Coupling Effect of the Bottom Type-Depth Configuration on the Sonar Detection Range in Seamount Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Description of Topographic and Hydrological Data

2.2. BELLHOP Model Simulation

3. Analysis of Results

3.1. Free Field (Not Significantly Affected by Seamount Shielding and Bottom Absorption)

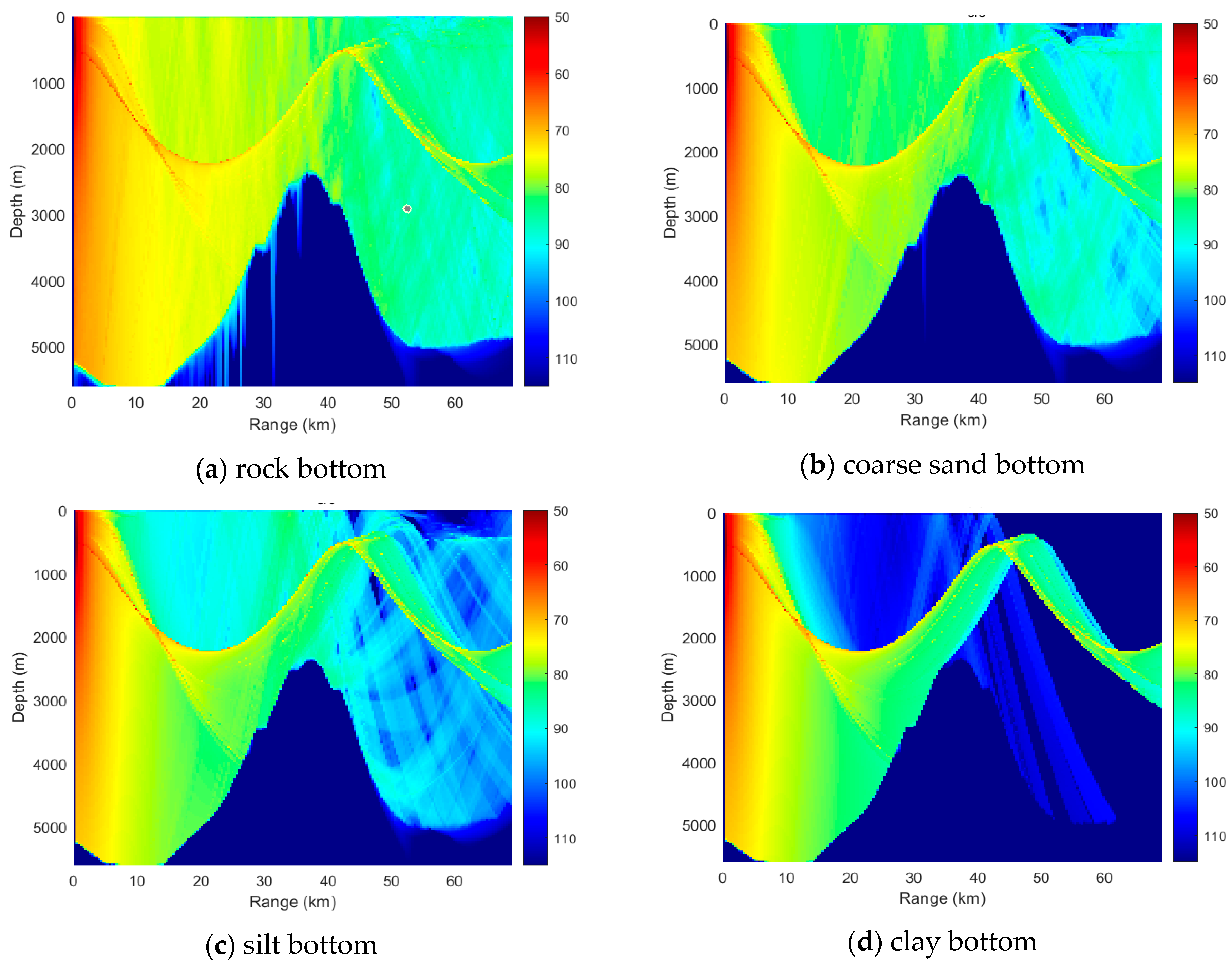

3.2. Shielded Field (Segmented by Bottom)

- (1)

- Strongly reflective type (rock):

- (2)

- Transitional type (coarse sand):

- (3)

- Absorptive type (silt):

- (4)

- Strongly absorptive type (clay):

4. Conclusions

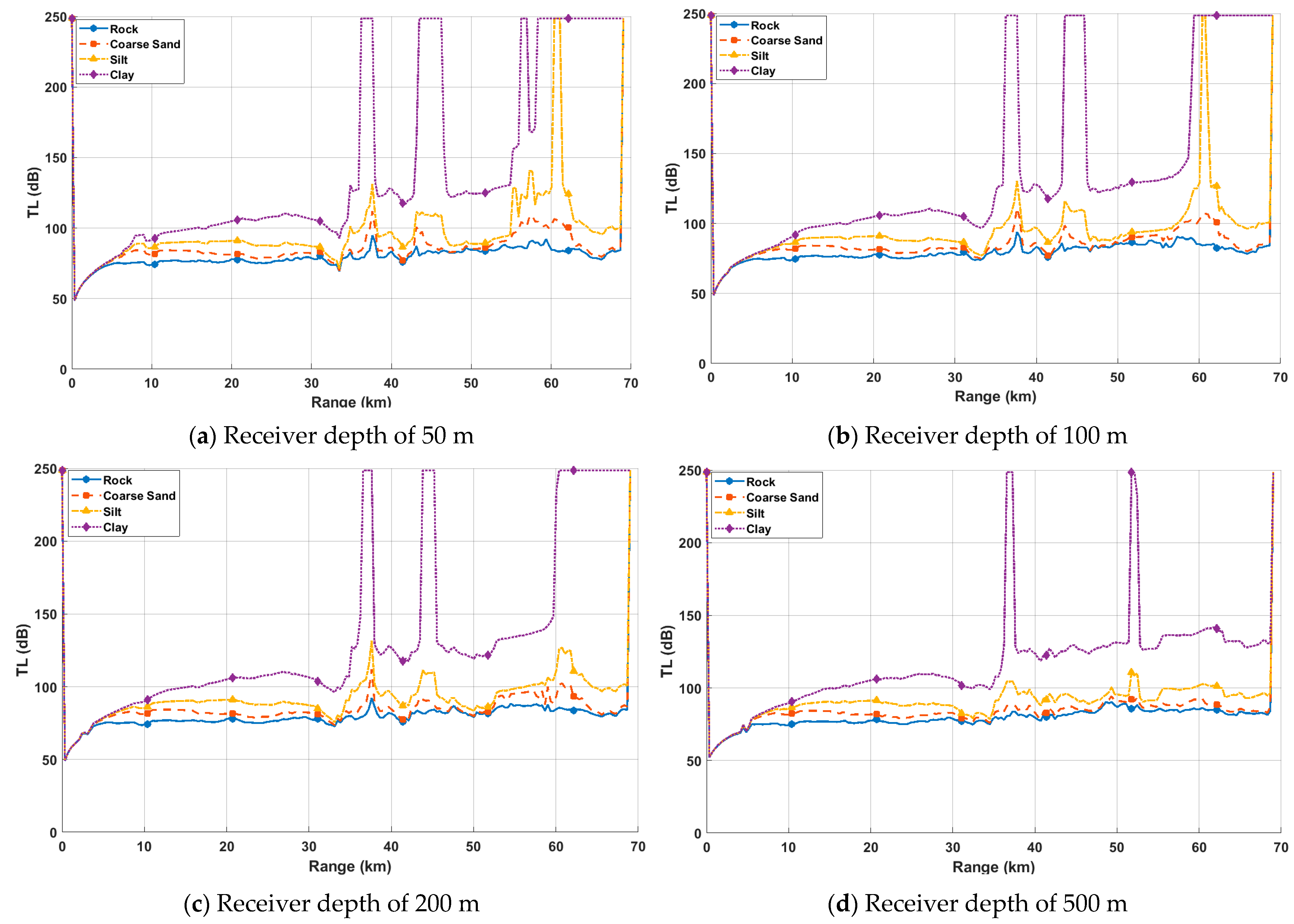

- (1)

- Bottom is the primary factor controlling the maximum sonar detection range in shallow layers (especially < 200 m) in seamount environments. The maximum detection range for rock bottom is almost eight times that of clay, indicating that a highly reflective bottom can effectively buffer the energy attenuation in the seamount acoustic shadow zone.

- (2)

- After seamount shielding, an absorptive bottom cannot provide effective reflected energy supplementation, and the sound intensity in the shadow zone mainly depends on diffraction. In contrast, deep sources (1000 m) have a large grazing angle for sound rays, making it difficult to diffract the top of the seamount effectively, resulting in a low diffraction gain. As a result, the absorptive bottom + deep source combination significantly amplifies the acoustic shadow effect. In contrast, the rock + shallow source combination effectively enhances the received signal in the shadow zone through the synergistic effect of strong bottom reflection and a surface sound channel waveguide.

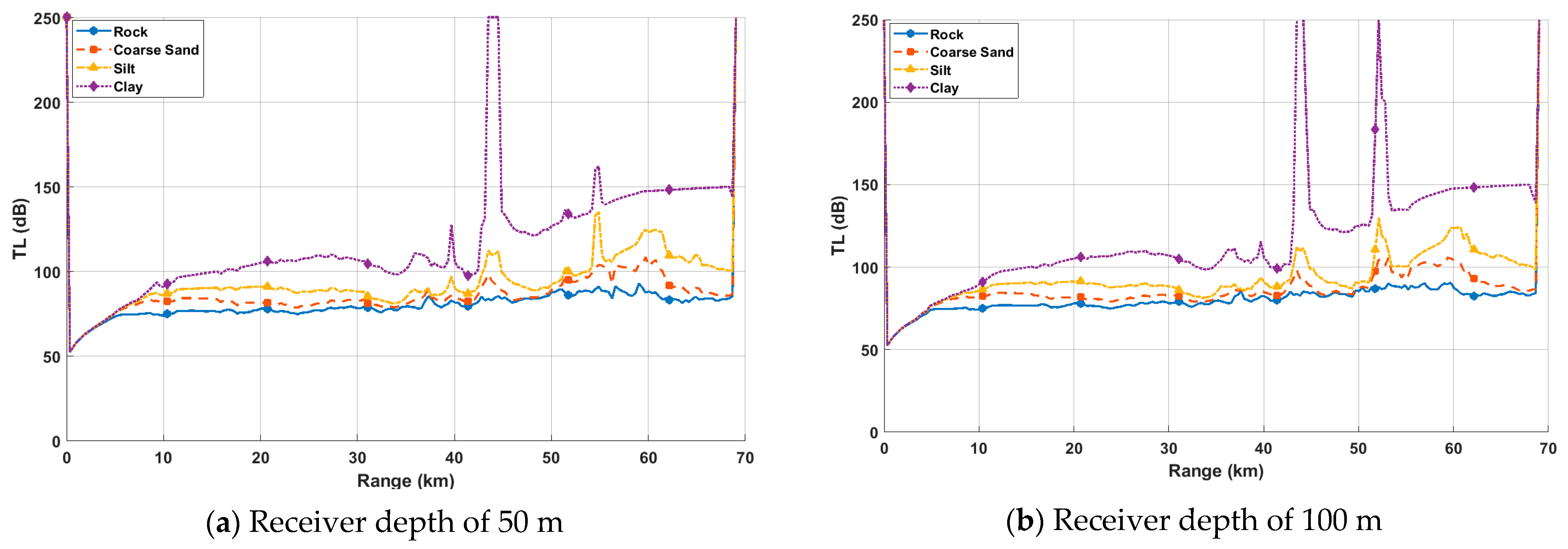

- (3)

- The shallow source–shallow receiver configuration can significantly weaken the seamount shadow effect: 300 Hz sound waves are confined in the surface sound channel, effectively bypassing seamount obstacles through diffraction, forward scattering, and multiple surface reflections.

- (4)

- The advantage provided by the bottom decreases with increasing receiver depth. When the receiver depth is ≥500 m, multipath propagation causes the transmission loss curves of the different bottom layers to be approximately parallel. The marginal impact of a single interface reflection is averaged, and the path loss is dominated by geometric spreading and multiple interface interactions.

5. Discussion on the Limitations of the BELLHOP Model

- (1)

- High-frequency limitation and diffraction effects: Ray-based models have limited capability in accurately representing diffraction and scattering when the acoustic wavelength is comparable to or larger than the scale of obstacles. While the 300 Hz frequency and large-scale seamounts in this study fall within the valid regime of ray theory, higher frequencies or fine-scale seabed roughness would require complementary approaches such as normal mode or parabolic equation methods.

- (2)

- Simplification of three-dimensional effects: The simulations are performed using two-dimensional vertical slices, thereby neglecting horizontal variations in seamount morphology that could induce three-dimensional refraction, focusing, or defocusing. In realistic 3D environments, such lateral effects may lead to more complex spatial patterns of transmission loss.

- (3)

- Uncertainty in environmental inputs: Model accuracy critically depends on the fidelity of input parameters—particularly the sound speed profile and seabed acoustic properties. The climatological HYCOM data and representative bottom parameters used herein cannot fully capture the spatiotemporal variability of real ocean conditions, potentially introducing prediction errors.

- (4)

- Treatment of signal coherence: The standard BELLHOP implementation computes incoherent transmission loss (i.e., energy summation), whereas actual sonar signal processing often exploits coherent interference among multipath arrivals. In shallow water or specific depth configurations where strong multipath interference occurs, the incoherent approach may smooth out fine-scale interference structures, leading to localized biases in TL estimation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wei, Q.Q.; Han, D.; Xu, C.; Sun, D.J. Acoustic propagation under typical seabed topography based on ray model. Technol. Innov. Appl. 2017, 32, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.L.; Qin, J.X.; Qi, Y.B.; Li, Z.L. Research progress in deep-sea acoustics and underwater sound source localization. Acta Acust. 2025, 50, 551–570. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.H.; Li, Z.L.; Li, W.; Qin, J.X. Study on horizontal refraction effect of acoustic propagation in deep-sea seamount environments. Acta Phys. Sin. 2018, 67, 224302. [Google Scholar]

- Northrop, J.; Wheeler, R.B. Underwater Sound Reflections from Some Seamounts Off the California Coast. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1972, 51, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadov, R.A. Long-range sound propagation in the northwestern region of the Pacific Ocean. Acoust. Phys. 2006, 52, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.X.; Zhang, R.H.; Luo, W.Y.; Peng, Z.H.; Liu, J.J.; Wang, D.J. Sound propagation from the shelfbreak to deep water? Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 2014, 57, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Dong, C.; Ji, Y.; Wang, C.; Shu, Y.; Liu, L.; Ji, J. Influences of deep-water seamounts on the hydrodynamic environment in the northwestern Pacific Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2021, 126, e2021JC017396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, Z.L.; Zhang, R.H.; Qin, J.X.; Li, J.; Nan, M.X. The effects of seamounts on sound propagation in deep water. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2015, 32, 064302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, Z.; Li, W.; Yu, Y. Three-dimensional sound propagation in the south china sea with the presence of seamount. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Lv, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Shi, Y. Research on the Key Problems of 3D Acoustic Field Modeling and Simulation in Complex Submarine Environment. In Proceedings of the 2024 OES China Ocean Acoustics (COA), Harbin, China, 29–31 May 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Makarov, D.V.; Petrov, P.S.; Uleysky, M.Y. Random Matrix Theory for Sound Propagation in a Shallow-Water Acoustic Waveguide with Sea Bottom Roughness. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, A.; Bashir, B.; Alsalman, A.; Elsaka, B.; Abdallah, M.; El-Ashquer, M. Evaluating the Accuracy of Global Bathymetric Models in the Red Sea Using Shipborne Bathymetry. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2025, 53, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulin, O.E.; Yaroshchuk, I.O. On average losses of low-frequency sound in a two-dimensional shallow-water random waveguide. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wu, J.; Mo, Y.; Sun, B.; Ma, L. The same reflective characteristics for different effective geoacoustic parameters in different models. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2020, 46, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urick, R.J. Principles of Underwater Sound, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

| Bottom | Density (g/cm3) | Longitudinal Wave Velocity (m/s) | Shear Wave Velocity (m/s) | Longitudinal Wave Velocity (dB/λ) | Shear Wave Attenuation (dB/λ) | Roughness RMS (m) | R Reflection Coefficient | Impedance Z (106 Pa·s/m) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rock | 2.65 | 3000 | 1200 | 0.125 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 5.41 | 0.676 | 7.95 |

| Coarse sand | 1.95 | 1775 | 250 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.54 | 0.385 | 3.46 |

| Silt | 1.6 | 1600 | 170 | 0.35 | 0.6 | 0.05 | 0.71 | 0.25 | 2.56 |

| Clay | 1.4 | 1475 | 150 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.015 | 0.25 | 0.148 | 2.07 |

| Source Depth (m) | Receiver Depth (m) | Remarks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 m | 50 m | 68.6743 | 68.6092 | 68.5073 | 68.5030 | Same depth |

| 50 m | 100 m | 67.6611 | 42.8094 | 33.6605 | 6.6498 | |

| 50 m | 200 m | 66.6190 | 41.5821 | 33.3814 | 5.7474 | |

| 50 m | 500 m | 65.9530 | 40.4283 | 32.0015 | 6.2248 | |

| 150 m | 50 m | 66.7286 | 41.9744 | 33.7407 | 5.6150 | |

| 150 m | 100 m | 66.9931 | 41.9649 | 33.6325 | 6.1476 | |

| 150 m | 200 m | 67.2994 | 42.1976 | 33.9115 | 5.4158 | |

| 150 m | 500 m | 42.6504 | 40.8083 | 34.6093 | 5.8115 | |

| 500 m | 50 m | 41.5098 | 34.3578 | 6.2410 | 6.0953 | |

| 500 m | 100 m | 41.4648 | 34.5435 | 6.3083 | 6.1122 | |

| 500 m | 200 m | 41.2447 | 34.2077 | 6.1615 | 6.1290 | |

| 500 m | 500 m | 46.9816 | 46.1930 | 45.7020 | 45.5134 | Same depth |

| 1000 m | 50 m | 40.3844 | 25.0032 | 7.5567 | 7.4273 | |

| 1000 m | 100 m | 38.8536 | 24.9279 | 7.5044 | 7.3206 | |

| 1000 m | 200 m | 58.3374 | 7.9756 | 7.8523 | 7.8153 | |

| 1000 m | 500 m | 48.6346 | 48.5820 | 48.5319 | 48.5201 |

| Bottom | Number of Configurations | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | Maximum Deviation | Coefficient of Determination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rock | 16 | 0.61 | 0.78 | +1.23 (50/100) | 0.996 |

| coarse sand | 16 | 2.87 | 3.42 | +5.83 (150/50) | 0.942 |

| silt | 16 | 1.22 | 1.63 | +0.98 (1000/50) | 0.981 |

| clay | 16 | 1.22 | 1.65 | +1.05 (1000/50) | 0.983 |

| Total | 64 | 1.38 | 1.92 | +5.83 | 0.981 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, X.; Zhang, S.; Chen, F.; Wang, P. Coupling Effect of the Bottom Type-Depth Configuration on the Sonar Detection Range in Seamount Environments. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010089

Sun X, Zhang S, Chen F, Wang P. Coupling Effect of the Bottom Type-Depth Configuration on the Sonar Detection Range in Seamount Environments. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010089

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Xiaofang, Shisong Zhang, Feiyu Chen, and Pingbo Wang. 2026. "Coupling Effect of the Bottom Type-Depth Configuration on the Sonar Detection Range in Seamount Environments" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010089

APA StyleSun, X., Zhang, S., Chen, F., & Wang, P. (2026). Coupling Effect of the Bottom Type-Depth Configuration on the Sonar Detection Range in Seamount Environments. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010089