Abstract

Integration of religion in community health and wellbeing interventions is important for achieving a good life among faith-based populations. In countries hosting Muslim-minorities, however, relatively little is reported in academic literature on processes of faith integration in the development and delivery of interventions. We undertook a review of peer reviewed literature on health and wellbeing interventions with Muslim-minorities, with specific interest on how Islamic principles were incorporated. Major databases were systematically searched and PRISMA guidelines applied in the selection of eligible studies. Twenty-one journal articles met the inclusion criteria. These were coded and analyzed thematically. Study characteristics and themes of religiosity are reported in this review, including the religious tailoring of interventions, content co-creation and delivery design based on the teachings from the Quran and Sunnah, and applicability of intervention structures. We reviewed the philosophical and structural elements echoing the Quran and Islamic principles in the intervention content reported. However, most studies identified that the needs of Muslim communities were often overlooked or compromised. This may be due to levels of religio-cultural knowledge of persons facilitating community health and wellbeing interventions. Our review emphasizes the importance of intellectual apparatus when working in diverse communities, effective communication-strategies, and community consultations when designing interventions with Muslim-minority communities.

Keywords:

Muslim; Islam; minority; mosque; religion; community health; social work; social welfare; health promotion; welfare; wellbeing; intervention 1. Introduction

People of diverse religious, ethnic or cultural groups have different experiences than the dominant culture as they relate to service access, quality of services and wellbeing outcomes (Jongen et al. 2017; Meyer et al. 2017; Minas et al. 2013). However, public health approaches that are generalist in nature may not reach or have little effect on changing behaviours or improving the lives of culturally diverse, religious minorities (Bosire et al. 2021; Jepson et al. 2010). In faith-based populations, integration of religiosity is critical to ensure engagement, and the effectiveness of community health and wellbeing interventions targeted at these groups (Bosire et al. 2021; Hassan et al. 2021).

In Muslim families and communities, connection to religion is important, but the complexities of multicultural relations can present challenges for health and welfare providers, and for Muslim-minorities (Amri and Bemak 2013; McLaren and Patil 2016; McLaren and Qonita 2020; Patil and McLaren 2019; Salma and Salami 2020). Several authors have attempted to unpack this complexity and its associations with lived experiences, such as of isolation and loneliness (Nagle 2016; Parati 2017), mental and physical ill-health (Koerner and Pillay 2020; McCoy et al. 2016), and with general wellbeing or quality of life (Colic-Peisker 2009; Gardner et al. 2014). Specific to Muslim-minority populations, there is a strong case for religiously tailored mosque-based or discrete Muslim community health and wellbeing interventions (Khan and Ahmad 2014). This is based on known associations between religiosity and positive affect experienced by individuals.

Complementary health therapies involving spirituality-based interventions are known to have associations with coping in illness and disease (Powers-James et al. 2020; Rossato et al. 2021), including mental ill-health (Koenig et al. 2021). Religious practices that include reciting the Quran, praying, fasting, and forms of Islamic meditation (dhikr) have been shown to relieve stress, improve health, increase productivity, and enhance quality of life (Al Haq et al. 2016; Munsoor and Munsoor 2017). An interesting study by Al-Rumayyan et al. (2020) exemplified Quran recitation as the most preferred type of complementary medicine among Muslims. Illueca and Doolittle (2020) reported that praying was an effective supplementary intervention for religious patients who experienced surgical pain. Likewise, Kongsuwan and Chatchawet (2019) showed that integrating Islamic intervention in pain management during birth for primiparous Muslims proved effective. In palliative care, Duman et al. (2021) conducted a study to determine the relationship between religious attitudes and psychological adjustment to cancer in Muslim women. This study revealed that religious attitudes reduced the women’s levels of helplessness, hopelessness, and anxiety.

Researchers have recommended for health care providers to recognize and advocate for the spiritual needs of patients as an integral part of care management. This is because religiosity has a significant impact on physical and psychological health, and social relations, and is one of the predictors of hope and life satisfaction in those experiencing ill-health (Rambod et al. 2020; Sena Lomba Vasconcelos et al. 2020). As well, improving connection with God among patients from faith-based groups enhances behavioral adaptation required for health management, intensifies courage, optimism, self-control, reduces fear, anxiety, sorrow, and despair (Asadzandi 2017, 2020; Rambod et al. 2019). If social, emotional, and spiritual wellbeing has correlations with coping during ill-being (Pasyar et al. 2020; Sohail et al. 2020), then it is a worthwhile and important to include religiosity as complementary therapeutic approaches.

Islamic health beliefs and behaviors are incontestably constructed from the Quran, the Hadith (statements of the Prophet), Sunnah (actions of the Prophet), and the thoughts of early scholars based on their interpretation of the Quran, Hadith, and Sunnah (Koenig and Shohaib 2014). The Quran, Hadith and Sunnah explain the concepts of health and detail how Muslims should maintain their health, whether it be in the form of orders or prohibitions (Novita et al. 2021). The Quran’s main function is as Al-Huda (the guidance for mankind), Al-Furqan (the separator between right and wrong) which is stated in Al Baqarah verse 185; and As-Shifa (cure of illness) in Al-Isra verse 82. The Quran contains several verses that focus on health, disease, and healing. Basil (2016) identifies from a total of 6236 verses in the Quran, 28 of which are specific to health and wellbeing. For example, the virtue of maintaining personal hygiene is listed in Al-Maidah verse 6 or At-Taubah verse 108; maintaining a healthy diet and eating nutritious foods (in Al-A’raf verse 31, Al-Baqarah verse 57); and practicing a regular sleep pattern (Al-Furqan verse 47).

Sunnah in more detail explains the procedures for looking after one’s health and wellbeing in the ways of the Prophet. For example, eating in moderation, filling the stomach with the composition of a third for food, a third for drinks, and a third for air. In addition to orders, the Quran also contains prohibitions, such as prohibiting alcohol, drugs, and gambling (Al-Maidah verse 90). Apart from maintaining physical health, the Quran also guides Muslims on how to preserve their mental health, how to deal with stress as is described in Al-Baqarah verse 185–186, and the strict prohibition of suicide (An-Nisa verse 29). As Hadith says, Allah created a cure for every disease, except for one disease, aging (Koenig and Shohaib 2014). Accordingly, the role of the Quran, Hadith and Sunnah in Muslims’ health beliefs and behaviors cannot be ruled out because both encompass many ideological and philosophical principles related to how Muslims live healthy lives. A healthy Muslim will be able to worship God to the fullest because the purpose of human life is to worship God (Adh-Dhariyat, verse 56). From the Islamic viewpoint, health is viewed as the utmost blessing from God, and every aspect of a Muslims’ life is to preserve their health as an act of worship.

Islam teaches Muslims to maintain a balance between humans’ obedience to God and the good-natured relationships between humans. Social support from Islamic communities and religious scholars holds a significant weight in Muslims’ health behavior constructs, specifically in conservative societies where religion interconnects with the political, economic, and cultural spheres (Cohen-Dar and Obeid 2017). Existing research recognizes the critical role played by social support, influencing health in Muslim communities. A recent study conducted by Hashemi et al. (2020) examining the association between social support and well-being among Muslims in Australia revealed that Muslim minorities have strong social ties to the community; social ties are found to be the mediator in the relationship between religious identity, and health and well-being. In the United States, Hardan-Khalil (2020) similarly showed that family, friends, and significant others in their Muslim communities were the main sources for support in shaping people’s healthy behaviors.

A sense of belonging and connectedness with a religious group, involvement in religious activities, or association with a religious institution, such as a mosque, provides individuals with a sense of importance, positive emotions, self-esteem, positive relationships, meaning, and purpose in life (Hardan-Khalil 2020). Integrating respect for religiosity in health, wellbeing and social care is important for engaging individuals and increasing effectiveness of medical, health or social interventions. This is because patients or participants may perceive them as culturally relevant and religiously safe.

An initial scope of research on Muslim and/or mosque-based interventions in health, wellbeing or social care were predominantly focused on Islamic countries or otherwise where Muslims were majority. To inform our participatory engagement and research with a Muslim community in Australia, we undertook a systematic review of interventions in English language literature. Our interest was in Mosque-based and/or targeted health, wellbeing or social interventions with Muslim-minority populations.

2. Methods

The PRISMA guidelines were used for this review (Page et al. 2021). In conjunction, we used PICo (Population, Interest, Context) to structure our review question:

What are the characteristics of mosque- and/or Muslim faith-based community welfare interventions in countries with Muslim minority populations?

An integrative review was chosen with consideration of methodological heterogeneity in our field of study, thereby including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research. The explicit, systematic methods developed by Whittemore and Knafl (2005) were applied: first, a search strategy was developed and implemented in the electronic databases for searching relevant articles, and involved a manual search; second, the PRISMA Flow Diagram was used to document identification, screening and selection of eligible articles based on inclusion and exclusion criteria (Page et al. 2021); third, data were evaluated to assess the risk of bias in the selected articles. Lastly, the synthesized data were analyzed and presented according to themes. Covidence software was used to store, manage, organize and extract the data from eligible studies.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they were peer-reviewed quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods, featuring community health and wellbeing interventions in countries with Muslim-minority populations. All types of studies were included to enable reporting of the characteristics of the interventions. Review articles not considerate of religiosity, specifically Muslim perspectives in the design or delivery of interventions, were excluded.

Our initial intention was to review studies of only mosque-based social work and welfare interventions; however, insufficient empirical studies were identified. We expanded our search criteria to include health promotion and wellbeing initiatives. We included studies focused on mosque-based programs, targeted interventions with Muslim communities, and general interventions where reporting on a subsample of Muslims.

2.2. Search Strategy

Electronic journal databases and the Google Scholar search engine were systematically searched. Databases were Informit, ProQuest, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Web of Science. The initial database search commenced in May 2020, was updated in April 2021, and was followed by hand searching and Google Scholar tracking in May 2021. Searching used an inclusive search string which was piloted by the researchers and reviewed by a librarian.

Two authors completed database searches using keyword search syntax according to the requirements of each database. This was built around terminologies such as ‘Muslim’, ‘Islam’, ‘mosque’, ‘intervention’, ‘wellbeing’, ‘health’, ‘welfare’, ‘social work’ ‘psychosocial’, ‘lifestyle’, ‘family’, ‘community’ and types interventions based on likely social phenomena (Table S1. Databases and Search Syntax). Search results were limited to English language articles. To ensure focus on peer-reviewed academic studies, conference abstracts, grey literature and theses were excluded. There were no publication country or date limits applied, other than maintaining research interest in reporting of interventions in countries where Muslims are minority. Google Scholar enabled citation searching of more recent articles, and ancestry searching was undertaken of the reference lists of relevant retrieved articles.

2.3. Study Selection

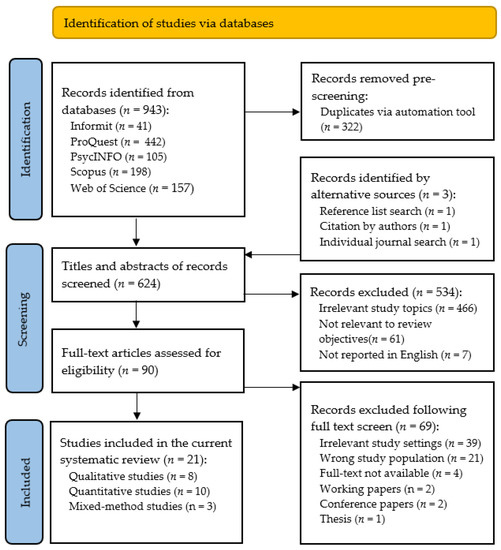

A total of 943 records were yielded in the initial electronic search, which included three from manual search searching. Upon deleting duplicates, (n = 322), remaining records (n = 624) were screened independently by two authors to identify records meeting the inclusion criteria. This resulted in retrieval of 90 potentially eligible for full text screening. Reading and evaluation of these 90 studies against the inclusion criteria resulted in a further 69 exclusions, leaving 21 research articles that met the final review criteria. The Prisma Flow Diagram of Studies included demonstrates the conceptual mapping of this process (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram of Studies included.

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

The researcher used a quality assessment checklist based on the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination’s Guidelines to assess the quality of each study (Akers et al. 2009). This involved the application of two screening questions to draw conclusions about the quality of evidence, specifically whether the interventions had been explained and whether the study was methodologically sound (Akers et al. 2009). In doing so, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) developed by (Hong et al. 2018) was used to record our quality assessment of quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies (Table S2).

Two general screening questions were informed by the MMAT to ensure articles had a clear research question and that the data collected in each study permitted addressing the research questions. However, in quantitative studies, the MMAT tool exposed missing reasons for not participation, risk of nonresponse bias, missing data and face validity of survey instruments in a randomized control trial, a nonrandomized intervention, and cross-sectional survey. In qualitative studies there were three important shortcomings of three studies: no clarification about using qualitative methods; data collection process not adequately described; and failure to explain coherence between qualitative data collection, analysis and interpretation. Two articles reporting on mixed-method research did not justify the use of mixed-method design. Nonetheless, the risk of bias in the reporting of results in qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies was addressed adequately in most articles.

2.5. Synthesis and Analysis of Results

A systematic coding scheme was developed following the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidelines to extract data from the selected studies (Akers et al. 2009). As part of this, testing of a pilot coding scheme on a subset of the selected studies enhanced the transparency and replicability of the data in the extraction process. The systematic coding scheme was applied to each selected study to record relevant information. Using this coding scheme, a table of the aggregated data was systematically developed (Table 1). Data extracted was of study settings and populations, research design and methods, and characteristics of interventions, including religious considerations. Authors (H.M., E.P., & M.H.) performed cross-checking and verification of information to ensure the credibility of review results.

Table 1.

Summary of studies included.

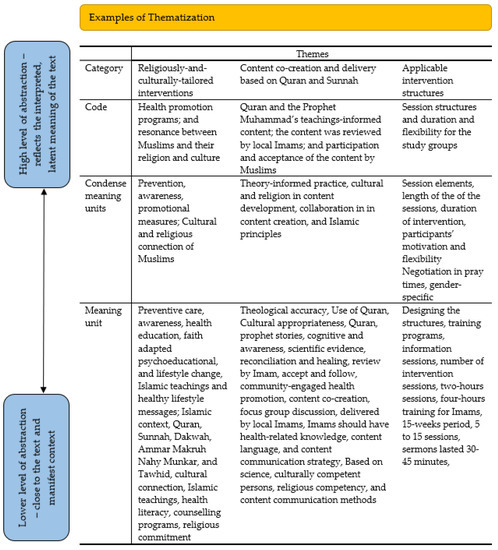

Data analysis identified common characteristics across the community health and wellbeing interventions, overview of the interventions and recommendations for future faith-based engagements with Muslim minorities. A combination of content and thematic analysis methods was used to comply with the systematic analysis of the generated evidence. Content analysis was chosen because it summarizes the content of a text through systematic coding and evaluation; therefore, the steps developed by Erlingsson and Brysiewicz (2017) were used for the abstraction process of the data (i.e., meaning unit, condense meaning unit, code, and category). Thematic analysis was added to content analysis to thematize the identified codes and categories of the characteristics of interventions (Braun and Clarke 2013) (Figure 2). Two topics are presented in the review results section: the studies’ characteristics, and the nature and features in interventions’ designs and implementation strategies for Muslim communities. The co-authors reviewed the clusters and provided their feedback on the themes and ordering the themes.

Figure 2.

Steps of analysis.

3. Results

3.1. The Study Characteristics

This section of the results describes the characteristics of the selected studies. For each study, the authors, the publication year, study objectives, research approaches, and the geographical location are reported in Table 1. The sample size, representation of Muslim participants in the sample size, study settings, the data collection tools, and the nature and features of interventions used in each study are summarized. The religious background of the participants, the theoretical approaches including intervention methods, and the intervention settings are described in more detail.

The articles represent 17 distinct studies and four similar studies. These four studies were written by the same lead author using the different research designs [qualitative (n = 1), quantitative nonrandomized (n = 2), and qualitative descriptive (n = 1)] in different Muslim subpopulations (Padela et al. 2018a, 2018b, 2018c, 2019). The results of the four studies, which are like each other in terms of interventions, are considered as one intervention in the review analysis.

In line with the geographical heterogeneity, as shown in Table S2, most of the studies were conducted in USA (n = 9), United Kingdom (n = 5) and Canada (n = 3) respectively. There were four mixed-methods, eight qualitative and nine quantitative studies [randomized control (n = 2), nonrandomized control (n = 5), and quantitative descriptive (n = 2)]. The sampling methods employed in the studies included randomized sampling (n = 2), purposive sampling (n = 18) and mass emailing (n = 1). Despite extensive reporting information on the sample characteristics across studies, little was reported about the educational and health background of the participants. The samples were selected purposively, and all had Muslim people as participants. The population size ranged from eight community health and wellbeing interventions to 2446 participants. The Muslim participants’ representation in the sample fluctuated from 16% to 100%.

Seven studies used theoretical frameworks in designing the interventions, such as Bader et al. (2006) who used ethnographic theory as the center of study in designing the preventive care program for Muslim community. Abdulwasi et al. (2018) used an ecological framework to inform the intervention; Padela (Padela et al. 2018b, 2019) used the theory of planned behaviour to provide a conceptual framework for religious tailoring in the intervention. All the interventions were spiritually tailored, including eight that were women-specific programs (Abdulwasi et al. 2018; Bader et al. 2006; Banerjee et al. 2017; Marinescu et al. 2013; Padela et al. 2018c, 2019; Tse 2002; Vu et al. 2018). The common intervention settings were mosques, community centers, and schools, based on the cultural care needs of the Muslim communities.

3.2. The Interventions: Nature and Features

The selected articles provided an overview of the diverse nature and features of each health or wellbeing intervention for Muslim communities living in Australia, Austria, Canada, United Kingdom and USA. While religious connections were perceived as inherent in Muslim communities (Bader et al. 2006; King et al. 2017; Vu et al. 2018), studies did not define the Islam, religion or culture with any clarity when they designed the interventions. Three subcategories frequently emerged in the description of interventions for Muslim communities: religiously tailored interventions, content co-creation and delivery based on the Quran and Sunnah, and applicable intervention structures.

3.3. Religiously Tailored Interventions

The interventions integrated two dimensions in the development of health or wellbeing interventions in terms of connection to the Muslim communities’ religious beliefs. These were the need to promote change and the need for religious attachment. Promoting lifestyle changes, specifically via health promotion, was the most indicated aspect across the interventions. These were predominantly focused on lifestyle change, preventive care, awareness building, health education, and faith adapted psychoeducation (Chaudhary et al. 2019; Hassan et al. 2021; Siddique and Mitchell 2013). In designing the programs, highest priority was given to the way the Muslim communities understood risk factors associated with physical, mental or social ill-being, and capability to build healthy lifestyle habits. More specifically, (Bader et al. 2006; Grace et al. 2008; Maynard et al. 2017) identified the lack of health literacy especially in Muslim women and children. These studies had emphasis on creating healthy habits (e.g., increased physical exercise and reduced intake of caloric-dense food). Such awareness and counselling programs were delivered in the forms of health information or messages (Padela et al. 2018a; Vu et al. 2018); lecture including power-points (Bader et al. 2006; Chaudhary et al. 2019; Padela et al. 2018a); factsheets (King et al. 2017); poster (Siddique and Mitchell 2013); training (Banerjee et al. 2017; Darko et al. 2020), and workbook (Tse 2002).

Of equal importance and covering with the connections to Islam and Muslim culture, the interventions’ emphasised the resonance between Islamic teachings and healthy lifestyle messages that were frequently cited in most studies. The Muslim participants in King et al. (2017) reported a need to situate the health programs within an Islamic context. This was elaborated by Zoellner et al. (2018), being that several religious aspects were important for developing an intervention with a Muslim community such as the Quran, Sunnah, Dawah (Dawah, meaning Islamic based community work), Ammar Makruh Nahy Munkar (i.e., enjoying what is good and forbidding what is bad), and Tawhid (Islamic concept that a Muslim accepts there is one God worthy of worship). Muslim communities were identified in Islam et al. (2012) as having religious commitment to build healthy habits when properly educated about their values and norms. Marinescu et al. (2013) provided opportunity for Muslim women to take 10–15 min break to perform prayer, if prayer time fell during the training. In a behavioral intervention, Padela et al. (2019) used religiously tailored messages to address salient mammography-related barrier beliefs such as modesty. Most of the interventions involved key religious components, i.e., mosques, Imams, the Quran and Sunnah to implement their programs in a religiously appropriate manner (Chaudhary et al. 2019; Padela et al. 2018b; Vu et al. 2018). The existing studies had homogeneous samples in terms of religious background; therefore, they could not investigate the correlation of specific cultural backgrounds of Muslim communities with common religious needs.

3.4. Content Co-Creation and Delivery Based on the Quran and Sunnah

The intervention content was generally co-created and involved a collaboration between the researchers, Imams, and the communities. When the information package and health messages were developed, the researchers addressed three major concerns for the Muslim community: the Quran and the Prophet Muhammad’s teachings-informed content; the content was reviewed by local Imams; and participation and acceptance of the content by Muslims, for maintaining theological accuracy and religious appropriateness (Grace et al. 2008; Hassan et al. 2021; Padela et al. 2019; Zoellner et al. 2018). Use of the Quran and Prophetic stories were commonly declared by several studies, especially those that investigated cognitive and awareness aspects of Muslims. For instance, (Zoellner et al. 2018; Hassan et al. 2021) included a scientific evidence-based description of types of trauma exposure and incorporated Islamic principles in regard to reconciliation and healing. Review of the content including sermon scripts and health messages occurred at Imam level. Reviewing by the Imams and Islamic Scholars provided a validity and reliability of the content that encouraged the Muslim participants to accept and follow them (Chaudhary et al. 2019). In addition, in a few community-engaged health and wellbeing programs, the content was co-created by the investigators and the participants through community focus group discussions to ensure messages were religiously-tailored (Abdulwasi et al. 2018; King et al. 2017; Padela et al. 2018c).

Delivering the content in an Islamic way was another subcategory issue of the interventions. Two factors in content delivery were identified in the studies: religiously competent persons, and religious competency in content communication methods. The content in the interventions were mostly delivered by local Imams (King et al. 2017; Padela et al. 2019; Vu et al. 2018). Several studies mentioned employing general dental practitioners, general medical practitioners, psychiatrists, community health workers, diabetes specialist nurses, physiotherapists and hospital doctors for conducting trainings or workshops (Banerjee et al. 2017; Darko et al. 2020; Islam et al. 2018a; Siddique and Mitchell 2013). While Imam-led sermons/classes were found to be effective in promoting women’s health, most investigators agreed that Imams should have health-related knowledge to make the interventions successful (Vu et al. 2018). Similarly, training on Islamic values and norms for the health professionals or others was emphasised in few studies.

In relation to content delivery, two important aspects were found: content language and content communication strategy. We presume that most content was communicated in English, as stated by Darko et al. (2020) in their study. A few investigators like Bader et al. (2006) offered Turkish-language information and Darko et al. (2020) had material available in Bangla-language. The majority of the studies did not discuss the language of communication used in delivering content. The content of the interventions was communicated via sermon scripts, group discussions, manuals, presentations, workbook, and booklets (King et al. 2017; Padela et al. 2018a, 2019). Few investigators included mentorship, guidance, social work intervention or counselling for the participants (Jozaghi et al. 2016). Multiple ways were considered in most interventions when the content was communicated with Muslims (Padela et al. 2019; Zoellner et al. 2018). However, critical analysis of the content communication methods for Muslims was absent, and in several studies, the religious competency of the persons communicating the content was compromised.

3.5. Applicable Intervention Structures

In identifying the applicable structural elements for interventions, the studies emphasised the applicable session structures and duration and flexibility for the study groups. Variations were found in designing the structures of training programs and information sessions. The number of intervention sessions ranged from two to six. Few interventions considered short-length sessions, such as two-hour sessions (Padela et al. 2018b); four-hours training for Imams (Zoellner et al. 2018), whereas maximum interventions were implemented from 5 to 15 weeks period, involving 5 to 15 sessions (Chaudhary et al. 2019; Hassan et al. 2021; Tse 2002). The duration of each session was also varied in the interventions, for instance (Padela et al. 2018c) described intervention sermons lasting 30–45 min, while the intervention described by Islam et al. (2018a) consisted of a two-hour group educational session and 90 min one-on-one catch-up.

The flexibility in participation was also considered in some studies, such as (Marinescu et al. 2013; Zoellner et al. 2018). Negotiation in prayer times, participation with no cost, and gender-specific programs were found effective in the successful implementation of programs and for achieving positive interventions outcomes. For example, Marinescu et al. (2013) added open swim for women to allow more time for practicing and also provided free women-only exercise classes that resulted in success in the number of study participants and research outcomes. If a prayer time occurred during class, Marinescu et al. (2013) also supported participants to take 10 to 15 min out of class to pray. The intervention of Zoellner et al. (2018) for trauma healing was also designed separately for men and women groups.

4. Discussion

Central to this integrative review is synthesizing and analyzing the characteristics and major outcomes of community health and wellbeing interventions in Muslim minority communities. The first critical finding to emerge from the analysis is that Muslims’ health beliefs and behaviors are rooted in the passages within the Quran, and Sunnah of the Prophet Muhammad.

A Muslim’s belief is based on the six pillars of beliefs, i.e., belief in God, belief in the Prophets, belief in the Holy Scriptures, belief in the Day of Judgment, belief in Angels, and belief in Fate (Koenig and Shohaib 2014). Muslims believe that God creates a disease as well as its remedy. Muslim patients hold beliefs that illness, suffering, and dying is a test from God, perceiving that illness is a trial by which one is absolved of their sins. Over the past thousand years, Islamic scientists have combined religious, philosophical, sociological, and historical aspects to understand the science of health, wellness, or disease and its treatment.

History records names such as Ibn Sina (known as Avicenna in the West) as one of the greatest Islamic physicians, who marked the golden age of Islamic medicine and has become known as the father of early modern medicine (El-Seedi et al. 2019; Koenig and Shohaib 2014). This is, in fact, a solid background as to why Muslims generally accept modern medical interventions (Ragsdale et al. 2018). Muslim scientists to this day continue to do research on medicinal plants depicted in the Holy Quran or used by the Prophet to treat contemporary diseases based on Islamic medicine. Mehmood et al. (2021), for instance, studied the use of medicinal plants scripted in the Quran or used by the Prophet (i.e., Allium Sativum, Allium cepa, Zingiber officinale, Cassia senna, Nigella sativa, and Olea europaea) for COVID-19 treatment as they have potent antiviral compounds. Islam in relation to health has two dimensions, explicitly as the root of Islamic medicine (the application of Islamic concepts in medicine which laid the basis for modern medicine), and medicinal Islam (Quran, Hadith, and Sunnah-based practices as healing practice). Islam is inevitably a great source of knowledge for Muslims, and the literature that we reviewed were consistent in observing the benefits of faith-based communication to promote caring for oneself in the prevention of ill-health; physical, psychological or social.

In our review, we found that the studies did not clearly define Islam as a religion when designing their health and wellbeing programs. There is difference between Muslim religiosity and perspectives, as well as ethnicity and culture. Therefore, we do not know from the current review what the different levels of success from the interventions related to different Islamic interpretations or different Muslim groups, ethnicities, cultures and so forth. This is because most studies homogenized samples of Muslims, which negated any ability to find associations between religiosity with cultural background and how interventions were designed. Studies, therefore, could not investigate correlations between outcomes according to specific Muslims from diverse cultural backgrounds. Nor could they show the common religious needs across diverse Muslim groups and communities.

We found that the interventions in most studies were co-designed by health or education professionals, together with religious leaders and/or mosque council members. Co-design of health and wellbeing content is important, particularly with ethnic minorities. Co-design can increase the accessibility and success of program implementation and outcomes. This is because it lends itself towards trustworthy learning spaces, increased commitment, reduction in tension arising from cultural or belief conflicts, and increase in the confidence of professionals (Delbridge et al. 2021). The community-based participatory approach utilized by (Banerjee et al. 2017; Marinescu et al. 2013; Siddique and Mitchell 2013), in their studies, are desirable participatory designs for use with minorities and vulnerable groups. While it is known that participatory approaches produce superior intervention outcomes, only one study (Zoellner et al. 2018) in our sample undertook a sequential research design in which a community’s needs were assessed first, prior to intervention design and delivery. The lack of focus on community consultation and emancipatory processes with Muslim communities in developing intervention or program content was evident.

Active participation and equitable partnerships in decision making are shown to improve health literacy and community wellbeing (Pfeiffer et al. 2018). Trust is closely related to religious beliefs. Thunström et al. (2021) investigated variations in trust levels between faiths. They found that Christians trust Christians more than other faith believers, while Muslims and atheists/agnostics trust all groups in the same way, and religious people trust people who have higher religious knowledge, if they are from the same belief. These concepts are consistent with the results of several studies in this review, that Islamic scholars are the key trusted persons to increase the active participation of Muslims in health, welfare and community wellbeing interventions.

In several studies, the delivery of either intervention information or delivery in Islamic ways were compromised because of the lack of competent persons. For example, in four studies, there was religious competency because interventions were delivered by Imams (King et al. 2017; Padela et al. 2019; Vu et al. 2018), and in other studies, there was intervention content competency when delivered by health and welfare professionals (Banerjee et al. 2017; Darko et al. 2020; Islam et al. 2018a; Siddique and Mitchell 2013). However, only a few studies engaged convergent design in the delivery of health interventions, training or workshops in which Imams and professionals both design and deliver the interventions together (Abu-Ras et al. 2008; Ghafournia 2017; Padela et al. 2018b). Participatory, co-design and convergent delivery is important for moving beyond mere engagement, for achieving sustainable change (Widianingsih et al. 2018) and achieving effective outcomes. While Vu et al. (2018) suggested that Imams should have health-related knowledge to increase effectiveness of interventions, and others proposed health professionals could have training on Islamic values. It seems that content development of interventions focused on the Quran and Sunnah, and the health or welfare messages for delivery, but did not focus much on content delivery methods.

Religiosity is an integral part of holistic care. It allows individuals to achieve an optimum state of wellbeing through harmonious inter-relationships between humans and with God (Lewinson et al. 2018). Therefore, the biomedical model alone is not enough to equip health professionals to provide whole-of-person care that incorporates bio-psycho-social and faith-based needs. Despite the relatively high importance of incorporating religious or faith-based beliefs in health and welfare interventions, professionals often feel reluctant to engage when clients voice religious views due to limited time, lack of understanding or privacy (Jawaid 2020; Palmer Kelly et al. 2020). This is despite growing recognition of associations with human wellbeing that beckons professionals to integrate respect for religiosity as an integral part of service.

5. Conclusions

This review considered studies reported in the English language and conducted in countries where Muslims represent minority populations. Except for one study in Austria, all others were from the Anglosphere—Australia, Canada, UK, and USA. We acknowledge that the literature reporting on religious considerations in interventions with Muslim minorities could be found in other languages, for example in German, considering the long presence of Turkish Muslims in Germany. Broader engagement with the literature in other Muslim minority countries, where languages besides English and other cultural and policy frames exist, would extend understanding.

It is important to understand the Muslim communities’ exposure to health and wellbeing interventions in non-Muslim majority countries. Across the studies reviewed, the need for religiosity and its connection with health and wellbeing behaviour change was acknowledged. The need for religious leaders in design of mosque-based and or discrete programs for Muslim minority communities is critical to their success. However, we emphasize the importance of intellectual apparatus, both Islamic understanding of health and welfare professionals, and of religious leaders on science informing health and wellbeing interventions.

With respect to context-specific interventions, there were eight programs specifically for women. Considerations of religiosity meant that programs had some flexibility; for example, Muslim women participating in interventions could take time out for prayer. Additionally, some interventions were at no cost, meaning that Muslims with lower socioeconomic status could participate. However, only two studies provided such opportunities, and we recommend further research on the inclusion of Muslim women’s voices in determining interventions for them.

Finally, this review provides a valuable insight into the critical elements in the design and delivery of health and wellbeing interventions that can be used to support caring for Muslim communities in Muslim minority countries. Improving effective health and welfare outcomes is possible through community consultation, engagement and effective communication strategies when designing interventions. Participatory, co-design or convergent delivery in which professionals and the subject community work together in both is potentially the most effective strategy for improving the quality of life of Muslim minorities.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/rel12090692/s1, Table S1: Databases and Search Syntax, Table S2: The quality appraisal for the selected studies, using Hong et al. (2018) MMAT tool.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M., M.J. and R.T.; formal analysis, H.M., E.P. and M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M., E.P. and M.H.; writing—review and editing, M.J. and R.T.; project administration, H.M., M.J. and R.T.; funding acquisition, R.T., H.M. and M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was completed by Flinders University to inform the evaluation of programs delivered by Community Development, Education and Social Support Australia (CDESSA) Inc., in conjunction with funding to Adelaide Mosque Islamic Society (AMISSA) Inc. from Multicultural Affairs, Department of Premier and Cabinet SA, Stronger Together Grants Scheme.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdulwasi, Munira, Meena Bhardwaj, Yuka Nakamura, Maha Zawi, Jennifer Price, Paula Harvey, and Ananya Tina Banerjee. 2018. An ecological exploration of facilitators to participation in a mosque-based physical activity program for South Asian Muslim women. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 15: 671–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Ras, Wahiba, Ali Gheith, and Francine Cournos. 2008. The Imam’s Role in Mental Health Promotion: A Study at 22 Mosques in New York City’s Muslim Community. Journal of Muslim Mental Health 3: 155–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akers, Jo, Raquel Aguiar-Ibáñez, and Ali Baba-Akbari Sari. 2009. Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care, 3rd ed. York: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rumayyan, Ahmed, Hamoud Alqarni, Bader S. Almanna, Naif Althonayan, Mohammed Alhalafi, and Nawaf Alomary. 2020. Utilization of Complementary Medicine by Pediatric Neurology Patients and Their Families in Saudi Arabia. Curēus (Palo Alto, CA) 12: e7960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Haq, M. Ashraf, Nor Azlina Binti Abd Wahab, Hj Abdullah Abd Ghani, and Nor Hayati Ahmad. 2016. Islamic Prayer, Spirituality and Productivity: An Exploratory Conceptual Analysis. Al-Iqtishad: Jurnal Ilmu Ekonomi Syariah 8: 271–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amri, Saara, and Fred Bemak. 2013. Mental health help-seeking behaviors of Muslim immigrants in the United States: Overcoming social stigma and cultural mistrust. Journal of Muslim Mental Health 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asadzandi, Minoo. 2017. Sound Heart: Spiritual Nursing Care Model from Religious Viewpoint. Journal of Religion and Health 56: 2063–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadzandi, Minoo. 2020. An Islamic Religious Spiritual Health Training Model for Patients. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 173–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bader, Anglika, Doris Musshauser, Filiz Sahin, Hayriye Bezirkan, and Margarethe Hochleitner. 2006. The Mosque Campaign: A cardiovascular prevention program for female Turkish immigrants. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift 118: 217–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, Ananya Tina, Mireille Landry, Maha Zawi, Debbie Childerhose, Neil Stephens, Ammara Shafique, and Jennifer Price. 2017. A pilot examination of a mosque-based physical activity intervention for South Asian Muslim women in Ontario, Canada. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 19: 349–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, H. Aboul-Enein. 2016. Health-Promoting Verses as mentioned in the Holy Quran. Journal of Religion and Health 55: 821–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosire, Edna N., Lindile Cele, Xola Potelwa, Allison Cho, and Emily Mendenhall. 2021. God, Church water and spirituality: Perspectives on health and healing in Soweto, South Africa. Global Public Health, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, Anila, Niccolo Dosto, Rachel Hill, Maiju Lehmijoki-Gardner, Phyllis Sharp, W. Daniel Hale, and Panagis Galiatsatos. 2019. Community Intervention for Syrian Refugees in Baltimore City: The Lay Health Educator Program at a Local Mosque. Journal of Religion and Health 58: 1687–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Dar, Michal, and Samira Obeid. 2017. Islamic Religious Leaders in Israel as Social Agents for Change on Health-Related Issues. Journal of Religion and Health 56: 2285–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colic-Peisker, Val. 2009. Visibility, settlement success and life satisfaction in three refugee communities in Australia. Ethnicities 9: 175–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, Natalie, Helen Dallosso, Michelle Hadjiconstantinou, Kerry Hulley, Kamlesh Khunti, and Melanie Davies. 2020. Qualitative evaluation of A Safer Ramadan, a structured education programme that addresses the safer observance of Ramadan for Muslims with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 160: 107979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delbridge, Robyn, Loretta Garvey, Jessica L. Mackelprang, Nicole Cassar, Emily Ward-Pahl, Mikaela Egan, and Anne Williams. 2021. Working at a cultural interface: Co-creating Aboriginal health curriculum for health professions. Higher Education Research and Development, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, Mesude, Yeter Durgun Ozan, and Özlem Doğan Yüksekol. 2021. Relationship between the religious attitudes of women with gynecologic cancer and mental adjustment to cancer. Palliat Support Care 19: 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Seedi, Hesham R., Shaden A. M. Khalifa, Nermeen Yosri, Alfi Khatib, Lei Chen, Aamer Saeed, Thomas Efferth, and Rob Verpoorte. 2019. Plants mentioned in the Islamic Scriptures (Holy Qur’ân and Ahadith): Traditional uses and medicinal importance in contemporary times. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 243: 112007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlingsson, Christen, and Petra Brysiewicz. 2017. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. African Journal of Emergency Medicine 7: 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Timothy M., Christian U. Krägeloh, and Marcus A. Henning. 2014. Religious coping, stress, and quality of life of Muslim university students in New Zealand. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 17: 327–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafournia, Nafiseh. 2017. Muslim women and domestic violence: Developing a framework for social work practice. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought 36: 146–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, Clare, Reha Begum, Syed Subhani, Peter Kopelman, and Trisha Greenhalgh. 2008. Prevention of type 2 diabetes in British Bangladeshis: Qualitative study of community, religious, and professional perspectives. British Medical Journal 337: 1094–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hardan-Khalil, Kholoud. 2020. Factors Affecting Health-Promoting Lifestyle Behaviors Among Arab American Women. Journal of Transcultural Nursing 31: 267–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi, Neda, Maryam Marzban, Bernadette Sebar, and Neil Harris. 2020. Religious Identity and Psychological Well-Being Among Middle-Eastern Migrants in Australia: The Mediating Role of Perceived Social Support, Social Connectedness, and Perceived Discrimination. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 12: 475–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Ahmed N., Heba Ragheb, Arfeen Malick, Zainib Abdullah, Yusra Ahmad, Nadiya Sunderji, and Farah Islam. 2021. Inspiring Muslim minds: Evaluating a spiritually adapted psycho-educational program on addiction to overcome stigma in Canadian Muslim communities. Community Mental Health Journal 57: 644–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Quan Nha, Pierre Pluye, Sergi Fàbregues, Gillian Bartlett, Felicity Boardman, Margaret Cargo, Pierre Dagenais, Marie-Pierre Gagnon, Frances Griffiths, and Belinda Nicolau. 2018. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of Copyright 1148552: 10. [Google Scholar]

- Illueca, Marta, and Benjamin R. Doolittle. 2020. The Use of Prayer in the Management of Pain: A Systematic Review. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 681–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Nadia S, Darius Tandon, Runi Mukherji, Michael Tanner, Krittika Ghosh, Gulnahar Alam, Mamnunal Haq, Mariano Jose Rey, and Chau Trinh-Shevrin. 2012. Understanding Barriers to and Facilitators of Diabetes Control and Prevention in the New York City Bangladeshi Community: A Mixed-Methods Approach. American Journal of Public Health 102: 486–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Farah, Nazilla Khanlou, Alison Macpherson, and Hala Tamim. 2018a. Mental Health Consultation Among Ontario’s Immigrant Populations. Community Mental Health Journal 54: 579–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Nadia S., Laura C. Wyatt, Md Taher, Lindsey Riley, S. Darius Tandon, Michael Tanner, B. Runi Mukherji, and Chau Trinh-Shevrin. 2018b. A Culturally Tailored Community Health Worker Intervention Leads to Improvement in Patient-Centered Outcomes for Immigrant Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Clinical Diabetes 36: 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jawaid, Hena. 2020. Assessing Perception of Patients and Physicians Regarding Spirituality in Karachi, Pakistan: A Pilot Study. Permanente Journal 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepson, Ruth G., Fiona M. Harris, Stephen Platt, and Carol Tannahill. 2010. The effectiveness of interventions to change six health behaviours: A review of reviews. BMC Public Health 10: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jongen, Crystal Sky, Janya McCalman, and Roxanne Gwendalyn Bainbridge. 2017. The implementation and evaluation of health promotion services and programs to improve cultural competency: A systematic scoping review. Frontiers in Public Health 5: 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jozaghi, Ehsan, Muhammad Asadullah, and Azim Dahya. 2016. The role of Muslim faith-based programs in transforming the lives of people suffering with mental health and addiction problems. Journal of Substance Use 21: 587–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Shamsul, and Mahjabeen Ahmad. 2014. The case for Muslim aged care in the west. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging 26: 281–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Rebecca, Sahil Warsi, Amanda Amos, Sundes Shah, Ghazala Mir, Aziz Sheikh, and Kamran Siddiqi. 2017. Involving mosques in health promotion programmes: A qualitative exploration of the MCLASS intervention on smoking in the home. Health Education Research 32: 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G., Terrence D. Hill, Steven Pirutinsky, and David H Rosmarin. 2021. Commentary on “does spirituality or religion positively affect mental health”? The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 31: 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G., and Saad Al Shohaib. 2014. Health and Well-Being in Islamic Societies: Background, Research, and Applications, 2014th ed. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG, vol. 9783319058733. [Google Scholar]

- Koerner, Catherine, and Soma Pillay. 2020. Policy, Practice, and Legislative Matters. In Governance and Multiculturalism: The White Elephand of Social Construction and Cultural Identities. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 221–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kongsuwan, Waraporn, and Warangkana Chatchawet. 2019. Effect of nursing intervention integrating an Islamic praying program on labor pain and pain behaviors in primiparous Muslim women. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research 24: 220–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinson, Lesline P., Wilfred McSherry, and Peter Kevern. 2018. “Enablement”—Spirituality Engagement in Pre-Registration Nurse Education and Practice: A Grounded Theory Investigation. Religions 9: 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marinescu, Lluiza G., Denise Sharify, James Krieger, Brian E. Saelens, Jeniffer Calleja, and Ayaan Aden. 2013. Be Active Together: Supporting Physical Activity in Public Housing Communities Through Women-Only Programs. Progress in Community Health Partnerships-Research Education and Action 7: 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maynard, Maria, Graham Baker, and Seeromanie Harding. 2017. Exploring childhood obesity prevention among diverse ethnic groups in schools and places of worship: Recruitment, acceptability and feasibility of data collection and intervention components. Preventive Medicine Reports 6: 130–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, John, Anna Kirova, and W. Andy Knight. 2016. Gauging social integration among Canadian Muslims: A sense of belonging in an age of anxiety. Canadian Ethnic Studies 48: 21–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, Helen J., and Tejaswini Vishwanath Patil. 2016. Manipulative silences and the politics of representation of boat children in Australian print media. Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 30: 602–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, Helen J., and Nismah Qonita. 2020. Indonesia’s Orphanage Trade: Islamic Philanthropy’s Good Intentions, Some Not So Good Outcomes. Religions 11: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mehmood, Azhar, Suliman Khan, Sajid Khan, Saeed Ahmed, Ashaq Ali, Mengzhou Xue, Liaqat Ali, Muhammad Hamza, Anum munir, Saad ur Rehman, and et al. 2021. In silico analysis of quranic and prophetic medicinals plants for the treatment of infectious viral diseases including corona virus. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 28: 3137–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, Claudia, Rajna Ogrin, Hamzah Al-Zubaidi, Arti Appannah, Sally McMillan, Elizabeth Barrett, and Colette Browning. 2017. Diversity training for community aged care workers: An interdisciplinary meta-narrative review. Educational Gerontology 43: 365–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minas, Harry, Ritsuko Kakuma, Lay San Too, Hamza Vayani, Sharon Orapeleng, Rita Prasad-Ildes, Greg Turner, Nicholas Procter, and Daryl Oehm. 2013. Mental health research and evaluation in multicultural Australia: Developing a culture of inclusion. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 7: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Munsoor, Mohamed Safiullah, and Hannah Safiullah Munsoor. 2017. Well-being and the worshipper: A scientific perspective of selected contemplative practices in Islam. Humanomics 33: 163–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, John. 2016. Multiculturalism’s Double-Bind: Creating Inclusivity, Cosmopolitanism and Difference. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Novita, Rice, Mustakim, and Febi Nur Salisah. 2021. Determination of the relationship pattern of association topic on Al-Qur’an using FP-Growth Algorithms. IOP Conference Series. Materials Science and Engineering 1088: 12020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padela, Aasim I., Sana Malik, Milkie Vu, Michael Quinn, and Monica Peek. 2018a. Developing religiously-tailored health messages for behavioral change: Introducing the reframe, reprioritize, and reform (“3R”) model. Social Science and Medicine 204: 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padela, Aasim I., Sana Malik, and Nadia Ahmed. 2018b. Acceptability of Friday sermons as a modality for health promotion and education. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 20: 1075–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padela, Aasim I., Sana Malik, Akila Ally Syeda, Michael Quinn, Stephen Hall, and Monica Peek. 2018c. Reducing Muslim Mammography Disparities: Outcomes From a Religiously Tailored Mosque-Based Intervention. Health Education and Behavior 45: 1025–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padela, Aasim I., Sana Malik, Hena Din, Stephen Hall, and Michael Quinn. 2019. Changing Mammography-Related Beliefs Among American Muslim Women: Findings from a Religiously-Tailored Mosque-Based Intervention. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 21: 1325–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., David Moher, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer Kelly, Elizabeth, Madison Hyer, Nicolette Payne, and Timothy M. Pawlik. 2020. Does spiritual and religious orientation impact the clinical practice of healthcare providers? Journal of Interprofessional Care 34: 520–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parati, Graziella. 2017. Transitive spaces. In Migrant Writers and Urban Space in Italy. Edited by Graziella Parati. Cham: Springer, pp. 37–85. [Google Scholar]

- Pasyar, Nilofar, Masoume Rambod, and Mostafa Jowkar. 2020. The Effect of Peer Support on Hope Among Patients Under Hemodialysis. International Journal of Nephrology and Renovascular Disease 13: 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Patil, Tejaswini Vishwanath, and Helen Jacqueline McLaren. 2019. Australian Media and Islamophobia: Representations of Asylum Seeker Children. Religions 10: 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pfeiffer, Jane, Hong Li, Maybelline Martez, and Tim Gillespie. 2018. The Role of Religious Behavior in Health Self-Management: A Community-Based Participatory Research Study. Religions 9: 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Powers-James, Catherine, Adriana Alvarez, Kathrin Milbury, Andrea Barbo, Katherine Daunov, Gabriel Lopez, Lorenzo Cohen, Marvin O. Delgado-Guay, Olufunmilayo I. Olopade, and Richard T. Lee. 2020. The Influence of Spirituality and Religiosity on US Oncologists’ Personal Use of and Clinical Practices Regarding Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Integrative Cancer Therapies 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragsdale, Judith R., Mohammad Othman, Ruby Khoury, Christopher E. Dandoy, Karen Geiger-Behm, Mark Mueller, Eyad Mussallam, and Stella M. Davies. 2018. Islam, The Holy Qur’an, and Medical Decision-Making: The Experience of Middle Eastern Muslim Families with Children Undergoing Bone Marrow Transplantation in the United States. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling 72: 180–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambod, Masoume, Farkhondeh Sharif, Zahra Molazem, and Kate Khair. 2019. Spirituality Experiences in Hemophilia Patients: A Phenomenological Study. Journal of Religion and Health 58: 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambod, Masoume, Nilofar Pasyar, and Mahsa Mokhtarizadeh. 2020. Psychosocial, Spiritual, and Biomedical Predictors of Hope in Hemodialysis Patients. International Journal of Nephrology and Renovascular Disease 13: 163–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossato, Lucas, Ana M. Ullán, and Fabio Scorsolini-Comin. 2021. Profile of scientific production on religiosity and spirituality in coping with childhood cancer. Archive for the Psychology of Religion. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salma, Jordana, and Bukola Salami. 2020. “Growing Old is not for the Weak of Heart”: Social isolation and loneliness in Muslim immigrant older adults in Canada. Health & Social Care in the Community 28: 615–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sena Lomba Vasconcelos, Ana Paula, Alessandra Lamas Granero Lucchetti, Ana Paula Rodrigues Cavalcanti, Simone Regina Souza da Silva Conde, Lidia Maria Goncalves, Filipe Rodrigues do Nascimento, Ana Claudia Santos Chazan, Rubens Lene Carvalho Tavares, Oscarina da Silva Ezequiel, and Giancarlo Lucchetti. 2020. Religiosity and Spirituality of Resident Physicians and Implications for Clinical Practice-the SBRAMER Multicenter Study. Journal of General Internal Medicine 35: 3613–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddique, Ifran, and Douglas A. Mitchell. 2013. The impact of a community-based health education programme on oral cancer risk factor awareness among a Gujarati community. British Dental Journal 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohail, Malik Muhammad, Qaisar Khalid Mahmood, Falak Sher, Muhammad Saud, Siti Mas’udah, and Rachmah Ida. 2020. Coping Through Religiosity, Spirituality and Social Support Among Muslim Chronic Hepatitis Patients. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 3126–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thunström, Linda, Chian Jones Ritten, Christopher Bastian, Elizabeth Minton, and Dayana Zhappassova. 2021. Trust and Trustworthiness of Christians, Muslims, and Atheists/Agnostics in the United States. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 60: 147–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, Tina. 2002. Islamic Community Worker Training Program for the Management of Depression. The Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health 1: 121–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, Milkie, Hadiyah Muhammad, Monica E. Peek, and Aasim I. Padela. 2018. Muslim women’s perspectives on designing mosque-based women’s health interventions-An exploratory qualitative study. Women & Health 58: 334–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, Robin, and Kathleen Knafl. 2005. The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 52: 546–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widianingsih, Ida, Helen Jaqueline McLaren, and Janet McIntyre-Mills. 2018. Decentralization, Participatory Planning, and the Anthropocene in Indonesia, with a Case Example of the Berugak Dese, Lombok, Indonesia. In Balancing Individualism and Collectivism: Social and Environmental Justice. Edited by Janet McIntyre-Mills, Norma Romm and Yvonne Corcoran-Nantes. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 271–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zoellner, Lori, Belinda Graham, Elizabeth Marks, Norah Feeny, Jacob Bentley, Anna Franklin, and Diana Lang. 2018. Islamic Trauma Healing: Initial Feasibility and Pilot Data. Societies 8: 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).