Abstract

With the rapid development of offshore wind farms, the construction of deep sea wind farms has increasingly significant impacts on the safety of maritime navigation. This paper conducts a cluster analysis of ship trajectories based on AIS data to analyze the characteristics of ship traffic flow in the waters near the Shanghai deep sea offshore wind farm. A fuzzy hierarchical analysis method is proposed. Combined with the layout of wind farms and the navigational environment, a risk assessment model for offshore wind farm navigation is established. This model quantifies the factors that affect the safety of ship navigation due to the wind farm and evaluates the navigation risks in the surrounding waters. The results of the research show that the construction of wind farms increases traffic density, interferes with traditional shipping routes, and consequently increases the risk of collisions. The fuzzy hierarchical analysis method has good operability and feasibility in the safety assessment of offshore wind farms, and can provide effective support for future safety assessment of offshore wind farms. The sections are arranged as follows: Firstly, the background and significance of the paper are introduced, as well as the current research status. Secondly, an overview of Shanghai offshore wind farms and their nearby shipping routes is introduced, and then the risk situation of existing wind farms is pointed out. Then the risk assessment method is carried out, and the navigational risk of offshore wind farms is evaluated. Finally, the paper proposes measures to reduce the navigational risk of ships in the vicinity of wind farms.

1. Introduction

With the transformation of the global energy structure, offshore wind power as a clean and renewable energy source has attracted widespread attention. In recent years, the construction of deep sea offshore wind farms has gradually become a new trend in the development of offshore wind energy. However, the construction of wind farms inevitably affects the safety of shipping in the surrounding waters, especially in areas with heavy maritime traffic. As an economic hub and a major energy-consuming city in China, the construction of deep sea offshore wind farms in Shanghai not only contributes to optimizing the energy structure, but also poses new challenges to the safety of ship navigation.

Currently, domestic and international scholars have conducted extensive research on the navigational safety of offshore wind farms. Krzysztof Naus et al. used historical AIS data to generate quantitative and qualitative characteristics, describing the vessel traffic conditions in and around the wind farm areas and assessing the impact of offshore wind farms on navigational safety and efficiency [1]. Andrew Rawson et al. compared and analyzed vessel traffic before and after the construction of offshore wind farms, using AIS data and GIS to evaluate the impact of wind farms on navigational safety in order to predict and manage potential risks [2].

Cao uses fuzzy comprehensive evaluation and a collision probability model to evaluate the navigation risk of offshore wind farms in Putian Port [3]. Marcjan et al. used the risk matrix method and AIS data to analyze the navigational risks of wind farms in the southern Baltic Sea [4]. Lv et al. assessed the navigational safety risks of offshore wind farms by establishing fuzzy inference rules on the impact of navigational risks in offshore wind farms [5].

Yu et al. assessed the risk of collisions between ships and offshore wind turbines by combining Bayesian networks with evidence inference [6]. Yu et al. proposed a rule-based Bayesian inference method for assessing the risk of collision between ships and offshore facilities [7].

Yuh-Ming Tsai et al. use a fault tree analysis approach to perform a ship-to-ship and ship-to-turbine collision risk analysis [8]. Kang et al. carried out a risk assessment using a modified FMEA method to investigate the relationship between failure modes and their effect on the probability of failure of the whole system [9].

Sinha uses FMECA to evaluate the risk and priority number of a failure to help prioritize maintenance work. He also illustrates the usefulness of RPN numbers in identifying failures which can assist in designing cost-effective maintenance plans [10]. Hong aims to identify and evaluate the economic risks of tropical cyclones to offshore wind farms within China’s Economic Exclusive Zone and help improve decision-making for planners and investors [11].

Gatzert aims to comprehensively present current risks and risk management solutions for renewable energy projects and to identify critical gaps in risk transfer, thereby differentiating between onshore and offshore wind farms with a focus on the European market [12]. Junmin Mou et al. conducted a qualitative and quantitative analysis of potential accident types in offshore wind farms using fault tree analysis to identify key risk factors during their operation [13].Victor Ceder et al. used historical AIS data, ice condition data, and ship performance simulation to analyze the impact of offshore wind farms on shipping routes and winter navigation in the Gulf of Bosnia [14].

Regarding the interference of wind farms with navigation systems, Simbo A. Odunaiya argues that wind turbines may block or reflect radio signals, leading to attenuation or distortion of navigation signals from systems like VOR, thereby affecting the accuracy of aircraft positioning and navigation [15]. Similarly, Vandermolen, Jon et al. suggest that the rotating blades of wind turbines may intercept radar signals, impacting the radar system’s ability to detect targets such as weather patterns and aircraft [16]. Additionally, T. Stupak et al. believe that the tall wind turbines and metal structures in offshore wind farms can generate multiple direct and sidelobe echoes on radar, making it difficult to detect vessels near or behind the wind farm [17].

Recent progress in the integration of renewable energy shows the great potential for the decarbonization of offshore operations, particularly through smart port infrastructure optimization. Notably, the pioneering study by Seyed behblood Issa Zadeh systematically divides carbon reduction measures for modern seaports into three broad categories: energy management systems, infrastructure and equipment upgrades, and policy regulatory interventions. By synthesizing the literature on carbon footprint reduction for smart seaports optimized for energy infrastructure, they further show that smart energy infrastructure optimization for smart ports can achieve substantial efficiency gains while maintaining operational reliability [18,19].

However, systematic research on the impact of deep sea offshore wind farms on ship navigation safety remains relatively scarce. To meet the requirements for the planning and sustainable development of wind farms in Shanghai, this study aims to establish a computational model for assessing the risks between wind farms and ship navigation. By analyzing AIS data and employing the fuzzy analytic hierarchy process (FAHP), combined with the layout of wind farms and the navigational environment, the model evaluates the impact of deep sea offshore wind farms on ship navigation safety. Furthermore, corresponding safety management strategies are proposed.

2. Overview of the Wind Farm and Its Adjacent Shipping Routes

2.1. Overview of the Wind Farm

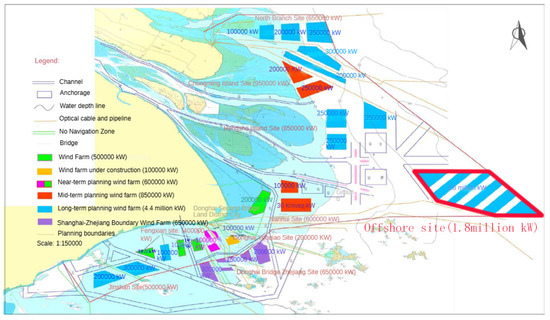

The construction costs of an offshore wind farm are significantly higher than those of an onshore wind farm. Therefore, it is crucial to evaluate whether the location of an offshore wind farm is optimal. The Shanghai coastal region falls within the temperate and subtropical humid climatic zones, which are characterized by abundant wind energy resources. According to the “Shanghai 2024 Offshore Wind Power Project Competitive Allocation Work Program” [20], the competitive allocation project is divided into six bidding sections, with a total installed capacity of 5.8 million kW. The existing and planned sites for Shanghai offshore wind farms are shown in Figure 1. The offshore wind farm is located near the mouth of the Yangtze River, adjacent to waters with high vessel traffic density and complex traffic patterns, which will inevitably have some impact on the navigational environment of the surrounding waters.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of Shanghai offshore wind farm.

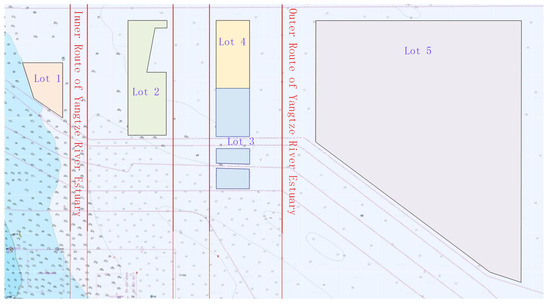

The proposed site for the Shanghai offshore wind farm is located to the north of the Yangtze Estuary Ship Routing System. The area of the offshore site is shown in Figure 1. The interior of the offshore site includes areas of the navigation route that are not suitable for the installation of offshore wind turbines, so that part of the route area needs to be removed from the offshore site. The main navigation routes in the vicinity of the offshore site include the Inner Yangtze Estuary route, the divergence area, and the Outer Yangtze Estuary route. The relationship between the offshore site and the shipping route is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the relationship between the locations of Shanghai offshore wind farms and shipping routes.

2.2. Characteristics of Vessel Traffic Flow Based on AIS Data

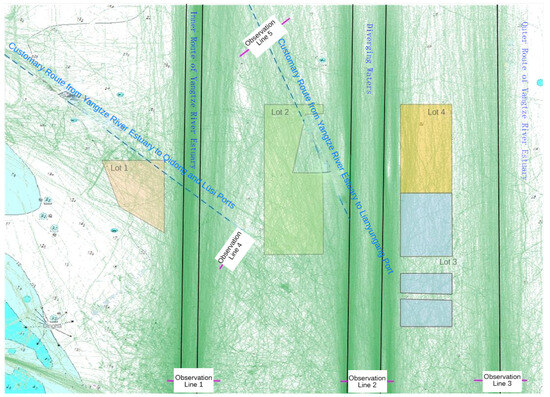

In order to understand the ship traffic flow in the nearby waterways, the traffic volumes of several major routes in the vicinity of the offshore wind farm in 2023 were statistically analyzed. A schematic representation of the selected ship traffic flow cross-sections is shown in Figure 3. Among them, observation line 1 mainly records the vessel traffic flow in the Inner Yangtze Estuary route, observation line 2 focuses on the traffic flow in the divergence area, and observation line 3 records the traffic flow in the Outer Yangtze Estuary route. Observation line 4 is designed to monitor the traffic flow along the regular route from the Yangtze Estuary to Nantong and Lusi Port, while observation line 5 is used to measure the traffic flow along the regular route from the Yangtze Estuary to Lianyungang.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of ship traffic flow cross-section selection.

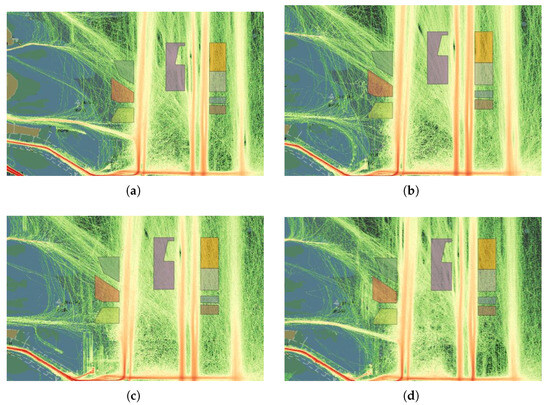

Further analysis was carried out on the flow of vessel traffic in representative months of each quarter in the area, as shown in Figure 4. Based on the navigational conditions in the waters where the offshore wind farm sites and their surrounding areas are located, it can be observed that the deep sea offshore wind farm site in Section 1 has a certain impact on ship navigation. Similarly, the location of the deep sea offshore wind farm in Section 2 also has an impact on vessel navigation. In contrast, the deep sea offshore wind farm sites in Section 3 and Section 4 are located away from the divergence area and the outer Yangtze Estuary route, generally in areas with low traffic density. However, the traffic density on the western side of the wind farm sites in these two sections is higher than on the eastern side, so the potential impact of the western sites on navigational safety needs to be considered.

Figure 4.

Vessel traffic flow density in representative months of each quarter in 2023: (a) Vessel traffic flow density in February. (b) Vessel traffic flow density in May. (c) Vessel traffic flow density in August. (d) Vessel traffic flow density in November.

3. Risk Assessment Indicator System

From the perspective of vessel traffic flow, the waters where the deep sea offshore wind farm is located experience relatively dense vessel traffic with a high volume of vessel movements. The traffic flow analysis shows that in addition to the officially published north–south routes within the Yangtze Estuary, the bifurcated waters, and the routes outside the Yangtze Estuary, there are several potential customary routes in the vicinity of the wind farm. Some of these routes intersect, contributing to a complex navigational environment.

In order to more accurately assess the impact of the offshore wind farm on navigational safety, it is essential to conduct an in-depth investigation of the existing risk factors and the magnitude of their influence. The fuzzy analytic hierarchy process is used to assess the safety of navigation in this context.

3.1. The Basic Principle of Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process

The fuzzy analytic hierarchy process is a multi-criteria decision-making method that integrates the analytic hierarchy process with fuzzy mathematics. By constructing an evaluation matrix, FAHP transforms expert opinions into fuzzy numbers, thereby addressing the uncertainties and ambiguities inherent in expert judgments and ultimately deriving the weights of each criterion.

The basic steps of FAHP include, first, establishing an evaluation index system; second, constructing a hierarchical structure model; third, performing pairwise comparisons; fourth, calculating relative weights; and finally, performing consistency checks. FAHP makes evaluation conclusions intuitive and clear, with a streamlined and efficient process. It ensures that evaluators maintain clear thinking and consistent principles throughout the multi-index evaluation process. FAHP has been widely applied to complex decision-making and evaluation problems such as port management, transport, and supply chain management.

The impact of offshore wind farms on the navigational safety of vessels involves numerous complex and imprecisely quantifiable factors, such as the degree to which meteorological conditions affect vessel navigation and the relationship between wind farm size and navigational risk. These factors are characterized by their inherent fuzziness. Using the FAHP, these ambiguous and qualitative factors can be quantified. This is achieved through the construction of factor sets, rating sets, and fuzzy relationship matrices, ultimately leading to a comprehensive rating result. This approach scientifically reflects the level of navigation safety risks.

3.2. Establishment of the Evaluation Index System

At present, more than 1000 vessels pass through the waters around the Shanghai deep sea offshore wind farm on a daily basis. The vessels passing through the area are mainly those entering and leaving the north and south channels, as well as transit vessels on the north–south routes. These vessels are diverse in type, large in size, and include numerous anchored and transit vessels.

The Shanghai deep sea offshore wind farm will have multiple impacts on the surrounding navigable waters. The numerous wind turbines and associated facilities occupy a significant portion of the marine space, reducing the original expansive navigable area. As the navigable area decreases, the density of vessel traffic increases, leading to increased traffic flow and complexity within the port access channels. In addition, the towering structures of wind turbines obstruct the line of sight of vessel operators, potentially interfering with the navigation of other vessels in the channel and posing a risk to maritime safety.

In order to assess the impact of offshore wind farms on maritime safety, a hierarchical structure model was established, judgment matrices were constructed, and the weights of factors at each level were calculated. This process clarifies the relative importance of different risk assessment indicators to navigation safety risks and provides a reasonable basis for weighting in subsequent fuzzy comprehensive assessments. This approach ensures that the assessment results are more scientific and rational. Based on the traffic risk assessment model, risks in the areas surrounding the wind farm were identified, and a corresponding evaluation index system was designed.

Through a review of relevant literature and extensive consultation with frontline pilots and industry experts, including 20 captains, 15 offshore wind power engineers, and 15 maritime managers, initial indicators were selected based on the principles of systematicity, hierarchy, simplicity, and feasibility in constructing the indicator system. These initial indicators were then refined through questionnaire surveys and factor analysis to determine the final evaluation indicators. This study did not take into account the influence of subjective factors; therefore, the evaluation indicator system does not include any personnel-related metrics.

Based on the risks identified during the implementation of offshore wind projects, the target layer of the evaluation system is defined as “Navigation Risk Assessment for Offshore Wind Farms”. This approach allows for a more comprehensive and accurate analysis of the relationships between factors and their impact on the target layer. The constructed evaluation indicator system for assessing the impact on the safety of navigation is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Evaluation indicator system for navigation safety of offshore wind farms.

3.3. Determination of Indicator Weights Using the Analytic Hierarchy Process

- (1)

- Construction of the Judgment Matrix

Based on the evaluation indicator system for offshore wind farm navigation risk assessment established in Table 1, invite experts in related fields, including captains, offshore wind power engineering experts, and maritime management experts, etc. Based on their professional knowledge and practical experience, compare the relative importance of the factors in the guideline layer. Then, score them according to the 1–9 scale methodology so as to construct a judgment matrix.

Specifically, represents the ratio of the relative importance of two factors ai and aj under the same criterion . The value of ranges from , where the values 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 indicate that ai is equally important, slightly more important, significantly more important, strongly more important, and extremely more important than aj, respectively. The values 2, 4, 6, and 8 represent intermediate levels of importance. Note that , , [21].

Based on this, the judgment matrices C, , , , and for the navigation risk assessment of offshore wind farms can be constructed as follows:

- (2)

- Calculation of the Weight Vector

After constructing the judgment matrix, it is necessary to calculate the weight vector A based on the judgment matrix to ensure that the evaluation conclusions are intuitive and operable. The constructed judgment matrix is a positive matrix, which is unique and necessarily has a maximum eigenvalue .

The corresponding weight vector satisfies the formula. By normalizing , the weights of each factor in the indicator layer relative to their respective criteria layer and the weights of each factor in the criteria layer relative to the target layer can be obtained.

Through calculation using Matlab software R2018a, the maximum eigenvalues corresponding to the matrices C, , , , and are , , , , and , respectively. The fuzzy consistency matrices were normalized to calculate the fuzzy weights of each evaluation criterion. The corresponding weight vectors are as follows:

- (3)

- Consistency Check

To assess the reliability of the conclusions of the matrix analysis, in particular to determine whether there are significant discrepancies between the expert opinions collected during the evaluation of the pilotage support organization’s capabilities, a consistency test is necessary. Let CI be the consistency index and CR the consistency ratio, calculated according to the following formula:

If the consistency ratio , the matrix A is considered to have passed the consistency check. However, if , it indicates that the discrepancy in the consistency index is too large and an adjustment of the importance weights of the indicators is required. Here, refers to the average random consistency index corresponding to the order of the matrix, which is determined by the order n of the matrix A, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Average random consistency index RI of the judgment matrix.

After calculation, the values of , , , , and are all less than 0.1, indicating satisfactory consistency.

6. Conclusions

This paper conducted a clustering study on the ship motion trajectory of AIS data, deeply mined the movement trajectory of ships in the offshore wind farm area, and analyzed the impact of wind farm construction on ship trajectory deviation, speed change, etc. The study found that ship traffic density in the surrounding area of the wind farm will increase. Subsequently, a multi-dimensional risk assessment was conducted based on the FAHP method, and the impact of wind farms on navigation safety was quantitatively analyzed. Thus, the change of the wind farm construction in ship navigation behavior was comprehensively evaluated. The evaluation indicators cover key factors such as natural conditions, navigation conditions, surrounding ships, and construction conditions. The fuzzy risk score obtained by comprehensive calculation is 67.3. The results indicate that wind farms pose a medium risk to navigation safety and require further optimization of wind farm siting and construction. To this end, this paper proposes countermeasures such as optimizing the layout of wind farms, improving navigation safety facilities, and establishing strict navigation management regulations. The results of this study provide a scientific basis for the coordinated development of wind farms and shipping navigation safety. The proposed optimization measures will help improve the level of navigation safety in offshore wind power areas and provide theoretical support and practical guidance for the coordinated development of wind farms and navigation safety.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Y.; funding acquisition, W.Y. and X.J.; draft preparation, J.L.; formal analysis, P.Y.; corresponding, X.J. and J.L.; investigation, J.L.; methodology, P.Y.; writing and editing, X.J. and P.Y.; project administration W.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific Research Project of Shanghai Investigation, Design & Research Institute Co., Ltd. (Grant No. 2023 FD(83)-002). The Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (Grant No. 23010501900).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are contained within this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Funding statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Naus, K.; Banaszak, K.; Szymak, P. The methodology for assessing the impact of offshore wind farms on navigation, based on the automatic identification system historical data. Energies 2021, 14, 6559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawson, A.; Rogers, E. Assessing the impacts to vessel traffic from offshore wind farms in the Thames Es-tuary. Sci. J. Marit. Univ. Szczec. 2015, 43, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C. A Study on Influence of Putian Port Offshore Wind Farm Construction on Navigation Safety. Master’s Thesis, World Maritime University, Malmö, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marcjan, K.; Kotkowska, D. Identification of Navigational Risks Associated with Wind Farms. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2023, 26, 595–611. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, P.; Zhen, R.; Shao, Z. A Novel Method for Navigational Risk Assessment in Wind Farm Waters Based on the Fuzzy Inference System. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 4588333. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.; Liu, K.; Chang, C.-H.; Yang, Z. Realising advanced risk assessment of vessel traffic flows near offshore wind farms. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 203, 107086. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.; Liu, K.; Yang, Z.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z. Geometrical risk evaluation of the collisions between ships and offshore installations using rule-based Bayesian reasoning. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 210, 107474. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, Y.M.; Lin, C.Y. Investigation on improving strategies for navigation safety in the offshore wind farm in Taiwan Strait. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Sun, L.; Sun, H.; Wu, C. Risk assessment of floating offshore wind turbine based on correla-tion-FMEA. Ocean. Eng. 2017, 129, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, Y.; Steel, J.A. A progressive study into offshore wind farm maintenance optimisation using risk based failure analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Möller, B. An economic assessment of tropical cyclone risk on offshore wind farms. Renew. Energy 2012, 44, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatzert, N.; Kosub, T. Risks and risk management of renewable energy projects: The case of onshore and offshore wind parks. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 60, 982–998. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, J.; Jia, X.; Chen, P.; Chen, L. Research on operation safety of offshore wind farms. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceder, V.; Helgesson, N.; Thomas, B.P.; Ringsberg, J.W. The Impact of Wind Farms on Winter Navigation; Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Odunaiya, S.A. Wind farms and their effect on radio navigation aids. In Proceedings of the 14th SIIV IFIS, Toulouse, France, 12–16 June 2006; pp. 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Vander Molen, J.; Nordman, E. Wind Farms and Navigation: Potential Impacts for Radar, Air Traffic and Marine Navigation. 2014. Available online: https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/45977 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Stupak, T.; Wilczyński, P. The impact of the offshore wind farm on radar navigation. Trans. Nav. Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2022, 16, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa Zadeh, S.B.; López Gutiérrez, J.S.; Esteban, M.D.; Fernández-Sánchez, G.; Garay-Rondero, C.L. Scope of the Literature on Efforts to Reduce the Carbon Footprint of Seaports. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa Zadeh, S.B.; Esteban Perez, M.D.; López-Gutiérrez, J.-S.; Fernández-Sánchez, G. Optimizing Smart Energy Infrastructure in Smart Ports: A Systematic Scoping Review of Carbon Footprint Reduction. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Development and Reform Commission. Shanghai 2024 Offshore Wind Power Project Competitive Allocation Work Program. Available online: https://fgw.sh.gov.cn/fgw_ny/20240320/b12c958e447240989804e75351945baf.html (accessed on 19 March 2024).

- Ioannidis, D.; Vagiona, D.G. Optimal Wind Farm Siting Using a Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process: Evaluating the Island of Andros, Greece. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujian Maritime Safety Administration. Technical Guidelines for Navigation Safety Analysis of Offshore Wind Farm Sites. Available online: https://wind.imarine.cn/news/21519.html (accessed on 19 August 2021).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).