1. Introduction

Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC) is a unique marine energy technology with a long history of development onshore and offshore, yet widespread growth has been slow, in large part due to high costs [

1]. Pathways to widespread OTEC energy production indicate the potential to bring its levelized cost of energy down to levels that rival solar and wind energy on land, with 24/7 power production [

2]. Developing multi-use OTEC systems for islands and remote communities could help meet the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals #7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and #13 (Climate Action).

OTEC plants can be constructed onshore, or offshore on floating barges or vessels that are anchored to the seabed or possibly free-floating. OTEC is a low-efficiency heat exchange process (as compared to other thermal engines), with theoretical efficiencies ranging from 4.7% for open-cycle OTEC systems [

3] to 6.7% for closed-cycle systems [

4]. These low efficiencies require the pumping of extremely large quantities of seawater from depth (generally 800–1000 m) and a sizable plant, resulting in high capital costs for OTEC projects. These capital requirements have prevented OTEC from becoming established as a commercial energy source to date, with commercial-scale development of the first OTEC plants ranging from USD 500M to 800M [

5]. Cost estimates for the levelized cost of energy have been estimated from plants that were designed in the 1970s through the present day, and range from 0.94 to 0.50 USD kW/h for small onshore plants, while larger offshore plants are likely to be in the range of 0.44 to 0.18 USD kW/h [

6], with decreases in costs expected as more OTEC plants are developed [

5]. Most uses for OTEC could be satisfied with a closed-cycle system, using a working solution of ammonia or other organic compounds [

7]. Open-cycle OTEC, while less efficient than closed-cycle, uses seawater as the working fluid and can be paired with a desalination system to produce freshwater [

8]. OTEC’s use of seawater and infrastructure allows for additional value streams that could help to reduce the cost of power generation and provide much-needed services and products in the tropical islands and coastal regions where the process is viable.

Cold ocean water can also be used from shallower depths than OTEC to provide seawater air conditioning (SWAC). SWAC draws cold water from the ocean to run through a chiller system on land, replacing electricity to cool and reduce humidity in buildings, industrial complexes, and aquaculture ponds [

9]. In many tropical islands, particularly those focused on tourism, air conditioning can account for up to 40% of the energy load [

9]. SWAC systems can also be used in conjunction with OTEC.

Globally, many islands in tropical and sub-tropical areas suffer from high energy costs, unreliable electrical supplies, poverty, and underemployment, which are all exacerbated by climate change. Typically, the electricity for these islands is generated from the combustion of imported diesel fuel, with some additional capacity from renewable energy sources such as solar or wind [

10]. The cost of electricity on islands and remote coastal communities is often considerably higher than on the mainland and more accessible coastal areas. For example, the cost of electricity on the island of Hawaii (referred to as the Big Island) in 2024 ranges from 39.73 to 52.79 cents (US) per kWh [

11], as compared to average electrical costs on the US mainland for 2025 that range from 13.27 to 17.01 cents (US) per kWh [

12]. Many tropical islands, particularly in the Pacific and Indian oceans and the Caribbean Sea, are volcanic in origin, with rapidly dropping bathymetry, bringing cold deep ocean water to within a few kilometers of shore. The need for a stable renewable energy source and the proximity to deep water make these islands prime candidates for OTEC and SWAC development [

13].

In addition to providing baseload power, an OTEC system has the potential to provide food and clean water and to enable potential new industries [

14]. The cold nutrient-rich deep seawater needed for OTEC’s power cycles has many promising byproducts and applications, including SWAC for residential and industrial cooling, support for aquaculture farms (e.g., seaweed, shellfish, and finfish), freshwater from desalination, power to extract critical minerals from seawater, and e-fuels such as ammonia and hydrogen. These value-added products and services have the potential to lower the overall cost of power production for an OTEC system, assisting in bringing the necessary capital to establish this as a widespread renewable energy source from the sea. While few studies have examined purpose-built or multi-use OTEC systems, there are examples such as the use of cold deep water associated with the 100 kW OTEC plant on Kumejima Island in Okinawa, Japan, for enhancing aquaculture [

15]. There are also several plans for multi-use OTEC plants including the proposed PROTECH plant in Puerto Rico [

16], the STARREPS project in Japan that aims to assist with multiple uses of OTEC [

17], and the Bluerise project, aimed at similar needs in the Dutch Caribbean [

18]. The analysis by [

19] has provided the most extensive analysis for a proposed multi-use OTEC site for coastal communities in Mexico.

The United States has a sizable number of volcanic islands in the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean that could be candidates for OTEC and SWAC development. This paper explores the feasibility of developing OTEC systems for multiple end uses and examines the compatibility among the end uses that will drive appropriate technology configurations. A hypothetical use case for multiple applications of OTEC was developed off Hawaii, considering the available energy resources, potential environmental effects and mitigation, and the future use and value of OTEC development. Recommendations for further research and vital knowledge gaps are also explored.

2. Materials and Methods

The methods used for this research include a compatibility analysis for multiple uses of an OTEC platform, based on design considerations used for each configuration of power production with additional applications. A use case models the OTEC thermal resources available at a site off the Big Island of Hawaii, combined with cold water discharge placement to avoid deleterious environmental effects, and interaction with the community directly affected by the existing OTEC plant on the site.

A range of designs were developed for a ~1–5 MW onshore OTEC plant and a ~10–100 MW offshore OTEC plant. Onshore OTEC plants of 1–5 MW would meet the needs for island grid integration or early demonstration projects, while 10–100 MW is a desirable target for commercial offshore plants. These designs cannot be considered as engineering designs for the purposes of development, but rather as a means to examine the feasibility of combining OTEC power production with other added-value end uses. The main criteria driving the designs were based on the gross power output, to determine the volume of water needed for OTEC power production, allowing for additional uses. The simplified designs were focused on meeting the needs of multiple end uses based on the requirements of each, as available from the existing literature [

4,

14,

20]. It was assumed that initial OTEC developments will occur onshore, with larger plants moving offshore in the future. The end uses examined include SWAC for residential and industrial purposes, support for aquaculture, desalination of seawater to produce freshwater, critical mineral extraction from seawater, and production of e-fuels including ammonia and hydrogen. The most appropriate plant location (onshore or offshore) was examined for each end use.

Based on the feasibility of combining OTEC power production with other value-added end uses, a simplified compatibility analysis was carried out to determine which end uses might be compatible with onshore and offshore platforms, and which could be carried out in conjunction with other uses. Potential environmental effects and community attitudes towards OTEC were not used as parameters in the compatibility analysis but were examined as important and necessary aspects of developing OTEC for power and other uses. Key missing information needed for further development of OTEC plants was examined and recommendations made for filling those gaps.

Throughout, we have assumed a closed-cycle OTEC plant, except when desalination is considered as an additional end use of the system, when an open-cycle plant is assumed.

A use case was created to explore the development of a multi-use OTEC plant in the location currently occupied by the small-scale OTEC plant at the Natural Energy Laboratory of Hawaii Administration’s (NELHA) Hawaii Ocean Science and Technology Park (HOST) Park in Kona, Hawaii. A portion of the land surrounding the OTEC plant is leased by the State of Hawaii to small companies to take advantage of the facilities to incubate, innovate, and improve Hawaii-based shoreline-dependent enterprises. A significant number of the NELHA tenant companies use the deep ocean water brought ashore as part of the OTEC operation, using the water for cooling and other uses.

The available thermal resources for OTEC development were examined using a 3D open-source ocean model—Semi-implicit Cross-scale Hydroscience Integrated System Model (SCHISM) v5.10 [

14]. SCHISM was applied to the domain around the Hawaiian Islands and validated with data from Argo floats and satellites. Potential environmental effects of an OTEC plant generating power were examined and mitigation for the most significant explored. A new cold water return model was developed to evaluate the effect of cold water discharge on the thermal dynamics and marine environment near the location of the proposed discharge pipes for both the onshore and offshore OTEC plant, using a discharge depth of 50–120 m, to mitigate the most important potential effect. The methodology of the resource assessment and cold water return modeling for the Kona area can be found in [

21].

A site visit to the tenants at NELHA provided rich anecdotes of their dependence on the use of cold deep water for their operations. The tenants who have access to the site and the deep cold ocean water brought onshore from the OTEC intake pipe were subsequently surveyed to understand their attitudes towards OTEC, access to the deep water, and further development of OTEC at the NELHA site. The survey consisted of five questions that explored how aware and comfortable NELHA tenants were with the availability and use of deep ocean water at the site, and their attitudes towards expansion of the NELHA OTEC site to provide more power and deep ocean water for use by the tenants. All 40 NELHA tenants were included in the survey, but 14 were determined not to interface with the cold deep ocean water or the OTEC plant. Six of the remaining 26 tenants responded to the survey.

Additional end uses of an OTEC platform were examined, but due to lack of operational information, these remain speculative and require more examination.

3. Results

An examination of the configurations needed to supply power, as well as additional end uses, resulted in a series of design considerations for onshore and offshore OTEC plants.

3.1. Design Considerations

Onshore OTEC systems rely on the pumping of cold deep water and warm near-surface water to shore through pipes laid along the seafloor at the appropriate depth. The water piped to shore is run through the OTEC plant, and other processes as appropriate, then returned to the ocean through a single mixed discharge or separate cold and warm water discharge pipes (

Figure 1). These systems are likely to be ~1–5 MW.

As larger, commercial OTEC systems are developed, they are more likely to move offshore, with larger power capacity (~10–100 MW) on floating platforms (

Figure 2). Deep cold water and warm surface water, as well as discharge water, will be pumped by pipes connected to the floating platform. Power from floating OTEC platforms will be distributed to land through a subsea power export cable.

The design considerations developed for OTEC and the range of end uses (SWAC, aquaculture support, desalination, critical mineral extraction, and e-fuel generation) were examined individually and in tandem with other compatible uses. The appropriate OTEC cycle was used to meet each end use, with all uses focused on closed-cycle OTEC except for desalination, which requires an open-cycle plant. Adding end uses in addition to OTEC power will require design changes, which may include resizing of intake and discharge water pipes, changing the sequence of water intake and discharge, and redesign and resizing of the onshore facility or floating platform. In addition, the specific additional end uses will require specialized designs that interface with the OTEC plant, water piping, and other features.

3.1.1. Seawater Air Conditioning (SWAC), Industrial Cooling, and District Cooling

Deep cold ocean water can be used for cooling and humidity reduction in buildings, in place of electricity and conventional air conditioning. The temperature differential to achieve SWAC does not need to be as large as that for a functional OTEC system, potentially allowing the use of cold water brought from depth to be used prior to, or after, running the water through an OTEC heat exchange process. Typically, SWAC is used for residential use, or in cooling industrial processes (industrial cooling), or in buildings and residences in clusters (district cooling). While cold seawater can be run through piping in buildings or residences, most commonly the deep cold water would be used in a heat exchange process at a central location, providing cooling for freshwater circulated through a building, structure, or tank (

Figure 3). A SWAC plant, with or without OTEC in tandem, would be most useful onshore, as piping the cold water from an offshore plant would add additional complexity and cost.

Adding SWAC or other cooling to an OTEC system creates the challenge of rerouting cold water from the system, either before its use in OTEC power generation, or after power production but before discharge. Each of these options presents unique challenges. Rerouting cold deep water before power production decreases the amount of power that can be generated. Rerouting water after power production does not affect the power but requires additional piping. Also, if the post-power-production cold water is not sufficiently cold, it may be used for cooling but may be insufficient to reduce humidity—a key requirement for many SWAC systems. Typically, temperatures of 8–12 °C are needed for dehumidification.

3.1.2. Use of Deep Ocean Water for Aquaculture Enhancement

Surface tropical waters are depleted of the essential nutrients for phytoplankton growth. The deep ocean water brought to the surface for exchange with warm surface waters as part of the OTEC process is rich in essential dissolved nutrients, including nitrate, nitrite, phosphate, and silicate, as well as organic and inorganic micronutrients. At first glance, this pumping of nutrient-rich deep water appears to be an excellent opportunity to potentially enhance phytoplankton (microalgae) and seaweed (macroalgae) growth in aquaculture ponds or raceways. However, the carbon load in deep seawater may present a significant barrier to this use. There are two options for using the deep-water nutrients for algal growth: (1) ensuring that the deep water is never exposed to the atmosphere but rather discharged directly after the nutrients have been taken up by the micro- or macroalgae, or (2) scrubbing the carbon after the use of the nutrients for algal aquaculture. The former is not very practical as most micro- and macroalgal cultures are carried out in open ponds, tanks, or raceways. Capturing the carbon from the free surfaces would present a large technical and economic challenge. The second method, carbon scrubbing, may be feasible technically, but again at great cost.

It is clear from discussions with aquaculture experts that deep cold ocean water plays a critical role in cooling aquaculture ponds, raceways, and tanks, allowing onshore aquaculture of microalgae, macroalgae, and larval shellfish to thrive in hot tropical areas (

Figure 4). This process is distinct from that of using the deep water nutrients for algal growth stimulation. The deep water for cooling aquaculture installations would be used in a closed system, with the water returned to depth through the discharge pipes, avoiding contact with the atmosphere.

3.1.3. Seawater Desalination

Open-cycle OTEC plants can be fitted with a desalination plant that uses the output from the OTEC condensation process. Open-cycle OTEC plants are less efficient than closed-cycle OTEC plants, resulting in the need for larger turbines and heat exchangers to generate sufficient power and desalinated water. Although there is no theoretical maximum size to an open-cycle plant, the practicalities of turbine and heat exchanger sizes lead experts to believe that 5 MW is likely the largest open-cycle plant that can be designed and operated successfully [

15]. The amount of process water needed for an open-cycle plant is almost double the volume needed for a similarly rated closed-cycle plant [

15].

Desalination is most likely to be associated with an onshore OTEC plant to reduce the complexities of pumping freshwater to shore (

Figure 5). Future large floating OTEC platforms, with onboard crew, could benefit from an onboard open-cycle operational plant for freshwater production.

The major challenges of adding a desalination plant to an onshore OTEC system are the need to increase the footprint of the site to accommodate the larger heat exchangers and turbines of an open-cycle OTEC system, the additional cost and maintenance complexity of adding a desalination plant, and the need for piping and other infrastructure to store and distribute the freshwater generated.

3.1.4. Critical Mineral Extraction

All metals and earth minerals found on land are present in dilute forms in the ocean, dissolved in seawater. Mining these elements from seawater requires the movement of large volumes of seawater, which has made their recovery prohibitively expensive in terms of energy using current technology. However, the large volumes of seawater moved as part of OTEC processes could help to initiate critical mineral recovery, using efficient, cost-effective absorbents that scavenge specific elements. Further examination of the critical mineral extraction in conjunction with OTEC can be found in [

22].

Extracting critical minerals from seawater on an OTEC platform at sea will require the addition of an exposure tank to hold the adsorbent material and pipes. The process would consist of diverting volumes of warm water after OTEC power production into the exposure tank and allowing the absorbents to extract the minerals. The tank would then be flushed to release the minerals and re-initiate the absorbent capabilities. In addition to the exposure tank, infrastructure will also be needed to pump and pipe the water from the exposure tank to the discharge pipes, as well as engineering structures and processes to wash the adsorbed minerals from the material and refurbish the adsorbent for the next round of extraction (

Figure 6).

3.1.5. E-Fuels

As offshore OTEC plants become established, the power generated could be used to create green hydrogen by electrolysis from seawater for storage and transport by specialized vessels. Adding a nitrogen plant to the platform would allow the generation of ammonia (with N

2 separated from the air) as a hydrogen carrier (

Figure 7); specialized ammonia transport vessels are already in use around the world.

The major challenges of adding an e-fuel plant to an offshore OTEC platform include the complexity of storing and using the OTEC-generated electricity at sea, the cost and complexity of operating and maintaining an e-fuel plant, and storing and transporting the e-fuel with the associated docking and lightering facilities on the platform for ships.

The value-added end uses for OTEC power production are summarized in

Table 1.

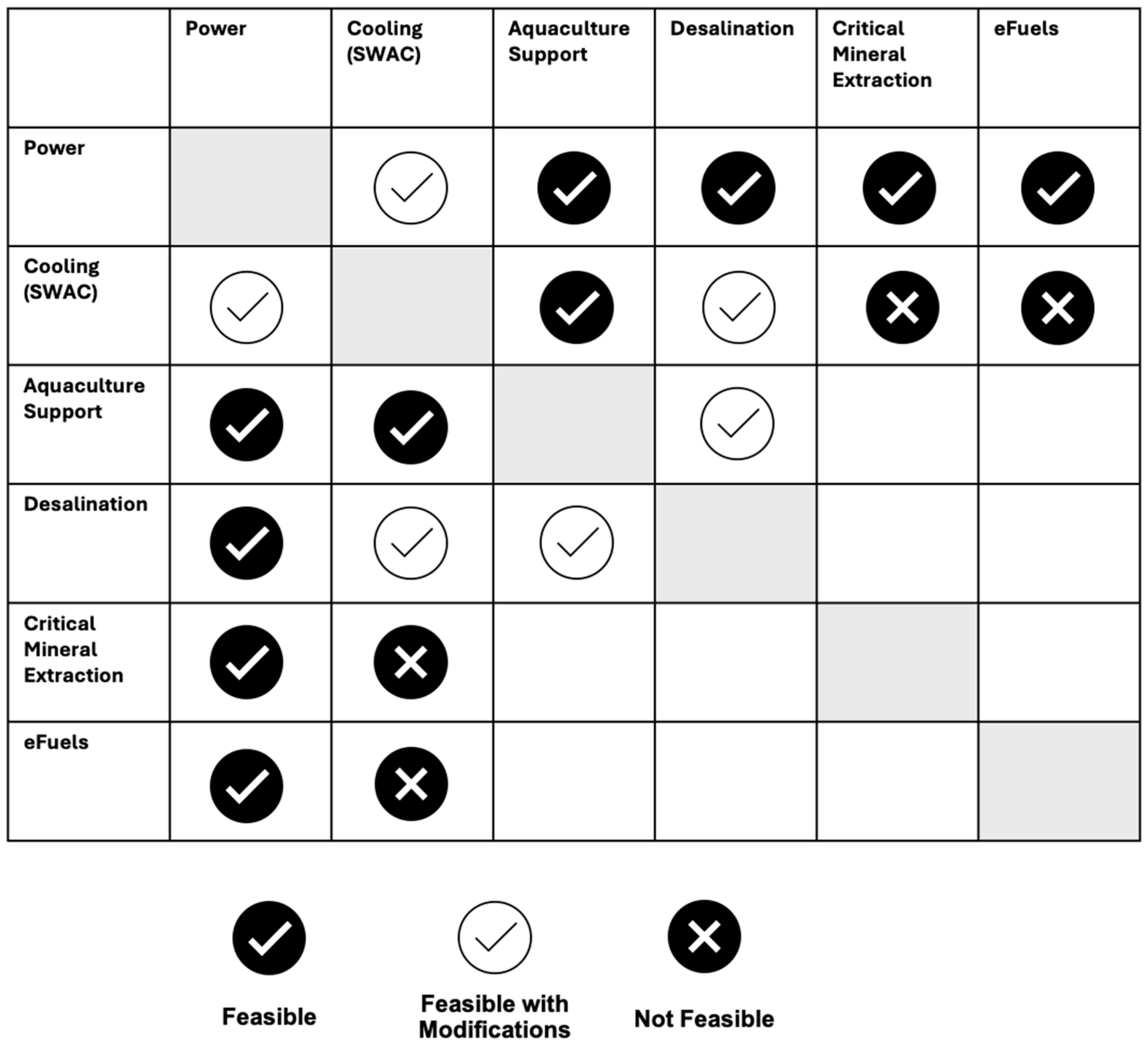

3.2. Compatibility of OTEC End Uses

A compatibility analysis for power production as well as a range of additional services and products examined how the additional use of the OTEC process water or infrastructure may influence the overall performance of the system. These effects may render a particular end use non-viable or require mitigation through design or operational changes to the OTEC system, such as changing the order in which the seawater is used (before or after the heat exchange process), resizing of intake or discharge pipes, or resizing the project’s footprint. The viability and potential combinations of end uses are illustrated in

Figure 8. The requirements, challenges, and opportunities for each end use in conjunction with OTEC power are explored in

Table 2.

To illustrate the outcome of the compatibility analysis, the amount of water that must be pumped to carry out both the OTEC heat exchange process and the additional end use is listed in

Table 3. While most of the additional end uses require little additional water, splitting off the cold deep water for SWAC and other cooling uses before the OTEC process increases the need for cold deep water by ~50%. The lower efficiency of open OTEC systems further increases the need for cold and warm water.

3.3. Use Case: Multi-Use OTEC in Hawaii

A use case of a multi-use OTEC platform was explored for the site of the current NELHA OTEC plant in Kona, Hawaii (

Figure 9); this use case would add to the present small OTEC plant, rather than replace it. The thermal resources were characterized to determine whether there was sufficient energy available to harvest through OTEC [

21]. The thermal resources available to generate power were shown to be adequate year-round for a large onshore or offshore floating 100 MW OTEC plant (

Figure 9). Ten-year (2012–2021) model results showed that the mean OTEC power is over 80 MW at a water depth of 500m. OTEC power increases with depth and is consistently above 100 MW (

Figure 10a) with a 95% probability (

Figure 10b) when water depth is greater than 1000 m. The annual energy production (AEP) by a 100 MW OTEC plant reached up to 1.2 TWh/year in areas where water depth is greater than 1000 m (

Figure 10c). Additional details on the model development, validation, and resource characterization are available in [

23].

3.3.1. Environmental Concerns

The major environmental effects that could be attributed to development and operation of an OTEC plant at NELHA focus largely on the potential effect of returning large volumes of cold deep ocean water to the surface waters around the site. The threats of temperature shock of ambient marine biota and destabilization of the local water column are likely to be the dominant concerns [

24,

25,

26,

27] expressed in the process of permitting an onshore or offshore OTEC plant. Additional concerns include the potential to entrain rare deep-sea biota with the deep water pipe, the release of toxic chemicals including ammonia and petroleum-based lubricants, and the need for care to not disturb nearshore habitats like coral reefs. Experience at the NELHA OTEC plant and the Okinawa OTEC Demonstration Facility in Kumejima, Japan, to date suggest that the entrainment of deep-sea organisms will be exceedingly rare [

18], while potential releases of toxic chemicals would be addressed with standard hazardous waste management plans. Careful siting of OTEC and SWAC plants, combined with horizontal directional drilling under reefs and sensitive areas can preserve these vulnerable habitats. The return of cold water to the ocean remains the major environmental concern.

A cold water return module was developed, nested within the resource characterization model for the NELHA area, to examine the potential effects and depth requirements for returning cold water to the ocean, after the OTEC heat exchange process [

23]. Previous modeling efforts that have examined discharge depths for OTEC plants in Martinique [

25] and Hawaii [

28] suggest cold water discharge depths between 70 m and 500 m. Accounting for ambient light levels and the mixed layer depth off Kona, the preferred depth falls between 90 m and 115 m [

24].

The volume of cold deep seawater that is brought to the surface for OTEC processes exceeds that of the warm water used for heat exchange by a ratio of approximately two to one. The process water must be returned to the ocean after the heat exchange process: the cold deep water is likely to be in the order of 6–10 °C warmer than at the start of the process, and the warm water cooler by 3–5 °C. The processed water can be returned separately or as a combined return. The temperature of the warm water after OTEC processing is not very different from ambient water and can be returned to near-surface waters or through a combined return discharge.

To avoid environmental concerns, the cold-water return (mixed with the returning warm water) should be discharged at an intermediate depth where the density of organisms is lower than in near-surface waters, and the water will sink to reach a constant density with the ambient water. This depth is generally considered below the seasonal thermocline (50–100 m in most tropical locations) but above the permanent thermocline (200+ m). To assist in determining the appropriate discharge depth for a mixture of cold and warm water, a numerical model was used to study the potential effects of the cold water return on the ambient ocean environment.

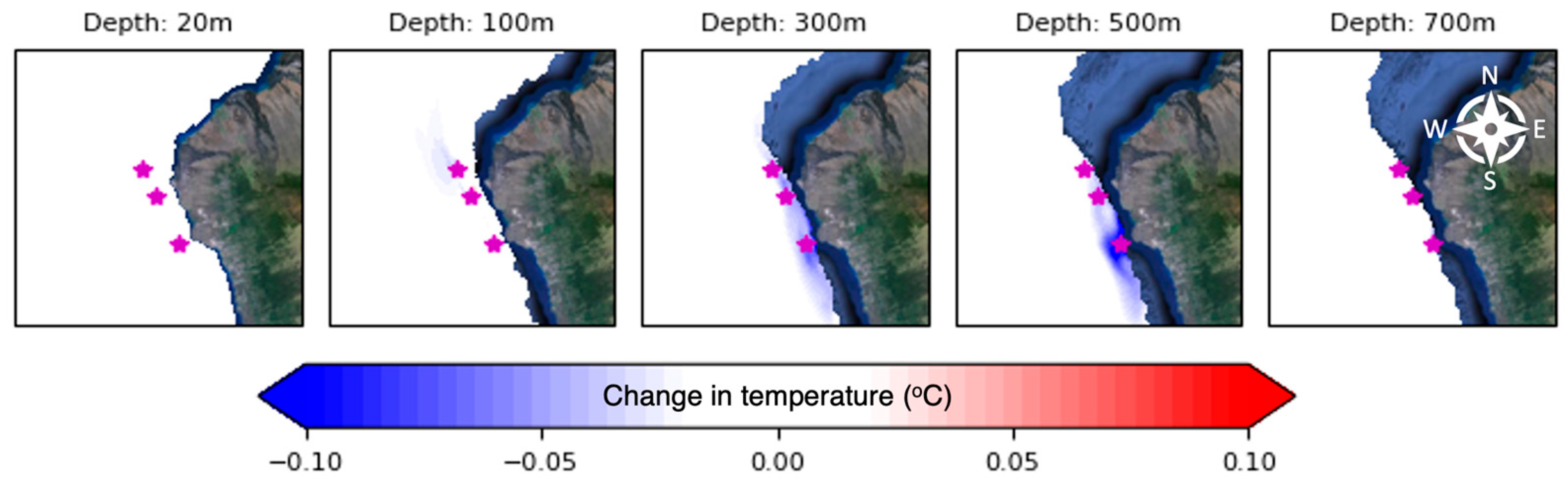

Potential changes in the local water column will depend on the quantity of water discharged, which is determined by the size of the OTEC plant. For the purposes of this study, three 100 MW OTEC plants were considered with three separate discharge pipes, at a constant rate of 300 m

3/s at 100 m depth (

Figure 11). The cumulative discharge from these three plants is much larger than is anticipated for the Kona area, or other tropical islands. The larger plants used in this analysis were chosen to ensure that a change in the oceanography could be noted. The earliest commercial onshore or offshore OTEC plants are likely to be smaller than 100 MW, implying that the discharges would be assimilated into the ambient seawater without disruption to the local water column.

The discharge from the three pipes at 100 m depth will allow the discharge water (at 10 °C) to sink and disperse to the depth where the density meets ambient water.

Figure 11 shows the differential in temperature of water (cold water return scenarios minus baseline condition) found at five different depths, due to the addition of the discharge water. The 20 m depth shows no change in temperature as the discharge is deeper and the discharge water is denser than the near-surface water. At 100 m depth (the discharge depth), a small but extremely weak northward plume of colder water is seen in the model, indicating the negligible cold water effect on the ambient water. At 300 m and 500 m depth, a southward plume is clearly observed but the maximum change in temperature is less than 0.1 °C. By 700 m depth, the plume is not observed, indicating that the discharge water is being assimilated at water depths between 500 and 700 m. All changes in temperature are 0.1 °C or less from ambient water. A change in temperature of 3 °C is commonly considered to be the cause of instability in the water column [

25,

29].

3.3.2. Community Engagement and Acceptance

This study could not engage in a meaningful way with the community around NELHA and the Big Island of Hawaii, relying instead on interactions with those most directly affected by the existing and potential future OTEC plants at the site. A site visit by the project team and a follow up survey with the tenants and management of NELHA yielded some insights into the value they place on the OTEC process currently, and their appetite for expansion and development of a multi-use plant.

The online survey asked about the NELHA tenants’ current uses of NELHA deep water, and how they might envision using an expanded site in future. Most respondents work in the aquaculture sector (e.g., breeding and production, and research and development), and one provides venture capital, consulting, and programs for sustainable seafood and other blue economy industries. Another provides public exhibitions on marine animals, education, and policy to support ocean conservation. Survey respondents primarily use the NELHA facilities by leasing lab or office space in the research campus, utilizing surface and deep seawater for aquaculture operations, and utilizing the deep seawater for office cooling (through SWAC). Survey respondents stated that they primarily use the cold, deep seawater available at the facilities to grow microalgae and macroalgae, to mix with surface water to reach optimal temperature conditions for fish broodstock and shellfish larval culture, and to provide air conditioning for office spaces.

The most significant use of cold deep ocean water includes SWAC for NELHA labs and administrative buildings, and cooling for algae growth and oyster larvae spawning and growth. Several of the tenants stated that they could not profitably operate their businesses without the use of the cooling water, as the price of electricity for cooling purposes is very high in Hawaii. If they had access to renewable energy from a larger OTEC plant, some survey respondents would be interested in using that power, while other respondents were unsure. Some survey respondents would be supportive of expanding the existing onshore plant and/or development of a larger floating OTEC plant offshore. There was some support for additional onshore OTEC facilities but also concerns expressed about additional development based on potential encroachment on the existing shoreline and ancestral grounds. An additional use of OTEC power and deep water noted was the potential for large-scale direct ocean capture of carbon.

4. Discussion

This project explored several potential scenarios for multiple uses of an OTEC platform, based on the compatibility of the end uses. This examination of compatibility analysis envisioned multiple end uses for OTEC in addition to power production, taking into account the need to minimize environmental effects and ensure that the end uses are of value to communities in which OTEC projects might be developed. The most viable appear to be using OTEC to generate power with cooling on a closed-cycle OTEC platform and OTEC power generation with desalination on an open-cycle OTEC platform. Small experimental OTEC plants have been developed and operated for these uses at NELHA in the United States; in Kumejima, Japan; in the dry Indian islands (Lakshadweep) in the Arabian Sea; and in laboratories in the United States, United Kingdom, India, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, and elsewhere [

30].

The outcomes of the analyses indicate that there is ample thermal differential between the warm surface water off Kona to operate an OTEC plant. This assessment is based on a new resource characterization model applied to the domain and validated with oceanographic and satellite data [

31,

32,

33,

34]. As the islands of the Hawaiian archipelago are barely within the tropical zone, this bodes well for tropical islands in the Pacific Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and other parts of the world oceans within the tropics. The design requirements for each use were considered within the context of assuring that OTEC power production remained feasible, and preliminary designs for each identified use were drawn. Additional analyses examined the potential for using the high levels of dissolved nutrients present in deep ocean water for enhanced growth of algae; these analyses indicated that this was not a practical or reasonable pathway to pursue without extraordinary technological additions and costs being added to the OTEC plant.

The major environmental concern for the development of an OTEC plant revolves around the need to return the deep cold water to an appropriate depth after the OTEC heat exchange process, to avoid creating an unstable localized oceanographic environment and to protect surface water biota from shock. A new open-access OTEC return model was created and linked to the resource characterization model to demonstrate the depth and location where the discharge water should be directed, based on a range of OTEC plant sizes. The model supports the conclusion that the discharge of OTEC process water at a depth of 100 m off Kona is unlikely to substantially alter the stability of the water column. It should be noted that a near-field plume model was not integrated to simulate the initial dilution of the cold water, which was simply discharged into a large model cell and assumed to be fully mixed and diluted in the grid cell. Therefore, the cold-water plume model results tend to underestimate temperature difference in the initial dilution zone near the discharge point. However, given the relatively small flow rate (300 m3/s) and negligible temperature difference (<0.1 °C), there is strong evidence that the conclusions based on the model results will hold in reality. The outcome shows that for OTEC plants considerably larger than those currently contemplated for coastal and remote island areas, the discharge water can be effectively handled to avoid adverse outcomes. The output of this model can be tailored for other locations and used to assist in the design of the piping and pumps needed for OTEC water uptake and discharge.

There were no concentrated interactions with the local community around the NELHA plant, so the acceptance of a larger and functional OTEC plant on the site could not be adequately judged. In place of real community engagement, the needs of many of the tenants and management of the NELHA site were explored to gauge their knowledge, interest, and long-term vision for the existing (and possible future) OTEC plant at NELHA. Overall, there appears to be interest and commitment to the value of the deep OTEC water and future potential power and other services from the plant.

Following the analysis of each potential use in addition to power production, the challenges of combining each use and their compatibility were examined. The most obvious compatibilities are with those uses best suited for a floating offshore platform (critical mineral extraction and e-fuels production) versus those suited for an onshore system (cooling and desalination). Within those categories, there are no obvious technical conflicts for critical minerals and e-fuels, but practical considerations such as space on a floating platform and capital costs may override their combined use. SWAC and other cooling uses, including supporting aquaculture in tropical climates on land, are all compatible with OTEC power production, while desalination requires an open-cycle plant that is considerably less efficient than the closed-cycle plant considered best for power and cooling, making the addition of desalination less attractive when combined with other uses. While adding one or more end uses to OTEC power production adds complications of design and operation, it should be noted that more than two end uses might also be feasible (e.g., the use of cooling water for aquaculture and for residential use in addition to power production, or desalination of seawater with cooling for residential uses with power production).

Every aspect of adding uses beyond power to an OTEC platform requires a deeper level of investigation, led by a deep dive into the economics of developing multiple uses for OTEC that are fit for purpose. A recent study has shone some light on OTEC development costs, but the lack of empirical evidence from extensive commercial plant operations leaves many unanswered questions [

5]. The studies with the greatest urgency to determine the feasibility of multiple uses of OTEC, and the most urgent steps needed in each, include the following:

Understanding the multiple uses of OTEC platforms through the development of a pre-commercial or commercial OTEC plant is needed, around which further investigations and experiments can be focused. As new OTEC demonstration plants are deployed, studies of the potential addition of value-added end uses should be carried out using the specifics of the new plants.

The economics of OTEC and the individual additional uses need considerable investigation, but much of this work will depend on the availability of data from functional OTEC plants. Data must be gathered from each newly commissioned and operating OTEC plant to add to the existing knowledge.

Further investigations are needed into the design needs of deep cold water for cooling taken before the use of the cold water in the OTEC heat exchange process. These include how the diversion of water will affect the power production, whether the two processes (cooling and power production) must always run at the same rates, and whether resizing the cold-water uptake pipe will allow the OTEC system to run at its rated capacity.

The limits and design considerations for using cooling water for SWAC, industrial cooling, and cooling support for aquaculture simultaneously need to be understood in addition to implications for power production when cooling water is taken before and after heat exchange. Design considerations for each scenario must be developed as new OTEC demonstration plants are deployed.

Understanding the efficiency and efficacy of using an open-cycle OTEC system in conjunction with a desalination plant is needed. Studies are needed to understand how much power can be generated for a set volume of freshwater produced.

The practicality of placing a critical mineral extraction system and an e-fuels generation system on an offshore OTEC platform must be investigated. These studies must include the basic functions and requirements for each of these operations, and development of lab scale prototypes that simulate water delivery and/or power from an OTEC plant.

High-resolution, long-term model simulations validated with field observations are needed to characterize the OTEC resources and help project siting. The model results that simulate the ambient water temperature by cold water discharge must be validated with field data from an operational OTEC plant.

Regulatory concerns should be investigated that cover the full suite of potential risks of an OTEC plant, in addition to the cold water return effects. Investigations and discussions on potential effects must be carried out with a range of local/regional and federal regulators to determine key issues. In addition, ongoing educational outreach is needed to ensure that permitting is smooth and efficient for future OTEC plants in the United States and elsewhere.

Additional outreach to the Kona community and elsewhere in Hawaii is needed to validate the initial findings of community acceptance and support for OTEC.

The dissemination of these findings and further analysis to other islands in the Pacific and elsewhere are needed to ensure that the range of OTEC potential is realized.

5. Conclusions

This paper examined the feasibility of developing OTEC plants that serve multiple uses, the design considerations needed to achieve these uses that include the placement of a plant onshore or offshore, and compatibility among the uses. The study also explored a use case at the NELHA site by analyzing the thermal resource available around Kona, Hawaii, potential environmental effects, and a limited look at community values, as they might affect OTEC power generation and other end uses.

There is little found in the scientific literature that provides insights into multiple uses of OTEC platforms, although there are suggestions and/or small experimental or laboratory-scale OTEC plants that have explored some additional uses. This study has begun the process of determining what scenarios for multiple uses of OTEC might be feasible, and to consider the opportunities and challenges of each use with OTEC power production, as well as in tandem with other additional uses.

The most promising additional uses of an OTEC plant beyond generating power are the use of the cold deep ocean water for SWAC, cooling of aquaculture tanks and ponds, and industrial cooling from either onshore or offshore closed cycle OTEC. In addition, open-cycle OTEC plants could contribute desalinated water, preferably from shore-based open cycle processes. Offshore closed-cycle OTEC plants seem promising for future processes including critical mineral extraction from seawater and generation of e-fuels. Additional studies are needed to determine the technical feasibility of adding each additional end use to OTEC power production. The economic viability must also be evaluated to determine which additional end uses will provide added value and help to lower the capital and operating costs for OTEC development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C., H.F., C.R. and Z.Y.; methodology, A.C., C.R., K.P. and Z.Y.; software, K.P. and Z.Y.; validation, K.P. and Z.Y.; formal analysis, A.C., C.R., K.P. and Z.Y.; resources, A.C.; data curation, K.P. and Z.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C. and Z.Y.; writing—review and editing, A.C., H.F., C.R. and Z.Y.; visualization, K.P. and Z.Y.; supervision, A.C.; project administration, A.C.; funding acquisition, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by a contract to Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, operated by Battelle for the United States Department of Energy under contract DE-AC05-76RL01830.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (protocol #2019-15 (Initial approval date: 8 April 2019)).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Curtis Anderson in drafting the design figures and Fadia Ticona Rollano in analyzing data on the resource characterization. We would also like to thank the participants in the NELHA survey, as well as Makai Engineering staff, Neil Sims of OceanERA, and the administration of NELHA, for discussions that helped shape this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aresti, L.; Christodoulides, P.; Michailides, C.; Onoufriou, T. Reviewing the Energy, Environment, and Economy Prospects of Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC) Systems. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 60, 103459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocean Energy Systems. White Paper on OTEC; Ocean Energy Systems (OES): Lisbon, Portugal, 2021.

- Liu, W.; Xu, X.; Chen, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y. A Review of Research on the Closed Thermodynamic Cycles of Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.-J.; Shin, S.-H.; Chun, W.-G. A Study on the Thermodynamic Cycle of OTEC system. J. Korean Sol. Energy Soc. 2006, 26, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ocean Energy Systems (OES). Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC) Economics: Updates and Strategies; Ocean Energy Systems (OES): Lisbon, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vega, L.A. Economics of Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC): An Update. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 3–6 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nakib, T.H.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Rahim, N.A.; Habib, M.A.; Adzman, N.N.; Amin, N. Global Challenges of Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion and Its Prospects: A Review. J. Ocean Eng. Mar. Energy 2025, 11, 197–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liponi, A.; Baccioli, A.; Vera, D.; Ferrari, L. Seawater Desalination through Reverse Osmosis Driven by Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion Plant: Thermodynamic and Economic Feasibility. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 213, 118694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Renewable Energy Opportunities for Island Tourism; International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA): Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gatta, F.M.; Geri, A.; Lauria, S.; Maccioni, M.; Palone, F.; Portoghese, P.; Buono, L.; Necci, A. Replacing Diesel Generators With Hybrid Renewable Power Plants: Giglio Smart Island Project. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawaiian Electric Average Price of Electricity. Available online: http://www.hawaiianelectric.com/billing-and-payment/rates-and-regulations/average-price-of-electricity (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Minasian-Koncewicz, S.U.S. Electricity Rates by State: A Comprehensive Analysis (2025). Available online: https://www.thisoldhouse.com/electricity/electricity-rates-by-state (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Ticona Rollano, F.; García Medina, G.; Yang, Z.; Copping, A. Resource Assessment of Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion in Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands. Renew. Energy 2025, 246, 122907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, J.; Sierra, S.; Ibeas, A. Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion and Other Uses of Deep Sea Water: A Review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.; Okamura, S.; Yasunaga, T.; Ikegami, Y.; Ota, N. OTEC and Advanced Deep Ocean Water Use for Kumejima: An Introduction. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2022—Chennai, Chennai, India, 21–24, February 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Puerto Rico. PROTECH Puerto Rico Ocean Technology Complex Proposed Roadmap for Development; Government of Puerto Rico: San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2020.

- Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM) Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development (SATREPS). Available online: https://dvcai.utm.my/satreps/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Blokker, R. Bluerise—Ocean Thermal Energy Technology and Project Development. In Proceedings of the 2nd Regional District Cooling Technology Conference in Latin America and the Caribbean, Panama City, Panama, 26 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tobal-Cupul, J.G.; Garduño-Ruiz, E.P.; Gorr-Pozzi, E.; Olmedo-González, J.; Martínez, E.D.; Rosales, A.; Navarro-Moreno, D.D.; Benítez-Gallardo, J.E.; García-Vega, F.; Wang, M.; et al. An Assessment of the Financial Feasibility of an OTEC Ecopark: A Case Study at Cozumel Island. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, S.; Giugno, A.; Sorzana, G.; Lopes, M.F.P.; Traverso, A. Techno-Economic Analysis of Multipurpose OTEC Power Plants. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 113, 03021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Yang, Z.; Copping, A.; Rollano, F.T. A High-Resolution Modeling Study on the Influence of Thermal Gradient Variability on Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion Resources; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, E.; Anderson, C.; Copping, A.; Subban, C. Ocean Thermal Energy-Powered Seawater Mining: A Feasibility Assessment. 2026; In preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.; Yang, Z.; Copping, A.E.; Rollano, F.T. A Modeling Study of Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion Resource and Potential Environmental Effects around Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. Renew. Energy 2025, 253, 123616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comfort, C.M.; Vega, L. Environmental Assessment for Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion in Hawaii: Available Data and a Protocol for Baseline Monitoring. In Proceedings of the OCEANS’11 MTS/IEEE KONA, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 19–22 September 2011; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Giraud, M.; Garçon, V.; de la Broise, D.; L’Helguen, S.; Sudre, J.; Boye, M. Potential Effects of Deep Seawater Discharge by an Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion Plant on the Marine Microorganisms in Oligotrophic Waters. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 693, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajagopalan, K.; Nihous, G.C. Estimates of Global Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC) Resources Using an Ocean General Circulation Model. Renew. Energy 2013, 50, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, G.; Felix, A.; Mendoza, E. A Review on Environmental and Social Impacts of Thermal Gradient and Tidal Currents Energy Conversion and Application to the Case of Chiapas, Mexico. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 7791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandelli, P.; Rocheleau, G.; Hamrick, J.; Church, M.; Powell, B. Modeling the Physical and Biochemical Influence of Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion Plant Discharges into Their Adjacent Waters; MAKAI OCEAN ENGINEERING, INC.: Waimanalo, HI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bordbar, A.; Georgoulas, K.; Dai, Y.M.; Michele, S.; Roberts, F.; Carter, N.; Lee, Y.C. Waterbodies Thermal Energy Based Systems Interactions with Marine Environment—A Review. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 5269–5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocaen Energy Systems (OES). Using Sea Water for Heating, Cooling, and Power Production; Ocean Energy Systems (OES): Lisbon, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lellouche, J.-M.; Greiner, E.; Le Galloudec, O.; Garric, G.; Regnier, C.; Drevillon, M.; Benkiran, M.; Testut, C.-E.; Bourdalle-Badie, R.; Gasparin, F.; et al. Recent Updates to the Copernicus Marine Service Global Ocean Monitoring and Forecasting Real-Time 1/12° High-Resolution System. Ocean Sci. 2018, 14, 1093–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Moorthi, S.; Wu, X.; Wang, J.; Nadiga, S.; Tripp, P.; Behringer, D.; Hou, Y.-T.; Chuang, H.; Iredell, M.; et al. The NCEP Climate Forecast System Version 2. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 2185–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA. GHRSST Level 4 MUR Global Foundation Sea Surface Temperature Analysis (v4.1); NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Wong, A.P.S.; Wijffels, S.E.; Riser, S.C.; Pouliquen, S.; Hosoda, S.; Roemmich, D.; Gilson, J.; Johnson, G.C.; Martini, K.; Murphy, D.J.; et al. Argo Data 1999–2019: Two Million Temperature-Salinity Profiles and Subsurface Velocity Observations From a Global Array of Profiling Floats. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |