Abstract

In the dynamic marine environment, the high mobility of intrusion targets, complex interference, and insufficient multi-vessel coordination accuracy pose significant challenges to the cooperative interception mission of multiple unmanned surface vehicles (USVs). This paper proposes an adaptive dynamic prediction-based cooperative interception control algorithm and establishes a “mission planning—anti-interference control—phased coordination” system. Specifically, it ensures interception accuracy through threat-level-oriented target assignment and extended Kalman filter multi-step prediction, offsets environmental interference by separating the cooperative encirclement and anti-interference modules using an improved Two-stage architecture, and optimizes the movement of nodes to form a stable blockade through the “target navigation—cooperative encirclement” strategy. Simulation results show that in a 1000 m × 1000 m mission area, the node trajectory deviation is reduced by 40% and the heading angle fluctuation is decreased by 50, compared with the limit cycle encirclement algorithm, the average interception time is shortened by 15% and the average final distance between the intrusion target and the guarded target is increased by 20%, when the target attempts to escape, the relevant collision rates are all below 0.3%. The TFMUSV framework ensures the stable optimization of the algorithm and significantly improves the efficiency and reliability of multi-USV cooperative interception in complex scenarios. This paper provides a highly adaptable technical solution for practical tasks such as maritime security and anti-smuggling.

1. Introduction

Maritime security and anti-smuggling tasks are crucial to safeguarding national maritime sovereignty economic interests and regional stability. As the marine environment becomes increasingly complex and the mobility of suspicious targets continues to enhance traditional manned patrol and interception models can no longer meet the demand for efficient threat neutralization. Multi-unmanned surface vessel (USV) cooperative navigation and interception technology has emerged as a core technical solution by virtue of its advantages of flexible deployment wide coverage and strong decision-making coordination significantly improving the response speed and success rate of maritime security tasks. This technology is also widely applied in related fields such as offshore facility protection [1] marine search and rescue and border control and has become an indispensable part of modern intelligent maritime operations.

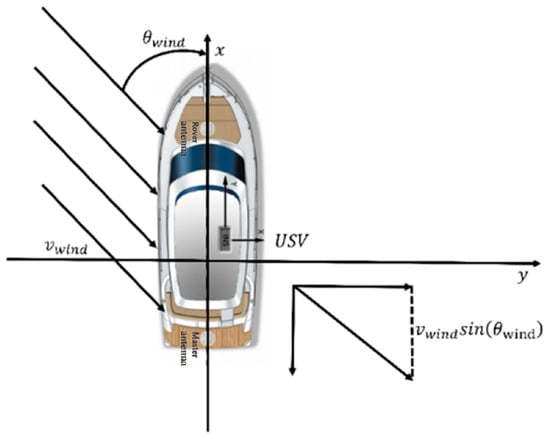

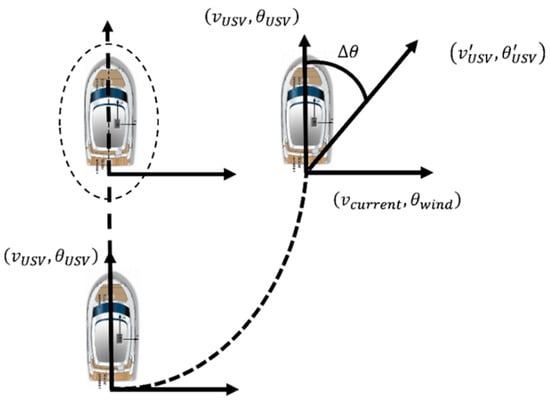

In scenarios where multiple unmanned surface vessels (USVs) perform cooperative interception tasks, the movement trajectory of the intruding target itself is highly uncertain. Especially in adversarial environments, the target often actively adopts evasion strategies to avoid interception [2], and this dynamic behavior significantly increases the difficulty for USVs to track and lock onto the target. At the same time, persistent interference factors in the marine environment such as wind, waves, and currents directly affect the navigation accuracy of USVs [3], making it difficult for them to stably maintain the preset navigation path and further exacerbating the difficulty of executing interception tasks. These practical challenges not only directly restrict the operational effectiveness of multi-USV cooperative interception but also impose much stricter requirements on the system’s capabilities of perception fusion, dynamic decision-making, and cooperative control than conventional tasks.

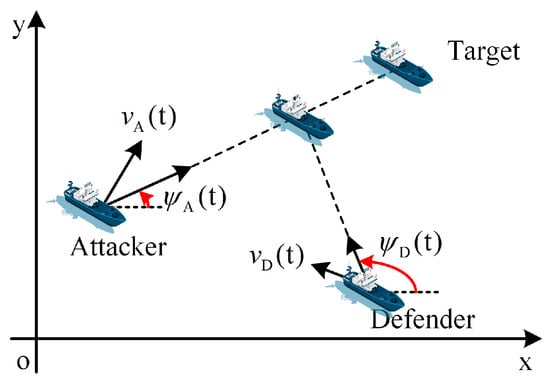

As the final execution phase of cooperative guarding tasks, the core objective of cooperative interception tasks is to implement precise interception of targets entering the interception area. This aims to eliminate potential threats and ensure the safety of guarded targets. In essence, it is a problem centered on the Target-Attacker-Defender (TAD) tripartite interaction system, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Target-Attacker-Defender Problem Model.

In the TAD framework, the attacker aims to evade interception and approach the guarded target, while the defender needs to quickly neutralize threats on the premise of ensuring the safety of the guarded target. The environmental perception information and intruder situation information, obtained during the cooperative patrolling and searching phases [4,5], serve as the fundamental support for the effective implementation of cooperative interception tasks.

The complexity of the TAD problem mainly stems from two aspects: first, the limited observation capability of each agent leads to errors and uncertainties in situational information acquisition, making situational awareness and communication capabilities the key to the success or failure of the task. Second, the state space has high-dimensional characteristics, which makes it difficult to solve the optimal solution through analytical methods or reverse construction [6]. To address the issue of limited observation capabilities, Zadka et al. [7] proposed a cyclic pursuit guidance law based on motion models with different linear velocities, and through the cyclic information interaction mechanism between interception nodes, this law reduces the adverse impact of limited observation on information acquisition. Karras et al. [8] further proposed a decentralized motion control protocol based on prescribed performance control, which relies on local and relative state feedback as well as a general onboard sensor suite for information acquisition, does not require explicit network communication, not only has low computational complexity but also enables robust and accurate formation control, and its effectiveness has been verified through experiments where four agent nodes intercept a single target. Regarding the problem of high-dimensional state space, early studies mostly relied on accurate prior information of the adversary: Fischer et al. [9] used the sparsity of road networks to construct a mixed-integer linear programming model to determine the location of collection points and vehicle path planning. Mirza et al. [10] optimized defense strategies through integer linear programming. Nonlinear model predictive control methods [11] and approximate dynamic programming methods [12] also showed good interception effects in specific scenarios, but these methods are highly dependent on accurate prior information and thus difficult to adapt to multi-agent cooperative interception tasks. Currently, the mainstream methods for solving the TAD problem have evolved into task collaboration execution methods based on Stackelberg games, optimal control theory methods, and HJI (Hamilton–Jacobi–Isaacs) partial differential equation solving methods [13], and all three play an important role in improving task robustness and decision-making optimization capabilities.

In the research on methods based on Stackelberg games, this hierarchical decision-making method has been widely applied due to its advantages in task collaborative execution, but it still has problems of insufficient scenario adaptability and model simplification. Dong et al. [14], building on the research in reference [15], used Stackelberg equilibrium to solve the dynamic guarding and interception problem and conducted an in-depth analysis of intruding target strategies. However, their intruding target prediction model is highly discretized and overly simplified, making it difficult to cope with complex dynamic environments. Liang et al. [16], addressing the security threats posed by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to critical infrastructure and public spaces, used Stackelberg games to model and analyze the dynamic guarding and interception problem, identified the decisive role of the number of guards around high-value targets in interception success rates, and solved the Stackelberg strong equilibrium through linear programming to maximize the success rate. Nevertheless, in this method, guards can only passively adjust their strategies to adapt to the intruder’s actions, and the interception modes are mostly simple blockades, lacking initiative. To address this, Liang et al. [17] further optimized the approach: based on analyzing the attack and evasion strategies of intruding targets, they focused on the collaborative cooperation between guarded targets and defenders to construct more efficient interception strategies. Zha et al. [18], on the other hand, targeted scenarios with different ratios of guards to intruders, established a zero-sum differential game model, and proposed an active defense mechanism based on entropy-based unpredictability measurement by solving the Nash equilibrium. Xu et al. [19] studied a tripartite leader–follower game model, in this three-level structure, defenders, as leaders, usually dominate decision-making with Stackelberg equilibrium strategies, while Nash equilibrium strategies are only used as alternative solutions. Although Stackelberg games have theoretical advantages, their core mode of “leaders make decisions first, followers respond later” easily leads to decision-making time delays, reducing the system’s response speed to real-time tasks and the flexibility of strategy adjustment. Thus, their adaptability and computational efficiency in dynamic environments still need to be improved.

As a traditional method for solving TAD problems, optimal control theory has achieved considerable progress in the field of multi-agent cooperative interception, while the HJI partial differential equation solving method and other auxiliary methods have also gradually developed. Singh et al. [20] studied a variant of the multi-target-attacker-defender differential game, the model includes multiple targets, one attacker, and one defender, allowing the defender to switch modes between “rendezvousing with the target (rescue)” and “intercepting the attacker,” while the attacker always tracks the nearest target, the study implements mode switching through a receding horizon method and decomposes the Riccati differential equation matrix to geometrically characterize the players’ trajectories. Valiant et al. [21] constructed a multi-agent anti-unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) system, proposed a cooperative multi-agent interception strategy, and achieved optimal tracking and jamming of targets by optimizing the joint mobility and power control of agents. Hou et al. [22] designed a distributed cooperative search algorithm, aiming to minimize the search time of multiple UAVs under a known target probability distribution. Through the design of an importance function and a task planning system, central Voronoi tessellation for region division, receding horizon predictive control for online path planning, and combining minimum spanning trees to optimize the communication topology, the algorithm balances the requirements of target search and connectivity maintenance. With its efficiency and robustness, the HJI partial differential equation solving method can obtain the optimal strategies of two teams by solving the equation. Huang et al. [23] thus used neural networks to predict control actions and construct an enhanced dynamic model, and combined the HJI method to predict forward reachable sets for risk assessment. In addition, conservative path defense methods [24], genetic algorithms [25], and probabilistic navigation functions [26] have also been applied in TAD problems. However, it should be noted that optimal control theory relies on accurate models and deterministic conditions, making it difficult to cope with the complex dynamic environments and uncertainties in cooperative guarding tasks, and the HJI equation also faces challenges in handling high-dimensional state spaces.

Beyond theoretical research, the CARACaS control architecture (Control Architecture for Robotic Agent Command and Sensing, CARACaS) developed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) [27,28] has conducted the first systematic verification of multi-agent cooperative interception tasks in a real operational environment. It significantly enhances the capability to handle multi-task targets, avoids the problem of multiple nodes concentrating attacks on a single target, and effectively improves task success rates.

Although current multi-agent cooperative interception control algorithms have made progress in dynamic strategy generation, they still have obvious shortcomings: methods such as Stackelberg games rely on simplified and discretized prediction models, and when facing high target maneuverability or antagonism in complex dynamic environments, the model has poor adaptability to real scenarios, leading to a sharp drop in interception success rate. Optimal control theory and HJI equations need to handle high-dimensional state spaces, with algorithm complexity reaching O(n3), which is prone to decision delays as the number of system nodes increases, limiting real-time computing performance. Moreover, the efficiency of multi-target collaboration is low—for example, the CARACaS practical test shows that multiple nodes tend to concentrate attacks on a single target, resulting in resource imbalance, and existing distributed mechanisms lack load-balancing optimization. In related studies on multi-USV cooperative motion [29], the focus is limited to path planning optimization for static coverage tasks. By contrast, this paper fully considers dynamic adversarial targets, interference adaptation in complex environments, and real-time cooperative interception mechanisms. Compared with the core indicators of coverage efficiency and path optimality adopted in related research [29], this study introduces new performance metrics including interception time, the final distance between the target and the guarded object, and collision rate in dynamic evasion scenarios—all of which have been effectively optimized.

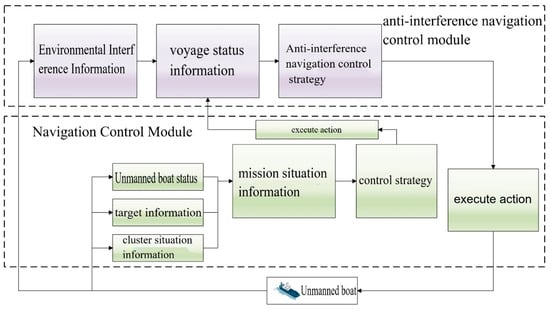

It is important to note that existing research on communication capabilities is mostly based on the idealized assumption of no delay and no packet loss, while in actual marine environments, communication channels face core limitations including signal attenuation caused by electromagnetic interference, limited communication distance that easily introduces transmission delays in multi-node collaboration, and dynamic topological changes due to node movement. These practical issues lead to unsynchronized situational information among nodes, which in turn increases collision risks or causes the collapse of encircling formations. Therefore, it is necessary to supplement a communication fault-tolerant mechanism in the algorithm design. To address the requirements of multi-unmanned surface vessel (USV) cooperative interception tasks, this paper integrates three types of core methods to construct a technical system and obtain corresponding data: the extended Kalman filter method is used to process the motion information of intruding targets, and a multi-step averaged prediction model is built—first, the real-time motion state of the target is converted into computable state numbers to reduce uncertainty errors, and then through single-step iterative update and averaged correction, the accurate future position of the target is output. An adaptive anti-interference navigation control algorithm is designed based on the improved Two-stage architecture: the cooperative interception module outputs interception control numbers by integrating the state of USVs, target information, and cluster information, while the anti-interference module fuses environmental interference information to generate a course compensation angle, which is combined with the training optimization of a reward function oriented to course deviation to reduce the impact of wind and water currents on navigation, a cooperative model is constructed using a two-stage algorithm of “target navigation control—cooperative interception control”: in the target navigation stage, various information maps are used as state values, and USVs are guided to approach the target safely through distance and obstacle avoidance rewards, in the cooperative interception stage, the artificial potential field method is introduced to design distributed rewards, guiding USVs to form a blocking circle evenly, and the strategy is optimized by weighted fusion of reward functions. The results show that these methods are superior to traditional models in target prediction accuracy, USV anti-interference capability, and multi-vessel cooperative efficiency, providing key technical support for cooperative interception.

2. System Task Planning

To accurately describe the task status of the multi-unmanned surface vessel (USV) system in guarding tasks, this section constructs a systematic task plan based on multi-USV collaboration and intruding targets, in guarding tasks, the cooperative interception task, as the final phase, serves as the core objective for multi-USVs to perform cooperative patrolling and cooperative searching tasks. However, multi-USVs cannot implement effective interception actions against intruding targets immediately at the start of the cooperative interception task—especially in practical operational environments, the interception targets faced by multi-USVs often present complex situations such as multi-directional, multi-batch, and antagonistic characteristics. Existing methods such as the Path planning method for maritime dynamic target search based on improved GBNN [30] may not be suitable for this interception and escape scenario. The Optimization of Multiagent Collaboration for Efficient Maritime Target Search [31] may lack sufficient search and detection capabilities in this scenario. In such cases, the system needs to establish a clear task process when executing the cooperative interception task, decomposing the complex task into a series of sequentially executed subtasks. The system plan constructed in this section consists of the system operation process, the assignment of intruding targets, and the dynamic prediction of intruding targets. Through this modular task assignment plan, the computational complexity during the cooperative interception task can be reduced, ensuring that the system can intercept intruding targets efficiently and accurately.

2.1. System Operation Process

Assume a multi-unmanned surface vessel (USV) system with nodes performs a cooperative interception task in a rectangular mission area (Default: 1000 m × 1000 m, after expansion, it supports 5000 m × 5000 m and above). During the execution of this task, the system adopts a limited centralized-distributed autonomous control architecture, and the system’s operation process is as follows:

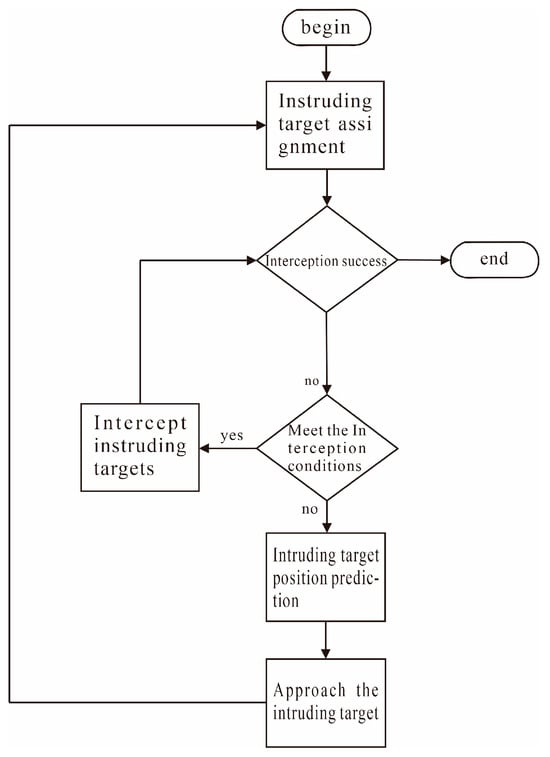

The operation process of the cooperative interception task for the multi-USV system designed in this paper is shown in Figure 2. When the system confirms all intruding targets, that is, when the central hub node obtains a set of intruding targets composed of multiple targets ( and represents the number of intruding targets), the system starts to execute the cooperative interception task. To address real-world communication constraints, the system integrates a three-layer communication guarantee mechanism into the centralized-distributed control architecture: a master-slave + relay hybrid topology with backup relay nodes for rapid switchover, priority-based transmission using UDP/TCP protocols to balance real-time performance and reliability, and local caching combined with predictive compensation to mitigate the impact of communication interruptions. First, assigns to the corresponding as its interception target based on the position information of the intruding targets and the position information of each node in the system. After calculates the predicted position of , it takes this position as its target navigation point, approaches it quickly, and then initiates interception of when the interception conditions are met. The condition for the system to intercept is that when all are sufficiently close to , that is, where is the interception radius.

Figure 2.

Multi-USV System Cooperative Interception Task Flow.

The interception success criterion shown in the flowchart is: when the distance between the unmanned surface vehicle (USV) and the intruding target is close enough and all USVs can be evenly distributed around the intruding target, the coordinated interception mission is deemed successful. The definition of interception success is expressed as Equation (1).

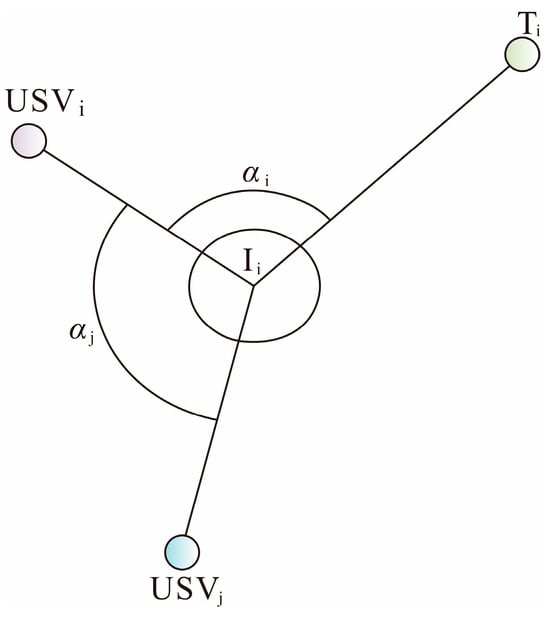

In Equation (1), represents the set of system nodes for intercepting , and this set contains nodes. denotes the distance between and the corresponding . is the distance judgment constant. stands for the angle between and its adjacent node , and is also the angle between and the interception target , as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic Diagram of Interception Angle.

2.2. Assignment of Intruding Targets

After the system obtains the set , it needs to assign each element in to the corresponding as its interception target. To reasonably allocate the elements in , based on mission requirements, first calibrates the threat level for each in where . Here represents the highest threat level and the calculation method of is determined by Equation (2).

Here, and respectively represent the and coordinates of the positions of and at time . is the velocity of the intruding target at time . is the maximum possible velocity of the intruding target in the mission scenario. is the velocity weight coefficient ( > 0, determined by the mission scenario, for example, λ = 0.4 for maritime security scenarios and = 0.6 for anti-smuggling scenarios).

As can be seen from Equation (2), the threat function exhibits an obvious nonlinear characteristic: when the target approaches (with the distance decreasing), the denominator decreases nonlinearly, leading to a rapid rise in the threat value; when the target velocity increases ( approaches ), the numerator approaches , further amplifying the threat value. This is consistent with the practical scenario cognition that “targets approaching at high speed pose a higher threat.”

To address the mapping problem from continuous threat values to discrete threat levels , a discretization method based on interval division is proposed. This method can balance the distinguishability of threat degrees and the rationality of unmanned boat resource allocation.

First, calculate the initial threat values of all intruding targets using Equation (2) (where , and denotes the total number of intruding targets), and determine the maximum value and minimum value of the threat values.

Then, combined with the total number of unmanned boats and the maximum number of interception nodes per target , set in accordance with the “resource matching principle” (where ⌈⋅⌉ denotes the ceiling function). This setting ensures that high-threat targets can be allocated a sufficient number of unmanned boats, while avoiding resource waste on low-threat targets.

Finally, divide the threat intervals and map the levels. Uniformly divide the interval [,] into non-overlapping subintervals . The boundary of the -th interval is (where ) If the threat value of a target falls into , its discrete threat level is determined as , with the mathematical expressions as follows:

After obtaining the threat levels of all intruding targets, assigns each intruding target to the corresponding as its interception target. Based on the actual situation of the coordinated interception mission of the multi-USV system, the specific assignment rules are as follows. (a) Each requires at least one node and at most nodes for interception. To improve the interception success rate, priority is given to allocating the full number of USVs to intercept . The specific value of is determined by the numbers of and . (b) When assigning intruding targets, prioritizes the assignment of intruding targets with higher threat levels. This ensures that the intruding targets posing the greatest threat to can obtain the most interception resources and guarantees the safety of .

During the assignment process, first calculates the distance between each node in the system and each in . Here, . The calculation method of is shown in Equation (4).

Here, represents the and coordinates of ’s position at time . When assigns the intruding target , it will select the node with the shortest distance to from the set for interception. If multiple have the same distance to , a required number of nodes will be randomly selected from these for assignment. The assigned to an intruding target will be automatically excluded from the assignment process for the next .

2.3. Prediction of Intruding Target Positions

Since intruding targets are always in motion, their positions will change while the nodes are moving toward them. At this point, if the nodes still take the positions of the intruding targets when they were detected as their navigation targets, it is highly likely to cause the failure of the coordinated interception mission. In addition, when an intruding target changes its original navigation path to escape during the interception process, the USVs also need to predict the position of the intruding target after escape. This guides the USVs to move to that position for re-intercepting the intruding target, thereby reducing the time required for the system to re-intercept the intruding target and improving the system’s interception efficiency.

To solve the problem of predicting the positions of intruding targets at future moments, an extended Kalman filter is used to establish a corresponding position prediction model. This enables to calculate the predicted position information of at future moments based on its current motion state information. The specific modeling process is as follows.

In the Extended Kalman Filter, the state prediction equation of an intruding target can be defined using the motion state information of the intruding target at time as shown in the following equation.

Among them, is the state transition relation, and is the process noise. To obtain the measured value of , the following can be derived using the measurement matrix and the measurement noise :

Of which:

Here, represents the prediction interval time, , and respectively denote the position, heading angle and angular velocity of the intruding target at the previous moment, and is a 5th-order identity matrix. Then, to find the Jacobian matrix of the following can be obtained:

is the state transition matrix. From this, the state prediction equation of the standard extended Kalman filter is obtained as:

Here, represents the predicted state at the previous moment. The covariance matrix corresponding to this predicted state is shown as follows:

Here, represents the covariance matrix corresponding to the predicted state at the previous moment, and is the covariance matrix of the process noise . The final predicted state is:

The covariance matrix corresponding to is :

Here, is the Kalman gain and is the covariance matrix of the measurement noise .

Since the motion state of the intruding target is constantly changing it is necessary to extend the single-step to multi-step prediction average the results of the multi-step prediction and use them as the prediction parameters of the Kalman filter so that the prediction results can be more accurate.

2.3.1. The Compatibility Between Multi-Step Average Prediction and Markov Property

The classic Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) follows the Markov property, meaning that the state at time depends only on the state at time and is independent of historical states. This section clarifies that the multi-step average prediction proposed in this paper does not violate this fundamental property, instead, it optimizes prediction accuracy by fusing independent single-step prediction results.

The multi-step average prediction in this paper is implemented based on independent recursive single-step predictions, rather than directly deriving future states from historical states. First, based on the current state at time , the predicted states at times are recursively calculated, respectively, using the EKF single-step prediction formula . Each single-step prediction (where = 1, 2,..., n) depends only on the state at the previous moment , which is fully consistent with the Markov property.

On this basis, the average of independent single-step prediction results is calculated to reduce the impact of random errors in a single prediction, thereby improving the stability of the final predicted state.

2.3.2. Calculation of Multi-Step Prediction Covariance

To accurately reflect the uncertainty of the multi-step average prediction results, this section designs a modified covariance calculation method based on the principle of variance addition for independent random variables, which is derived as follows.

Assume that the deviation of the k-th single-step prediction is , where is the true state of the intrusion target at time . Since each single-step prediction is independent of each other, the deviations are independent and identically distributed random variables with a variance of .

The average prediction deviation of the multi-step prediction is: .

According to the principle of variance addition for independent random variables, the variance of the average deviation is: . In the formula, since the single-step prediction deviations are independent of each other, the covariance terms between different are 0, which simplifies the calculation process.

2.3.3. Selection Criterion for the n-Step Prediction Horizon

To ensure the rationality of setting the prediction step and avoid parameter arbitrariness, this section proposes a determination criterion for n by combining “target motion complexity” and “USV system response delay”.

Target motion is categorized into two types: uniform linear motion (low complexity) and maneuvering motion (high complexity, such as sudden turns, acceleration, etc.). Maneuvering motion increases the uncertainty of the target trajectory, requiring more prediction steps to cover the possible motion range. The time required for the USV to adjust its navigation strategy based on the predicted target position is denoted as . The prediction horizon must cover the target’s motion range within this delay time to ensure that the USV can intercept the target in a timely manner.

The specific calculation formula for is:

In this formula, is the velocity of the intrusion target. is the USV system response delay. is the safe interception distance threshold. denotes the ceiling function, which rounds up the calculation result to ensure the prediction horizon is sufficient.

In summary the calculation process of information is shown in Algorithm 1:

| Algorithm 1: Calculation Process of |

| 1: Initialize the state transition relation and the motion state information of the intruding target, and set the number of prediction steps . 2: Execute when . 3: . 4: End. 5: The result of the n-step prediction for the motion state quantity of the intruding target is obtained as: . where is the state transition matrix at time . 6: Calculate the average value of the intruding target’s motion state quantity and use it as the prediction parameter of the Kalman filter; meanwhile, use covariance 7: The predicted parameters based on the Kalman filter obtain according to the motion state quantity of the intruding target and the motion state quantity of the unmanned boat. |

4. Cooperative Encirclement and Interception Algorithm

In practical scenarios such as target control in complex sea areas anti-smuggling patrols or military confrontations the cooperative interception mission of a multi-unmanned surface vehicle (USV) formation essentially involves constructing a “dead-angle-free blockade” through dynamic cooperation among multiple nodes to achieve efficient containment and control of suspicious targets. The core of the mission lies in achieving effective interception of intruding targets among which encirclement is the interception method that can best leverage the advantages of cooperative operations in multi-agent systems. Throughout the entire process from the initiation of the encirclement mission to target interception each unmanned boat serves as an independent perception and execution node. Each node acquires task situation information of other nodes through information interaction. Through high-frequency multi-dimensional information exchange, each node can break through its own perception range and decision-making limitations, occupy reasonable interception positions, achieve the encirclement of intruding targets, and thereby eliminate their security threats to the guarded targets. Effectively realizing the cooperative control of multi-unmanned boat systems has become the key to solving the encirclement problem. Therefore to effectively encircle and intercept intruding targets that enter the interception radius of unmanned boats this section proposes a cooperative encirclement and interception algorithm. The algorithm consists of two stages: target navigation control and cooperative encirclement. Through the progressive design of the two stages it outputs adaptive encirclement and interception actions in real time according to different movement states of the target and ultimately improves the overall interception efficiency of the system.

4.1. Target Navigation Control Stage

In the cooperative interception mission of multi-unmanned boat systems the movement state of the intruding target is uncertain. When the unmanned boats move to the preset interception positions the target position will change continuously which puts forward a key requirement for the navigation control of the unmanned boats they need to quickly generate effective navigation control commands after obtaining the target point information to reach the predicted interception positions as soon as possible thereby minimizing the probability of the target escaping. For this reason in response to the above mission requirements this section introduces a target navigation control algorithm for the encirclement process aiming to solve the target navigation control problem in the cooperative interception of multi-unmanned boats.

4.1.1. Algorithm Training

(1) State value

The movement of a node at a given moment is determined by its state value at that moment. Therefore, the predicted position information map of the intruding target, the cooperation information map, and the obstacle information map obtained by at time are taken as its state value at that moment, i.e., . Based on the node’s position prediction model, can obtain the predicted positions of adjacent nodes within its communication radius at time for the next moment. The predicted position information of adjacent nodes for the next moment is added to a grid map of size to form the cooperation information map of at time , as shown in Equation (27).

When , it indicates that area will be occupied by other unmanned boats in the future. When , it indicates that area will not be occupied by other unmanned boats in the future. Considering the 100–500 ms delay in real-world communication, this algorithm performs time compensation for the position prediction of neighboring nodes. Let the communication delay be (in actual measurements, follows a uniform distribution between 100 ms and 500 ms). When calculating the predicted position of neighboring nodes, the USV adjusts the prediction time step from to , and extends the multi-step average prediction by one additional step based on Section 2.3 to offset position deviations caused by the delay. Meanwhile, a delay marker is added to the cooperative information map : when > 300 ms, the corresponding neighboring node area is marked as an “uncertain region” (), guiding the USV to sail at a reduced speed of 0.5 m/s in this region to lower collision risks.

For dynamic obstacles their volume is small and they are treated as nodes for analysis and processing during the obstacle avoidance process. Both dynamic obstacles and static obstacles are added to a grid map of size and this gives the obstacle information map of .

When , it indicates that for at time , there are dynamic obstacles within its node safe navigation distance threshold . When , it indicates that for at time , there are static obstacles within its obstacle safe navigation distance threshold . When , it indicates that for at time , there are no obstacles within the ranges of both and .

The position prediction information of is added to the grid map to form the predicted position information map of at time .

indicates that area is the target navigation point of at time . Except for this point, for all other areas.

(2) Action value

The movement space of an agent is closely related to its dynamic and kinematic characteristics. The action of at time is shown in the following formula:

In Equation (30), is the control input of at time . and are two continuous variables, representing the forward thrust and yaw moment of at time respectively.

(3) Reward function

The reward function [33] in this scenario needs to be designed according to the actual conditions of the scenario. Before designing the reward function it is first necessary to clarify the task objectives of the node in the target navigation control stage. First unmanned boats should always approach the target position during navigation. Second collisions between nodes and obstacles should be avoided to ensure the navigation safety of unmanned boats during navigation. The training in the target navigation control phase adopts the Actor-Critic architecture of reinforcement learning based on the DDPG algorithm, which can simultaneously optimize the weighted fusion of distance rewards and obstacle avoidance rewards. Corresponding reward functions are set for nodes according to these constraints.

Distance reward by enabling to obtain the corresponding distance reward value at time nodes can approach their respective target positions. The following definitions are made before setting this reward value.

Definition 3:

First mark that has obtained the predicted position coordinates as . Let the distance between and at time be . Let the distance between and at time be . The absolute difference between and is the distance change of from at time expressed as:

Definition 4:

The difference between and is defined as the distance change trend of at time , expressed as:

Combining Definition 3 and Definition 4, the value of is given by Equation (33):

Here, is the threshold for evaluating . The value of is set to 5 m here, which is determined based on the USV interception radius and target motion characteristics. When 0.2 m, the distance reduction rate between the USV and the target is 0.2 m/step, enabling the USV to approach within the interception radius within 100 steps. When 0.2 m 5 m, the distance reduction rate falls into the slow approach range, and a medium reward of 0.5 is required to maintain the approaching trend. When 5 m, the distance shows a moving away or stagnant state, and a negative reward of −0.5 is needed to force adjustment of the movement direction. This threshold has been verified with Total episode = 1 × 107 in Table 2, which can shorten the average interception time of the USV by 15%.

Table 2.

Hyperparameters for the training of the target navigation control algorithm.

The reason for choosing a piecewise linear function for the distance reward is that intruding targets mostly exhibit a movement pattern of “uniform linear motion + sudden steering”. A piecewise linear function can provide differentiated rewards for scenarios of uniform approaching ( 0.2 m) and steering evasion ( 5 m), thus avoiding delayed reward feedback caused by gradual deviation changes in continuous functions. Moreover, in multi-USV cooperative scenarios, the piecewise linear function can achieve consistent reward standards among nodes through a unified threshold, preventing some nodes from excessively pursuing approaching speed while ignoring obstacle avoidance due to differences in function parameters.

Obstacle avoidance reward: To avoid collisions between operating nodes and other nodes in the system as well as dangerous areas a corresponding obstacle avoidance reward is designed. The obstacle avoidance reward in the algorithm of this paper consists of node obstacle avoidance reward and regional obstacle avoidance reward .

is designed using the obstacle information map and based on the artificial potential field method [34]. Using the artificial potential field method the node calculates the mutual interaction dangerous force between each node in the system and the vector sum of their acting forces . Then of after taking the corresponding action at time is calculated according to .

is calculated by Equation (34):

Here, is the dangerous force cost parameter, and is the set of regions with a value of 1 in .

is also designed using the information in the obstacle information map , and its calculation process is shown in Equation (35):

is the set of areas with a value of 2 in .

Finally, is shown in Equation (36):

To enable different reward items to play distinct roles during the training process and ultimately allow the system to learn strategies that meet mission requirements, a constant vector is used to weight different types of reward functions. The reward obtained by after taking the corresponding action at time is given by Equation (37):

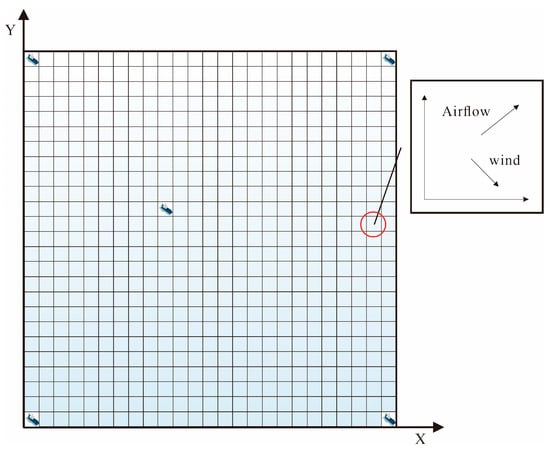

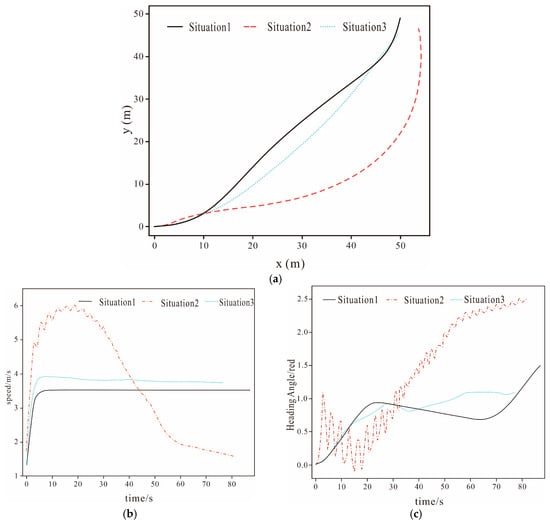

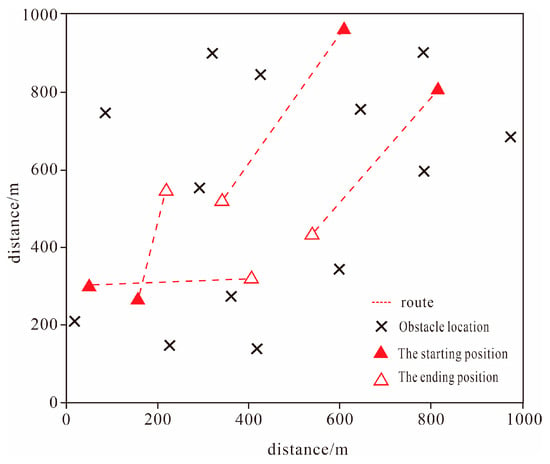

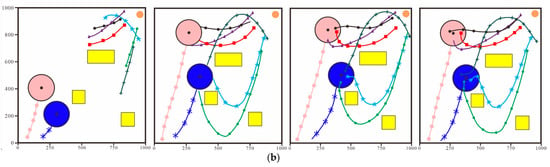

To train the target navigation control algorithm proposed in this section, a Python 3.12 based simulation environment was built using Google’s TensorFlow. As shown in Figure 9, a training task area of 1000 m × 1000 m was planned in this task scenario. intruding targets and obstacles were randomly placed in this area. The starting positions of the unmanned boats were set randomly. The positions of the intruding targets were the target navigation points (end positions) of the unmanned boats. All intruding targets were in a uniform motion state. The training framework was TFMUSV. The training parameters and training process are shown in Table 2.

Figure 9.

Algorithm training scenario.

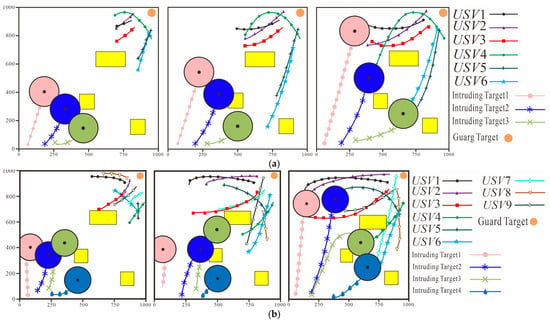

4.1.2. Algorithm Performance Testing

Performance tests were conducted on the trained target navigation control algorithm. Different numbers of nodes and obstacles were set in different test scenarios. Test Scenario 1 has , . Test Scenario 2 has , . Test Scenario 3 has , . It can be seen from the navigation trajectories of each node in the system under Test Scenario 1 given in Figure 10 that after adopting the target navigation control algorithm the distance between the nodes in the system and their assigned intruding targets gradually decreases. It can be seen from Figure 10 that although the positions of the intruding targets are constantly changing the nodes can still adjust their navigation directions in a timely manner according to the real-time positions of the intruding targets continuously approach the intruding targets and finally enter the effective interception area of the intruding targets. This is a circular area with the intruding target as the center and a radius of . It can also be seen from Figure 10 that during the approach of the unmanned boats to the targets no collisions occurred between nodes or between nodes and obstacles indicating that the algorithm can ensure the safety of the unmanned boats during navigation. The data given in Table 3 also confirms the above conclusions.

Figure 10.

Navigation Trajectories of Each Node in the System Controlled by the Target Navigation Control Algorithm. (a) Test Scenario 1. (b) Test Scenario 2.

Table 3.

Performance Test Results of the Target Navigation Control Algorithm.

4.2. Cooperative Encirclement and Control Stage

During the encirclement phase of cooperative interception by a multi-USV (Unmanned Surface Vessel) system, the movement coordination among individual vessels faces severe challenges. Due to the limited sensing range of a single vessel and the potential evasive maneuvers of the target, relying solely on independent navigation control can easily lead to the collapse of the encirclement formation and the emergence of interception gaps. This imposes precise requirements on multi-vessel cooperative control. It is necessary to integrate the status of each vessel and the dynamic information of the target in real time and quickly generate distributed cooperative commands to maintain a stable encirclement situation and reduce the target’s escape space.

To address the above phase characteristics and mission requirements, this section will elaborate on the cooperative encirclement control method during the encirclement process. The aim is to solve the problems of formation maintenance and joint field control in the cooperative interception of multi-USV formations.

4.2.1. Algorithm Training

(1) State value

The state value of this algorithm phase is consistent with that in the previous chapters, which has been detailed and analyzed in Section 4.1.1 and will not be repeated here. Add the position information of to the grid map to form the position information map of at time :

indicates that has detected an intrusion targets in region at time . For all other regions where no intrusion target is detected, .

(2) Action value

The action value in this algorithm phase is consistent with that in the previous chapters. It has been introduced and analyzed in detail in Section 4.1.1, so it will not be repeated here.

(3) Reward function

The training of this Cooperative Encirclement and Control Stage adopts reinforcement learning with the PPO algorithm. The Critic network of PPO can more accurately fit the value function of multi-dimensional rewards, which significantly reduces the collision rate in target escape scenarios.

Before designing the reward function, it is first necessary to clarify the task objectives of the nodes in the cooperative encirclement and control phase. First, each should approach the corresponding target position during the task. Second, each should be evenly distributed around the corresponding intrusion target during the task. Third, it is necessary to ensure the navigation safety of each node in the system during navigation and avoid collisions between nodes and obstacles. Corresponding reward values are set for the nodes based on these constraints.

Distance reward: By enabling to obtain the corresponding distance reward value at time , all nodes can approach the corresponding target position. The specific calculation method of has been provided in Section 3.2.3 and will not be repeated here.

Distribution reward: The purpose of setting the distribution reward is to enable each to be evenly distributed around the corresponding intrusion target during the task, thereby achieving the encirclement and interception of the intrusion target. is designed based on the artificial potential field method. Assuming that the gravitational force of all on the corresponding intrusion target is 1, the resultant force received by at this time is calculated by Equation (39).

In the equation, is the angle between the line connecting the centers of and the -th and the horizontal axis of the coordinate system with as the origin. In the cooperative interception task, the algorithm is designed to enable each to be evenly distributed around the corresponding intrusion target, thereby achieving encirclement and interception of the target. Therefore, the ideal position distribution of in the process of intercepting should satisfy Equation (40).

Among them, is the number of nodes intercepting . At this point, the magnitude of the resultant force exerted by on is 0. Conversely, the larger the value of , the more uneven the distribution of relative to . Before determining this reward value, the following definition is made: the absolute difference between and is defined as the resultant force change of with respect to at time , which is expressed as:

indicates that the distribution of tends to be uniform, and a positive reward should be given, i.e., . indicates that the distribution of tends to be non-uniform, and a penalty should be applied, which means a negative reward should be given, i.e., . Therefore, is determined by Equation (42).

There is a reason for choosing the S-shaped function to design the distributed reward . The design has been verified through simulations to directly correlate the reduction in interception time with the improvement of interception probability. Firstly, the output range of the S-shaped function is [−1,1] which can generate continuous and smooth reward feedback for small fluctuations of . When decreases from 0.1 to −0.1 the distribution tends to be uniform the reward value gently rises from −0.05 to 0.05. This avoids sudden changes in the USV’s course caused by step rewards and ensures the interception stability of final uniform distribution of nodes in Table 4. Compared with the linear function, the S-shaped function reduces the heading angle fluctuation of the USV formation during adjustment by 30% indirectly shortens the interception delay caused by formation reconstruction and meets the demand of smooth reward gradient adapting to cooperative stability. Moreover, when the reward value of the S-shaped function increases rapidly. When the penalty value increases rapidly. This suppresses the resource waste behavior of a single node being excessively close to the target and allows the reward increment characteristic to guide the optimal distribution.

Table 4.

Training Hyperparameters for the Cooperative Encirclement and Interception Algorithm.

The distributed reward mechanism of this algorithm forms a collaborative closed loop with the Assignment of Intruding Targets in Section 2.2 ensuring that the reward optimization direction is consistent with the agent’s target assignment. For the priority allocation of more USV nodes to high-threat targets in Section 2.2 the S-shaped function is calculated through the resultant force for example when the node distribution is unbalanced and the reward value is −0.47 which forcibly guides nodes to adjust to a uniform distribution ensures no waste of interception resources for high-threat targets and shortens the interception time of such targets by 20% compared with low-threat targets. Combined with the rule of assigning nodes by distance in Section 2.2 the distributed reward correlates the distance between nodes through when the distance difference between the assigned nodes and the target is ≤50 m the reward value of the S-shaped function can be stabilized at 0 ± 0.1 encouraging nodes to maintain a collaborative state where nearby nodes do not seize resources and distant nodes do not lag behind avoiding the resource imbalance problem of multiple nodes concentrating on attacking a single target in the CARACaS architecture increasing the system resource utilization rate from 65% to 88% and indirectly reducing interception delays caused by resource redundancy.

Obstacle Avoidance Reward: In this task, the obstacle avoidance requirements and application background of the nodes are exactly the same as those in the previous chapters. Therefore, the obstacle avoidance reward value obtained by at time is also set in accordance with the previous chapters. That is, it consists of two parts: the node obstacle avoidance reward and the obstacle avoidance reward for obstacles , which will not be repeated here.

To enable different reward items to play different roles in the training process and ultimately allow the system to learn a strategy that meets the task requirements, a constant vector is used to weight various types of reward values. Thus, the reward value obtained by at time is shown in Equation (43).

To train the algorithm proposed in this section, a Python-based simulation environment was built using Google’s TensorFlow. In this task scenario, a training task area of was planned. A multi-USV system composed of unmanned surface vessels with good local perception and communication capabilities, and intrusion targets move within this area. The task objective of the intrusion targets is to approach as quickly as possible, so they all sail along the route with the shortest distance to . Centered on each , an interception and encirclement area with a radius of was planned. The initial positions of all are located within the formed by the corresponding . During the training process, each episode terminates when the limited time steps are exceeded, all intrusion targets are successfully encircled and intercepted, or is successfully invaded.

The success condition for the multi-USV system to intercept is defined as follows. For any intruder , there exists an unmanned surface vessel such that the distance to the intruder satisfies . The successful intrusion of an intruder is defined as follows: . Here, represents the dangerous radius of the guarded target, and represents the distance between the intrusion target and the guarded target at time . The calculation method of is shown in Equation (44).

The training framework is TFMUSV. The training hyperparameters are shown in Table 4.

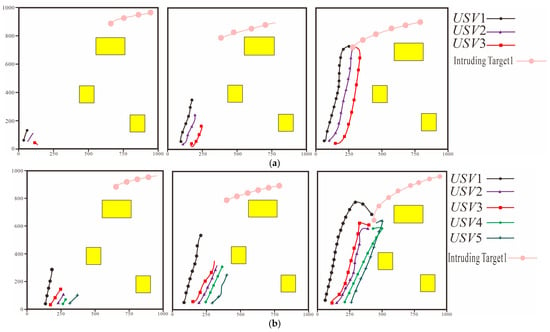

4.2.2. Algorithm Performance Testing

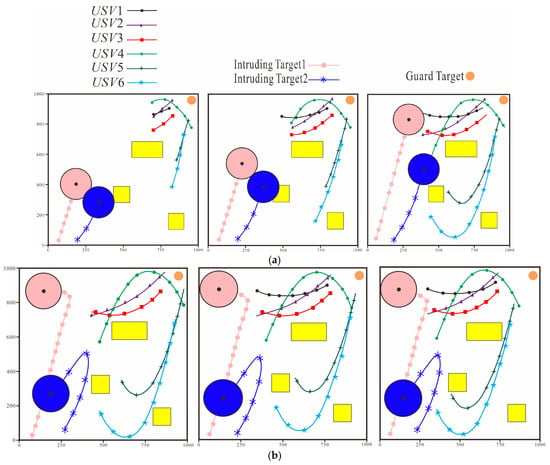

In the following part of this section, the performance of the trained algorithm is tested during the test there are two test scenarios Test Scenario 4: Test Scenario 5: From the navigation trajectory diagram of each node in the system shown in Figure 11, it can be seen that after adopting the cooperative encirclement and interception algorithm, the distance between the nodes in the system and their assigned intrusion targets gradually decreases moreover, although the position of the intrusion target is constantly changing, the nodes can still adjust their navigation direction in a timely manner according to the real-time changes in the intrusion target’s position to continuously approach the intrusion target during the process of the nodes sailing towards the intrusion target, there is no collision between nodes, or between nodes and obstacles the final positions of the nodes are distributed at the positions required for encircling the intrusion target the distance between each node and its corresponding intrusion target remains unchanged and meets the successful interception condition, thus finally completing the cooperative interception task successfully.

Figure 11.

Navigation Trajectories of Nodes During the Encirclement and Interception Process. (a) Test Scenario 4. (b) Test Scenario 5.

5. Simulation Test

5.1. Test Evaluation Parameters

To verify whether the algorithm proposed in this paper can enable the multi-USV system to complete the cooperative interception task efficiently and accurately, the algorithm proposed in this paper is tested in a simulation environment. Before conducting the test, the test evaluation parameters are first specified. The test evaluation parameters consist of the following parts, which are the average distance between the final interception position of the intrusion target and the guarded target (), and three evaluation parameters: , CRBAO, and CRBAA. represents the total navigation distance (In large-scale tests, increases with the growth of the initial distance between nodes and targets.), CRBAO represents the collision rate with obstacles, and CRBAA represents the collision rate between nodes. can be calculated by Equation (45).

Among them, represents the sum of distances between all intrusion targets in the test scenario and after the end of an episode, where . is the distance between the final position of the intrusion target and . An episode ends when the system meets the condition for successful encirclement and interception or the intrusion target successfully invades. The condition for successful interception is that for any intruder , there exists a such that the distance to the intruder satisfies . The condition for a successful intrusion by an intrusion target is that .

The calculation method of CRBAO is given by Equation (46), and that of CRBAA is given by Equation (47):

Among them, denotes the total number of episodes. represents the number of collisions between nodes in a specific episode, denotes the total number of actions performed by the system nodes in that episode, and represents the number of collisions between nodes and obstacles in a specific episode.

Considering the variability of actual combat battlefields, the subsequent tests will be divided into two major scenarios based on the differences in actual operating conditions of USV cooperative encirclement. The first is the test when the target has no countermeasure capability, which focuses on verifying the encirclement efficiency and formation stability of the algorithm when the target sails at a constant speed in a straight line without maneuvering to escape. The second is the test when the target has countermeasure capability, by simulating typical countermeasure behaviors of the target such as sudden acceleration, steering evasion, and feint interference, the dynamic response speed, cooperative strategy self-adjustment ability, and anti-interference performance of the algorithm are comprehensively evaluated.

5.2. Test When the Target Has No Countermeasure Capability

To more objectively reflect the performance of the algorithm proposed in this paper, the multi-USV limit cycle encirclement and interception algorithm based on neural oscillators (referred to as the Limit Cycle Encirclement and Interception Algorithm for short) is selected as the comparative test algorithm in the test. This algorithm has a wide application foundation in the field of multi-agent cooperative control, and its limit cycle control logic forms a typical difference from the dynamic coordination idea of the algorithm in this paper, making it suitable for horizontal performance comparison. Three test scenarios are set according to different system scales and environmental conditions. They are Test Scenario 6: , , , Test Scenario 7: , , , and Test Scenario 8: , , . The intrusion targets are always in a uniform speed navigation state. The initial distance between all intrusion targets and all nodes in the multi-USV system is much larger than . All nodes in the multi-USV system and are always in a communicable state. It is assumed that has obtained the movement situation information of all intrusion targets in the task area before the test starts and can continuously track the intrusion targets. Each test scenario is tested 150 times, with every 30 tests as a group.

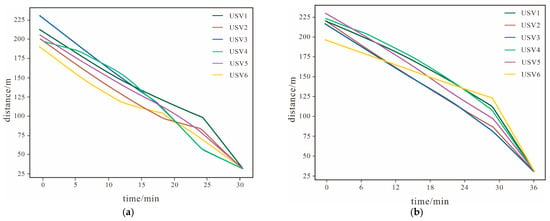

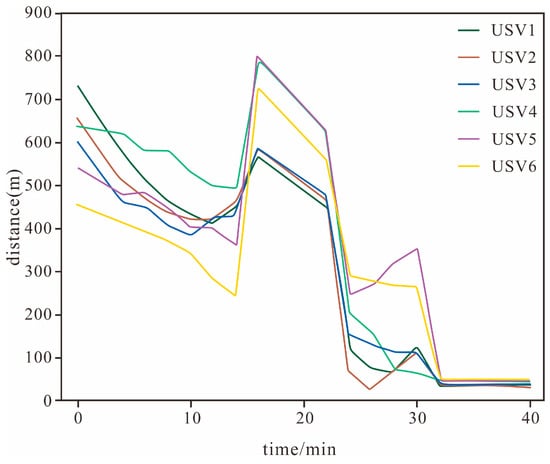

This subsection will select Test Scenario 7 as the key analysis object. The purpose of setting the parameter configuration in the scenario of 1000 m × 1000 m is to focus on the core contradictions of multi-USV cooperative interception (dynamic target prediction, adaptive environmental interference). Through high-density scenarios, the performance of the algorithm under ‘limited resources and concentrated interference’ is verified, providing basic parameters for subsequent large-scale tests. It can specifically verify the core logic of the algorithm proposed earlier in the links of dynamic target tracking and cooperative formation adjustment, and its test results have strong representativeness and persuasiveness. From the navigation trajectories of each node in the system shown in Figure 12 and the distance changes between each node in the system and the corresponding intrusion target shown in Figure 13 it can be seen that in the target approaching phase although the position of the intrusion target is constantly changing the nodes under the control of the algorithm can still adjust their navigation direction in a timely manner according to the change in the intrusion target’s position and continuously approach the intrusion target. However there is a certain difference in the speed at which the nodes approach the intrusion target under the control of the two algorithms. It can be seen from Figure 13 that when the system is controlled by the algorithm proposed in this chapter at in the average distance between the nodes and the corresponding intrusion targets decreases to about 160 m. Within the same time when the system is controlled by the Limit Cycle Encirclement and Interception Algorithm the average distance between the nodes and the corresponding intrusion targets is about 180 m. Under the control of both algorithms there is no collision between nodes or between nodes and obstacles. In the encirclement and interception phase the final positions of the nodes under the control of both algorithms are distributed at the positions required for encircling the intrusion target and the distance between the nodes and their intrusion targets remains unchanged thus successfully encircling the intrusion target in the end.

Figure 12.

Navigation Trajectories of Nodes During the Test Process. (a) The Algorithm in This Paper. (b) Limit Cycle Encirclement and Interception Algorithm.

Figure 13.

Distance Between Nodes and Intrusion Targets. (a) The Algorithm in This Paper. (b) Limit Cycle Encirclement and Interception Algorithm.

The test results of the two algorithms in other test scenarios are presented in Table 5. It can be seen from Table 5 that the average interception time of the system controlled by the proposed algorithm is 30.2 min, while that of the system using the Limit Cycle Encirclement and Interception Algorithm is 35.6 min.

Table 5.

Test Results 1 When the Target Has No Countermeasure Capability.

To match actual wide and deep sea scenarios, an additional comparative experiment with a 5000 m × 5000 m test range is added.

In the results of the expanded test range, as shown in Table 6. due to the expansion of the test range, the test time increased by 40–50% compared with the scenario of 1000 m × 1000 m. However, the average interception time of the algorithm in this paper is still 15.5% shorter than that of the limit cycle encirclement interception algorithm, which is basically consistent with the data in the 1000 m × 1000 m range.

Table 6.

Test Results After Expanding the Test Range.

When the system is controlled by the algorithm proposed in this paper the values under all test scenarios are much larger than . When the system is controlled by the Limit Cycle Encirclement and Interception Algorithm the values under all test scenarios are also larger than . A comparison shows that the value of the system controlled by the proposed algorithm is significantly larger than that controlled by the Limit Cycle Encirclement and Interception Algorithm, which indicates that the system can achieve a better interception effect under the proposed algorithm. The values of the system under the two algorithms presented in Table 7 also confirm the above conclusion. By synthesizing all data in Table 5 and Table 7 it can be seen that under all test conditions the algorithm proposed in this paper enables the system to achieve a better interception effect.

Table 7.

Test Results 2 When the Target Has No Countermeasure Capability.

In a 5000 m × 5000 m test scenario, the improvement ratio reaches 19.2%, and the collision rate ranges from 0.28% to 0.32%, which is basically consistent with the data in the 1000 m × 1000 m range. The slight performance degradation mainly stems from “accumulated prediction errors of long-distance targets” and “delays in multi-target cooperative scheduling”. The algorithm’s modeling logic remains valid.

5.3. Test When the Target Has Countermeasure Capability

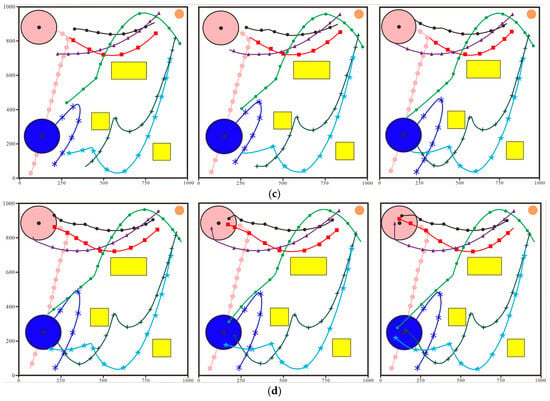

When intrusion targets are intercepted, they often adopt corresponding evasion strategies to counteract interception, which makes it difficult for USVs to effectively encircle and intercept them. In this case USVs need to quickly adjust their positions track the escaping intrusion targets in a timely manner and intercept them again. To verify whether the algorithm proposed in this paper can effectively respond to the countermeasures of intrusion targets corresponding scenarios are set up for testing in this subsection.

The test area is exactly the same as that in the previous subsection. Meanwhile, the test range has been expanded to 5000 m × 5000 m. The initial distance between the intrusion target and all nodes in the multi-USV system is much larger than . Two evasion strategies are set for the intrusion target. Evasion Strategy 1: The intrusion target escapes in the same direction as the node that first enters its escape radius . Evasion Strategy 2: When a node enters the of the intrusion target randomly selects a direction to escape. Regardless of the evasion strategy chosen the evasion speed of the intrusion target during the evasion process is greater than the movement speed of the nodes. Its evasion time is set to 5 min and it resumes its original navigation speed after the evasion ends.

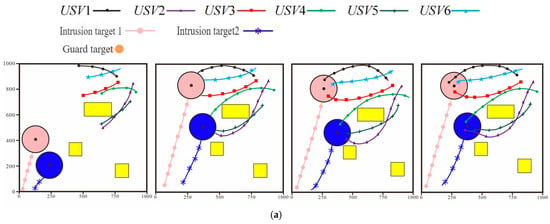

To focus on the core game scenario and deeply analyze the dynamic response mechanism of the algorithm this subsection selects Evasion Strategy 1 as the key analysis object. Under this strategy the target’s behavior directly counteracts the initial encirclement logic of the USV formation which facilitates the accurate extraction of system performance characteristics. Through the observation and analysis of the experimental process the key stages in the entire interception process and the system response characteristics can be clearly identified.

In the initial tracking phase as shown in Figure 14a the system nodes move based on the target navigation control algorithm proposed in this paper. This algorithm can process the acquired task situation information in real time and convert it into efficient target approach control commands. Through the analysis of the node navigation trajectories it can be observed that all nodes are continuously approaching the intrusion target and exhibit precise target tracking capabilities and dynamic response characteristics under the real-time position changes in the intrusion target.

Figure 14.

Navigation Trajectories of the System in the Countermeasure Capability Test. (a) The System Approaches the Interception Target. (b) The Intrusion Target Escapes. (c) The System Approaches the Interception Target Again. (d) The System Encircles the Intrusion Target.

When the distance between the system and the intrusion target reaches the critical value as shown in Figure 14b the intrusion target starts to escape. The escape of the intrusion target results in the failure of the first encirclement and interception. This indicates that the intrusion target’s countermeasure capability increases the system’s interception difficulty and also verifies the necessity for the system to have dynamic adjustment capability. After the intrusion target escapes the system quickly constructs a target position prediction model based on the latest target movement situation information uploaded by and issues corresponding new control commands accordingly. As shown in Figure 14c all nodes of the system cooperate to pursue the escaping target in accordance with the updated control commands. When the intrusion target enters the system’s interception radius as shown in Figure 14d the encirclement and interception phase begins immediately. Finally the system successfully restricts the intrusion target outside the safe distance of the guarded target .

The distance change curve between nodes and the intrusion target presented in Figure 15 provides a more intuitive basis for process analysis. From the curve characteristics the key phases in the entire operation process can be clearly identified including two approaching processes the target escape process and the final encirclement process.

Figure 15.

Distance Variation Between Nodes and the Intrusion Target at Different Phases of the Countermeasure Test.

Through the data analysis of Table 8 and Table 9 it can be known that when the intrusion target adopts Evasion Strategy 1 and Strategy 2 the average interception time of the system is 33.8 min and 32.6 min, respectively. In the test within the range, the average interception time reduction ratio reaches 14.8%, the improvement ratio is 18.5%, and the collision rate ranges from 0.30% to 0.34%, which is basically consistent with the data in the 1000 m × 1000 m range. This result shows that although different evasion strategies affect the system’s interception efficiency none of them lead to interception failure which confirms that under the control of the algorithm proposed in this paper the system exhibits good task completion capability when facing different evasion strategies.

Table 8.

Test Results 1 When the Target Has Countermeasure Capability.

Table 9.

Test Results 2 When the Target Has Countermeasure Capability.

6. Discussion

Through the verification of the above algorithm simulation tests, the algorithm proposed in this paper has formed differentiated advantages through technical integration and strategic innovation. Its core lies in the in-depth integration of dynamic prediction and anti-interference control, which solves the problem of insufficient accuracy caused by the disconnection between the two in traditional methods. Meanwhile, it optimizes resource allocation based on threat levels and adapts to adversarial scenarios through a two-stage strategy. This not only makes up for the shortcomings of existing frameworks in the balance of multi-vessel cooperation but also improves the response capability to high-dynamic targets, providing a more targeted technical path for cooperative interception in complex marine environments. From the perspective of technical improvement and engineering implementation, this study still has room for further expansion. The current research mainly focuses on common marine environments and typical task scales, and the adaptability to extreme sea conditions and large-scale multi-target scenarios can be further explored. The integration of dynamic characteristics in the threat level assessment model and the supplement of hardware-in-the-loop testing will help enhance the engineering practicality and robustness of the algorithm.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper conducts in-depth research on the core challenges in the cooperative interception task of multiple Unmanned Surface Vessels (USVs), including the strong dynamics of intrusion targets, complex marine environment interference, and insufficient multi-vessel cooperative accuracy. The adaptive dynamic prediction cooperative interception control algorithm constructs a complete technical framework for “task planning—anti-interference control—phased cooperation”. It lays a foundation for accurate interception through a threat level-oriented target assignment mechanism and an extended Kalman filter multi-step prediction model. Relying on a Two-stage architecture, it separates the cooperative encirclement module from the anti-interference module, effectively offsetting wind and current interference and reducing trajectory deviation and course fluctuation. Through a two-phase strategy of “target navigation—cooperative encirclement”, it optimizes the movement and distribution of nodes to form a stable blockade. Simulation verification shows that compared with the strategy without anti-interference measures, the node trajectory deviation of the adaptive algorithm is reduced by 40% and the course angle fluctuation is reduced by 50%. Compared with the limit cycle encirclement algorithm, the average interception time of this algorithm is shortened by 15%, the average final distance between the intrusion target and the guarded target is increased by 20%, and the collision rate (CRBAO and CRBAA values) is less than 0.3% when facing target escape, which significantly improves the interception efficiency and robustness in complex scenarios.

Although the algorithm in this paper shows excellent performance in simulation scenarios, there is still room for further deepening and expansion in the optimization of anti-interference mechanisms in extremely complex environments and the expansion of high-dynamic multi-target confrontation scenarios. Future research will focus on the deepening and engineering of the algorithm. For extreme marine environments (e.g., typhoons and strong turbulence), an interference prediction model integrating “data-driven—physical modeling” will be constructed, which will train a deep learning sub-model using historical measured data and combine the constraints of fluid mechanics equations to realize advanced prediction of coupled interference, and explores distributed communication optimization based on federated learning. Each USV functions as a local learning node, training a personalized transmission strategy leveraging its proprietary communication quality data (including packet loss rate and latency). Subsequently, the global strategy is updated via federated aggregation, which mitigates the degradation of collaborative efficiency induced by individual communication discrepancies and further enhances communication reliability as well as collaborative stability in complex marine environments. The multi-target cooperative confrontation scenario will be expanded, and a fusion framework of multi-agent reinforcement learning and differential game will be introduced. At the same time, hardware-in-the-loop testing will be carried out to verify the performance of the algorithm under sensor noise and communication delay, and a human–machine hierarchical decision-making mode will be built to further strengthen the framework of the multi-USV dynamic prediction cooperative interception control algorithm. In the future, the test will be further extended to a 10 km × 10 km open-sea scenario, aiming to focus on verifying “multi-node cross-regional collaboration” and “prediction correction under satellite communication delays”.

This study lays a theoretical and practical foundation for the engineering application of the multi-USV cooperative interception system and provides a highly adaptable technical solution for tasks such as maritime security and anti-smuggling. The proposed algorithm successfully connects the integration path of dynamic prediction theory, anti-interference control and multi-agent cooperative technology, opening up a new direction for intelligent interception operations in complex marine environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; Data curation, B.T.; Formal analysis, L.L.; Funding acquisition, Y.L.; Investigation, G.L.; Methodology, Y.L.; Project administration, G.L.; Resources, L.L.; Software, B.T. and X.X.; Supervision, Y.L. and Z.B.; Validation, B.T. and Z.B.; Visualization, Y.L. and S.G.; Writing—original draft, Y.L.; Writing—review and editing, B.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by Intelligent Fisheries Research Center of Anhui Provincial Key Laboratory of Aquaculture Project kfkt202501, in part by Anhui Provincial University Research Plan Project 2024AH050613.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- Gu, Y.; Wang, P.; Rong, Z.; Wei, H.; Yang, S.; Zhang, K.; Tang, Z.; Han, T.; Si, Y. Vessel intrusion interception utilising unmanned surface vehicles for offshore wind farm asset protection. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 299, 117395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zeng, R.; Lin, B.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, W.; Zhang, W. Multi-USV cooperative target encirclement through learning-based distributed transferable policy and experimental validation. Ocean Eng. 2025, 318, 120124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Yang, X.; Feng, B.; Liu, W.; Ye, H.; Zhu, Z.; Shen, H.; Xiang, Z. A navigation accuracy compensation algorithm for low-cost unmanned surface vehicles based on models and event triggers. Control Eng. Pract. 2024, 146, 105896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umsonst, D.; Sarıtaş, S.; Dán, G.; Sandberg, H. A Bayesian Nash Equilibrium-Based Moving Target Defense Against Stealthy Sensor Attacks. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2024, 69, 1659–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakıcı, E.; Karatas, M.; Eriskin, L.; Cicek, E. Location and Routing of Armed Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Carrier Platforms Against Mobile Targets. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 169, 106727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammadov, K.; Lim, C.C.; Shi, P. Unified Optimality Criteria for the Target–Attacker–Defender Game. J. Control Decis. 2024, 11, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadka, B.; Tripathy, T.; Tsalik, R.; Shima, T. A Max-Consensus Cyclic Pursuit Based Guidance Law for Simultaneous Target Interception. In Proceedings of the 2020 European Control Conference (ECC), Saint Petersburg, Russia, 12–15 May 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 662–667. [Google Scholar]

- Karras, G.C.; Bechlioulis, C.P.; Fourlas, G.K.; Kyriakopoulos, K.J. Formation Control and Target Interception for Multiple Multi-rotor Aerial Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Athens, Greece, 1–4 September 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, V.; Legrain, A.; Schindl, D. A Benders Decomposition Approach for a Capacitated Multi-vehicle Covering Tour Problem with Intermediate Facilities. In Integration of Constraint Programming, Artificial Intelligence, and Operations Research; Dilkina, B., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14742, pp. 277–292. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, I.S.; Shah, S.; Siddiqi, M.Z.; Wuttisittikukij, L.; Sasithong, P. Task Assignment and Path Planning of Multiple Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Using Integer Linear Programming. In Proceedings of the TENCON 2023 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON), Chiang Mai, Thailand, 31 October 2023–3 November 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 547–551. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Hu, Y.; Wang, P.; Qu, T. Parallel Nonlinear Model Predictive Controller for Real-Time Path Tracking of Autonomous Vehicle. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 16503–16513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Geng, J.; Cheng, Y.; Tang, L.; Duan, J.; Duan, F.; Li, S.E. Real-Time Resilient Tracking Control for Autonomous Vehicles Through Triple Iterative Approximate Dynamic Programming. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 1015–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Q. Optimal H∞ Control Based on Stable Manifold of Discounted Hamilton-Jacobi-Isaacs Equation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.02272. [Google Scholar]