Abstract

Global container shipping faces increasing pressure to reduce fuel consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions while still meeting strict port schedules under highly uncertain terminal operations and met-ocean conditions. However, most existing voyage-planning approaches either ignore real port operation variability or treat fuel optimization and just-in-time (JIT) arrival as separate problems, limiting their applicability in actual operations. This study presents a data-driven just-in-time voyage optimization framework that integrates port-side uncertainty and marine environmental dynamics into the routing process. A dwell-time prediction model based on Gradient Boosting was developed using port throughput and meteorological–oceanographic variables, achieving a validation accuracy of R2 = 0.84 and providing a data-driven required time of arrival (RTA) estimate. A Transformer encoder model was constructed to forecast fuel consumption from multivariate navigation and environmental data, and the model achieved a segment-level predictive performance with an R2 value of approximately 0.99. These predictive modules were embedded into a Deep Q-Network (DQN) routing model capable of optimizing headings and speed profiles under spatially varying ocean conditions. Experiments were conducted on three container-carrier routes in which the historical AIS trajectories served as operational benchmark routes. Compared with these AIS-based baselines, the optimized routes reduced fuel consumption and CO2 emissions by approximately 26% to 69%, while driving the JIT arrival deviation close to zero. The proposed framework provides a unified approach that links port operations, fuel dynamics, and ocean-aware route planning, offering practical benefits for smart and autonomous ship navigation.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Maritime transport carries over 80% of global trade and accounts for around 2.9% of global CO2 emissions. To address this, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) adopted the 2023 IMO GHG Strategy, targeting net-zero emissions by around 2050 with intermediate reduction goals for 2030 and 2040 [1]. In this context, energy-efficient ship routing under variable marine environmental conditions has become increasingly important [2].

Recent advances in maritime digitalization show that AI-based routing can achieve approximately 3–5% annual fuel reductions per vessel, while just-in-time arrival has been reported to yield around 14% fuel savings per voyage [3,4]. However, most routing studies still neglect port-side uncertainty, particularly the variability of berth dwell time driven by port capacity and queuing processes, which leads to early-arrival waiting, excess fuel consumption, and reduced schedule reliability, despite recent IMO initiatives emphasizing the synchronization of vessel arrivals with port readiness [5].

With JIT arrival, it is paramount to estimate dwell time primitively and subsequently make routing decisions based on the corresponding RTA. To achieve this goal, this work provides an integrated approach that utilizes machine learning models for dwell-time prediction coupled with reinforcement learning-based route optimization under RTA constraints, which is designed to support improved energy efficiency and schedule reliability in ship operations.

1.2. Related Works

1.2.1. Fuel Consumption Prediction

Research on fuel-efficient and time-reliable ship operation spans three major areas: fuel consumption prediction, JIT arrival prediction, and optimal route generation. Earlier studies modeled these components separately, but recent work increasingly integrates data-driven prediction with decision-making frameworks.

In fuel consumption prediction, early regression-based models relied on vessel speed, draft, engine load, and sea state [6], but struggled to capture nonlinear relationships and temporal variability. Deep learning models later combined navigational and marine environmental data [7], while meta-learning approaches [8] and hybrid XGBoost-PSO methods [9] further improved accuracy. Despite this progress, existing models still face limitations in representing complex temporal dependencies and nonlinear interactions among environmental variables.

1.2.2. JIT Arrival and Port Operations

In JIT arrival planning, the objective is to meet the port’s required time of arrival (RTA) while reducing waiting time and fuel consumption. The IMO’s Just-in-Time Arrival Guide (2021) highlights the importance of integrating port operational information with predictive models [4]. Complementing the IMO guideline, the DCSA’s “Standards for a Just-in-Time Port Call” (2020) further emphasizes the need for standardized timestamp definitions and real-time data exchange among carriers, terminals, and port authorities, providing a practical framework for implementing JIT operations in real-world port-call processes [10]. Prior work developed JIT scheduling systems combining ETA prediction and berth allocation [11], and speed-adjustment strategies leveraging real navigational data to reduce fuel use and emissions [12]. In parallel, Iris et al. addressed port-side operational optimization by formulating an integrated berth allocation and quay crane assignment problem (BACAP) [13]. Venturini et al. jointly optimized berth allocation and sailing speed (arrival time) with fuel/emission considerations in a multi-port setting [14]. Nevertheless, most JIT-related studies concentrate primarily on ETA prediction and speed optimization. A critical limitation is that the variability of berth dwell time—driven by berth occupancy, cargo-handling volume, and berthing delays—is not predicted but treated as a fixed or statistical constant, despite being a decisive factor for JIT feasibility and accurate RTA estimation. Relatedly, from the berth-scheduling perspective, Golias et al. explicitly treated vessel arrival time as a decision variable to jointly reduce port waiting–related impacts and delayed departures, underscoring the value of coordinating arrival timing with berth readiness [15].

1.2.3. Optimal Ship Routing and Deep Reinforcement Learning

Research on optimal ship routing aims to simultaneously achieve fuel efficiency, reduced travel time, and navigational safety by incorporating time-varying ocean environmental conditions. Early studies adopted classical optimization techniques such as the isochrone method, dynamic programming (DP), variational approaches, and graph search algorithms like Dijkstra/A* [16]. Subsequent work proposed enhanced methods, including 3D dynamic programming that jointly optimizes speed and heading [17], weather-forecast-driven genetic algorithms [18], AIS-based data-driven routing [19], improved isochrone formulations [20], and the VISIR-2 routing framework integrating physical ocean models [21].

While these approaches offer physically interpretable and stable solutions, they exhibit structural limitations such as increased computational cost due to spatial discretization, insufficient representation of environmental uncertainty, and simplified fuel consumption modeling.

More recent research incorporates deep reinforcement learning (DRL) to jointly optimize heading and speed. Studies such as Guo et al. [22], Moradi et al. [23], Lee & Kim [24], and Latinopoulos et al. [25] demonstrated that DQN- or DRL-based routing systems can adapt to dynamic environments and support autonomous navigation. In particular, Shin and Yang proposed a DQN-based framework that jointly optimizes vessel path planning and safe anchorage allocation, highlighting that DRL can also handle port-approach and anchorage decisions in an integrated manner [26]. However, most of these works focus on single objectives or limited environmental factors.

In addition to the standard DQN, many improved deep reinforcement learning algorithms have been proposed to enhance stability, sample efficiency, and exploration [27]. Double DQN and dueling DQN reduce Q-value overestimation and decompose the action-value function into separate value and advantage streams [28,29], while prioritized experience replay and Rainbow-style architectures combine multiple extensions into a more robust DQN framework [30,31]. On the actor–critic side, algorithms such as Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) and Soft Actor–Critic (SAC) support continuous or high-dimensional action spaces and have been widely adopted in control and robotics applications [32,33]. These methods provide powerful alternatives for sequential decision-making under uncertainty and can, in principle, be combined with maritime routing environments.

1.3. Research Gap

Despite substantial progress in weather–current routing, fuel consumption modeling, and port-operation analysis, these research streams have largely evolved in isolation. Existing methods, therefore, lack an integrated framework that aligns voyage planning with port operational readiness while explicitly optimizing fuel consumption.

First, most routing studies generate optimal trajectories or speed schedules under wind, wave, current, and bathymetric conditions. However, they rarely incorporate uncertain port-side factors that contribute to the time constraint of the route planning—particularly berth availability and the stochastic nature of berth dwell time—which critically influence early-arrival waiting, unnecessary fuel consumption, and schedule-coordination failures. As a result, routing strategies developed in simulation remain disconnected from real port conditions, making them impractical for operational use.

Second, port-performance studies have developed machine-learning models that predict berth dwell time from container-handling volumes, berth productivity, weather conditions, and arrival patterns. Yet these predictions are not integrated into real-time voyage planning; thus, dwell-time forecasts have no influence on route selection, dynamic speed control, or RTA determination. This lack of a closed-loop linkage between port-congestion prediction and navigation decision-making remains a major gap.

Third, fuel consumption prediction models—especially Transformer-based time-series models with multi-modal environmental inputs—have achieved high accuracy, but only a few studies incorporate predicted fuel consumption into the reward structure of RL-based route optimization. Even fewer explicitly integrate full marine environmental fields (wind, waves, currents, and bathymetry) with RL-based navigation policies.

Fourth, RL-based routing models such as DQN or Actor–Critic typically consider bathymetry, obstacle avoidance, and environmental resistance, yet seldom include schedule-sensitive constraints such as RTA or JIT arrival requirements. Consequently, existing methodologies fail to handle the practical challenge of synchronizing voyage schedules with port operational readiness.

To date, no previous work has proposed an integrated framework combining (1) port dwell-time prediction, (2) multi-modal fuel consumption prediction, and (3) DQN-based routing under RTA constraints for JIT-oriented voyage planning. This research void limits the development of practical, energy-efficient, and schedule-consistent decision-support systems that jointly account for port operations, marine environments, and ship-route optimization.

2. Data Materials

2.1. Data Frame

The data frame constructed in this study integrates navigation measurements, marine environmental data, and port operation information. All datasets were merged using unified timestamps and geographical coordinates, forming a comprehensive database for subsequent modeling.

2.1.1. Port Operation Data

Port operation data were collected from the Pusan New Port International Terminal (PNIT) through publicly available schedule information. The dataset contains vessel arrival and departure times, berth allocation, cargo handling volume (TEU), operation type, Alternative Maritime Power (AMP) connection status, and operational conditions influenced by weather.

Dwell time was calculated as the difference between the actual arrival and departure timestamps. Cargo volume per vessel was computed as the sum of discharged, loaded, and shifted containers. Voyage-level schedule variability was additionally examined to ensure consistency and reliability.

2.1.2. Voyage Measurement Data

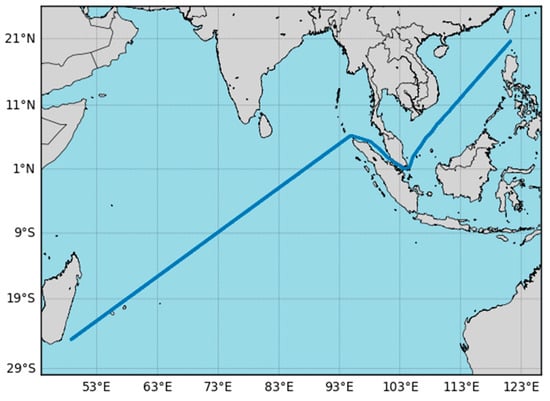

Voyage measurement data consist of real-world navigation records collected at 10-min intervals, amounting to 2018 sequential observations. This dataset contains latitude, longitude, speed over ground, heading, engine power expressed in megawatts, and elapsed time in days. As illustrated by the trajectory map presented in Figure 1, the data represent repeated long-haul operations of a 24,000 TEU container vessel operating between Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Speed and heading provide critical information on the ship’s dynamic state, while power measurements reflect the vessel’s propulsion characteristics during the voyage. In this study, fuel consumption at each time step is computed by multiplying the measured engine power by a specific fuel oil consumption (SFOC) value of 150 g/kWh, allowing the model to translate propulsion power into an equivalent fuel-use rate. The characteristics of the vessel used in this study are summarized in Table 1, which presents the principal particulars of an HMM 24,000 TEU-class container ship. To provide a structured overview of the variables included in this navigation dataset, Table 2 summarizes the list of navigation parameters and their descriptions.

Figure 1.

Ship navigation routes used for machine learning.

Table 1.

Principal particulars of the 24,000 TEU-class container vessel.

Table 2.

List of navigation data.

2.1.3. Weather and Geographical Data

The marine environmental data used in this study consist of wind and wave information obtained from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Global Forecast System (GFS) and WAVEWATCH III (WW3) models. The GFS dataset provides atmospheric fields through the zonal and meridional wind components (wind u and wind v), which were matched to the vessel’s position using nearest-grid extraction across the study region. Wave conditions from the WW3 model include significant wave height, peak wave period, and wave direction, aligned spatially with the GFS domain. Because both datasets are available at a coarser temporal resolution of one to three hours, linear interpolation was applied to synchronize them with the 10 min navigation records. This procedure produced continuous environmental variables along the vessel’s trajectory, enabling their use in the fuel consumption prediction model and the route optimization framework. To provide a clearer overview of the environmental variables used in this study, representative samples of the atmospheric fields and the wave parameters are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Representative samples of GFS atmospheric data used in this study.

Table 4.

Representative samples of WW3 wave data used in this study.

3. Research Method

3.1. Research Approach

The voyage planning optimization procedure proposed in this study consists of three stages designed to integratively reflect uncertainties in port operations and variations in the marine environment: the berth dwell-time prediction module, the fuel consumption prediction module, and the reinforcement learning-based optimal route generation module.

First, the berth dwell-time prediction module constructs a Gradient Boosting Regressor-based prediction model using inputs such as port container throughput, wind speed, and meteorological variables. The training dataset is restricted to intervals consistent with the typical dwell-time distribution of container vessels (24–48 h) and the policy-based upper limit (72 h), thereby enabling the uncertainty of port operations to be reflected in the estimation of the RTA.

Second, the fuel consumption prediction module integrates navigational and marine environmental data in a time-series format and adopts a Transformer encoder-based regression architecture. Through the input projection layer and positional encoding, temporal information is embedded, and the multi-head self-attention mechanism, combined with nonlinear feed-forward layers, enables the model to learn the temporal and multivariate interactions governing fuel consumption. The predicted fuel consumption is directly used to compute the fuel-cost term in the reinforcement learning reward function.

Third, the optimal route generation module defines the state using ship position, remaining distance, remaining time, and marine environmental conditions, and applies an action space composed of direction–speed combinations to train a DQN-based routing policy. The reward function consists of the fuel-cost term, the ETA–RTA time-penalty term, and the safety-penalty term associated with shallow water and hazardous-area avoidance. Using experience replay and a target network, the learning process yields an optimal route that simultaneously improves fuel efficiency and schedule adherence.

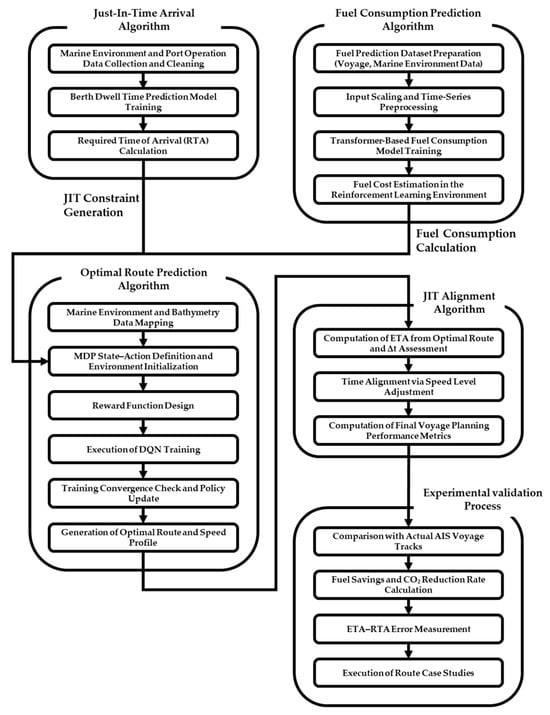

Finally, the learned route undergoes a post-processing speed-adjustment procedure that refines segment-wise travel time so that the arrival-time error (Δt) converges within a permissible range, thereby achieving JIT arrival. This integrated approach effectively combines port-operation prediction with marine-environment-based routing decisions, enabling practical voyage optimization grounded in real-world maritime data. Figure 2 provides an overview of the schematic diagram of this research.

Figure 2.

Research framework of the proposed voyage optimization method.

In the case studies, the historical AIS trajectory for each route is used as a benchmark representing the traditional voyage plan implemented in actual operations. The DQN-based optimized route generated by the proposed framework is quantitatively compared against this AIS benchmark in terms of fuel consumption, CO2 emissions, and schedule adherence (ETA–RTA deviation).

3.2. Design Variables

In this study, the design variables are defined as the elements optimized through the reinforcement learning-based route-generation process. The vessel’s navigational state is represented on a discrete grid by the position vector , and the agent selects a two-component action , where denotes one of the eight discrete heading directions and denotes the vessel’s speed level chosen from a predefined speed set ν. In this study, the speed set is defined as knots. Together with the remaining time to the RTA , and the remaining distance to the destination , these variables constitute the core design parameters in the optimization process. The remaining distance is computed as the great-circle distance between the vessel’s current grid-cell position rt and the destination coordinates using the haversine formula. The next waypoint is determined through the geographical transition function fgco, which updates the vessel’s position based on the selected action At by advancing the ship along a great-circle arc. In practice, fgco(·) implements a one-step geographical update in which the segment length between rt and rt+1 is computed via the haversine formula and applied in the heading direction indicated by the chosen course–speed action. The overall motion update follows the transition rule

By iteratively applying this transition, the sequence of waypoints forms the complete route

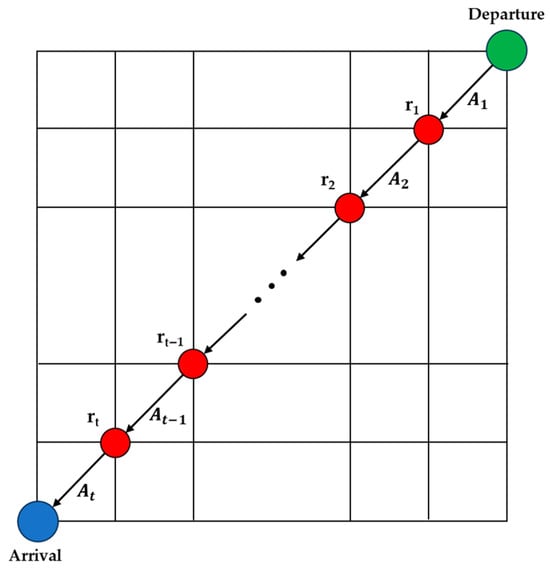

representing the vessel’s full navigation path generated by the reinforcement learning agent. Figure 3 illustrates this waypoint-transition mechanism, where each grid point corresponds to rt and the displacement between waypoints reflects the direction–speed action pair At.

Figure 3.

Definition of waypoint sequence and segment-wise speed vt in the grid-based route R.

Likewise, the temporal deviation from the RTA is computed as

This serves as a key time-related design variable tightly coupled with speed adjustments. Here, ETAt denotes the estimated time of arrival at decision step t and is computed as , where tdep is the departure, and is the travel time of segment k computed from its distance and the selected speed level. Accordingly, the time increment per decision step is variable and is computed as , where is the great-circle (haversine) distance between consecutive grid waypoints, and is the selected speed level. Collectively, these variables govern route geometry, fuel-cost dynamics, schedule adherence, and safe navigation under environmental conditions, enabling the reinforcement learning agent to generate fuel-efficient and RTA-compliant optimal routes.

3.3. Dwell-Time Prediction Model

3.3.1. Input and Output Definition

The input vector xt ∈ R6 for dwell-time prediction is constructed using port operation records and local meteorological–oceanographic data, and consists of the following six elements:

Here, container is cargo handling volume in TEU (loading/unloading workload), windspeed is wind speed near the port, airtemp is air temperature near the port, relative humidity is humidity near the port, airpress is atmospheric pressure near the port, and watertemp is seawater temperature near the port.

The target variable yt is defined as the port dwell time of the vessel, measured in seconds. The prediction model is formulated as the following nonlinear regression function:

Here, denotes the function implemented by a Gradient Boosting Regressor, and θ represents the set of model parameters.

3.3.2. Data Refinement and Construction of the Training Dataset

To remove outliers in the vessel’s port dwell time, this study employed a filtering procedure that retains only the dwell-time interval of as the training dataset. For container vessels, the typical and desirable dwell-time range is generally presented as 24–48 h [34], and several port-operation policies set the target dwell time for vessels and cargo to be within 72 h (three days) [35]. This is because dwell times exceeding 72 h are highly likely to result from various factors such as vessel maintenance, terminal congestion, or other operational irregularities.

3.3.3. Model Structure

This study adopts a Gradient Boosting-based ensemble regression structure to capture the nonlinear relationships between port operational variables and environmental factors. The model employs a stage-wise residual learning procedure, in which weak learners—implemented as Decision Tree Regressors—are sequentially fitted to minimize the residuals from previous stages. Through this mechanism, the model effectively accounts for nonlinear patterns and interaction effects among variables, enabling the representation of complex dependencies between operational conditions and environmental inputs. In addition, the ensemble structure ensures stable learning performance even when the available dataset is of limited size. The final trained function fθ produces the estimated dwell time for each port call, and this predicted value is subsequently utilized to compute the required time of arrival (RTA) within the reinforcement learning-based optimal route generation framework.

For implementation, the berth dwell-time model employs the GradientBoostingRegressor from scikit-learn. The dataset is randomly split into training and test subsets with a ratio of 80:20, and the random seed is fixed to 42 for reproducibility (random_state = 42). The final model uses 100 regression trees (n_estimators = 100) with a learning rate of 0.1 (learning_rate = 0.1), while other tree-level hyperparameters follow the scikit-learn defaults, including max_depth = 3, subsample = 1.0, min_samples_split = 2, min_samples_leaf = 1, and the squared-error loss. This configuration corresponds to the dwell-time prediction model that is saved and later deployed within the proposed voyage-planning framework.

To evaluate the predictive capability of the proposed dwell-time model, this study employs standard regression metrics, including the mean squared error (MSE), the root mean squared error (RMSE), and the coefficient of determination (R2). These metrics are used to assess the model’s ability to capture the underlying relationships between the input variables and the observed dwell times and to verify its suitability for integration into the subsequent reinforcement learning framework.

3.4. Fuel Consumption Prediction Model

3.4.1. Input and Output Definition

To construct the input data for fuel consumption prediction, the navigation dataset and the marine environmental dataset were temporally aligned along a common time axis. The feature vector at time t consists of navigation variables and marine environmental variables. A structured summary of all input features and the target variable is presented in Table 5. The output variable yt represents the fuel consumption per unit time, and its predicted value is incorporated into the fuel-cost term F(R, vt) of the reinforcement learning-based optimal route generation model.

Table 5.

Input and output variables for fuel consumption prediction model.

3.4.2. Data Preprocessing and Sliding Window Construction

Because fuel consumption exhibits strong temporal dependencies, the input data were preprocessed to preserve the sequential characteristics of the underlying time series. The navigation and environmental variables were first aligned to a uniform time interval, with outliers removed and missing values interpolated to ensure consistency across all features. A sliding window of length L was then applied to construct input sequences of the form [xt−L+1, …, xt], enabling the model to capture the accumulated effects of environmental and operational conditions. The dataset was subsequently partitioned into training and validation segments in chronological order to reflect the temporal structure of the data. Through this preprocessing pipeline, the model was provided with inputs that appropriately encode the cumulative influence of external factors on fuel consumption.

3.4.3. Transformer Model

In this study, a Transformer encoder-based fuel consumption prediction model was constructed to accurately capture the temporal interactions between navigational and environmental variables. The input sequence is formed using a sliding window of length L, where each time step includes navigational features—such as vessel speed, position, and water depth—as well as marine environmental variables including wind speed, wind direction, wave height, and wave period. These multivariate inputs are projected into the model’s embedding dimension through a linear projection layer, and sinusoidal positional encoding is added to provide temporal ordering information.

The Transformer Encoder consists of multi-head self-attention, which computes interactions across multiple time steps in parallel, and a position-wise feed-forward network that performs nonlinear transformations. This architecture effectively captures long-range dependencies and nonlinear temporal patterns, demonstrating superior representational capacity for complex environmental variability compared with sequential models such as LSTM. In this study, multiple Encoder blocks were stacked to model the combined effects of wind–wave variability and vessel operating conditions across the voyage interval.

The final output of the Transformer model corresponds to the predicted fuel consumption per unit time, which is directly incorporated into the fuel-cost term F(R, vt) within the reinforcement learning-based route optimization module. This integration enables a consistent decision-making framework between the fuel prediction model and the optimal route generation process.

3.4.4. Optimizing Transformer Model

In this study, automatic hyperparameter optimization was conducted using the Optuna framework, following the methodology introduced by Akiba et al. (2019), to improve the performance of the Transformer-based fuel consumption prediction model [36]. Optuna employs the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE), a Bayesian optimization algorithm that models the probabilistic relationship between hyperparameters and model performance, thereby prioritizing the exploration of promising regions in the search space.

The hyperparameters subject to optimization included the model dimension, the number of attention heads, the feed-forward network dimension, the dropout rate, the number of encoder layers, and the batch size. The search ranges for these hyperparameters are summarized in Table 6. The model dimension, Head number, and feed-forward dimension were sampled as integers within their respective continuous ranges, while the number of layers and the batch size were chosen from discrete sets. The dropout rate was sampled from a continuous interval [0.001, 0.1] to simultaneously account for model capacity and regularization.

Table 6.

Hyperparameter grid for the transformer algorithm to predict fuel consumption.

The optimization process consisted of 50 trials. For each trial, a candidate set of hyperparameters proposed by Optuna was used to train the model, after which the coefficient of determination (R2) and the Mean Squared Error (MSE) were computed on the validation set. The objective function was defined to minimize the validation MSE, while the R2 value served as a supplementary indicator of predictive performance. This procedure ensured that the selected hyperparameters yielded strong generalization on the temporally separated validation segment.

The optimal hyperparameter configuration identified through this search is presented in Table 7. Specifically, the model dimension was set to 72, the number of attention heads to 2, the feed-forward network dimension to 88, the dropout rate to 0.05, the number of encoder layers to 5, and the batch size to 16. This configuration achieved a favorable balance between model complexity, computational efficiency, and regularization, and was ultimately adopted as the final architecture for computing the fuel-cost term in the reinforcement learning-based optimal route generation module.

Table 7.

Final hyperparameters for the transformer algorithm to predict fuel consumption.

3.5. Route Optimization Module

The optimal route generation model is designed to simultaneously achieve three operational objectives: reducing fuel consumption, ensuring schedule compliance based on the RTA, and maintaining navigational safety under varying marine environmental conditions. Throughout the route-searching process, the vessel continuously selects speed and course at each time step by considering diverse meteorological, oceanographic, and navigational factors, and these sequential decisions directly influence future states and overall voyage performance. Consequently, the route selection problem can be regarded as a sequential decision-making problem in which states evolve over time, and each action accumulates into long-term outcomes. To address this, a reinforcement learning–based policy training framework is adopted. This section formulates the route optimization problem as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) and details the design of the state and action spaces, the reward structure, and the DQN architecture used for policy learning.

3.5.1. MDP Formulation

The route selection process is a sequential decision-making problem in which the state evolves over time, and it is formulated as a Markov Decision Process (MDP). An MDP consists of a state space S, an action space A, a transition probability function , a reward function , and a discount factor γ. At each time step t, the reinforcement learning agent observes the state st and selects an action at, while the environment returns a new state st+1 and a reward rt. The objective of learning is to find the optimal policy π*(a|s) that maximizes the cumulative discounted return

The state st defined in this study integrates the vessel’s navigational status and the surrounding marine environmental conditions. It consists of the vessel’s geographic position (latitude and longitude), remaining distance to the destination, remaining time to the RTA, the east–west and north–south components of the wind velocity, as well as the wave height and wave period obtained from the wave field data. This comprehensive state representation captures the key factors that influence operational decision-making during navigation and provides the information necessary to simultaneously address fuel consumption, schedule adherence, and navigational safety. Accordingly, the state is expressed as

where and denote the vessel’s latitude and longitude at time t; vt is the vessel’s speed; Δdt is the remaining distance to the destination; ΔtRTA is the remaining time until the Required Time of Arrival; and represent the east–west and north–south wind velocity components; and denote the wave height and wave period extracted from the marine wave field conditions.

3.5.2. State and Action Space Design

The state space is constructed by integrating the vessel’s navigational status with external marine environmental conditions and is designed to include the key variables required for policy learning during the route-selection process. The state at time t incorporates the vessel’s geographical position (latitude and longitude), remaining distance to the destination, remaining time to the RTA, as well as the east–west and north–south wind velocity components, wave height, and wave period. This composition enables the model to capture the spatiotemporal variability of the marine environment and to provide the necessary information for addressing fuel consumption, schedule adherence, and navigational safety.

The action space consists of discrete choices of course direction and speed level. Course changes are selected from eight possible directions, while speed is chosen from predefined speed levels. Specifically, the agent selects one of eight headings and one of five speed levels knots, resulting in discrete course–speed actions. For implementation, each heading–speed pair is encoded into a single discrete action index. Each action determines the vessel’s subsequent position and navigational state, and all state transitions are evaluated within a 0.25°-resolution grid environment constructed from GEBCO bathymetry, GFS wind fields, and WW3 wave data. To reduce computational cost, the GEBCO bathymetry field was downsampled using a stride of 10 in both latitude and longitude directions, and the resulting grid was used to construct the navigation environment. Entering shallow-water areas or regions with high wave intensity incurs safety-related penalties in the reward function, guiding the policy to naturally learn risk-averse navigation behavior.

3.5.3. Reward Function

The reward function is designed to simultaneously reflect three operational objectives: reducing fuel consumption, satisfying schedule constraints based on the RTA, and maintaining navigational safety under varying marine conditions. At time t, the reward rt consists of a fuel-cost term Ft, a time-penalty term Tt, and a safety penalty term St. The overall structure is expressed as

Fuel-Cost Term

The fuel-cost term is computed using the output of the Transformer-based fuel consumption prediction model, expressed as

This term links the fuel consumption under the current marine and navigational conditions directly to the reward, encouraging the agent to learn fuel-efficient routing behavior.

Time Penalty Term

The time-penalty term Tt quantifies the deviation from the RTA. It imposes penalties for both early and late arrivals and is defined as

This formulation promotes adherence to schedule constraints and naturally incorporates JIT arrival behavior.

Safety Penalty Term

The safety-penalty term St reflects the risk of entering hazardous marine regions, such as shallow waters or areas with high wave height. In this study, the safety term is formulated in a simplified form as

where dsea,t denotes the bathymetric depth, dthr is the safety threshold, and is the wave height at time t. The coefficients λ1 and λ2 are weighting parameters that control the relative importance of shallow-water avoidance and wave-related risk, respectively.

This reward structure integrates the multi-objective nature of ship operation—including fuel efficiency, schedule compliance, and safety—within a unified reinforcement learning framework.

To clarify how the reward function aligns with the operational objectives of this study, each term corresponds directly to one of the three core goals of voyage optimization:

- Fuel efficiency: the fuel-cost term Ft encourages the agent to minimize predicted fuel consumption under the current environmental and navigational conditions.

- Schedule adherence (RTA/JIT compliance): the time-penalty term drives the policy to reduce early or late arrival deviations, supporting just-in-time operation.

- Navigational safety: the safety-penalty term St penalizes entry into shallow waters and high-wave regions, guiding the agent toward risk-averse routing behavior.

This explicit mapping reinforces that the reward function is designed to jointly optimize energy efficiency, on-time arrival, and safe navigation.

Weight Setting

The reward weights , and safety coefficients λ1, λ2 were fixed after pilot tuning to balance the magnitudes of the fuel, time, and safety terms and to ensure stable convergence. Specifically, we set , and . These values were selected so that (i) the fuel-cost term remains the dominant objective during most of the voyage, (ii) the time/RTA-related penalty activates sufficiently to correct early/late-arrival tendencies without overwhelming the fuel objective, and (iii) safety penalties impose comparable deterrence for bathymetry- and wave-related constraint violations (e.g., excessive significant wave height), thereby discouraging unsafe passages while preserving learning stability. The same weight set was applied to all case studies to maintain a controlled AIS-referenced comparison and avoid case-specific overfitting of the reward scale.

3.5.4. Deep Q-Network Structure

The proposed DQN model adopts a fully connected neural-network architecture designed to process the nine-dimensional state vector that integrates navigational variables and marine environmental conditions. The state inputs are normalized and passed through a series of dense layers that learn nonlinear relationships associated with fuel consumption, environmental resistance, and schedule feasibility. The output layer produces Q-values for all discrete course–speed actions in the action space.

Standard DQN components—including experience replay, a target network, and an ε-greedy exploration policy—were employed to stabilize training under highly correlated marine conditions. The network parameters were optimized by minimizing the mean-squared Bellman error, enabling the agent to learn long-term navigation strategies that jointly consider fuel efficiency, safety, and RTA compliance.

While many improved deep reinforcement learning algorithms—such as Double DQN and dueling DQN, prioritized experience replay, Rainbow-style extensions, and actor–critic methods like PPO and SAC—have been shown to further enhance stability and sample efficiency in various control domains, this study adopts a standard DQN formulation with a discrete heading–speed action space. The routing decision is naturally expressed as a finite set of course–speed levels, for which value-based DQN has been widely validated and is sufficient to learn effective policies. Moreover, the primary methodological contribution of this work does not lie in proposing a new RL algorithm, but in designing a voyage-planning environment that (i) integrates machine learning-based berth dwell-time prediction as a just-in-time arrival time window, (ii) embeds a transformer-based fuel consumption prediction model as a data-driven fuel-cost term, and (iii) incorporates multi-source met-ocean and bathymetric information into a multi-objective reward structure. In this sense, the proposed framework is complementary to existing improved RL algorithms and could, in future work, be combined with Double/Dueling DQN or actor–critic methods to further improve learning performance.

For implementation, the DQN agent employs a fully connected multilayer perceptron with four hidden layers of 256, 128, 64, and 32 units, respectively, each followed by a ReLU activation function. The output layer has 40 neurons corresponding to the discrete course–speed actions in the action space. Network parameters are optimized using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 3 × 10−4, and the Huber loss is used as the temporal-difference loss. The discount factor is set to γ = 0.99, and exploration follows an ε-greedy policy with an initial value ε0 = 0.7, which decays by a factor of 0.995 down to a minimum value εmin = 0.25.

The agent is trained with a replay buffer of 20,000 transitions with prioritized sampling, a mini-batch size of 32, and a Double DQN scheme with a target network that is softly updated with a rate τ = 0.005 every 20 training steps. Rewards are clipped with a lower bound of −80 to stabilize learning under adverse environmental conditions. Training is carried out for 500 episodes with a maximum of 500 decision steps per episode, and all experiments use a fixed random seed of 42 to support reproducibility.

In addition, the use of a finite, discrete heading–speed action set and a compact fully connected network keeps the per-step evaluation cost modest. Generating a complete route requires iterating this forward pass over a fixed number of decision steps, so the overall computational complexity grows approximately linearly with route length and is compatible with near-real-time route re-planning when updated met-ocean forecasts or port information become available. These hyperparameters were determined through preliminary pilot tuning and fixed thereafter.

3.6. Post-Processing

3.6.1. Speed Adjustment for Just-in-Time Arrival

Although the route generated by the DQN ensures fuel efficiency and navigational safety, the cumulative effect of discrete speed selections across multiple segments may lead to discrepancies between the final estimated time of arrival (ETA) and the target RTA. To address this issue, a post-processing step is applied to adjust the speed profile along the optimized route while preserving the geometric structure of the path. This post-processing module corrects segment-wise speeds to ensure JIT arrival without altering the optimized trajectory.

Computation of ETA Deviation

Given the distance of each route segment di and the corresponding speed level vt, the total sailing time T is computed as

where 1.852 converts knots to km/h.

The deviation between the estimated arrival time and the target arrival time is defined as

The sign of Δt determines the required correction:

- Δt > 0: the vessel is predicted to arrive late → increase speed;

- Δt < 0: the vessel is predicted to arrive early → decrease speed.

Selection of Speed-Adjustment Segments

For each segment, the change in travel time resulting from adjusting the speed index up or down by one level is computed as

This term quantifies the time sensitivity of each segment with respect to a marginal speed adjustment, and segments exhibiting larger values of |Δti| provide a greater corrective effect in reducing the global ETA deviation. Accordingly, the post-processing procedure adjusts speed levels iteratively, prioritizing segments with the most significant time-sensitivity contributions. The adjustment continues as long as the resulting ETA deviation satisfies |Δt| ≤ 20 min, the modified speed levels remain within the permissible bounds, and the incremental improvement achieved in each iteration exceeds a predefined termination threshold.

Fuel Re-Evaluation After Speed Adjustment

After adjusting the speed indices, the corrected sequence is converted back into environment actions and evaluated by the fuel consumption prediction model fϕ(·).

Fuel usage for each segment is computed as

and the total fuel consumption is

The updated ETA is then recalculated as

3.6.2. Path Simplification of Grid-Based Routes (Douglas–Peucker)

The grid-based DQN route may exhibit excessive zigzagging due to discrete heading changes between adjacent cells. To improve operational practicability, the optimized waypoint sequence is simplified using the Douglas–Peucker (DP) algorithm as a post-processing step, following the approach of Shin and Yang [23]. Specifically, given the route polyline , DP iteratively removes intermediate waypoints whose perpendicular deviation from the chord (ri,rj) is below a tolerance , producing a reduced set that preserves the overall geometry while reducing unnecessary course alterations. After simplification, each simplified segment is checked against the same land/shallow-water constraints used in the environment; if any infeasible segment is created, is reduced, or the removed waypoints are reinserted until feasibility is restored.

4. Results

4.1. Dwell-Time Prediction Model Results

In this study, a dwell-time prediction model was developed by integrating port operational data with meteorological and oceanographic variables. Operational records from PNIT between 2021 and 2023 were utilized, incorporating multiple inputs such as handling volume, container throughput, wind speed, air temperature, humidity, air pressure, and water temperature. To maintain consistency in model training, only data falling within the typical container-vessel dwell-time range (24–48 h) and within the operational upper bound of 72 h were selected. The dwell-time prediction model is constructed using a Gradient Boosting Regressor, chosen for its ability to capture nonlinear patterns and complex feature interactions inherent in port datasets. The dataset is divided into training (80%) and testing (20%) subsets, and model performance is evaluated using root mean square errors (RMSE) and the coefficient of determination (R2).

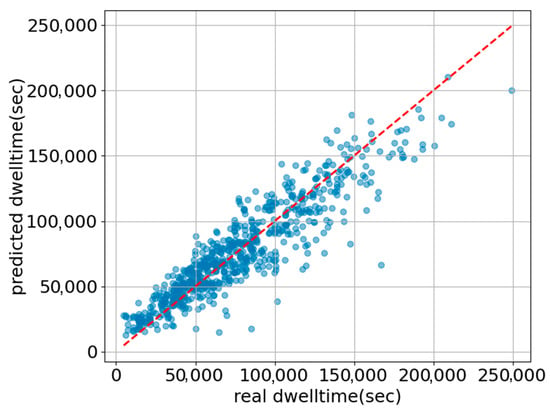

The model achieved an R2 of 0.836 and an RMSE of approximately 17,028 s, indicating that the prediction accuracy is sufficient for integration into the RTA-constrained route optimization module. The predictive performance of the model is visually presented through Figure 4 (predicted vs. actual dwell-time scatter plot). These visual results illustrate the relationships among input variables and the distribution characteristics of the predictions. The model effectively captures operational and environmental variability, providing reliable dwell-time estimates that serve as essential inputs for RTA-constrained voyage planning and route optimization.

Figure 4.

Scatter plot of actual versus predicted dwell time from the Gradient Boosting-based prediction model. Blue dots indicate individual samples, and the red dashed line represents the 1:1 line (y = x).

4.2. Fuel Consumption Prediction Model Results

In this study, fuel consumption was predicted using a transformer Encoder architecture trained on 24,000 TEU container vessel voyage measurements combined with meteorological and oceanographic variables. The input sequences include vessel speed, engine-related measurements, wind, and wave conditions. Positional Encoding and Multi-Head Attention were incorporated to accurately capture temporal interactions across the voyage, enabling the model to learn nonlinear dependency structures inherent in marine operations.

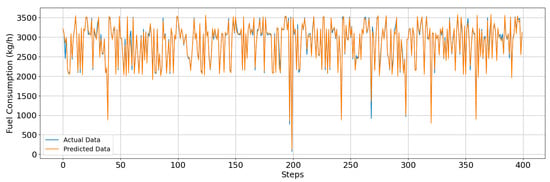

For performance evaluation, LSTM and LightGBM models were trained on the same dataset for comparison. A quantitative summary of the three models is presented in Table 8. The Transformer encoder demonstrates its advantage by effectively capturing long-range dependencies in the time series, resulting in a more stable reduction in prediction error across the full voyage interval. A time-series comparison between actual and predicted fuel consumption is presented in Figure 5, illustrating the coordination between observed and estimated patterns.

Table 8.

Performance metrics of fuel consumption prediction models.

Figure 5.

Time-series comparison of fuel consumption in the validation interval (actual vs. predicted).

Furthermore, the Transformer-based model improves prediction accuracy by incorporating the complex interactions between vessel speed variations, environmental fluctuations, and operational factors. This capability makes the model particularly suitable for quantifying fuel-related costs in route-optimization tasks, where accurate forecasts are essential for DQN-based policy evaluation and decision-making.

4.3. Route Optimization Model Results

4.3.1. Experimental Setup

All experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an Intel Core i7-10700F CPU, 128 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 Ti GPU. The software environment was Python 3.9.2 with TensorFlow 2.8.4 and Keras 2.8.0. To further support practical real-time feasibility, we additionally report an order-of-magnitude wall-clock runtime example. On the above workstation, an end-to-end inference run to generate a multi-day (e.g., ~10-day) voyage plan—including met-ocean preprocessing (loading/interpolation) and route rollout—can be completed within minutes (on the order of ~5 min), which is adequate for operational use and periodic re-planning. To enhance reproducibility of the learning process, we fixed the random seed (seed = 42) for Python, NumPy, and TensorFlow, and used the same seed for the RL environment initialization. During evaluation, we used a deterministic (greedy) policy by setting and applied an identical evaluation protocol across all methods.

Bathymetry was obtained from the GEBCO_2019 Grid (published April 2019), which has a native spatial resolution of 15 arc-seconds (0.0041667°). To reduce computational cost, the GEBCO bathymetry field was downsampled using a stride of 10 in both latitude and longitude directions when constructing the bathymetry field for the environment. Wind fields were obtained from NOAA GFS 10-m winds with a native resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°. Wave fields were obtained from WaveWatch III (WW3) with a native resolution of 0.5° × 0.5°. All environmental variables were spatially interpolated to the navigation grid used by the RL environment for state construction and route simulation.

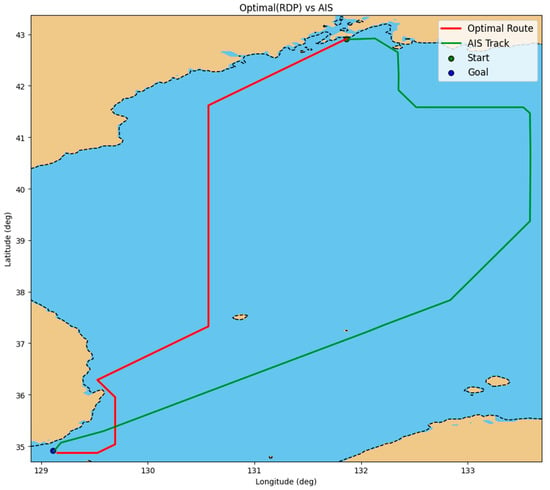

4.3.2. Case 1: Voyage Route from Gwangyang Port to Busan Port

Experimental Setup

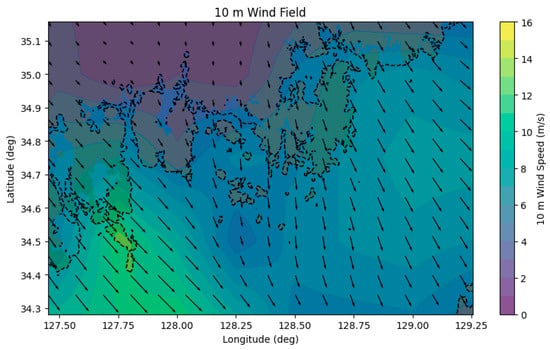

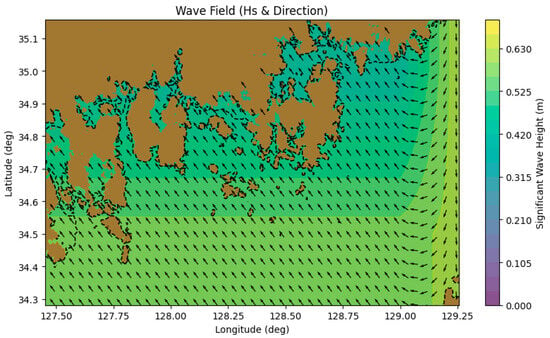

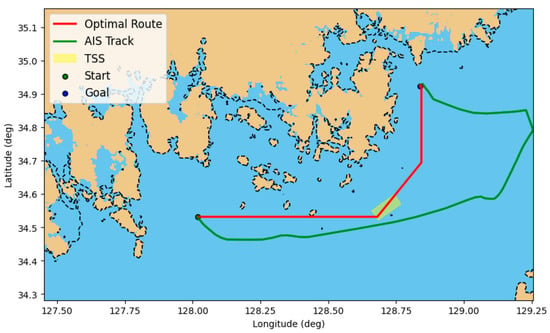

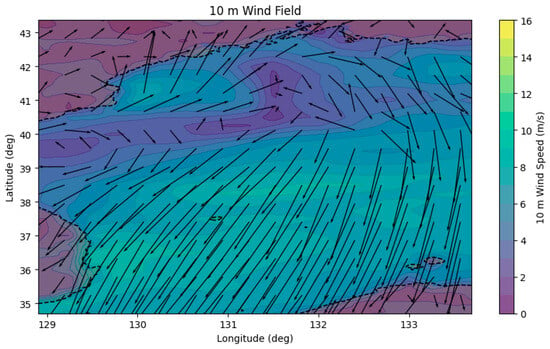

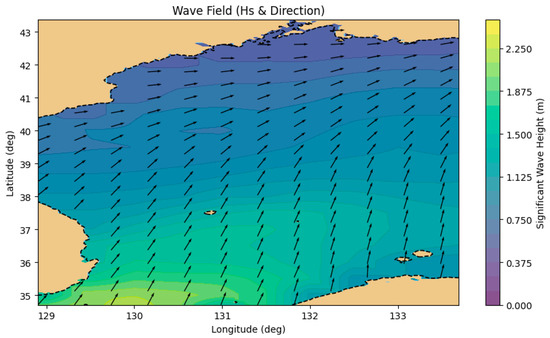

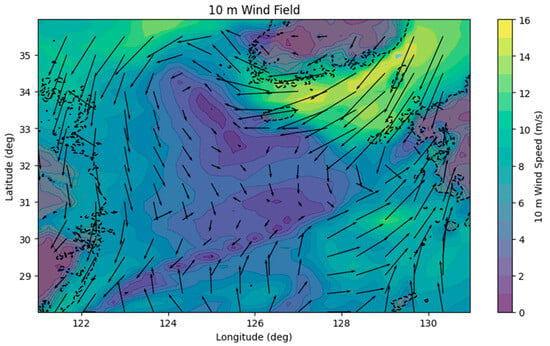

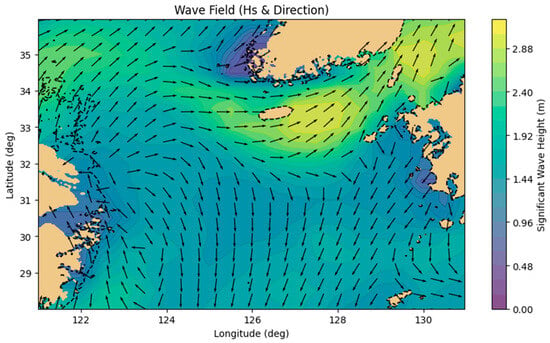

This case study examines the voyage from Gwangyang Port to Busan Port on 8 December 2023, using real AIS trajectory data. The proposed DQN-based route optimization model is designed to generate a path that minimizes fuel consumption while satisfying the RTA. Environmental conditions along the route—including GEBCO bathymetry, GFS 10-m wind fields, and WW3 wave fields—were integrated into the state representation. All environmental variables were spatially interpolated from 0.25° resolution grids and applied consistently across the navigation domain. To illustrate the environmental conditions encountered along the voyage, spatial distributions of wind–waves for the study period are presented in Figure 6 and Figure 7. Each arrow shows the 10 m wind direction from the (u10, v10) components, with length proportional to wind speed, while the color shading represents the wind-speed magnitude.

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of 10 m wind speed and direction in the waters near Gwangyang Port and Busan Port.

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution of wave height and direction in the waters near Gwangyang Port and Busan Port.

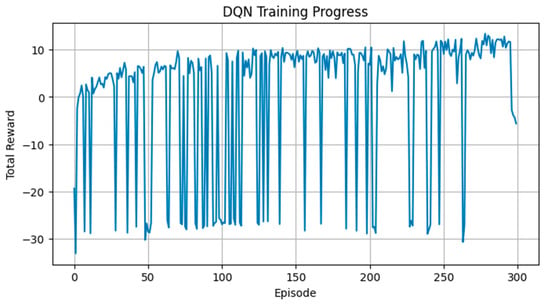

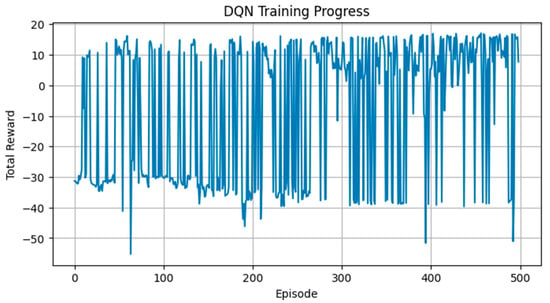

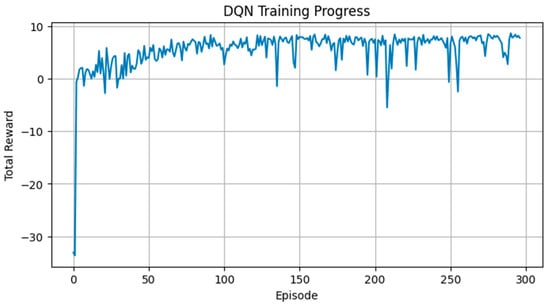

Training Performance and Optimized Route

At each step, the model receives a state vector composed of the vessel’s position, remaining distance, remaining time, speed level, and environmental conditions such as wind and waves. The DQN evaluates the Q-value of each action to choose the optimal heading and speed. The learning progression for Case 1 is assessed through episode-wise reward convergence, presented in Figure 8, confirming that the DQN policy stably converges toward strategies that maintain time feasibility while enhancing fuel efficiency.

Figure 8.

Case 1: Episode-wise variation of total rewards during the training process of the DQN-based optimal route generation model for the Gwangyang–Busan route.

The optimized route was validated by comparing it with the actual AIS track, which serves as the benchmark route in this case study, as shown in Figure 9. The optimized trajectory tends to avoid shallow regions and coastal obstacles while selecting segments with reduced wind resistance—demonstrating that the environment-aware state representation significantly influences policy decisions. In this case, an additional constraint related to the local Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS) was incorporated, as the study area contains a designated TSS corridor. This TSS constraint required the agent to avoid prohibited crossing angles and to maintain appropriate coordination when passing near the separation lanes. The optimized route successfully satisfies these case-specific TSS requirements, indicating that the agent is capable of integrating regulatory constraints when they are present in the operational domain.

Figure 9.

Case 1: Comparison between the DQN-based optimal route (red) and the actual AIS trajectory (green) for the Gwangyang–Busan voyage, with TSS compliance and the start and goal positions indicated.

Fuel and Emissions Reduction Results

The initially computed ETA of the optimized route was 00:26 on 10 December 2023, which corresponds to an early arrival of approximately 1.92 h relative to the target RTA of 02:21. After coordination, the final ETA matched the RTA with a remaining deviation of only –0.001 h (about 3.6 s), effectively achieving precise just-in-time arrival.

The optimized trajectory resulted in approximately 13.37 tons of fuel consumption and 41.65 tons of CO2 emissions, whereas the AIS-based historical route required 43.09 tons of fuel and emitted 134.26 tons of CO2. This represents a substantial reduction of about 68.97% in both fuel usage and emissions, achieved not only through a shorter sailing distance but also through environmentally favorable adjustments in heading and speed selection. In addition, the sailed distance decreased from 176.86 km (AIS) to 110.634 km (optimized), confirming that the proposed policy produced a markedly more direct route in this case.

4.3.3. Case 2: Voyage Route from Vladivostok Port to Busan Port

Experimental Setup

This case study investigates the voyage from Vladivostok Port to Busan Port, departing at 00:37 on 30 April 2024 and arriving at 23:23 on 1 May 2024, using real AIS trajectory data. The proposed DQN-based route optimization model aims to generate a fuel-efficient route while satisfying the RTA. As in Case 1, multiple environmental variables—GEBCO bathymetry, GFS 10-m wind fields, and WW3 wave fields—were incorporated into the state representation of the model. All environmental datasets were spatially interpolated from 0.25° resolution grids and consistently applied across the navigation domain. Environmental conditions encountered during the experiment period are illustrated in Figure 10 and Figure 11.

Figure 10.

Spatial distribution of 10-m wind speed and direction in the waters near Vladivostok Port and Busan Port.

Figure 11.

Spatial distribution of wave height and direction in the waters near Vladivostok Port and Busan Port.

Training Performance and Optimized Route

At each decision step, the model receives a state vector including the ship’s position, remaining distance, remaining time, speed level, and environmental conditions such as wind and waves. The DQN estimates Q-values for all feasible actions and selects the optimal heading and speed. The training progression for Case 2 is presented in Figure 12, showing stable convergence of episode-wise rewards toward policies that satisfy time constraints while improving fuel efficiency.

Figure 12.

Case 2: Episode-wise variation of total rewards during the training process of the DQN-based optimal route generation model for the Vladivostok–Busan route.

After route generation, the raw grid-based waypoint sequence is post-processed for operational applicability. Specifically, the route geometry is simplified using the Douglas–Peucker algorithm to reduce excessive zigzagging, and the segment-wise speed profile is subsequently coordinated to meet the target RTA.

The optimized path was then validated against the actual AIS trajectory, used as a benchmark route in this case study, as shown in Figure 13. The DQN-based route avoids shallow-water areas and adverse environmental regions, selecting headings and speed profiles that reduce resistance from wind. Particularly in the coastal waters south of Vladivostok and the northern entrance of the Korea Strait, the optimal policy dynamically adjusts speed to mitigate unfavorable conditions, demonstrating the effectiveness of the environment-aware state formulation.

Figure 13.

Case 2: Comparison between the DQN-based optimal route after post-processing (red) and the actual AIS trajectory (green) for the Vladivostok–Busan voyage, with the start and goal positions indicated.

Fuel and Emissions Reduction Results

For the Vladivostok–Busan voyage, the initial ETA of the optimized route was computed as 11:29 (UTC) on 2 May 2024, which corresponds to an early arrival of approximately 2.49 h relative to the target RTA of 13:58 on the same day. After applying the coordination step, the final ETA satisfied the JIT-arrival tolerance, reducing the remaining ETA–RTA deviation to approximately 5 min.

The optimized route also yielded substantial improvements in energy efficiency. Fuel consumption for the optimized trajectory was approximately 97.43 tons, compared with 131.32 tons for the AIS-based route. CO2 emissions were similarly reduced, from 408.92 tons (AIS) to 303.40 tons (optimized route). These figures represent a reduction of about 25.81% in both fuel usage and emissions, achieved through improved heading selection and speed profiles that leveraged favorable wind and wave conditions while avoiding high-resistance areas. In addition, the sailed distance decreased from 1158.76 km (AIS) to 969.71 km (optimized), further indicating that the proposed policy generated a more direct route for this case.

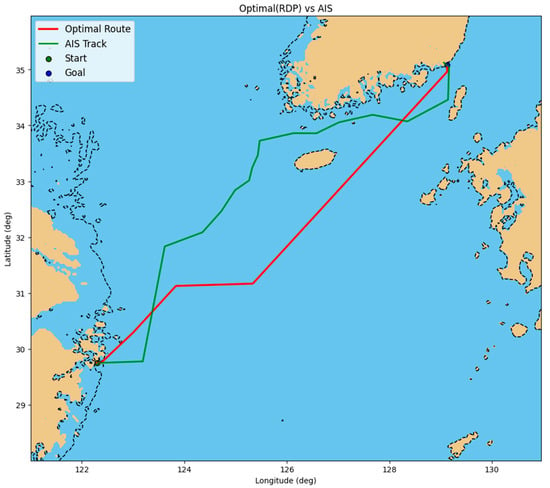

4.3.4. Case 3: Voyage Route from Ningbo Port to Busan Port

Experimental Setup

This case study analyzes the voyage from Ningbo Port to Busan Port between 04:12 on 6 May 2023 and 23:02 on 7 May 2023, using real AIS trajectory data. The proposed DQN-based route optimization model is designed to generate a fuel-efficient route while satisfying the RTA. Environmental variables across the entire navigation domain—including GEBCO bathymetry, GFS 10 m wind fields, and WW3 wave fields—were incorporated into the state representation. All environmental datasets were spatially interpolated from 0.25° grids to construct time-varying wind and wave fields for the Korea Strait and East China Sea, as illustrated in Figure 14 and Figure 15.

Figure 14.

Spatial distribution of 10 m wind speed and direction in the waters near Ningbo Port and Busan Port.

Figure 15.

Spatial distribution of wave height and direction in the waters near Ningbo Port and Busan Port.

Training Performance and Optimized Route

At each decision step, the model receives a state vector containing the vessel’s latitude–longitude position, remaining distance, remaining time, wind speed, wave height, and bathymetry. DQN computes Q-values for all feasible actions and selects the optimal heading and speed. As shown in Figure 16, the episode-wise total reward increased steadily throughout training, indicating that the model successfully converged toward policies that preserve time feasibility while enhancing fuel efficiency.

Figure 16.

Case 3: Episode-wise variation of total rewards during the training process of the DQN-based optimal route generation model for the Ningbo–Busan route.

After route generation, the raw grid-based waypoint sequence was post-processed to improve operational applicability. Specifically, we applied Douglas–Peucker path simplification to reduce excessive zigzagging and then coordinate the speed profile for JIT arrival when required.

The optimized route was then compared with the actual AIS track, which is used as an operational benchmark route in this case study (Figure 17). While the AIS trajectory follows conventional practices—passing through the Korea Strait and adjusting heading to avoid high waves—the optimized DQN trajectory avoids hydrodynamically unfavorable areas and minimizes unnecessary detours. This demonstrates that the environmentally aware state representation strongly influences policy decisions and enables more energy-efficient routing.

Figure 17.

Case 3: Comparison between the DQN-based optimal route after post-processing (red) and the actual AIS trajectory (green) for the Ningbo–Busan voyage, with the start and goal positions indicated.

ETA-RTA Coordination Process

The initial ETA of the optimized route was 19:25 on 7 May 2023, approximately 3.62 h earlier than the target RTA of 23:02. After coordination, the final ETA was adjusted to 23:23, resulting in an ETA–RTA deviation of about 20.4 min, which falls within operationally acceptable limits for near-just-in-time arrival.

In terms of energy efficiency, the AIS trajectory consumed 89.05 tons of fuel and emitted 277.29 tons of CO2, whereas the optimized route yielded 77.69 tons of fuel consumption and 241.91 tons of CO2 emissions. These values correspond to reductions of 11.36 tons of fuel and 36.62 tons of CO2, or approximately 12.76% for both metrics. In addition, the sailed distance decreased from 1048.68 km (AIS) to 917.46 km (optimized), confirming that the learned policy also produced a shorter route in this case. These improvements reflect not only the advantages of a shorter and more direct route but also the benefits of environmentally favorable heading and speed selections that mitigate resistance from wind and wave conditions.

4.4. Comparative Analysis with Existing Studies

This study benchmarks the proposed RTA-constrained DQN routing framework against representative DRL studies on ship routing and navigation automation. Moradi et al. showed larger fuel reductions with continuous-action methods under dynamic weather (e.g., 6.64% for DDPG vs. 1.07% for DQN in a no-time-limit scenario) [23]. In a related vein, Lee and Kim reported a 1.77% reduction in navigation distance compared with an actual passage plan in coastal port-to-port planning [24]. Likewise, Latinopoulos et al. reported that DDPG achieved up to ~12% fuel savings versus a distance-based baseline and about 4% lower fuel consumption than DDQN under weather uncertainty [25].

In contrast, the key distinction of the present study is that route optimality is evaluated under port-driven schedule constraints: RTA is derived from a machine-learning dwell-time predictor, and fuel costs are computed using a Transformer-based model, enabling joint optimization of energy efficiency, navigational safety, and RTA/JIT compliance within a unified reward structure.

Overall, across the three AIS-referenced case studies, the proposed approach achieved an average fuel and CO2 reduction of approximately 35.85% (12.76–68.97%). After coordination/post-processing, the final ETA–RTA deviations were about 20.4 min, 5 min, and near-zero (average ~8–9 min). Compared with the AIS trajectories, the proposed method also achieved an average distance reduction of 22.09% across the three cases; however, distance is reported as an auxiliary metric rather than the primary optimization objective. The consistent trends across three AIS-referenced routes and periods provide an indirect robustness check against scenario variability. Table 9 provides a comparative summary of these representative studies and the proposed framework.

Table 9.

Comparative summary of representative DRL-based ship routing and navigation studies and the proposed RTA-constrained framework.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that integrating port-side uncertainty and high-accuracy fuel prediction significantly enhances data-driven voyage optimization. The dwell-time prediction model provided reliable RTA estimates, and the Transformer-based fuel model produced high-resolution fuel consumption predictions that enabled realistic reward computation for route optimization. The DQN-based routing model successfully utilized these components to generate safe, fuel-efficient, and time-aligned routes under dynamic ocean conditions. Additionally, Guo et al. [22] presented an optimized DQN for coastal path planning and compared it with classical planners using geometric metrics such as path length, computation time, and the number of corners.

Across three real-world case studies, the optimized routes achieved substantial reductions in fuel consumption and CO2 emissions, with performance gains ranging from 25.81% to 68.97% compared with AIS-based trajectories. The optimized paths consistently avoided shallow-water risks and unfavorable wind–wave regions, while reducing ETA–RTA deviations to values very close to zero, thereby achieving near-perfect JIT performance.

The proposed framework provides a unified and scalable methodology that links port operations, environmental forecasting, and reinforcement learning-based route planning. Despite its strong performance, several limitations remain. The framework was evaluated using data from a single vessel type, and further validation across diverse ship classes and ocean regimes is required. Additionally, coupling the fuel-prediction and routing models into a fully end-to-end structure may further reduce cumulative errors. Future work may also incorporate load-dependent SFOC models and probabilistic environmental forecasts to enhance realism and robustness. Moreover, this study did not conduct a systematic sensitivity analysis of key algorithm inputs (e.g., reward weights and DQN hyperparameters) or multi-seed statistical reporting; future work will quantify sensitivity and robustness through controlled parameter sweeps and repeated runs. Finally, the present study did not perform a detailed empirical profiling of inference time on specific onboard or edge-computing hardware. A more systematic analysis and optimization of computational performance will be pursued in future work to further substantiate the real-time feasibility of the proposed framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.P. and S.K. (Suhwan Kim); Methodology, Y.P. and J.E.; Validation, Y.P.; Formal analysis, Y.P.; Investigation, Y.P.; Resources, S.K. (Sewon Kim); Data curation, Y.P.; Writing—original draft, Y.P.; Writing—review and editing, Y.P. and S.K. (Sewon Kim); Visualization, Y.P.; Supervision, S.K. (Sewon Kim); Project administration, S.K. (Sewon Kim); Funding acquisition, S.K. (Sewon Kim) All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has received partial support from the Korea Institute of Marine Science & Technology Promotion (KIMST), funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (RS-2023-00256127) (50%). This research was also supported by the “Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE)” through the Seoul RISE Center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Seoul Metropolitan Government (2025-RISE-01-019-04) (20%). Further support was provided by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT), Republic of Korea, through the ICT Challenge and Advanced Network of HRD (ICAN) program (IITP-2024-RS-2022-00156345), under the supervision of the Institute for Information and Communications Technology, Planning and Evaluation (IITP) (20%). Additionally, it has been funded by the Industrial Strategic Technology Development Program—Development of a Remote-Controlled Marine Firefighting System Using Autonomous Ship Technology (KEIT-20025014) for the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea) (10%).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). Revised IMO GHG Strategy 2023; IMO: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/ourwork/environment/pages/2023-imo-strategy-on-reduction-of-ghg-emissions-from-ships.aspx (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). Aligning the IMO’s Greenhouse Gas Fuel Standard with Its GHG Strategy and the Paris Agreement; ICCT: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://theicct.org/aligning-the-imos-greenhouse-gas-fuel-standard-with-its-ghg-strategy-and-the-paris-agreement-jan24/ (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Market.us. Autonomous Ships Market Report; Market.us: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://market.us/report/autonomous-ships-market/ (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). Lowering Containership Emissions Through Just-in-Time Arrivals; IMO: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/mediacentre/pages/whatsnew-1718.aspx (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- IMO–GreenVoyage2050; Low Carbon GIA. Emissions Reduction Potential in Global Container Shipping; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Uyanik, T.; Arslanoğlu, Y.; Kalenderli, O. Ship Fuel Consumption Prediction with Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 4th International Mediterranean Science and Engineering Congress (IMSEC 2019), Alanya, Antalya, Türkiye, 25–27 April 2019; pp. 757–759. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Tsoulakos, N.; Kujala, P.; Hirdaris, S. A Deep Learning Method for the Prediction of Ship Fuel Consumption in Real Operational Conditions. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 130, 107425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Song, Y.; Gao, Y.; Shen, Z.; Li, L.; Yau, A. Research on Ship Engine Fuel Consumption Prediction Algorithm Based on Adaptive Optimization Generative Network. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Kim, H.; Park, J. Fuel Consumption Prediction and Optimization Model for Pure Car/Truck Transport Ships. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital Container Shipping Association. Standards for a Just-in-Time Port Call, Version 1.0. 2020. Available online: https://dcsa.org/standards/just-in-time-port-call (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Senss, P.; Canbulat, O.; Uzun, D.; Gunbeyaz, S.; Turan, O. Just in Time Vessel Arrival System for Dry Bulk Carriers. J. Shipp. Trade 2023, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Tian, W.; Lin, B.; Meng, B.; Larsson, S.; Tian, J. Enhancing Ship Energy Efficiency through Just-In-Time Arrival: A Comprehensive Review. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 340, 122246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iris, Ç.; Pacino, D.; Ropke, S.; Larsen, A. Integrated Berth Allocation and Quay Crane Assignment Problem: Set Partitioning Models and Computational Results. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2015, 81, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, G.; Iris, Ç.; Kontovas, C.A.; Larsen, A. The multi-port berth allocation problem with speed optimization and emission considerations. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 54, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golias, M.M.; Saharidis, G.K.; Boile, M.; Theofanis, S.; Ierapetritou, M.G. The berth allocation problem: Optimizing vessel arrival time. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2009, 11, 358–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zis, T.P.V.; Psaraftis, H.N.; Ding, L. Ship Weather Routing: A Taxonomy and Survey. Ocean. Eng. 2020, 209, 107697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Zhou, P. Development of a 3D Dynamic Programming Method for Weather Routing. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2012, 6, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kytariolou, M.; Themelis, N.; Papakonstantinou, V. Ship Routing Optimisation Based on Forecasted Weather Data and Considering Safety Criteria. J. Navig. 2023, 75, 1310–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Kim, T. Generating a path-search graph based on ship-trajectory data: Route search via dynamic programming for autonomous ships. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 283, 114503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tian, W.; Mao, W. Strategies to improve the isochrone algorithm for ship voyage optimisation. Ships Offshore Struct. 2024, 19, 2137–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarini, G.; Salinas, M.L.; Carelli, L.; Petacco, N.; Orović, J. VISIR-2: Ship weather routing in Python. Geosci. Model Dev. 2024, 17, 4355–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhang, X.; Du, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Cao, Z. Path planning of coastal ships based on optimized DQN reward function. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.H.; Brutsche, M.; Wenig, M.; Wagner, U.; Koch, T. Marine route optimization using reinforcement learning approach to reduce fuel consumption and consequently minimize CO2 emissions. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 259, 111882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-T.; Kim, M.-K. Optimal path planning for a ship in coastal waters with deep Q network. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 307, 118193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latinopoulos, C.; Zavvos, E.; Kaklis, D.; Leemen, V.; Halatsis, A. Marine voyage optimization and weather routing with deep reinforcement learning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, G.-H.; Yang, H. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Integrated Vessel Path Planning with Safe Anchorage Allocation. Brodogradnja 2025, 76, 76305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hasselt, H.; Guez, A.; Silver, D. Deep Reinforcement Learning With Double Q-Learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 12–17 February 2016; Volume 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Schaul, T.; Hessel, M.; van Hasselt, H.; Lanctot, M.; de Freitas, N. Dueling Network Architectures for Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2016), New York, NY, USA, 19–24 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaul, T.; Quan, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Silver, D. Prioritized Experience Replay. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2016), San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2–4 May 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessel, M.; Modayil, J.; van Hasselt, H.; Schaul, T.; Ostrovski, G.; Dabney, W.; Horgan, D.; Piot, B.; Azar, M.G.; Silver, D. Rainbow: Combining Improvements in Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2018, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; Volume 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarnoja, T.; Zhou, A.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. Soft Actor-Critic: Off-Policy Maximum Entropy Deep Reinforcement Learning with a Stochastic Actor. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2018), Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPI Depot. Port Stay Duration. Available online: https://kpidepot.com/kpi/port-stay-duration (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Northern Corridor Transit and Transport Coordination Authority. Monthly Port Community Charter Report: February 2018; Northern Corridor Transport Observatory: Mombasa, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A Next-Generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 2623–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.