Abstract

Thermal anomalies within the lithosphere are an important manifestation of mantle plume–lithosphere interaction. Early studies primarily concentrated on the presence of the Hainan plume and its surface responses, with comparatively little research devoted to its hotspot track and lithospheric-scale thermal responses. Based on high-resolution seismic data, we reveal that, although a low-velocity anomaly caused by the plume exists in the asthenospheric mantle beneath Hainan Island (>70 km), no such anomaly is observed in the lithospheric mantle (40~70 km). In comparison, within the same depth slice, a low-velocity body in the lithospheric mantle (40~70 km) is observed beneath the Jiangxi–Fujian boundary, accompanied by high-surface heat flow, and its location is shifted approximately 1300 km to the northeast relative to the low-velocity anomaly in the asthenosphere located under Hainan Island. To explain the spatial offset of the low-velocity anomalies, we constructed a three-dimensional geodynamic model aimed at investigating the lithospheric thermal evolution during interaction between the stationary Hainan plume and the moving South China Plate. The findings indicate that the lithospheric low-velocity zone beneath the Jiangxi-Fujian region may be a consequence of the migration of the lithospheric thermal anomaly caused by the Hainan plume with the South China Plate.

1. Introduction

Hotspots are areas of volcanic activity that are not directly linked to tectonic plate boundaries and are usually characterized by unusually elevated heat flow [1]. Numerous volcanic hotspots show systematic age progression along the direction of tectonic plate movement, forming linear volcanic chains that are generally termed hotspot tracks [2,3,4]. A representative example is the Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain, which is associated with the Hawaiian hotspot [5].

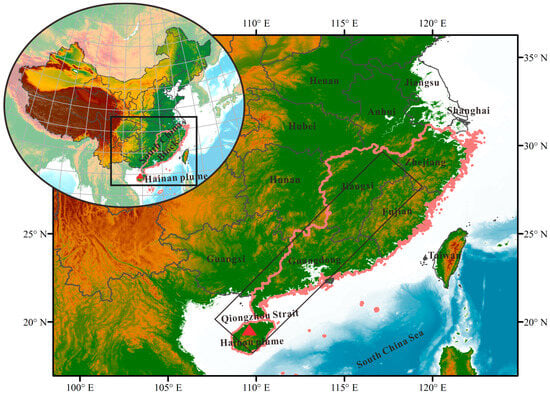

Hainan Island is situated at the southwestern edge of the southeast coast of China, and is separated from the South China Block by the Qiongzhou Strait (Figure 1). Seismic imaging has uncovered a columnar low-velocity body under Hainan Island, which is believed to extend into the deeper mantle. The radius of this structure is estimated to range between 40 and 80 km [6,7,8]. Petrological and seismological studies estimate the excess temperature of the plume ranges from 140 to 200 K [9]. Geochemical data suggest that the ocean island basalts (OIBs) found on Hainan Island are likely sourced from deep regions within the Earth’s interior, potentially originating from the lower mantle [10,11,12]. In summary, multiple independent studies from seismic tomography, petrology and seismology, and geochemistry all provide robust evidence for a mantle plume located underneath the Hainan area.

Figure 1.

The geographical location of the Hainan mantle plume and the study area. The red triangle indicates the position of the Hainan plume, and the pink line outlines the boundary of the study area.

Compared to oceanic plates, hotspot tracks on continental plates are more difficult to observe [4,13,14], primarily due to the absence of related surface features like volcanic activity and elevated topography on the continent. Geochemical studies suggest that a series of OIBs, originating from a mantle plume, are distributed in a NE-SW alignment along the southeastern margin of China. These rocks exhibit a distinct age progression, with the oldest samples found in the northeast and the youngest towards the southwest. Geophysical studies have revealed a linear anomaly characterized by high seismic velocity located beneath the crust in the southeastern coastal area of China, specifically in the northeastern section of Hainan Island [15]. Additionally, the southeast coast of China is characterized by overlapping linear belts of high heat flow and thin crust, which coincide with the seismic velocity anomaly belt. This correlation suggests a hotspot trajectory linked to the Hainan plume [16,17,18]. Nevertheless, prior research has primarily centered on the presence of the Hainan plume and its surface manifestations, with limited evidence supporting related hotspot tracks. This study aims to bridge this gap by investigating the origin of this offset through integrated seismological analysis and three-dimensional dynamical modeling.

Based on high-resolution data from seismic waves and surface heat flow data, we systematically analyzed the spatial distribution characteristics of deep seismic velocities of the southeastern margin of China, revealing the spatial distribution of the lithospheric thermal structure. Subsequently, we employed a three-dimensional modeling approach to explore the thermal and mechanical interactions between the moving South China Plate and the stationary Hainan plume, using heat flow data as a key constraint, and obtained the critical geodynamic parameters of the Hainan plume (plume tail radius and excess temperature), as well as the evolutionary process of the lithospheric thermal structure through inversion. On the basis of this, we revealed the causative mechanisms of seismic velocity anomalies and thermal anomalies within the lithosphere of southeastern China. Finally, on the basis of the cross-validation of multidisciplinary data and results from numerical modeling, we proposed “bottom-up” heat transfer modes for the southeastern margin of China and explored the enrichment patterns of geothermal resources in this area.

2. Seismic Velocity Structure and Thermal Implications

Seismic wave velocities, particularly S-wave velocities, exhibit a negative correlation with temperature. Rising temperatures reduce the shear modulus and increase the ductility of rocks, leading to a significant decrease in S-wave velocity. Therefore, anomalies with low velocities are typically linked to tectonic activities that occur at high temperatures, such as plume activities [19,20,21,22]. We aim to investigate the thermal anomalies within the lithosphere of the southeastern coastal region of China and their spatial correlations with surface heat flow anomalies and seismic velocity anomalies by analyzing the spatial distribution of seismic wave velocities.

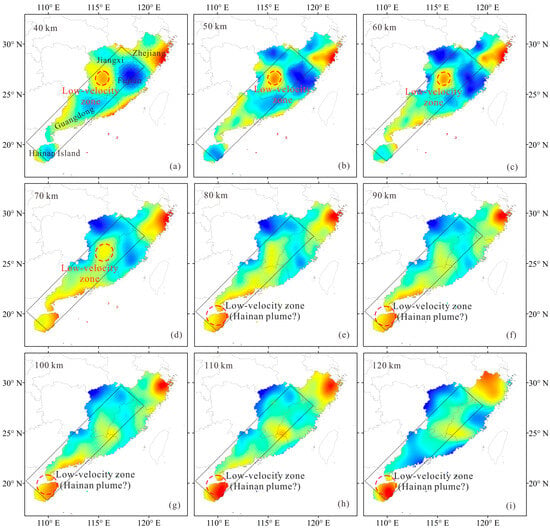

The seismic velocity data are derived from the China Seismological Reference Model CSRM-1.0 (http://chinageorefmodel.org), which is a high-resolution seismic model [23,24]. The dataset covers the region from 68° E to 134.8° E and from 17° N to 53.8° N, with a lateral grid spacing of 0.2° × 0.2° in the North–South seismic belt and the mountainous regions of North China, and 0.4° × 0.4° in other regions. The vertical resolution is 0.5 km. We extracted Vs data from the CSRM-1.0 model for the South China–southeast coastal region within a depth range of 40~120 km, and constructed S-wave velocity maps within the same depth slice at 10 km depth intervals (Figure 2). The thickness of the crust along China’s southeast coast ranges from approximately 30 to 35 km, with a lithospheric thickness of about 70 to 80 km [16,25]. Therefore, based on the velocity data, we analyzed the velocity distribution characteristics of the lithospheric mantle and the shallow portion of the asthenospheric mantle in this area. The velocity analysis reveals a low-velocity zone (LVZ) within the lithospheric mantle located underneath the Jiangxi–Fujian (Gan-Min) region, extending from 40 to 70 km depth, with shear wave velocities 2~4% lower than the reference values (4.5~4.6 km/s) and 2~3% lower than those beneath Hainan Island within the same depth slice (Figure 2a–d). However, at depths greater than the lithospheric mantle (>70 km), a significant low-velocity anomaly is detected beneath Hainan Island (Figure 2e–i), with shear wave velocities about 1.8% lower than those beneath the Gan–Min region within the same depth slice. This anomaly may indicate the upwelling of the Hainan plume.

Figure 2.

Horizontal sections of S-wave velocity at various depths along the southeastern coast of China. (a) S-wave velocity at a depth of 40 km; (b) S-wave velocity at a depth of 50 km; (c) S-wave velocity at a depth of 60 km; (d) S-wave velocity at a depth of 70 km; (e) S-wave velocity at a depth of 80 km; (f) S-wave velocity at a depth of 90 km; (g) S-wave velocity at a depth of 100 km; (h) S-wave velocity at a depth of 110 km; (i) S-wave velocity at a depth of 120 km.

Early studies generally suggested that low-velocity zones are closely associated with thermal anomalies or partial melting [20,21]. According to Goes, Govers and Vacher [22], a rise of about 100 °C in temperature results in a decrease of roughly 0.7~4.5% in shear-wave velocity (Vs). Mantle plume–lithosphere interactions typically result in elevated lithospheric temperatures, which in turn lead to a decrease in shear-wave velocity (Vs). However, no notable low-velocity anomaly is observed within 40 to 70 km depth underneath Hainan Island, nor does the surface exhibit widespread high heat flow anomalies (Figure 3), indicating that the lithospheric thermal structure in this region may not be substantially affected by the Hainan mantle plume. Compared with Hainan Island, the lithospheric low-velocity body beneath the Gan–Min region shows a good spatial correspondence with surface high heat flow (Figure 3). Based on the analysis of the spatial patterns of low-velocity zones and heat flow anomalies located in southeastern China, we suggest that the thermal anomaly in the lithosphere caused by the Hainan plume may have shifted in a northeast direction. This alteration in heat transfer could be associated with the tectonic plate movements occurring over the Hainan plume.

Figure 3.

Distribution of lithospheric seismic velocity and surface heat flow contours in southeastern China. From top to bottom, the figure illustrates the heat flow at the surface, and shear wave velocity (Vs) at depths of 40 km, 50 km, 60 km, and 70 km within the lithospheric mantle. Red circles mark the positions of low-velocity zones in the lithospheric mantle, whereas black circles denote regions with high heat flow.

3. Methods

3.1. Theoretical Framework

To investigate the spatial migration mechanism of low-velocity anomalies along the coastal South China and its thermal effects, this study develops a novel three-dimensional thermo-mechanical coupled numerical model, building upon previous two-dimensional modeling work [18]. In contrast to the 2D cross-sectional model, our model is designed to reconstruct the 3D lithospheric structure of the entire study region (covering both the NW-SE direction and lateral extent). This approach allows for a more realistic simulation of the spatiotemporal evolution of Hainan plume upwelling and its interaction with the lithosphere. Three-dimensional modeling enables direct analysis of the spatial correspondence between thermal anomalies and seismic velocity anomalies in 3D, and facilitates quantitative assessment of heat flow perturbations along the NW-SE direction and on a regional scale—capabilities beyond the reach of 2D profile models. Furthermore, this study utilizes the spatial distribution of observed surface heat flow anomaly zones along the southeastern coast as a key constraint. Through iterative inversion, more accurate parameters for the Hainan plume (e.g., radius) are obtained, ensuring that model inputs better reflect actual geological conditions and thereby enhancing the reliability of the simulation results.

The model is constructed within the COMSOL Multiphysics 6.0 environment, with its principal advantage being the accurate three-dimensional representation of mantle plume upwelling and the associated multidimensional heat transfer processes, and provides a more direct and controllable modeling environment for such problems. The model algorithm is grounded in an established finite element framework [26], incorporating a three-dimensional geometric domain and boundary conditions. Through the concurrent resolution of the interrelated governing equations pertaining to mass, momentum, and energy conservation, the study achieves a three-dimensional quantitative simulation of the lithospheric-scale thermo-mechanical system in the coastal area of southeastern China. The governing equations are outlined as follows:

The temperature is represented by T, while denotes the density. The term u signifies the velocity, and t corresponds to time. Dynamic viscosity is indicated by , g refers to gravitational acceleration, stands for specific heat, k represents thermal conductivity, and A indicates the rate of heat generation.

This model adopts a standard approach for numerical mantle convection simulations by treating mantle rock viscosity as strongly temperature-dependent [27,28,29,30], and this constitutive relationship is based on early theoretical foundations and has been validated by numerous studies, confirming its reliability [31,32,33].

The reference viscosity is denoted as , the activation energy is represented by , signifies the gas constant, and refers to the reference temperature.

3.2. Model Setup

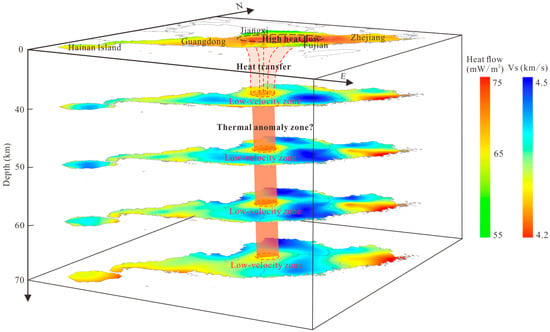

The dynamic framework of this model is driven by the northeastward movement of the South China Plate since 80 Ma. Based on constraints from OIB ages, the plate motion rate is established at 1.8 cm per year to simulate the evolution process since 80 Ma. The model’s geometric space is defined with dimensions of 4000 km in length, 800 km in width, and 400 km in depth, ensuring that boundary effects are minimized (Figure 4). The initial crust and lithosphere thicknesses are established at 35 km and 70 km, respectively. The top boundary is defined with a velocity condition that simulates the movement of tectonic plates. Specifically, it includes a horizontal velocity component of 1.8 cm per year directed along the x-axis, while there is no movement in the y-axis, indicating a stable vertical position. The model allows free flow in the vertical direction, and the velocity of the lower boundary in the horizontal direction is set to zero.

Figure 4.

The initial setup of the temperature field.

The thermal structure of the model is influenced by the initial field, boundary conditions, and mantle plume parameters. At the upper boundary of the model, the temperature is fixed at 0 °C, whereas, at the lower boundary, it is established at 1300 °C, corresponding to the potential temperature of the asthenospheric mantle [25]. Both sides are adiabatic boundaries. The construction of the initial temperature field takes into account both lithospheric heat conduction and radiogenic heat generation effects (Figure 4). Given the widespread development of granite in South China, we establish the initial field by solving the one-dimensional steady-state heat conduction equation and assessing the contribution of heat generation from granite. This initial field is then calibrated using regional observed heat flow values. The key parameters of the mantle plume are based on the range given by previous studies, that the excess temperature associated with the Hainan plume determined by petrology and seismology falls within the interval of 140 to 200 K, and a radius range of 40 to 80 km, aiming at reproducing the measured heat flux distribution in this region, the inversion optimization is carried out.

z represents depth, indicates the heat flow at the surface, denotes the heat production rate in the upper crust, refers to the heat production rate within the middle and lower crust, signifies the upper crust thickness, is the temperature at the Moho, and stands for the reference temperature, which is 1300 °C. Table 1 provides the values of all parameters utilized in the model, sourced from prior research [6,7,9,15,34,35,36,37].

Table 1.

Reference values for the model parameters.

4. Modeling Results

4.1. Evolutionary Characteristics of Lithospheric Thermal Anomalies

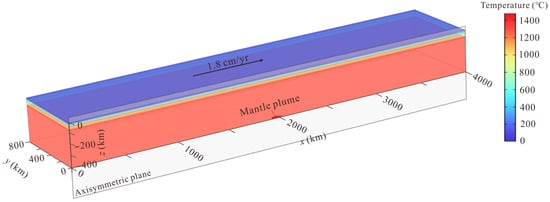

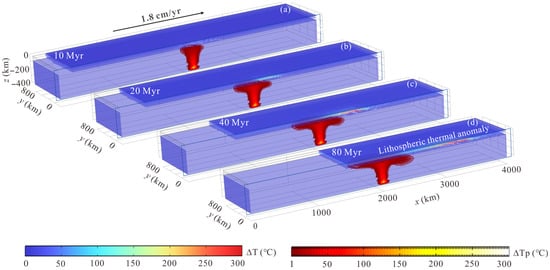

The modification of lithospheric thermal structure by plume activity in linear volcanic chain regions is a dynamic process regulated by plate motion. Numerical modeling indicates that, when material from a high-temperature plume ascends to the lithosphere’s base, a localized thermal anomaly initially develops in the contact region (Figure 5a). Subsequently, the hot material undergoes lateral spreading due to shear, causing the thermal anomaly to progressively expand in the same direction as the movement of the plate over time (Figure 5c,d). By 80 Myr, the anomalous zone expands to approximately 1600 km, evolving into an asymmetric structure. Its leading edge exhibits higher temperatures, about 30% above the background geotherm, and triggers ductile flow at the lithosphere’s base (Figure 5). The distribution characteristics of lithospheric thermal anomalies induced by a mantle plume differ significantly under moving and stationary plate conditions. Under a stationary plate, heat transfer is dominated by vertical conduction, typically forming a symmetrical thermal dome centered on the mantle plume.

Figure 5.

The evolutionary process of the lithospheric thermal structure. The white arrows represent ductile flow at the lithosphere’s base. ∆T denotes the thermal anomaly temperature of the lithosphere, and ∆Tp denotes the excess temperature associated with the mantle plume. (a) The thermal anomaly temperature field at 10 Myr; (b) The thermal anomaly temperature field at 20 Myr; (c) The thermal anomaly temperature field at 40 Myr; (d) The thermal anomaly temperature field at 80 Myr.

The sustained high temperatures at the leading edge of the thermal anomaly zone are essentially the result of a positive feedback loop between thermal input and rheological weakening. Thermal input from the mantle plume reduces the viscosity at the lithospheric base by 2 to 3 orders of magnitude, triggering rheological weakening and viscous flow, thereby leading to a significant temperature increase at the leading edge of the thermal anomaly zone. The high temperatures at the leading edge further enhance flow efficiency, increasing the vertical heat transport rate by 20~30%. The modeling confirms that the heat input–rheological weakening feedback mechanism drives the progressive intensification of the thermal anomaly along the plate motion direction, ultimately producing a thermal structure with spatial decoupling between the lithospheric thermal anomaly center and the mantle plume source region (Figure 5d).

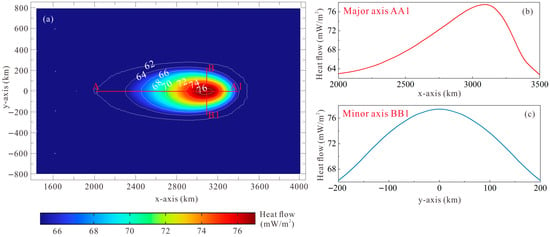

4.2. Evolution Characteristics of Heat Flow

The state of plate motion serves as the dominant control on how surface heat flux responds to plume heat input. Under a stationary plate condition (velocity is 0 cm/yr), vertical heat conduction dominates, forming an axisymmetric circular heat flow anomaly zone, with heat flow value decreasing outward from the center. When the plate moves horizontally, lateral heat advection stretches the anomaly zone into an elongated ellipse, with its major axis aligned parallel to the direction of the plate’s movement. Quantitative modeling indicates that the length of the major axis increases with plate motion, while the minor axis is mainly controlled by thermal diffusion and is positively correlated with the plume radius and temperature. The region of heat flow anomalies located along southeastern China is roughly elliptical, extending approximately 1500 km along the SW–NE direction for the major axis and about 400 km along the NW–SE direction for the minor axis. We used the spatial dimensions of the heat flow anomaly zone as a constraint to invert the model results, which indicate that the Hainan plume possesses a radius of roughly 50 km and a tail excess temperature of 180 °C, and this result is in close agreement with other geophysical and geochemical findings.

Numerical modeling quantitatively reveals that the leading edge of the heat flow anomaly zone exhibits significantly high heat flow, with peak values about 17% higher than the background heat flow. Heat flow value decreases gradually along the long axis (AA1) toward the direction of the mantle plume (trailing edge), and the decline rate increases with the growing distance from the leading edge (Figure 6b). At 80 Myr, the heat flow gradient in the leading-edge region decreases by 1.0 mW/m2 per 100 km, while, in the trailing-edge region, the gradient reaches 1.5~2.0 mW/m2 per 100 km. Under the dynamic control of plate movement, the zone of heat flow anomalies induced by plume activity is systematically displaced relative to the plume source region, with the high-heat-flow area shifted 1300~1500 km from the vertical projection of the mantle plume (Figure 6a). Along the short axis (BB1), heat flow decreases outward from the center of the anomaly zone and is symmetrically distributed on either side of the long axis (Figure 6c).

Figure 6.

(a) Heat flow anomalies distribution resulting from plume activity at 80 Myr. White solid lines denote heat flow contours, and AA1 and BB1 represent the major and minor axes of the heat flow anomaly region, respectively. (b) Heat flow variation curve along the major axis. (c) Heat flow variation curve along the minor axis.

5. Discussion

5.1. Origin of the Thermal Anomaly Offset

A complete comprehension of the lithospheric thermal characteristics in southeastern China serves as the key basis for revealing the deep dynamic processes and their surface manifestations. The coastal area in the southeast of China is distinguished by a highly complex geological background. Early studies have proposed multiple geodynamic models, including intraplate rifting, subduction and rollback of the paleo-Pacific Plate, and continent collisional orogeny, to explain the widespread magmatism, high heat flow, and lithospheric thermal anomalies in this area [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. Nevertheless, these models still have limitations. For example, the model of intraplate rifting fails to clarify the inland orogeny within the South China Plate [50]. The paleo-Pacific subduction and rollback model does not sufficiently address the spatial displacement of lithospheric thermal anomalies along the southeastern coast. The continent–continent collision model encounters difficulties in elucidating the distribution of rocks in this area [51,52]. Additionally, the movement direction of the South China Plate has been a topic of contention since the late Cretaceous period. For instance, Lithgow-Bertelloni and Richards [53] suggested that the Eurasian plate has been moving in a northeast direction since 20 Ma. However, subsequent studies have yielded inconsistent conclusions. Zahirovic, et al. [54], Seton, et al. [55], and Müller, et al. [56] proposed southeast or northeast movement patterns, respectively. This divergence indicates that the current research on the kinematic characteristics of the South China Plate remains inadequate, and the findings of this investigation offer key evidence to support its continuous northeastward movement.

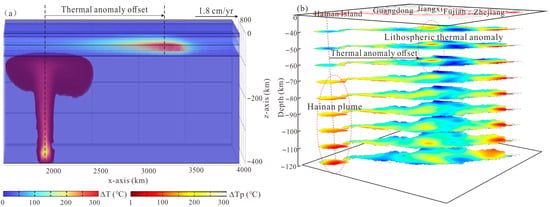

The S-wave velocity analysis in this paper indicates that the prominent thermal anomalies in the Gan–Min region primarily originate from the lithospheric mantle rather than deeper sources, consistent with other geophysical observations [57,58]. The S-wave low-velocity zone clearly reveals localized thermal anomalies within the lithospheric mantle underneath the Gan–Min region, which diminish or disappear near the lithosphere’s base. Meanwhile, significant thermal anomalies at the asthenospheric scale are mainly concentrated beneath Hainan Island. This spatial offset between lithospheric and asthenospheric thermal anomalies is key to understanding the thermal framework of the lithosphere along the southeastern coastal region of China.

Numerical modeling further indicates that this spatial offset of thermal anomalies may be connected to the sustained northeastward motion of the South China Plate situated above the Hainan mantle plume (Figure 7a). The ongoing northeastward motion of the Block has caused the lithosphere to shift horizontally relative to the Hainan plume beneath it. The lithospheric mantle (for instance, the Gan-Min region) beneath the trajectory of motion underwent thermal input or erosion due to the Hainan plume, which led to the shallow thermal anomalies and low-velocity zones observed at the lithospheric scale. As the lithospheric block shifts away from the Hainan plume source, the asthenospheric thermal anomaly beneath it diminishes, while the plume remains beneath Hainan Island, forming a thermal anomaly and low-velocity zone in the asthenospheric mantle underneath Hainan Island (Figure 7b). Therefore, the movement of the South China Plate toward the northeast over the Hainan mantle plume provides a key dynamical mechanism to clarify the spatial offset (the separation between lithospheric thermal anomalies and the asthenospheric heat source) of lithospheric thermal anomalies and the low-velocity body in the southeastern coast.

Figure 7.

Spatial offset between lithospheric thermal anomalies and the Hainan plume. ∆T represents the lithospheric thermal anomaly temperature, and ∆Tp represents the excess temperature associated with the mantle plume. (a) The thermal anomaly temperature field results obtained from model calculations; (b) The red circles indicate the distribution of the low-velocity zones.

Along the southeastern coastal region of China, multiple pieces of evidence, including overlapping linear belts of high heat flow and thin crust, the mantle plume-derived OIBs, and the spatial offset of the low-velocity body, jointly support this dynamic mechanism. According to Zhang, He, Chen and Guo [18], the linear high heat flow belt is an important surface manifestation of the Hainan plume. Moreover, in this area, a linear thin crustal belt trending southwest to northeast has been identified, with its spatial arrangement closely corresponding to that of the linear high heat flow zone. Its development may have been shaped significantly by the interaction of the plume and the lithosphere. According to Liu, Chen, Leng, Zhang and Xu [15], the erosive influence of the mantle plume on the crust is enhanced by the weakness present in the lower crust. In China’s southeastern coastal zone, the crust progressively becomes thinner as one moves southwest [59], a phenomenon that could be associated with the strength characteristics of the lower crust in this region [60].

A key point to emphasize is the emergence of a variety of OIBs sourced from mantle plumes along overlapping linear belts of high heat flow and thin crust, where the ages of the basalt progressively decrease as one moves southwestward [61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. This not only offers petrological proof of the movement of the South China Plate as it interacts with the Hainan mantle plume but also limits the onset period of this activity to approximately 80 Ma. The start time of the model (~80 Ma) corresponds to the earliest episode of OIB-type basalt eruption along the coastal South China (Fujian, ~80–90 Ma). Subsequently, Guangdong moved above the Hainan mantle plume, coinciding with major Cenozoic tectonic events such as the opening of the South China Sea (~30 Ma) [69]. Crucially, the widespread Cenozoic to Quaternary alkaline basalts in the northern South China Sea margin and around Hainan Island (e.g., [70]) exhibit enriched geochemical signatures that consistently indicate a contribution from the Hainan plume source. These volcanic rocks, which range from ancient to recent and show spatial migration, form a comprehensive observational dataset. This dataset validates the fundamental evolutionary scenario depicted in our model, namely, the long-term presence, sustained activity, and lithospheric interaction of the Hainan plume.

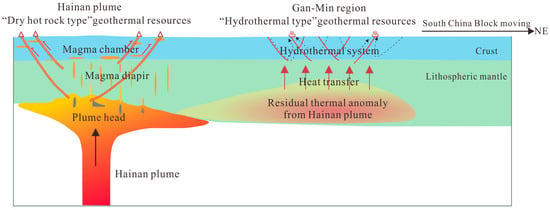

5.2. Geothermal Resources Distribution

The heat flow measurements in Fujian and Jiangxi are significantly higher than the average values (65 mW/m2) in the southeastern coastal areas. The most recent heat flow measurements suggest that the values in this area vary between 70 and 220 mW/m2 [17]. Among them, heat flow exceeding 80 mW/m2 is distributed along the Fault zones, which are closely related to the Yanshanian granitic with high radiogenic heat production on both sides of the faults [71,72]. Extreme high heat flow greater than 96 mW/m2 is mostly associated with deep hydrothermal circulation systems [73]. Once shallow disturbances, such as high-radiogenic granitic and hydrothermal activities, are omitted, the heat flow within this area varies between 70 to 77 mW/m2, representing an increase of 8 to 18% compared to the southeastern coast’s background value.

On the basis of the spatial offset of low-velocity zones and the distribution of heat flow anomalies, we propose a coupled geodynamic model of mantle plume activity and plate motion. This model illustrates that the lithosphere’s thermal anomaly, along with the low-velocity anomaly observed in the Gan–Min area, is caused by thermal contributions from a combination of the Hainan plume and the ongoing northeastward movement of the South China Plate since 80 Ma. The Gan–Min region is characterized by well-defined faults and a significant abundance of hot springs, with hydrothermal geothermal resources being the predominant type [74]. The fundamental elements for the formation of a hydrothermal circulation system are conduits (faults), fluids, and heat sources. In the Gan–Min region, residual heat from the Hainan plume (lithospheric thermal anomalies) and radiogenic heat sources may constitute the primary driving forces of the hydrothermal circulation system (Figure 8). Numerous deep-seated faults cutting down to the Moho or the lithospheric scale have developed on Hainan Island, including the Maniu–Puqian, Wangwu–Wenjiao, and Jiusuo–Lingshui faults. Moreover, significant volcanic formations from the Quaternary period have emerged, positioning Hainan Island as one of China’s most recently active volcanic areas [75,76,77]. Initial research suggests that the geothermal resources of Hainan Island are primarily of the hot dry rock type. Frequent Quaternary volcanic activity may have caused magma to erupt to the surface along deep-seated fault zones, while the portions that did not erupt remained in the crust, existing as localized magma chambers and forming hot dry rock resources in their surrounding areas [74,78,79]. This research shows that the thermal anomalies in the lithosphere, generated by the Hainan plume, migrate beneath the Gan–Min region along with the motion of the South China Plate. The lithosphere under Hainan Island has not experienced significant thermal perturbation, and the heat flow (65~70 mW/m2) does not exhibit prominent anomalies. However, some local areas of Hainan Island still exhibit high heat flow (>75 mW/m2). Taking into account the tectonic context of the area, it can be deduced that the patterns of high heat flow anomalies and volcanic materials in the region might be influenced by significant deep-rooted faults (Figure 8). Faults in the region create routes for magma to rise, thus making Hainan Island a prime location for the accumulation of hot dry rock resources.

Figure 8.

Heat transfer modes of geothermal systems in Hainan Island and the Gan-Min region. The solid red lines represent faults, and the dashed black lines indicate hydrothermal circulation.

The geothermal resources in the Gan-Min region and Hainan Island are dominated by hydrothermal and hot dry rock types, and both are important geothermal resource-rich zones with significant potential for development. The Gan-Min region benefits from the steady heat supply of the residual thermal anomaly (lithospheric thermal anomalies) from the Hainan plume, which can drive hydrothermal circulation, enhance heat transfer efficiency, and favor the formation of large-scale geothermal resource areas. Although Hainan Island lacks significant lithospheric thermal anomalies, numerous deep-seated fault zones provide preferential pathways for magma migration, and the substantial sedimentary layers of this area act as insulating caps for magma chambers, favoring the formation of dry hot geothermal resources. The dry hot geothermal resources on Hainan Island are controlled by deep-seated faults, and their distribution may exhibit local regionality.

5.3. Model Limitations

This study adopts necessary simplifications in lithospheric rheology to ensure computational tractability. Despite these simplifications, the model successfully captures the key mechanism governing the spatial offset between lithospheric thermal anomalies and the Hainan plume. Future work incorporating more realistic rheological constraints will further refine our understanding of this process.

6. Conclusions

- Analysis of S-wave velocity structure based on high-resolution seismic models indicates a pronounced spatial offset of S-wave low-velocity zones between the asthenospheric and the lithospheric mantle in the southeastern coastal region of China. A notable low-velocity zone is observed within the asthenospheric mantle underneath Hainan Island, which may correspond to the upwelling Hainan plume. Nevertheless, no notable low-velocity body is detected in the overlying lithospheric mantle. In comparison, within the same depth slice, a localized low-velocity body exists within the lithospheric mantle underneath the Gan-Min area, with its position offset approximately 1300 km to the northeast relative to the low-velocity body underneath the asthenosphere of Hainan Island.

- The lithospheric low-velocity anomaly in the Coastal area of Southeastern China shows a good spatial correspondence with high surface heat flow. The low-velocity zone in the lithosphere is detected beneath the Gan-Min region, and the surface also exhibits a significantly high heat flow. However, despite the presence of a mantle plume below Hainan Island, no lithospheric low-velocity anomaly is detected, and the surface does not show a significant heat flow anomaly.

- We developed a geodynamic model to reproduce the movement of the South China Plate in relation to the underlying Hainan mantle plume, using heat flow data as a constraint to invert for key dynamical parameters (plume tail radius of approximately 50 km and excess temperature of about 180 K) of the Hainan plume, and obtained the evolution of the lithospheric thermal structure. The modeling results reveal that the heat delivered by the Hainan plume to the lithosphere gradually migrates along with plate motion, forming a thermal anomaly zone along its hotspot path. The high-temperature region at the leading edge of this thermal anomaly zone may correspond to the lithospheric low-velocity zone observed beneath the Gan-Min region.

- Under the dynamical context of the Hainan plume activity and the NE-directed motion of the South China Plate, the spatial offset of the low-velocity anomaly and the lithospheric thermal anomalies can be well explained. Concurrently, the heat transfer patterns of the geothermal systems in both the Gan-Min region and Hainan Island are better understood. The Gan-Min geothermal system is mainly hydrothermal, powered mainly by a residual thermal anomaly associated with the Hainan plume, and may exhibit a large-scale and relatively uniform distribution. The geothermal resources on Hainan Island are primarily hot dry rock, shaped by underlying faults, and may exhibit local regionality, uneven distribution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z. and L.H.; methodology, H.Z.; software, L.H.; validation, H.Z., L.H. and Y.W.; formal analysis, H.Z.; investigation, H.Z.; resources, H.Z.; data curation, H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z.; writing—review and editing, L.H.; visualization, H.Z.; supervision, L.H.; project administration, Y.W. and L.H.; funding acquisition, Y.W. and L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deep Earth Probe and Mineral Resources Exploration National Science and Technology Major Project “South China Sea Expansion—Thermal Effects of the Hainan Mantle Plume Structure and Geothermal Enrichment Mechanisms” (No. 2025ZD1010002), the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA0716002), as well as the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42074095, 41830424).

Data Availability Statement

The seismic velocity data used in this study are derived from the China Seismological Reference Model CSRM-1.0 (http://chinageorefmodel.org).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Richards, M.A.; Hager, B.H.; Sleep, N.H. Dynamically supported geoid highs over hotspots: Observation and theory. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1988, 93, 7690–7708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, W.J. Convection Plumes in the Lower Mantle. Nature 1971, 230, 42–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R.A.; Richards, M.A. Hotspots, mantle plumes, flood basalts, and true polar wander. Rev. Geophys. 1991, 29, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, D.R.; Rawlinson, N.; Iaffaldano, G.; Campbell, I.H. Lithospheric controls on magma composition along Earth’s longest continental hotspot track. Nature 2015, 525, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molnar, P.; Stock, J. Relative motions of hotspots in the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans since late Cretaceous time. Nature 1987, 327, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.S.; Chen, Y.J. Seismic evidence of the Hainan mantle plume by receiver function analysis in southern China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 8978–8985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Zhao, D.; Steinberger, B.; Wu, B.; Shen, F.; Li, Z. New seismic constraints on the upper mantle structure of the Hainan plume. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2009, 173, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Zhao, D.; Xu, Y. Azimuthal Anisotropy Tomography of the Southeast Asia Subduction System. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2021JB022854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, B.M.; Yang, T.; Gu, S. Upper mantle and transition zone structure beneath Leizhou–Hainan region: Seismic evidence for a lower-mantle origin of the Hainan plume. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2015, 111, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Fan, Q. U–Th isotopes in Hainan basalts: Implications for sub-asthenospheric origin of EM2 mantle endmember and the dynamics of melting beneath Hainan Island. Lithos 2010, 116, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Suzuki, K.; Kurisu, M.; Kashiwabara, T.; Xu, J.; Guo, Z.; Li, J.; Chen, J. Late Cenozoic Hainan OIB-like basalts in SE Asia record the interaction between a deep mantle plume and stagnant slab. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2025, 407, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Gao, R.; Wang, Z.; Hou, T.; Liao, J.; Yan, C. Coexistence of Hainan Plume and Stagnant Slab in the Mantle Transition Zone beneath the South China Sea Spreading Ridge: Constraints from Volcanic Glasses and Seismic Tomography. Lithosphere 2021, 2021, 6619463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.B.; Jordan, M.; Steinberger, B.; Puskas, C.M.; Farrell, J.; Waite, G.P.; Husen, S.; Chang, W.-L.; O’Connell, R. Geodynamics of the Yellowstone hotspot and mantle plume: Seismic and GPS imaging, kinematics, and mantle flow. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2009, 188, 26–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtillot, V.; Davaille, A.; Besse, J.; Stock, J. Three distinct types of hotspots in the Earth’s mantle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2003, 205, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, F.; Leng, W.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y. Crustal Footprint of the Hainan Plume Beneath Southeast China. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2018, 123, 3065–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, M.; Wu, Q. Crustal thickness map of the Chinese mainland from teleseismic receiver functions. Tectonophysics 2014, 611, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.B.; Liu, S.W.; Chen, C.i.; Jiang, G.Z.; Wu, J.H.; Guo, L.Y.; Wang, Y.Q.; Zhang, H.; ZhuTing, W.; XiaoXue, J.; et al. Compilation of terrestrial heat flow data in continental China (5th edition). Chin. J. Geophys. 2024, 67, 4233–4265. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; He, L.; Chen, C.; Guo, L. Geodynamic correlation between the Hainan plume and the heat flow along the Southeast Coast of China: Numerical simulation. Geothermics 2025, 132, 103411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sain, K. Seismic Velocity and Temperature Relationships. In Encyclopedia of Solid Earth Geophysics; Gupta, H.K., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 161, pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, C.M.R. The Solid Earth: An Introduction to Global Geophysics, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004; Volume 978. [Google Scholar]

- Karato, S.I. Importance of anelasticity in the interpretation of seismic tomography. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1993, 20, 1623–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goes, S.; Govers, R.; Vacher, P. Shallow mantle temperatures under Europe from P and S wave tomography. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2000, 105, 11153–11169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Cheng, S.; Wu, J.; Wang, W.; Sun, L.; Wang, X.; Ma, J.; Tong, Y.; Liang, X.; Tian, X.; et al. CSRM-1.0: A China Seismological Reference Model. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2024, 129, e2024JB029520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Yu, S. The China Seismological Reference Model project. Earth Planet. Phys. 2023, 7, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, M.; Shi, Y. Lithospheric thickness of the Chinese continent. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2006, 159, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L. Emeishan mantle plume and its potential impact on the Sichuan Basin: Insights from numerical modeling. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2022, 323, 106841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weertman, J.; Weertman, J.R. High Temperature Creep of Rock and Mantle Viscosity. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1975, 3, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weertman, J. The creep strength of the Earth’s mantle. Rev. Geophys. 1970, 8, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocker, R.L.; Ashby, M.F. On the rheology of the upper mantle. Rev. Geophys. 1973, 11, 391–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranalli, G. Rheology of the Earth, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1995; Volume XVI, p. 414. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, S.; Watts, A.B. Constraints on the dynamics of mantle plumes from uplift of the Hawaiian Islands. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2002, 203, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hunen, J.; Zhong, S. New insight in the Hawaiian plume swell dynamics from scaling laws. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L. Numerical modeling of convective erosion and peridotite-melt interaction in big mantle wedge: Implications for the destruction of the North China Craton. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2014, 119, 3662–3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressel, I.; Scheck-Wenderoth, M.; Cacace, M. Backward modelling of the subsidence evolution of the Colorado Basin, offshore Argentina and its relation to the evolution of the conjugate Orange Basin, offshore SW Africa. Tectonophysics 2017, 716, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; He, L.; Yi, Z.; Zhang, L. Anomalous Post-Rift Subsidence in the Bohai Bay Basin, Eastern China: Contributions From Mantle Process and Fault Activity. Tectonics 2022, 41, e2021TC006748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Leng, W. Dynamics of hidden hotspot tracks beneath the continental lithosphere. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2014, 401, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, S.; Nolet, G. Upper mantle beneath Southeast Asia from S velocity tomography. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2003, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.W. Numerical Modelings on the Dynamic Process of the Paleo-Pacific Plate beneath the South China Block in the Mesozoic. Doctoral Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gilder, S.A.; Keller, G.R.; Luo, M.; Goodell, P.C. Eastern Asia and the Western Pacific timing and spatial distribution of rifting in China. Tectonophysics 1991, 197, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhu, G.; Tong, W.; Cui, K.R.; Liu, Q. Formation and evolution of the Tancheng-Lujiang wrench fault system: A major shear system to the northwest of the Pacific Ocean. Tectonophysics 1987, 134, 273–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Tao, K.; Xing, G.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, Y. Petrological Records of the Mesozoic-Cenozoic Mantle Plume Tectonics in Epicontinental Area of Southeast China. Unspecified. Acta Geosci. Sin. 1999, 20, 253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Hsü, K.J.; Sun, S.; Li, J.l.; Chen, H.; Pen, H.P.; Şengör, A.M.C. Mesozoic overthrust tectonics in south China. Geology 1988, 16, 418–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsü, K.J.; Li, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, Q.; Sun, S.; Şengör, A.M.C. Tectonics of South China: Key to understanding West Pacific geology. Tectonophysics 1990, 183, 9–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Cretaceous magmatism and lithospheric extension in Southeast China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2000, 18, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ling, M.; Li, C.; Zhang, H.; Ding, X.; Yang, X.; Fan, W.; Li, Y.L.; Sun, W. A-type granite belts of two chemical subgroups in central eastern China: Indication of ridge subduction. Lithos 2012, 150, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, W.; Cawood, P.A.; Li, S. Sr–Nd–Pb isotopic constraints on multiple mantle domains for Mesozoic mafic rocks beneath the South China Block hinterland. Lithos 2008, 106, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhao, P.; Zhou, Q.; Liao, S.; Jin, G. Petrogenesis and tectonic implications of Early Cretaceous S- and A-type granites in the northwest of the Gan-Hang rift, SE China. Lithos 2011, 121, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Dai, B.; Liao, S.; Zhao, K.; Ling, H. Middle to late Jurassic felsic and mafic magmatism in southern Hunan province, southeast China: Implications for a continental arc to rifting. Lithos 2009, 107, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, W. Origin of Late Mesozoic igneous rocks in Southeastern China: Implications for lithosphere subduction and underplating of mafic magmas. Tectonophysics 2000, 326, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; He, L.; Huang, F. Review of Mesozoic geodynamics research of South China. Prog. Geophys. 2013, 28, 633–647. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Li, X. Formation of the 1300-km-wide intracontinental orogen and postorogenic magmatic province in Mesozoic South China: A flat-slab subduction model. Geology 2007, 35, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Faure, M.C.; Wang, B.; Zhou, X.; Song, B. Late Palaeozoic–Early Mesozoic geological features of South China: Response to the Indosinian collision events in Southeast Asia. Comptes Rendus Geosci. 2008, 340, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lithgow-Bertelloni, C.; Richards, M.A. The dynamics of Cenozoic and Mesozoic plate motions. Rev. Geophys. 1998, 36, 27–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahirovic, S.; Seton, M.; Müller, R.D. The Cretaceous and Cenozoic tectonic evolution of Southeast Asia. Solid Earth 2014, 5, 227–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seton, M.; Müller, R.D.; Zahirovic, S.; Gaina, C.; Torsvik, T.H.; Shephard, G.; Talsma, A.; Gurnis, M.; Turner, M.; Maus, S.; et al. Global continental and ocean basin reconstructions since 200 Ma. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2012, 113, 212–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.D.; Seton, M.; Zahirovic, S.; Williams, S.E.; Matthews, K.J.; Wright, N.M.; Shephard, G.E.; Maloney, K.T.; Barnett-Moore, N.; Hosseinpour, M.; et al. Ocean Basin Evolution and Global-Scale Plate Reorganization Events Since Pangea Breakup. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2016, 44, 107–138. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D. Seismic structure and origin of hotspots and mantle plumes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2001, 192, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. Major transformation and thinning of subcontinental lithosphere beneath eastern China in the Cenozoic-Mesozoic: Review and prospect. Earth Sci. Front. 2006, 13, 50–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.; Xiao, X.; Wu, J.; Wang, W.; Sun, L.; Wang, X.; Wen, L. Crustal thickness and Vp/Vs variation beneath continental China revealed by receiver function analysis. Geophys. J. Int. 2021, 228, 1731–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlstedt, D.L.; Evans, B.; Mackwell, S.J. Strength of the lithosphere: Constraints imposed by laboratory experiments. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1995, 100, 17587–17602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.Q.; Wang, H.F. Nd-Sr-Pb isotopic and chemical evidence for the volcanism with MORB-OIB source characteristics in the Leiqiong area, China. Geochimica 1989, 3, 193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, B.; Wang, H.; Mao, C.; Zhu, N.; Huang, R.; Peng, J.; Pu, Z. Geochronology of and Nd-Sr-Pb isotopic evidence for mantle source in the ancient subduction zone beneath Sanshui Basin, Guangdong Province, China. Chin. J. Geochem. 1989, 8, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, B.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Chang, X.; Hu, Y.; Xie, J. Geochronological and geochemical constraint on the Cenozoic extension of Cathaysian lithosphere and tectonic evolution of the border sea basins in East Asia. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2004, 24, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Bao, Z.; Zhang, B. Geochemistry of the Mesozoic basaltic rocks in southern Hunan Province. Sci. China Ser. D Earth Sci. 1998, 41, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, W.; Guo, F.; Peng, T.; Li, C. Geochemistry of Mesozoic Mafic Rocks Adjacent to the Chenzhou-Linwu fault, South China: Implications for the Lithospheric Boundary between the Yangtze and Cathaysia Blocks. Int. Geol. Rev. 2003, 45, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Li, X.; Wang, X. Geochronological and geochemical results from Mesozoic basalts in southern South China Block support the flat-slab subduction model. Lithos 2012, 132–133, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.; Wang, A. The Mesozoic volcanic age and the source of magma in south Jiangxi. Geol. Jiangxi 1996, 10, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, S.L.; Lee, T.Y.; Lo, C.H.; Wang, P.; Chen, C.Y.; Nguyen, T.Y.; Tran, T.H.; Wu, G. Intraplate extension prior to continental extrusion along the Ailao Shan-Red River shear zone. Geology 1997, 25, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Yan, Y.; Huang, C.-Y.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Z.; Chen, W.-H.; Santosh, M. Opening of the South China Sea and Upwelling of the Hainan Plume. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 2600–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, K.; Fan, T.; Yue, Y.; Wang, R.; Jiang, W.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y. Geochemistry and petrogenesis of Quaternary basalts from Weizhou Island, northwestern South China Sea: Evidence for the Hainan plume. Lithos 2020, 362–363, 105493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Hu, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, j. Terrestrial heat flow in western part of Fujian Province. Chin. J. Geol. 1993, 28, 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P.; Luo, D.G. Characteristics of Heat Production Distribution in SE China. Acta Petrol. Sin. 1995, 11, 292–305. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; He, L.; Wang, J. Heat flow in the continental area of China: A new data set. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2000, 179, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, W. The status and development trend of geothermal resources in China. Earth Sci. Front. 2020, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, N.; Tang, B.; Zhu, C. Deep thermal background of hot spring distribution in the Chinese continent. Acta Geol. Sin. 2022, 96, 195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Hao, M.; Ji, L.; Song, S. Three-dimensional crustal movement and the activities of earthquakes, volcanoes and faults in Hainan Island, China. Geod. Geodyn. 2016, 7, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hao, M.; Qin, S.; Ji, L.; Song, S. Present-day 3D crustal motion and fault activity in the Hainan island. Chin. J. Geophys.-Chin. Ed. 2018, 61, 2310–2321. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.; Wang, G.; Shao, J.; Gan, H.; Tan, X. Distribution and exploration of hot dry rock resources in China: Progress and inspiration. Acta Geol. Sin. 2021, 95, 1366–1381. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.; Gan, H.; Wang, G.; Ma, F. Occurrence Prospect of HDR and Target Site Selection Study in Southeastern of China. Acta Geol. Sin. 2016, 90, 2043–2058. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.