if care is understood as a standard for morality, this definition functions as a normative framework to reflect on moral development. Such reflection is facilitated further by four sub-elements of care that Tronto (1993) identifies: (1) attentiveness (seeing the need), (2) responsibility (responding to the need), (3) competence (knowing how to respond), and (4) responsiveness (perceiving others as subjects, not merely an object of care). One could perceive these sub-elements as the virtues that make someone a caring, moral person.

Understood this way, the ethics of care seems to be closely related to the classical understanding of morality as virtue ethics, with ‘care’ as a classical virtue to be aspired to by individuals, just like courage, for example. However, some proponents of the ethics of care have argued that such an understanding limits the ethics of care to the individual sphere and overlooks the important social-political implications of a care approach to morality (Leget et al. 2019). Be that as it may, the relationship between care ethics and virtue ethics is clear in the respect that it is not about rules to be enforced or rights to be adhered to, but primarily about a process of growth in terms of becoming a more ‘caring’ person, organization, or society. When Tronto speaks of care as a ‘species of activity’, we must therefore understand this activity not simply as ‘things we do’, but rather as ‘practices’. Practices, according to Alasdair McIntyre’s classical definition (MacIntyre 1984, p. 187) are

“any coherent and complex form of socially established cooperative human activity through which goods internal to that form of activity are realized in the course of trying to achieve those standards of excellence which are appropriate to, and partially definitive of, that form of activity, with the result that human powers to achieve excellence, and human conceptions of the ends and goods involved, are systematically extended.”

From what we have seen from the ethics of care so far, it is not difficult to understand care as such a ‘practice’, or maybe even a web of caring practices. Care is socially established and cooperative, it is part and parcel of any society worthy of that name. Care strives to realize certain goods, it maintains, contains, and repairs our world. It operates to certain written and unwritten standards of excellence. But, and this is definitive of practices, it also systematically extends human conceptions of what care is, and what it should result in. In other words, it is by caring that one learns to care. We can therefore understand “caring as a practice of contributing to a life-sustaining web” (Tronto 1993, p. 103; Leget et al. 2019, p. 20).

It is important to note that practices are not, and can never be, merely individual, for they are socially established. Practices are practiced communally. Understanding care as a fundamental practice of society therefore also has political implications. Society is comprised of many intertwined ‘webs of practices’. Some are more caring than others. The stock exchange differs from the maternity ward in this respect. What care ethicists have shown, is that the strength of communities that practice care is deteriorating.

The ethics of care, broadly understood, contributes to our reflection on the challenges of Western societies with regards to care. They reveal that it is necessary to dig deeper than the numbers. Can we identify practices, and communities of practice, where Tronto’s sub-elements of care are practiced for example? If Tronto is right in her qualification of our time as, a time of ‘privileged irresponsibility’, if we have indeed drifted towards a ‘careless society’ (McKnight), then the grim reality of unfilled vacancies in health care and tight budgets becomes even more grim. Might we be getting at one of the underlying reasons so many vacancies are not filled? Looking at Tronto’s sub-elements, it stands out that it is difficult to ‘teach’ three out of four of these sub-elements. Competence can easily be included in a curriculum for nurses, for example, but attentiveness, responsibility, and responsiveness cannot be learned by reading textbooks. They must be acquired by taking part in practices of care.

3. Care in Two Christian Webs of Practices

In this section, we will look at Christian webs of practices from a practical-theological perspective. Our intention is to identify in which ways ‘care’ is embodied within these webs of practices. We understand practical theology in line with John Swinton and Harriet Mowat’s (Swinton and Mowatt 2006, p. 6) definition, as “critical, theological reflection on the practices of the church as they interact with the practices of the world, with a view to ensuring and enabling faithful participation in God’s redemptive practices in, to and for and for the world.” Hence, what is at stake in Christian communities is not primarily the conservation of a certain set of beliefs. Rather, we understand the calling of Christian communities as being to practice these beliefs. When this happens faithfully, according to the definition given above, it is somehow redemptive for our world. So Christian communities are called to foster practices of salvation. When we think back to Tronto’s understanding of care as maintaining, containing, and repairing our ‘world’, there is an obvious link.

To further explore this link between the objectives of both the ethics of care and Christian faith communities, we will look at two such communities, or webs of practices (Hütter 2001, p. 35) (some are local communities, others are better understood as global networks), and use Tronto’s sub-elements of care as a heuristic lens. These sub-elements will show us where ‘care’ and ‘participation in God’s redemptive practices’ meet in these webs of practices. In the next section, we will reflect on what this entails for our thinking about the imminent challenges of care in Western societies and the role that Christian faith communities can play in these challenges.

We have chosen two webs of practices that vary in intentionality when it comes to care. Firstly, we will look at the international network of L’Arche communities. These communities were founded specifically to foster caring relationships between people with and without disabilities. Secondly, we will turn our attention to Hart van Vathorst, an initiative in the Dutch city of Amersfoort, where an ‘average’ congregation came to share its building with a number of service and care providers for people with disabilities.

3.1. L’Arche

L’Arche is an international network of locally embedded communities where people with and without disabilities live together. The communities share a few key convictions. They believe in the equality of people with and without disabilities; they believe in the positive contribution people with disabilities can make to society; they believe spending time together with people with and without disabilities is a transformative experience; they believe in the importance of spirituality, departing from the Christian tradition but also broader than that; and they believe that the individual communities may and even must come in many shapes and must adapt to a changing world (L’Arche n.d.).

3.1.1. Attentiveness

When it comes to the founding of L’Arche, attentiveness plays an important role. Theologian Jason Greig (2018, pp. 63–64) writes about a decisive encounter that L’Arche founder Jean Vanier1 had when he went to visit an institution for people with intellectual disabilities, called Val Fleuri.

The cries of anguish and pain he encountered at the Val Fleuri horrified and fascinated Vanier. An atmosphere of sadness pervaded the institution, giving it an aura of rejection and despair. […] Yet Vanier looked deeper, and got a glimpse […] that behind the anguish were people searching for relationship and an affirmation of their being. In this first encounter, Vanier discerned the men asking penetrating questions: Do you love me? Will you be my friend? Will you come back tomorrow? These questions struck Vanier to the heart, and left an indelible imprint on him. His subsequent visits to other institutions only confirmed these intuitions further, and compelled him to discern a response. The conditions of these asylums, which left the men labelled disabled degraded and dehumanized, filled Vanier with an immediate sense of injustice. Yet not only was the Val and other asylums places of horror and injustice, but also contained a mysterious presence of God calling Vanier to an experience of encounter. […] The way for Vanier now became clear: God was calling him to discipleship by sharing his life with people labelled intellectually disabled. Vanier chose to embody his sense of vocation by buying a small house in Trosly-Breuil, France and welcomed three men from the Val Fleuri […] to live with him.

The house in Trosly-Breuil would become the first L’Arche community of many more worldwide. We italicized some phrases in Greig’s account that show the importance of attentiveness. Phrases like encountering, looking deeper, being struck to the heart, looking deeper, feeling a sense of vocation or calling—they show that attentiveness is a key element of the L’Arche communities.

This attentiveness is complex and multilayered. In one sense, it is an attentiveness towards the perceived needs of others. But it is also an attentiveness towards the structures of injustice. Moreover, it is an attentiveness towards hope, and somehow the presence of God in the midst of all of this.

Vanier (2007, p. 188) himself writes about the importance of attentiveness in Community and Growth. Those living in L’Arche communities must be “attentive to the many non-verbal communications, and this adds greatly to their ability to welcome the whole person. They become increasingly people of welcome and compassion. The slower rhythm and even the presence of the people with severe disabilities makes them slow down, switch off their efficiency motor, rest and recognise the presence of God”.

3.1.2. Responsibility

From this complex understanding of attentiveness, and specifically from its connection to the spiritual dimension of God’s calling, it is a small step towards Tronto’s sub-element of responsibility. Responding to this calling has an existential, even religious undertone to it. L’Arche’s practices reveal a relational anthropology in which responding to other people is fundamental.

The in-breaking of Christ’s claim on humanity and the work of the Spirit of God displaces the false self and makes possible a community comprising open relationships that are not possessive, relationships that give life to others rather than ones turned in upon themselves, which undermines others in their search for wholeness. Consequently, Vanier calls the conditions and spirit that influenced Sartre to dramatize Garcin’s famous utterance: “Hell is– other people” into question and offers a vision of community and growth in which God’s ways with mankind in the story of human existence offer new ways of being and belonging to others which makes community possible. At a deeper level, dependency not autonomy; for Vanier, is what it means to be and become fully human.(Wall 2016, p. 38)

To be human is to be responsible for others. Being dependent on one another is not considered a state of weakness to be overcome, but a fundamental expression of humanity.

This responsibility is understood in an immediate and relational sense, according to Jason Greig. L’Arche communities do not primarily understand responsibility in a political way. In this sense, the term responsibility might be less fitting for L’Arche’s practices than, for example, fidelity (Greig 2018, pp. 70, 204, 209, 244).

3.1.3. Competence

As the communities of L’Arche have evolved over time, they have adapted to the health care systems of the various countries where they are found. This includes complying with professional standards. However, in L’Arche competence is also considered something that continues to grow. It extends beyond ‘technical competence’ in the sense of providing specific health care services. Theologian Keith Dow (2019, p. 213) points to a distinction that Vanier made between ‘compassion competence’ and ‘compassion presence’ in this respect. In the words of long term L’Arche resident Odile Ceyrac (1981, p. 23), her competence grows as a result of hearing her fellow residents‘ ‘cry’, perceiving their needs but also the possibilities for meaningful relationships. In other words: attentiveness and responsibility result in growth in competence.

Jean Vanier (1995, p. 115) himself writes that, “L’Arche is a sign that faith and competence can embrace and work together for the human and spiritual growth and development of each person.” So a unique aspect of the L’Arche communities is the deep connection between competency in a technical sense of the word and the spiritual competency to begin to see others in new ways, responding to even deeper needs. Pamela Cushing (2010) calls this dynamic within L’Arche communities, ‘re-imagining disability’. This re-imagining is important because if relationships work on the basis of false assumptions about other people, they can become harmful, even if care is provided in a technically competent way.

3.1.4. Responsiveness

As seen in our reflection on the first three sub-elements above, the aspects of mutuality and reciprocity are seen as fundamental for the life of the L’Arche communities. However, it is relevant to note here that this does not mean that this responsiveness is actually practiced. We cannot ignore the fact that Jean Vanier himself, despite his belief in reciprocity, used his position, and even aspects from his belief system, to sexually abuse multiple women. Although these women did not have disabilities, there were still power structures in place that clearly enabled this abuse to happen. The question must be asked whether there are elements in L’Arche’s core and fabric that work against the sub-element of responsiveness. It must be noted as well that L’Arche itself is heavily invested in exploring this question (L’Arche 2020).

Lofty words like trust, encounter, mystery, dependency, and transformation, to name a few examples, are often used in describing the L’Arche communities. Such words refer to something powerful, something that happens in many L’Arche communities, and something that has benefited countless individuals and communities. However, such words can also make the interpersonal dynamics involved opaque, specifically when vulnerable people are involved.

Benjamin Wall (2016, pp. 114–15), in his practical theology of the L’Arche Communities, writes about ‘listening’ as a fundamental practice in L’Arche.

As we have seen, listening underlies, informs, and gives definite shape to community and care as a way of life, making genuine welcome within L’Arche possible. Correspondingly, listening gives shape to welcome as a way of life that entails living out one’s fidelity to the commonly held vision that the other lays claim to our being; […] faithful listening to others makes welcome possible…

If listening is practiced faithfully, it will strengthen the responsiveness of a community.

3.2. Hart van Vathorst

Hart van Vathorst is a cooperation between a church, two health care service providers, an inclusive day care center for children, and a few other partners. It is built around some of the same inclusive values as L’Arche. In fact, reflection on the L’Arche communities was part of the development of this project. It also departs from a Christian theological framework. However, a big difference is that in this case, the community being formed is ‘lighter’: the church members do not live in the same building as the residents of Hart van Vathorst. Care and assisted living are provided in a more or less conventional, professional way. Yet, the vision is to ‘share life’. Over the course of the first three years of this project, Koos Tamminga studied Hart van Vathorst, resulting in a PhD dissertation entitled Receiving the Gifts of Every Member (Tamminga 2020). We will use this resource to reflect on how Tronto’s sub-elements may or may not be embodied in Hart van Vathorst. Page numbers in this section refer to this book.

3.2.1. Attentiveness

What stood out from the study conducted in Hart van Vathorst, is that all church members who were interviewed reported to have been affected in their perspective towards people with disabilities in some way. For some members, this was a very radical change of perspective and attitude. For others, it was more subtle.

This stands out, because most church members, unlike in L’Arche communities, only have superficial interactions with the residents of Hart van Vathorst. However, these interactions, combined with intentional leadership that provides members with the narrative to discover deeper meanings in these interactions, does start a process. This process was described as follows:

From interaction in which people feel known and seen; to awareness in which issues become concrete and urgent; to understanding in which people also start to learn about the reasons for issues that others face and to look for possible solutions; to an atmosphere of acceptance in which there is room to be oneself and also to wrestle with one’s own limitations that are hard to accept. From the data, it appears that this process can be framed as a process of healing, or as a process of learning for all who are involved.(p. 198)

Much like in L’Arche, the element of attentiveness is laden with theological meaning. Over the course of this process of learning, a ‘double change of perspective’ takes place:

…seeing the world as God’s world, and seeing each other as valuable human beings from whom one can learn, regardless of (dis)abilities. These two renewed ways of seeing can then strengthen each other: By seeing the other as part of God’s world, one values the other person more highly and is willing to learn. By learning from the other’s spiritual life, one gains a deeper understanding of the world as God’s world.(p. 117)

One can say that attentiveness is necessary to start a project like Hart van Vathorst, but it is also grown, in a wider and deeper sense, over the course of the project. This is precisely why it is helpful to look at communities as webs of practices; it is by practicing attentiveness that attentiveness grows and is understood more deeply.

3.2.2. Responsibility

Relative to communities like L’Arche, Hart van Vathorst does not have the same level of motivation on the part of the church members. They have often not chosen to take part in the project, but just happened to be members of this congregation. They do not choose to live together in a community, but just come to church on Sunday. Although we have shown that this still impacts their attentiveness, we can also see in the study that a large number of the members do not immediately respond to the needs around them. Over the course of the first few years, those in leadership were sometimes disappointed by low attendances during activities they organized, or by how few church members had interactions with the residents on a more personal level.

A volunteer coordinator was introduced, to help to get people involved more deeply. A short story of Sam, one of the church members who experienced the work of this coordinator, may serve to show how meaningful this coordination proved to be:

At the outset, Sam was not exactly enthusiastic about the plans for Hart van Vathorst, and certainly had no plans to get involved with the residents. However, at some point he came into contact with one of them, having been asked multiple times by one of the coordinators to make music with a resident. In a moment of weakness he said yes: “I felt like I got suckered into it. I was too self-involved. But well… So I did it.” The interaction started off as a duty, but it did not end that way: “We became friends. And well, man… You come over for dinner sometime, that’s how you start to bond and create a friendship.”(p. 192)

This little story shows how in communities like Hart van Vathorst, people may need to be stimulated to take up their responsibility more than in high commitment settings like L’Arche.

3.2.3. Competence

The actual health care services in Hart van Vathorst are provided by the professional staff of the service providers. Nonetheless, church members like Jolien report that they do feel the need to acquire certain skills and competencies:

It is quite difficult, because you really have to learn how to deal with people with disabilities. You should actually treat them in a very normal way, treat them as equals, but you also need to interact with them at their own level… And sometimes it is difficult to understand them, and that’s something you have to learn. For some people that is very difficult to learn. So it makes me think, like, it’s not like you can just offer a crash course or something like that.(pp. 188–89)

Jolien is a young woman who, partly because of her experiences with people with disabilities at church, decided to take up a career as a care professional. Hence some of her reflections here about what good care for this group must look like. Nonetheless, it is clear that many church members have had to acquire skills for communicating, have learned about how to handle certain behaviors that they might have formerly been uncomfortable with, and have seen up close what professional care looks like.

However, just as in L’Arche, there is a double sense to competence in Hart van Vathorst. It is not only about technical skills, but also, and more so, about a deeper sense of learning and re-imagining.

Respondents mentioned that they learned a lot from interaction between people ‘with and without disabilities’, for example regarding trust, rest, genuineness, openness and space for otherness, and equality. Areas of learning also included aspects that relate directly to faith, such as unity, peace, discovering Christ and following him (discipleship), receptivity, cutting to the core of things and getting below the surface of outward appearance, and acknowledging one’s own limitations.(p. 197)

3.2.4. Responsiveness

In Hart van Vathorst’s vision, reciprocity is a fundamental value, undergirded by the equality of all people as being created in the image of God. However, it is also true that in practice, precisely here, some resistance is encountered. Church members sometimes perceive attention for the project and the residents as in conflict with other things they value in church. There are areas of church life, such as youth work, where there is hardly any interaction. Besides practical concerns, this lack of interaction, or irresponsiveness, is also explained by attitudes towards people with disabilities such as inexperience, fear, shame, and embarrassment, or even an outright lack of respect by respondents (pp. 216–27).

Responsiveness proves to be the most challenging of Tronto’s four sub-elements. Really taking the other seriously as a person, listening to their concerns, seeking their consent, is and remains a challenge.

4. Ecclesiological and Theological Reflection

So far, we have seen that care cannot be treated solely from a neo-liberal, economic perspective. It is not a commodity. Practically and conceptually, care is relational, and thus it consists of different practices and attitudes that reflect the habits of caregivers and the community that ignites from these practices. Care needs the fostering of values and attitudes like attentiveness, responsibility, and competence—not ideally or theoretically but through practicing care. Examples of communities that embody such practices have been given, not to imply that only Christian-inspired communities do so, but to highlight that attitudes, informed by practice, matter.

Attitudes, as we use this concept here, are the fruit of concrete, local, and therefore contextual, communal practice, in the Bourdieuean sense of the word (J. K. A. Smith 2013; Scharen 2015; Bass et al. 2016). This primacy of practice over worldview does not exclude theoretical reflection. On the contrary, communities of lived practice, as such, also demand for reflection as part and parcel of their actions, as those practices are more than just mundane routines. Such reflection can be labeled “constructive, theoretical interpretations of practice informed by assumptions that do justice to the irreducible logic of practice,” as the influential Christian philosopher J. K. A. Smith (2013) states. Habits acquired by practice create a kind of sensibility that ‘makes sense’ of the world in a way that still prioritizes practices. It is no abstract belief but ‘practical belief’, as it expresses a habituated (or ritualized) way of being in the world. Reflection on such practices or rituals, and the way they make sense of this world, are present in the narratives of communities—as well as the other way around: the narratives shape the liturgies that are performed (J. K. A. Smith 2013, p. 109).

4.1. Different Aims set by Communities of Care

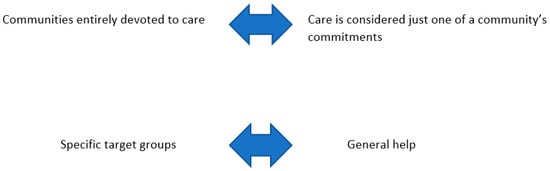

In light of these presuppositions, Christian communities of care are communities that—definitely flawed, and different from one congregation to another—practice care, both as a habit that has been acquired over time, and as public expressions of their faith. It is important to note the spectrum of kinds of care, differences in intensity in terms of time, means and people involved, the specific focus care might have locally, or the degree in which the community as a whole is characterized by being a community of care. To discern these differences, a continuum (Figure 1 and Figure 2) can be helpful as a heuristic tool.

Figure 1.

Care in communities.

Figure 2.

Different kinds of communities of care.

Christian communities have given countless examples of these four kinds of communities of care, both in the past and in the present. The two examples listed above are just examples of a current re-invention or rediscovery of the intense value that, especially Christian, communities of care have in the current context of a post-Christian secular West. They function as an inspiration to figure out what their specific calling in their context might be, either individually or as a community. HvV has had an impact far beyond the community: the mayor of the city, the Dutch minister for health, and several delegations from abroad have visited HvV to learn from it (Tamminga 2020, pp. 100–8).

4.2. Reflexivity and Christian Communities of Care

The point of this article, however, is foremost on a conceptual level. When we reflect on the current situation and prospects of care in Dutch society, as outlined above, and on the webs of practice as embodied in Christian communities of faith, what then is at stake theologically and more specifically ecclesiologically? Is it possible to conceive of communities of care that combine competency and faith, to the effect of delivering good practices, without a built-in inclination towards heavy burnouts?

Two things matter here. First, what does the definition of Christian communities of care as communities of practice imply for the Church’s self-understanding and self-reflection? Second, what does this imply for practices of care that being the Church entails?

We start with the first question. The self-understanding of many churches in the Netherlands, and the West in general, was wrought in the heydays of institutional Christianity, during the Christendom period. Implicitly and pre-reflexively, these more or less fixed institutional presuppositions are inclined to define being the Church in terms of visions, ideas, and dogmas. This resulted, as Nicholas Healy (2011, p. 37) describes, in “blueprint ecclesiologies [that] frequently display a curious inability to acknowledge the complexities of ecclesial life in its pilgrim state”. This causes intense feelings of disintegration, uncertainty, and not-knowing as society changes. The shift from institutional and fixed to other, more ‘liquid’ forms of being Church (Ward 2017) is visible in many places, as the examples above indicate. It is this liquification and uncertainty that leads the Church into a phase that has been labelled the ‘liminal phase’ (Fairhurst and Rooms 2021). Acknowledging this development is one of the first and key competencies asked for in current ecclesiological thinking, because, as another descriptor states, “The fragility of communities of faith, organizations, and ‘systems’ is more often felt before it is spoken aloud” (Benac 2022, p. 2). This experience and acknowledgment therefore spark the reflexivity of the community-members. They must find words, new concepts, and insights to grasp what is going on and what it entails for them. So, the Christian community, as a community of practice, needs to foster a culture of reflexivity. Such a culture is embodied by what has been called ‘theological reflection’, a practice that sets goals like “the induction and nurture of members”, “building and sustaining the community of faith”, and “communication the faith to a wider culture” (Graham et al. 2005, pp. 10–11). Communities of practice, therefore, are necessarily also communities of reflection.

Reflection, however, is a rather opaque and blank concept. It must be filled by the practices it is sparked by. Christian communities of practice have a long history of explicitly and consciously taking reflection as part of their practice seriously. It is part and parcel of their core identity markers: the celebration of the sacraments of which celebrating the Eucharist is deemed to be the core practice. In Biblical accounts of celebrating the Eucharist, the complexities of living together communally, and being related to God in Christ, come to the fore. They are not countered, however, by pointing at some ideals of community but by practicing the Eucharist reflexively. Reciting the Biblical narratives, eating and drinking and sharing, thus evokes and sparks the reflexivity. The Biblical example of celebrating the Eucharist in Corinth shows that it implies questioning the community’s ethics of care (1 Corinthians 11). In Corinth, the rich gather earlier, they eat too much, get drunk, and nothing is left for the poor. Theological reflection on such practice asks what kind of community they are: do the rich take care of the poor, do they share their being and goods, what are the power-structures implied, et cetera.

Being a reflexive Christian community of practice, therefore, immediately puts the finger on attentiveness as the first of Tronto’s characteristics of an ethics of care. Do we see the other people in the community, in their need? Or do we merely fulfill our own desires at the Lord’s table? It evokes reflection on the responsibility the rich have for the poor. And, in the case of Paul’s letter to the Christian community in Corinth, following up on his indictment regarding their practicing the Eucharist, he points to the unity in diversity of the community. This contrast between the sharing of the meal and the gross violation of the reciprocity that is exposed, points at the responsiveness that is undergirded by the principal equality of the community’s members. Finally, there are different competences among the members that contribute to the well-being and fulfillment of the congregation’s mission in the world (1 Corinthians 12). Christian communities of care could easily adjust their level of commitment and target-group to the contextual givenness of their situation. From attentiveness flows the awareness of one’s responsibility, which leads to the appropriate responsiveness and the cultivation of the necessary competency. Churches may differ from place to place in what kind of commitment they envision appropriate. Interestingly, however, recent examples show that once the step is made towards any commitment, the reflexive practices lead to an increasingly serious commitment (Brigham 2022; Barton 2022; Raffety 2022).

4.3. Practices of Christian Communities of Care

The remark on competences brings us to our second question on the implications for the broader web of Church-practices, the Christian community as a community of care. From the Eucharist as the core practice, all other practices do spark. In the chapter on the community’s diverse gifts and competences, Paul states that they serve one goal: the building up of the community, as they are the work of the Spirit. In many ways the Biblical times differ from ours, of course. The post- or late-modern de-institutionalized and liquified Church, however, may mirror itself in these pre-modern Biblical texts. Whereas gifts like healing, or helping, or guidance (1 Corinthians 12:28) in modern times have been drawn out of the church into the public sphere, they once were part of the practice of the faithful community. Over against modern privatization of faith, that has confined it to being a specific, merely spiritual aspect of human life, this implies a quite holistic approach to being a Church and being Christian. We might best use the term ‘salvation’ to cover this holistic approach, and ask for its relation to the concept of ‘care’. Without going into detail, salvation can be said to encompass care, so that while salvation might be more than care, it is never less. As the philosophers of religion Martin Riesebrodt (2010) and C. Smith (2017) contend, religion is about being able to live together in a violent world, which they call salvation. For this salvation we turn to God, by exercising religious practices. When we focus a bit more on what such salvation contains, the template of salvation by Clive Marsh (2018, p. 163) might be helpful. He identifies four aspects of salvation, which seek to identity what people need to be saved from, what they are saved for, the means by which salvation occurs, and the community and its narratives into which people are saved. Salvation, then, immediately is tied up with communal practices of faith and reflections on the context people live in. The Christian community’s being a community of care is part and parcel of the place it has in the whole of salvific practices.

Let us unpack this notion of salvation. For, the debate on the place and contribution of Christian communities to the care people need in our current (Western) context might be greatly served by this broad concept of ‘practices of salvation’. If it is true that religion is about practices to cope with human needs (Riesebrodt), what does the specific character of Christian communities bring to the care we need? As we saw in the two examples above, it is about fostering attentiveness, responsibility, responsiveness, and competence. This fostering, however, is not merely attuned to functionally improving behavior, as if Christians just ought to learn competencies to take care of others. It is about fostering a culture of being careful, that obviously takes notice of looking out for the poor, for the vulnerable, and helping where needed. But this culture does something more: it encompasses even its practical and moral failures. A Christian community of care is a community of practice that both fosters practices of care, and encompasses those failing to do so and the failures resulting from that. We pointed to such practical and sometimes systemic failures in the examples of L’Arche and Hart van Vathorst. The courage to still go on, to reflect, and acknowledge frailty and failure, and to find ways of improving, change and adaptation, can be found in the Christian gospel of salvation. This highlights our culture’s being prone to mere horizontal, buffered experiences of oneself and community. For communities of care to really flourish, the transcendent and religious is quite important. That is what embodiments of salvific practices, as traditioned by the Christian church, can bring to the discussion of communities of care. Salvation might be the framework in which ethics of care and communities of care might find their critical and yet constructive framework.

5. Concluding Implications for Practices of Care

What do these reflections on Christian communities of care, against the background of Dutch (Western) societal developments around care (Section 1), bring to an ethics of care? Can salvation, as an encompassing framework and religious practice, be of help? The ‘turn to care’ (Section 2) exemplified the wish for more than functionalist and reductive approaches towards the care of people’s needs. It stands for a broader, almost anthropological presupposition that care is “a species of activity that includes everything we do to maintain, contain, and repair our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible. That world includes our bodies, ourselves, and our environment” (Tronto 1993, p. 103). This holistic approach to care as a web of practice is exemplified in the two cases we studied (Section 3). Our ecclesiological and theological reflection turned our attention to the broad concept of salvation (Section 4).

What does all this imply for reflections on an ethics of care? We would, first, contend that a practical-theological approach to describing and assessing ecclesial practices is an important means to see where, how, and to what extent care is practiced in real life. Again, such a description also involves writing about failing practices. Conscientious empirical research then helps in distinguishing between idealistically imposing theology onto reality, and inductively discovering what theology is presenting itself in ecclesial practices (Martí 2022, p. 472). For an ethics of care, this neither means that we nostalgically project ideals of care-taking communities onto the past days, in which the devastating consequences of modernity were not present and care was taken of everyone by everyone. Nor does it mean that we look for contextless ideals of communities that as examples should be projected on any Christian community. It does mean that we have the obligation to research where and how Christian communities face the challenges of our time, to look for possible connections that might help, enlighten, and inspire others.

Secondly, this strategy helps us to perform what practical theology might do best: to offer “critical, theological reflection on the practices of the church as they interact with the practices of the world, with a view to ensuring and enabling faithful participation in God’s redemptive practices in, to and for the world.” (Swinton and Mowatt 2006, p. 6).

Third, this turn towards practices of Christian communities of care offers possibilities to see ‘care’ as it presents itself to us in its fundamental reciprocity. The specific vocabulary that is currently used points to this. We are used to talking about ‘rediscovering’, ‘reimagining’, or ‘disclosing’ Church (Watkins 2020; Ruddick 2020; Hansen and Leeman 2021; Benac 2022). There is an aspect of genuine gift and receptivity in this vocabulary that attunes to the very heart of care. We do not functionally make or develop communities of care, we receive them and are formed by them. Care expresses a relational anthropology that highlights the very contextual shape of being human. It is about helping reality, in all its diversity, to flourish. Christian communities that receptively discover their calling will attentively look and seek, responsibly discover the need, competently act from Christian practical wisdom, and responsively perceive others not only as objects of care but as fellow human beings.

Fourthly, this shows that Christian communities of care, practicing their faith, are well attuned to live out their moral sources. Practices of care are intertwined with other ‘sourcing practices’. Reading the Bible, praying, celebrating the Eucharist, coming together, hospitably making place for one another—these practices are inextricably interwoven with caring in the palette of ecclesial practices. This reinforces the moral capacity and sustainability of such communities.

Finally, Christian communities of care in the past and present show many (and severe) shortcomings. The receptivity it confesses, then, helps us to become and stay humble. Communities of care are not the success-stories of human endeavors. They spring from divine gifts, as the concept of salvation makes clear. Its practices like the Eucharist are therefore more than just expressions of love and commitment (Brigham 2022, 92 ff; Spurrier 2019, pp. 86–87, 187–88), they practice salvation: both testifying and embodying God’s saving love, and sharing salvation.

Concludingly, we can state that, at least for the Dutch context, stressing the value of Christian communities of care is relevant. We live in a context that increasingly undervalues a governmental obligation to care, which leads to an increasing lack of access to care and exhaustion among care-professionals. In this context, Christian communities that practice care both explicitly acknowledge the human need for care and provide places for communally drawing on spiritual and moral resources to address these needs. The Christian communities of Hart van Vathorst and L’Arche show that competency for the technical aspects of care, as well as the spiritual and communal resources needed to sustainably provide it, and the mutually received blessing in living together, can be summarized as practices of salvation. Coming back to our fourfold heuristic tool from Section 4, Christian communities of care can identify themselves, to find out what role they play and could play regarding ‘care’.

Without defining communities of care in exclusively Christian terms, we argue that Christian communities of care are well equipped for sustainable caregiving. Not only by moral and spiritual resources for the caregivers, but also by providing a life-context for mutual engagement of those who give and receive care—even to the point where these roles swap and traditional recipients become bestowers, and traditional givers become receivers. This is what Brock alludes to when writing about “The Peculiar Togetherness of the Body of Christ” (Brock 2019, pp. 201–24). This mutuality is the most intense embodiment of reciprocity as a token of a world that in its fullness is yet to come. We also stress these communities’ need for humility. Examples of failure and intense damage caused by all sorts of power abuse are abundant, as the case of L’Arche makes clear. It may be argued that such moral failure is not only a fact but is even intended to be addressed by Christian practices like the Eucharist (cf. Schaeffer 2022). Christian communities of practices of care may thus be examples of God’s salvific action through human participation. The ecclesial practices of such communities of care are fostering practices of salvation in the broadest sense of the word.

Author Contributions

Everything was done together by the two of authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | Although it is difficult to write about Vanier after the horrible news broke that during his life, he sexually abused multiple women (without disabilities), we do write about him here, as this experience became formative for the L’Arche communities. L’Arche international has firmly condemned Vanier’s actions. L’Arche communities to this day continue to be inspiring places of care and community. |

References

- Barton, Sarah Jean. 2022. Becoming the Baptized Body: Disability and the Practice of Christian Community. Waco: Baylor University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, Dorothy C., Kathleen A. Cahalan, Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore, James R. Nieman, and Christian Scharen. 2016. Christian Practical Wisdom: What It Is, Why It Matters. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Benac, Dustin D. 2022. Adaptive Church: Collaboration and Community in a Changing World. Waco: Baylor University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brigham, Erin. 2022. Church as Field Hospital: Toward an Ecclesiology of Sanctuary. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, Brian R. 2019. Wondrously Wounded: Theology, Disability, and the Body of Christ. Waco: Baylor University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ceyrac, Odile. 1981. La Forestière. Letters of L’Arche 28: 23. [Google Scholar]

- Cushing, Pamela. 2010. Disability Attitudes, Cultural Conditions, and the Moral Imagination. In The Paradox of Disability: Responses to Jean Vanier and L’Arche Communities from Theology and the Sciences. Edited by Hans S. Reinders. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- de Hart, Joep J. M., and Pepijn van Houwelingen. 2018. Christenen in Nederland: Kerkelijke Deelname en Christelijke Gelovigheid. SCP-Publicatie 2018–32. Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau. [Google Scholar]

- Dow, Keith E. 2019. Call, Encounter, and Response: Loving My Neighbour with Intellectual Disabilities. Ph.D. thesis, VU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Fairhurst, Rosemary, and Nigel Rooms. 2021. Crossing Thresholds: A Practical Theology of Liminality in Christian Discipleship, Worship and Mission. Cambridge: Lutterworth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Elaine, Heather Walton, and Francis Ward. 2005. Theological Reflection: Methods. London: SCM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greig, Jason F. R. 2018. The Disarmed Community: Reflecting on the Possibility of a Peace Ecclesiology in the Light of L’Arche. Ph.D. thesis, VU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Collin, and Jonathan Leeman. 2021. Rediscover Church: Why the Body of Christ Is Essential. Wheaton: Crossway. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, Nicholas M. 2011. Ecclesiology, Ethnography, and God: An Interplay of Reality Descriptions. In Perspectives on Ecclesiology and Ethnography. Edited by Pete Ward. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, pp. 182–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hütter, Reinhard. 2001. The Church. The Knowledge of the Triune God. Practices, Doctrine, Theology. In Knowing the Triune God: The Work of the Spirit in the Practices of the Church. Edited by James Joseph Buckley and David S. Yeago. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Klaver, Klaartje, Eric van Elst, and Andries J Baart. 2014. Demarcation of the Ethics of Care as a Discipline: Discussion Article. Nursing Ethics 21: 755–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L’Arche. 2020. Summary Report from L’Arche International. L’Arche International. Available online: https://www.larche.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=139bf786-3bbc-45f5-882a-9f78bfbc99e9 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- L’Arche. n.d. About L’Arche. L’Arche.Org. Available online: https://www.larche.org/about-larche/ (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Leget, Carlo, Inge van Nistelrooij, and Merel Visse. 2019. Beyond Demarcation: Care Ethics as an Interdisciplinary Field of Inquiry. Nursing Ethics 26: 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacIntyre, Alasdair C. 1984. After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mannering, Helenka. 2020. A Rapprochement between Feminist Ethics of Care and Contemporary Theology. Religions 11: 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, Clive. 2018. A Cultural Theology of Salvation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martí, Gerardo. 2022. Ethnography as a Tool for Genuine Surprise: Found Theologies Versus Imposed Theologies. In Wiley Blackwell Companion to Qualitative Research and Theology. Edited by Pete Ward and Knut Tveitereid. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 471–82. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, John. 1995. The Careless Society: Community and Its Counterfeits. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson, Per. 2011. Majority Churches as Agents of European Welfare: A Sociological Approach. In Welfare and Religion in 21st Century Europe. Edited by Anders Bäckström. Farnham and Burlington: Routledge, pp. 15–59. [Google Scholar]

- Raffety, Erin. 2022. From Inclusion to Justice: Disability, Ministry, and Congregational Leadership. Waco: Baylor University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Riesebrodt, Martin. 2010. The Promise of Salvation: A Theory of Religion. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ruddick, Anna. 2020. Reimagining Mission from Urban Places: Missional Pastoral Care. London: SCM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, Hans. 2022. Concrete Church: Qualitative Research and Ecclesial Practices. In Wiley Blackwell Companion to Qualitative Research and Theology. Edited by Pete Ward and Knut Tveitereid. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 151–61. [Google Scholar]

- Scharen, Christian. 2015. Fieldwork in Theology. Exploring the Social Context of God’s Work in the World. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- SER. 2020a. Summary of Advisory Report ‘Working for the Care Sector’, SER Report 21/04. Available online: https://www.ser.nl/-/media/ser/downloads/engels/2021/working-for-care-sector.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- SER. 2020b. Zorg Voor de Toekomst: Over de Toekomstbestendigheid van de Zorg. 02. Sociaal-Economische Raad. Online Report. Available online: https://www.ser.nl/-/media/ser/downloads/adviezen/2020/zorg-voor-de-toekomst.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Smith, Christian. 2017. Religion: What It Is, How It Works, and Why It Matters. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, James K. A. 2013. Imagining the Kingdom: How Worship Works. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Spurrier, Rebecca F. 2019. The Disabled Church: Human Difference and the Art of Communal Worship. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinton, John, and Harriet Mowatt. 2006. Practical Theology and Qualitative Research. London: SCM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tamminga, Koos. 2020. Receiving the Gifts of Every Member: A Practical Ecclesiological Case Study on Inclusion and the Church. Kampen: Summum Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Tronto, Joan C. 1993. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronto, Joan C. 2015. Who Cares?: How to Reshape a Democratic Politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vanier, Jean. 1995. An Ark for the Poor: The Story of L’Arche. Ottawa: Novalis. [Google Scholar]

- Vanier, Jean. 2007. Community and Growth, 2nd ed. London: Darton, Longman & Todd. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, Benjamin S. 2016. Welcome as a Way of Life. Eugene: Cascade Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, Pete. 2017. Liquid Ecclesiology: The Gospel and the Church. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, Clare. 2020. Disclosing Church: An Ecclesiology Learned from Conversations in Practice. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).