Abstract

There are endless lists of academic publications on pilgrimage and on nonverbal communication, but very rarely if at all, do these two phenomena meet together in the same one, hence the author’s attempt to bring them together here. In this article the author discusses nonverbal communication in the context of pilgrimage rituals. Since rituals are carried out both physically and mentally, their performance requires the involvement of all the senses. A ritual may be verbal or nonverbal and very often is both. All elements of the ritual send a message. Thus, ritual communicates—it is a source of information about the individual retrieved by others—but it is not only that, as it also effects the mind, thoughts and spirituality of the individual. It has enormous influence on the well-being of a person; it is therapeutic. The author describes and analyzes single rituals related to the well, the tree, various kinds of stones, and other objects located on pilgrimage routes. While doing this, the author takes a phenomenological approach. She bases her analysis of nonverbal communication mainly on ethnographic materials. She also utilizes sources from the areas of archeology, anthropology, sociology and psychology. They are supplemented by her own participant observation at many pilgrimage places in Ireland over the period 1995–2012.

1. Introduction

There are endless lists of academic publications on pilgrimage and on nonverbal communication, but very rarely if at all these two phenomena meet together in the same one, hence my attempt to bring them together here. In this article I discuss nonverbal communication in the context of pilgrimage rituals.

A ritual can be viewed as “an ordered system of symbolic activities that is performed by either a person or a group of persons for the purpose of serving some functions” (Frobish 2004, p. 361). In other words, it is “a series of actions that are always performed in the same way, especially as part of a religious ceremony”,1 and the latter is called a rite.2 If rituals are performed, it means that they are carried out physically and mentally, and this requires the involvement of all the senses, not merely cognitive processes (Myerhoff et al. [1987] 2005, p. 7800). A ritual may be verbal or nonverbal and very often is both. It consists of such elements as body movements, gesturing, touching, eye gaze, use of space and words, as well as paralinguistic sounds; all of them send a message (cf., e.g., Birdwhistell 1952, [1970] 1990; Knapp et al. [2007] 2014). Additionally, in the case of rituals, they have a symbolic meaning (cf. Tomiccy 1975, p. 152). These activities have been defined and preserved by tradition (cf. Brzozowska 1965, p. 275), and are performed for a certain purpose.

Thus, ritual communicates—it is a source of information about the individual and culture (cf. Leach 1976) retrieved by others—but it is not only that, as it also effects the mind, thoughts and spirituality (cf. Fischer [1973] 1975, p. 161) of the individual. It has enormous influence on the well-being of a person; it is therapeutic (Logan [1980] 1992, [1981] 1994; Foley 2011, 2013), although a representative of conventional medicine could say that it works like a placebo.

Erving Goffman (1956) emphasized the functional criteria of rituals pointing to their most important social function which is to create and stabilize social relations. I would like to point to another functional aspect of rituals which is to create relations with spiritual power—no matter whether real or imagined—in order to be granted some benefits. To achieve a full picture, in this article I describe and analyze single rituals related to the well, the tree, various kinds of stones, and other objects located in the pilgrimage places. While doing this, I take a phenomenological approach. Mostly, I use the past tense while describing the rituals performed on the pilgrimage routes, either because they are not practiced any more or because I am not sure whether they are carried out, as I could not find sufficient evidence for this in the descriptions of contemporary pilgrimages.

I base my analysis of nonverbal communication in rituals on Irish pilgrimage routes mainly on ethnographic materials. Here, I draw richly from Patrick Logan’s work The Holy Wells of Ireland—a unique, detailed study of rituals at the holy wells. Many more examples of the rituals could be included here, were it not for wordcount limitations, but I have to be selective. For the same reason, I could not elaborate on many other issues.3 I also utilize sources from the areas of archeology, anthropology, sociology and psychology. They are supplemented by my own participant observation at many pilgrimage places in Ireland over the period 1995–2012.

2. Background for Irish Pilgrimage

In Ireland any part of the land—mountains, hills, lakes, islands, valleys, plains—can be a destination of the pilgrimage. In almost every lake is a holy island. The latter are also scattered around the coast, very often with the remains of early Mediaeval monastic settlements on them which are the objects of veneration. A holy well, sometimes even more than one, can be found in almost every place of pilgrimage in any kind of location, even at least expected, like the bottoms of cliffs, caves, mountain tops and passes, hills, bogs, and seashores. In the latter case, holy wells may sometimes be covered at high tide by the waters of the sea. Similarly, the wells at lakes and rivers may also be covered by their waters. The periodic union between the salt and fresh water of the wells at the sea is perceived as the symbolic union of “the Great God and Goddess”, therefore wells were associated with fecundity. “Serpent eggs” (stones) were brought to them by women who wanted to become pregnant (Brenneman and Brenneman 1995, p. 37). At the beginning of the nineteenth century, there were at least 30004 holy wells in Ireland (Plummer [1910] 1968, p. cxlix).

There are various kinds of holy wells; some of them do not match ‘common traditional image’. They may have the form of: a deep pool in a stream, a pool of water in the ground (Figure 1) or in a hollow in the stone (Figure 2) or even in a hollow of a tree stump, a waterfall, a drinking pool for cattle turned into a muddy puddle in the hot summer, “a natural basin of fresh water formed in the rock” (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 25), a lake or a part of it.

Figure 1.

Tobar Mhúire (Mary’s Well), Caher Island, Co. Mayo.

Figure 2.

St. Abbán’s grave near Ballyvourney, Co. Cork.

To the waters of the wells are assigned various healing properties, for a range of ailments, such as: whooping cough, internal complaints, sore eyes, headache, backache, earache, toothache, lameness, sprains, limbs’ and skin diseases, webbed toes, infertility, rheumatism, and mental illness. There are wells where the waters are believed to cure all kind of diseases. In most cases, the origin of the healing properties is credited to the saints who performed miracles there.5 However, there are still those whose names do not refer to any saint, which must have been known in pre-Christian times, e.g., the Rag Well, the Pin Well6 (often reputed for healing toothache), the Butter Well, the Eye Well, and Tobar na nGealt (the Well of the Lunatics) at Kilgobban (Co. Kerry). The latter was visited by people considered ‘madmen’. It was believed that they were cured after drinking the water and eating the water-cresses of the well. Another example is the Tooth Well on the Burren (Co. Clare) known for cures for toothache and arthritis. It was still visited at the end of the twentieth century. Devotees left there human teeth, bones, stones, and sometimes wild daffodil (Brenneman and Brenneman 1995, p. 7). Beside the purpose of searching for a cure, holy wells were also visited as penance. Nowadays, a new tradition has been observed, namely the visiting of wells by students before and after their exams (Keane 2015).

Visiting holy wells is mentioned in the oldest Irish literature. Some references can be found in the work of Giraldus Cambriensis (cf. Gerald of Wales [1951] 1982) written in the twelfth century. The descriptions of the first practices at holy wells come from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; some customs mentioned in them are not practiced any more. Most of the pilgrimage places are Christian, but it is highly likely that in most cases their veneration goes back to the pagan, even prehistoric times. Therefore, in the case of Irish pilgrimages we can call them “archaic pilgrimages” (Turner and Turner 1978, p. 18). Along with overtaking the pilgrimage places, also the stories and legends about their origin were Christianized. Beliefs and practices related to them can be traced back to at least the tenth century (cf. Logan [1980] 1992, p. 16). Even the Reformation or the penalty of a whipping or a fine issued by the Catholic Church were not able to stop them completely. The Church authorities were mostly opposed to the drunkenness, debauchery and faction fighting that were often a feature at the patterns (Patrons’ Days–saints’ days).

The pilgrimage movement in Ireland developed around 800. In the twelfth century, the pilgrimage to Lough7 Derg—St. Patrick’s Purgatory—(Co. Donegal) drew crowds of international pilgrims (c.f. Harbison 1991, pp. 236, 238). At present, some pilgrimages have been discontinued, some have been restored, modernized, reorganized, and their popularity revived8 (cf. McGarry 2000), while others have been flourishing continuously. According to Logan ([1980] 1992, pp. 156–57), “cheap comfortable travel and television, have led to a decline in people’s interest in their local activities” resulting in abandoning of the pilgrimage to many local wells. He also noted that the pilgrimages to famous international places like Lourdes, Fatima or Rome overshadowed local pilgrimage (cf. Pochin Mould 1955, p. 70). On the other hand “easy travel and television have made many pilgrimages better known”, also including those traditional Irish ones. This is confirmed by Derek Fanning (2022, p. 4) who “had been watching on social and traditional media, during the previous years, the steady rise in popularity of Ireland’s Pilgrim Trails and […] had now decided to hop on board the trend”.

It is difficult to say whether some pilgrimage rites, rituals, and customs are still carried out. Some pilgrims may not want to admit practicing them for various reasons, e.g., in order not to be ridiculed, other may want to keep the practice to themselves. In the 1970s, Logan ([1980] 1992, p. 15) observed the tendency “to shorten and simplify the ritual”, although he assured “in most cases details of the older practices are remembered”. It can be assumed9 that in some places some rituals are no longer practiced, while in others, they are still carried out. Recently (April 2022) I asked a local person whether the stations10 were done at St. Gobnait’s11 pilgrimage place in Ballyvourney (Co. Cork). She wrote12 me that the place is locally “held in high regard” and that she herself “did them in December” for the health of her relative.

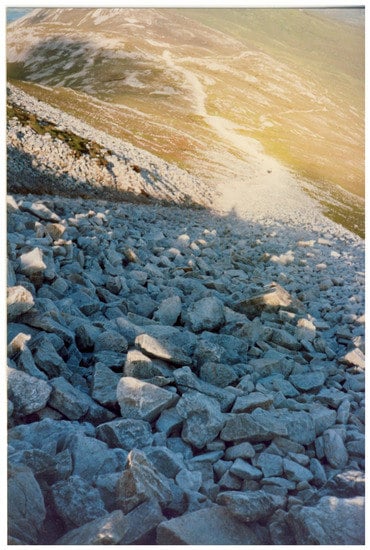

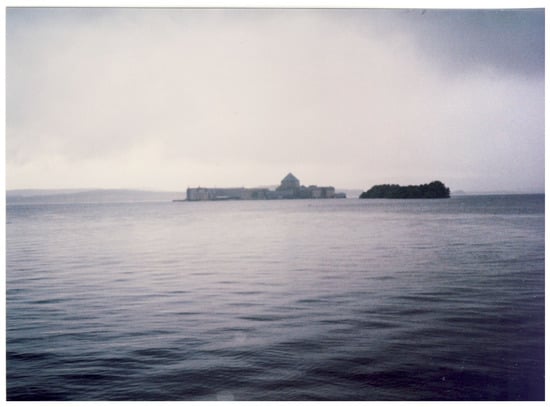

Traditionally, the pilgrims did the pilgrimage barefoot. The practice of walking barefoot, or on the hands and knees, around the well, a tree, a stone or a heap of stones while praying, can be found described by writers in the nineteenth century. Croagh Patrick (Co. Mayo) (Figure 3) was climbed “bare from the waist up, even on the coldest days” (Hughes 1991, p. 64). According to Logan ([1980] 1992, p. 16), walking barefoot was meaningful as “a pair of boots was a status symbol”. He also added that this was done in the summer. However, even today, and not only in the summer, barefoot pilgrims can be spotted. I saw a man with bare feet who had just completed the stations on Croagh Patrick in 1996. The pilgrims who come to the Station Island in Lough Derg (Co, Donegal) (Figure 4) for the three-day pilgrimage, take off their shoes as soon as they arrive there and put them on again when they are about to leave (Curtayne [1944] 1980, p. 122). Bare feet are a sign of reverence and respect for the presence of God, and for the holy place. Taking off the footwear can be also perceived as a symbol of shedding “all those externals that make up status and lend importance to the individual: house, family and dependants, atmosphere, daily occupation”. If the pilgrim is “a personage in his ordinary life, he undergoes an immense leveling and becomes just one of the crowd” (Curtayne [1944] 1980, p. 132).

Figure 3.

The most difficult part of the pilgrimage route to Croagh Patrick.

Figure 4.

The Station Island in Lough Derg.

In the past, the pilgrims usually travelled in groups. This form is continued, especially to places, like islands, where the journey has to be organized, and also where pilgrims are less experienced and the route is demanding. Depending on the difficulty and part of trail the pilgrim may “intentionally and consciously express himself13 in a particular way” (Goffman 1956, p. 3) because it is required by tradition or the specificity of the trail. The latter very often demands cooperation of the group. Some pilgrims join the group of other pilgrims simply because it may be a pleasurable experience (cf. Fanning 2022, p. 4). Being in the same group, sharing the same experience for some time leads to a more or less strong relationship, “familiarity” (Goffman 1956, pp. 50–51). However, to the easy accessible sites come many individual pilgrims who like to contemplate the place in solitude without crowds, to get away “from their daily routine [..] in order to get nearer to God” (Duffy 1980, p. 20)—to soak in the environment for spiritual benefits, but also for mundane (cf. Ray 2015, p. 424).

3. Time

The main pilgrimages take place on Pattern Days but there may also be other dates, often directly linked with pagan festivities, e.g., the Celtic festival of Lugnasad14 (cf. MacNeill [1962] 2008). Pilgrimages can be done on any day during the year, very often for a special intention, such as: seeking the healing of a certain person, or giving thanks for something. Some places require to be visited more than once, e.g., in the case of Mary’s Well and Sunday’s Well in Athnowen (Co. Cork) it had to be “three times over a period of eight days” (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 85). For special intentions or request, some pilgrims may make the rounds for twenty one or nine consecutive days. “[T]he twenty-one mornings” while fasting with empting out the well on the final morning were performed at St. Gobnait’s Well in Ballyvourney (Figure 5) (Ó hÉaluighthe 1952, p. 61). Seven, three15 and nine are mystical numbers known also in other cultures, as well as the belief that the water of some wells, streams or brooks acquires special proprieties or that they increase on a special day and at a special time, like before sunrise or between sunset and sunrise. In many cultures, including Irish culture, an example of a magical date was and still is 24 June—St. John’s Day, or more precisely the night preceding that day. The water from St. Martin’s Well at Cronelea (Co. Carlow) was taken home on St. Martin’s Day (November, 11) and drank the same night (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 118). In the water of St. Ciarán’s Well at Castlekeeran a special virtue was believed to be inherent “from midnight to midnight of the festival”, i.e., on the first Sunday of August. The most potent virtue was expected to be “at the initial midnight hour” (MacNeill [1962] 2008, p. 262). There may also be other rules and taboos.

Figure 5.

St. Gobnait’s Well, Ballyvourney.

Some pilgrimages used to start with vigils and fasting,16 as it is still observed by pilgrims during the traditional three-day Lough Derg pilgrimage.17 The pilgrims are obliged to begin fasting at midnight before coming to the Station Island. They are allowed to take water and prescribed medicine, and one ‘Lough Derg meal’ a day, i.e., dry bread or toast and black tea (with sugar), coffee or water, while on the Island. If the place is reached on the previous evening, the rounds begin shortly after daybreak. It can be assumed that at present, besides Lough Derg, starting off the pilgrimage with a vigil, is not widely practiced, if at all. For example, at the end of the twentieth century only a small number of pilgrims to Croagh18 Patrick (Co. Mayo) followed that tradition (Harbison 1991, p. 69). Vigil and fasting are an expression of withdrawal from the world and worldly matters; carried together in a group unites the pilgrims with themselves and with “suffering humanity throughout the world” (Duffy 1980, p. 12).

4. Rituals Related to the Well

The pilgrimage is performed according to tradition handed down from generation to generation. Sometimes a kind of instruction, or notice with “details of how the traditional pilgrimage should be carried out” can be found at the pilgrimage place (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 24). This information defines the place and enables the pilgrim to adjust to the requirements in order to achieve desired results. Whether the attitudes, beliefs, and emotions of the individual are “true” or “real” (cf. Goffman 1956, p. 1) is not an issue here, since, as if the individual is a true devotee s/he knows that s/he cannot cheat supernatural powers; s/he would not even think about it, as it would not make any sense to come to such a place and pretend anything.

There are many legends, stories about the profanation of the sacred place and the results of it. Therefore, it is important to know how the rituals should be performed properly. The insult may be a result of: walking anti-clockwise round the place or the object; washing dirty clothes in the well; the washing a child in the well by a Protestant considered as an enemy; washing the viscera of cattle in the well; treating animals with the well water; not covering the well after drawing the water from it (Logan [1980] 1992, pp. 48–67). Any insult of the well might have caused the loss of the healing powers of the water or even disappearance of the well or other kind of disaster. It might not be considered as an insult, but still it was “thought unwise to stir up the mud in the bottom of” Tobar na Súil (the Well of Eye) on the top of Slieve Sneacht19 in Inishowen (Co. Donegal) “because on the way back down the mountainside mist, rain or snow, may fall” (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 63).

Usually, the pilgrimage stations start with preliminary prayers like five decades of the rosary. After that while kneeling at the well the pilgrim says a few more prayers. The pilgrim may also invoke the saint over the well and “hold a conversation” with her or him (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 45). Then, the pilgrim goes round the well reciting more prayers. The usual prayers are decades of the Rosary, Hail Marys (Aves), Glorias, Our Fathers (Paters), the Creeds (Credos). Usually, they are recited by the pilgrims singly, but they also may be said in groups. The numbers of prayers and rounds vary: 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, or 15.

The rounds are made always clockwise20 (sunwise direction—Ir. deiseal), except the intention of placing a curse (to which I come back later) and the rounds of the Stations of the Cross in the new St. Patrick’s Basilica (Figure 6) on Lough Derg (cf. Pochin Mould 1955, p. 76). Sunwise direction was probably related to sun-worship (following the track of sun) replaced by Christianity with Christ—the new, true Sun (cf. Wood-Martin 1895, pp. 145–47; Pochin Mould 1955, pp. 57, 61; Streit [1977] 2001, p. 104). Further implications of deiseal led Daphne D. C. Pochin Mould (1955, p. 72) to view its meaning as: “the right way of doing […] therefore regarded as lucky”, and “the turn of blessing and the bringing of good fortune”. She also suggested that: “The walking sun-wise round […] has a practical purpose. It keeps the crowd moving, and for order, they must all move in the same direction”. Additionally, traditionally, walking barefoot often on the rough ground at night was to keep the pilgrims awake (Pochin Mould, p. 61).

Figure 6.

St. Patrick’s Basilica, Station Island, Lough Derg.

Doing rounds, or encircling has its origin in pagan belief. Making a magic circle, either symbolic or real, in order to separate sacred space from profanum was commonly practiced among Indo-European peoples. It was believed that the magical power of a closed circuit protected the inner area from the outer evil powers. It also had other symbolic meaning: “the one who circumambulates takes in the power of that which is circumambulated, and vice versa” (Brenneman and Brenneman 1995, p. 34). Drawing such a circle had to be conducted in a proper way, observing proper rituals. The most important was the movement from left to right, i.e., following the sun’s daytime travel across the sky.21

After completing a certain number of the rounds, the pilgrim drinks some water from the well using a container (a cup, a mug, a bottle), often found at the wells. At Doon Well (Co. Donegal) a set of prayers was said for every bottle of water that was taken (Ó Muirgheasa 1936, p. 156). Sometimes before drinking from the well the pilgrim performs some rituals like “throwing out three drops of water in the name of the Trinity” (Herity 1998, p. 21) at St. Columcille’s Well in Glencolumcille (Co. Donegal) (Figure 7) or lifting out water of St. Ultan’s Holy Well at Leitrim (Co. Donegal) and throwing “against the cataract” (Ó Muirgheasa 1936, p. 161). Some cups may be votive offerings left at the well after the pilgrims drank from them. The pilgrim may also dip her/his hand in the water and bless herself/himself with it or just put some of it on her/his face or bathe the affected part of the body. Taking the water internally is the Celtic custom and applying it externally is the Christian tradition (cf. Brenneman and Brenneman 1995, p. 113).

Figure 7.

St. Columcille’s Well, Glencolumcille.

Drinking water from the well was not always that easy. There is an account by Isaac Butler from 1744 in which he described the position in which the pilgrims prayed before drinking water from Our Lady Well at Mulhuddart (Co. Dublin). The well was covered with a construction forming a house. There was “a hole in each end—the people lye on their bellies there with their head over the water repeat a prayer and drink and repeat another prayer before the little glazed bauble” (in Logan [1980] 1992, p. 27). According to Logan, who visited the well in 1975, it was impossible to drink the water in the way described by Butler and he did not find anybody who could attest it.

An interesting ritual was connected with some warts wells: “it is the practice to lift a little water on the point of a pin and drop it onto the wart, and when this has been done the pin is placed in the water to rust away and it is believed that as the pin rusts away the wart will disappear” (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 119). We encounter here an interesting example of sympathetic magic where “the law of Contact or Contagion” was applied (cf. Frazer 1890). The magic persisted between the three objects (the water, the pin, and the wart) because they came in contact. The water acted as a transmitter that transmitted the disease to the pin.

The water from St. Fiachra’s Well at Ullard (Co. Kilkenny), that was used to cure rheumatic pains, had to be placed in the hollow of a stone, believed to be the imprint of St. Fiachra’s knees, and then in the hollow of a second stone being a part of an old quern, before applying to the sore body (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 87). Here, as above, sympathetic magic was believed to be at work.

Sometimes, beside drinking the water from the well, additional treatment was required; e.g., at Tobar Bhríde (Brigid’s Well) at Darragh (Co. Limerick), moss growing nearby “is gathered and boiled in milk which the patient should drink” (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 75). The moss may be used instead of drinking water if the well is dry, e.g., at St. Brigid’s Well at Ardagh (Co. Longford). Before drinking or applying externally, the water from the holy well in Aghinagh (Co. Cork) was mixed with some earth from the grave of Fr. John O’Callaghan (Logan [1980] 1992, pp. 119–20). In some cases, e.g., the holy well on Ard Oileán (High Island, Co. Galway), sleeping near the holy well was required in order to be cured of mental illness.

The water may not be drawn directly from the well, but, for instance, from a hollow stone like the one at Lassair Well in Kilronan (Co. Roscommon), known as the Holy Font of St. Ronan or the Cleansing Stone. The pilgrim washed her/his face, hands and feet with the water from that stone (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 25). Logan ([1980] 1992, p. 25) called the washing “the symbolic purification”. Pochin Mould (1955, p. 60) seemed to agree with this interpretation. She gave examples of cleansing of sins in the Old Testament and referred to water as a symbol of life. However, she also recalled the story of the blind man cured by Jesus who spread clay in his eyes and told him to wash in the pool of Siloe. This story and the fact that the contemporary pilgrims apply the water to the sore parts of their body certainly is more than “symbolic”. The pilgrims may also bless themselves with the water from a hollow in a stone, e.g., in the church at Kildoe (Co. Cavan) on which, according to one legend, St. Mogue was taken for baptism from an island to the mainland (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 103).

5. Immersion in the Water

Formerly the pilgrims practiced total immersion in the water of the well or in the water flowing from the well, often to the nearby lake or sea. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, James MacParlan (in Logan [1980] 1992, p. 26), “a hostile witness”, observed and described the last part of the pilgrimage to Malin Well (Co. Donegal): “by general ablution in the sea, male and female all frisking and playing in the water stark naked and washing off each other’s sins”. The placing of the heads of children “under a spout of water” of the well at St. Mullin’s (Co. Carlow), can also be considered as a kind of immersion. It was done in order “to protect them against some diseases”.22 Near Tobar Cronabhán (the Well of the White Tree23) at Barragh (Co. Carlow) delicate children were bathed in the granite trough near the well. Tobar na Taise (the Well of the Relic) at Kilnamona (Co. Clare) has a shape of a coffin. Children were “placed supine in it, in the hope that they would be restored to health”. Dipping or sprinkling children with the water was practiced at many other wells. Sometimes the immersion had to be done at certain times, like in the water of Tobar an Rátha Bháin (the Well of the White Fort) at Aghinagh (Co. Cork). Here, the child had to be plunged before the sun rise. If after the bathe the infant’s body was red, it was believed that the child would live, if it was pale the child would die (Logan [1980] 1992, pp. 74–75). The color—the body language sign—was crucial in predicting life or death.

Another kind of total immersion in the water involved towing a patient with mental illness around the island behind a boat—a practice still present in Co. Kerry at the beginning of the twentieth century. Luckily for the patients, that “shock therapy” was abandoned because of its ineffectiveness. Much safer for the person was to sew up in a small piece of cloth a verse from the Gospel written on paper and after the priest’s blessing to hang it around the ill person’s neck (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 74).

There were also holy wells to which people brought cattle and bathed them in the waters of those wells. This was to cure some diseases or prevent the cattle—to strengthen their immune system. It should be added that the water from the well may be channeled through various ‘wells’ or may flow in the open space near the well or run into the lake or sea so that the pilgrims do not drink the same water in which the body was cleansed or animals were bathed. An example is part of Gougan Lake (Co. Cork and Co. Kerry) enclosed and covered in, and treated as a holy well. While the pilgrims bathed in that ‘well’, cattle was driven through the lake water what was to preserve them from murrain (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 41). In the nineteenth century, on “Garlick [also called Garland] Sunday”24 people used to swim their horses in Lough Ciaran in Bohola (Co. Mayo). It was to protect them from “incidental evils during the year”. They threw spancels and halters, as well butter into the lake. Butter was to ensure that “their cows may be sufficiently productive of milk and butter” (O’Connor in: Logan [1980] 1992, pp. 130–31). Throwing butter into the lake was still practiced in 1950. The ritual of swimming cattle and horses in lakes, rivers and other water reservoirs was very common not only in Ireland, but also in other Celtic lands. In Ireland it was still performed in the middle of the twentieth century (cf. MacNeill [1962] 2008, 1988).

6. Votive Offerings

The pilgrims leave votive offerings on the ground at the well or throw them into it, although the latter seems to be practiced less frequently today. Votive offerings may also be placed on nearby stones. Among the offerings, which are personal possessions, are: coins, medals, rosaries, small crosses, statues, buttons, brooches and other jewelry, hair pins and other pins, needles, pieces of clothing, locks of hair, pipes, nails, screws, fish-hooks, pieces of broken china, scapulars, tiny flags, stones, as well as signs of modern devotion like plastic crucifixes and nylon rags (Harbison 1991, p. 210; Tradition, superstition, warts and nylon rags 2012) or notes that express visitors’ feelings, wishes (Foley 2013, p. 55). On two flat stones at Doon Well, Kilmacrennan (Co. Donegal) among the offerings were also gloves, handkerchiefs, T-shirts, stockings, scarves, sweaters, towels, pens, pencils, keys, prayer cards (Brenneman and Brenneman 1995, p. 52). Exam pens at holy wells are a quite new tradition; they are left by students after their exams as “a form of offering for good results” (Keane 2015). The personal possessions have a special meaning because they are a kind of extensions of the person;25 because most of the time they were so close and often so dear to a person they could be perceived as a part of that individual.

In the twentieth century among votive offerings was also food; special meaning was conferred to butter because it was associated with the cow-goddess giving milk. According to the belief, it had the power to increase the properties of the water, to free the power of the water. Sometimes even a butter churn or other utensils used to produce butter were thrown into the well. The same power as butter was ascribed to a pin or a brooch (cf. Brenneman and Brenneman 1995, pp. 17–18, 64).

Leaving a stone “might be thought of as a reminder to the saint that the pilgrim had done him honour by visiting his holy well, or it might be a way of saying that the pilgrim would wish to remain at the holy place” (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 100). However, according to Logan, the most probable reason was that the stones were “substitutes for gifts to the saint”, as “most people were too poor to afford a real gift” (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 100). The pebbles added to a heap of stones26 (Irish cairn) are also used to count prayers (cf. Herity 1998, p. 21); they were rarely thrown into the well. While doing the Cruach MacDara (an island in Co. Galway) pilgrimage, because of the lack of suitable small stones the pilgrims used the seed pods of the wild iris for counting rounds (Pochin Mould 1955, p. 116). The heaps of stones used to mark the places where something special happened. They were known in the ancient times and are mentioned in legends. Throwing a stone at a cairn was a Celtic tradition, and such a stone meant a wish.

A small stone may be placed also on the stone slab, like that in the precinct of the largest of the ruined churches at St. Mullins (Co. Carlow). It was still done in the nineteenth century after each of the nine rounds of the slab (O’Hanlon in Logan [1980] 1992, p. 28). The pilgrim may leave some offerings on the heap of stones,27 especially when it is considered to be the altar. Rosary beads, little devotional images and cards, buttons, the linen variety, clasps, brooches, pipe bowls, and money were left after praying in the crevices of the large rock called St. John’s Stone near Drumcullin Abbey (Co. Offaly) and on the ground around it. The pilgrims believed that their sins were left behind (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 101). Again, we encounter here sympathetic magic due to the transfer of specific human characteristics to the object.

Logan ([1980] 1992, p. 119) mentioned also “unusual votive offerings”, namely burning candles, brought to the well and left at it. The offerings were also left in or on other objects than the well, e.g., on the wall around Lassair Well (Co. Roscommon). Among them was a small box for offerings (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 25). Pins were left in the mortar joints of St. Finan’s Church at Killemlagh (Co. Kerry). Nails and pins were drown into the trunk of the tree, e.g., the ash tree over St. Bernards’s Well in Rathkeale (Co. Limerick), and into the sacred tree of Arboe (Co. Tyrone). At Clonenagh (Co. Laois) thousands of coins were hammered into the tree (Harbison 1991, p. 231). According to Evans (1942, p. 164), each pin represented a wish, and Logan ([1980] 1992, p. 119) wondered whether the nails were a reference to the Crucifixion. This is not necessarily the case, as such votives have been found in pagan sanctuaries before Christianity. It was believed that metal strengthens the power of the water. It is likely that this belief goes back to the introduction of metal and “the uncanny power that it gave to its possessors” (Pochin Mould 1955, p. 87). The pins thrown into Glenoran Well at Teemore (Co. Armagh) were not only votive offerings, but were used for foretelling the future which was read from the way the pins settled on the sandy bottom of the well (Pochin Mould 1955, p. 87).

On Omey Island (Co. Galway) is St. Fechin’s Well which shape resembles a vagina. It was still visited at the end of the twentieth century by women who wanted to become pregnant. As votive offerings they brought with them egg-shaped stones (Brenneman and Brenneman 1995, p. 14).

Leaving the votive offering means leaving the disease with which the pilgrim came, but it is also a gift to the patron of the well—it is a token of gratitude. In pagan times, when wells were “the haunts of spirits”, the devotee would not dare to approach the sacred place empty-handed and ask for cure (Wood-Martin 1895, p. 145). The value of the left objects is rather symbolic. “A dramatic and appealing gesture”, as called by Logan ([1980] 1992, p. 118), was leaving crutches or sticks, at some holy wells at large numbers (cf. Ó Muirgheasa 1936, p. 145). They could have been left before or after healing occurred. In the first case, by leaving them the pilgrim hoped to get rid of the illness; in the latter, the pilgrim did not need them anymore—they were also a proof of the cure and of the gratitude to the saint and God. At certain wells also bandages were left. Fulfilling the wish at some wells acquired additionally refraining from some activities, e.g., shaving or polishing shoes on Sunday at St. Brigid’s Well at Greaghnafarna (Co. Leitrim) (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 84).

7. Rituals Related to the Tree

A special tree (or a bush), recognized as holy, near the well plays an important role in the pilgrimage rituals. There are various kinds of trees growing at the well, like whitethorn, hawthorn, hazel, ash, oak, holly, rowan, willow, elder, alder, elm, fir and yew. Most of them feature in Celtic mythology. An interesting combination of a well and a tree is a well, formed in a hollow in the stump or the branches of the tree.

The tree is circled by the pilgrim while praying, and the votive offerings are hanged on it (Figure 8). If there was no tree or bush, brambles or even a weed or strong stalk of grass took its function (Wood-Martin 1895, p. 158). In the old days the offerings were represented by rags—scraps of clothing from the sick people seeking a cure at/from the holy place, brought by themselves or by their relatives, friends, if they were not able to do the pilgrimage themselves. Some of them were used to bathe the afflicted part of the body. It was believed that the disease was left with the rag or that it would go away when the cloth rotten. Nowadays, synthetic fibres left instead of a natural rag are problematic and question the whole meaning of the ritual, as they will not decompose long after the pilgrim is dead (Tradition, superstition, warts and nylon rags 2012). In the case of synthetic fibres, the ritual can be still perceived as “a mix of the embodied, symbolic and performative” but taking away disembodied illness by nature (cf. Foley 2013, p. 52) is a very long process and does not serve the purpose of the pilgrim. It is something like using an old form of ritual or creating a new one that is “no longer fitting” (Fischer [1973] 1975, pp. 164–66), but in this case it is not the form of the ritual, but the object used in the ritual that does not fit the purpose of the ritual.

Figure 8.

A tree with votive offerings at St. Gobnait’s Well in Ballyvourney.

At the Chink Well near Portrane (Co. Dublin), the pilgrim was able to see what was the prospect of being cured, in this case specifically of whopping cough, by observing the piece of bread that was brought as a votive offering. If it was carried away by the tide of the sea, it was a good sign. Rags or ribbons are viewed as a scapegoat, riddances of “the spiritual or bodily ailments of the suppliant” (Wood-Martin 1895, p. 158). Leaving them should be accompanied by the ritual formula: “By the intercession of the Lord, I leave my portion of illness in this place” (Wood-Martin 1895, p. 158).

Beside the rags are also ribbons, mostly white, red and blue. The red color was commonly used against evil spirits. Rosaries hanging next to the rags and ribbons are Christian additions. E. Estyn Evans (1942, p. 164) mentioned “strings of beads” tied to the holy tree, probably meaning rosaries. An interesting ritual was observed at the holy wells near Elphin and Castleragh (Co. Roscommon) in the nineteenth century. The pilgrims used to spit on the rags they hang in the trees. One of the oldest man said that “their ancestors always did it”; it was to safeguard from “the sorceries of the druids: that their cattle were preserved by it, from infections and disorders”; also “the fairies were kept in good humour by it” (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 114) and did not harm the people. As Logan noticed: “Spittle is regarded as something very personal, and renders the object very personal indeed” (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 115). Moreover, spitting in many cultures was and still is regarded as a sacred act.

It has to be mentioned that a circled tree does not have to be linked with a well; it may be an independent object designating the station. There may also be another object instead of a tree. In the centre of the island in Gougan Lake is a wooden pole, which probably is the remains of a cross that used to be “covered with votive rags, bandages, and the spancels of the cattle” (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 41), which apparently served as the tree.

8. Rituals Related to the Curing Stones

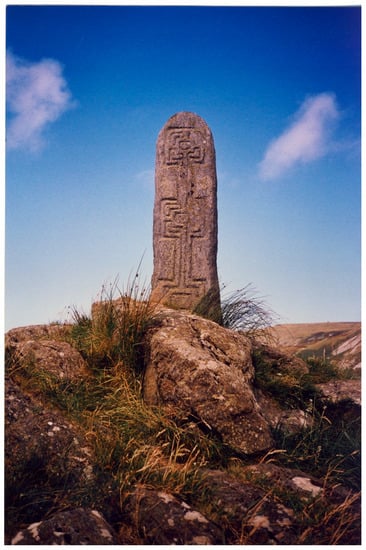

Usually there is a third element of the sacrus locus beside a well and a tree, namely a stone. This combination is very symbolic; it refers to the cosmos (Brenneman and Brenneman 1995, p. 67), to the union of male (all-father) and female (all-mother) represented by the tree-phallus (tree of life) and the life-giving water coming from the mother-earth. A female symbol was also a perforated stone (Long 1930, pp. 85–86). In the pagan Celtic world, but not only, it was believed that the stones possessed supernatural powers (cf. Ross 1970, p. 148). Stones at the well or nearby may mark the pilgrimage stations. There are different kinds of stones: rough upright pillars or carved (with various crosses or other Christian motifs, e.g., Christ, dolphins) (Figure 9); famous Celtic high crosses beautifully decorated (cf. Streit [1977] 2001); ordinary boulders, slabs. Many of them are believed to represent something, e.g., the head of St. Brigid near the old church in the parish of Outeragh (Co. Leitrim), although the examination conducted in the 1970s revealed that the face was bearded (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 22). In Clonmacnoise (Co. Offaly), there is a stone with a face carved on it which the pilgrims used to kiss. Since the place is connected with St. Ciaran, it can be assumed that the face is believed to be his. The head stones associated with the well were believed to activate “the power of the well that gives forth wisdom, fecundity, and prophecy” (Brenneman and Brenneman 1995, p. 55). The pilgrim may pray, also while kneeling, at the stones, bow to them, or walk around them while praying.

Figure 9.

An upright pillar marking Station 2 on the pilgrimage route in Glencolumcille.

A stone may also be connected with a saint if it bears some imprints,28 believed to be the marks of the saint’s: feet, hands, knees, elbows, chin, head or bottom. The saint was believed to have stood on it, rested his/her hands, elbows, chin on it, knelt on it or used it as a pillow. Some stones were blessed by the saint. The stone on the seashore near Kilrush (Co. Clare), reputedly bearing the prints of St. Senan’s knees, was revered by taking off the hat and bowing, accompanied by a prayer. Bowing and praying were also performed while walking around a large stone in the River Roe at Dungiven (Co. Derry). On Inis Cathaigh29 (Co. Clare) all stones were attributed to St. Senan and therefore bestowed with special power. Such a stone kept in a boat was believed to protect it and its crew from danger. To strengthen that power the boat was sailed “on its first voyage round the holy island” (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 101). A flagstone at Oranmore (Co. Galway), believed to bear the imprints of St. Patrick’s head and knees, was reputed for healing headache after the pilgrim, while kneeling, placed his/her head in the bigger hollow in which the saint’s head was to rest. The same ritual was carried in regard to a hollow stone at Clonmacnoise (Co. Offaly), but here the pilgrim also blessed himself/herself with the water taken from the hollow. Leac na Móna30 (the Monk’s Stone; also called the Monk’s Stone of Penance), on which St. Patrick is supposed to have left the imprint of his knees, is reputed for healing the pilgrims’ blue feet (Curtayne [1944] 1980, p. 126). The water in a large hollow in a flagstone near St. Damhnat’s Well (Co. Cavan), believed to be worn down by the saint’s knees, was used to bathe the pilgrims’ sore knees with the hope for cures. Beside St. Ciarán’s Well at Castlekeeran (Co. Meath) there is a rock believed to retain impressions of the saint’s body who sat on it. It was reputed to cure backaches or prevent them, for those who sat on it three successive times (MacNeill [1962] 2008, p. 262).

Some stones may be arranged as or have a form of a ‘chair’, a ‘bed’ or a ‘trough’. According to the form, the pilgrims would sit or lie in them in order to be cured or preserved from danger. The ‘beds’, as “symbolic of the womb of the goddess, which heals, protects, and gives birth” (Brenneman and Brenneman 1995, p. 66), are known for curing infertility; mostly women would spend the night in them. In the early nineteenth century, only those who were barren and desired children slept in St. Patrick’s Bed on Croagh Patrick (MacNeill [1962] 2008, p. 82; Logan [1980] 1992, p. 82). In Our Lady’s Bed, a cavity in a rock near the ruins of an ancient church in Lugh Gill (Co. Sligo), pregnant women used to turn thrice round while saying some prayers. It was to protect them from dying in childbirth. The same protection was believed to be gained by women who lay in St. Kevin’s Bed in Glandalough (Co. Wicklow) (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 83). Sleeping on the stone called Leabaidh Phadruig (Patrick’s Bed) on Caher Island or anywhere on that holy island was believed to cure an epileptic. Sleeping on the straw in the Teach Dorcha (Dark House), believed to be St. Barry’s grave, in the old graveyard at Kilbarry (Co. Roscommon), on the three successive nights of Thursday, Friday and Saturday, completed by attending mass in Kilbarry church on Sunday morning, was to help “disturbed people”, even if they stayed awake (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 73). Peter Harbison (1991, p. 231) refers here to the treatment of the Greek healing god Asclepius at Epidauros. Sleeping in sanctuaries of healing in hope either to receive a divine counsel or to be cured by the god was well know in the classical world (cf. Richmond [1955] 1963, p. 141).

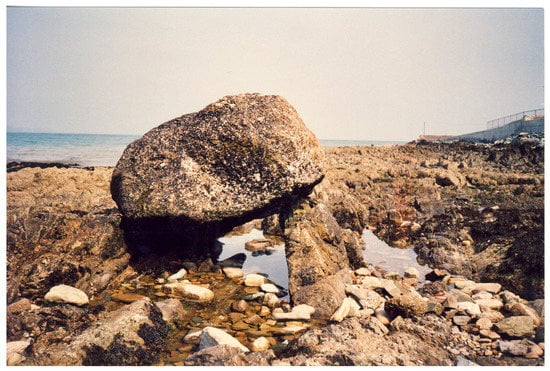

On the pilgrimage route in Glencolumcille there is a boat-shaped flagstone called Umar Ghlinne (the Trough of the Glen). Many pilgrims wash their feet with the water from it which is “reputed to have curative powers” (Herity 1998, p. 23). Lying in St. Molaise’s bed on Devinish Island (Co. Fermanagh), which is a stone trough, and reciting several Ave Marias was believed to cure a pain in the back. Similar efficacy was expected from: a large stone in the ancient cemetery in Clonmacnoise (Co. Offaly) on which the afflicted person sat; the stone near St. Columcille’s Well at Gleneaney (Co. Donegal) into which concavity the sufferer pressed his/her back; Leac na nDrom (the Stone of the Backs) on the top of Mount Brandon (Co. Kerry) against which the pilgrims pressed their backs31 (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 81). A pillar stone near St. Adamnan’s Well at Temple Moyle (Co. Donegal) was also believed to have curing power. The pilgrim rubbed the afflicted part of the body against it. The stone had already been destroyed at the beginning of the twentieth century (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 102). St. Kevin’s Stone—“a big erratic of conglomerate”—in Ardmore (Co. Waterford) (Figure 10), is raised above the ground enabling pilgrims to crawl under it. It was renowned for curing rheumatic complaints, “but it is said to be impossible to anyone in a state of mortal sin” (Pochin Mould 1955, p. 77). This may be a reference to the Bible parable about the problem of the rich man, as “It is simpler for a camel to go through a needle’s eye, than for a man of wealth to come into the kingdom of God” (Mk 10: 25).32 The treatment would also be in vain if the pilgrim had on him/her anything borrowed or stolen.

Figure 10.

St. Kevin’s Stone, Ardmore.

An interesting kind of stones are those with holes in them. One of them, a flagstone called Cloch a Phoil33 (the Holed Stone) near Tullow (Co. Carlow), was used to prevent rickets. Children were passed through the hole in it (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 105). On Inishmurray (Co. Sligo) there is a pillar stone facing east and west,

This was to ensure a safe delivery (cf. Wood-Martin 1895, p. 313; Harbison 1991, pp. 104, 228). The women, who visited Cloch na Peacaib (the Sinners Stone) at Kilquhone (Co. Cork), drew cloths through the hole in it in order to ensure lucky delivery. Cloths were passed also through a hole in a stone on Inishmore (Co. Galway) and then used to cure sore limbs. Near St. Buonia’s Well at Killabuonia (Co. Kerry), one of the two flagstones covering “the priest’s grave” has a circular hole. The pilgrim used to pass votive offerings (e.g., hairpins, buttons, shawl tassels) through it (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 32; Pochin Mould 1955, p. 79).with an ancient cross incised on the west face. Near each side of the west face there is a hole large enough to hold a thumb and on the two lateral sides the holes are large enough to take the fingers. Women nearing confinement kneel at the stone and pray for a successful delivery. They then place their thumbs in the holes in the east face and grasp the stone with their fingers in the side openings, and by this means raise themselves from their knees.(Logan [1980] 1992, p. 84)

Circling three times the holed stone at Kilmalkedar (Co. Kerry) while saying prayers was said to cure chronic rheumatism or other ills. The above rituals show that those stones were attributed with healing or preventive properties.

There is a holed pillar stone called Cloch Aonach (the Stone of the Assembly) marking Station 9 on the pilgrimage route in Glencolumcille. After circling it three times and praying, the pilgrim with outstretched arms, pressing his/her back to it, renounced the World, the Flesh and the Devil.34 According to the local tradition, “couples becoming engaged entwined their fingers through the hole of this pillar, one standing on each side, the ceremony watched by gathering people” (Herity 1998, p. 26), hence the name of the stone. This custom would match the theory about phallic symbols of pillar stones and fertility rite related to some of the holed stones (cf. Pochin Mould 1955, p. 79). It was believed that the pilgrims who were in a pure spiritual state and looked through the hole towards the south-east “should get a glimpse of Heaven” (Ó Muirgheasa 1936, p. 162; Pochin Mould 1955, p. 110; Logan [1980] 1992, p. 106).

Some holed stones were used as swearing stones.

There are portable stones that are used for curing. They may be passed deiseal round the waist, head or neck. When Michael Herity (1998) wrote on Glencolumcille there was only one rounded stone on a flat slab marking Station 3, called Áit na nGlún (the Place of the Knees), on the pilgrimage route there. Originally there were three stones which were passed around the pilgrim’s body while invoking the Holy Trinity after doing three rounds of the cairn. They were often borrowed for cures. In a little ambry in the wall above St. Columcille’s Bed inside the wall of St. Columcille’s Chapel (Station 5) were kept three stones—one with a small Latin cross incised—credited with healing powers; often sent even to America (Herity 1998, pp. 18–19). After rolling over three times in the Bed the pilgrim blessed him/herself with each stone, passed the big one round his/her waist, the second larger round his/her head and the smaller one round his/her eyes. According to the local tradition, Columcille put the last one, called Cloch na Súl (the Eye Stone), on his eyes when he wanted to sleep (Pochin Mould 1955, p. 107).

Seven rounded stones lying on a slab in an old graveyard near Drumahaire (Co. Leitrim) were applied to an injured limb. A thread tied around the nearby small peg-like stone was tied around the injured limb in case of strained tendons. If the thread was taken home to the sufferer it was replaced with a new thread. The stones were believed to be endowed with healing power after St. Patrick used them to cure his horse’s foot (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 86). Seven rounded stones applied to “sores and seats of physical pain” are also known from Co. Donegal (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 87). The “straining string”, tied around the stone in the graveyard of the old church of Killery (Co. Sligo), was “supposed to be an infallible cure for strains, pains and aches”. There were seven egg-shaped stones on it. Each of them was swung “round from left to right as on pivot […] being held between the thumb and second finger of the suppliant’s hand”, whilst certain prayers were repeated and the old string was replaced by a new one (Wood-Martin 1895, pp. 154–55).

In Aghabulloge (Co. Cork), on the top of a pillar stone called St. Olan’s Stone with ogham35 inscription rested Cappean Olan (St. Olan’s Cap)—a quartzite. It was believed to cure disease and help at childbirth and was therefore borrowed as a talisman. The pilgrim suffering of headache placed it on the head and walked three times around the nearby church (Logan [1980] 1992, pp. 78, 82; Pochin Mould 1955, p. 82l; Harbison 1991, p. 210). The similar function seemed to apply to a piece of rusty iron which was placed on the pilgrim’s head and passed from one pilgrim to the next at Gougan Lake. According to Logan ([1980] 1992, p. 42), it might have been “a relic of the local St. Barry and it was used to bless the pilgrims, just as the saint’s bell36 was used at Cruach Patrick”. Before receiving the blessing the pilgrim had to kiss the cross on the bell. After that the keeper of the bell passed the bell round the waist of the pilgrim three times (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 115; Pochin Mould 1955, p. 75).

9. Wishing Stones, Cursing Stones

Some stones, especially white or colored ones, believed to be endowed with supernatural power, were used as swearing stones, cursing stones or curing stones. They can be thought of as a kind of wishing stones. In Glencolumcille Station 6 is marked by a large earthfast erratic, called Leac na mBonn (the Flagstone of the Soles of the Feet) or Leac na hAchainí (the Stone of the Entreaty), with an inscribed simple equal-armed cross surrounded by a circle. Standing on the stone facing west the pilgrim makes three wishes (Herity 1998, p. 21). Moreover, the soil from beneath was believed to have special powers, therefore it was taken by the pilgrims (Pochin Mould 1955, p. 107). On Tory Island was a large stone called ‘the wishing stone’. Allegedly, whoever stood on it and turned three times, obtained his/her wishes (Wood-Martin 1895, p. 157). Among the wishing stones can be included a stone on St. MacDara Island “where women used to gather duileasg (a kind of seaweed) at low water, in the belief that any friend in captivity would soon get succor from the saint” (O’Flaherty 1683 in Harbison 1991, p. 97).

Curing stones were regarded as such because of the healing power attributed to them or to the water found in the hollows in them. To increase the fulfillment of the wish while performing the ritual at the well, the nearby wishing stone was turned clockwise. The cursing stones were turned anti-clockwise (Ir. tuathail) in order to bring misfortune on an enemy. At Kilmoon (Co. Clare), before the cursing stone was turned a person who performed the ritual fasted and “‘did’ certain turns ‘against the sun’”. As the result it was expected that the mouth of the enemy would be “twisted awry” (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 110). However, if the person performing the ritual was wrong and s/he would harm an innocent person, the curse was believed to fall on him/her.

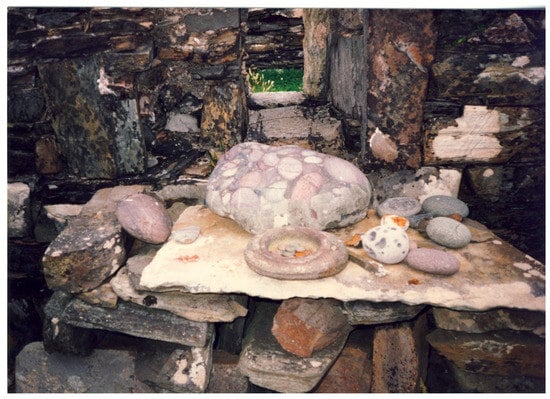

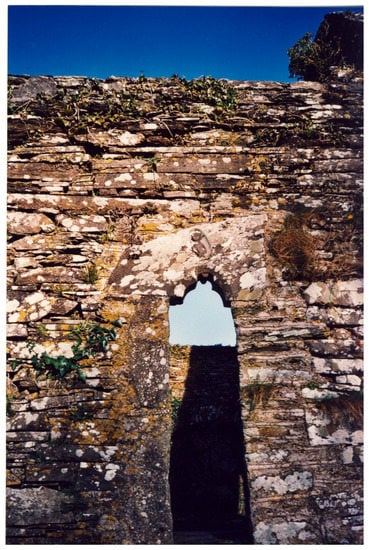

The turning of the stone was very often preceded by fasting and praying to God through the intercession of the saint at home; in the case of Caher Island (Co. Mayo) it was St. Patrick and “the saints, who had blessed the stone” (Harbison 1991, p. 228). Then, the person performing the ritual went to the Island to carry out the ritual there with the famous Leac na Naomh (the Saint’s Stone). When I was on Caher in 1996, the stone was still there on the altar of the ruined church (Figure 11), but I do not know whether the stone was still used at that time. On Inishmurray were two37 hollowed stones with smaller ones placed in the hollows used as cursing stones. The islanders preferred to call them Clocha Breacha (the Speckled Stones) as a precaution. Here, a nine-day fast was observed and then they were turned against the sun (Heraughty 1982, p. 29). They might have been turned sunwise to bless (Pochin Mould 1955, p. 75).

Figure 11.

Leac na Naomh (the Saint’s Stone) on Caher Island.

Near Blacklion (Co. Cavan), there were at least nine bullauns with one rounded stone in each of them. While conducting the cursing ritual all stones were turned.38 When Logan visited the place in the 1970s he did not record that the ritual was performed (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 108). Evans (1942, p. 166) knew about using similar stones “to work beneficent magic in the case of expectant mothers”. Although he did not write it, it seems to be obvious that in this case the stones were turned clockwise. Evans pointed to the symbolism “of the child in the womb”. The phallic symbol occurs in the case of some megalithic stone pillars against which women who wanted to have a child rubbed their bodies; the ritual practiced by Celtic people. On Tory Island (Co. Donegal) a cursing (maledictory) round “of the whole island against the sun” was practiced (Pochin Mould 1955, p. 75).

The turning of maledictive stones by druids, also called priests of pagan gods, are featured in many Irish myths and folktales.

10. Other Rituals

There are stones of various shapes with crosses inscribed in them. Pilgrims can be seen scratching other crosses on them with pebbles. This kind of ritual was performed while passing the narrow entry of the circular enclosure of so called Gobnait’s House: “the votaries must pass, absorbing the mana of the stones by rubbing” (Guest 1937, p. 376; c.f. Pochin Mould 1955, p. 98; Brenneman and Brenneman 1995, p. 58). Similar ritual (Figure 12) was witnessed by Evans (1942, p. 164) at a well near Cork.

Figure 12.

Crosses inscribed in the wall of St. Declan’s Church, Ardmore.

Near the sacred Loch a Derren39 (Co. Cork) there was “a fertility stone resorted to by girls contemplating marriage” (Guest 1937, p. 377). On the other hand, Cloch Ghobnatan (Gobnet’s Stone) in Clondrohid (Co. Cork), still venerated in the 1950s, was visited before the funeral. A coffin was carried deiseal once round the stone (Pochin Mould 1955, p. 93). The link between fertility and death is a very common cultural theme as the dead return to Mother Earth—the giver of life in the form of crops.

According to common belief, in some holy wells live sacred salmon or trout (even two or three), but rarely eel. Depending on the local belief the fish can be seen any time or at particular time. Seeing it is a lucky omen and means granting the pilgrim’s wish. However, seeing the fish in St. Columcille’s Well in Glencolumcille meant death within the year for the person who saw it, but s/he would have gone to heaven (Pochin Mould 1955, p. 108). The fish symbolizes the power of the well. It is assumed that originally the fish was “the personification of the spirit of the well” (Pochin Mould 1955, p. 90). Fish takes a prominent place in Celtic mythology. The most famous in Irish mythology is the salmon of wisdom living in the Well of Wisdom in the Other World.

There is an interesting ritual of drawing the well, performed at some wells in order to influence the weather conditions. In the cases of Tobar na Corach (the Well of Assistance) on Inishmurray (cf. Wood-Martin 1895, p. 162) and the well at Teelin Bay (Co. Donegal), it was done in order “to calm the sea or to provide a favourable wind”. Sometimes it was enough to sprinkle three drops of the water from the well three times to the four directions of the world, like it was done with the water from St. Molaise Well on Inishmurray (Pochin Mould 1955, p. 114). Logan ([1980] 1992, p. 61) supposed that the belief was that “the water of the holy well added to the sea caused storms to cease. Or it may have been thought to increase the catches of fish”. One does not exclude the other. Fishermen sailing out from Teelin Bay to fish in the open sea also used to “lower their sails by way of salute on passing Tobar na mBan Naomh,40 take off their caps, and ask the help and blessing of the holy women” (Ó Muirgheasa 1936, p. 149). These rituals were performed while passing the islands considered holy (cf. Harbison 1991, p. 96); prayers were addressed to God and an appropriate saint. According to Wood-Martin (1895, p. 163), the ceremonies attached to the wells are “the remnant of Druidical cult”, for the Druids claimed to have power to control the weather.

In relation to the wells the Teach an Allais (sweat-house) should be mentioned. These structures were used in Ireland around the seventeenth century (Harbison 1991, p. 102) and into the twentieth century; often compared in function to a Turkish bath. As the name suggests, they were used for ‘sweating out’ an illness,41 mostly rheumatism, but also in order to improve girls’ complexions. Very often a plunge into cold water running nearby completed the treatment (cf. Evans 1942, p. 83). I visited such an object on Clare Island (Co. Mayo) in 1996 and later, but nobody used it any more. It is located near Tobar Féile Bhrid (the Well of Brighid’s Feast) and is called Leaba Bhrid (Brighid’s Bed) (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

In the background, a sweat-house on Clare Island.

There may be a number of other stations at which the pilgrims pray and which they circle, like mounds (sometimes with trees on them), objects called the graves, old churches or their ruins, graveyards, altars inside of the churches, statues. The pilgrim may also kneel and pray at the entrance to the well or other object. The pilgrim may kiss some items there, like figures, or may sign those items and herself/himself with the sign of the cross (as practiced at Tobar na Mult—the Well of the Wethers at Ardfert, Co. Kerry), or may sign herself/himself with those items making the sign of the cross. Kissing the stone under the window inside the ruins of the church, where once the altar was, after putting a leaf in the window, was common during the visit at St. Moling’s Well at St. Mullins (Co. Carlow).

The pilgrimage places may also be visited because of other objects, besides those mentioned above, believed to be bestowed with healing power. An example is St. Finnian’s church at Killemlagh (Co. Kerry). Here, the fern growing on the church’s ruins was used to treat “diseases of a scrofulous nature” and other skin problems. It was sought on March, 16 (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 87). The hat of Father Moore,42 kept in the house near Father Moore’s Well on the Curragh43 of Kildare, was used as a remedy for headache. The hat was placed on the head of the sufferer. The skull held in a hole in a wall of the ruins of the church at Kilbarry (Co. Roscommon) was to help the sufferers from toothache. The “tender area” was rubbed “gently with the skull” (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 85). In Ballyvourney, Father O’Herlihy’s bone, “kept in a tin box, wrapped up in a cloth”, and some human bones preserved at St. Abbán’s grave (near Ballyvourney) were used for cures. The saint was “specially invoked for bone complaints” (Pochin Mould 1955, pp. 98, 99).

The wooden statue of St. Brendan on Inis Gluaire (Co. Mayo) taken by a person in her/his hands three times in the name of the Trinity (Father, Son and Holy Spirit) was to render her/him “the power to help a woman in labour by touching her” with the hands that hold the statue. Such a power could have been acquired also by spanning the shaft of the High Cross of Clonmacnoise (Co. Offaly). This power was transferred to a woman in labor when the person who gained it from the Cross put his/her arms around her (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 84). In Ballyvourney, an oak wooden statue dated to the thirteenth century, believed to be the image of St. Gobnait (Figure 14), used to be set up on the saint’s days in the place where the stations are still carried out. The pilgrims circled it three times on their knees and tied handkerchiefs and rags about its neck which was to prevent disease. At the end the figure was kissed and money offered to it (Richardson 1727, pp. 70–71). In the nineteenth century the pilgrims rubbed their afflicted and sore limbs on the statue. The statue was also carried “round to sick people, and, so it is said, to assist in childbirth” (Guest 1937, pp. 377, 379). At present the statue is kept in the local church and placed on the table beside the altar rails on the saint’s feast day (February, 11) and on Whit Sunday. The pilgrims kiss it, sign the cross on themselves with it and measure it with ribbons, traditionally, blue bought locally (Harbison 1991, p. 134), and rosary beads. The measuring is as follows: the ribbon is laid lengthwise, then round the neck and round the waist and finishes in rubbing along the whole statue with it. I witnessed it myself in 1999. The measured ribbon is called Tomhas Gobnatan (Gobnet’s Measure) and it is used for curing; I was told that it is good for headache. John Richardson (1727, p. 71) reported on the ritual, involving sacrificing a sheep and wrapping its skin about the sick person, conducted in order to be cured of small pox.

Figure 14.

A wooden statue believed to be the image of St. Gobnait, Ballyvourney.

Over a window of the ruined church in Ballyvourney is carved a little image of a nude female which belongs to a group called sheela-na-gigs–fertility figures (Figure 15). However, in Ballyvourney by some pilgrims called it St. Gobnait44 (Guest 1937, p. 375; cf. Harbison 1991, p. 134). Pilgrims rub it with their hands or touch with handkerchiefs and “then passing into the church by the window, the handkerchief is made with appropriate gestures to touch the votary” (Guest 1937, p. 375). Sheela-na-gig by the well at Castlewidenham (Co. Cork) was touched “for help in childbirth” (Guest 1937, p. 380). In Ballyvourney, deep in the cavity of the wall of Gobnait’s Church with sheela is placed Saint Gobnait’s Bowl (Bulla). It is of agate, described by John O’Hanlon (1875, p. 468) as “a round bowl of dark-coloured stone, polished and smooth as ivory”. The pilgrim touches it three times. Each time s/he crosses her/himself with the hand it touched the bowl in order to transfer its virtues. According to Edith M. Guest (1937, p. 376), it “has been efficacious for the cure of contusions”.

Figure 15.

Sheela-na-gig, Ballyvourney.

Near Ballyvourney is a spot, where whoever stands on it “cannot hear even the loudest thunder” (Guest 1937, p. 379). There is a part of Glencolumcille pilgrimage route called Malaigh na Cainte (the Slope of the Conversation) where the pilgrims are allowed to talk while walking down.

Because the pilgrimage places are regarded as sacred, especially those associated with the saints, clay from there, often called ‘saint’s clay’, which is attributed with special properties, is collected by pilgrims. It is believed that the house in which it is kept is protected against mice, rats or fire. The clay from St. Mogue’s Island (Co. Cavan) is known also because its other properties; it was said to keep an R.A.F. pilot safe during the war. It also was believed to guarantee that those buried in it went to heaven (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 17). St. Columcille’s clay from Gartan (Co. Donegal) was believed to help women in pangs of childbirth (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 83). Moreover, “whoever either carries or eats it will never be burned, drowned, killed by one cast, or die without a priest” (Pochin Mould 1955, p. 84). Tory Island clay was used to calm a rough sea.

Clay from some places, like the water from the holy well, was used to cure diseases and also to prevent them. The clay from St. Barry’s grave at Kilbarry (Co. Roscommon) “was especially valuable in curing bellyaches, headaches and other maladies” (Logan [1980] 1992, p. 73). The clay from St. Senan’s grave in Scaterry Island (Co. Clare) was used against garden pests (Pochin Mould 1955, p. 84). The “semblance of soil” from St. Ciarán grave in Clonmacnoise (Co. Offaly) was picked up “in order to commit it to his stomach, as a means of grace, or as a sovereign remedy against diseases of all sorts”. (Otway in Harbison 1991, p. 115). Sympathetic magic seems to be the explanation for the above customs (Evans 1942, p. 166). Harbison (1991, p. 236) suggested that “the Irish pilgrims would have learned to collect secondary relics: earth from the martyrs’ tombs and brandea (or rags) that would have come into physical contact with them” in Rome.

Giving alms to the poor, still very common in the mid of the twentieth century, may be also considered a part of pilgrimage. At Ballyvourney it was a tradition for beggars to hold out their hands for alms and for pilgrims to be generous.

11. Conclusions

We have encountered a whole range of nonverbal communication elements, starting with time and environment. Time, something so seemingly intangible, perceived differently in various cultures (Hall 1959; Ricœur 1975), is a very important part of “the communicative environment” (Knapp et al. [2007] 2014, pp. 98–99). Going on pilgrimage, especially being in the place of the pilgrimage where the pilgrims perform rituals, is a form of retreat where time is suspended. If the pilgrimage is done on the patron’s day of the place, it turns into a festival.45 Additionally, although here the religious festival may not represent the reactualization of a sacred event that took place in the mythical past, in illo tempore (cf. Eliade [1957] 1959, 1963), it is old enough and very often layered around with legends, that it seems like it is from the semi-mythical past. The mythical aura is condensed by the fact that the pilgrimage place was visited by the saint and by the ancestors of the pilgrim who with his bare feet touches the very stones on which they walked (Duffy 1988, p. 77). A spot where “nothing is heard” or where the pilgrims are allowed to talk are special features of the communicating environment. Thus, space communicates (cf. Hall 1959) through all senses and together with the performed rituals, which like symbols, release their message and fulfill their function even when its meaning may elude comprehension (cf. Eliade [1952] 1961, 1962; Streit [1977] 2001), triggers various emotions and influences actions (cf. Zimbardo and Boyd 1999) of the pilgrims and their spiritual life in a way which is unique to each individual.

Keeping vigil is important because of time and activities; it is a kind of liminal time—being a part of the pilgrimage but preceding or opening the gate to proper pilgrimage rituals. It requires body efforts in order to keep awake, often in demanding environment and weather conditions. If we add to this fasting, it is even more demanding in terms of body and mind resistance. The pilgrims derive endurance from their spiritual life what is reflected in their numerous testimonies.

On the pilgrimage routes, the time is not the only one that is suspended, the same happens with the structure of the society—the people forget about their ranks and statutes. “Astructural” symptoms of social life (cf. Duvignaud [1977] 2011, p. 33; Turner [1969] 1991) are tangible, like during festivals (cf. Gierek 2020). It is quite natural for Irish people to forget about their rank, as they do not demonstrate it even in their everyday life. I did witness it on many occasions.

There is a lot of body movements and gestures engaged while performing the rituals, what is obvious since a ritual is a series of actions and motions. The rituals are carried properly according to tradition handed down from generation to generation, however, this propriety does not introduce any tension. The rituals are performed at individual pace. The posture adopted by the pilgrims is respectful, adjusted to the ritual, i.e., if it is required, the pilgrims: kneel or walk on their knees, bow, salute the object (the well or the whole island), take off the caps, crawl under the stone, are lying or rolling in the stone ‘bed’. While praying devoutly aloud or in whisper the pilgrim’s face is focused reflecting spiritual engagement. Handed down tradition from generation to generation implies that the pilgrim knows how to behave and how to perform the rituals. There is no need to be instructed by anyone. A pilgrim who goes on a certain pilgrimage is familiar with the local customs and rituals performed there.

The most frequent movement that can be seen is circumambulating various objects. It is always done to the right, sometimes with the right hand outstretched toward the object or even touching it. Another form of circumambulating is encircling oneself with a venerated object, e.g., a stone. This ritual has a notion of a double protection (signifié) because of the movement and the object it is made with—each of them is perceived as signifiant (cf. de Saussure 1916).

There is a range of rituals conducted with water from the well. They require hand involvement, very often with the help of other objects—like various kinds of containers—allowing one to draw and drink the water—or to draw the well—or to apply it to the afflicted part of the body, also to drop or throw the water, as well as to bless the pilgrims themselves with it—to make the sign of cross on themselves. The blessing may also be made with a stone. The access to the water was not always easy and required one to be fit in order to take a complicated and uncomfortable position; uncomfortable, because a crouched position had to be assumed while entering a sweat house, not to mention enduring the heat. Less demanding, although also engaging the whole body, was bathing in the water of the well and total immersion—a common practice a century ago. These rituals may be perceived as the outer (of body) and the inner (of soul) cleansing—very real and very symbolic purification.

Getting in direct contact—by touching—with the holy object is the essence of the rituals performed in the pilgrimage places. This manifests itself in various forms. The above described rituals with water are the examples of them. Another is leaving the votive offerings—personal possessions, being in such a close contact with the owner—in, on or at the holy object, place. Particular significance, and above all function, was rendered to scraps of clothing of ill persons which were intermediaries in relieving the person of the disease. Irrespective of the meaning it is given, spitting is certainly very personal and it may seem quite a peculiar way of getting in touch.

Sitting in ‘chairs’, getting in contact with the marks in the stones believed to be the imprints left by the saint, sleeping and rolling in ‘beds’—the latter symbolizing a womb—in order to be cured is a very meaningful kind of touch. Other kinds of ‘healing touch’ are: putting ‘the saint’s hat’ on the pilgrim’s head, rubbing the afflicted part of body with ‘the saint’s skull’ or ‘bone’, crawling under boulders, rubbing so called sheela-na-gig, rubbing against pillar stones, passing clothes or children through the hole in the stone or entwining fingers through the hole. Kissing the image of the saint (be it the stone or the wooden figure), putting the thread or the string around the stone or scratching crosses with pebbles on other stones are another examples of touching.

Increasing, activating the power of water through throwing metal objects (e.g., pins, needles), head stones or butter in it, also involved touch—by bringing these items in contact with the water. Actually, simply being in the place of pilgrimage is getting in touch with it, getting in contact with special supernatural power that can be sensed there. This was what I heard very often from people visiting those places, not only Catholics, but also those calling themselves pagans. It is the essence of the pilgrimage to get in touch with the place and everything what makes it so special—both seen and unseen. Often these seen features are rendered with special properties because of the resemblance—a well in a shape of vagina, a phallic stone pillar. Resemblance was also seen in the case of the way the pins or a piece of bread, used for foretelling the future, settled on the bottom of the well.

I would say that all these forms of touch are therapeutic according to the pilgrims who perform the rituals that involve it. There are testimonies of healing from diseases. I have heard some of them myself. However, it is not the kind of therapeutic touch (TT) understood as “the knowledgeable use of innate therapeutic functions of the body […] to alleviate pain and to combat illness” and “a mode of transpersonal healing”, although it can be based on a similar assumption that “the human body is an open energy system with innate therapeutic functions” (Kunz and Krieger 2004, pp. 1–2; cf. Sayre-Adams and Wright [1995] 2001).

Other body movements and movements produced with help of body observed in Irish pilgrimage places are: stretching the body in order to touch the object located high or far away, standing and turning on the stone, turning stones clock- or anticlockwise, swinging stones, giving alms—gesture of generosity—but also taking them. In the two last cases reaching out with the hand is necessary, it has a practical function, not a symbolic meaning.

There are two more elements of nonverbal communication related to the rituals in Irish pilgrimage places mentioned in this article, namely, seeing fish in the well and the importance of color. The first one is an element of environment whereas the second may be both an element of environment: permanent—if it is related to the color of the stones (white and speckled regarded as special), and semi-permanent—related to the color of rags. However, the color of the child’s body (red or pale) after plunging it in the water of the well is a physical characteristic. The color is not only a ritual-related but also culture-related communicator (cf., e.g., Ramachandran and Hirstein 1999). Its meaning, like the meaning of other elements of the pilgrimage environment and units of motion, “arrives in context” (Birdwhistell 1952, p. 10). In the case of the rituals on Irish pilgrimage routes it is Irish culture.

A ritual is “planned and orchestrated to communicate a desired message to gain a desired response” (Frobish 2004, p. 361). A ritual certainly is a form of communication with supernatural power and involves sending and receiving nonverbal signs and signals. Even if the rituals performed on the Irish pilgrimage routes may be perceived by an outside, skeptical observer as nothing more than a mixture of sympathetic magic, old pagan beliefs and superstition, obscured with Christian beliefs, they were and still are performed with the conviction that they will bring results expected by the persons performing them, caused by supernatural power. In this context, it does no matter what contemporary pilgrims are called—for Logan ([1980] 1992, p. 19) they are tourists—as they perform the same rituals (although many are not practiced any more) with the same aim in the same places as centuries ago. Nonverbal communication is the same although the origin and meaning of some signs and movements may be sometimes blurred, e.g., circumambulation. It is enough for the pilgrim that it has been done according to tradition.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I have to admit that unifying the writing of the names of the geographical elements I found in various publications was quite a challenge for me. I am very grateful to Féilim Ó hAdhmaill, Seán Ó Cuirreáin, and Diarmuid Ó Giolláin for helping me with it. I am also indebted to Ó hAdhmaill for proofreading my article and suggesting some changes. At the same time, I want to assure that I bear sole responsibility for all remaining errors in the text.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/ritual_1?q=ritual (accessed on 26 September 2022). |

| 2 | Cf. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/rite?q=rite (accessed on 26 September 2022). |