Abstract

This article examines the work of seven contemporary artists whose aesthetics exemplify the “lived” experience of Islamic mysticism or Sufism (Arabic tasawwuf) within a European context. The work of artists born in Islamic majority countries and familiar with “traditional” Sufi idioms and discourses, but now immersed in Western culture, is often associated with “diasporic art”. From this hybrid perspective some of their artistic narratives reconfigure or even subvert the “traditional” Sufi idioms, and do so in such a way as to provoke a more profound sensory experience in the viewer than traditional forms of art. Drawing upon recent methodological tendencies inspired by the “aesthetic turn”, this study explores post- and decolonial ways of thinking about Sufi-inspired artworks, and the development of a transcultural Sufi-inspired aesthetic within the context of migration and displacement over the last half-century.

Keywords:

Sufism; contemporary art; aesthetic turn; diasporic art; decoloniality; migration; transculturality 1. Introduction

During the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, Islamic mysticism, or Sufism (tasawwuf)1, has spread extensively throughout European society, engendering new cultural forms. Contemporary art has not only vastly extended the traditional boundaries of aesthetic culture; it is also drawing upon a far more variegated range of bodily and sensory experiences. Traditionally, Sufis have often fostered the arts within Islamic societies, whether it be music, poetry, painting, or calligraphy. Today’s Sufis, whilst still practicing these traditional mediums, also express themselves through plastic and visual arts, photography performative arts, architecture, and even more exotic forms of art such as hip hop and rap (cf. Akbarnia 2018, pp. 197–217).

In this article I examine the work of seven contemporary artists who engage with the applied aesthetics of the “lived” Sufi experience (Streib et al. 2008, pp. ix–xiii), often based on immediate sensation or intuition. The approach is supported by a more “participatory” definition of “aesthetics” to present insights into works of art inspired by Sufi mysticism. Mysticism provides a religious and aesthetic framework through which to articulate subjective sense experience and feeling—internal sensations that manifest externally. Particular attention is accordingly paid to the idiom used by the artists to translate their mystical experience(s), whether it be through text, image or sound (Schmidt 2016).

The works of art are viewed as manifestations of transcultural frames of reference (Freyre 1986), as matrices where cultural elements are shared and entanglements take place. It focuses on the work of artists, many born in Islamic majority countries, who are familiar with “traditional” Sufi idioms and discourses, but are now immersed in Western culture, a milieu often associated with “diasporic art” (cf. Svašek 2012). This hybrid cultural background allows them to extend the Sufi vocabulary beyond its original confines and to develop new narratives, reconfiguring and at times even subverting the original idioms. The increasing worldwide cross-fertilization of cultures is also to be seen in the context of migration and displacement, exile and trauma, which underpin many contemporary artistic forms of expression (Bal 2008, p. 37). The influx of converts to a number of Sufi orders and the practice of some Sufi communities not to require their followers to formally convert to Islam has also led to a degree of cultural and religious fluidity. This fluidity makes contemporary Sufism a dynamic case study within the evolving landscape of contemporary Islam.

The research builds upon current theories and previous research on Islamic art2 and aesthetics (ancient Greek aisthetikos, “relating to sense perception”) (e.g., Grabar 1977; Necipoğlu 2015; Tabbaa 2001). The term “aesthetics” was coined by the eighteenth-century German philosopher Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten (1714–1762) who in his work Aesthetica (part 1, 1750; part 2, 1758) established a new science of knowledge based on the senses. Baumgarten defined aesthetics as a “science of sense-based cognition” (scientia cognitionis sensitivae, §1), which was synthesized in the Critique of Judgment by Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), hugely influential in the development of western aesthetics. By the 19th century this understanding had been narrowed and aesthetics was associated with a normative philosophy of art and beauty.

While the term “aesthetics” has no direct Arabic equivalent,3 José Miguel Puerta Vílchez’s pioneering Historia del pensamiento estético árabe: Al-Andalus y la estética árabe clásica (translated as Aesthetics in Arabic Thought: From Pre-Islamic Arabia Through Al-Andalus, see Puerta Vílchez 1997) showed that medieval Islamic thinkers’ contribution to Arab humanism helped shape the field of aesthetics in the West.4 Some scholars such as Oludamini Ogunnaike (following Seyyed Hossein Nasr 1997; and Titus Burckhardt 1985) argue that “In fact, beauty is a criterion of the authentically Islamic. There is nothing Islamic that is not beautiful”, adding that “Islamic arts … serve as a ladder from the terrestrial to the celestial, from the sensory to the spiritual” (Ogunnaike 2017, pp. 1–15). Yet this “traditional” approach has its limitations, and other scholars have sought to apply a wider socio-cultural lens to Islamic aesthetics while at the same time drawing upon historical material to support their more contextualized approach (Gonzalez 2016; Elias 2012).

In this study I seek to present a more nuanced and multifaceted understanding of the role of art and aesthetics. I use aesthetics in the sense of Aristotle’s (384–322 BC) notion of aisthesis, understood as organizing “our total sensory experience of the world and our sensitive knowledge of it” (Meyer 2009b, pp. 714–19; cf. Koch 2004, pp. 330–42; Cancik and Mohr 1988, pp. 121–22). The study focuses on mystical Islam or Sufism, and is situated within a larger interdisciplinary framework that seeks to elicit a more contextualized, embodied understanding of religious aesthetics (Cancik and Mohr 1988; Barth 2003, pp. 235–62; Meyer 2009a; Mohn 2012; Traut and Wilke 2015; Grieser and Johnston 2017). Such an aesthetic practice encompasses sensory perception in religious experience and its associated psychosomatic processes. “Sense” is taken to include not only sight, hearing, taste, touch and smell, but also the sense of time and space and kinesthetic phenomena (Hirschkind 2006; Marks 2010; Necipoğlu 2015, pp. 23–61; Gill 2017; Abenante 2017, pp. 129–48; Frembgen 2020, pp. 225–45; Akkach 2022).

A different interpretation of aesthesis has been developed in the works of decolonial thinkers such as Walter Mignolo (2007, 2011) who—in response to postcolonial ways of thinking (for instance, Edward Said’s canonical Orientalism, see Said 1978)—deliberately rejects the idea of a single universal aesthetic traditionally posited in the Western tradition, rethinking the very concepts of aesthetics and art. In contrast to Eurocentric aesthetic ideology, decolonial aesthetics postulates a “pluriversality” of aesthetics (Mignolo 2011; Mignolo and Vázquez 2013; Tlostanova 2017, p. 29). Migration processes also entail the unfolding of an aesthetic of transcultural formation, whereby transculturation is understood as the “effects of cultural translations” (Kuortti 2015).

Drawing on such recent methodological tendencies inspired by the “aesthetic turn”5, my transdisciplinary exploration focuses on the embodied aesthetic engagement of contemporary artists with Sufi practices, rituals, and conceptual discourses. It combines the approach of several disciplines, especially Sufi studies, visual anthropology, and (art) history, integrating both emic (“insider”) insights and etic (“outsider”) analysis, in order to assess the data from subjective as well as objective perspectives (Arweck and Stringer 2002). Since most artists use a figurative visual language in their works, the article also touches upon ongoing debates in Islamic studies about the prevailing biases that portray Islam as an iconoclastic religion and Muslims as opposed to figural representation (Flood 2002; Gruber 2019).

2. Seven Case Studies

The article includes seven case studies that examine different, though interconnected, configurations which expand on the aesthetic junctures of embodied sensations (Birgit Meyer’s “sensational forms”, Meyer 2009b, 2009c, p. 972, n. 58; Meyer and Stordalen 2019) and the intersensorial nature of Sufi perception. Each study presents a different kind of aesthetic form of “lived” Sufi experience—“the skin of religion” to use a metaphor coined by Brent S. Plate (2012)—an artist has chosen in order to create meaning. Plate’s evocative metaphor alludes to the permeable contact zones and sensory receptors that cover the surface of the entire body and serve as connective tissue, a membrane that is constantly renewed. With their aesthetic praxis the artists address both Sufi and multi-faith audiences.

The first case study discusses religio-aesthetic calligraphy of the German Naqshbandi Sufi Ahmed Peter Kreusch which embodies spiritual practice, corpothetics (a term created by Pinney 2004, pp. 8, 19), and creative imagination (Johnston 2016, p. 197).

The second study presents the Iraqi-Swedish artist Amar Dawod’s allegorical works inspired by the text The Tawasin of the early Sufi mystic al-Hallaj. Living in exile and grappling with the harrowing experiences of a homeland devastated by war, sectarian conflict and foreign occupation, Dawod expresses the profound connection between his art and the senses by focusing on the experience of dhawq (“taste” or “disposition”). An act of looking not only with his eyes but also with his heart, resembling a kind of synesthesia, enables the artist to “reconnect” to the divine. Central to his work are symbolic meanings and ideas evoked by sensory experiences.6

In Sufism, symbols are also viewed as a sensory or aesthetic means of conveying knowledge (cf. Erzen 2007, p. 71; Pinto 2017, pp. 90–109). In this context, symbolic representations are realities inherent in the nature of things. As we move from painting to photography, sculpture, video, and installation, we encounter the Italian multidisciplinary artist and Senegalese Baye Fall Sufi, Maïmouna Guerresi (the third study), who sees her artwork as a medium that transcends the visual and embraces narrative orality and tactile experience.

The fourth study focuses on the soundscapes of the French Sufi rapper Abd Al Malik whose music directly activates sensory experience. It promotes the cultivation of certain emotions, modes of banlieue expression and aesthetic tastes, as well as social justice, emphasizing Abd Al Malik’s struggle against racism and neo-colonialism.

In the work of the Iraqi-British mixed-media artist Hanaa Malallah, the fifth case study, the lived experience of war and themes of exile and trauma feature prominently. Much of her work draws inspiration from the twelfth-century Sufi classic The Conference of the Birds of the Persian mystic Farid al-Din ‘Attar (d. ca. 1221). Malallah is known for her creation of the “ruins technique”, a technique which evokes not only an aesthetic but also a “visceral” reaction in the viewer.

Finally, in the sixth and seventh studies, I will address new dynamics, especially regarding the use of media: the virtualization of Sufism, and its multi-faith engagement. Greek director, playwright, visual artist and Inayati Sufi, Elli Papakonstantinou designed and directed a live musical broadcast remotely during the pandemic (the sixth study). The seven-act play was written by Noor-un-Nisa Inayat Khan, who was executed in 1944 at Dachau in Germany. The digital opera was performative (theatrical and cinematographic), sensorial in its performance (combining voice, sound and vision) and aesthetic (using figures, colors, and architectural spaces).7 It presents the spiritual quest of Noor’s father, Sufi leader Hazrat Inayat Khan, a spiritually uplifting journey in symbols of the visible, sensible world, the “place of encounter” between the intelligible and phenomenal worlds: the point where they meet is the barzakh, the “world of image”.

One of the most important projects of the Paris-based Algerian artist and Tijani Sufi Rachid Koraïchi is the newly opened Le Jardin d’Afrique in southern Tunisia (the seventh study). A visit to the multi-faith memorial cemetery triggers a succession of feeling, aroma, sight, sound and taste; it is an intersensory, “synesthetic” experience. The examination of the religious and aesthetic sensibilities at this shared sacred site parallels those of Koraïchi’s artworks, in which creative expressions are entangled with forms of sensory perception.

Case Study 1Dot, Circle and AlifSpiritual practice shapes all the arts in Islam.Ahmed Kreusch (2017, p. 182)

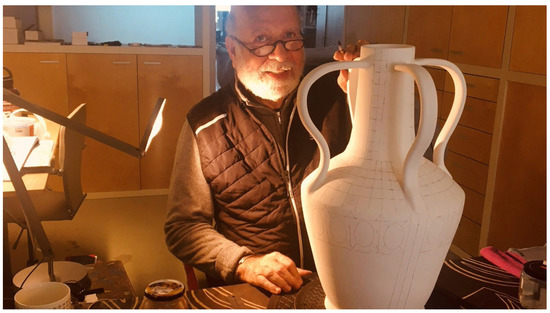

Spiritual striving and meditation lie at the heart of the work of the calligrapher and painter Ahmed Peter Kreusch (b. 1941), who studied with Hubert Berke (d. 1979) at the Technical University of Aachen and with Joseph Beuys (d. 1986) at the Düsseldorf Art Academy. Born into a Catholic family, Kreusch converted to Islam in 1980 and began following the teachings of the Egyptian Sufi Shaykh Salah al-Din Eid. Salah Eid was appointed Rifa‘i Shaykh by the Cairene Shaykh Mahmud Ahmed Yasin al-Rifa‘i in 1977, but became widely known as a murshid (senior teacher) and representative of the Burhaniyya in Germany. When Salah Eid died in a road accident in 1981, Kreusch joined the community of the Turkish-Cypriot Shaykh Nazim Adil al-Qubrusi al-Haqqani (1922–2014), the leader of the Haqqaniyya Sufi Order of the Caucasian Naqshbandiyya-Mujaddidiyya-Khalidiyya tradition. Although he still considers himself a Rifa‘i today, Kreusch took this step in order, as he says, “not to be alone” (Kreusch, interview with author on 15 December 2022). In the course of studying the Arabic language and script, he developed a form of “calligraphic expressionism” from about 1987 onwards (Kreusch 2017, pp. 182–83). These calligraphic expressions, Kreusch says, require intense concentration. His “script images” arise from the oft-repeated writing of the same holy letters and words, a Sufi remembrance ritual referred to as dhikr Allah. This involves repetitive invocations of Allah’s names (ninety-nine in all), and various religious formulas in Arabic (Al-Ghazzali 1992), a practice evoking religious experiences grounded in bodily sensations (Hirschkind 2006). The calligraphic dhikr (literally, “recollection”) is practiced to tame and eventually purify the artist’s own self, or nafs, in his quest to come closer to God (Kreusch, interview with author on 4 and 5 May 2019; cf. Al-Haqqani al-Rabbani 2018, p. 130).

Aesthetic contemplation, mediation, sensory awareness and breathing exercises allow him to release the physical and creative forces that guide his pen. “When writing, I try to devote myself completely to the content of the words from the holy Qur’an and I am often amazed myself at the Gestalt of the writing that emerges in the process. Through further “practice” everything superfluous and unclear disappears until I feel a trace of the sublime content wafting across through the calligraphic image. … associations, fantasies, imaginations that arise from these images of devotion/meditation are allowed and desired” (Kreusch 2017, p. 182, emphasis added).8 Kreusch’s account of the imagination is consistent with that of the influential thirteenth-century Sufi mystic and philosopher Ibn al-‘Arabi (d. 1240) and other Sufi thinkers. They see spiritual imagination (khayal) not as something unreal, but as a creative and perceptual repository used to attain spiritual experiences that embody pure meanings and spiritual realities in sensory forms (Zargar 2011; Akkach 2022, p. 43).

The vitalizing process of breathing and the uninterrupted flow of movement are paramount in Kreusch’s “bodily praxis of worship” (Meyer and Verrips 2008, p. 25). The dhikr begins on the exhalation with al-, “to empty himself of himself”, and continues on the inhalation with lah, “to fill himself with divine presence”. In this context, the word nafas (“breath”) is connected to the wider notion of self or soul (nafs), which is central to the Sufi path towards “the purification of the soul” (tadhkiyat al-nafs).

The ritual practice is buttressed by Kreusch’s long-term experience as a movement and breathing therapist trained in the school of Elsa Gindler (d. 1961) and her student Frieda Goralewski (d. 1989), pioneers of body awareness techniques and somatic psychotherapy (Buchholz 1994, pp. 141–53; Franzen 2005). Kreusch has described this practice as enabling him to be completely present in the here and now (Kreusch, interview with author on 4 and 5 May 2019). Only by leaving the material world can he access the spiritual dimension, the inspiration for which comes (in the words of Kreusch’s spiritual guide, Shaykh Nazim) from “a heavenly grant” (Al-Haqqani al-Rabbani 2000, Sohbet 115). This is underscored by the cosmological significance attributed to the pen (al-qalam) and “the preserved tablet” (lawh al-mahfuz) (Q 68; 96:1–5; 85:21–22) (Al-Haqqani al-Rabbani 2000, Sohbet 182).

Kreusch explains that the pen cannot touch the paper to create anything without first making a dot. It all begins with the perfect geometrical point, or the alphabetical dot, an important symbol in Sufism. It is seen as a “primordial dot”, a symbol of divine ipseity (essence), the basis of creation (Schimmel 1987, pp. 350–56). According to Sufi teachings, the dot is not simply the origin of all letters, but an act of divine creation, the beginning and origin of everything. Husayn b. Mansur al-Hallaj (executed 922 in Baghdad), one of the most important early mystics of Islam, further explains the close connection between the circle and the dot by saying that “[t]he circle has no entrance and the dot at the center is the truth” (cf. Rasmussen 2007). As Shaykh Nazim says, “We only know a little dot of all this which makes us wonder, and we can only wonder about the Endless Greatness and the Lord’s Endless Oceans of Power” (Al-Haqqani al-Rabbani 2000, Sohbet 95).

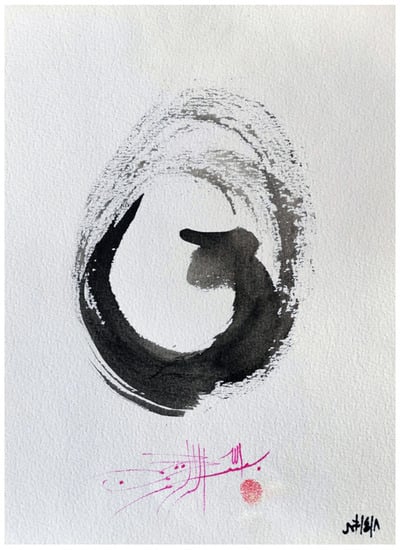

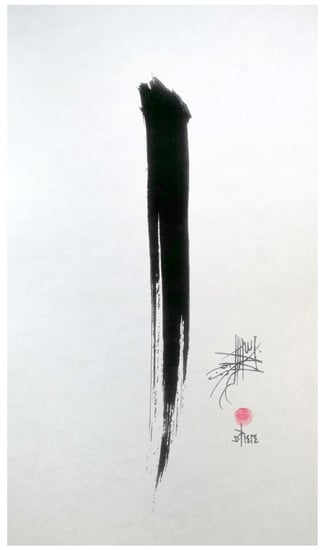

The Arabic letters also have numerical values that play a significant role in Sufi interpretations. The dot denotes zero. It then develops into a circle. The seemingly non-existent develops into the all-existent, also expressed in the divine name Hayy, the living God (Q 2:255; 3:2; 20:111; 25:58; 40:65), for God is the central focus of life (al-hayat) (Figure 1). The first of the letters arising from the dot is the alif, “a”, written as a vertical stroke, the first letter of the Arabic alphabet and the first letter of the name of God, Allah. The alif is equivalent to one. A central aesthetic of the alif, says Kreusch, is the unobstructed breath emanating from the heart (interview, 4 and 5 May 2019). For many Sufis, the alif is a powerful metaphor for the purified state toward which the spiritual seeker aspires to return (Figure 2). Following a difficult eye operation, after which he did not know whether he would be able to see again, Kreusch painted a series of alifs with his eyes closed.

Figure 1.

Ahmed Kreusch, Hayy, 1998. Ink on paper. 19 × 24 cm. © Ahmed Kreusch.

Figure 2.

Ahmed Kreusch, Alif, 2004. Ink on paper. 12 × 24 cm. © Ahmed Kreusch.

That Kreusch’s practice of “calligraphic expressionism” is reminiscent of Far Eastern calligraphy derives from his use of “Far Eastern” materials such as ink, paintbrush and bamboo pen, but also from a comparable “method of ‘disciplined painting’: in ever new attempts the motif is reduced to the absolutely necessary in order to convey its message as simply and as beautifully as possible to the viewer” (Kreusch 2017, pp. 182–83). He signs his works by pressing the tip of his right forefinger dipped in red seal paste onto the paper. The artist’s contemplations of the sacred letters also hang on the walls of the Sufi lodge (dargah) of Shaykh Hassan Dyck (b. 1946) in Kall near Cologne, Germany, known as Osmanische Herberge, or Ottoman hospice. They contribute to the realization of the Islamic emanationist notion of the “unity of being”, or wahdat al-wujud, in this Sufi community, of which Kreusch is a member (Kreusch, interview with author on 4 and 5 May 2019).

Case Study 2Al-Hallaj’s The TawasinWhen I begin the act of creation, millions of imaginary birds haunt me,waiting in the distant horizon. I wait too, in the expectationof a single glimpse; they appear and then fly off again.Amar Dawod (2010)

Amar Dawod’s visually allegorical account refers to birds that spring from his intuitive cognition. At the beginning of the Iran-Iraq war (1980–1988), the artist (b. 1959 in Baghdad) left his homeland to live first in Lodz, Poland, and then in Västervik, Sweden. Unlike other refugees who experienced the suffering of war and exile, Dawod’s spiritual and mystical understanding of the world enabled him to avoid focusing on calamity and instead to infuse his experimental mixed-media artwork with what he calls “a poetic energy that praises the beauty of the world”. It allows him to see “[p]ainting, as … a kind of liberation and thrilling road, even if that road is sometimes bumpy” (Dawod 2010).

This worldview owes much to Sufi spiritual vision, which has been central to Dawod’s artistic career. In the mid-1970s, while studying at the Institute of Fine Arts in Baghdad, he began to engage with the Sufi discourse of the Persian-born Husayn b. Mansur al-Hallaj, one of the most original and charismatic figures in Islamic spirituality. His interpretations of al-Hallaj’s teachings were to shape much of his later work: “[A]lthough I am a descendant of a Communist family, I came out of the cloak of al-Hallaj” (Faruqi 2011, p. 62).

The physical manifestation of al-Hallaj’s influence on Dawod’s artistic output increased significantly from 2010 onwards, when the artist created a series of paintings based on al-Hallaj’s enigmatic Kitab al-Tawasin (The Tawasin), which was probably written in prison. The title refers to the mysterious letters ta-sin at the beginning of Sura 27. The Tawasin also contains the parable of the butterfly that plunges into the candle, reflected in one of the most popular Sufi sayings ascribed to the Prophet Muhammad, “die before you die!” (mutu qabla an tamutu), implying a metaphorical death to the cares and concerns of the material world (dunya) by reigning in the desires of the self, prior to physical death. To achieve “death before dying” was to attain spiritual union with the divine beloved (Karamustafa 1994, pp. 21, 41).

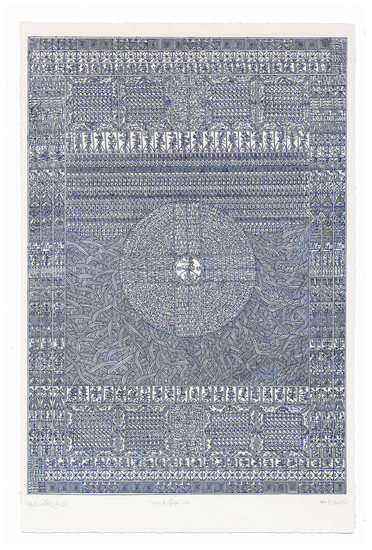

With pencil, ink, pastels, watercolor, acrylic paint, charcoal and mixed-media on paper, Dawod interprets al-Hallaj’s verses by depicting a range of human figures, body parts, and various codes, symbols, and patterns to rebel against what he calls “pure painting”—an active choice he made to visualize the complexity of al-Hallaj’s writing and theories (Marsoum Art Collective n.d.). In this way, he attempts to visually represent the secrets of another, higher world beyond this world of appearance. Using overlapping techniques in terms of rendering line, color, form, and collage, Dawod employs multiple levels of visual communication as well as the rhythmic repetition of verbal elements transformed into organic structures technically akin to Sufi dhikr. The artist refers to this articulation of the mystical moment, as “weav[ing] my carpet à la al-Hallaj”:

However, I endeavored not to make the images on my carpet similar to that of al-Hallaj. The images in this series are not an explanation or a visual rendering of al-Hallaj’s vision established in his book of The Tawasin, rather, they reflect some of the communications and ambiances of his book that resonates with me and I thus created a space for them in my works.(emphasis added; Dawod et al. 2013, p. 5)

Al-Hallaj rejected a structured format for his prose because he recognized the inability of the mind to convey fundamental truths. Instead, he advocated that the mind adopts an intuitive cognition that freely expands the scope for understanding and spiritual comprehension. Such intuitive understanding requires Sufi “taste” (dhawq), a product of spiritual meditation and remembrance. By training this spiritual sense, a form of religious aesthetics, Dawod refines his “taste”, allowing him to perceive spiritual truths in sensible forms (Dawod et al. 2013, p. 5).

After al-Hallaj began to proclaim what had been revealed to him, he is told to abandon the woolen cloak traditionally worn by the Sufis. He adopted a layman’s garb to mingle freely with all social classes and encouraged everyone to find God in their own hearts. Many contemporary mystics felt threatened by his antinomian emphasis on direct personal inspiration (ilham). With this rejection of worldly taboos and authoritarian commands, he broke the strict vow of secrecy that was binding on Sufis: he ceased to espouse esoteric (batin) notions of truth (reserved for the initiated) that were by definition inaccessible to the layperson. However, along with his refusal to protect true knowledge from “desecration”, he also refused to protect himself, the bearer of that knowledge.9 Brutally executed in Baghdad as a heretic, al-Hallaj’s writings and sayings were partially preserved by successive generations in spite of the official ban on the copying or sale of his works until the fall of the ‘Abbasids in 1258. This fact also bears witness to the extremes of emotion his teachings inspired.

“[T]here is no way of knowing what truth is, or how to describe it”, says Dawod. However, by assuming a form grasped by his sensory perception, the truth can be expressed in his work in terms of “the clear; the obscure, which requires interpretation; and the mystical, which is unintelligible” (Dawod et al. 2013, pp. 3–4). This, the artist says, is also because there is a divine trace or effect (athar) in everything:

If the Divine appears through a coded language spoken by the objects of this world, there must be traces left that bear witness to His presence, which makes us ponder the vastness of this world in awe, and flush with jubilation at the meaning of these traces and the uniqueness of the emotional values that we acquire from the pondering, which are aesthetic values in the wider sense of the word.(Dawod et al. 2013, p. 4)

For Dawod, “the aesthetics of a painting lie in the vagueness and recklessness of the content and the absence of a one-dimensional purpose” (Dawod 2011, p. 38). In doing so, he follows al-Hallaj’s core teaching of first finding God in the depths of himself and identifying it with his reductionist and minimalist methodology.

The creation of the Ta-Sins series is for Dawod an intuitive testimony of devotion, a ritual of transformation and transition (Figure 3). With each painting, he seeks to “open silent doors in the heart of darkness”. Dawod’s art creates his own reading of al-Hallaj’s The Tawasin, alluding to the abstract symbolism, line diagrams and cabbalistic symbols contained in that book, as well as more personal objects such as the mystic’s robe and animal skin. However, he also opens up the symbolic space to choreograph the Sufi notions of ego-annihilation and subsistence in God (fana’ wa baqa’), the persistent longing for inseparable divine union. This elimination of the dichotomy between subject and object during the final stages of the mystical path took place after the brutal dismemberment of the mystic’s body. Iraqi art critic Louai Hamza Abbas provides further insight into Dawod’s particular style of visually “reading” al-Hallaj’s text:

The body is imperfect and amputated, representing the overwhelming signs of eternal suffering, sustained by an ear that listens to the universe breathing, and a blinking eye that gently and acquiescently prolongs its gaze at the vast human inner spaces where horses without legs soar, trying to incarnate their unwilling and rebellious nature while being ridden by fond knights without hands inside the artist’s vision where they ‘[declare their] omnipresence in the form of gestures, or in the form of a mystic, cosmic language in which all creatures—man, animals and plants—speak and express themselves, while [solidifying] its gripping and captivating presence deep into the human inner self as a timeless language that has no beginning nor end. The beginning and the end undergo osmosis through nexuses, which no mind or sensuous perception can rule or decode’.(Dawod et al. 2013, p. 16)

Figure 3.

Amar Dawod, The Tawasin 10, 2016. Mixed media on paper. 171.5 × 169.5 × 6.5 cm. © Amar Dawod.

Dawod moreover sees al-Hallaj’s discourse as “a local Arab cultural project” that has what he calls “an innovative, civilized dimension” which is worth implementing, if understood from a viewpoint which “is free from intellectual and denominational intolerance and absolutism” (Dawod et al. 2013, p. 4). In Dawod’s work, embodied experience and the visual translation of al-Hallaj’s gruesome death and beginning of a new life, evoking the trauma of war in Iraq, are enacted together and flow through each other. In this context, he quotes al-Hallaj with the lines:

I saw my Lord with the eye of my heart.I said: ‘Who are You?’He said: ‘You!’But for You, ‘where’ cannot have a placeAnd there is no ‘where’ when it concerns You.The mind has no image of your existence in timeWhich would permit the mind to know where you are.You are the one who encompasses every ‘where’Up to the point of no-where.So where are you?(Dawod et al. 2013, p. 4)

The artist further explains that a visual recognition follows intuition, because “[t]he aesthetic expression is not what we create, though we are engaged in generating it” (Dawod 2010). He calls upon the viewer, “[m]y friend, let the imaginary birds set in on your wasteland; but do not classify them. In the beginning, there never is a classification; there is no particular point where the creative experience ends” (Dawod 2010).

Case Study 3Light, Cosmic Conception, and the Baobab of BlissI continued on my arduous path by seeking the representation of beauty through my artistic sensibility, a concept that connects ethics, aesthetics and religion.Maïmouna Guerresi (Malik 2017)

The internationally renowned multimedia artist Maïmouna Patrizia Guerresi uses various creative media, ranging from photography to sculpture, video and installation. All are interconnected in “a circular language, a dialogue between different techniques” (De Leonardis 2014). Patrizia Guerresi was born in Pove del Grappa in Vicenza, Italy, in 1951 into a religious Catholic-Italian family and converted to Islam at the age of 40. After joining the Muride Baye Fall Sufi movement,10 to which her Senegalese husband’s family also belongs, she was granted the Sufi name Maïmouna (“Blessed [by Allah]”). The influential movement, named after Ibra Fall (d. 1930), originated as part of the Muridiyya, a West African Sufi community founded in 1883 by the Senegalese Amadou Bamba Mbacké (d. 1927). Bamba’s vision of Islam was one that had at its core the precepts of nonviolence and social responsibility. The prominent Sufi leader and poet is credited with overcoming French colonial subjugation in Senegal through passive activism and pacifist struggle known as the greater (spiritual and moral) jihad (Babou 2007).

Since her spiritual transformation, Guerresi has approached the divine through this religious practice, the constant inner struggle (jihad) against the self (nafs), a spiritual evolution that, as she explains, allows access to the unseen through a sensuous and super-sensuous state. This is where the imagistic practice of Guerresi’s photographic work stops being just an aesthetic endeavor, and instead opens “a passageway seeking the representation of beauty through artistic sensibility, a concept that connects ethics, aesthetics and religion” (Malik 2017).

Guerresi sees her art as an aesthetic expression of her interiority, drawing “inspiration” from the lived reality of the Muride Baye Fall, a Sufi community that focuses on action and inner transformation rather than Muslim orthopraxy (daily prayers, fasting during the month of Ramadan). The artist sees these African Sufis “as guides for humans to navigate life”,11 emphasizing that: “Though you may be scared, you must follow them, and you must stay open to the beauty that they provide” (Krifa et al. 2015).

“For me, starting new work is like repeating a ritual, a prayer or dhikr”, Guerresi explains, in which “the spiritual thought prevails over materiality” (Art Africa 2017). During the collective ritual, which is performed in prayer and recitation circles or associations, Baye Fall disciples rotate in a circle one after another. They move close to each other to feel like one body, swaying back and forth to the rhythm of the litanies so as to approach the divine. They place their hands on their ears to enhance the resonance of the chanting that glorifies God, the Prophet, and the marabouts (Wolof; “spiritual guides”) who guide their disciples in their quest for spiritual enlightenment, likened to a path through life that cannot be taken alone. During these moments of intense communion some participants fall into a spiritual state or trance (hal), accompanied by swooning, crying, convulsions, or even violent physical outbursts. The Baye Fall interpret these states as uncontrollable excesses of light (Krifa et al. 2015).

The symbolism of the circle appears in the video entitled Da’irat (from the Arabic da’ira, “circle”; 2003, DVD for projection, 10 min, video still) (Prearo 2006, pp. 134–35).12 It shows a veiled woman performing body movements in a circle. Guerresi explains the meaning of the circle in Sufi ritual with words attributed to Ibn al-‘Arabi: “Each thing and each being is a circle, because it returns to its Origins” (Prearo 2006, pp. 176–77).

The vertical white lines marking the face, feet and palms of the hands of the protagonist in Da’irat are just such “symbols of light and purification”. Guerresi describes these as “like a white bisection marking the confines or borders between life and death, the known and the unknown” (Ori Journal 2012). The color white also refers to milk, a drink the Prophet Muhammad selected in a visionary experience from among several beverages, which, as Oludamini Ogunnaike explains, “he understood to be the sensible form of the supra-sensible reality of knowledge” (Ogunnaike 2017),13 an action reflecting his natural disposition (al-fitra) to embark on the correct path. In Africa, moreover, milk is used as a purificatory and sacrificial substance.

Another photograph shows a female figure whose face is also marked by a bright white stripe that extends from the forehead to the nose and chin (Figure 4). She is dressed in a flowing white cloak (hijab) covering everything except the face and hands which has a large circular cavity—like a deep black hole—at the center, evoking a “doorway or threshold” (Milbourne 2018, p. 181). Bubbles of light again highlight the pivotal role of light, an aesthetics of light. These bubbles emerge from the mystical black hole as if to give birth to “many new worlds”. These mystical symbols, Guerresi says, denote that “the body is no longer a prison of the soul but rather like a temple to house and glorify the Divine” (Milbourne 2018, p. 181). At the same time, the colors white and black allude to the clothing of the Bay Fall Sufis and to their “spiritual greatness” (Guerresi 2022). Guerresi explains that this work

emphasize[s] particularly the feminine-divine, the great mother, clement and merciful, as God is like a welcoming womb. In fact, the key word of the Basmala—Bismillah al-Rahman al-Rahim, which means ‘In the Name of God, the Clement and Merciful’—denotes the feminine. From the root rahima comes rahim which means merciful from which derives the word for uterus, rahm. ‘Genitilla–al-Wilada’ is a character who has two names: Genitilla after an ancient pagan festival, and the other al-Wilada meaning the pregnant woman in Arabic.(Behiery 2012; cf. Behiery 2017)

Figure 4.

Maïmouna Guerresi, Genitilla–al-Wilada, 2007. Lambda print on aluminum. 200 × 125 cm. © Maïmouna Guerresi, courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery.

With this, “Genitilla–al-Wilada” “embodies a kind of matrix impregnated by the creation of the universe” (Krifa et al. 2015, p. 12).

By moving in the realm of sense and affect, and by communicating her personal feelings, Guerresi’s artwork makes the distant, the unknown, more accessible to a Western viewer. The large photo installation “Cosmo” consists of circles in various sizes that rotate planet-like in their orbits (Figure 5). At the center is a white figure with a red headdress who, seen from above, spins counterclockwise, symbolizing the mystical dance of the Sufis, which Guerresi describes as follows:

A metaphorical representation of the many worlds and constellations where inner beauty and aesthetic appearance are joined together as the symbolic representation of infinity, in a mystical union with the divine universe expanding and contracting like a breath. This circular motion is like a never ending spiral that leads to the dissolution of the self into divine beauty as well as like the mystical knowledge that floods the heart of every seeker, leading to the search for ‘interior illumination’.(Islamic Arts Magazine 2015)

Figure 5.

Maïmouna Guerresi, Illumination 1, 2010. Lambda print on aluminum. 120 × 120 cm. © Maïmouna Guerresi, courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery.

The body of the revolving dervish serves as a nucleus, a conduit of cosmic forces in a cosmological system. Like the video Dikhr (2007, DVD for projection, 5:34 min, video still), this photograph conveys the emotion and devotion of the participants in the ritual. Dikhr shows a group of veiled Kenyan women, their faces, hands and feet again marked in white. They breathe their prayer in tandem with the wind, their outstretched palms facing up (the motion one makes to accept a prayer), rotating slowly as the wind ruffles their long robes (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Maïmouna Guerresi, Dikhr, 2007. Video. 5:34 min. © Maïmouna Guerresi, courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery.

Yet another photograph, entitled Mandala (Figure 7), alludes to a Sufi saying stating that: “We Sufi are like compasses, we have a foot in Islam and with the other we circulate around all religions” (Prearo 2006, p. 108). The tall pointed hats are “like high antennas enabling connection with the sky”. For Guerresi, their red color “recalls the color of blood, life and sacrifice” (Prearo 2006, pp. 109–10).

Figure 7.

Maïmouna Guerresi, Mandala, 2006. Lambda print. 125 × 125 cm. © Maïmouna Guerresi, courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery.

Guerresi also emphasizes “the emotions” she feels when visiting sacred places (Bower 2018, p. 31). The holy city of Touba, her spiritual home, plays a particularly important role in her artwork (Aesthetica Magazine 2022). According to tradition, whilst sitting in the shade of a large tree, Ahmadu Bamba had a mystical vision in a moment of ecstasy (hal). This event inspired the great shaykh to found a city in 1887 which he named Touba, later becoming the second largest city in Senegal. The city became “a symbol of Muridism”. A sacred place of Senegalese spirituality, it also houses Ahmadu Bamba’s tomb and that of Ibra Fall (Guerresi, email to author, 27 November 2022; Ross 1995). The shaykh named the city Touba (from the Arabic tuba, or “bliss”) after the tree of paradise mentioned in the Qur’an (13:29).

Guerresi is deeply inspired by the story of the sacred Tuba tree—in Senegal symbolized by the Baobab—which is believed to have “the power to heal everything around it” (Aesthetica Magazine 2022). “To me trees represent a metaphysical bridge between heaven and earth”, she says (Kahl 2021). In Sufi thought, the Tuba is the “world tree”, a “tree of light”, rooted in the divine and illuminating the world below. Its roots are in the soil of the earth and its fruits in paradise. Standing at the center of paradise, it embodies centrality and axiality, which in turn represent the pursuit of spiritual perfection (Ross 2011).

Under one such sacred tree called “Guy Texe” (Wolof; “Baobab of Bliss”), which stood at the very center of Touba’s cemetery, is the tomb of Soxna Aminata Lo, the first wife of Ahmadu Bamba. According to popular belief this baobab represents the paradisiacal Tuba on earth, and the faithful wished to be buried near it to attain eternal bliss in its shade. The baobab collapsed in 2003 and only its roots remained (Ross 2012).

The tree also represents a materialization of the immaterial—a kind of corporeal extension, or even an actual embodiment, of Soxna Aminata Lo’s spiritual power. Her “presence in absence” points to its liminal status as a medium of communication and control between human beings and other realms (Korom 2012, pp. 1–19). As such it is frequently regarded as proof of the living presence of this female saint, of her revivifying and life-giving powers. Pilgrims reverently visit the site to pay their respects to the tree roots and to offer petitionary prayers before it.

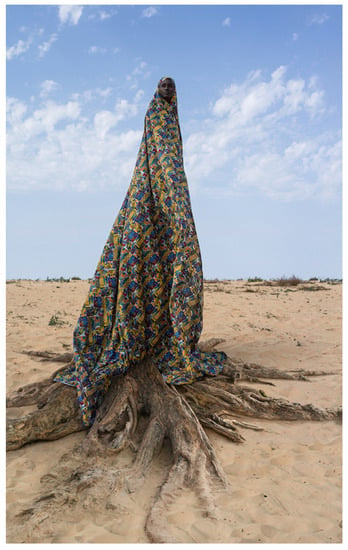

Guerresi’s photographic series Beyond the Border—A Journey to Touba (2020–2021) is an aesthetic contemplation of this sacred tree. It is worth noting that “Touba” is also a girl’s name in Senegal (Aesthetica Magazine 2022). The photograph, titled Yaye Fall, depicts a very tall woman merging sculpture-like with the roots of a baobab tree (Figure 8). In this photographic work Guerresi “connects the feminine spiritual strength to the symbolism of the Touba tree” (Guerresi, email to author, 27 November 2022). There is a powerful conflation of categories in which the complementary potentialities of tree and woman merge together to form one embodied unity.

Figure 8.

Maïmouna Guerresi, Yaye Fall [Yayfall], 2009. Lambda print on aluminum. 200 × 125 cm. © Maïmouna Guerresi, courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery.

Most of Guerresi’s work revolves around the interconnection and interdependence between humans and nature (Guerresi 2022). In her early work, the artist speaks of “a performative process of mimesis” in which her “body becomes a tree”. Under the patched garment of the Yayfall “strong roots emerge that penetrate the sand”, with “her strong cultural and spiritual roots underlining her relationship with her land” (Guerresi, email to author, 27 November 2022). In her words, “Every human being is connected to everything that exists on earth. It follows that the fate of our planet is affected by the actions of individuals. The relationship between humanity and nature reflects the relationship to oneself, to one’s own interiority. Thus, the desertification of the natural environment corresponds to the spiritual devastation of man’s inner life”. She also notes that trees have always been a kind of intermediary between heaven and earth (Aesthetica Magazine 2022).

The tall female disciple of the Baye Fall community, who emerges from the tree roots, is wrapped in a flowing multicolored patchwork-style cloak (Wolof niahaas). This was handstitched from small leftover pieces by the artist herself in the ritual manner of the Muride Baye Fall community (Guerresi, email to author, 27 November 2022). An aesthetic vision transformed into a sculptural garment inspired by the humble lifestyle of Ibra Fall, it is sewn together from ninety-nine pieces of fabric (for the ninety-nine names of Allah) because, as Guerresi remarks, women bear Allah’s most beautiful names (Malik 2017).

Shrouded by the sacred garment, the body of the Yayfall becomes “the temple of the soul”, a sacred dwelling in continuous becoming. With this, Guerresi also reaffirms

a universally recognizable feminine energy that translates into spiritual evolution. I try to decontextualize and decolonize the various stereotypical ideas of women in the Islamic world … who have contributed to the social and spiritual evolution of their country, but who history has unfortunately forgotten.(Guerresi 2019)

Guerresi thus acknowledges the vital element of female spirituality and the contribution of women to the social and spiritual development of their country and beyond.

The spirit, soul or breath of life (ruh) is also visualized by slender meandering wooden branches growing out of the mouth of a seated female figure, reflected in a diptych narrative on view in Guerresi’s current exhibition Rûh/Soul (Guerresi 2022). The allegorical image can allude to the inner spirit that comes into play when the Baye Fall Sufis offer bundles of wood to their marabout to demonstrate their work and submission on the occasion of the Grand Magal of Touba, the annual pilgrimage of Touba (Guerresi, email to author, 25 November 2022).

Case Study 4The Sufi RapperIl travaille pour ce monde comme s’il aller vivre toujourset pour l’autre comme s’il aller mourir demain.Il corrige les défauts enfouis aux tréfonds de lui-même,et se détourne du voile des mystères.Il chemine sur cette voie qu’il discrimine, qui déterminecelle qui était déjà là avant même qu’il ne se détermine.

The French rapper, composer, author and director Régis Fayette-Mikano (b. 1975 in Paris) came from Catholic-Congolese roots but converted to Islam at the age of sixteen, from then on calling himself Abd Al Malik (“Servant of God”). In the early 1990s, he started rapping to bring attention to the situation in the French banlieues where he had grown up, and went on to form the rap group New African Poets (NAP). His songs denounce injustice and recount traumatic memories of loss, oppression and isolation in these low-income housing estates, the world of ghettoized immigrants, “one of destitution and ostracism”, through which he defines himself as a “breaker of ghettos” (Ruquier et al. 2008). Before turning to Sufism (Abd Al Malik 2009, pp. 120–26), he joined the Tablighi Jamaat, an ultraorthodox transnational Islamic Deobandi missionary movement. Since music in general and rap in particular, a form of oral storytelling, was frowned upon by this movement, he eventually turned his back on the Tablighi Jamaat after he was asked to stop making music under his own name (Abd Al Malik 2009, pp. 57–119).

The rapper then discovered a different Islam: Sufism. His first exposure was through reading the classical works of Sufis such as Ibn al-‘Arabi and Emir Abdelkader (1808–1883), an Algerian Sufi and military leader who led the struggle against the French colonial invasion of Algiers in the early 19th century fighting for what would now be called human rights, and later the writings of contemporary Sufi scholars such as Faouzi Skali (b. 1953) and Éric Geoffroy (b. 1956) (Skali 2010; Geoffroy 2010). In 1999, Abd Al Malik met the Moroccan shaykh Sidi Hamza al Qadiri al Budshishi (1922–2017), head of the Qadiri-Budshishiyya Sufi Order, who became his spiritual guide and mentor: “Sidi Hamza’s gaze met mine: in a fraction of a second, I was transported by this vision of an ocean of love” (Abd Al Malik 2004a, p. 171).

After joining the Qadiri-Budshishiyya, Abd Al Malik learned about love and acceptance of the other from his spiritual teacher. Sidi Hamza lived near Madagh in the north of Morocco, so one of the songs the rapper dedicated to him and to the teachings of the Sufi order is called “Raconte-moi Madagh” (“Tell me about Madagh”), in which he presents himself as a pirate unearthing the spiritual treasure that lies buried in this Sufi tradition (Abd Al Malik 2008b). In it, he also talks about his love and fear in the face of these spiritual teachings. To obviate such reactions, Sidi Hamza had initiated a renewal process of Sufi spirituality epitomized by the transition from the majestic (jalal) aspect to the beautiful (jamal) aspect of spiritual orientation: “We are living in times of hardship [that is jalal in this context] so there is no need for more, we are living in age of hatred and love is needed to balance us to gain any human sanity” (Ali n.d.). Sidi Hamza explains this hardship as “social crisis that characterizes our societies today, which includes family breakdown, drugs, social distrust, hate, hypocrisy, stress and other diseases” (Ali n.d.).

From 2004 onwards, Abd Al Malik began exploring Sufism through the medium of his rap, as seen in the English translation of his autobiographical narrative Sufi Rapper: The Spiritual Journey of Abd al Malik (original French title: Qu’Allah bénisse la France).15 Sufi aesthetics had a corresponding influence on his lyrics. In the same year, he expressed his spiritual journey by releasing his debut solo album Le face à face des cœurs (The Face to Face of Hearts), a title borrowed from the 2010 work of the charismatic Budshishi Sufi Faouzi Skali, in which he advocates respect for the plurality of thought and the diversity of paths according to the aspirations of each individual. It contains the song “Ode à l’Amour” (“Ode to Love”), which paraphrases a famous poem by Ibn al-‘Arabi from his Tarjuman al-Ashwaq (Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi Society n.d.). It begins as follows:

Il y eût temps où je faisais reproche à mon prochainSi sa vie n’était pas proche de la mienneMais à présent mon cœur accueille toute formeIl est une prairie pour les gazellesUn cloître pour les moinesUn temple pour les idolesUne Kaaba pour le pèlerinLes tables de la Thora et le livre du CoranJe professe la religion de l’amour et quelle que soitLa direction que prend sa montureCette religion est ma religion et ma foi.(Abd Al Malik 2004a, pp. 202–4; 2004b)

There was a time when I reproached my neighborIf his life was not close to mineBut now my heart welcomes all formsIt is a meadow for gazellesA cloister for monksA temple for idolsA Kaaba for the pilgrimThe tables of the Torah and the book of the KoranI profess the religion of love, and no matterThe direction his mount takesThis is my religion and my faith.

Abd Al Malik’s commitment to cultivating diversity and plurality (religious, gender, ethnic, etc.) is woven into the fabric of the verses.

Two years later, in 2006, the artist released his second solo album Gibraltar, which won numerous awards.16 Gibraltar has an unusual aesthetic. While working on the album, Abd Al Malik deconstructed the very notion of rap as he developed a unique new sound that fuses elements of Sufi qasida poetry, West African Muslim griot musical storytelling (Grey 2013), chanson and jazz with slam and rap/hip-hop. The lyrics of the title song produced a “soundscape” that activates a unique sensory experience:

Faut rien dire et tout est dit, et soudain … soudain il s’fait derviche tourneur,Il danse sur le bar, il danse, il n’a plus peur, enfin il hurle comme un fakir, de la vie devient disciple.Sur le détroit de Gibraltar y’a un jeune noir qui prend vie, qui chante, dit enfin je t’aime à cette vie.…Sur le détroit de Gibraltar, y’a un jeune noir qui n’est plus esclave, qui crie comme les braves, même la mort n’est plus entrave.…Maintenant il pleure de joie, souffle et se rassoit.Désormais l’Amour seul, sur lui a des droits.…Du détroit de Gibraltar, un jeune noir vogue, vogue vers le Maroc tout proche.(Abd Al Malik 2010)

You don’t have to say anything and everything is said, and suddenly … suddenly he becomes a whirling dervish,He dances on the bar, he dances, he’s not afraid anymore, finally he screams like a fakir, from life becomes a disciple.On the Straits of Gibraltar there is a young black man who comes to life, who sings, finally says “I love you” to this life.…On the Straits of Gibraltar, there is a young black man who is no longer a slave, who shouts like the brave, even death is no longer a hindrance.…Now he weeps with joy, breathes and sits down again.Now Love alone has rights over him.…From the Straits of Gibraltar, a young black man sails, sails to nearby Morocco.

Inspired by the tradition of Qadiri-Budshishi Sufis who sing qasa’id, or spiritual poetries, which is usually followed by a Sufi dhikr, Abd Al Malik creatively adapted the Arab-Islamic tradition of Sufi qasida poetry within the context of French rap (Brigaglia 2019, pp. 93–116). The structure of these songs follows the tripartite cycle of classical qasida poetry, as defined by Andrea Brigaglia in reference to the theoretical work of Stefan Sperl and Christopher Shackle on this poetic genre (Sperl and Shackle 1996). The music expresses a shift in the poet’s consciousness that combines elements of spiritual development, creative inspiration, performance and audience participation.

The songs on Gibraltar revolve around the theme of spiritual transformation. They begin with a prelude introducing the main themes of the poem, often by means of metaphorical language. There is reference to Abd Al Malik meeting his shaykh Sidi Hamza who introduces him to the core Sufi teachings of the order, the jamal aspects of love and compassion. In the middle section, a catharsis occurs after the rapper embraces these teachings: “Now Love alone has rights over him”. The final verses take up again the images introduced at the beginning of the poem. They are placed in a new, contrasting context that expresses the final stage of the transformation achieved when a “young black man sails, sails to nearby Morocco”, the abode of his spiritual teacher. The application of this cycle to Abd Al Malik’s autobiographical and musical context reflects his innovative engagement with the aesthetic tradition of the Sufi qasida. The well-trained Sufi discerns the batini or inner symbolic sense of the qasida that goes beyond the literal meaning of words, called zahiri, or mundane meanings. This potential for cultivating interior (batin) dispositions is actively harnessed within Abd Al Malik’s lyrics.

Sufi qasa’id also foreground acts of attentive listening. For Sufis of the Qadiri-Budshishiyya and many other Sufi orders, spiritual practice involves listening, sama‘, whether it be spiritual qasa’id, or a sublimation of tarab, a poetic and musical emotion or exaltation. These acts of listening are performative, inducing vibrations and rhythms within the body, which are, in turn, transformative (Kapchan 2015, pp. 33–44; 2016). Through the transformative experience, listeners seeking to attain a higher sense of Islamic piety learn to dissolve their egos (nafs).

Characterized by rhythmic diction, repetitive rhymes and simple meters, both the qasida tradition and griot music in Abd Al Malik’s rap help to pass on knowledge. Poetry slam, as a spoken-word art form in the tradition of West African Muslim griot musical storytelling—also engages with an ethics of social justice. The use of these elements underscores Abd Al Malik’s social engagement against racism and neo-colonialism, a point I will address below.

Another song from the album Gibraltar, “L’Alchimiste”, describes the role Abd Al Malik attributes to his Sufi shaykh Sidi Hamza. He sees him as an alchemist who transformed his heart from a state of baseness into nobility:

Je n’étais rien, ou bien quelqu echose qui s’en rapproche,J’étais vain et c’est bien c’que contenait mes poches.J’avais la haine, un mélange de peur, d’ignorance et de gêne.Je pleuvais de peine, de l’inconsistance de ne pas être moi-même.J’étais mort et tu m’as rammené à la vie:Je disais ‘j’ai, ou je n’ai pas’; tu m’a appris à dire ‘je suis’.Tu m’as dit: ‘le noir, l’arabe, le blanc ou le juif sont à l’homme ce que les fleurs sont à l’eau’.Oh, toi que j’aime et toi, que j’aime.(Abd Al Malik 2006; 2013, pp. 211–13)

I was nothing, or something close to it,I was vain and that’s what was in my pockets.I had hatred, a mixture of fear, ignorance and embarrassment.I was raining with sorrow, with the inconsistency of not being myself.I was dead and you brought me back to life:I said ‘I have, or I have not’; you taught me to say ‘I am’.You said to me, ‘Blacks, Arabs, Whites, Jews are to man what flowers are to water’.Oh, you whom I love and you whom I love.

The term “alchemy” is used by the Qadiri-Budshishiyya and other Sufi groups to express spiritual growth and expansion. In the process of training their nafs, often by disciplining the body through the recitation of dhikr and listening practices, followers learn how to overcome, for example, the trauma of racial prejudice (“race” figuring quite prominently in Abd Al Malik’s rap lyrics as, for instance, in “L’Alchimiste”), the aim being to transform hearts. This inner transformation—initiated by the spiritual teacher or shaykh, the alchemist—is achieved through physical discipline, the corporeal transmission of knowledge, and so the embodiment of knowledge (or “alchemizing bodies”; Carter 2021, p. 64). Abd Al Malik epitomized this spiritual method in a 2016 interview: “Knowledge of Sufism does not abide in texts” but is a gateway to “something that is tasted from within” (Zéro 2016).

In Le Dernier Français (The Last Frenchman), a 2012 collection of poems/rap lyrics on the harsh conditions of the banlieue, Abd Al Malik expounds on the diversity of religions that stem from the diversity of cultures and the diversity of worldviews, the manifold human responses to God’s proposition: “This divine proposal arises within the human conscience”, the rapper says, “It is there, in this intimate sanctuary, that God speaks to each person and invites him/her to love him. This invitation is addressed to all human beings” (Abd Al Malik 2013, p. 21). The lyrics also precipitate new aesthetic practices in a multi-faith public: “Blacks, Arabs, Whites, Jews are to man what flowers are to water”. This quote alludes to the fundamental Sufi principle repeated both in Qu’Allah bénisse la France and in Le Dernier Français, that there is but “the one human race”. It presents, as David Spieser succinctly notes, a special insight, namely: “That there is a Principle bigger than man in the same way that water is bigger than the flowers; water is essential to flowers, and unites them in that they all take their beings from the same source of Being, and yet every flower is different from the others in terms of smells and colors” (Spieser 2015, p. 217).

Spieser makes an interesting observation in relating Abd Al Malik’s aesthetic conceptualization of “equality” to the philosophical reflections of the French philosopher Jacques Rancière (b. 1940) (Rancière 2006; see Spieser 2015, p. 7). Rancière notes that before the French Revolution, literature as a whole could only treat subjects that were considered “noble”, whereas after this turning point, in the new emerging “regime”, any subject—noble or otherwise—could be portrayed. Since “aesthetic politics” are made up of different “regimes” that determine what is “visible”, “seen”, and “audible”, “art forms” can never be divorced from “political forms” (Spieser 2015, pp. 11–12).

In some of his lyrics, Abd Al Malik uses language as a marker for alterity. Rejecting standardized French, he uses the “banlieue” dialect (“banlieue-speak”, mostly of North African origin, and deprecated by official French language policy) and Alsatian jargon, verlanization (word inversions) as well as integrating Sufi idioms. The poems in Le Dernier Français describe the harsh milieu of the banlieue in which people are “disintegrated” instead of “integrated”: “C’est la galère”, “it is hellish”. For Abd Al Malik “we are all on the same boat/hard-ship” whereas “[…] the city around was an ocean // and we rowed alone” (Spieser 2015, pp. 11–12). The imagery evolves into desperate people actually drowning, all fighting individually in a struggle against death and “[…] respecting each other only when one of them dies” (Spieser 2015, pp. 11–12). Elsewhere in a 2008 interview, Abd Al Malik expressed his solidarity with the plight of migrants, in the figurative sense with “boat people” by stating: “I am in solidarity with all those who suffer! Without exception. Separating families, organizing ‘raids’ in front of schools, is unacceptable” (Jeune Afrique 2008). By emphasizing linguistic diversity, Abd Al Malik’s immigrant-inclusive aesthetic encourages the cultivation of certain emotions, modes of religio-cultural expression, as well as certain ethical values that embrace alterity and plurality.

Case Study 5The Hoopoe BirdIn testing the veracity of art’s spiritual roots as well as the limits of abstraction,I seek knowledge in the space between abstraction and figuration.Hanaa Malallah (Faruqi 2011, p. 68)

Iraqi-British mixed-media artist Hanaa Malallah (b. 1958 in the Thi Qar province), one of Iraq’s leading contemporary artists, began practicing art while growing up in an environment of conflict, sanctions, war and occupation in Baghdad. Despite the violence, lawlessness and travel restrictions in the wake of the Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988), the Gulf War (1990–1991), and the U.S. invasion and occupation (2003–2011), Malallah remained in Iraq, where she explored themes of survival and resistance in her art. However, in 2006, after receiving death threats from militias who, following the U.S. invasion, launched a campaign of violence against intellectuals and artists, Malallah reluctantly left Iraq. After emigrating, her focus shifted to the relationship between spirituality and art.

Malallah was a favorite student of Shakir Hassan Al Said (1925–2004), one of Iraq’s most influential artists, who combined medieval Sufi traditions with contemporary abstract art. He introduced her to the mysteries of Farid al-Din ‘Attar’s The Conference of the Birds (Mantiq al-Tayr, 1177), the famous epic poem which serves as a metaphor for the Sufi quest of enlightenment. Her appreciation of ‘Attar’s allegorical tale deepened during long conversations with Al Said and in the letters they exchanged while Al Said lived in Amman (Malallah 2021). When Malallah emigrated from Iraq, ‘Attar’s The Conference of the Birds was one of the two books she took with her (Malallah 2022).17

The artist takes inspiration from the knowledgeable hoopoe (hudhud, a metaphor for the Sufi master), which figures as an aesthetic and visual motif in her work. As the spiritual guide on the dangerous mystical quest, the hoopoe guides the birds in search for the Simurgh, the legendary king of birds who lives somewhere at the edge of the world. The artist sees in “the iconic leader of ‘Attar’s avian seekers…a simulation of reality, which in itself is a simulation of perfection”. Only “thirty birds” or si-murgh reach the abode of the Simurgh at the end of the arduous spiritual journey, the others having fallen victim to their own vice and perished along the way. These thirty birds recognize themselves as reflections of their own self, as mirror images of the si-murgh (si, “thirty”, and murgh, “bird” [Simurgh], a highly ingenious pun in Persian mystical literature). They discover that the goal of their quest, the divine Simurgh, is nothing but themselves. With this they at last transcend and merge (fana’) into the Simurgh (or divine unity), affirming the Sufi view of the God within.

“Many of my works”, Malallah says, “assimilate the idea of the hidden and the process of emergence based on awe of the unknown and the notion of transformation in the promise of the Secret” (Malallah 2010). Malallah equates the hoopoe’s guidance of this journey with her own artistic journey, in which she embarks on a quest for truth in order to survive (Macmillan 2014), a theme that was also central to her teacher Al Said. In her work, the hoopoe has become a symbol of survival itself, of which she says: “Hoopoe, the sheikh or pir who leads the 30 in ‘Attar, is the quintessential survivor. I am He” (emphasis added; Macmillan 2014).

During the 1970s, Al Said created experimental art by damaging and burning material, a technique which Malallah came to conceptualize as “ruins technique” in 2008 (Malallah 2022). These processes are reminiscent of conventions of Nouveau Réalisme (Carrick 2010) as a particular art historical mode of re/presentation and aestheticization: destroyed surfaces are combined with burnt, torn, tattered and shattered material that is reassembled, painted over, glued, layered and arranged in grids; its aesthetic characterized by pastiche, self-referentiality, fragmentation, hybridization and multiplicity. Malallah has described this technique as “writing by knife, painting by fire”, a practice which provokes not only an aesthetic, but also a somatic reaction in the viewer.

Malallah’s “ruins technique” reflects the lived experience of war, a powerful theme which figures prominently in her work. The images imprint themselves upon the viewer, crying out to be read in context. By using techniques that contaminate and damage the materials she works with, she gives them the appearance of ruins, rubble, the devastation of war. By creating chaos and destruction in which “anything solid can be reduced to nothing within seconds” (Malallah 2022), she aims to “engender the visceral experience of the reality of war irrespective of its geographic/political particular[s]” (Malallah 2010). Malallah further explains that:

The physicality of war is a completely different experience. It ruins the essence of all being. Death has no meaning and everything can be reduced to nothing in a few seconds. To witness the process of extinction, the metamorphosis of material to dust, led me to conclude that the phenomenon of destruction is hidden in de facto representation. I explored the space that exists between figuration and abstraction, between life and death, a concept for me which holds a deep spiritual meaning.(Malallah 2022)

The artist alludes here to the Sufi metaphysical concept of barzakh or “intermediary state” (Bashier 2004; Morris 1995, pp. 42–49, 104–9), which denotes the realm located between the world of matter and spirit, the unseen in-between. The basic notion of a barzakh refers to the mysterious eschatological realm of imagination that lies between the two realms of purely physical and purely intelligible/noetic being. Spiritual imagination allows us to make the invisible world visible.

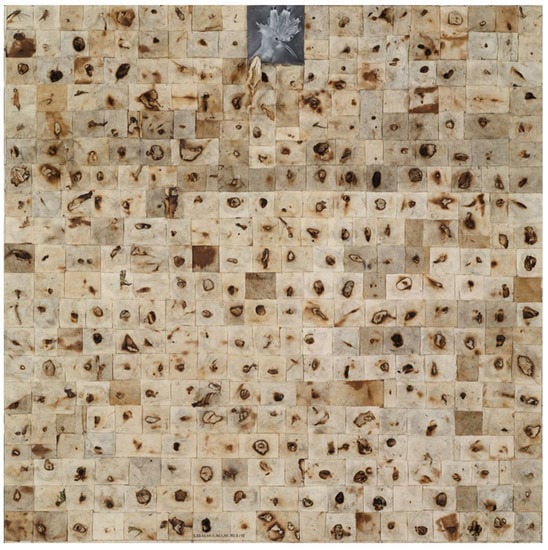

This notion is potently expressed in her work Portrait (HOOPOE) (2010), consisting of a neatly arranged square patchwork of canvas with burnt edges, scorch marks and mixed-media, reminiscent of the remains of a shroud (Figure 9). A small oil painting of a hoopoe crowns the top center of the composition. The hoopoe, referred to in the Qur’an (27:20) as a bird in the service of the Prophet Solomon, a messenger from the non-material world, becomes a kind of “meta-sign” which, in Malallah’s artwork, commemorates and laments the looting and the burning of the libraries and the museum in Baghdad that took place shortly after U.S. forces occupied the city in 2003 (Porter 2008, pp. 132–33). Malallah further explains that, “by way of shifting the cut and scorched page, I have facilitated the possibility of multiple interpretation of a single surface, stored in my memory through repeated readings of the book by ‘Attar. With this I am also able to recall scenes of ravaged manuscripts in Baghdad which took place during the war on Iraq and the subsequent occupation”. The figure of the hoopoe also serves as a reference to the “bird talks” of the Sufi mystics, an allegory for the search for God, the search for a place to survive and to call a home.

Figure 9.

Hanaa Malallah, Portrait (HOOPOE), 2010. Folded burnt canvas, mixed media and oil color on canvas. 100 × 100 cm. © Hanaa Malallah.

The hoopoe has often been described as a leader or a king of birds due to its crown-like crest, described by ‘Attar as “the crown of truth and the knowledge of both good and evil” (‘Attar 1971, p. 11; cf. ‘Attar 1984, lines 693–716). Malallah also uses the taxidermied remains of the hoopoe, mounting the dead animal for exhibition in a lifelike state, and provides the brutal but compelling explanation that “the shape is there but the content (life) is not” (Malallah 2014). A stuffed hoopoe also sits on the back of a broken and burnt chair, a modified found object (Figure 10). It is significant that the carcass had to be dissected and dismembered in order to mount the plumage. The artist describes this process of preparing, stuffing and mounting as an “abstraction rooted deeply in the reality of war and violence”. Just as she sees herself as a hoopoe, the survivalist par excellence, Malallah also uses the hoopoe in her works as a “symbol of suffering and survival” (Malallah 2014). It is worth noting that she also used this symbol in a modified form in a secular context.

Figure 10.

Hanaa Malallah, Chair, 2011. Mixed media with hoopoe bird. © Hanaa Malallah.

Inspired by the biblical symbol of the dove, which Pablo Picasso transformed into the iconic symbol of peace bearing an olive branch (La Colombe de la Paix, 1949), she has replaced the dove with the hoopoe and depicts the hoopoe with an olive branch as a metaphor for the struggle for survival (see the “Survival Hoopoe”. Digital Print. 40 × 31 cm; Caravan 2014).

In another work created in 2015, a red and black ink drawing entitled “I Have Learnt Something You Did Not Know”, the bird stands for protest against foreign military occupiers in Iraq (Figure 11). Surrounded by smudges and splattered traces of red ink, the hoopoe is portrayed at the center of the painting. The bird is sketched in precise ornithological detail, in keeping with a Sufi distinction which emphasizes presenting things as they really are, rather than as they might be or would be in a possible world (cf. Leaman 2004, pp. 167–68). By thus concentrating on the figure of the hoopoe, both the artist’s and the observer’s identity can be absorbed into the object of spiritual contemplation. The more one focuses on the bird, the more deeply one is immersed in it. The “I” is transformed, if only temporarily, into “it”. In some places, the ink forms the shape of red roses. In stark contrast to the principle of representing things precisely and in detail, these flowers are smeared and blurred on the artwork. They appear next to splattered traces of red ink. Like bloodstains, they weigh down the page, the realm from which the bird is trying to escape. In this context, the poetic title of the work is not only a statement, but almost a warning and an indication of the unspoken horrors of the conflicts that live on in the heart and memory of a survivor. At the same time, it recalls the Sufi notion of the desperate and violent attempts to escape the confines of the cage (the body) and the material thoughts that must be relinquished.

Case Study 6The Wisdom Book18O happy wilderness,Far will we roam!Far from the world’s torment,Far will we roam!Noor Inayat Khan (2018, p. 65)

Figure 11.

Hanaa Malallah, I Have Learnt Something You Did Not Know, 2015. Black and red ink on paper. 60 × 100 cm. © Hanaa Malallah.

During the 2020 global lockdowns, Greek director, playwright and visual artist Elli Papakonstantinou (b. 1973) co-produced, developed, designed and directed the digital cinematic opera Aède of the Ocean and Land: A Play in Seven Acts, written by Noor-un-Nisa Inayat Khan (1914–executed 1944). Lockdowns prompted Papakonstantinou, known by the Sufi name “Anwari”, a “fellow traveler in the [Inayati Sufi] caravan” (Inayat-Khan 2021), to explore the new aesthetic genre of “digital theater”.

The innovative production was based on the recently discovered play by Noor-un-Nisa, affectionately referred to as Noor by her followers, the first woman to be included in the canonical Inayati lineage (silsila). Renowned for her exploits as a clandestine radio operator and secret agent working with the Allies in occupied France during World War II, Noor was the eldest child of Indian master musician and Sufi teacher Hazrat Inayat Khan (1882–1927) and his American wife Amina Begum (née Ora Ray Baker; 1892–1949). One of the chief figures of modern Sufism, Inayat Khan developed Indian Chishti Sufi teachings globally and founded one of the largest Sufi communities in the West, now known as Inayatiyya. An innovational aspect of his Sufi mission was that he did not require his followers to formally convert to Islam (Kuehn 2019, p. 55).

Noor’s piece is a literary blend of East and West that subverts and reinterprets the spiritual journey as described in Homer’s ancient epic the Odyssey (8th or 7th century BC; Homer 2018) and Farid al-Din ‘Attar’s Conference of the Birds (Mantiq al-Tayr), its central themes revolve around mystical quest, love (personal, transcendental and spiritual), renunciation, and sacrifice. The play contains autobiographical references, as Aède’s three main characters are represented by Noor’s parents and herself to create a profound allegory of wandering and homecoming. In doing so, she has, in the words of her biographer Shrabani Basu, woven “a narrative that is at once an ode to her parents as well as her own interpretation of the journey of life” (Noor Inayat Khan 2018).

The live musical drama was performed only once, on 14 September 2020. The interactive live digital performance was conceived by Papakonstantinou, the Athens-based artistic director of the ODC ensemble, to explore a new genre of experimental “theater of seclusion for immaterial stages”. This experimental theater was used as an alternative “stage” with an international cast of twenty-two multidisciplinary performers (from five countries and ten time zones)19 to create, Papakonstantinou explains, exchanges leading to the generation of a new aesthetic.

With this live-streamed performance, Papakonstantinou wanted to produce what she refers to as “an audiovisual embroidery of the new age”, a new format that would support the vibrant and ephemeral nature of theatrical art (Papakonstantinou 2020a). It took place in “the different homes of the artists, who joined together to create a “unique audiovisual experience, a cinematic concert in synchronicity”. In Papakonstantinou’s aesthetic agenda, the public space and the private living space thus merged into a single entity, which made it possible to “zoom in on the details and zoom out to the galaxies” (Papakonstantinou 2020a).

Aède was co-produced by the conductor Tarana Sara Jobin, herself an Inayati Sufi, on behalf of Astana, the North American headquarters of the Inayati Order. The play was performed simultaneously live from Athens, New York, San Francisco, The Hague and Rome via Zoom. This was possible because prior to the lockdowns the global Inayati community had developed a digital infrastructure which they used as a platform for most of their gatherings.

The mystical play itself has an interesting history. Zia Inayat-Khan (b. 1971), the present spiritual leader (Pir) of the Inayati Sufi Order, had first discovered the hitherto unknown play by Noor in the summer of 2017. “As I read and reread it”, he recalls, “the play more and more powerfully impressed itself on my mind as a talisman of Noor’s presence and guidance” (Inayat-Khan 2018b). In a 2019 interview, Zia Inayat-Khan shared his belief that there are

some souls, when they leave this world, they look onward and don’t look back. There are others that keep connected, they still have some service to render. I believe Noor is such a soul. I feel her present and recently this was made very tangible when I was looking through our Sufi archive and discovered a file marked by her name and opening it discovered a play she had written which I had never before read. It was a hidden treasure…. A wisdom book that is hidden from humanity until its time has come… I believe this play of Noor’s is such a book.(Inayat-Khan, interview with author on 24 November 2019)

The play’s title “Aède” (deriving from the Greek aoidos) alludes to a Greek poet or poetess, who sang or recited while accompanying him- or herself on a lyre. The notion of soundscape, the significance of music in the play, immediately brings to mind Noor’s father, Hazrat Inayat Khan, who was himself an accomplished musician and who sought to communicate the divine nature of music in his concerts and his teachings. For Inayat Khan the power of music lay in awakening the memory of the soul to its origin—God. Music was “food for the soul”. Noor was a gifted harpist herself, aware of the healing effects of music on the body and the spirit. With this in mind, Papakonstantinou directed the performance and designed an ad hoc dramaturgy in which music and language were interwoven in a single narrative. The performers’ bodies vibrated, were pushed in unexpected directions, and were forced to maximize the smallest structural unit of language—word, syllable, phoneme.

Papakonstantinou thus reminds us of the healing power of music and theater, “a potential”, she says, “that we have lost sight of” (Papakonstantinou 2020b). This is because, just like bodies, the senses too can be trained, disciplined, instructed and refined. In the ancient Greek world, watching theater was understood to involve psychological healing to “cleanse” the psyche.20 Accordingly, a theater or odeon was often located near Asklepieia, sacred healing temples dedicated to the god Asclepius where incubation rites took place (Hartigan 2009, pp. 3, 15–16).

Papakonstantinou’s production of Aède invites the audience on a personal and spiritual journey, to an “immersive digital experience … in the fluid spaces of the mind”. Papakonstantinou sees “art as fluid, non-canonized forms of expression” in which there is a “deus ex machina, a divine presence” (Papakonstantinou 2020b). In doing so she deploys the concept of dynamic processes of perception, inspired by psychological (Hauser 2006) and phenomenological (Merleau-Ponty 1945) theories.

In this sense, Papakonstantinou presents Homer’s Odyssey, Noor’s mystical frame narrative, in the tradition of ancient Neoplatonic allegorical reading, as the soul’s descent into the sensory world epitomized by the Trojan War and its return to the world of spiritual beauty embodied by the kingdom of Ithaca (Lamberton 1989, pp. 199–200). This reading is underpinned by the fact that much of Sufi discourse is steeped in Neoplatonic emanationist readings (see Zarrabi-Zadeh 2020).