1. Introduction

Net-cage aquaculture has become a key component of modern marine fisheries, enabling efficient utilization of coastal and offshore waters for large-scale fish production. However, biofouling organisms that accumulate on the net surfaces increase flow resistance and impose additional structural loads, as illustrated in

Figure 1, thereby reducing water exchange, degrading fish health, and threatening cage integrity [

1]. To maintain the efficiency and safety of aquaculture operations, regular underwater cleaning of nets has become a critical maintenance task. Traditional diver-based cleaning methods are inefficient, costly, and potentially hazardous, motivating the development of low-cost, automated underwater cleaning robots for long-term maintenance in aquaculture cages [

2,

3].

Accurate localization is critical for autonomous operation of underwater robots. However, the absence of Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) signals makes underwater navigation particularly challenging. High-precision acoustic–inertial systems, such as inertial navigation combined with Doppler velocity logs (INS + DVL) or long-baseline (LBL) acoustic positioning, though offering highly accuracy, are generally hampered by high equipment costs, complex deployment processes, and vulnerability to aquatic noise and multipath effects [

4]. These characteristics make them unsuitable for compact, path-constrained environments such as fish cages. For underwater net-cage cleaning robots operating in fixed aquaculture cage environments, the use of acoustic positioning remains economically prohibitive [

5].

Inertial measurement units (IMUs) and vision-based systems are often considered for underwater localization, but both face significant limitations in challenging conditions. IMU suffer from long-term drift due to sensor errors, while vision-based systems are highly susceptible to environmental factors such as lighting changes, water turbidity, and weak textures, leading to inaccuracies in feature extraction and pose estimation. As a result, single-modality systems, whether visual or inertial, struggle to maintain accuracy over extended periods.

Some studies have attempted to develop low-cost underwater robotic systems by integrating compact and affordable sensors [

6]. For example, small-scale underwater vehicles have been developed for aquaculture inspection tasks where precise positioning is essential [

7,

8]. Other works have explored the use of inexpensive sensors for monitoring water quality and fish behavior, with potential applications in underwater cages [

9]. However, most of these approaches still struggle to balance robustness, cost efficiency, and localization accuracy.

Underwater localization techniques can generally be divided into three categories. Inertial navigation systems (INSs) provide high-frequency attitude and acceleration data but suffer from accumulated drift over time. Acoustic navigation systems, such as LBL, USBL, and DVL, achieve high precision by exploiting sound propagation but incur high hardware costs and deployment complexity. Vision-based systems are more compact and economical, providing rich environmental information, yet they are highly sensitive to water turbidity, illumination changes, and weak textures [

10]. Commercial ROVs such as BlueROV2 integrate IMUs, compasses, and surface GPS [

11], but accurate subsurface localization still requires costly DVL or hybrid acoustic–vision modules [

12]. For repetitive cleaning tasks in structured cages, these acoustic systems remain economically prohibitive, whereas pure vision approaches lack robustness. The costs of different underwater positioning schemes are shown in

Table 1. Hence, for structured and bounded environments, lightweight visual–inertial methods are becoming increasingly relevant.

Visual–inertial odometry (VIO) has emerged as an efficient alternative by fusing high-frequency inertial data with visual observations to achieve more accurate pose estimation. Classical SLAM systems such as ORB-SLAM3 and VINS-Fusion have demonstrated excellent performance in terrestrial and aerial environments [

13,

14,

15]. However, their direct application underwater faces significant challenges. Depth-dependent light attenuation, uneven illumination, turbidity, and repetitive net structures all degrade feature extraction and matching reliability [

16,

17]. Moreover, conventional visual SLAM assumes that the observed scene is rigid, static, and Lambertian—assumptions often violated underwater due to backscattering, wavelength-dependent absorption, and suspended particles that reduce image contrast and color fidelity [

18,

19].

To overcome these limitations, several studies have introduced artificial landmarks such as reflective or LED markers to enhance underwater localization [

20,

21,

22], while polarization-based imaging and deep-learning detection models (e.g., YOLOv5, YOLOv8) have also shown promise for improving robustness [

23,

24]. Nonetheless, most prior research relies on monocular cameras, which cannot recover absolute scale and are prone to drift. Stereo-vision-based localization and navigation, despite their ability to reconstruct depth geometry, remain insufficiently explored in underwater environments [

25].

The fusion of multiple sensing modalities has become an important direction for improving underwater localization [

26]. By combining the complementary strengths of vision, inertial, and depth sensors, multi-sensor fusion achieves better observability and resilience to feature loss. Common fusion methods include Extended Kalman Filters (EKFs), Unscented Kalman Filters (UKFs), and factor-graph-based optimization [

27,

28]. Common approaches are summarized in

Table 2. Traditional EKF frameworks are efficient for low-resource systems but limited in handling sliding-window constraints and multi-frame consistency. By contrast, factor graph optimization models state estimation as nonlinear least-squares with flexible multi-source constraints, improving accuracy and stability. Libraries such as GTSAM and Ceres are widely adopted in SLAM and VIO. Among these, factor graphs offer superior multi-frame consistency and flexibility for integrating heterogeneous data sources, making them well suited for embedded real-time systems. However, existing research has primarily focused on large-scale AUVs in open-water environments, leaving a gap for low-cost, tightly coupled solutions specifically optimized for small, structured aquaculture cages.

To address these challenges, this study proposes a lightweight visual–inertial–depth (VID) fusion localization framework designed for underwater net-cage cleaning robots. An illustrative schematic of the robot operating inside a marine aquaculture cage is shown in

Figure 2. Built on the VINS-Fusion architecture, the proposed system integrates a pressure-based depth factor to enhance Z-axis observability and a reflective-anchor-assisted initialization strategy to achieve consistent world-frame alignment. Stereo vision provides metric scale and lateral accuracy, IMU pre-integration supplies high-frequency motion constraints, and the pressure sensor stabilizes vertical estimation. The framework operates in real time (~20 Hz) on a Jetson Orin NX embedded platform within the ROS environment, ensuring onboard computation and seamless integration for field deployment.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

A reflective-marker-assisted initialization method for coordinate binding and attitude calibration in underwater environments.

Integration of a pressure-depth factor into the VINS-Fusion framework, introducing tightly coupled depth constraints and compensation for pressure bias.

Real-time embedded implementation and validation on a Jetson Orin NX platform, demonstrating practical feasibility for structured aquaculture scenarios.

In summary, this study provides a low-cost, robust, and scalable localization solution tailored to underwater net-cage cleaning robots. By combining stereo vision, IMU, and depth sensing in a tightly coupled manner, the proposed system bridges the gap between high-cost acoustic solutions and unstable visual odometry, offering a practical foundation for intelligent and autonomous aquaculture operations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Overview

This study presents a lightweight underwater localization system based on Visual–Inertial–Depth (VID) fusion, specifically designed for net-cage cleaning robots in aquaculture environments. The system is built upon the VINS-Fusion framework, which is a robust VIO solution, and augmented with depth measurements from a pressure sensor to enhance Z-axis observability. Additionally, robust initialization are achieved using engineering-grade prismatic reflective sheeting as fiducial anchors, ensuring stable pose estimation in structured net-cage environments.

As shown in

Figure 3, the system architecture follows the principles of modularity, low power consumption, and real-time operation. It consists of three main subsystems: (1) the robot body, equipped with cleaning brushes for biofouling removal; (2) the control housing, which drives propeller actuation; and (3) the localization module, containing the sensor suite and embedded computing unit. The sensor suite integrates a stereo camera (20 Hz) with an onboard IMU (100 Hz) and a pressure transducer (20 Hz). The stereo pair provides metric scale and texture features, the IMU supplies high-frequency angular velocity and acceleration data for short-term motion continuity, and the pressure sensor delivers absolute depth for global Z-reference stabilization. All computations are executed onboard using a Jetson Orin NX running Ubuntu 20.04 and ROS Noetic, achieving real-time processing at approximately 20 Hz.

An NVIDIA Jetson Orin NX embedded computer provides sufficient computational capability for optimized VIO while maintaining low power and compact form factor for sealed housing integration. All data acquisition, processing, and fusion are performed onboard, forming a compact, self-contained system.

The proposed system architecture integrates local but drift-prone visual/inertial sensors with a globally stable yet low-frequency depth sensor to achieve complementary strengths. The visual and IMU modules serve as local sensors, providing high-frequency short-term motion estimation; however, pure inertial navigation suffers from cumulative drift, while vision-only localization is prone to failure in weak-texture underwater environments due to illumination and image quality variations. In contrast, the depth sensor functions as a global reference, directly measuring relative depth along the gravity axis without cumulative error, though it provides only one-dimensional information at low frequency. To address these limitations, an optimization-based fusion framework is constructed: the pressure sensor supplies absolute depth constraints to suppress Z-axis drift, while a reflective-anchor module provides global references when available, resolving the global orientation and frame-alignment ambiguity inherent to pure visual–inertial systems. Compared with conventional acoustic methods (e.g., USBL/LBL or DVL), the system eliminates the need for external base stations and costly sensors, thus reducing deployment complexity and hardware expense. By incorporating depth factors and anchor-point assistance, the system enhances observability and robustness, mitigating long-term drift and global frame uncertainty. Overall, the architecture follows the principle of “multi-source information fusion with complementary advantages,” improving both accuracy and robustness in complex underwater environments.

The workflow proceeds as follows: upon entering the net-cage, the robot initializes its world coordinate frame using reflective fiducial anchor. During normal operation, the stereo camera acquires underwater images at moderate frame rates, the IMU synchronously records inertial data, and the depth sensor periodically outputs absolute depth. All data are published via ROS nodes to the embedded computing unit and processed by the localization module. The visual frontend extracts and tracks image features, the inertial frontend performs IMU pre-integration, and depth readings are time-synchronized before entering the back-end optimization. The sliding-window optimizer fuses all sensor factors in the IMU frame, estimating the robot’s pose relative to the initialized anchor-based world frame in real time. The outputs include 3D position, orientation, and uncertainty estimates, which directly support cleaning path planning and actuator control. This closed-loop pipeline—from sensor data acquisition to pose estimation—runs entirely on the embedded platform, ensuring real-time operation in underwater cage-cleaning tasks.

2.2. Embedded Hardware and Sensor Configuration

The sensor suite and embedded computer are encapsulated within an acrylic pressure-resistant housing to ensure waterproofing and long-term durability. The hardware configuration includes the following components:

Computing unit: NVIDIA Jetson Orin NX (8 GB) running Ubuntu 20.04 + ROS Noetic, responsible for multi-sensor fusion and real-time state estimation.

Stereo vision system: OAK-D-S2 stereo camera (resolution 640 × 400, 20 Hz) with an integrated IMU (100 Hz) providing synchronized imagery, angular velocity, and acceleration measurements.

Pressure sensor: MS5837-30BA connected via I2C, with an accuracy of approximately 2 mm, used to constrain Z-axis drift and provide absolute depth.

Power and protection: UPS battery for continuous operation and sealed connectors for power and data transmission; the acrylic housing ensures heat dissipation and system reliability.

This configuration balances sensor diversity and platform integrability: stereo vision ensures scale, IMU ensures short-term continuity, and pressure ensures long-term Z-axis stability. The hardware cost and power consumption are substantially lower than those of acoustic solutions, making the system suitable for large-scale deployment. The system hardware design combination is shown in

Figure 4.

2.3. Overview of Fusion Framework

The software framework adopts a modular ROS-based architecture with three primary layers:

Sensor driver layer: The stereo camera publishes synchronized image and IMU topics, and the pressure sensor publishes depth readings, all with precise timestamps.

State estimation layer: The core node extends VINS-Fusion to include pressure-depth constraints. The front end performs feature extraction and optical-flow tracking, while the back end performs joint optimization of visual, inertial, and depth factors in a sliding-window factor graph.

Auxiliary tools layer: Provides real-time visualization through RViz and data recording through rosbag.

Each layer is decoupled via ROS topics to ensure modular independence, while within the state estimation layer, all observation factors are tightly coupled in a unified factor graph to obtain globally consistent solutions.

All computations are executed onboard the Jetson. The overall software framework and data flow are illustrated in

Figure 5. The system follows a tightly coupled design consisting of Front-end processing, Back-end optimization, and Global initialization. This modular design supports extensibility; additional sensors such as sonar or LED markers may be incorporated by introducing new factor terms without altering the core framework.

Initialization and anchor assistance: After deployment, the robot remains stationary for several seconds to collect IMU measurements and the current pressure reading. The mean accelerometer output is used to determine the gravity direction (setting the world Z-axis) and to roughly estimate the initial gyroscope and accelerometer biases. The initial pressure value is compared with a known surface reference to calculate a pressure offset. The robot is then maneuvered in front of a reflective fiducial anchor, and stereo ranging is used to measure its distance. The reflector is set as the origin, establishing the transformation between the camera frame and the net-cage coordinate system. The anchor is only used during initialization to align the global reference frame (attitude and position) and does not contribute residuals to optimization [

29].

Time synchronization: Since the camera, IMU, and pressure sensor operate at different sampling rates, the system adopts visual keyframes as the temporal reference. Specifically, for each incoming keyframe, the corresponding IMU data are retrieved from the buffer and pre-integrated, while the closest depth reading is obtained from the pressure sensor buffer [

30]. If multiple values exist, the average is used; if missing, linear interpolation is applied. Process are illustrated in

Figure 6. This process aligns the three modalities at the same timestamp, ensuring consistent input for sliding-window optimization.

2.4. Sensor Fusion Front-End

2.4.1. Feature Extraction and Tracking

Upon the arrival of a new stereo image frame, the visual front-end extracts FAST corners or alternative salient features. Given the degraded quality typical of underwater imagery—characterized by turbidity, low contrast, and uneven illumination—the feature detection threshold is deliberately lowered to ensure a sufficient number of stable features. These features are subsequently tracked using a pyramidal optical flow algorithm across both the stereo image pair and consecutive temporal frames. Successfully matched stereo correspondences are triangulated to obtain initial depth estimates, forming 3D landmark candidates. Meanwhile, inter-frame feature tracks provide parallax observations that support robust initialization of the relative pose between consecutive frames.

2.4.2. IMU Pre-Integration

The IMU front end collects high-frequency inertial measurements, which are pre-integrated between the timestamps of successive keyframes. IMU pre-integration incorporates high-frequency angular velocity and acceleration into the motion constraints while avoiding the need to explicitly optimize all intermediate states, significantly reducing computational complexity [

31].

2.4.3. Depth Synchronization

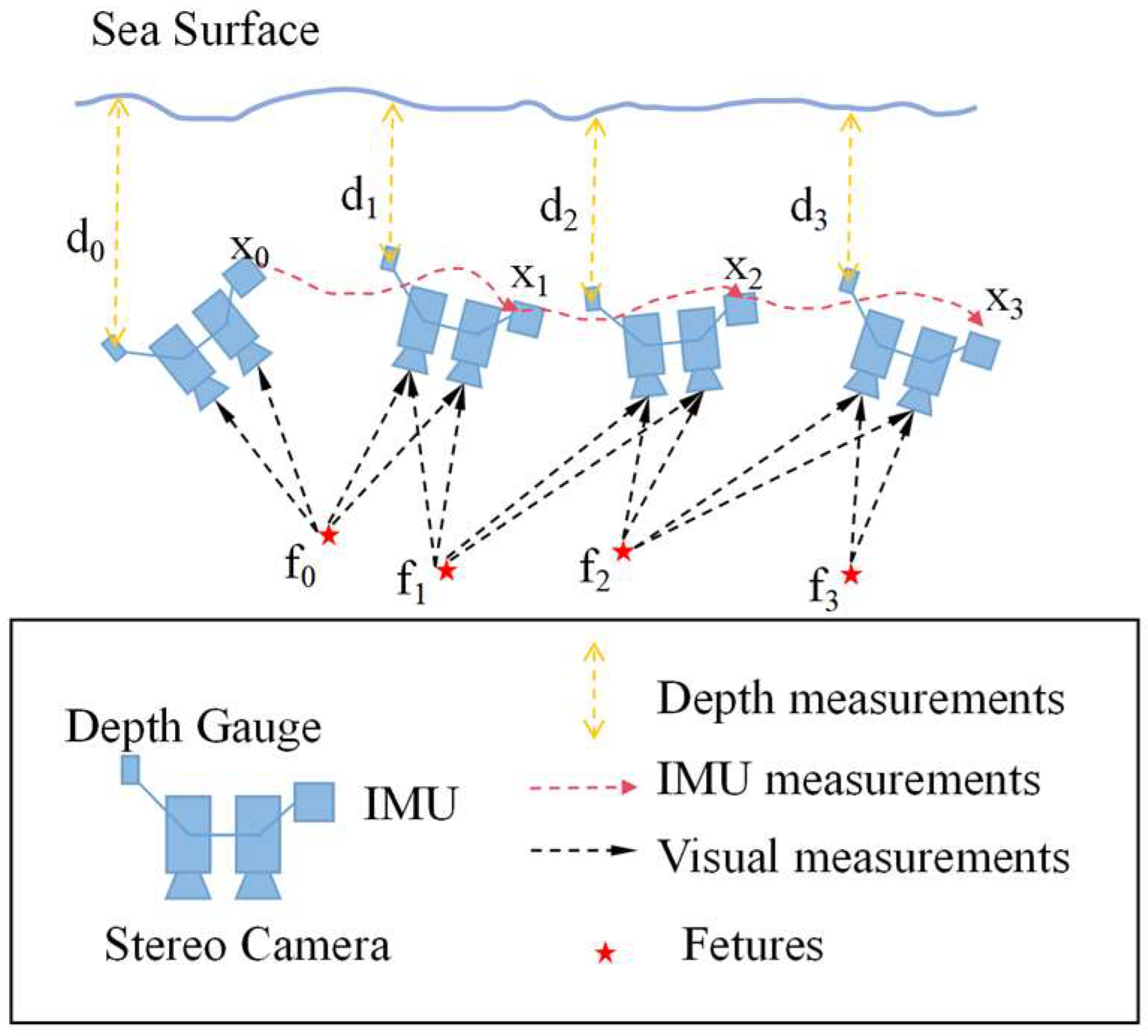

Depth readings associated with each keyframe are retrieved from the pressure-sensor buffer, where the closest measurement is selected (or interpolated if necessary). Schematic diagram of multi-sensor measurement are illustrated in

Figure 7. After synchronization, the visual features, IMU pre-integration results, and pressure-derived depth values are consolidated into a candidate keyframe for the back end. Frames with insufficient valid feature correspondences are discarded to preserve the robustness and accuracy of subsequent sliding-window optimization [

32].

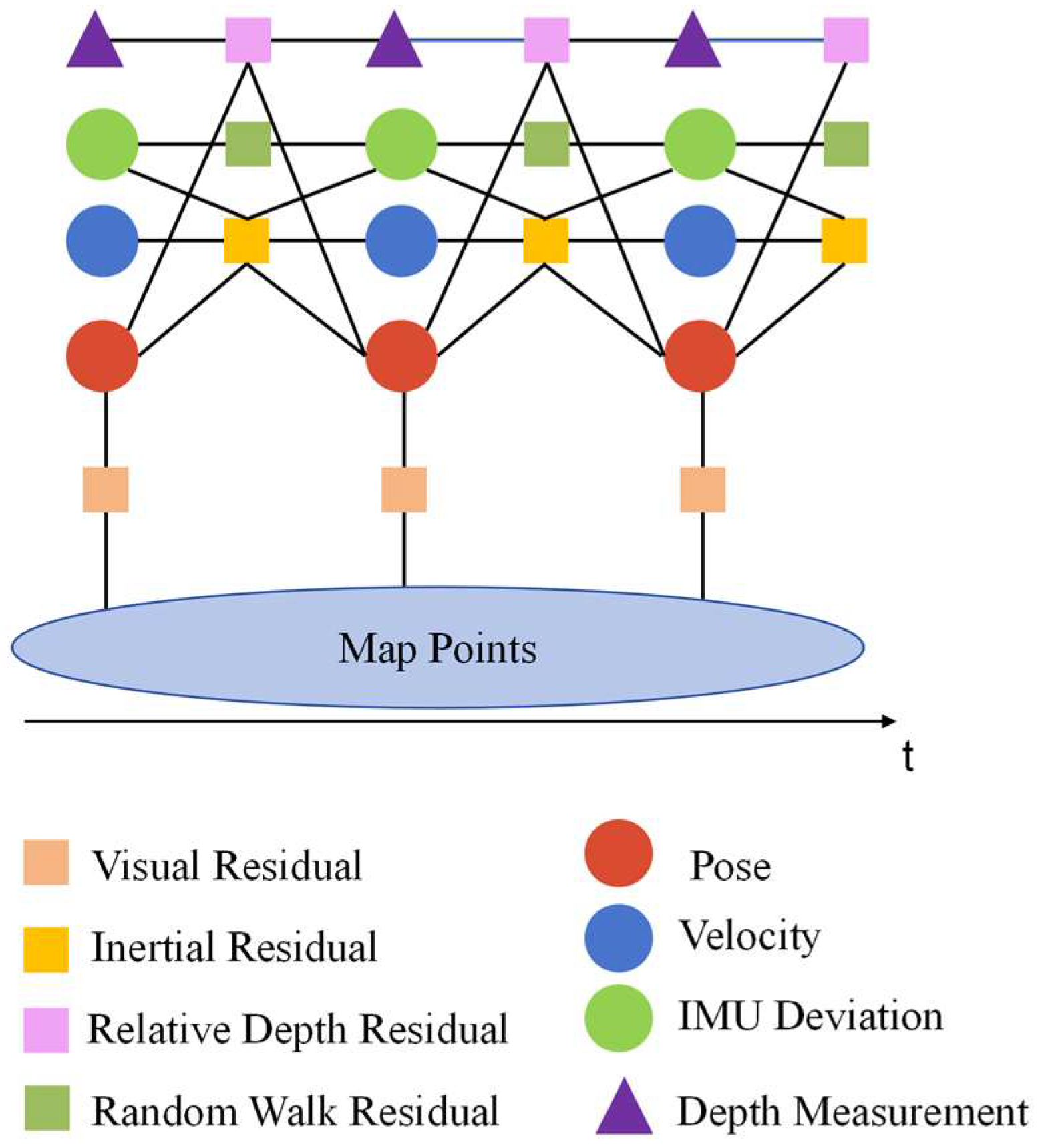

2.5. Sliding-Window Back-End Optimization

Back-end optimization: The back end maintains a sliding window of the most recent keyframes (typically 5–10) and formulates a nonlinear optimization problem over this active set. The objective function consists of three types of residuals:

Visual reprojection errors, representing discrepancies between observed feature locations and their projections onto the image plane.

IMU pre-integration errors, capturing inconsistencies between predicted and estimated motion across keyframes.

Depth residuals, defined as the difference between the estimated keyframe depth (derived from the robot’s world-frame position) and the corresponding pressure-sensor measurement.

These residuals form a sparse nonlinear least-squares problem, naturally expressed as a factor graph, where states (pose, velocity, biases) and landmarks are variable nodes, and each measurement contributes an observation factor. Iterative solutions are obtained using the Levenberg–Marquardt or Gauss–Newton methods. To enhance robustness, Huber kernels are applied to visual reprojection errors to reduce the influence of outliers caused by poor underwater visibility. Residual thresholds are also imposed to reject anomalous pressure readings. After each iteration, correction increments are applied to update all active states within the sliding window, yielding refined robot pose estimates.

Sliding-window management: As the number of keyframes grows, a marginalization procedure is invoked once the window exceeds its predefined capacity. Typically, the earliest keyframes, those providing limited parallax, or landmarks visible only in marginalized frames are selected for removal. Marginalized information is preserved in the form of prior factors, thereby constraining the remaining variables and preventing unbounded drift, particularly along the Z-axis. Proper conditioning—through accurate covariance propagation and rounding-error control—ensures numerical stability and long-term estimator consistency.

State Output and System Integration: After each optimization cycle, the pose of the latest keyframe (or current timestamp) is published as the real-time localization output via ROS topics. Velocity and IMU bias estimates are maintained internally, while all sensor streams and state variables are recorded in rosbag files for offline analysis.

The overall system adopts a ROS-based modular architecture, enabling clear separation between sensor drivers, front-end processing, back-end optimization, and visualization. This modularity supports extensibility—for example, sonar or additional environmental sensors can be integrated simply by adding new drivers and corresponding factor-graph terms without modifying existing modules. The front-end and back-end components can also be independently enhanced or replaced.

The tightly coupled design and efficient implementation ensure stable real-time operation on embedded platforms such as the Jetson Orin NX, providing a reliable foundation for field deployment in underwater net-cage cleaning tasks.

2.6. State Modeling

The state vector adopted in this work follows the standard formulation of tightly coupled visual–inertial odometry, which has been widely validated in prior VIO and VINS frameworks. It consists of the system pose (rotation and position), linear velocity, and inertial sensor biases, forming a minimal yet sufficient representation for describing rigid-body motion under IMU-driven dynamics. This formulation enables consistent propagation and optimization within a sliding-window nonlinear least-squares framework, while avoiding unnecessary state augmentation that would increase computational complexity without improving observability.

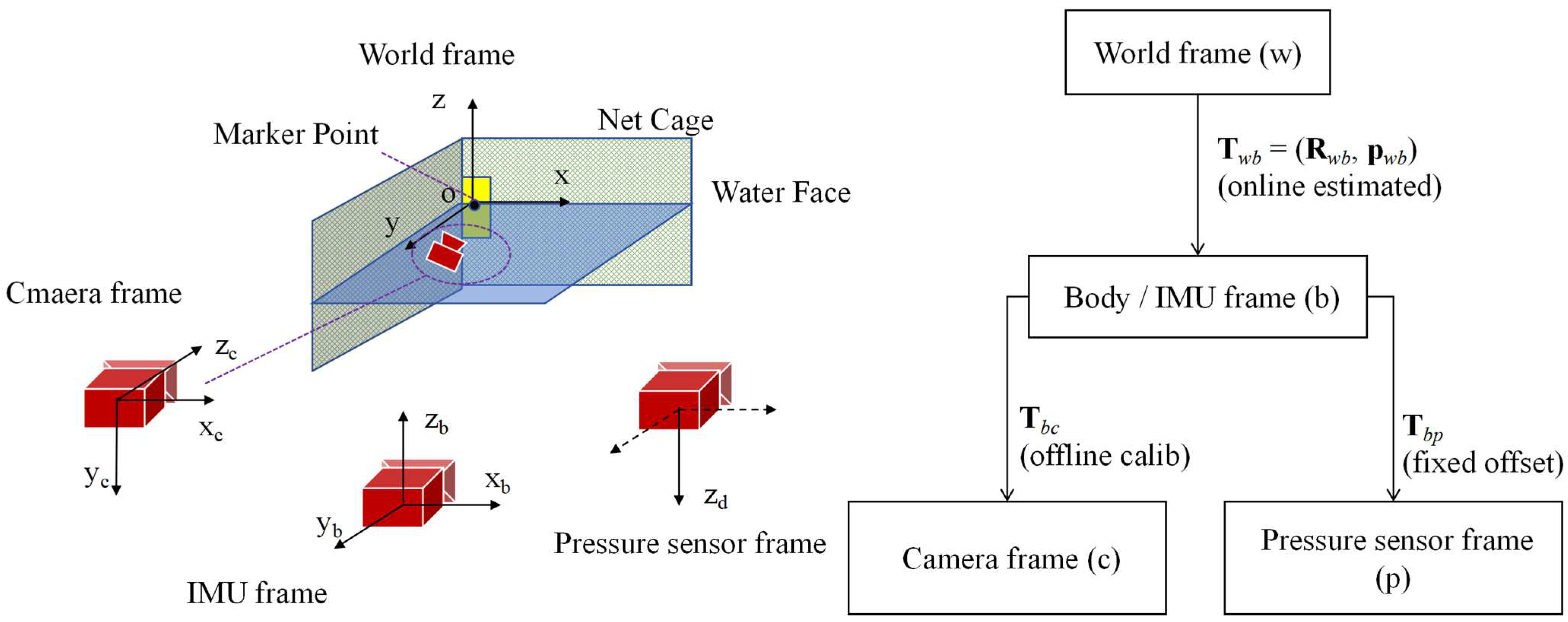

The following coordinate systems are adopted in this study:

World frame (w): A fixed global reference frame defined by the pool cage environment. The reflective-marker anchor frame is aligned with the world frame during initialization. The known 3D coordinates of reflective markers are used to compute the camera pose relative to the anchor frame. At initialization, the reflective fiducial anchor center (marker point) is defined as the origin, with the horizontal plane aligned to the X–Y plane, the Z-axis pointing downward, and the X-axis defined according to the marker orientation. Once established, this frame remains fixed throughout operation.

Body frame (b): Represented by the IMU frame. Since the IMU used in this study is integrated within the stereo camera module rather than at the robot’s center of mass, the body frame is fixed at the camera location. The IMU frame is selected as the body frame in this work, which is a common and well-established choice in visual–inertial odometry systems. This choice is primarily motivated by the fact that the IMU directly measures the system’s angular velocity and linear acceleration, making it the most natural reference frame for modeling rigid-body motion dynamics and state propagation.

By defining the body frame at the IMU, the inertial measurements can be incorporated into the state transition model without introducing additional transformations or coupling terms, thereby simplifying the motion equations and improving numerical stability during IMU pre-integration. This formulation is consistent with standard VIO frameworks such as VINS-Fusion and ORB-SLAM3, where the IMU frame serves as the primary body reference for state estimation.

Although the IMU is not located at the robot’s center of mass, this does not affect estimation correctness, as the relative transformation between the IMU frame and other sensor frames (e.g., camera or depth sensor) is fixed and explicitly modeled through extrinsic calibration. The translational offset is fully accounted for in the observation models, ensuring consistency between motion dynamics and measurement equations. As a result, choosing the IMU frame as the body frame does not degrade estimation accuracy, while offering improved modeling clarity and robustness.

Camera frame (c): Rigidly connected to the body frame. The transformation from the IMU (body) frame to the camera frame is denoted as , which is obtained through offline camera–IMU calibration using Kalibr prior to system deployment and treated as constant during online optimization.

The left and right stereo cameras are denoted as cl and cr, respectively, with their z-axes aligned along the optical axes. The visual observation model is defined in the camera coordinate system.

The relative relationships among the world frame, body (IMU) frame, camera frame, and pressure sensor are illustrated in

Figure 8, together with the corresponding rigid transformations used in the state and observation models.

In our formulation, the extrinsic transformations between sensors are treated as fixed constants obtained from offline calibration, including (IMU-to-camera) and (IMU-to-pressure sensor). The time-varying navigation states , for each keyframe are estimated online within the sliding window. These transformations are used consistently in (i) visual projection factors, which map landmarks from the world frame to the camera frame using and ; (ii) IMU pre-integration factors, defined in the IMU/body frame; and (iii) the depth factor, which compares the measured depth with the world-frame z-component of the pressure sensor position computed from and .

It should be noted that, in the actual system, all sensing components—including the stereo camera, IMU, and pressure sensor—are tightly integrated within a single waterproof enclosure, resulting in small physical offsets between sensor origins.

The coordinate frames in

Figure 8 are therefore shown in a separated manner purely for illustrative purposes, in order to clearly define axis orientations and transformation chains. This schematic representation does not imply large physical separation between sensors. All rigid transformations used in the estimation accurately correspond to the true sensor mounting configuration as determined through offline calibration.

Specifically, the intrinsic parameters of the camera and the inertial sensor noise characteristics are calibrated using imu_utils, while the rigid transformation between the stereo camera and the IMU is jointly calibrated using the Kalibr toolbox. These calibration results provide the fixed transformation used throughout the visual–inertial optimization.

The state vector of a keyframe is defined as:

where

is rotation from the body frame to the world frame,

is the body position in the world frame,

is the body velocity in the world frame,

denote the gyroscope and accelerometer biases, and

is pressure sensor bias. Unlike conventional visual–inertial odometry (VIO) systems, an explicit pressure sensor bias term bp is included in the state vector. This design choice is motivated by the characteristics of low-cost pressure sensors commonly used in underwater robotic platforms.

In practice, depth is obtained from pressure measurements based on hydrostatic relationships, where pressure differences are converted to depth using water density and gravitational acceleration. Although temperature and salinity compensation are applied according to the sensor specifications, residual measurement biases remain unavoidable due to temperature drift, sensor aging, and long-term environmental variations. These effects introduce slowly varying systematic errors that cannot be eliminated through simple offset calibration.

If such bias is left unmodeled, the resulting depth estimate exhibits a persistent offset that directly degrades vertical localization accuracy and propagates into the visual–inertial estimation. To address this issue, the pressure bias is explicitly modeled as a state variable and jointly optimized together with pose, velocity, and IMU biases within the sliding-window framework.

Similar modeling strategies have been shown to be effective in underwater navigation systems that integrate pressure or depth sensing with visual–inertial estimation, where online bias estimation significantly improves vertical consistency and robustness [

30,

33].

The state evolves according to the rigid-body motion equations: The state evolves according to the rigid-body motion equations:

where

,

are the raw IMU measurements,

,

are the associated noise terms, and

is the gravity vector. The state propagation in the sliding window is derived using IMU pre-integration. For a sliding window of size N, the optimization variables include

. Slowly varying parameters such as IMU and pressure biases are either assumed constant or modeled with limited variability across the window.

2.7. Observation Models

Visual observation factor:

A 3D landmark point

expressed in the world frame is projected onto the image plane using the calibrated camera intrinsics and extrinsics:

where

denotes the camera projection function (including distortion),

and

are the rotation and translation of the camera with respect to the world frame.

The residual of the visual observation is defined as the reprojection error between the measured pixel

and the projected pixel

:

IMU pre-integration factor:

The IMU pre-integration factor provides high-frequency motion constraints between consecutive keyframes by integrating raw inertial measurements over time. Unlike visual observations, which may be degraded or temporarily unavailable in underwater environments, the IMU offers continuous measurements of angular velocity and linear acceleration, enabling reliable short-term motion propagation. This factor therefore enforces local motion consistency and bridges gaps caused by visual degradation.

The IMU factor constrains the relative motion between keyframes

and

together with bias evolution:

Here, , , and (and likewise) denote the body orientation, velocity, and position in the world frame. are pre-integrated measurements in the IMU frame at time , already corrected for the bias at . maps a rotation matrix to its corresponding Lie algebra vector (axis-angle representation), is the time interval between keyframes and .

In Equation (5), the IMU factor constrains the relative rotation, velocity, and position between two consecutive keyframes and . Specifically, the pre-integrated measurements encode the accumulated motion from time to in the local IMU frame at time , after compensating for the estimated sensor biases.

The first term corresponds to the rotational residual, which measures the discrepancy between the relative orientation predicted by IMU pre-integration and the orientation difference inferred from the estimated state variables. The second and third terms represent the velocity and position residuals, respectively, enforcing consistency between the inertial pre-integration results and the estimated kinematic evolution over the time interval .

Physically, these residuals ensure that the estimated trajectory adheres to rigid-body motion governed by Newtonian kinematics, while allowing corrections from visual and depth observations during optimization. By jointly optimizing IMU, visual, and depth factors, the system balances short-term inertial accuracy with long-term drift suppression.

Depth observation factor:

The pressure sensor provides an absolute depth constraint. The residual is defined as the difference between the measured depth and the estimated depth of the body frame:

where

is the depth value measured by the pressure sensor.

is the position of the IMU body in the world frame.

is the rotation from the IMU body frame to the world frame.

is the known position of the depth sensor relative to the body frame (obtained via extrinsic calibration), [

]z denotes the z-component (depth) of the vector in the world frame [

34].

Figure 9 shows a graph of local optimization factors. The depth measurement is derived from pressure differences using a hydrostatic model, with density and gravitational parameters provided by the sensor calibration. The pressure bias term accounts for residual systematic errors not captured by this conversion.

2.8. Optimization Framework

The state estimation is formulated as a nonlinear least-squares problem in a fixed-size sliding window. The objective combines visual, inertial, and depth factors:

where

is the set of optimization variables within the sliding window, including the pose

,velocity

, IMU biases

, and pressure bias

for each keyframe

.

represent the visual, IMU, and depth residuals, respectively.

are the covariance matrices associated with each factor, whose inverses (information matrices) weight the confidence of different sensor observations.

The optimization is carried out over a sliding window of 10–15 keyframes. A marginalization strategy is applied to remove old frames while preserving their information as prior constraints for the remaining window. The nonlinear least-squares problem is solved iteratively using the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm, implemented with the Ceres Solver library. Typically, convergence is achieved within 2–3 iterations, ensuring real-time performance.

Noise and uncertainty modeling:

All sensor measurements are modeled as corrupted by zero-mean Gaussian noise, which is a common assumption in visual–inertial state estimation. The confidence of each observation factor is encoded in its corresponding covariance matrix, whose inverse forms the information matrix used to weight residuals in the optimization.

For visual observations, pixel-level reprojection errors are assumed to follow an isotropic Gaussian distribution, with covariance determined by image resolution and feature detection accuracy. For inertial measurements, the IMU noise characteristics (gyroscope and accelerometer noise densities and bias random walks) are obtained from sensor specifications and offline Allan variance analysis, and are incorporated through the standard IMU pre-integration covariance propagation.

For the pressure-based depth measurements, measurement noise arises from sensor resolution, temperature drift, and environmental disturbances. Although initial temperature and density compensation is applied, residual uncertainty remains. This uncertainty is modeled as Gaussian noise with empirically tuned covariance, and the pressure bias term in the state vector further accounts for slowly varying systematic errors.

By explicitly incorporating these covariance models into the optimization, the sliding-window estimator can appropriately balance visual, inertial, and depth constraints, ensuring numerical stability and robust performance under varying underwater conditions.

3. Experiments

3.1. Experimental Objectives

The experimental design aims to validate the feasibility, accuracy, and robustness of the proposed underwater Visual–Inertial–Depth (VID) fusion-based localization method in aquaculture net-cage cleaning scenarios. The specific objectives are as follows:

Pressure–depth factor evaluation: quantify improvements in Z-axis stability when incorporating depth constraints compared to standard VIO.

Anchor-based initialization validation: verify that a single reflective-marker observation ensures consistent world-frame alignment throughout a trajectory.

Environmental adaptability assessment: Conduct experiments in both indoor tank and outdoor net-cage environments, analyzing algorithm stability under conditions of clear water, uneven illumination, and mild turbidity.

Evaluate engineering feasibility: Assess the system’s real-time performance on an embedded platform and its suitability for cleaning operations.

These objectives jointly evaluate both scientific performance and engineering applicability for in-field aquaculture operations.

3.2. Experimental Platform

The localization module was enclosed in an acrylic pressure-resistant housing and mounted onto a commercial ROV for stable experimental maneuvering. The hardware configuration includes: The housing integrated a stereo camera (20 Hz) for visual features and metric scale, an Integrated IMU (100 Hz) for high-frequency motion prediction, a Pressure sensor (20 Hz) for absolute depth measurement, and an embedded Jetson Orin NX computing unit executing the VID estimator in real time under ROS. The Jetson, running Ubuntu with ROS, executed the localization algorithm in real time, with the estimated trajectory continuously visualized in rviz and the 3D pose broadcast during operation. All sensor and state data were recorded in ROS bag files for subsequent offline analysis. For trajectory visualization and quantitative analysis, the estimated pose streams were exported from ROS bags to TUM format, converted to CSV files, and plotted offline.

During preliminary trials, the tracked underwater cleaning robot described earlier exhibited unstable attitude control, which was beyond the focus of this study on localization. Therefore, a commercial ROV was used to ensure stable motion and isolate evaluation to the localization module.

3.3. Experimental Environments

To evaluate the adaptability and robustness of the proposed localization system, experiments were conducted progressively in environments with increasing levels of visual degradation and hydrodynamic disturbance. These environments range from clear, controlled indoor conditions to highly dynamic, real-world ocean settings. A reflective fiducial anchor was deployed in all environments to provide a consistent world-frame reference for initialization and quantitative evaluation.

3.3.1. Air (Baseline Condition)

Handheld motion trials conducted in air served as a clean baseline for system validation. Without underwater optical distortion, turbidity, or illumination changes, this environment allowed verification of the stereo–IMU calibration, anchor-based initialization, and overall estimator stability. The air dataset thus provides an upper bound for localization performance under ideal conditions.

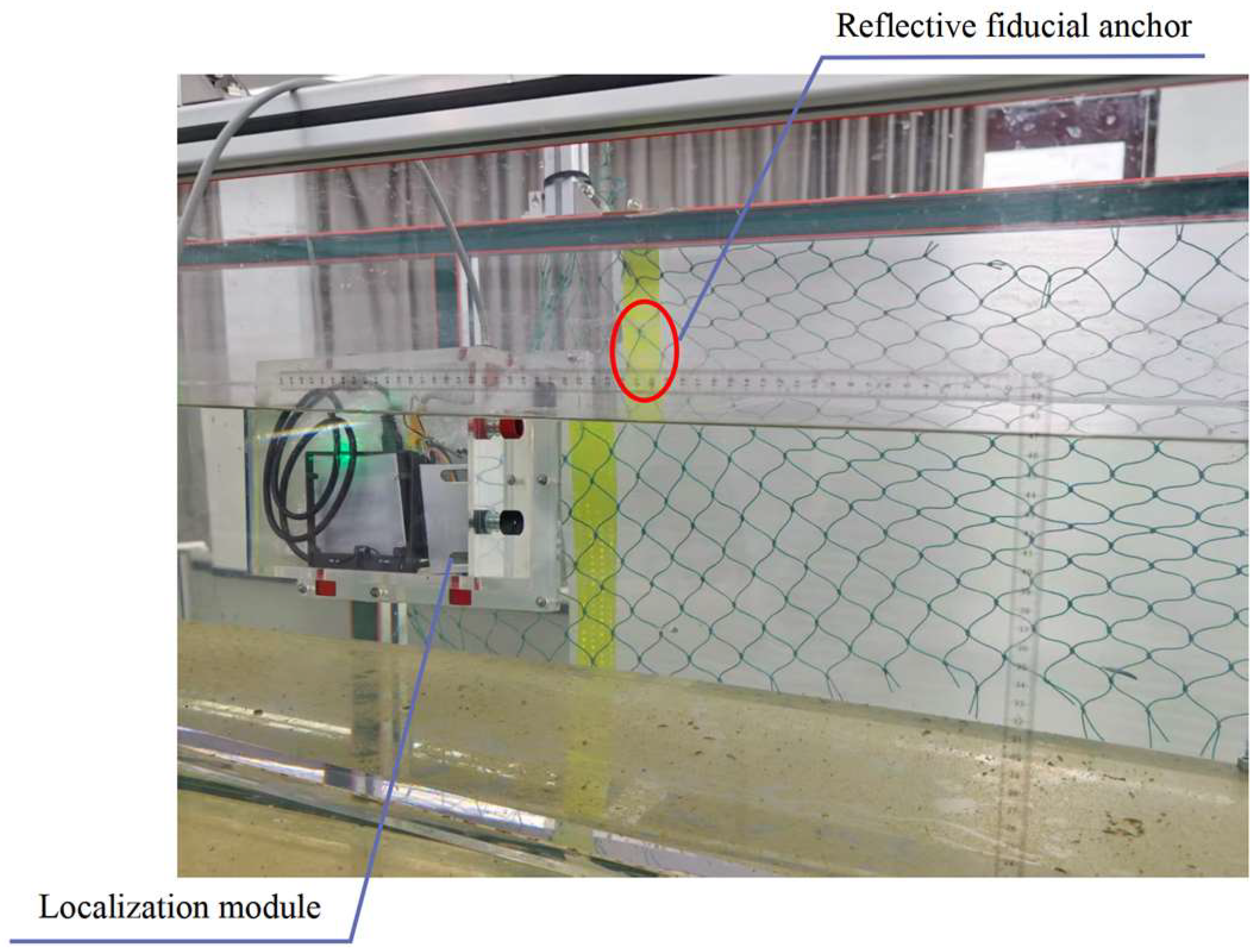

3.3.2. Indoor Water Tank Experiment

The first underwater evaluation was performed in a small tank (

) with uniform lighting and clear water. Nets were suspended along the tank walls, and a reflective fiducial marker was installed to define the global coordinate system. As illustrated in

Figure 10, this controlled setup—characterized by clear water, stable illumination, negligible turbidity and backscatter, well-defined net textures, and high feature detectability—enabled thorough verification of system functionality with minimal underwater interference, thereby serving as a controlled intermediary between in-air trials and open-water pool experiments.

3.3.3. Outdoor Pool Net-Cage Experiment

Further evaluation was conducted in a

outdoor test pool equipped with netting structures to mimic the geometry of aquaculture cages. Artificial fouling materials (e.g., simulated algae) were attached to nets to introduce realistic surface texture and cleaning resistance. Suspended particles were added to emulate planktonic matter, resulting in mild turbidity and moderate image degradation. This environment provided a closer approximation to real-world operating conditions. The experimental arrangement is illustrated in

Figure 11.

3.3.4. Ocean Aquaculture Cage Experiment

The most challenging evaluation was performed in a full-scale marine aquaculture cage (

) under actual farming conditions (

Figure 12). This environment introduced severe visual degradation and dynamic disturbances, including: Strong and unsteady water currents, Air bubbles generated during ROV descent, Significant turbidity caused by suspended sediment and biological fouling, Varying natural illumination and partial occlusions from net structures. These conditions represent the most demanding scenarios for underwater localization and serve as a stress test for the proposed VID fusion system.

In all test settings, fixed reflective fiducial anchors were deployed to initialize and bind the world coordinate frame. During initialization, the robot was oriented toward a designated reflective marker positioned at the junction between the net support and water surface. Each anchor consisted of a rectangular high-reflectance pattern with pre-calibrated dimensions and known placement relative to the net cage. The reflective marker thereby defined the global coordinate frame: the marker center served as the origin (0,0,0), the marker outward normal defined the X-axis, and the vertical upward direction defined the Z-axis. This setup provided a consistent world reference for evaluating localization accuracy across all test environments.

3.4. Experimental Trajectories

In the indoor tests, the robot executed a rectangular trajectory: moving vertically by 20 cm, then horizontally by 30 cm, and finally returning to the starting position. A real-time motion illustration in rviz is shown in

Figure 13. In the figure, the blue transparent cuboid represents the water tank, the yellow cube denotes the reflective fiducial anchor obtained after distance initialization, and the green line depicts the estimated real-time trajectory. The image panel displays the stereo camera’s real-time view with detected feature points, while the terminal window shows the camera’s estimated 3D position relative to the anchor-defined world coordinate origin.

In the outdoor experiments, the robot performed representative maneuvers, including horizontal motion of 2–3 m along the net surface, vertical movements of approximately 0.5 m up and down, and returning to the starting position to form a closed trajectory. These trajectories capture the primary motion patterns encountered in cleaning operations. The ocean aquaculture cage trials followed the same trajectory design as the outdoor pool experiments, ensuring consistency in motion patterns while subjecting the system to more challenging real-world conditions.

3.5. Evaluation Metrics

As GPS or other direct ground-truth references are unavailable underwater, a relative error evaluation strategy was adopted. Specifically, the position at the first initialization with the reflective fiducial anchor was taken as the reference origin. When the robot returned to its starting point, the discrepancy between the estimated position and the anchor’s known relative position was used to quantify accumulated drift. The experiments employed the following relative and indirect metrics, emphasizing system feasibility:

Success Rate (SR): The proportion of trials in which the system continuously produced valid pose estimates throughout the mission.

Anchor Coordinate Error (ACE): The difference between the system-estimated camera position at initialization and the reflective fiducial anchor’s known coordinates, evaluating the accuracy of global alignment.

Loop Closure Drift (LCD per 5 m): The discrepancy between estimated start and end positions after completing a small loop or round trip of at least 5 m in length, normalized per 5 m traveled (unit: m/5 m). A drift of ≤0.5 m per 5 m is acceptable for in net-cleaning.

Together, these metrics reflect both the stability of system operation and the quantitative advantages of the proposed method in drift suppression and global consistency.

3.6. Experimental Procedure

The experiments were conducted in progressive stages, transitioning from static initialization to dynamic motion in each test environment. The overall procedure consisted of five main steps, as detailed below.

With the robot stationary and the reflective marker clearly visible, the system performed an initialization sequence to establish the world coordinate frame. As illustrated in

Figure 14, the stereo camera captured the scene containing the anchor, and the user manually selected a region of interest (ROI) around the marker. The system then detected the reflective pattern and computed the camera-to-anchor distance via stereo triangulation.

- 2.

IMU Bias Estimation and Pressure Offset Calibration.

While the robot remained motionless, IMU data were collected to estimate: the initial gravity direction, gyroscope and accelerometer biases, and the initial pressure offset for depth calibration.

These parameters ensured a physically consistent state initialization before dynamic motion began.

- 3.

Execution of Predefined Trajectories

After initialization, the robot was manually maneuvered along the net surface, following simulated cleaning routes. The motion included horizontal translations, vertical ascents/descents, and turning maneuvers, with speeds of approximately 0.1–0.2 m/s, aiming to cover as much of the net surface as possible. Trajectory design varied by environment. Indoor tank: small rectangular motion to verify core functionality; In the pool experiments, the trajectory consisted of descending from the surface anchor to 0.5 m depth, moving horizontally along the net rope for approximately 2–3 m, and then ascending to return to the starting point. Ocean cage: similar pattern but under turbulent and visually degraded conditions.

These trajectories were selected to maximize coverage of the net surface while providing challenges typical of cleaning operations.

- 4.

Real-Time Onboard VID Fusion

During all experiments, the proposed localization system ran continuously on the Jetson Orin NX at approximately 20 Hz. Data collection included stereo images (20 Hz), IMU measurements (100 Hz), pressure readings (20 Hz), and the robot’s estimated trajectory and 3D spatial positions, all recorded in ROS bag files. The system produced real-time pose estimates used for analysis and shown in RViz.

- 5.

Offline Computation of ACE and LCD Metrics

All raw sensor streams and estimated trajectories were recorded in ROS bag files for offline evaluation. Key performance metrics computed offline included:

Anchor Coordinate Error (ACE): deviation from the known anchor location after initialization;

Loop-Closure Drift (LCD): start–end position deviation normalized per 5 m traveled.

The use of reflective anchors ensured a consistent, physically meaningful world frame across all environments, enabling uniform performance comparison.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results Presentation and Qualitative Trajectory Observations

To preliminarily assess the robustness of the proposed VID-based localization system across different environments, experiments were conducted under four conditions: handheld operation in air, handheld operation in the indoor water tank, and ROV-mounted operation in both the outdoor net-cage pool and the open-sea aquaculture cage. The estimated trajectories obtained in these experiments are presented in

Figure 15. All trajectories shown were obtained from real-world experiments rather than simulations. Specifically, estimated poses were recorded online in ROS bag files during physical trials.

The handheld trials in air (

Figure 15a) and in the indoor tank (

Figure 15b) followed identical motion patterns and observed the same set of reflective anchors, ensuring that any performance differences can be attributed primarily to the change in medium (air versus water). The ROV-mounted experiments carried out in the outdoor pool (

Figure 15c) and the ocean cage (

Figure 15d) represent progressively more challenging conditions, with increasing turbidity, illumination variation, and hydrodynamic disturbance.

- 1.

Air experiment

In the air trial, the camera-to-anchor distance was measured as 0.45 m, while the average estimated distance was 0.42 m, yielding an Average Camera-to-Anchor Error (ACE) of 0.03 m. The robot traversed approximately 1.43 m, with a start-to-end deviation of 0.056 m, corresponding to a Loop-Closure Drift (LCD) ratio of 3.9%. Qualitatively, the estimated trajectory closely matches the ground-truth motion, with clean and stable feature tracking and minimal drift, confirming baseline estimator accuracy in the absence of visual disturbances.

- 2.

Indoor tank experiment

In the indoor tank, the measured camera-to-anchor distance was 0.38 m, while the average estimated distance was 0.33–0.34 m, resulting in an ACE of about 0.04–0.05 m. The robot traveled approximately 1.96 m, with a start-to-end deviation of 0.046 m, giving an LCD ratio of 2.3%. As seen in

Figure 15b, the underwater trajectory exhibits slightly more fluctuation than the air case, reflecting moderate visual degradation from the aquatic medium. Nevertheless, the overall trajectory remains highly consistent with the intended path, indicating that the VID-based estimator remains robust under clear-water conditions with uniform lighting. The pressure factor effectively constrains the Z-axis, and visual tracking continues to perform reliably.

- 3.

Outdoor pool net-cage experiment

In the outdoor pool, the camera-to-anchor ground-truth distance was 0.56 m, while the estimated distance was 0.72 m, yielding an ACE of 0.16 m. The robot traversed approximately 13.4 m along a trajectory that included diving 0.5 m, moving left by about 2.5 m, ascending to the surface, and then returning to the starting point, producing an LCD of 0.734 m (5.5% of the traveled distance). Qualitatively, propeller-induced bubbles during diving intermittently obstructed the camera view, causing temporary loss of visual features and increased drift in the XY-plane. However, fusion with the IMU and pressure sensor effectively constrained the Z-axis, so vertical estimates remained accurate. During clearer segments, especially during horizontal motion near the net surface, the multi-sensor fusion algorithm showed more stable behavior. Although the errors in this experiment are larger than in the tank case, they remain within acceptable limits for coverage planning in cleaning tasks. Part of the discrepancy can be attributed to slight horizontal drift at initialization: when the system was activated, the ROV was not perfectly stationary relative to the cage, causing an offset between the true starting point and the initial estimated pose.

- 4.

Ocean aquaculture cage experiment

In the ocean cage, the camera-to-anchor distance was measured as 0.36 m, while the estimated distance was 0.42 m, giving an ACE of 0.06 m. The total traveled distance was approximately 16.05 m, and the LCD was 1.323 m, yielding a drift ratio of 8.3%. The motion sequence consisted of moving left along the net by about 2.5 m, diving 0.5 m, then returning rightwards and ascending to the initial point. At the water surface, localization performance remained satisfactory. However, during diving, strong currents occasionally pushed the robot away from the cage, leading to loss of visual features and forcing corrective maneuvers to re-approach the net, which were themselves unstable and introduced additional error. Bubbles generated by the thrusters, as well as the disturbance of fouling materials attached to the cage net, further degraded image quality and often rendered the scene visually turbid, making reliable feature extraction difficult. Under such conditions, the trajectory exhibits pronounced XY drift, while Z remains well constrained by depth sensing. These behaviors are consistent with the expected dominance of non-visual cues (IMU and pressure) when visual information becomes unreliable.

Overall,

Figure 15 shows that as the environment transitions from air to tank to outdoor pool and finally to open-sea conditions, trajectory smoothness and closure gradually degrade, yet remain interpretable and traceable to identifiable environmental causes.

4.2. Quantitative Results

The quantitative results of localization accuracy across the four environments are summarized in

Table 3, including travel distance, measured and estimated camera-to-anchor distances, ACE, and LCD.

Across all environments, the mean ACE is approximately 0.08 m, with the maximum error below 0.2 m, which is sufficient for practical net-cleaning operations. The loop-closure drift increases with travel distance and environmental complexity but remains within ≤0.5 m per 5 m in the tank and outdoor pool experiments, meeting the design target for coverage planning and repeated-path execution.

It should be noted that all ocean-cage trajectories reported in this paper were obtained from real-world online experiments, and all trajectories correspond to actual robot motion recorded in ROS bag files. However, when replaying the same rosbag data offline, the system may fail to reinitialize and report warnings such as “feature tracking not enough, please slowly move your device!”. This behavior is not caused by disabling the depth factor or by inherent limitations of the proposed VID framework, but rather by the data acquisition conditions at the beginning of the recording.

In the ocean experiments, rosbag recording started while the platform was already moving at the sea surface under wave-induced disturbance, resulting in insufficiently stable visual features during the initialization window. As a result, the standard VINS-Fusion initialization assumptions—namely quasi-static motion and sufficient feature tracks—are violated during offline replay. During the actual sea trials, initialization was successfully completed when the robot was positioned in front of the reflective fiducial anchor for distance measurement, where the platform attitude was relatively stable. In contrast, in indoor tank experiments, the robot remained stationary for a longer duration before motion, enabling robust and repeatable initialization both online and offline. To illustrate this difference, an additional indoor tank comparison is provided in

Figure 16, where both pure VIO and VID configurations can be reliably initialized.

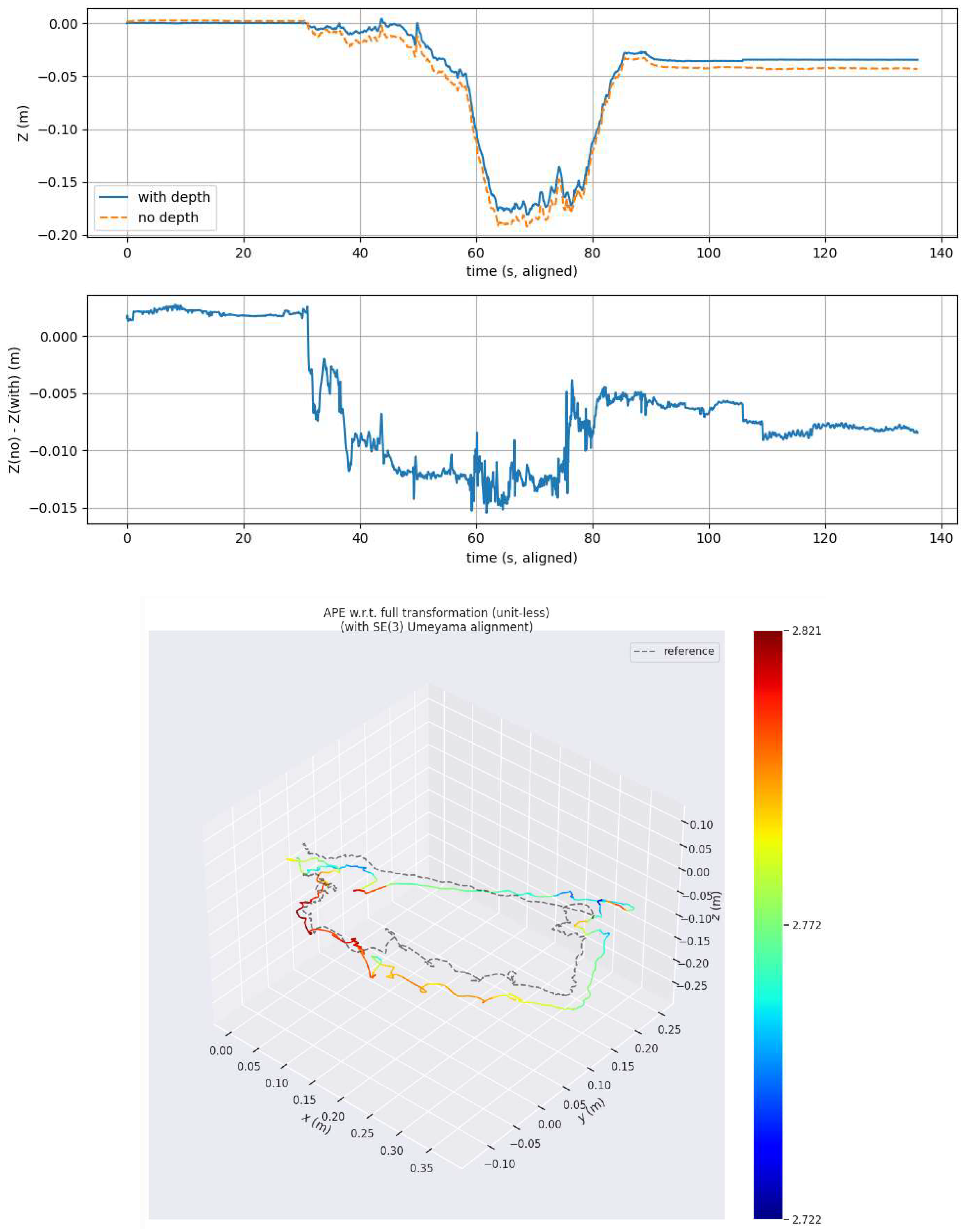

To further examine the role of the pressure-based depth factor, an ablation study was conducted in the indoor tank environment by disabling the depth constraint while keeping all other system components unchanged. Under clear-water conditions with sufficient visual features, the pure VIO configuration is able to complete the trajectory and maintain a reasonable Z-axis estimate. Compared with the proposed VID framework, incorporating depth sensing slightly reduces vertical fluctuations and improves the temporal stability of the Z-axis estimate. As shown in

Figure 16, the benefit of the depth factor in this setting is modest but consistent, indicating that while visual–inertial cues dominate in clear conditions, depth sensing provides an additional stabilizing constraint.

In the ocean aquaculture cage experiments, however, the contribution of depth sensing becomes substantially more pronounced due to severe degradation of visual information. While localization performance remains satisfactory near the water surface, visual tracking frequently deteriorates during diving as a result of strong currents, bubble generation, turbidity, and disturbance of fouling materials attached to the cage net. Under these conditions, pure visual–inertial estimation increasingly relies on inertial propagation, leading to pronounced drift in the horizontal plane and unstable depth estimates. In contrast, the inclusion of the pressure-based depth factor provides an absolute vertical reference, effectively preventing unbounded Z-axis divergence even when visual observations are temporarily unavailable.

As a result, although the overall trajectory in the ocean environment exhibits larger loop-closure drift compared with tank and pool experiments, the estimated motion remains physically interpretable and vertically consistent. This behavior highlights that while depth sensing plays a complementary role in clear and structured environments, it becomes a critical constraint for maintaining localization stability in visually degraded and hydrodynamically dynamic open-sea conditions.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Findings

The experimental results across air, indoor tank, outdoor pool, and ocean aquaculture environments reveal several consistent patterns that validate the effectiveness of the proposed VID fusion approach.

First, the system demonstrates high initialization reliability, as indicated by the low Anchor Coordinate Error (ACE) values (0.03–0.06 m) across all conditions. The reflective fiducial anchor provides a stable global frame that prevents heading drift and ensures that all trajectories are expressed in a physically meaningful cage coordinate system. This is essential for tasks such as coverage planning and region-of-interest-based cleaning.

Second, the integration of the pressure-depth factor provides strong Z-axis stability. Regardless of the presence of bubbles, turbidity, or intermittent visual dropout, the vertical estimates remain tightly constrained. In contrast, removing the depth factor causes significant Z-axis divergence within only a few meters of motion—consistent with known failure modes of underwater VIO.

Third, the system exhibits moderate and explainable XY drift under visually degraded conditions. Visual degradation—including bubbles during ROV descent, turbidity from disturbed fouling, and partial occlusion of the camera by droplets—causes temporary reductions in feature quantity. The severity of XY drift correlates directly with the degradation level: air < indoor tank < outdoor pool < ocean aquaculture cage.

Finally, robustness increases progressively from air to ocean environments due to the multimodal fusion design. Even in the most challenging open-sea cage experiments, the trajectory remains interpretable, and vertical drift remains bounded, confirming that depth and inertial cues compensate for unreliable visuals.

5.2. Comparison with Previous Studies

Relative to existing underwater SLAM/localization approaches, the proposed system differs in several aspects:

Versus acoustic solutions (DVL/USBL/LBL): Acoustic methods achieve high accuracy but require costly equipment, external beacons, or seabed infrastructure. Their deployment and maintenance are complex, especially in aquaculture cages.

In contrast, the proposed system uses only onboard sensors (camera, IMU, pressure sensor), significantly reducing cost and simplifying deployment while avoiding acoustic multipath and noise interference.

Versus pure visual SLAM: Monocular or stereo-only SLAM systems deteriorate rapidly under turbidity, low texture, and bubble occlusions—all typical of aquaculture cages. They cannot guarantee consistent metric scale or depth stability. Our approach overcomes these weaknesses through tight coupling with the pressure sensor, which restores Z-axis observability and improves robustness under weak visuals.

Versus conventional VIO: Classical VIO systems diverge in the vertical direction underwater due to refraction, degraded lighting, low contrast, and sparse features. The proposed pressure-depth factor explicitly corrects this limitation, making the system viable in aquaculture operations.

Versus previous underwater SLAM studies: Many prior works validate their methods only in pools, test tanks, or controlled lab conditions. Our work includes real ocean aquaculture cage trials, exposing challenges such as: strong currents, biological fouling and sediment, turbulence and net-induced occlusion, bubble plumes during ROV adjustments, and poor illumination.

This broader evaluation highlights both strengths and failure cases, providing a more realistic assessment of the method’s applicability.

5.3. Limitations in Real-World Deployment

Despite its strengths, several limitations remain, particularly evident in ocean trials:

Horizontal drift in dynamic water. While the pressure term constrains depth, X/Y errors accumulate under strong currents and during unstable corrective maneuvers to re-approach the net.

Sensitivity around initialization. If the platform is not fully stationary relative to the cage during anchor-based initialization, a small initial offset can propagate through the trajectory.

Visual degradation factors. Bubble plumes during diving, turbidity caused by disturbed fouling on the net, and occasional droplet occlusion on the acrylic housing after surfacing can reduce usable features and induce temporary tracking failures.

Limited experimental coverage. The conducted trials were restricted to shallow cages and near-shore conditions, with relatively short durations and limited trajectory lengths. Stronger currents, harsher turbidity, and nighttime operations remain to be systematically assessed in future large-scale deployments.

Lack of high-precision ground truth underwater. Performance evaluation relied on relative metrics such as anchor alignment error and loop-closure drift, since centimeter-grade ground truth systems were not available. In practice, the robot’s rectangular trajectory straight-line motion of approximately 6–7 m was extended to nearly 16 m due to oscillations and drift caused by surface waves and currents, illustrating how environmental disturbances can enlarge the effective path length and complicate error quantification.

These limitations indicate that while the method is effective in structured cages with modest disturbance, further improvements are needed for broad, ocean deployment.

5.4. Engineering Applicability

From a system-integration and operational standpoint, the proposed method is highly practical for aquaculture robots.

Adequate accuracy for coverage planning. In controlled settings (indoor tank, outdoor pool), LCD ≤ 0.5 m per 5 m meets operational requirements for net-cleaning coverage estimation.

Reduction in labor and safety risks. By enabling semi-autonomous navigation, the system reduces reliance on manual cleaning and diver-based operations, which are both labor-intensive and hazardous.

Deployable and cost-efficient. The system uses only COTS sensors and runs at 20 Hz on a Jetson Orin NX—making it suitable for embedded deployment on lightweight aquaculture robots.

Applicability to real-world cages. Although drift increases in open-sea conditions, errors remain interpretable and largely attributable to identifiable disturbances. This suggests that improvements in vehicle control and visual robustness would directly improve localization accuracy.

Foundation for full autonomy. Because the coordinate frame aligns with the net cage via the reflective anchor, the robot can directly map which areas of the net surface have been cleaned—enabling closed-loop cleaning coverage algorithms.

5.5. Future Research Directions

The experimental findings highlight several important directions for future improvement:

Visual enhancement under turbidity. Apply underwater image restoration, learning-based dehazing, and bubble suppression to improve feature extraction in degraded scenes [

35,

36].

Use of active visual beacons (LED markers). Yellow or green LED fiducials offer higher robustness under low-light and turbid conditions.

Improved vehicle stability. Integration with crawler-type robots or mesh-gripping mechanisms can resist currents and prevent displacement away from the cage.

Adaptive multi-sensor fusion. Dynamically down-weight visual factors during severe visual degradation and rely more on inertial and depth cues.

Long-term trials in ocean cages. Extended mission evaluation is needed to assess long-range consistency and robustness under fully realistic conditions.

Effects of water droplets and housing design. Adding hydrophobic coatings or active wipers can reduce droplet interference during surface transitions.

6. Conclusions

This study addressed the localization challenge for underwater net-cleaning robots operating in GNSS-denied aquaculture environments. A lightweight and cost-effective Visual–Inertial–Depth (VID) fusion framework was developed by extending VINS-Fusion with a pressure-depth factor for enhanced Z-axis observability, a reflective-anchor-assisted initialization strategy for stable global alignment, and tightly coupled stereo–IMU fusion for robust metric estimation. The system was implemented in real time (20 Hz) on a Jetson Orin NX, forming a practical and deployable multi-sensor solution using only commercial off-the-shelf components.

The proposed framework was validated progressively in air, indoor tanks, outdoor net-cage pools, and real ocean aquaculture cages. Across structured environments, the system demonstrated stable operation with mean ACE values of 0.05–0.16 m, maximum errors below 0.2 m, and loop-closure drift (LCD) within ≤0.5 m per 5 m—satisfying task-level requirements for cleaning coverage planning. In open-sea conditions, performance degraded due to currents, turbidity, bubble interference, and droplet occlusion, yielding an LCD of approximately 1.32 m over a 16.05 m trajectory (8.3%). Nevertheless, the fused depth and IMU cues effectively prevented unbounded divergence, confirming the robustness and practicality of the approach under harsh, real-world disturbances.

Future work will focus on extending field trials to full-scale sea cages for long-term evaluation; developing lightweight and adaptive fusion algorithms to down-weight unreliable visual cues; introducing LED beacons or active anchors for improved performance under weak textures; and integrating the method with crawler-based cleaning robots equipped with cage-gripping mechanisms to counteract current-induced displacement. Additional improvements targeting initialization stability, bubble mitigation, and optical clarity will further enhance the system’s resilience.

In summary, the proposed VID framework provides accurate, real-time, and low-cost localization for structured aquaculture cages, while ocean trials offer actionable insights for future refinement. Continued advancements along these directions will strengthen robustness and support reliable automation of underwater net-cleaning operations in real farming environments.