Abstract

The sea surface microlayer (SML) is a critical biogeochemical boundary, playing a key role in air–sea exchange processes, yet its sampling remains challenging due to potential dilution from subsurface water layers, susceptibility to contamination and labor- and time-consuming procedures. The design, development and operational verification of a research unmanned surface vehicle (USV), equipped with samplers for collecting both sea surface microlayer and subsurface water samples (SSW), are described in this study. The InterSeA autonomous vessel is of the catamaran type, equipped with an SML sampler consisting of rotating glass discs and a peristaltic pump for collecting SSW samples. Verification analysis with traditional manual sampling techniques (glass plate and mesh screen) revealed that the InterSeA achieved comparable results in terms of reproducibility and contamination control for both the inorganic and organic analytes examined. The results obtained highlight the effectiveness of autonomous platforms in achieving reliable, low-contamination SML sampling, emphasizing their suitability for broader use in marine biogeochemical research demanding high resolution and minimally disturbed interface measurements. InterSeA is one of the smallest and lightest USVs using rotating glass discs for SML sampling.

1. Introduction

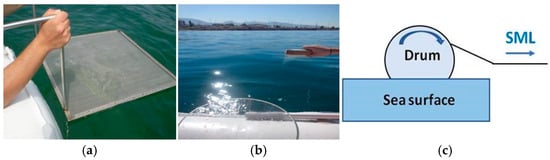

The sea surface microlayer (SML), characterized by high irradiation and temperature variability [1], represents the critical interface between atmosphere and hydrosphere, where a high amount of organic material is concentrated [2,3]. It constitutes a thin, gel-like structure, significantly different from the underlying subsurface water (SSW) layers [4,5,6]. With a typical thickness lower than 1 mm, the SML comprises a unique combination of chemical, physical and biological properties, making it a water compartment worth studying [7,8,9]. Despite the fact that the SML plays a key role in the global distribution of anthropogenic pollutants [10,11] and controls environmental processes such as material and energy exchange between air and sea surface [12,13], studies of the SML still remain limited due to its particularly labor- and time-consuming sampling procedures. Traditional methods of SML sampling have been employed for decades, including techniques such as the mesh screen sampler [14], glass plate sampler [15] and rotating drum sampler [16] (Figure 1). These methods are characterized by their own challenges, particularly regarding the difficulty in obtaining representative samples. The mesh screen sampler, while useful for collecting larger water volumes [17], typically captures a thick water layer, diluted with underlying subsurface water, hence hindering the isolation of the real SML composition [18]. Despite providing representative and thin SML samples, the glass plate method is labor-intensive and time-consuming, based on the manual collection of small sample volumes [18]. The rotating drum method (usually installed on small vessels), although collecting large sample volumes, still faces limitations in accurately capturing the thin and dynamic SML nature, particularly in areas where turbulent conditions prevail [19].

Figure 1.

Mesh screen sampler (Garrett type) (a), glass plate sampler (Harvey and Burzell type) (b) and rotating drum sampler (c) (photos by S. Karavoltsos).

Rotating glass discs, which constitute a combination of a glass plate and a drum, appear advantageous over rotating drums, achieving better vessel navigation, due to their reduced surface area [20]. Unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) offer a platform for the collection of reliable datasets, contributing to several monitoring strategies, offering enhanced temporal and spatial coverage over specific timeframes and allowing for targeted examination of sites or events of interest [21]. The navigation accuracy of USVs is constantly improving [22,23]. With their ability to collect data from areas that are typically hard to reach, such as protected or ecologically sensitive zones, USVs are a valuable research platform for monitoring marine ecosystems and assessing the impact of pollutants. Therefore, for the study of the marine SML, the installation of rotating glass discs on a USV vessel offers several advantages, including high-frequency and continuous SML sampling, minimal disturbance of the air–sea interface and controlled and repeatable sampling conditions. It reduces human contamination and safety risks, also permitting simultaneous measurements with onboard sensors, enhancing the spatial and temporal resolution of SML observations.

The first attempt to use rotating glass discs on an autonomous vessel was implemented at the Institute of Ocean Sciences (Sidney, British Columbia, Canada) [20]. The platform employed consists of two fiberglass hulls (1.5 m long, 0.5 m wide, 0.5 m deep) connected by an aluminum frame that supports propulsion, scientific instrumentation and control electronics. The sampling system employs ten rotating glass discs (thickness 0.3 cm) spaced 5 cm apart. The discs are mounted between the bows of the two hulls, parallel to the sea surface and perpendicular to the direction of travel. A dual collection system allows simultaneous sampling of SML and SSW water from 1 m depth, with samples stored in twelve 250 mL bottles installed on an automated carousel.

The Sea Surface Scanner (S3) is another remotely operated catamaran with a length of 4.5 m and a width of 2.2 m. It integrates six partially submerged rotating glass discs (diameter 60 cm, thickness 0.8 cm) mounted between the bows of the hulls. In parallel, the system continuously collects underlying water from 1 m depth [24].

HALOBATES, the most recent autonomous USV for SML studies, is a catamaran type vessel of 6.20 m length and 2.30 m width, with a hull separation of 1.14 m. It uses a sampling system of six partially immersed rotating glass discs (diameter 60 cm, thickness 0.8 cm) mounted between the hulls. The sampling system is fully automated, incorporating a flow-through CTD to detect temperature and salinity gradients and an ADCP to measure the high-resolution velocity field and meteorological sensors. Discrete water samples from the outflow of the CTDs can be collected for laboratory analysis of chemical analytes such as surface active substances (SAS) [25].

The aim of this study is to (a) develop a compact USV-based SML sampler and (b) verify its performance through a direct comparison with traditional hand-held methods (glass plate and screen mesh samplers).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Development of SML and SSW Samplers

In the development phase of the SML sampler, glass discs were preferred to a drum configuration based on their operational and practical advantages. Due to the USV’s movement, employing glass discs significantly minimizes SML disturbance in comparison to drums—for which the surface in contact with the sea surface is larger [24]. Their lower weight is also favorable, considering the payload limitations of the research vessel. Moreover, glass discs can be readily manufactured locally, whereas the procurement of a glass drum requires a specialized order, typically delivered within considerable time scales. An initial prototype was therefore developed in the lab, consisting of glass discs vertically immersed in water.

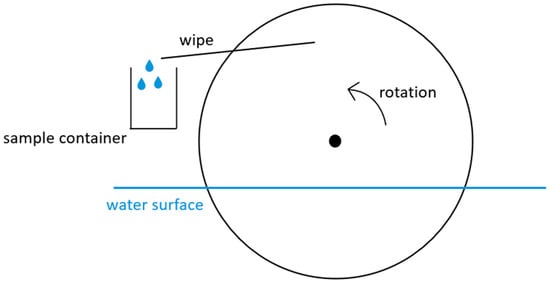

Τhe prototype model initially designed by the research group of the Laboratory of Environmental Chemistry of NKUA consisted of three (3) circular glass discs of 30 cm diameter, partially immersed in water (Figure 2). The SML drops adhering onto the ascending side of each rotating disc, due to the physical phenomenon of surface tension, are collected by wipers inclined to both sides of each disc, directing the collected water into a precleaned container. The wipers are constructed of Teflon foil (a particularly chemically inert material) of 0.2 mm thickness. They are adjusted to a rigid structure, after being slightly bent, to be placed between the glass discs. When released from their fixed position, the Teflon foils tend to obtain their initial flat shape, which permits their constant contact with the discs on both sides. As a result, during their rotation, the discs are continuously in contact with the Teflon wipers, with resistance due to friction being quite low. Teflon wipers were placed in the sampling system prior to each sampling.

Figure 2.

Circular rotating glass disc of the SML sampler.

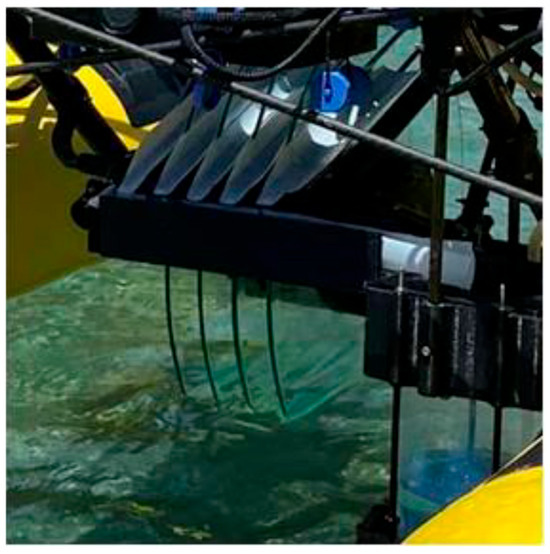

The USV platform selected for installing the SML sampler was the iUSV-170 (Intelligent Machines, Rio, Greece), described briefly in Section 2.2. The SML sampler was redesigned and mounted to the underside of the USV, without affecting the vessel stability or navigation performance. The constructed sampler consists of four parallel circular glass discs, each 40 cm in diameter and 0.5 cm in thickness (Figure 3). The discs are immersed partially in the water and rotate slowly, driven by an electric motor. Teflon wipers are installed to enable efficient collection of water droplets, adhering to the upward-moving side of each disc, also allowing their rapid removal for cleaning, maintenance, or replacement. The SML sample collected by the wipers is directed to a Teflon collection channel, which guides the flow towards a 2.2 L container used for sample storage. This configuration ensures efficient and uncontaminated transfer of the SML sample from the discs to the collection reservoir.

Figure 3.

SML sampler installed on the USV vessel.

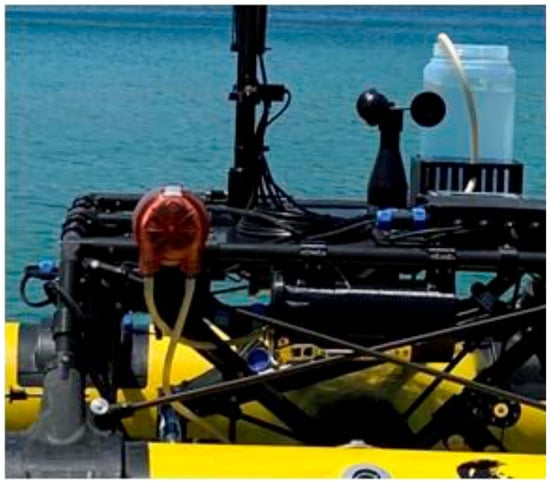

The collection of SSW samples is essential for obtaining paired datasets with the SML, enabling direct comparison between the SML’s properties and those of the underlying water column. Requirements for paired sampling arise from the fact that the SML constitutes a physically, chemically and biologically distinct environment compared with the underlying water, even at few centimeters below [3,4,26]. The integrated SSW sampler consists of a programmable automated peristaltic pump EZO-PMP-L (Atlas Scientific, Long Island City, NY, USA) (Figure 4), the inlet tubing of which is submerged at a depth of 20 cm below the water surface [18]. This configuration enables the collection of SSW samples, thereby supporting robust paired analyses between SML and SSW properties.

Figure 4.

Peristaltic pump for subsurface water (SSW) collection.

SML and SSW samples are transferred into containers, which are placed on the vessel in a configuration that ensures its balance and stability during navigation (Figure S1, Supplementary Material). Samples subject to organic compound analysis are collected in 2 L dark glass bottles. For trace metals, wide-mouth 2.2 L FEP bottles (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) are used.

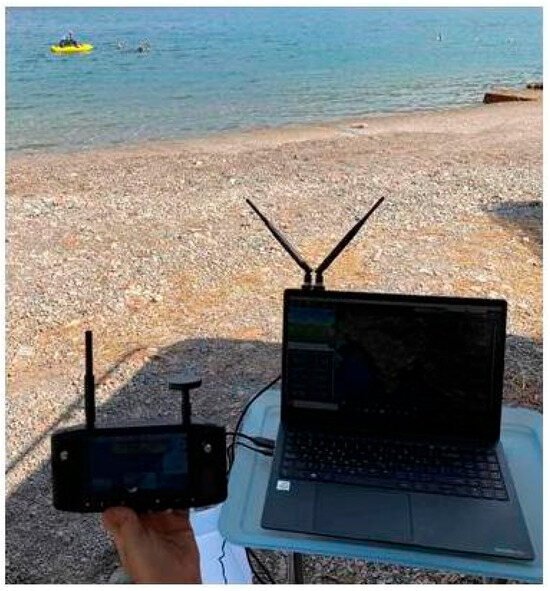

For remote operation of the SML and SSW sampling subsystems, the USV central processing unit and control interface were programmed with an appropriately developed software code. The system supports two operational modes (Figure 5): (i) an autonomous mode, in which predefined mission sequences are uploaded to the USV and executed automatically at designated waypoints and (ii) a manual mode, allowing direct real-time control through the remote joystick-based controller. Both modes allow full management of the SML disc-rotation mechanism and the SSW peristaltic pump, including activation, deactivation and adjustment of operational parameters. During autonomous missions, the software at the ground station (laptop) provides real-time monitoring of navigation data, sensor outputs and sampler status messages, ensuring synchronized operation of SML and SSW samplers throughout the transect. Manual mode further enables the operator to fine-tune sampling procedures on demand, adapting vessel speed, heading and sampling duration to local conditions.

Figure 5.

Joystick and laptop for the remote navigation of the USV and samplers.

2.2. USV Platform

The SML and SSW samplers were both installed on a catamaran-type USV (Figure 6), consisting of floating and ground parts. Regarding the floating part, the vessel, which consists of two inflatable floats made of Hypalon neoprene, is 170 cm long, with a width of 60 cm, a deck surface area of 50 cm × 40 cm and a payload of approximately 15 kg. Its mechanical parts also comprise the frame from carbon fibers, four (4) lateral motors, two rechargeable lithium-ion batteries (18 Ah/14.8 V) installed outboard and abreast of the vessel (Figure S2) and basic electronic navigation and control systems. The maximum energy autonomy of the system is 3.5 h. GPS (RKT GNSS; GLONASS, Galileo, BeiDou, QZSS) and Telemetry subsystems are responsible for USV navigation, the range of which was tested up to 5.5 km. An autopilot compatible with Pixhawk 4 is used. The vessel also includes 3 gyroscopes, 3 accelerometers and 3 magnetometers. The vessel was equipped, specifically for SML sampling, with sensors for wind speed and solar irradiation measurements (Figure S3).

Figure 6.

Unmanned surface vehicle (USV) equipped with SML and SSW samplers.

The ground part of the system includes the remote control joystick/tablet, which is responsible for USV navigation and telemetry (transfer of data on USV operation) and the ground station which runs the software Mission Planner v.1.3.80, used for controlling all parameters of USV operation, defining autonomous missions and displaying real-time data from wind and solar irradiation sensors and real-time messages for the operation of SML and SSW sampling subsystems.

The USV is equipped with two sensors (anemometer and solar irradiation sensor) to continuously monitor wind speed and solar irradiation intensity, which are important parameters for SML sampling [27]. Both sensors provide real-time data streaming directly to the ground station. Continuous monitoring ensured that transient changes in environmental forcing could be captured and accounted for in the interpretation of SML variability. The use of real-time data streaming also facilitated operational decision-making during the campaigns, such as adjusting the USV position to maintain optimal sampling conditions or avoid high-turbulence events.

2.3. InterSeA Sampling Characteristics

According to Shinki et al. [20], using a water solution with 40 ppt NaCl, there is no pronounced difference in the thickness at rotation speeds between 3 and 15 RPM. A rotation speed of 8 RPM was selected for the InterSeA SML sampler, balancing the need for sufficient collection and minimal mechanical disruption. Higher speeds may introduce turbulence disturbing the SML structure, whereas lower reduce volumetric collection and temporal resolution. At 8 RPM, the sampler collects around 4.2 L h−1 of SML water, depending mainly on the state of the sea surface, the quantity of SAS on the water surface and salinity. SSW is collected using a peristaltic pump, which draws 2 L within a 5 min interval. The thickness of the SML collected by the rotating discs was calculated using the measured volumetric collection rate and the effective surface area of the discs (~1500 cm2), yielding an estimated thickness of approximately 50–80 µm, comparable to the calculated thickness of approximately 80 μm stated by Shinki et al. [20].

HALOBATES USV, equipped with six partially submerged glass discs (diameter 60 cm) rotating at 10 RPM, collects approximately 20 L h−1 of SML of average thickness comparable to that of InterSeA [25]. A similar disc-based approach is employed by the S3, using six glass discs (diameter 60 cm) rotating between 6 and 10 RPM (typically 7 RPM), achieving a comparable sampling rate of around 20 L h−1 corresponding to an SML thickness of 50–80 μm [24]. Another disc-type sampler, developed at the Institute of Ocean Sciences (Sidney, BC, Canada), comprising ten thin glass discs with Teflon wipers, is reported to collect SML of an approximate thickness of 80 μm (rotation speed 5 cm s−1, salinity 40 ppt), using optical techniques [20].

2.4. Verification of InterSeA in SML Sampling

The principal objectives of this task comprised testing of the effectiveness of the InterSeA autonomous vessel in the framework of an SML sampling process, the comparison of the InterSeA sampling procedure with the “traditional” techniques namely a Harvey-and-Burzell-type glass plate and a Garrett-type mesh screen sampler. SML samples were collected simultaneously by these three sampling techniques, while SSW samples were collected both manually and using the USV peristaltic pump. For the manual collection of both SML and SSW samples, a small rubber boat was used equipped with an electric motor. During sampling, the small boat was in proximity to InterSeA at a distance of around 20 m. Sampling started simultaneously on the two vessels and a brief break was required to replace the SML sample collection container on the USV. Upon completion of sampling, the SML samples of the USV were consolidated.

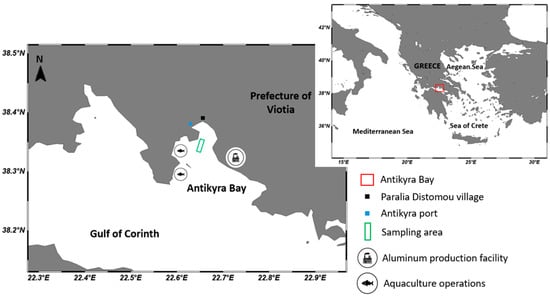

2.4.1. Study Area and Physicochemical Parameters

A complete sampling campaign was performed on two consecutive days (25–26 June 2024) at Antikyra bay, a semi-enclosed coastal system located along the northern coastline of the Gulf of Corinth, in Viotia, Central Greece (38.37° N, 22.64° E) (Figure 7). The bay is surrounded by large mountains blocking the north wind, so calm conditions frequently prevail on the sea surface. The surrounding area is impacted by a large-scale aluminum production unit, agricultural runoff, urban effluents and extensive aquaculture facilities.

Figure 7.

Study area (SChlitzer, R., Ocean Data View, odv.awi.de).

The containers used for the collection of samples were thoroughly cleaned with ultrapure water of 18.2 MΩ cm (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), filled with 10% nitric acid supra pure for several days and subsequently rinsed with ultrapure water and seawater from the sampling site prior to sampling. Samples for n-alkanes, PAHs, Chlorophyll-α and OC analysis were collected in dark glass containers, while those for trace elements were collected in FEP ones.

Prior to their use, all samplers were rinsed with ultrapure water, while sample collection started after the first five dips of the plate and mesh screen into seawater and operation of the InterSeA sampler for a few minutes for conditioning purposes. The parameters of wind speed (m s−1) and irradiance (W m−2) were measured by the sensors employed on InterSeA, while the physicochemical parameters of pH, temperature (°C) and salinity (ppt) were measured in situ from the rubber boat with a YSI Pro1030 pH/conductivity meter (YSI, Brannan Lane, OH, USA), equipped with a frequently calibrated electrode. Air temperature was recorded with a DO9721 (probe LP9021) quantum photo-radiometer (Delta Ohm, Padova, Italy). Seawater temperature, pH, and salinity were measured in the underlying water (20 cm depth of the water column).

2.4.2. Chemical Analyses

For the comparison among the three SML sampling techniques applied—the InterSeA autonomous vessel, the Harvey-and-Burzell-type glass plate and the Garrett-type mesh screen sampler—a targeted set of chemical analyses was selected, including suspended particulate matter (SPM), dissolved organic carbon (DOC), Chlorophyll-α (Chl-α), trace metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and n-alkanes.

SPM was measured by filtering the samples through pre-weighed cellulose mixed ester membrane filters (0.45 μm pore size; 47 mm diameter) on site. The retained particulate material was quantified by the weight difference, after weighing the filters once dried to constant weight. DOC was measured using the high-temperature catalytic oxidation (HTCO) method, based on the procedure described by Sugimura & Suzuki [28], employing a TOC-5000A Shimadzu analyzer (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD, USA). The precision was estimated as the standard deviation (SD) between injections, and was less than 2% of the mean. For Chl-α analysis, 800 mL of seawater was filtered through a Whatman GF/F filter. The filters were then placed in 10 mL of 90% acetone and left in the dark for 16 h, according to the method of Strickland and Parsons [29]. Chl-α concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically using a Specord 210 Plus UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany).

Trace elements (Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Mn, Ni, Pb and Zn) were measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) employing a Thermo Scientific ICAP Qc (Waltham, MA, USA) instrument [30,31], following pre-concentration using the Toyopearl AF Chelate 650 M resin [32]. Briefly, pre-concentration was performed using a semi-automated, off-line extraction system involving a micro-column packed with the resin and a flow manifold. Approximately 30 mL of each sample passed through the column using a peristaltic pump. The metals retained on the resin were then eluted with 1 M Suprapur HNO3 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), achieving a tenfold concentration factor. Measurements were carried out in a single collision cell mode, with kinetic energy discrimination (KED) using pure He. All sample preparation and pre-concentration steps were conducted inside a room of controlled environmental conditions. Analytical blanks showed low background levels and no blank corrections were applied. To verify the accuracy and precision of the method, seawater samples from the QUASIMEME inter-laboratory exercise were used, with the recovery exceeding 85%. The limits of detection (LODs) in μg L−1 were calculated equal to 0.001 for Cd, Co, 0.002 for Pb, 0.003 for Ni, 0.005 for Cu, Cr and Mn and 0.02 for Zn.

The determination of n-alkanes (C7–C40) and sixteen US EPA priority controlled PAHs, namely naphthalene (NP), acenaphthylene (ACY), acenaphthene (ACE), fluorene (FL), phenanthrene (PHE), anthracene (ANT), fluoranthene (FLA), pyrene (PYR), chrysene (CHR), benzo[a]anthracene (BaA), benzo[b,k]fluoranthene (BbkF), benzo[a]pyrene (BaP), dibenzo[a,h]anthracene (DahA), indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene (IcdP) and benzo[g,h,i]perylene (BghiP), was carried out according to the methods described in detail in Karavoltsos et al. [33] and Sakellari et al. [34], respectively. Briefly, dissolved n-alkanes and PAHs were extracted from seawater by liquid–liquid extraction with diChloromethane, extracts were gradually concentrated to a final volume of approximately 500 μL and following a solvent change and a purification step, the determination was performed by an Agilent (Santa Clara, CA, USA) 6890N Gas Chromatographer coupled to a 5975C Mass Spectrometer operating with EI (electron ionization), using the selected ion monitoring mode (SIM). Analyte recoveries from spiked samples ranged from 67% to 116% for n-alkanes and from 73% (FL) to 112% (CHR) for PAHs. The LODs for n-alkanes and PAHs determination are presented in Tables S1 and S2, respectively. For statistical calculations, values below the LOD were assigned the limit of detection divided by √2.

2.4.3. Statistical Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 30.0 was used for all statistical tests performed (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). t-test and one-way ANOVA were used to statistically compare values between two groups and more than two groups, respectively. The tests were two-sided and p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Parameters

During sampling campaigns in Antikyra bay, the SSW samples exhibited relatively stable values of the physicochemical parameters reported (Table 1). pH values ranged from 8.01 to 8.06, while temperature ranged from 25.5 °C to 26.1 °C among the samplings. Salinity values demonstrated slight variations, ranging from 37.0 to 37.5 ppt, typical of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Table 1.

Environmental and physicochemical parameters in Antikyra bay during sampling campaigns.

The USV is equipped with sensors to measure wind speed and solar irradiation intensity. Wind speed is a critical parameter and should be <6 m s−1 for the formation of a well-organized SML and the collection of representative SML samples [35,36]. Wind speed was recorded at ten-minute intervals throughout the two-day field campaign. Mean surface wind speeds recorded on the first (25 June 2024) and second sampling days (26 June 2024 samplings I and II) were 2.1, 1.4 and 1.6 m s−1, respectively. Solar irradiation mean values were 920.1, 795.8 and 816.4 W m−2, respectively, depending on the exact sampling time of the day.

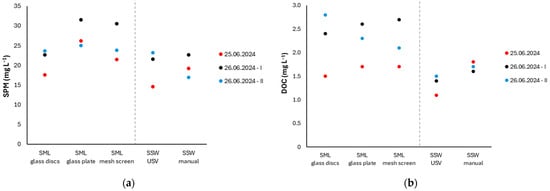

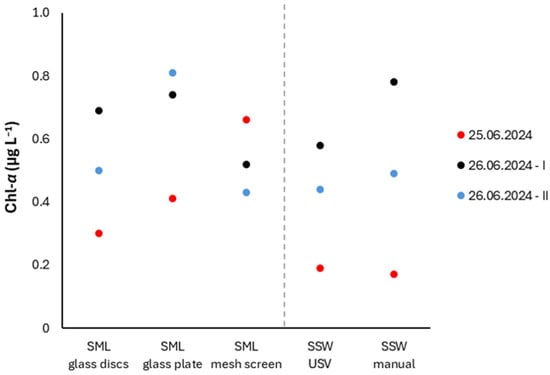

3.2. SPM, DOC and Chl-α

The SPM, DOC and Chl-α concentrations are presented in Figure 8 and Figure 9. Due to the general enrichment of the SML, relative to SSW, the corresponding enrichment factors (EFs) are also reported (Table S3), defined as the ratios of SML to corresponding SSW concentrations (EF = CSML/CSSW) [4,37]. SML samples were collected using (i) the rotating glass discs of InterSeA USV (SML glass discs), (ii) a Harvey-and-Burzell-type glass plate (SML glass plate) and (iii) a Garrett-type mesh screen (SML mesh screen). SSW was sampled: (i) autonomously, using the peristaltic pump installed on the InterSeA USV (SSW USV); (ii) manually, immersing the sample container to a depth of approximately 20 cm (SSW manual).

Figure 8.

Concentrations of SPM (a) and DOC (b) across different sampling techniques.

Figure 9.

Concentrations of Chl-α across different sampling techniques.

The SPM concentrations measured in the SML through glass discs ranged from 17.6 to 23.6 mg L−1 (mean concentration ± SD: 21.3 ± 2.6 mg L−1). Slightly higher values were obtained using the glass plate (25.0–31.5 mg L−1, 27.6 ± 2.8 mg L−1) and mesh screen (21.5–30.5 mg L−1, 25.3 ± 3.8 mg L−1) (Figure 8a), albeit with no statistically significant differences among the samples (p = 0.13; one-way ANOVA). The SML generally demonstrated quite a low enrichment in SPM. The mean EFs calculated during the sampling campaigns were slightly higher when the two hand-held techniques were employed (EF = 1.4 ± 0.1 for glass plate and 1.3 ± 0.1 for mesh screen), compared to glass discs (EF = 1.1 ± 0.1). Although small, this difference may be attributed to reduced disturbance and trapping of subsurface material, since collection with glass discs is performed under a constant rotation speed. Glass plate samplers variably adsorb or disturb deeper water layers, depending mainly on the withdrawal speed of the plate from the water and the sea state, potentially leading to overestimation of SPM concentrations. USV controlled mechanical sampling ensures more precise targeting of the microlayer, minimizing such artifacts [18]. The SPM concentrations reported in Barcelona and Banyuls-sur-Mer (Gulf of Lions; Ligurian Sea) ranged between 9.7 and 33.3 mg L−1 and 10.0–15.5 mg L−1, respectively [38].

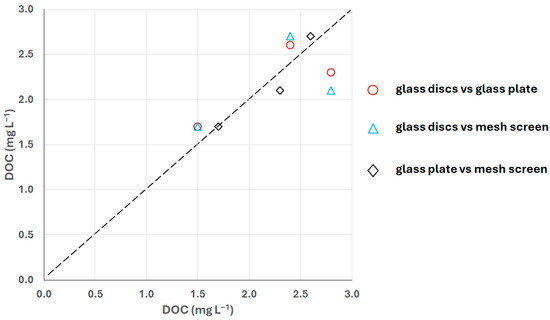

The DOC concentrations measured in the SML, for which a mean value of 2.2 mg L−1 was calculated (SML glass discs: 2.2 ± 0.5 mg L−1, SML glass plate: 2.2 ± 0.4 mg L−1, SML mesh screen: 2.2 ± 0.4 mg L−1), did not vary noticeably among the sampling techniques employed (p = 0.31, one-way ANOVA) (Figure 8b). It is demonstrated that the glass disc method provides effective and uncontaminated sampling of the organic-rich SML. Despite the different sample thicknesses obtained with the different techniques employed, the consistency observed indicates a relatively stable and homogeneous organic structure of the SML in the study area. This lack of significant discrepancies suggests that the dilution effect, typically expected when thicker samples are collected by mesh screens, was negligible. DOC is vertically distributed along a relatively thick layer, rather than confined to a microlayer thinner than the minimum thickness sampled [39].

Chl-α concentrations exhibited slight variations among the different SML sampling techniques employed, however statistically insignificant (p = 0.31, one-way ANOVA) (Figure 9). Concentrations corresponding to glass discs samples were generally exceeded by those corresponding to the glass plate, particularly during the last sampling (0.50 and 0.81 μg L−1, respectively). The mean EF of the SML calculated for the case of glass discs was 1.3 ± 0.2, whereas those obtained through hand-held sampling techniques exhibited greater variability (glass plate: mean EF = 1.7 ± 0.6, mesh screen: 1.8 ± 1.5), attributed to the significant enrichment (EF > 2) of the SML in Chl-a detected in the first sampling, including hand-held sampling techniques (ΕF = 2.4 and 3.9 for the glass plate and mesh screen, respectively). The distinct behavior of Chl-α from that of DOC across all samplings is attributed to differences in their vertical distribution within the water column.

3.3. Trace Metals

Samples collected using the mesh screen were excluded from metal analysis due to their contact with the metallic material of the sampler. The comparison between the glass discs of InterSeA and the glass plate method demonstrated comparable concentrations of Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Mn, Ni, Pb and Zn (p < 0.05; paired t-test) in the SML over the three sampling campaigns carried out (Table 2). This aligns with the fact that the specific sampler types collect SML samples of similar thickness; hence, no variations are expected. In SSW samples, the metal concentrations were also comparable (deviation of mean concentrations <10%), with the exception of Cr and Ni for which higher concentrations were measured in glass discs and the glass plate, respectively (deviations of 27 and 51%, respectively).

Table 2.

Concentrations of dissolved trace metals (μg L−1) and their enrichment factors (EFs) in SML and SSW across different sampling techniques.

Trace metal concentrations with their respective EFs have been previously reported for SML samples obtained using the glass plate method from the coastal zones of the Elefsis and Evoikos gulfs, within the Aegean Sea, Greece, significantly impacted by industrial activities [30]. The dissolved metal concentrations in the SML of Antikyra bay in the present study were higher than those of the Elefsis and Evoikos gulfs for Cr (deviation of mean concentrations 60%), Mn (76%) and Zn (65%), while for the rest of the metals examined the metal levels in Antikyra bay were lower. The same trend was observed in the comparison of SSW metal concentrations, with higher values recorded in Antikyra compared to the Elefsis and Evoikos areas for Cr, Mn, Ni and Zn (deviation of mean concentrations 180, 970, 52 and 183%, respectively). It is evident that the main sources of Cr, Mn and Zn in the Antikyra area are related to metal sources in SSW instead of aerosol inputs. The alumina plant operating in the coastal area impacts the aquatic ecosystem metal balance through the discharge of red mud [40], while the decomposition of organic matter deriving from intensive local aquaculture activity can create localized low-oxygen (anoxic) zones, boosting Mn release from sediments. It has been demonstrated that within areas comprising aquaculture units, a consistent pattern is formed between sediment composition in metals and fish feed metal content, with Mn and Zn accounting for the highest proportions (>60%) [41].

3.4. PAHs and n-Alkanes

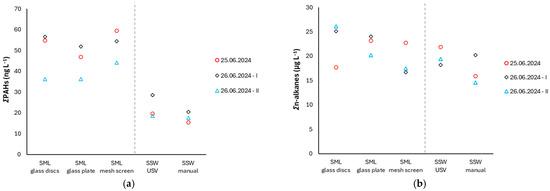

The sum of the concentrations of the 16 US EPA priority dissolved PAHs indicates that the three SML sampling techniques applied yielded similar concentration ranges (p = 0.62; one-way ANOVA) (Figure 10a, Table S4).

Figure 10.

Concentrations of ΣPAHs (a) and Σn-alkanes (b) across different sampling techniques.

Dissolved ΣPAH concentrations in the SML of Antikyra bay (glass discs: 49.2 ± 9.2 ng L−1, glass plate: 45.0 ± 6.5 ng L−1, mesh screen: 52.7 ± 6.4 ng L−1) and SSW (glass discs: 22.3 ± 4.5 ng L−1, manual: 17.8 ± 2.0 ng L−1) demonstrate moderate contamination. Slightly elevated concentrations in mesh screen samples reflect different sampling thickness and phase-specific selectivity. According to Guitart et al. [42], the mesh screen typically retrieves thicker SML samples compared to glass plates, potentially resulting in different partitioning of the pollutants. While glass surfaces are more efficient in colloidal phase collection, metal screens exhibit higher efficiency in capturing the “truly dissolved” PAH fraction. In a previous study in Saronicos gulf, Greece, close to a highly industrialized coastal zone, the average concentrations of dissolved ΣPAHs (sum of 16 PAHs) in the SML of two sites were 137 ± 72 ng L−1 and 122 ± 56 ng L−1 and in SSW 137 ± 72 ng L−1 and 122 ± 56 ng L−1, respectively [34]. In the NW Mediterranean, at two contrasting locations, one urban off Barcelona, Spain, and another comparatively clean, off Banyuls-sur-Mer, France, ΣPAHs (sum of 15 PAHs) in the SML were measured as equal to 24.1 ± 9.8 ng L−1 and 13.1 ± 8.1 ng L−1 and in SSW 11.3 ± 7.7 ng L−1 and 8.1 ± 2.8 ng L−1, respectively [38]. Data reported in the literature demonstrate that contamination of the marine environment with PAHs increases in areas where anthropogenic coastal activities occur, such as harbors, shipping and operation of local industries [2], also confirmed for the Antikyra bay area.

The sum of n-alkanes (C7–C40) concentrations measured in glass disc SML samples (23.0 ± 3.7 μg L−1) spanned a wider range compared with those obtained using the glass plate (22.5 ± 1.6 μg L−1) and mesh screen (19.0 ± 2.7 μg L−1), albeit with no significant statistical differences among the three samplers (p = 0.36; one-way ANOVA) (Figure 10b). The concentration levels detected in this study area are significantly higher than those reported for pristine marine environments such as the Gerlache Inlet in Antarctica, where n-alkanes (C15-C32) in the SML ranged between 152 and 382 ng L−1 [43]. This difference highlights the impact of regional anthropogenic activities and terrestrial inputs on the dissolved alkane load. However, the concentrations of n-alkanes reported herewith are lower than those recorded in Barents and Kara Sea, especially during ice melts, due to freshwater inputs [44].

4. Discussion

The quite low enrichment of SPM in the SML in Antikyra bay, employing three different samplers, is in agreement with SPM concentrations reported in Barcelona and Banyuls-sur-Mer (Gulf of Lions; Ligurian Sea) (mean EF = 1.8 ± 0.83 and 1.1 ± 0.68), respectively, using the Garrett-type mesh screen as a sampling technique [38].

A slight enrichment of the SML in DOC is reported, using glass discs, a glass plate and a mesh screen (no statistically significant difference of EFs from unity, p = 0.069, 0.286, 0.371, respectively, one-way t-test). Also, limited variation was observed (mean EF = 1.6 ± 0.3, 1.3 ± 0.3, 1.3 ± 0.3, respectively) among the sampling campaigns carried out, irrespective of the sampling technique employed (Table S3). A similar range of EFs was reported by Carlson [39,45], who showed that the SML was generally only moderately enriched in DOC, relatively to underlying water, with EFs typically close to unity and rarely exceeding two, employing both a glass plate and a mesh screen. This further supports the hypothesis that the organically enriched layer was thicker than the effective sampling depth of the plate. As noted by Carlson [45], when a fivefold difference in sample depths between plates and screens does not result in significant deviations in enrichment, the enriched layer is deep enough to prevent dilution of the thicker screen samples.

Figure 11 presents the correlation of DOC concentrations in the SML among the different sampling techniques used. The glass plate showed the highest consistency with the mesh screen, although a different thickness of SML sample is collected. However, the deviation observed in the results between glass discs and hand-held techniques (Figure 11) is less than 20%, while it is 33% only in the third sampling campaign. The lack of discrepancies indicates a continuous microlayer structure, where physical disruption—from either wind or the sampling process itself—was insufficient to erode the surface [45]. A similar pattern was reported by Wurl et al. [25], who observed deviations of less than 25% in SAS concentrations when samples collected with the glass plate and HALOBATES USV were compared. The differences were attributed to SML thickness, which is highly dependent on the glass plate withdrawal speed [25].

Figure 11.

Concentrations of DOC in samples collected from glass discs of InterSeA vs. Harvey-and-Burzell-type glass plate sampler, glass discs vs. Garrett-type mesh screen sampler and between glass plate and mesh screen. The dashed line represents a 1:1 line, i.e., a perfect match of concentrations collected by the samplers.

While DOC enrichment remains relatively stable, regardless of the sampling technique, Chl-α shows high sensitivity. This discrepancy aligns with the observation that particulate materials are often confined to thinner layers, whereas DOC is distributed over relatively thicker layers. The variability of the mesh screen (EF 0.7–3.9) reflects the heterogeneous distribution of Chl-α, leading to sporadic high enrichments when a slick is present or to depletions when the sampler integrates more bulk water [39]. The automated nature of InterSeA facilitates an homogenized sampling approach, yielding higher data reproducibility by avoiding the fluctuating enrichments and depletions observed in hand-held sampling techniques; it avoids the “extreme values” that characterize plate and screen samplers, still capturing the potential enrichment.

Regarding dissolved trace metals in Antikyra bay, the EFs calculated employing glass discs were close to or below unity (p > 0.05; one-way t-test), indicating an insignificant SML enrichment. In the Elefsis and Evoikos gulfs, two highly industrialized areas, a higher SML enrichment was calculated for most metals [30]. In a coastal area of the western Mediterranean, the oligotrophic bay of Villefranche, no significant enrichment of trace elements in the SML was found, utilizing a hollow quartz tube for SML sampling [46]. In the coastal zone of Šibenik, middle Adriatic, Mediterranean, SML enrichment in metals was not significant, within time periods not considerably affecting trace elements’ bulk deposition fluxes [47]. The relatively low enrichment of the SML in dissolved trace metals seems to relate with limited aerosol inputs, the prevalence of mechanisms of removal instead of diffusion and/or the occurrence of metal sources in SSW [48]. Suspended particulate metals generally demonstrate higher EF values compared to those obtained for dissolved ones [30,46,49].

Comparing metal concentrations in SML samples collected with the two methods applied, significant differences were recorded in specific cases. Higher Cu levels were detected in glass plate samples compared to those of glass discs (176% in the second sampling) and Mn ones (228 and 156% in the second and third samplings) (Table 2). These considerable differences, are attributed to either intense spatial variation in these metal concentrations in the SML, due to sporadic high enrichments when a slick is present, or possible procedural contamination. An advantage of USVs in SML sampling is “automation superiority” in avoiding possible contamination deriving from the operator’s hands in the case of hand-held samplers. In the glass plate technique, a large number of immersions of the plate in seawater are require, to collect a sample volume adequate for chemical analyses. This results in a long contact time of the operator’s hands with the glass plate, introducing an increased contamination risk despite the precautions. Accordingly, in USVs, special attention is paid to the selection of materials to be used in SML and SSW samplers, with which the sample is in contact (e.g., glass discs wipers, peristaltic pump tubing and connectors).

An enrichment of the SML in dissolved ΣPAHs was calculated (glass discs: EF = 2.3 ± 0.5, glass plate: EF = 2.5 ± 0.4, mesh screen: EF = 2.6 ± 0.9), being statistically significant for all sampler types employed (difference from unity: p = 0.049, 0.028 and 0.043, respectively; one-way t-test) (Table S4). The lack of significant discrepancies of EFs demonstrates that the dissolved PAHs were vertically distributed over a relatively thick layer. The higher variation characterizing the mesh screen method suggests an inconsistent thickness of the collected SML samples. Dissolved PAHs fractions are generally more bioavailable to microbial degradation and volatile loss [10], pointing to more transient features of the dissolved phase. The SML of Antikyra bay was considerably enriched in ΣPAHs compared to that of the Saronicos gulf (mean EFs of ΣPAHs at the two sites within the Saronicos gulf 1.6 ± 0.4, 1.5 ± 0.4, respectively) and NW Mediterranean (mean EF = 1.5) [34,38]. Despite the continuous, moderate enrichment in surface seawater layers, the ultimate fate of PAHs in the environment is determined by a series of processes including deposition, volatilization, sinking, resuspension and degradation [50].

During the first sampling, phenanthrene was the most abundant PAH, while in the subsequent two samplings naphthalene was the most dominant. The prevalence of these 2–3-aromatic-ring low-molecular-weight (LMW) compounds is characteristic of the dissolved phase, as they are more soluble than their high-molecular-weight (HMW, 4–6 aromatic rings) counterparts, which tend to accumulate in the particulate phase [10]. This compositional profile often suggests a petrogenic influence on the SML [38].

The calculated EFs of n-alkanes showed similar degrees of SML enrichment among the sampling techniques applied, with glass discs yielding a mean EF of 1.2 ± 0.3, closely matching those of the glass plate (mean EF = 1.4 ± 0.1) and mesh screen (mean EF = 1.2 ± 0.3) (Table S4). EFs close to unity suggest that while concentrations are relatively high, the SML does not actively accumulate fresh inputs at a rate significantly higher than the SSW. This low enrichment is characteristic of periods with weak autochthonous biological production [50]. Higher EFs calculated in other study areas are attributed to the association of alkanes with refractory organic matter. It has been documented that substances such as fulvic acids fix and retain hydrocarbons within their molecular structures, effectively facilitating their presence in the microlayer, even under variable sea states [43].

The n-alkane distribution in the study area was characterized by the predominance of odd-numbered long-chain homologs (C25, C27, C29). This molecular profile indicates biogenic input, originating from higher terrestrial plants, rather than phytoplankton or algal sources [51].

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study presents the development of InterSeA USV, a compact platform for the autonomous collection of SML and SSW samples in marine coastal areas. Field validation was conducted during three sampling campaigns in Antikyra bay, Greece, comparing the USV automated glass disc method to hand-held sampling techniques (Harvey and Burzell glass plate and Garrett mesh screen) in terms of several biochemical parameters.

InterSeA is one of the smallest and lightest USVs using rotating glass discs for SML sampling, easily transported along the coastal zone even inside a small van. The integration of rotating glass discs for SML sampling, combined with a peristaltic pump for SSW collection, enables acquisition of paired datasets with minimal contamination due to the automation of the sampling procedure and reduced disturbance of the water surface. This design fills a critical niche in marine monitoring, enabling high-resolution spatial mapping in constrained, shallow or hard-to-access coastal environments, where larger research vessels or USVs cannot operate efficiently due to their size and draft limitations.

Comparative analysis revealed no systematic or statistically significant differences in the concentrations of SPM, DOC, Chl-α, dissolved trace metals (Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Mn, Ni, Pb, Zn), ΣPAHs (16 US EPA priority dissolved PAHs) or Σn-alkanes (C7–C40) between InterSeA and traditional sampling techniques (p > 0.05). The lack of significant discrepancies in DOC concentrations among the different sampling techniques suggests that the dilution effect, typically expected when thicker samples are collected by mesh screens, was negligible. DOC is vertically distributed along a relatively thick layer, rather than confined to a microlayer thinner than the minimum thickness sampled. While DOC enrichment remains relatively stable, regardless of the sampling technique, Chl-α shows high sensitivity. This discrepancy aligns with the observation that particulate materials are often confined to thinner layers, whereas DOC is distributed over relatively thicker ones.

The EFs calculated for dissolved trace metals in Antikyra bay, employing glass discs, were close or below unity, indicating an insignificant SML enrichment. The relatively low enrichment of SML in dissolved trace metals seems to relate with limited aerosol inputs, the prevalence of mechanisms of removal instead of diffusion and/or occurrence of metal sources in SSW. The alumina plant and the aquaculture activities operating along the coast of the study area impact the aquatic ecosystem metal balance, mainly regarding Cr, Mn, Ni and Zn.

The EFs of dissolved ΣPAHs (glass discs: 2.3 ± 0.5, glass plate: 2.5 ± 0.4, mesh screen: 2.6 ± 0.9) revealed a statistically significant SML enrichment, due to anthropogenic coastal activities such as ports, shipping and operation of local industries. The prevalence of naphthalene and phenanthrene (2–3-aromatic-ring LMW compounds), often suggest a petrogenic influence on the SML. The EFs of n-alkanes close to unity demonstrate that while concentrations are relatively high, the SML does not actively accumulate fresh inputs at a rate significantly higher than the SSW. This low enrichment is characteristic of periods with weak autochthonous biological production.

In addition to the detailed development design and operation verification of InterSeA, some limitations should be acknowledged. Three sampling campaigns were carried out, since weather conditions did not permit an extension of the time period or the number of samplings. Sampling data were collected under calm conditions (wind speed 1.4–2.1 m s−1, sea state 0–1 bf). The rather limited data collected lead to incomplete statistical analysis, restrained to basic tests. The employment of the system is feasible in ideal environments; however, information under “non-ideal” or “turbulent” conditions is lacking.

Future research should prioritize the integration of in situ sensors (e.g., fluorometer, CDOM) to thoroughly study the sources and fate of organic matter in the SML. The testing of USV with glass discs under higher sea states would demonstrate how it withstands more severe sea conditions. Finally, the application in long-term monitoring studies would contribute to our understanding of SML dynamics. These advances would enhance the quality and quantity of information received, the determination of sea state conditions permitting USV employment and the documentation of results in relation to the biochemical processes occurring in the SML.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jmse14020233/s1, Figure S1: Containers for SML (a) and SSW (b) samples; Figure S2: Rechargeable batteries of the USV system; Figure S3: Anemometer, irradiance detector and antenna for the remote navigation of the USV; Figure S4: Rotation mechanism of glass discs; Table S1: Limits of detection (LODs) of n-alkanes (C7-C40); Table S2: Limits of detection (LODs) of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs); Table S3: Levels of dissolved organic carbon (DOC), suspended particulate matter (SPM), Chlorophyll-α (Chl-α) and their enrichment factors (EFs) in SML; Table S4: Levels of total PAHs (ΣPAHs), alkanes (Σn-alkanes) and their enrichment factors (EFs) in SML.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.; methodology, S.K., N.K., A.S., N.M., T.X. and A.N.; validation, S.K., N.K., A.S., K.K. and N.M.; formal analysis, S.K., N.K. and A.S.; investigation, S.K., N.K., A.S. and K.K.; resources, S.K. and T.P.; data curation, S.K. and T.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K., N.K. and A.S.; writing—review and editing, S.K., N.K., A.S., G.K., K.K. and E.B.; visualization, S.K., N.K. and A.S.; supervision, S.K.; project administration, S.K., N.K., A.S. and T.P.; funding acquisition, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (HFRI), Basic research Financing (Horizontal support of all Sciences), under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan “Greece 2.0” funded by the European Union—Next Generation EU. H.F.R.I. Project Number: 15392, “INTERSEA—DEVELOPMENT OF AUTOMATED SAMPLING TOOLS TO MONITOR THE SEA—AIR INTERFACE IN COASTAL AREAS”.

Data Availability Statement

Data on the commercial USV platform used contain proprietary and confidential information related. Due to data confidentiality and restrictions imposed by the manufacturer, this information is not publicly available. Data supporting the findings of this study are included within the article. Further data is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their valuable comments, which significantly enhanced the manuscript. The authors also thank Hippokrates Pappas and Georgios Kontostavlos from METRICA S.A. (Athens, Greece), for their valuable contribution to the design and construction of the InterSeA USV. Special thanks are due to C. Zeri and E. Tzempelikou for their contribution to sample pretreatment for metal analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The author Georgios Katsouras was employed by the company Athens Water and Sewerage Company S.A.; the author Nikolaos Mavromatis was employed by the company Intelligence Machines; the author Theodoros Xenakis was employed by the company METRICA S.A.; the author Angeliki Ntourntoureka was employed by the company METRICA S.A. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADCP | Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler |

| Chl-α | Chlorophyll-α |

| CTD | Conductivity Temperature Depth |

| DOC | Dissolved Organic Carbon |

| EF | Enrichment Factor |

| EI | Electron Ionization |

| FEP | Fluorinated Ethylene Propylene |

| GF/F | Glass Fiber Filter |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| HMW | High Molecular Weight |

| HTCO | High-Temperature Catalytic Oxidation |

| KED | Kinetic Energy Discrimination |

| LMW | Low Molecular Weight |

| LOD | Limit Of Detection |

| NKUA | National and Kapodistrian University of Athens |

| OC | Organic Carbon |

| PAH | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon |

| RPM | Rotations Per Minute |

| Σn-alkanes | Sum of n-alkanes |

| SAS | Surface Active Substances |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SML | Surface Microlayer |

| ΣPAHs | Sum of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons |

| SPM | Suspended Particulate Matter |

| SSW | Subsurface Water |

| US EPA | United States Environmental Protection Agency |

| USV | Unmanned Surface Vehicle |

References

- Yang, L.; Zhang, J.; Engel, A.; Yang, G.-P. Spatio-Temporal Distribution, Photoreactivity and Environmental Control of Dissolved Organic Matter in the Sea-Surface Microlayer of the Eastern Marginal Seas of China. Biogeosciences 2022, 19, 5251–5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurl, O.; Obbard, J.P. A Review of Pollutants in the Sea-Surface Microlayer (SML): A Unique Habitat for Marine Organisms. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2004, 48, 1016–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurl, O.; Ekau, W.; Landing, W.M.; Zappa, C.J. Sea Surface Microlayer in a Changing Ocean—A Perspective. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2017, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.T. The Sea Surface Microlayer: Biology, Chemistry and Anthropogenic Enrichment. Prog. Oceanogr. 1982, 11, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhengbin, Z.; Liansheng, L.; Zhijian, W.; Jun, L.; Haibing, D. Physicochemical Studies of the Sea Surface Microlayer: I. Thickness of the Sea Surface Microlayer and Its Experimental Determination. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1998, 204, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, M.; Murrell, J.C. The Sea-Surface Microlayer Is a Gelatinous Biofilm. ISME J. 2009, 3, 1001–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, P.S.; Duce, R.A. The Sea Surface and Global Change; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 339–370. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, L.; Liu, C.; Cai, W. Studies on the Sea Surface Microlayer: II. The Layer of Sudden Change of Physical and Chemical Properties. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003, 264, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurl, O.; Wurl, E.; Miller, L.; Johnson, K.; Vagle, S. Formation and Global Distribution of Sea-Surface Microlayers. Biogeosciences 2011, 8, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-J.; Lin, B.-S.; Lee, C.-L.; Brimblecombe, P. Enrichment Behavior of Contemporary PAHs and Legacy PCBs at the Sea-Surface Microlayer in Harbor Water. Chemosphere 2020, 245, 125647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, G.; Martínez-Varela, A.; Roscales, J.L.; Vila-Costa, M.; Dachs, J.; Jiménez, B. Enrichment of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in the Sea-Surface Microlayer and Sea-Spray Aerosols in the Southern Ocean. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 267, 115512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Polo, K.; Tobón-Monsalve, D.; Florez-Leiva, L.; Lehners, C.; Wurl, O.; Pacheco, W.; Ribas-Ribas, M. Distribution of Surfactants in the Sea Surface Microlayer across a Tropical Estuarine System in Caribbean Colombia. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2025, 320, 109291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gligorovski, S. Atmospheric Implications of Ocean–Atmosphere Physicochemical Interactions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2025, 25, 11757–11787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, W.D. Collection of Slick-Forming Materials from the Sea Surface. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1965, 10, 602–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, G.W.; Burzell, L.A. A Simple Microlayer Method for Small Samples. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1972, 17, 156–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, G.W. Microlayer Collection from the Sea Surface: A New Method and Initial Results. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1966, 11, 608–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreshchinskii, A.; Engel, A. Seasonal Variations of the Sea Surface Microlayer at the Boknis Eck Times Series Station (Baltic Sea). J. Plankton Res. 2017, 39, 943–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, M.; Wurl, O. Guide to Best Practices to Study the Ocean’s Surface; Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom for SCOR: Plymouth, UK, 2014; 118p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stortini, A.M.; Cincinelli, A.; Degli Innocenti, N.; Tovar-Sánchez, A.; Knulst, J. Surface microlayer. In Comprehensive Sampling and Sample Preparation; Pawliszyn, J., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinki, M.; Wendeberg, M.; Vagle, S.; Cullen, J.T.; Hore, D.K. Characterization of Adsorbed Microlayer Thickness on an Oceanic Glass Plate Sampler. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2012, 10, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsouras, G.; Dimitriou, E.; Karavoltsos, S.; Samios, S.; Sakellari, A.; Mentzafou, A.; Tsalas, N.; Scoullos, M. Use of Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USVs) in Water Chemistry Studies. Sensors 2024, 24, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Cabecinhas, D.; Pascoal, A.M.; Zhang, W. Prescribed Performance Path Following Control of USVs via an Output-Based Threshold Rule. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 6171–6182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.-L.; Guo, G. Prescribed Performance Fault-Tolerant Control of Nonlinear Systems via Actuator Switching. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2024, 32, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas-Ribas, M.; Mustaffa, N.I.H.; Rahlff, J.; Stolle, C.; Wurl, O. Sea Surface Scanner (S3): A Catamaran for High-Resolution Measurements of Biogeochemical Properties of the Sea Surface Microlayer. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2017, 34, 1433–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurl, O.; Gassen, L.; Badewien, T.H.; Braun, A.; Emig, S.; Holthusen, L.A.; Lehners, C.; Meyerjürgens, J.; Ribas, M.R. HALOBATES: An Autonomous Surface Vehicle for High-Resolution Mapping of the Sea Surface Microlayer and Near-Surface Layer on Essential Climate Variables. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2024, 41, 1197–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, M.; Engel, A.; Frka, S.; Gašparović, B.; Guitart, C.; Murrell, J.C.; Salter, M.; Stolle, C.; Upstill-Goddard, R.; Wurl, O. Sea Surface Microlayers: A Unified Physicochemical and Biological Perspective of the Air–Ocean Interface. Prog. Oceanogr. 2013, 109, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuraru, R.; Fine, L.; van Pinxteren, M.; D’Anna, B.; Herrmann, H.; George, C. Photosensitized Production of Functionalized and Unsaturated Organic Compounds at the Air-Sea Interface. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimura, Y.; Suzuki, Y. A High-Temperature Catalytic Oxidation Method for the Determination of Non-Volatile Dissolved Organic Carbon in Seawater by Direct Injection of a Liquid Sample. Mar. Chem. 1988, 24, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, J.D.H.; Parsons, T.R. A Practical Handbook of Seawater Analysis, 2nd ed.; Bulletin 167; Fisheries Research Board of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1972; 310p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavoltsos, S.; Sakellari, A.; Dassenakis, M.; Bakeas, E.; Scoullos, M. Trace Metals in the Marine Surface Microlayer of Coastal Areas in the Aegean Sea, Eastern Mediterranean. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2021, 259, 107462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavoltsos, S.; Sakellari, A.; Plavšić, M.; Bekiaris, G.; Tagkouli, D.; Triantafyllidis, A.; Giannakourou, A.; Zervoudaki, S.; Gkikopoulos, I.; Kalogeropoulos, N. Metal Complexation, FT-IR Characterization, and Plankton Abundance in the Marine Surface Microlayer of Coastal Areas in the Eastern Mediterranean. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 932446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzempelikou, E.; Zeri, C.; Iliakis, S.; Paraskevopoulou, V. Cd, Co, Cu, Ni, Pb, Zn in Coastal and Transitional Waters of Greece and Assessment of Background Concentrations: Results from 6 Years Implementation of the Water Framework Directive. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 145177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavoltsos, S.; Sakellari, A.; Makarona, A.; Plavšić, M.; Ampatzoglou, D.; Bakeas, E.; Dassenakis, M.; Scoullos, M. Copper Complexation in Wet Precipitation: Impact of Different Ligand Sources. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 80, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellari, A.; Karavoltsos, S.; Moutafis, I.; Koukoulakis, K.; Dassenakis, M.; Bakeas, E. Occurrence and Distribution of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Marine Surface Microlayer of an Industrialized Coastal Area in the Eastern Mediterranean. Water 2021, 13, 3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahlff, J.; Stolle, C.; Giebel, H.-A.; Brinkhoff, T.; Ribas-Ribas, M.; Hodapp, D.; Wurl, O. High Wind Speeds Prevent Formation of a Distinct Bacterioneuston Community in the Sea-Surface Microlayer. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017, 93, fix041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.-C.; Sperling, M.; Engel, A. Effect of Wind Speed on the Size Distribution of Gel Particles in the Sea Surface Microlayer: Insights from a Wind–Wave Channel Experiment. Biogeosciences 2018, 15, 3577–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavoltsos, S.; Kalambokis, E.; Sakellari, A.; Plavšić, M.; Dotsika, E.; Karalis, P.; Leondiadis, L.; Dassenakis, M.; Scoullos, M. Organic Matter Characterization and Copper Complexing Capacity in the Sea Surface Microlayer of Coastal Areas of the Eastern Mediterranean. Mar. Chem. 2015, 173, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitart, C.; García-Flor, N.; Bayona, J.M.; Albaigés, J. Occurrence and Fate of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Coastal Surface Microlayer. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2007, 54, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.J. A Field Evaluation of Plate and Screen Microlayer Sampling Techniques. Mar. Chem. 1982, 11, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Chen, J.; Tian, K.; Peng, D.; Liao, X.; Wu, X. Geochemical Characteristics and Toxic Elements in Alumina Refining Wastes and Leachates from Management Facilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Xu, Q.; Lyu, H.; Kong, J.; Wang, X.; Shen, B.; Bi, Y. Sediment and Residual Feed from Aquaculture Water Bodies Threaten Aquatic Environmental Ecosystem: Interactions among Algae, Heavy Metals, and Nutrients. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 326, 116735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitart, C.; García-Flor, N.; Dachs, J.; Bayona, J.M.; Albaigés, J. Evaluation of Sampling Devices for the Determination of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Surface Microlayer Coastal Waters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2004, 48, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stortini, A.M.; Martellini, T.; Del Bubba, M.; Lepri, L.; Capodaglio, G.; Cincinelli, A. n-Alkanes, PAHs and Surfactants in the Sea Surface Microlayer and Sea Water Samples of the Gerlache Inlet Sea (Antarctica). Microchem. J. 2009, 92, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemirovskaya, I.A.; Khramtsova, A.V. Hydrocarbons and suspended matter in the atmosphere-water boundary layer in the Barents and Kara Seas. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 191, 114892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.J. Dissolved Organic Materials in Surface Microlayers: Temporal and Spatial Variability and Relation to Sea State. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1983, 28, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebling, A.M.; Landing, W.M. Sampling and Analysis of the Sea Surface Microlayer for Dissolved and Particulate Trace Elements. Mar. Chem. 2015, 177, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penezić, A.; Milinković, A.; Alempijević, S.B.; Žužul, S.; Frka, S. Atmospheric Deposition of Biologically Relevant Trace Metals in the Eastern Adriatic Coastal Area. Chemosphere 2021, 283, 131178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebling, A.M.; Landing, W.M. Trace Elements in the Sea Surface Microlayer: Rapid Responses to Changes in Aerosol Deposition. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2017, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuong, D.T.; Karuppiah, S.; Obbard, J.P. Distribution of Heavy Metals in the Dissolved and Suspended Phase of the Sea-Surface Microlayer, Seawater Column and in Sediments of Singapore’s Coastal Environment. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2008, 138, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitart, C.; García-Flor, N.; Miquel, J.C.; Fowler, S.W.; Albaigés, J. Effect of the Accumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Sea Surface Microlayer on Their Coastal Air-Sea Exchanges. J. Mar. Syst. 2010, 79, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, W.A. Assessment of Aliphatic Hydrocarbons in Sediments of Shatt Al-Arab River, Southern Iraq, North East Arabian Gulf. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 13, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.