Antarctic Sea Ice Extraction for Remote Sensing Images via Modified U-Net Based on Feature Enhancement Driven by Graph Convolution Network

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A novel SEGR module is proposed to reconstruct the global dependencies of features, complementing the missing global context information of features. Experiments have demonstrated that SEGR effectively improves the accuracy of sea ice extraction.

- (2)

- The GAAST is applied to the construction of adjacency matrices in graph data transformation. Unlike other methods, we do not need to manually set more additional parameters to construct the appropriate adjacency matrix based on the node features. Experiments demonstrate that GAAST achieves the shortest inference time, while maintaining the performance of the module.

- (3)

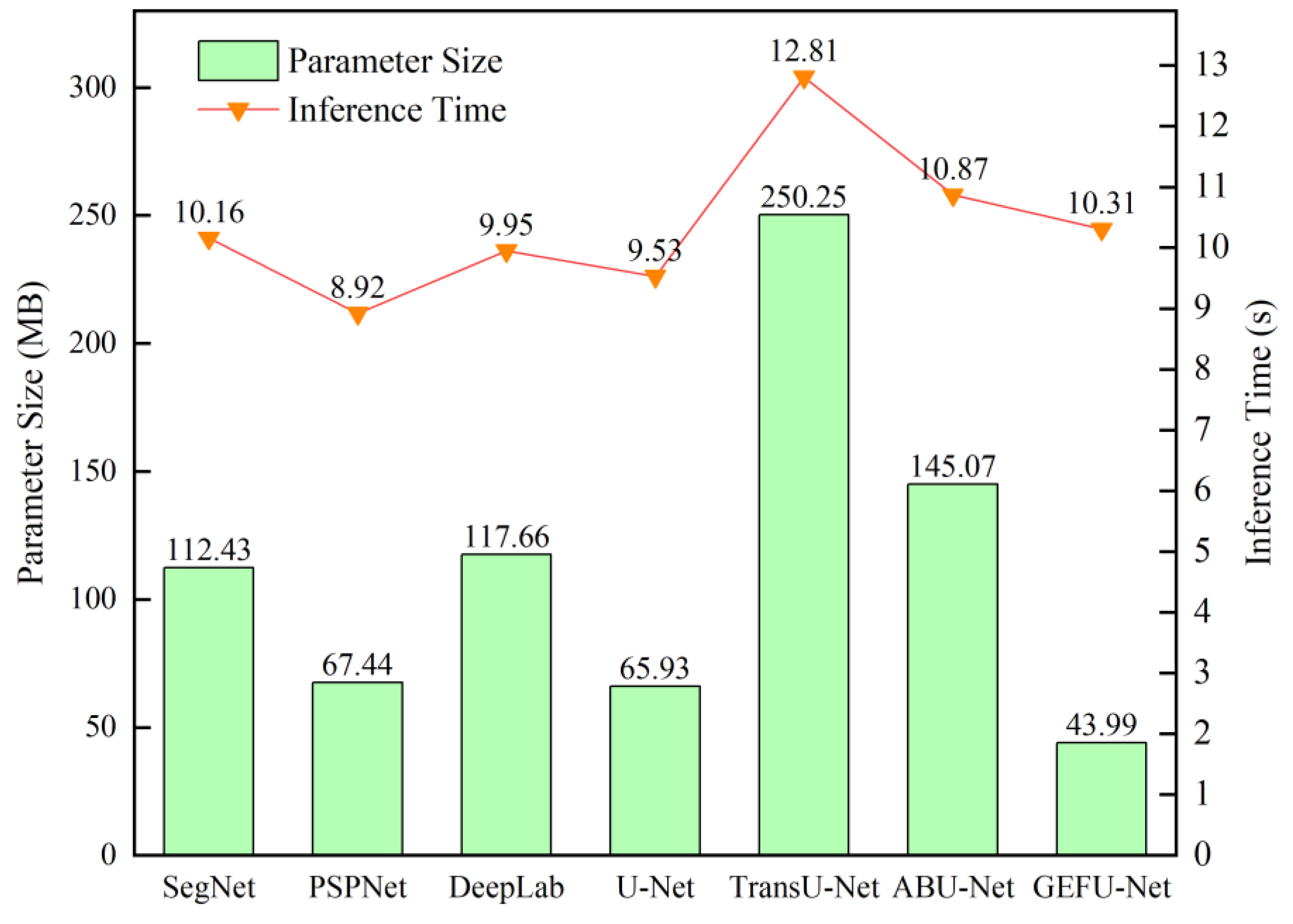

- The proposed GEFU-Net is applied to a real Antarctic sea ice extraction scenes, and the analysis reveals that the proposed model achieves the best balance between the deployed parameter size and the inference speed.

2. Materials

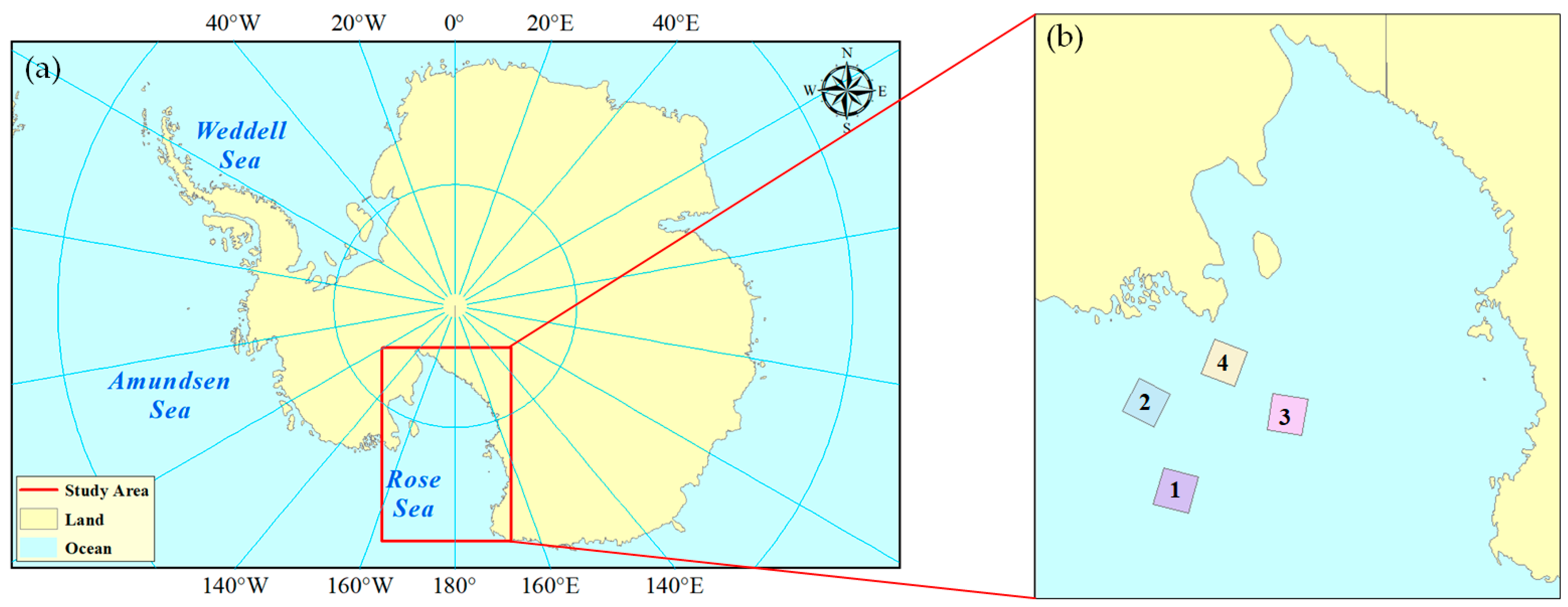

2.1. Study Area and Spectral Data Preparation

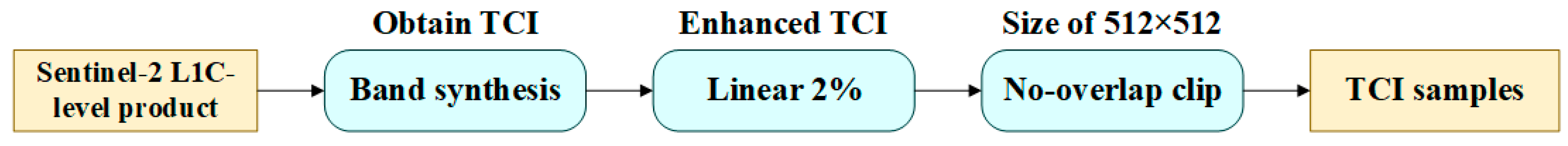

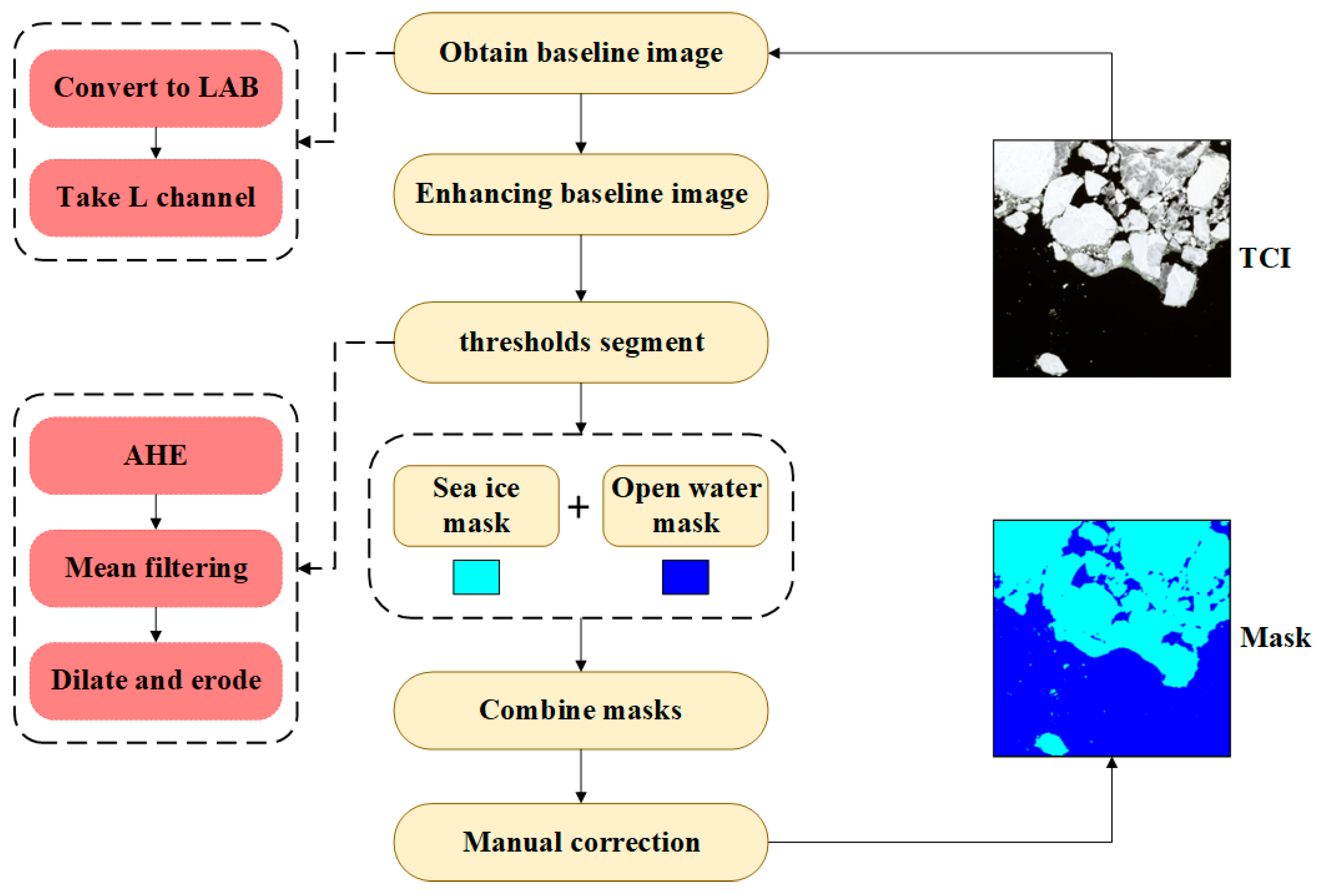

2.2. Production Process of Dataset

3. Methods

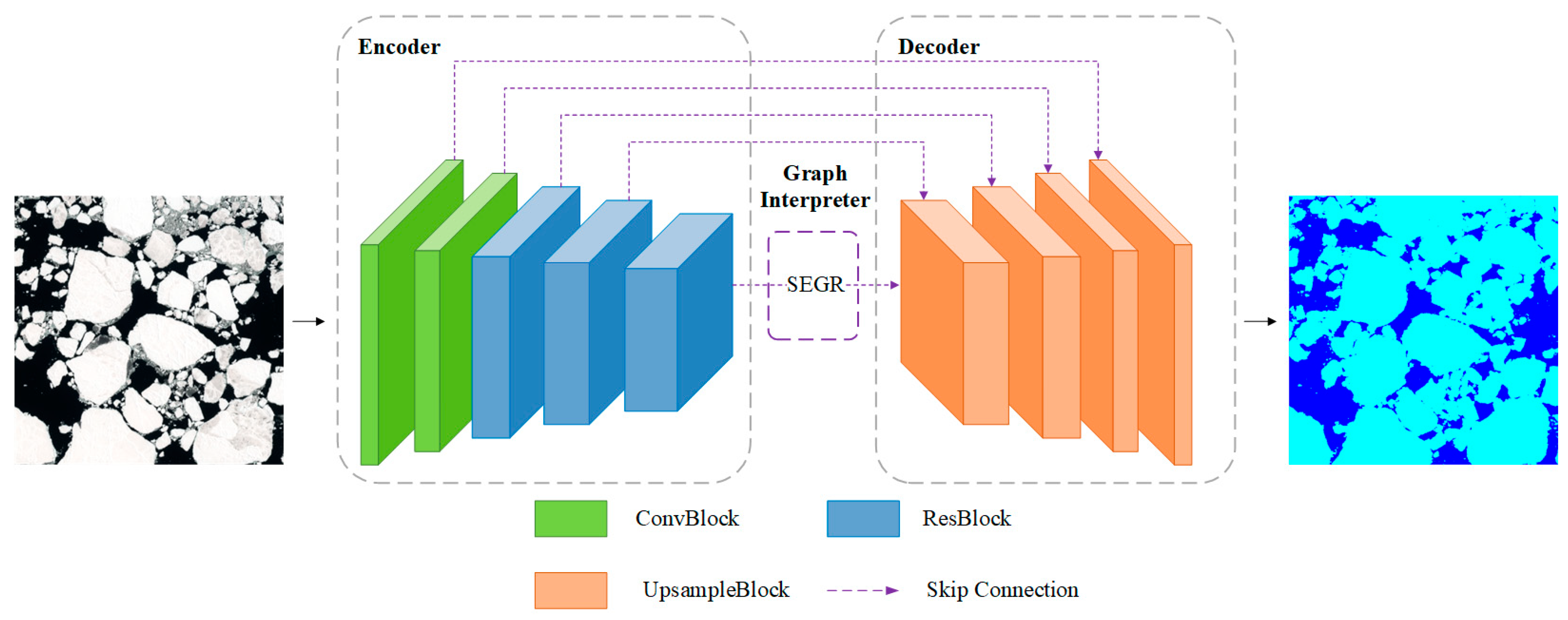

3.1. Overview

3.2. Overall Structure of GEFU-Net

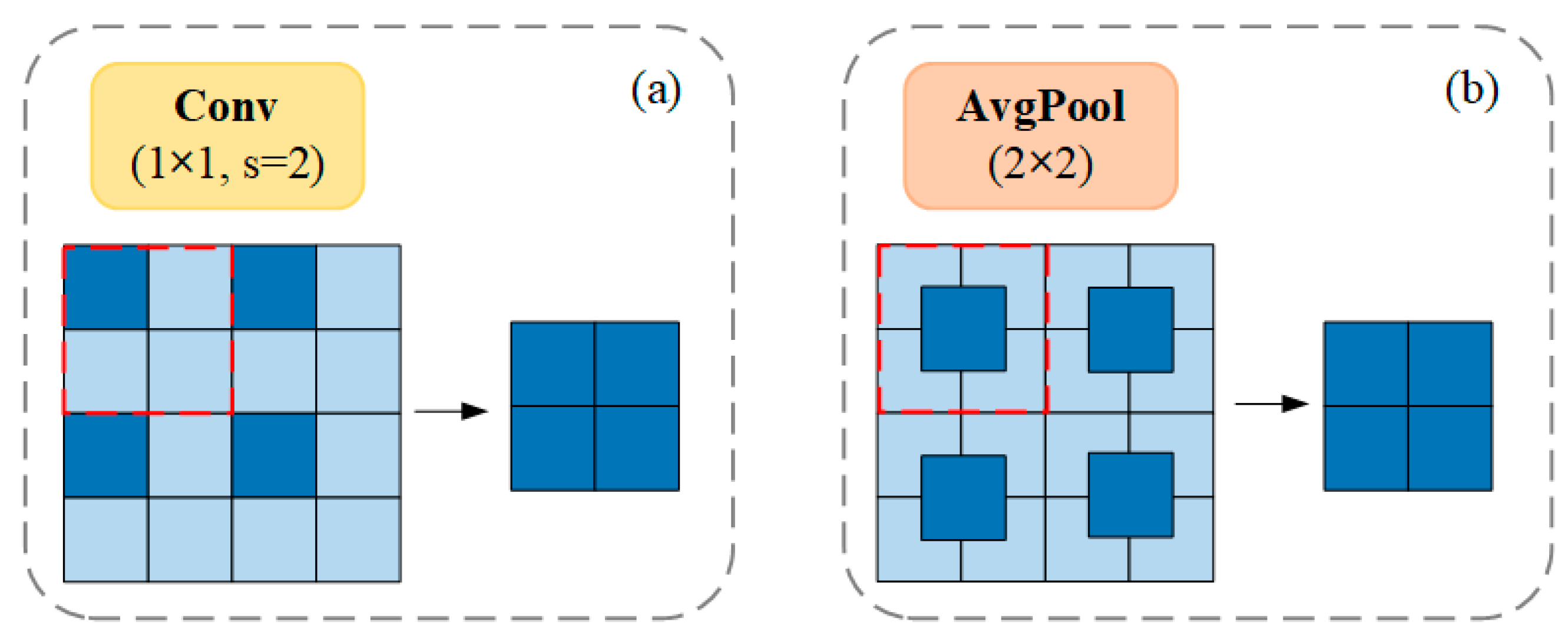

3.2.1. Backbone Network of Encoder

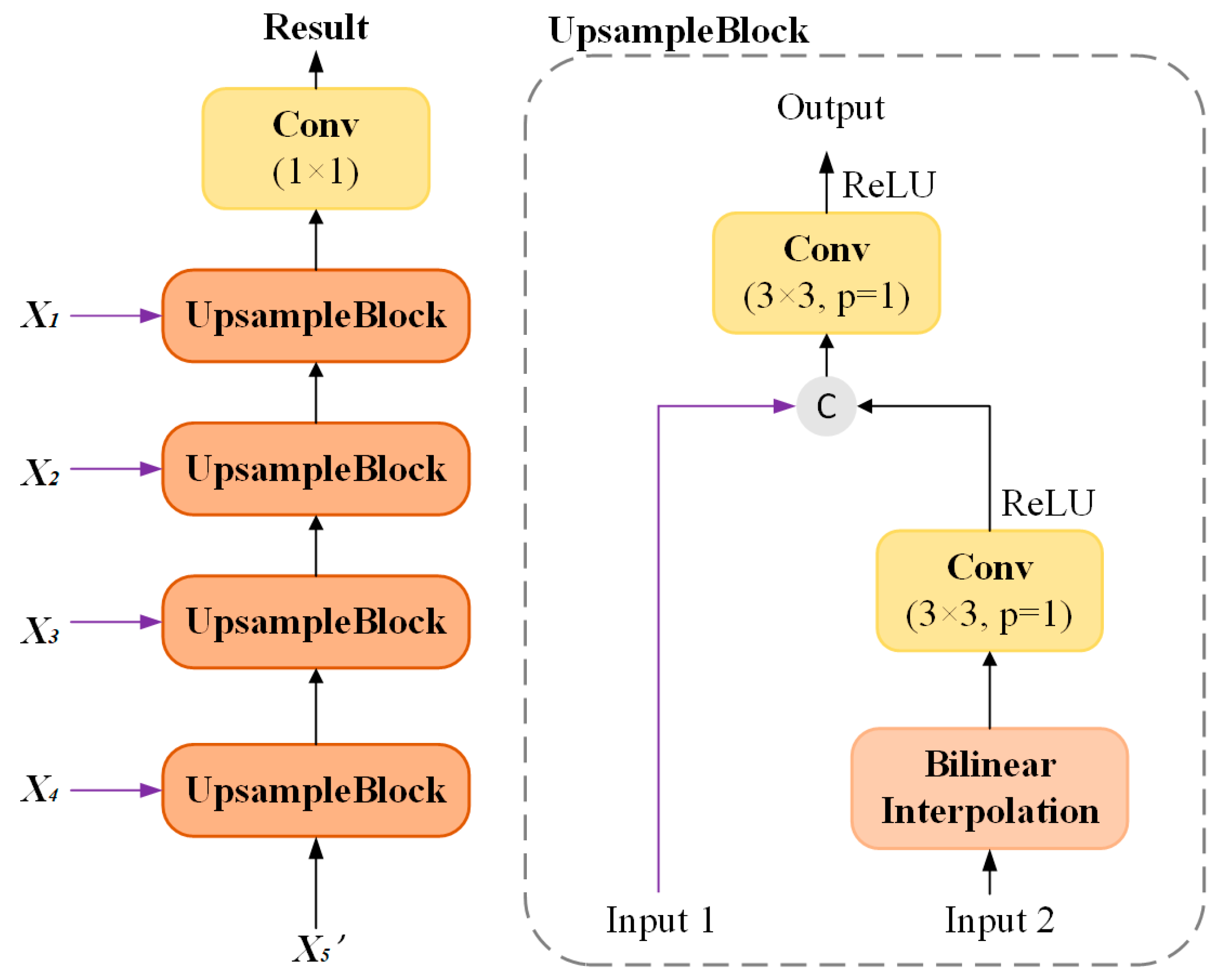

3.2.2. Backbone Network of Decoder

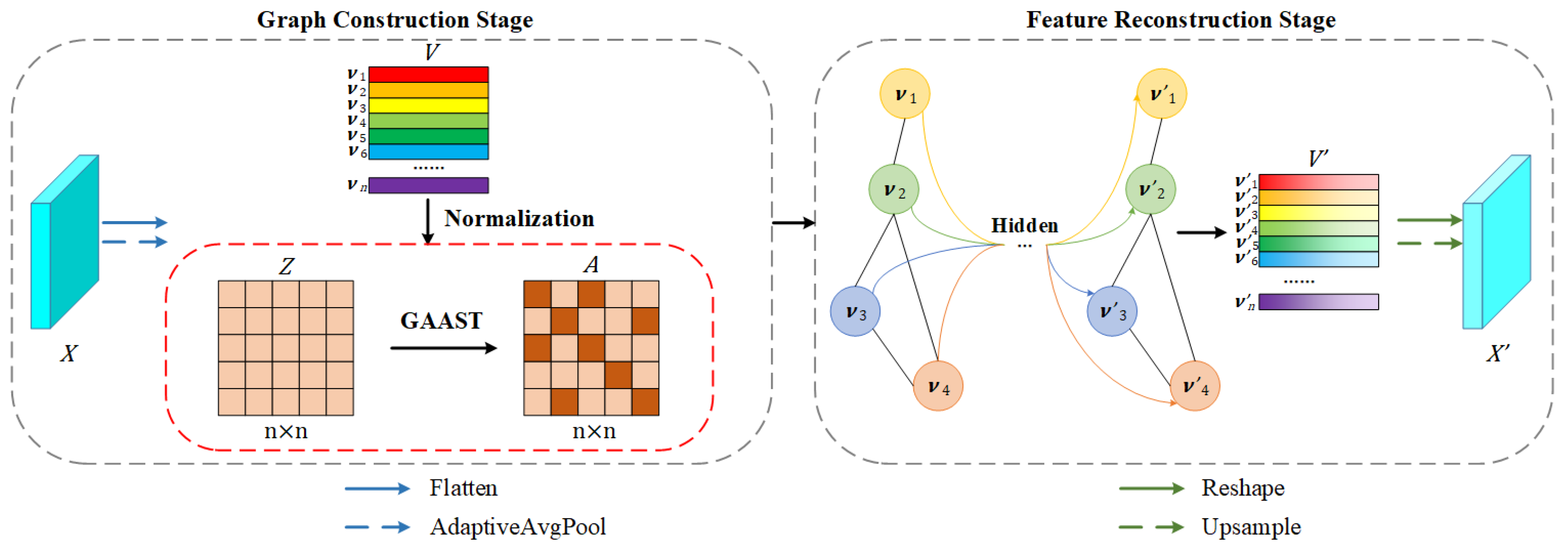

3.2.3. SEGR Module of Graph Interpreter

3.3. Loss Function

4. Results

4.1. Experimental Platform and Parameter Setting

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

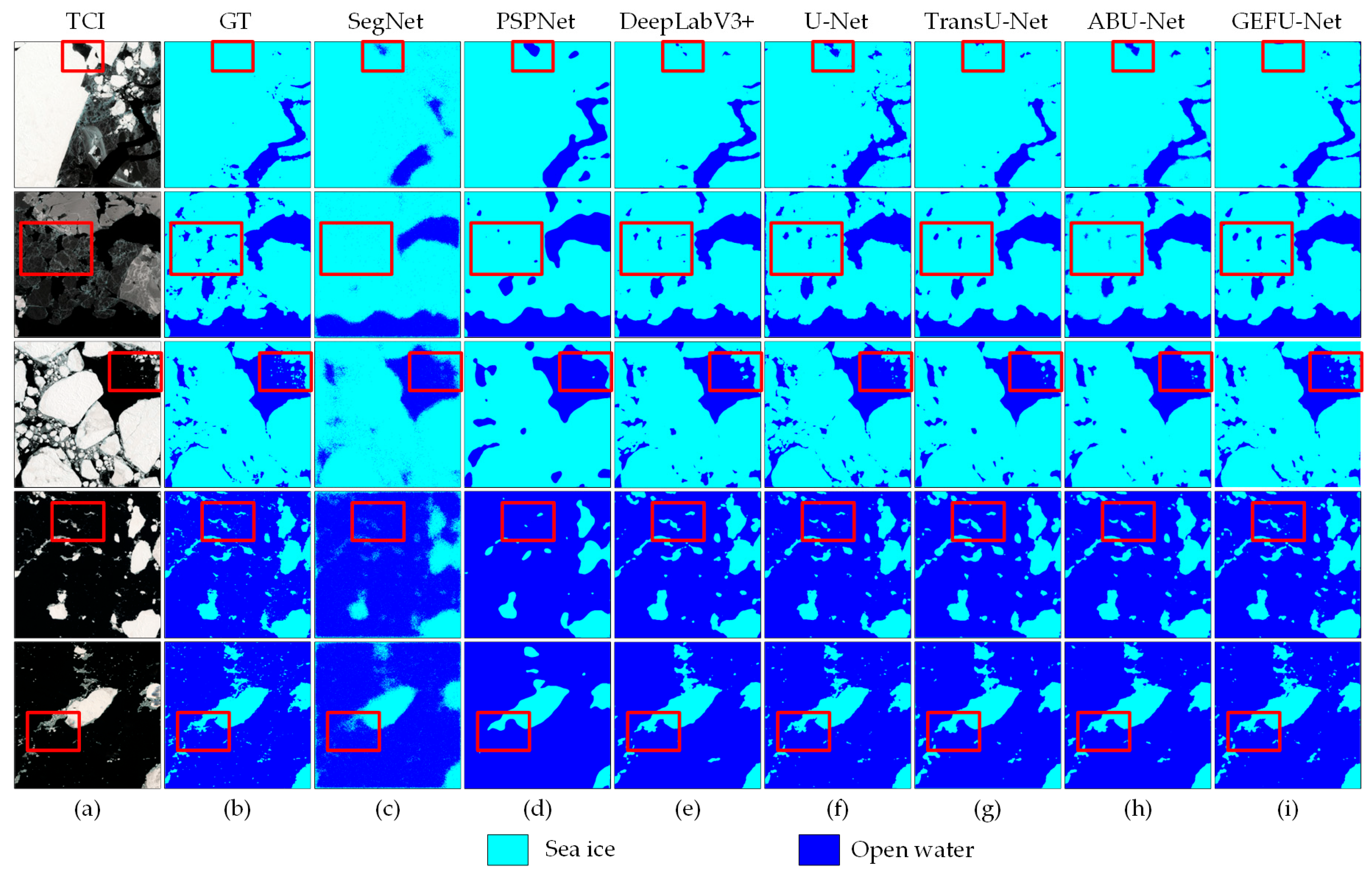

4.3. Ice Extraction Results

4.4. SEGR Module Analysis

4.4.1. Effect of SEGR Module Location and Number on the Extraction Results

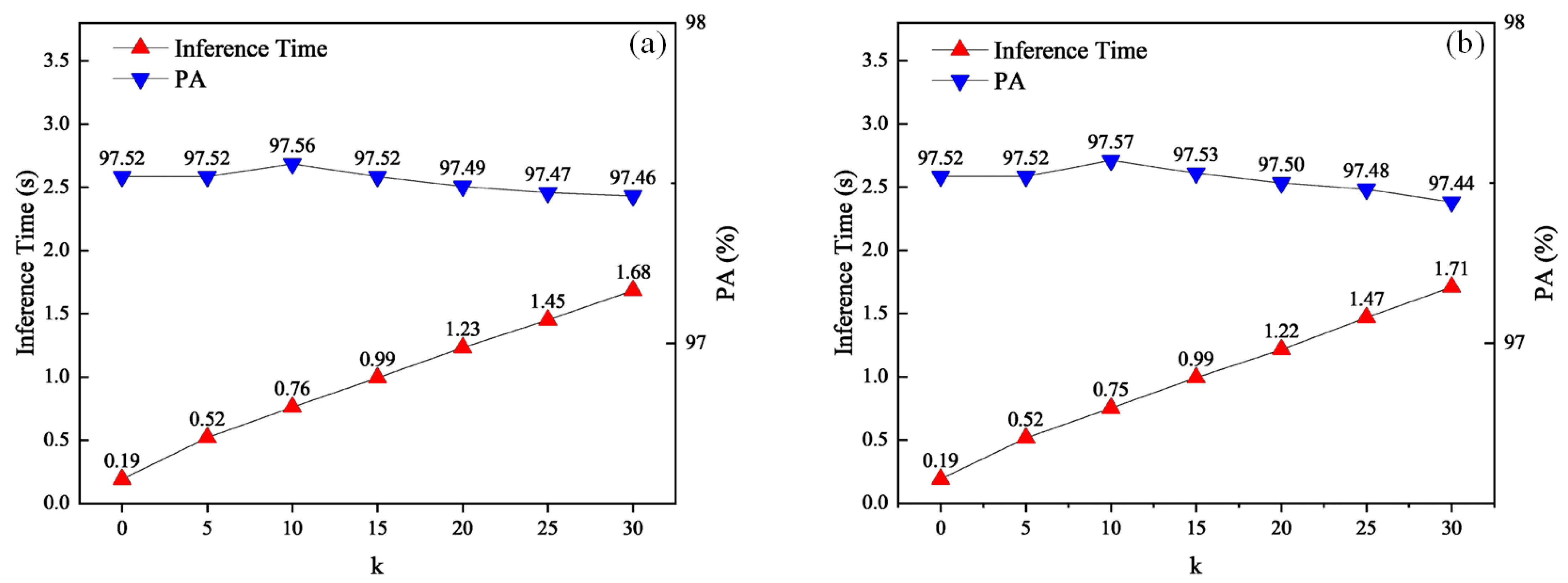

4.4.2. Effect of GAAST on Adjacency Matrix Generation

4.4.3. Effect of Adaptive Pooling Size on Extraction Results in SEGR

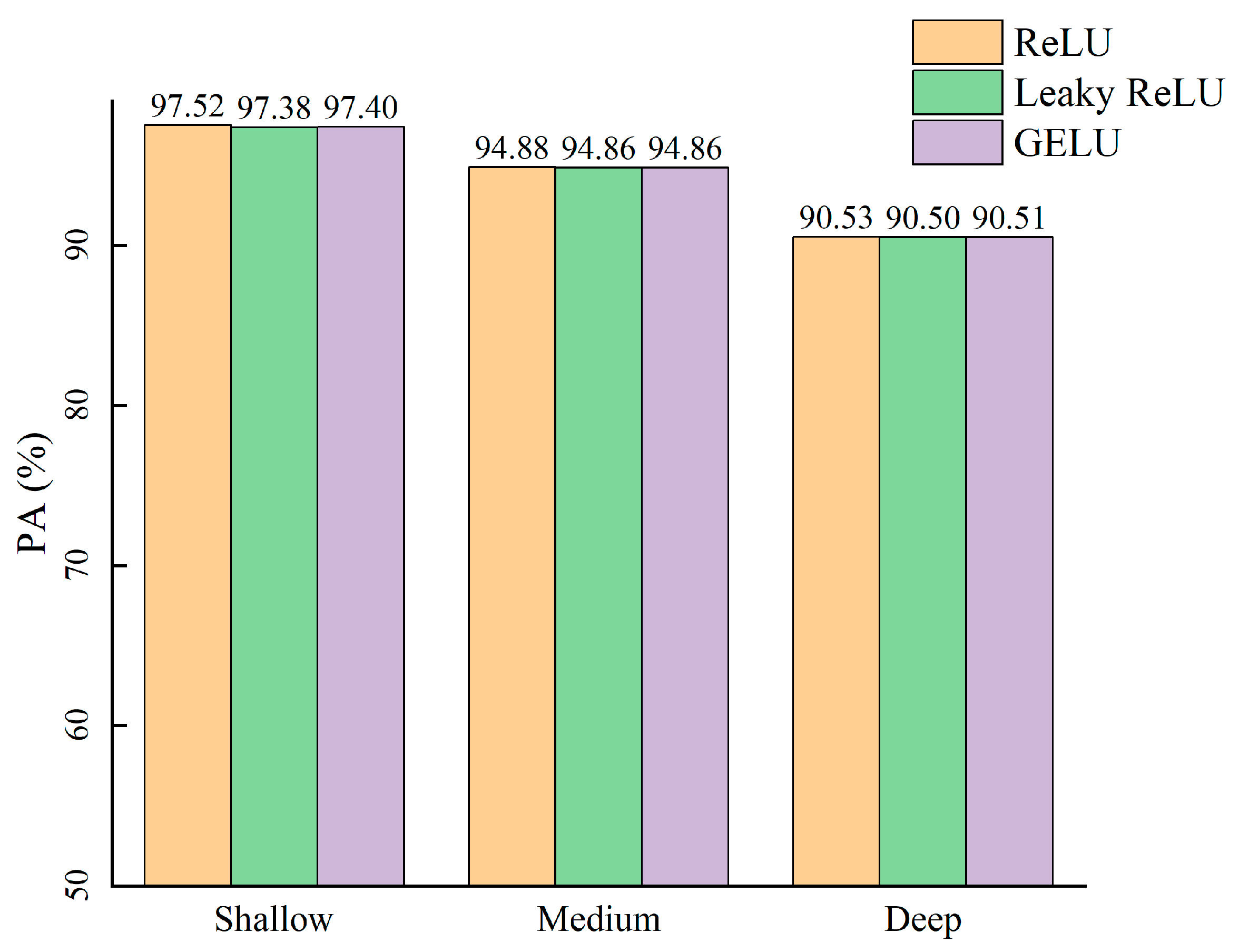

4.4.4. Effect of Number of GCN Layers on Extraction Results in SEGR

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations of SEGR Module

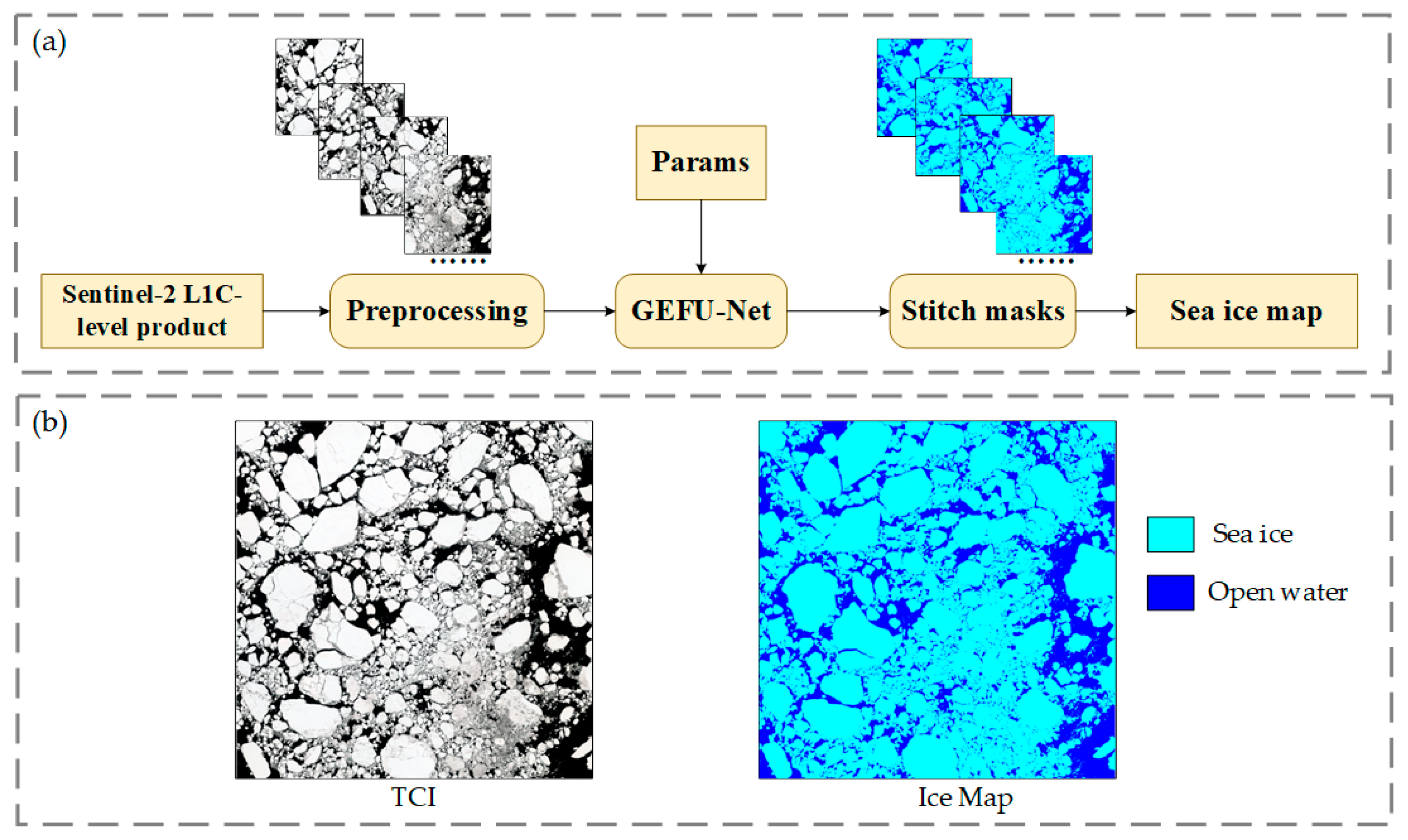

5.2. Application of Sea Ice Mapping in Remote Imaging

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eayrs, C.; Li, X.; Raphael, M.N.; Holland, D.M. Rapid decline in Antarctic sea ice in recent years hints at future change. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purich, A.; Doddridge, E.W. Record low Antarctic sea ice coverage indicates a new sea ice state. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swadling, K.M.; Constable, A.J.; Fraser, A.D.; Massom, R.A.; Borup, M.D.; Ghigliotti, L.; Granata, A.; Guglielmo, L.; Johnston, N.M.; Kawaguchi, S. Biological responses to change in Antarctic sea ice habitats. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 10, 1073823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeConto, R.M.; Pollard, D.; Alley, R.B.; Velicogna, I.; Gasson, E.; Gomez, N.; Sadai, S.; Condron, A.; Gilford, D.M.; Ashe, E.L. The Paris Climate Agreement and future sea-level rise from Antarctic. Nature 2021, 593, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Deser, C. Tropical and Antarctic sea ice impacts of observed Southern Ocean warming and cooling trends since 1949. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Huang, W. Sea ice remote sensing using GNSS-R: A review. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Wang, J. Sea ice image classification based on heterogeneous data fusion and deep learning. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Gong, Z.; Mou, K.; Hu, J.; Ke, Y.; Zhou, D. Automatic and accurate extraction of sea ice in the turbid waters of the yellow river estuary based on image spectral and spatial information. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, A.; Schwarz, E.; Aldenhoff, W. Landsat-8 Sea Ice Classification Using Deep Neural Networks. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waga, H.; Eicken, H.; Light, B.; Fukamachi, Y. A neural network-based method for satellite-based mapping of sediment-laden sea ice in the Arctic. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 270, 112861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Itkin, P.; Singha, S.; Doulgeris, A.P.; Johansson, M.; Spreen, G. Sea ice classification of TerraSAR-X ScanSAR images for the MOSAiC expedition incorporating per-class incidence angle dependency of image texture. Cryosphere 2023, 17, 1279–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yan, Y.; Ren, J.; Hwang, B.; Marshall, S.; Durrani, T. Superpixel Based Sea Ice Segmentation with High-Resolution Optical Images: Analysis and Evaluation. In Proceedings of the International Conference in Communications, Signal Processing, and Systems, Changbaishan, China, 24–25 July 2021; pp. 474–482. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M.; Clausi, D.A.; Xu, L. Sea-ice mapping of RADARSAT-2 imagery by integrating spatial contexture with textural features. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 7964–7977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Yu, A.; Xu, Q.; Sun, Q.; Guo, W.; Ji, S.; Wen, B.; Qiu, C. Sea Ice Extraction via Remote Sensing Imagery: Algorithms, Datasets, Applications and Challenges. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Tong, F.; Ding, X.; Li, S.; Zhu, R.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Fernandez-Beltran, R. Decoding the partial pretrained networks for sea-ice segmentation of 2021 gaofen challenge. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 4521–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowden, B.; De Silva, O.; Huang, W.; Oldford, D. Sea ice classification via deep neural network semantic segmentation. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 21, 11879–11888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Li, H.; He, Q.; Gao, G.; Liotta, A. E-mpspnet: Ice–water sar scene segmentation based on multi-scale semantic features and edge supervision. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagi, A.S.; Kumar, D.; Sola, D.; Scott, K.A. RUF: Effective sea ice floe segmentation using end-to-end RES-UNET-CRF with dual loss. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Xu, H.; Liu, B.; Li, X. Sea ice and open water classification of SAR images using a deep learning model. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2020-2020 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 26 September–2 October 2020; pp. 3051–3054. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, X.; Xu, H. Development of a dual-attention U-Net model for sea ice and open water classification on SAR images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 19, 4010205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudakow, I.; Asari, V.K.; Liu, R.; Demchev, D. MeltPondNet: A Swin Transformer U-Net for Detection of Melt Ponds on Arctic Sea Ice. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 8776–8784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, G.; Stark, H.; Jegelka, S.; Jaakkola, T.; Barzilay, R. Graph neural networks. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2024, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Al-qaness, M.A.; Al-Alimi, D.; Dahou, A.; Abd Elaziz, M.; Ewees, A.A. Hyperspectral image classification using graph convolutional network: A comprehensive review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 257, 125106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Chen, C.; Zhou, Y.; Berretti, S.; Liu, L.; Pei, Q.; Zhou, J.; Wan, S. Heterogeneous dynamic graph convolutional networks for enhanced spatiotemporal flood forecasting by remote sensing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 3108–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Shen, T.; Lin, Z.; Liu, H. Spatial pyramid based graph reasoning for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference On Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 8950–8959. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Xiao, L.; Yang, J.; Wei, Z. CNN-enhanced graph convolutional network with pixel-and superpixel-level feature fusion for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 59, 8657–8671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Kampffmeyer, M.C.; Jenssen, R.; Salberg, A.-B. Multi-view self-constructing graph convolutional networks with adaptive class weighting loss for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Tan, X.; Chen, G.; Zhu, K.; Liao, P.; Wang, T. Object-based classification framework of remote sensing images with graph convolutional networks. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 19, 8010905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; He, X.; Yao, M.; Wang, Z.; Hao, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, W.; Zhao, H.; Xia, C.; Li, J. Knowledge and spatial pyramid distance-based gated graph attention network for remote sensing semantic segmentation. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosta, X.; Kohfeld, K.E.; Bostock, H.C.; Chadwick, M.; Du Vivier, A.; Esper, O.; Etourneau, J.; Jones, J.; Leventer, A.; Müller, J. Antarctic sea ice over the past 130 000 years–part 1: A review of what proxy records tell us. Clim. Past 2022, 18, 1729–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, M.B.; Davies, M.; Hobbs, M.J.; Pering, T.D.; McGonigle, A.J.; Willmott, J.R. High-resolution hyperspectral imaging using low-cost components: Application within environmental monitoring scenarios. Sensors 2022, 22, 4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqrah, J.M.; Koo, Y.; Wang, W.; Xie, H.; Prasad, S. Toward Polar Sea-Ice Classification using Color-based Segmentation and Auto-labeling of Sentinel-2 Imagery to Train an Efficient Deep Learning Model. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.12719. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Huang, H.; Deng, P.; Li, Y. Deep feature aggregation framework driven by graph convolutional network for scene classification in remote sensing. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 33, 5751–5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wu, J.; Lai, Y.-K.; Qin, Y. Exploring and exploiting hubness priors for high-quality GAN latent sampling. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022; pp. 13271–13284. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, T.-Y.; Dollár, G. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Ji, S. Semantic image segmentation for sea ice parameters recognition using deep convolutional neural networks. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 112, 102885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Tang, X.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Wang, L. Detection of Antarctic surface meltwater using sentinel-2 remote sensing images via U-net with attention blocks: A case study over the amery ice shelf. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4301013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, A.; Roy, S.K.; Pradhan, B. e-TransUNet: TransUNet provides a strong spatial transformation for precise deforestation mapping. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2024, 35, 101221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, I.E.; Keegan, K.M.; Skiles, S.M.; Donahue, C.P.; Osterberg, E.C.; Hawley, R.L.; Marshall, H.-P. A cold laboratory hyperspectral imaging system to map grain size and ice layer distributions in firn cores. Cryosphere 2024, 18, 1925–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gelis, I.; Colin, A.; Longépé, N. Prediction of categorized sea ice concentration from Sentinel-1 SAR images based on a fully convolutional network. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 5831–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | File Name | Date | Cloud (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S2B_MSIL1C_20181031T191509_N0500_R027_T03CXV | Oct 2018 | 0.05 |

| 2 | S2B_MSIL1C_20191123T183459_N0500_R141_T05CMT | Nov 2019 | 0.00 |

| 3 | S2B_MSIL1C_20201209T191509_N0500_R027_T02CNB | Dec 2020 | 0.00 |

| 4 | S2B_MSIL1C_20231215T184459_N0510_R041_T04CDA | Dec 2023 | 1.06 |

| Bands | Central Wavelength (nm) | Bandwidth (nm) | Spatial Resolution (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Band 2—Blue | 492.1 | 66 | 10 |

| Band 3—Green | 559.0 | 36 | 10 |

| Band 4—Red | 664.9 | 31 | 10 |

| Parameters | Values | Parameters | Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimizer | Adam | Size limitation of SEGR | 32 × 32 |

| Learning rate | GCN layers | 2 | |

| Epoch | 200 | γ | 2 |

| Batch size | 8 | α | 0.3 |

| Method | PA (%) | IoU (%) | F1-Score (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Technology | Otsu | 81.43 | 66.59 | 79.94 |

| Deep Learning Model | SegNet | 91.79 | 86.52 | 92.78 |

| PSPNet | 94.72 | 90.75 | 95.15 | |

| DeepLabV3+ | 97.01 | 94.79 | 97.32 | |

| U-Net | 97.00 | 94.68 | 97.27 | |

| TransU-Net | 96.45 | 93.92 | 96.86 | |

| ABU-Net | 96.99 | 94.75 | 97.31 | |

| GEFU-Net | 97.52 | 95.66 | 97.78 |

| PA (%) | IoU (%) | F1-Score (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 96.63 | 94.10 | 96.96 | |||||

| Case 2 | 97.39 | 95.42 | 97.66 | |||||

| Case 3 | 97.10 | 94.85 | 97.36 | |||||

| Case 4 | 96.68 | 94.13 | 96.97 | |||||

| Case 5 | 97.39 | 95.36 | 97.62 | |||||

| Case 6 | 97.52 | 95.66 | 97.78 | |||||

| Case 7 | 96.84 | 94.46 | 97.15 | |||||

| Case 8 | 96.60 | 93.94 | 96.87 | |||||

| Case 9 | 96.06 | 93.19 | 96.48 | |||||

| Case 10 | 85.40 | 73.79 | 84.91 |

| Feature Size Limitation | PA (%) | IoU (%) | F1-Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 32 × 32 | 97.52 | 95.66 | 97.78 |

| 16 × 16 | 96.68 | 94.10 | 96.96 |

| 8 × 8 | 96.70 | 94.12 | 96.97 |

| 4 × 4 | 96.68 | 94.10 | 96.96 |

| 2 × 2 | 96.66 | 94.07 | 96.94 |

| Type | GCN Layers | Channels | Bias | Drop |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shallow | 2 | C-C/2-C | False | 0.1 |

| Medium | 4 | C-C/2-C/4-C/2-C | False | 0.1 |

| Deep | 6 | C-C/2-C/4-C/8-C/4-C/2-C | False | 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, W.; Geng, X.; He, X.; Hu, M.; Luo, J.; Bi, M. Antarctic Sea Ice Extraction for Remote Sensing Images via Modified U-Net Based on Feature Enhancement Driven by Graph Convolution Network. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13030439

Feng W, Geng X, He X, Hu M, Luo J, Bi M. Antarctic Sea Ice Extraction for Remote Sensing Images via Modified U-Net Based on Feature Enhancement Driven by Graph Convolution Network. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(3):439. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13030439

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Wu, Xiulin Geng, Xiaoyu He, Miao Hu, Jie Luo, and Meihua Bi. 2025. "Antarctic Sea Ice Extraction for Remote Sensing Images via Modified U-Net Based on Feature Enhancement Driven by Graph Convolution Network" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 3: 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13030439

APA StyleFeng, W., Geng, X., He, X., Hu, M., Luo, J., & Bi, M. (2025). Antarctic Sea Ice Extraction for Remote Sensing Images via Modified U-Net Based on Feature Enhancement Driven by Graph Convolution Network. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(3), 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13030439