Abstract

The present study has applied a probabilistic oil spill modeling framework to assess the potential risks associated with offshore oil spills in the Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin, a region of exceptional ecological importance and increasing geopolitical and socio-environmental relevance. By integrating a large ensemble of simulations with validated hydrodynamic, atmospheric and wave-driven forcings, the analysis of said simulations has provided a robust and seasonally resolved assessment of oil drift and beaching patterns along the Guianas and the Brazilian Equatorial Margin. The model has presented a total of 47,500 simulations performed on 95 drilling sites located across the basin, using the Lagrangian Spill, Transport and Fate Model (STFM) and incorporating a six-year oceanographic and meteorological variability. The simulations have included ocean current fields provided by HYCOM, wind forcing provided by GFS and Stokes drift provided by ERA5. Model performance has been evaluated by comparisons with satellite-tracked surface drifters using normalized cumulative Lagrangian separation metrics and skill scores. Mean skill scores have reached 0.98 after 5 days and 0.95 after 10 days, remaining above 0.85 up to 20 days, indicating high reliability for short to intermediate forecasting horizons and suitability for probabilistic applications. Probabilistic simulations have revealed a pronounced seasonal effect, governed by the annual migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). During the JFMA period, shoreline impact probabilities have exceeded 40–50% along extensive portions of the French Guiana and Amapá state (Brazil) coastlines, with oil reaching the coast typically within 10–20 days. In contrast, during the JASO period, beaching probabilities have decreased to below 15%, accompanied by a substantial reduction in impact along the coastline and higher variability in arrival times. Although coastal exposure has been markedly reduced during JASO, a residual probability of approximately 2% of oil intrusion into the Amazonas river mouth has persisted.

1. Introduction

Recently, oil drilling has been proposed in the Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin, a territory bordered by highly protected areas in the Brazilian Amazon. These new drilling areas are likely to be given the green light in upcoming years, putting the area’s biodiversity and the socio-economic well-being of local populations at potential risk [1].

In recent years, discussions concerning environmental licensing and the authorization for offshore oil exploration in the Equatorial Margin (mainly in the Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin) have gained traction. The controversy began to escalate in 2023, when Petrobras formally requested environmental licensing from IBAMA to begin exploratory drilling in Block FZA-M-59, located off the coast of Amapá State, approved in 2025. As a result, the Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin licensing process has become a central test case for Brazil’s environmental governance effectiveness, highlighting the tension between environmental precaution and energy expansion in a context of global climate commitments and increasing scrutiny of the country’s environmental policies [1].

The Brazilian Amazon (BA) coastal region extends from Tubarão Point in Maranhão State to Cape Orange in Amapá State—encompassing the coasts of Amapá, Pará and western Maranhão. The region covers approximately 7820 km2, of which about 92% consists of mangrove forests interspersed with numerous inlets, islands and small estuaries [2]. The BA is part of the Brazilian Equatorial Margin (BEM), a passive transform continental margin that includes both emerged and offshore areas along the states of Rio Grande do Norte, Ceará, Piauí, Maranhão, Pará and Amapá. The BEM is structurally influenced by major tectonic lineaments such as the Chain, Romanche and São Paulo Fracture Zones [2] (Figure 1).

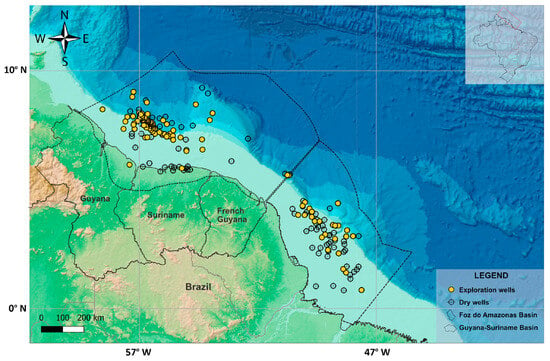

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of offshore oil and gas wells in the Foz do Amazonas and Guyana–Suriname sedimentary basins, highlighting exploration wells (yellow circles), dry wells (open circles), with bathymetric shading indicating the continental shelf, slope and deep-ocean regions.

The Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin, located in the BEM, is classified as a pull-apart-related basin that formed along a transform margin and later evolved into a passive margin, influenced by extensional tectonic regimes associated with rifting during the opening of the Central Atlantic (Triassic–Jurassic) and by compressional stress related to the uplift of the Andes along the western margin of the South American continent (Cenozoic) [3,4,5]. During the rift phase, the extensional regime produced grabens segmented by transform faults, en échelon structures and listric normal faults, while Andean tectonism promoted intense sediment influx responsible for the formation of the Amazon Cone, an important depositional feature on the ocean floor [6]. This tectonostratigraphic framework was crucial for the development of the main elements of a petroleum system: source rocks, reservoirs, seals and structural traps.

The basin has recently drawn the attention of the oil and gas industry due to its potential for hydrocarbon exploration and production. The petroleum systems of the Equatorial Margin are believed to mirror those of West Africa, where prolific discoveries—such as the Jubilee Field in the Tano basin, offshore Ghana—have occurred in similar geological settings [7]. Recent deepwater discoveries, including the Zaedyus well off French Guiana and the Pecém well in the Ceará basin, have only served to reinforce the geological similarities between the Brazilian Equatorial Margin and the West African coast. In addition to that, the Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin lies to the east of the Guyana–Suriname basin and both share a similar origin and geological characteristics. Given the major hydrocarbon discoveries in the Guyana–Suriname basin and West Africa [8].

Although the region remains largely underexplored compared to other South Atlantic basins [9], offshore blocks within the Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin have already shown high potential for oil and gas exploration as revealed by recent drilling and seismic acquisition initiatives [10,11,12].

The Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin hosts four petroleum systems, two proven, one hypothetical and one speculative [4,5,6,7,8], with Limoeiro Formation marine shales having been identified as the most promising one in source rocks. Within this context, the oil found in the Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin is expected to exhibit relatively low API gravity, similar to that observed in the Guyana–Suriname basin. This expectation is consistent with the API gravity of approximately 27° reported by TotalEnergies Company for oils recovered from exploratory blocks in the area [13]. However, geochemical analyses of hydrocarbons from the basin’s deep-water Travassos–Pirarucu petroleum system have also indicated the presence of high-content paraffin, low-content sulfur oils with elevated API gravity [14,15].

The Amazon region, therefore, presents a complex paradox. On one hand, oil and gas exploration represents an important economic frontier for Brazil and its neighboring countries. On the other hand, this development intersects with one of the most ecologically sensitive environments on Earth. In 2019, five Amazonian nations—Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador and Peru—accounted for nearly 87% of South and Central America’s total oil production and held over 18% of the world’s proven reserves [16]. Recent discoveries, such as those in the Guyana–Suriname basin (over 12 billion barrels of oil equivalent), have intensified exploration efforts along the northern margin of South America [17]. In Brazil, the oil debate reached its peak in 2023 when IBAMA denied Petrobras’s drilling request in the FZA-M-59 block [18], mirroring the 2018 rejection of Total’s project due to inadequate environmental impact assessment [19].

The BEM is also strongly influenced by the North Brazil Current (NBC) system, which creates dynamic oceanographic conditions that may complicate drilling operations and oil spill response. The presence of gas hydrates, over-pressured formations and unstable sediments increases the likelihood of operational failures, such as wellbore instability or blowouts—scenarios that could result in significant environmental impacts [20,21,22].

From an ecological perspective, the Amazon coastal zone is among the most biodiverse but also least studied regions of the Brazilian coast [23,24,25,26]. It supports extensive mangrove forests, estuaries, lagoons and reef systems that serve as critical habitats for manatees, sea turtles, migratory birds and numerous fish species [27,28]. The Great Amazon Reef System (GARS), extending across the Amazon shelf, hosts unique mesophotic coral ecosystems and a high diversity of reef-associated fauna [29,30].

Given this context, oil spill modeling plays a crucial role in environmental risk assessment and contingency planning for future offshore operations. Understanding the dispersion, trajectory and potential beaching of spilled oil is imperative to guide Environmental Sensitivity Index (ESI) mapping and optimize emergency response strategies [31]. Accurate modeling enables decision-makers to anticipate spill behavior under different oceanographic and meteorological scenarios, ensuring that response measures are both effective and environmentally responsible.

Therefore, in light of the growing interest in petroleum exploration along the Brazilian Equatorial Margin and the many environmental concerns that come with it, this study aims to apply a probabilistic modeling approach to assess possible oil spill events in the Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin to predict main beaching areas and drift time under several different seasonal conditions. The results allow the identification of the most vulnerable areas and their potential exposure to oil spills. Furthermore, the study also provides insights into the effectiveness of preventive and response measures, contributing to the development of more robust contingency plans and environmental management strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

In 2019, Brazil faced one of the biggest ecological disasters in its recent history when an extensive and mysterious oil spill spread across an area of more than 3000 km of coastline across 11 northeastern states. The event, which began in late August and persisted for several months, contaminated over a thousand beaches, estuaries and mangrove ecosystems, severely affecting marine biodiversity, artisanal fisheries, tourism and local livelihoods [32,33]. Despite the magnitude of the incident, the origin of the dumped oil remained uncertain for a long period, exposing significant gaps in Brazil’s marine monitoring, early warning and rapid response capabilities [34,35]. The lack of an integrated system capable of detecting, tracking and forecasting oil dispersion in real time highlighted the country’s vulnerability to maritime spills, particularly in the context of increasing offshore oil exploration and shipping. In response to this event, the coordinated efforts of several Brazilian government agencies have led to the development of a new program for oil spill monitoring and modeling, SisMOM (Sistema Multiusuário de detecção, previsão e monitoramento de derrame de Óleo no Mar; i.e., Multiuser System for Offshore Oil Spill Detection, Forecast and Monitoring) [36,37,38].

One of the components of SISMOM’s development relies on oil spill open-source models, such as the Spill Transport and Fate Model (STFM) [39,40,41,42], the Coupled Model for Oil Spill Prediction (CMOP) [43,44], the General NOAA Operational Modeling Environment (PyGNOME) [45,46] and the OpenDrift/OpenOil [47]. Other models were also considered in the early stages of the project but then subsequently ruled out throughout the development of this study [36,38]. These models can be executed independently or integrated within an ensemble framework. The ensemble approach is designed to improve the reliability of simulations by accounting for uncertainties inherent in model formulations, such as initial conditions and environmental forcing.

The Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin stands as one of the most environmentally significant regions of the tropical Atlantic, hosting highly sensitive ecosystems and biodiversity hotspots. Prospective offshore oil exploration in this area raises substantial concerns due to the potential of severe environmental impacts as well as the possibility of transboundary incidents given the basin’s proximity to the Guyana–Suriname maritime frontier. Although previous studies have examined the Equatorial Margin as a broad system [48], they have not provided a focused, basin-scale assessment of spill behavior specifically for the Foz do Amazonas region, where circulation patterns, mesoscale activity and ecological vulnerability differ from adjacent sectors of the margin. In order to fill this gap, STFM v.1.0.3 (20250606) has been employed as the core modeling framework integrated into SISMOM [36,38]. STFM provides the computational efficiency required to perform a large number of probabilistic simulations (hundreds of thousands)—a key requirement for quantifying environmental risk in such a dynamic region—unlike Python-based models such as OpenDrift, which are typically limited to a few hundred runs due to computational constraints [47,48].

2.1. Spill, Transport and Fate Model

The Spill Transport and Fate Model (STFM) is an open-source Lagrangian framework designed to simulate the transport, transformation and weathering of oil in marine and coastal environments. It was developed to represent the main physical and chemical processes influencing oil behavior at sea, including advection by surface currents and wind, turbulent diffusion, spreading, evaporation, emulsification, dispersion and sedimentation. The model tracks a set of discrete particles that collectively represent the released oil, each carrying its physical and chemical properties such as volume, density, viscosity and weathering state [39,40].

Two of the main advantages of STFM v.1.0.3 (20250606) are its flexibility and customization, which make it suitable for both deterministic and probabilistic applications. Deterministic simulations are typically run to reproduce specific spill events under known conditions, whereas probabilistic simulations employ multiple realizations with varying environmental forcings and initial parameters in order to estimate the likelihood of oil reaching sensitive coastal areas. The model output includes oil trajectory maps, time series of particle distribution and probability-of-impact maps, which can be further integrated with Environmental Sensitivity Index (ESI) data for environmental risk assessment [35].

STFM features a modular framework, allowing users to select the equations that are to be involved in the simulation’s numerical setup. Additionally, the STFM offers multiple alternatives for most transport and weathering effects. The chosen transport equations adhere to the design that has been previously validated [39,40,41,42]. Currently, the model includes Stokes drift [35].

STFM operates on a modular structure that allows coupling with hydrodynamic and atmospheric models in order to provide realistic environmental forcing. Ocean current fields, wind velocity, wave energy and temperature are usually provided by external models such as HYCOM [49] and WRF [50]. The model can simulate both surface and subsurface oil transport, including the entrainment of droplets into the water column and potential resuspension under high-energy conditions [41,42] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the governing equations and parameterizations implemented in the STFM framework for oil spill probabilistic modeling.

The STFM uses environmental forcing directly from HYCOM and GFS output files, reading the native formats provided by the respective model data providers, without intermediate reprocessing. Spatial interpolation is performed using an inverse distance squared weighting scheme, based on the four nearest grid elements surrounding each computational particle. Temporal interpolation is carried out using a linear method, considering the model outputs from the immediately preceding and subsequent time steps. If invalid data values are detected within any input file, the STFM automatically terminates the simulation and issues a warning to prevent the propagation of erroneous forcing fields. In cases where entire input files are missing (i.e., complete temporal gaps), the STFM performs temporal interpolation using the closest available subsequent time step, ensuring continuity of the environmental forcing [39,40,41].

2.2. Probabilistic Modeling

Oil spill modeling plays a crucial role in supporting prevention, preparedness and response strategies to marine pollution. Deterministic models have traditionally been used to simulate the trajectory and fate of oil slicks under specific environmental conditions. Probabilistic approaches aim to quantify these uncertainties by running large ensembles of simulations that account for the stochastic factors of the environment [33].

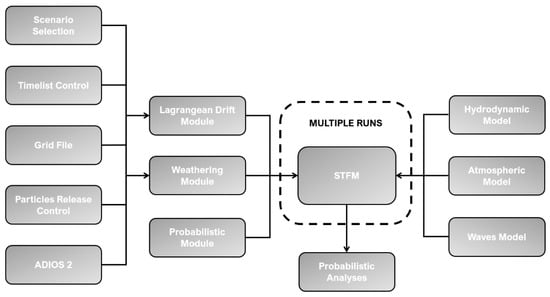

Probabilistic oil spill modeling is a methodology that simulates the same hypothetical oil spill scenarios in several different initial conditions (Figure 2) in order to estimate the spatial and temporal likelihood of oil reaching different environmental zones, taking into account the uncertainty of both input data and model processes. The most common approach to implement the probabilistic modeling is to select a sufficiently long data period (for example, five or more years) and randomly sample a large number of initial spill times (dates/hours) for each scenario [33].

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the STFM probabilistic modeling framework. The deterministic model integrates hydrodynamic and atmospheric forcing to simulate Lagrangian particle transport and oil weathering as well as fate processes. Multiple time-variant deterministic runs are integrated to generate the probabilistic model, which then provides statistical estimates of oil drift and variability.

In order to avoid performance compromise, all main oil spill weathering are included in a simple way: advection (movement of oil by currents and wind), spreading (the rapid initial expansion of the slick under gravitational and density forces), turbulent diffusion (internal mixing of the slick due to chaotic motions), sinking (transport of oil droplets into the water column or sedimentation), evaporation (loss of volatile fractions to the atmosphere) and emulsification (entrainment of water into the oil, increasing its volume and changing its physical properties) [53,54,55,56].

This approach runs many simulations (often hundreds to thousands) across a range of possible initial conditions and the results are then combined to produce probability maps for both the oil trajectories and beaching. The results also indicate the likelihood of impact on specific shoreline segments, marine habitats or local communities as well as the expected affected areas, oil thickness or concentration and exposure duration [33,35].

The probabilistic model was configured according to Table 2. Simulations were initialized at the positions shown in Figure 1, corresponding to the wells located in the Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin within Brazilian jurisdictional waters. The selected volume (1000 metric tons) was consistent with a medium-intensity pipeline leak, similar to others that have occurred under operational conditions on offshore platforms along the Brazilian coast [37,38]. API degree, distillation curve, composition and physicochemical characterization of the oil were available in the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) [57] provided by IBAMA (Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis).

Table 2.

Summary of the main input parameters used in the STFM probabilistic oil spill simulations for the Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin.

Initial slick conditions were defined by both the physical properties of the released oil and the numerical configuration of the Lagrangian particle field. The initial area was given by the Gravitational Spreading Initial Area Equation (Table 1) and the oil thickness was calculated according to the estimated surface area of the initial slick (Table 1), resulting in a uniform thickness distribution within the initial area. Lagrangian elements were distributed evenly across this area to ensure an unbiased representation of the initial oil patch, with each element carrying an equal fraction of the total mass. Particle positions were initialized within the defined release area using a random uniform distribution in order to prevent artificial clustering and allow the model to capture the natural spreading dynamics of the simulation. All initial positions are listed in the Supplementary Materials S1 (JFMA)—Table S1.

2.3. Current Input Data: HYCOM

HYCOM (Hybrid Coordinate Ocean Model) is a global ocean circulation numerical model developed by collaborative efforts among the University of Miami (RSMAS), the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL), the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) and the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), under the HYCOM consortium coordinated by the U.S. Navy, NOAA and NASA. Traditional ocean circulation models typically employ a single type of vertical coordinate to represent the ocean’s physical properties (depth, density or topography). However, inter-model comparisons have demonstrated that using only one vertical coordinate system is insufficient to accurately represent oceanic physical properties throughout the water column [58] (Halliwell, 2001). HYCOM’s main innovation lies in its hybrid vertical coordinate scheme, which dynamically transitions among isopycnal, sigma and z-level systems according to local density and depth characteristics. This approach allows a more realistic representation of both large-scale processes, such as global ocean currents and mesoscale to submesoscale phenomena, including fronts, eddies and upwelling zones [59].

In addition, HYCOM integrates satellite and in situ data with advanced data assimilation systems, significantly improving the representation of variables such as temperature, salinity, currents and sea surface height. These features make the model one of the main sources of hydrodynamic data for applications that rely on realistic ocean circulation simulations, including oil-spill modeling. In such applications, HYCOM outputs are used as forcing fields (current, density, temperature and sea surface height) for Lagrangian models that simulate trajectory and fate, reproducing advection and diffusion processes under the combined influence of winds and tides [60,61].

One of the key strengths of HYCOM is its data assimilation framework: operational systems such as the Global Ocean Forecast System (GOFS 3.1) employ the Navy Coupled Ocean Data Assimilation (NCODA), which integrates satellite altimetry, sea-surface temperature products and in situ hydrographic profiles from Argo floats, moorings and other platforms. This assimilation methodology has been shown to systematically reduce forecast errors and improve fidelity in both surface and subsurface fields [58,59].

Despite its strong performance at large scales, some limitations require caution when using HYCOM for regional or coastal applications. The accuracy of surface and subsurface currents is known to vary by region, with larger discrepancies reported in dynamically complex areas such as the Gulf Stream and the North Atlantic Warm Current. HYCOM can also struggle to represent rapid salinity changes in narrow coastal zones or within river-dominated environments. Furthermore, standard global configurations generally do not include explicit tidal forcing, which may lead to mismatches in areas where tidal currents significantly modulate deep or shelf circulation. HYCOM data quality also depends on the accuracy of its atmospheric forcing (e.g., wind stress and heat fluxes) and parameterizations, meaning that uncertainties in external inputs can directly affect the ocean fields [60,61].

2.4. Atmospheric Input Data: GFS

The Global Forecast System (GFS) is a numerical weather prediction model developed by the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) which generates data for dozens of atmospheric and surface variables, including temperature, wind, precipitation, soil moisture and atmospheric ozone concentration. The system combines four distinct components—atmosphere, ocean, land and sea ice—which operate interactively to provide a more accurate representation of global weather conditions. GFS produces forecasts based on the solution of the fundamental equations of atmospheric dynamics and thermodynamics, integrated every six hours and extending up to 16 days in advance. The model uses a global grid with variable spatial resolution (currently about 13 km or 0.25° in the operational version) and 64 vertical layers with higher resolution near the surface and top of the atmosphere. It also incorporates key physical processes such as radiation, convection, turbulence, cloud microphysics and energy exchanges between the atmosphere, land surface and the ocean [62]. In addition, GFS employs advanced data assimilation systems—incorporating satellite, in situ and airborne observations—that continuously update the model’s initial conditions in order to improve short- and medium-range forecasts.

GFS is widely used in a variety of coupled modeling systems, including ocean, wave, atmospheric dispersion and pollutant transport models [63,64]. In ocean and oil-spill modeling, for instance, the wind fields generated by GFS are frequently employed as atmospheric forcings for hydrodynamic models such as HYCOM as well as for Lagrangian dispersion models, influencing the trajectory and diffusion of particles or contaminants at the ocean surface [65,66].

The model’s data quality, however, may vary by region and forecast lead time. Precipitation forecasts are among the most uncertain components with well-documented biases, such as overestimation of convective rainfall in the tropics and spatial displacement errors in mid-latitude storm systems. Near-surface variables—including 10 m winds, surface pressure, temperature and humidity—also show regional sensitivity, with degraded performance over complex coastal zones, mountainous terrain and areas strongly influenced by land–atmosphere feedbacks. Forecast skills become even more unreliable after 7–10 days, reflecting the intrinsic increase in atmospheric uncertainty in deterministic models. Long-range GFS forecasts, therefore, should be interpreted as low-confidence guidance rather than deterministic predictions. Additionally, the model’s accuracy can be affected by errors inherited from its atmospheric forcing fields, cloud microphysics parameterizations and boundary-layer schemes, which influence the representation of convection, storms and boundary-layer dynamics [62,63,64].

2.5. Stokes Drift Velocity Input Data: ERA-5

Stokes drift velocity data used in this study are derived from the ERA5 reanalysis, developed by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) [67]. ERA5 provides globally consistent estimates of atmospheric and oceanic variables with hourly temporal and 1/4° × 1/4° spatial resolution. The zonal (eastward) and meridional (northward) wind velocity fields, measured at 10 m above mean sea level under calm-sea conditions, are available from 1940 to present day and are updated daily [68]. The Stokes drift component in ERA5 is computed from the directional wave spectrum generated by WAM (Wave Model), which is coupled with the reanalysis system [69]. These data are widely used in oceanographic and environmental applications, including studies of surface circulation, oil transport and marine debris drift, as they represent the interaction between wind and wave fields at the ocean surface.

Several validation studies have shown that ERA5 significantly improves upon its predecessor, ERA-Interim, particularly when it comes to the representation of surface winds, temperature, humidity and synoptic-scale circulation patterns. The dataset provision of ensemble-based uncertainty estimates further enhances its suitability for climate diagnostics, risk assessment and long-term environmental modeling. Despite its overall strong performance, ERA5 exhibits limitations that must be considered in applications requiring high regional specificity or the assessment of extreme events. Precipitation estimates, while improved when compared to earlier reanalyses, still show systematic biases related to convective processes, especially in the tropics and regions with complex terrain. ERA5 may also underestimate the intensity of severe winds associated with tropical cyclones and extratropical storms, partly due to the finite grid resolution and the smoothing effect of data assimilation. In coastal and mountainous regions, local-scale variability in temperature, humidity and wind fields can be inadequately captured, reflecting both resolution constraints and sparse observational coverage [67,68,69].

2.6. Tidal Forcing

Tidal currents have not been incorporated into the simulations. In the Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin, the oil wells will be located in deep offshore areas where large-scale, subinertial circulation—driven primarily by the North Brazil Current, its retroflection, ring shedding events and seasonal wind forcing—dominates surface transport. Under these conditions, barotropic tidal velocities are substantially smaller than mesoscale and wind-driven currents and contribute negligibly to basin-scale drift and beaching statistics. Furthermore, previous studies have suggested that tidal effects are most significant in nearshore areas with weaker currents and lower winds [70].

2.7. Buoy Data

STFM runs have been evaluated using surface trajectory and velocity data obtained from satellite-tracked surface drifting buoys (drifters). These data have been provided by the Global Drifter Program (GDP), an institutional ocean monitoring program maintained by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The GDP constitutes the core component of the Global Surface Drifting Buoy Array, which is part of NOAA’s Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) and operates as a scientific project under the Data Buoy Cooperation Panel (DBCP) [71].

For this study, drifters deployed between 2020 and 2024 have been selected within the spatial domain bounded by 60° W–33° W and 6° S–16° N, totaling ten drifters. This domain encompasses the entire Equatorial Margin and the adjacent open-ocean region, which is particularly relevant for assessing large-scale circulation patterns influencing oil transport. The data were obtained from the dataset entitled *Global Drifter Program—6 Hour Interpolated QC Drifter Data*, accessed directly from the ERDDAP platform.

Raw position estimates derived from Doppler measurements of Argos-tracked drifters or from GPS observations are typically irregularly distributed in time and may contain spurious positions and/or erroneous sea surface temperature values. To address these limitations and ensure data suitability for quantitative analyses, the Drifter Data Assembly Center (DAC) of the Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML) applies rigorous quality control procedures to both position and temperature records. Subsequently, the validated observations are interpolated to uniform 6 h intervals using an optimized kriging-based interpolation scheme, a technique widely adopted for two- and three-dimensional geophysical analyses [72]. The resulting interpolated dataset, together with comprehensive metadata, comprises observations from more than 30,000 drifters and spans the entire period of GDP measurements, dating back to the first deployments in 1979.

2.8. Trajectory Model Evaluation

The performance of the fate model has been evaluated using a Lagrangian framework based on the comparison between observed and simulated surface drifter trajectories. Model skill has been assessed using the normalized cumulative Lagrangian separation distance. This approach provides a non-dimensional, trajectory-based metric that is robust across dynamically distinct flow regimes, such as fast deep-ocean currents and slower continental shelf circulations [73,74].

For each observed drifter trajectory, a virtual particle was initialized at the observed drifter position and advected forward in time using the modeled surface velocity fields. At each time step i after initialization, the separation distance SDi between the modeled and observed drifter positions was computed. In parallel, the cumulative length of the observed drifter trajectory (L0i) was calculated as the along-path distance traveled by the drifter from the initialization time to time step i. Both quantities accumulate with time and therefore capture the integrated effects of trajectory divergence.

Model performance has been quantified using the normalized cumulative separation distance, NCSD, defined as the ratio between the cumulative separation distance and the cumulative observed trajectory length, summed over all time steps (Table 3):

Table 3.

Definition of the Normalized Cumulative Separation Distance (NCSD) and the associated Lagrangian skill score (SS) used for trajectory model performance evaluation. The skill score is derived from NCSD and ranges from 0 (no skill) to 1 (perfect simulation), according to the evaluation criteria adopted.

Smaller values of SS indicate lower levels of model performance, with SS = 1 corresponding to a perfect agreement between modeled and observed trajectories. In contrast to metrics based solely on endpoint separation, the cumulative formulation reduces sensitivity to short-term trajectory fluctuations and mitigates the impact of Lagrangian uncertainty associated with chaotic advection. This is particularly important for short-duration simulations relevant to oil spill response and search-and-rescue applications.

The normalized cumulative Lagrangian separation and its associated skill score offer a consistent and objective framework for evaluating trajectory models under limited observational coverage. Because the method is purely Lagrangian and relies exclusively on observed drifter trajectories, it is well suited for rapid-response scenarios and for applications spanning heterogeneous dynamical environments [73,74].

3. Results and Discussion

As described in the Section 2.8, model performance has been evaluated using the Normalized Cumulative Lagrangian Separation Distance and the Skill Score. For this analysis, ten satellite-tracked surface drifters were selected as independent observational references (Table 4). These drifters provide representative coverage of the study domain and capture both energetic and weak-flow conditions relevant to oil transport processes. Virtual particles were initialized at the observed drifter positions and advected using the modeled surface velocity fields. The resulting simulated trajectories were then compared with the corresponding observed trajectories and model performance was quantified through the normalized cumulative separation metric.

Table 4.

Skill score results for the ten satellite-tracked surface drifters used in the STFM performance evaluation. The table reports individual skill scores for 5-day, 10-day, 20-day and 30-day trajectory simulations, together with the mean and standard deviation for each simulation horizon. The results illustrate the temporal evolution of model performance, with high skill at short to intermediate time scales and increasing dispersion and uncertainty for longer periods.

The skill score results, summarized in Table 4, indicate that the trajectory model exhibits consistently high performance during the early stages of the simulations. Mean skill scores remain very high for the 5-day and 10-day integrations (0.984 and 0.953, respectively) with low standard deviations, indicating robust and stable model behavior across all selected drifters. Even at the 20-day horizon, the model maintains a relatively strong performance, with a mean skill score of 0.856, suggesting that the simulated trajectories continue to reproduce the observed drifter pathways with reasonable accuracy over intermediate time scales relevant to oil transport assessments.

After the 20-day simulation period, a degradation in model performance is observed. At 30 days, the mean skill score decreases to 0.687, accompanied by a marked increase in standard deviation. This reflects a growing dispersion among individual drifter results and highlights the increasing influence of accumulated Lagrangian uncertainty, nonlinear flow variability and potential errors in the underlying velocity fields. Such behavior is consistent with the known limits of deterministic trajectory prediction, where small discrepancies in velocity fields progressively amplify over time.

The probabilistic simulations were conducted during the period between 2018 and 2023, covering a six-year interval and recent oceanographic and meteorological variability in the region. A total of 95 drilling sites were selected within the Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin, each representing a potential source of oil release under exploration or production activities (Figure 1). For each drilling position, 500 independent oil spill simulations were performed, resulting in a comprehensive ensemble of 47,500 probabilistic trajectories (Table 2).

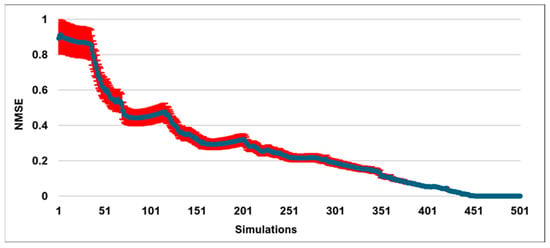

The convergence of the probabilistic runs has been evaluated through the decay of the normalized mean squared error (NMSE) computed across simulations [75]. The NMSE was calculated cumulatively as additional realizations were incorporated into the ensemble, allowing us to assess the stabilization of the probabilistic estimates as a function of sample size. Convergence was considered achieved when successive increases in the number of simulations resulted in changes below 0.01 to the NMSE. Once the NMSE threshold of <0.01 was reached, the ensemble was deemed sufficiently stable and statistically robust for subsequent analyses.

This threshold was reached at approximately the 450th run, after which additional realizations produced negligible improvements in the ensemble statistics. Therefore, the adopted ensemble size of 500 simulations provides a sufficient level of statistical stability and ensures that the probabilistic results presented in this study are robust and not sensitive to further increases in sample size (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Normalized Mean Squared Error (NMSE) as a function of the number of simulations. The progressive decrease in NMSE indicates an overall improvement in model performance as the number of simulations increases, with values gradually approaching near zero around 450 runs. The dark blue represents mean values and red envelope represents the dispersion among individual simulations, highlighting the reduction in uncertainty and variability as the system converges.

The resulting probability isolines of oil drift and beaching trajectories, computed individually for each of the 95 drilling locations, are provided in the Supplementary Material. These isolines delineate the spatial probability of oil dispersion and potential shoreline impact under different forcing conditions, allowing for an integrated regional assessment of oil drift patterns (Supplementary Material S1 (JFMA) and S2 (JASO)).

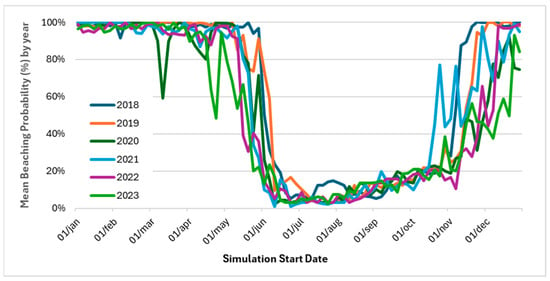

Figure 4 shows the pattern of the mean beaching probability for oil spills occurring throughout the year, computed independently for each year between 2018 and 2023. Each curve represents the average probability obtained by aggregating the 95 drilling positions. These graphs consider beaching as oil reaching any point along the coastline within a 30-day time horizon.

Figure 4.

Seasonal evolution of the mean beaching probability for oil spills between 2018 and 2023. Each line represents the average probability calculated from all 95 drilling positions within the study domain, considering beaching as oil reaching any part of the shoreline in less than 30 days after release.

The results reveal a pronounced and recurrent seasonal pattern, with consistently high beaching probabilities from January to April (JFMA), followed by an abrupt decline between late May and June. During this transition period, beaching probabilities rapidly decrease from values close to 100% to less than 10%, indicating a fundamental shift in the dominant transport mechanisms controlling oil fate. From July to October (JASO), beaching probabilities remain persistently low across all years, suggesting that environmental conditions during this period inhibit onshore transport (Figure 4).

From September onward, a gradual recovery in beaching probability is observed, with a marked increase during November and a return to high values by December. Although the overall seasonal structure is consistent among all analyzed years, interannual variability is evident, particularly during the transition periods. Differences in timing and magnitude of the decline and recovery phases reflect year-to-year variability in circulation patterns, wind regimes and mesoscale dynamics that modulate oil transport pathways.

The seasonal variability in beaching probability (Figure 4) is primarily governed by the large-scale annual migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), which modulates the regional wind regime and, consequently, the dominant transport pathways [76,77]. During periods when the ITCZ is displaced toward the Southern Hemisphere, the associated wind field becomes more persistently oriented toward the equatorial margin, enhancing onshore transport and increasing the probability of oil reaching the coast. As the ITCZ progressively migrates northward, the trade winds gradually rotate and weaken their onshore component, favoring offshore advection and reducing the beaching rates. This annual cycle of ITCZ represents a dominant large-scale atmospheric forcing that controls wind direction over the study region and, therefore, exerts a first-order influence on the observed seasonal patterns of beaching probability.

Moreover, the influence of the intensification of the North Brazil Current (NBC) and the intermittent North Equatorial Countercurrent, which occasionally penetrates southward, further modulates regional circulation, enhancing cross-shelf exchanges and reinforcing the highly dynamic and complex transport patterns that are characteristic of this sector of the tropical Atlantic [78].

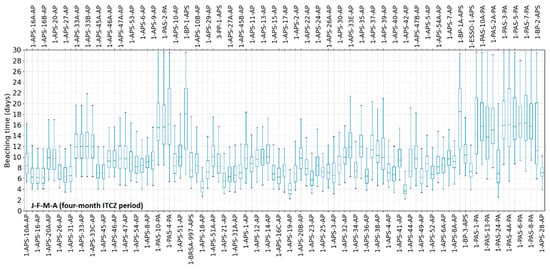

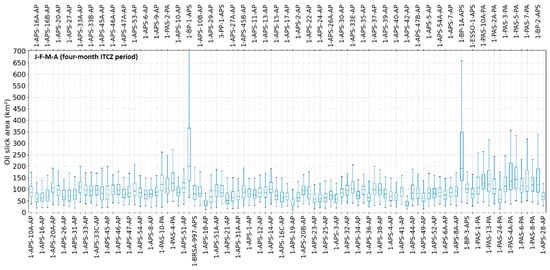

The comparison between the two boxplots highlights the strong seasonal control exerted by large-scale atmospheric forcing on oil transport and beaching dynamics in the Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin. The JFMA period, when the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) is predominantly positioned in the Southern Hemisphere, is characterized by shorter and more homogeneous beaching times across most spill locations. During this phase, the prevailing trade winds exhibit a stronger onshore component, enhancing wind-driven surface transport toward the continental margin. As a result, released oil slicks tend to reach the coast in less than two weeks (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Boxplots of beaching time (days) for all simulated release positions during the JFMA period, corresponding to the four-month interval when the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) is predominantly positioned in the Southern Hemisphere. Each boxplot represents the distribution of beaching times obtained from all probabilistic simulations initialized at each given spill location. The distribution highlights the spatial variability in coastal arrival times under ITCZ-dominated atmospheric conditions.

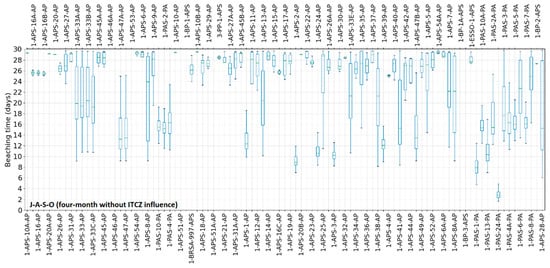

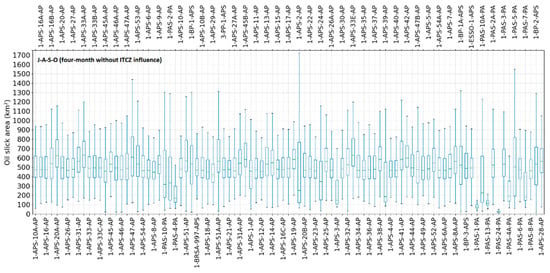

In contrast, the JASO period, corresponding to the reduction in the ITCZ influence over the study area, exhibits a completely different behavior. Median beaching times are generally longer and the distributions display a substantially larger spread, indicating increased variability and uncertainty in coastal arrival times. This reflects the gradual reorientation of the trade winds as the ITCZ migrates northward, reducing the persistence of onshore wind stress and favoring more offshore-directed transport. Under these conditions, oil trajectories become increasingly sensitive to mesoscale systems, such as eddies or shear, which contribute to the increase in beaching time to over two weeks (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Boxplots of beaching time (days) for all simulated release positions during the JASO period, corresponding to the four-month interval when the ITCZ is displaced toward the Northern Hemisphere and its direct influence over the study area is reduced. Compared with the ITCZ-influenced period, the broader spread and generally longer beaching times reflect changes in wind direction that reduce onshore transport and increase variability in coastal arrival times.

The contrast between the two periods also reveals a systematic shift in risk patterns. JFMA distributions suggest higher confidence levels from beaching forecasting and shorter available time for response teams. However, during JASO, the increased dispersion indicates that while beaching may still occur, its timing becomes less predictable and, in some cases, substantially delayed, extending toward the upper limit of the 30-day simulation window. This behavior is consistent with the reduced dominance of onshore wind-driven transport and the increased role of ocean circulation variability during the ITCZ-free period.

The boxplots are reinforced by the comparison between the JFMA and JASO oceanic drift probability maps. They highlight a clear seasonal modulation of surface transport pathways, primarily controlled by the large-scale atmospheric forcing associated with the migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) [76,77].

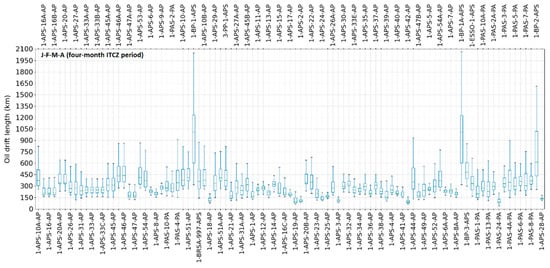

The oil drift length exhibits strong seasonal variability associated with the position of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). During JFMA, drift distances are relatively short due to the predominance of onshore-directed winds, which rapidly advect the oil slick toward the coastline (Figure 7). This early coastal interaction reduces the residence time of oil in the marine environment, limiting both advection and dispersion.

Figure 7.

Boxplots of oil drift length (km) for all simulated release positions during the JFMA period, corresponding to the four-month interval when the ITCZ is predominantly positioned in the Southern Hemisphere. Each boxplot represents the distribution of oil drift lengths obtained from all probabilistic simulations initialized at each given spill location. The distribution highlights the low length variability under ITCZ-dominated atmospheric conditions.

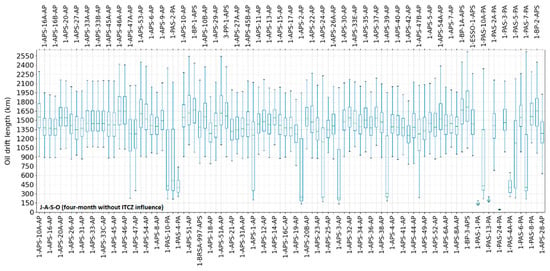

In contrast, during JASO the oil drift length increases by approximately a factor of seven. Under these conditions, the wind and current fields favor offshore transport, allowing the oil to reach the vortex of the North Brazil Current, where it becomes retained within recirculating flow patterns far from the coast.

The North Brazil Current (NBC) is a vigorous western boundary current in the tropical Atlantic that flows northwestward along the northern coast of Brazil before undergoing seasonal retroflection between approximately 4° N and 10° N, feeding into the North Equatorial Countercurrent (NECC). During this retroflection, a significant portion of the NBC’s flow separates from the coast and forms large anticyclonic mesoscale vortices—often referred to as NBC rings or eddies—characterized by warm core structures and positive sea surface height anomalies. These vortices are shed episodically and propagate northwestward along the continental slope toward the Caribbean, transporting mass away from the Brazilian coast [78]. This retention significantly prolongs the oil residence time, resulting in substantially longer drift trajectories (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Boxplots of oil drift length (km) for all simulated release positions during the JASO period, corresponding to the four-month interval when the ITCZ is displaced toward the Northern Hemisphere and its direct influence over the study area is reduced. Compared with the ITCZ-influenced period, the higher lengths reflect the broader wind-driven directions and the changes of the NBC patterns.

The seasonal contrast is also reflected in the oil slick area. During JFMA, beaching stops the spreading processes, leading to relatively compact slicks (Figure 9). During JASO, the extended residence time in open waters allows spreading mechanisms to act over longer periods, increasing the slick area by approximately six times (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Boxplots of oil slick area (km2) after 30 days for all simulated release positions during the JFMA period, corresponding to the four-month interval when the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) is predominantly positioned in the Southern Hemisphere. Each boxplot reflects the short drift time until beaching, when the spreading ends and the growth of the oil slick stops. The distribution highlights the low size variability under ITCZ-dominated conditions.

Figure 10.

Boxplots of oil slick area (km2) after 30 days for all simulated release positions during the JASO period, corresponding to the four-month interval when the ITCZ is displaced toward the Northern Hemisphere and its direct influence over the study area is reduced. Compared with the ITCZ-influenced period, the broader spread reflect changes in wind direction that reduce onshore transport and increase the oil-on-water period.

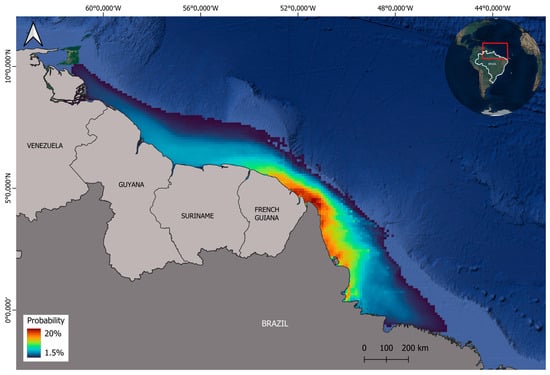

During the JFMA period, when the ITCZ is predominantly positioned over the Southern Hemisphere, the wind field is more persistently oriented toward the continental margin [76,77]. This configuration enhances onshore and along-shelf transport, resulting in a narrow and well-defined corridor of high drift probability aligned with the continental slope and Guianas–Brazil margin. The concentration of higher probabilities close to the coast indicates a more constrained and directional transport regime, favoring the accumulation of surface tracers along the margin and increasing the likelihood of coastal interaction within relatively short timescales (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Spatial distribution of oceanic drift probability during the JFMA period calculated from oil spill simulations released in Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin. Colors represent the percentage of simulations in which oil parcels traversed each grid cell within the 30-day simulation. The results reveal a dominant northwestward transport during the JFMA season, reflecting the strong influence of ITCZ-related wind forcing.

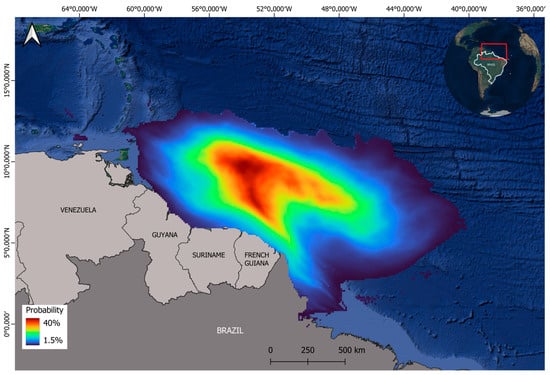

In contrast, the JASO period is characterized by the northward displacement of the ITCZ and a progressive reorientation of the trade winds, which weakens the onshore component of the wind-driven circulation. As a consequence, the drift probability pattern becomes broader and more diffuse, with a pronounced offshore expansion of the high-probability region. This reflects a transport regime dominated by enhanced lateral spreading and greater variability in surface currents, allowing oil parcels to disperse over a wider oceanic area before approaching the continental margin (Figure 12). Throughout the ITCZ, the intensity and direction of the North Brazil Current (NBC) fluctuate considerably. The recurrent formation of mesoscale eddies, such as the North Brazil Current rings and transient meanders contribute to the dispersion and deflection of surface oil slicks, reducing the persistence of coherent drift trajectories (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Spatial distribution of oceanic drift probability during the JASO period calculated from oil spill simulations released in Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin. Colors indicate the percentage of simulations in which oil parcels traversed each grid cell within the 30-day simulation. JASO pattern shows a broader offshore dispersion and reduced along-shelf transport toward the continental platform, reflecting the seasonal reorganization of surface circulation and the northward displacement of the ITCZ.

The integrated analysis of all simulations indicates that spilled oil generally remains adrift for periods exceeding seven days with predominant northwestward drift toward the Guyana–Suriname basin’s (Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana) jurisdictional waters. This transport pattern results from the combined influence of the North Brazil Current and the prevailing trade winds, which together govern the surface circulation across this portion of the tropical Atlantic. However, the overall dispersion field does not reveal any dominant pathway (more than 80%), as evidenced by the relatively low probability values in the central region of the isolines (less than 50%). This variability reflects the complex oceanographic setting of the area, where the seasonal reversal of wind regimes, the formation of North Brazil Current rings and the intermittent southward intrusion of the North Equatorial Countercurrent interact to create a highly dynamic and transient circulation system.

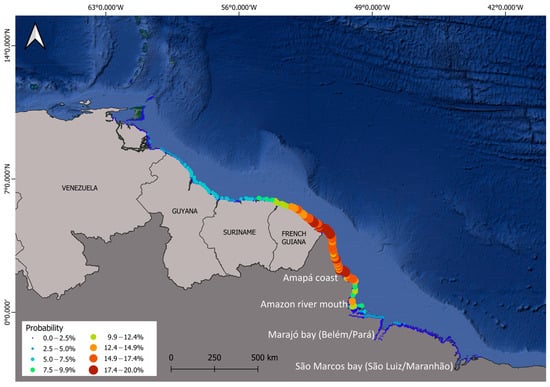

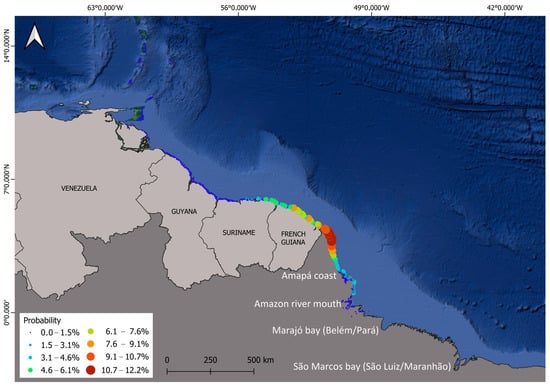

The comparison between the JFMA (Figure 13) and JASO (Figure 14) beaching probability maps reveals a strong seasonal control on both the spatial extent and intensity of coastal exposure to oil contamination along the Guianas and Brazilian equatorial coast. This contrast reflects the dominant role of large-scale atmospheric forcing, particularly the annual migration of the ITCZ, in regulating superficial wind-driven drift.

Figure 13.

Beaching probability distribution during the JFMA calculated from all 95 drilling positions. Colored segments along the coastline indicate the percentage of simulations that reached each sector. The highest probabilities are concentrated along the French Guiana and Amapa state (Brazil), reflecting enhanced onshore transport associated with ITCZ-dominated wind forcing during JFMA.

Figure 14.

Beaching probability distribution during the JASO calculated from all 95 drilling positions. Colored segments along the coastline indicate the percentage of simulations that reached each sector. The highest probabilities are still concentrated along the French Guiana and Amapa state (Brazil). However, both reached shore extension and associated probability levels decreased significantly, reflecting weaker onshore wind forcing and the northward displacement of the ITCZ during JASO.

During the JFMA period, the trade wind field exhibits a stronger onshore component that enhances beaching, resulting in a long and relatively continuous stretch of coastline affected by oil, with high impact probabilities in French Guiana and Amapá/BR. Even with lower probability, the simulations indicate that during the JFMA period, oil may penetrate into the Amazonas river mouth (12.5%), Marajó Bay and São Marcos bay (less than 5% each). Although the dominant transport pathway during JFMA is along the open continental margin, episodic circulation patterns and tidal–estuarine interactions can promote the diversion of oil toward the inner shelf and estuarine channels. The relatively low probabilities reflect the intermittent nature of these processes but their occurrence is particularly relevant from an environmental perspective given the high ecological sensitivity of the Amazonas river mouth and the Marajó Bay. These results highlight that, under favorable seasonal forcing, even regions that are not persistently exposed may still experience oil intrusion, reinforcing the need to consider low-probability, high-impact scenarios in regional oil spill risk assessments (Figure 13).

In contrast, the JASO period is marked by the northward displacement of the ITCZ and a gradual reorientation of the trade winds, which significantly weakens the onshore transport component. As a result, both the total length of coastline affected and the associated probability levels decrease substantially. The shoreline impact pattern becomes more spatially confined to French Guiana and Amapá state (Brazil), reflecting increased lateral spreading and offshore retention of oil parcels before reaching the coast. The simulations also indicate that neither Marajó Bay nor São Marcos Bay is reached by oil under the prevailing transport conditions. The absence of coastal penetration is consistent with the reduced onshore wind component associated with the northward displacement of the ITCZ during this period. Nevertheless, the probability of oil entering the Amazonas river mouth remains, even though reduced to about 2%. This residual probability suggests that, even under less favorable atmospheric forcing, localized circulation features, transient wind events or interactions between shelf currents and estuarine dynamics may still occasionally facilitate oil intrusion into the outer estuarine region. Although such occurrences are rare, their persistence highlights the strategic relevance of the Amazonas river mouth as a sensitive and dynamically complex area, emphasizing that low-probability events should not be neglected in environmental risk assessments, particularly in regions of high ecological and socio-environmental importance (Figure 14).

4. Conclusions

Brazil has been currently confronted with escalating environmental pressure regarding its coastal and offshore waters due to the growing accumulation of oil and plastic waste in the area [79] and by recurrent oil dumping caused by vessels navigating its jurisdictional waters [35]. These stressors only emphasize the urgency of establishing robust, science-based mechanisms to prevent, monitor and respond to oil pollution [80,81]. National policies, however, have advanced along two conflicting directions: while the government has invested in large-scale preparedness and response initiatives—most notably the SISMOM program [36]—it has also promoted offshore exploration in some of the country’s most sensitive and geopolitically complex regions.

The trajectory model evaluation, based on comparisons with satellite-tracked surface drifters, has demonstrated that the modeling system performs with high skill over short to intermediate time scales. Skill scores have remained very high up to 10 days and satisfactory up to 20 days, indicating strong reliability for time horizons that are particularly relevant for emergency response and contingency planning. Although performance degrades after 20 days due to the intrinsic growth of Lagrangian uncertainty, the model remains suitable for probabilistic applications, where ensemble statistics are the primary focus rather than individual trajectories.

The probabilistic simulations have revealed a clear and recurrent seasonal influence in both oil drift and beaching probability, primarily controlled by the annual migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). During the JFMA period, when the ITCZ is predominantly positioned in the Southern Hemisphere, wind forcing exhibits a stronger onshore component, enhancing coastal convergence and resulting in high beaching probabilities along an extensive stretch of the Guianas–northern Brazil coastline. Under these conditions, oil tends to reach the coast faster, reducing available response time for mitigation actions. Although the probability of oil reaching the Amazonas river mouth is relatively modest (12.5%), it remains environmentally significant given the sensitivity and global relevance of the region. Moreover, penetration into Marajó and São Marco bays is less likely (about 5% each) but should not be dismissed outright due to its potentially severe ecological consequences [82,83].

In contrast, during the JASO period, the northward displacement of the ITCZ supports offshore dispersion and increases the variability of oil trajectories. This results in substantially lower beaching probabilities, longer and more uncertain coastal arrival times as well as a marked reduction in both the spatial extent and intensity of shoreline exposure. Nevertheless, the simulations have indicated that even during JASO, low-probability but non-negligible oil intrusion into the Amazonas river mouth may still occur, underscoring the importance of accounting for rare but potentially high-impact scenarios.

The combined analysis of drift probability maps, beaching probability distributions and beaching time statistics highlights the complexity of transport processes in the Foz do Amazonas sedimentary basin, where large-scale atmospheric forcing, the North Brazil Current system, mesoscale eddies and estuarine dynamics interact to produce highly variable outcomes. Results have shown that while no single dominant drift pathway exceeds 80% of probability, the cumulative risk to sensitive coastal and estuarine environments remains significant, particularly during ITCZ-dominated seasons.

Despite the robustness of the probabilistic framework and the extensive ensemble of simulations performed, some limitations must be acknowledged. The accuracy of the oil spill trajectories is inherently constrained by the resolution and quality of the atmospheric, oceanic and wave forcing fields and by the growth of Lagrangian uncertainty regarding the simulated time, which becomes more pronounced after approximately 20 days. In addition, the simulations consider idealized release scenarios and do not explicitly resolve small-scale coastal processes, such as fine-scale estuarine circulation, river plume dynamics and nearshore wave–current interactions, which may modulate oil transport and beaching patterns. Oil weathering processes have been represented using parameterizations that capture first-order behavior but may not fully encompass the variability associated with different oil types and environmental conditions. Finally, the probabilistic results represent statistical tendencies rather than deterministic outcomes, and therefore individual realizations may deviate from the ensemble-mean behavior. These limitations, while they do not compromise the main conclusions of the study, should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results and applying them to operational decision-making or site-specific risk assessment.

The transboundary nature of the identified risks has serious geopolitical implications. A spill originating in Brazilian jurisdictional waters, but rapidly advected toward the Guyana–Suriname basin, would result in an international emergency that Brazil could not manage unilaterally, given that national environmental agencies have no operational mandate beyond domestic waters. Neighboring countries, which may lack comparable response capacity, would be disproportionately affected. Therefore, before large-scale exploration proceeds in the region, it is essential to establish formal environmental and operational cooperation agreements between Brazil and its northern neighbors. Such agreements would facilitate joint preparedness, harmonized response protocols, mutual assistance during emergencies and shared decision-making when managing cross-border impacts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jmse14010040/s1, Supplementary Material S1 (JFMA) and S2 (JASO).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C.Z.; Methodology, D.C.Z.; Software, D.C.Z. and G.L.S.; Validation, D.C.Z., C.M.G., E.F.D.V. and B.F.S.; Investigation, D.C.Z.; Data curation, G.L.S.; Writing—original draft, D.C.Z., C.M.G., E.F.D.V., B.F.S. and A.T.L.; Writing—review & editing, D.C.Z., C.M.G., E.F.D.V., B.F.S. and A.T.L.; Supervision, D.C.Z. and A.T.L.; Project administration, D.C.Z.; Funding acquisition, D.C.Z. and A.T.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was mainly supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) and Multi-user System for Detection, Forecasting, and Monitoring of Oil Spills at Sea Project (SisMOM), with institutional funding from the National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development (FNDCT) employed by the Inova Funding Authority for Studies and Projects (FINEP). The SisMOM Project has been registered under Agreement for Research, Development and Innovation number 01.22.0102.00, reference number 1576/11, executed by FINEP, FUNCATE, INPE and the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MCTI). The funders were not involved in the design of the study nor in its collection, analyses, interpretation or writing of the manuscript; nor did they play any role in the decision to publish this point of view. D.C.Z. is supported by CNPq (process 314837/2025-6).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to recognize the professional artwork done by Rafaela Cardoso Dantas as well as the English proofreading done by Marina Teixeira Rodrigues. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Duarte, H.O.B.; Mustin, K.; Costa-Campos, C.E.; Costa-Neto, S.V.; de Castro, I.J.; Cunha, H.F.A.; da Cunha, A.C.; Hilário, R.R.; Pedroso-Santos, F.; Vilhena, J.C.E.; et al. Threats of Brazil’s new oil-drilling frontier. Nat. Sustain. 2025, 8, 1105–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, P.W.M.E.S.; Gonçalves, F.D.; Beisl, C.H.; de Miranda, F.P.; de Almeida, E.F.; Cunha, E.R. Sistema de Observação Costeira e o Papel dos Sensores Remotos no Monitoramento da Costa Norte Brasileira, Amazônia. Rev. Bras. de Cartogr. 2005, 57, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares-Júnior, A.V.; Costa, J.B.S.; Hasui, Y. Evolução da Margem Atlântica Equatorial do Brasil: Três Fases Distensivas. Geociências 2008, 27, 427–437. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, J.J.P.; Zalán, P.V. Bacia da Foz do Amazonas. Bol. de Geociências da Petrobrás 2007, 15, 299–309. [Google Scholar]

- Milani, E.J.; Brandão, J.A.S.L.; Zalán, P.V.; Gamboa, L.A. Petróleo na Margem Continental Brasileira: Geologia, exploração, resultados e perspectivas. Rev. Bras. de Geofísica 2000, 18, 352–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travassos, R.D.M.; Freitas, I.D.A. Bacia do Foz do Amazonas—Sumário Geológico e Setores em Oferta; Superintendência de Avaliação Geológica e Econômica; Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás natural e Biocombustíveis: Brasília, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano, O. Managing Hydrocarbon Assets: A Comparison across the Atlantic. In The Future of Energy in the Atlantic Basin, Center for Transatlantic Relations; The Johns Hopkins University: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, C.A.; Ribeiro, H.J.P.S.; da Silva, E.B. Exploratory plays of the Foz do Amazonas Basin, NW portion, in deep and ultra-deep waters, Brazilian Equatorial Margin. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2021, 111, 103475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelegry, E.A.; Isbell, P. (Eds.) The Future of Energy in the Atlantic Basin; Center for Transatlantic Relations: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- da Fonseca Aguiar, L.; Freire, A.F.M.; Santos, L.A.; Dominguez, A.C.F.; Neves, E.H.P.; Silva, C.G.; Santos, M.A.C. Analysis of seismic attributes to recognize bottom simulating reflectors in the Foz do Amazonas basin, Northern Brazil. Braz. J. Geophys. 2019, 37, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, A.B.; Rodger, M.; Peirce, C.; Greenroyd, C.J.; Hobbs, R.W. Seismic structure, gravity anomalies, and flexure of the Amazon continental margin, NE Brazil. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2009, 114, 006259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, N.M.; Luczynski, E. Geophysical characterization of unconventional reservoirs: New limits for the exploration and production in Brazil. In Proceedings of the XVI International Congress of the Brazilian Geophysical Society, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 19–22 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A.S.C.; Soares, F.L.M.; Pimentel, F.P.; Garção, H.F.; Mariano, L.S.A.; Cabral, M.M. Modelagem Hidrodinâmica e Dispersão de Óleo. Bacia do Foz do Amazonas; Relatório Técnico; Prooceano: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mello, M.R.; Gaglianone, P.C.; Brassell, S.C.; Maxwell, J.R. Geochemical and biological marker assessment of depositional environments using Brazilian offshore oils. Mar. Pet. Geol. 1988, 5, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, M.R.; Mosmann, R.; Silva, S.R.P.; Maciel, R.R.; Miranda, F.P. Foz do Amazonas área: The last frontier for Elephant hydrocarbon accumulations in the South Atlantic realm. AAPG Bull. 1999, 83, 403–414. [Google Scholar]

- Viscidi, L.; Phillips, S. Energy and Mining in the Amazon; The Dialogue—Leadership for the Americas; Inter-American Dialogue: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Chapter 2; pp. 15–21. Available online: https://thedialogue.org/analysis/energy-and-mining-in-the-amazon (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Alleyne, K.; Layne, L.; Soroush, M. Liza Field Development—The Guyanese Perspective. Presented at the SPE Trinidad and Tobago Section Energy Resources Conference, Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, 25–26 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M. Oil from the Amazon? Proposal to drill at river’s mouth worries researchers. Nature 2023, 619, 680–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazilian Institute of the Environment and of Renewable Natural Resources. Licença Ambiental Para a Atividade de Perfuração Marítima nos Blocos FZA-M-57, 86, 88, 125 e 127 na Bacia da Foz do Amazonas; in Despacho n°3912994/2018-GABIN; Ministério do Meio Ambiente: Brasília, Brazil, 2018. (In Portuguese). Available online: http://www.ibama.gov.br/phocadownload/notas/2018/SEI_IBAMA%20-%203912994%20-%20Despacho.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Kiran, R.; Teodoriu, C.; Dadmohammadi, Y.; Nygaard, R.; Wood, D.; Mokhtari, M.; Salehi, S. Identification and evaluation of well integrity and causes of failure of well integrity barriers (A review). J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2017, 45, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelos, A.; Awad, S.P.; Assunção, R.B. Deepwater Activities Offshore Brazil: Evolution on Drilling Technology. Presented at the University of Tulsa Centennial Petroleum Engineering Symposium, Tulsa, OK, USA, 29–31 August 1994; Society of Petroleum Engineers: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, J.; Abbassi, R.; Garaniya, V.; Khan, F. Risk analysis of deepwater drilling operations using Bayesian network. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2015, 38, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundação BIO-RIO. Avaliação e Ações Prioritárias Para a Conservação da Biodiversidade Das Zonas Costeiras e Marinhas; MMA/SBF: Brasília, Brazil, 2002; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Moura, R.L.; Martins Rodrigues, M.C.; Francini-Filho, R.B.; Sazima, I. Unexpected richness of reef corals near the southern Amazon river mouth. Coral Reefs 1994, 18, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, R.L.; Amado-Filho, G.M.; Moraes, F.C.; Brasileiro, P.S.; Salomon, P.S.; Mahiques, M.M.; Bastos, A.C.; Almeida, M.G.; Silva, J.M.; Araujo, B.F.; et al. An extensive reef system at the Amazon river mouth. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1501252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, L.A. Patterns of distribution and processes of speciation in Brazilian reef fishes. J. Biogeogr. 2003, 30, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floeter, S.R.; Rocha, L.A.; Robertson, D.R.; Joyeux, J.C.; Smith-Vaniz, W.F.; Wirtz, P.; Edwards, A.J.; Barreiros, J.P.; Ferreira, C.E.L.; Gasparini, J.L.; et al. Atlantic Reef fifish biogeography and evolution. J. Biogeogr. 2008, 35, 22–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres Neto, A.; Falcão, L.C.; Amaral, P.J.T. Caracterização de ecofácies na margem continental norte brasileira: Estado do conhecimento. Rev. Bras. Geof 2009, 27, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Francini-Filho, R.B.; Asp, N.E.; Siegle, E.; Hocevar, J.; Lowyck, K.; D’AVila, N.; Vasconcelos, A.A.; Baitelo, R.; Rezende, C.E.; Omachi, C.Y.; et al. Perspectives on the great Amazon reef: Extension, biodiversity, and threats. Front. Mar. Sci 2018, 5, 00142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marceniuk, A.P.; Rotundo, M.M.; Caires, R.A.; Cordeiro, A.P.B.; Wosiacki, W.B.; Oliveira, C.; de Souza-Serra, R.R.M.; Romão-Júnior, J.G.; dos Santos, W.C.R.; Reis, T.D.S.; et al. The bony fifishes (Teleostei) caught by industrial trawlers off the Brazilian north coast, with insights into its conservation. Neotrop. Ichthyol. 2019, 17, e180038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza Filho, P.W.M.; da Costa Prost, M.T.R.; de Miranda, F.P.; Sales, M.E.C.; Borges, H.V.; da Costa, F.R.; de Almeida, E.F.; da Rocha Nascimento Junior, W. Environmental Sensitivity Index (ESI) mapping of oil spill in the Amazon coastal zone: The Piatam Mar project. Rev. Bras. de Geofísica 2009, 27. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/j/rbg/a/wZWj8qFKv5XKTstGycL9ZwH (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Zacharias, D.C.; Gama, C.M.; Fornaro, A. Mysterious oil spill on Brazilian coast: Analysis and estimates. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 165, 112125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, D.C.; Gama, C.M.; Harari, J.; Rocha, R.P.; Fornaro, A. Mysterious oil spill on the Brazilian coast—Part 2: A probabilistic approach to fill gaps of uncertainties. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 173, 113085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, A.; Andrade, L.; Franklin, L.; Bezerra, D.; Ghisolfi, R.; Maita, R.; Nobre, P. Ship route oil spill modeling: A case study of the Northeast Brazil event, 2019. Appl. Sci 2024, 14, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, D.C.; Crespo, N.M.; da Silva, N.P.; da Rocha, R.P.; Gama, C.M.; e Silva, S.B.R.; Harari, J. Oil reaching the coast: Is Brazil on the route of international oceanic dumping? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 196, 115624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacharias, D.C.; Lemos, A.T. Early Perspectives on the Planned Brazilian Program to Address Ship-Sourced Pollution. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, D.C.; Fornaro, A. Brazilian offshore oil exploration areas: An overview of hydrocarbon pollution. Rev. Ambiente Agua 2020, 15, e2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, D.C.; Lemos, A.T.; Keramea, P.; Dantas, R.C.; da Rocha, R.P.; Crespo, N.M.; Sylaios, G.; Jovane, L.; Santos, I.G.D.S.; Montone, R.C.; et al. Offshore oil spills in Brazil: An extensive review and further development. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 205, 116663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, D.C. Desenvolvimento do STFM (Spill, Transport and Fate Model): Modelo Computacional Lagrangeano de Transporte e Degradação de Manchas de óleo. Ph.D. Thesis, Instituto de Astronomia, Geofísica e Ciências Atmosféricas, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil, 2017. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

- Zacharias, D.C.; Rezende, K.F.O.; Fornaro, A. Offshore petroleum pollution compared numerically via algorithm tests and computation solutions. Ocean Eng. 2018, 151, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, D.C.; Fornaro, A. Spill, transport and fate model (STFM): Development and validation. Rev. Ambiente Agua 2022, 17, e2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, D.C.; Gama, C.M.; Fornaro, A. Desenvolvimento e Validação do STFM: Um Novo Modelo de Derramamento de Óleo para a Costa Brasileira. In Proceedings of the Anais do 3º Simpósio Interdisciplinar de Ciência Ambiental, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil, 25–27 October 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessarolo, L.d.F.; Barreto, F.T.C.; Innocentini, V.; Gonçalves, I.Â.; Silva, L.H.M.M.; Chacaltana, J.T.A.; Palma, G.; Martins, R.G. A surface Lagrangian algorithm applied to the 2019 South Atlantic oil spill. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 268, 113505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, F.T.; Dammann, D.O.; Tessarolo, L.F.; Skancke, J.; Keghouche, I.; Innocentini, V.; Winther-Kaland, N.; Marton, L. Comparison of the coupled model for oil spill prediction (CMOP) and the oil spill contingency and response model (OSCAR) during the DeepSpill field experiment. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 204, 105552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenke, B.; O’Connor, C.; Barker, C.; Beegle-Krause, C.J.; Eclipse, L.E. (Eds.) General NOAA Operational Modeling Environment (GNOME) Technical Documentation; US Department of Commerce; NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS OR&R 40; Emergency Response Division: Seattle, WA, USA, 2012; p. 105. [Google Scholar]

- MacFadyen, A.; Barker, C.H. NOAA’s Response Modeling—Challenges and Innovations. Int. Oil Spill Conf. Proc. 2024, 1405, 318. [Google Scholar]

- Dagestad, K.-F.; Röhrs, J.; Breivik, Ø.; Ådlandsvik, B. OpenDrift v1.0: A generic framework for trajectory modelling. Geosci. Model Dev. 2018, 11, 1405–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, F.F.D.B.; de Freitas, P.P.; e Silva, W.K.L.; Guerrero-Martin, C.A.; Gomes, V.J.C.; Siegle, E. Assessing the risk of coastal oil strandings in the Brazilian equatorial margin: A numerical modeling approach. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2026, 223, 119020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallcraft, A.J.; Metzger, E.J.; Carroll, S.N. Software Design Description for the HYbrid Coordinate Ocean Model (HYCOM); Version 2.2; NRL/MR/7320--09-9166; Naval Research Laboratory, Stennis Space Center: Hancock, MS, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Skamarock, W.C.; Klemp, J.B.; Dudhia, J.; Gill, D.O.; Liu, Z.; Berner, J.; Wang, W.; Powers, J.G.; Duda, M.G.; Barker, D.M.; et al. A Description of the Advanced Research WRF; Version 4; NCAR Tech. Note NCAR/TN-556+STR; National Center for Atmospheric Research: Boulder, CO, USA, 2019; p. 145. [Google Scholar]

- Breivik, Ø.; Janssen, P.A.; Bidlot, J.R. Approximate Stokes drift profiles in deep water. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2014, 44, 2433–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breivik, Ø.; Christensen, K.H. A Combined Stokes Drift Profile under Swell and Wind Sea. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2020, 50, 2819–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiver, W.; Mackay, D. Evaporation rate of spills of hydrocarbons and petroleum mixtures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1984, 18, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapa, P.D. Modeling oil spills to mitigate coastal pollution. In Handbook of Environmental Fluid Dynamics; Two Taylor Francis Group; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Spaulding, M.L. State of the art review and future directions in oil spill modeling. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 115, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingas, M. Oil Spill Science and Technology, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]