Abstract

Underwater acoustic energy transmission (UAET) is critical for sustaining long-term operations of underwater platforms, but its efficiency is constrained by the limited aperture of underwater receivers—requiring acoustic energy to be concentrated within a pre-defined target angular domain. Existing array-weighting methods face inherent limitations: traditional window-based techniques optimize mainlobe–sidelobe trade-offs rather than target-specific energy concentration, while intelligent algorithms suffer from high computational cost, quasi-optimality, and poor reproducibility. To address these gaps, this study proposes an array beam energy aggregation optimization method based on Rayleigh quotient eigenvalues for UAET. First, a rigorous mathematical model of the acoustic energy concentration problem was established: by defining a target-domain energy operator matrix with a Toeplitz–sinc structure (Hermitian positive definite), the energy-focusing problem was transformed into a tractable linear algebra problem. Second, the optimization objective of maximizing target-domain energy was formulated as a generalized Rayleigh quotient maximization problem, where the optimal amplitude weights correspond to the eigenvector of the maximum eigenvalue of —solved via Cholesky whitening and eigenvalue decomposition to ensure theoretical optimality and low computational complexity. Comprehensive validations were conducted via simulations and underwater physical experiments. Simulations on 1D uniform linear arrays and 2D 4-layer circular ring arrays showed that the proposed method outperformed traditional weighting methods and PSO in target angular energy concentration: for the 16-element linear array, its energy radiation efficiency in the 30° domain was 14% higher than classical methods (Blackman weighting). Underwater physical tests further confirmed its superiority: for the 4-layer circular ring array at 1 m, the acoustic energy efficiency in the 30° target domain reached 21.5% higher than Blackman weighting. Additionally, the method exhibited strong adaptivity (dynamic weight adjustment with target angular width) and scalability (performance improvement with array size), meeting UAET’s real-time and reliability requirements. This work provides a theoretically optimal and engineering-feasible solution for directional acoustic energy transfer in underwater environments, offering valuable insights for UAET system design.

1. Introduction

Underwater acoustic energy transmission has become a key power supply technology for sustaining the long-term operation of underwater platforms such as autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), underwater sensor networks (USNs), and underwater monitoring systems [1,2,3,4,5]. Given that traditional cable-based power supply methods face significant challenges in underwater environments [6]—such as implementation difficulties and poor flexibility [7,8]—while frequent battery replacement involves complex operations [9], long cycles, and high maintenance costs [10], it is therefore imperative to explore non-contact energy transfer technologies [11]. With the growing demand for long-distance applications in underwater communication and acoustic energy transmission, the efficient concentration and stable transmission of acoustic energy have become critical technical challenges that urgently need to be addressed in this field [5,12,13]. Compared with traditional isotropic acoustic propagation, directionally focused acoustic beams concentrate energy within a narrow angular domain; this not only improves signal resolution but also enables effective spatial energy aggregation [14], thereby significantly enhancing transmission efficiency. Whether for directional communication in underwater sensor networks or long-range power supply to deep-sea equipment, developing efficient acoustic beam energy aggregation and transmission technology is of great practical significance [15]. A core challenge in UAET systems lies in the physical size constraint of receiving devices: due to the limited aperture of underwater energy receivers, the transmitted acoustic energy must be efficiently concentrated within a pre-defined target angular region to maximize the energy harvest efficiency and minimize energy loss to non-target areas [16]. This demand has spurred extensive research on array beamforming optimization, as array amplitude-weighting methods offer a flexible means to manipulate the beam pattern and achieve targeted energy aggregation [17,18,19,20].

In the context of array beam energy focusing for UAET, two main categories of weighting strategies have been widely explored. The first category encompasses traditional window function-based weighting techniques, such as Hanning, Hamming, and Blackman windows. These methods are favored in engineering applications due to their simplicity in implementation—they adjust the amplitude weights of array elements via pre-defined window profiles to balance the mainlobe width and sidelobe level [21]. For instance, a Hamming window can effectively suppress sidelobes at the cost of a slightly widened mainlobe [22], while a Dolph–Chebyshev window achieves the narrowest mainlobe for a given sidelobe level [23]. However, window functions are typically designed from a global perspective, with their core design criteria focused on enhancing the mainlobe peak gain or limiting sidelobe leakage below a specific threshold rather than maximizing the total energy in the target receiving region [24]. This misalignment with UAET’s core demand becomes apparent in practical scenarios: UAET systems prioritize energy aggregation within the target receiving domain due to the physical size limitation of receivers, yet traditional window functions adopt fixed weighting profiles that cannot be dynamically adjusted with changes in the target receiving angle. As a result, energy distribution of near and far sidelobes is constrained by the window function’s form and parameters, making it difficult to further suppress energy leakage; in some angular domains, this may even lead to mainlobe response attenuation or sidelobe elevation, directly reducing energy transfer efficiency in the target region and increasing the probability of energy waste [25].

The second category of approaches relies on intelligent optimization algorithms, including particle swarm optimization (PSO), genetic algorithms (GAs), and differential evolution (DE) [26,27,28]. These evolutionary algorithms are designed to search for optimal amplitude weights by treating the beamforming problem as a multi-objective optimization task. Compared to window functions, they offer greater flexibility in handling complex constraints and can potentially achieve better beam pattern performance in some cases [29]. Nevertheless, their practical applicability in UAET is hindered by several critical drawbacks. First, their computational cost is high: evolutionary algorithms require iterative search processes that involve frequent evaluation of candidate solutions, making them incompatible with the real-time adaptive demands of UAET—especially when the target angular domain changes and rapid weight updates are needed [30]. Second, they suffer from quasi-optimality and poor physical interpretability: the optimization process lacks analytical transparency, and weight solutions often exhibit “black-box” characteristics, with no inherent theoretical guarantee of achieving optimal energy aggregation for a given receiving angular range; instead, only quasi-optimal weights can typically be obtained [31]. Third, convergence is uncertain: these algorithms are sensitive to initial parameters and tend to fall into local optima in high-dimensional parameter spaces [32], leading to unstable beam performance that undermines the reliability of energy transfer.

To synthesize the above analysis, existing array-weighting methods for UAET are inherently constrained by limitations across three critical dimensions: energy transfer efficiency within the target angular region, weight adaptability to dynamic angular demands, and analytical solvability of the optimization process. Notably, this leaves a critical research gap in UAET array beamforming: there remains a lack of a robust array-weighting optimization method capable of simultaneously achieving theoretical optimality (i.e., ensuring maximum energy concentration within the target region), physical implementation consistency (featuring an explicit analytical form to facilitate straightforward hardware integration), and real-time adaptability (supporting rapid weight adjustment as the target angular region changes).

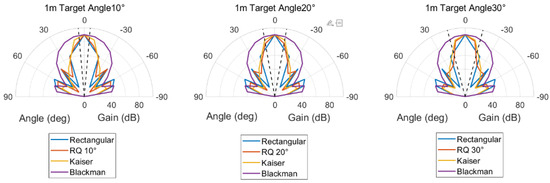

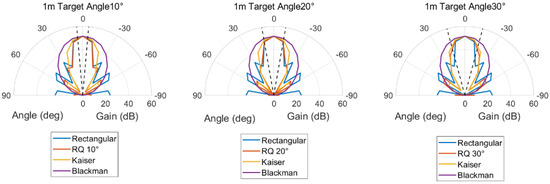

To address this gap, this paper proposes a UAET system-based array beam energy aggregation optimization method using Rayleigh quotient eigenvalues for UAET applications, with the core objective of developing an optimization framework that directly targets energy maximization in the pre-defined angular region while overcoming the limitations of existing methods. The key contributions of this study are as follows: First, we establish a rigorous mathematical model for the array acoustic energy aggregation problem, and by defining an energy operator that quantifies the energy distribution within the target angular region, we transform the original energy-focusing optimization problem into a tractable linear algebra problem—this transformation lays the foundation for deriving an analytical solution. Second, we formulate the energy maximization objective as a generalized Rayleigh quotient maximization problem, and leveraging the properties of the Rayleigh quotient and eigenvalue decomposition, we prove that the optimal array amplitude weights correspond to the eigenvector associated with the maximum eigenvalue of the constructed energy operator, an analytical solution that ensures both theoretical optimality and low computational complexity for real-time adaptation. Third, we validate the proposed method through comprehensive simulations and underwater physical experiments. Results confirm the method’s superiority: simulations on linear arrays and circular ring arrays show it outperforms traditional weighting methods and PSO in target angular energy concentration. Underwater tests reveal the highest target energy proportion—for the 4-layer circular ring array at 1 m, its 30° domain efficiency is 2.89% higher than uniform weighting, 3.36% higher than Kaiser weighting, and 21.5% higher than Blackman weighting—along with stable 0° mainlobe pointing, effective sidelobe suppression, and low computational complexity that meets UAET’s real-time needs, thus demonstrating strong universality, theoretical optimality, and engineering feasibility for underwater directional acoustic energy transmission.

2. Methods

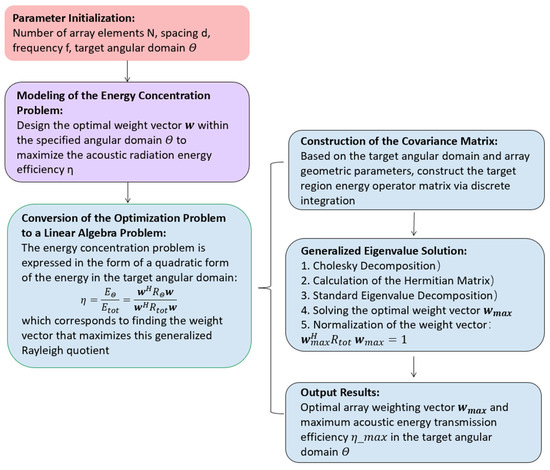

This chapter details the theoretical method and implementation steps of the proposed UAET system-based array beam energy aggregation optimization method using Rayleigh quotient eigenvalues, which is designed to maximize the acoustic energy concentration within a pre-defined target angular region for underwater acoustic energy transmission systems. First, a mathematical framework was established to address acoustic energy focusing within the target angular domain of the array. Key parameters were defined, including array geometry, target angular sector, and acoustic energy metrics, to quantify the spatial distribution characteristics of acoustic energy. Subsequently, the optimization objective of maximizing target angular energy is transformed into a generalized Rayleigh quotient maximization problem, and the eigenstructure of the core matrices’ target-domain energy operator matrix is analyzed to ensure theoretical optimality. Finally, a solution strategy based on eigenvalue decomposition that incorporates Cholesky whitening is presented to derive the optimal array amplitude weights, with clear algorithm steps for engineering implementation. The framework of our proposed Rayleigh quotient eigenvalue-based array beam energy aggregation optimization method is illustrated in Figure 1, and the following sections elaborate on each component of this framework.

Figure 1.

The framework of the Rayleigh quotient eigenvalue-based array beam energy aggregation optimization method.

2.1. Mathematical Modeling of Acoustic Energy Concentration Problem

To formalize the array acoustic energy concentration problem, this section first defines the geometric and signal parameters of the array, then quantifies the acoustic energy within the target angular domain and the total radiated energy, and finally establishes the acoustic energy radiation efficiency as the core optimization index.

2.1.1. Array Geometry and Signal Parameters

Consider a uniform linear array (ULA) consisting of N elements with an inter-element spacing d. In the array coordinate system, the position vector of the n-th element is defined as follows:

This symmetric position arrangement ensures that the array’s beam pattern is centered on the main axis, avoiding additional phase offsets caused by asymmetric geometry. Let denote the amplitude weight of the n-th element; the amplitude weight vector of the entire array is expressed as a column vector:

The weight vector is the key variable to be optimized, as it directly manipulates the array’s beam pattern and energy distribution [33]. For an acoustic wave with wavelength , the wave number is [34]. Let the propagation distance between the observation point (or receiver) and the array reference point be r, and let the seawater absorption coefficient be . Seawater absorption depends on temperature, salinity, acidity (pH), pressure, and frequency; can be calculated using the commonly used Francois–Garrison empirical model [35]. The steering vector (direction vector) , which describes the phase difference in acoustic signals arriving at each element from the angular direction , is given by the following:

Here, 1/r represents spherical spreading (the sound-pressure amplitude approximately decays with distance as 1/r), whereas represents amplitude attenuation due to medium absorption. represents the azimuth angle relative to the array’s main axis. The beam function of the linear array, which characterizes the distribution of the complex acoustic pressure amplitude with the angle, is derived as the inner product of the weight vector and the steering vector:

Here, the superscript H denotes the Hermitian transpose (conjugate transpose), ensuring that correctly represents the complex acoustic pressure for energy calculation.

2.1.2. Definition of Target Angular Domain

In UAET applications, the receiver is typically confined to a specific angular range rather than a single direction. Let be the central angle of the target region (the main direction of the array beam); the target angular domain is defined as a symmetric interval centered at with a total width :

The width is a critical parameter that reflects the size of the receiver’s effective area: if is larger than the 3 dB width of the array’s mainlobe, most of the mainlobe energy is included in the target domain, and the energy efficiency is primarily affected by sidelobe leakage; if is smaller than the mainlobe width, part of the mainlobe energy “leaks” outside the target domain, and the efficiency depends on both sidelobe suppression and mainlobe narrowing.

2.1.3. Acoustic Energy and Radiation Efficiency Calculation

Acoustic power (or energy density) is proportional to the squared magnitude of the acoustic pressure [2]. Thus, the total acoustic energy radiated by the array within the target angular domain is calculated by integrating over :

Similarly, the total acoustic energy radiated by the array over the entire angular space (denoted as ) is as follows:

The integration range in Equation (7) is restricted to because underwater acoustic energy transfer typically focuses on the forward half-space (avoiding energy loss to the seabed or air). The acoustic energy radiation efficiency , which quantifies the proportion of energy concentrated in the target domain, is defined as the ratio of to :

The core goal of the proposed method is to design the optimal weight vector that maximizes under the constraint of fixed total radiated energy. Physically, this corresponds to concentrating the maximum possible acoustic energy into the target angular domain while minimizing energy leakage to non-target areas (e.g., sidelobes), thereby improving the energy harvest efficiency of the underwater receiver. Notably, substituting Equation (4) into Equations (6) and (7) reveals that both and can be expressed as quadratic forms of the weight vector —a transformation that lays the foundation for subsequent linear algebra-based optimization.

Specifically, and , where (target-domain energy operator matrix) and (total energy operator matrix). Both matrices are Hermitian positive definite: exhibits a Toeplitz–sinc structure (due to the uniform linear array geometry) where elements only depend on the index difference , ensuring numerical stability for subsequent eigenvalue decomposition.

2.2. Frequency Optimization for Maximum Received Power

Building on the mathematical model of acoustic energy concentration established in Section 2.1, this section transforms the energy maximization objective into a generalized Rayleigh quotient optimization problem and derives the optimal array amplitude weights via eigenvalue decomposition. The core logic lies in leveraging the algebraic properties of Hermitian matrices (e.g., positive definiteness, orthogonal eigenvectors) to ensure theoretical optimality and numerical stability of the solution.

2.2.1. Generalized Rayleigh Quotient Formulation of Energy Efficiency

From Section 2.1, we know the acoustic energy radiation efficiency is defined as the ratio of the target angular domain energy to the total radiated energy . Substituting the quadratic form expressions of and into the efficiency formula, can be rewritten as a generalized Rayleigh quotient of the weight vector ; this expression is presented in Equation (9):

In this equation, the numerator quantifies the energy concentrated in the target angular domain (regulated by the target-domain energy operator matrix ), while the denominator represents the total energy radiated by the array (regulated by the total energy operator matrix ). Maximizing thus directly corresponds to the core goal of our method: optimizing the weight vector to maximize the proportion of energy in the target domain.

2.2.2. Formalization of the Optimization Problem

A direct maximization of the generalized Rayleigh quotient in Equation (9) would lead to trivial solutions [36]. To avoid this, we introduce a normalization constraint that fixes the total radiated energy to a constant (physically equivalent to limiting the total transmission power of the array). The constrained optimization problem is presented in Equation (10):

This constraint ensures the uniqueness of the optimal solution: by fixing the total energy, the optimization is reduced to “how to allocate this fixed energy to maximize the proportion in the target domain.” From the perspective of linear algebra, this constrained maximization problem is mathematically equivalent to solving a generalized eigenvalue problem, as elaborated in the following section.

2.2.3. Eigenstructure Analysis of Key Matrices

The solvability of the optimization problem in Equation (10) depends on the structural properties of and . For a uniform linear array (ULA), exhibits a special Toeplitz–sinc structure, which is derived from the symmetry of the array geometry and the integral form of [37]. Specifically, the -th element of (representing the coupling strength between the i-th and j-th elements within the target domain ) is obtained by expanding the integral definition of ; this element expression is presented in Equation (11):

where d is the inter-element spacing and is the wave number. Since the target domain is symmetric around , the integral in Equation (11) can be simplified using trigonometric identities. After simplification, the -th element of is expressed as a sinc function, presented in Equation (12):

This Toeplitz–sinc structure implies two critical properties of : the first is Toeplitz symmetry, meaning that the -th element of depends only on the index difference of the array elements, rather than their respective absolute indices or ; this symmetry enables to satisfy the definition of a Hermitian matrix, thereby ensuring that all its eigenvalues are real numbers and that the eigenvectors corresponding to different eigenvalues are mutually orthogonal [38]. The second property is positive definiteness: similar to the total energy operator matrix , is a positive definite matrix. This is because the physical quantity represented by its quadratic form is the acoustic energy within the target angular domain, which is inherently non-negative, and the value of this quadratic form is zero only when the weight vector is a zero vector [39].

Notably, the eigenvectors of are consistent with the Discrete Prolate Spheroidal Sequences (DPSS). According to DPSS theory [40], the eigenvector corresponding to the maximum eigenvalue of is the sequence that maximizes the energy concentration within the target angular domain —this provides a theoretical basis for our method to derive the optimal weight vector via eigenvalue decomposition [41].

2.2.4. Transformation to Generalized Eigenvalue Problem

According to the Rayleigh quotient theory, the maximum value of the generalized Rayleigh quotient in Equation (9) is equal to the maximum generalized eigenvalue of the matrix pair (, ), and the corresponding optimal weight vector is the eigenvector associated with this maximum eigenvalue [36]. This relationship is formalized as a generalized eigenvalue equation, presented in Equation (13):

In Equation (13), denotes the generalized eigenvalue, and denotes the corresponding eigenvector. For the matrix pair (, ) (both Hermitian positive definite), all generalized eigenvalues are positive real numbers. The largest is exactly the maximum achievable acoustic energy radiation efficiency , and the corresponding eigenvector is the optimal weight vector we need.

2.2.5. Solution Strategy via Cholesky Whitening

To efficiently solve the generalized eigenvalue problem in Equation (13), we convert it into a standard eigenvalue problem using Cholesky whitening—a technique that eliminates the influence of by transforming the weight vector [42].

Step 1: Cholesky Decomposition of .

Since is Hermitian positive definite, it can be uniquely decomposed into the product of a lower triangular matrix and its Hermitian transpose (Cholesky decomposition) [43]. This decomposition is presented in Equation (14):

The matrix is invertible (as is positive definite), which ensures the validity of subsequent variable transformations.

Step 2: Variable Transformation for Whitening.

Define a new whitened variable as the product of and the original weight vector ; this transformation is presented in Equation (15):

Rearranging Equation (15) gives the inverse transformation: , where denotes the Hermitian transpose of .

Step 3: Conversion to Standard Eigenvalue Problem.

Substitute into the generalized eigenvalue equation (Equation (13)) and left-multiply both sides by . Using for simplification, we obtain a standard eigenvalue equation involving a new Hermitian matrix ; this equation is presented in Equation (16):

where the matrix (whitened version of ) is defined as follows:

The matrix retains the Hermitian property of , ensuring that all its eigenvalues are real and its eigenvectors are mutually orthogonal. This eliminates numerical instability that might arise from the direct inversion of , making the solution process robust.

2.2.6. Derivation of the Optimal Weight Vector

The optimal weight vector is derived by solving the standard eigenvalue problem in Equation (16) and reversing the whitening transformation. The specific steps are as follows.

First, solve Equation (16) to obtain all eigenvalues of and their corresponding eigenvectors . Select the maximum eigenvalue and its associated eigenvector.

Second, substitute into the inverse transformation of Equation (15) to obtain the initial optimal weight vector; this expression is presented in Equation (18):

Third, normalize to satisfy the constraint . Since is typically normalized to unit norm, substituting into the constraint gives directly; thus, the normalized optimal weight vector is , as presented in Equation (19):

The final ensures the maximum acoustic energy radiation efficiency in the target angular domain. Compared with traditional window functions (empirical weights) or evolutionary algorithms (iterative search), this method provides an analytical optimal solution with low computational complexity (dominated by eigenvalue decomposition, for N-element arrays) and high reproducibility (no randomness in results), making it suitable for real-time adaptive adjustment in UAET systems.

3. Results and Discussion

This chapter presents a comprehensive validation of the proposed Rayleigh quotient eigenvalue-based array beam energy aggregation optimization method through simulations and underwater physical experiments, with a focus on quantifying its performance advantages over traditional weighting methods and intelligent optimization algorithms (e.g., PSO). First, the experimental design and setup—including simulation modeling parameters, comparison method configurations, and the construction of the underwater test platform—are detailed to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of results. Subsequently, performance metrics such as target angular energy concentration efficiency, beam pattern (mainlobe width, sidelobe level), and real-time adaptability are analyzed for one-dimensional (1D) linear arrays (8-element and 16-element) and two-dimensional (2D) circular ring arrays. Finally, the engineering significance of the results is discussed, including the method’s applicability to practical UAET systems and potential directions for future optimization.

3.1. Experimental Design and Setup

To systematically evaluate the performance of the proposed method, a consistent experimental framework was established, covering simulation modeling (to verify theoretical performance) and underwater physical tests (to validate engineering feasibility). This section details the key parameters of the simulation, the definition of comparison methods, and the design of the underwater test platform.

3.1.1. Simulation Configuration

Based on the high-resolution spatial finite element modeling method described in references [2,19], numerical simulation and analysis are conducted on the characteristics of array acoustic fields in typical underwater acoustic environments.

Array Types and Geometric Parameters

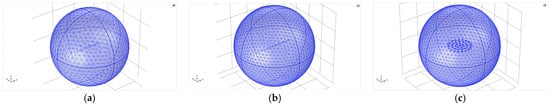

Two representative array structures for UAET applications were selected for simulation, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

(a) 1D 8-element linear array model based on finite element spherical acoustic domain; (b) 1D 16-element linear array model based on finite element spherical acoustic domain; (c) 2D 4-layer circular ring array model based on finite element spherical acoustic domain.

One-dimensional uniform linear arrays (ULAs): Two configurations were tested—an 8-element ULA and a 16-element ULA—with an inter-element spacing (where is the acoustic wavelength at the operating frequency). This spacing avoids grating lobes while balancing array aperture and compactness.

Two-dimensional 4-layer circular ring array: Elements were symmetrically arranged in four concentric rings, with uniform angular spacing within each ring to ensure rotational symmetry of the beam pattern.

Operating Frequency Selection

As described in reference [19], the acoustic energy transfer efficiency of UAET systems exhibits a single-peak frequency response, with the optimal frequency stably falling in the low-to-mid frequency range of 20–100 kHz. In a typical marine environment (temperature T = 20 °C, salinity S = 35‰, and pH = 8), the sensitivity of to propagation distance decreases with increasing distance, forming a near-plateau region at 30–50 kHz. To balance energy transfer efficiency and environmental adaptability, the operating frequency for all simulations and experiments was fixed at 40 kHz.

Acoustic Field Modeling and Boundary Conditions

To simulate a free-field underwater environment (minimizing boundary reflections), the finite element model incorporated an acoustic absorption layer equivalent to the physical anechoic tank (detailed in Section 3.1.3). For the target angular domain , the central angle was set to 0° (the array’s main axis), and the angular width was varied from 5° to 70° to test the method’s adaptability to different receiver sizes.

Calculation of Absorption Wedge Cutoff Frequency

For the simulated anechoic environment, the cutoff frequency of the acoustic absorption wedges (used to suppress boundary reflections) was derived from acoustic theory, where is related to the wedge height h and the speed of sound in water c. This relationship is presented in . In the simulation, the wedge height h was set to 0.20 m, and the speed of sound in water . Substituting these values into the equation gives , ensuring effective absorption of acoustic waves at the 40 kHz operating frequency and eliminating boundary reflection interference in the simulation.

3.1.2. Definition of Comparison Methods

To highlight the performance advantages of the proposed Rayleigh quotient (RQ) optimization method, six traditional window-based weighting methods and the PSO algorithm (a representative intelligent optimization method) were selected as benchmarks. Their key parameters are defined as follows.

Traditional Window-Based Weighting Methods

These methods rely on pre-defined amplitude decay profiles to balance mainlobe width and sidelobe level, with the following configurations.

Rectangular weighting: Equal weights for all elements for ), maximizing mainlobe gain but suffering from high sidelobes.

Hanning weighting: Weight profile follows , providing moderate sidelobe suppression (~−31 dB) at the cost of mainlobe widening.

Hamming weighting: Weight profile follows , offering better sidelobe suppression (~−40 dB) than Hanning weighting.

Blackman weighting: Weight profile follows , achieving the strongest sidelobe suppression (~−57 dB) among the six methods.

Dolph–Chebyshev weighting: The maximum sidelobe level was strictly constrained to −45 dB, generating an equiripple sidelobe envelope.

Kaiser weighting: The shape factor was selected, balancing mainlobe width and sidelobe suppression (~−30 dB) to align its performance between Hanning and Hamming weighting.

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) Algorithm

PSO was configured to solve the same target angular energy maximization problem, with parameters tuned to ensure stable convergence.

Population size: 40 particles (balancing search diversity and computational efficiency).

Maximum iterations: 100 (sufficient to avoid premature convergence to local optima).

Inertia weight: Dynamically adjusted from 0.9 to 0.4 using a linear decay strategy. This strategy enhances global exploration in the early stages and local refinement in the late stages:

where = 0.9 (initial inertia weight), = 0.4 (final inertia weight), t is the current iteration number, and (maximum iterations).

Learning factors: (balancing the influence of individual historical optima and global optima on particle movement).

Objective function: Consistent with the proposed method, defined as the acoustic energy radiation efficiency to ensure fair comparison.

3.1.3. Experimental Setup

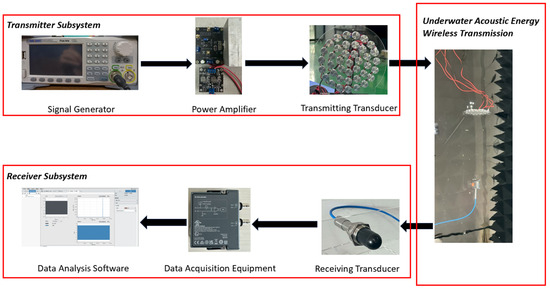

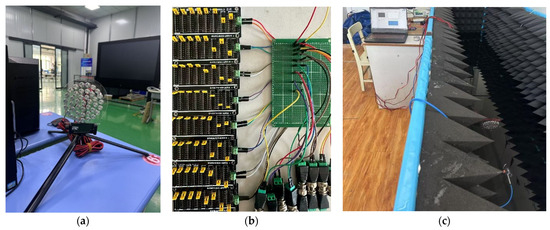

Underwater Physical Test Platform

A closed-loop underwater test system was constructed to validate the proposed method in a real acoustic environment, consisting of five modules: signal generation, power amplification, transducer array, anechoic tank, and data acquisition/analysis. The system framework is shown in Figure 3 of the reference document, with key components detailed below.

Figure 3.

Experimental framework for actual underwater environment testing.

Signal Generation and Power Amplification Signal Source

A SIGLENT SDG2042X function generator was used to output a 40 kHz pure sine wave, with amplitude and phase stabilized via pre-test self-calibration to suppress harmonic distortion (<1%). Power amplifier: A linear power amplifier was employed to amplify the signal to a rated drive voltage of , ensuring low total harmonic distortion (THD < 0.5%) at 40 kHz to maintain stable acoustic radiation.

Transducer Array Design and Calibration

Transducer selection and impedance calibration: Piezoelectric transducers with a resonant frequency of ~40 kHz were selected (consistent with the operating frequency). An Tonghui TH2861B impedance analyzer was used to measure the impedance characteristics of each transducer, and transducers with impedance variations <5% were screened to ensure uniform element performance.

Amplitude weight implementation: To apply the optimized amplitude weights to the physical array, a voltage divider circuit was designed—different resistors were connected in series with each transducer’s drive loop to adjust the drive voltage amplitude. The relationship between the transducer drive voltage and the series resistor follows Ohm’s law, where is proportional to the transducer impedance and inversely proportional to the sum of and . This relationship is presented in Equation (21):

Here, is the input voltage from the power amplifier and is the transducer impedance (stable at 40 kHz), ensuring linear and repeatable amplitude control.

Waterproof packaging and mounting: Transducers and arrays were coated with waterproof potting compound to prevent water intrusion, and a dedicated rotating bracket was installed to adjust the array’s pointing angle (with an angular resolution of ±1°) during testing.

Anechoic Tank Design

To replicate a free-field environment, the inner walls of the test tank (1.5 m × 1.5 m × 2.0 m) were lined with polyurethane acoustic absorption wedges (tip size of 10 cm × 10 cm, height of 20 cm). The cutoff frequency of the wedges is ~1.9 kHz, which effectively absorbs acoustic waves at 40 kHz and reduces boundary reflections to <1% of the incident sound pressure—eliminating interference from reflected waves in physical tests.

Data Acquisition and Calibration

Receiver: A custom hydrophone with a frequency range of 2 Hz–200 kHz and a sensitivity of −183 dB V/μPa was used, with a built-in 10× preamplifier to enhance signal-to-noise ratio (SNR).

Data acquisition module: A National Instruments (NI) 9250 module (2-channel, 102.4 kS/s maximum sampling rate, and 24-bit Δ-Σ ADC) was used to collect the hydrophone’s output voltage signals. The module includes an adaptive anti-aliasing filter to suppress noise above the Nyquist frequency.

Signal post-processing: Collected voltage signals were first filtered with a 35–45 kHz bandpass filter to extract the 40 kHz fundamental component. The voltage signal was then converted to sound pressure using the hydrophone’s receive voltage sensitivity (RVS), as presented in Equation (22):

Here, is the measured voltage (in V), is the hydrophone sensitivity, and is the preamplifier gain. Finally, the sound pressure level (SPL) was calculated as , where is the reference sound pressure.

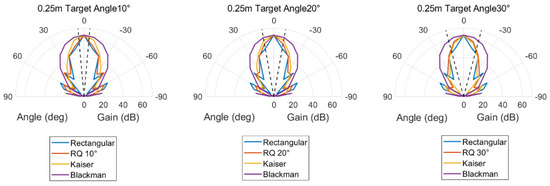

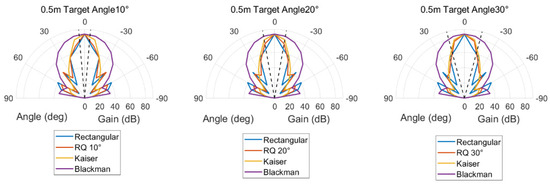

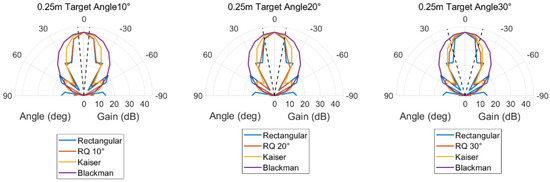

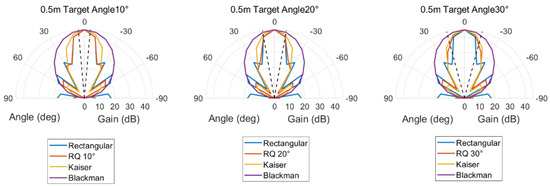

Test Procedure

During physical tests, the hydrophone position was fixed, and the array was rotated (in 10° steps) to scan the acoustic field in the forward hemisphere (0–90°). For each angle, the voltage signal was collected and processed to generate the beam pattern. Transmission distances of 0.25 m, 0.5 m, and 1 m were tested to analyze the method’s performance in both near-field and far-field conditions.

3.2. Results of 1D Linear Array Experiments

To verify the performance of the proposed method in one-dimensional (1D) scenarios, 8-element and 16-element uniform linear arrays (ULAs) were tested under consistent simulation and physical experimental conditions. This section focuses on three core analyses: (1) performance comparison between the proposed Rayleigh quotient (RQ) optimization method and the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm; (2) energy concentration characteristics of traditional window-based weighting methods; (3) acoustic energy radiation performance of the RQ method; and (4) scalability verification via array size variation.

3.2.1. Performance Comparison Between PSO and RQ Optimization Methods

Particle swarm optimization (PSO) is widely adopted for complex optimization problems due to its high efficiency and global search capability. To verify the performance advantages of the proposed Rayleigh quotient (RQ) optimization method, this section establishes a PSO-based optimization model for array weight design targeting angular energy concentration. A comprehensive comparison is conducted between PSO-optimized weights and the theoretically optimal weights from the RQ method, focusing on differences in weight distribution, beam pattern, acoustic energy radiation efficiency, and result stability. Note that PSO parameters and the objective function have been defined in Section 3.1.2; the PSO solution flow follows the iterative update logic detailed therein (including particle velocity/position update, local/global optimum maintenance, and linear decay of inertia weight), and it is not repeated herein.

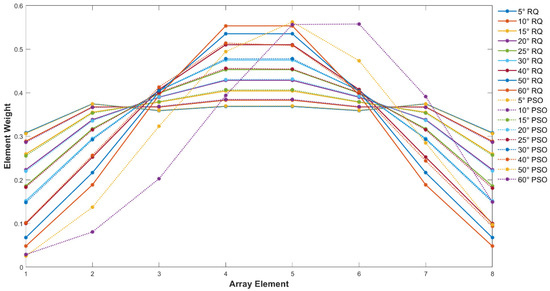

To compare the weight distribution differences between PSO and the RQ method, an experiment was conducted on an 8-element linear array: under the PSO parameter settings in Section 3.1.2, the optimal weight vector was solved via iterative search, while the RQ method derived the theoretical optimal weight vector through generalized eigenvalue decomposition (Section 2.2). The amplitude weight distributions of the two methods are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Weight distribution comparison between RQ optimization and PSO for 8-element linear array.

For PSO, the weights exhibit a non-strictly symmetric pattern: central elements have higher weights and edge elements have lower weights (consistent with the energy concentration goal), but slight random fluctuations appear in the weights of left and right edge elements. This phenomenon arises from PSO’s stochastic search nature—without explicit constraints on array geometric symmetry, even approximately symmetric weight patterns are accompanied by unavoidable randomness. In contrast, the RQ method’s weights are strictly symmetric about the array center, showing a smooth tapered decay from the center to the edges. This symmetry is a natural consequence of the Toeplitz–sinc structure of the target-domain energy operator matrix , which inherently embeds array geometric information, ensuring the weights align with the array’s physical symmetry and better meet the requirement of optimal energy concentration under symmetric layouts.

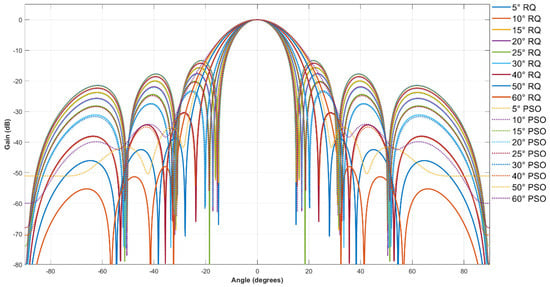

To further verify how weight distribution differences affect array directivity, the beam patterns of the 8-element linear array under PSO and RQ weighting were calculated and compared. The experiment maintained consistent array parameters (element spacing, and operating frequency 40 kHz) and target angular domain (central angle, width) for both methods, and the resulting beam patterns are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Beam pattern comparison between RQ optimization and PSO for 8-element linear array.

Both methods generate mainlobes that accurately point to the target angular domain (0°), with nearly identical mainlobe gain and shape—indicating PSO can achieve beamforming performance close to the theoretical optimum in terms of mainlobe gain and direction. In terms of sidelobe suppression, both methods control the maximum sidelobe level below −30 dB, effectively reducing energy leakage to non-target regions. However, the RQ method’s sidelobe envelope is smoother, with no random fluctuations in sidelobe amplitude observed in PSO results. This stability is critical for underwater acoustic energy transmission systems, as random sidelobe fluctuations may cause unexpected energy leakage and reduce the reliability of underwater energy reception. The consistency in mainlobe performance between PSO and the RQ method also indirectly validates the RQ optimization model’s effectiveness: PSO, as a global search tool, converges to a solution close to the RQ theoretical optimum, confirming the RQ method correctly captures the core objective of angular energy concentration.

To quantify the performance gap between PSO and the RQ method, the same 8-element linear array experiment was extended: for each target angular width (5° to 60°), the mean acoustic energy radiation efficiency of 10 PSO runs and the standard deviation were calculated and compared with the RQ method’s theoretical optimal efficiency (, Section 2.2.4). The relative error between the two methods was used to evaluate PSO’s proximity to the theoretical optimum, with the relative error formula defined as Equation (23):

The comparison results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of energy concentration performance between PSO and RQ methods under different target angular widths.

It can be observed that the relative error ranges from 0.02% to 0.27%, indicating is very close to —confirming PSO can find weight combinations that achieve near-optimal energy concentration in the target angular domain, regardless of width. However, PSO’s standard deviation increases with angular width (e.g., 0.15% for 5° vs. 0.91% for 60°), as wider angular domains expand the solution space and increase the uncertainty of random search.

In contrast, the RQ method produces a unique, deterministic solution with zero volatility. Since it directly solves the analytical model via linear algebra, the weight solution has absolute uniqueness and high consistency, unaffected by random initial conditions and exhibiting strong repeatability and stability. This advantage is critical for engineering applications (e.g., underwater sensor network power supply) that demand consistent performance.

As a meta-heuristic algorithm, PSO does not guarantee unique solutions; multiple runs are required to improve confidence in finding optimal/near-optimal solutions, increasing the cost of result verification and optimization in engineering. Additionally, PSO-optimized solutions lack explicit analytical forms, hindering physical interpretation and further theoretical analysis. In contrast, the RQ method provides an analytical optimal solution with clear physical meaning and low computational complexity. When the target angular domain changes, the RQ method only needs to reconstruct and perform eigenvalue decomposition, avoiding PSO’s time-consuming iterative search—making it more suitable for UAET systems requiring real-time adaptation and high reliability. In summary, while PSO achieves near-optimal energy concentration, the RQ method outperforms PSO in solution optimality, repeatability, and engineering practicality—confirming its superiority for array angular energy concentration in UAET applications.

Computational Complexity Analysis: PSO Versus RQ Methods

To further elucidate the performance difference between the Rayleigh quotient (RQ) optimization method and the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm, a rigorous comparison of their computational complexities and solution characteristics is essential—particularly for real-time adaptive UAET applications where computational efficiency and result reproducibility are critical.

Computational Complexity

For the PSO algorithm, the total computational cost is determined by the population size , maximum iterations , and per-iteration fitness evaluation cost. Each fitness evaluation requires computing the acoustic energy radiation efficiency (Equation (8)), which involves numerical integration of beam patterns over the target angular domain and the entire hemisphere. Given an array of elements, the beam function evaluation scales as per angle, and angular integration with discretization points yields per fitness evaluation. Across particles and iterations, the total complexity becomes the following:

For moderate-to-large arrays (e.g., , for 1° resolution) with typical PSO parameters (, , as defined in Section 3.1.2), this results in operations per optimization—a substantial burden for iterative weight updates. Moreover, PSO’s stochastic nature necessitates multiple independent runs to validate convergence stability (as demonstrated in Table 1, where 10 runs were required), further amplifying the total computational time by an order of magnitude.

In contrast, the RQ method transforms the optimization into a generalized eigenvalue decomposition problem of two Hermitian matrices ( and , Section 2.2). The dominant computational steps include the following: (1) construction of Toeplitz–sinc-structured matrices via analytical integration (); (2) Cholesky decomposition of (); and (3) eigenvalue decomposition of the whitened matrix (). Thus, the total complexity is as follows:

For an array, this amounts to operations using efficient eigensolvers (e.g., LAPACK’s DSYEVD)—four orders of magnitude faster than PSO. Critically, the RQ method only requires a single execution per target angular domain , whereas PSO demands full iterative searches for every change in (target width) or (central angle), rendering it impractical for dynamic UAET scenarios requiring frequent weight adaptation.

Solution Optimality and Reproducibility

The PSO algorithm approximates the global optimum through stochastic particle exploration, but offers no theoretical guarantee of achieving the true maximum . As shown in Table 1, the relative error between PSO’s mean efficiency and the RQ theoretical optimum ranges from 0.02% to 0.27%—indicating near-optimal performance. However, the standard deviation increases with target angular width (e.g., 0.15% for vs. 0.91% for ), reflecting sensitivity to initialization and random search trajectories. This variability undermines reliability in precision-critical UAET applications, where consistent beam performance is paramount.

By contrast, the RQ method derives the analytical optimal solution via Rayleigh quotient maximization (Section 2.2.4): the optimal weight vector is rigorously proven to be the eigenvector corresponding to the maximum eigenvalue of the generalized eigenvalue problem . This deterministic process guarantees the following: (1) absolute optimality (), as established by Rayleigh quotient theory [40]; (2) zero run-to-run variability, since eigenvalue decomposition is a fixed algebraic operation independent of random seeds; and (3) physical interpretability, as corresponds to the Discrete Prolate Spheroidal Sequence (DPSS) that maximizes energy concentration in (Section 2.2.3).

Engineering Implications for UAET Systems

For real-time adaptive beamforming—where the target angular domain changes dynamically as underwater platforms move or receiver apertures vary—the RQ method’s complexity and single-execution paradigm enable rapid weight recalculation. On a standard CPU (Intel i7, 3.5 GHz), the RQ solution for a 16-element array completes in ms, compared to s for PSO (100 iterations × 40 particles × 10 runs for stability)—a speedup exceeding . This latency reduction is decisive for UAET applications requiring sub-second adaptation (e.g., tracking moving AUVs or compensating for dynamic multipath interference).

Furthermore, the RQ method’s reproducibility eliminates the need for convergence validation across multiple runs, streamlining engineering deployment. PSO’s “black-box” weight solutions lack analytical transparency, complicating troubleshooting and theoretical extension; conversely, the RQ method’s closed-form eigenvector solution facilitates integration with existing UAET control systems and enables straightforward extension to 3D arrays or frequency-dependent optimization.

In summary, while PSO demonstrates competitive energy concentration performance (as evidenced by the near-zero relative errors in Table 1), the RQ method fundamentally outperforms PSO in computational efficiency (4–5 orders of magnitude faster), solution optimality (guaranteed analytical maximum), and engineering practicality (deterministic, reproducible, and real-time capable). These advantages position the RQ method as the superior choice for UAET array beamforming, particularly in dynamic underwater environments demanding robust, adaptive, and theoretically optimal energy transmission.

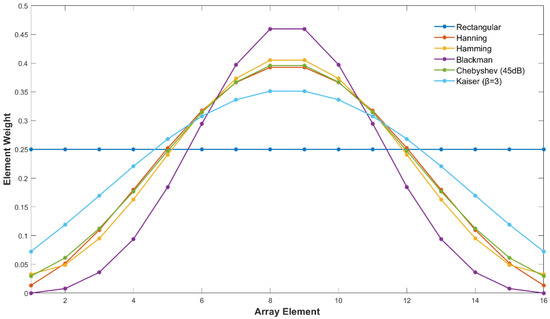

3.2.2. Performance of Classical Amplitude-Weighting Methods

To establish a performance baseline for the proposed RQ optimization method, this section evaluates six classical window-based amplitude-weighting methods (detailed in Section 3.1.2: Rectangular, Hanning, Hamming, Blackman, Dolph–Chebyshev, and Kaiser weighting) on an 8-element uniform linear array (ULA). The experiment maintained consistent array parameters, target angular domain, and central angle to ensure fair comparison, focusing on analyzing two core characteristics: weight distribution patterns and the inherent trade-off between mainlobe width and sidelobe level in beam patterns—both of which directly affect acoustic energy concentration in UAET scenarios.

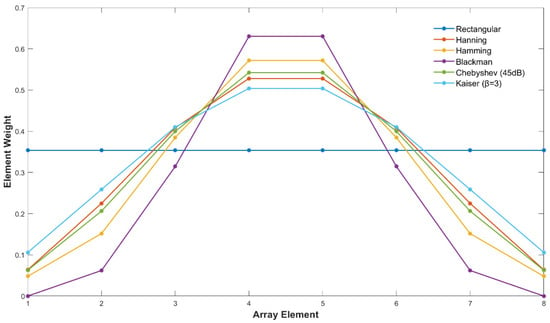

To investigate how classical weighting methods adjust element amplitudes, the weight vectors of the six methods for the 8-element ULA were calculated under the parameter settings in Section 3.1.2, and their spatial distributions are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Weight distribution of classical amplitude-weighting methods for 8-element linear array.

The weights exhibit a clear gradient from flat to sharp decay, following the order of Rectangular, Kaiser, Hanning, Dolph–Chebyshev, Hamming, and Blackman weighting. Rectangular weighting assigns equal amplitudes to all elements, showing no spatial variation and fully utilizing each element’s radiation capability. Kaiser and Dolph–Chebyshev weighting present moderate edge attenuation, forming a monotonic, symmetric tapered distribution that balances energy utilization and sidelobe suppression. Hanning and Hamming weighting enhance edge decay further, with a more obvious tapered gradient—sacrificing partial edge element contribution to achieve stronger sidelobe suppression. Blackman weighting shows the sharpest decay, with edge element weights suppressed to less than 5% of central element weights—effectively reducing the radiation contribution of edge elements to maximize sidelobe suppression. This gradient directly reflects the empirical design logic of classical methods: they rely on pre-defined fixed amplitude profiles rather than optimization tailored to specific target angular domains, which inherently limits their ability to adapt to varying angular energy concentration demands in UAET scenarios.

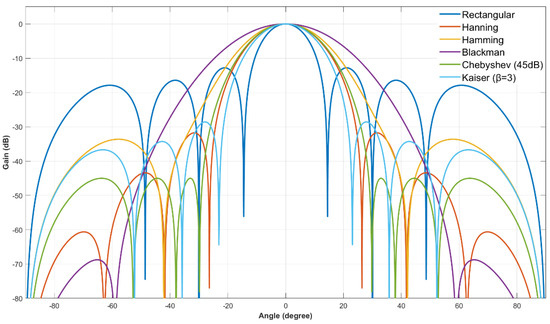

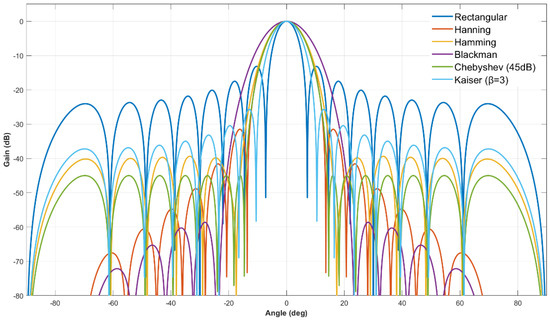

To quantify how weight distribution affects array directivity, the beam patterns of the six classical methods were simulated for the 8-element ULA, with results shown in Figure 7. The patterns reveal an inherent trade-off between mainlobe width and sidelobe level—a key limitation of classical weighting.

Figure 7.

Beam pattern comparison of classical amplitude-weighting methods for 8-element linear array.

In terms of mainlobe width, Rectangular weighting has the narrowest mainlobe, which is favorable for concentrating energy in small target domains. However, this comes at the cost of the highest peak sidelobe level (approximately −13 dB), leading to severe energy leakage to non-target regions. In contrast, Blackman weighting achieves the most significant sidelobe suppression among the six classical methods, but its mainlobe width is expanded to nearly twice that of Rectangular weighting—greatly reducing the energy density in the target-domain and compromising energy concentration efficiency. Hanning, Hamming, Kaiser, and Dolph–Chebyshev weighting fall between these two extremes: Hanning and Hamming weighting exhibit moderate mainlobe widths and sidelobe suppression levels, with sidelobe levels lower than that of Rectangular weighting but higher than that of Blackman weighting; Dolph–Chebyshev weighting has its maximum sidelobe strictly constrained to −45 dB, forming an equiripple sidelobe envelope, and its mainlobe width lies between that of Rectangular weighting and Blackman weighting; Kaiser weighting (with shape factor ) achieves approximately −30 dB sidelobe suppression, with only moderate mainlobe widening, making its overall performance align between Hanning weighting and Hamming weighting.

For UAET systems, this trade-off creates a dilemma: narrow mainlobes (e.g., Rectangular weighting) waste energy via high sidelobes, while wide mainlobes (e.g., Blackman weighting) dilute energy in the target domain. This limitation highlights the need for the RQ method, which adaptively optimizes weights based on the target angular domain to resolve this trade-off.

3.2.3. Acoustic Energy Radiation Performance of RQ Optimization Methods

The core advantage of the RQ method lies in its adaptive weight adjustment based on the target angular domain —a capability that resolves the mainlobe–sidelobe trade-off of classical methods and maximizes acoustic energy radiation efficiency . This section evaluates this performance using the 8-element ULA, with experiments designed to verify how the RQ method adjusts weights as the target angular width varies (2° to 140°), analyze the stability of its beam pattern, and quantify its energy efficiency advantage over classical methods—all under consistent array parameters.

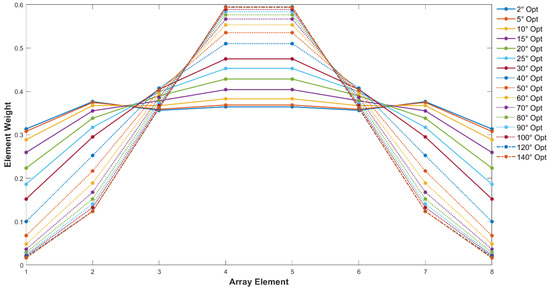

To investigate the RQ method’s adaptivity, the optimal weight vectors for the 8-element ULA were calculated across different target angular widths (2° to 140°) via generalized eigenvalue decomposition (Section 2.2), and their distributions are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Weight distribution of RQ optimization method for 8-element linear array under different target angular widths.

The weights exhibit a dynamic adjustment pattern that aligns with the target angular domain: for narrow angular domains, the weights are nearly uniform, with differences between central and edge elements less than 5%. This flat distribution mimics Rectangular weighting, enabling narrow mainlobes to concentrate energy in small target regions, which are critical for UAET scenarios with compact receivers. For wide angular domains, the weights transition to a smooth tapered decay (similar to Hamming weighting), with edge weights reduced to ~40% of central weights. This taper suppresses sidelobes while moderately expanding the mainlobe to cover the wide target domain, avoiding energy leakage. This adaptivity is driven by the Toeplitz–sinc structure of the target-domain energy operator matrix (Section 2.2.3): as increases, the maximum eigenvector of (i.e., the RQ optimal weight vector) naturally shifts from uniform to tapered, reflecting the energy concentration principle of Discrete Prolate Spheroidal Sequences (DPSS) and ensuring optimal adaptation to varying target sizes.

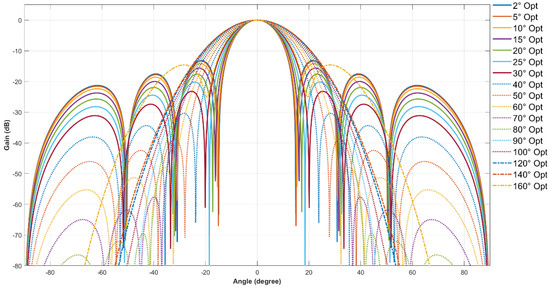

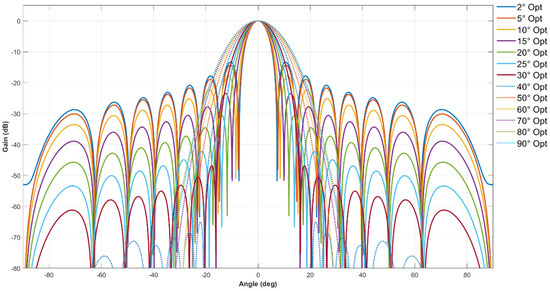

To verify the beam stability of the RQ method under varying target angular domains, an experiment was conducted on an 8-element uniform linear array (ULA). The array parameters were kept consistent throughout the experiment. Only the target angular width was adjusted (ranging from 2° to 140°). For each , the optimal weight vector of the RQ method was solved via generalized eigenvalue decomposition (Section 2.2), and the corresponding beam pattern was generated; the results are presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Beam pattern of RQ optimization method for 8-element linear array under different target angular widths.

As shown in Figure 9, all mainlobes of the RQ method strictly point to the target central angle (0°), confirming the stability of beam pointing—this is an essential feature for UAET systems, as they require precise energy delivery to fixed underwater receivers. When is narrow, the RQ method’s weight distribution is nearly uniform (consistent with the analysis in Section 3.2.1), resulting in a mainlobe width close to that of Rectangular weighting; meanwhile, its sidelobe level is significantly lower than that of Rectangular weighting, effectively eliminating excessive energy leakage to non-target regions. When is wide, the RQ method’s weights transition to a smooth tapered decay, causing the mainlobe to expand moderately, but the mainlobe width remains narrower than that of Blackman weighting. Additionally, the sidelobe level is maintained at a low level, which is sufficient to suppress energy in non-target areas without over-diluting the energy density in the mainlobe. This stability in beam pointing and balance between mainlobe width and sidelobe level are unattainable with classical weighting methods, as classical methods use fixed weight profiles that do not adjust with changes in Δ.

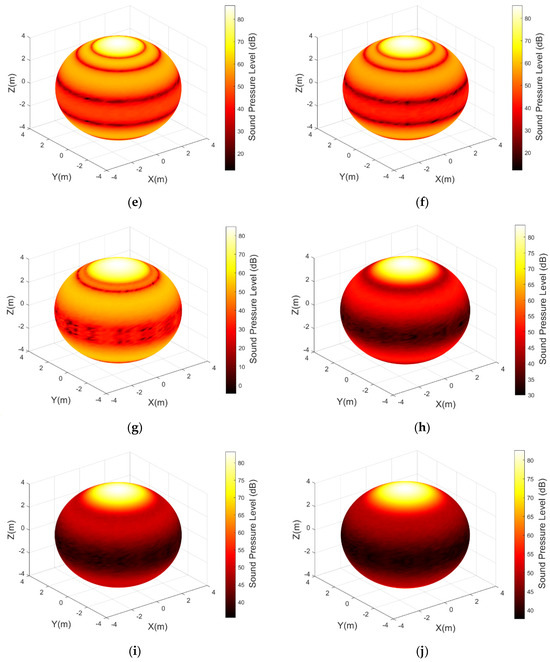

To quantify the RQ method’s energy efficiency, (ratio of target-domain energy to total radiated energy) was calculated for the RQ method and six classical methods across the 0–180° angular range, with results shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Acoustic energy radiation efficiency comparison between RQ optimization method and classical weighting methods for 8-element linear array.

As illustrated in Figure 10, the RQ method outperforms classical methods in all angular domains, with the most significant advantage observed in the 0–30° narrow angular range, a typical scenario for small underwater receivers. This advantage stems from the RQ method’s direct optimization of , whereas classical methods optimize indirect metrics (e.g., sidelobe level) that do not guarantee target energy maximization. By directly maximizing the ratio of target to total energy via generalized Rayleigh quotient, the RQ method ensures optimal energy utilization for UAET.

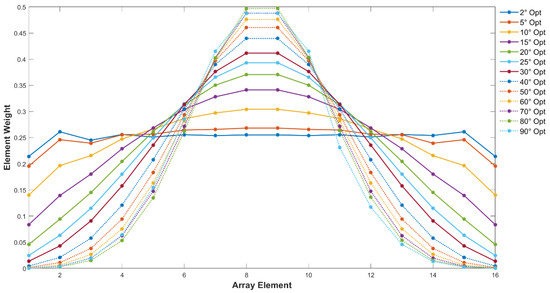

3.2.4. Comparison of Arrays with Different Sizes

To verify the scalability of the proposed RQ method— a key requirement for adapting to underwater acoustic energy transmission systems with varying aperture demands—this section compares its performance on 8-element and 16-element uniform linear arrays (ULAs). A consistent experimental framework was adopted for both arrays to isolate the impact of array size. Experiments focused on three core metrics: weight distribution (to reflect amplitude adjustment precision), beam pattern (to evaluate directivity improvement), and acoustic energy radiation efficiency (to quantify energy concentration performance).

To investigate how array size affects weight modulation, weight vectors of six classical weighting methods and the RQ method were calculated for the 16-element ULA. Weight distributions of classical methods and the RQ method for the 16-element ULA are presented in Figure 11 and Figure 12, respectively, with comparisons to the 8-element ULA results.

Figure 11.

Weight distribution of classical amplitude-weighting methods for 16-element linear array.

Figure 12.

Weight distribution of RQ optimization method for 16-element linear array under different target angular widths.

For classical weighting methods, the 16-element ULA retains the same “flat-to-sharp decay” gradient as the 8-element ULA but exhibits finer spatial modulation. For example, Blackman weighting—known for sharp edge attenuation—reduces edge element weights to less than 2% of central element weights in the 16-element array, intensifying edge suppression to compensate for the larger aperture and avoid excessive sidelobe leakage. Other methods (e.g., Hanning, Hamming) show similar trends: edge-to-center weight ratios are more extreme in the 16-element array, reflecting classical methods’ empirical attempt to balance directivity and sidelobes for larger apertures.

For the RQ method, scalability is manifested in more precise adaptive adjustment. When (narrow target domain), the central 12 elements of the 16-element array have weight differences of less than 5% (vs. less than 5% in the 8-element array), enabling more uniform energy allocation and sharper mainlobes. When (wide target domain), the 16-element array’s weight decay is smoother, with no abrupt amplitude changes that could induce grating lobes—a critical advantage for large arrays, where spatial aliasing risks increase with aperture size. This precision stems from the RQ method’s reliance on the Toeplitz–sinc structure of , which naturally scales with array size to maintain optimal energy concentration.

To quantify directionality improvements with increased array size, beam patterns of the 16-element ULA under classical and RQ weighting were simulated. The experiment maintained consistent target angular domain parameters for both 8-element and 16-element arrays, enabling direct comparison of mainlobe width and sidelobe level. Beam patterns of classical methods and the RQ method for the 16-element ULA are shown in Figure 13 and Figure 14, respectively.

Figure 13.

Beam pattern comparison of classical amplitude-weighting methods for 16-element linear array.

Figure 14.

Beam pattern of RQ optimization method for 16-element linear array under different target angular widths.

Regardless of the weighting method, the 16-element array exhibits significantly enhanced directionality compared to the 8-element array. For classical methods, Rectangular weighting—known for the narrowest mainlobe among classical approaches—shows a clear reduction in mainlobe width with increased array size: the 3 dB mainlobe width of the 16-element array (~6.4°) is approximately half that of the 8-element array (~12.8°), confirming the inverse relationship between array size and mainlobe width for uniform inter-element spacing. However, Rectangular weighting’s sidelobe level remains consistently high across both array sizes, highlighting its inherent limitation of insufficient sidelobe suppression—a flaw that cannot be resolved by simply increasing array size.

For the RQ method, the 16-element array further refines beam performance. Compared to the 8-element array, the 16-element array’s RQ-derived beam patterns exhibit narrower mainlobes (~5.5°) under the same target angular width ; meanwhile, sidelobe suppression is also enhanced, effectively reducing energy leakage to non-target regions. This improvement stems from the larger aperture providing more degrees of freedom for weight optimization: the RQ method leverages the additional elements to adjust amplitude weights more precisely, balancing mainlobe narrowing and sidelobe suppression. In contrast, classical methods only scale their fixed weight profiles with array size—they can narrow the mainlobe proportionally but cannot fundamentally improve the trade-off between mainlobe width and sidelobe level, nor enhance energy concentration logic.

Notably, all RQ-derived beam patterns for the 16-element array maintain stable mainlobe pointing (strictly aligned with the target central angle of 0°) across different , which is consistent with the performance of the 8-element array. This confirms the RQ method’s robustness to changes in array size—a critical feature for engineering applications where system configurations may need to be adjusted based on practical demands.

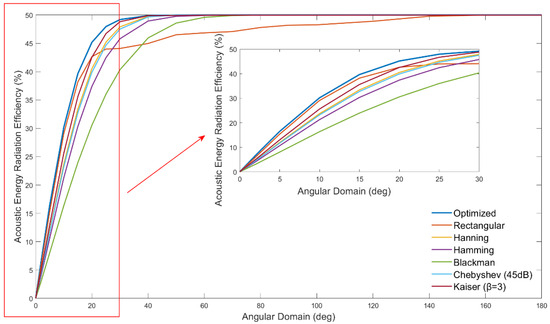

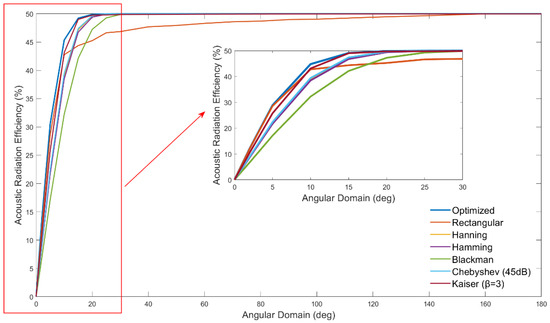

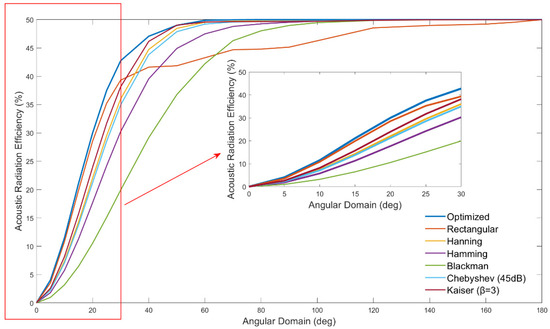

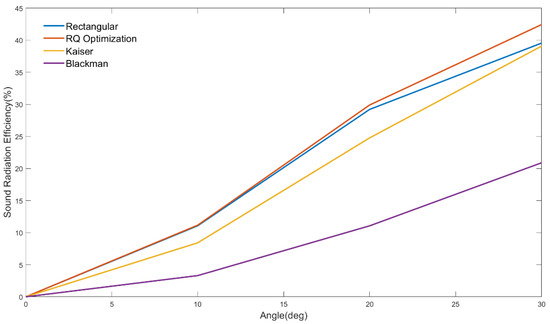

To evaluate how array size amplifies the RQ method’s energy efficiency advantage, the acoustic energy radiation efficiency (defined as the ratio of energy in the target angular domain to the total radiated energy) was calculated for 16-element arrays under the RQ method. The experiment covered target angular widths (typical scenarios for small-to-medium-sized underwater receivers) and compared the RQ method’s with that of classical methods to quantify the amplification of performance advantages. Results are presented in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Acoustic energy radiation efficiency comparison between RQ optimization method and classical weighting methods for 16-element linear array.

The overall curve shows that the optimized weighting method outperforms traditional weighting techniques in terms of acoustic energy radiation efficiency across the entire 0–180° angular range. This advantage is particularly pronounced in the narrow 0–30° angular domain (as shown in the zoomed-in inset marked by the red box in the Figure): compared with Rectangular weighting, the energy radiation efficiency of the optimized method increases by approximately 4 percentage points, and by approximately 14 percentage points compared with Blackman weighting. The magnitude of this performance improvement is significantly higher than that of the 8-element array, indicating that the optimized method can fully leverage the increased element degrees of freedom to enhance energy-focusing performance. This confirms that the optimized weighting method can concentrate more acoustic energy toward the target direction, improving energy transfer efficiency. Similar to the 8-element linear array, the optimized weighting method for the 16-element linear array achieves maximization of main beam energy allocation and sidelobe suppression under different angular domain constraints by adaptively adjusting the weight distribution, effectively resolving the inherent trade-off between mainlobe width and sidelobe suppression in traditional methods.

By comparing the experimental results of the 8-element and 16-element arrays, the following key conclusions can be drawn: First, the increase in the number of elements provides a larger design space for the optimization algorithm, enabling more precise beam control and higher energy radiation efficiency. Second, the performance advantage of the optimized method increases with the array scale, demonstrating its excellent scalability. Finally, while maintaining the adaptive characteristics of the optimized method, the 16-element array achieves a better comprehensive performance balance among “mainlobe width–sidelobe suppression–energy efficiency”. The analysis results of the 16-element linear array mutually confirm those of the 8-element linear array, further highlighting the significant advantages of the proposed optimized weighting method over traditional weighting methods in improving acoustic energy radiation efficiency and beamforming performance. Moreover, this advantage becomes even more pronounced as the array scale increases, providing more valuable reference for the design and optimization of underwater acoustic energy transfer systems.

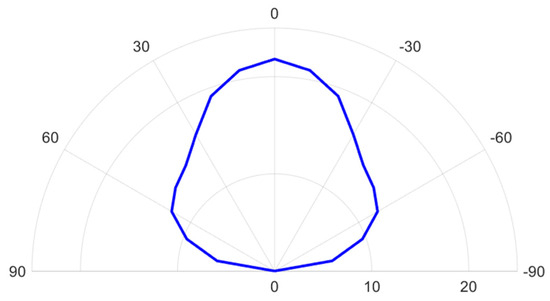

3.3. Results of 2D Circular Ring Array Experiments

Two-dimensional (2D) circular ring arrays are widely used in UAET systems requiring wide-range or omnidirectional energy coverage (e.g., underwater sensor network charging), as their rotational symmetry ensures uniform beam performance in the azimuthal direction. This section focuses on a 4-layer circular ring array—a representative 2D structure with symmetrically arranged elements in four concentric rings—to validate the proposed RQ method. Experiments maintained consistent parameters with 1D linear array tests to ensure cross-comparability. The core objectives are to (1) verify the RQ method’s adaptive weight adjustment capability for 2D structures, (2) analyze its beam pattern control and spherical acoustic field concentration performance, and (3) quantify its energy efficiency advantage over classical methods.

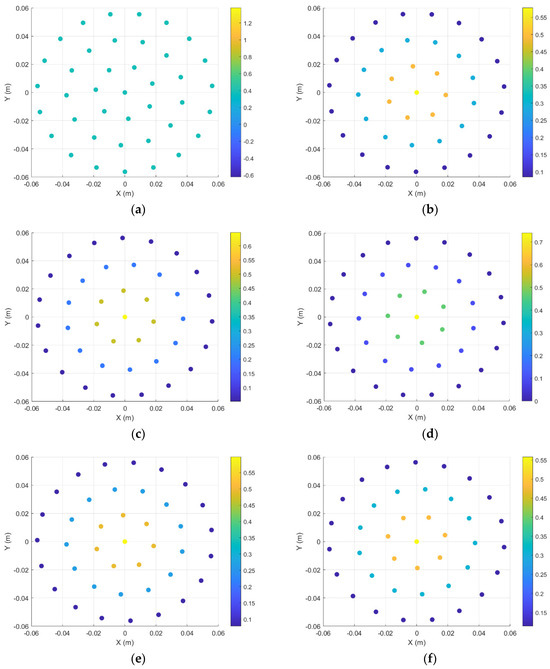

3.3.1. Weight Distribution Characteristics

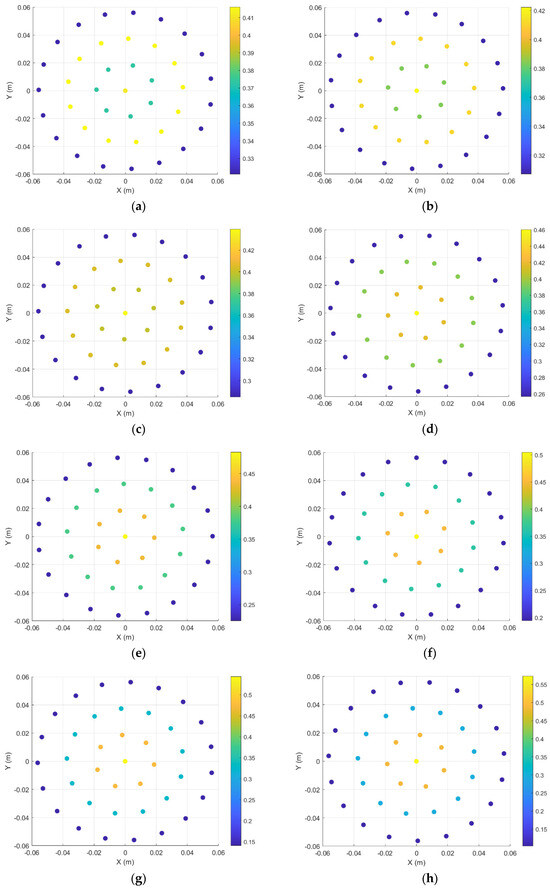

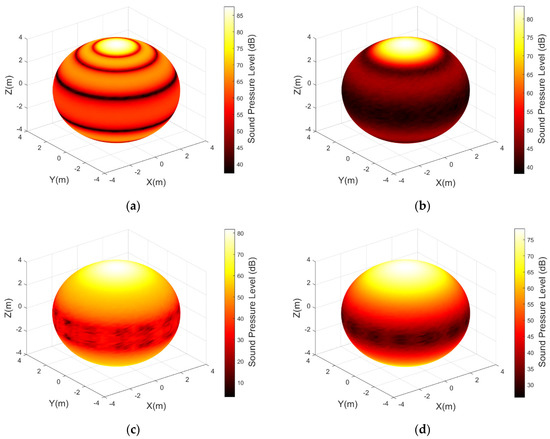

To investigate how weighting methods adjust element amplitudes in 2D circular ring arrays, weight vectors of six classical methods and the RQ method were calculated for the 4-layer circular ring array. For classical methods, parameters followed Section 3.1.2. For the RQ method, optimal weight vectors under different target angular widths were solved via generalized eigenvalue decomposition (Section 2.2), leveraging the Hermitian positive definite property of the target-domain energy operator matrix . Weight distributions of classical methods and the RQ method are presented in Figure 16 and Figure 17, respectively.

Figure 16.

(a) Weight distribution of Rectangular weighting method; (b) weight distribution of Hanning weighting method; (c) weight distribution of Hamming weighting method; (d) weight distribution of Blackman weighting method; (e) weight distribution of Dolph–Chebyshev weighting method; (f) weight distribution of Kaiser weighting method.

Figure 17.

(a) Weight distribution of 5° angular domain optimized weighting method; (b) weight distribution of 10° angular domain optimized weighting method; (c) weight distribution of 15° angular domain optimized weighting method; (d) weight distribution of 20° angular domain optimized weighting method; (e) weight distribution of 25° angular domain optimized weighting method; (f) weight distribution of 30° angular domain optimized weighting method; (g) weight distribution of 40° angular domain optimized weighting method; (h) weight distribution of 50° angular domain optimized weighting method; (i) weight distribution of 60° angular domain optimized weighting method; (j) weight distribution of 70° angular domain optimized weighting method.

As shown in Figure 16, all six weighting methods exhibit symmetric amplitude distribution characteristics about the array center, but there are differences in their respective weight gradient variation patterns. According to the increasing order of edge attenuation degree, these weighting methods can be divided into the following levels: Rectangular weighting maintains a constant weight amplitude throughout the array layout, with no obvious gradient variation; Kaiser weighting and Dolph–Chebyshev weighting adopt a moderate edge element weight attenuation strategy, achieving a distribution pattern with higher central weights and moderately reduced edge weights; Hanning weighting and Hamming weighting further enhance the edge attenuation effect, forming a more obvious weight gradient distribution; Blackman weighting further intensifies edge attenuation, with element weights dropping to near zero when approaching the outer layer of the array. Through comparative analysis with linear arrays, it can be seen that the weight distribution of the 2D circular ring array maintains similar basic weight distribution characteristics to those of linear arrays.

As shown in Figure 17, the weight distribution of the 2D circular ring array under different target angular range conditions using the Rayleigh quotient optimization weighting method exhibits adaptive characteristics similar to those of linear arrays. This method dynamically adjusts the element amplitude weights according to the set “target angular range” to optimize the proportion of radiated power in the target domain. When the target coverage angular range is small, the optimization result tends to assign nearly uniform and higher weights to each element, thereby making full use of the array aperture to obtain a narrow mainlobe and highly concentrated forward energy; when the target angular range is large (requiring coverage of a wider sector), the algorithm adjusts to increase the weight attenuation degree at the array edges, forming a more obvious amplitude gradient to moderately expand the mainlobe coverage range. Its physical meaning is as follows: by establishing a Rayleigh quotient optimization criterion for the array’s acoustic radiation power between the “acceptance” region (target angular domain) and the “suppression” region (non-target angular domain), the weight distribution obtained by the algorithm (the eigenvector of the generalized eigenvalue problem) is exactly the distribution scheme that optimizes the ratio of energy in the target region to leaked energy in the non-target region. Therefore, the weight distribution law under different angular domain conditions reflects the adaptive mechanism of the algorithm: the narrower the target angular domain, the more the optimized weighting tends to balance the aperture to enhance forward directivity; the wider the target angular domain, the more the optimized weighting tends to intensify edge attenuation to suppress energy beyond the target range. As a result, under various angular domain settings, the Rayleigh quotient optimization method can effectively focus the energy on the target angular domain, balance the mainlobe width and sidelobe level, and demonstrate a high degree of adaptability to application requirements and physical optimization significance (i.e., maximizing the output of acoustic energy in the desired direction).

3.3.2. Spherical Acoustic Field Distribution

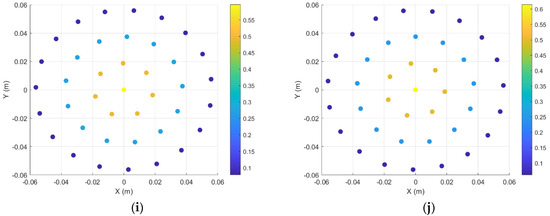

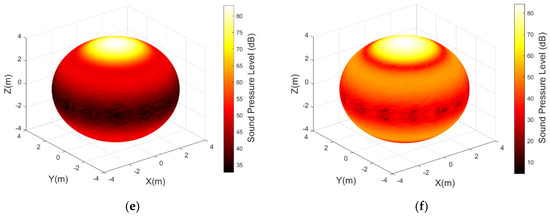

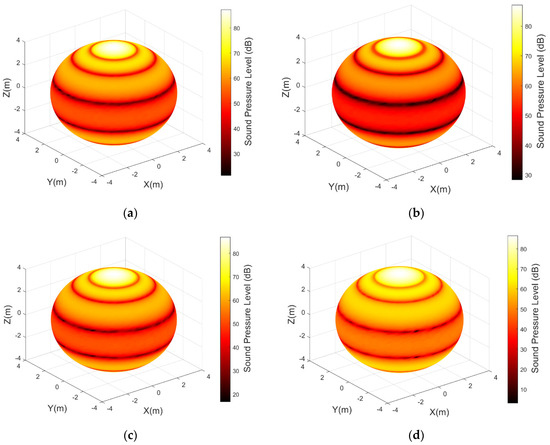

To evaluate the spatial energy concentration performance of the 2D circular ring array, the spherical acoustic field distributions of six classical weighting methods (Rectangular, Hanning, Hamming, Blackman, Dolph–Chebyshev, and Kaiser weighting) and the Rayleigh quotient (RQ) method were simulated. The array was placed in a finite element-based spherical acoustic domain to replicate the underwater free-field acoustic environment. The core parameters were consistent with those of previous tests. The spherical acoustic field distributions of the classical methods are shown in Figure 18, and the array radiation characteristics of the adaptive angular domain weighting method based on Rayleigh quotient eigenvalue optimization under different polar target angular domains are shown in Figure 19.

Figure 18.

(a) Sound field distribution in spherical acoustic domain with Rectangular weighting method; (b) sound field distribution in spherical acoustic domain with Hanning weighting method; (c) sound field distribution in spherical acoustic domain with Hamming weighting method; (d) sound field distribution in spherical acoustic domain with Blackman weighting method; (e) sound field distribution in spherical acoustic domain with Dolph–Chebyshev weighting method; (f) sound field distribution in spherical acoustic domain with Kaiser weighting method.

Figure 19.

(a) Sound field distribution in spherical acoustic domain of 5° angular domain optimized weighting method; (b) sound field distribution in spherical acoustic domain of 10° angular domain optimized weighting method; (c) sound field distribution in spherical acoustic domain of 15° angular domain optimized weighting method; (d) sound field distribution in spherical acoustic domain of 20° angular domain optimized weighting method; (e) sound field distribution in spherical acoustic domain of 25° angular domain optimized weighting method; (f) sound field distribution in spherical acoustic domain of 30° angular domain optimized weighting method; (g) sound field distribution in spherical acoustic domain of 40° angular domain optimized weighting method; (h) sound field distribution in spherical acoustic domain of 50° angular domain optimized weighting method; (i) sound field distribution in spherical acoustic domain of 60° angular domain optimized weighting method; (j) sound field distribution in spherical acoustic domain of 70° angular domain optimized weighting method.

As can be seen from Figure 18, these traditional fixed weighting methods all have shortcomings in directivity in the polar region direction: the mainlobes are generally relatively broad, and sidelobe energy leaks to larger angles, making it difficult to highly concentrate acoustic energy in the target polar region adjacent to the z-axis. A typical mainlobe–sidelobe performance trade-off is observed among different weighting methods. For example, Rectangular weighting has the narrowest mainlobe but the highest sidelobe level, while weightings such as Hamming and Blackman can reduce sidelobes but at the cost of broader mainlobes. Therefore, no matter which classical amplitude weighting is adopted, problems such as mainlobe broadening, sidelobe leakage, and energy dispersion are unavoidable in the radiated acoustic field in the polar region direction, making it difficult to achieve efficient acoustic energy concentration in the spherical polar region.

As shown in Figure 19, the adaptive angular domain weighting method based on Rayleigh quotient eigenvalue optimization proposed in this study adaptively adjusts the amplitude weights of each element according to the preset target polar region angular domain (a certain conical angle range around the z-axis). This enables the mainlobe to be strictly confined within the target angular domain and most of the acoustic energy to be concentrated in the z-axis direction. It can be seen from the Figure that the optimization algorithm can flexibly adjust the weight distribution regardless of whether the target polar region angular domain is narrow or wide: when the polar region angular domain required for focusing increases, the algorithm enhances the non-uniform weighting of element amplitudes (steeper edge tapering) to make the mainlobe cover a slightly larger polar range; when the target angular domain narrows appropriately, the weighting gradient is reduced accordingly to further narrow the mainlobe angular width. In the z-axis direction, the optimized mainlobe is significantly more concentrated, and sidelobes are suppressed outside the target angular domain, demonstrating excellent mainlobe control and energy concentration capabilities. Simulation results show that this Rayleigh quotient optimization weighting can increase the sound pressure level of the array in the target polar region, and the proportion of acoustic energy received in the polar region is higher than that of classical weighting methods. The physical meaning of its adaptive optimization mechanism lies in the following: by adjusting the excitation amplitude of elements, the coherent superposition of the sound field of each unit is enhanced in the target direction, and destructive interference occurs in non-target directions, thereby confining the radiated energy within the set angular domain. This mechanism conforms to the expected principle of array beamforming and fully proves the effectiveness of this method under the actual geometric model.

3.3.3. Acoustic Energy Radiation Efficiency Analysis

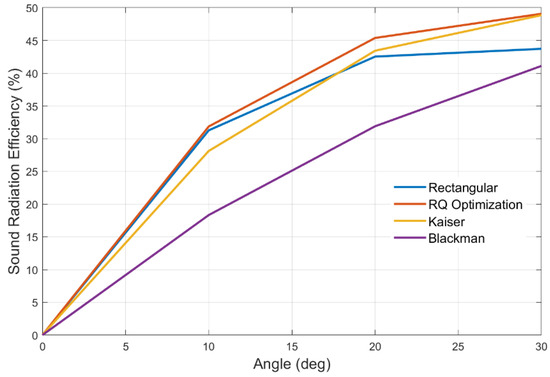

We separately plotted the acoustic energy radiation efficiency curves of the optimized weighting method and other weighting strategies in the 0–180° forward space and the 0–30° small angular cone, as shown in Figure 20. Here, “radiation efficiency” can be understood as the ratio of the acoustic power radiated by the array to the specified angular domain to the total radiated power, which is used to quantify the energy concentration capability of each weighting method in the target direction.

Figure 20.

Acoustic energy radiation efficiency comparison between RQ optimization method and classical weighting methods for 4-layer circular ring array.