Abstract

Complex fluid–particle interactions are ubiquitous in natural environments and engineering applications, with their underlying mechanisms often attributed to interparticle attraction and repulsion. To understand the interaction mechanism between the dual particles, this study examines the setting process of dual particles using the Immersed Boundary-Lattice Boltzmann Method (IB-LBM), with a focus on the effect of the density difference between particles. Two typical configurations—tandem and side-by-side—are considered in the analysis. In the tandem configuration, when , the TP inevitably kisses the LP due to its greater settling velocity, thus initiating the classical drafting-kissing-tumbling phenomenon. As the density of the TP further increases, the attractive effect exerted by the LP on the TP becomes weak. Conversely, when , kissing between two particles is mainly determined by the density of LP. Whether kissing occurs between the two particles depends on a critical value . Although the LP’s attraction to the TP strengthens with increasing LP density, beyond this certain threshold, this attraction becomes insufficient for the TP to catch up with the LP. In a side-by-side configuration with two particles of different densities, their interaction evolves from initial attraction to subsequent repulsion. This phenomenon is not observed in pairs of particles with identical density. Moreover, with increasing density difference between the particles, the attractive effect from the higher-density particle on the lower-density one strengthens, whereas the repulsive interaction between them gradually weakens. When the particle density ratio reaches , the lateral migration of the particles becomes very small; although they still interact with each other, the effect becomes extremely weak. This work systematically elucidates the influence of density disparity on particle interaction, providing insights into understanding more complex multiparticle system dynamics.

1. Introduction

Gravity-driven sedimentation of particles in viscous fluids leads to a complex dynamical system, ubiquitous in both natural phenomena and engineering processes. These include but are not limited to sedimentation in agricultural irrigation systems [1], sedimentation deposition in reshaping riverbed morphology [2,3], seabed scour around pipelines [4], and sediment plumes from deep-sea mining [5]. These aforementioned phenomena are often characterized by the statistical behavior of particle clouds, including their concentration distribution, dispersion range, and settling velocity. However, the inherent complexity of multi-particle systems poses significant challenges for direct observation and theoretical modeling. Despite the complexity, the dynamics of any particulate system are fundamentally governed by two primary types of interactions: fluid–particle and particle–particle forces. A profound understanding of the underlying settling mechanisms is critical for numerous applications in marine science and hydraulic engineering. As such, this study employs a minimalistic approach by investigating a two-particle settling system, which serves as the essential basis for understanding more complex collective behavior. Accordingly, this paper probes a fundamental two spherical particle settling process, thereby providing new insights into mechanisms of complex sedimentation phenomena.

Previously, the sedimentation dynamics of particulate systems have been extensively studied, with focusing on the single particle (e.g., sphere). Cate et al. performed sedimentation experiments with a single sphere, based on particle image velocimetry (PIV) to investigate the settling process at particle Reynolds numbers ranging from 1.5 to 31.9 [6]. Their results provided critical data for validating numerical methods. However, the complexity of the interaction increases markedly with the introduction of a second particle. When two particles are aligned vertically and released, they undergo a Drafting–Kissing–Tumbling (DKT) interaction process, a phenomenon first observed experimentally by Fortes et al. [7]. Their findings established DKT as a fundamental issue regarding hydrodynamic interactions between settling particles. Subsequently, a variety of numerical techniques have been developed and applied to model and analyze this phenomenon. These include the immersed boundary method (IBM) with multi-direct forcing [8], the coupled lattice Boltzmann and fictitious domain approach [9], a network of stiff springs model [10], the Discrete Element Lattice Boltzmann Model [11], the direct numerical simulation [12], coupled approach combining Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics–Volume Compensated Particle Method–Direte Element Method [13]. These works collectively provide valuable insights into understanding the hydrodynamics of particle sedimentation.

Building upon the foundational understanding of DKT, subsequent research has systematically investigated how sedimentation dynamics are influenced by various parameters using two-dimensional (2D) models. For instance, Wang et al. investigated the influence of initial longitudinal distance and particle diameter ratio on the DKT phenomenon of circular particles. The frequency of DKT occurrences between two circular particles was analyzed [14]. Li et al. conducted numerical simulations to study the effects of Reynolds number and initial particle positions on settling behavior [15]. Ghosh et al. employed a 2D model to simulate the DKT process of circular particles with different sizes and densities. The triggering conditions for complete DKT cycles were reported extensively [16]. Panghal et al. explored the DKT behavior of two flexible particles and highlighted the crucial role of fluid viscosity in determining whether kissing occurs between particles [17]. Hui et al. studied the sedimentation of circular particles in non-Newtonian fluids, demonstrating that the power-law index significantly influences horizontal migration during DKT [18]. Subsequently, they also analyzed the DKT behavior of two and three elliptical particles in Bingham fluids [19]. Walayat et al. investigated the settling of dual elliptical particles under thermal convection conditions. The authors found that the heat exchange markedly affected particle settling velocity [20]. Collectively, these studies have significantly advanced our understanding of how geometric and rheological parameters modulate the particle interactions. However, a prevalent and fundamental simplification persists across most of these investigations: the interacting particles are assumed to be under 2D conditions. This assumption effectively imposes a fundamental geometric simplification that limits the applicability of its findings to three-dimensional scenarios, which cannot represent the real natural and industrial scenarios involving particulate mixtures.

The 2D approach has limitations for understanding real particle sedimentation processes, as substantial differences exist between particle settling dynamics in two and three dimensions. Li et al. explicitly reported that significant differences exist between the dynamical behaviors of particle settling in 2D and three-dimensional (3D) scenarios [15]. Notably, repeated DKT phenomena observed in 2D studies have not been detected in 3D investigations [21]. In recent years, numerous researchers have shifted their focus to the study of dual-particle settling in 3D conditions. Zhang et al. developed settling models for irregular particles with varying sphericity and roundness, analyzing the DKT phenomena in such systems [22]. Liao et al. investigated the effects of particle size and initial position on the settling motion of dual spherical particles [23]. Liu et al. combined numerical and experimental approaches to study side-by-side settling of dual spherical particles, demonstrating that the presence of repulsive rather than attractive forces between the particles during sedimentation [24]. Nie et al. investigated the sedimentation of two unequal spheres with different densities in a confined box. A periodic regime during their settling motion within a diagonal plane was observed [25]. Despite this critical shift in dimensionality, a fundamental parameter that has been remained largely unexamined in three-dimensional pairwise interactions: the intrinsic density difference between particles. Existing 3D studies have predominantly focused on particles of identical density with other variables like size. Thus, the isolated role of density contrast—independent of particle geometry or fluid rheology—as the important factor in modulating 3D hydrodynamic attraction and repulsion, its study still remains stagnant.

To bridge this knowledge gap, we examine how intrinsic density difference affects the two classic interaction regimes between spheres: the attractive interaction in tandem configurations [7] and the repulsive interaction in side-by-side configurations [24]. We hypothesize that the density disparity is a primary mechanism that governs the initiation, evolution, and outcome of these interactions. Specifically, we posit that: (1) in tandem settling, the density difference can either accelerate or suppress the DKT phenomenon by altering the drafting force; (2) in side-by-side settling, density contrast can break the hydrodynamic symmetry, thereby either amplifying or reversing the known repulsive trend observed in equal-density pairs. Investigating how the density difference between two particles influences the distinct settling behavior can thus provide deeper insights into understanding the underlying dynamics of particle-particle interactions. In addition, to test these hypotheses, we employ three-dimensional simulations based on the Immersed Boundary–Lattice Boltzmann Method (IB-LBM) [26]. As a typical non-body-conforming grid method [27,28], the IB-LBM efficiently resolves complex fluid-particle interactions without mesh deformation. In our implementation, the fluid is resolved on a fixed Eulerian grid, and particles are modeled on a Lagrangian grid, with an improved direct-forcing scheme ensuring accurate coupling. This approach enables the precise quantification of how density difference, independently of other factors, governs inter-particle attraction and repulsion in 3D.

This paper is organized as follows. The numerical methodology of the IB-LBM is introduced in Section 2. The accuracy of the present method in modeling particle sedimentation is validated through two benchmark cases in Section 3. The settling processes of two particles in tandem and side-by-side configurations are simulated in Section 4, where the motion responses of dual particles with different densities are discussed. Finally, significant findings and conclusions of this paper are summarized in Section 5.

2. Numerical Method

2.1. Fluid Flow Solver

In this study, the Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM) is employed to solve the fluid flow. The distribution functions are stored and updated on regular lattices, and flow field information exchange with surrounding lattices is achieved through discrete velocities . The governing equation is [29]

where denotes the spatial position of the lattice, and represents time. is the relaxation time coefficient, which is related to the fluid viscosity, expressed as:

where is the kinematic viscosity, and is the speed of sound.

is the equilibrium distribution function, expressed as:

where are the weight functions, and and are the macroscopic density and velocity of the fluid, respectively.

Furthermore, to account for the influence of solid particles on the fluid, an external force term is incorporated into the LBM framework. is the discrete external force distribution function, given by:

where represents the force exerted by particles on the fluid.

The D3Q15 model is adopted in this study. The expressions for and are [30]

2.2. Particle Motion Solver

The fluid dynamics is solved using LBM, and the motion of particles is governed by Newtonian mechanics. The motion of particles in the fluid is primarily influenced by gravity, buoyancy, hydrodynamic forces, and collision forces. Their dynamics obey Newton’s second law:

Here, is the particle mass, is the particle translational velocity, are the coordinates of the Lagrangian nodes on the particle surface, is the number of Lagrangian nodes on the particle surface, is the fluid grid size, is the discrete area on the particle surface, is the particle density, is the gravitational acceleration, and are the coordinates of the particle centroid. represents the collision force between particles, expressed as [31]:

In this equation, is the particle radius. cij is a scaling factor for the collision force; in particle sedimentation problems, its value is the particle buoyancy [32]. is the stiffness coefficient, set to in this study. is the critical inter-particle distance, taken as to prevent particle penetration.

2.3. Immersed Boundary Method

In the Immersed Boundary Method (IBM), the fluid is solved on Eulerian grids, while particles are discretized using Lagrangian nodes, with the two sets of grids being independent. The IBM handles moving solid boundaries by applying an external force to the fluid. This study utilizes the improved direct-forcing method proposed by Cai et al. [33]. to simulate the interaction between the fluid and particles. The boundary force at the Lagrangian nodes on the particle surface is defined as:

Here, is the desired velocity at the Lagrangian node. In this formulation, the intermediate fluid velocity is obtained by interpolating from the fluid velocity without considering the immersed boundary, which can be calculated as:

where is the delta function [34]. The fluid velocity can be computed from the density distribution function:

is the correction factor developed by Cai et al. [33]. Compared to the direct-forcing method, this approach avoids multiple iterative procedures, enabling it to improve computational efficiency while providing accurate results.

where N denotes the number of Lagrangian points associated with .

Once the Lagrangian forces are determined, they are projected back to the Eulerian grid as an external force source term. Based on the boundary force at the Lagrangian nodes, the external force at the Eulerian grid is calculated as:

Finally, this external force is incorporated into the fluid solver to correct the flow velocity, thereby simulating the two-way coupling between the fluid and the particles. The fluid velocity at the Eulerian nodes is corrected as follows:

3. Validation of the Numerical Method

This section presents the validation of the present numerical method described in Section 2. The accuracy and capability are systematically assessed through two benchmark cases: the sedimentation of a single spherical particle and the complex hydrodynamic interactions involved in the DKT phenomenon of two spherical particles.

3.1. Sedimentation of a Single Spherical Particle

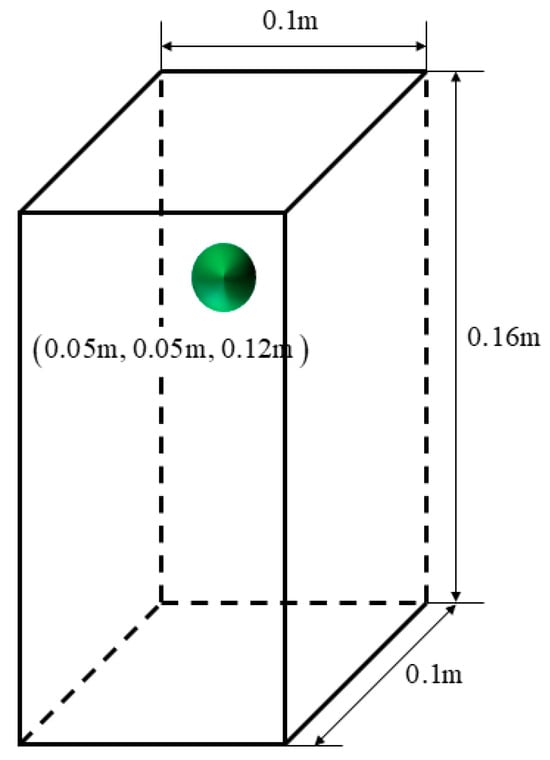

The sedimentation of a single particle in a closed channel serves as the first validation case. As illustrated in Figure 1, a spherical particle with a diameter of and a density of is initially positioned at (0.05 m, 0.05 m, 0.12 m) within a channel of dimensions 0.1 m × 0.1 m × 0.16 m. The simulation starts with both the fluid and the particle at rest. The particle is then released and settles under gravity = 9.8 . The fluid densities and viscosities are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Computational domain for single particle sedimentation.

Table 1.

Fluid densities and viscosities.

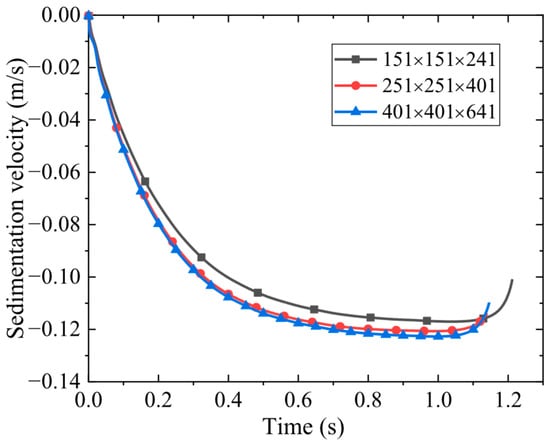

To assess the grid dependency of the numerical results and ensure their reliability, simulations were performed using three distinct meshes: the coarse mesh, the medium mesh, and the fine mesh. The corresponding cells for each mesh are detailed in Table 2. The temporal evolution of the particle settling velocity obtained from these simulations is presented in Figure 2. The results demonstrate that the accuracy of the results consistently improved with mesh refinement, confirming the convergence of the present method. After balancing computational accuracy against time cost, the medium mesh was selected for all subsequent simulations in this study. This medium mesh ensures result accuracy while maintaining reasonable computational efficiency.

Table 2.

Three different grid settings for a single spherical particle settling.

Figure 2.

Particle velocity versus time under three different meshes.

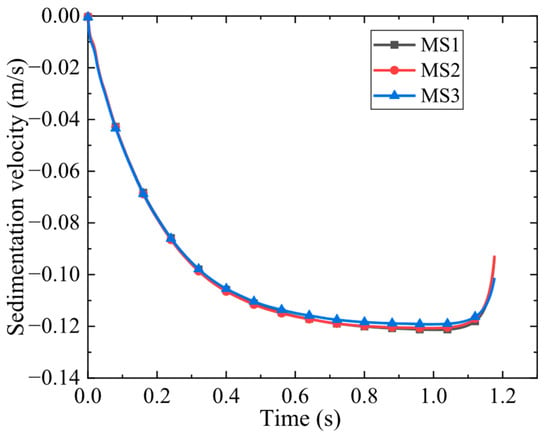

Mesh sensitivity analysis with respect to particle surface resolution was performed. The fluid domain was discretized using a fixed grid of 251 × 251 × 401 lattices. The particle surface was represented by Lagrangian points with varying spatial resolution to investigate the influence of surface mesh size on the accuracy of the settling velocity. The ratio of the particle surface mesh size () to the fluid mesh size () for each configuration is summarized in Table 3. The resulting settling velocities are shown in Figure 3. The results indicate with a decrease in the number of particle surface nodes, the computational accuracy is reduced, but the maximum error does not exceed 3%. Considering both computational accuracy and efficiency, a fluid grid of 251 × 251 × 401 cells combined with 1538 Lagrangian points on the particle surface was selected as the reasonable configuration for the subsequent simulations in this work.

Table 3.

Discretization of the particle surface with four different numbers of Lagrangian points.

Figure 3.

Particle velocity versus time under three different particle surface resolutions.

Through a comprehensive analysis of grid convergence and the influence of the ds/dx ratio, it can be concluded that for simulating particle sedimentation using the IB-LBM, the fluid grid resolution has a significant impact on computational accuracy. When the fluid grid meets the accuracy requirements, the surface grid of the particles can be selected from a wide range without substantially affecting the overall precision. This finding provides a valuable basis for grid division in subsequent numerical studies on particle sedimentation.

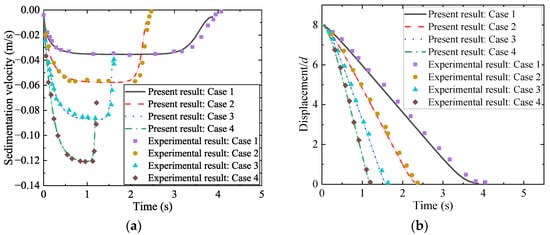

Figure 4 depicts the temporal evolution of the particle settling velocity and displacement. The curves clearly delineate three distinct stages of the sedimentation process: (1) an initial acceleration stage where the particle velocity increases from rest; (2) a terminal velocity stage where the gravitational force is balanced by the combined buoyancy and fluid drag forces, resulting in a constant settling speed; and (3) a final deceleration stage caused by the wall effect as the particle approaches the channel bottom. A quantitative comparison between our numerical results and the experimental data from Cate et al. [6] shows good agreement. This comparison confirms that the present method accurately captures the fundamental fluid–particle interactions in sedimentation.

Figure 4.

Sedimentation of single spherical particle: (a) Settling velocity; (b) Displacement.

3.2. DKT of Two Spherical Particles

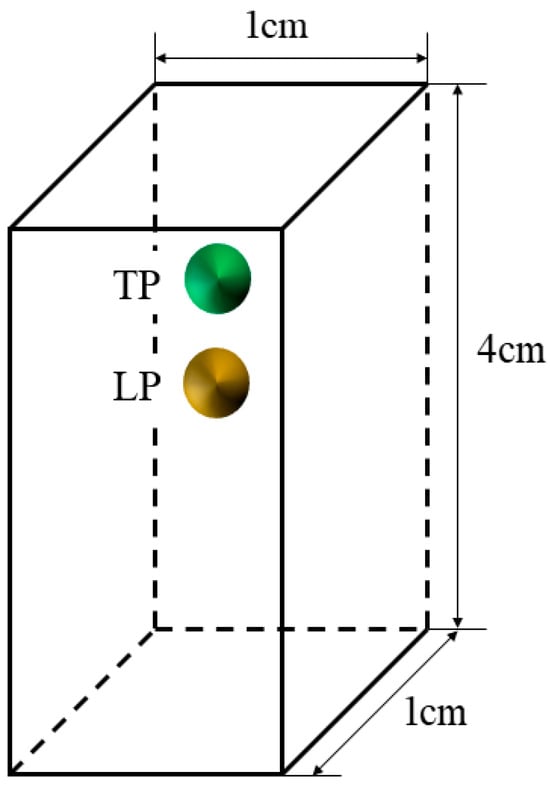

To further validate the capability of the current method to handle complex particle-particle interactions, we simulated the classic drafting–kissing–tumbling (DKT) phenomenon of two spherical particles. The fluid density is and the viscosity is . Two particles with density and diameter are initially arranged in a tandem configuration within a channel of size 1 cm 1 cm 4 cm, as shown in Figure 5. The upstream and downstream particles are designated as the trailing particle (TP) and leading particle (LP), with initial coordinates at (0.5 cm, 0.5 cm, 3.5 cm) and (0.5 cm, 0.5 cm, 3.16 cm), respectively. Solid wall boundary conditions are applied on all sides of fluid domain.

Figure 5.

Illustration of two spheres sedimentation.

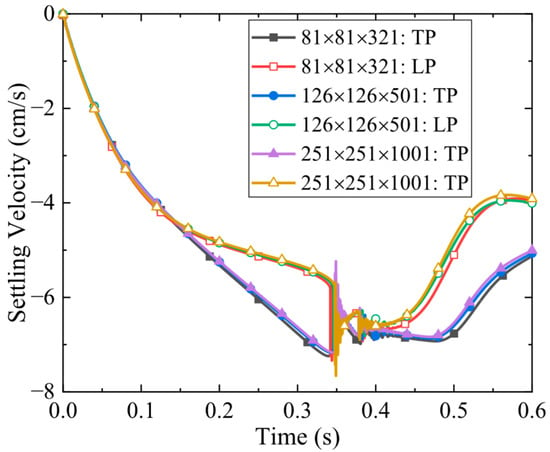

A grid convergence analysis was conducted for this simulation case using three sets of grids, as detailed in Table 4. In this case, ds/dx was maintained at 1, which, based on the results from Case 3.1, ensures reliable numerical accuracy. The velocity variation over time under different grids is shown in Figure 6. Since the DKT problem involves particle collisions, the calculation of collision forces depends on the grid size. This leads to considerable variation in the settling velocity after collision across different grids. Nevertheless, overall, the results become more accurate as the grid is refined, demonstrating good convergence. Therefore, considering both computational cost and accuracy, subsequent simulations will be conducted using a fluid grid of 126 × 126 × 501 nodes, with each particle surface discretized by 1344 Lagrangian points.

Table 4.

Three different mesh for two spherical particles settling.

Figure 6.

Two particle velocities versus time under three different mesh.

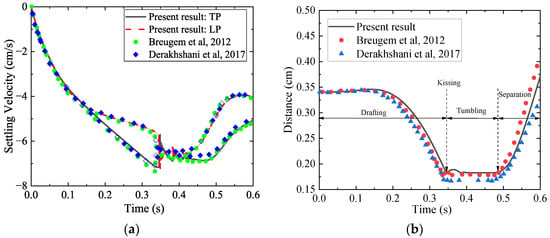

The sedimentation velocities and particle distance, plotted in Figure 7, demonstrate that the simulation successfully reproduces the entire DKT phenomenon. Initially (), both particles settle at nearly identical velocities. As the wake of the LP develops, the TP enters this low-pressure region. This results in reduced drag on the TP, causing TP to accelerate and approach the LP. This phase is known as drafting. The TP continues to accelerate until the two particles make kissing. Following a period of contact, hydrodynamic instabilities and contact forces cause the two particles to tumble. This tumbling motion ultimately leads to their separation. The temporal history of the particle distance allows for clear identification of these distinct stages, as shown in Figure 7. The obtained results for both settling velocity and particle distance are in satisfactory agreement with previously published numerical data [35,36], confirming the accuracy of the present method in simulating the intricate hydrodynamic interactions involved in two particles sedimentation.

Figure 7.

Sedimentation of two spherical particles: (a) Settling velocity; (b) Distance between particles [35,36].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Two Spherical Particles in a Tandem Configuration

In a tandem configuration, the low-pressure wake region behind the LP attracts the TP. This attraction accelerates the settling of the TP, demonstrating an attractive interaction between the particles. To systematically investigate the influence of particle density difference on this attractive interaction, the settling processes under different density conditions and were analyzed separately. All physical parameters remained identical to those in Case 3.2, except for the particle density. Each simulation was terminated when either particle first contacted the channel bottom. Upon reaching the bottom, a particle becomes stationary, and thus any further particle interactions naturally cease.

For , the density of the LP was kept constant, while the density of the TP was set to , , and , respectively. Figure 8 shows the time history of the distance between the particles. The distinct stages of particle interaction, such as drafting, kissing, tumbling, and separation, are also identifiable from the distance variation. As the TP density increases, two particles make contact earlier in the settling process. The higher-density TP accelerates rapidly from rest and catches up with the LP ahead. The increase in TP density also shortens the contact duration, leading to their rapid separation. After separation, the distance between the two particles continues to increase over time. The sedimentation trajectory is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 8.

Time history of the distance between the particles: the density of LP is greater than that of TP.

Figure 9.

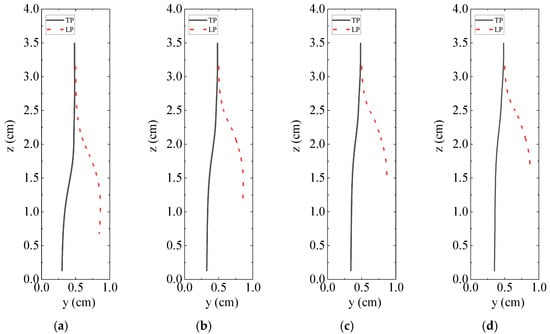

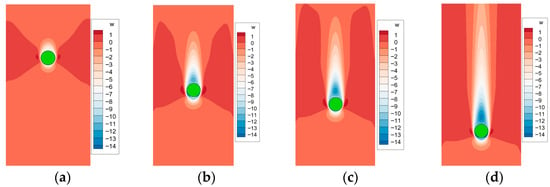

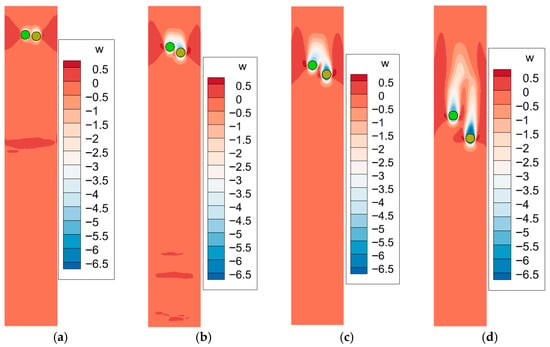

Sedimentation trajectory: the density of LP is greater than that of TP: (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) .

It can be observed that as the density of the TP increases, the separation of the particle trajectories occurs closer to the top of the channel. This indicates that the TP catches up with and contacts the LP over a relatively short distance. Notably, regardless of the TP density, the separation direction following collision remains consistent: the TP migrates to the left wall, while the LP moves to the right wall. With increasing TP density, the TP settles closer to the channel centerline at the bottom. These results suggest that a lower density particle has a weaker influence on the lateral migration of a higher density particle.

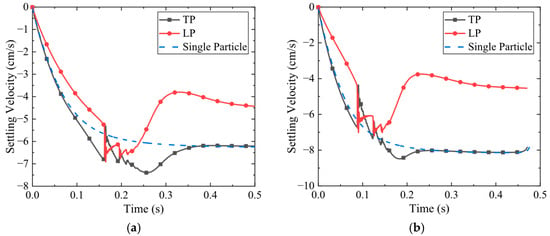

Figure 10 illustrates the settling velocities of the two particles. When the particles have identical densities, their velocities remain nearly identical during the initial period, as shown in Figure 7. Since particle density directly influences settling velocity, pronounced velocity differences emerge immediately upon release for particles with different densities. As the TP density increases, the time to collision is significantly reduced. The higher density of the TP results in a greater settling velocity, allowing it to catch up with the LP more rapidly.

Figure 10.

Settling velocity when the density of TP is greater than that of LP: (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) .

In the classical DKT phenomenon, the low-pressure wake region behind the LP can attract the TP and accelerate its settling. This flow-induced acceleration reflects an effective attractive interaction. To further investigate how the density difference between the particles influences this attraction, we also simulated the settling process of a single TP under identical conditions. A comparison was made between the TP velocity before collision and the settling velocity of a single particle (labeled “Single particle” in Figure 10). As the TP density increases, its settling velocity approaches that of the single particle case. This indicates that for pairs with a significant density difference, collision occurs primarily due to the higher settling velocity of the higher density TP, while the attractive effect of the lower-density LP on the TP is minimal. Due to the interaction between the two particles, the velocity of the TP increases continuously at a short time, yet eventually approaches the terminal velocity of a single particle. This confirms that after separation, the particles have negligible influence on each other.

For , the density of TP remains constant, the LP is set to , , and , respectively. To fully capture the interaction process between particles under , the computational domain from Case 3.2 is enlarged to 1 cm × 1 cm × 10 cm. The particles were initially positioned at (0.5 cm, 0.5 cm, 9.5 cm) and (0.5 cm, 0.5 cm, 9.16 cm), with all other conditions unchanged.

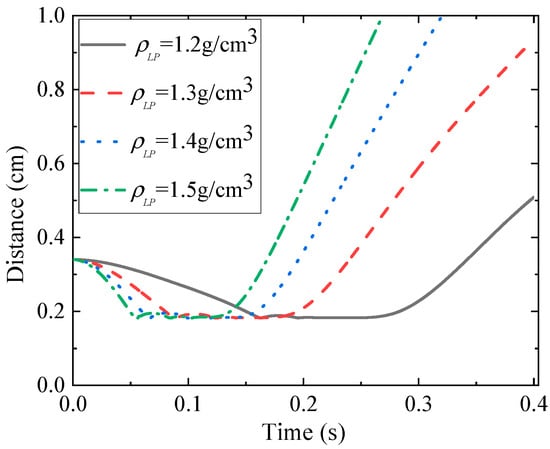

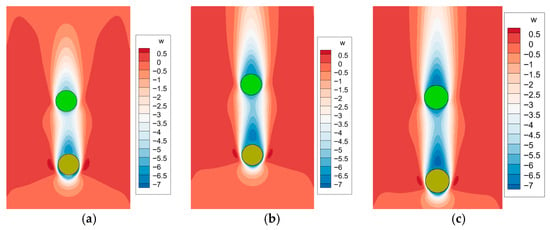

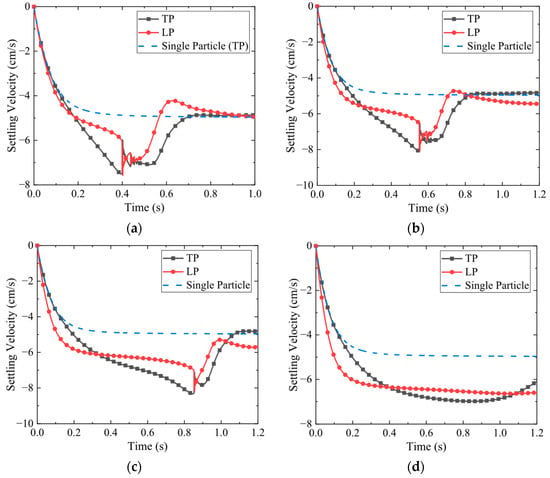

The distance between particles is shown in Figure 11. It can be observed that the variation in particle distance with time under differs significantly from the results under . For , the distance between particles continuously decreases from the moment of release. In contrast, under , the particle distance exhibits a distinct increase, followed by a subsequent decrease until kissing occurs. The maximum distance between particles before contact increases with the LP density . This occurs because under , the settling velocity of the LP initially exceeds that of the TP. As the LP wake develops, its influence on the TP grows, as illustrated in Figure 12. Consequently, the LP begins to attract the TP, causing the distance between them to gradually decrease. When , the LP and TP do not undergo kissing. This indicates that as the LP density increases, its attractive effect on the TP becomes insufficient to compensate for the influence of their density difference on settling velocity. Under this condition, the classical DKT phenomenon is also absent.

Figure 11.

Time history of the distance between two particles: the density of LP is greater than that of TP.

Figure 12.

Velocity contour and particle positions at characteristic instances: (a) Time = 0.2 s; (b) Time = 0.32 s; (c) Time = 0.44 s.

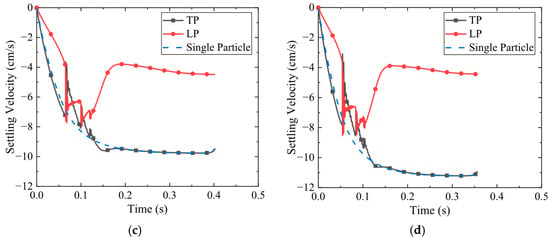

The settling velocities of the particles as functions of time are presented in Figure 13. It can be observed that the moment of kissing between the two particles is delayed as the density of LP increases. When the LP density reaches , kissing no longer occurs. Due to the density difference, the particles exhibit different settling velocities from the beginning of their release. The higher-density LP exhibits a greater settling velocity. As sedimentation proceeds, the attractive influence of the LP on the TP grows significantly. This attraction causes the settling velocity of the TP to increase, eventually exceeding that of the LP and leading to kissing, as shown in Figure 13a–c. To further analyze the attractive effect of the LP on the TP, the settling velocities of the particle pair were compared with those of the TP settling alone. The results show that the attractive effect of the LP on the TP strengthens as the LP density increases. However, due to the density difference between the particles, the higher-density LP rapidly moves away from the TP, requiring the TP to spend more time catching up. Even under the condition of , an increase in the TP velocity can still be observed, yet it does not lead to overtaking.

Figure 13.

Settling velocity: the density of LP is greater than that of TP: (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) .

Based on this analysis, the density difference between particles significantly influences their attraction and collision behavior. The evolution of particle distance exhibits distinct patterns under and . Comparison with single-particle settling results provides deeper understanding of the attractive interaction mechanism.

4.2. Two Spherical Particles in a Side-by-Side Configuration

To observe the settling process of particles in side-by-side configuration, the computational domain from Case 3.2 was extended to 1 cm 1 cm 6 cm. The two particles were initially positioned at (0.5 cm, 0.4 m, 5.5 cm) and (0.5 cm, 0.6 m, 5.5 cm), respectively, while all other computational parameters remained consistent with Case 3.2. The settling of two particles with identical densities was simulated, with particle densities set to , , and , respectively. The settling trajectories are shown in Figure 14. It can be observed that the distance between the particles remains nearly constant during the initial stage of sedimentation. Subsequently, the particles begin to repel each other, quickly moving apart horizontally. Finally, as settling continues, their interaction diminishes almost completely, approaching a steady state. This phenomenon is consistent with the numerical and experimental results reported by Liu et al. [24], which validates the capability of the present method to accurately simulate the repulsive interaction between particles.

Figure 14.

Settling trajectories of two particles with identical density in side-by-side.

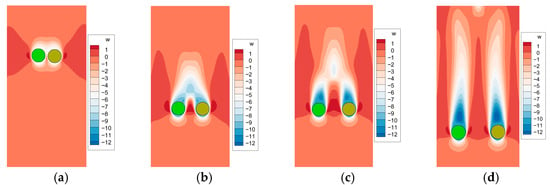

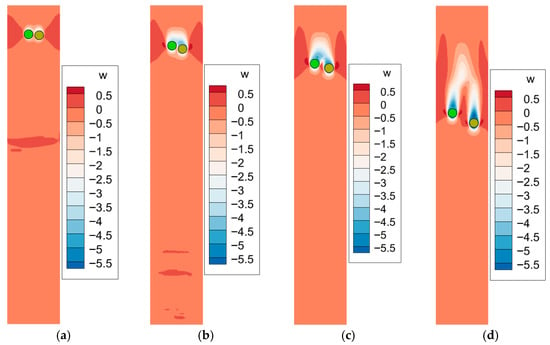

The velocity contours of the side-by-side particle pair (as shown in Figure 15) are compared with those of a single settling particle (as shown in Figure 16). In the initial stage of the dual-particle settling, the wake of the particle pair appears as an integrated structure, closely resembling the wake pattern generated by a single particle. As the settling velocity increases, the wake structure begins to split and gradually transitions into a dual-wake field, where each particle develops an individual wake. During this transition, asymmetric vortex structures form on both sides of the particles. The vortical flow between the two particles drives them to separate, which explains the repulsion observed when two particles with identical density settle side-by-side.

Figure 15.

Wake structures of two settling particles at characteristic instances: (a) Time = 0.04 s; (b) Time = 0.12 s; (c) Time = 0.16 s; (d) Time = 0.28 s.

Figure 16.

Wake structures of single particle at characteristic instances: (a) Time = 0.04 s; (b) Time = 0.12 s; (c) Time = 0.16 s; (d) Time = 0.28 s.

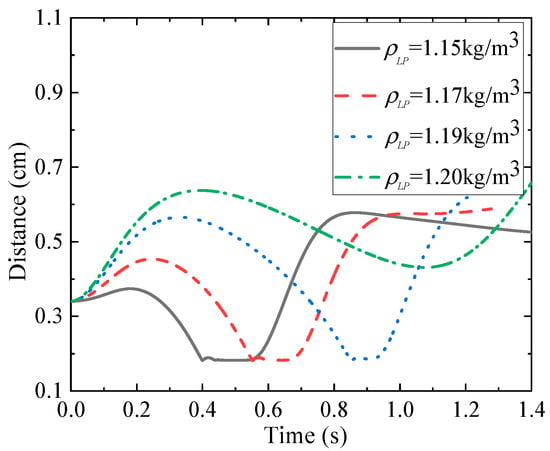

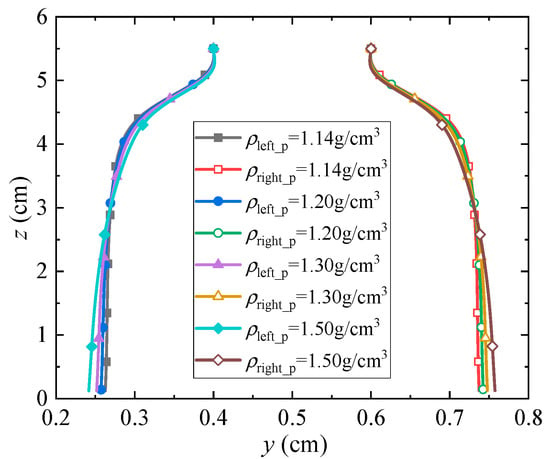

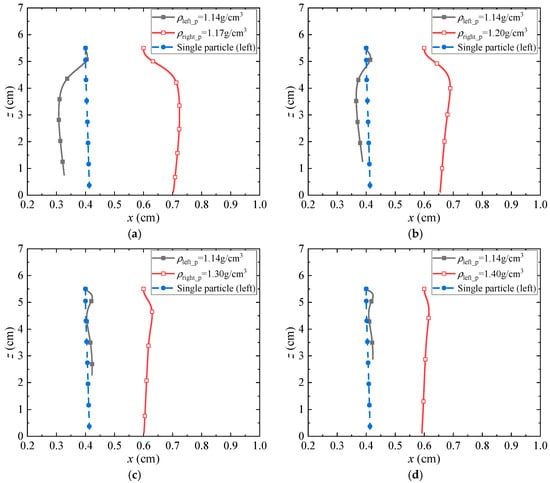

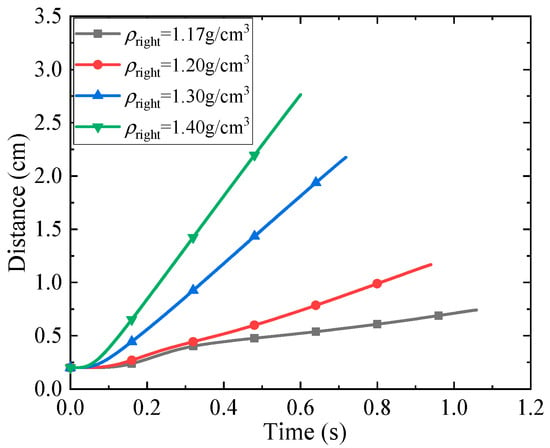

The influence of density difference between two particles on the repulsive interaction between particles is analyzed below. The density of the left particle (0.5 cm, 0.4 cm, 5.5 cm) was kept constant at , while the density of the right particle (0.5 cm, 0.6 cm, 5.5 cm) was set to , , and , respectively. The settling trajectories are shown in Figure 17, along with a comparison to the case where only the left particle was released. It can be observed that for two particles with different densities, the right particle with higher density exerts a slight attractive force on the left particle with lower density during the initial release stage. This attractive effect intensifies as the density of the right particle increases. As settling continues, a repulsive interaction between the particles remains observable; however, this repulsion weakens with increasing density of the right particle, resulting in reduced lateral migration. This occurs because the density difference between the two particles results in different settling velocities. Consequently, the vertical separation between them continuously increases, as shown in Figure 18, making it difficult for the particles to influence each other.

Figure 17.

Sedimentation trajectory for two particles with different density in a side by side: (a) , ; (b) , ; (c) , ; (d) , .

Figure 18.

Time history of the distance between the particles for two particles settling in a side by side.

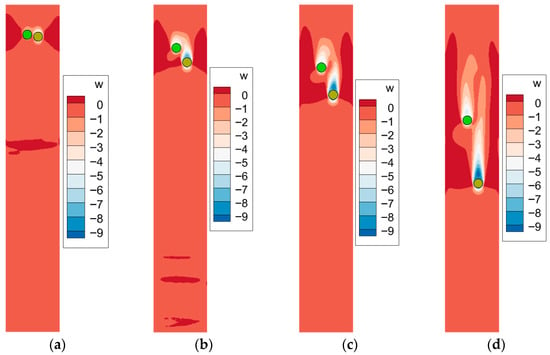

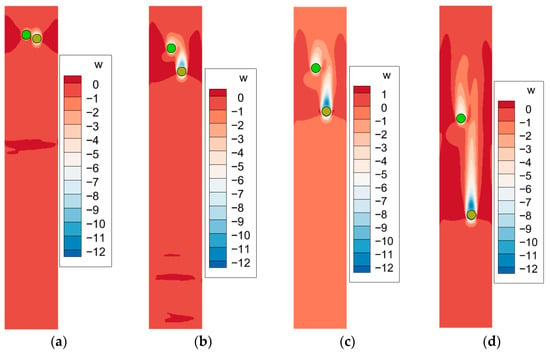

The velocity contours for particle pairs with different density are shown in Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21 and Figure 22. Due to the density difference between the two particles, the flow field becomes asymmetric. In the initial stage after release, the particles exhibit an integrated wake structure, as they are in close proximity and settle at relatively low speeds. As settling continues, the two particles gradually separate and develop individual wake fields. For cases with a large density difference, as shown in Figure 21 and Figure 22, particles rapidly separate in the vertical direction. As a result, the vortical flow between the particles diminishes rapidly as they separate. This leads to a reduction in the horizontal hydrodynamic forces and a corresponding weakening of the repulsive interaction.

Figure 19.

Velocity contour of two side-by-side settling particles when , : (a) Time = 0.04 s; (b) Time = 0.12 s; (c) Time = 0.20 s; (d) Time = 0.40 s.

Figure 20.

Velocity contour of two side-by-side settling particles when , : (a) Time = 0.04 s; (b) Time = 0.12 s; (c) Time = 0.20 s; (d) Time = 0.40 s.

Figure 21.

Velocity contour of two side-by-side settling particles when , : (a) Time = 0.04 s; (b) Time = 0.12 s; (c) Time = 0.20 s; (d) Time = 0.40 s.

Figure 22.

Velocity contour of two side-by-side settling particles when , : (a) Time = 0.04 s; (b) Time = 0.12 s; (c) Time = 0.20 s; (d) Time = 0.40 s.

5. Conclusions

The sedimentation of two spherical particles in both tandem and side-by-side configurations is examined in the present study based on the IB-LBM. The primary purpose is to analyze how density differences between particles influence their settling behavior, particularly the attractive and repulsive interactions under two particles with different density. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

(1) This study highlights that the DKT phenomenon invariably occurs at . The underlying mechanism is not solely the wake effect of the LP, but more critically, the density difference establishes a consistent settling velocity advantage for the TP. Consequently, the density difference, by granting the TP this kinematic superiority, becomes the dominant factor governing the attractive mode between particles. The greater the density of the TP, the more pronounced this controlling role becomes.

(2) For in the tandem configuration, the occurrence of DKT is determined by the density ratio, with a critical threshold identified at approximately 1.2:1.14. Beyond this ratio, the attractive effect induced by the particle wake becomes insufficient to offset the difference in settling velocities caused by the density disparity. Under conditions, although the inter-particle distance may decrease, it soon increases again, indicating that kissing does not ultimately occur.

(3) The interaction between side-by-side particles with density differences transitions from initial attraction to subsequent repulsion-a distinct behavior not observed in equal-density pairs. This repulsive effect weakens as the density difference increases, because the faster settling of the denser particle disrupts the symmetry of the vortical structure between the particles. These findings indicate that density disparity fundamentally alters the hydrodynamic interaction regime in side-by-side configurations.

This study elucidates how intrinsic density differences govern hydrodynamic interactions between two settling spheres. We demonstrate that density disparity regulates the DKT phenomenon in tandem configurations and triggers an attraction-to-repulsion transition in side-by-side arrangements. By revealing these fundamental inter-particle mechanisms, our work provides critical insights into understanding the collective migration of granular materials in marine engineering contexts. The findings offer a particle-scale explanation for sediment transport near seafloor structures, enable more accurate prediction of scour–backfill processes around pipelines, and establish a mechanistic basis for modeling the dispersion and settling of sediment plumes in deep-sea mining. By identifying density as a key governing parameter, this research supports more predictive modeling and strategic intervention in marine geotechnical and environmental engineering.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.H., M.T. and L.X.; Methodology, D.H.; Software, X.J.; Validation, D.H., X.J. and B.C.; Formal analysis, D.H.; Investigation, D.H., X.J. and M.T.; Resources, M.T.; Data curation, B.C., M.T. and L.X.; Writing—original draft, D.H.; Writing—review & editing, D.H.; Visualization, D.H., X.J., B.C. and M.T.; Supervision, M.T. and L.X.; Project administration, D.H. and L.X.; Funding acquisition, D.H. and L.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central University (Grant No. 3132025136).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, P.; Ye, N.; Han, Y.; He, X. Experimental Study on the Sedimentation Performance of an Arc-Plate Linear Sedimentation Tank. Water 2024, 16, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rommel, S.H.; Helmreich, B. Influence of Temperature and De-Icing Salt on the Sedimen-tation of Particulate Matter in Traffic Area Runoff. Water 2018, 10, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Lai, Z.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Z. Study on the Motion Characteristics of Particles Transported by a Horizontal Pipeline in Heterogeneous Flow. Water 2022, 14, 3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofany, N.; Kartono, A.; Husain, S.A. Numerical investigation of subsea pipeline embedment induced by oscillatory flow-driven sedimentation. Ocean Eng. 2025, 336, 108527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, U.J.; Hyeong, K.S.; Cho, H.Y. Estimation of Settling Velocity and Floc Distribution through Simple Particles Sedimentation Experiments. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Cate, A.; Nieuwstad, C.H.; Derksen, J.J.; Van den Akker, H.E.A. Particle imaging velocimetry experiments and lattice-Boltzmann simulations on a single sphere settling under gravity. Phys. Fluids 2002, 14, 4012–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortes, A.F.; Joseph, D.D.; Lundgren, T.S. Nonlinear mechanics of fluidization of beds of spherical particles. J. Fluid Mech. 1987, 177, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Fan, J.R.; Luo, K. Combined multi-direct forcing and immersed boundary method for simulating flows with moving particles. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 2008, 34, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, D.M.; Lin, J.Z. A LB-DF/FD Method for Particle Suspensions. Commun. Comput. Phys. 2010, 7, 544–563. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.; Stockie, J.M. Numerical Simulations of Particle Sedimentation Using the Immersed Boundary Method. Commun. Comput. Phys. 2015, 18, 380–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Galindo-Torres, S.A.; Tang, H.W.; Jin, J.Q.; Scheuermann, A.; Li, L. An efficient Discrete Element Lattice Boltzmann model for simulation of particle-fluid, particle-particle interactions. Comput. Fluids 2017, 147, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.T.; Liu, H.H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. Direct numerical simulation of the sedimentation of a particle pair in a shear-thinning fluid. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2020, 5, 014304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.C.; Alexiadis, A.; Chen, H.L.; Sheu, T.W.H. Numerical computation of fluid-solid mixture flow using the SPH-VCPM-DEM method. J. Fluids Struct. 2021, 106, 103369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, Z.L.; Mi, J.C. Drafting, kissing and tumbling process of two particles with different sizes. Comput. Fluids 2014, 96, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Liu, J.D.; Zhao, J.N.; Yin, X.L.; Lu, H.L. IBM-LBM-DEM Study of Two-Particle Sedimentation: Drafting-Kissing-Tumbling and Effects of Particle Reynolds Number and Initial Positions of Particles. Energies 2022, 15, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Kumar, M. Study of drafting, kissing and tumbling process of two particles with different sizes and densities using immersed boundary method in a confined medium. Appl. Math. Comput. 2020, 386, 125411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panghal, R.; Ghosh, S.; Mitra, K.; Yadav, P. Study of gravitational sedimentation of two flexible circular shaped particles using Immersed Boundary Method. Chin. J. Phys. 2024, 88, 647–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Xu, Z.J.; Wu, W.B.; Zhang, J.Y.; Wu, Q.; Liu, M.B. Drafting, kissing, and tumbling of a pair of particles settling in non-Newtonian fluids. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 023301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Xu, J.Z.; Zhang, J.Y.; Liu, M.B. Sedimentation of elliptical particles in Bingham fluids using graphics processing unit accelerated immersed boundary-lattice Boltzmann method. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 013330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walayat, K.; Zhang, Z.L.; Usman, K.; Chang, J.Z.; Liu, M.B. Fully resolved simulations of thermal convective suspensions of elliptic particles using a multigrid fictitious boundary method. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 139, 802–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.M.; Lee, T.S. Two spheres sedimentation dynamics in a viscous liquid column. Comput. Fluids 2015, 123, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Tahmasebi, P. Drafting, Kissing and Tumbling Process of Two Particles: The Effect of Morphology. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2023, 160, 104379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.C.; Hsiao, W.W.; Lin, T.Y.; Lin, C.A. Simulations of two sedimenting-interacting spheres with different sizes and initial configurations using immersed boundary method. Comput. Mech. 2015, 55, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Q.; Zhang, P.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Z.H.; Yuan, S.Y.; Tang, H.W. Interaction between dual spherical particles during settling in fluid. Phys. Fluids 2021, 33, 013312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, D.M.; Lin, J.Z. Simulation of sedimentation of two spheres with different densities in a square tube. J. Fluid Mech. 2020, 896, A12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.G.; Michaelides, E.E. Proteus: A direct forcing method in the simulations of particulate flows. J. Comput. Phys. 2005, 202, 20–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.K.; Hassan, Y.A. A comparative study of direct-forcing immersed boundary-lattice Boltzmann methods for stationary complex boundaries. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2011, 66, 1132–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Shu, C. An improved immersed boundary-lattice Boltzmann method for simulating three-dimensional incompressible flows. J. Comput. Phys. 2010, 229, 5022–5042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Q.; Cai, Y.N.; Zhang, G.Y.; Quan, X.B.; Lu, J.H.; Li, S. A coupled immersed boundary-lattice Boltzmann method with smoothed point interpolation method for fluid-structure interaction problems. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2018, 88, 363–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, D.R.J.; Leonardi, C.R.; Feng, Y.T. An efficient framework for fluid-structure interaction using the lattice Boltzmann method and immersed moving boundaries. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2011, 87, 66–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowinski, R.; Pan, T.W.; Hesla, T.I.; Joseph, D.D.; Périaux, J. A fictitious domain approach to the direct numerical simulation of incompressible viscous flow past moving rigid bodies:: Application to particulate flow. J. Comput. Phys. 2001, 169, 363–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.S.; Chen, S.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.H.; Zha, L.; Bao, S.; Zheng, C.G. Simulating the interactions of two freely settling spherical particles in Newtonian fluid using lattice-Boltzmann method. Appl. Math. Comput. 2015, 250, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.N.; Li, S.; Lu, J.H. An improved immersed boundary-lattice Boltzmann method based on force correction technique. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2018, 87, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.C.; Peskin, C.S. An immersed boundary method with formal second-order accuracy and reduced numerical viscosity. J. Comput. Phys. 2000, 160, 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breugem, W.P. A second-order accurate immersed boundary method for fully resolved simulations of particle-laden flows. J. Comput. Phys. 2012, 231, 4469–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshani, S.M.; Schott, D.L.; Lodewijks, G. Modeling particle sedimentation in viscous fluids with a coupled immersed boundary method and discrete element method. Particuology 2017, 31, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.