Understanding Personal Stances on Religion: The Relevance of Organizational Behavior Variables

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptualizing Personal Stances on Religion

2.2. Operationalizing Personal Stances on Religion

2.2.1. Motivation

2.2.2. Beliefs

2.2.3. Perceptions

3. Model Development

4. Data and Methods

4.1. Data Collection and Participants

4.2. Measures

- -

- Motivations—Four items measure Relatedness Motivation and four items measure Growth Motivation. A 5-point scale is used, ranging from 1 = Indifference to 5 = High interest.

- -

- Beliefs—Three items measure Christian Beliefs, and three items measure Humanistic Beliefs. A 5-point scale is used, ranging from 1 = Completely disagree to 5 = Completely agree.

- -

- Perceptions—Four items measure Perceptions of Support and four items measure Perceptions of Politics. A 5-point scale is used, ranging from 1 = Completely disagree to 5 = Completely agree.

- -

- Religious Commitment—Three items measure the frequency with which respondents engage in Catholic ritual practices, including Mass, Eucharist Communion, and Reconciliation. For Mass and Eucharist Communion, an 8-point scale is used, ranging from 1 = Never to 8 = More than once a week. For Reconciliation, a 7-point scale is used, where 1 = Never and 7 = More than once a month. This scale is identical to the one used for Mass and Eucharist Communion, except that the last point (8) is not used, because it is not a recommended practice to receive Reconciliation more than once a week.

- -

- Religious Socialization—Two items measure the exposure to religious socialization as a child. The first concerns socialization in the church and is an additive index, including the usual steps children follow in the Catholic Church, namely: Baptism, Catechism before First Communion, First Communion, Catechism after First Communion, Profession of Faith, and Confirmation. The second item is also an additive index and includes issues of religious socialization by the family, such as receiving a Catholic education and whether the father/mother went to Mass weekly/prayed when the respondent was a child.

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Measurement Models

5.2. Structural Model

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ackerson, Betsy V. 2018. The Influence of Catholic Culture Type on the Spiritual Lives of College Students. Journal of Catholic Education 21: 133–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Adamopoulos, John, and Walter J. Lonner. 1997. Absolutism, Relativism, and Universalism in the Study of Human Behavior. In Psychology and Culture. Edited by Walter J. Lonner and Roy J. Malpass. Needham Heights: Allyn & Bacon, pp. 129–34. [Google Scholar]

- Akter, Shahriar, John D’Ambra, and Pradeep Ray. 2010. Service Quality of MHealth Platforms: Development and Validation of a Hierarchical Model Using PLS. Electronic Markets 20: 209–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderfer, Clayton P. 1969. An Empirical Test of a New Theory of Human Needs. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 4: 142–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, Gordon W. 1950. The Individual and His Religion. New York: The MacMillan Company. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, Gordon W., and J. Michael Ross. 1967. Personal Religious Orientation and Prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5: 432–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshehri, Faisal, Marianna Fotaki, and Saleema Kauser. 2020. The Effects of Spirituality and Religiosity on the Ethical Judgment in Organizations. Journal of Business Ethics 174: 567–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, James C., and David W. Gerbing. 1988. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin 103: 411–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, Richard P., and Jeffrey R. Edwards. 1998. A General Approach for Representing Constructs in Organizational Research. Organizational Research Methods 1: 45–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, Betsy Hughes, David C. Dollahite, and Loren D. Marks. 2020. How Parents Balance Desire for Religious Continuity with Honoring Children’s Religious Agency. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 13: 222–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C. Daniel, Patricia Schoenrade, W. Larry Ventis, and C. Daniel Batson. 1993. Religion and the Individual: A Social-Psychological Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Batson, C. Daniel. 1976. Religion as Prosocial: Agent or Double Agent? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 15: 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Jan-Michael, Kristina Klein, and Martin Wetzels. 2012. Hierarchical Latent Variable Models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for Using Reflective-Formative Type Models. Long Range Planning 45: 359–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, Marie-Claude, David Gefen, and Detmar W. Straub. 2001. Validation in Information Systems Research: A State-of-the-Art Assessment. MIS Quarterly 25: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewczynski, Jacek, and Douglas A. MacDonald. 2006. RESEARCH: “Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Allport and Ross Religious Orientation Scale With a Polish Sample”. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 16: 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burris, Christopher T. 1994. Curvilinearity and Religious Types: A Second Look at Intrinsic, Extrinsic, and Quest Relations. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 4: 245–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campiche, Roland J., Alfred Dubach, Claude Bovay, Michael Krüggeler, and Peter Voll. 1992. Croire en Suisse(s): Analyse des resultats de l’enquête menée en 1988/1989 sur la Religion des Suisses. Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme. [Google Scholar]

- Campiche, Roland J., Raphael Broquet, Alfred Dubach, and Jörg Stolz. 2004. Les Deux Visages de la Religion: Fascination et Désenchantement. Genève: Labor et Fides. [Google Scholar]

- Catholic Church, ed. 1997. Catechism of the Catholic Church: Revised in Accordance with the Official Latin Text Promulgated by Pope John Paul II, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. [Google Scholar]

- Charlier, Jean-Émile, and Frédéric Moens. 2002. Métamorphose d’un sacrement. La communion, de la pratique socialisée à la participation sensible. Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions 119: 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Adam B., John D. Pierce, Jacqueline Chambers, Rachel Meade, Benjamin J. Gorvine, and Harold G. Koenig. 2005. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Religiosity, Belief in the Afterlife, Death Anxiety, and Life Satisfaction in Young Catholics and Protestants. Journal of Research in Personality 39: 307–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, José Pereira. 2020. Religião em Portugal: Análise Sociológica, 1st ed. Lisboa: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa. [Google Scholar]

- Danzger, M. Herbert. 1998. The “Return” to traditional Judaism in the United States, Russia and Israel: The impact of minority to majority status on religious conversion processes. In Religion in a Changing World: Comparative Studies in Sociology. Edited by Madeleine Cousineau. Religion in the Age of Transformation. Westport: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, James D., and Dean D. Knudsen. 1977. A New Approach to Religious Commitment. Sociological Focus 10: 151–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davie, Grace. 2000. Religion in Modern Europe: A Memory Mutates. European Societies. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- de França, Luis. 1973. Estudo sobre Liberdade e Religião em Portugal. Lisboa: Instituto Português de Opinião Pública e Estudos de Mercado & Moraes Editores. [Google Scholar]

- De Vos, Ans, Sara De Hauw, and Beatrice I. J. M. Van der Heijden. 2011. Competency Development and Career Success: The Mediating Role of Employability. Journal of Vocational Behavior 79: 438–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denz, Hermann. 2009. Religion, Popular Piety, Patchwork Religion. In Church and Religion in Contemporary Europe. Edited by Gert Pickel and Olaf Müller. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, Michael J. 1985a. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Religiousness: Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 48: 400–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, Michael J. 1985b. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Religiousness: The Empirical Research. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 24: 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, Robert, Peter Fasolo, and Valerie Davis-LaMastro. 1990. Perceived Organizational Support and Employee Diligence, Commitment, and Innovation. Journal of Applied Psychology 75: 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, Robert, Robin Huntington, Steven Hutchison, and Debora Sowa. 1986. Perceived Organizational Support. Journal of Applied Psychology 71: 500–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira Lages, Mário. 2001. A religiosidade popular na segunda metade do século XX. In A Igreja e a Cultura Contemporânea em Portugal, 1950–2000. Edited by Manuel Braga da Cruz and Natália Correia Guedes. Lisboa: Universidade Católica Portuguesa, pp. 379–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, Maria Francisca. 2018. A emergência e agendamento políticos das questões de fim de vida em Portugal. Emergency and agenda-setting of end life issues in Portugal. In X Congresso Português de Sociologia na era da “Pós-Verdade”? Esfera Pública, Cidadania e Qualidade da Democracia no Portugal Contemporâneo. vol. 19, Covilhã. Available online: https://aps.pt/wp-content/uploads/X_Congresso/Saude_XAPS-41110.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Ferris, Gerald R., Gloria Harrell-Cook, and James H. Dulebohn. 2000. Organizational Politics: The Nature of the Relationship between Politics Perceptions and Political Behavior. In Research in the Sociology of Organizations. Bingley: Emerald (MCB UP), vol. 17, pp. 89–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flere, Sergej, and Miran Lavrič. 2008. Is Intrinsic Religious Orientation a Culturally Specific American Protestant Concept? The Fusion of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Religious Orientation among Non-Protestants. European Journal of Social Psychology 38: 521–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flere, Sergej, Keith J. Edwards, and Rudi Klanjsek. 2008. Religious Orientation in Three Central European Environments: Quest, Intrinsic, and Extrinsic Dimensions. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 18: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Leslie J. 2007. Introducing the New Indices of Religious Orientation (NIRO): Conceptualization and Measurement. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 10: 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandz, Jeffrey, and Victor V. Murray. 1980. The Experience of Workplace Politics. Academy of Management Journal 23: 237–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genia, Vicky. 1993. A Psychometric Evaluation of the Allport-Ross I/E Scales in a Religiously Heterogeneous Sample. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 32: 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, Alberta, and Guya Accornero. 2018. The Catholic Church and the Crisis: The Case of Portugal. Journal of Contemporary Religion 33: 261–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, Bruno, Teresa Fagulha, and Ana Sousa Ferreira. 2016. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Religious Orientation in Portuguese Catholics. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 19: 897–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, Michael A., and W. Justin Dyer. 2020. From Parent to Child: Family Factors That Influence Faith Transmission. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 12: 178–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, Richard L. 1984. Measurement: The Boon and Bane of Investigating Religion. American Psychologist 39: 228–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, Richard L. 1994. Toward Motivational Theories of Intrinsic Religious Commitment. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 33: 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, Richard L., and G. Daniel Venable. 1983. Development of an “Age Universal” I-E Scale. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 22: 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, Richard L., and Susan E. McPherson. 1989. Intrinsic/Extrinsic Measurement: I/E-Revised and Single-Item Scales. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 28: 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, Sanne, and Paul Vermeer. 2013. Understanding Religious Disaffiliation: Parental Values and Religious Transmission over Two Generations of Dutch Parents. Journal of Empirical Theology 26: 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnoe, Marjorie Lindner, and Kristin A. Moore. 2002. Predictors of Religiosity Among Youth Aged 17–22: A Longitudinal Study of the National Survey of Children. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: 613–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, Charles H., and Glenn S. Sanders. 2003. Religiosity and Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis of Recent Studies. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42: 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joe F., Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2011. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 19: 139–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., ed. 2017. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jr., G. Tomas M. Hult, Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt, eds. 2017. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hardesty, Amber, and James W. Westerman. 2009. Relating Religious Beliefs to Workplace Values: Meta-Ethical Development, Locus of Control, and Conscientiousness. Academy of Management Proceedings 2009: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardesty, Amber, James W. Westerman, Rafik I. Beekun, Jacqueline Z. Bergman, and Jennifer H. Westerman. 2010. Images of God and Their Role in the Workplace. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion 7: 315–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervieu-Léger, Danièle. 1999. La Religion en Mouvement: Le Pélerin et le Converti. Paris: Flammarion. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, Heather. 2020. Exploring Autonomy and Relatedness in Church as Predictors of Children’s Religiosity and Relationship with God. Christian Education Journal: Research on Educational Ministry 17: 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itçaina, Xabier. 2019. Médiations Catholiques en Europe du Sud: Les Politiques Invisibles du Religieux. Sciences des Religions. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes. [Google Scholar]

- James, William. 1902. The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature, Being the Gifford Lectures on Natural Religion Delivered at Edinburgh in 1901–1902, Dover thrift editions. Mineola and New York: Dover Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kidder, Annemarie S. 2010. Making Confession, Hearing Confession: A History of the Cure of Souls. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, Lee A. 1989. A psychometric analysis of the Allport-Ross and Feagin measures of intrinsic-extrinsic religious orientation. In Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion. Edited by Monty L. Lynn and David O. Moberg. Greenwich: JAI Press, vol. 1, pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, Lee A., and Ralph W. Hood. 1990. Intrinsic-Extrinsic Religious Orientation: The Boon or Bane of Contemporary Psychology of Religion? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 29: 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingenberg, Maria, and Sofia Sjö. 2019. Theorizing Religious Socialization: A Critical Assessment. Religion 49: 163–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G., and David B. Larson. 2001. Religion and Mental Health: Evidence for an Association. International Review of Psychiatry 13: 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojetin, Brian A., Danny N. McIntosh, Robert A. Bridges, and Bernard Spilka. 1987. Quest: Constructive Search or Religious Conflict? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 26: 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtessis, James N., Robert Eisenberger, Michael T. Ford, Louis C. Buffardi, Kathleen A. Stewart, and Cory S. Adis. 2017. Perceived Organizational Support: A Meta-Analytic Evaluation of Organizational Support Theory. Journal of Management 43: 1854–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, Solange, Céline Béraud, and E.-Martin Meunier. 2015. Catholicisme et Cultures: Regards Croisés Québec-France. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, Frederick T. L., and Peter Zachar. 1990. An Evaluation of Allport’s Religious Orientation Scale Across One Australian and Two United States Samples. Educational and Psychological Measurement 50: 359–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Liping, Chan Li, and Dan Zhu. 2012. A New Approach to Testing Nomological Validity and Its Application to a Second-Order Measurement Model of Trust. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 13: 950–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łowicki, Paweł, and Marcin Zajenkowski. 2020. Empathy and Exposure to Credible Religious Acts during Childhood Independently Predict Religiosity. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 30: 128–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macías Ruano, Antonio José, José Ramos Pires Manso, Jaime de Pablo Valenciano, and María Esther Marruecos Rumí. 2020. The Misericórdias as Social Economy Entities in Portugal and Spain. Religions 11: 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maij, David. L. R., Frenk van Harreveld, Will Gervais, Yann Schrag, Christine Mohr, and Michiel van Elk. 2017. Mentalizing Skills Do Not Differentiate Believers from Non-Believers, but Credibility Enhancing Displays Do. Editado por Michel Botbol. PLoS ONE 12: e0182764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltby, John. 1999. The Internal Structure of a Derived, Revised, and Amended Measure of the Religious Orientation Scale: The ‘Age-Universal’ I-E Scale—12. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 27: 407–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel, Paul Christopher, and Miguel Glatzer. 2019. The state, religious institutions, and welfare delivery: The case of Portugal. In Faith-Based Organizations and Social Welfare. Edited by Paul Christopher Manuel and Miguel Glatzer. Palgrave Studies in Religion, Politics and Policy. New York: Springer Science + Business Media, pp. 103–33. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, D. Harrison, Vivek Choudhury, and Charles Kacmar. 2002. Developing and Validating Trust Measures for E-Commerce: An Integrative Typology. Information Systems Research 13: 334–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Brian K., Matthew A. Rutherford, and Robert W. Kolodinsky. 2008. Perceptions of Organizational Politics: A Meta-Analysis of Outcomes. Journal of Business and Psychology 22: 209–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, Henry. 1983. Power In and Around Organizations. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Mockabee, Stephen T., Joseph Quin Monson, and J. Tobin Grant. 2001. Measuring Religious Commitment Among Catholics and Protestants: A New Approach. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 40: 675–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniz, Jorge Botelho. 2014. Igreja Católica e Caridade em Portugal. Do múnus bíblico de ajudar o outro à sua indispensabilidade no século XXI. Revista Brasileira de História das Religiões 7: 223–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyrinck, Bart, Willy Lens, and Maarten Vansteenkiste. 2005. Goals and Regulations of Religiosity: A Motivational Analysis. In Advances in Motivation and Achievement. Amsterdam and Oxford: Elsevier JAI, vol. 14, pp. 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, Eduardo, and Carlos Cabral-Cardoso. 2017. Older Workers’ Representation and Age-Based Stereotype Threats in the Workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology 32: 254–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, N. Andrew. 2014. Empowerment Theory: Clarifying the Nature of Higher-Order Multidimensional Constructs. American Journal of Community Psychology 53: 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, Christian M., Marko Sarstedt, and Detmar W. Straub. 2012. Editor’s Comments: A Critical Look at the Use of PLS-SEM in “MIS Quarterly”. MIS Quarterly 36: iii–xiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, Christian M., Sven Wende, and Jan-Michael Becker. 2015. SmartPLS 3. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Robbins, Mandy, Leslie Francis, David McIlroy, Rachel Clarke, and Lowri Pritchard. 2010. Three Religious Orientations and Five Personality Factors: An Exploratory Study among Adults in England. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 13: 771–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, Marko, Christian M. Ringle, Donna Smith, Russell Reams, and Joseph F. Hair. 2014. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM): A Useful Tool for Family Business Researchers. Journal of Family Business Strategy 5: 105–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, Marko, Petra Wilczynski, and T. C. Melewar. 2013. Measuring Reputation in Global Markets—A Comparison of Reputation Measures’ Convergent and Criterion Validities. Journal of World Business 48: 329–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, Charles A., and Richard L. Gorsuch. 1991. Psychological Adjustment and Religiousness: The Multivariate Belief-Motivation Theory of Religiousness. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 30: 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, Charles A., and Richard L. Gorsuch. 1992. Dimensionality of religion: Belief and motivation as predictors of behavior. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 11: 244–54. [Google Scholar]

- Shafizadeh, Mohammad Ali, and Soheil As’ad. 2021. Comparative Nature of “Revelation” and Its Types from the Perspective of the Holy Quran and the Testaments. International Multidisciplinary Journal of PURE LIFE (IMJPL) 8: 13–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socha, Pawel M. 1999. Ways Religious Orientations Work: A Polish Replication of Measurement of Religious Orientations. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 9: 209–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosik, John J., Jae Uk Chun, Anthony L. Blair, and Natalie A. Fitzgerald. 2013. Possible Selves in the Lives of Transformational Faith Community Leaders. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 5: 283–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Rodney. 1999. A Theory of Revelations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 38: 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szcześniak, Małgorzata, Grażyna Bielecka, Iga Bajkowska, Anna Czaprowska, and Daria Madej. 2019. Religious/Spiritual Struggles and Life Satisfaction among Young Roman Catholics: The Mediating Role of Gratitude. Religions 10: 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, Alfredo. 2013. Anexo II—Relatório estatístico do inquérito domiciliado: “Identidades religiosas em Portugal—Representações, valores e práticas”. Didaskalia 43: 393–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, Alfredo. 2015. Reconfigurations of Portuguese Catholicism: Detraditionalization and Decompaction of Identities. In Religion and Culture in the Process of Global Change: Portuguese Perspectives. Edited by José Tolentino Mendonça, Alfredo Teixeira and Alexandre Palma. Washington, DC: The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy, pp. 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, Alfredo, ed. 2019a. Identidades Religiosas e Dinâmica Social na Área Metropolitana de Lisboa. Lisboa: Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, Alfredo, ed. 2019b. Redes de ajuda/apoio. In Identidades Religiosas e Dinâmica Social na Área Metropolitana de Lisboa. Lisboa: Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos, pp. 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Thiessen, Joel, and Sarah Wilkins-Laflamme. 2017. Becoming a Religious None: Irreligious Socialization and Disaffiliation: Becoming a religious none. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treloar, Linda L. 2002. Disability, Spiritual Beliefs and the Church: The Experiences of Adults with Disabilities and Family Members. Journal of Advanced Nursing 40: 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilaça, Helena, and Maria João Oliveira. 2019. A Religião no Espaço Público Português, 1st ed. Coleção Estudos de Religião. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Alan G., James W. Smither, and Jason DeBode. 2012. The Effects of Religiosity on Ethical Judgments. Journal of Business Ethics 106: 437–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Donald F., Everett L. Worthington, Aubrey L. Gartner, Richard L. Gorsuch, and Evalin Rhodes Hanshew. 2011. Religious Commitment and Expectations about Psychotherapy among Christian Clients. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 3: 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, Gary R., and Bradley R. Agle. 2002. Religiosity and Ethical Behavior in Organizations: A Symbolic Interactionist Perspective. The Academy of Management Review 27: 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Max. 1948. From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology. Routledge Classics in Sociology. Oxon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, Jane, and Joseph J. Martocchio. 1992. Microcomputer Playfulness: Development of a Measure with Workplace Implications. MIS Quarterly 16: 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiberg-Salzmann, Mirjam, and Ulrich Willems, eds. 2020. Religion and Biopolitics. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Willaime, Jean-Paul. 1996. Surmodernité et religion duale. In Figures des Dieux: Rites et Mouvements Religieux. Hommage à Jean Remy. Edited by Jean Remy and Liliane Voyé. Ouvertures Sociologiques. Paris: De Boeck Université. [Google Scholar]

- Willaime, Jean-Paul. 1998. Religion individualization of meaning and the social bond. In Secularization and Social Integration: Papers in Honor of Karel Dobbelaere. Edited by Rudi Laermans, Bryan R. Wilson, Jaak Billiet and Karel Dobbelaere. Sociologie Vandaag = Sociology Today 4. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 261–75. [Google Scholar]

| Construct | Indicators | Mean | Std Deviation | Std Loading | Bootstrap t-Test | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relatedness Motivation | Big events that concentrate believers | 3.764 | 1.305 | 0.856 | 107.022 | 0.000 |

| Religious ceremonies | 3.993 | 1.228 | 0.874 | 121.434 | 0.000 | |

| The activity of the Church or of religious communities | 3.783 | 1.268 | 0.857 | 109.381 | 0.000 | |

| The Pope or other publicly known religious persons | 3.890 | 1.249 | 0.868 | 126.068 | 0.000 | |

| Growth | Art and religious heritage | 3.739 | 1.361 | 0.817 | 60.145 | 0.000 |

| Motivation | Spirituality | 3.434 | 1.426 | 0.792 | 49.517 | 0.000 |

| Violence in the name of religion | 3.355 | 1.432 | 0.575 | 17.351 | 0.000 | |

| The position of the Church on ethical or moral issues. | 3.584 | 1.336 | 0.863 | 71.861 | 0.000 | |

| Christian Beliefs | God exists and made himself known in the person of Jesus Christ | 4.581 | 0.891 | 0.807 | 44.855 | 0.000 |

| The resurrection of Jesus Christ gives meaning to death | 4.265 | 1.260 | 0.718 | 29.841 | 0.000 | |

| The kingdom of God announced by Jesus Christ if the future of humanity | 3.940 | 1.551 | 0.738 | 33.330 | 0.000 | |

| Humanistic Beliefs | Science and technology prepare a better future for humanity | 4.042 | 1.401 | 0.806 | 8.895 | 0.000 |

| The future of humanity depends on our ethical and moral choices | 4.455 | 1.056 | 0.779 | 8.416 | 0.000 | |

| Democracy is the best guarantee for the future of humanity | 4.092 | 1.378 | 0.621 | 4.862 | 0.000 | |

| Perception of Support | The level of poverty would be higher without the Catholic Church | 3.833 | 1.534 | 0.645 | 18.741 | 0.000 |

| Many more elderly and sick people would be lonely without the Catholic Church | 4.313 | 1.143 | 0.703 | 22.757 | 0.000 | |

| Many would not be able to find a purpose in life without the Catholic Church | 4.132 | 1.300 | 0.743 | 28.505 | 0.000 | |

| Many would die without hope without the Catholic Church | 4.294 | 1.214 | 0.833 | 42.104 | 0.000 | |

| Perception of Politics | There would be more progress without the Catholic Church | 2.663 | 1.750 | 0.799 | 29.155 | 0.000 |

| There would be more freedom for individuals without the Catholic Church | 2.644 | 1.725 | 0.842 | 39.639 | 0.000 | |

| People would be more entrepreneurial without the Catholic Church | 2.960 | 1.814 | 0.715 | 17.560 | 0.000 | |

| There would be more religious freedom without the Catholic Church | 2.739 | 1.775 | 0.830 | 32.772 | 0.000 | |

| Religious | Mass | 4.950 | 2.295 | 0.860 | 152.442 | 0.000 |

| Commitment | Eucharist Communion | 3.192 | 2.539 | 0.877 | 166.077 | 0.000 |

| Reconciliation | 2.149 | 1.548 | 0.792 | 95.816 | 0.000 | |

| Religious | Church Socialization | 4.594 | 1.667 | 0.815 | 52.577 | 0.000 |

| Socialization | Family Socialization | 2.791 | 1.625 | 0.835 | 59.001 | 0.000 |

| Construct | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|

| Relatedness Motivation | 0.922 | 0.746 |

| Growth Motivation | 0.851 | 0.592 |

| Christian Beliefs | 0.799 | 0.571 |

| Humanistic Beliefs | 0.782 | 0.547 |

| Perception of Support | 0.823 | 0.539 |

| Perception of Politics | 0.875 | 0.637 |

| Religious Commitment | 0.881 | 0.712 |

| Religious Socialization | 0.810 | 0.680 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Relatedness Motivation | 0.864 | |||||||

| 2 Growth Motivation | 0.747 | 0.770 | ||||||

| 3 Christian Beliefs | 0.324 | 0.223 | 0.755 | |||||

| 4 Humanistic Beliefs | 0.114 | 0.108 | 0.287 | 0.740 | ||||

| 5 Perception of Support | 0.256 | 0.186 | 0.326 | 0.166 | 0.734 | |||

| 6 Perception of Politics | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.091 | 0.119 | 0.268 | 0.798 | ||

| 7 Religious Commitment | 0.330 | 0.210 | 0.258 | 0.005 | 0.172 | −0.054 | 0.844 | |

| 8 Religious Socialization | 0.142 | 0.084 | 0.112 | −0.062 | 0.062 | −0.095 | 0.355 | 0.825 |

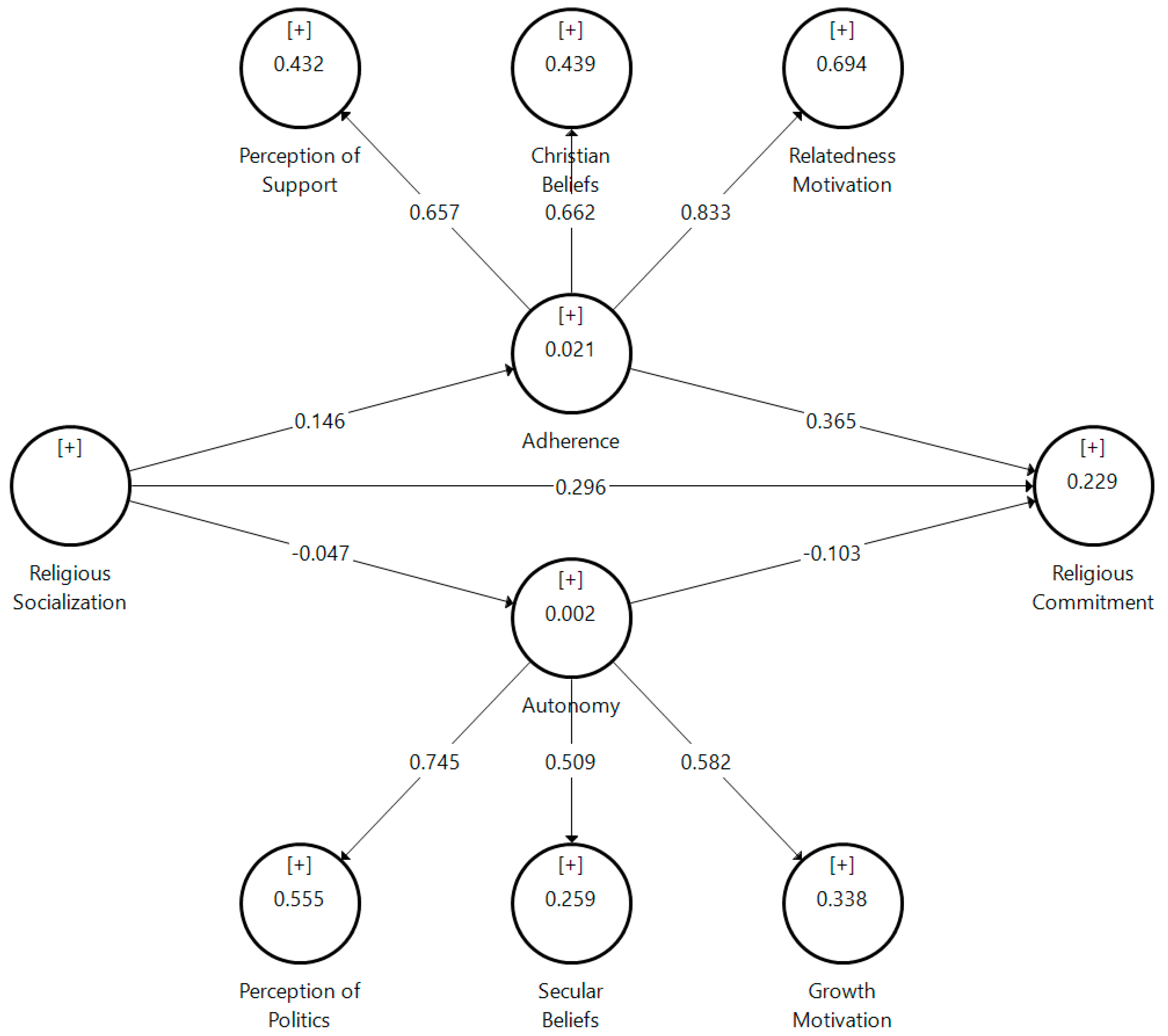

| Relationship | Β | t-Test | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adherence -> Religious Commitment | 0.367 | 18.986 | 0.000 |

| Autonomy -> Religious Commitment | −0.104 | 4.966 | 0.000 |

| Religious Socialization -> Adherence | 0.146 | 7.709 | 0.000 |

| Religious Socialization -> Autonomy | −0.047 | 1.888 | 0.059 |

| Religious Socialization -> Religious Commitment | 0.296 | 19.362 | 0.000 |

| Religious Socialization -> Adherence -> Religious Commitment | 0.054 | 7.242 | 0.000 |

| Religious Socialization -> Autonomy -> Religious Commitment | 0.005 | 1.790 | 0.074 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soares, M.E.; Teixeira, A. Understanding Personal Stances on Religion: The Relevance of Organizational Behavior Variables. Religions 2023, 14, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010063

Soares ME, Teixeira A. Understanding Personal Stances on Religion: The Relevance of Organizational Behavior Variables. Religions. 2023; 14(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010063

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoares, Maria Eduarda, and Alfredo Teixeira. 2023. "Understanding Personal Stances on Religion: The Relevance of Organizational Behavior Variables" Religions 14, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010063

APA StyleSoares, M. E., & Teixeira, A. (2023). Understanding Personal Stances on Religion: The Relevance of Organizational Behavior Variables. Religions, 14(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010063