“Mystical Spirituality” in Second Temple Period Judaism? Light from the Decorated Stone in the Magdala Synagogue

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. “Spirituality” and “Mysticism” in the Study of Religion and Ancient Judaism

What nevertheless unities all these variegated efforts that are reflected in their respective bodies of literature is the craving of their authors to bridge the gap between heaven and earth, between human beings and heavenly powers, between man and God. In most cases, moreover, is the attempt to restore the lost relationship of some ancient and originally whole past: because the Temple as the natural venue for the encounter between God and his human creatures on earth has been destroyed or polluted or usurped by a competing community; because the soul, severed from its divine origin, has been entombed in its human body; or because, after the termination of prophetical revelation, the Torah has become the only vehicle for approaching God. So, at stake in our sources—a wide range of discrete forms and implementations notwithstanding—is the attempt to get (back) to God as close as possible, to experience the living and loving God, despite the desolate situation on earth with all its shortcomings and catastrophes.

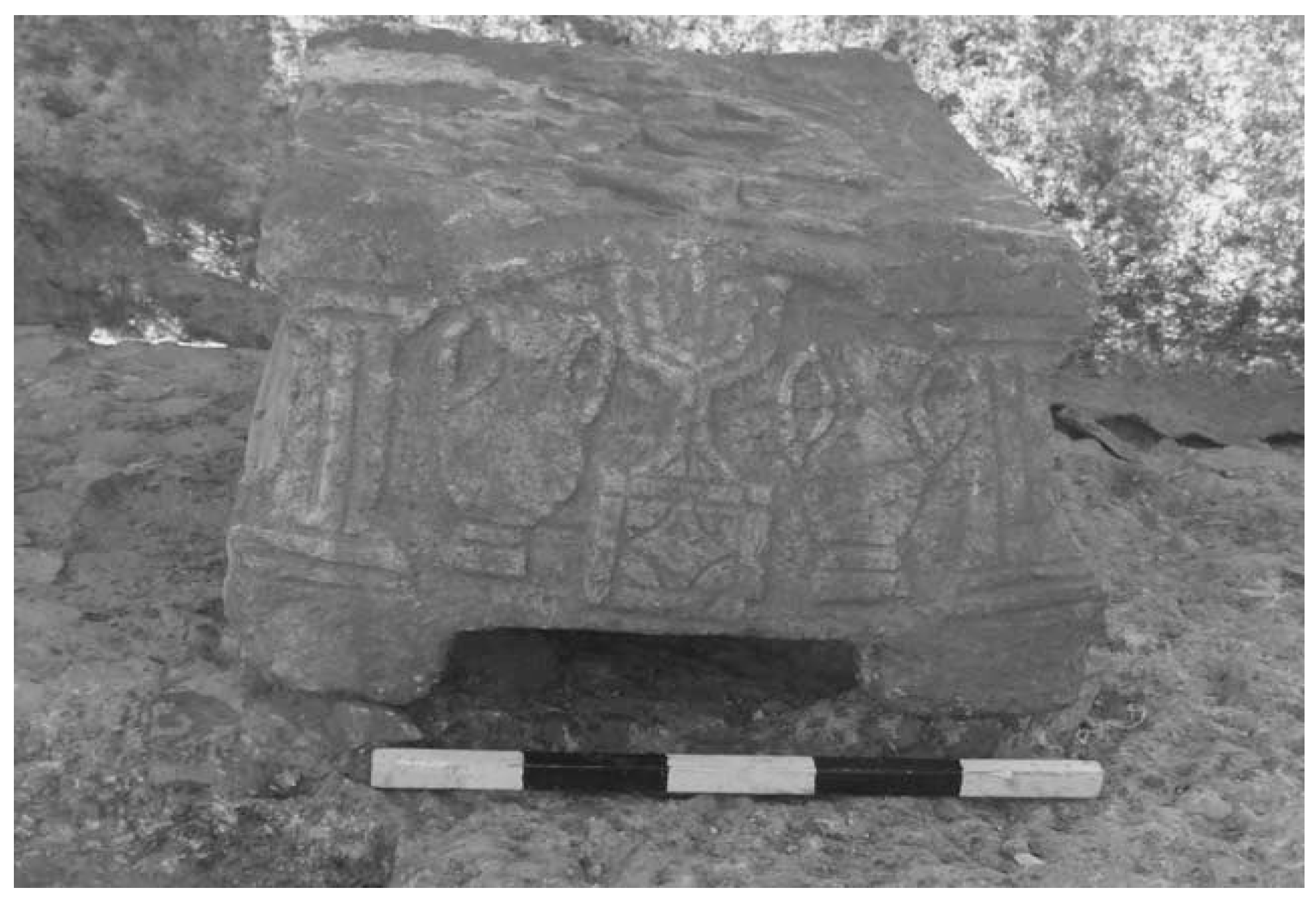

3. The Decorated Stone from the Magdala Synagogue

4. The Magdala Stone’s Merkavah Scene in Context

5. Early Jewish “Mystical Spirituality” and Jesus

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Schäfer includes the following early Jewish works under the descriptor “ascent apocalypses:” 1 Enoch 1–36 (Book of Watchers), 1 Enoch 37–71 (Parables of Enoch), Testament of Levi, 2 Enoch, Apocalypse of Abraham, Apocalypse of Isaiah, Apocalypse of Zephaniah, Apocalypse of John, and from Qumran, Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice, and the Self-Glorification Hymn. |

| 2 | The identification of this site with Josephus’s Taricheae (e.g., Ant. 14: 120; 20: 159; War 1: 180; 2: 252) has been debated. Those suggesting other sites include: (Kokkinos 2010, pp. 7–23; Taylor 2014, pp. 205–23). See the response given in De Luca and Lena (2015, pp. 280–342). While ultimately only tangential to the current study, the consensus among scholars, as De Luca shows, remains that Josephus’s Taricheae should be identified with Migdal Nuniya, or what in this study is called Magdala: a sizeable ancient city occupied from the late Hellenistic or Early Roman period (dated by coins, pottery, and wall construction) until the start of the First Jewish War against Rome in 67 CE (also dated by coins), with only minor reoccupation in the second century CE and Byzantine period. A coin dated from 5–11 CE was found in the synagogue in March 2016 (the earliest coin found prior to this was one minted in Tiberias from 29 CE), providing a terminus post quem for the building’s first phase, whether or not it was actually used as a synagogue during this phase. The numismatic evidence from the synagogue area specifically gives 63 CE as a terminus ante quem for the synagogue and the Stone, in contrast to 67 CE for the surrounding marketplace area. My thanks go to Arfan Najar for discussing with me these issues surrounding the date of the building and its immediate context. |

| 3 | For the initial press release by the IAA, see: http://www.antiquities.org.il/article_eng.aspx?sec_id=25&subj_id=240&id=1601&module_id=#as (accessed on 20 May 2021); For the preliminary report by the site excavators, see (Avshalom-Gorni and Najar 2013); online: http://www.hadashot-esi.org.il/report_detail_eng.aspx?id=2304&mag_id=120 (accessed on 20 May 2021). For reports in other news venues, see, for example: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/09/world/middleeast/magdala-stone-israel-judaism.html?hp&action=click&pgtype=Homepage&clickSource=story-heading&module=second-column-region®ion=top-news&WT.nav=top-news&_r=0 (accessed on 20 May 2021); http://www.timesofisrael.com/at-magdala-by-the-kinneret-discoveries-that-resonate-with-jews-and-christians/ (accessed on 20 May 2021); http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/12/13/is-this-stone-the-clue-to-why-jesus-was-killed.html (accessed on 20 May 2021); and http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/unearthing-world-jesus-180957515/?no-ist (accessed on 20 May 2021) (which includes an interview of Rina Talgam); and (Aviam 2013b, pp. 205–20). |

| 4 | (Aviam 2013a, pp. 159–69; Aviam 2013b; Aviam 2014, pp. 132–42 (each of Aviam’s publications basically repeats the same information and interpretation); Bauckham 2015, pp. 113–35; Binder 2014, pp. 17–48; Charlesworth 2013, pp. 173–217 (at 190); and Notley 2014, pp. 141–57 (esp. 151–57); Hachlili 2013, pp. 40–41). |

| 5 | |

| 6 | However, in 2017, distinguished scholar of ancient Jewish art and archaeology, Steven Fine, published his tentative interpretation of the Magdala Stonestone, including also an assessment of the contemporary religious and media contexts of its discovery and reporting (see Fine 2017). |

| 7 | Archaeologists and interpreters have all recognized that the most important—and clearly visible—decoration on the Stone is the seven-branched menorah. This particular menorah is fascinating not only because it represents one of the earliest depictions of the temple vessel in general, but also because it is the earliest example of a menorah found specifically within a synagogue setting. Relevant to the current study is L.Y. Rahmani’s statement that, “Representations of menorot from before 70 CE … must be associated with the Temple priesthood, for whom the seven-branched menorah seems to have been an emblem” (Rahmani 1994, p. 51). The close connection of menoroth to priesthood is supported by our few but very important material sources: a Mattathias Antigonus coin from ca. 40–37 BCE, on which Mattathias is identified as “high priest and king,” has a menorah stamped on one side (see Meshorer 1982, pp. 87–94 and plate 54; Hachlili 2001, pp. 41–42); a menorah incised on a plaster fragment from the late Second Temple period was found on a wall in the priestly housing complex in Jerusalem’s Herodian Quarter (see Avigad 1989, pp. 46–47); and a fragment of a stone sundial etched with a seven-branched menorah was found among pre-70 remains during excavations on the Temple Mount. |

| 8 | See (Aviam 2013b, p. 209). The excavators have now changed their opinions and agree with Aviam’s analysis. Aviam diverges from the excavators’ original comments in a number of places. For example, the inside of the arches on the arcades of both side panels are another row of arches rather than sheaves of corn, the hanging circular objects within the first arch of each side panel is an incense vessel rather than a Herodian oil lamp, and the two images flanking the rosette on the Stone’s face are incense shovels rather than palms (pp. 212, 214–15). The interpretation of these elements is not significant for my overall argument in this study. |

| 9 | See 1 Kgs 6: 23–28; 7: 23–37; 8: 6–8; 2 Chron 3: 10–13; 4: 3–4. |

| 10 | See Reynolds (2008, pp. 42–43) on critical issues regarding the relationship of 1 En. 37–69 and 70–71. |

| 11 | See (Klawans 2006, p. 136; Newsom 1985, pp. 51–58). The book of Ezekiel was clearly an important text at Qumran, as not only the influence of Ezekiel’s Merkavah on 4qShirShabb suggests but also in the explicit and thorough reworking of Ezekiel’s vision in five copies of 4qPseudo-Ezekiel (4Q385 [4QpsEzeka], 4Q385c [4QpsEzekc], 4Q386 [4QpsEzekb], 4Q388 [4QpsEzekd], 4Q391 [4QpsEzeke]). Scroll information is from DSSSE. |

| 12 | Elior’s work shares some similarity here; however, she does not treat the book of Daniel. The great influence of Ezekiel’s vision is also seen in that it went on to have a major impact within later Jewish and Christian art and biblical interpretation. See, e.g., the essays in Joyce and Mein (2011). |

| 13 | T. Levi 5:1 (cf. ALD 4:6 [4qLevib i 2]) reads: καὶ ἤνοιξέ μοι ὁ ἄγγελος τὰς πύλας τοῦ οὐρανοῦ· καὶ εἶδον τὸν ναὸν τὸν ἅγιον, καὶ ἐπὶ θρόνου δόξης τὸν ὕψιστον (“Additionally, the angel opened to me the gates of heaven, and I saw the holy sanctuary and the Most High upon a throne of glory”). Note, however, that God’s throne is not described as a chariot having wheels. |

| 14 | |

| 15 | Note that the “wheels” of 1 En. 61: 10 and 71: 7—the “Ophannin”—are an angelic category here, alongside Seraphin and Cherubin. |

| 16 | (Fletcher-Louis 2007, pp. 57–79 (here 58–59)). This is an idea that Fletcher-Louis has developed in a number of his publications. For support of the notion of an eschatological Yom Kippur with similar accompanying priestly figures in ancient Judaism, see Orlov (2011, pp. 27–46). One of the earliest and clearest examples of a priestly interpretation of the Danielic son of man comes from Rev. 1: 13–16, where John the Seer presents Jesus as the son of man clothed in a “long robe” (ποδήρης), a characteristic feature of the high priest’s clothing (see Exod 25: 7; 28: 4, 31; 29: 5; 35: 9; Zech 3: 4; Wis 18: 24; Sir 46: 8; Ep. Arist. 96). See also (Reynolds 2008, pp. 82, 85; Halperin 1988, p. 526 n. (a)). |

| 17 | This observation appears to be why Bauckham sees the Stone and its symbolism as thoroughly embedded within “common Judaism” (Bauckham 2015, p. 131) rather than representative of any particular Jewish group. |

| 18 | Freyne (1980). The bibliography on Galilee research is too large to list here. For surveys, see Freyne (2007, pp. 13–29; Deines 2008, pp. 271–320; Fiensey and Strange 2014–2015). |

| 19 | For a full analysis of John 6: 22–71 from the cultural perspective of the Magdala synagogue stone, see (Cirafesi, forthcoming). On the notion that John 6: 59 is a reference to Capernaum’s public “synagogue” understood as both a building and a formal institution, see Cirafesi (2021). |

References

- Aviam, Mordechai. 2013a. The Book of Enoch and the Galilean Archaeology and Landscape. In The Parables of Enoch: A Paradigm Shift. Edited by Darrell L. Bock and James H. Charlesworth. Jewish and Christian Texts 11. London: T&T Clark, pp. 159–69. [Google Scholar]

- Aviam, Mordechai. 2013b. The Decorated Stone from the Synagogue at Migdal: A Holistic Interpretation and a Glimpse into the Life of Galilean Jews at the Time of Jesus. NovT 55: 205–20. [Google Scholar]

- Aviam, Mordechai. 2014. Reverence for Jerusalem and for the Temple in Galilean Society. In Jesus and Temple: Textual and Archaeological Explorations. Edited by James H. Charlesworth. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, pp. 132–42. [Google Scholar]

- Avigad, Nahman. 1989. The Herodian Quarter in Jerusalem: Wohl Archaeological Museum. Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Avshalom-Gorni, Dina, and Arfan Najar. 2013. Migdal: Preliminary Report. Hadashot 125. Available online: http://www.hadashot-esi.org.il/report_detail_eng.aspx?id=2304&mag_id=120 (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Alexander, Philip. 2006. The Mystical Texts. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Bauckham, Richard. 2015. Further Thoughts on the Migdal Synagogue Stone. NovT 57: 113–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, Courtney. 2010. The New Metaphysicals: Spirituality and the American Religious Imagination. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, Donald D. 2014. The Mystery of the Magdala Stone. In A City Set on a Hill: Essays in Honor of James F. Strange. Edited by Daniel A. Warner and Donald D. Binder. Mountain Home: Borderstone Press, pp. 17–48. [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth, J. H. 2013. Did Jesus Know the Traditions in the Parables of Enoch? In The Parables of Enoch: A Paradigm Shift. Edited by Darrell L. Bock and James H. Charlesworth. Jewish and Christian Texts 11. London: T&T Clark, pp. 173–217. [Google Scholar]

- Cirafesi, Wally V. 2021. A First-Century Synagogue in Capernaum? Issues of Historical Method in the Interpretation of the Archaeological and Literary Data. Judaïsme Ancien–Ancient Judaism 9: 7–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirafesi, Wally V. Forthcoming. The Magdala Synagogue and Its Decorated Stone: Judean Connections with Jesus’s Galilean Mission in the Gospel of John. In Archaeology, John, and Jesus. Edited by Paul N. Anderson. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

- De Luca, Stefano, and Anna Lena. 2015. Magdala/Tarichaea. In Galilee in the Late Second Temple and Mishnaic Periods. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, pp. 280–342. [Google Scholar]

- Deines, Roland. 2008. Galiläa und Jesus: Anfragen zur Funktion der Herkunftsbezeichnung‚ Galiläa‘ in der neueren Jesusforschung. In Jesus und die Archäologie Galiläas. Edited by Carsten Claußen and Jörg Frey. BThSt 87. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Doering, Lutz. 2020. The Synagogue at Magdala: Between Localized Practice and Reference to the Temple. In Synagogues in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods: Archaeological Finds, New Methods, New Theories. Edited by Lutz Doering and Andrew R. Krause. Ioudaioi 11. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 127–53. [Google Scholar]

- Elior, Rachel. 2005. The Three Temples: On the Emergence of Jewish Mysticism. Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. [Google Scholar]

- Ellens, J. Harold. 2010. The Son of Man in the Gospel of John. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fiensey, D. A., and J. R. Strange, eds. 2014–2015. Galilee in the Late Second Temple and Mishnaic Periods. 2 vols. Minneapolis: Fortress. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Steven. 2017. From Synagogue Furnishing to Media Event: The Magdala Ashlar. Ars Judaica 12: 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher-Louis, Crispin. 2007. Jesus as the High Priestly Messiah: Part 2. JSHJ 5: 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freyne, Sean. 1980. Galilee from Alexander the Great to Hadrian: A Study of Second Temple Judaism. Wilmington: Glazier. [Google Scholar]

- Freyne, Sean. 2007. S. Galilean Studies: Old Issues and New Questions. In Religion, Ethnicity, and Identity in Ancient Galilee: A Region in Transition. Edited by Jürgen Zangenberg, Harold W. Attridge and Dale B. Martin. WUNT 210. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenwald, Ithamar. 2014. Apocalyptic and Merkavah Mysticism, 2nd rev. ed. Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity 90. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hachlili, Rachel. 2001. The Menorah, the Ancient Seven-Armed Candelabrum: Origin, Function and Significance. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hachlili, Rachel. 2013. Ancient Synagogues—Archaeology and Art: New Discoveries and Current Research. HdO 105. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin, David. 1988. The Faces of the Chariot: Early Jewish Responses to Ezekiel’s Vision. TSAJ 16. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck). [Google Scholar]

- Idel, Moshe. 2000. Messianic Mystics. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Rufus M. 1909. Studies in Mystical Religion. London: Macmillan & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, Paul, and Andrew Mein, eds. 2011. After Ezekiel: Essays on the Reception of a Difficult Prophet. London: Contiuum. [Google Scholar]

- Klawans, Jonathan. 2006. Purity, Sacrifice, and the Temple: Symbolism and Supersessionism in the Study of Ancient Judaism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinos, Nikos. 2010. The Location of Tarichaea: North or South of Tiberias? Palestine Exploration Quarterly 142: 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshorer, Yaʿaḳov. 1982. Ancient Jewish Coinage. Vol 1: Persian Period through Hasmoneans. New York: Amphora Books. [Google Scholar]

- Newsom, Carol. 1985. Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice: A Critical Edition. Harvard Semitic Studies 27. Atlanta: Scholars Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Judith. 2020. Contextualizing the Magdala Synagogue Stone in Its Place. In Synagogues in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods: Archaeological Finds, New Methods, New Theories. Edited by Lutz Doering and Andrew R. Krause. Ioudaioi 11. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 155–73. [Google Scholar]

- Notley, R. Steven. 2014. Genesis Rabbah 98,17—‘And Why Is It Called Gennosar?’ Recent Discoveries at Magdala and Jewish Life on the Plain of Gennosar in the Early Roman Period. In Talmuda de-Eretz Israel: Archaeology and the Rabbis in Late Antique Palestine. Edited by S. Fine and A. Koller. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 141–57. [Google Scholar]

- Orlov, Andrei. 2011. Dark Mirrors: Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Orlov, Andrei. 2017. Yahoel and Metatron: Aural Apocalypticism and the Origins of the Early Jewish Mysticism. Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism 169. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmani, Levi Y. 1994. A Catalogue of Jewish Ossuaries in the Collections of the State of Israel. Jerusalem: IAA/Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, Benjamin. 2008. The Apocalyptic Son of Man in the Gospel of John. WUNT 2.249. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, Benjamin. 2020. John among the Apocalypses: Jewish Apocalyptic Tradition and the “Apocalyptic” Gospel. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Runesson, Anders. 2015. Placing Paul: Institutional Structures and Theological Strategy in the World of the Early Christ-Believers. SEÅ 80: 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Runesson, Anders. 2017. Synagogues without Rabbis or Christians? Ancient Institutions beyond Normative Discourses. Journal of Beliefs and Values 38: 159–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Jordan. 2017. The Synagogue in the Aims of Jesus. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer, Peter. 1992. The Hidden and Manifest God: Some Major Themes in Early Jewish Mysticism. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer, Peter. 2009. The Origins of Jewish Mysticism. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Scholem, Gershom. 1954. Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. New York: Schocken Books. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Joan. 2014. Missing Magdala and the Name of Mary ‘Magdalene’. Palestine Exploration Quarterly 146: 205–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wach, Joachim. 2019. Sociology of Religion. London: Routledge. First published 1947. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cirafesi, W.V. “Mystical Spirituality” in Second Temple Period Judaism? Light from the Decorated Stone in the Magdala Synagogue. Religions 2022, 13, 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13121218

Cirafesi WV. “Mystical Spirituality” in Second Temple Period Judaism? Light from the Decorated Stone in the Magdala Synagogue. Religions. 2022; 13(12):1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13121218

Chicago/Turabian StyleCirafesi, Wally V. 2022. "“Mystical Spirituality” in Second Temple Period Judaism? Light from the Decorated Stone in the Magdala Synagogue" Religions 13, no. 12: 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13121218

APA StyleCirafesi, W. V. (2022). “Mystical Spirituality” in Second Temple Period Judaism? Light from the Decorated Stone in the Magdala Synagogue. Religions, 13(12), 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13121218