Abstract

Acoustic propagation in the ice cover of the Polar Ocean is of increasing interest from both scientific and engineering perspectives. The low-frequency elastic waves propagating in floating ice are primarily governed by waveguides stemming from the layered structure of the medium. For shallow water areas, experimental observation indicates that two Scholte-like waves are observed at low frequencies, i.e., the quasi-Scholte (QS) and Scholte–Stoneley (SS) waves, which are different from deep-sea cases. Due to the finite depths of ice, water, and sediment layers, both waves are dispersive. By modeling the waveguide of an ice-covered shallow-water (ICSW) system, the dispersion characteristics of both waves are derived, validated through numerical simulation, and analyzed with respect to layer structure for both soft and hard sediment. Results indicate a consistent conclusion; the QS wave exhibits a unique sensitivity to ice thickness, whereas the SS wave shows marginal sensitivity to ice thickness, and is controlled by the ratio of water depth to sediment depth, regardless of their absolute values. Based on these dispersion characteristics, a two-step inversion procedure is developed and applied to the synthetic signals from a numerical simulation. The conditional observability of the SS wave at the ice surface is also investigated and discussed.

1. Introduction

Ice cover is the most distinctive feature that differentiates water bodies in cold regions, such as the Arctic Ocean, from those in temperate environments. It forms a boundary between the ocean and the atmosphere, effectively blocking the exchange in energy, momentum, and mass, and thereby creating the unique marine environment of the Arctic [1,2,3]. With ongoing climate change in recent decades, the observation and monitoring of Arctic sea ice have become increasingly important and of great interest to scientists. Among various techniques, acoustic methods have been applied to geophysical and oceanographic studies in the Arctic since the 1950s. Numerous studies have investigated and modeled acoustic propagation within sea ice, aiming to improve understanding and characterization [4,5,6].

The central Arctic Ocean features water depths of several kilometers, and is typically classified as a deep-water environment. In the 1960s, Hunkins conducted an extensive sea-ice acoustic experiment in the Arctic to measure longitudinal and shear wave velocities [7]. Later, Yang et al. used a three-component seismometer array to characterize the elastic waveguide experimentally [8]. Dosso et al. estimated the azimuth of acoustic sources in the Arctic by exploiting the distinct polarization states of elastic waves, also using a three-component seismometer [9]. More recently, Moreau et al. deployed an array of 247 seismometers near Svalbard to observe seismic guided waves, particularly the quasi-Scholte (QS) wave, within sea ice and to infer its structural and elastic properties [5,10,11]. Parallel to experimental studies, considerable efforts have been devoted to analytical modeling. As early as 1951, Press derived the characteristic equations for elastic wave propagation in floating ice [12]. Subsequent studies on elastic waveguides in floating ice sheets primarily focused on the leaky nature of the modes under the assumption of infinite water depth [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. With these advances, the flexural wave initially described has been more precisely identified as the QS wave, which dominates the ice-waveguide modes from an energy perspective.

In recent years, seismic observations of ice over shallow water have revealed the existence of more than one Scholte-like mode. Beginning in 2013, Johansen et al. carried out multiple seismic experiments near Van Mijenfjorden in Svalbard, Norway, to investigate the propagation of sea-ice flexural and Scholte waves in shallow ice-covered waters. They also highlighted the potential of Scholte waves for geological surveys [20,21,22,23]. In 2024, Sobisevich et al. analyzed an Arctic-type seismo-acoustic waveguide based on seismic experiments in Naismeri Bay of Lake Ladoga, Republic of Karelia, Russia [24]. In these experiments, the QS mode propagating along the ice-water interface remained the most prominent in acoustic observations, but an additional Scholte-like mode at the water–sediment interface, termed the Scholte–Stoneley (SS) wave, was also observed, often overlapping with the QS wave. Experimentally, the SS wave has been consistently detected, yet it is absent in earlier analytical models, which neglected the water–seabed interface. Johansen et al. analyzed the SS wave using a simplified model that ignored the ice and assumed infinite water depth, the results of which are not fully validated [21]. To achieve a more reliable interpretation of experimental observations and a deeper understanding of Scholte-like wave propagation, modeling of ice-covered shallow water (ICSW) must incorporate both fluid–solid interfaces, i.e., water–ice and water–seabed interfaces.

In this study, we present both modeling and analytical efforts on guided wave modes in ice-covered shallow water. In Section 2, we establish a coupled ICSW waveguide model that more closely represents the real environment and verify its dispersive and multimodal properties through numerical simulation. In Section 3, we investigate the sensitivity of QS and SS waves to ice thickness, water depth, and sediment depth with respect to layer structure for both soft and hard sediment. In Section 4, we develop a two-step inversion procedure for estimating ice thickness and water/sediment depth and apply it to the numerical data. Finally, in Section 5, we study and discuss the conditional observability of the SS wave at the ice surface using numerical simulations.

2. Modeling and Verification

As mentioned in Section 1, except for QS waves, the presence of SS waves in ice cover at low frequency (<300 Hz) has been previously reported by [20,21,24] in shallow waters of Svalbard and Lake Ladoga within or near the Arctic region. Although attempts have been made to interpret these observations analytically, conventional models remain inadequate for describing the propagation characteristics in such systems. Classical models of ice-sheet waveguides typically assume infinite water depth [12], which is appropriate in the Arctic ocean where sea-ice thickness is generally less than 6 m and the bathymetry is on the order of hundreds of meters. However, such models fail for ice-covered shallow water, as the omission of the water–seabed interface prevents the emergence of the SS wave.

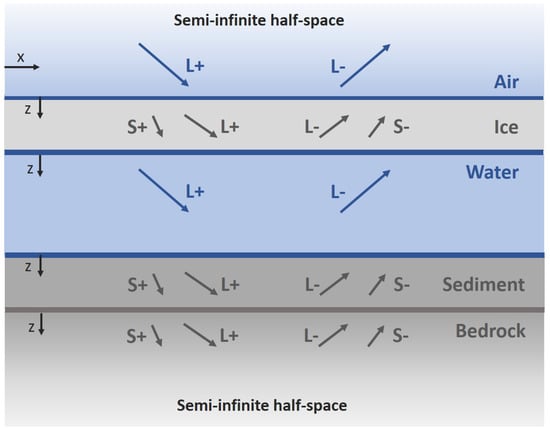

For a more comprehensive understanding of the low-frequency wavefield in ice cover over shallow water—particularly the QS and SS waves—a two-dimensional analytical model is developed using the Displacement Potential Function Method. As illustrated in Figure 1, the propagation system is represented by five horizontal layers. In addition to the conventional air-ice-water system, the seabed is incorporated following the work of [25], where it is divided into a finite-thickness soft layer (sediment) and an infinitely deep hard layer (bedrock). In the Cartesian coordinate system, the x-axis denotes the waveguide direction, and the z-axis represents the vertical direction, positive downward.

The five layers of the ICSW system are shown in Figure 1 as color blocks (blue for fluids, gray for solids), separated by four interfaces. The three blue lines correspond to fluid–solid interfaces, while the gray line denotes the solid–solid interface. The arrows indicate longitudinal and shear waves propagating upward (−) and downward (+).

Following the mathematical notation of [15], the governing equations relating the wavefields to the resulting elastic responses (e.g., local stress and displacement u) are given for solids in Equation (1).

For fluids, under the assumption of an inviscid medium, the governing equations simplify due to the absence of shear modulus (Equation (2)), where P denotes the acoustic pressure. The components of Equations (1) and (2) are detailed in Appendix A.

Given the in-layer propagation described by Equations (1) and (2), modeling begins with the fluid–solid interfaces, which couple acoustic propagation across the system. At these interfaces, the boundary conditions require continuity of the vertical displacement component and normal stress , together with vanishing tangential stress (). Substituting these conditions into Equations (1) and (2), the interaction of the six partial-wavefields meeting at a fluid–solid interface can be expressed as

which, upon rearrangement, is written in complete matrix form as

where is obtained by removing the first row of , and is obtained by extending into a 3 × 2 matrix and filling the third row with zeros. Here, underlines indicate the bottom of a medium, while overlines represent the top surface.

Similarly, the interaction of the eight partial wavefields at the sediment–bedrock interface—the sole solid–solid interface in the system—can be written as

By combining the propagation relations across all four interfaces, the characteristic equation for the system is derived as

where is the amplitude vector of partial-wave fields, and the characteristic coefficient matrix is represented by .

Assuming a source-free system and infinite depth for the air and bedrock layers, no acoustic energy enters from outside. Thus,

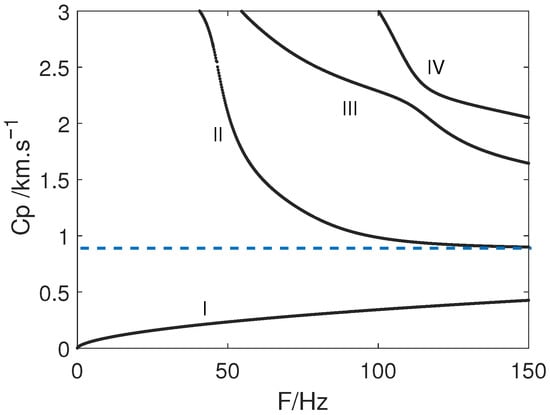

Accordingly, the corresponding columns of can be removed, reducing it to a square matrix . The dispersion relation of the model system is then obtained by solving () analytically using the local peak search scheme described in [19]. The dispersion relation computed over [0 Hz, 150 Hz] is shown in frequency-phase velocity (F-Cp) space in Figure 2, which highlights the dispersive and multimodal nature of the system. Among the four observed modes, Mode I corresponds to the QS wave originating from the ice-water interface, with a phase velocity that stabilizes toward the Rayleigh wave velocity [19]; Mode II corresponds to the SS wave, associated with the water–sediment interface, with a stable phase velocity approximately 0.9 times the sediment shear-wave velocity (the blue dashed line). Modes III and IV represent additional propagation modes resulting from the layered ICSW structure.

Figure 2.

The analytical dispersion curves of the model system. ‘I, II…’ represent the mode numbers.

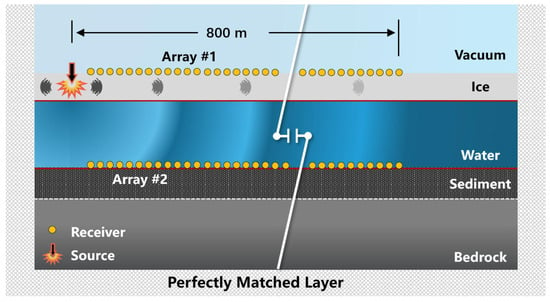

To validate the analytical model, the numerical simulation was performed using the spectral element method (SEM) implemented in open-source package Specfem2D (version 8.0.0) on an Ubuntu 16.04 system. Details of the SEM are provided in [26,27,28]. As shown in Figure 3, the geometry and material properties match the theoretical model, with the propagation system comprising five horizontal layers. The thicknesses of the ice, water, and sediment layers are 0.35, 7, and 5 m, respectively. Acoustic parameters are taken from previous studies [29,30,31] (Table 1), taking hard sediment as an example.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the SEM numerical simulation setup. The model consists of a multilayered waveguide (air–ice–water–sediment–bedrock) with geometric parameters matching the theoretical derivation. A Ricker wavelet source ( Hz) was applied at the ice surface. Two receiver arrays (Array and ) are indicated by yellow dots. The gray shaded regions represent PML.

Table 1.

The acoustic parameters of the ICSW acoustic propagation model.

As illustrated in Figure 3, the computational domain is surrounded by the Perfectly Matched Layers on the lateral and bottom to prevent inward propagation. A point source applied vertically at the ice surface () using a Ricker wavelet with a central frequency of 50 Hz. The resulting wavefield was recorded by two receiver arrays. Arrays #1 and #2 were aligned horizontally along the x-direction at the ice surface and the water bottom, respectively. Each consisted of 1600 receivers with 0.5 m spacing, starting 0.5 m from the source. To accurately capture the wave propagation, the domain was meshed using quadrilateral spectral elements, ensuring at least 5 points per minimum wavelength. The time step satisfies the Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy (CFL) stability condition.The time integration utilizes the Newmark scheme.

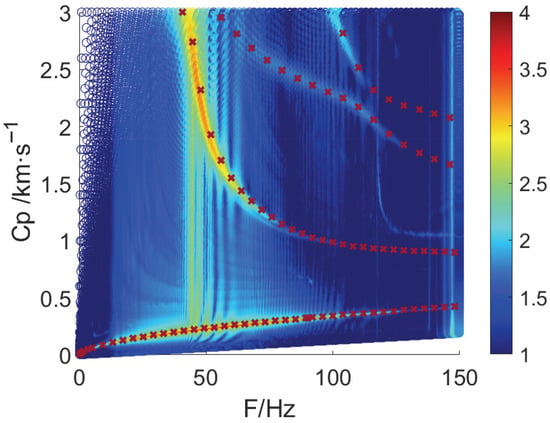

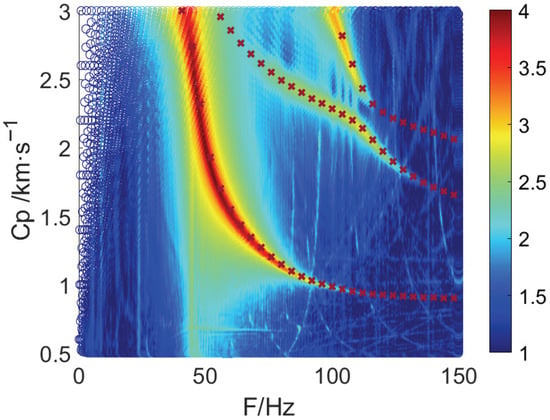

F-K analysis of the vertical signals recorded by Array #1 was performed via 2D Fourier transform and projected into F-Cp space (Figure 4). The QS and SS waves are the dominant modes energetically, both dispersive at low frequencies, with higher-order modes also present. The dispersion curves from the analytical model (red ×) are superimposed on the simulation results, showing excellent agreement across all four modes. It is worth noting that the distinct vertical energy strip observed at approximately 50 Hz is attributed to the spectral characteristics of the source excitation (50 Hz Ricker wavelet) and does not represent a dispersive mode of the waveguide.

Figure 4.

Comparison of dispersion curves, the analytical model (red ×) is superposed on the simulation results. The color bar indicates the energy value given by SEM.

3. Dispersive Structure Analyses

Having validated the analytical model, it is then used to analyze the dispersion characteristics of the 5-layer ICSW system. Given the broadness of the topic, this paper focuses on the influence of the structure of the system on the waveguide at low frequencies, more specifically, on how the depth of layers affects the dispersion curves of QS wave and SS wave. We defined two hypothetical scenarios: the case where corresponds to hard sediment, whereas the case where corresponds to soft sediment. The acoustic parameters are listed in Table 1.

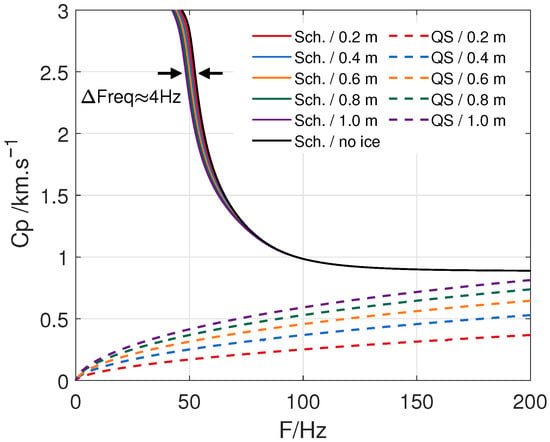

3.1. Ice Thickness

Taking hard sediment as an example, the effect of the presence and thickness of ice on the waveguide is first investigated. Dispersion curves for the QS and the SS waves are calculated for a range of ice thicknesses, with the depths of the water and sediment layers fixed at 6 m and 5 m, respectively. Since ice thickness in shallow water areas at high latitudes is generally less than 1 m, the ice thicknesses are varied between 0 m and 1 m. As shown in Figure 5, the QS wave (dashed lines) is highly sensitive to variations in ice thickness; its phase velocity increases significantly with thickness at any given frequency. In contrast, the SS wave (solid lines) is only slightly affected by ice thickness. When the ice thickness increases by a factor of 5, its dispersion curves exhibit only a minor downward shift along the frequency axis. For example, taking Cp = 2500 m/s as a reference point, the frequency corresponding to this velocity decreases from ∼52 Hz to ∼48 Hz. Once the frequency exceeds 80 Hz, all dispersion curves overlap almost perfectly.

Figure 5.

Dispersion curves of QS wave (solid lines) and SS wave (dashed lines) for various ice thicknesses (colors online).

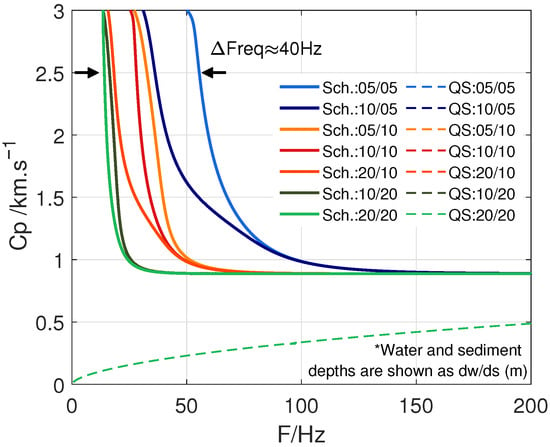

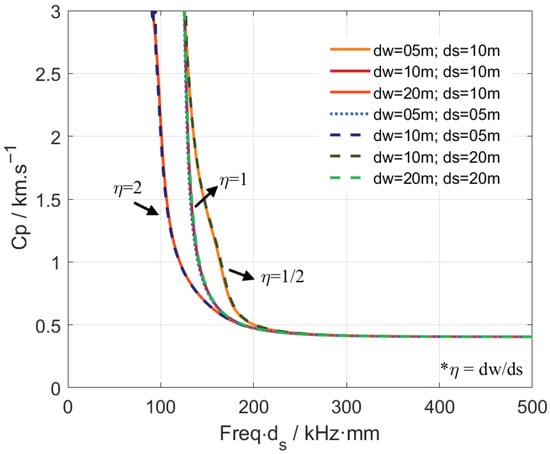

3.2. Water and Sediment Depth

Similarly, to study how water and sediment depths affect the dispersion characteristics, another set of dispersion curves is calculated with depths ranging from 5 m and 20 m, while the ice thickness is fixed at 0.35 m. As illustrated in Figure 6, the dispersion curves of the QS wave are represented by solid lines, while those of the SS wave are shown as dashed lines. The variations in color correspond to different water or sediment depths. The QS wave is completely unaffected by changes in water or sediment depth, with its dispersion curves perfectly overlapping. By contrast, the SS wave is highly sensitive, with dispersion curves strongly altered by changes in depth. For example, at Cp = 2500 m/s, the corresponding frequency change in the SS wave is less than 8% when the ice thickness increases by a range of [0 m, 1 m], as shown in Figure 5; and such a change exceeds 75% at most when the sediment depth changes by a factor of four (5 m to 20 m) in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Dispersion curves of QS wave (solid lines) and SS wave (dashed lines) for various depths of water and hard sediment layers (colors online). The * denotes a note.

In general, the dispersion curves of SS waves maintain a similar shape, and increasing either water or sediment depth shifts the dispersion curve downward; sediment depth has the greater influence. For instance, comparing the two dispersion curves with the same total depth of 15 m (purple and light orange lines), at Cp = 2500 m/s, a larger sediment depth corresponds to a lower frequency. The same trend is seen in the two curves with a total depth of 30 m (green and maroon lines in Figure 6). Since the SS wave dispersion curve resembles the letter ‘L’ in the F-Cp space, and the Cp converges with increasing frequency (Figure 6) regardless of water or sediment depth, the frequency at which Cp converges can be taken as a reference point for quantitative comparison. This convergent frequency () is defined as the frequency where the difference between Cp and its stabilized value (884.96 m/s) is sufficiently small, e.g., less than 10 m/s. The values of are extracted from Figure 6 and are listed in Table 1, demonstrating a clear linear proportionality between and sediment depth. However, when considering frequencies at which Cp reaches 2500 m/s (Table 2), this proportionality no longer holds, as Cp deviates from its convergent value. To systematically analyze the geometric effects of the waveguide structure, we introduce a dimensionless parameter , defined as the ratio of water to sediment depth. As shown in Figure 6, dispersion curves with the same exhibit similar topological shapes but are shifted along the frequency axis, indicating a geometric similarity law where the mode characteristics are preserved under proportional scaling.

Table 2.

The values of and for different water and sediment depths.

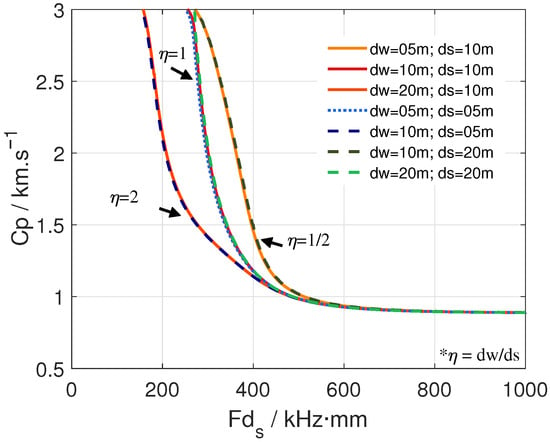

For a more intuitive comparison, the dispersion curves in Figure 6 are replotted in the space (Figure 7). As shown clearly, the dispersion curves collapse onto each other whenever water and sediment depths are proportionally scaled (i.e., with the same ratio ), regardless of their specific values. The 7 dispersion curves cluster into 3 groups corresponding to of 0.5, 1, and 2. Because of this near-exclusive dependence on , the remainder of this section focuses on the dispersion curves of the SS wave in the phase domain.

Figure 7.

Re-taped SS wave dispersion curves for of 0.5, 1, and 2 with hard sediment. The * denotes a note.

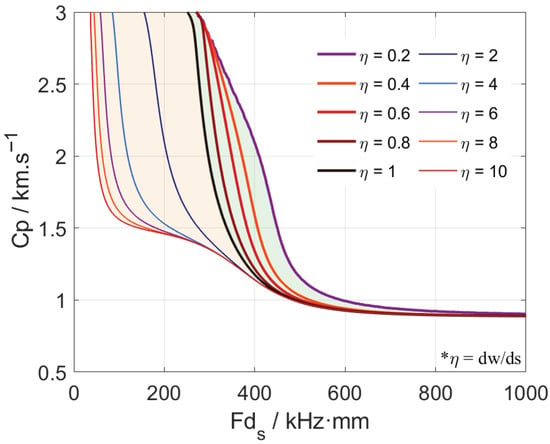

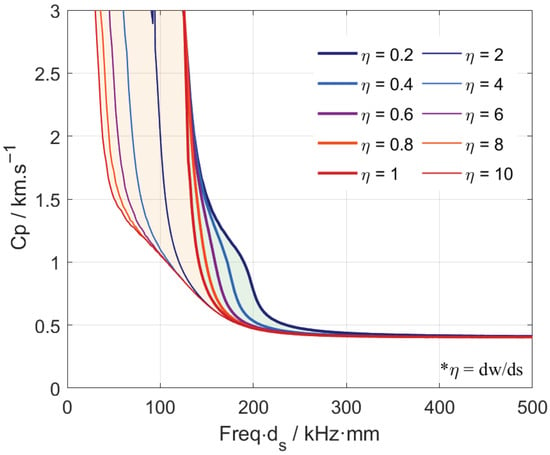

Dispersion curves for SS waves are calculated for more than 10 different values ranging from 0.2 to 10. As shown in Figure 8, two distinct patterns emerge. For , the dispersion curves converge at both the high-velocity end (around 2900 m/s) and the low-velocity end, though convergence is much slower at the low-velocity end. For , the dispersion curves diverge at high velocity ( m/s approximately), shifting leftward with increasing , but they converge quickly once the phase velocity falls below 1200 m/s. Nevertheless, regardless of how large becomes, the phase velocity ultimately converges with increasing , and stabilizes at approximately 900 m/s.

Figure 8.

SS wave dispersion curves for varying with hard sediment. The * denotes a note.

For the case of soft sediment layers, the same trend is observed. The dispersion curves with the same ratio of water depth to sediment depth () still exhibit similar shapes (Figure 9). However, as the sediment layer softens, the density and wave velocities decrease, and the frequency interval between the dispersion curves corresponding to the same ratio narrows significantly (e.g., from to ). As shown in Figure 10, when values ranging from 0.2 to 10, two distinct patterns emerge. For , the dispersion curves converge at around 2000 m/s and the low-velocity end, though convergence is much slower at the low-velocity end. For , in the same manner as for the case of hard sediment layers, the dispersion curves diverge at high velocity ( m/s approximately), shifting leftward with increasing , but they converge quickly once the phase velocity falls below 1200 m/s. Nevertheless, regardless of how large becomes, the phase velocity ultimately converges with increasing , and stabilizes at approximately 900 m/s.

Figure 9.

Re-taped SS wave dispersion curves for of 0.5, 1, and 2 with soft sediment. The * denotes a note.

Figure 10.

SS wave dispersion curves for varying with soft sediment. The * denotes a note.

4. Joint Inversion for Ice Thickness, Water and Sediment Depths

Based on the described dispersion features of the waveguide in the model system, a two-step inversion procedure is proposed for estimating the structural estimation of the 5-layer ICSW system, i.e., the depths of the ice, water, and sediment layers.

Step 1: Since ice thickness is the only parameter that significantly affects the dispersion curve of the QS wave, its value can be estimated through a simple single-variable inversion procedure. By defining a 1D discretized search grid for the ice thickness, and assuming arbitrary water and sediment depths, a series of corresponding dispersion curves of the QS wave () are modeled and compared to the simulated one. The root mean square error (RMSE) of the phase velocities at the same frequencies is used as the fitness metric, and the ice thickness that yields the best-fitting curve is retained as the estimated result.

Step 2: With the ice thickness estimated, a second parameter space is constructed in a similar manner for the inversion of water and sediment depths. This 2D search grid is represented by a pair of values (, ). Because of the additional dimension and wider ranges, the number of mesh nodes required to cover the space becomes considerably larger. The aforementioned feature of the SS wave, i.e., its dispersion curve depends on rather than on specific depths, enables improved inversion efficiency by avoiding cumbersome forward-modeling calculations. Specifically, the space is initially discretized with a uniform mesh, whose nodes are then slightly adjusted from their initial positions so that the related values fit a preset numerical precision (e.g., 1%). The dispersion curve for at each node is calculated in the space, and then reprojected into the space using its specific value. In this way, the total number of dispersion curves required for inversion can be significantly reduced, especially at high meshing resolution. The modeled dispersion curves are then compared to the simulated ones in the same manner, and the parameter set (, ) with the best-fitting quality is retained as the estimated result.

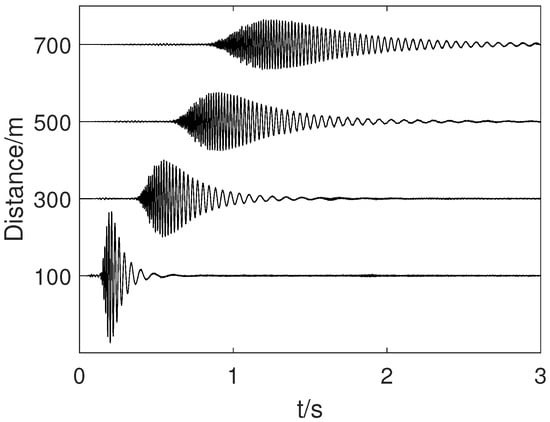

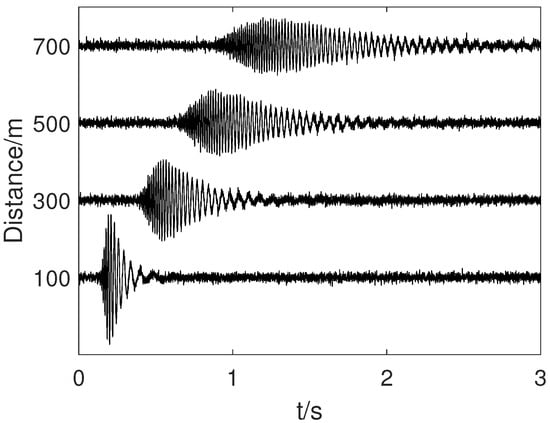

This two-step inversion procedure is applied to the numerical simulation described in Section 2. To enhance the authenticity of the signals, random noise was added to the vertical signals recorded by Array #1, with the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) maintained at 10 dB. Figure 11 and Figure 12 shows the signals before and after noise addition, respectively.

Figure 11.

Received signals at distances of 100 m, 300 m, 500 m, and 700 m from the sound source.

Figure 12.

Received signals with random noise at distances of 100 m, 300 m, 500 m, and 700 m from the sound source.

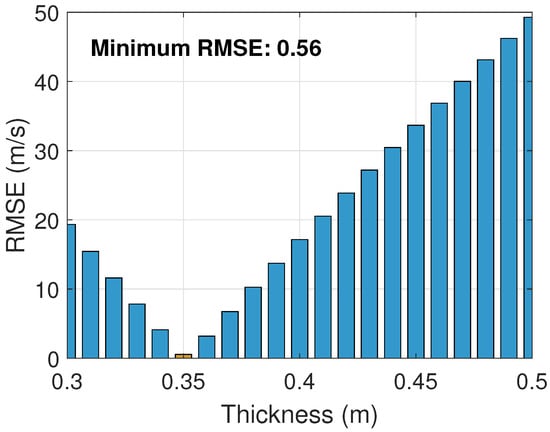

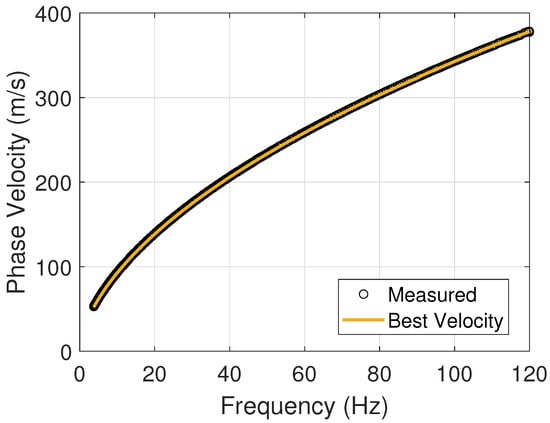

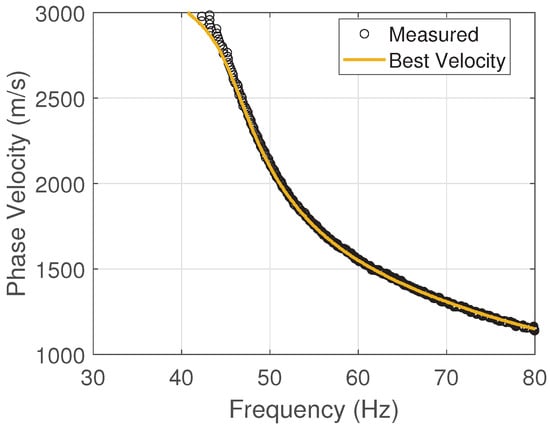

Following the procedure, the ice thickness is estimated first. Since the QS wave has no cutoff frequency and is dispersive across the frequency band, its dispersion curve was modeled over the range of [4 Hz, 120 Hz] with a resolution of 0.01 Hz. Based on prior knowledge, the search grid for ice thickness was set between 0.3 m and 0.5 m with a resolution of 0.01 m. Once the QS dispersion curves for all search nodes are obtained, they are interpolated so that the modeled phase velocities are available at the same frequencies as the simulated data. The RMSE between the simulated and modeled Cp was calculated and is shown as blue bars in Figure 13, with the minimum RMSE (yellow bar) of 0.56 m/s corresponding to an estimated ice thickness of 0.35 m. The estimation of ice thickness is consistent with the setting of simulation, and the best-fitting QS wave dispersion curve is illustrated alongside the simulated data (black circles) in Figure 14.

Figure 13.

The RMSE between the simulated and modeled of the search grid for the ice thickness. The yellow bar is the minimum RMSE.

Figure 14.

The best-fitting dispersion curve of the QS wave alongside the simulated data.

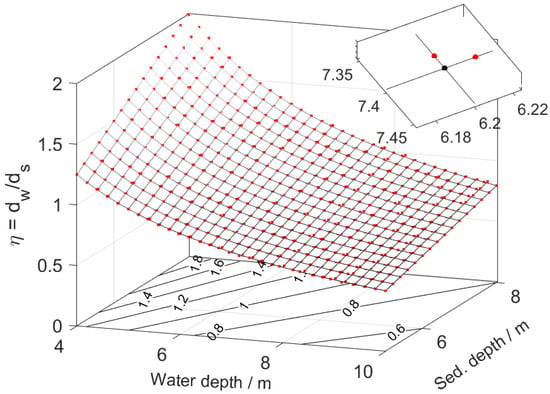

For the joint inversion of water and sediment depths, a 2D search grid for () was constructed with a uniform resolution of 0.2 m. The search ranges for water and sediment depths were [5 m, 8 m] and [4 m, 10 m], respectively, resulting in 496 mesh nodes in total. The of this grid ranges between 0.5 and 2, which yields 151 unique values once the numerical precision is limited to 1%. The exact at each node was then rounded to this precision. If the rounding changes the value of a node, the original node (black dot) is then replaced by two nearby nodes (red dots) whose matches the rounded value. For example, a node with of 0.837838 is replaced by two nearby nodes with a rounded of 0.84 (inset of Figure 15). In this way, the search grid is re-meshed with more nodes (increasing from 496 to 920 in Figure 15), while the number of unique values is greatly reduced (e.g., dropping from 453 to 126). Consequently, the number of SS wave dispersion curves required for the joint inversion is substantially reduced.

Figure 15.

The meshing scheme of the space.

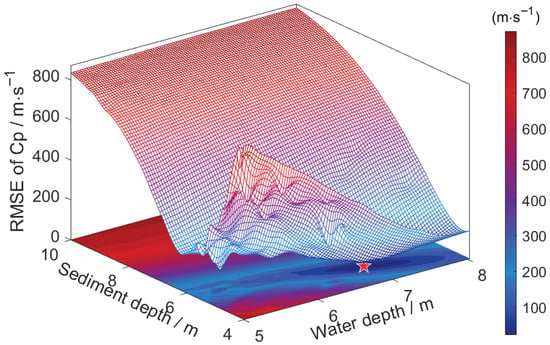

Based on the 126 values, the SS wave dispersion curves are modeled within the space with an ice thickness of 0.35 m (estimated result) and a sediment depth of 10 m (maximum limit of the search range). They are then assigned to each of the 920 nodes, re-plotted into the space using their specific values, and finally re-sampled and compared with the simulated data to calculate the RMSE (Figure 16). The minimum RMSE (red pentagram) corresponds to an estimated water depth of 7 m and a sediment depth of 5 m.

Figure 16.

The joint inversion result with the fitting RMSE of . The pentagram is the minimum RMSE.

As shown in Figure 16, sediment depth has the greatest influence on the fitting procedure. This agrees with the observations in Section 3, where differences in sediment depth were shown to cause a mismatch of the dispersion curve along the frequency domain. This mismatch results in a significant RMSE at low frequencies, where the SS wave phase velocity drops abruptly. Furthermore, the best-fitting SS wave dispersion curve is illustrated alongside the simulated data in Figure 17, and the estimated water and sediment depths are consistent with simulation settings.

Figure 17.

The best-fit dispersion curves of the estimated water and sediment depths.

5. Discussion: Vertical Distribution of Modal Energy

As demonstrated through numerical simulation, the elastic wavefield at low frequencies observed on the ice surface over shallow water mainly consists of contributions from the QS wave and the SS wave. In addition to their dispersive characteristics, their energy distribution over the system depth is also of interest for explaining the observations. Similarly to the result shown in Figure 4, the velocity spectra of the signal recorded at the bottom of the water (array #2) in the same numerical simulation (Figure 3) are illustrated in Figure 18. The SS wave shows the highest energy level, while the other modes (modes III and IV in Figure 2) are more visible. Compared with the modeled dispersion curve, which is identical to that shown in Figure 2, the dispersion characteristics remain the same as those observed on the ice. Nevertheless, the QS wave is absent here.

Figure 18.

The spectra observed at the water–sediment interface (array #2) in the numerical simulation. Color bar indicates the energy value given by SEM, and the model (red ×) dispersion curve are superposed for comparison.

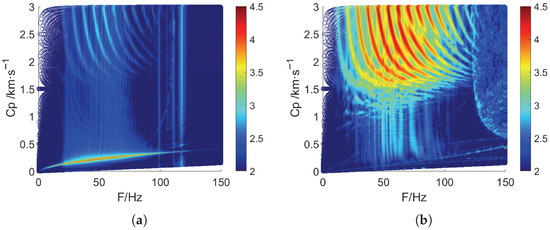

To better understand the presence or absence of the SS wave in experimental observations, a second simulation is conducted using a similar model, but with the water depth increased to 100 m. Figure 19 shows the spectra of the wavefield observed at the ice surface and the water bottom. The highly dispersive QS wave remains the dominant mode at the ice surface but is absent at the bottom of the water, whereas the SS wave cannot be clearly identified at either interface. Meanwhile, due to the increased water depth, the waveguide effect of the water layer becomes prominent within this frequency range; it is dominant at the water bottom and only marginally observable at the ice surface. Considering the realities of experimental conditions (e.g., velocity profile, ice condition, etc.), in situ observation of water-related guided waves is challenging, which is consistent with previously reported observations [32].

Figure 19.

The spectra observed at ice surface (a) and water–sediment interface (b) in the numerical simulation. Color bar indicates the energy value given by SEM.

6. Conclusions

This study investigates the acoustic wavefield in ice-covered shallow water with a particular focus on two Scholte-like waves, i.e., the quasi-Scholte (QS) and Scholte–Stoneley (SS) waves, stemming from the fluid–solid interfaces, and their potential applications. A five-layer model is proposed to describe acoustic propagation and analytically extract the dispersion features of QS and SS waves in such an ICSW system. By incorporating water and sediment layers of finite depth, the proposed model offers a more comprehensive and realistic description of acoustic propagation compared with previously reported ones.

The dispersion features of QS and SS waves derived from the analytical model were first validated by comparison with numerical simulation results obtained using SEM-2D. They were then analyzed in the cases of soft () and hard () sediment in terms of their dependence on the structure of the layered system, i.e., the depths of the ice, water, and sediment layers. The dispersion feature of the QS wave exhibits a near-exclusive dependence on ice thickness; it is highly sensitive to ice thickness while remaining largely unaffected by variations in water or sediment depth. In contrast, the dispersion feature of the SS wave does not directly depend on the depth of any single layer. Instead, it is governed by the ratio of water depth to sediment depth () in the space, regardless of their specific values, and is insensitive to ice thickness. As an example of potential application, a two-step inversion procedure based on dispersion characteristics is proposed and applied to numerical simulation. The estimated ice thickness (0.35 m), water depth (7 m), and sediment depth (5 m) show excellent agreement with simulation settings, which further validates the proposed model.

To discuss the conditional observability of the SS wave at the ice surface, the spatial distributions of the QS and SS waves are analyzed using numerical simulations. Results under shallow-water conditions indicate that both waves are observable at the ice surface. However, the QS wave is absent at water bottom, while the SS wave shows the highest energy level, and the other high-order modes are more visible. When the water depth is increased to 100 m, a large number of water-related modes emerge within this frequency range and dominate the acoustic energy in the water, while the SS wave is no longer visible at the ice surface. These preliminary results are consistent with experimental observations and partially explain the absence of the SS wave in experimental observations over the Arctic Ocean.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.; methodology, D.M.; software, D.M. and Y.Z.; validation, D.M.; formal analysis, D.M.; investigation, D.M. and X.L.; resources, D.M. and Y.Z.; data curation, D.M. and R.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.; writing—review and editing, D.M., Y.Z. and C.S.; visualization, D.M. and Y.Z.; supervision, C.S.; project administration, C.S.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52171334), the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (Grant No. 62125104), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province, China (Grant No. 623CXTD394).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xiaoying Liu was employed by the company China State Shipbuilding Corporation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A

References

- Fossheim, M.; Primicerio, R.; Johannesen, E.; Ingvaldsen, R.B.; Aschan, M.M.; Dolgov, A.V. Recent warming leads to a rapid borealization of fish communities in the Arctic. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylmer, J.R.; Ferreira, D.; Feltham, D.L. Impact of ocean heat transport on sea ice captured by a simple energy balance model. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, B. Arctic sea ice, ocean, and climate evolution. Science 2023, 381, 946–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnier, F.; Fleury, S.; Garric, G.; Bouffard, J.; Tsamados, M.; Laforge, A.; Bocquet, M.; Fredensborg Hansen, R.M.; Remy, F. Advances in altimetric snow depth estimates using bi-frequency SARAL and CryoSat-2 Ka-Ku measurements. Cryosphere 2021, 15, 5483–5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, L.; Seydoux, L.; Weiss, J.; Campillo, M. Analysis of microseismicity in sea ice with deep learning and Bayesian inference: Application to high-resolution thickness monitoring. Cryosphere 2023, 17, 1327–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Pang, X.; Xu, S.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Q.; Shing, Z. Review of technology and application research on polar sea ice thickness detection. Chin. J. Polar Res. 2016, 28, 431–441. [Google Scholar]

- Hunkins, K. Seismic studies of sea ice. J. Geophys. Res. 1960, 65, 3459–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.C.; Giellis, G.R. Experimental characterization of elastic waves in a floating ice sheet. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1994, 96, 2993–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosso, S.E.; Heard, G.J.; Vinnins, M. Source bearing estimation in the Arctic Ocean using ice-mounted geophones. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2002, 112, 2721–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, L.; Boué, P.; Serripierri, A.; Weiss, J.; Hollis, D.; Pondaven, I.; Vial, B.; Garambois, S.; Larose, E.; Helmstetter, A.; et al. Sea Ice Thickness and Elastic Properties From the Analysis of Multimodal Guided Wave Propagation Measured With a Passive Seismic Array. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2020, 125, e2019JC015709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, L.; Weiss, J.; Marsan, D. Accurate estimations of sea-ice thickness and elastic properties from seismic noise recorded with a minimal number of geophones: From thin landfast ice to thick pack ice. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2020, 125, e2020JC016492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press, F.; Ewing, M. Propagation of elastic waves in a floating ice. Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1951, 32, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiades, E.; Lowe, M.J.S.; Craster, R.V. Leaky wave characterisation using spectral methods. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2022, 152, 1487–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chotiros, N.P.; Gaye, B.; Oliver, S.; Timothy, C.; Best, A.I. Simulation of acoustic reflection and backscatter from arctic sea-ice. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2023, 153, 3258–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.Y.; Zhang, Y.X.; Sun, C.; Gao, J.H.; Jin, C.Y.; Yin, J.W. Modeling of acoustic waveguides in floating ice sheets with vertical temperature profiles. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2025, 157, 3310–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yew, C.H.; Weng, X. A study of reflection and refraction of waves at the interface of water and porous sea ice. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1987, 82, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wong, H. Analytic solutions to reflection-transmission problem of interface in anisotropic ice sheet. Int. J. Antenn. Propag. 2020, 2020, 9869873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, L.; Lachaud, C.; Thery, R.; Predoi, M.V.; Marsan, D.; Larose, E.; Weiss, J.; Montagnat, M. Monitoring ice thickness and elastic properties from the measurement of leaky guided waves: A laboratory experiment. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2017, 142, 2873–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Ma, D.; Zhang, Y.; Sheng, X. Review on modeling polar sea-ice acoustics waveguide. Acta Phys. Sin. 2022, 71, 084301-1–084301-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, T.A.; Ruud, B.O.; Hope, G. Seismic on floating ice on shallow water: Observations and modeling of guided wave modes. Geophysics 2019, 84, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, T.A.; Ruud, B.O. Characterization of seabed properties from Scholte waves acquired on floating ice on shallow water. Near Surf. Geophys. 2020, 18, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presnov, D.; Zhostkov, R.; Gusev, V.; Shurup, A. Dispersion dependences of elastic waves in an ice-covered shallow sea. Acoust. Phys. 2014, 60, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, J.; Carter, J.A.; Sutton, G.H.; Barstow, N. Shallow water sediments properties derived from high-frequency shear and interface waves. J. Geophys. Res. 1992, 97, 4739–4762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobisevich, A.; Presnov, D.; Shurup, A. Arctic-Type Seismoacoustic Waveguide: Theoretical Foundations and Experimental Results. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.L.; Shan, Z.D.; Xie, Z.N.; Lu, C.T. Dispersion and attenuation characteristics of fluid-solid interface waves in submarine slope regions. Ocean Eng. 2025, 331, 121358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.N.; Komatitsch, D.; Martin, R.; Matzen, R. Improved forward wave propagation and adjoint-based sensitivity kernel calculations using a numerically stable finite-element PML. Geophys. J. Int. 2014, 198, 1714–1747. [Google Scholar]

- Komatitsch, D.; Barnes, C.; Tromp, J. Wave propagation near a fluid-solid interface: A spectral element approach. Geophysic 2000, 65, 623–631. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Z.; Matzen, R.; Cristini, P.; Komatitsch, D.; Martin, R. A perfectly matched layer for fluid-solid problems: Application to ocean-acoustics simulations with solid ocean bottoms. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2016, 140, 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.H.; Zhang, Y.X.; Ma, D.Y.; Xie, Z.N.; Wang, A.L.; Zhang, H.N. In-situ characterization of wave velocity in ice cover with seismic observation on guided wave. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2025, 231, 104392. [Google Scholar]

- Castagna, J.P.; Batzle, M.L.; Eastwood, R.L. Relationships between compressional-wave and shear-wave velocities in clastic silicate rocks. Geophysics 1985, 50, 571–581. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Piao, S.; Gong, L.; Zheng, G.; Iqbal, K.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X. Scholte Wave Dispersion Modeling and Subsequent Application in Seabed Shear-Wave Velocity Profile Inversion. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serripierri, A.; Moreau, A.; Pierre Boue, P.; Weiss, J.; Roux, P. Recovering and monitoring the thickness, density and elastic properties of sea ice from seismic noise recorded in Svalbard. Cryosphere 2022, 16, 2527–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.