NeRF-Enhanced Visual–Inertial SLAM for Low-Light Underwater Sensing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Underwater SLAM Challenges and Classical Approaches

2.2. Learning-Based Feature Extraction and Scene Understanding

2.3. Underwater Image Enhancement for SLAM

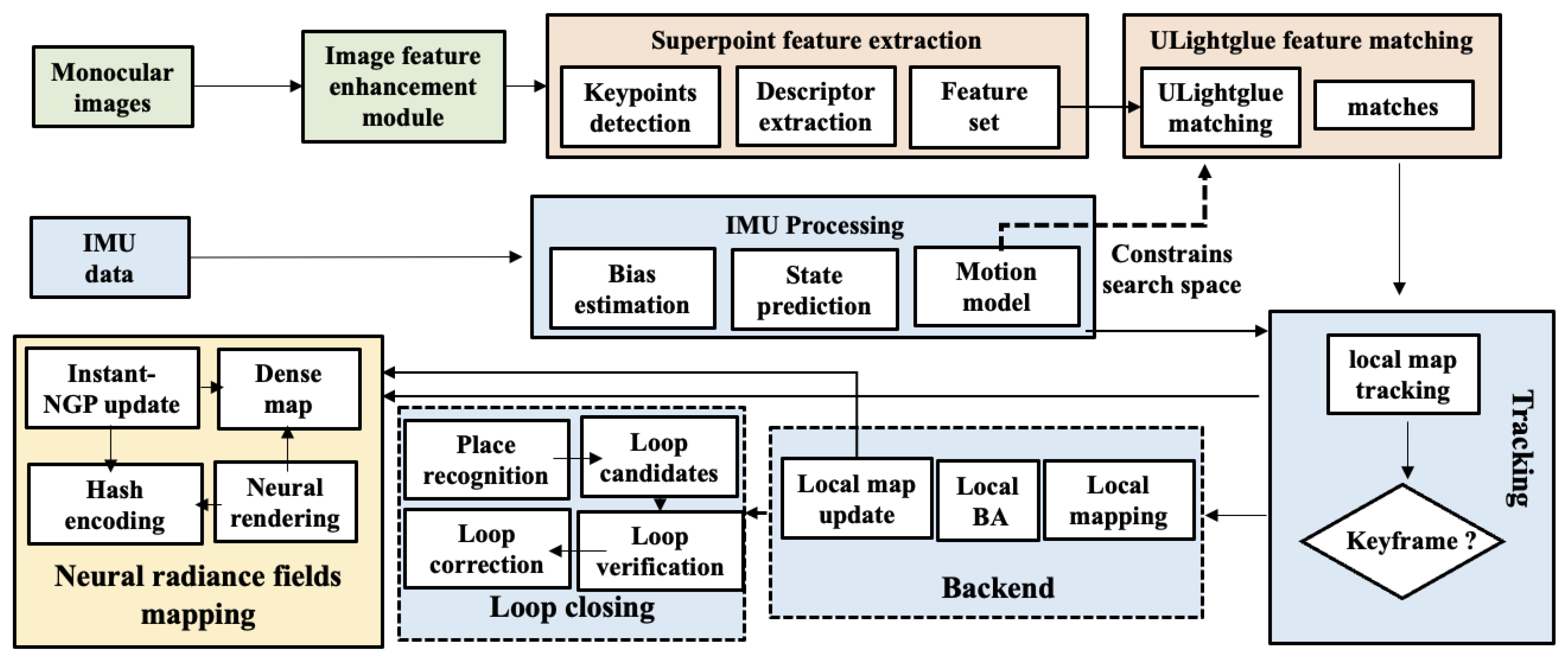

3. Materials and Methods

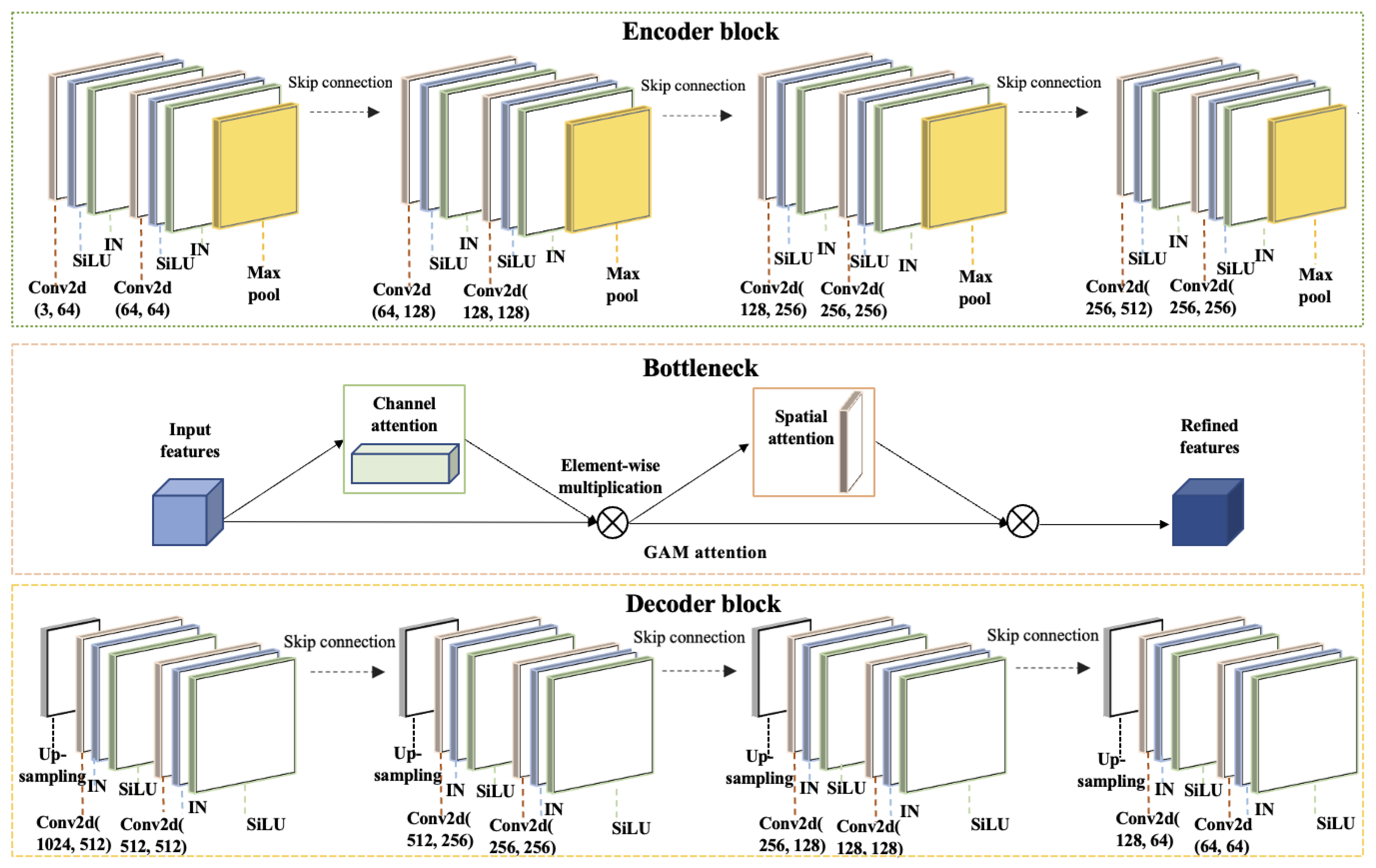

3.1. Underwater Low-Light Image Enhancement Module

3.1.1. Encoder

3.1.2. Bottleneck Layer

3.1.3. Decoder

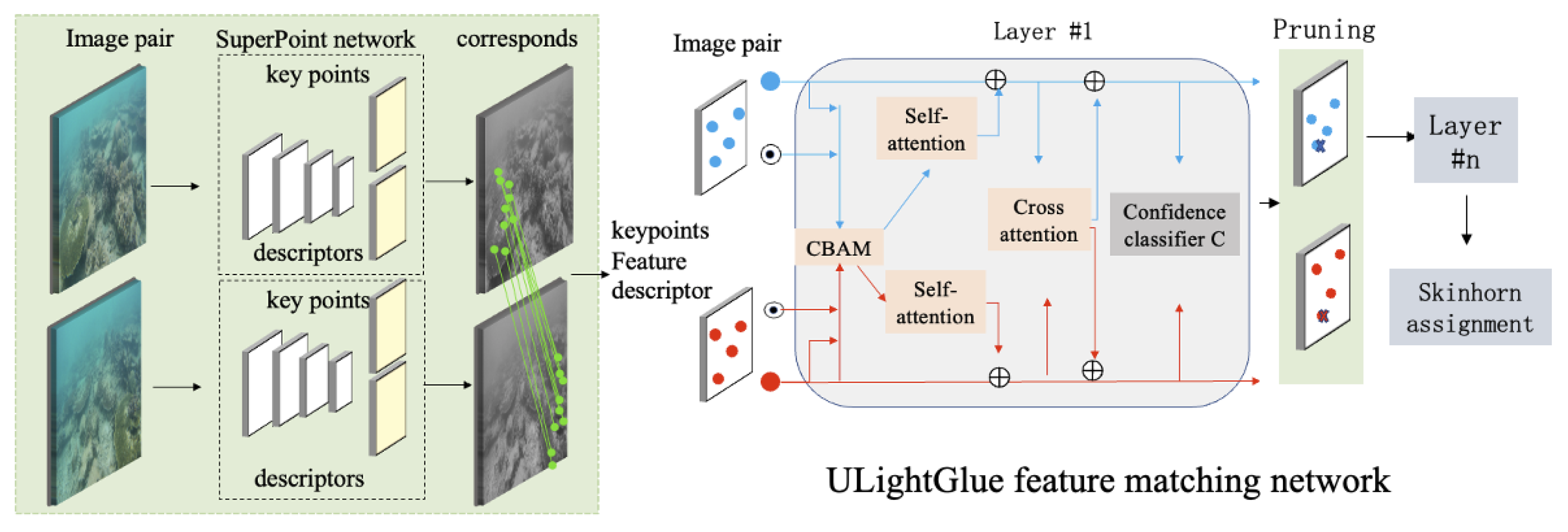

3.2. Feature Extraction and Matching Network for Underwater Low-Light Environments

3.2.1. Robust Feature Extraction Module

3.2.2. ULightGlue: CBAM-Enhanced Feature Matching

Matching Pseudo-Code

- 1.

- Input: An image pair .

- 2.

- Extract SuperPoint keypoints and descriptors from A and B.

- 3.

- Linearly project descriptors to a common embedding and form for both sides.

- 4.

- Enhance features with CBAM (channel then spatial) on A and B to obtain and (see equations below and Figure 3).

- 5.

- Refine within-image context using self-attention on and .

- 6.

- Exchange information with cross-attention between A and B to compute a similarity matrix S.

- 7.

- Compute match probabilities with the matching head (dual-softmax); keep mutual top-1 pairs above a confidence threshold to form and report confidences .

- 8.

- Output: Mutual top-1 matches and their confidences , obtained after mutual check and confidence thresholding.

3.2.3. Post-Matching Processing

- Robust estimation (RANSAC): This paper fit essential matrices and homographies via RANSAC to ensure spatial geometric consistency and remove outliers.

- Confidence thresholding: Only matches above a confidence threshold are retained to reduce false matches.

3.3. IMU Fusion for Robust Pose Estimation

3.3.1. IMU’s Role in SLAM

3.3.2. Visual–Inertial Joint Optimization

- Adaptability to lighting changes: In complete darkness or high turbidity, IMU provides stable short-term pose prediction when visual SLAM loses features

- Drift correction: IMU acceleration measurements constrain monocular SLAM’s scale drift

- Improved optimization accuracy: Visual–inertial joint optimization corrects visual estimation errors

3.4. Underwater Dense Mapping Based on NeRF

NeRF Modeling Pipeline

- Camera parameter initialization: Using SLAM-estimated intrinsic and extrinsic parameters to ensure geometric consistency

- Training with enhanced underwater images: Since NeRF relies on photometric consistency, using low-light enhanced images improves adaptation to underwater lighting variations

3.5. Loss Function Design and Optimization

3.5.1. NeRF Reconstruction Loss

3.5.2. ColorSSIM Loss

3.5.3. NimaLoss

4. Results

4.1. Datasets

4.1.1. AquaLoc Harbor Sequences

4.1.2. AquaLoc Archaeological Sequences

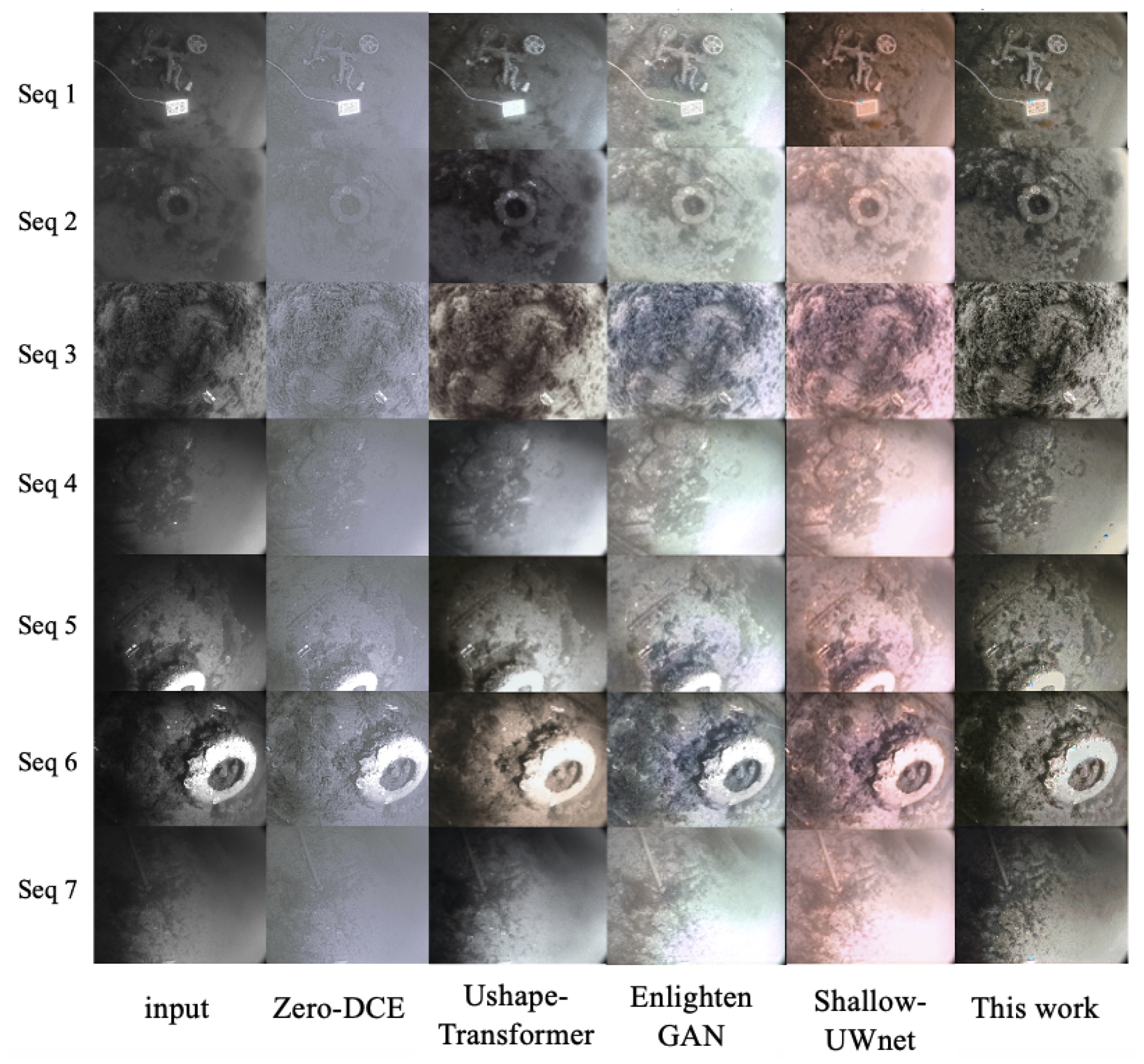

4.2. Image Enhancement Performance Analysis

4.2.1. Image Enhancement Evaluation Metrics

4.2.2. Image Enhancement Comparative Experiments

4.3. The Role of Underwater Feature Extraction Matching Network in SLAM

4.4. SLAM-Focused Experiments

4.4.1. Evaluation Metrics

4.4.2. Comparative Experiments

4.4.3. Harbor SLAM Performance

4.4.4. Archaeological Sequences Comparative Results

4.4.5. Ablation Study

4.5. Novel View Reconstruction Results Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Image Enhancement Results

5.2. Discussions of the Role of Underwater Feature Extraction Matching Network in SLAM

5.3. SLAM Performance Analysis

5.3.1. Harbor SLAM Results

5.3.2. Archaeological SLAM Results

5.4. Novel View Reconstruction Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.; Fan, X.; Shi, P.; Ni, J.; Zhou, Z. An overview of key SLAM technologies for underwater scenes. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eustice, R.M.; Singh, H.; Leonard, J.J.; Walter, M.R. Visually mapping the RMS Titanic: Conservative covariance estimates for SLAM information filters. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2006, 25, 1223–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Li, A.Q.; Rekleitis, I. Svin2: An underwater slam system using sonar, visual, inertial, and depth sensor. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Macau, China, 3–8 November 2019; pp. 1861–1868. [Google Scholar]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Tardós, J.D. Orb-slam2: An open-source slam system for monocular, stereo, and rgb-d cameras. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2017, 33, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.; Elvira, R.; Rodríguez, J.J.G.; Montiel, J.M.; Tardós, J.D. Orb-slam3: An accurate open-source library for visual, visual–inertial, and multimap slam. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 37, 1874–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeTone, D.; Malisiewicz, T.; Rabinovich, A. Superpoint: Self-supervised interest point detection and description. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 224–236. [Google Scholar]

- Sarlin, P.E.; DeTone, D.; Malisiewicz, T.; Rabinovich, A. Superglue: Learning feature matching with graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 4938–4947. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberger, P.; Sarlin, P.E.; Pollefeys, M. Lightglue: Local feature matching at light speed. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 17627–17638. [Google Scholar]

- Bescos, B.; Fácil, J.M.; Civera, J.; Neira, J. DynaSLAM: Tracking, mapping, and inpainting in dynamic scenes. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 4076–4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Skinner, K.A.; Eustice, R.M.; Johnson-Roberson, M. WaterGAN: Unsupervised generative network to enable real-time color correction of monocular underwater images. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2017, 3, 387–394. [Google Scholar]

- Akkaynak, D.; Treibitz, T. Sea-thru: A method for removing water from underwater images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 1682–1691. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Yu, Z.; Yu, X.; Zheng, B. Lighting the darkness in the sea: A deep learning model for underwater image enhancement. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 921492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yu, Z.; Zheng, B. ULL-SLAM: Underwater low-light enhancement for the front-end of visual SLAM. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1133881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Tang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Xiang, D.; Xiao, M. An Improved Underwater Visual SLAM through Image Enhancement and Sonar Fusion. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2512. [Google Scholar]

- Ribas, D.; Ridao, P.; Neira, J. Underwater SLAM for Structured Environments Using an Imaging Sonar; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 65. [Google Scholar]

- Bahr, A.; Leonard, J.J.; Fallon, M.F. Cooperative localization for autonomous underwater vehicles. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2009, 28, 714–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildenhall, B.; Srinivasan, P.P.; Tancik, M.; Barron, J.T.; Ramamoorthi, R.; Ng, R. Nerf: Representing scenes as neural radiance fields for view synthesis. Commun. ACM 2021, 65, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucar, E.; Liu, S.; Ortiz, J.; Davison, A.J. imap: Implicit mapping and positioning in real-time. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 6229–6238. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Anwar, S.; Porikli, F. Underwater scene prior inspired deep underwater image and video enhancement. Pattern Recognit. 2020, 98, 107038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, C.; Pizzoli, M.; Scaramuzza, D. SVO: Fast semi-direct monocular visual odometry. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–7June 2014; pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, T.; Evans, A.; Schied, C.; Keller, A. Instant neural graphics primitives with a multiresolution hash encoding. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2022, 41, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Simoncelli, E.P.; Bovik, A.C. Multiscale structural similarity for image quality assessment. In Proceedings of the The Thrity-Seventh Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems & Computers, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 9–12 November 2003; Volume 2, pp. 1398–1402. [Google Scholar]

- Talebi, H.; Milanfar, P. NIMA: Neural image assessment. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 3998–4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrera, M.; Creuze, V.; Moras, J.; Trouvé-Peloux, P. AQUALOC: An underwater dataset for visual–inertial–pressure localization. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2019, 38, 1549–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panetta, K.; Gao, C.; Agaian, S. Human-visual-system-inspired underwater image quality measures. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2015, 41, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Li, C.; Guo, J.; Loy, C.C.; Hou, J.; Kwong, S.; Cong, R. Zero-reference deep curve estimation for low-light image enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 1780–1789. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, A.; Swarnakar, A.; Mittal, K. Shallow-uwnet: Compressed model for underwater image enhancement (student abstract). In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Online, 2–9 February 2021; pp. 15853–15854. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, L.; Zhu, C.; Bian, L. U-shape transformer for underwater image enhancement. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 3066–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Gong, X.; Liu, D.; Cheng, Y.; Fang, C.; Shen, X.; Yang, J.; Zhou, P.; Wang, Z. Enlightengan: Deep light enhancement without paired supervision. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 2340–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.; Koltun, V.; Cremers, D. Direct sparse odometry. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 40, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, R.; Demmel, N.; Cremers, D. LDSO: Direct sparse odometry with loop closure. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Madrid, Spain, 1–5 October 2018; pp. 2198–2204. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, C.; Zhang, Z.; Gassner, M.; Werlberger, M.; Scaramuzza, D. SVO: Semidirect visual odometry for monocular and multicamera systems. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2016, 33, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasinghe, C.; Rathnaweera, A.; Maithripala, S. U-VIP-SLAM: Underwater visual-inertial-pressure SLAM for navigation of turbid and dynamic environments. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 3193–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.M.; Tseng, Y.C.; Hsu, Y.C.; Shi, X.Q.; Hua, Y.H.; Yeh, J.F.; Chen, W.C.; Chen, Y.T.; Hsu, W.H. Orbeez-SLAM: A Real-time Monocular Visual SLAM with ORB Features and NeRF-realized Mapping. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), London, UK, 29 May–2 June 2023; pp. 9400–9406. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Description | IMU Support | Underwater Applicable | NeRF Applicable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORB-SLAM2 [4] | Sparse feature matching + loop closure | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| ORB-SLAM3 [5] | ORB-SLAM2 with IMU | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| DSO [31] | Sparse direct method | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| LDSO [32] | DSO with feature points | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| SVO [33] | Semi-direct method | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| U-VIP-SLAM [34] | Visual–inertial pressure fusion | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Orbeez-SLAM [35] | ORB-SLAM2 with NeRF-realized mapping | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Method | Seq1 | Seq2 | Seq3 | Seq4 | Seq5 | Seq6 | Seq7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORB-SLAM2 | ✗ | 0.442 | 0.031 | ✗ | 0.148 | 0.115 | ✗ |

| DSO | ✗ | 0.634 | 0.258 | ✗ | 0.673 | 0.245 | ✗ |

| LDSO | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 0.78 | ✗ |

| SVO | 0.490 | 0.562 | 0.266 | ✗ | ✗ | 0.0823 | ✗ |

| ORB-SLAM3 (no IMU) | 0.514 | 0.201 | 0.158 | ✗ | 0.302 | 0.142 | ✗ |

| ORB-SLAM3 (with IMU) | 0.514 | 0.201 | 0.158 | ✗ | 0.302 | 0.142 | ✗ |

| U-VIP-SLAM | 0.254 | 0.334 | 0.014 | 1.093 | 0.126 | 0.043 | 0.704 |

| Orbeez-SLAM | ✗ | 0.436 | 0.042 | ✗ | 0.144 | 0.109 | ✗ |

| This work | 0.249 | 0.351 | 0.018 | 1.010 | 0.114 | 0.054 | 0.712 |

| Method | ORB-SLAM3 | DROID-SLAM | DXSLAM | VINS-Mono | SVIn2 | This Work |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence 1 | ✗ | 0.402 | 0.108 | 1.282 | 0.231 | 0.176 |

| Sequence 2 | ✗ | 0.109 | ✗ | ✗ | 2.440 | 0.082 |

| Sequence 3 | ✗ | 0.090 | 0.154 | ✗ | 0.280 | 0.057 |

| Sequence 4 | 1.450 | ✗ | 2.931 | 1.093 | ✗ | 0.893 |

| Sequence 5 | 0.263 | 0.101 | 0.135 | 0.302 | 2.721 | 0.114 |

| Sequence 6 | ✗ | 0.121 | ✗ | 1.093 | 0.609 | 0.096 |

| Sequence 7 | 1.468 | 0.218 | 0.891 | 1.372 | 1.053 | 0.125 |

| Sequence 8 | 0.101 | 0.129 | 0.153 | 1.216 | 0.247 | 0.094 |

| Sequence 9 | ✗ | 0.237 | 0.036 | 0.528 | 1.509 | 0.157 |

| Sequence 10 | 0.343 | 0.218 | 0.550 | 0.472 | 2.371 | 0.201 |

| Sequence | Enhancement + Traditional Matching (ORB) | No Enhancement + IMU + Traditional Matching (ORB) | Enhancement + IMU + Traditional Matching (ORB) | No Enhancement + IMU + Superpoint + ULightGlue | Enhancement + Superpoint + ULightGlue | This Work |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 0.351 | 0.361 | 0.328 | 0.307 | 0.293 | 0.249 |

| 02 | 0.327 | 0.313 | 0.365 | 0.311 | 0.346 | 0.351 |

| 03 | 0.027 | 0.159 | 0.024 | 0.143 | 0.022 | 0.018 |

| 04 | 1.193 | ✗ | 1.227 | 1.174 | 1.171 | 1.010 |

| 05 | 0.135 | 0.296 | 0.231 | 0.265 | 0.129 | 0.114 |

| 06 | 0.062 | 0.148 | 0.064 | 0.143 | 0.060 | 0.054 |

| 07 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 1.362 | 1.418 | 0.712 |

| Method | Metric | Seq1 | Seq2 | Seq3 | Seq4 | Seq5 | Seq6 | Seq7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-DCE | UIQM ↑ | 0.7955 | 0.7441 | 0.9317 | 0.8149 | 0.8526 | 0.8853 | 0.7940 |

| UCIQE ↑ | 0.2255 | 0.2113 | 0.2358 | 0.2392 | 0.2475 | 0.2760 | 0.2327 | |

| Entropy ↑ | 5.8002 | 5.2741 | 6.4291 | 6.5125 | 6.5019 | 7.0024 | 6.2224 | |

| BRISQUE ↓ | 19.9897 | 18.6711 | 18.6962 | 18.9460 | 19.5515 | 19.4909 | 18.9793 | |

| NIQE ↓ | 7.7055 | 7.5817 | 7.4891 | 8.0262 | 7.5846 | 7.5628 | 8.0030 | |

| U-shape Transformer | UIQM ↑ | 0.9057 | 0.9307 | 0.9065 | 0.7552 | 0.9031 | 0.9153 | 0.7685 |

| UCIQE ↑ | 0.3238 | 0.3623 | 0.333 | 0.3410 | 0.3815 | 0.3523 | 0.3816 | |

| Entropy ↑ | 6.9079 | 6.9867 | 7.3971 | 7.6678 | 7.6160 | 7.5289 | 7.6277 | |

| BRISQUE ↓ | 18.7233 | 18.3398 | 17.9371 | 18.4870 | 18.1504 | 17.9974 | 18.1754 | |

| NIQE ↓ | 7.1752 | 5.1420 | 6.5793 | 4.8326 | 5.4725 | 5.6198 | 5.2366 | |

| EnlightenGAN | UIQM ↑ | 0.9336 | 0.9222 | 0.9302 | 0.8814 | 0.9176 | 0.8972 | 0.8694 |

| UCIQE ↑ | 0.2250 | 0.2101 | 0.2642 | 0.2363 | 0.2465 | 0.2907 | 0.2287 | |

| Entropy ↑ | 6.9588 | 6.6930 | 7.0863 | 7.1678 | 7.1654 | 7.3643 | 6.9132 | |

| BRISQUE ↓ | 19.3139 | 18.3069 | 18.6682 | 18.9870 | 19.1707 | 19.6137 | 18.8209 | |

| NIQE ↓ | 6.7237 | 6.5303 | 7.1036 | 7.0057 | 6.8601 | 7.1935 | 7.0622 | |

| Shallow-UWnet | UIQM ↑ | 0.9548 | 0.9379 | 0.9312 | 0.8692 | 0.9477 | 0.9438 | 0.8756 |

| UCIQE ↑ | 0.2230 | 0.2074 | 0.2573 | 0.2349 | 0.2426 | 0.2865 | 0.2261 | |

| Entropy ↑ | 6.9079 | 6.6563 | 7.1956 | 7.1678 | 6.9957 | 7.4194 | 6.7808 | |

| BRISQUE ↓ | 17.5433 | 17.3073 | 17.5076 | 18.5058 | 17.6585 | 17.7670 | 18.1249 | |

| NIQE ↓ | 5.3895 | 5.0876 | 6.5083 | 5.1091 | 5.6672 | 6.0896 | 5.4278 | |

| This work | UIQM ↑ | 0.9675 | 0.9472 | 0.9495 | 0.9524 | 0.9545 | 0.9621 | 0.9428 |

| UCIQE ↑ | 0.3149 | 0.3183 | 0.3449 | 0.3337 | 0.3474 | 0.3712 | 0.3680 | |

| Entropy ↑ | 7.1892 | 7.3633 | 7.6642 | 7.4236 | 7.3558 | 7.5855 | 7.5404 | |

| BRISQUE ↓ | 19.8165 | 18.4204 | 18.5951 | 18.7886 | 19.2285 | 19.2808 | 18.8700 | |

| NIQE ↓ | 7.1419 | 7.1526 | 7.6035 | 7.4334 | 7.2404 | 7.2551 | 7.7188 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Zheng, B. NeRF-Enhanced Visual–Inertial SLAM for Low-Light Underwater Sensing. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010046

Wang Z, Zhang Q, Hu Y, Zheng B. NeRF-Enhanced Visual–Inertial SLAM for Low-Light Underwater Sensing. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010046

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhe, Qinyue Zhang, Yuqi Hu, and Bing Zheng. 2026. "NeRF-Enhanced Visual–Inertial SLAM for Low-Light Underwater Sensing" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010046

APA StyleWang, Z., Zhang, Q., Hu, Y., & Zheng, B. (2026). NeRF-Enhanced Visual–Inertial SLAM for Low-Light Underwater Sensing. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010046