All my life I, essentially, thought about one thing: About the relation of phenomenon to noumenon, About discovering noumenon in phenomena, About its identification and implementation.

|

1. Introduction

Pavel Florensky’s philosophy of language has aroused historical and conceptual interest among researchers for decades. It concerns a number of original concepts that define Florensky as a thinker who was inclined to the mystical perception of linguistic categories and also his research on sacral linguistics. Being an apologist of onomatodoxy, i.e., a mystically colored orthodox doctrine, Florensky strove to build a philosophy of language that included a contemporary philosophical apparatus and a religious and magical dimension.

We designate the methodological sources of Florensky’s linguo-philosophical approach and reveal in them those aspects that directly or indirectly relate to his intuition of the magic of words. To do that, we briefly examine Florensky’s reception of two intellectual traditions, Palamism and Humboldtianism.

One of the authors of this article has already analyzed the details of Florensky’s reception of the Palamite doctrine (

Biriukov 2021, pp. 147–57;

Biriukov 2023), i.e., the doctrine formulated by the Byzantine theologian Gregory Palamas on the distinction in God of the unmanifested, unknowable, and unparticipated essence and the manifested, knowable, and participating energies.

The analysis demonstrated that the specifics of Florensky’s reception of the Palamite teaching is in ascribing the Palamite differentiation between essence and energies to any being, while in Palamas this differentiation applies only to God. Henceforth, Florensky extends this differentiation between the unknowable essence and knowable energies into the sphere of language.

Another very important tool, which Florensky used in line with the spirit of the times when he talked about the nature of language, was the Humboldtian distinction between ἔργον (ergon) and ἐνέργεια (energy) in language. At the beginning of the 19th century in Germany, Wilhelm von Humboldt developed a teaching about language pervaded with the spirit of his epoch, the epoch of Romanticism. Humboldt was thinking about the correlation between the language of particular peoples and its collective mentality. According to Humboldt’s intuition, the difference in the creative vision of the world by various nations is manifested in the difference among languages. The fundamental concepts, which influenced the later philosophy of language, were based on this intuition: these are the concepts of inner form, energy, and ergon. The inner form of the language, defining the specifics of the national-language worldview, was connected by Humboldt with the idea of language “energy” as opposed to “ergon”: language is a dialectical connection of the creative “energy” of a national spirit where the stable structure is “ergon”. According to Humboldt, if we try to grasp a language in its essence, it constantly evades us, and the only means to get an idea of it is to feel its energy—the integrity of its inner form.

Alexander Potebnja transferred the macrolinguistic scheme of Humboldt to the level of the word as such and developed his own theory of creative activity and poetics. Based on the Humboldtian notions of “inner form” and “energy”, Potebnja developed his own theory of creativity. The word’s inner form, which has an etymological nature and intermediates between phoneme and connotation, in Potebnja, becomes the dynamic and energetic beginning in language, conditioning its creative-poetical component. This essentially influenced the formation of the theories of language—and especially of poetic language—in the Russian modernism of the beginning of the 20th century and became the foundation for the presence of variously refracted Humboldtian schemes, embedded in the notions of the unmanifested and the manifested, in these theories.

2. Florensky’s Reception of the Linguistic Scheme of Humboldt and Potebnja in the Late 1900s

In his most important work, “Thought and Language”, Potebnja emphasized the following linguistic scheme:

“In the word, we discern the external form, that is the articulated sound, the content, objectified with the help of sound, and the internal form, or the closest etymological meaning of the word, the way the content is expressed”.

For Potebnja, the static etymon, around which the dynamic sound flesh is being formed, is the internal form of the word.

In Florensky, one of the earliest descriptions of word structure is his lectures on the history of ancient philosophy, which he delivered at the Moscow Spiritual Academy in 1908–1910. In these lectures, Florensky, diverting from the history of ancient philosophy, reasons at length about the nature of language and naming. Basic intuition, given by Florensky in these lectures, is that

“the name of a thing is not just an “empty” nickname for an object, not “sound and smoke”, not the conditional and accidental invention ex consensu omnium, with the consent of all, but its designation full of meaning. In short, the name of a thing is the identified, or identifiable essence of a thing”.

Discussing in these lectures the nature of names, Florensky takes the Humboldtian differentiation between ἐνέργεια and ἔργον as the basis and offers his understanding, according to which language in its nature is a dynamic “activity”, ἐνέργεια, and not some static “action”, ἔργον. In terms of energy, language is the creativity of an individual and an expression of their freedom. However, at the same time, language also has a static element expressed, for instance, in grammar rules or how language is fixed in writing. In this respect, language is a supra-individual reality, the heritage of an entire nation, and in this sense, language is something coercive for an individual and is externally applied to the latter. Inside those frames, which are imposed externally by the people’s language element, the creatological-energetic function of language may become manifested, which is continuously actualized by the individuals who are the language carriers (

Florensky 2015, pp. 51–52).

Proceeding from Potebnja’s language scheme, Florensky further connects the external form of the word with a phoneme, and the internal form of the word with its etymological meaning and idea, to which this meaning refers (

Florensky 2015, pp. 96–98). During his reasoning, deconstructing the word “kipjatok” (hot-water) in detail, Florensky rethinks the Potebnian language scheme, talking about the place of sound, φωνή, in the word.

In his thinking, Florensky departs from his basic intuition in which there is a specific matching between the sound of the word (

phoneme), its

etymon, and

sememe (meaning) (

Florensky 2015, p. 105). This specific matching between the sound of the word and the rest of the elements of the word structure, according to Florensky, points to the magical nature of the word (

Florensky 2015, pp. 103–4). In his thoughts on the nature of words, Florensky takes the

phoneme as the departure point and paves the way from

phoneme and

morpheme through

ethymon to

sememe.

This closeness and connection between

phoneme and

sememe are explained by the fact that human consciousness is directly connected to the human body, and a thought in the mind triggers a muscle contraction, first of all in the vocal muscles. Even in the case of thinking, which occurs without emitting sound, the articulatory contraction of the muscles still takes place but without releasing air. In this case, Florensky talks about potential sounds and inaudible words (

Florensky 2015, p. 60).

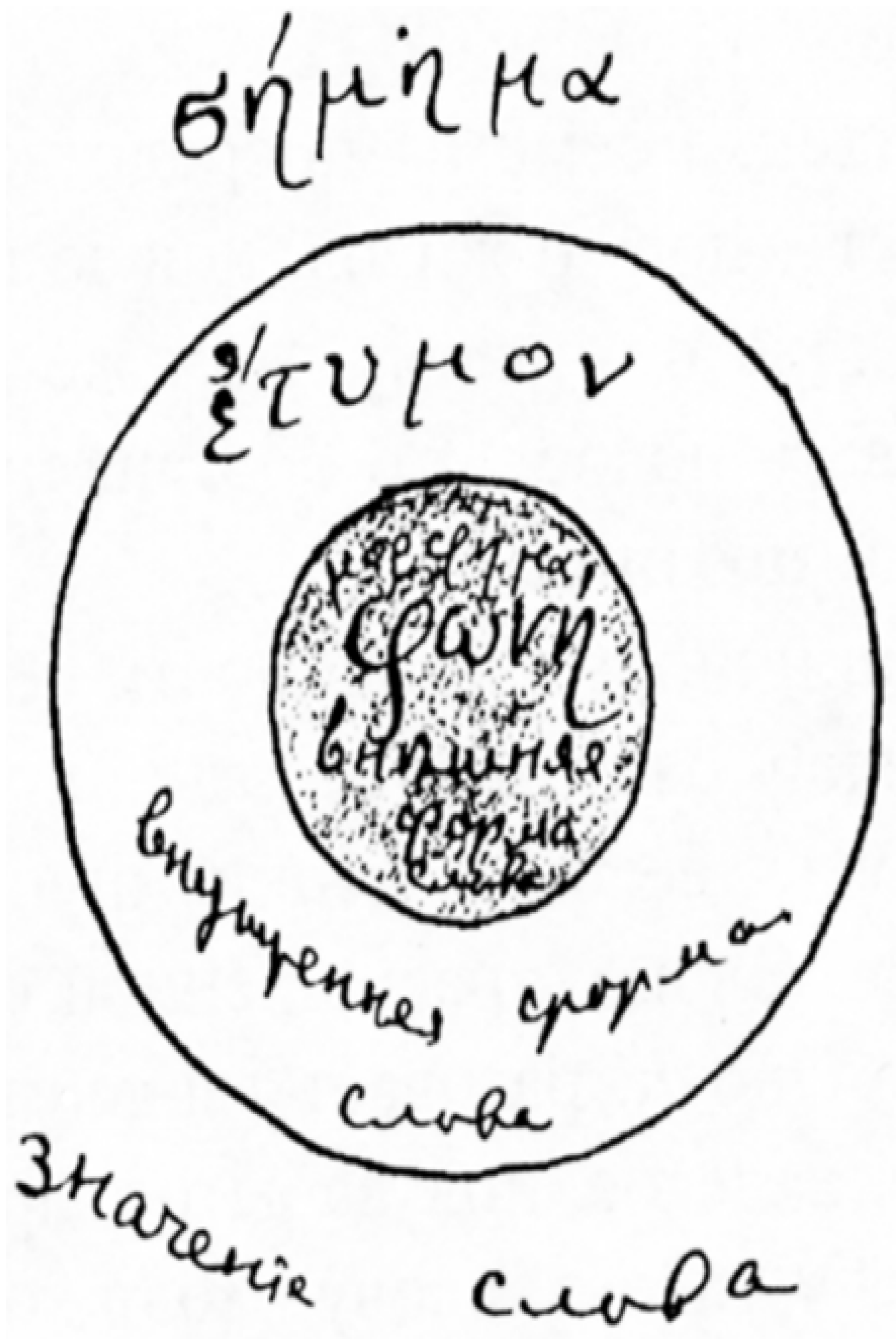

As a result, Florensky depicts a paradoxically graphical word scheme, where the sound, φωνή, although being marked as an external form, ends up within the word sphere, while

etymon, which corresponds to the internal form of the word, is located outside of this external sphere, or the sphere of sound.

1Figure 1 illustrates the rethinking of Potebnja’s scheme and is taken from Florensky’s work “From the history of Ancient philosophy”.

3. The Specifics of Florensky’s Understanding in the Early 1910s of the Names Applied to God

This specific teaching of Florensky regarding word structure, which presupposes a rigid connection between a word’s sound and its etymon, morpheme, and meaning was vividly revealed in Florensly’s position as a participant in the name-glorifying debates.

It was precisely during these debates when Florensky discovered the Palamite teaching. However, during the early stage of the debates in the 1910s, Florensky used the Palamite distinction between essence and energies only for the construction of his “formula of name-glorification” (

Biriukov 2023) but had not yet applied it to the sphere of language. As we shall see, Florensky did this later. Here, we limit ourselves to a consideration of the specifics of Florensky’s position regarding names that are applied to God only at the early stage of the name-glorifying debates at the beginning of the 1910s and do not touch on the development of Florensky’s views in this direction.

In these debates on whether it is possible to consider divine names as God, Florensky’s position was the most radical and, owing to its radicality, aroused suspicions even among his allies. Judging by Florensky’s correspondence with Antony Bulatovich, who was the leading public defender of name-glorification in the 1910s, the question about the status of sounds in names, regarding God, and in the name Jesus, was actively discussed at the very start of the name-glorifying debates in 1912. Even at this time, Florensky, who insisted that divinity was found in the very letters and sounds of the name Jesus, did not find understanding among other defenders of name-glorification. Thus, in a letter from 2 December 1912, Bulatovich wrote to Florensky, answering a letter which is no longer extant:

“You express the thought that the name Jesus is God with the sounds of it. I am very ready to believe it, but so far, I do not have enough data to state it. [...] Sounds in their structure are neither essence nor being, but the vibration of an air wave and, consequently, we can hardly talk about this vibration being Christ. Finally, sounds are not an accessory necessary for the name of God and a word as such, because words work in the mind without sound. Therefore, I am inclined to view sounds the same way as letters, that is, as conditional signs”.

A similar understanding of names by Florensky regarding God is also reflected in his own texts related to the early phase of the name-glorifying debates. Thus, in his critical notes written in the middle of 1913, to the article of archbishop Nikon Rozhdestvenskii “The Great Temptation around the Most Holy Name of God”, which had a name-glorifying character, Florensky expresses the position according to which in the name of God, sound and meaning (image) exist in a united and inseparable form. Commenting on Nikon’s words, “not from the name’s sounds, not from an abstract idea, not from the name imagined by the mind, but from God the ray of grace pours upon him”, Florensky insists that exactly like in the Eucharist, the bread and wine are inseparably connected to divine grace, one can be separated from another only in mental abstraction, and they are not different in reality the same way sound and meaning (image) compose one whole in the name of God and can be differentiated only in mental abstraction

“Contrasting sounds to God makes sense only for a positivist, which Nikon is, and for whom there cannot be anything in this world that is “unworldly”. Yes, “not from sounds”, but the thing is, that in Name there are no sounds, no images, as there are none in the Holy elements of bread and wine, and as there is no language in the word of God. As the conjoining of heaven and earth has occurred, then it is impossible to contrapose one to another in reality, and it is possible only in abstraction”.

The foundation for this position of Florensky was the understanding that the name of God, including all its components, is deified, as it indivisibly and inseparably co-exists with the Deity. In this respect, Florensky implicitly refers to the known Chalcedonian formula, describing in these terms the relation between the divine and human natures in Christ. Respectively, he blames the opponents of name-glorification for Nestorianism. Florensky writes about it in his notes to Bulatovich’s book “The Apology of Faith in the name of God and in the name of Jesus”:

“Nestorius separated human nature from the divine nature, and this is exactly what they do, separating It. We, the Orthodox, acknowledge the name Jesus deified, and although not conjoined with Deity, but also inseparable from It. Where the body of our Lord is, He is there, where His Name is—He is there, with all the fullness of His Divine nature. We do not separate natures (as opponents of Name-glorifiers and Nestorians do), but we also do not conjoin them”.

Thus, the specifics of Florensky’s philosophy of language are in the accent on the specific relationship in a word between the sound and meaning components: this can be an accent on the link of these components in natural language or on their indivisibility in the case of sacral language. In the case of natural language, this position of Florensky is manifested in his intention to reveal the meaning of a word based on its sound-etymological foundation. This differs Florensky’s intuition from the approach of his close ally Bulgakov, who presented words as the means to get closer to Sophia and from the philosophy of language of his follower in the first half of the 1920s, Losev, who argued that the words of natural language acquire their own existence only in the perspective of the uncreated proto-language.

4. Florensky’s Development of the Potebnian Language Scheme at the Turn of the 1920s

Stephen Cassedy (

Cassedy 1991, pp. 543–47), in his research on the philosophy of language of Florensky, draws attention to the significant discrepancy between Florensky’s presentation of the theme of a word’s inner form from that of Potebnja’s teaching, on which the former had relied. For both thinkers, a word’s inner form is the most important dimension of a word’s structure. As Cassidy also demonstrates, Florensky and Potebnja understand the word’s inner form differently. To be precise, for Potebnja, it includes a static etymon, around which the dynamic sound flesh and a clear-cut meaning are fixed. On the contrary, Florensky attributes the dynamic

sememe to the word’s inner form, which is dependent on the individual properties of the speaker’s speech, and the static and universal, regarding language use, phoneme and morpheme, comprise the outer form (

Cassedy 1991, p. 545).

This is an important observation by Cassedy, but the problem with his concept is that he does not account for the development of Florensky’s teaching on the word’s inner form. As we have seen, in his early lectures on ancient philosophy, Florensky explicitly followed exactly the Potebnian understanding of the word’s inner form, presupposing that etymon is this inner form. However, judging by the graphic scheme drawn by Florensky, it becomes obvious that Florensky was already moving away from the Potebnian understanding of the word’s inner form. In texts produced at the end of the 1910s and the early 1920s, Florensky actually explicitly rethinks the Potebnian understanding of the word’s inner form. Cassedy’s observations are especially pertinent regarding this period of Florensky’s ideas.

Thus, in the work “The construction of a word” (1919?), Florensky writes about the word’s inner and outer forms. “The outer form is the consistent, common, hard matter that the word rests upon: it can be compared to the body of a living being. If it was not for this body, there would be no word as a supra-individual phenomenon; we receive this body as spiritual beings, from the people, and without the outer form we would not participate in speech. On the contrary, it is natural to compare the word’s inner form with the soul of this body, helplessly circuited into itself as long as it does not have an organ of manifestation, but the light of consciousness extends far the moment such organ was granted. This soul—the inner form—comes from an act of spiritual life. If we can speak about the outer form, albeit only somewhat precisely as something eternally unchangeable, then the inner form should be correctly understood as continuously being born and as the manifestation of the very life of the spirit. The process of speech is the addition of the speaking to the supra-individual, cathedral unity, and mutual germination of the energy of an individual spirit and the energy of the peoples’ common human mind. And, therefore, in the word, as during the meeting of two energies, there are necessarily both forms. The outer form serves the common mind, and the inner form serves the individual mind. If we are to continue with our comparisons to an organism, then the words must be differentiated in this body: the backbone, whose main function is to hold the body and give it shape and other tissues that carry life itself in them. In the language of linguistics, the former is referred to as the word’s phoneme, and the latter is a morpheme. It is obvious that the morpheme serves as the connecting link between the phoneme and the word’s inner meaning, or the sememe. Thus, the structure of the word is trichotomous. The word can be represented as the circles, which successively grasp each other. For graphical purposes, it is useful to represent the word’s phoneme as the main nucleus, or the bone wrapped in a morpheme which, in turn, supports sememe” (

Florensky 2000, vol. 3 (1), pp. 213–14).

It is interesting that, at the end of the citation, Florensky uses the same scheme of a word’s structure (not graphically but describing it verbally) that he used in the lectures on the history of ancient philosophy, according to which the phoneme is inside the word’s sphere, wrapped in the morpheme or etymon which, in turn, is surrounded by the sememe. When Florensky talks about a word’s inner form here, in contrast to his lectures, he argues that the sememe, and not the etymon-morpheme, is related to the word’s dynamic inner form, while morpheme and phoneme comprise the static outer form. This is precisely where the distinction between Florensky’s word scheme and the Potebnian one becomes clear. If we contrapose the notion expressed here about a word’s inner form as sememe with the pseudo-graphical scheme of a word’s construct, which Florensky mentions, then we see that paradoxically, here, the inner form ends up on the very periphery of a word’s sphere. We can discern the presence of the energy discourse in Florensky’s deliberations on the nature of language in the abovementioned citation from “The construction of a word”. This theme is more clearly expressed in the research dedicated to the nature of religious language that soon followed Florensky’s work. Thus, in the essay “About the Name of God” (1922), Florensky says:

“a word, as for any symbol, is beyond the confines of rational understanding. The body of a word seems elementary at first. But even West-European insights into its nature which, in essence, were very shallow and rude, reveal three overlapping formations:

- (1)

Something physical—a phoneme. It is understood as the vibration of air (sound), as well as those internal feelings of the body that we experience when we pronounce the word’s sounds, and also the psychological impulse, which triggers the word’s pronunciation. Therefore, all physiological and physical manifestations which occur during the speaking of a word are understood as the first matter of the word, or phoneme.

- (2)

Morpheme. Every word corresponds to known categories, or to speak in the language of knowledge, is cast into logical categories, for instance essence, substance, etc., and grammatical: genus, etc., and in general everything else that we connect to the initial representation, for example the word “birch” contains all the information that we know about its growth, shedding, tasty juice, internal make-up, positive features about being used as firewood, the chemical elements included in its make-up, etc.

- (3)

Overlapping is sememe, or the word’s meaning. It is constantly moving and changing. For example, I can say “birch” in a dream-like, or totally material fashion. It is a known word’s flavor. Out of literary genres, it is most clearly expressed in poetry. To understand the word correctly, one needs to understand the context of what exactly someone wanted to say here and now.

A phoneme is the word’s backbone, the most stable and the least necessary, although at the same time, it is the vital condition for the word’s life. A morpheme is the word’s body, and sememe is its soul. All this content is present in it, as the entire body is present in semen, as a son receives his body from his father, and we can say that father is present in the son, although the father’s organism stays with him, and father does not lose anything. Here, we can see the distinction between οὐσία and ἐνέργεια, or the organism on its own and the activity of the energy present in the organism. And this energy, being different from the organism, is at the same time its energy and cannot be separated from it, so when we touch its energy, we must touch the organism itself”.

Here, Florensky views a word as a symbol, which is beyond the limits of rational understanding. In this context, Florensky deliberates about the relation between the phoneme, morpheme, and sememe of a word, using the language of the Palamite theology, which Florensky starts to use actively regarding the categories of the symbol (see

Biriukov 2021). He singles out phoneme, the word’s physical-physiological component; morpheme, the static image behind the word’s meaning; and sememe, the meaning of the word given in the context and the intention of the speaker. Then, Florensky turns to the Palamite language of the distinction between essences and energy. He represents a word, which is likened to an organism, as consisting of three components, each of which is also understood as an energizing organism. As a result, when using the Palamite language, Florensky speaks about a word as the energizing essence perceived through energies but at the same time not comprehensible by rationalistic understanding. This is how the Palamite discourse becomes interwoven with Florensky’s philosophy of language.

5. The Magicism of the Word in Pavel Florensky

Florensky describes the phenomenon of the magic of the word from two interconnected positions. Let us denote these positions as autonomous and intentional.

5.1. Autonomous Word Magicism

Florensky’s understanding of the magicism of the word has macro- and micro-dimensions. On the macro-level, there are energies of the peoples’ elemental language environment in sememe, which Florensky refers to as occult and which developed throughout the ages of the usage of a language’s words. One can become part of this occult energy and enter the stream of the peoples’ elemental language environment in such a way that takes the traveler all the way to unfamiliar shores:

“Everything that we know about a word encourages us to point at its high level of charge with the occult energies of our being, which are stored in the word and get collected with every occurrence of its usage. In the layers of the word’s sememe, the inexhaustible energies are stored, which have been collected for centuries from millions of mouths”.

“[...]it is enough to grab the end of the thread, twisted into a ball with a powerful will and broadly embracing the mind of the people, and the inevitable sequence will guide the individual spirit along the entirety of this thread no matter how long it is, and imperceptibly for itself, this spirit will end up at the thread’s other end, in the thickness of the whole ball, next to notions, feelings, and acts of will, to which the individual did not have any intention to give itself to”.

On the micro-level, if we take a word as such, the magicism is revealed through the discourse of the independent and autonomous existence of words and names. Florensky imagines words as living and independent beings. Let us turn to some quotations from “The magicism of the word” and “The Panhuman roots of an idealism”:

“a word is a

self-enclosed little world, an organism, which has a thin structure and a complex, closely knit makeup. […] In it, there is a physical-chemical moment, corresponding to the body, a psychological moment, corresponding to soul, and an odic, or altogether occult moment, corresponding to the astral body”

2.

“The word of a wizard is the emanation of his will; it is the manifestation of his soul, an independent center of forces, as if it were a living being with a body woven from air, and the internal structure consisting of a sound wave”.

This determined Florensky’s research focus on the meaning of a word’s parts, letters, and sounds, and singling out in them cultural, metaphysical, mathematical, and other layers. This focus on sound, this clearing of a sound path toward “the mystery of the word”, fundamentally differentiates Florensky’s approach from that of Potebnja (cf.

Boneckaja 2018, p. 368).

Regarding names, Florensky’s analysis of the “sound-ontological structure” of the name Mariul

3 in his essay

Names (Imena) can be used as an example of this focus on sound of Florensky’s philosophy of language. Florensky produces a transcription of each letter of this name in Hebrew, relates them to numbers and successively analyzes the meaning of each word’s elements. Based on that, Florensky makes a conclusion about what is hidden behind this name:

“in the name Mariul, the sounds transmit a passive, and at the same time external influence of the feminine nature, understanding this gender feature in terms of the lower, material meaning. This action conquers space, boundlessly stretches forward, because it has its own movement. This is the manifestation of the internal power, but not its highest light-bearing plane, but on the edge between existence and non-existence, although not a purely materialist movement, but something close to it”.

As Donatella Ferrari-Bravo points out, Florensky’s method of name analysis has parallels in kabbalistic linguistic practices (

Ferrari-Bravo 1988, p. 143), to which Florensky often turned to. Interestingly, Florensky dedicates his special lectures to the Kabbalah, which had not been published yet. The preliminary analysis of these lectures conducted by Anna Reznichenko shows the substantial influence kabbalism had on Florensky, which is expressed, for instance, in the idea of a universal alphabet, singling out a language’s primary elements, etc. (

Reznichenko 2017).

This line in Florensky’s teaching assumes that magicism is naturally intrinsic to words and names. Human intention does not have any bearing on this discourse. However, Florensky’s teaching on the magicism of language also emerges in connection with the theme of intentionality.

5.2. Intentional Word Magicism

As we have seen in the excerpt from Florensky’s essay “On the name of God”, in contrast to his earlier lectures on ancient philosophy, a word’s inner form is connected to sememe, which, in turn, is understood not simply as the meaning of a word, but as the intention with which an individual is pronouncing a given word with a given meaning. This turn of Florensky toward intentionality is also reflected in his teaching on the magicism of a word.

To clarify this aspect of magicism, let us represent it in a broader context. From all words, Florensky singles out those that possess special properties. When Florensky talks about them, he uses a variety of terms to describe these properties, such as magical power, maturity, saturation, synthesizing, and density. In his essay “The Magicism of the Word”, Florensky talks about the hierarchy of the words’ classes depending on the level of the linguistic “magical power”, i.e., the word’s impact on reality: an ordinary word, a term, a formula, or a proper name

4 (

Florensky 2000, vol. 3 (1), p. 241). Different steps of this hierarchy manifest the differing measure of the noumenal presence in the sensual sound flesh of a word. This measure depends on the intentional dimension when working with a word.

Florensky argues that, practically, a low level of “magical power” does not require a conscious intention when speaking the words:

“a magically powerful word does not necessarily require, at least on the lowest levels of magic, an individually-personal tensing of the will, or even a clear comprehension of its meaning”.

The stronger the word’s magical power, the stronger the role of the intentionally willed moment during its use. Thus, speaking of proper names, Florensky mentions the willed origins of an individual, which must be expressed for the name to work:

“Name itself blesses or curses, and we are only its tool for its actions and the favorable environment in which it functions. The name rules me, although my consent is necessary for that”.

The intentional aspect in magicism has meaning in verbal expressions (formulas) of various religious practices: priestly prayers, charms, or spells. According to Florensky, all these types of speaking, even if their meaning is unclear, require intention for their implementation. As Florensky points out in “The magicism of the word”:

“A wise woman, whispering spells and incantations, the clear meaning of which she does not comprehend, or a priest uttering a prayer, in which not everything is clear to him, are not such ludicrous manifestations, as might seem at the beginning. As the spell is being pronounced, the manifestation of a corresponding intention to pronounce it is being established. And through this, contact between the word and the individual is established, and the main endeavor has been accomplished: the rest will occur by itself, because the word itself is already a living being, which has structure and energies. Of course, more sensitivity and tensed manifestations of will would be the favorable factors contributing to the opening of the word in this case. However, this factor sooner clears the clogged ducts for the word, in that creating action, and after a certain minimum of what was already achieved, it is not definitely needed any longer”.

Thus, we can speak not only about the magicism of words in terms of acknowledging their certain autonomy but also about the intentional aspect of magicism, which considers the intention of a person pronouncing a religious/magical formula. Here, this intention serves as an impulse to the actualization of the words’ magical potential. If we look at this intentional aspect of magicism through the prism of the philosophy of language and Florensky’s teaching on word structure in the version dating back to the late 1910’s and early 1920s, it would be correct to surmise that, according to Florensky, this actualization of the intentions of the word’s magical potential is carried out through the sememe:

“everyone attributes their own meaning, corresponding to the needs of the current case, to the plastic sememe. Each connects the root meaning to elusive, but very significant, spiritual overtones, the consciousness of each word sprouts its aerial roots”.

6. Conclusions

We have analyzed the evolution of Pavel Florensky’s teachings about language and the word from the end of the 1910s to the early 1920s in the context of two lines of influence on the basis of which this teaching developed. One line was the Humboldtian-Potebnian differentiation between energy and ergon in language and the teaching about the word’s inner form. The second line was the Palamite distinction between essence and energies in God. In his reasoning about language, Florensky proceeds from intuition that there is a rigid connection between the word’s sound (phoneme), its morpheme and etymon (etymological meaning), its sememe (the given here and now meaning), and its denotate. According to Florensky, this points to the magicism of the word as such.

In his lectures on the history of ancient philosophy, in 1908–1910, Florensky turns to the Humboldtian philosophy of language and follows the Potebnian scheme, where the word’s outer form relates to phoneme, and its inner form to etymon and sememe, which follows etymon. Florensky also draws a paradoxical graphic word scheme, where the sound, albeit marked as an external form, is placed inside the word’s sphere, while etymon, which corresponds to the word’s inner form, is located outside of this external sphere, the sphere of sound.

At the beginning of the 1910s, Florensky, having become a participant in the name-glorifying debates, adhered to the line presupposing a rigid connection between the word’s sound (the name, which is applied to God), its meaning, and its denotate. During these debates, Florensky embarked on the appropriation of the Palamite discourse distinguishing between the unknowable essence and knowable energies in God. Florensky started applying this distinction to any being.

All these lines converged in Florensky’s thoughts on the nature of language in the late 1910s and the early 1920s. He turned again to the Humboldtian–Potebnian language scheme but rethought it, speaking of the intentionally charged sememe as the word’s inner form. In this respect, Palamite discourse enters Florensky’s philosophy of language, which distinguishes between the unknowable essence and the knowable energies of this essence. In the end, Florensky, using Palamite language, talks about a word as energizing essence, perceived according to its energies but not understood rationally.

Florensky had turned to the theme of the magicism of the word in his early lectures on the history of ancient philosophy. This theme was developed in Florensky’s texts written in the late 1910s and the early 1920s. In these texts, we single out two aspects of the understanding of the magicism of the word, which were key for Florensky, namely the aspect revealed in the discourse of the independent and autonomous existence of words and names, and the aspect presupposing the intentionally willed moment in the phenomenon of the magicism of the word. Florensky linked both positions to the hierarchy of linguistic “magical power”, i.e., the measure of the word’s impact on reality. Florensky also connected the measure of “magical power” with the measure of intention in the speech. Here, in the principle of intentionality, the Humboldtian–Potebnian line and the magicism-oriented line in Florensky’s thoughts about the word, both of which were previously given in his lectures on the history of ancient philosophy at the end of the 1900s, converge.