Abstract

Digitalization has resulted in ships being equipped with more computerized systems. Even though this transformation has improved navigational safety and operational efficiency, it has also raised cyber security concerns significantly. To address such concerns, this study proposes a national Maritime Cyber Security Operations Center (M-SOC) concept, aiming at protecting vessels against cyber-attacks. The proposed concept was developed by following a SOC-related guideline published by MITRE. Subsequently, the initial draft was evaluated through the Focus Group technique. Thematic Data Analysis was employed to analyze feedback from domain experts. By considering expert input, the draft concept was improved. Consequently, the 11-element recommendation presented in the study contributes to the development of a center capable of detecting and responding to cyber threats targeting ships within a designated sea zone. The operation of M-SOCs is expected to enhance the cyber resilience of the maritime ecosystem at the national level.

1. Introduction

The maritime sector facilitates over 80% of global trade by volume [1]. This transportation is performed by a fleet of 108,789 cargo ships [2]. However, ships are not operated only for cargo transportation. A total of 836,342 ships in the world serve different purposes, including research, training, fishing, defense, transportation, and leisure activities [3]. In this article, the term “vessel” or “ship” defines all kinds of watercraft, such as commercial ships, warships, and special-purpose vessels, all with computerized systems that integrate Information Technology (IT) with Operational Technology (OT) systems. These systems are essential for the safe and efficient operation of conventional vessels today and remote-controlled or autonomous ships in the future.

In recent years, contemporary ships have been frequently targeted by cyber-attacks. According to the estimation of “Above Us Only Stars”, a total of 1311 civilian vessels were damaged by Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) spoofing attacks conducted by Russia between February 2016 and November 2018 [4]. Additionally, South Korea claimed that in 2017, 280 of their ships had to return to port because of a Global Positioning System (GPS) jamming attack carried out by North Korea [5]. In 2022, the hacker group Anonymous manipulated the Automatic Identification System (AIS) of Vladimir Putin’s yacht, changing its maritime data to rename the vessel and depict it as colliding with Snake Island in Ukraine [6]. In 2024, the United States of America (USA) was allegedly accountable for a cyber-attack on the Iranian naval vessel M/V (refers to Motor Vessel) Behshad in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden to disrupt its intelligence-gathering and sharing capabilities [7]. These incidents highlight the growing cyber vulnerability of vessels.

Cyber security risks should definitely be addressed for the safe operation of ships. However, cyber security is a complex field. Ensuring effective cyber security requires bringing together different areas of expertise and coordinating the process well. Within this framework, experts collaborate to perform critical actions in cyberspace defense, such as protecting, detecting, characterizing, countering, mitigating, and restoring [8]. There is no universally agreed-upon term for these roles [9]. Thus, various notions are available to describe groups of cyber security specialists, such as Computer Security Incident Response Team (CSIRT), Cyber Incident Response Team (CIRT), Computer Incident Response Center (CIRC), Security Operations Center (SOC), and Cybersecurity Operations Center (CSOC) [9]. Based on these notions, this study introduces the Maritime Cyber Security Operations Center (M-SOC). In summary, the M-SOC is a specialized center operated to meet the unique cyber security needs of maritime stakeholders.

The Committee on National Security Systems (CNSS) is responsible for developing and implementing cyber security policies, directives, and procedures aimed at safeguarding the United States (U.S.) Government’s National Security Systems (NSS) [10]. Given that there is no official definition for the M-SOC, this study also proposes a comprehensive definition. In explaining the M-SOC, the definitions of the terms “CIRT,” “cyberspace defense,” and “maritime cyberspace” from the CNSS glossary are considered [8].

An M-SOC is a dedicated facility or experts focused on protecting, detecting, characterizing, countering, mitigating, and restoring maritime cyberspace. It consists of a group of skilled experts who work on cyber security risks and incidents impacting the interconnected networks of IT and OT systems, including resident data, the electromagnetic spectrum, telecommunications infrastructure, computers, communication systems, as well as embedded processors and controllers crucial to maritime processes and operations. M-SOC specifically addresses the unique cyber security challenges of the maritime ecosystem, including safeguarding systems against cyber threats such as AIS and GNSS attacks, malware, unauthorized user activities, and other potential breaches.

1.1. Objective

The objective of this paper is to propose a national M-SOC concept designed to protect vessels from cyber-attacks within a designated sea zone. These are essential components of this concept:

- Establishment and Operation: a comprehensive framework covering the organizational structure, legal matters, responsibilities, and performance measurement metrics.

- Real-Time Monitoring: a system that continuously monitors the designated sea zone from the M-SOC to promptly detect potential cyber threats.

- Incident Response: a comprehensive response plan to be followed by the crew, M-SOC staff, and other stakeholders in case of a cyber-attack.

- Communication and Collaboration: an arrangement for sharing threat intelligence, fostering collaboration, and guaranteeing prompt reporting to the regulatory bodies.

1.2. Novelty and Contribution

As of 1 October 2025, and to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to propose a comprehensive national-level M-SOC concept designed for the protection of vessels against cyber-attacks within a designated sea zone, without requiring any physical or software installation onboard or prior consent from the vessels. It should also be acknowledged that other national or regional cyber-maritime initiatives may exist; however, many of these efforts have not yet been published in peer-reviewed form and therefore remain outside the scope of this study. The studies in the literature regarding M-SOCs are quite limited and typically focus on specific themes, such as training M-SOC personnel or securing certain ships, often assuming privileged access to ship networks. However, this research provides a more thorough, scalable approach that is independent of ship-specific infrastructure. Eleven elements defined by MITRE were employed to propose a national M-SOC concept, which addresses significant subjects, such as staff qualification, cyber threat intelligence (CTI), data sources to be monitored, tools to be developed, and performance evaluation metrics. To ensure its practical relevance and applicability, the concept was designed by considering not only the authors’ perspectives but also the domain experts’ thoughts.

1.3. Scope

The scope of this paper is limited to vessels. Ports, terminals, shipyards, and other shore-based facilities are excluded from the scope of the study. The paper provides recommendations regarding the establishment and operation of a national M-SOC aimed at protecting vessels within a designated sea zone from potential cyber-attacks. While the literature includes comprehensive studies on conventional SOCs, this paper focuses only on the aspects that distinguish M-SOCs from traditional SOCs. Furthermore, issues such as IT operations and physical security requirements necessary for the routine functioning of any SOC are also excluded from the scope of this study.

1.4. Structure

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides information about national and non-profit organizations that address cyber security challenges in the maritime domain. Related works regarding M-SOCs in the literature are reviewed in Section 3. Section 4 describes the methodology employed in detail. Section 5 presents the elements of the proposed national M-SOC concept regarding its establishment and operation. Section 6 discusses the findings and implications with respect to maritime cyber security, M-SOCs, and the elements of the proposed concept. Finally, Section 7 summarizes the research and suggests potential directions for future work.

2. Background

The increasing frequency and complexity of cyber-attacks in the maritime sector have caused the establishment of various national and non-profit organizations. This section presents national maritime cyber security organizations in Denmark, Singapore, and the U.S. In addition, non-profit initiatives in France and Norway are introduced. By examining the structures and services provided by these organizations, insights into global initiatives can be gained.

2.1. National Maritime Cyber Security Organizations

States have established organizations to protect their maritime infrastructure against increasing cyber-attacks. To the best of our knowledge, three national organizations are available to protect the maritime domain from cyber-attacks: the Danish Maritime Cybersecurity Unit, the Maritime Cybersecurity Operations Centre in Singapore, and the U.S. Coast Guard Cyber Command (CGCYBER). The following subsection provides a brief description of these organizations.

2.1.1. Denmark—Danish Maritime Cybersecurity Unit

Denmark has a national cyber security center called the Center for Cybersikkerhed (Centre for Cyber Security); notwithstanding [11], a specialized unit was required to address cyber threats in the maritime ecosystem. Accordingly, the Danish Maritime Authority (DMA) [12], which operates under the Ministry of Industry, Business, and Financial Affairs, founded the Danish Maritime Cybersecurity Unit in July 2018.

The responsibility of this unit is to protect Danish-flagged ships, ships in Danish territorial waters, and maritime stakeholders in Denmark from cyber-attacks, as an internal specialist under the DMA [13]. It advises maritime stakeholders on cyber security issues. Moreover, it facilitates information sharing and communication among stakeholders. The unit also organizes training events, workshops, and conferences to improve cyber security awareness [14]. One of its initiatives is the publication of the Cyber and Information Security Strategy for the maritime sector [13]. This strategy document sets out a framework designed to provide greater cyber security resilience for the maritime sector in Denmark. It also outlines how Denmark will consider and manage cyber risks in a maritime context.

2.1.2. Singapore—Maritime Cybersecurity Operations Centre

The Cyber Security Agency of Singapore (CSA) was founded in 2015 to establish national cyber security policies [15]. Despite the CSA, the Maritime Cybersecurity Operations Centre (MSOC) was launched by the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA) in 2019 [16,17]. The Port Operations Control Centre also collaborates with the MSOC to respond to cyber-attacks. MSOC operates 24/7 to protect Critical Information Infrastructure (CII) in the maritime environment. The center is responsible for real-time cyber threat detection and incident response by employing advanced technologies. The MSOC identifies cyber-attacks by analyzing activities in the IT environment.

In 2025, the MPA plans to extend the functions of M-SOC as the Maritime Cyber Assurance and Operations Centre (MCAOC) [18,19]. The MCAOC is expected to share information with maritime stakeholders about new malware and cyber-attack techniques. Cyber security training and exercises are also anticipated to be organized for the improvement of cyber resilience in the maritime sector.

2.1.3. USA—Coast Guard Cyber Command (CGCYBER)

Despite the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) in the USA [20], the U.S. Coast Guard Cyber Command (CGCYBER) was founded to improve the cyber security capabilities of the U.S. Coast Guard [21]. The CGCYBER serves under the Department of Defense (DOD), and the U.S. Coast Guard adopts required policies to protect critical infrastructures of the Maritime Transportation System (MTS). The CGCYBER is in collaboration with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the DoD, port authorities, the private sector, and international partners to enhance maritime cyber security globally.

The CGCYBER has a large organizational structure comprising various divisions for cyber security operations, network security, and cyber mission support. Specialized teams, including Cyber Protection Teams (CPTs) and the Maritime Cyber Readiness Branch (MCRB) [22], prevent and respond to cyber-attacks against MTS. The CGCYBER is also responsible for protecting the U.S. Coast Guard Enterprise Mission Platform (EMP). Moreover, it manages cyber security frameworks, compliance, and threat intelligence sharing for risk mitigation. It leverages its intelligence capabilities to identify the intentions of malicious actors.

2.2. Non-Profit Maritime Cyber Security Organizations

To the best of our knowledge, two non-profit organizations dedicated to maritime cyber security services are available, such as France Cyber Maritime in France and NORMA Cyber in Norway. Both initiatives were established in 2020 with the support of maritime stakeholders to address cyber security challenges of the sector. They work closely with governmental authorities and support strengthening resilience against cyber threats. The following subsections describe the specialized services of each of these organizations.

2.2.1. France—France Cyber Maritime

France Cyber Maritime was founded on 17 November 2020, as a non-profit organization under the leadership of the French General Secretary for the Sea (SGMer) and with the support of the French National Cybersecurity Agency (ANSSI) [23]. The main objective of France Cyber Maritime is to improve the cyber resilience of marine and port operations by evolving a collaborative network of knowledge in maritime cyber security. Comprising over 70 members, it unites public sector bodies, coastal authorities, ship operators, and cyber security solution providers.

France Cyber Maritime funds the Maritime Cyber Emergency Response Team (M-CERT), which is a specialist CSIRT for the maritime sector [24]. M-CERT acquires advantages from coordination agreements on marine cyber security established by France Cyber Maritime, the French Navy, and the French Gendarmerie Maritime. M-CERT focuses on monitoring and analyzing cyber threats to provide maritime cyber security intelligence and coordinate responses to cyber incidents [25]. Its services encompass incident management, vulnerability disclosure, and passive preventive monitoring of maritime assets [26]. Moreover, M-CERT operates ADMIRAL (stands for Advanced Dataset of Maritime cyber Incidents ReleAsed for Literature) dataset [27], which includes maritime cyber security incidents for training and research purposes. It contributes to the global maritime cyber security by collaborating with other CERTs and CSIRTs.

2.2.2. Norway—NORMA Cyber

In late 2020, NORMA Cyber was founded through the initiative of the Norwegian Shipowners’ Association (NSA) and the Norwegian Shipowners’ Mutual War Risks Insurance Association (DNK) [25] as a non-profit company. NORMA Cyber became operational in January 2021 and began to offer various cyber security services, such as threat intelligence, incident and crisis management, and security monitoring.

In 2024, NORMA Cyber began to support the Norwegian Coastal Administration (NCA) in its responsibility as the sectoral response function for maritime cyber security [28], including vulnerability warning dissemination, information sharing relevant to cyber security incident reporting, and advisory support during incidents and crises. NORMA Cyber collaborates with the Norwegian Maritime Authority and the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) to coordinate response efforts to ensure the overlapping cyber security efforts within Norway’s maritime sector.

One of the most important services provided is to act as a SOC for vessels, which monitors and operates the cyber security of IT and OT systems onboard ships [29]. Many tasks are performed in the SOC, such as threat monitoring, vulnerability scanning, and incident response. Moreover, NORMA Cyber offers additional services for the maritime stakeholders, such as monthly threat assessments, vulnerability notifications, and 24/7 crisis support.

3. Related Work

This section provides detailed information about the current research status of M-SOCs in the literature. In this section, six publications, which address design, implementation, operations issues, and training proposals, are investigated for M-SOCs. We discuss challenges that obstruct the enhancement of cyber resilience in ships, including limited connectivity, varied operational technologies, and the requirement for specialized cyber security protocols. We also highlight the contribution of this paper to the current literature.

Nganga et al. [30] investigated the factors impacting the effectiveness of M-SOC operations. To this end, the authors conducted semi-structured interviews with nine M-SOC experts. Grounded Theory was employed for data analysis. This research unveiled a lack of qualified staff in M-SOCs. Moreover, CTI is limited to maritime infrastructures. The internet quality onboard ships directly affects real-time monitoring of network activities. Bandwidth is another significant limitation. The study also discusses the future integration of M-SOCs with Remote Operation Centers (ROCs) of autonomous ships.

Nganga et al. [31] proposed a CTI sharing model for the maritime industry from the M-SOC analysts’ perspective. In this study, existing cyber information sharing frameworks were investigated, such as the Trusted Automated eXchange of Indicator Information (TAXII) [32] and Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs) [33]. The authors proposed a vessel-specific threat intelligence sharing model inspired by the aviation sector and based on the International Association of Classification Societies (IACS) guidelines. The proposed model has not been tested or evaluated.

Nganga et al. [34] identified maritime-specific human factors that influence the adaptive response capabilities of M-SOC analysts in the study. To this end, semi-structured interviews were conducted with nine experts working in M-SOCs. Grounded theory was employed for data analysis. According to research results, limited visibility of ship systems from M-SOCs leads to difficulties in detecting and responding to cyber incidents. Given that there are no cyber security experts onboard, experts need to guide crew members step by step during a cyber incident. This causes delays in incident response. Experts recommend more realistic training and using visual demonstrations to improve the cyber awareness of the crew.

Jacq et al. [35] proposed an M-SOC architecture to detect and respond to cyber threats in maritime environments. The authors designed six modules, including Network Connexion Safety, Network Probe Isolation, Local Preprocessor, Local Engine, Ship Shore Manager, and Cyber Situational Awareness Console. The IT and OT networks onboard were monitored. In the case of an alert, the metadata and logs were compressed and automatically transmitted to the M-SOC facility on the shore for further analysis. The proposed architecture was tested under different scenarios, such as a cyber-attack or low satellite bandwidth. Experts from both the military and civilian sectors positively evaluated it.

Raimondi et al. [36] proposed a specialized training program for SOC operators working in maritime environments. The authors defined the specific skills and knowledge required for M-SOC operators by employing the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE) framework. Then, they developed a training scenario and implemented it using a digital twin framework. This framework facilitated the simulation of real-world maritime scenarios and hands-on training for M-SOC staff. The proposed training program led to an understanding of maritime-specific issues, such as bandwidth limitations and shipboard equipment behavior.

Nikolov [37] presented a concept for a Security Operations and Training Center (SOTC) to be established at the Nikola Vaptsarov Naval Academy (NVNA). The concept includes dedicated facilities such as lecture halls, computer labs, and simulation control rooms. The SOTC was designed both for the training of IT specialists and for protecting the academy’s network. Even though the current concept does not directly address the specific cyber security needs of the maritime industry, it may allow maritime cyber security studies by integrating maritime simulators of the academy in the future.

The studies focus on the development, implementation, and training aspects of M-SOCs. Ships present unique technical challenges to be addressed by M-SOCs, including specialized protocols, operational technologies, and connectivity limitations. Moreover, the necessity of maritime-specific knowledge and skills is stated for M-SOC personnel. To this end, training programs employing simulation-based platforms and digital twins have been proposed. The literature review unveils that the operation of an M-SOC requires a comprehensive approach combining robust technological infrastructure with specialized experts for ship systems.

Our research addresses an important deficiency in the literature by proposing a national M-SOC concept. Unlike previous studies, our concept introduces a framework capable of supporting and providing early detection to all vessels operating in a designated sea zone. This approach transitions from asset-specific monitoring to zone-wide situational awareness. Moreover, our study discusses many dimensions of M-SOC, such as legal authorization, threat intelligence, incident response, communication, and collaboration. To the best of our knowledge, this work offers the most comprehensive foundation for the establishment and operation of a national M-SOC.

4. Methodology

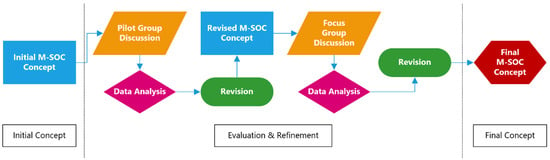

This section describes the systematic approach to proposing a national M-SOC concept. The methodology consists of three main phases, as shown in Figure 1. First, the M-SOC concept was developed by following the SOC strategies published by MITRE. Second, the proposed M-SOC concept was evaluated through the Focus Group technique, which enabled validation by domain experts. Third, the discussions held during the Focus Group meeting were analyzed to identify key patterns and insights by employing Thematic Data Analysis. Based on the outcomes of this analysis, the initial M-SOC concept was further improved. This section facilitates the evaluation of the robustness and validity of the proposed concept by clearly outlining the research design.

Figure 1.

Graphic Illustration of the Methodology Performed.

Artificial intelligence (AI) writing assistants, ProWritingAid [38] and Grammarly Pro [39], were employed to improve the clarity and academic readability of the paper. Both writing tools contributed to the refining of the paper by making suggestions for grammar, writing style, sentence structure, and overall organization.

4.1. MITRE Guidelines

As discussed in Section 3, a comprehensive methodology for developing a national maritime-specific SOC concept aligned with the objectives of this study was not identified in the literature. Consequently, we reviewed scientific papers addressing the development of generic SOCs. Most of these publications concentrate on one component of the cyber security triad, namely people, process, and technology, focusing on areas such as performance measurement [40,41], alert analysis [42], design frameworks [43], and the use of SOCs for education [44]. Among the reviewed works, Mughal’s article [45] stood out; however, more extensive and relevant sources were identified that provided better guidance for our research.

A guideline [46] prepared by Taurins and published by the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) was identified, but it was narrower in scope compared to the alternatives we found. A more comprehensive resource was the book Open-Source Security Operations Center (SOC) [47]. However, it focuses particularly on the technology aspect of SOCs. Another relevant source was the Modern Security Operations Center [48], which addresses people, process, and technology. While the book was up to date and comprehensive, it was not convenient to adopt it as a methodology. Although our study is not directly based on the publications mentioned in this paragraph, we acknowledge their contributions and affirm that our work builds upon these foundational sources.

MITRE [49] is a recognized organization in cyber security field for its integrity, technical expertise, and innovative solutions. With several Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDCs) [50], MITRE provides objective and data-based solutions while connecting government, industry, and academia. MITRE is known for two important contributions. The first is the Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge (ATT&CK) Framework [51], which classifies malicious behaviors. The second is the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) Program [52], which maintains standardized identifiers for publicly known vulnerabilities and facilitates collaborative innovation. MITRE resolves complex national security issues and contributes to enhancing the global cyber security ecosystem.

In 2014, MITRE published the Ten Strategies of a World-Class Cybersecurity Operations Center [53] to support the establishment of effective SOCs. This work was revised in 2022 and was published as a second edition titled 11 Strategies of a World-Class Cybersecurity Operations Center [9]. The 2022 version provided a more extensive revision by building upon the original framework. The first edition of the guidelines was authored by Carson Zimmerman. Kathryn Knerler and Ingrid Parker also contributed to the second edition. Both editions were prepared by considering the thoughts and experiences of many professionals and academics.

In this study, we followed MITRE’s guidelines and adapted them to propose the development of a maritime-specific SOC, called M-SOC, which could be established by national governmental organizations. A mapping between the strategies offered by MITRE and the elements for developing an M-SOC is provided in Table 1, which demonstrates the alignment between the two approaches.

Table 1.

Strategies Offered by MITRE and Elements for the Development of an M-SOC.

The M-SOC concept consists of 11 elements in total. To assess its effectiveness and usability, the Focus Group technique [54] was employed. It is important to note that the Focus Group method was utilized exclusively for the evaluation of the proposed M-SOC concept within the scope of this study. Implementers of the M-SOC concept are not required to apply the Focus Group technique as part of its implementation process.

4.2. Focus Group Technique

The Focus Group technique is a qualitative research method that was first used in the 1920s for market research purposes [55,56]. Beck et al. [57] define the Focus Group technique as “an informal discussion among selected individuals about specific topics.” It can be utilized as a standalone research method or to elaborate on or evaluate another study [55]. A Focus Group provides participants with the opportunity to express their opinions, explain their thoughts, disagree, and share their experiences and attitudes [56]. The interactive feature enables authors to investigate topics more thoroughly as participants discuss, articulate, and refine their viewpoints [56]. It also uncovers the variances in ideas among diverse participant groups [58]. The method encompasses interactions between the participant and the authors, as well as interactions among participants [59]. These interactions collectively enhance the exchange of ideas and viewpoints. Therefore, it allows for improving the study. The Focus Group technique is widely used in various fields such as market research, psychology, and education, and is increasingly applied in cyber security research to gather insights and understand attitudes towards security practices and threats [60,61,62,63].

Several qualitative research methods are based on participant opinions, and the one-to-one interview is one such method [64]. One-to-one interviews primarily focus on the sharing of personal experiences. On the other hand, the Focus Group technique is specifically designed to stimulate the generation of new ideas [64]. Another potential method for this study is the Nominal Group technique. The Nominal Group technique relies on spontaneous responses rather than carefully considered ones, which may lead to the misinterpretation of new ideas [55]. In contrast, the Focus Group technique allows participants to reflect upon, clarify, and enhance their views in light of the points raised by other participants [55]. Therefore, we believe that the Focus Group technique is an appropriate method for the evaluation of our research.

Before the Focus Group meeting, a smaller-scale meeting was conducted. This preliminary session is called the Pilot Group meeting in this study. The Pilot Group discussion served several purposes. First, it allowed for the early identification of major issues of the proposed M-SOC concept. Therefore, the authors revised it before the Focus Group meeting. Second, authors could evaluate the questions prepared for the Focus Group discussion. The questions should have been formulated in alignment with the objectives of the study. Last of all, the authors had an opportunity to realize potential technical or organizational problems which might arise during or after the Focus Group meeting. In summary, the Pilot Group discussion allows the authors to evaluate the concept, questions, and potential challenges for the Focus Group session.

4.3. Thematic Analysis

The qualitative data collected from both the Pilot Group and the Focus Group meetings were analyzed using Thematic Data Analysis. It is a widely used method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) in qualitative data [65]. This method enables even complex data to be easily analyzed. It is flexible and can be used to find patterns in many different types of data [65]. The six-phase framework outlined by Braun and Clarke was implemented in this study, as follows [65]:

- Familiarizing yourself with your data;

- Generating initial codes;

- Searching for themes;

- Reviewing themes;

- Defining and naming themes;

- Producing the report.

The Thematic Analysis facilitated a systematic interpretation of the experts’ insights. In the practical execution of the analysis, the open-source software QualCoder [66] was utilized to provide an efficient and transparent environment for the coding and categorisation process.

4.4. Implementation for Evaluation of the M-SOC Concept

In the meetings, the moderator plays a key role. The moderator’s primary role is to facilitate open and unrestricted dialogue [55]. The moderator should be receptive to relevant issues raised by participants that have not been anticipated and should encourage equal participation from all group members [55]. Furthermore, the moderator is responsible for providing information about the study and ensuring that participants understand the purpose and structure of the discussion. The lead of this paper served as the moderator in the Pilot and Focus Group meetings.

For both meetings, we have carefully identified specific criteria for selecting researchers and professionals by considering a diverse and highly qualified group of participants who can contribute valuable insights to the study. The qualifications required are as follows:

- Researchers who have published at least two scientific papers as the lead author or five scientific papers as a co-author on maritime cyber security;

- Professionals who work in the maritime cyber security field;

- Senior officers (current or former), such as masters and chief engineers.

Participation was entirely voluntary in both the Pilot and Focus Group meetings. One researcher and one professional specializing in maritime cyber security participated in the Pilot Group discussion. 17 participants attended the Focus Group discussion. The profiles of the participants (except the authors of this study) are presented in Table 2. Specifically, the Focus Group included five researchers from four universities, six professionals from three IACS member classification societies, two professionals from two consultancy companies specializing in maritime cyber security, one professional from a dry bulk ship operator, one professional from a global ship systems manufacturer, and two professionals from an intergovernmental organization (IGO). Among the participants, three had a maritime background, while the remaining 14 had expertise in cyber security.

Table 2.

Profiles of the Participants in the Focus Group.

After each element was presented in detail, comments and recommendations were collected from the participants. Following a comprehensive discussion of each element, the open-ended questions were asked to initiate a general discussion among the participants regarding M-SOCs, as follows.

- How does an M-SOC differ from a traditional SOC?

- Would the establishment of an international M-SOC be beneficial for the maritime sector?

- Is it expected that M-SOCs will become widespread in the future?

- Should a national M-SOC be allowed to offer paid services to private companies?

Although the Pilot Group meeting lasted 2.5 h, the Focus Group session took longer due to the larger number of participants. The discussions lasted a total of six hours and were divided across two separate days to minimize the impact on participants’ ongoing work. Both discussions were conducted online using MS Teams. Video and written transcripts of each session were automatically recorded. Following the discussions, the recordings were thoroughly analyzed, as described in Section 4.3. By considering findings and observations, the M-SOC concept was revised. Additional findings and insights from the discussions are also presented in this paper.

5. Building a National M-SOC Concept

In this section, the details of the proposed national M-SOC concept are discussed. The section comprises 11 sub-sections, and each addresses an element of the concept. Therefore, the study is presented in a comprehensive and structured approach. This detailed explanation not only reflects the findings and observations of the study but also offers a useful guide for stakeholders to improve national maritime cyber security.

5.1. Element 1: Building Situational Awareness

The purpose of this element is to build situational awareness by understanding the mission and primary responsibilities of the M-SOCs, potential hazardous situations, the shipboard environment, the threat landscape, the regulatory environment, and crew and individual behaviors [9].

In this study, the mission of a national M-SOC is to support the protection of vessels within a designated sea area against cyber threats. It may function as a separate entity or part of a maritime organization, such as a Vessel Traffic Service (VTS). The main responsibilities of an M-SOC include:

- Identifying critical cyber risks that may cause hazardous situations onboard ships;

- Developing comprehensive response and recovery plans for cyber incident scenarios occurring on vessels;

- Conducting cyber incident investigations to determine the root cause, assess the impact, and develop mitigation strategies to prevent recurrence;

- Raising cyber security awareness for the maritime stakeholders;

- Advising regulatory bodies and policymakers on developing and enhancing maritime cyber security frameworks; and

- Sharing CTI with stakeholders, such as maritime authorities, law enforcement agencies, and cyber security organizations.

Currently, the enforcement of the International Safety Management (ISM) Code [67] is compulsory for all vessels subject to the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) [68]. Accordingly, the ISM Code is implemented on almost all commercial ships around the world. This leads to ensuring safety and environmental safeguards in the maritime sector. As stated in the ISM Code, “The Company should identify equipment and technical systems the sudden operational failure of which may result in hazardous situations” [69]. However, the ISM Code does not obviously define what constitutes a “hazardous situation.”

The Oil Companies International Marine Forum (OCIMF) is a non-governmental organization officially recognized by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) with consultative status [70]. It was established in April 1970 to mitigate growing concerns about marine pollution [71]. Today, OCIMF has over 100 members, including major oil companies such as British Petroleum (BP), Shell, and Chevron [72]. OCIMF defines a hazardous situation as “a situation that may directly cause an accident that causes harm to people and the environment” [73]. To provide clearer guidance, OCIMF classifies hazardous situations as follows [73]:

- Loss of steering;

- Loss of propulsion;

- Loss of power;

- Loss of inert gas system;

- Loss of gas monitoring system;

- Loss of cargo/ballasting monitoring equipment;

- Loss of mooring.

Such hazardous situations are a primary concern in the context of cyber risks faced by vessels. In addition to these systems, ships have extensive IT networks supporting both business operations and crew welfare. Furthermore, cyber-attacks targeting components (e.g., AIS) may rely on radio channels, such as Very High Frequency (VHF). The staff in the M-SOC should deeply understand ship systems, their connections, and their dependencies. Thus, a faster and more effective cyber response would be possible in case of a cyber incident. It is also fundamental to maintain an awareness of sensitive onboard data, including crew, passenger, and cargo information.

Because of their complex IT and OT systems, ships are frequently targeted by various threat actors, both in targeted and untargeted attacks. In addition to cybercriminals and hacktivists, vessels are also vulnerable to state-sponsored attacks, such as GNSS spoofing, GNSS jamming, and AIS spoofing [74]. These attacks are often conducted for purposes such as testing electronic warfare technologies or blocking hydrocarbon exploration activities [74].

An M-SOC should comply with national, regional, and international regulations. At the national level, it should align with local maritime and cyber security policies. At the regional level, cyber security requirements should be followed, such as the Directive on Security of Network and Information Systems 2 (NIS2) issued by the European Union (EU) [75]. At the international level, IMO standards should be fulfilled, such as the Casualty Investigation Code for the investigation of cyber incidents [76]. An M-SOC can achieve legal compliance by complying with such regulations.

In a typical ship, the crew is divided into three groups, such as the master, officers, and ratings [77]. It is important to understand the roles and responsibilities of the ship crew for an M-SOC. Therefore, M-SOC staff can be aware of who can operate specific systems onboard the ship. This leads to enabling a more efficient response time during a cyber incident. Moreover, awareness of individuals having remote access to onboard systems is useful. These may include office personnel from the ship operator, technical support providers, and equipment manufacturers. On the other hand, most vessels, except for passenger ships, do not have a dedicated cyber security expert onboard. Moreover, it should also be considered that the sea zone may include not only professional seafarers but also amateur individuals operating their own recreational boats. These individuals may have limited knowledge and experience in handling cyber risks. Last but not least, passengers onboard ships might unintentionally cause cyber vulnerabilities.

In conclusion, an M-SOC represents a central capability for protecting vessels against increasingly complex cyber threats. An M-SOC should be capable of more effective risk prioritization and incident response. Its responsibilities extend beyond technical monitoring to encompass the enhancement of cyber security across the maritime ecosystem. To this end, an M-SOC should improve its situational awareness by considering regulatory frameworks, shipboard systems, human dynamics, and the threat landscape.

5.2. Element 2: Empowering the M-SOC

The objective of this element is to formalize the M-SOC’s authority, scope, and responsibilities through an approved charter [9]. An M-SOC can effectively execute its functions in alignment with legal requirements and institutional mandates. With a written charter, the M-SOC can have the required authority to exist, allocate resources, enforce security measures, and coordinate cyber incident responses.

An M-SOC should operate within a well-defined legal and institutional framework to conduct its mission effectively. The authorities of an M-SOC should be clearly codified because of the complexity of cyber threats and the involvement of multiple stakeholders. Without formal written authorities, an M-SOC may face various issues, such as delays in incident response and jurisdictional disputes. The mission, responsibilities, and scope of the M-SOC should be defined in a charter. These are clearly described in Section 5.1. An M-SOC may have the authority to:

- Communicate with vessels and shore facilities through various channels, including but not limited to AIS, NAVigational TeleX (NAVTEX) broadcasts, e-mail, telephone, and radio communications;

- Monitor, request, store, and analyze communication channels and sensor inputs;

- Initiate and manage actions under established plans;

- Design and operate infrastructures to provide secure information-sharing platforms and communication channels;

- Develop tools to support its ongoing operations;

- Request and review vessel-related cyber security documents, including but not limited to cyber security plans and crew training records;

- Conduct forensic investigations, including interviews with crew members and the analysis of Voyage Data Recorder (VDR) records;

- Mandate cyber security reporting requirements;

- Issue written or verbal advisories, guidance, and recommendations.

The charter issued to the M-SOC should ensure legal backing for these authorities. However, cyber threats are also subject to change over time because of emerging technology. Thus, these authorizations should be reviewed and revised at regular intervals.

Sufficient financial support is required for the effective activities of an M-SOC to maintain its infrastructure, improve technological capabilities, and pay personnel salaries. Potential funding sources are government budgets, contributions from the maritime industry, and funding grants. Governmental organizations are inherently financed by their respective states. A national M-SOC should be financed by the state. For instance, the Danish Maritime Cybersecurity Unit is directly funded by the Danish government. The Maritime Cybersecurity Operations Centre in Singapore receives financial support from the Singapore government. In a similar manner, CGCYBER is funded by the USA. M-SOCs can also generate revenue through specialized cyber security services, such as training programs and consultancy for maritime stakeholders. For example, NORMA Cyber (see Section 2.2.2) was established as a non-profit organization by the maritime industry and sustains its operations through memberships [78] and additional services (e.g., penetration testing) [79]. Finally, M-SOCs may secure funding through grants. To the best of our knowledge, no M-SOC has been established solely through a funding grant.

The authorization and organizational structure of an M-SOC depend on national security priorities and the existing regulatory landscape of the country. M-SOCs can be operated by civil maritime administrations, such as the Danish Maritime Cybersecurity Unit, which operates under the Danish Maritime Authority. In a similar manner, the Maritime Cybersecurity Operations Centre functions under the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA). Additionally, maritime cyber security can also be addressed within military organizations, such as coast guards or naval forces. CGCYBER serves under the USCG. To the best of our knowledge, the existing national M-SOCs operate under a maritime authority rather than a national cyber security center. This structure enables them to work in full alignment with the maritime sector and maintain real-time operational response capabilities.

5.3. Element 3: Designing a Tailored M-SOC Structure

The purpose of this element is to design an M-SOC structure tailored to the specific requests of the maritime stakeholders by considering the need for continuous service availability, interdisciplinary expertise, operational integration with existing maritime infrastructures, and resilience against cyber and physical disruptions [9].

The maritime sector is classified as a critical subsector of transportation, which is recognized by the EU as part of critical infrastructure [80]. Critical infrastructure is defined by the EU as “those physical resources, services, information technology facilities, networks and infrastructure assets which, if disrupted or destroyed, would have a serious impact on the critical societal functions, including the supply chain, health, safety, security, economic or social wellbeing of people or of the functioning of the Community or its Member States” [81].

Various SOC models are available, such as ad hoc security response, distributed SOC, and centralized SOC [9]. The national SOC is another important model which is specifically designed to protect critical sectors from cyber threats. The operation of a national SOC offers several advantages, such as a swift response to cyber incidents and strong collaboration among stakeholders from both the public and private sectors. Moreover, it offers a more economical and sustainable security solution in contrast to distributed or ad hoc models. In this study, we propose a national maritime SOC model, which has been successfully implemented in Singapore, as discussed in Section 2.1.2.

Vessels are exposed not only to conventional cyber threats but also to sophisticated state-sponsored attacks. Moreover, vessels operate 24 h a day. This makes them potential cyber-attack targets outside regular working hours. Because of these factors, vessels should be continuously monitored in real time to mitigate potential cyber threats effectively.

A shift-based work schedule in an M-SOC is essential to maintain continuous operations. Shifts may be organized in 8 h or 12 h rotations and should be frequently changed to reduce the risk of personnel burnout and monotony. Therefore, shifts may change every month or every couple of months to ensure fairness. In addition, ensuring effective handovers between shifts is important for operational situational awareness. These shifts can include formal records in written format to maintain operational continuity.

As in any organization, response teams in an M-SOC can be structured at different levels by considering analysts’ knowledge and experience. This facilitates analysis to be performed more effectively according to their competencies, which are explained in detail in Section 5.4.

In the case of a cyber-attack, expertise from different disciplines may be necessary, including maritime operations, cyber security, maritime law, sea law, and marine insurance. These experts may work for universities or the private sector. The contact details of designated experts should be readily accessible for prompt consultation. Given that these specialists might be in distant locations, it is essential to develop contingency plans for securing remote assistance. To this end, it is necessary to identify secure and reliable communication channels. Moreover, arrangements should be established to ensure their physical attendance.

The M-SOC can share the same building with an existing maritime safety center, such as VTS. This enables rapid access to maritime expertise and also reduces operational costs. However, this approach may cause challenges related to management complexity and authority distribution. Thus, the responsibilities should be well-defined to prevent such issues. Alternatively, an M-SOC can be established in an independent facility. This provides greater control and autonomy to the M-SOC. Despite enhancing operational independence, this model may cause higher initial setup and operational costs. Additionally, potential communication and integration challenges with other maritime units may occur. Thus, the required measures should be taken for seamless coordination.

A secondary facility may be required for use in emergencies, such as fires, natural disasters, or cyber-attacks against the M-SOC. This redundant facility should be located in a different area to prevent location-based risks. Continuous data replication between the primary and secondary facilities should be provided for real-time synchronization. Depending on the budget of the M-SOC, the backup facility can either be a full replica of the primary facility or equipped with only critical systems. Thus, the operational costs of the M-SOC may be reduced.

5.4. Element 4: Recruiting and Developing a Skilled Workforce

The objective of this element is to define the staffing requirements, hiring strategies, and training framework necessary to establish a competent M-SOC team for continuous cyber security monitoring and effective incident response [9].

In the process of founding an M-SOC, it is essential to initially ascertain the required number of analysts. However, many aspects impact the required number of personnel, such as the number and types of ships in the designated sea zone, the frequency of cyber incidents experienced by those vessels, geographical conditions (e.g., currents and shallow waters), the political stability of the state, and the budget. Consequently, the number of staff required for an M-SOC cannot be calculated using a simple ratio or formula. In most cases, the sufficient number and role distribution of staff evolve over time based on operational experience.

At least two analysts should be on duty at all times for continuous cybersecurity monitoring in the designated sea zone. A week consists of 168 h. The total workload per week is 336 h for two analysts. Thus, nine analysts would be required, assuming a standard workweek of 37.5 h per analyst. When factors such as holidays, sick leave, and unforeseen absences are considered, at least 10 analysts would be required to monitor the designated sea zone.

The use of tools that can automatically detect potential anomalies may reduce the number of analysts required. However, such specific tools for an M-SOC are not available on the market. Governments should consider funding the development of these tools to meet the unique needs of the M-SOC. This enables more efficient operations and potentially reduces the reliance on human resources. In addition to analysts, more experts should be hired for different responsibilities, such as incident response, cyber threat intelligence (CTI), regulatory compliance, and so on.

Numerous studies have unveiled the recruitment of qualified personnel as one of the most significant challenges in the cyber security field [82,83]. There are undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral programs in cyber security. Moreover, various certification programs allow individuals to enhance their expertise in the field. However, these educational programs focus on ordinary IT cyber security in general. Specialized training programs are required to respond to cyber-attacks targeting OT systems onboard ships.

Maritime cyber security-specific programs are still quite limited worldwide. To the best of our knowledge, based on program titles and the course lists offered to students, there are currently only two master’s programs globally which are specifically for maritime cyber security [84,85]. Graduates from these specific programs, and individuals who have completed master’s or doctoral theses on maritime cyber security, should be given serious consideration during the recruitment process. Additionally, professionals from the industry who have held responsibilities for maritime cyber security should be considered. Moreover, various naval forces in the world have started to offer maritime cyber security training courses [86]. Therefore, individuals who have transitioned out of naval service can also be considered for hire.

The recruitment strategy should not be limited solely to hiring senior-level personnel. Given the challenges of finding experienced professionals, recent graduates should also be considered for recruitment. These individuals can then be trained in-house and through external programs for the specific needs of the M-SOC. Therefore, it is essential to implement supportive training initiatives. It is important to recognize that no candidate can be expected to be an expert in every subject of maritime cyber security or every system onboard ships. Thus, it would be more effective to consider individuals whose skills complement the existing team in the M-SOC.

Given the various responsibilities to be fulfilled within an M-SOC, it is essential to identify and develop a broad set of skills among team members. These skills should include both maritime and cyber security expertise. Thus, a team could be assembled from individuals in areas, including ship operations (i.e., officers and engineers), cyber security, and maritime law. The following list outlines potential competencies that may be required for effective M-SOC operations. The list is not comprehensive but includes important competencies for an M-SOC:

- Knowledge of reference architectures of ship systems (e.g., components, subcomponents, services, network standards, communication protocols (inc., ship-ship and ship-shore), data flow, connections, dependencies);

- Knowledge of regulations regarding maritime cyber security (e.g., IMO requirements and regional regulations);

- Awareness of cyber security notations issued by flag states and classification societies;

- Understanding of cyber risks associated with shipboard systems;

- Experience with maritime-specific CTI platforms;

- Familiarity with marine operations and shipboard practices;

- Competence in incident investigation and root cause analysis;

- Knowledge of marine insurance policies (e.g., Protection & Indemnity (P&I), Hull and Machinery (H&M) insurances, and the CL380 clause in such policies);

- Proficiency in incident response procedures and protocols;

- Expertise in digital forensics, including the analysis of VDR data;

- Involvement in, or knowledge of, maritime-specific cyber security training programs.

For an effective M-SOC team, seafarers are highly valuable candidates because of their technical knowledge about systems onboard ships and experience in ship operations. Therefore, it would be beneficial for the analyst group in each shift to include at least one expert with a cyber security background and sea experience. Moreover, individuals without sea experience may unintentionally disrupt the ship crew’s rest hours because of their requests. Seafarers have experience in life and work at sea and may prevent such issues.

M-SOC personnel should be trained to work safely on vessels. This may include basic maritime preparedness training such as swimming lessons. It is also important to teach personnel how to walk safely on board, particularly because of the narrow and slippery surfaces often present on vessels. Given that boarding is often done via a pilot ladder, personnel should practice in advance. Such preparations are important to maintain safety and operational effectiveness. Cyber security professionals with seafaring experience typically have such skills and generally do not need additional training.

5.5. Element 5: Establishing a Cyber Incident Response Plan

The objective of this element is to design and implement a comprehensive cyber incident response plan for the M-SOC [9]. According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the incident response lifecycle should comprise four essential dimensions, such as (1) preparation, (2) detection and analysis, (3) containment, eradication, and recovery, and (4) post-incident activity [87].

In the Preparation phase, various tools and resources should be readily available. These include ordinary items, such as printers, laptops, and audio recorders, for which detailed lists are recommended by NIST [87]. However, certain elements can be specifically required for an M-SOC. For instance, real-time access to regional AIS and GNSS data, NAVTEX messages, local weather conditions, radio communications, as well as RAdio Detection And Ranging (RADAR) and camera images of the designated sea zone may be essential. Such data can be retrieved from maritime authorities, such as the VTS. Required memberships for access to relevant online platforms (e.g., Equasis [88], IMO Vega Database [89]) should also be secured in advance.

A dedicated communication list should be available in the cyber incident response plan, particularly for use during incident handling. This list should include the contact details of M-SOC staff, external experts, and stakeholders. The potential stakeholders are outlined in Section 5.9. Moreover, a library should be maintained for the required materials, such as maritime cyber security guidelines, regulations, standards, and circulars. These documents are useful for effective response and decision-making in case of a cyber incident. Incident response plans should be developed to address potential cyber-attacks. Such attacks may include, but are not limited to, AIS spoofing, GNSS jamming, and GNSS spoofing. Developed plans should be reviewed and evaluated frequently with the attendance of relevant stakeholders.

The Detection and Analysis phase begins with notifications from vessels, stakeholders, or the M-SOC’s own monitoring systems. Thus, notification channels should be specified in the incident response plan, such as dedicated e-mails, radio communications, and phone calls. More information about communication channels is given in Section 5.9. Incident response planning also requires the prioritization of cyber incidents by considering their possible safety, environmental, and financial impacts. Multiple cyber incidents may occur in the region simultaneously and require the prioritization of cyber-attacks. For instance, a GNSS spoofing attack could affect several vessels within the designated sea zone. Navigators may remain unaware of the cyber-attack, which may cause a marine casualty (e.g., collision). At the same time, another vessel may experience a cyber-attack affecting its business network. These two incidents are at different severity levels. Given that the GNSS spoofing attack may lead to a marine casualty and impact several ships, it is more critical than the loss of the business network of a ship.

An effective incident response plan should define the information needed to assess the situation. A checklist may be included with questions for decision-making during incident response. For instance, it is important to understand whether a single vessel or multiple vessels are affected by GNSS anomalies, the specific observed anomaly (e.g., time or position errors, or signal loss), and the coordinates of the affected sea zone. It is also necessary to assess whether the affected area shifts throughout the incident, and which GNSS variations are the target of the malicious actor.

Hypotheses should be formed by considering the collected information. Each anomaly may not be caused by a cyber-attack. Given that vessels are complex systems, failures are inevitable. In 2024, a cargo ship collided with the Francis Scott Key Bridge in the USA [90]. The initial claim for this collision was a potential cyber-attack. However, subsequent inquiries found insufficient evidence to confirm the allegation [91]. The case showed that not all marine incidents are linked to cyber threats.

In the Containment, Eradication, and Recovery phase, all information related to the cyber incident should be thoroughly collected before initiating a response. As aforementioned, potential safety, environmental, and financial losses of a cyber-attack should be considered. However, the possible commercial losses of vessels because of potential delays should also be considered while selecting a response method for a cyber incident. For instance, during a GPS spoofing attack, vessels may need to temporarily stop to avoid potential collisions. While this measure is highly effective to prevent marine accidents, the duration of the cyber-attack is uncertain. During this time, vessels may incur significant financial losses. Many modern ships are equipped with multi-GNSS receivers. If the M-SOC recommends switching from GPS to an alternative satellite-based positioning system, such as GLONASS, Galileo, and BeiDou, the impact of the attack may be mitigated. This allows the vessels to continue their voyages safely [92].

A robust Post-Incident Review is essential to improve future efforts. To this end, the M-SOC should perform a thorough review to identify areas for improvement and reinforce preparedness for future cyber incidents. This includes asking critical questions such as: What worked well? What tools were missing, and how can they be ensured for future events? Were the right stakeholders involved? These discussions allow the M-SOC to determine aggregate gaps and inefficiencies that require changes to the response process. If there are repeated issues, there are likely deeper systemic issues. Long-term solutions should be proposed to overcome such issues. Moreover, the review allows the M-SOC in the refinement of response plans based on lessons learned, findings, follow-up actions, and clear success metrics [9].

Review reports may contain analyses of incidents, response processes, and lessons learned. The experience gained offers valuable insights to stakeholders. Thus, reports can be simplified and shared with relevant stakeholders. Sharing such information can improve overall cyber security awareness and coordination capability. This allows faster and more effective responses to similar incidents in the designated sea zone.

5.6. Element 6: Leveraging Cyber Threat Intelligence

The objective of this element is to establish a comprehensive CTI process specifically designed for maritime cyber security [9]. According to NIST, threat intelligence is defined as “threat information that has been aggregated, transformed, analyzed, interpreted, or enriched to provide the necessary context for decision-making processes” [93]. Threat intelligence is essential in preventing cyber-attacks or mitigating their impact. The classical intelligence cycle comprises six phases, including planning, collection, processing, analysis, dissemination, and evaluation [94].

The Planning stage serves to examine the threat landscape of the maritime ecosystem, such as threat actors, their motivations, and cyber-attacks against ships. This phase covers the identification of essential ship systems, such as navigation, main propulsion, and cargo control systems. Then, potential cyber risks of such systems are analyzed systematically. The analysis should also include operational characteristics of ships and the designated sea zone, such as the type (e.g., gas carrier or passenger ship) and gross tonnage of ships, and geographical and traffic conditions. If the Planning phase is not properly defined, it causes the CTI process to be incomplete and ineffective.

The Data Collection stage aims to collect and organize data by considering the necessities identified in the Planning stage. In this stage, relevant data are collected from both internal and external sources, such as open-source intelligence (OSINT), commercial threat intelligence providers, government and regulatory alerts, and industry-specific sources [9]. Data should comprise threat actors, their tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs), and vulnerabilities of ship systems.

Many sources provide information on cyber threats to IT components [95,96,97,98]. However, such sources are highly limited for ship systems. NORMA Cyber [79] and CrowdStrike [99] offer paid threat intelligence services specifically for maritime actors. The Maritime Transportation System Information Sharing and Analysis Center (MTS-ISAC) also promotes and facilitates information sharing between private and public maritime stakeholders through webinars and on-site events [100]. Additionally, France Cyber Maritime [27], NHL Stenden [101], and Marcybersec [102] publish cyber incident details in the maritime domain by relying on publicly available sources. Moreover, the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) releases bulletins including recent cyber incidents [103]. GPSJam systematically tracks GNSS interface issues [104]. The USCG Navigation Center also lists GPS interferences reported to them [105]. Occasionally, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) reports GPS and AIS interferences [106]. Additionally, various reports [107,108,109,110] and scientific papers [111,112,113,114] publish cyber-attacks and vulnerabilities for maritime stakeholders and researchers. State-sponsored cyber-attack claims have been reported in the maritime industry [74]. Therefore, Advanced Persistent Threat (ATP) activities should be monitored on relevant platforms (e.g., MITRE-ATT&CK [115]). Last, under the Cyber Resilience Act (CRA) [116], as of 11 September 2026, manufacturers will be required to report any actively exploited vulnerabilities in their products and any severe incidents affecting the security of those products [117]. For an M-SOC, these reports will provide highly valuable information.

The Processing stage of the CTI is to clean and format the collected data. The collected data should be accurate and sufficient for analysis. Therefore, the data are evaluated for validity and reliability. Insufficient, duplicated, and irrelevant information is also removed in this stage. Moreover, trends, relationships, and patterns within the data are identified. The findings should be properly interpreted and frequently updated by considering changing conditions. Consequently, all findings should be reported in a clear format.

In the Analysis stage, all findings and interpretations are deeply evaluated by analysts to understand the consequences of possible risks affecting systems. The effectiveness of this stage depends on the data accuracy and the expertise of analysts in the M-SOC. Analysts should focus on emerging threats, TTPs of threat actors, and vulnerabilities of systems onboard ships. During this evaluation, not only cyber security experts but also maritime professionals should be consulted because of their operational experience, that facilitates a better understanding of the severity of cyber risks. Moreover, they may suggest applicable risk mitigation measures.

The Dissemination stage is to provide actionable intelligence to relevant stakeholders so that they can take effective precautions against identified cyber threats and vulnerabilities. To maximize the effectiveness of this stage, the intelligence should be specified by considering the needs of each stakeholder. Consequently, the relevant information is presented in a format that the stakeholder can easily understand and take action on.

The Traffic Light Protocol (TLP) [93,118,119] can be implemented for the sharing of sensitive information. This protocol enables appropriate information sharing while maintaining the confidentiality of more sensitive data. The TLP is currently used in the maritime industry for information exchange. For instance, the USCG’s Maritime Cyber Bulletin [120] and France Cyber Maritime’s Annual Threat Report [108] are released using the TLP Clear designation.

The last stage of the CTI process is Evaluation. In this phase, the effectiveness of the entire intelligence cycle is assessed. This comprises examining the accuracy of the collected data, the quality of the analysis, and the appropriateness of the dissemination means. To this end, an M-SOC should gather feedback from all stakeholders. This allows the operational value of the intelligence to be effectively evaluated.

5.7. Element 7: Collecting Relevant Data

The objective of this element is to identify and collect data from various sources through Shipboard and Seaborne Data Collection approaches [9]. Accessing relevant data sources is crucial for M-SOC to perform its mission and responsibilities. Thus, M-SOC can properly identify potential cyber threats, assess vulnerabilities, and respond to cyber-attacks. To this end, an M-SOC requires a clear legal framework for the collection, storage, access, analysis, and erasure of the data. For instance, a scientific paper revealed that vulnerabilities in Very Small Aperture Terminal (VSAT) on ships could be exploited to monitor data flow [121]. However, such eavesdropping could be illegal if conducted by an M-SOC without appropriate legal authorization.

Depending on its responsibilities, the M-SOC can access data through two essential approaches, namely Shipboard Data Collection and Seaborne Data Collection. Shipboard Data Collection refers to the data collection from ship systems. Analysts should board the vessel to collect data from onboard systems. This approach is particularly useful for post-incident assessments.

Shipboard Data Collection involves the collection of critical data directly from vessels to analyze a cyber incident. This data covers not only IT systems onboard ships but also their OT systems. OT systems, such as navigation, propulsion, communication, and cargo handling, often generate their own logs for monitoring the integrity and performance of these systems. These OT components may operate through specialized communication protocols (e.g., IEC 61162-460 [122]) [123], which differ from traditional IT networks. Moreover, the limited availability of dedicated security monitoring tools for OT systems leads to challenges in detecting anomalies or cyber threats within these components [9].

A VDR or Simplified Voyage Data Recorder (S-VDR) on board is compulsory for many ships [124]. These components record critical operational data, such as ship position, speed, heading, and RADAR data [125,126], and make it possible to analyze cyber incidents. They also record crew communications on the bridge. Therefore, crew interactions and their decision-making processes during a cyber-attack can be investigated. According to the Casualty Investigation Code issued by the IMO, if fitted, the VDR or S-VDR data should be collected and analyzed as part of the forensic process following a marine casualty or marine incident [76]. Many papers in the literature reveal the importance of VDR for forensic analysis [127,128,129,130].

Some systems onboard, such as the main engine lubrication system [131], may also be accessed remotely from shore facilities. Thus, logs of remote access are significant for an incident investigation. Shipboard Data Collection could be highly beneficial for post-incident assessments in particular. These diverse data sources, which include IT and OT logs, audio and video records (e.g., Closed-Circuit TeleVision (CCTV) records), and remote access logs, can facilitate the M-SOC to completely understand the incident and propose mitigation measures against similar cyber threats in the future.

Another collection approach is Seaborne Data Collection, which refers to the remote collection of information from the designated sea zone. The M-SOC can detect potential cyber-attacks by monitoring real-time data flows in the zone. Seaborne data sources may include AIS, GNSS, and NAVTEX message traffic, camera feeds, and RADAR data.

AIS is a vital component onboard ships to prevent possible collisions. However, scientific studies have revealed the cyber vulnerabilities of AIS [132,133,134], and real-world incidents have confirmed these risks. For instance, thousands of fake vessels were generated within seconds near Elba Island in December 2019 [135]. The disruption or manipulation of AIS data may endanger the navigational safety of ships. Thus, continuous monitoring of AIS message traffic in the designated sea zone is required to detect any potential cyber-attacks.

Similarly, GNSS is one of the critical systems onboard for the safe navigation of ships. However, GNSS is also vulnerable to spoofing [136] and jamming [92] attacks. Four variations in GNSS called Beidou, GPS, GLONASS, and Galileo [123] serve globally. Any of which could be targeted by a malicious actor. Therefore, all available GNSS variants should be monitored to detect potential anomalies. In case of a potential attack, vessels in the designated sea zone can be advised to switch to an unaffected GNSS variant. Furthermore, Differential GNSS (D-GNSS) signals provide improved positioning accuracy through correction data. Given that malicious actors may prefer to attack D-GNSS, it should also be monitored. If an anomaly is detected in D-GNSS transmissions, vessels may be advised to temporarily disable the D-GNSS function of their receivers.

Furthermore, NAVTEX is a communication device from shore to ship. It should be monitored to ensure the authenticity and reliability of the messages transmitted. A coordination mechanism between maritime authorities and the M-SOC should be established before the transmission of official NAVTEX messages. Therefore, such coordination mechanisms can lead to the detection of unauthorized broadcasts by the M-SOC.

In addition to signal and message monitoring, real-time camera and RADAR feeds from shore-based surveillance systems can improve the situational awareness of the M-SOC. Many countries operate such surveillance systems through VTS facilities. Analysts can detect or verify potential anomalies with the support of established data-sharing mechanisms between the VTS and the M-SOC.

5.8. Element 8: Developing M-SOC Tools

The objective of this element is to provide M-SOC-specific tools that enable the monitoring of data sources and the detection of cyber-attacks targeting vessels [9]. Similar to any SOC, an M-SOC also requires various monitoring and intrusion detection tools to effectively perform its functions. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are currently limited solutions in the market specifically to address the unique operational requirements of a national M-SOC. Therefore, such tools need to be developed specifically for this purpose.

In particular, implementing Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) for the specific needs of M-SOC is required. These systems should be capable of analyzing ship-specific traffic patterns and communication protocols. Various detection approaches can be conducted, such as rule-based, specification-based, and AI-driven methodologies to identify both known threats and previously unseen anomalies [137,138]. During the design of such IDS solutions, the unique constraints and operational characteristics of systems onboard should be considered, such as intermittent connectivity, the use of proprietary protocols, and the prioritization of navigational and operational safety. In the following paragraphs, various IDS applications are proposed.

AIS spoofing and abnormal ship traffic in the designated sea zone can be detected by an M-SOC. To achieve this, the M-SOC should have access to real-time AIS data streams, historical vessel movements, and analysis engines based on rule-based logic. The development of such a tool is essential for the M-SOC. Therefore, it would enable the identification of suspicious activities, including AIS manipulation, unusual route deviations, abnormal speed profiles, and unauthorized area entries [139].

GNSS traffic should be monitored with detection tools. Therefore, any interruption caused by the GNSS jamming attack could be detected automatically. Currently, few systems are available on the market for ship operators to detect GNSS spoofing and jamming attacks [140,141]. These products can be utilized; however, their effectiveness should be evaluated for use by the M-SOC. Moreover, additional tools can be developed. For the detection of GNSS spoofing attacks, fixed reference points can be identified along the coastline within the designated sea zone. The coordinates of these points are continuously monitored by considering all available GNSS variants. In case of a GNSS spoofing attack, a monitoring system can detect any deviations by comparing these fixed coordinates and their live coordinates. Expanding the number of fixed reference points in the designated sea zone can improve the effectiveness of the system.

An effective method for detecting ghost (non-existent) vessels involves the automatic comparison of target detections from shore-based RADAR systems (e.g., RADARs in VTS facilities) with position reports broadcast via AIS [142]. If an AIS message indicates the presence of a vessel that cannot be detected by RADAR within the designated sea zone, the system can flag this as a potentially fabricated target. This verification enables the identification of ghost ships. However, this method is only applicable to vessels located within the operational range of the RADAR system. Targets outside RADAR coverage should be excluded from the comparison to avoid generating false positives. Furthermore, because of minor discrepancies between RADAR-based detection and AIS positioning, a tolerance of approximately 20 m should be incorporated [143]. The detection tool should allow this threshold to be configured based on operational requirements and environmental conditions.