Abstract

Wave energy technology needs to be reliable, efficient, and environmentally sustainable. Therefore, life cycle assessment (LCA) is a critical tool in the design of marine renewable energy devices. However, LCA studies of floating type wave cycloidal rotors remain limited. This study builds on previous work by assessing the cradle-to-grave environmental impacts of a cycloidal rotor wave farm, incorporating updated material inventories, site-dependent energy production, and lifetime extension scenarios. The farm with the steel cyclorotor configuration exhibits a carbon intensity of 21.4 g eq/kWh and an energy intensity of 344 kJ/kWh, which makes it a competitive technology compared to other wave energy converters. Alternative materials, such as aluminium and carbon fibre, yield mass reductions but incur higher embodied emissions. Site deployment strongly influences performance, with global warming potential reduced by up to 50% in high-power-density sites, while extending the operational lifetime from 25 to 30 years further reduces the impact by 17%. Overall, the results highlight the competitive environmental performance of floating wave cycloidal rotors and emphasize the importance of material selection, site selection, and lifetime extension strategies in reducing life cycle impacts.

1. Introduction

Recent years have witnessed wave energy taking huge strides towards commercialisation. In Europe, companies such as Swedish based CorPower and Scottish based Mocean Energy are developing large-scale prototypes (>100 kW) and are driving the push towards wave energy development throughout the globe. Furthermore, the European commission has a clear directive to support wave energy development, as indicated in recent pubic reports and communications [1,2].

Other wave energy emerging technologies have also been proposed, such as wave cycloidal rotors, which operate in a submerged manner and avoid slamming loads from the ocean. Such devices are in development in America with company Atargis and have been investigated in Europe through the Horizon 2020 LiftWEC project [3,4,5,6] and, recently, with the Maxrotor project in Ireland [7,8,9].

Specifically, over the past decades, significant progress has been made in the field of wave cycloidal rotors, ranging from low-order hydrodynamic modelling [10,11], tailored to control philosophies [9,12], to more sophisticated modelling tools, such as physics-informed low-order models [13] and high-fidelity modelling [14]. Recently, the performance of the device in terms of three-dimensional layout and farm-scale design configurations has been addressed [15]. In terms of fluid–structure interactions, the role of flow separation and the type of control strategy on structural loads is now better understood [3,4], as well as material selection frameworks for rotor components [16]. Nonetheless, although progress has been made in the understanding of wave cycloidal rotors, it is crucial to investigate the carbon and energy footprint throughout the entire life cycle to ensure that these technologies are not only technically and economically viable but also an environmentally sustainable.

Within the environmental pillar, life-cycle assessment (LCA) is a widely accepted methodology for evaluating environmental impacts across multiple indicators by considering a technology’s resource requirements and performance over its entire life cycle. However, there are currently few LCA studies in the literature on wave energy converters and typically tailored to different technologies, such as, for example, surge oscillators [17,18], point absorbers [19,20], oscillating water columns [21]. Nonetheless, for wave cycloidal rotors, the test studies are more scarce. To address the research gap in carbon footprint of cycloidal wave energy converters, a LCA was carried out within EU H2020 LiftWEC project and presented at the 15th European Wave and Tidal Energy Conference in Bilbao, Spain [22].

Building on that initial work [22], the present study incorporates project developments, extends the earlier findings and emphasises the novelty of the current study through: (1) refinement of the design of the cyclorotor, (2) material considerations, (3) improved power extraction, (4) analysis of alternative life-time scenarios, and (5) discussion of environmental considerations. Furthermore, this study outlines the methodology used to implement the LCA and compute the energy and carbon flows from a theoretical large-scale development of wave cycloidal rotors, covering all life cycle stages from cradle to grave.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 describes the wave cycloidal system and the case study considered, followed by an outline of the LCA methodology and data collection approach. Section 3 presents the results, starting with the baseline scenario and the corresponding energy payback time, before examining a set of alternative design and operational scenarios. Section 4 discusses the implications of the findings, including comparisons with other marine renewable and conventional energy technologies, as well as broader environmental considerations. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper by summarising the main outcomes and outlining recommendations for future work.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Description

The EU H2020 LiftWEC project developed a floating wave cycloidal rotor that used lift forces as the main driver of rotor motion. The device is equipped with two rotating foils. An overview of the operational mechanisms employed by the device can be found in [23]. The system can be divided into five main sub-systems: rotor, stator, spar-buoy structure, mooring system, and electrical cables.

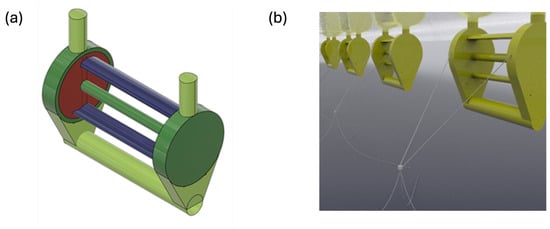

The wave cycloidal rotor is illustrated in Figure 1a. It comprises a rotor-stator-spar floater assembly. The rotor subsystem is composed mainly of two hydrofoils that terminate within bearing elements set within circular end plates. The stator comprises two nacelle structures that support the rotor section and house two direct driver generators, along with other smaller components, such as ancillary power electronics and braking mechanisms. The spar structure consists of the structural station-keeping elements. In the lower portion of the structure, the tube connecting both nacelles is used as a ballast tube, and to react to the rotor torque generated during operation. The structure is held in place by a single-point twin-line yoked mooring that transitions to a three-point catenary line mooring system anchored to the seabed using two drag anchors per line (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) Spar LiftWEC configuration: rotor-stator-spar floater assembly and (b) Spar LiftWEC array with mooring system.

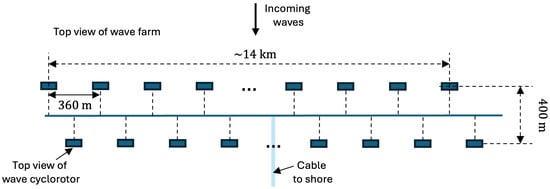

This study considers a WEC farm layout consisting of two rows of staggered devices, as proposed in [24]. A total of 80 WECs are considered. Each row consisting of 40 WECs. The electrical system consists of inter-array cables that connect devices to an offshore substation, and an export cable connecting the offshore substation to the grid. The key parameters assumed for this study are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key parameters describing the settings of the lift-based wave energy converter and case study.

In Table 1, the span of the hydrofoils is selected based on structural results of the LiftWEC project, which determined that 30 m is the span that provides optimal power performance [24]. The rated power of the device was derived considering Siegel et al. [25], with the maximum rated power of the generator being 2.5 MW for a 60 m foil span cyclorotor. Therefore, with a span of 30 m, the cyclorotor is expected to produce a maximum of 1250 kW. This maximum rated power was confirmed by the LiftWEC consortium using pitch and rotational velocity control [24], computed with a low-order numerical code [12].

The wave average power of 36 kW/m is derived from the proposed location of the wave farm at a point on the North Atlantic coast of France (coordinates 47.84° N, 4.83° W), in the Bay of Audierne near Quimper [24]. The annual energy yield per device was computed by combining the power matrix for the specific span with the scatter diagram of the deployment site. We considered an average of 3.6 GWh/year per device, following Deliverable 8.6 — LCoE of the Final Configuration [24].

A top-view schematic of the proposed wave farm layout is shown in Figure 2. The diagram shows the spacing between devices and rows, the main bus with device connections indicated by dotted lines, and the main cable to shore. Note that in Figure 2, not all devices are shown due to symmetry of the diagram.

Figure 2.

Top view schematic of proposed wave farm layout. Not all 80 devices are shown due to symmetry of the diagram.

2.2. Life Cycle Assessment

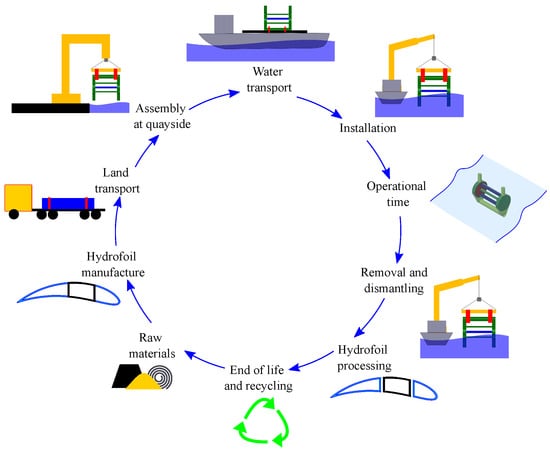

LCA is a standardized methodology for evaluating the environmental aspects and potential impacts associated with a product or system throughout its life cycle, from raw material extraction to end-of-life management. It supports decision-making by identifying environmental hotspots and enabling comparison of design alternatives. LCA is particularly valuable for benchmarking technologies from a multi-criteria perspective that considers environmental performance alongside technical and economic factors. The generic steps of the life cycle stages of a wave cycloidal rotor are visualised in Figure 3, as described in [16].

Figure 3.

Life cycle stages for a wave cycloidal rotor. Reproduced from Arredondo-Galeana et al. [16] under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Specifically, the methodology used in this work complies with the international standards ISO 14040 [26] and ISO 14044 [27], which specifies the general framework, principles, and requirements for conducting and reporting this type of assessment, comprising four main stages: (1) goal and scope definition, (2) inventory analysis, (3) life cycle impact assessment (LCIA), and (4) interpretation.

The main purpose of this analysis is to assess the environmental impacts of a potential 100 MW array deployment in France. The functional unit (FU) is defined as 1 kWh of electricity delivered to the French electricity network from the array. According to the preliminary studies carried out by [24], a 30 m span device is estimated to produce between 2160 to 2491 MWh/year, over the entire lifespan (Table 1).

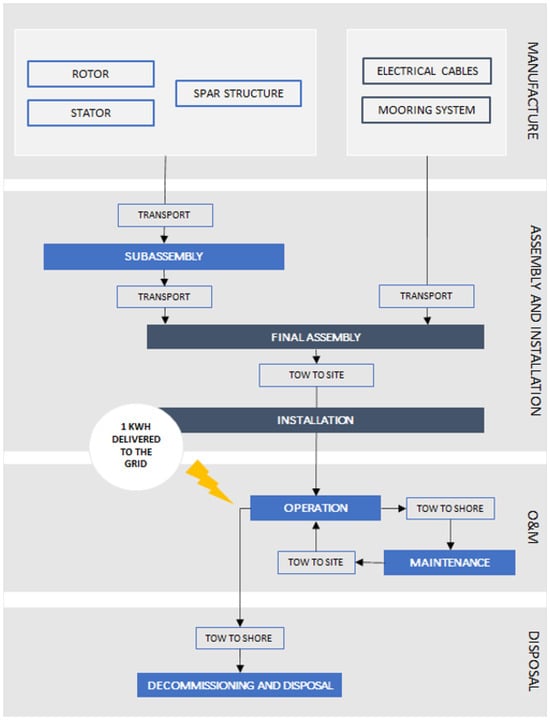

The system boundary encompasses all life cycle stages from cradle to grave, comprising the production of components, their assembly and transportation to the installation site, operation and maintenance (O&M), and finally decommissioning and waste disposal strategies. A schematic of the flow chart followed in this work to carry out the life cycle assessment is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Flowchart describing steps to carry out life cycle assessment.

Physical boundaries, such as the power substation and all parts of the onshore electricity grid are outside the scope of this analysis. Additionally, no credit is provided for recycling within the project disposal scenario. Any benefits associated with material recovery are treated using the avoided burden approach. This approach is adopted to ensure consistency with comparable studies in the literature and facilitate a fair comparison of results.

To allow comparison with other marine renewables (MRE) technologies and traditional means of electricity generation, carbon dioxide equivalent emissions per produced electricity (g CO2 eq/kWh) were defined as the main unit for the study. SimaPro 8 was the software used to model the system, with Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) data sourced from the Ecoinvent database (v3.5). The impact assessment is achieved by translating the environmental loads from the inventory results into midpoint impact categories using ReCiPe 2016 Midpoint method [28]. Although this analysis focuses on climate change, an energy input assessment was carried out using the cumulative energy demand (CED) to calculate the total direct and indirect amount of energy consumed throughout the life cycle. While Global Warming Potential (GWP) is used as the primary benchmarking indicator, selected non-climate midpoint categories and endpoint indicators are also interpreted to support a broader environmental assessment, in line with the ReCiPe 2016 framework [15,29].

2.3. Data Collection

The primary data for this study was collected from the LiftWEC project design team and relevant publications, namely [3,14,16,24,30,31]. All background or secondary data were derived from the Ecoinvent database (v.3.5). Since the Ecoinvent database does not contain all inventory information, some materials and manufacturing processes were modelled according to data sourced from literature, suppliers’ catalogues, and experts’ knowledge.

Given the expected small contribution of some electronic and electrical systems to the overall embodied carbon and considering their complexity, it was more appropriate to simplify this stage to avoid time consumption. Thus, a cut-off criterion of 1% was applied throughout the life cycle to exclude minor impacts and help set boundaries for the total system inventory [32].

2.3.1. Raw Materials and Manufacturing

The initial phase bounded by the system starts with the processing of raw materials, which is followed by the manufacturing phase where materials are moulded and shaped to produce sub-components of the device.

The rotor subsystem is composed mainly of composite material, such as fibre glass (hydrofoil), while offshore steel is the main material of other components. Steel alloy is the main material used for stator components and spar-buoy structural elements. In addition, the ballast tube is partially filled with concrete.

The selection of materials for the hydrofoils and the rest of the structures of the rotor is a complex multi-criteria decision-making process which requires the evaluation of different parameters. For the case of the hydrofoils, such parameters could include structural reliability, hydrodynamics, ease of maintainability, manufacturing costs and environmental impact, as suggested in [16]. Furthermore, the decision for material selection depends also on the technology readiness level (TRL) of the WEC. Manufacturing costs and ease of maintainability can evolve in time and the selection of materials can change over time. For example, for an initial stage of design the preferred material for the hydrofoils of a wave cycloidal rotor was found to be steel [16]. In later design stages, composite materials emerged as an attractive option due to their improved strength-to-weight ratio and corrosion resistance. However, from an environmental and economic standpoint, steel remains advantageous due to its high recycling rate, well-established recovery infrastructure, and lower end-of-life handling cost compared to composite materials, which are difficult to recycle and typically require energy-intensive disposal methods. Therefore, steel is adopted as the baseline material in this study, while alternative scenarios considering composite materials are also examined in the Results section.

The mooring lines are mainly fabricated of fibre ropes and the prefabricated anchors are made of steel. At this stage of the project, the expected station-keeping loads and consequently the specification of the anchors have not yet been defined. Thus, taking a reference WEC [33] and considering safety margins due characteristics of the floating cycloidal rotor (Figure 1a), the drag embedment anchors 5te [34] were chosen to compose this system.

The substation and all parts of the onshore electricity network and grid integration are outside the scope of this analysis. Based on [35] copper cables were assumed with 22.2 kg/m and 65.2 kg/m for 10 kV and 132 kV cables respectively. The material composition was taken as a reference from [36].

An estimate of the mass breakdown indicates that the spar structure composes the largest part of the total mass (81%), followed by the stator (13%), rotor (4%), mooring system (1%) and electrical cables (1%).

Concerning the type of material considered for the mentioned sub-systems, including the prefabricated components, the following distribution is estimated: concrete (71.6%); low-alloy steel (26.0%); fibre glass (1.1%); stainless steel (0.3%); other polymers (0.5%); lead (0.2%); copper (0.2%); other materials (0.1%).

It is assumed that steel passes through the processes of machining and welding before being painted to avoid biofouling and corrosion. The energy consumption for the heavy machining and painting processes was based on [37]. Calculations for the welding process were completed assuming the need for 4.4 kg of welded steel per meter [38]. To estimate the volume of coating required for the main structures, 0.2 mm, 0.1 mm, and 0.1 mm thickness were assumed for the primary, intermediate, and anti-fouling treatment, respectively.

2.3.2. Assembly and Installation

The assembly phase involves the road and sea transport of each subcomponent to a fabrication yard in France from the assumed manufacturing locations: steel panels and shafts (Germany), hydrofoils and anchors (UK), mooring lines (Belgium), generators and other main equipment (Finland), electrical cables (China), structural subcomponents and concrete ballast (France). After final assembly, specialized vessels are required to prepare the seabed, install moorings, tow and install the device. The processes to prepare the site installation were not considered in this analysis given their relatively small impacts on the results. The installation strategy of the devices defined in [23] served as input for this analysis, providing vessel types, fuel consumption and time spent for a certain baseline scenario of weather constraints and task duration.

The summary of the vessels considered for this stage is detailed in Table 2. By scaling Ecoinvent data for a freight ship to match the fuel consumption of each type of vessel, as suggested by [39], it is possible to achieve the correspondent payload of each operation, where 1 end corresponds to 0.0028 litres of fuel. The payload (tkm), is a metric used to express the total work of transporting 1 tonne of cargo over 1 km.

Table 2.

Summary of Vessels at Installation Tasks. In the table, AHTV refers to Anchor Handling Tug Vessel and CLV to Cable-Laying Vessel.

2.3.3. Operation and Maintenance

The floating cycloidal rotor depicted in Figure 1a enables the implementation of a return-to-base (RTB) strategy for maintenance campaigns, both preventive and corrective. This approach assumes that large repairs are carried out at the port, avoiding the use of large offshore vessels and minimizing risks, stoppages, expenditures, and emissions.

The O&M analysis conducted by [23] considered failure rates and weather conditions to estimate the total offshore hours required during the 25-year lifetime of the project by the necessary resources, which include a set of two tugs and two support divers. By the failure rate evaluation, no significant requirement for component replacement was identified. An estimate of the lubricating oil change is considered as 15 t per MW of device capacity [40]. A summary of the vessel requirements for preventive maintenance is provided in Table 3. Note that in Table 2 and Table 3, “2 divers” refers to two individuals only and does not include the dive support team.

Table 3.

Summary of Vessels at Maintenance Tasks.

2.3.4. Decommissioning and Disposal

Decommissioning and disposal are crucial aspects of the life cycle assessment as they mark the end-of-life (EoL) phase of the project and determine its management approach. The chosen strategy can significantly reduce the overall environmental impact by offsetting the effects linked to earlier stages. In this analysis, decommissioning of LiftWEC mainly includes transport from the operation site to the yard, where disposal actions will follow. According to the assessment conducted by [24], the cost of the decommissioning phase represents about 77% of the installation expenditures. To reflect uncertainties and include a conservative safety margin, the decommissioning phase in this study is modelled as 85% of the installation effort. This assumption reflects a reduction in offshore activities during decommissioning compared to installation. In particular, no seabed preparation or mooring deployment was considered at this stage, although vessel operations, lifting activities, and site clearance are still required.

The disposal scenario considers three different EoL approaches: recycling, reusing, and landfilling. Reuse retains components for further application with minimal refurbishment, whereas recycling involves material reprocessing to produce secondary raw materials. Both strategies aim to reduce waste generation and recover value from materials that would otherwise be discarded. The assumed EoL scenarios are indicated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Assumptions for End-of-Life Scenarios.

Although the recycling cut-off approach used in this study does not fully reflect the role of recycled materials beyond the system boundary, it was considered to allow a closer comparison with other studies. As a result, recycling in this study focuses on minimizing net energy and carbon flows by reducing the quantity of waste sent to landfills. In terms of the concrete’s EoL, it is assumed that the material can be reused, effectively avoiding the need for new production and providing a positive impact credit. The transportation of concrete to the final disposal site was considered to have minimal significance compared to other stages of the life cycle and, as a result, it was excluded from the analysis.

2.4. Data Quality, Reliability, and Sensitivity Analysis

Building on the data sources described above, data reliability was assessed qualitatively following standard LCA practice. Background processes sourced from the Ecoinvent database include pedigree-based data quality indicators covering reliability, completeness, and technological, temporal, and geographical representativeness. Foreground inputs derived from the LiftWEC design and supporting literature were assessed qualitatively in terms of representativeness and consistency with the studied technology and deployment context. As the LiftWEC technology is at an early development stage, real operational and failure data are not available yet, which introduces uncertainty in assumptions related to component reliability, maintenance needs, and vessel usage.

To limit arbitrariness in modelling, key assumptions were informed by reliability-oriented design activities, including structural fatigue analyses, failure mode, effects and criticality analysis (FMECA) [16], and estimates of component failure rates [23]. These analyses supported the definition of design, lifetime, maintenance strategies, inspection intervals, replacement assumptions, and associated vessel usage within the life-cycle inventory.

The main drivers of the analysis were identified as (i) material choice and mass, (ii) site selection, and (iii) operational lifetime. Data robustness was evaluated through the scenario analyses presented in Section 3, explicitly examining the influence of these parameters on the main impact indicators.

3. Results

3.1. Life Cycle Impact Assessment

The LCI compiled for this study includes approximately 1700 elementary flows representing material and energy inputs as well as emissions to air, water, and soil throughout the full life cycle of the system. Table 5 shows the total life cycle emissions of the six greenhouse gases (GHG) regulated under the Kyoto Protocol: carbon dioxide (), methane (), nitrous oxide (), hydrofluorocarbons and perfluorocarbons (HFCs and PFCs respectively) and sulphur hexafluoride ().

Table 5.

Emissions of the Kyoto Protocol GHGs.

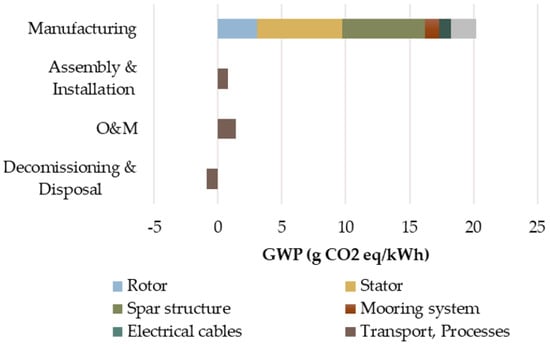

The GWP per phase is indicated in Figure 5 and reveals that assembly and installation (3%) and O&M (6%) have relatively minor influence on total emissions. In contrast, manufacturing is the dominant contributor, responsible for approximately 20.2 g CO2 eq/kWh, including transport across the fabrication site to the yard. Within this phase, the stator and spar structure are the largest contributors, each accounting for approximately 33% of the manufacturing-related emissions (6.6 g CO2 eq/kWh). This is primarily due to the high carbon and energy intensity associated with producing steel alloys and concrete, which constitute a significant proportion of the overall material mass.

Figure 5.

Global warming potential results per phase. The gray colour indicates other manufacturing-related contributions (e.g. auxiliary materials and internal transport).

Given the relevance of climate change mitigation in the development of ocean energy technologies, particular emphasis is placed on the Global Warming Potential (GWP) impact category. However, a comprehensive assessment is also provided. Table 6 summarises the results across all 18 midpoint impact categories from the ReCiPe method, together with cumulative energy demand (CED), to enable broader environmental interpretation beyond GHG emissions.

Table 6.

Results of LCIA and CED Calculation with Acronyms.

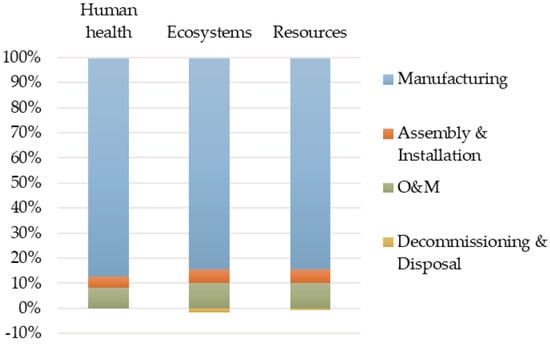

The endpoint impact results are presented in Figure 6, where midpoint impacts are aggregated into damage across the three ReCiPe areas of protection: Human Health, Ecosystem Quality, and Natural Resources. The contributions from each life cycle stage are relatively uniform for Ecosystem Quality and Natural Resources. In contrast, Human Health shows greater sensitivity to the manufacturing and disposal stages, indicating that emissions associated with material production and end-of-life processes are dominant contributors in this category.

Figure 6.

Results of ReCiPe impact assessment method applied at the endpoint level.

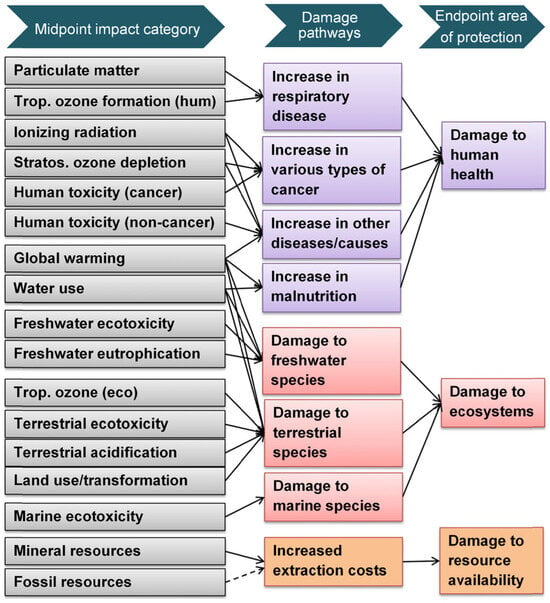

To support a more intuitive interpretation of these multiple midpoint indicators, endpoint results are presented in Figure 7, where impacts are aggregated into the three ReCiPe areas of protection: Human Health, Ecosystem Quality, and Natural Resources. The endpoint perspective confirms that manufacturing and disposal stages dominate damage to Human Health, consistent with the prominence of toxicity-related midpoint categories, while Ecosystem Quality and Natural Resources show more uniform contributions across life-cycle stages [29,41].

Figure 7.

Midpoint impact categories, damage pathways and endpoints of ReCiPe method. Reproduced from Huijbregts et al. [41], under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. No changes were made.

Table 6 and Figure 7 show that, in addition to GWP, several non-climate midpoint impact categories are relevant for understanding broader environmental trade-offs associated with the wave cycloidal rotor. In particular, eutrophication and toxicity-related indicators, including freshwater and marine eutrophication, terrestrial, freshwater and marine ecotoxicity, and human toxicity, indicate potential pressures on aquatic ecosystems and human health that are not captured by carbon metrics alone [29,41].

Freshwater eutrophication (F Eut) (1.3 × 10−3 g P eq/kWh) and marine eutrophication (M Eut) (7.6 × 10−4 g N eq/kWh) reflect emissions that may contribute to nutrient enrichment in freshwater and coastal environments, potentially promoting algal blooms and oxygen depletion [41,42]. As manufacturing represents the dominant life-cycle hotspot, these impacts are largely driven by upstream processes associated with material extraction and processing, particularly steel and concrete production, and by the energy supply chains supporting component manufacturing [43,44]. Consequently, strategies that reduce upstream burdens per unit of electricity, such as reducing material intensity, increasing annual energy production, extending device lifetime, and shortening supply chains, are expected to co-reduce eutrophication impacts alongside GWP on a per-kWh basis.

Toxicity-related midpoint results indicate terrestrial ecotoxicity (T Etox) of 365.2 g 1,4-DCB eq/kWh, freshwater ecotoxicity (F Etox) of 6.2 × 10−2 g 1,4-DCB eq/kWh, and marine ecotoxicity (M Etox) of 2.6 × 10−1 g 1,4-DCB eq/kWh. Human toxicity reaches 2.9 g 1,4-DCB eq/kWh (carcinogenic; HTcar) and 18.6 g 1,4-DCB eq/kWh (non-carcinogenic; HTcar). These impacts are primarily associated with emissions arising along industrial supply chains, including metal production, chemical processing, coating systems, and electricity generation [41,45]. From a design and life-cycle perspective, potential mitigation pathways include reducing coated steel surface area, adopting longer-lasting protection systems to limit recoating frequency, and prioritising materials with established recycling routes at end-of-life [46,47].

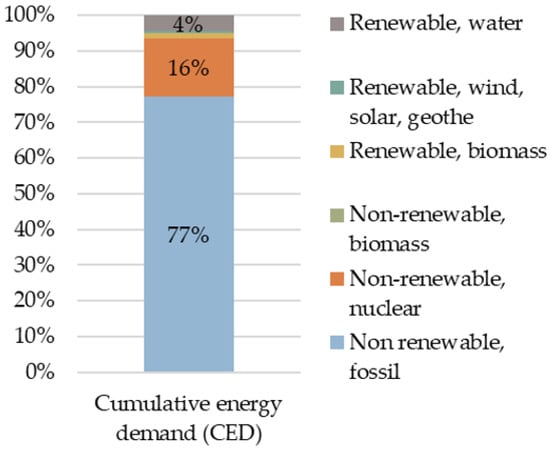

Lastly, Figure 8 indicates the breakdown of CED, which totals 344 kJ/kWh. The CED is disaggregated into five categories of primary energy carriers: fossil, nuclear, hydro, biomass, and other renewables (wind, solar, and geothermal). These contributions reflect the final energy demand associated with the location-specific electricity mixes used during the production of each component. The results highlight a strong reliance on non-renewable energy sources, with fossil fuels alone accounting for approximately 77% of the total energy demand per kWh of electricity generated.

Figure 8.

Cumulative energy demand (CED) per energy source.

3.2. Carbon and Energy Payback Time

Energy Payback Time (EPT) and Carbon Payback Time (CPT) are key performance indicators for evaluating renewable energy systems. CPT quantifies the time required for the wave cycloidal rotor to offset the total life cycle greenhouse gas emissions associated with its production, operation, and end-of-life treatment (Equation (1)). EPT, on the other hand, represents the time needed for the system to generate an amount of energy equal to the cumulative primary energy demand over its lifetime (Equation (2)).

In Equation (1), the life-cycle CO2 eq emissions are obtained by multiplying the GWP intensity reported in Section 3.1 (g CO2 eq/kWh) by the total lifetime electricity delivered. Similarly, the total life-cycle embodied energy in Equation (2) is obtained by scaling the cumulative energy demand (CED) reported in Section 3.1 (kJ/kWh) by the same lifetime electricity delivered.

The annual energy production (AEP) is estimated by accounting for percentage energy losses due to array interaction effects, specifically the reduction in performance caused by placing one row of devices in front of another [24]. Based on the losses reported in Table 1, the AEP of the proposed wave energy farm is estimated to be approximately 289 GWh per year.

The offset of electricity by the device was assumed to be the average of the French grid, which is characterised by an 85% nuclear share and a carbon intensity of 87.3 g eq /kWh (Ecoinvent database). Due to the relatively low emission factor of the French grid, the CPT was estimated as 9.8 years. This value is relatively higher than typical figures reported in the literature (around 1 to 2.5 years), largely due to the low-carbon nature of the reference grid mix. Based on the estimated CED, the corresponding EPT is approximately 2.9 years.

3.3. Alternative Scenarios

A range of three alternative scenarios was considered to investigate the sensitivity of the project to specific inputs and, consequently, to assess potential improvements in the impact of the life cycle assessment. Results presented in this section are indicative and interpretation requires careful assessment regarding the sensitivity of each parameter variation. Such uncertainties arise from some approximations made in this early stage of the design of a cycloidal wave rotor.

3.3.1. Materials

With manufacturing being the main driver of the overall impact, this section is addressed to evaluate the potential of reducing the required material quantities by replacing the steel used for the structure with different materials with lower density. It is worth mentioning that this analysis represents a rough estimate, not considering possible variations on design that may be required in terms of structural resistance or other technical aspects such as failure rates. The assumptions taken for this analysis were based on the materials assessment carried out by [16] and are detailed in Table 7. As transportation is expressed by the payload distance (tkm), it may also reflect a slight reduction in its impact due to mass reduction. All other considerations made for the baseline scenario remain unmodified.

Table 7.

Assumptions for alternative scenario (material).

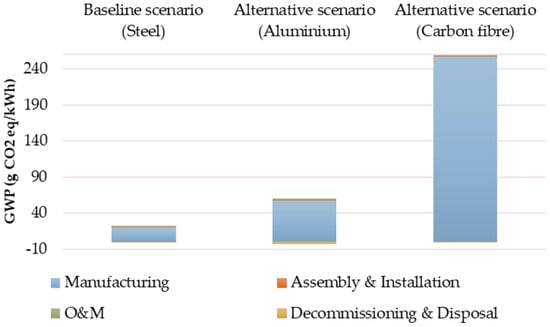

Despite the reduction in material mass, the GWP increases substantially in both alternative material scenarios when compared to the steel baseline. As represented in Figure 9, the GWP rises to 58.2 when aluminium alloy is used, representing an increase of approximately 171%. The impact is even more pronounced for carbon fibre composite, which reaches 259.7 g CO2 eq/kWh corresponding to an increase of over 1110% relative to the baseline. This sharp increase is explained by the high carbon and energy intensity of producing aluminium and carbon composite materials, which outweighs the benefits of reduced material quantities. A similar trend is observed for CED, with both alternative materials resulting in a marked percentage increase relative to the baseline. When considering composite materials, due to the nature of thermosetting resin, which is produced by an irreversible hardening process of a viscous fluid, the impact can be even greater, as separation and recycling processes are expensive and require many energy-intensive processes, being in many cases opted to be directed to landfill.

Figure 9.

GWP results for alternative scenarios (material).

3.3.2. Site Deployment

This analysis aims to evaluate how resource availability and logistic distance influence the life cycle results. The analysis was performed for two different deployment locations: in the offshore area of Lisbon (Portugal) and the coastal area of Bellmulet (Ireland). For consistency, the same assumptions were applied regarding manufacturing (material, process, and location), assembly site and O&M port logistics. The parameters that differ from the reference case are the energy production potential at each site and the transport distance between the assembly site and the deployment location.

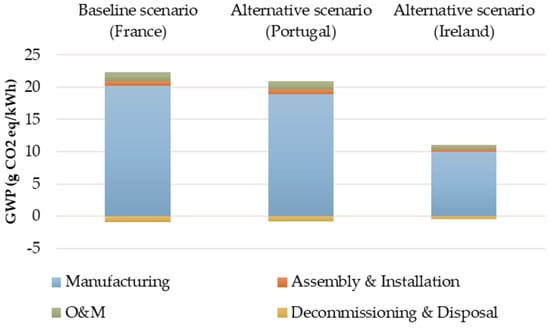

Despite the increased transport distance between the assembly yard in France and the deployment sites, which raises the logistics-related impacts, the GWP per unit of electricity generated is lower for both deployment scenarios. This is because the contribution from the manufacturing phase remains equally high across locations, while the AEP increases due to higher local wave energy resources. As indicated in Figure 10, the GWP is reduced by 6% for the Portugal site (20.1 g CO2 eq/kWh) and by 50% for the Ireland site (10.7 g CO2 eq/kWh) compared to the baseline scenario.

Figure 10.

GWP results for alternative scenarios (site deployment).

It should be emphasized that this represents an early-stage assessment, and the manufacturing phase was assumed to be identical for both locations. Potential changes in structural design, material demand, or mooring requirements due to different environmental loading conditions were not yet modelled and should be addressed in future work. Conversely, the results also suggest that environmental impacts could be further reduced through shorter supply chains and the selection of assembly and service ports closer to the deployment site.

Since the installation and O&M phases express a small share of total carbon intensity, the additional emissions caused by increased transport distance in these phases have a limited influence on overall results.

Furthermore, with manufacturing playing a substantial role in the final impact, in this case, the variation in energy production profiles is the main driver of the g /kW ratios. In other words, although the material demand remains constant, higher energy output at more energetic sites dilutes the embodied emissions per kilowatt-hour delivered to the grid.

Considering the energy production profile in these two alternative sites with increased load from fossil sources (higher GHG emissions), the CPT reduces to values more aligned with previous studies, indicating 1.4 and 0.4 years for Portugal and Ireland, respectively. These results illustrate the additional benefit of the device in avoiding emissions when situated in high wave energy sites exposed to swell waves [48].

3.3.3. Lifetime Extension

The feasibility of extending the operational lifespan of already deployed offshore wind assets as well as the new designs have been extensively studied, taking into account technical, economic, and regulatory aspects. Extending the lifetime of these assets reduces the need for new construction and associated emissions, supporting sustainability objectives. Offshore wind turbines, which have been designed for a 25-year operational lifespan, are expected to reach 30 years within the next decade due to advancements in structural design and condition-based monitoring and maintenance strategies.

While these approaches are more mature in the offshore wind sector, they provide relevant and transferable insights for wave energy technologies, particularly in terms of inspection planning, degradation management, and maintenance logistics. This is increasingly important as the renewable energy industry moves toward multisource offshore developments integrating co-located wind and wave devices. In such hybrid energy parks, aligning component lifetimes can improve overall resource efficiency and enable shared use of offshore infrastructure, including ports, vessels, inspection campaigns, and monitoring systems. Previous studies on co-located wind-wave developments suggest that this sharing of logistics and assets can reduce operational effort and associated costs per asset, which is particularly relevant for wave devices given their typically higher relative O&M intensity at early stages of deployment [49].

Material degradation, especially in submerged components, remains a significant challenge in marine environments. Corrosion and biofouling can be mitigated through appropriate material selection, durable coating systems, and inspection-triggered maintenance actions, all of which are directly applicable to wave devices.

However, fatigue caused by cyclic loading is the most critical challenge in lifespan extension [50]. Another relevant study [51] examined hydrofoil degradation in wave and tidal devices over 25 years of operation, identifying blades as critical components due to the significant cyclic loads experienced during energy production. These findings underline the need for targeted design, monitoring, and maintenance strategies focused on fatigue-sensitive components when considering lifetime extension in wave energy systems.

In practical applications, lifetime extension of wave energy devices can be supported by condition-based and predictive maintenance strategies, building on concepts already demonstrated in offshore wind but adapted to wave-specific loads, motions, and failure modes. Integrity assessments informed by monitoring data, potentially supported by simplified digital twin frameworks, can help detect early signs of degradation in key components such as hydrofoils, bearings, and structural connections, thereby reducing probability of failures and optimising intervention timing. While evidence of cost impacts is currently more mature in offshore wind, similar approaches are increasingly being explored for wave energy as device monitoring capabilities improve [52]. In addition, remote inspection technologies, including ROVs and AUVs, are particularly well suited to wave devices due to their frequent submergence and limited accessibility, offering potential reductions in offshore vessel time and personnel exposure.

To facilitate a comprehensive evaluation of lifetime extension impacts, this study proposed two strategies:

- 30-year design: Devices are designed to operate for 30 years without major component replacements, supported by conservative fatigue-oriented design choices and condition-based inspection to limit ageing-related failure risks. Additional O&M vessel use associated with extended operation is included.

- Mid-life replacement: Recognising the hydrofoil’s susceptibility to cyclic stresses, a planned replacement of this fatigue-critical component is assumed midway through the operational lifespan to ensure sustained reliability and performance. A planned replacement is assumed at year 15 and it includes additional composite material production and 5% of the vessel use from the installation phase for offshore intervention. Since the replacement procedure is assumed to require a relatively short intervention period, the associated downtime is considered negligible and no significant reduction in annual energy production is included in the analysis.

Both approaches accounted for the increased energy production during the extended operational period, assuming no performance degradation.

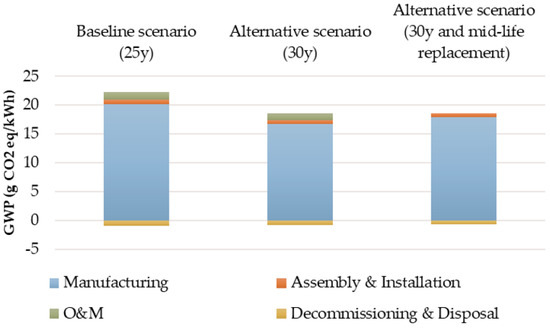

The results show that extending the design life to 30 years reduces the carbon footprint from 21.4 g CO2 eq/kWh (reference case, 25 years) to 17.8 g CO2 eq/kWh. When including a mid-life hydrofoil replacement, the footprint increases slightly to 19.0 g CO2 eq/kWh yet still remains below the reference case (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

GWP results for alternative scenarios (lifetime extension).

These findings highlight the importance of comprehensive feasibility studies and robust technical strategies for extending the operational life of offshore devices. By balancing economic benefits with regulatory compliance and environmental stewardship, such strategies contribute to the long-term success and sustainability of renewable energy systems.

4. Discussion

The lack of more accurate data on LCAs conducted in the field of wave energy poses a challenge in determining definitive conclusions on the viability of wave energy based on the existing literature. Furthermore, for a valid comparison between resulting impacts, it is essential that the studies use the same characterization factors and methodology. Nevertheless, a comparative analysis of the results was conducted in light of the current literature on other ocean energy sources and conventional energy production methods.

4.1. Comparison with Other Marine Renewable Energy Devices

A study conducted by [53], including fifteen tidal and wave energy technologies, concluded that the GWP may range from 15 g CO2 eq/kWh for enclosed-tip devices to 105 g eq/kWh for point absorber and rotating mass devices, with an average of 53 ± 29 g eq/kWh for all technologies. Despite being the same type of energy production, the indicated analyses cover different types of technologies and configurations and, considering the eventual variations in the methodology and premises assumed in these different assessments, it can be expected that this may justify the wide range presented by the results obtained presently.

Considering different types and configurations of WECs, the LCA results are consistent with the range found in the literature, as presented in Table 8 (13–123 eq/kWh). The cycloidal wave rotor shows GWP impact below the threshold of 25% of the average results obtained across the ten different reference technologies [18,39,51,54,55,56,57].

Table 8.

Carbon footprint and embodied energy estimates for different MRE devices.

Additionally, most studies agree that the manufacturing phase accounts for the most substantial contribution to the net impact, pointing also to the critical role played by the decommissioning and disposal phase. In contrast to the offshore wind energy sector, literature reviews [57] and LCA studies [58] indicate that the carbon footprint of wind energy devices can range from 11 to 23 g eq/kWh, depending on their adopted configuration and technologies. Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge the advanced level of maturity that this type of technology has achieved, which has allowed for its continuous enhancement over time.

4.2. Comparison with Other Types of Energy Generation

Regarding other sources of electricity generation, based on literature data [43,59], the cycloidal wave energy convertor presents itself as a promising low-carbon alternative, particularly when compared to traditional power generation methods, and it also demonstrates comparable results to solar photovoltaic technologies. Table 9 provides a summary of the carbon footprint associated with producing 1 kWh of electricity through various other means of production.

Table 9.

Carbon footprint and embodied energy estimates for different sources of energy production.

4.3. Other Implications for the Environmental Footprint

Beyond GHG emissions, the LCIA indicates that several additional environmental impact categories (non-climate midpoint indicators), such as terrestrial acidification, freshwater and marine eutrophication, and ecotoxicity, are highly sensitive to material choice, manufacturing processes, deployment logistics, and device lifetime. Consistent with the GWP profile, a large share of these burdens occurs upstream, particularly during manufacturing (steel and concrete production), which dominate impacts across multiple categories [41,60]. This hotspot structure is consistent with previous LCA studies of ocean or wind energy systems (e.g., [18,40]) and reflects the dominance of energy- and material-intensive industrial supply chains in shaping the overall environmental profile beyond climate change. This underscores that eco-design must consider supply-chain impacts alongside in-ocean pressures. Measures that reduce manufacturing burdens per unit electricity, such as increasing AEP, extending design lifetime, or optimising the steel-to-concrete balance, are therefore expected to deliver co-benefits across multiple impact categories on a per-kWh basis.

From a marine environmental perspective, additional co-impacts arise primarily from the use of coating systems, sacrificial anodes, and installation and maintenance activities. Although these contributions are relatively minor in terms of GWP, they may be ecologically relevant at local scales. Antifouling coatings and sacrificial anodes may introduce toxic substances into the marine environment, while installation and maintenance activities can disturb seabeds and generate underwater noise, affecting benthic habitats and marine organisms (e.g., [45]). Consequently, reducing coated surface area, increasing coating durability, and minimising recoating frequency are practical strategies to reduce toxicity-related burdens without compromising structural integrity (e.g., [47,61]).

Material selection is a key lever for achieving co-benefits across environmental impact categories. Substituting steel with concrete, assuming high end-of-life reuse, can reduce GWP and also lower toxicity- and eutrophication-related impacts per kWh. In contrast, aluminium and carbon fibre alternatives, while reducing mass, often increase embodied impacts due to energy-intensive manufacturing and limited recycling, especially for carbon fibre [43,62]. Therefore, these substitutions may not yield net environmental benefits when assessed across a broader set of impact categories. Emerging materials such as recyclable thermosets, thermoplastics, and bio-based composites offer promise for reducing toxicity and landfill burdens while maintaining mechanical performance [43,63,64]. However, their long-term behaviour in marine environments and under cyclic loading requires further investigation to ensure that reductions in manufacturing impacts are not offset by increased maintenance or replacement needs.

Overall, while GHG reduction remains a central objective, a broader environmental perspective shows that wave energy eco-design must balance land-based material burdens with marine ecological interactions. Strategies that increase energy yield, extend operational lifetime, optimise material use, and reduce ecotoxic releases are most likely to deliver co-benefits across climate, terrestrial, and marine impact categories.

4.4. Potential for Future Improvement

The early phase of MRE development is crucial for the technology’s market entry. During this phase, environmental risks, costs, and impacts, including those related to GHG emissions and biodiversity, are at their highest. Addressing concerns such as carbon footprint and energy intensity at the beginning of the development process is essential to identify critical points, tackle opportunities for improvement and generate market interest.

The identification of materials, processes and life cycle stages that contribute to global warming and energy consumption showed that manufacturing is responsible for over 80% of cycloidal wave converter estimated GWP impact.

The studies carried out within [65] introduce the potential for further optimization of the structure, by reducing the steel mass and increasing the amount of ballast concrete in counterpart. Through a rough estimate of 30% steel reduction and 30% concrete addition, a potential for around 19% GWP reduction is estimated. This meaningful variation stands for the assumption of a 90% reuse rate of concrete, implying credits towards the total impact. Additionally, a more recent study conducted by [24], considers the potential of the wave cycloidal rotor to increase the annual energy production by up to 70%, based on advanced control and high-fidelity numerical models. Considering the system efficiency and WECs availability, the GWP impact can be significantly reduced.

Another example of a potential improvement opportunity to reduce these environmental impacts could lie in further research into the application of lighter and less impactful materials, such as thermoplastic or flax fibre composite. The thermoplastic resin combines thermal welding techniques and, since it offers a higher potential for recyclability, has been considered for application in wind blades [66]. On the other hand, studies related to bio-based materials, such as flax fibre, indicate the possibility of reduced use of the material compared to steel, with less impact at the manufacturing stage, enabling a better EoL strategy with the re-use of the fibre and similar or lower costs than conventional composite materials [43].

However, the adoption of such novel material systems in wave energy applications requires careful evaluation. Their mechanical performance under cyclic loading, fatigue resistance in harsh marine environments, and long-term durability remain insufficiently understood. These structural uncertainties may influence component lifetime, replacement frequency, and maintenance requirements, potentially offsetting some of the environmental benefits gained from material substitution. Therefore, a comprehensive trade-off analysis is needed to assess whether reductions in manufacturing impacts are maintained once additional material replacement, offshore interventions, and operational downtime are taken into account over the full life cycle.

To understand the realistic impacts at a commercial scale, a future study could also consider the implementation of a wave cycloidal rotor at a site with increased energy production potential, which could reduce environmental impacts by about 50% per kWh of electricity produced, for example, in Ireland, considering the same technical and operational assumptions taken in the base case.

4.5. Material Considerations

The selection of alternative materials requires consideration beyond environmental performance, as it may affect the structural design, manufacturing processes, and long-term reliability of the device. For instance, replacing steel with fibre-reinforced composites can alter structural reliability, particularly in terms of yield and fatigue strength [16]. From a manufacturing perspective, steel benefits from mature fabrication routes and established quality control, whereas composite materials require different production processes and supply chains.

Long-term reliability also represents a key aspect when evaluating material alternatives. Composite materials may be susceptible to degradation mechanisms such as biofouling and erosion, potentially increasing maintenance requirements and reducing component lifetime. In offshore wave energy applications, such effects could negatively impact device availability and energy production, offsetting potential environmental gains [16].

Hence, the introduction of alternative materials for structural components requires a holistic assessment, in which environmental benefits are evaluated alongside structural reliability, manufacturability, offshore maintainability, and cost considerations [16].

5. Conclusions

This LCA builds on previous findings presented in [22] and was carried out to assess the embodied carbon and energy of a cycloidal rotor wave farm and to comprehend the key factors that may influence the potential emissions, by characterizing the material and process flows, including the main stages from cradle to grave.

This study brings new insights into the environmental performance of floating cycloidal wave energy technology, discusses alternative scenarios for carbon embodiment in terms of materials, site selection and lifetime extension schemes, and provides an insight into further environmental considerations beyond carbon emission reduction.

The key findings are summarised as follows:

- Baseline performance (France): Carbon intensity of 21.4 g eq/kWh and energy intensity of 344 kJ/kWh, with manufacturing (mainly steel and concrete) contributing over 80% of total GWP.

- Material selection: Steel provides high recyclability; aluminium and carbon fibre composites reduce structural mass but increase GWP by 171% and 1110%, respectively, due to energy-intensive production and limited end-of-life options.

- Site effects: Deployment in Portugal and Ireland reduces GWP per kWh by 6% and 50%, with carbon payback times dropping from 9.8 years (France) to 1.4 and 0.4 years, respectively.

- Lifetime extension: Extending operational life from 25 to 30 years reduces GWP by 17%, and mid-life component replacement still improves environmental performance compared to the baseline.

- Key drivers of performance: Manufacturing dominates life cycle impacts, while deployment site, material choice, and operational lifetime significantly influence overall sustainability.

These findings are relevant for developers, policymakers, and investors in marine renewable energy (MRE). Optimizing material selection, site deployment, and maintenance strategies can enhance the sustainability of wave energy devices, and in particular wave cycloidal rotors. The results support design guidelines that prioritize holistic frameworks for material selection, lifetime extension through refurbishment, and deployment in high-resource locations. It is recommended that future research focus on material manufacturing and end-of-life processes, material selection frameworks, cyclorotor performance in harsh environmental conditions, and detailed maintenance planning. Additionally, the combination of wind and wave farms could further reduce the environmental impacts and deployment costs of offshore renewable energy projects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, writing—original draft preparation P.B.; writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, A.A.-G., writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, F.D.-M., writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, J.F.C., writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, P.L.-K., writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, P.A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the LiftWEC project, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 851885. This work was also partially funded by Alliance for the Energy Transition (56), co-financed by the Recovery and Resilience Plan through the European Union.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the members of the LiftWEC consortium, in particular Kim Nielsen, Rémy Pascal, and Francesco Ferri, for their input to Deliverable 8.6 LCoE of the Final Configuration. We also thank Andrei Ermakov and John V. Ringwood for their contributions to the assessment of the power yield of the wave cycloidal rotor with advanced control techniques. These inputs provided essential data for the present work.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Julia Fernandez Chozas was employed by the company Julia F. Chozas, Consulting Engineer. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries. WaveFarm Unleashes a Wave of Energy for a Sustainable Future. European Commission Website. 2024. Available online: https://oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu/news/wavefarm-unleashes-wave-energy-sustainable-future-2024-01-31_en (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Directorate-General for Energy. Communication on Innovative Technologies and Forms of Renewable Energy Deployment. European Commission Website. 2025. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/publications/communication-innovative-technologies-and-forms-renewable-energy-deployment_en (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Arredondo-Galeana, A.; Olbert, G.; Shi, W.; Brennan, F. Near wake hydrodynamics and structural design of a single foil cycloidal rotor in regular waves. Renew. Energy 2023, 206, 1020–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredondo-Galeana, A.; Ermakov, A.; Shi, W.; Ringwood, J.V.; Brennan, F. Optimal control of wave cycloidal rotors with passively morphing foils: An analytical and numerical study. Mar. Struct. 2024, 95, 103597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Chozas, J.; Tetu, A.; Arredondo-Galeana, A. Parametric Cost Model for the Initial Techno-Economic Assessment of Lift-Force Based Wave Energy Converters. In Proceedings of the 14th European Wave and Tidal Energy Conference, Plymouth, UK, 5–9 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Folley, M.; Whittaker, T. Lift-based wave energy converters—An analysis of their potential. In Proceedings of the 13th European Wave and Tidal Energy Conference, Naples, Italy, 1–6 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stasinopoulos, I.; Ermakov, A.; Ringwood, J.V. Relative Foil-Fluid Velocity Estimation and Forecasting for Cyclorotor Wave Energy Conversion. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2025 Brest, Brest, France, 16–19 June 2025; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasinopoulos, I.; Ermakov, A.; Ringwood, J.V. Nonlinear model predictive control strategies for a cyclorotor wave energy device. In Proceedings of the 2025 European Control Conference (ECC), Thessaloniki, Greece, 24–27 June 2025; pp. 2638–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasinopoulos, I.; Ermakov, A.; Ringwood, J.V. Control co-design for cyclorotor wave energy conversion. Proc. Eur. Wave Tidal Energy Conf. 2025, 16, 772-1–772-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, S.G.; Jeans, T.; McLaughlin, T. Intermediate Ocean Wave Termination Using a Cycloidal Wave Energy Converter. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Shanghai, China, 6–11 June 2010; pp. 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, S. Wave radiation of a cycloidal wave energy converter. Appl. Ocean Res. 2015, 49, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermakov, A.; Ringwood, J.V. A control-orientated analytical model for a cyclorotor wave energy device with N hydrofoils. J. Ocean Eng. Mar. Energy 2021, 7, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermakov, A.; Thiebaut, F.; Payne, G.S.; Ringwood, J.V. Validation of a control-oriented point vortex model for a cyclorotor-based wave energy device. J. Fluids Struct. 2023, 119, 103875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olbert, G.; Abdel-Maksoud, M. High-fidelity modelling of lift-based wave energy converters in a numerical wave tank. Appl. Energy 2023, 347, 121460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtat, A.; Fagley, C.; Chitale, K.C.; Siegel, S.G. Efficiency analysis of the cycloidal wave energy convertor under real-time dynamic control using a 3D radiation model. Int. Mar. Energy J. 2022, 5, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredondo-Galeana, A.; Yeter, B.; Abad, F.; Ordóñez-Sánchez, S.; Lotfian, S.; Brennan, F. Material Selection Framework for Lift-Based Wave Energy Converters Using Fuzzy TOPSIS. Energies 2023, 16, 7324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karan, H.; Thomson, R.C.; Harrison, G.P. Full life cycle assessment of two surge wave energy converters. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A J. Power Energy 2020, 234, 548–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apolonia, M.; Simas, T. Life Cycle Assessment of an Oscillating Wave Surge Energy Converter. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennock, S.; Vanegas-Cantarero, M.M.; Bloise-Thomaz, T.; Jeffrey, H.; Dickson, M.J. Life cycle assessment of a point-absorber wave energy array. Renew. Energy 2022, 190, 1078–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelfried, T.; Cucurachi, S.; Lavidas, G. Life cycle assessment of a point absorber wave energy converter. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2025, 16, 100265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhapurage, H.; Koliyabandara, P.A.; Samarakoon, G. Life Cycle Assessment of an Oscillating Water Column-Type Wave Energy Converter. Energies 2025, 18, 2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, P.; Devoy-McAuliffe, F.; Arredondo-Galeana, A.; Chozas, J.; Lamont-Kane, P.; Vinagre, P.A. Life Cycle Assessment of a wave energy device—LiftWEC. In Proceedings of the 15th European Wave and Tidal Energy Conference, Bilbao, Spain, 3–7 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Devoy-McAuliffe, F. Deliverable D7.5—Assessment of Final Configurations. 2023. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/851885/results (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Nielsen, K.; Chozas, J.F.; Pascal, R.; Ferri, F. Deliverable D8.6—LCoE of the Final Configuration. 2023. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/851885/results (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Siegel, S.G. Numerical benchmarking study of a Cycloidal Wave Energy Converter. Renew. Energy 2019, 134, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ReCiPe. ReCiPe v1.13. 2016. Available online: http://www.lcia-recipe.net/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Bulle, C.; Margni, M.; Patouillard, L.; Boulay, A.M.; Bourgault, G.; De Bruille, V.; Cao, V.; Hauschild, M.; Henderson, A.; Humbert, S.; et al. IMPACT World+: A globally regionalized life cycle impact assessment method. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2019, 24, 1653–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folley, M.; Lamont-Kane, P.; Frost, C. A Linear hydrodynamic model of rotating lift-based wave energy converters. Int. Mar. Energy J. 2023, 6, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont-Kane, P.; Folley, M.; Frost, C.; Whittaker, T. Conceptual hydrodynamics of 2 dimensional lift-based wave energy converters. Ocean Eng. 2024, 298, 117084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlsten, H. Life Cycle Assessment of Electricity from Wave Power. Master’s Thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wello. CEFOW-Penguin Array. 2018. Available online: https://marine.gov.scot/sites/default/files/project_information_summary_1.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- ACTEON. BRUCE® FFTS Mk 4 ANCHOR. Available online: http://www.bruceanchor.co.uk (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- ABB. XLPE Submarine Cable Systems—Attachment to XLPE Land Cable Systems—User’s Guide—Rev 5. Available online: https://new.abb.com/docs/default-source/ewea-doc/xlpe-submarine-cable-systems-2gm5007.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Birkeland, C. Assessing the Life Cycle Environmental Impacts of Offshore Wind Power Generation and Power Transmission in the North Sea. Ph.D. Thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Noorwegen, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby, M.F. Materials and the Environment—Eco-Informed Material Choice, 2nd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Electric. The Full Solution for Submerged Arc Welding. 2019. Available online: https://doublegood.com.vn/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2019.06.02-Double-Good-JSC-The-full-solution-for-SAW-English.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Thomson, R.C.; Chick, J.P.; Harrison, G.P. An LCA of the Pelamis wave energy converter. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2019, 24, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinzettel, J.; Reenaas, M.; Solli, C.; Hertwich, E.G. Life cycle assessment of a floating offshore wind turbine. Renew. Energy 2009, 34, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Steinmann, Z.J.N.; Elshout, P.M.F.; Stam, G.; Verones, F.; Vieira, M.; Zijp, M.; Hollander, A.; van Zelm, R. ReCiPe2016: A harmonised life cycle impact assessment method at midpoint and endpoint level. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurtsbaugh, W.A.; Paerl, H.W.; Dodds, W.K. Nutrients, eutrophication and harmful algal blooms along the freshwater to marine continuum. WIREs Water 2019, 6, e1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.R.; Thies, P.R. A life cycle assessment comparison of materials for a tidal stream turbine blade. Appl. Energy 2022, 309, 118353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Zhao, J.; Hollberg, A.; Habert, G. Where to focus? Developing a LCA impact category selection tool for manufacturers of building materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 405, 136936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavelli, L.; Copping, A.E.; Hemery, L.G.; Freeman, M.C. OES-Environmental 2024 State of the Science Report: Environmental Effects of Marine Renewable Energy Development Around the World; Report for Ocean Energy Systems (OES); OES: Lisbon, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Daljit Singh, J.K.; Molinari, G.; Bui, J.; Soltani, B.; Rajarathnam, G.P.; Abbas, A. Life Cycle Assessment of Disposed and Recycled End-of-Life Photovoltaic Panels in Australia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhl, M.; Hauschild, M.Z.; Dam-Johansen, K. Sustainability of corrosion protection for offshore wind turbine towers. Prog. Org. Coatings 2024, 186, 107998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredondo-Galeana, A.; Scarlett, G.T.; Collu, M.; Brennan, F. A hybrid floating wind-wave energy platform for minimum power baseload. Ocean Eng. 2026, 343, 123090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperadore, A.; Correia da Fonseca, F.; Amaral, L. Assessing the lifetime O&M costs of co-located floating offshore wind and wave farms: A case study in Viana do Castelo, Portugal. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Ocean Energy (ICOE 2024), Melbourne, Australia, 17–19 September 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hans Chr., S.; Stefan, N.; Stefan, A.; Hauschild, M. Life Cycle Assessment of the Wave Energy Converter: Wave Dragon; Poster session presented at Conference in Bremerhaven, DTU Technical University of Denmark. 2007. Available online: https://backend.orbit.dtu.dk/ws/files/3711218/WaveDragon.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Walker, S.; Howell, R. Life cycle comparison of a wave and tidal energy device. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part M J. Eng. Marit. Environ. 2011, 225, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yin, P. An opportunistic condition-based maintenance strategy for offshore wind farm based on predictive analytics. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 109, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uihlein, A. Life cycle assessment of ocean energy technologies. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, G.; Madden, D.; Daly, M.C. Life Cycle Assessment of the Wavestar. In Proceedings of the 2014 Ninth International Conference on Ecological Vehicles and Renewable Energies (EVER), Monte-Carlo, Monaco, 25–27 March 2014; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, Q.; Zhu, L.; Lu, S. Life Cycle Assessment of a Buoy-Rope-Drum Wave Energy Converter. Energies 2018, 11, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrizi, N.; Pulselli, R.M.; Neri, E.; Niccolucci, V.; Vicinanza, D.; Contestabile, P.; Bastianoni, S. Lifecycle Environmental Impact Assessment of an Overtopping Wave Energy Converter Embedded in Breakwater Systems. Front. Energy Res. 2019, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GarciaTeruel, A.; Romero, A.; Jeffrey, H. Flotant Deliverable D7.3: Environmental Life Cycle Assessment. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5ecc0e641&appId=PPGMS (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Bonou, A.; Laurent, A.; Olsen, S.I. Life cycle assessment of onshore and offshore wind energy-from theory to application. Appl. Energy 2016, 180, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.; Howell, R.; Hodgson, P.; Griffin, A. Tidal energy machines: A comparative life cycle assessment study. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part M J. Eng. Marit. Environ. 2015, 229, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashedi, A.; Khanam, T.; Jeong, B.; Hussain, M. Evaluation of environmental sustainability matrix of Deepgen tidal turbine. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 113031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrek-Gerstenkorn, B.; Paul, S. Metallic coatings in offshore wind sector—A mini review. npj Mater. Degrad. 2024, 8, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S. Life cycle assessment of carbon fiber-reinforced polymer composites. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2011, 16, 268–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, G.; Yao, Y.; Wei, X.; Pan, T.; Wu, J.; Tian, M.; Yin, P. Recent advances in recyclable thermosets and thermoset composites based on covalent adaptable networks. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 92, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattilo, S.; Cicala, G.; Riccobene, P.M.; Puglisi, C.; Saitta, L. Full Recycling and Re-Use of Bio-Based Epoxy Thermosets: Chemical and Thermomechanical Characterization of the Recycled Matrices. Polymers 2022, 14, 4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papillon, L.; Pimoult, M.; Baron, C.; Pascal, R. Deliverable D3.4—Implementation of Coupled Hydrodynamic Model. 2023. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/851885/results (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Murray, R.E.; Beach, R.; Barnes, D.; Snowberg, D.; Berry, D.; Rooney, S.; Jenks, M.; Gage, B.; Boro, T.; Wallen, S.; et al. Structural validation of a thermoplastic composite wind turbine blade with comparison to a thermoset composite blade. Renew. Energy 2021, 164, 1100–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.