1. Introduction

With the deepening of marine informatization strategies [

1], the construction of an integrated undersea-air-space information network [

2] has resulted in urgent demands for across seawater–air communication [

3] technologies. Thus, it is imperative to establish an efficient and reliable information transmission system to underpin the comprehensive advancement of smart ocean development. Traditional underwater acoustic communication relying on multi-hop transmission via surface buoys as relay nodes reveals inherent deficiencies in complex marine environments, including insufficient security, poor environmental adaptability, and weak anti-jamming capabilities. For example, in underwater acoustic sensor networks, AUV-aided localization and asynchronous localization schemes have been proposed to address positioning challenges under time-varying channels and node mobility [

4,

5,

6], yet they also highlight underlying reliability and real-time performance issues caused by channel fluctuations and environmental changes. Compared with acoustic waves, EM (electromagnetic) waves have emerged as an ideal technical pathway to break through sea-air communication barriers [

7], owing to their characteristics of direct transmission across seawater–air and remarkable advantages in underwater high speed [

8]. As early as 2010, European researchers successively evaluated the feasibility of constructing marine wireless sensor networks using electromagnetic waves as the information carrier in the ASTEC and UnderWorld projects [

9,

10]. In 2017, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) launched “A Mechanically Based Antenna (AMEBA)” project, aiming to explore miniaturized and high-efficiency electromagnetic wave transmitting antennas and communication systems suitable for extremely low frequency (ELF) and very low frequency (VLF) underwater communications [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. In 2020, the Russian Navy, in collaboration with the IVA Corporation, conducted tests on the underwater electromagnetic wave communication system developed by the latter in the Barents Sea, achieving favorable results [

16]. In 2025, CSignum Company of the United Kingdom secured 3.9 million British pounds in funding support, which is intended to promote the application of electromagnetic wave cross-interface communication technology in the construction of underwater Internet of Things (IoT). All of the above information indicates that underwater electromagnetic wave cross-interface communication technology is accelerating the extension from basic theoretical research to practical applications, and its strategic value and engineering potential are becoming increasingly prominent. However, the abrupt refractive index changes at the seawater–air interface [

17,

18] and across media transmission properties cause signals to undergo severe attenuation and complex multipath effects [

19]. When electromagnetic waves propagate between transceiving nodes near the sea surface, they traverse a propagation path across the water–air–water interface. The coupled interference from time-varying channels and background noise severely restricts communication reliability and leads to a significant decline in energy efficiency. Therefore, there is an urgent need to achieve breakthroughs in efficient seawater–air cross-medium transmission mechanisms and low-complexity channel estimation techniques.

EM wave transmission across seawater–air is affected by the multipath effect [

19], where multipath signals superimpose at the receiver [

20,

21], leading to constructive or destructive interference that causes fluctuations in the received signal strength. This phenomenon not only induces dynamic changes in the SNR but also potentially causes signal distortion, further exacerbating the instability of communication across seawater–air. The Recursive Least Squares (RLS) algorithm has attracted widespread attention due to its fast convergence rate, and norms have also been introduced into the RLS algorithm to further improve the algorithm accuracy in sparse environments [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Inspired by the Proportionate Normalized Least Mean Square (PNLMS) algorithm, in 2020, Qin Zhen et al. from Southeast University [

26,

27] proposed the Proportional Recursive Least Squares (PRLS) algorithm and its l

1-norm version. In 2022, Paleologu [

28] proposed a data-reuse-based RLS algorithm, which makes full use of prior information by reusing the input signal of the filter at the same moment. However, all the above RLS algorithms are affected by the matrix inversion of the autocorrelation coefficient matrix, resulting in a computational complexity of

, where

denotes the channel length. The high computational complexity limits the practical application of the RLS algorithm; thus, low-complexity variants of the RLS algorithm have also been extensively studied. In 2023, Huang proposed an FBMC channel estimation technology based on pilot design, which has advantages in spectral efficiency and power efficiency. However, for complex air-sea cross-medium transmission channels, it is difficult to adapt to the complex changes in time-varying scenarios [

29]. Therefore, designing a reliable EM wave across seawater–air channel estimation algorithm can effectively separate and identify the characteristics of each path (amplitude, delay, and phase variation) in multipath propagation, preparing for subsequent signal gain compensation and distortion elimination.

Although adaptive filtering algorithms [

30,

31,

32] have been widely applied in various fields [

33,

34], their exploration in EM wave transmission across seawater–air channel estimation remains relatively limited. Efficient channel estimation can accurately characterize across seawater–air channel characteristics, track channel dynamics in real time, and support subsequent equalization and decoding, thereby significantly enhancing the reliability of communication systems and providing a solid theoretical basis and technical support for optimizing communication performance in complex environments. However, research on channel estimation for electromagnetic wave cross-medium communication is currently almost non-existent. To this end, this paper proposes a Fast Recursive Least Squares (FRLS) algorithm. By optimizing the input data structure of the filter, this algorithm achieves a favorable balance between computational efficiency and channel estimation accuracy [

35], demonstrating its unique advantages and broad prospects in complex application scenarios.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the background and derives the FRLS algorithm.

Section 3 details the simulation setup and results.

Section 4 describes the marine experiments and discusses the findings.

Section 5 concludes and outlines the future work.

2. Theoretical Analysis

In this section, we provide a brief introduction to the underwater electromagnetic cross-interface communication channel model. Subsequently, through the derivation of the complex Recursive Least-Squares (RLS) algorithm, the foundation is established for developing the complex Fast Recursive Least-Squares (FRLS) algorithm. The formulation of the FRLS algorithm, along with its forward prediction, backward prediction, and joint estimation, is then derived and analyzed.

2.1. EM Wave Transmission Channel Across Seawater–Air Interface

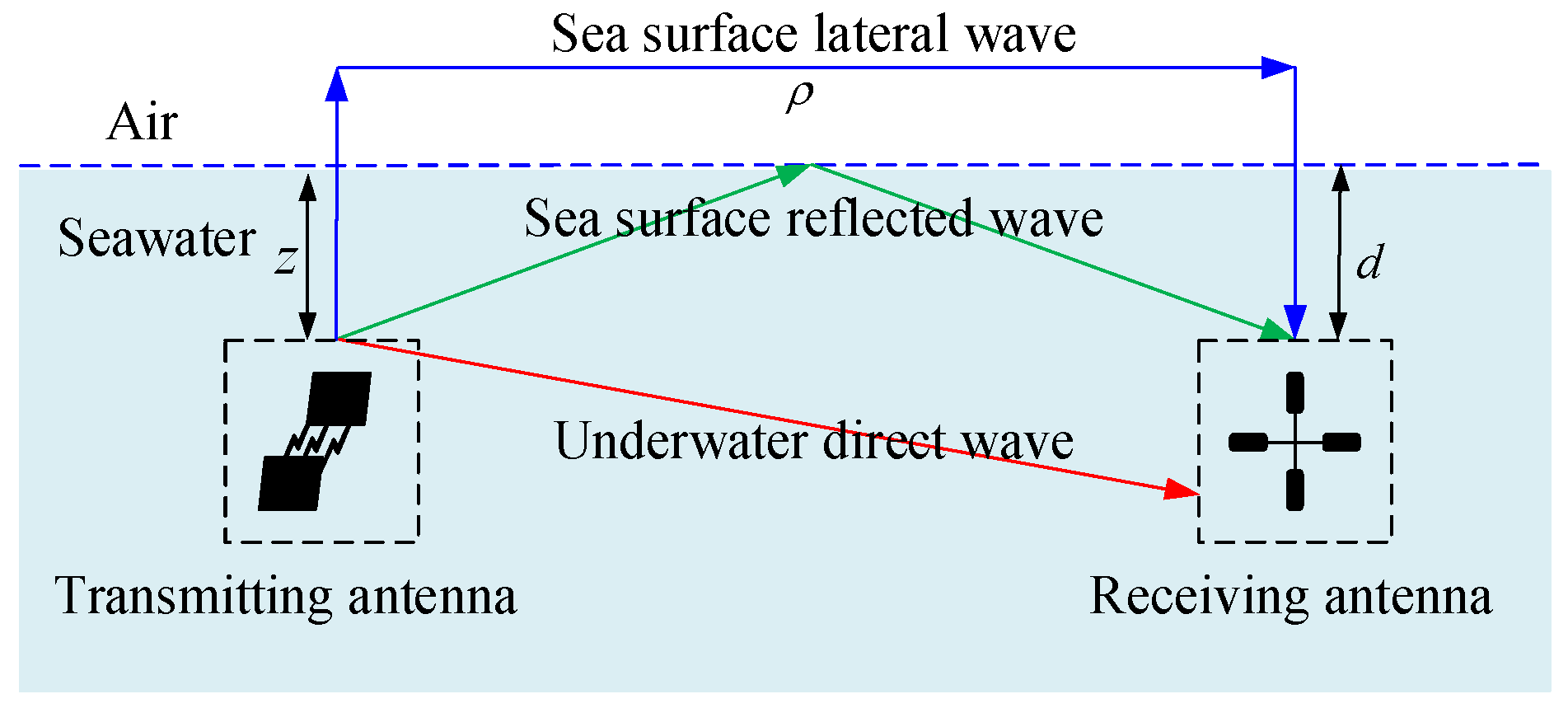

EM waves propagation across the seawater–air interface has been demonstrated to comprise a collection of multiple propagation paths.

Figure 1 illustrates these distinct propagation paths, which include three primary components: the underwater direct wave, the sea surface lateral wave, and the sea surface reflected wave. The calculation of the EM field intensity and phase for each propagation path has been studied [

35]. Under the influence of two conductive media with distinct properties (i.e., air and seawater), the wavefronts from different paths exhibit varying propagation delays upon reaching the receiver. This disparity leads to constructive superposition of in-phase signal components and destructive interference (or cancellation) of out-of-phase components, thereby giving rise to the multipath effect in across seawater–air interface communication.

On the left side of

Figure 1 is the transmitting antenna, with its distance to the sea surface denoted as

; on the right side is the receiving antenna, with its distance to the sea surface denoted as

. The parameter

represents the horizontal propagation distance between the transmitter and receiver, and

,

, and

are all measured in meters.

By modeling the across seawater–air interface multipath channel as a linear Finite Impulse Response (FIR) filter, the impulse response of the multipath channel can be expressed as below:

where

is the amplitude of the multipath channel. This can be obtained as follows:

where

is the coordinate of the receiver with the transmission point as the origin,

f is the center frequency of communication signal,

is the field strength of the receiving EM wave from the

l-th path,

is the transmitted EM field strength. These field strengths are derived from propagation model [

36].

is the Dirac delta function and

represents the total number of propagation paths. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the model primarily considers three paths: the direct wave path, the sea surface reflected wave path, and the sea surface lateral wave path.

is the time delay of the

l-th path. Specifically, the delay for the direct wave path is as follows:

The sea surface reflected wave path is the following:

The sea surface lateral wave path is as follows:

where

c is the speed of the EM wave in air, and

denotes the group velocity of the underwater EM waves, which is as below:

where

,

and

are conductivity, permeability and dielectric permittivity of seawater, respectively.

The accuracy and stability of channel estimation will provide important support for subsequent signal reconstruction, thereby improving the overall performance of across seawater–air interface communication methods.

2.2. Derivation of the Complex RLS Algorithm

For the sake of brevity, this paper defines a unified set of notations for subsequent algorithm derivations, where denotes the filter order and also represents the channel length in cross-medium channel estimation; is the time index with , where stands for the signal length; is the filter input vector with a dimension of ; is the filter output with a dimension of , which denotes both the filter weight coefficient vector and the estimated channel impulse response coefficient vector; is the reference signal and is scalar; the autocorrelation coefficient prediction matrix and cross-correlation coefficient prediction vector have dimensions of and , respectively; denotes the Hermitian transpose of a vector or matrix; and denotes the conjugate. Usually, is taken as .

Transmitted signals will experience amplitude and phase changes during propagation across seawater–air channels. Complex channel estimation algorithms can simultaneously handle amplitude attenuation and phase shift, accurately estimate channel characteristics, thereby improving the accuracy of channel estimation and the performance of communication systems. Therefore, in this subsection, the complex RLS (hereinafter directly referred to as RLS) algorithm will be derived, which is the basis for generating the FRLS algorithm. The RLS algorithm aims to minimize the sum of squares of the difference between the desired signal and the output of the model filter. When a new sample of the input signal is received in each iteration, the solution to the least squares problem can be calculated in a recursive form, thus generating the RLS algorithm. The minimum weighted least squares error at a given time

is the following:

where

is the forgetting factor, and its value range is

.

ε(

n) is the a posteriori error, and the a priori error

can be written as follows:

From Equation (8), it can be noticed that each error consists of the difference between the desired signal and the filter output. By taking the partial derivative of

with respect to

and setting the result of the differentiation to zero, we obtain the optimal solution for the weight vector

of the complex RLS algorithm, which is the following:

where the autocorrelation coefficient matrix

is defined as

and the cross-correlation coefficient vector

is defined as

The direct computation of

results in a computational complexity of

. By introducing the matrix inversion lemma, the computational complexity can be reduced to

. The inverse computation of

with reduced complexity can be expressed as follows:

where

is used to represent

. Clearly,

is a diagonal matrix. Although (12) has reduced the computational complexity via the matrix inversion lemma,

still requires a complexity of

, which limits the practical application of the RLS algorithm in across seawater–air channel estimation, especially under limited computational resources.

is called the gain vector of the RLS algorithm, expressed as below:

According to (9), we know

. Substituting this relationship into (11), we obtain another representation of

, which facilitates deriving the updated equation for

. The new expression for

is the following:

Substituting

from the above into the definition of

in (9) relates the weight vector at time

to that at time

. The specific derivation process is as follows:

Further, by analyzing the relationship among

,

, and

,

can be expressed as the following:

Using (16), the updated equation for

in (15) can be simplified as follows:

The second-order complexity of the classical RLS algorithm restricts its practical use. In reality, by modifying the recursive approach of the complex RLS algorithm, higher computational efficiency can be attained, thus conserving computational resources for EM wave communication across the seawater–air interface.

2.3. FRLS Algorithm for Across Seawater–Air Channel Estimation

In this subsection, a complex version of the FRLS algorithm with improved computational efficiency is developed. The core idea of the FRLS algorithm involves solving forward and backward prediction problems by adjusting the structure of the input data vector. It derives the relationship between a priori and a posteriori errors and obtains the optimal solution for the weighted least squares error in both directions. By linking forward and backward prediction weight vectors via an auxiliary filter and applying them to the joint estimation process, the prediction of the current-time weight vector is ultimately output. Importantly, in the derivation of FRLS, we establish its connection with the complex RLS algorithm and explain why FRLS has low complexity.

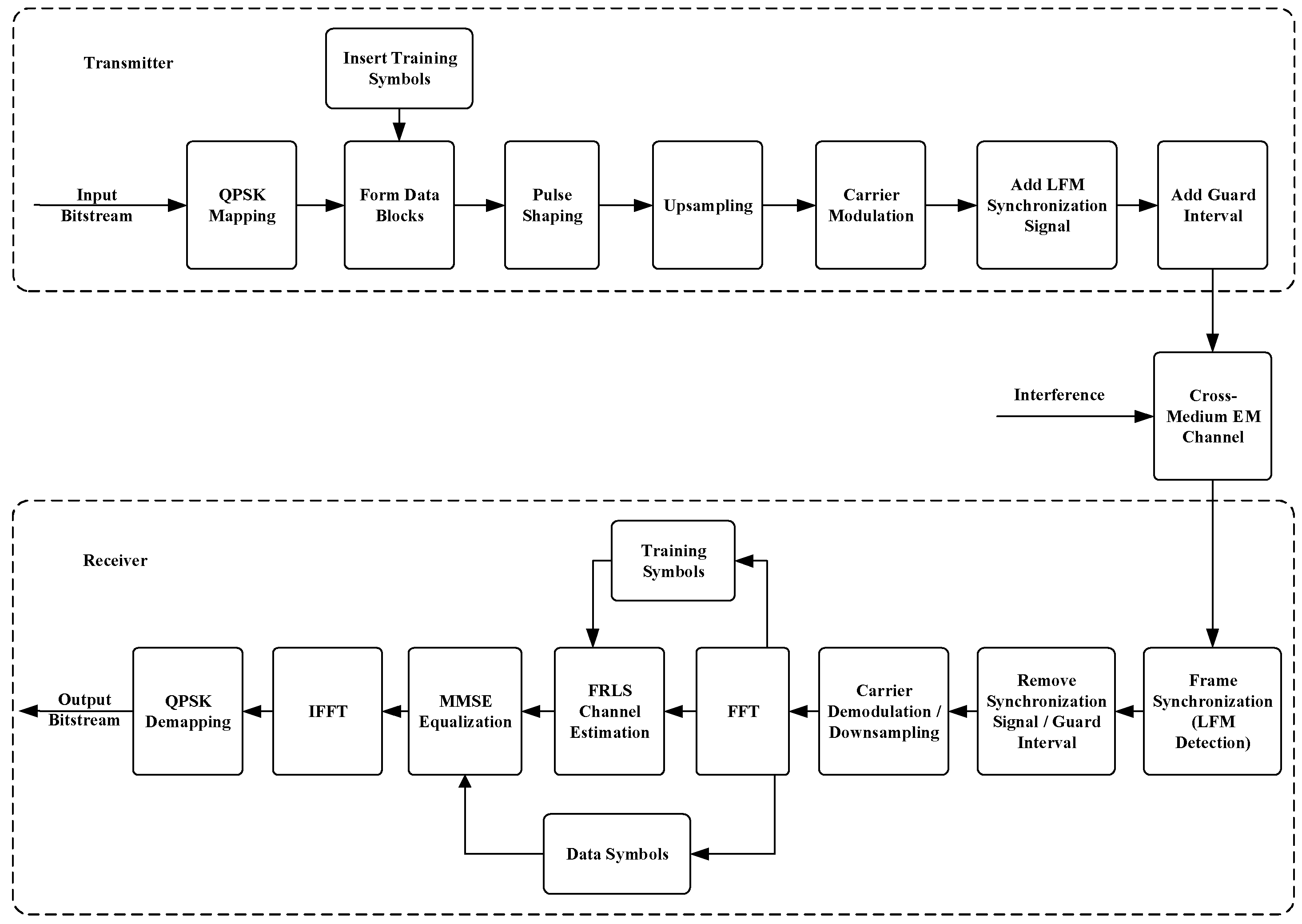

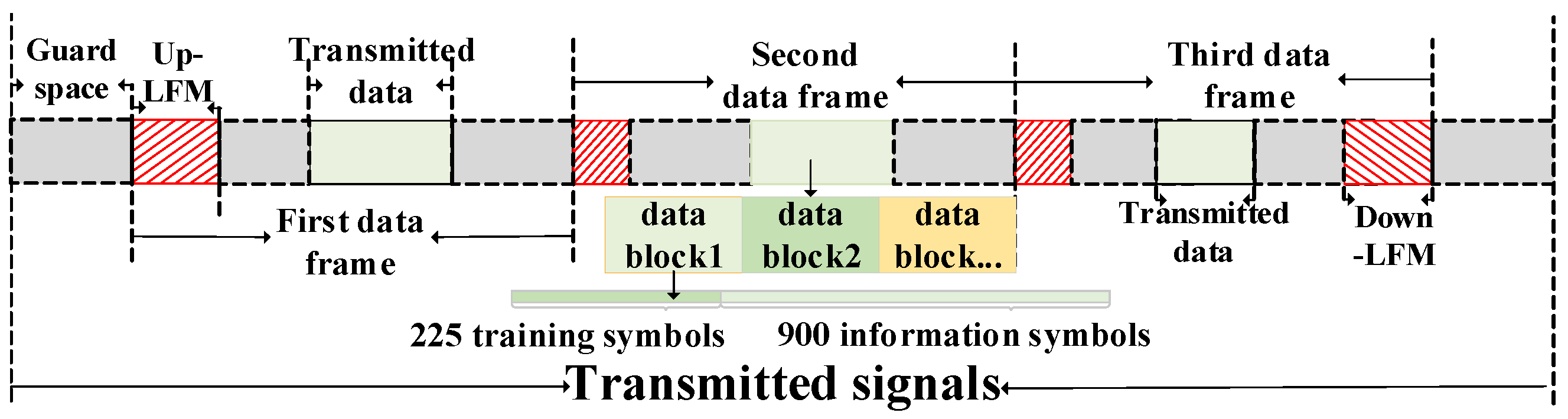

To provide a system-level view and clarify where synchronization, channel estimation, and equalization are performed,

Figure 2 summarizes the end-to-end transmitter–receiver processing chain used throughout this work. An LFM segment is appended as a synchronization preamble for robust frame detection and segmentation, while training symbols are inserted for channel estimation. FRLS operates on the training portion, and the resulting channel estimate is used to construct an MMSE equalizer for QPSK data recovery and performance evaluation.

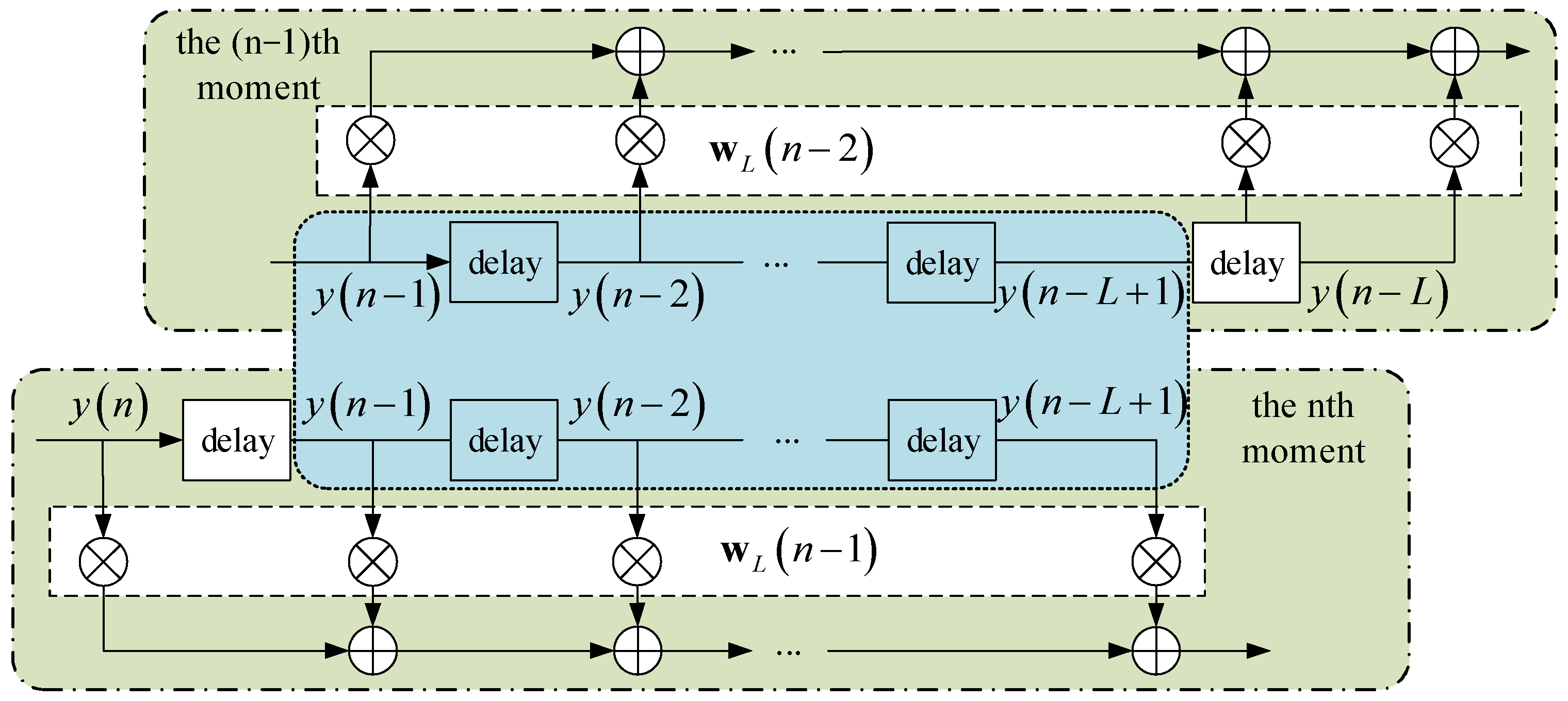

The main difference in solving forward and backward prediction problems lies in the usage of filter input data. For subsequent derivations, denote the input vector as and the weight vector as , where the subscript represents the vector order (for across seawater–air channels, . In scalars, denotes the order. Superscripts and in and denote forward and backward prediction, respectively.

The input vector at time

,

, gives the input vector at time

as follows:

Clearly,

and

share a common data structure of length

:

In the upper half of

Figure 3, the green box represents the filter structure at time

, while the lower green box represents that at time

. The blue box corresponds to the data structure in (19).

Further, using, (18) and (19), an

-order data relationship is formed:

Subsequent derivations utilize (20). The goal of solving forward and backward prediction is to avoid direct updates of

in (13), as

is essentially the inverse of

, with a computational complexity of

. The core of the FRLS algorithm is to maintain a computational complexity of

for the weight vector update process:

2.4. Solving the Forward Prediction Problem

The forward prediction error is expressed as below:

The forward prediction cost function is the following:

where

is the forgetting factor. Differentiating

with respect to

and setting it to zero:

The optimal weight vector is as follows:

where

and

are the autocorrelation matrix and cross-correlation vector for forward prediction. The minimum cost function is the following:

Similar to (12), denoting

, the forward prediction weight vector at time

is recursively updated as below:

In the equation, the second step utilizes (12) and (14), and

is an introduced auxiliary vector, expressed as

And

is written as

Using the same calculation method as in (16), we obtain

For

and

, their conversion relationship can be derived using (27), specifically:

where

is called the conversion factor, and its update formula is

The time update of

can be expressed as

Summarizing (27)–(29), it is found that the update of

still requires the inversion of

, i.e., calculating

. To achieve the low-complexity computation of

, partial expressions of

need to be employed, which are derived from the partial expressions of

. According to (25), the definition of

, and the definition of

, we derive

Using

(identity matrix), the partial expression of

is derived as the following:

By premultiplying

with (20) and leveraging the relationship in (30), the update equation for

is obtained:

In (36), the update of

relies on (at time

for the

-th order). Compared to (29), the update of

avoids using

; instead, it involves

,

, and

, whose computational complexity is no longer quadratic. To simplify subsequent operations, we introduce a new auxiliary variable

and substitute it into the above equation:

Finally, using

to update the forward prediction weight vector, we derive the following:

2.5. Solving the Backward Prediction Problem

The core of solving the backward prediction problem lies in using current information to predict previous information, i.e., estimating

using the information sequence defined in (19). The solution process for the backward prediction problem is analogous to the forward case. First, using the method in (31), the relationship between the a priori error

and the a posteriori error

for the backward prediction problem is derived as

The objective function for backward prediction, which is minimized in the least squares sense, is the following:

Similar to (24), we take the partial derivative of

with respect to

and set the result to zero, yielding the optimal solution for the backward prediction problem:

In the equations,

and

denote the autocorrelation matrix and cross-correlation vector for backward prediction, respectively. Substituting (41) into (40) and using the definitions of

and

in (41), the minimum value of the objective function for the backward prediction problem is derived as follows:

where

The relationship between

(applicable to backward prediction) and

is given by

Using the definitions of

and

from (12) and (14) to expand (41) the time update of

is derived as follows:

Rewriting the definition of

as (48), the partial expression of

is obtained:

Using the same relationship as in (35), i.e.,

, we derive the

-th order

at time

n and the

-th order

at the same time for the backward prediction problem:

Postmultiplying the above equation by

, we obtain the update formula for

:

The last element of

is expressed as

Substituting (39), (44), and (51) into (46), we derive the following:

Substituting (39) into the above equation again, the update equation for the conversion factor is obtained:

2.6. Joint Estimation

By solving the forward and backward prediction problems, we can, respectively, derive the update equations for the corresponding weight coefficient vectors and other parameters. To address the general across seawater–air channel estimation problem, further derivation from these forward and backward prediction problems is required, leading to the estimation of a related process represented by the true desired signal ; this process is referred to as joint process estimation.

The a priori error of the joint process estimation can be expressed as

Referring to (39), the a posteriori error of the joint process estimation is expressed as

Given the a priori and a posteriori errors of the joint process estimation, the time update of the output weight coefficient vector can first be related to

and

, as follows:

The detailed steps of the complex-valued FRLS algorithm are presented in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1. Complex-Valued FRLS Algorithm |

Input input vector , desired signal , channel length , forgetting factor ,

conversion factor , initial error value

Output predicted coefficient vector

Initialize predicted coefficient vector , ,

For n = 1: N do

Calculate the forward prior error using Equation (22):

Calculate the forward-backward posterior error using Equation (31):

Calculate the minimum value of the forward objective function min using Equation (33):

Update the weight coefficient vector of the forward prediction using Equation (27):

Update using Equation (37):

Calculate the conversion factor using Equation (32):

Calculate the backward prior error using Equation (51):

Calculate the -th order using Equation (53):

Calculate the posterior error using Equation (39):

Use Equation (45) to calculate the minimum value of the backward prediction objective function:

Calculate the -th order using Equation (50):

Use Equation (56) to calculate the weight coefficient vector of backward prediction:

Joint estimation:

Calculate the prior error and posterior error using Equations (54) and (55):

The update of the weight coefficient vector is obtained using Equation (56):

End |

2.7. Parameter Sensitivity and Practical Guidelines

Before presenting the numerical results, we briefly discuss the sensitivity of the key FRLS parameters and provide practical guidelines for implementation. The forgetting factor controls the tracking–misadjustment trade-off. Values closer to one provide a longer effective memory and typically yield lower steady-state error under slowly varying channels, whereas a smaller improves responsiveness to abrupt channel variations at the cost of higher noise sensitivity and possible steady-state fluctuation. In practice, one may start with and decrease it only when faster tracking is required; the final choice can be refined using a short validation window by minimizing the measured MSD/BER under the target operating conditions.

The conversion factor

in FRLS is not a user-tuned constant; it is recursively updated from the forward/backward error relations (see (31)–(33) and (53)). Therefore, practical sensitivity mainly stems from initialization and finite-precision safeguards associated with the conversion update. A robust implementation can initialize

and

with a small positive constant and apply a small regularization or magnitude clipping to prevent rare numerical instabilities. Representative parameter settings used in our simulations are provided in

Section 3.

3. Numerical Simulations

In this section, two simulation experiments were conducted to evaluate the computational efficiency and noise robustness of the FRLS algorithm for EM wave transmission across seawater–air channels. First, the computational complexity of the FRLS algorithm is analyzed in detail, and subsequent discussions are integrated with the simulation results. Second, under diverse EM wave transmission across seawater–air channel conditions, the noise robustness of the algorithm is emphatically analyzed to verify its adaptability and robustness. The compared algorithms include the Least Mean Squares (LMS), Improved Proportionate Normalized LMS (IPNLMS), Recursive Least Squares (RLS), and Proportionate RLS (PRLS), all implemented in their complex-valued versions. According to the characteristics of EM wave transmission across seawater–air channels, the channel impulse response coefficients change in real time as the propagation distance increases. In such a dynamic environment, the IPNLMS and PRLS algorithms can assign adaptive weights to different active taps; thus, these two algorithms are considered for comparison.

3.1. Computational Complexity Analysis of Estimation Algorithms for EM Wave Transmission Across Seawater–Air Channels

The computational complexity of the Traditional Recursive Least Squares (TRLS) algorithm mainly originates from the matrix inversion process of the coefficient matrix. The proposed FRLS algorithm avoids this operation by implementing forward–backward joint estimation, effectively reducing the computational complexity to a linear relationship with

.

Table 1 presents a detailed analysis of the computational complexity of the FRLS algorithm, where the time complexities required for the “+”, “×”, and “÷” operations are calculated separately, and the “−” operation is regarded as a type of the “+” operation.

Note that the operation counts in

Table 1 are reported in complex arithmetic. For transparency, we adopt the standard real-operation cost model: one complex multiplication requires four real multiplications and two real additions; one complex addition requires two real additions; and a complex division can be implemented via multiplication by the complex conjugate plus one real division. Under this model, the FRLS per-iteration cost remains linear in L, while classical RLS/PRLS exhibit quadratic scaling due to matrix updates.

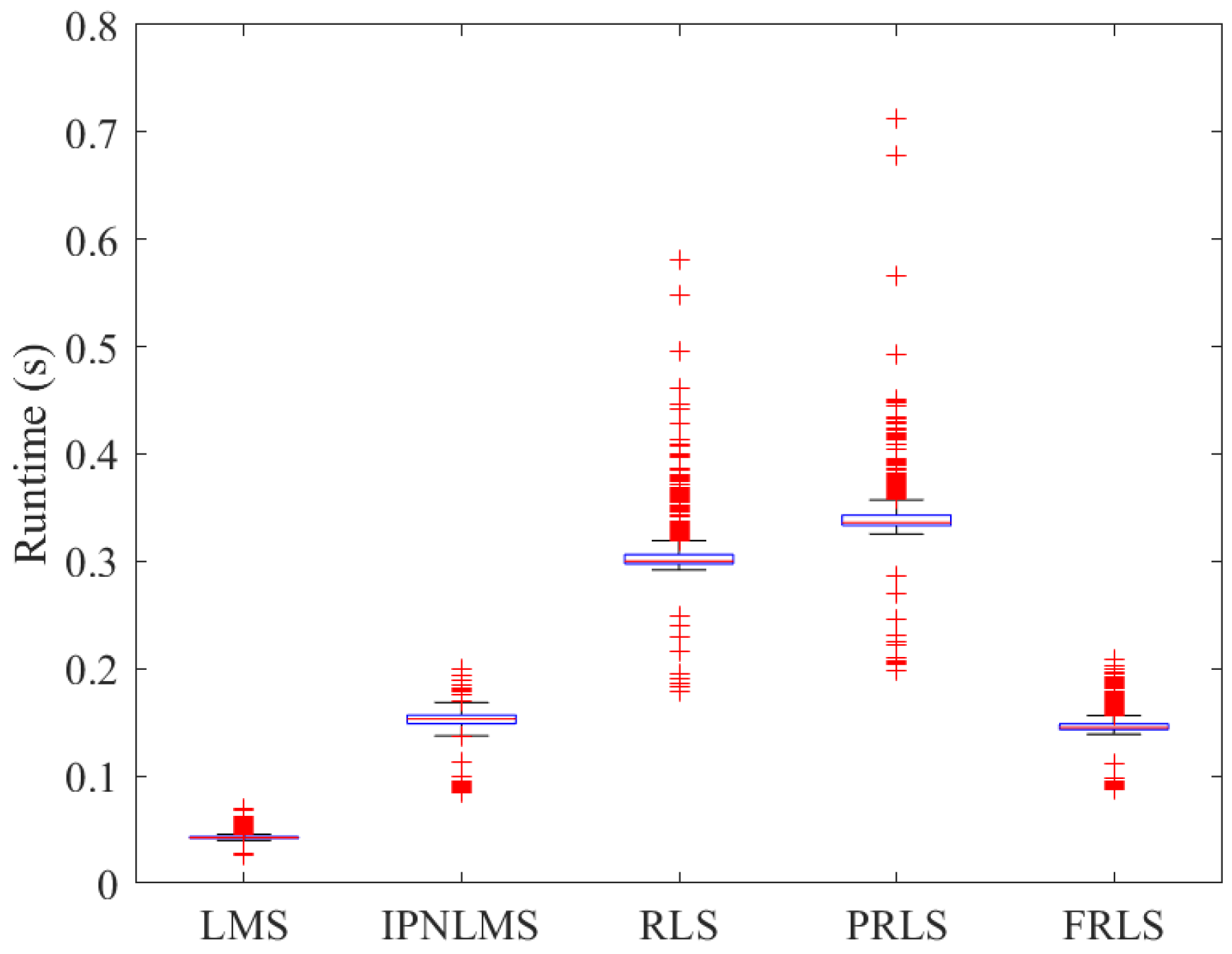

The LMS algorithm demonstrates a distinct advantage in computational efficiency, with its computational load primarily concentrated on the update of the filter weight vector and error calculation. In contrast, the IPNLMS algorithm introduces additional computational steps due to the incorporation of a scaling matrix, thereby slightly increasing its linear complexity. Both the RLS and PRLS algorithms exhibit second-order complexity; notably, the PRLS algorithm further elevates the computational complexity owing to the introduction of the scaling matrix. By comparison, although the computational complexity of the FRLS algorithm is marginally higher than that of LMS-type algorithms, it is significantly lower than that of the RLS and PRLS algorithms, achieving a reduced computational cost.

Using the runtime of algorithms as a rough estimate of computational complexity enables an intuitive comparison of the complexity differences among various algorithms. Herein, the “rough estimate” denotes the runtime required for each algorithm to attain a convergent state under an identical simulation environment. The simulation conditions are specified as follows. In each Monte Carlo run, we generate one transmitted sequence

and one channel realization

; the adaptive algorithm then processes the sample index

sequentially to estimate the same underlying channel within that run. We repeat independent Monte Carlo runs and average the runtime to obtain a statistically meaningful comparison. In our setup, each element of

follows

, and the channel taps are generated according to a Rician fading model with factor

. In our simulations, the Rician

-factor is set to

to emulate a dominant component plus scattered multipath components. The signal length is set to

and the SNR is configured to 20 dB, with the objective of minimizing the impact on the convergence speed of the algorithms. Each algorithm is independently executed

times to compute its average runtime. To minimize the interference from simulation parameters, each algorithm employs the values listed in

Table 2, fixedly during each iteration. The simulation results are presented in

Figure 4.

The blue box in

Figure 4 represents the interquartile range of the runtime, i.e., from the 25th to the 75th percentile; the length of the whiskers indicates the range of the runtime, excluding outliers; and the red plus signs denote the outliers in the runtime. As observed from

Figure 4, the runtime of the FRLS algorithm is comparable to those of the LMS and IPNLMS algorithms and lower than those of the RLS and PRLS algorithms, indicating that the FRLS algorithm achieves linear per-iteration complexity with respect to the channel length L (i.e.,

, consistent with the operation-count analysis in

Table 1).

3.2. Simulation of Noise Robustness for Estimation Algorithms for EM Wave Across Seawater–Air Channels

Interference in across seawater–air channels can significantly degrade the SNR at the receiver. Thus, testing the noise robustness of different algorithms is crucial for evaluating their performance in across seawater–air channel estimation. This subsection systematically investigates the noise robustness of the LMS, IPNLMS, RLS, PRLS, and FRLS algorithms under varying SNR conditions and propagation paths, followed by an analysis of the simulation results. The simulation environment and procedures are consistent with those described in the previous subsection.

Table 3 presents the algorithm parameters for the noise robustness simulation, where the parameter values are selected to balance the convergence speed and steady-state error as effectively as possible.

Parameter-selection protocol (fair comparison): For each estimator, key hyperparameters (e.g., step size μ for LMS-type methods, forgetting factor λ for RLS-type methods, and proportionate parameters for IPNLMS/PRLS) were selected using a consistent tuning budget to balance convergence speed and steady-state error under the same simulation setting. The final values are reported in

Table 2 and

Table 3. Qualitatively, larger λ improves steady-state accuracy for slowly varying channels but reduces tracking ability, whereas μ controls the convergence–noise-robustness trade-off.

To evaluate robustness under varying multipath conditions, we test one-, two-, and three-path channels representing typical seawater–air interface propagation scenarios.

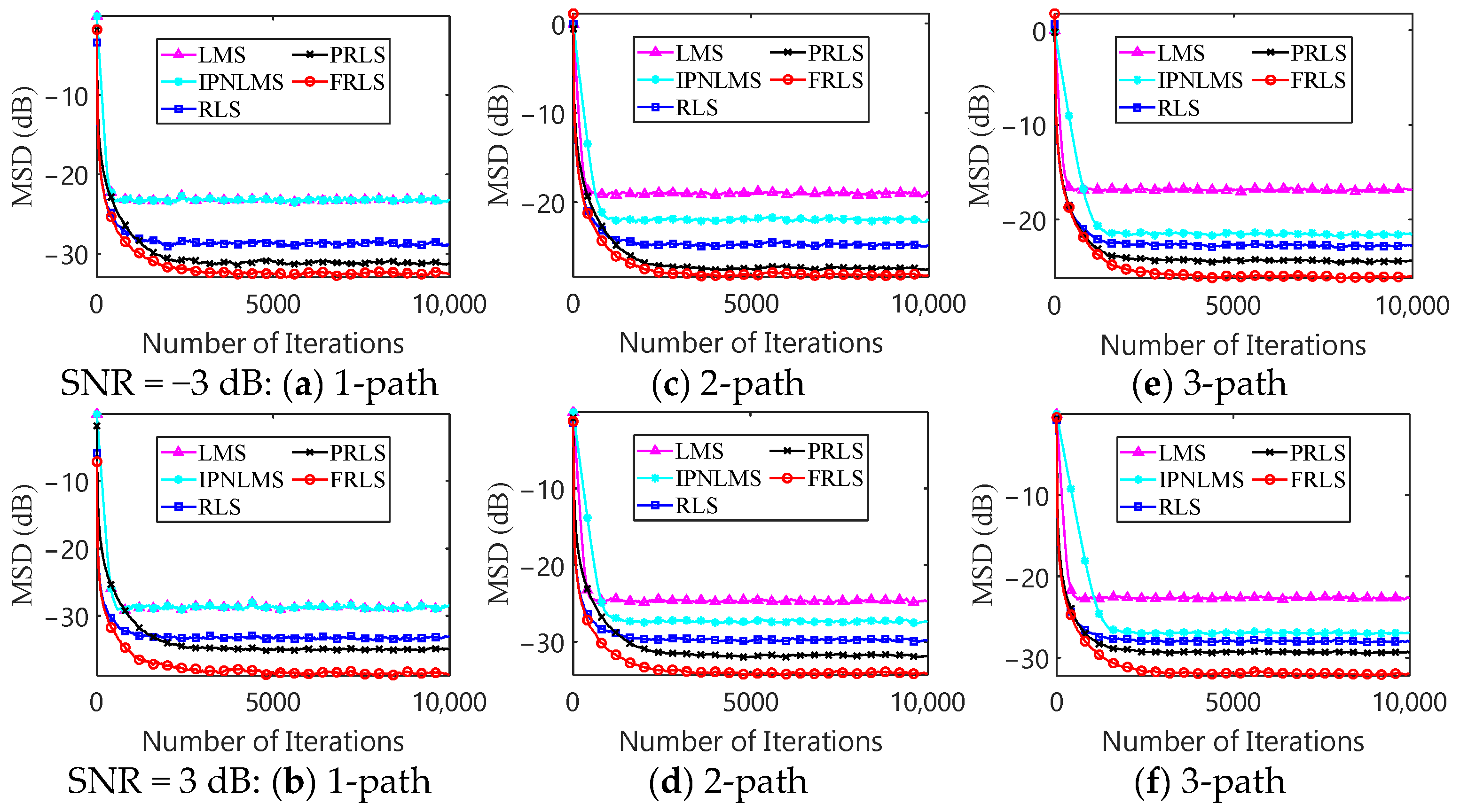

Figure 5 reports the MSD evolution of five estimators (LMS, IPNLMS, RLS, PRLS, and FRLS) under two SNR settings (SNR = −3 dB and SNR = 3 dB). In all subplots, the horizontal axis denotes the number of iterations, and the vertical axis denotes MSD (dB).

One-path case (

Figure 5a,b). In the single-path scenario, the channel is highly sparse and dominated by one effective tap. Under low SNR (

Figure 5a), the LMS- and IPNLMS-type algorithms converge to relatively high steady-state MSDs, indicating limited noise immunity of first-order adaptation in severely noisy conditions. In contrast, RLS-type estimators (RLS/PRLS/FRLS) yield substantially lower steady-state MSDs by exploiting second-order statistics, and FRLS achieves the lowest steady-state MSD among all algorithms. When SNR increases to 3 dB (

Figure 5b), the steady-state MSD of all methods decreases as the impact of noise is reduced. Nevertheless, FRLS still provides the best estimation accuracy, followed by PRLS, and both FRLS and PRLS reach a steady state after approximately 3000 iterations.

Two-path case (

Figure 5c,d). The two-path channel remains a sparse multipath scenario where only a small subset of FIR taps carries most of the energy. In such settings, proportionate adaptation is generally beneficial because it assigns larger adaptation weights to the dominant taps while suppressing the inactive ones, a behavior widely discussed in the proportionate NLMS/RLS literature for sparse system identification and adaptive equalization (e.g., PNLMS/IPNLMS and PRLS-type estimators) [

37,

38,

39]. This mechanism explains why IPNLMS slightly outperforms LMS in

Figure 5c under low SNR, although the overall performance remains constrained by the first-order update and noise sensitivity. In contrast, the RLS-type algorithms consistently achieve much lower steady-state MSDs due to their second-order nature. When SNR increases to 3 dB (

Figure 5d), the steady-state MSD of all algorithms further decreases, but FRLS remains the best-performing method and achieves the lowest steady-state MSD. Compared with PRLS, FRLS exhibits comparable convergence behavior while maintaining (or improving) steady-state accuracy in the two-path case, demonstrating strong robustness for sparse multipath cross-medium propagation.

Three-path case (

Figure 5e,f). With three propagation paths, the channel becomes less sparse and the estimation task becomes more challenging. In both low- and high-SNR conditions, RLS-type estimators still show a clear advantage over LMS-type estimators, consistently converging to lower steady-state MSDs. Notably, FRLS maintains the lowest steady-state MSD across both SNR settings, indicating that it can preserve high estimation accuracy even when the multipath structure becomes more complex.

Overall,

Figure 5 confirms that FRLS achieves the best noise robustness across different propagation-path settings and SNR conditions. Combined with the earlier complexity analysis and runtime comparison, these results indicate that FRLS provides an effective accuracy–complexity trade-off for cross-medium EM channel estimation, particularly in low-SNR scenarios.

4. Sea Experiment

This section validates the proposed single-carrier EM communication scheme across the seawater–air interface using offshore experiments. For clarity, we first describe the experimental site and setup as well as the transmitted signal/frame design, then summarize the receiver processing and channel-estimation configuration, and finally we report the results in terms of OSNR, reconstructed images, and BER distribution.

4.1. Experimental Site and Setup

To verify the feasibility of the method proposed in the previous section for cross-interface EM communication in a marine environment, a sea experiment was conducted offshore of Da Zhou Dao in the South China Sea, as shown in

Figure 6. The water depth in this area ranges from 30 to 40 m.

During the experiment, environmental parameters of this area were measured using a CTD (Conductivity, Temperature, Depth) profiler and a wave buoy system. The measured results indicate that the average seawater temperature was 26.7 °C, the salinity was 34 PSU, and the average seawater conductivity was 5.35 S/m. The wave height during the communication test ranged approximately from 0.5 m to 1.2 m.

The field experiment involved two vessels: a transmitter vessel and a receiver vessel. Upon arrival at the designated test site, both vessels remained stationary throughout the experiment. The distance between the transmitter and receiver devices was calculated using GPS data. An electric dipole transmitter was deployed from the side of the transmitter vessel. The near-end electrode was fixed 2 m above the transmitter cabin, while the far-end electrode was suspended beneath a small auxiliary boat positioned approximately 20 m away. The immersion depth of both electrodes ranged between 3 and 4 m. On the receiver side, the receiving unit was attached to a buoy deployed from the side of the receiver vessel, with the sensor submerged to a depth of approximately 4 m.

During the experiment, a computer controlled the signal generator at the transmitter side to produce the analog waveform. This waveform was subsequently amplified by a power amplifier and used to drive the underwater antenna to emit EM waves. At the receiver side, a magnetic rod sensor was used to convert the received EM signals into voltage signals. These signals were then preprocessed through amplification and filtering before being sampled via an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) and stored locally for subsequent algorithm validation.

4.2. Transmitted Signal Design and Frame Structure

A binary image with a resolution of 100 × 100 pixels, as shown in

Figure 7, was used as the transmitted information, comprising a total of 104 bits. In the experiment, a 4PSK modulation scheme was employed, and these bits were mapped onto 5 × 10

3 complex-valued symbols. The key transmission parameters used in the system design are summarized in

Table 4. According to the configuration of the transmitter’s signal generator, the update rate of the transmitted waveform was set to 192 kHz, with a roll-off factor of 0.25.

The bandwidth, which is 0.2 times the center frequency, was 1.6 kHz. The transmitted data adopts a block-based design, where each segment of transmitted data can contain multiple data blocks, and each data block includes 225 training symbols and 900 information symbols. A total of six data blocks were formed in the experiment, among which the last data block was extended to 900 symbols by means of zero-padding. The linear frequency-modulated (LFM) signal and blank interval had durations of 0.1 s and 2 s, respectively. The specific transmission signal format is shown in

Figure 8. The up-LFM signal, indicated by the red ascending lines, is placed at the start of each frame, while the down-LFM signal, represented by the red descending lines, is placed at the end of the final frame. These were designed for frame timing and synchronization. The blank interval was designed to meet the power amplifier requirements, ensuring continuous operation. The first two frames had the same length, each being 6.1 s, while the third frame was 5.17 s.

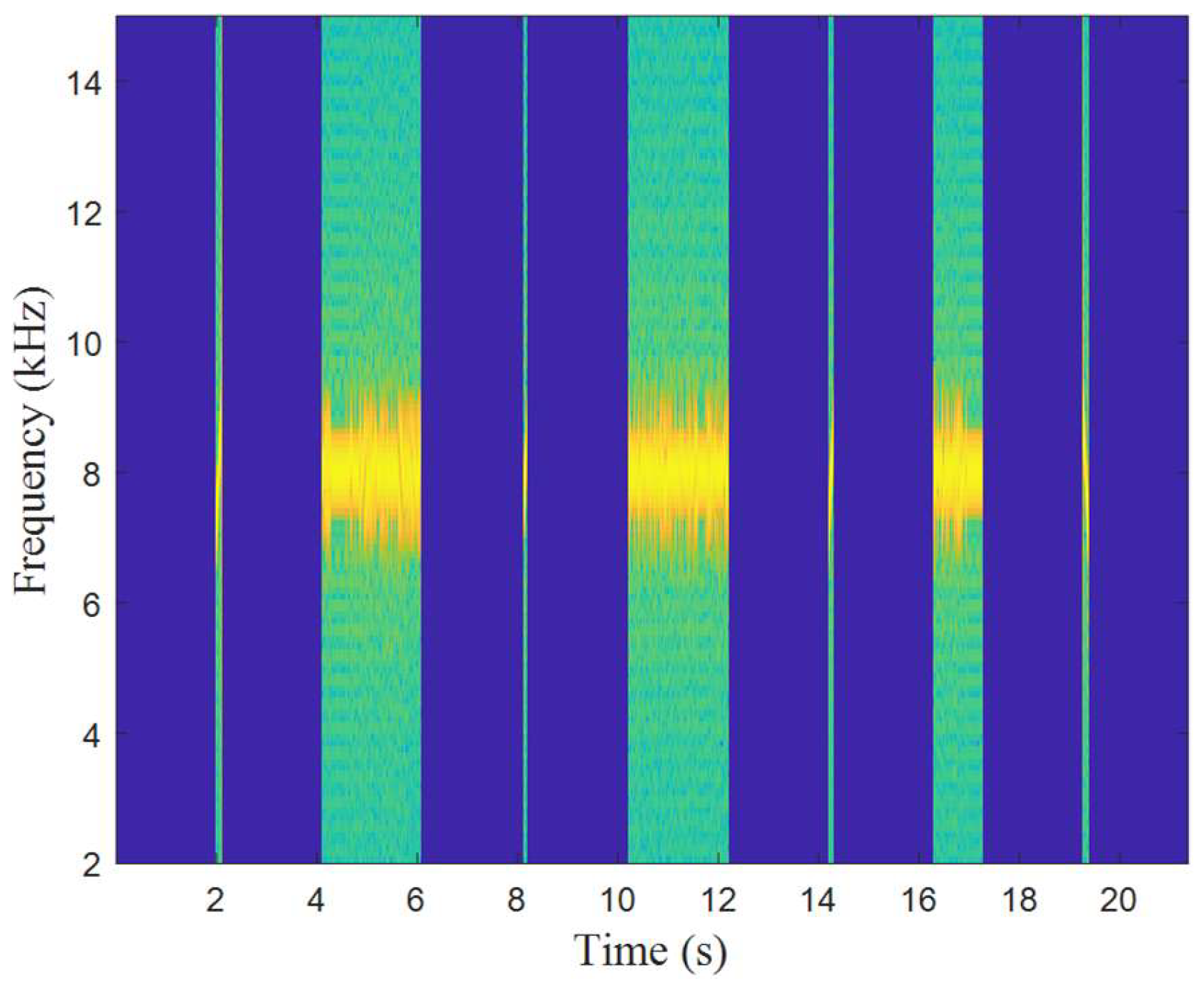

Figure 9 shows the short-time Fourier transform (STFT) of the transmitted signals. The LFM segment is used only as a synchronization/preamble component for robust frame detection and segmentation; it is not used for sensing/ISAC, and QPSK data are transmitted in separate data blocks. In the frequency domain, the signal strength and the rising and falling trends of the up- and down-LFM signals are clearly visible.

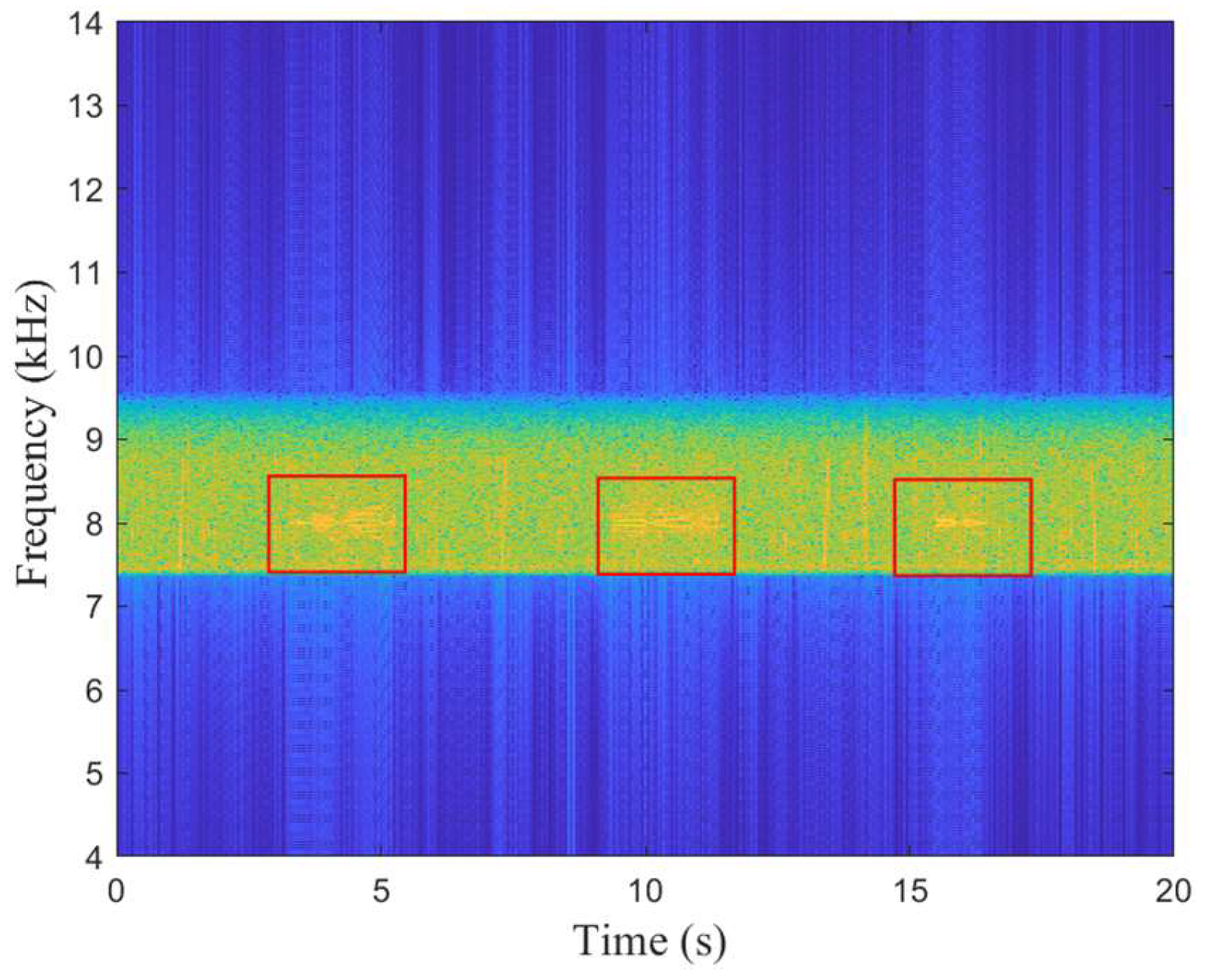

We sampled the received signals at the receiver end with a sampling frequency of 128 kHz.

Figure 10 shows the STFT of the received signal. The valid information in the frequency domain is highlighted in black boxes. It is clearly observed that the signal strength of the valid data is higher than the blank intervals before and after. Finally, the signal can be fully received within 20 s.

4.3. Receiver Processing and Channel-Estimation Configuration

The receiver processing follows

Figure 1. The LFM preamble is first detected to locate the frame boundaries and remove blank/guard intervals. Training symbols are then extracted to estimate the discrete-time complex FIR channel. In this work, FRLS (and the baseline estimators) is applied to the training symbols for channel estimation (adaptive filtering), and the obtained channel estimate is subsequently used to build an MMSE equalizer for QPSK data recovery (equalization). The OSNR and BER-distribution metrics reported in

Section 4.4 are computed after this consistent pipeline.

This section employs five algorithms for channel estimation, namely the LMS, IPNLMS, RLS, PRLS, and FRLS algorithms, with relevant parameters specified in

Table 5. Owing to the offshore experimental environment being more complex and harsh than the simulation environment, the parameters used in this section differ from those described in the previous section. These discrepancies mainly manifest in the actual channel conditions and noise environment of the experiment, necessitating corresponding adjustments to the channel estimation algorithms to adapt to the across seawater–air signal characteristics in real-world scenarios.

4.4. Results and Discussion (OSNR, Reconstruction Quality, and BER Distribution)

In addition to characterizing algorithm performance using the bit-error rate (BER), this section introduces the output signal-to-noise ratio (OSNR, unit: dB) as a metric for assessing algorithm accuracy. The OSNR is defined as follows:

where

is the transmitted symbol and

is the output symbol of the equalizer. As indicated by (52), a larger OSNR implies higher accuracy of the channel estimation algorithm.

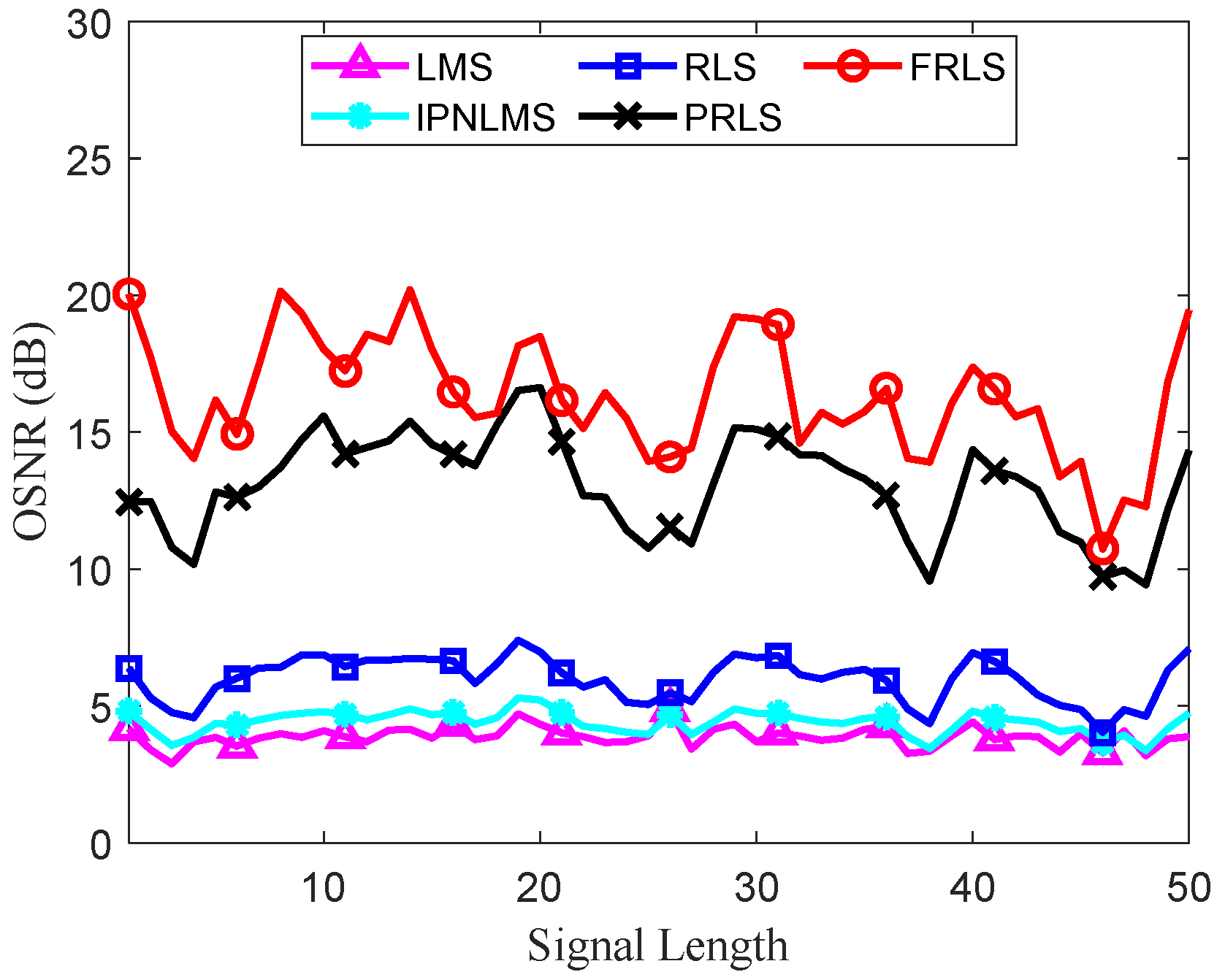

Figure 11 presents a comparison of the OSNRs of different algorithms in the experiment. The horizontal axis represents the length of the intercepted signal, and the vertical axis denotes the average OSNR. It can be observed that the FRLS algorithm outperforms the other algorithms in terms of accuracy, with a relatively high OSNR. The PRLS algorithm follows, exhibiting sub-optimal precision. The LMS algorithm achieves the lowest OSNR, indicating that its accuracy is relatively low under poor SNR conditions.

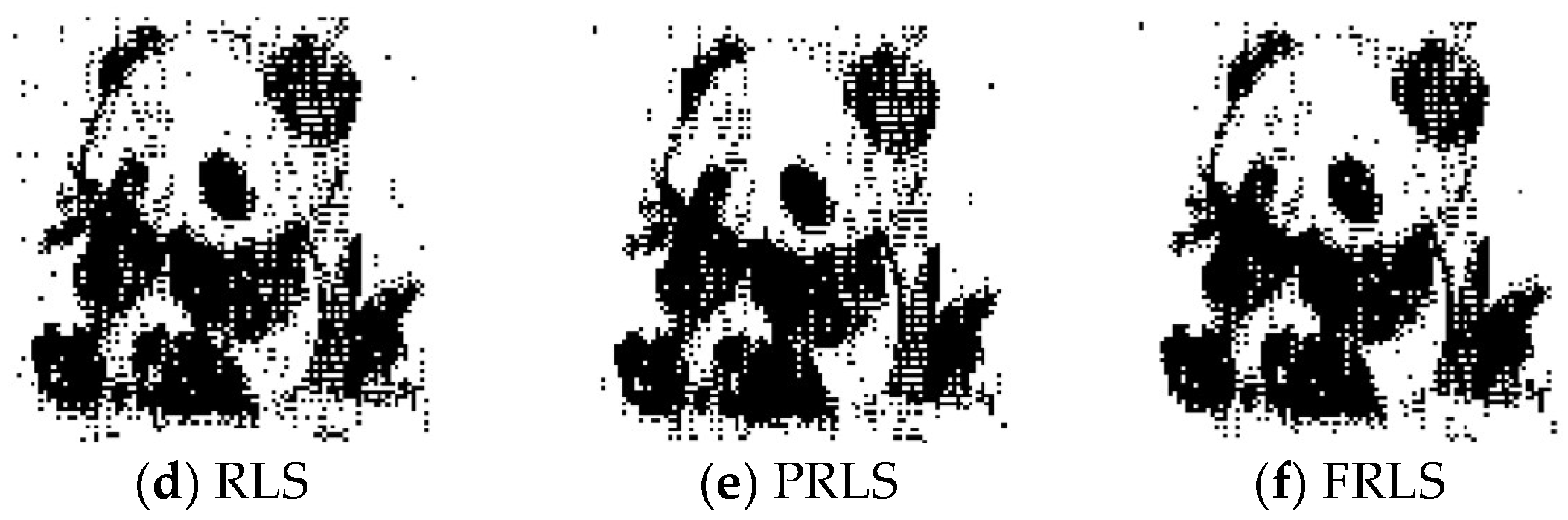

After channel estimation, this section employs a minimum mean-square error (MMSE) equalizer to reconstruct the transmitted signal and further calculates the BER. The BER percentage is introduced to elaborate on the performance of the algorithms across different BER intervals, which are 0, [0, 10

−3], [10

−3, 10

−2], [10

−2, 10

−1], and 1. A higher BER indicates lower reliability of the algorithm: a BER of 1 means all the demodulated information within the sub-block is incorrect, while a BER of 0 implies all the demodulated information in the sub-block is correct. The interval-specific BER is calculated as follows: The demodulated bits are partitioned into

blocks, where the first

blocks have the same size, and the last block stores the remaining bits. Then, the number of sub-blocks corresponding to the five BER intervals, denoted as

, is counted. The formula for the BER interval is the following:

For fairness, the number of bit blocks is set to a fixed value of 900 in the subsequent calculations, i.e., .

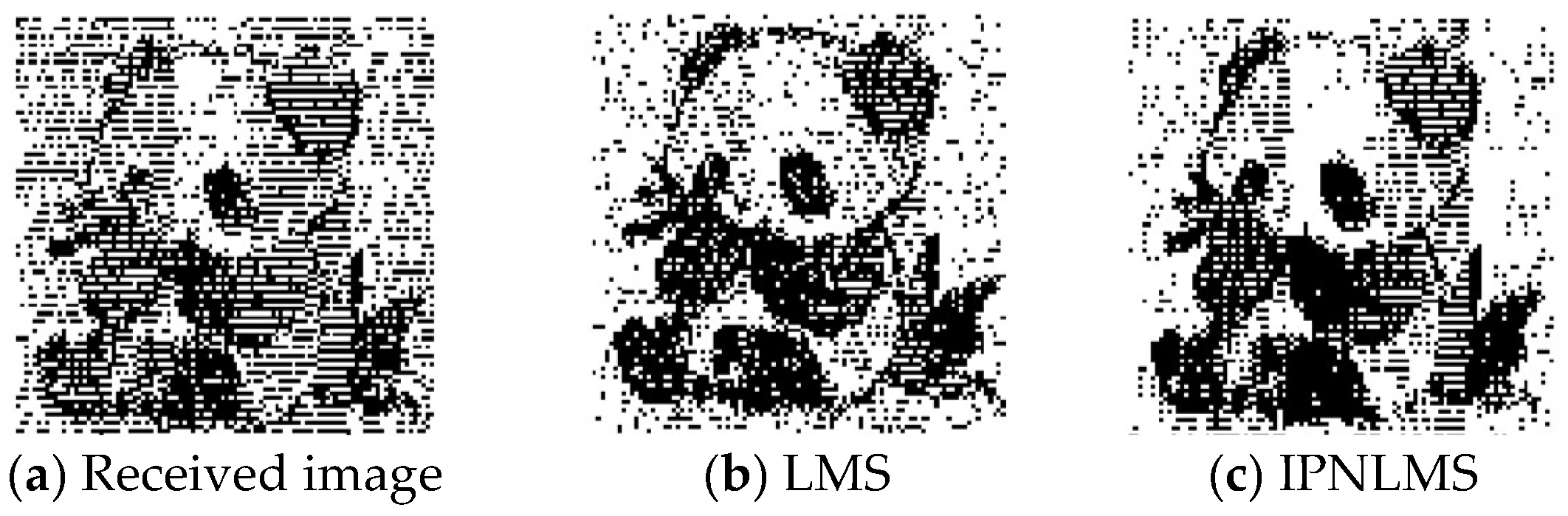

As illustrated in

Figure 11, images reconstructed by the MMSE equalizer driven by different algorithms exhibit intuitive differences in algorithm accuracy.

Figure 12a shows the original received image without channel estimation, while

Figure 12b–f correspond to the images reconstructed using the LMS, IPNLMS, RLS, PRLS, and FRLS algorithms (hereafter referred to as *algorithm-driven images*), respectively. It can be observed that the clarity of the LMS-driven image is significantly higher than that of the original received image but remains inferior to the images reconstructed by RLS-type algorithms. Among the RLS-type images, the FRLS-driven image resembles the PRLS-driven counterpart, with comparable clarity and fewer noise artifacts, indicating a lower bit-error rate for both algorithms.

Figure 13 depicts the BER percentage distribution, where distinct colors correspond to specific BER intervals: black BER = 0, green for [0, 10

−3], blue for [10

−3, 10

−2], red for [10

−2, 10

−1], and yellow for [10

−1, 1]. Notably, the green and blue intervals are not visible in

Figure 13, attributed to the inherent uncertainties in offshore experimental data. Thus, the BER distribution derived from the received data fails to exhibit the uniform pattern observed in the simulations. Altering the number of blocks

only modifies the trend of BER interval proportions but cannot induce the emergence of intervals [0, 10

−3] that are absent in the experimental data. From

Figure 13, the LMS algorithm dominates the [10

−1, 1] interval, accounting for 22.23% more than the FRLS algorithm. In contrast, the FRLS algorithm exhibits the highest proportion in the [10

−2, 10

−1] interval among all algorithms. In summary, the FRLS algorithm successfully achieves an effective balance between computational efficiency and estimation accuracy in offshore experiments for communication across seawater–air.

4.5. Limitations and Scope

The offshore data are processed offline on the recorded receiver waveform using a consistent pipeline (LFM-based segmentation, training extraction, training-based estimation, and MMSE equalization). The channel is treated as slowly varying within each processing window; wave-induced fast dynamics are not explicitly modeled. Although temperature, salinity, conductivity, and wave height were measured, a calibrated background EM noise-floor measurement was not conducted, so background noise is treated as part of the effective interference/noise in the recorded bursts. These factors limit a direct physics-to-FIR mapping and detailed modem-impairment decomposition. Future work will incorporate dedicated environmental/noise measurements and explicit time-varying channel models to further strengthen end-to-end evaluation.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed a complex Fast Recursive Least-Squares (FRLS) channel-estimation algorithm tailored for single-carrier electromagnetic (EM) communication across the seawater–air interface. By redesigning the input-data structure and adopting a forward–backward joint estimation strategy, FRLS reduces the per-iteration computational cost from the quadratic complexity of classical RLS to a linear form with respect to the channel length (i.e., from to ), while preserving high estimation accuracy. This design targets practical cross-medium EM links where hardware resources and processing latency are tightly constrained.

Comprehensive simulations under representative one-, two-, and three-path channels demonstrate that FRLS consistently achieves the lowest steady-state MSD compared with LMS, IPNLMS, RLS, and PRLS, especially in low-SNR conditions (e.g., −3 dB). Runtime comparisons further indicate that FRLS attains an accuracy–complexity trade-off close to LMS-type methods but with markedly better estimation performance and with substantially lower computational burden than conventional RLS-type methods.

Marine field experiments conducted in August 2024 in the South China Sea further validate the practical effectiveness of FRLS. In our end-to-end receiver chain, an LFM segment is used only as a synchronization preamble for reliable frame detection (rather than for sensing/ISAC), training symbols are used for FRLS-based channel estimation, and the resulting channel estimate is applied to construct an MMSE equalizer for QPSK data recovery. Under real offshore channel conditions and interference/noise, FRLS yields higher OSNR and improves the BER distribution; for example, the proportion of sub-blocks with is reduced by 22.23% relative to LMS, and the equalized reconstructed images exhibit visibly fewer artifacts. These results confirm that FRLS is a practical, hardware-friendly solution for improving reliability in cross-medium EM communications.

This study employs an equivalent discrete-time FIR model for estimation and focuses on algorithmic robustness, while a full physics-to-tap mapping (e.g., conductivity, permittivity, temperature/salinity, antenna geometry, and sea state) is not explicitly reconstructed. The offshore segments are treated as slowly time-varying within each processing window, and wave-induced fast dynamics are not explicitly modeled. Moreover, a calibrated background EM noise-floor measurement was not conducted during this campaign, which limits direct correlation between measured channel variations and ocean conditions. Future work will incorporate dedicated environmental/noise measurements and explicit time-varying channel models, investigate adaptive parameter tuning (e.g., ) under dynamic channels, and evaluate end-to-end coded transmission under the same low-complexity estimation framework. In addition, although this work focuses on a narrowband single-carrier link, the proposed FRLS framework can be further extended to multi-carrier or wideband EM communication systems. For OFDM/FBMC, FRLS can be applied (e.g., on pilot-bearing resources) to recursively track per-subcarrier complex channel gains while maintaining low per-iteration complexity. For wideband single-carrier transmission, FRLS can be used to estimate a longer FIR channel that captures frequency selectivity, followed by conventional frequency-domain equalization. Further extensions, such as sparsity-aware constraints for delay-domain sparse channels and variable-forgetting-factor designs to better handle abrupt interface-induced variations, are also promising directions for future work.

Overall, the proposed FRLS provides a practical and hardware-friendly solution for reliable cross-medium EM communications under stringent complexity constraints.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W. and Y.R.; methodology, H.W. and Y.W.; software, Y.W.; validation, H.W.; formal analysis, Y.W. and J.S.; investigation, J.S. and L.D.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W. and Y.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.R. and L.D.; visualization, L.D.; supervision, Y.R.; project administration, H.W.; funding acquisition, H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number U2341201 and 52271350, the Basic Product Innovation Research Project grant number 1452-0208040, and the Hanjiang National Laboratory, Project No. ZC2024005.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Li Fei for his invaluable guidance and support throughout the manuscript revision, project administration, and funding acquisition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jahanbakht, M.; Xiang, W.; Hanzo, L.; Azghadi, M.R. Internet of Underwater Things and Big Marine Data Analytics—A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 904–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Ji, F.; Wang, Y.; Yao, K.; Chen, F. Space–Air–Ground–Sea Integrated Network with Federated Learning. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, M. Underwater Acoustic Communications: Design Considerations on the Physical Layer. In Proceedings of the 2008 Fifth Annual Conference on Wireless on Demand Network Systems and Services, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, 23–25 January 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Shu, H.; Liang, Q.; Du, D.H.C. Silent Positioning in Underwater Acoustic Sensor Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2008, 57, 1756–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhang, X.; Luo, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Guan, X. Asynchronous Localization With Mobility Prediction for Underwater Acoustic Sensor Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2018, 67, 2543–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.K.; Wong, K.T. Recursive Least-Squares Source Tracking using One Acoustic Vector Sensor. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2012, 48, 3073–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ren, Y.; Yang, K. Electromagnetic field produced by radiation source submerged in non-homogeneous seawater. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shamma’a, A.I.; Shaw, A.; Saman, S. Propagation of Electromagnetic Waves at MHz Frequencies Through Seawater. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2004, 52, 2843–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; Wells, I.; Dickers, G.; Kear, P.; Gong, X. Re-evaluation of RF Electromagnetic Communication in Underwater Sensor Networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2010, 48, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.F.; Jayakody, D.N.K.; Chursin, Y.A.; Affes, S.; Dmitry, S. Recent Advances and Future Directions on Underwater Wireless Communications. Arch. Comput. Method Eng. 2020, 27, 1379–1412. [Google Scholar]

- MN, S.P.; Tok, R.U.; Fereidoony, F.; Wang, Y.E.; Zhu, R.; Propst, A.; Bland, S. Magnetic Pendulum Arrays for Efficient ULF Transmission. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gong, S.; Liu, Q.; Hou, M. A Mechanical Transmitter for Undersea Magnetic Induction Communication. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2021, 69, 6391–6400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cui, Y.; Song, X.; Zhong, J.; Wei, M.; Wu, M.; Yuan, H. Model, Design, and Testing of an Electret-Based Portable Transmitter for Low-Frequency Applications. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2021, 69, 5305–5314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xiao, D.; Gong, S.; Wu, J.; Jiang, W.; Hong, T. Magneto-Mechanical Antenna Array for Extremely Low-Frequency Communication. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2024, 23, 4189–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, J. Rotating Magnet-Based Mechanical Antenna for Magnetic Inductive Communications. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2024, 72, 5502–5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Russian Engineers Developed the Innovation Portable Device of an Underwater Radio Communication. Available online: https://tadviser.com/index.php/Product:IVA_S_W_Mobile_radio_complex_of_wireless_underwater_communication (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Smolyaninov, I.; Balzano, Q.; Barry, M.; Young, D. Superlensing enables radio communication and imaging underwater. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, E.; Quintana, G.; Mena, P.; Dorta, P.; Perez-Alvarez, I.; Zazo, S.; Perez, M.; Quevedo, E. Investigation on radio wave propagation in shallow seawater: Simulations and measurements. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Third Underwater Communications and Networking Conference (UComms), Lerici, Italy, 30 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Sun, Z.; Wang, P. Multiple Frequency Band Channel Modeling and Analysis for Magnetic Induction Communication in Practical Underwater Environments. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 66, 6619–6632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Tang, X.; Tharmarasa, R.; Kirubarajan, T.; Jassemi, R.; Halle, S. Underwater Target Tracking in Uncertain Multipath Ocean Environments. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2020, 56, 4899–4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, W. TDOA and Doppler estimation for cyclostationary sgnals based on multi-cycle frequencies. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2008, 44, 1251–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babadi, B.; Kalouptsidis, N.; Tarokh, V. SPARLS: The sparse RLS algorithm. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2010, 58, 4013–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, G.; Jin, J.; Gu, Y.; Wang, J. Performance analysis of l0-norm constraint least mean square algorithm. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2012, 60, 2223–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Yang, K.; Sheng, X.; Huang, F. A blocked MCC estimator for group sparse system identification. AEU-Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2020, 115, 153033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Tong, F.; Zhou, Y. Enhanced Sparsity-aware RLS Algorithm for Efficient Estimation of Time-varying Sparse System. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II-Express Briefs 2023, 70, 4589–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Tao, J.; Xia, Y. A Proportionate Recursive Least Squares Algorithm and Its Performance Analysis. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II-Express Briefs 2021, 68, 506–510. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Z.; Tao, J.; Xia, Y.; Yang, L. Proportionate RLS with l1-norm regularization: Performance analysis and fast implementation. Digit. Signal Process. 2022, 122, 103366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleologu, C.; Benesty, J.; Ciochină, S. Data-reuse recursive least-squares algorithms. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2022, 29, 752–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K. Research on Cross-Sea-Air Low-Frequency Wireless Communication System Technology; Central China Normal University: Wuhan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Z.; Tao, J.; Tong, F.; Zhang, H.; Qu, F.; Han, X. A Fast Proportionate RLS Adaptive Equalization for Underwater Acoustic Communications. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2019—Marseille, Marseille, France, 17–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Meena, S.R.; Rai, C.S. Channel Estimation using SC-PRLS for underwater Communication. In Proceedings of the 2023 14th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Delhi, India, 6–8 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, X.; Wei, Y.; Qu, F.; Song, A. Low Computational Complexity RLS-Based Decision-Feedback Equalization in Underwater Acoustic Communications. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 49, 1067–1088. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, H.; Pan, X.; Jiang, J.; Li, X.; Zheng, L. Adaptive and Robust Channel Estimation for IRS-Aided Millimeter-Wave Communications. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 9411–9423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, D.; Li, L.; Zakharov, Y.; Miao, Y.; Huang, Z. A General Constrained Adaptive Filtering Algorithm for SISO Channel Estimation and Beamforming. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 2770–2782. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, K. Efficient Method for Solving Underwater Electromagnetic Fields Generated by Radiation Sources in Seawater. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2024, 23, 1638–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Yang, K.; Ma, Y. Verification and Evaluation of Lateral Wave Propagation in Marine Environment. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2020, 19, 2413–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duttweiler, D.L. Proportionate normalized least-mean-squares adaptation in echo cancelers. IEEE Trans. Speech Audio Process. 2000, 8, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benesty, J.; Gay, S.L. An improved PNLMS algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, Orlando, FL, USA, 13–17 May 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, H.; Doroslovacki, M. Proportionate adaptive algorithms for network echo cancellation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2006, 54, 1794–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic of propagation paths of EM wave across seawater–air interface.

Figure 1.

Schematic of propagation paths of EM wave across seawater–air interface.

Figure 2.

Overall transmitter–receiver workflow for cross-medium EM communication.

Figure 2.

Overall transmitter–receiver workflow for cross-medium EM communication.

Figure 3.

Data structure in the FRLS algorithm.

Figure 3.

Data structure in the FRLS algorithm.

Figure 4.

Comparison of runtime among different algorithms.

Figure 4.

Comparison of runtime among different algorithms.

Figure 5.

Comparison of noise robustness among different algorithms under different numbers of propagation paths (SNR = −3 dB and SNR = 3 dB).

Figure 5.

Comparison of noise robustness among different algorithms under different numbers of propagation paths (SNR = −3 dB and SNR = 3 dB).

Figure 6.

Sea experiments site.

Figure 6.

Sea experiments site.

Figure 7.

The transmitted figure.

Figure 7.

The transmitted figure.

Figure 8.

The transmitted signals.

Figure 8.

The transmitted signals.

Figure 9.

The short-time Fourier transform (STFT) of the transmitted signals. (Among these lines, the narrower green line represents the positioning signal of each frame, while the yellow segment within the wider green line denotes the valid data segment in each frame).

Figure 9.

The short-time Fourier transform (STFT) of the transmitted signals. (Among these lines, the narrower green line represents the positioning signal of each frame, while the yellow segment within the wider green line denotes the valid data segment in each frame).

Figure 10.

The STFT of the received signals. (The red box marks the valid signal region in the frequency domain).

Figure 10.

The STFT of the received signals. (The red box marks the valid signal region in the frequency domain).

Figure 11.

Comparison of OSNR among different algorithms in across seawater–air channel estimation.

Figure 11.

Comparison of OSNR among different algorithms in across seawater–air channel estimation.

Figure 12.

Images reconstructed by the MMSE equalizer driven by different channel estimation algorithms.

Figure 12.

Images reconstructed by the MMSE equalizer driven by different channel estimation algorithms.

Figure 13.

Percentage distribution of BER in offshore Experiment 1 for communication across the seawater–air.

Figure 13.

Percentage distribution of BER in offshore Experiment 1 for communication across the seawater–air.

Table 1.

Comparison of computational complexities among different algorithms.

Table 1.

Comparison of computational complexities among different algorithms.

| Algorithm | Computational Complexity |

|---|

| + | × | ÷ | Total |

|---|

| LMS | | | \ | |

| IPNLMS | | | | |

| RLS | | | | |

| PRLS | | | | |

| FRLS | | | | |

Table 2.

Algorithm parameters for computational complexity simulation.

Table 2.

Algorithm parameters for computational complexity simulation.

| Algorithm | Parameters |

|---|

| | | | |

|---|

| LMS | 3 × 10−3 | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| IPNLMS | 5 × 10−3 | \ | −0.5 | 10−4 | \ |

| RLS | \ | 0.999 | \ | \ | \ |

| PRLS | \ | 0.999 | −0.5 | 10−4 | \ |

| FRLS | \ | 0.999 | \ | \ | 0.1 |

Table 3.

Algorithm parameters for noise robustness simulation.

Table 3.

Algorithm parameters for noise robustness simulation.

| Algorithm | Parameters |

|---|

| | | | | |

|---|

| LMS | 8 × 10−3 | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| IPNLMS | 8 × 10−3 | \ | −0.5 | 10−4 | \ | \ |

| RLS | \ | 0.998 | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| PRLS | 0.5(when L = 1);

L − 1(when L > 1) | 0.998 | −0.5 | 10−4 | \ | \ |

| FRLS | \ | 0.998 | \ | \ | 0.25 | 0.1 |

Table 4.

Marine yield experiment parameters.

Table 4.

Marine yield experiment parameters.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|

| Sampling frequency | 192 kHz |

| Centre frequency | 8 kHz |

| Band width | 1.6 kHz |

| Symbol rate | 1.28 kBaud/s |

| Rolling-off factor | 0.25 |

Table 5.

The algorithm parameters used in marine yield experiments.

Table 5.

The algorithm parameters used in marine yield experiments.

| Algorithm | Parameters |

|---|

| | | | | |

|---|

| LMS | 5 × 10−3 | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| IPNLMS | 0.15 | \ | −0.2 | 10−4 | \ | \ |

| RLS | \ | 0.999 | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| PRLS | 1 | 0.999 | −0.2 | 10−4 | \ | \ |

| FRLS | \ | 0.999 | \ | \ | 1 | 0.1 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |