Abstract

In the construction of large cruise ships, the restricted deck space and dense obstacles create a strongly coupled problem between path planning and sequence optimization during prefabricated cabin boarding operations, significantly impairing overall installation efficiency. To coordinately optimize the boarding sequence of multiple cabins and minimize operational conflicts, this study proposes a dual-layer coordinated planning methodology. The lower layer generates feasible paths satisfying kinematic and contour-based obstacle avoidance constraints through optimal control theory, while the upper layer introduces a dynamic priority evaluation mechanism based on grid mapping and an “enclosure factor”, combined with a reverse planning strategy to dynamically adjust the cabin boarding sequence. Through iterative feedback between path feasibility and sequence efficiency, the proposed method effectively resolves the strong coupling between sequencing and path planning. Case validation demonstrates that the proposed approach significantly reduces total installation time compared to conventional sequence planning methods, proving its effectiveness and practical value in enhancing the efficiency of coordinated multi-cabin installation.

1. Introduction

As the pinnacle of high-end shipbuilding, large cruise ships are characterized by their massive scale, complex structural systems, and exceptionally high comfort requirements, rendering them extremely challenging and time-consuming to construct [1,2]. A single large cruise vessel typically contains thousands of cabins of various categories. According to industry analysis and case studies, the manufacturing and installation of these cabins account for 40% to 50% [3] of the total man-hours required for the ship’s construction. Consequently, optimizing the cabin construction process is of paramount importance for shortening the overall build cycle and reducing construction costs.

The manufacturing and installation of cabins constitute the critical path determining the overall construction timeline. To overcome the inefficiencies inherent in traditional on-site assembly methods, the prefabricated cabin construction approach has become the industry standard [4]. This paradigm transforms substantial serial operations into parallel processes by completing structural work, interior outfitting, and pipeline integration concurrently within the shipyard workshops prior to installation. This shift fundamentally compresses the construction schedule for cabin zones while enhancing quality controllability. However, the efficiency advantages of prefabricated cabins face a significant challenge during the cabin boarding phase. The cabin boarding process is not merely a logistical operation but constitutes a complex dynamic scheduling problem involving tightly coupled on-deck path planning and boarding sequence considerations. Different boarding sequences directly alter the dynamic obstacle distribution across the deck space: initially installed cabins obstruct potential pathways for subsequent units, forcing them to take longer detours or endure waiting periods, thereby creating cascading delays. In large cruise ship construction, non-value-added waiting time resulting from transfer path conflicts and suboptimal sequencing can account for over 15% of the total installation man-hours in cabin zones [5]. Consequently, the boarding process for prefabricated cabins has emerged as a bottleneck constraining the full realization of their efficiency potential. There is a pressing need for research focused on optimizing the boarding sequence of prefabricated cabins with the objective of minimizing the overall installation cycle [6].

Regarding sequencing and path planning, existing research has developed various methodological frameworks that can be broadly categorized as follows: In the domain of sequence planning, Zhao et al. [7] proposed an integrated task allocation and sequence planning framework for multi-station multi-robot coordinated assembly processes. Utilizing an enhanced biased random key genetic algorithm, they effectively improved robotic assembly efficiency. Dai et al. [8] developed a clustering-based optimal sequence planning method for tomato harvesting, combining density-based clustering concepts with shortest motion paths to automatically classify multiple adjacent tomatoes into candidate picking clusters and determine optimal harvesting sequences. Mao et al. [9] designed a stochastic optimization algorithm integrating artificial intelligence technology with multi-objective genetic algorithms for end-of-life product disassembly, successfully establishing a multi-objective optimization model for disassembly sequences of used automotive components under uncertain conditions. In the field of path planning, various metaheuristic algorithms have been employed to solve path planning problems. For example, Song et al. [10] addressed the path smoothness issues in particle swarm optimization by introducing high-order Bezier curves to smooth robot movement paths. Lou et al. [11] proposed a golden jackal optimization algorithm with non-linear energy decay strategies for path planning, incorporating roulette wheel selection and Levy flight strategies to control algorithm position updates and prevent path solutions from converging to local optima. Rao et al. [12] investigated a unique artificial potential field-enhanced A-Star algorithm for path planning in dual-quadrotor cooperative transportation systems, achieving safe and effective collaborative suspended transport. Song et al. [13,14] presented a path planning method based on the neutral-surface and convolution smoothing for multi-machine cooperative manufacturing. He et al. [15] addressed the path planning problem for tower cranes by proposing an improved ant colony algorithm that reduces optimal path length and enhances path quality. Specifically addressing prefabricated cabin transfer path planning, Ju et al. [6] introduced and developed an enhanced A-Star algorithm to handle grid-based obstacles and boundary obstacles during cabin transportation path planning on-deck ships. Current methodologies demonstrate limited dedicated investigation into prefabricated cabin boarding for cruise ship applications. The scarce existing research specifically addressing cabin boarding has predominantly focused on path planning considerations while largely neglecting the critical coupling between sequence planning and path optimization. Consequently, there remains a significant research gap regarding integrated sequence-path planning for prefabricated cabin boarding operations, particularly the development of comprehensive methodologies that simultaneously address both sequential dependencies and spatial constraints.

In contemporary cruise ship construction, cabin installation is generally conducted through two distinct methodologies: modular prefabricated block assembly and individual cabin boarding within completed deck structures. This study focuses on the latter approach, addressing the boarding sequence and path planning of prefabricated cabins on fully constructed and spatially constrained decks. In this operational phase, cabins are transported horizontally through designated deck openings and positioned within a fixed planar layout containing structural obstacles and previously installed units. The proposed methodology is designed to optimize the planar scheduling and routing under these confined deck conditions, independent of modular block assembly or vertical integration processes.

In response to the aforementioned analysis, this paper proposes a dual-layer coordination strategy for planning the cabin boarding sequence based on an “enclosure factor”. The lower layer aims at single cabin on-deck path finding, which employs an optimal control method for planning optimal path of individual cabins avoiding spacial interference. The upper layer aims at multiple cabins boarding sequence ranking, which dynamically calculates the “enclosure factor” for each cabin’s target position based on the current deck spatial state to determine the boarding priority sequences. These two layers interact iteratively through path feasibility information, successfully resolving the strong coupling between path planning and sequencing. This approach significantly enhances overall operational efficiency by achieving an effective balance between computational complexity and solution quality, thereby realizing optimized cabin boarding sequencing.

The subsequent sections of this paper are organized as follows. The prefabicated cabin boarding problem is first introduced in Section 2. Subsequently, the lower-layer on-deck path finding and the upper-layer boarding sequence ranking approaches are presented in Section 3. Section 4 illustrates the experimental validation results, and Section 5 summarized the whole paper.

2. Formulation of the Cabin Boarding Problem

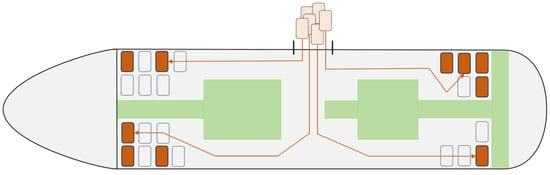

The superstructure construction zones of cruise ships are universally characterized by spatially constrained and structurally complex environments. The cabin boarding process is illustrated in Figure 1. As can be seen, within the confined areas, a strong coupling relationship exists between cabin boarding path and installation sequence. Unreasonable boarding sequence can trigger a cascade of operational issues: initially installed cabins may obstruct critical pathways, creating dynamic obstacles that force subsequent units to adopt elongated detours or become completely immobilized, resulting in “transfer blockages”. Concurrently, improperly sequenced adjacent cabin installations may require overlapping safety zones for their respective operations, generating “construction conflicts” that compel work stoppages and subsequent operational delays.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of cabin boarding problem.

These path conflicts and construction interferences not only lead to the failure of individual cabin installations but also disrupt the overall construction rhythm, generating substantial non-value-added waiting time and significantly prolonging the zonal construction cycle. Consequently, traditional empirical approaches that decouple path planning from sequencing have proven inadequate. Formulating efficient, conflict-free cabin boarding operations within this complex environment characterized by tight path-sequence coupling has emerged as a critical bottleneck constraining efficiency improvements in cruise ship construction.

3. Dual-Layer Coordinated Approach for Prefabricated Cabin Boarding Sequencing

3.1. Lower-Layer On-Deck Path Finding for Prefabricated Cabin Based on Optimal Control

To address the path planning challenges for prefabricated cabin boarding within confined deck environments, this section proposes a methodology grounded in optimal control theory. The approach transforms the path planning problem into a continuous-time optimal control formulation, enabling the generation of feasible trajectories under multiple constraints through numerical solution of the derived optimal control problem. The specific transformation procedure is detailed as follows.

- (1)

- The optimization objectives of the prefabricated cabin boarding path planning problem are transformed into the cost functional of a continuous-time optimal control problem.

With the minimization of cabin boarding operation time as the optimization objective, the performance index function is defined as:

where denotes the shortest boarding path length, represents the cabin boarding initiation time, indicates the terminal time when the cabin moves from the starting point to the target position, and signifies the translational velocity of the prefabricated cabin during boarding operations.

- (2)

- The kinematic mechanism during the prefabricated cabin boarding process is transformed into the state equations within the optimal control formulation.

Considering the kinematic characteristics of the cabin, its state-space model is established as follows:

where represent the coordinates of the cabin’s center in the two-dimensional deck coordinate system, denotes the velocity direction angle of the prefabricated cabin during motion; indicates the translational velocity of the cabin during boarding; constitute the control inputs for the cabin boarding process, corresponding to the cabin’s translational acceleration and angular velocity, respectively.

- (3)

- The pose requirements at the initial and terminal points are transformed into boundary conditions for the state variables, specifically as initial and terminal state constraints.

Initial conditions: Determined by the starting position of the cabin boarding.

where represent the corresponding coordinates of the -th prefabricated cabin’s initial position at the hull-side opening within the deck coordinate system at boarding commencement. Consequently, and denote the positional constraints of the cabin at boarding initiation, indicates the cabin’s stationary state at boarding commencement, and specifies the required boarding direction angle of the cabin at boarding initiation.

Terminal conditions: Determined by the target installation position and process requirements.

where and denote the coordinates of the target position for the -th prefabricated cabin within the deck coordinate system, and represents the required cabin orientation angle to be maintained when the -th prefabricated cabin reaches its designated position.

- (4)

- Collision avoidance constraints are transformed into state variable constraints within the optimal control problem.

To address collision detection between cabin geometric profiles and rectangular obstacles, an area-based computational method is employed [16]. For any vertex on the cabin contour, the sum of the areas of four triangles formed by sequentially connecting this vertex with the four vertices of the rectangular obstacle is calculated. If this cumulative area exceeds the area of the rectangle, no collision is determined; if the areas are equal, a collision is identified. This method requires validation at multiple discrete points along the path to ensure a collision-free boarding process.

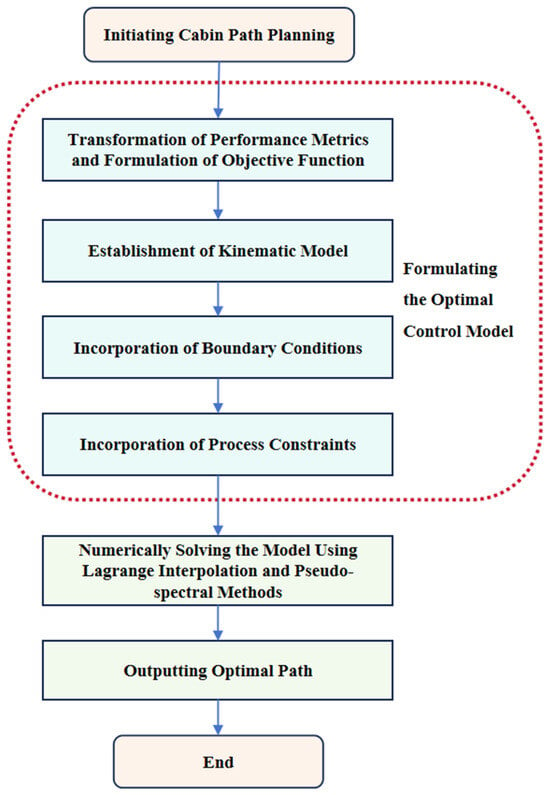

Through the aforementioned transformations, the cabin boarding path planning problem has been converted into a conventional optimal control problem. This study employs commonly used Lagrange interpolation [17] and pseudo-spectral methods [18,19] for numerical solution of this optimal control model. The core computational workflow is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Cabin on-deck path finding flowchart.

3.2. Upper-Layer Boarding Sequence Ranking for Prefabricated Cabins Based on the Enclosure Factor

The transportation planning process for prefabricated cabins in cruise ships involves not only designing movement paths for an individual cabin but also coordinating the boarding sequence of multiple cabins. The path generation methodology elaborated in the previous section primarily addresses the computation of feasible trajectories for single cabins when their target installation positions are predetermined. However, in practical operations, initially positioned prefabricated cabins require subsequent system integration and installation procedures, and the workspace they occupy continuously impacts the viable pathways for all subsequent cabin boardings. Consequently, when determining cabin boarding sequences, it is essential to comprehensively account for both the spatial interdependencies among adjacent cabins and the inherent spatial constraints imposed by the deck’s structural configuration.

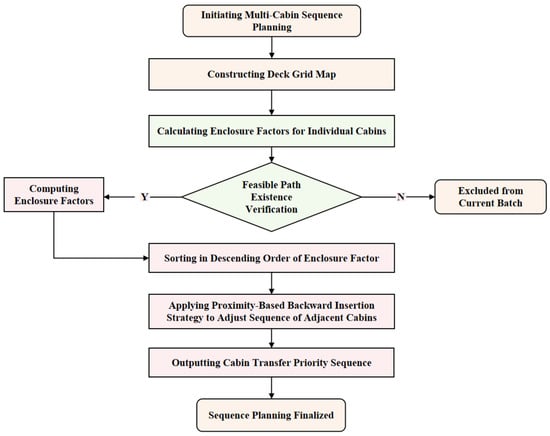

To address above complex challenge, this section introduces a priority coordination mechanism based on cabin enclosure factors. This mechanism is composed of two aspects. First, all cabins are divided into batches, and rank the batch sequence so that one can find feasible on-deck paths for all cabins within one batch. Then, rank the boarding sequence of cabins within each single batch, according to the defined enclosure factor.

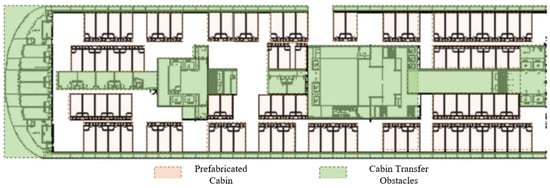

Details of the enclosure factor definition and the priority scheduling are presented as follows. As a precondition, the grid map of the deck for cabin assembly should be constructed. The construction of this grid map must satisfy the following spatial representation requirements: (1) maintain uniform grid cell dimensions; (2) achieve comprehensive grid coverage of the deck plane; (3) ensure each discrete cabin unit completely occupies specific grids, eliminating boundary ambiguities between multiple cabins; (4) represent bulk cabins and fixed obstacle areas through single or combined grid configurations; (5) align grid boundaries with bulkheads and shipside structures as reference benchmarks; (6) prevent spatial overlap between cabins and obstacles within any individual grid cell.

Integrating the aforementioned conditions, the simplified grid map for prefabricated cabin layout on cruise ships is illustrated in Figure 3. On this visualization, prefabricated cabins and obstacle distributions are distinctly marked using color coding, while blank grids represent unoccupied deck space. It is important to note that the grid representation primarily captures relative positional relationships and spatial topology between installation points, rather than strictly representing exact dimensional information of cabins. Each grid cell serves as a discrete spatial unit for planning purposes, with cabins of similar dimensions that are suitable for prefabrication being mapped to single grid cells to establish their adjacency and accessibility relationships within the deck environment.

Figure 3.

Illustration for construction of the deck grid map.

Within the constructed grid-based deck map, individual cabin units are typically surrounded by eight adjacent grid cells (except for units located at boundaries). This spatial configuration inevitably leads to intersecting and conflicting transport trajectories among multiple prefabricated cabins, potentially delaying the scheduled positioning of certain units. Notably, different cabin types and their respective target installation positions exhibit varying degrees of spatial enclosure characteristics. Generally, cabins with more pronounced enclosure properties demonstrate higher susceptibility to obstruction from other cabin units or fixed obstacles during transfer operations. To effectively mitigate mutual interference among multi-cabin transport paths, this section proposes an enclosure factor assessment methodology based on the deck grid map, as formulated in Equation (5). The constant value 8 is added to ensure non-negative enclosure factors, shifting the original range [−8, 0] to [0, 8] for better interpretability while preserving the relative ranking of cabins.

where is the enclosure factor of the target position for prefabricated cabin ; is the number of bulkhead or hull plating obstacles along the four primary boundaries of the cabin’s target grid position; is the contiguous unoccupied space in adjacent grids excluding bulkhead obstacles; is the number of other executable prefabricated cabins in the four primary neighboring grids; is the number of other executable prefabricated cabins in the four diagonal neighboring grids; In Equation (5), the parameter ω represents the relative influence weight of diagonally adjacent cabins compared to orthogonally adjacent ones. The value range of 0.5–0.75 is geometrically justified: in an eight-neighbor grid system, the Euclidean distance to a diagonal neighbor is √2 times that to an orthogonal neighbor, yielding an influence weight of √2/2 ≈ 0.707 [20]. This is consistent with established principles in grid-based path planning where diagonal movements have distinct cost implications. In our experimental implementation, ω = 0.7 was adopted as a representative value within this theoretically supported range. is the decision variable, where indicates a feasible path exists from the transfer starting point to cabin ’s target position under current conditions, and indicates no such path exists. Note that the cabins having feasible paths are assigned as one batch, and then ranked according to the finite enclosed factor; while the cabins having no feasible path should be ranked in subsequent batches, which are given an infinite enclosed factor temporarily. Using Equation (5), the enclosure factor for individual cabin boarding is computed. The boarding sequence for all currently executable prefabricated cabins, within one single batch and finite enclosed factor, is then determined based on the magnitude of their enclosure factors. Through iterative evolution of cabin batches, the boarding sequence for all prefabricated cabins can then be progressively optimized.

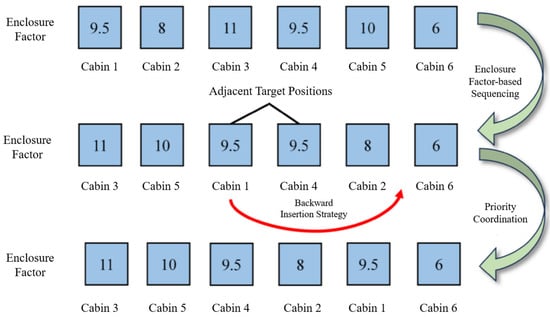

Furthermore, the sequence of prefabricated cabin boarding in cruise ship construction must account for safety distance constraints during the installation of adjacent target positions. For cabins with identical enclosure factor values whose target positions are adjacent along the four primary boundaries, a proximity-based backward insertion strategy is implemented. This approach re-positions such cabins in the sequence to follow those with different enclosure factors, as illustrated in Figure 4, thereby reducing sequential boarding on adjacent target positions and enhancing both transfer and installation efficiency. The core procedural workflow for the boarding priority scheduling within one batch of cabins having feasible paths is detailed in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Priority coordination process for prefabricated cabins boarding within one executable batch.

Figure 5.

Flowchart of cabin boarding priority planning within one batch of cabins.

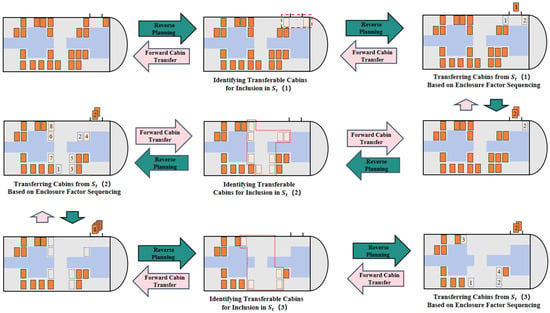

3.3. Global Boarding Sequence Scheduling for All Cabins by Dual-Layer Coordinated Mechanism

The solution process for the prefabricated cabin boarding sequence planning method follows the reverse planning strategy. Denote the set of cabins waiting for boarding as , assuming all cabins are initially at their installation positions. The procedure begins by identifying the cabins within the cabin set that have feasible path from the boarding entrance to the installation position, using the lower-layer path finding algorithm presented in Section 3.1. These transferable cabins are placed into a temporary set . The cabins within the temporary set are then ranked according to the upper-layer ranking method described in Section 3.2. The ranked cabins are subsequently moved to the priority-coordinated set and removed from the original set . This procedure is repeated iteratively until all cabins in set have been systematically planned. During this process, each temporary cabin sec represents a batch of cabins, and the generation sequence of the batch is reversed while boarding, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the sequential solution procedure based on inverse batches.

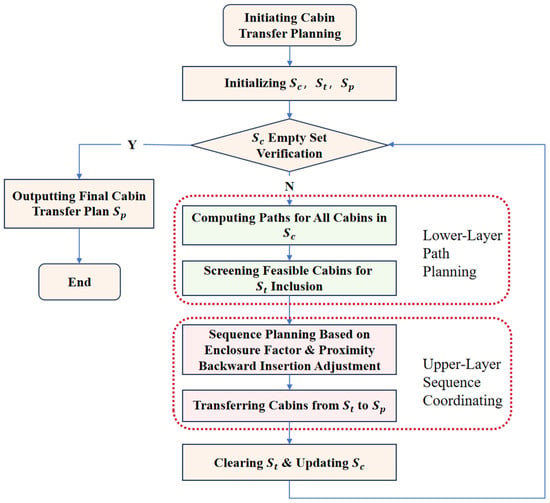

Solution procedure for the dual-layer coordinated cabin boarding method is summarized as follows.

- Step 1: Initialize the complete set of prefabricated cabins on the deck as , with temporary set and transfer priority coordination set , where both and are initially empty sets;

- Step 2: Check whether set is an empty set. If not, proceed to Step 3; otherwise, proceed to Step 8;

- Step 3: Calculate the on-deck paths from the entrance to the target positions for all prefabricated cabins contained in set ;

- Step 4: Add the information of prefabricated cabins with feasible transfer paths to the temporary set ;

- Step 5: Rank the cabins in temporary set in descending order based on their enclosure factors;

- Step 6: Append all cabin information from temporary set to the transfer priority coordination set ;

- Step 7: Clear the temporary set and return to Step 2;

- Step 8: Terminate the process, output set , and reverse the batches sequence thus generating the final cabin boarding operation plan.

The workflow of the algorithm is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Planning methodology flowchart for prefabricated cabin boarding.

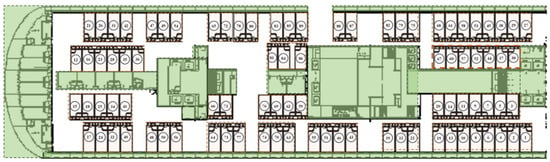

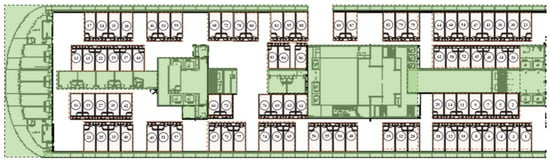

4. Verification Tests

In this study, the hierarchical coordinated planning framework elaborated in Section 3 will be implemented to validate its efficacy. The experimental data, including the cabin layout shown in Figure 8, are derived from an actual cruise ship construction project provided by a collaborating shipyard, with appropriate anonymization to protect proprietary information. The spatial configurations and operational constraints reflect real-world conditions encountered in large cruise ship construction. The experimental environment encompasses 89 prefabricated cabins with identification codes ranging from 080114-8472 to 08030W-8359, whose spatial distribution is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Layout of prefabricated cabins in main vertical zones 1–3 on deck 8 of a large cruise ship.

Under these experimental conditions, the coordinated planning methodology proposed in this study is applied to solve the cabin boarding problem. The obtained optimal solution will be systematically compared with solutions generated by the enhanced A-Star algorithm [21] from existing research. To ensure experimental fairness, critical parameters including installation duration after cabin arrival at target workstations and safety operation clearances remain consistent with the reference study, while schedule calculations are performed under the assumption of unrestricted personnel allocation for transfer and installation operations. All remaining experimental parameters adhere to the standards specified in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameter Configuration for Prefabricated Cabin boarding Path Planning in Cruise Ships.

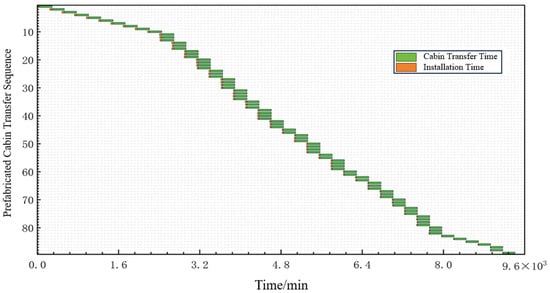

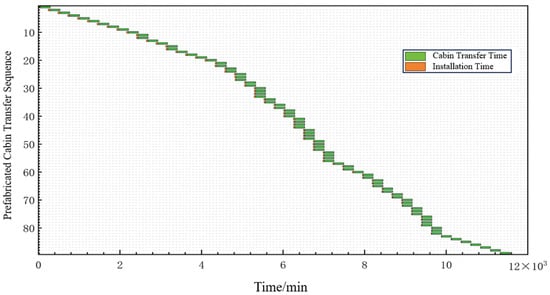

Figure 9 and Figure 10 respectively present the cabin boarding sequence plans generated by the two methodologies under identical experimental conditions. In accordance with the installation process requirements for cruise ship prefabricated cabins reaching their designated positions, the average installation time per cabin is 180 min [22]. Comparative analysis of the results reveals that within the current deck structural environment, the solution incorporating the improved A-Star algorithm demonstrates a higher frequency of sequential transfers to adjacent target positions compared to the methodology proposed in this paper. This leads to increased occurrences of safety distance constraint violations during cabin installation, consequently generating more significant disruptions to continuous transfer operations.

Figure 9.

Hierarchically coordinated boarding sequence plan for prefabricated cabins in cruise ships.

Figure 10.

Prefabricated cabin boarding sequence plan using the integrated improved A-Star algorithm.

Based on the cabin boarding sequences determined by the two planning methodologies, the total operational duration was calculated respectively, generating operation timeline results for all prefabricated cabins within the experimental area as illustrated in Figure 11 and Figure 12. Comparative analysis demonstrates that the proposed methodology yields significant advantages in total project duration over the existing approach, manifested through: a substantial increase in parallel cabin installations and more scientifically structured scheduling of installation processes for individual cabins. Quantitative evaluation reveals the conventional method requires 11,569.5 min to complete all operations, while the hierarchically coordinated planning framework established in this study achieves completion in merely 9409.5 min—representing an 18.7% reduction in project duration. These results validate the efficacy of the proposed methodology in addressing prefabricated cabin boarding planning challenges for cruise ships, not only enhancing overall transfer efficiency but also ensuring continuity and stability throughout the construction process.

Figure 11.

Temporal results of cabin boarding planning based on hierarchical coordination in cruise ships.

Figure 12.

Temporal results of prefabricated cabin boarding using the integrated improved A-Star algorithm.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses the complex scheduling problem arising from the tight coupling between sequence and path planning during prefabricated cabin boarding in cruise ships by proposing a dual-layer coordination methodology focused on sequence optimization. The core of this approach lies in achieving global optimization of the boarding sequence through iterative interaction between the two layers: the lower layer ensures path feasibility for individual cabins, while the upper layer dynamically evaluates the spatial occlusion degree of each installation workstation via the enclosure factor, determines cabin boarding priorities accordingly, and employs a reverse planning strategy to generate conflict-free installation sequences.

Experimental results demonstrate that this coordination mechanism effectively prevents path blockages and operational conflicts caused by suboptimal sequencing, ensuring smooth and efficient cabin installation processes. Compared to conventional methods, the proposed approach achieves significant optimization in total project duration, highlighting the necessity and superiority of systematic coordinated planning for boarding sequences under complex spatial constraints.

The core contribution of this study lies in proposing and validating an innovative dual-layer coordinated optimization mechanism and its mathematical model, providing a methodological framework and algorithmic engine for solving the tightly coupled sequence-path planning problem in cabin boarding. While the proposed method is technically compatible with existing industrial digital environments (e.g., CATIA, Siemens NX, AVEVA, FORAN) through standardized data interfaces, its primary value at this stage is demonstrated through superior performance in solving the fundamental optimization problem itself. The method’s effectiveness has been rigorously validated using real-world cabin layout data from an actual cruise ship project, showing an 18.7% reduction in total installation time compared to conventional approaches.

Author Contributions

Z.L. and Q.Z. proposed the original idea; Q.Z. and L.Z. performed the experiments; S.D. and Z.L. wrote the manuscript; J.L. and D.S. reviewed and edited the manuscript; D.S. contributed to the direction, and content, and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the constructive comments of the reviewers and editor.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, W. Optimization of Reverse Logistics Networks for Hazardous Waste Incorporating Health, Safety, and Environmental Management: Insights from Large Cruise Ship Construction. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrichiello, V.; Gualeni, P. Systems Engineering and Digital Twin: A Vision for the Future of Cruise Ships Design, Production and Operations. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. (IJIDeM) 2019, 14, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, W.; Wu, X.; Dong, R.; Lin, P. An Optimization Method for Location-Routing of Cruise Ship Cabin Materials Considering Obstacle Blocking Effects. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Ock, J. Unit Modular in-Fill Construction Method for High-Rise Buildings. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 20, 1201–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Liu, K.; Qiu, W.; Kang, Z. An Assembly Sequence Planning Method Based on Multiple Optimal Solutions Genetic Algorithm. Mathematics 2024, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, L.; Wu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, K. Research on Path and Sequence Planning for Multi-Cabin Onboard Transportation of Large Cruise Ships. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yue, X. Distributed Spot Welding Task Allocation and Sequential Planning for Multi-Station Multi-Robot Coordinate Assembly Processes. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 127, 5233–5251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, N.; Fang, J.; Yuan, J.; Liu, X. 3MSP2: Sequential Picking Planning for Multi-Fruit Congregated Tomato Harvesting in Multi-Clusters Environment Based on Multi-Views. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 225, 109303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Hong, D.; Chen, Z.; Changhai, M.; Weiwen, L.; Wang, J. Disassembly Sequence Planning of Waste Auto Parts. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2021, 71, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, B.; Wang, Z.; Zou, L. An Improved PSO Algorithm for Smooth Path Planning of Mobile Robots Using Continuous High-Degree Bezier Curve. Appl. Soft. Comput. 2021, 100, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, T.; Yue, Z.; Jiao, Y.; He, Z. A Hybrid Strategy-Based GJO Algorithm for Robot Path Planning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Xiang, C.; Xi, J.; Chen, J.; Lei, J.; Giernacki, W.; Liu, M. Path Planning for Dual UAVs Cooperative Suspension Transport Based on Artificial Potential Field-a* Algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 277, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Song, D.; Tang, W.; Ma, J.; Li, J. Auxiliary Support Path Planning for Robot-Assisted Machining of Thin-Walled Parts with Non-Uniform Thickness and Closed Cross-Section Based on a Neutral Surface. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 147, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.-N.; Tang, W.-C.; Zhao, Y.-N.; Zhong, Y.-G.; Ma, J.-W. Convolution-Based Velocity-Smoothing Principle and Its Application to Real-Time Parametric Curve Interpolation. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 23443–23454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhang, J.; Yao, S.; Liu, D.; Men, X. Tower Crane Path Planning Based on Improved Ant Colony Algorithm. J. Meas. Sci. Instrum. 2024, 15, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Meng, G.L.; Xu, Y.M.; Luo, H.T. A Geometrical Path Planning Method for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle in 2D/3D Complex Environment. Intell. Serv. Robot. 2018, 11, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.C. Hagen-Rothe Convolution Identities Through Lagrange Interpolations. Discret. Math. Lett. 2023, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, W.B.; Wang, W.H.; Gao, C. Trajectory Optimization with Obstacles Avoidance Via Strong Duality Equivalent and Hp-Pseudospectral Sequential Convex Programming. Optim. Control Appl. Methods 2022, 43, 566–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, H.C.; Wang, J.W.; Wang, H.B. Optimal Path Planning for Autonomous Berthing of Unmanned Ships in Complex Port Environments. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 303, 117641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uras, T.; Koenig, S.; Hernández, C. Subgoal Graphs for Optimal Pathfinding in Eight-Neighbor Grids. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Third International Conference on International Conference on Automated Planning and Scheduling, Rome, Italy, 10–14 June 2013; AAAI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 224–232. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Y.B.; Fan, S.R.; Feng, X.L. Research on UAV 3D Path Planning with Improved A-Star Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 17th International Conference on Advanced Computer Theory and Engineering (ICACTE), Hefei, China, 13–15 September 2024; pp. 334–338. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, K.W.; Zeng, J.; Zhu, H.J.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, W. Design and Strength Analysis of Cabin Unit Entry Schemes for Polar Expedition Cruise Ships. Mar. Eng. 2021, 43, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.