Abstract

Ocean internal waves occur in stably stratified seawater and play a crucial role in energy cascade, material transport, and military activities. However, the complex and irregular spatial patterns of internal waves pose significant challenges for accurate detection in SAR images when using conventional convolutional neural networks, which often lack adaptability to geometric variations. To address this problem, this paper proposes a refined Faster R-CNN detection framework, termed “rFaster R-CNN”, and adopts a transfer learning strategy to enhance model generalization and robustness. In the feature extraction stage, a backbone network called “ResNet50_CDCN” that integrates the CBAM attention mechanism and DCNv2 deformable convolution is constructed to enhance the feature expression ability of key regions in the images. Experimental results show that in the internal wave dataset constructed in this paper, this network improves the detection accuracy by approximately 3% compared to the original ResNet50 network. At the region proposal stage, this paper further adds two small-scale anchors and combines the ROI Align and FPN modules, effectively enhancing the spatial hierarchical information and semantic expression ability of ocean internal waves. compared with classical object detection algorithms such as SSD, YOLO, and RetinaNet, the proposed “rFaster R-CNN” achieves superior detection performance, showing significant improvements in both accuracy and robustness.

1. Introduction

Internal waves occur in the ocean interior, with frequencies between the buoyancy and inertial frequencies [1]. They play essential roles in energy transport and nutrient mixing, maintaining ecological balance [2], and influence underwater navigation and acoustic propagation, posing safety risks for offshore operations and submarines [3]. Therefore, real-time detection and monitoring of internal waves are critical for military operations, resource exploration, and other strategic activities.

In recent decades, satellite remote sensing has become an essential tool for studying internal waves due to its cost-effectiveness and wide spatial coverage [4] compared with traditional in situ measurements which are costly and spatially limited [5]. Observations can be made via different remote sensing methods, including synthetic aperture radar (SAR), visible light, and infrared, with SAR offering distinct advantages such as all-weather, all-day operation and high spatial resolution, making it particularly suitable for detecting internal waves under cloudy or foggy conditions. In SAR images, internal waves typically appear as alternating bright and dark stripes [6], which form the basis for detection. Early computational methods, such as gradient-based 2D wavelet analysis [7] and two-dimensional empirical mode decomposition [8], improved detection but remained sensitive to noise and relied on handcrafted texture features. Due to the variability of internal wave patterns across marine environments, fixed features are insufficient to capture diverse morphologies, resulting in poor robustness and limited generalization. These challenges motivate the recent adoption of deep learning techniques for automated internal wave detection in SAR imagery.

In recent years, the rapid development of artificial intelligence, particularly deep learning, has provided new methodologies for internal wave detection. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have demonstrated remarkable performance in image processing. Zhang et al. [9]. proposed the R-CNN (Regions with Convolutional Neural Networks) algorithm, which improved mean Average Precision (mAP) by ~30% over previous methods but required high memory and generated many redundant region proposals, slowing training. To address these issues, Fast R-CNN [10] computed feature maps once per image, improving efficiency, though region proposal generation still took 2–3 s. Faster R-CNN [11] further resolved this by integrating a Region Proposal Network (RPN) into the architecture, enabling end-to-end training and unified object detection.

Despite the success of deep learning in object detection, its application in ocean remote sensing has primarily focused on ship detection and military target recognition [12,13], while research on internal wave detection in SAR images remains limited. Bao et al. [14] applied the Faster R-CNN framework with the ZF-Net model to train on internal wave images and construct an internal wave detection network, demonstrating the feasibility of deep learning for this task. Sun et al. [15] employed the Faster R-CNN to detect internal waves in multi-source SAR images. More recently, Ma et al. [16] proposed a detection network based on the Swin Transformer architecture that integrates multi-scale hierarchical features, achieving improved performance in internal wave detection tasks.

However, these studies mainly adopted existing deep learning architectures without considering task-oriented optimizations. For instance, the suitability of convolutional kernel shapes or anchor box sizes for representing internal wave structures has not been examined. Such limitations may restrict the models’ ability to effectively capture the distinctive spatial patterns and morphological characteristics of internal waves in SAR imagery.

To address these challenges, this study constructs a SAR image dataset specifically designed for internal wave detection and proposes a Refined Faster R-CNN framework optimized through transfer learning. The architecture is improved in both feature extraction and region proposal modules to enhance the model’s adaptability to the complex and irregular spatial structures of internal waves. Furthermore, attention and deformable convolution mechanisms are integrated to strengthen feature representation, while multi-scale and spatial alignment strategies are introduced to improve detection precision. Finally, the proposed model is evaluated against several classical object detection algorithms, and conclusions are made.

2. Model Architecture and Improvements

2.1. Framework of the Original Faster R-CNN Model

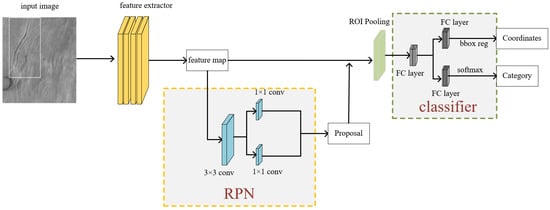

The Faster R-CNN architecture consists of four main components: a feature extractor, an RPN, an ROI Pooling layer, and a classifier, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The original Faster R-CNN architecture.

The input SAR image of internal waves is first processed by the feature extraction module to capture key features and generate corresponding feature maps. These feature maps are then fed into the Region Proposal Network (RPN), which distinguishes positive and negative samples based on the Intersection over Union (IoU) criterion [17] and performs bounding box regression to generate candidate proposal regions. Finally, the proposals and feature maps are passed to the detection head, where classification and localization are jointly performed to produce the final detection results.

2.2. Feature Extraction Network

For the task of internal wave detection in SAR images, challenges arise due to the stripe-like appearance of internal waves, low image contrast, and strong noise interference. Traditional feature extraction networks often struggle to capture effective features under such complex oceanic backgrounds. To enhance the model’s ability to perceive the stripe patterns of internal waves, this study improves upon the widely adopted convolutional neural network ResNet50 [18] and proposes a more suitable feature extraction backbone named “ResNet50_CDCN”.

The architectural cornerstone of the ResNet framework resides in its residual block design, which incorporates identity shortcut connections to enable residual learning. This structure effectively mitigates the problem of vanishing gradient in deep neural networks, allowing the network to be trained deeper and more stably. As a result, ResNet has demonstrated outstanding performance across various computer vision tasks. The general form of a residual block can be expressed as:

In this context, represents the residual function to be learned, where and are the input and output vectors, respectively. The key idea here is to add the input directly to the output of the convolutional layers. In simple terms, each iteration adds the result from the previous iteration, ensuring that the new output does not deviate significantly from the previous one.

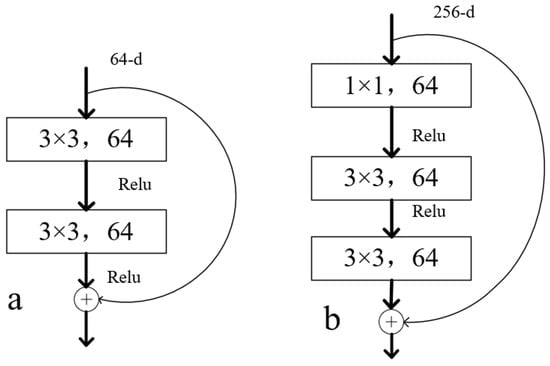

In the original ResNet, the residual block structures can be categorized into two types: basicblock and bottleneckblock, as illustrated in Figure 2. The basicblock is commonly used in shallower networks such as ResNet18 and ResNet34. It features a simple architecture consisting of two consecutive 3 × 3 convolutional layers. In contrast, the bottleneckblock is typically employed in deeper networks such as ResNet50 and ResNet101. It adopts a “compression-expansion” structure composed of a stack of three convolutional layers: 1 × 1, 3 × 3, and 1 × 1. This design reduces computational cost while allowing the network to go deeper, thereby improving feature representation capabilities.

Figure 2.

The residual block structures in ResNet: Basicblock (a) and bottleneckblock (b).

2.2.1. Deformable Convolution Network (DCN)

Traditional convolution typically adopts a fixed sampling grid, which tends to struggle with capturing key local structural information when applied to internal wave stripes in complex oceanic backgrounds. In the context of neural network learning, internal waves can be regarded as non-rigid targets. To enhance the network’s ability to model such non-rigid structures, this study introduces a deformable convolution module into the residual block.

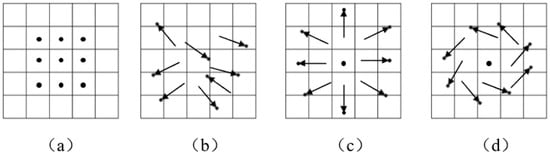

The concept of deformable convolution was first proposed in 2017 [19], aiming to improve the convolutional neural network’s adaptability to geometric transformations of objects. Unlike standard convolution that samples feature from fixed spatial positions, deformable convolution introduces learnable offsets on top of the standard sampling grid. These offsets allow the sampling locations of the convolutional kernel to be dynamically adjusted based on the input features, thereby enabling the network to more effectively capture local structure variations and deformation patterns in the image, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Illustration of sampling patterns in convolution operations: (a) Conventional 3 × 3 times 3 × 3 convolution with fixed sampling locations. (b) Deformable convolution with learnable offsets. (c,d) Two examples of variant deformable sampling patterns.

The standard convolution operation can be mathematically expressed as:

In this context, represents a specific location on the output feature map, denotes an arbitrary position within the region, and is the center position. is the weight of the convolution kernel, while and represent the input and output, respectively.

In deformable convolution, the positions of the convolution kernel are no longer fixed. Instead, an offset is added, resulting in the following deformable convolution formula:

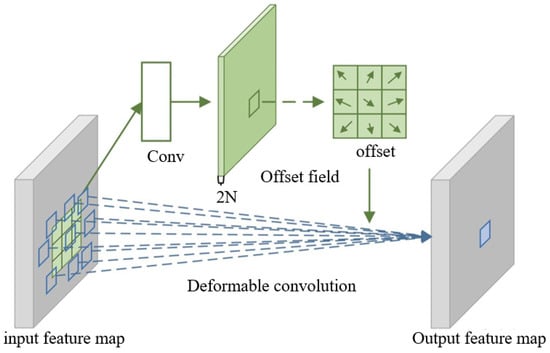

As shown in Figure 4, DCN exhibits strong geometric adaptability, enabling the extraction of more informative features relevant to the target objects. However, the features extracted by deformable convolutions may still be affected by irrelevant content in the image, which can degrade their representational effectiveness. For example, marine oil spills are one of the common sources of interference. The oil film formed on the sea surface suppresses the generation of short gravity-capillary waves, resulting in low backscatter regions in SAR images. These dark patches resemble the low-backscatter bands caused by internal wave troughs, potentially leading to false alarms. In addition, ship wakes—including turbulent wakes and Kelvin waves generated during navigation—can produce regular or irregular linear features in SAR imagery that significantly overlap with the characteristics of internal waves. This interference is especially pronounced when the direction of the ship’s track aligns with the propagation direction of the internal waves, thereby increasing the likelihood of confusion.

Figure 4.

The framework of Deformable Convolution Network (DCN).

To address this limitation, DCNv2 was proposed as an improvement over the original DCN. By enhancing geometric modeling capabilities and increasing training robustness, DCNv2 allows for more accurate feature extraction of the target structures. This leads to improved overall performance in detection and recognition tasks.

The convolution formula of DCNv2 is shown as:

where represents the feature of the pixel point on the input feature map; represents the feature of the pixel point on the output feature map; is the learned weight; is the pre-specified offset; is the learnable offset for pixel point ; and is the modulation weight for pixel point , with values in the range of [0, 1].

2.2.2. Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM)

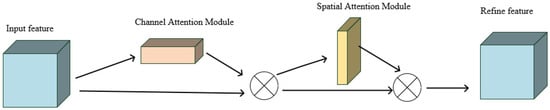

Traditional convolutional networks are limited in their ability to effectively distinguish the importance of features, which can restrict their performance when dealing with complex image tasks. To overcome this limitation, this study integrates the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) [20] into the network. The structure of CBAM is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The structure of the Convolutional Block Attention Module.

In this module, the input feature map first passes through a Channel Attention Module, which adaptively adjusts the feature response weights based on the importance of each channel, thereby enhancing the representation of critical channel information. Subsequently, a Spatial Attention Module is applied to focus on key spatial regions within the feature map, improving the model’s attention to salient object locations.

Through the combined effect of this dual attention mechanism, the module effectively suppresses irrelevant noise and emphasizes important features, thereby correcting prediction errors and enhancing both estimation accuracy and detection performance.

2.2.3. CDCN Attention Block

In the original ResNet50 network, all 3 × 3 convolutional kernels operate with fixed sampling positions and shapes, making it difficult to adapt the receptive field to the complex and variable patterns of ocean internal waves in input SAR images. This limitation hampers the network’s ability to effectively extract features from such intricate structures.

To address the limitations of conventional convolution in capturing the complex and irregular structures of internal waves, this study incorporates the DCNv2 module into residual blocks, thereby enhancing the network’s ability to adaptively model local geometric deformations. At the same time, the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) is integrated to strengthen the network’s focus on key internal wave features, suppress irrelevant background information, and improve the accuracy and efficiency of feature extraction. Building upon these enhancements, we design a novel backbone module, termed “CDCN”, which synergistically combines CBAM and DCNv2. By integrating geometric adaptability with attention-driven feature refinement, CDCN provides a more robust and discriminative representation of internal waves in SAR imagery. Based on this, an improved residual module named “Bottleneck_CDCN” is designed, as illustrated in Table 1, which integrates both DCNv2 and the attention mechanism. This design significantly enhances the network’s representational ability for the complex morphology of ocean internal waves.

Table 1.

Different layers in the improved residual module “Bottleneck_CDCN”.

In the table, the main process of the “Bottleneck_CDCN” is as follow: The input features first undergo a 1 × 1 convolution for channel compression. This is followed by batch normalization (bn) [21] and the ReLU [22] activation function, which standardize and non-linearly map the features. Next, the introduced 3 × 3 deformable convolution (DCNv2) is used to flexibly extract spatial features, and combined with BN and ReLU to further enhance the feature expression ability. Then, the features undergo another 1 × 1 convolution for channel expansion (to four times the original number of channels) and normalization. Finally, the output features pass through the channel and spatial attention mechanisms in the CBAM module to enhance the model’s ability to focus on both the channel and spatial dimensions.

2.2.4. The “ResNet50_CDCN”

ResNet50 is one of the mainstream convolutional neural networks, effectively addressing issues such as vanishing and exploding gradients through its residual structure. Although ResNet50 has demonstrated excellent performance in many visual tasks, its fixed hierarchical architecture and convolutional kernels may limit its generalization capability and feature representation in complex tasks. To further enhance the performance of the ResNet50 network, this study replaces the deeper modules of ResNet50 with the proposed “Bottleneck_CDCN”, thereby enhancing the network’s ability to extract complex features and forming a new backbone network named “ResNet50_CDCN’’.

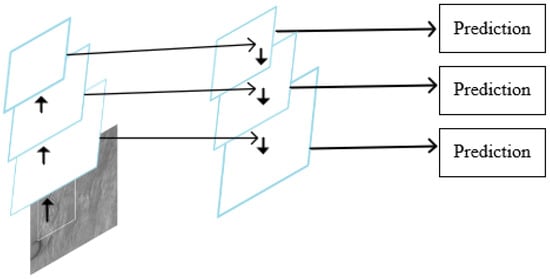

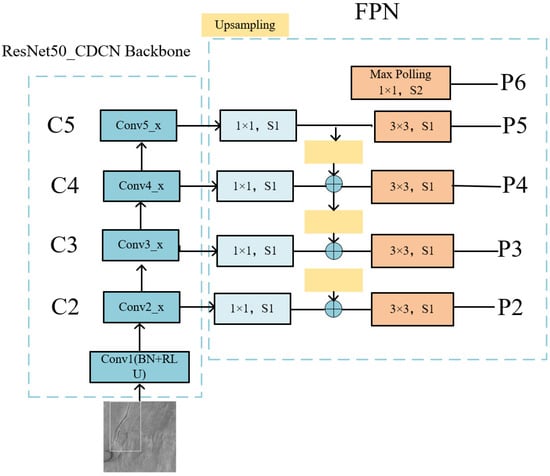

2.3. Feature Pyramid Network (FPN)

Convolutional neural networks typically utilize the feature maps from the final layer as inputs for subsequent components. Since deeper feature maps contain more abstract semantic information, they are beneficial for object recognition and classification tasks. Moreover, this approach reduces computational costs and enhances detection speed. However, when addressing multi-scale variations, most networks rely on a single high-level feature map for downsampling, which can lead to the loss of small objects containing limited feature information. To overcome this problem, Lin et al. [23] proposed the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN), a structure designed to fuse multi-scale features effectively. The architecture of the FPN is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the FPN (Feature Pyramid Network).

It constructs feature maps at various scales that contain high-level semantics, with only a small increase in computational cost. The FPN feature pyramid combines features from both similar and different feature maps and performs predictions based on this combined information.

As shown in Figure 7, this paper uses ResNet50_CDCN as the feature extraction network and adds the FPN ahead of the original RPN structure. This design enhances the quality of the extracted features and produces more representative outputs, which are better suited for subsequent detection tasks.

Figure 7.

The framework of Feature Extraction Network.

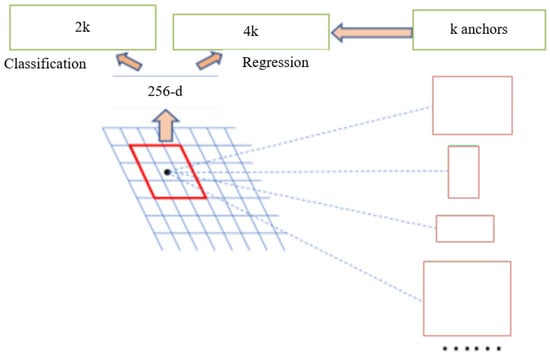

2.4. Improvement of the RPN

Faster R-CNN directly uses the Region Proposal Network (RPN) to generate object proposals. The main process is as follows: each feature point is first mapped back to the center of its receptive field in the original image, serving as a reference point. Then, K anchors of different scales and aspect ratios are placed around this point. A 1 × 1 convolution is used on the low-dimensional feature map. It outputs 2K classification scores (foreground or background) and 4K bounding box regression offsets at each reference point, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Architecture of the Region Proposal Network (RPN).

The original Faster R-CNN adopts 9 anchor boxes, corresponding to 3 scales (1282, 2562, 5122) and 3 aspect ratios (1:1, 1:2, and 2:1). However, the internal wave data in the marine dataset exhibit significant scale variation and contain multi-scale information. To improve the detection accuracy of small targets, two additional smaller scales are introduced, modifying the anchor box sizes to (322, 642, 1282, 2562, 5122), resulting in a total of 15 anchor configurations.

2.5. Improvement of the RoI Pooling

In two-stage object detection methods, Faster R-CNN serves as a typical representative. Its detection process consists of two stages: the first stage generates candidate regions (i.e., proposals or anchors) via the Region Proposal Network (RPN); the second stage performs classification and bounding box regression on these candidate regions.

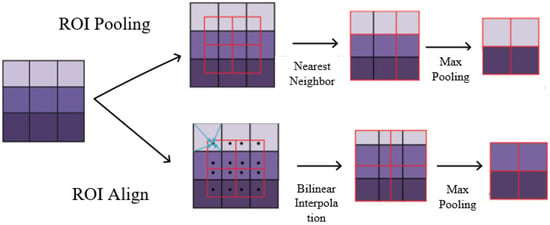

In this process, ROI Pooling is a critical step. Its main function is to map candidate regions of varying sizes into fixed-size feature maps to enable unified processing by subsequent classification and localization branches. However, since the coordinates of candidate boxes are typically floating-point numbers, ROI Pooling performs nearest-neighbor interpolation and quantization of coordinates during mapping, which can introduce quantization errors.

For high-resolution SAR images, which often contain strong noise interference, and targets such as internal waves with subtle edge features, significant quantization errors during ROI Pooling may cause the loss or weakening of important structural information. This, in turn, adversely affects the model’s accuracy in recognizing internal waves.

To address this limitation, this study adopts the ROI Align [24] method. Unlike ROI Pooling, ROI Align avoids quantizing floating-point coordinates and instead utilizes bilinear interpolation to precisely extract feature values from the feature map. This technique preserves spatial information more effectively and enhances the model’s sensitivity to small objects and fine-grained structures. Therefore, it is particularly suitable for detecting internal waves, which are characterized by delicate edge features and are easily affected by environmental disturbances.

Figure 9 illustrates the differences between ROI Pooling and ROI Align. The upper panel presents the traditional ROI Pooling process, where regions are divided after coordinate quantization followed by max pooling, which may lead to feature misalignment. In contrast, the lower panel shows ROI Align, which preserves floating-point coordinate precision and applies bilinear interpolation to extract features more accurately within candidate regions, thereby enhancing overall detection performance.

Figure 9.

Pooling Process of RoI Align and RoI Pooling.

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Dataset

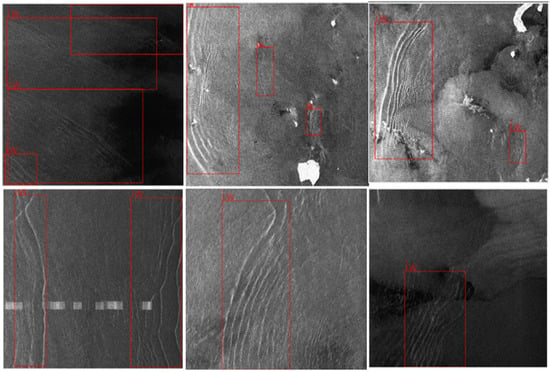

The quality of the training dataset is a key factor influencing the accuracy of deep learning-based object detection models [25,26]. In this study, we utilize the publicly available ocean internal wave dataset, namely the S1-IW-2023 Dataset [27] (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11090328, accessed on 30 April 2024)), as the primary source of SAR imagery for model training and evaluation, which contains 742 SAR images of internal waves and their corresponding annotation files collected from June 2014 to February 2023. All images in the dataset are sourced from the Sentinel-1 satellite. Additionally, this study has gathered supplementary SAR images containing internal wave information captured by the Sentinel-1 satellite over the South China Sea and the Andaman Sea regions. Through manual annotation and image preprocessing, a supplementary dataset comprising 1133 SAR images was constructed. The dataset was split into training and validation sets with an 8:2 ratio. Some typical training samples of SAR images are shown in Figure 10 (the red bounding boxes are the marked internal wave region).

Figure 10.

Six examples of the training dataset, the red bounding boxes are the marked internal wave region, “iw” denotes the internal wave.

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

The evaluation metrics used in this study include Precision, Recall, and mean Average Precision (). Among these, is the most commonly used metric in object detection tasks, as it reflects the overall detection performance across all categories in the dataset. Specifically, represents the mean of the Average Precision () values computed for each class.

is calculated as the area under the Precision-Recall () curve, where Precision () is plotted on the vertical axis and Recall () on the horizontal axis. The formula is as follows:

In this context, refers to the true positive samples predicted as positive by the model, refers to the false positive samples predicted as positive, and refers to the false negative samples predicted as negative. The Average Precision () for each class is computed based on the area under the Precision-Recall () curve (). The mean Average Precision () is then obtained by averaging the AP values across all classes. The formula for is as follows:

3.3. Experimental Environment and Parameters

The deep learning models in this study were developed on a Windows 11 using the PyTorch 2.0.1 deep learning framework and programmed in Python 3.9. The hardware environment consists of an Intel Core i9-13980HX processor and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080 GPU with 12GB of video memory.

The parameter configuration of the CNN model plays a crucial role in the training performance. In this study, the batch size was set to 4, and the number of training epochs was set to 50 to ensure sufficient convergence of the model. The Adam [28] optimizer was chosen to accelerate the convergence speed during training.

Transfer learning refers to the method of transferring knowledge structures from a related source domain to a target domain [29]. To improve training efficiency and the initial performance of the model, a ResNet50 network pretrained on the ImageNet dataset (https://www.image-net.org) was employed as the base feature extractor. Utilizing a pretrained model significantly enhances convergence speed and reduces overall training time, especially in small-sample tasks [30,31]. To prevent excessive perturbation of the pretrained weights—which could lead to the loss of the generalization ability learned from large-scale datasets—the initial learning rate was set to 0.0065, balancing fine-tuning stability and effectiveness.

3.4. Ablation Experiment of CDCN

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed improvements, an experiment was conducted during the stage of feature extraction of Faster R-CNN. The original ResNet50 was used as the baseline model, and an ablation study was performed on ResNet50_CDCN. The experimental results are shown in Table 2, where “√” indicates that the module was included, and “×” indicates that the module was not included. The results compare the overall performance of the model with and without the introduction of different modules.

Table 2.

Results of the ablation experiments for DCNv2 and CBAM.

The ablation study results show that the standard ResNet50 provides a strong baseline performance for object detection.

After introducing the attention mechanism, the model exhibits a slight improvement in precision, particularly under the relatively lenient evaluation criterion of IoU = 0.5. However, at higher IoU thresholds, the performance gain becomes marginal, and the improvement in Average Recall (AR) remains limited. This suggests that while the attention mechanism can enhance feature discrimination, its contribution to precise localization is relatively modest when applied alone.

Similarly, after introducing the DCNv2 module, the model demonstrates a comparable slight performance improvement, mainly reflected in enhanced precision at lower IoU thresholds. This indicates that deformable convolution is effective in modeling local geometric variations, but its standalone impact on overall detection performance is still constrained.

In contrast, when the CDCN module is introduced, the model achieves consistent and noticeable improvements across all evaluation metrics. This demonstrates that the CDCN module plays a positive role in optimizing the feature extraction process and enhancing the representation of critical regions, thereby effectively improving overall detection performance.

Notably, the ablation study reveals that although incorporating CBAM or DCNv2 individually leads to only marginal performance gains, their combination results in a significant improvement. This can be attributed to the complementary nature of the two modules. Specifically, CBAM enhances feature representation through channel and spatial attention, providing semantic guidance, while DCNv2 improves local geometric modeling via adaptive sampling. When integrated into the unified CDCN module, CBAM guides the deformable sampling process of DCNv2, and DCNv2, in turn, enriches CBAM with spatial flexibility. This synergistic interaction enables a better balance between feature refinement and localization accuracy, ultimately leading to superior detection performance.

3.5. Comparison Experiment of the Combinations of ROI Align and FPN

To verify the performance improvement achieved by introducing the ROI Align and FPN modules in the model, experiments are conducted by separately adding or removing the relevant modules. The detection accuracy of the model under different combinations are compared. The experimental results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparisons of experimental results for combinations of different modules.

The experimental results show that the combination of ResNet50_CDCN + ROI Align + FPN achieves the best detection performance, with a mAP of 91.20%. Compared to the ResNet50 + RoI Pooling combination, the model’s precision in mAP (IoU = 0.75) improved by 5%.

3.6. Comparison of Different Models

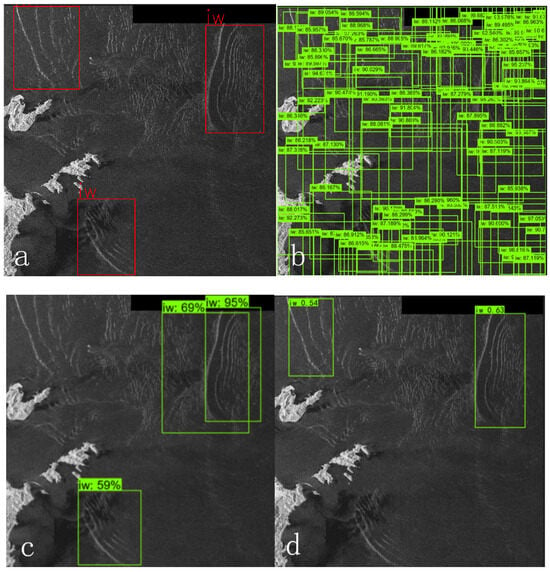

To evaluate the detection performance of the improved Faster R-CNN model, its results were compared with those of classical single-stage detectors including YOLOv3 [32,33], SSD [34] and RetinaNet [35]. The comparison results are presented in Table 4. Unlike two-stage methods, single-stage detectors directly predict candidate bounding box coordinates, object classes, and corresponding confidence scores from the input images using a single neural network, enabling faster inference.

Table 4.

Comparisons among different detection models.

The SSD model offers high detection speed with certain precision advantages, particularly performing well in small object detection (Figure 11). However, due to the typically larger target scale in ocean internal wave images, SSD generates a large number of invalid boxes during detection, and the bounding box regression accuracy is relatively low, leading to suboptimal detection results. RetinaNet, which uses Focal Loss, effectively mitigates the foreground-background sample imbalance issue, making it more robust for detecting challenging targets like internal waves. In the experiments, RetinaNet achieved good detection results in most scenarios, but in images with strong background interference or unclear target textures, there were still missed detections. This suggests that its discriminative ability in certain complex scenes remains limited. YOLOv3 demonstrated extremely high detection speed in practical applications, making it suitable for real-time scenarios. However, its precision in the ocean internal wave detection task was relatively low, especially when dealing with complex ocean backgrounds, where numerous false positives and missed detections were observed. This indicates that its ability to capture fine-grained targets requires improvement. Although YOLOv9 demonstrates high detection speed and stability, with a detection speed significantly surpassing other models due to its input image size of 640 × 640, its accuracy still has room for improvement when recognizing complex or small-scale targets.

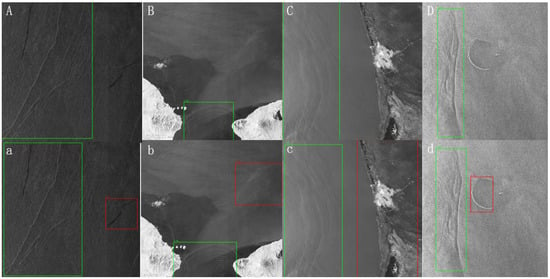

Figure 11.

Detection results of different models for the same sample: (a) Ground truth labels; (b) the SSD model; (c) the RetinaNet model; (d) the YOLOv3 model; (e) YOLOv9 model; and (f) rFaster R-CNN. The numbers next to the rectangles represent the accuracy.

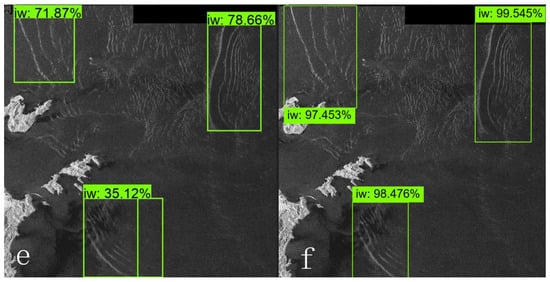

In summary, the improved Faster R-CNN model demonstrates the best overall performance among the evaluated methods. It effectively reduces missed detections during the detection process while achieving higher object confidence scores and more accurate bounding box localization, highlighting its strong feature representation capability and robust object discrimination ability. Although the inference speed of the proposed model is not the fastest, real-time performance is not a strict requirement for the current task of ocean internal wave detection. Therefore, achieving baseline efficiency is sufficient, and a moderate sacrifice in detection speed in exchange for higher accuracy is both reasonable and acceptable. Experimental results further confirm that the proposed model can recognize ocean internal waves accurately and stably, indicating promising application potential and practical value (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Panoramic SAR image detection of internal waves under complex interference. The figure presents detection results in four representative and challenging SAR scenarios: (a) oil spill interference, (b) wave-field scenes, (c) coastal regions, and (d) island-dominated areas. For each scenario, panels (A–D) show the results of the proposed rFaster R-CNN, while panels (a–d) present the results obtained by replacing only the backbone with ResNet-50. True positive detections are marked in green, and false positives are indicated in red.

The experimental results demonstrate that rFaster R-CNN can accurately capture internal wave (iw) under complex interference, and the detection results are highly consistent with the visual prior knowledge of iw.

4. Discussion

This study proposed an improved Faster R-CNN framework, termed “rFaster R-CNN”, enhanced by transfer learning, to achieve automatic and accurate detection of ocean internal waves in SAR imagery. The introduced backbone, ResNet50_CDCN, integrates deformable convolution and attention mechanisms to enhance feature adaptability and focus, thereby achieving excellent performance in internal wave region localization, boundary discrimination, and confidence estimation. This improvement provides a solid technical foundation for achieving high-precision detection of internal waves in complex marine environments and serves as a reference for future SAR-based ocean dynamic monitoring applications.

In the feature extraction stage, The proposed ResNet50_CDCN achieves an approximately 3% improvement in recognition accuracy compared with the original ResNet50 under the same conditions.

With a mAP of 91.20%, the refined Faster R-CNN model outperforms mainstream detectors such as SSD, RetinaNet, and YOLO in terms of accuracy and robustness.

Although the integration of multiple modules significantly enhances detection accuracy, it inevitably increases the model’s parameter scale and computational cost. Moreover, the inherent speckle noise and texture complexity of SAR images continue to pose challenges to precise detection. In future work, incorporating model compression techniques—such as pruning, knowledge distillation, and quantization—will be explored to balance performance and efficiency, facilitating practical deployment in real-time marine observation systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z.; Methodology, G.S., Z.Z. and H.H.; Validation, G.S., Z.Z., Z.J. and J.S.; Data curation, G.S. and Z.Z.; Writing—original draft, G.S.; Writing—review & editing, G.S., Z.Z., H.H., Z.J. and J.S.; Supervision, Z.Z. and H.H.; Project administration, H.H. and J.S.; Funding acquisition, Z.Z. and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Basic Scientific Research Project of Higher Education Institutions in Liaoning Province (Grant No. LJ212410158059), the Basic Scientific Research Business Expenses Project of Provincial Undergraduate Colleges and Universities in Liaoning Province (Grant No. 2024JBQNZ006), the Liaoning Province Doctoral Research Start-up Fund Program Project (Grant No. 2024-BS-207), the Dalian Ocean University 2024 Discipline Construction Connotation Cultivation Special Project (Grant No. 505324207005), and the Dalian Ocean University Talent Introduction Project (Grant No. XL20230001).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used ChatGPT (v4.0) for the purposes of language polishing and readability improvement. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CBAM | Convolutional Block Attention Module |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DCN | Deformable Convolution Network |

| FPN | Feature Pyramid Network |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| RPN | Region Proposal Network |

| SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

References

- Gerkema, T.; Zimmerman, J. A Introduction to Internal Waves; Lecture Notes; Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research: Den Burg, The Netherlands, 2008; p. 445. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.-Z.; He, Y.-B.; Li, X.-D.; Duan, T.-Z. Reply to Shanmugam, G. “Review of research in internal-wave and internal-tide deposits of China: Discussion”. J. Palaeogeogr. 2014, 3, 351–358. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, S.; Gan, Z. Progress in the study of the internal solition in the northern South China Sea. Adv. Earth Sci. 2001, 16, 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, P.; Alpers, W.; Backhaus, J.O. Study of the generation and propagation of internal waves in the Strait of Gibraltar using a numerical model and synthetic aperture radar images of the European ERS 1 satellite. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 1996, 101, 14237–14252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Boris, K.; Li, Z.; Zhang, R.; Luo, W.; Katsnelson, B. Intensity fuctuations due to the motion of internal solitons in shallow water. Shengxue Xuebao 2016, 41, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.K.; Chang, Y.S.; Hsu, M.K.; Liang, N.K. Evolution of nonlinear internal waves in the east and south china seas. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 1998, 103, 7995–8008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenas, J.A.; Garello, R. Detection and location of internal waves in ocean SAR images by means of wavelet decomposition analysis. In Proceedings of the IGARSS’96. 1996 International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Lincoln, NE, USA, 27–31 May 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Zhang, J.; Song, P.; Meng, J. The application of two-dimensional EMD to extracting internal waves in sar images. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Science & Software Engineering, Wuhan, China, 12–14 December 2008; pp. 953–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Donahue, J.; Girshick, R.; Darrell, T. Part-based R-CNNs for Fine-grained Category Detection. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R. Fast r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, N.; Feng, L.; Zhang, X. Aircraft detection in remote sensing image based on optimized Faster-RCNN. Remote Sens. Technol. 2021, 36, 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Jiang, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Q. On orbit extraction method of ship target in SAR images based on ultra-lightweight network. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 2021, 25, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; Meng, J.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y. Detection of ocean internal waves based on Faster R-CNN in SAR images. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2020, 38, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Jia, T.; Shi, Y.; Li, X. Faster R-CNN based oceanic internal wave detection from SAR images in the South China Sea. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 2023, 27, 905–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Huang, L.; Yang, J.; Ren, L.; Li, X.; He, S.; Liu, A.K. Transformer-Based Hierarchical Multiscale Feature Fusion Internal Wave Detection and Dataset. Ocean-Land-Atmos. Res. 2024, 3, 0061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ye, R.; Ren, D. Distance-IoU loss: Faster and better learning for bounding box regression. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Volume 34, pp. 12993–13000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Qi, H.; Xiong, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y. Deformable convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santurkar, S.; Tsipras, D.; Ilyas, A.; Madry, A. How does batch normalization help optimization? arXiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, L.; Xu, J.; Zheng, C. ReLU deep neural networks and linear finite elements. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.03973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollar, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, J.; Bello, J.P. Deep convolutional neural networks and data augmentation for environmental sound classification. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2017, 24, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, N.; Gygli, M.; Pfister, B.; Van Gool, L. Deep convolutional neural networks and data augmentation for acoustic event detection. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1604.07160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Yang, J. S1-IW-2023 Dataset (Ocean Internal Wave Dataset); Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y. Fine-grained ship classification based on deep residual learning for high-resolution SAR images. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 10, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambour, C.; Audebert, N.; Koeniguer, E.; Le Saux, B.; Crucianu, M.; Datcu, M. Flood detection in time series of optical and sar images. ISPRS Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 43, 1343–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Mark Liao, H.Y. Yolov9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Part I. pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.