2. The Shifting Underground: Mingqi, Hunping, Stupa, and the Early Translation of Buddhism in Local Tombs

Before the introduction of Buddhism to China during the Eastern Han dynasty, the Chinese buried their deceased’s bodies without cremation. In the Qin and Western Han period (221 BCE–8 CE), the rich and powerful built enormous aboveground tumuli with elaborate underground chambers. The Mausoleum of the First Emperor of Qin (

Qin Shihuangdi), for instance, had two layers of rectangular enclosure of walls with gates on the cardinal directions, which measured 2165 m north–south and 940 m east–west for the outer layer, and within the inner layer, a pyramidal rammed earth mound (封土

fengtu) with a base square of 350 m each side and an extant height of 76 m.

5 Commoners had much humbler tombs, buried with at least several specially made objects or utensils they once had during their lifetimes to accompany their afterlives. Buddhists, on the other hand, cremated the remains of the deceased, especially the venerated ones, to create the relics known as

sharila, which was believed to be a confirmation of

nirvana, the ultimate enlightenment. On such occasions, such as in the case of Shakyamuni Buddha, structures such as the stupa would be built to honor such a spiritual achievement.

6 During the early Medieval period of the 3rd to 6th centuries, with the progressive Buddhist conversion and the gradual establishment of Buddhist communities and monasteries, pagodas were built to honor both relics of Buddha and the remains of great Buddhist masters.

7 Burial customs of common Buddhists also started to bear the imprints of the new faith.

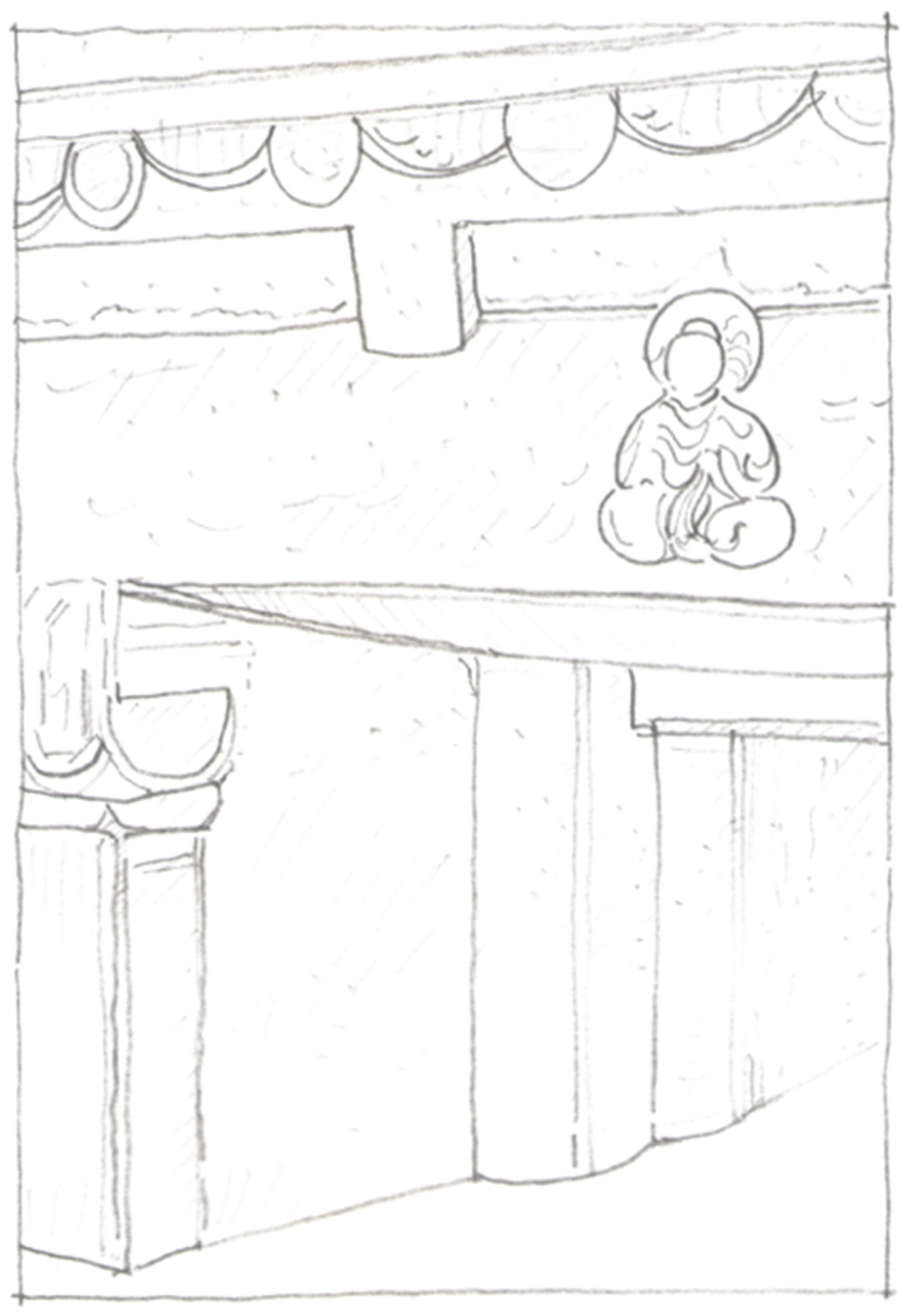

The reception of Buddhism was incorporated into the Chinese funeral tradition by the substitution of the previous Confucian and Daoist imageries with Buddhist deities and forms. The images of Buddha appeared in Chinese tombs as early as the late 2nd century. In the cave-tomb from Mahao in Sichuan province, for instance, a seated Buddha carved on the lintel carries the unmistakable Buddhist iconographic marks of

ushnisha and

abhaya mudra (see

Figure 1).

Among other narrative carvings of Confucian ideology and morality, such as the famous Jing Ke’s attempted assassination of the First Emperor of Qin, it occupies a place previously occupied by the Daoist gods of Dong Wanggong 東王公 and Xi Wangmu 西王母. Although the icon is Buddhist, the concept and functionality behind the Buddha image is Daoist, as Professor Wu Hung pointed out that “this holy image is no longer an object of worship on public occasion, but is a symbol of the deceased individual who had hoped to attain immortality after his death”.

8 Buddhism was translated into the Chinese architectural context of the 2nd to 3rd centuries through the substitution of traditional Chinese deities with the Buddha. Such an understanding of the foreign god was also confirmed by the contemporary intellectual discourse on Buddhism. In the famous monograph

Lihuolun 理惑論, Mu Rong, the late 2nd-century Buddhist scholar, frequently cited Confucius and Laozi in the defense of Buddhism and argued that Buddha is an honorary title for the enlightened one, much like the title of

Shen 神 for the Three

Huang 三皇, the title

Sheng 聖 for the Five

Di 五帝, and the supreme origin of

Dao and

De 道德之元祖.

9 Deities and saints of both Confucianism and Daoism were evoked to help for a translation of Buddha into the Chinese religious contexts.

Grave goods of the early Medieval China experienced a similar Buddhist translation. The previously mentioned specially made objects buried to serve the afterlife of the tomb masters are known as

mingqi 明器, which literally means the “bright utensils”. Since the Han dynasty, a type of

mingqi made in the form of house model became increasingly popular. Archaeologists discovered such architectural

mingqi in large quantities, especially from the tombs of the Eastern Han dynasty and after.

10 Some

mingqi house models feature multi-story towers with painted or sculpted details of wooden structure, such as post-and-lintel frames and the

dougong 斗拱 brackets. These multi-story tall buildings were either interpreted as the watchtowers for defensive purpose and scenery enjoyment

11 or the reference to the dwelling of immortals.

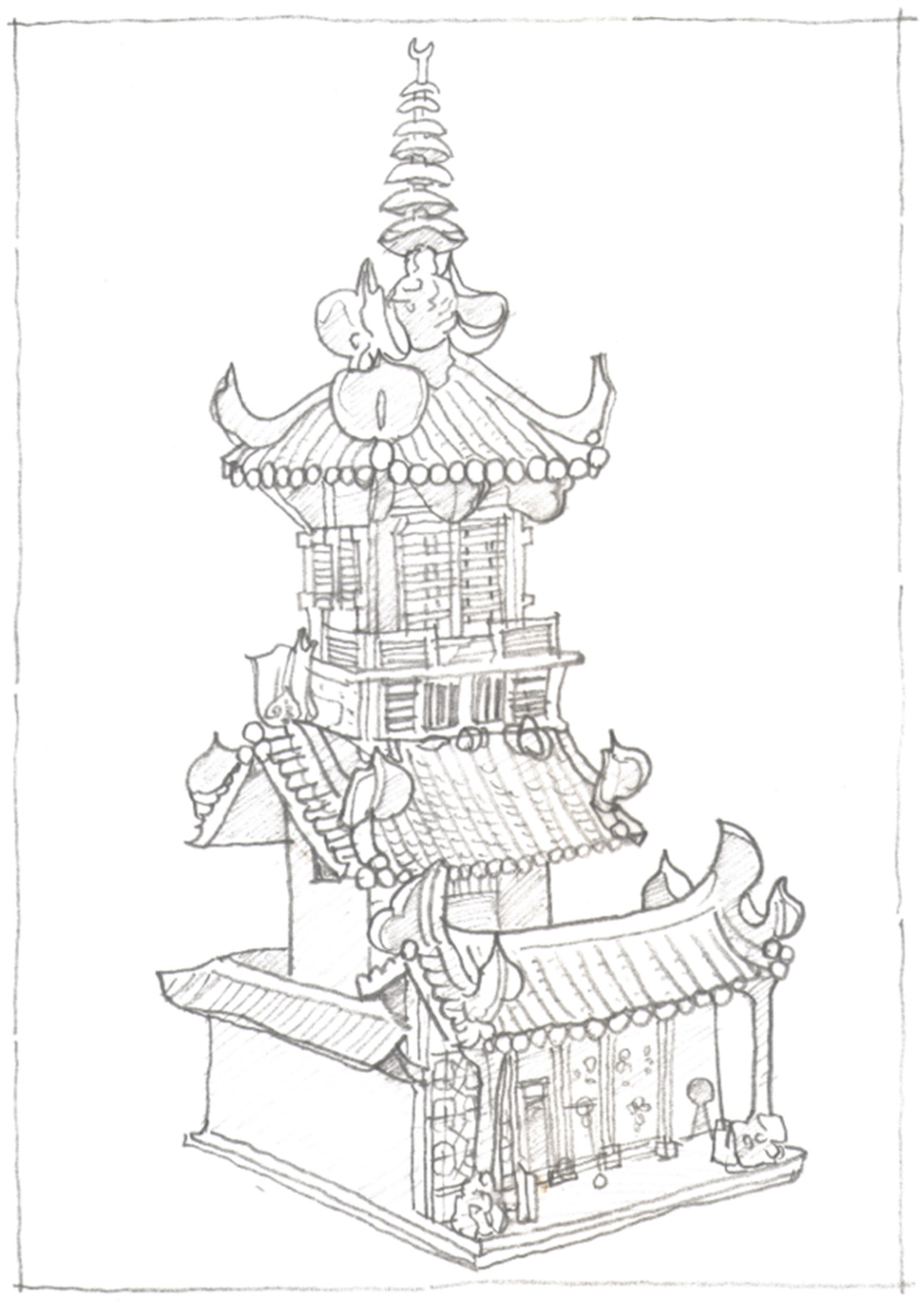

12 The former fulfills the Confucian filial service of the deceased in the similar way as they were alive, while the latter was deeply imbedded in the Daoist practice aiming for immortality. A house model from Xiangyang in Hubei province, on the other hand, features Buddhist architectural details (see

Figure 2).

This house shares with other Eastern Han and Three Kingdoms period mingqi model in the combination of a main tower with a walled and gated courtyard. Both the tower and the gate have wooden frames supporting tiled roofs. The main tower is a two-story structure. The first story has a rectangular plan and an overhanging two-slope roof, supporting a wooden platform on brackets, above which the second story with a square plan and a four-slope roof sits. The unique feature is a pole with seven umbrellas, rising from the center of the four-slope roof, which clearly resembles the vertical axis and chatras in Indian stupa such as the one from the Great Stupa at Sanchi.

The typical roofs of

mingqi houses from this period often have sculpted birds standing the tops and ends of the ridges. Here, in the Xiangyang model, while the center of the top horizontal ridge supports a Buddhist axis, the ends of both the horizontal and slanting ridges turn into a leaf-like shape. According to Luo Shiping from the Centra Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, these leaves represent the bodhi tree, under which Shakyamuni Buddha meditated and became enlightened.

13 Thus, the Buddhist concepts of enlightenment and

nirvana were both translated into the Chinese funeral practice through the incorporation of iconic imageries from the life of Buddha and the features of the stupa into the

mingqi house. The terminal of the axis in the Xiangyang model is a crescent, which is neither a Chinese nor an Indian architectural feature. Rather, some stupa images from Central Asia bare crescent forms on the railing poles. The formal translation of Buddhist architecture into the Chinese funeral practice was not direct and straightforward. Given the great distance and diverse cultures in between China and the original land of the Buddha, it might had gone through many mediating stages.

14Another type of funeral object that yields rich architectural images is called

hunping 魂瓶, the bottle of the soul. Though made in ceramic with a body shaped like a jar,

hunping was not made to be used as a container. Small holes often appear in the middle part of the body and the round mouth is often sealed with a highly sculptural complex of additional decorations. The sculptural forms forming the crown of

hunping are often tall, concentric in plan, and quite architectural, featuring a two to three-story tower-pavilion amid a crowd of animal and human figures of both real and mythical, birds, lions, phoenixes, musicians, dancers, singers, etc. The appearance of

hunping was in the 3rd century, much later than the architectural

mingqi, and spread in the following centuries of the early Medieval period mainly in the lower Yangtze provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang. Wu Hung argued that an important prototype of the

hunping jar might be the reliquary used in the Indian world such as the famous Reliquary of Kanishka from the 2nd century.

15 He suggested that

hunping was primarily used by the northern Chinese exiled to the southern Yangtse area during the catastrophic collapse of the Western Jin dynasty, who had lost the bodies of the deceased and adopted the local tradition to provide the resting places for their souls using such vessels.

Hunping, thus, became the embodiment of a specific funeral practice amalgamating the Confucian filial rites, the ancient shamanistic soul-calling (

zhaohun 招魂) of the southern (Chu and Wu) areas, and the Buddhist belief in the separation of the physical remains and the true self.

16The tangible Buddhist decorative motifs are human figures on some

hunping jars that can be identified as Buddha or bodhisattvas through their attributes such as the

ushnisha, halo, or

mudras. While many previous discussions focus on the stylistic and iconographic analysis of imageries, this article pays special attention to the architectural elements in the

hunping. A typical crown structure of the

hunping has a concentric plan with a pyramidal three-dimensional form. In a 3rd-century Western Jin dynasty

hunping jar from the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the peaking center is an urn with a wide circular opening, surrounded by four smaller urns of similar shape and proportion (see

Figure 3).

The four small urns form the corners of a square, defining the four cardinal directions. On one direction, four layers of sloping roofs create a façade of a wooden tower, under which a square opening serves as the only entrance hidden behind a mounted figure, who is seemingly emerging from the gate of the tower, defined by two solid pillars. Two additional mounted figures frame on the outer sides of the pillars, seemingly guarding the gate. On both sides of the four-story tower are singers and musicians playing various instruments, divided into four groups by three flocks of birds. All the birds are heading up with widely open wings, creating a strong soaring momentum. The base of the crown complex and the openings of the top central urn are both circular, while the four corner urns define a square set in between the larger lower circle of the base and the smaller upper circle of the central urn (see

Figure 4).

While the urns and the architectural, anthropomorphic, and zoomorphic figures are typical decorative motifs on

hunping jars, the entrance tower in the MFA Boston item strongly resembles a later pagoda in East Asia, and the combination of square and circle, as well as the emphasis on both the cardinal directions and the axial centrality, share much in common with the Indian stupa. Like a tower-pavilion style pagoda (

lougeshi-ta 樓閣式塔), the MFA

hunping tower has multiple layers of tiled roofs diminishing in size and width toward the top. Attached to the wall of the jar, it especially resembles the wooden edifice added to make a façade for a large Buddhist cave, for instance, the Nine-Story Pagoda (

jiucengta 九層塔) at the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, Gansu province (see

Figure 5).

The cave behind the pagoda façade was created during the early Tang dynasty (618–907), much later than the Boston hunping, and the wooden structure has been rebuilt many times. It was also unlikely that the Dunhuang pagoda copied the images of the Eastern Jin dynasty hunping. The resemblance must be a reflection of a common architectural prototype they both shared, such as the context for the generation of meanings in a linguistic translation to which both the original and targeted languages refer.

The grouping of a large central stupa surrounded by four smaller ones on the corners can be traced back to the stupa at the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodhgaya, the place where historical Buddha attained enlightenment. The stupa with a tall

shikara tower surrounded by four smaller one elevated on a square platform had undergone much rebuilding and repairs, but the original construction was at least since the Gupta dynasty (c. 319–467), and its prototype might even be earlier. The Diamond Throne,

vajrasana, covered by the Bodhi tree, under which Buddha was believed to have meditated, was said to be established by King Ashoka (r. c. 268 to 232 BCE).

17 It is still a popular style in Theravada stupas of Southeastern Asia. Additionally, some scenes in Dunhuang murals from the Northern dynasties period (386–577) contain pagoda-like structures with similar assemblage. In late imperial China, such an assemblage in the Buddhist relics structure can be found in the Vajrayana school (

Mizong 密宗) known as

Jingangbaozuo-ta 金剛寶座塔, the Diamond Throne Pagoda, which became especially popular among the monasteries related to the Tibetan practice since the Yuan dynasty.

18A

hunping jar in the National Museum in Beijing from the same region and period, indeed, has the five urns replaced by five pavilions, with the central one elevated on a tower (see

Figure 6).

Hunping jars with five pavilions arranged in similar concentric plan can also be found in other museum collections, for instance, the one from the Museum of the Six Dynasties in Nanjing.

19 With the

que gates added to mark the entrance and axiality, the whole complex strongly resembles a

Jingangbaozuo-ta such as the one from the Ming dynasty Zhenjue Monastery in Beijing or the one from the Qing dynasty Five Pagodas Monastery in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia (see

Figure 7).

3. The Transformed Passage: Que Gate, Mubiao, and the Ashoka Column

The early incorporation of Buddhist ideas and imageries in Chinese funeral architecture, in the 2nd to 3rd centuries as discussed in the previous section, concerns mostly the afterlife of the deceased, remains on objects that were not meant to be engaged by the livings, and concentrates largely underground. In the following 4th to 6th centuries, the translation of Buddhist architecture into the Chinese funeral context became more psychological, life engaging, ritually related, and manifests mainly along the aboveground passage.

20 While objects discussed in the previous section were mostly from tombs of common well-to-do families, relatively of humble origins, cases sampled in this section can be related to the funeral practice of the imperial rulers.

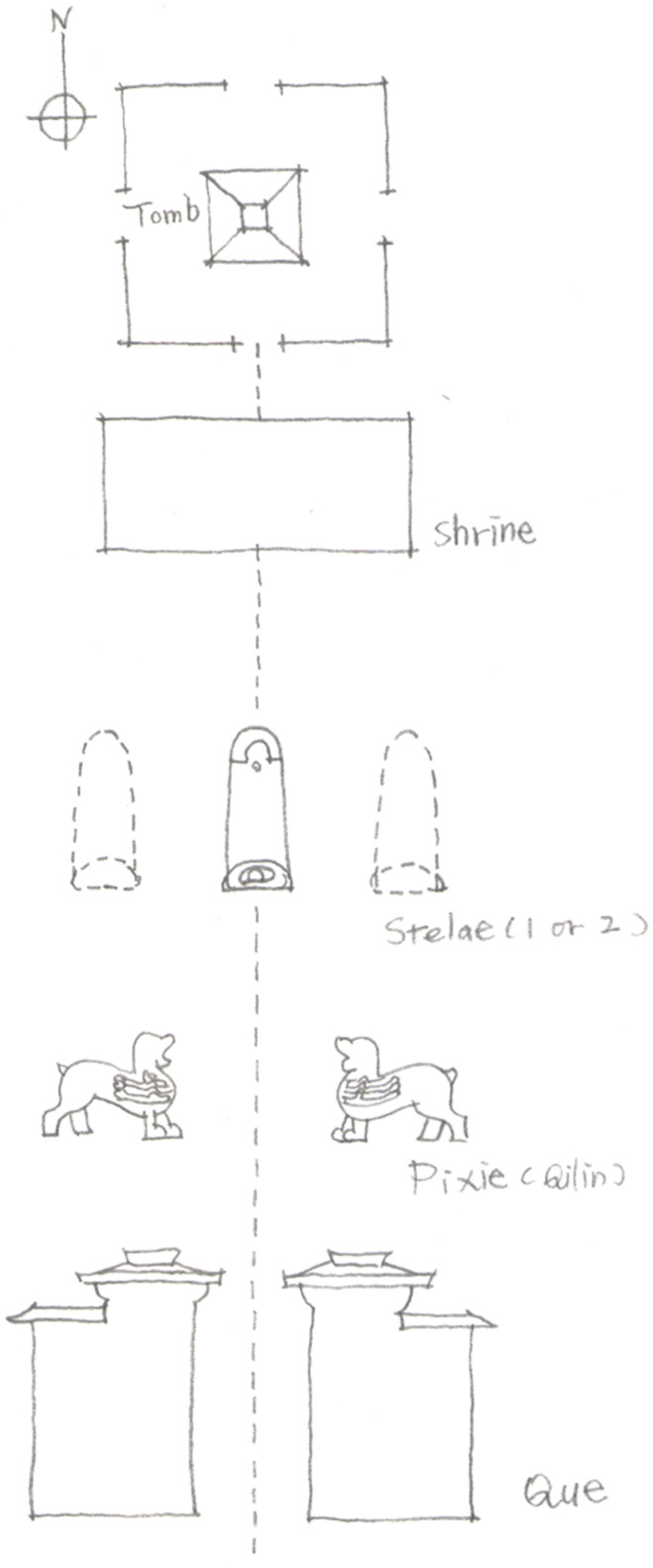

21 Compared to those of the previous Han dynasty, imperial mausoleums from the Eastern Jin (266–420) and the Southern Dynasties (420–589) were much smaller in terms of both the aboveground mounds and the underground chambers.

22 The sculptural scheme framing the spirit path leading from the entrance to the tomb mound, however, became more refined and elaborate with concentrated Buddhist translation of architectural elements.

The sculptures framing a typical Southern Dynasties spirit path

shendao 神道 for the imperial mausoleum start with the chimerical creature combining the body of a lion and a pair of wings, a mythical animal known as

qilin 麒麟 or

pixie 辟邪. They are followed in a certain distance by a pair of free-standing columns and ended with a pair of stone steles on turtle bases

23 (see

Figure 8).

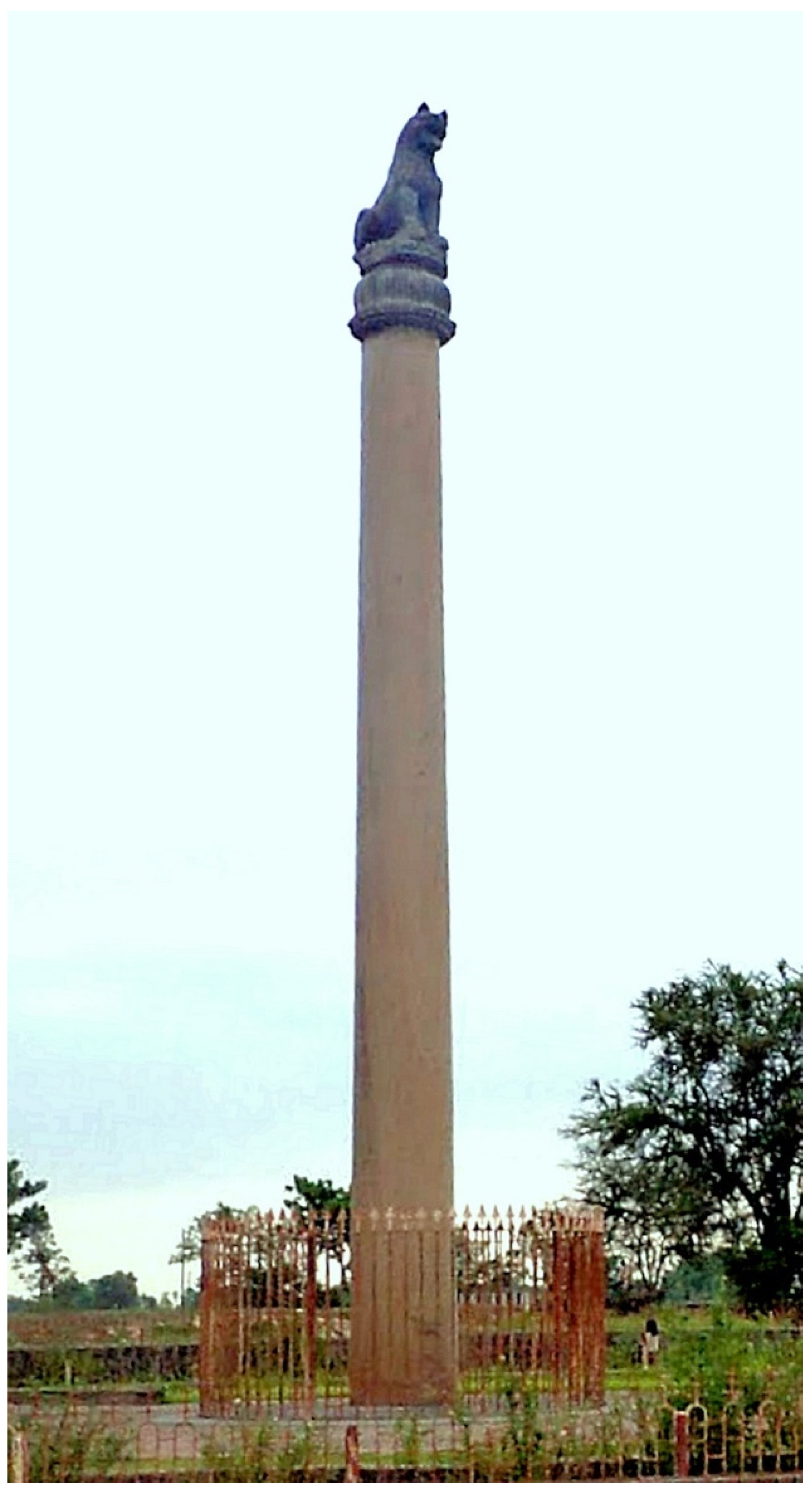

The stone column often bears a rectangular tablet inscribed with the name and titles of the tomb master, thus known as

mubiao 墓表, the sign of the tomb. The

mubiao pillars are rich in details of European, Indian, or West Asian origins (see

Figure 9).

The Prince Xiao Jing (477–523)

mubiao from the Liang Dynasty, for instance, has a fluted shaft similar to that of an ionic column in classical Greco-Roman architecture. The earliest fluted column shaft came from the Eastern Han dynasty, such as the

mubiao of the Cleric Qin of the You Prefecture 東漢幽州書佐秦君墓表 from the modern-day Beijing area

24 (see

Figure 10).

The round details at the end of the fluting resemble the egg-and-dart in a classical ionic capital. The twin animal figures framing the neck connecting the fluted shaft below and the inscribed tablet above resemble the incorporation of symmetrical animal figures in the carved capitals from the Persian Persepolis.

25The framing of a passageway with free-standing columns can be considered a Buddhist translation of the Chinese

que 闕 gate.

26 A standard spirit path of an Eastern Han cemetery often starts with a pair of stone

que towers, followed by mythical animals and stelae and ending at the shrine in front of the pyramidal rammed earth tumulus (see

Figure 11).

The

mubiao of the Cleric Qin of the You Prefecture, for instance, was originally part of a

que gate complex. Fragments of Eastern Han funeral

que had been discovered in different areas, especially from the southeastern Sichuan province.

27 The stone

que used in the funeral complex was already a translation of its counterpart with wooden structure serving in the living quarters. In an actual wooden

que gate, the two towers framing the passageway are often connected in the middle above the path with roofs and sometimes verandas, such as the ones in the crown complex of the

hunping jar from the museum in Nanjing. They might also be connected with enclosing walls thus serve the function of an actual gate. In the tombs from the period of Eastern Jin and the Southern Dynasties (266–589), however, the free-standing stone

que towers preceding the mythical animal sculptures largely disappeared and the

mubiao columns were added following them.

These

mubiao pillars bear great similarities with the Ashoka columns in India from the 3rd century BCE.

28 The combination of animal sculptures at the summit, a slender shaft with inscriptions planted on the ground, and a seat decorated with lotus petals in-between is a characteristic feature for the columns ordered to be founded by Ashoka (r. 268–232 BCE), the model king for Buddhist sponsorship and the quintessential example of

chakravarti, a religious universal ruler. Known as Ayuwang 阿育王 in Chinese, many monasteries in his name were established in his honor in early Medieval China, including the one rebuilt by Emperor Wu of Liang 梁武帝, the cousin of Prince Xiao Jing.

29 The Xiao Jing

mubiao has a sculpture of a winged chimerical creature standing on the top of a large disk with lotus petal decoration. A comparison of the Xiao Jing

mubiao (early 6th century) with the Ashoka pillar (3rd century BCE) (see

Figure 12), the Persepolis columns (5th–4th centuries BCE), and the Naxos Sphinx pillar (6th century BCE) (see

Figure 13) clearly indicates the cognate relationships among them and the possible transmission of the chimerical column from the West to the East. Buddhism served as a very important medium for the formal translation in this monumental construction.

While the major formal features of the Xiao Jing

mubiao were mainly of foreign origins, the tablets inscribed with the tomb master’s name and official titles, a traditional Confucian ritual for honoring the deceased ancestors, also went through the Buddhist translation. With spirit path running from south to north, two

mubiao pillars used to stand on the east and west sides of the passage. Today, only the one on the west side survived. The inscriptions on its tablet, however, would be unreadable to any literate Chinese on the first sight. The twenty-three Chinese characters were written in mirror-image, or

fanshu 反書, exactly symmetrical stroke by stroke with those on the tablet of the missing east

mubiao pillar. In traditional Chinese cosmology, the east, which is associated with the element wood in the circle of Five Elements

wuxing 五行, symbolizes life, while the west is the direction associated with death and afterlife. The mirror-image of standard legible Chinese characters on the west

mubiao of the Xiao Jing tomb, thus, was not meant for the living—the visitors who pass through the spirit path to pay homage to the deceased, but for the very tomb master who was buried behind. Wu Hung argued that the mirror-image inscriptions suggest a transparent stone slab and presume a vision from the direction of the tomb, the perspective of the deceased.

30The resurrection of the vision of the dead in funeral architecture was the result of a revised understanding about life and death brought by the new faith of Buddhism. Buddhists believe death was not the end of life but a necessary step to transcend life toward enlightenment. Buddhism gained enormous popularity in south China during the Liang dynasty, whose ruling classes include the imperial Xiao clan. Xiao Jing’s cousin, Emperor Wu of Liang, was the famous Buddhist emperor who had founded numerous monasteries and personally served in Buddhist temples only to be ransomed by his courtiers to return to throne.

31 Xiao Jing himself also wrote letters in support of Buddhism.

32 In discussion of the mirror-image in the

mubiao inscriptions, Wu Hung argued, “The important point is that this reading/viewing process forces the mourner to go through a psychological dislocation from this world to the world beyond it… The discovery of the mirror relationship between the two inscriptions forges a powerful metaphor for the opposition between life and death… More important, to completely fulfill the ritual transformation, the material existence of the gate has to be rejected”.

33Indeed, the Buddhist translation of funeral architecture in China during this period made more tangible transformation of the physical structure engaging ritual activities aboveground. The

mubiao pillars were no longer replicas of timber towers in the Chinese palace, as the stone carved

que gates did in previous funeral complexes. Rather, they derived their forms from foreign Buddhist architecture. In terms of decorative motifs, sacred figures and historic scenes representing Confucian ideologies and morality were replaced by chimerical creatures both guarding the ground and soaring in the sky; architectural details imitating palatial edifices were replaced by the symbolic Buddhist image of the lotus flower. As Wu Hung observed, “a funerary gate no longer related itself to a counter-image in the living world and derived its meaning from this opposition; rather, it directly expressed the idea of transcendence and enlightenment. Most important, the mirror inscriptions on the gate completely alter the relationship between a monument and its audience: instead of presenting readable texts confirming the shared values of filial piety, they ‘reverse’ the conventional way of writing and challenge the viewer’s perception, forcing him to reinterpret a funerary monument and to view it with fresh eyes”.

34 The new monumentality after the Buddhist translation blurred the boundaries between life and death, highlighting the active process of the funeral rites rather than simply providing a static familiar living environment for the afterlife. The inscriptions along the spirit path were written for both the eyes of the living and the soul of the deceased, making a spiritual transformation for the stone and earth of the tomb structure. It is a powerful metaphor about transcendence and enlightenment.

4. The Shared Superstructure: Lingtai, Xiangtang, Mingtang, and the Pagodas

The most characteristic architectural symbol of Buddhism in East Asian is the pagoda. Translating the Buddhist relics structure into the Chinese timber building context, the

Louge 樓閣 (tower-pavilion) style

35 wooden pagoda features a multi-story tower, often with an odd number of levels each with a sloping tiled roof diminishing in both heights and width toward the top. The number of bays for each level often remain the same with the intercolumnar distances diminish as the height rises. Completing the submit of such a pagoda is the wooden axis with

chatras. Originated in China, such wooden pagodas are popular in all East Asian countries, including Korea and Japan, for instance, the 7th-century five-story pagoda from Horyuji in Nara,

36 which is the oldest extant wooden pagoda in the world (see

Figure 14). In China, three-dimensional images of early Louge style pagoda can be found in Buddhist grottoes, for instance, the 5th-century Yungang caves.

37 Although the oldest extant wooden pagoda in China, the Wooden Pagoda of Yingxian (see

Figure 15) is from the 11th century, some masonry pagodas from the Tang dynasty also mimic wooden frames in decorative details on the walls.

38Buddhist relics structures first appeared in China in the western regions along the ancient Silk Road. The region, known as

Xiyu 西域, the Western Realm, refers to a vast area west of the Hexi Corridor in today’s Gansu province, including Xinjiang in modern China and areas in many other Central Asian countries. Buddhism was first introduced to China from India via Central Asia through the ancient Silk Road.

39 In the early 20th century, Buddhist ruins were discovered by Western exploders

40 such as Marc Aurel Stein (1862–1943).

41 Since the 1950s, Chinese archaeologists made systematic surveys of Buddhist sites in Xinjiang, excavating and documenting ancient structures including stupas. These early stupas in Western China, for instance, the Mauri-tim stupa near Kashgar,

42 were often constructed with adobe. Sharing with the Indian stupa in features such as the solid core and a tripartite vertical division, however, they often had a square plan with an emphasis on the continuity from the base to the upper axis, shapes taping gradually toward the top instead of featuring a large hemispherical main body (

anda) in the middle part. They share more in common with the Central Asian, especially the Gandara region stupa from the Kushan period (1st to 4th centuries).

43 A 3rd-century stupa from the Subash monastery near Kuche has a tall square base, on top of which a cylindrical middle drum supports a domical top similar to the

anda in Indian stupa

44 (see

Figure 16). Small holes appear on different levels in the square base, the cylindrical drum, and the domical top, which suggest there might be additional wooden or ceramic surface materials attached. Compared to the Sanchi stupa, the tomb mound feature was played down and the soaring verticality was highlighted. The square base has an arch opening on one side, clearly defining a frontal façade and giving the concentric plan an axial orientation. The plan and architectural image give equal emphasis on the geometric motifs of square and circle.

45 All these features make the

Xiyu stupas closer to the ritual architecture of China and further differentiated from the Indian prototype. Similar stupas had also been discovered in other

Xiyu sites such as Miran and Khotan.

46In China Proper, the earliest wooden pagodas in the Louge Style were constructed around a rammed earth core. Professor Fu Xinian suggested that the pre-Buddhist

taixie 臺榭 tradition in Chinese architecture made it natural for the Chinese Buddhists to adopt the forms of the

Xiyu earth stupa and combine them with the Chinese wooden construction.

47 Taixie is a construction method in early Chinese architecture for building multi-level monumental structures combining rammed earth platforms with surrounding wooden structures. Wrapping wooden verandas around the lower levels of platforms and elevating wooden towers on the top, the

taixie method created an appearance of great scale and height without the actual creation of multiple-story interior space.

48 Widely discovered in archaeological sites of the Zhou (1046-221 BCE), Qin (221-206 BCE), and Han (206 BCE to 220 CE) periods, they gradually disappeared since the Medieval time.

49 Like Luo Shiping and many other scholars, Fu also believes that the high wooden towers were built for the hope to achieve immortality. The Daoist belief that immortals favored tower dwellings had contributed to the creation of the Louge Style pagoda.

50The famous nine story pagoda of the Yongning Monastery from the Northern Wei capital Luoyang was constructed with such a

taixie method. After excavation, archaeologists discovered on the site of the Yongning Monastery pagoda rammed earth platform of 20 by 20 m on top of a rammed earth base of 38.2 by 38.2 m. The upper inner platform should be the earth core for the first floor of the pagoda, which was originally surrounded by a wooden veranda; the wider lower platform should be the base of the pagoda. Based on historical records such as the

Water Classics (

Shuijingzhu 水經註), contemporary pagoda images from the Northern Wei Buddhist caves such as those form Yungang and Dunhuang, and the archaeological data, scholars reconstructed the plan, elevation, and section of this famous early wooden pagoda. Fu Xinian’s reconstruction is a nine-story pagoda with a square plan and a central pillar within a rammed earth core with wooden reinforcement. The lower seven stories are wooden verandas around earth platforms and the upper two stories are pure wooden structures. Each floor has a nine-bay façade on each side with both a sloping roof and a wooden balcony

51 (see

Figure 17).

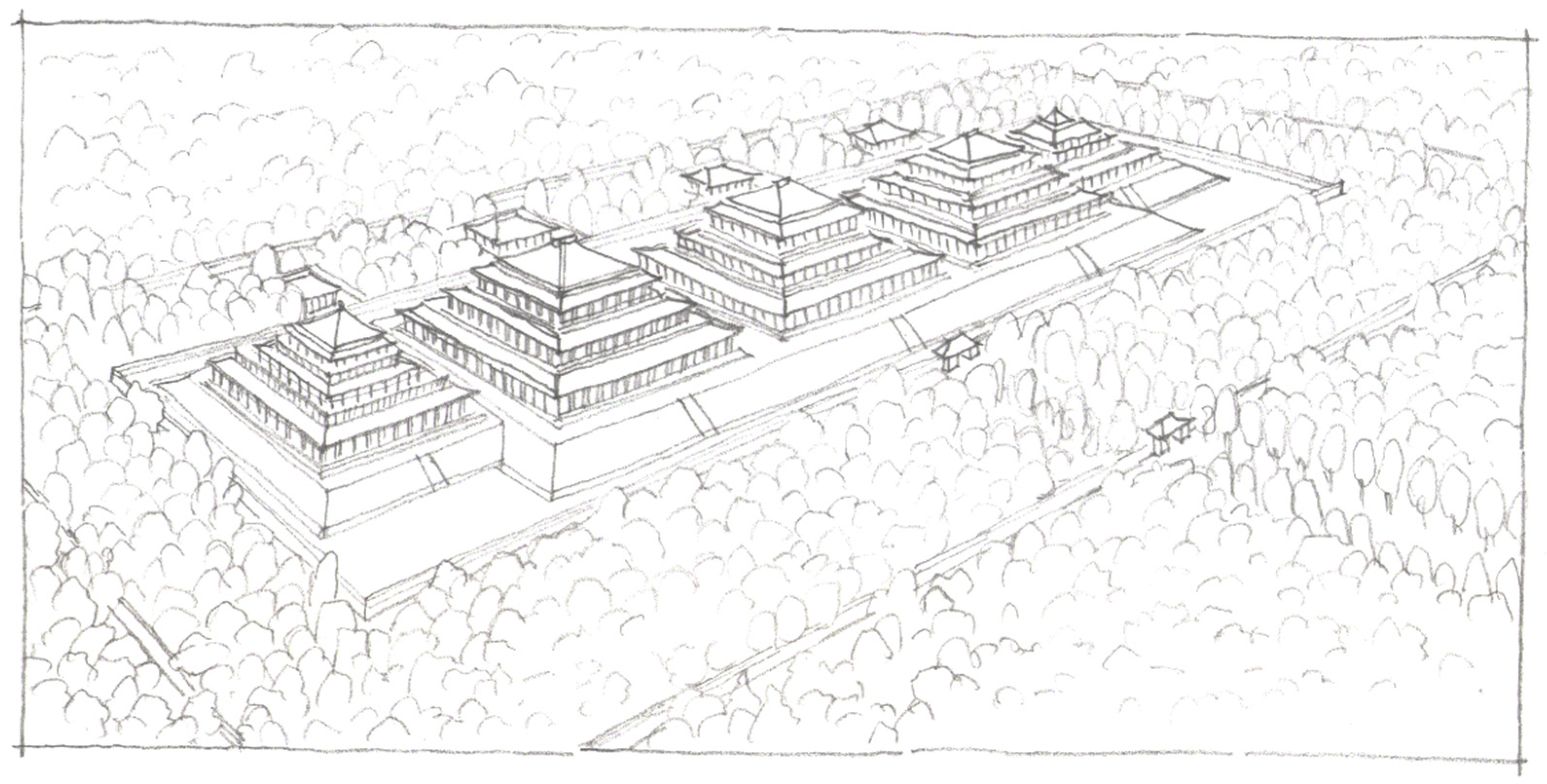

The Yongning Monastery pagoda was built in 516 and burned down in 534. Half a millennium later, rulers of a regional regime in Northwestern China, the Western Xia Kingdom, built the main structures of their mausoleums in a way similar to both the pagoda in Luoyang and the stupas along the Silk Road. In today’s Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region of northwest China, at the foot along the eastern slopes of the Helan Mountain, an area of some 50 square kilometers provides the resting places for nine rulers of the Western Xia kingdom from the late 10th to the early 13th centuries. It was not entirely clear about the identity for each of the nine royal tombs, which share the same basic plan and the same north–south orientation. Each mausoleum has two layers of walls with corner towers, defining an inner court and an outer court such as in the living cities. The outer layer has only one gate located at the center of the south wall while the inner layer has gates on all four cardinal directions. The plan has a strong axiality and is highly symmetrical. The north and south gates are located on the main north–south axis and other key elements, such as the corner towers,

quetai 雀臺 platforms, and stele pavilions, symmetrically frame the central axis on both sides (see

Figure 18). The main tomb structures, the sacrificial hall

xiandian 獻殿 and the tomb mound

lingtai 陵臺, however, are deliberately off the main axis on the west side.

52 The geometric center for the inner court is the central platform

zhongxintai 中心臺.

53Most structures in the Western Xia royal tombs were constructed with rammed earth, with the additions of bricks, paints, and glazed tiles for protection and decoration. The Tomb No. 1, which was believed to be the mausoleum for the founding ruler Taizu (Li Jiqian 李繼遷), for instance, has an octagonal rammed earth platform of nine steps, the sizes of which reduce progressively toward the top. On the base level, each of the eight sides of the octagon measures approximately 12 to 14 m. Horizontal lines of holes appear on each side of every level. The holes measure approximately 20 cm in diameter for each, which must have been the traces left by the wooden rafters supporting a tiled roof. During the archaeological excavations, large number of ceramic tiles, tile ends, animal sculptures for roof decoration, charcoal, and rotten wood were discovered on the upper steps of the rammed earth platform, as well as on the ground near the

lingtai.

54 Thus, it is highly possible that the steps of the earth platform were surrounded by wooden verandas with tiled roof, transforming the exterior of the earth platform into a wooden pagoda (see

Figure 19). Like the Yongning Monastery pagoda, the structure of wooden façades around an earth core in the Western Xia royal tombs is basically a

taixie method. Seen from the exterior, the

lingtai mound used to be a multi-story tower, with all levels featuring a sloping tiled roof diminishing in both heights and width toward the top. In a similar way as the system of Louge style Buddhist pagodas, the number of levels for each

lingtai is always an odd number, either 9, 7, or 5. The

lingtai for emperor Taizu, for example, is the highest nine story, same as the Yongning Monastery pagoda.

Unlike the pre-Buddhist Chinese tombs such as the Mausoleum for the First Emperor of Qin, the

lingtai mound in the Western Xia mausoleum is not built on top of the underground tomb chambers

mushi 墓室. Due to the damage made by earlier tomb robbers, the tomb chambers for Tomb No. 6 were revealed and archaeologists followed to make excavation and documentation. Tomb chambers are located right in front of the

lingtai, approximately 18 m to its south. Symmetrically planned with a north–south axis, the central chamber is framed by two smaller side chambers on the east and west sides, and connected with another group of chambers to its south through a corridor. South of the tomb chambers is sloping passageway

mudao 墓道, linking the floor of the underground chambers with the ground surface, which is approximately 25 m above.

55 (

Figure 20) The sacrificial hall

xiandian is very close to the entrance of the

mudao passageway. The three central parts from south to north,

xiandian, the underground

mudao and

mushi, and the

lingtai, all follow the same north–south axis, which is to the west of the main north–south axis established by the walls and gates, parallel but not overlapped. Without covering the coffins of the tomb masters in the underground tomb chambers, the functionality of the

lingtai mound is purely symbolic. Like the pagoda in Buddhism,

lingtai in the Western Xia royal tomb is not a structure to protect the physical remains of a reincarnated sentient body, but a timeless monument dedicated to the hope for a future enlightenment.

According to

Xixiaji 西夏紀, the Records of the Western Xia, the rulers of the Western Xia were descendants of the Tuoba clans of the Northern Dynasties, the imperial clan of the Northern Wei empire who built the Yongning Monastery in the 6th century.

56 Like their remote ancestors, the imperial families of the Western Xia were also Buddhists. In 1007, after his mother Wangshi 罔氏 died, King Taizong (Li Deming 李德明) sent envoys to the Song court, asking for permission to repair the ten great temples in Mount Wutai.

57 Mount Wutai was located at the border area among Song, Liao, and Western Xia then under the Song jurisdiction. It is one of the four sacred Mountains in China and revered as the seat of bodhisattva Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom. By the Tang dynasty (618–907), Mount Wutai had become one of the most important Buddhist centers in China and an international pilgrimage site, drawing Buddhist pilgrims from such faraway places as Japan and India.

58 The Song emperor responded to Li’s request by sending mourning envoys as well as sacrificial items to Mount Wutai, contributing to the religious rituals performed for Wangshi’s afterlife.

59 The Repairing or making monetary contribution for the repair of statues and buildings in temples and monasteries is a major merit for Buddhists to build up good

karma 業 for desirable future reincarnations and the eventual enlightenment. Such religious contributions were part of the funeral service for Buddhists in East Asia. The adoption of the form of Buddhist pagoda for the construction of

lingtai in Western Xia royal tombs was the result of the same intention for desirable

karmic retribution in honor of the deceased.

The Yongning Monastery pagoda is not the only prototype for the

lingtai from the Western Xia royal tombs. There was an even more remote model in Chinese funeral architecture. During the Warring States period (476–221 BCE), the kings of the Zhongshan state also built their mausoleums within two layers of rectangular walls, gated by the que towers in the middle of the southern wall.

Zhaoyutu 兆域圖, the map of the entire mausoleum complex carved in a bronze plate discovered from the very archaeological site, indicates that within the inner court, five multi-story structures were elevated on top of a shared platform (see

Figure 21). Each of the five structures features two additional concentric layers of rammed earth platforms surrounded by wooden verandas. The lower layer measures 92 by 110 m, a near square rectangle. The upper layer recedes from the lower platforms. The sacrificial hall, or

xiangtang 享堂, is built on top of the upper layer rammed earth platform. The pointed roof of the

xiangtang and the single slope roofs of the two verandas expand in size toward the lower base, forming a pyramidal profile for the tomb structure

60 (see

Figure 22) The concentric plan and multilayered verticality of the

xiangtang shared much in common with the

lingtai from the Western Xia Royal tombs, which were built more than a thousand years later. Combining a supporting earth core with a wooden frame wrapping, they were both manifestations of the

taixie structure that had been widely used for the construction of monumentality since the Zhou dynasty.

5. Buddhism and the Transformation of Chinese Funeral Architecture

The Yongning Monastery pagoda was chronologically sandwiched in-between the mausoleums for the kings of the Zhongshan state and the Western Xia royal tombs. A common feature for the three types of monumental constructions as represented by these three complexes is a ritual hierarchical order that all Chinese monumentality subscribes to. The ritual hierarchy may be expressed in the size of the walled area, the scale of the central monument, the number of buildings and gates for a complex, or the number of stories for the main tower. The Yongning Monastery pagoda has nine layers, the Great Wild Geese pagoda in Tang capital Changan has seven, and the wooden pagoda in the Ying county from the Liao dynasty has five.

61 Among the Western Xia royal tombs, the

lingtai mounds for Taizu and Taizong were nine-story tall, and the rest of them were either seven- or five-story tall, depending on the posthumous evaluations of the tomb masters by their decedents. According to the

Book of Rites, or

Liji 禮記, the Son of Heaven

Tianzi 天子 can have seven ancestral temples, a ruler of a local state

Zhuhou 諸侯 five, a minister

Dafu 大夫 three, a common aristocrat

Shi 士 one; for the elevation above the ground of the main ceremonial hall’s floor, the Son of Heaven nine feet (

chi 尺), a local state ruler seven feet, a minister five, and a common aristocrat three.

62 The legendary architecture for such a ritual system is

mingtang 明堂, the building complex where the Son of Heaven was supposed to make sacrifice to Heaven and the royal ancestors, performed the monthly rituals in different halls to harmonize the world according to the seasons, met homage-paying local rulers and court subjects, and delivered the most important edicts and lectures.

63 The structure of the Han dynasty

mingtang was also of the

taixie type, a combination of a stepped rammed earth core with an envelope of wooden frame and sloping tiled roofs.

64 Legitimizing the regime as holding the Mandate of Heaven, the construction of

mingtang is one of the most significant architectural projects a Confucian dynastic ruler would have embarked on, including the non-Chinese speaking rulers of the Northern Wei and Western Xia.

65The translation of Buddhist concepts and forms into East Asian architecture was deeply imbedded in the Confucian context. It was a process operating upon the vocabularies and grammars of various local building traditions, for which the Medieval Chinese funeral architecture bears one of the most tangible fruits. The transformation started from underground, substituting local motifs in the tomb chambers with Buddhist symbols without altering the funeral space and structures. As Buddhist concepts further incorporated into the Chinese thoughts, revised views on life and death brought new elements to the spirit path, the passageway framing active funeral rites. When, finally, the main funeral structures were given Buddhist touches, it was already hard to tell whether the Buddhist became Chinese or the Chinese became Buddhist. Like the translation of Buddhist sutras that had created new vocabularies and brought new meanings to the Chinese language, the translation of Buddhism in the built environments had also participated in the very formation of architectural traditions in China. It blurred the boundaries between Buddhist architecture and other architectural typological divisions, which were largely based on the differentiation of functionality, the “content” of architecture.

In his 1939 article “Iconography and Iconology: An Introduction to the Study of Renaissance Art”, Erwin Panofsky discussed the relationship between form and subject matter in European art and argued that on the deepest level, there is no “form as such” but just a continuous series of multilayered “contents”. He argued that “in whichever stratum we move, our identifications and interpretations will depend on our subjective equipment, and for this very reason will have to be supplemented and corrected by an insight into historical processes the sum total of which may be called tradition”.

66 In the field of architectural history, the content is often understood as the functionality of a building, practical or symbolic. The application of a split between form and content in the discussion of traditional Chinese architecture obscures the profound impact Buddhism made to the Chinese architectural tradition, in which formal consistency often overshadows the differences in content, just like the power of the Chinese characters have done to every textual translation. On the other hand, Buddhist architecture, or

fojiao jianzhu 佛教建築, and funeral architecture, or

lingmu jianzhu 陵墓建築, are often categorized as two different types in the discipline of Chinese architectural history. An uncomfortable subtype within these two categories is the pagoda, which is obviously of funeral origin but often strictly discussed under the Buddhist umbrella. The other side of the dilemma, those classified as funeral architecture but primarily constructed and decorated within the Buddhist contexts, is often neglected, remaining a blind spot unable to be recognized as a discomfort at all. The uncovering of such categorical discomfort as imbedded in Buddhist vs. funeral architecture is meaningful for a fuller understanding of Chinese architecture as, like what Panofsky said, the “historical processes” and “the sum total of which may be called tradition”. It is an index of the great impact that the introduction of Buddhism had on Chinese architecture, like Xuanzang’s translation of the

Prajnaparamita Sutra 波若心經, which has become inseparably Buddhist and Chinese.