Abstract

This study presents a systematic literature review of 307 peer-reviewed articles on collision avoidance approaches regarding the integration of maritime autonomous surface ships (MASSs) in coastal waters supply chains. The bibliographic data were retrieved from the ISI Web of Science Database and analyzed using Bibliometrix (version 4.3.3) in R and VOSviewer (version 1.6.20) to map the intellectual, thematic, and network structure of the research area. Three main research clusters were revealed through bibliographic coupling analysis: (1) autonomous collision risk management; (2) methodological approaches to maritime autonomy; and (3) adaptive maritime safety modeling. Content analysis of the identified research clusters enabled the development of a 68-item hierarchical task analysis (HTA) framework for MASS collision avoidance across three operational scenarios: (1) ship-to-object, (2) ship-to-ship, and (3) multi-ship. The results provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of research, identify methodological and safety interdependencies in autonomous navigation, and offer an organized and structured perspective to support the safer and more efficient integration of MASSs into coastal waters supply chains.

1. Introduction

The introduction of maritime autonomous surface ships (MASSs) entails a paradigm shift with the aim of enhancing the efficiency and safety of the maritime transportation system based, importantly, on artificial intelligence and remote operation so that human interference is minimized [1]. However, navigational risks, particularly those related to collision and grounding, continue to be salient issues despite these advances [2]. Although human error and human factors represent a substantial source of maritime accidents, recent research suggests that the often-cited figure of 80–90% lacks empirical foundation and varies between studies depending on definitions and methodological approaches [3,4,5].

While traditional vessels rely on the officer on watch and, in unconventional situations, the vessel’s captain, autonomous vessels must transfer operational control to remote operators when faced with ambiguous scenarios in the maritime environment [6].

The IMO defines MASSs as ships that can operate independently of human interaction to varying degrees, and they are characterized into four levels of autonomy: (1) automated processes with on-board human intervention, (2) remote controls with on-board human intervention, (3) remote controls with no on-board human intervention, and (4) fully autonomous operations [7]. However, these four autonomy levels were developed during the IMO’s 2019 Regulatory Scoping Exercise (RSE) for the purpose of a regulatory assessment and are not enforced class definitions. In the current considerations under the upcoming MASS Code, the IMO instead focuses on three core operating modes—manual, remote, and autonomous—that can be applied to a vessel throughout a voyage, but all three are presided over by the human master who remains in charge of operations overall [8].

While MASSs are anticipated to yield operational cost reductions, better human resource management, and potential environmental benefits, these benefits and advantages remain largely theoretical and have yet to be empirically verified. Nonetheless, issues such as safety and security remain of concern, notably when examined from a task analysis point of view [9,10].

Collision avoidance approaches regarding maritime autonomous surface ships (MASSs) have been the focus of recent research, with advanced control algorithms and human-factor analyses being the most prevalent [11]. These studies also represent advances in autonomous navigation architectures and the application of human task analysis to represent collision avoidance tasks [6]. Ref. [12] uses HTA for an analysis of crew decision-making stages and the identification of human-error pathways in remote-controlled ship operations. Despite these advancements, few studies have addressed the collision avoidance domain from the perspective of an integrated task structuring framework. The available approaches are fragmented, in the sense that they are usually domain-specific and emphasize specific components of the collision avoidance process, demonstrating shortcomings in a general hierarchical task structure.

To address this research gap, this systematic literature review has the primary goal of developing a hierarchical task analysis framework for MASS collision avoidance by identifying operational tasks, key decision points, and failure modes within the current literature, enabling the development of future safety protocols and informing the risk assessment process of the entire vessel system. This study is organized around three primary questions:

- RQ1: What tasks should be performed in response to collision avoidance in the MASS ship-to-object scenario?

- RQ2: What tasks should be performed in response to collision avoidance in the MASS ship-to-ship scenario?

- RQ3: What tasks should be performed in response to collision avoidance in the MASS multi-ship scenario?

The secondary research objectives are to (1) identify potential research clusters using bibliographic coupling, (2) examine thematics over time, (3) prioritize and reflect on future research directions for MASSs’ coastal waters supply chain integration, and (4) synthesize cluster insights in relation to the three research questions.

The rest of this study is structured such that Section 2 elaborates on the state-of-the-art literature regarding the supply chain integration of MASSs in coastal waters. The systematic literature review methodology is elaborated in Section 3. Section 4 presents the main results from the bibliometric analysis and cluster content evaluation. Section 5 clarifies the research questions in relation to the discussion and suggests future research directions. Section 6 concludes as a summation of the entire study via the main findings.

2. State-of-the-Art Literature Review on MASS Coastal Waters Supply Chain Integration

State-of-the-art (SotA) literature reviews summarize existing knowledge and propose paths forward for future research [13]. They describe the state of research at present, summarize the historical context that has led to our current understanding, and identify potential avenues for future work. This approach collates key developments in an innovative way, driven by modern-day insights rather than focusing solely on historical perspectives, unlike other types of review [14]. SotA articles are routinely used as a tool for synthesizing knowledge to formulate future research directions across a wide spectrum of disciplines, such as biomedical sciences, medicine, and engineering.

2.1. Autonomous Navigation in Maritime Coastal Waters

Successful autonomous navigation in maritime coastal waters depends on human factors, automated interfaces, and operator interaction with navigation systems. Mental stress increases human mistakes significantly despite the presence of technology in the maritime environment; thus, a clear depiction of navigational states facilitates operator decision-making and safety [15]. Therefore, it is critical that traditional traffic separation schemes evolve into structured maritime route networks to better govern scenarios involving close traffic, even though over-reliance on automation and misinterpretation of navigational data remain critical issues [16]. Ref. [17] emphasizes the importance of balancing active and passive monitoring for MASSs and suggests that the integration of explainable AI into human–machine interfaces could aid in making the systems more transparent, improve operator confidence, and allow for more efficient responses to problems.

In coastal waters, maritime autonomous surface ships rely on integrated sensing and planning systems. Radar, AIS, sonar, and UAV data feed AI algorithms that compute global routes and dynamic local paths, avoiding static hazards (shoals, banks) and nearby traffic in real time [6]. These systems may also incorporate real-time weather and current data to optimize routing. Human operators remain in the loop via dedicated shore control centers and advanced interfaces: VR/AR-enhanced displays and graphical UIs let remote watchstanders visualize the surroundings and assume manual control as needed [6,18]. Integration also depends on regulatory and port-side readiness: the IMO is finalizing a goal-based MASS Code (target year 2026) to address safety and legal gaps [19], and ports must upgrade digital infrastructure (smart VTS, automated berths) and procedures to accommodate autonomous vessels [20].

2.2. Maritime Coastal Supply Chain Integration

Short-sea shipping (SSS) is an increasingly important contributor to the logistics efficiency of coastal supply chains due to its favorable geographical positioning. About 60% to 70% of Europe’s industrial and production locations are located within a distance of 150 to 200 km from the coastline, making SSS a major complementary part in multimodal logistics networks [21,22,23]. However, there are many barriers to full integration and effectiveness even with these geographic advantages.

Inefficient logistics, in particular regarding cargo processing and inventory management, create serious competitive disadvantages for SSS, which often are worsened due to insufficient modal integration both for maritime and land transportation [21]. Ref. [22] also stresses the drawback of administrative burdens, lack of integrated door-to-door services, and complexity from frequent cargo transfer, reducing the advantages of SSS maritime logistics compared with other transport modes.

Ref. [24] recognizes substantial economic benefits of SSS, noting cost reductions of 10–20% compared with road freight transport. Although SSS solutions demonstrate these economic gains, uncertainty about the distribution of economic gains across stakeholders constitutes a key barrier to the broad adoption of SSS solutions. In Canada, strict vessel construction standards, and in the United States, the Harbor Maintenance Tax, represent regulatory barriers for SSS expansion as well [24]. In Australia, similarly restrictive licensing frameworks caused the market share of coastal shipping to decline markedly, from 44% in the mid-1980s to approximately 26% by 2008—thus reducing SSS’s competitive position relative to road transport [25].

Systemic issues complicate effective SSS integration into logistics networks, demonstrated by the fact that significant EU investments—such as the Marco Polo initiative—still have not produced an increase in market share away from road transport, as severe infrastructure bottlenecks remain unsolved, and failures to internalize external costs, such as congestion and pollution, continue [23].

Short-sea shipping has a significant advantage over road transportation regarding environmental benefits due to much lower emissions and higher fuel efficiency [26]. However, administrative barriers and inadequate port infrastructure continue to hamper its further development. Thus, appropriate regulatory simplifications and port infrastructure improvements are necessary [27]. Lastly, according to [28], targeted infrastructure investment and streamlining of operations are key processes in addressing such logistical and administrative barriers and facilitating expanded integration of SSS into multimodal logistics systems.

2.3. Operational Characteristics of Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships

Maritime autonomous surface ships present transformative potential for maritime transportation, with many industry-leading capabilities such as costs, safety, and sustainability. MASS implementation involves advanced guidance, navigation, and control systems with sophisticated sensor networks to ensure reliable autonomous navigation [29]. MASS deployment has the possibility of enhancing maritime safety via mitigation of human error [16]. Practical deployment, however, requires high investment rates, especially for shore-based infrastructure, allowing remote monitoring and management [30].

While the automation in MASSs reduces human error in ship operations, there is the potential for new system-mediated pathways for error to develop in shore-based operators, who are responsible for remote control, system calibration, and data interpretation [31]. One of them is collision avoidance, a key operational field mostly in dense traffic coastal waters. Very few publications exist in the literature concerning geographically designed collision avoidance strategies, which are greatly needed in confined maritime environments [32]. Furthermore, although autonomous systems substantially mitigate navigational accidents and incidents, there are non-navigational emergencies, such as fires or structural failures, that require rapid response capabilities from shore control centers and thus constitute an additional operational complexity.

Economically, MASSs may provide considerable operational cost savings; e.g., autonomous bulk carriers are expected to produce savings of around USD 4.3 million in a 25-year timeframe [33]. However, economic feasibility still relies on the reduction of fuel use, which constitutes as much as 70% of total operating expenses, along with some regulatory and insurance-related challenges [30,33]. Therefore, integrated infrastructure, advanced collision avoidance technology, and efficient risk assessment methodologies are paramount for successful MASS integration.

3. Research Methodology of Systematic Literature Review

This systematic literature review uses bibliometric analysis, an established research method in information science, which involves applying statistical tools to explore the scholarly literature both quantitatively and qualitatively [34]. The citation-based network method of analyzing bibliometric data identifies important authors, journals, articles, and institutions through citation and enables one to detect research clusters and emerging trends [35]. In a quantitative way, it systematizes scholarly outputs as well-structured knowledge frameworks and tracks their development through citation analysis, keyword mapping, authorship collaboration, and academic network representation [36,37]. In a qualitative manner, it is employs directed content analysis, which is a structuring validation exploration in these documents that guarantee interpretative warranty and replicability of the interpretation [36]. Consequently, bibliometric analysis is a core component of systematic reviews, as it offers a transparent, objective, and replicable base that increases analytical robustness [38].

3.1. Bibliometric Analysis Process

Bibliometrics is a statistical methodology that quantitively analyzes scientific publications and extracts the research trends, impact of the authors, and the thematic directionality of the publications based on citations and keywords [37]. It allows systematic exploration of the literature, highlights gaps in knowledge, and facilitates strategic research planning. It provides the scientific community with the benefit of timely and objective evaluation of research productivity and helps with impact measurement, evidence-based policy formulation, and informed resource allocation. In general, bibliometrics fosters more transparent decision-making, as well as advanced understanding of the dynamics of scholarly communication and academic research.

The bibliometric method provides a solid and quantitative approach for systematically mapping and analyzing complex interdisciplinary and cross-disciplinary research landscapes. As [39] shows, these methods uncover underlying scientific structures via visualization of scientific networks and clusters of publications, allowing the identification of dominant research trends, influential papers, and collaboration networks. In the field of maritime autonomy, the advantages are evidently supported by recent bibliometric studies. For example, Ref. [29] utilized VOSviewer and CiteSpace to visualize the intellectual structure of the field of research on autonomous shipping by clustering publications into several large themes and characterizing the main knowledge areas in the field of study. Additionally, Ref. [40] carried out a bibliometric review study of the MASS safety literature with collision avoidance included, identifying the top journals, research directions, the leading authors, and the most cohesive scientific networks. Similarly, Ref. [41] constructed a knowledge network of maritime safety studies on autonomous ships based on bibliometric mapping and identified the core research clusters, transitioning topics, and knowledge frontiers.

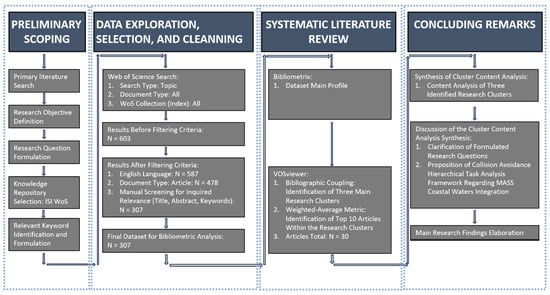

The workflow of the systematic literature review of MASS coastal waters supply chain integration is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the systematic literature review of MASS coastal waters supply chain integration.

The systematic workflow consists of four main research phases: (1) preliminary scoping; (2) data exploration, selection, and cleaning; (3) systematic literature review; and (4) concluding remarks. The first phase, preliminary scoping, defines the study’s scope and includes a primary search of the literature, the primary research questions, which are to develop a hierarchical task analysis framework for MASS collision avoidance (this will generate three main research questions). We chose the ISI Web of Science as the knowledge repository and combined keywords using Boolean operators.

Data exploration (phase 2) involves a detailed search in the Web of Science (search type: topic; document type: all; WoS collection: all), which resulted in 603 articles. Subsequent filtering for English language, article document type, and manual relevance screening resulted in a final dataset of 307 articles.

In the third phase, systematic literature review, a bibliometric analysis was conducted using two visualization tools: Bibliometrix and VOSviewer. Dataset profiling, annual publication trends, and thematic mapping were performed using Bibliometrix [36]. Bibliographic coupling through VOSviewer was used to extract the major articles and create three distinct research clusters consisting of the 30 articles selected [42].

In the last stage (concluding remarks), content analysis from the clusters is synthesized, research questions are clarified, and a proposed hierarchical task analysis framework for MASS coastal waters supply chain integration is elaborated along with key findings from the research.

3.2. Bibliographic Data Extraction Process

Collecting bibliographic information from multiple scientific databases is a key step in bibliometric analysis which ensures that the landscape of research is adequately mapped. The bibliometric dataset, used in this study over the last 23 years, was collected on 18 February 2025, from ISI Web of Science, a renowned scientific database in academia. Table 1 outlines the 14-step keyword search process that utilizes Boolean operators to generate specific results.

Table 1.

Keyword search process for MASS coastal waters supply chain integration.

Table 1 comprises 14 keyword-based search refinement steps to systematically narrow the literature dataset. The final step (Step 11) uses 11 keywords grouped into four segments: “Maritime Autonomous Surface Ship *”, “Autonomous Ship *”, “Risk Assessment”, “Safety Management”, “Collision Avoidance”, “Situational Awareness”, “Nearshore Operations”, “Coastal Navigation”, “Shore-Based Control”, “Port Approach”, and “MASS”. Step 12 applied an English-language criterion, reducing the dataset from 603 to 587 articles. Step 13 included only article-type documents, further decreasing the dataset size from 587 to 478. Finally, Step 14 involved manual screening for relevance, which narrowed the dataset to 307 articles.

3.3. Methodological Transparency and Parameter Specification

This subsection provides details on the utilization of methodological parameters. The lack of methodological detail can be addressed by explicit provision of VOSviewer settings in our bibliometric analysis [42]:

- Map creation: the utilization of VOSviewer (v1.6.20) enables the construction of science maps from bibliographic data [43]. This includes importing the Web of Science Core Collection export files as input data.

- Analysis type: this science mapping used the bibliographic coupling analysis on the document level. In the bibliographic coupling, documents are clustered on the basis of common references [44]. Thus, the greater the reference list overlap in two documents, the stronger their shared connection. This method clusters papers that belong to the same intellectual subject.

- Citation threshold: we set a minimum threshold of 15 citations per document for inclusion in the analysis. Thus, only scientific records exceeding 15 citations were retained for mapping [45]. This selection filter resulted in the retention of only the most influential and highly connected articles (core documents), thus enabling meaningful cluster formation of relevant articles. This citation threshold is a common strategy that is employed to focus on influential works and to facilitate the scientific interpretability of the network. In our case, 112 articles from the starting set met the ≥15 citation threshold and were grouped into clusters.

- Normalization method: we applied the association strength normalization approach for scientific network construction. By default, the VOSviewer software uses the stated normalization method to normalize link weights, accounting for differences in the number of connections each item (article) has [43,44,45,46]. This approach accounts for the concept of relative link strength and takes into consideration the fact that highly connected and linked articles do not outweigh articles with weaker but meaningful links.

- Clustering algorithm: we used VOSviewer’s built-in clustering algorithm (with the default resolution parameter and method association strength) to identify clusters of documents [47]. This algorithm partitions the network such that documents with stronger bibliographic coupling links naturally form coherent clusters (research themes) [48]. We report that three thematic clusters emerged in our analysis, corresponding to major subtopics in the field.

Contemporary bibliometric studies often report only minimal technical details—for example, mentioning a citation threshold for network inclusion—while omitting other parameters [49,50,51]. Here, in line with recent calls for more rigorous methodological reporting, we have detailed all key settings (data source, analysis type, unit, threshold, normalization, and clustering) to enhance transparency and reproducibility.

4. Main Results of the Systematic Literature Review: Research Cluster Analysis

This systematic literature review elaborated on 307 studies (1995–2025) on maritime collision avoidance published by 1181 scholars across 157 outlets. Approximately 88.93% of the studies are multi-authored (3.88 co-authors per study), and the average citations per publication comprise 19.88 counts. Moreover, 25.06% are international collaborative studies, indicating trans-national efforts in multi-topical studies (1317 author keywords).

In the final search of the ISI Web of Science database, a total of 307 articles related to MASS integration in coastal water supply chains were generated following the filtering process. A minimum of 15 bibliographic coupling citations per document was set as the threshold in VOSviewer to retain only the most strongly connected and impactful works, leading to a final dataset of 112 articles. Bibliographic coupling is a bibliometric method that links documents through shared references to the literature, which facilitates the generation of clusters in the literature [52]. This means that the documents are all likely to study a similar subject area; therefore, together they form a coherent research cluster.

Two fundamental properties of VOSviewer, total link strength and citation count, are employed in the equal-weighted average method to obtain information about how significantly and broadly the studies are related [53]. This composite metric served to pinpoint and select the 30 studies we focus on for more detailed content analysis. These studies were aggregated into three clusters each containing ten studies, as reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Selected and allocated articles for content analysis in respective research cluster.

These identified clusters reflect the current state-of-the-art in maritime autonomous surface ship (MASS) research and show a distinct temporal evolution of research interests. Cluster 1, autonomous collision risk management, includes recent papers, mainly published between 2020 and 2022, focusing on improving collision avoidance algorithms, as well as sensor fusion techniques for autonomous systems, indicating rapidly developing solutions in this subfield.

Cluster 2, methodological approaches for maritime autonomy, shows stable research development since 2016, with contributions related to systematic methodologies, including human–system integration, risk assessment frameworks, and automation reliability. Cluster 3, adaptive maritime safety modeling, illustrates that scholarly activity on the topic has recently gained momentum since 2020, with a focus on adaptive safety modeling approaches, predictive safety metrics, and dynamic risk modeling.

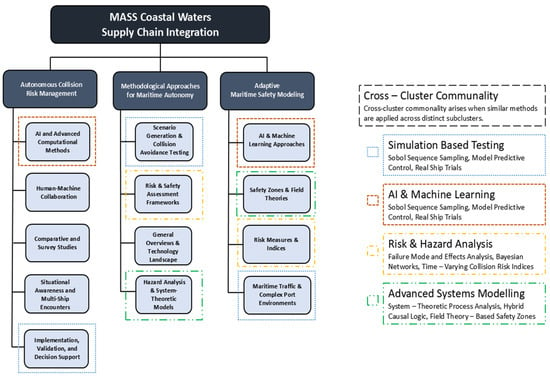

Since then, there has been an increase in research activity in these thematic areas, as highlighted in the aforementioned analysis. This trend indicates sustained interest and growth in the research field of MASS coastal waters supply chain integration. Data clustering results are shown as a diagram in Figure 2, which demonstrates a general inter-relationship between the clusters and their subclusters, indicating the main themes of research related to MASS coastal waters supply chain integration.

Figure 2.

Cluster and subcluster visual depiction.

Figure 2 elaborates on the cross-cluster communality of the research domain of MASS coastal waters supply chain integration; which can be defined across four cluster communalities, whereby the cross-cluster communality can also refer to the methodological overlap or the analytic toolset applied across two differing research clusters [35]: (1) simulation-based testing link between Sobol sampling, predictive control, and ship trials; (2) AI and machine learning, a cluster relying on high-end computation offering computational training systems; (3) risk and hazard analysis, which implements probabilistic methods (Bayesian networks and FMEA); and (4) advanced systems modeling, a cluster based in system theory paradigms and hybrid causal logic that also draws from field theory-based safety.

4.1. Autonomous Collision Risk Management

4.1.1. Advanced Computational Methods and AI

The main focus of this subcluster is on dynamic maritime navigation algorithmic techniques prioritizing collision avoidance and compliance. Chun et al. (2021) present a dynamic DRL-based navigation model combining tunable rewards, path-following precision, COLREGs compliance (Rules 13–17), and asymmetric ship domain for improved collision avoidance [54]. Integrating CPA risk assessments, their approach generates more precise collision-free paths compared with classical A * algorithms, thus enhancing deterministic maneuverability under dynamic MASS maritime traffic conditions. Lyu and Yin (2016) introduce a modified artificial potential field algorithm enabling real-time ship path planning with regard to static and dynamic obstacles in congested maritime environments [63]. This approach utilizes virtual repulsive forces and vessel maneuverability, ensuring safe, collision-free trajectories that automatically adapt to COLREG rules despite environmental complexities and computational limitations. Wang et al. (2020) propose a collision avoidance framework on the basis of MASS sensor fusion and advanced decision optimization to manage complex, dynamic multi-ship interactions at sea [69]. Their autonomous navigation system employs a finite state machine and velocity obstacle method, with effective adherence to navigation rules, and ensures vessel safety under unpredictable maritime conditions.

4.1.2. Human–Machine Collaboration

This subcluster is centered on HMI-led collision avoidance. Huang et al. (2020) point out the shortcomings of the current ship control systems and emphasize the missing integration between human operated control and automated collision avoidance systems [57]. They present an HMI-based collision avoidance system that integrates human and automated processes via an abstract interface, enabling the precondition for MASS traffic interactions and efficient navigation control. Wu et al. (2021) introduced the RA-CADMS algorithm for collision avoidance that integrates human cognitive biases through prospect theory and classifies maneuvers as cautious, aggressive, or neutral [74]. Empirical tests prove that RA-CADMS combines important characteristics of human decision-making behavior and leads to dynamic maritime environments being addressed with collision avoidance approaches specific to the individual operator’s risk preference.

4.1.3. Comparative and Survey Studies

This subcluster is about the integration of theory and practice in navigation. Li et al. (2021) apply bibliometric and expert elicitation methods, highlighting critical differences between models based on theoretical paths and general strategies of practitioners attempting to navigate an increasingly unstable maritime landscape [60]. They determined that theory-based research overlooks maritime realities such as natural disruptions, vessel engine maneuverability, and unpredictability and advised tighter collaboration with industry practitioners. Zhang et al. (2022) put forward a dynamic collision avoidance framework regarding fuzzy adaptive PID control and a motion plan with practical challenges for complex multi-vessel marine scenarios [80]. Their system integrates derived maneuverability restrictions and reality-based risk metrics (DCPA, TCPA) together to create an operationally presentable, COLREG-adhering navigation behavior that copes well with the unpredictability of external operating environments at sea.

4.1.4. Situational Awareness and Multi-Ship Encounters

This subcluster centers on occurrences of maritime collision incidents. Wang et al. (2021) categorized maritime collision incidents and determined that crossing (28.43%) and limited visibility (18.63%) factors should be classified as serious, indicating that scenarios where these factors should de described methodologically are understudied regarding present MASS navigation technology [71]. Their smart closed-loop collision avoidance system based on sensor fusion, risk assessment, and COLREG-based strategies was proven to be capable; nevertheless, a significant effort in developing MASS technologies is needed to adequately operate in constrained and dynamic marine environments.

4.1.5. Implementation, Validation, and Decision Support

This subcluster centers on maritime autonomous decision-making. Wang et al. (2023) propose a maritime autonomous navigation decisions system (MANDS) that encompasses route-keeping, collision avoidance, route optimization, and route back as hierarchical tasks [71]. The adaptive nature of MANDS is showcased through extensive scenario-based simulations that illustrate the ability of MANDS to respond to operational hazards and undergo variations in context in a manner that supports resilient real-time navigation decision-making for true autonomous maritime operations. In this regard, Zhang et al. (2021) recommend including S-100 communication standards, real-time sensor data, and AI-based predictive decision-making under an overall collision avoidance system within an autonomous ship [77]. By integrating novel PID controllers and deep learning methods, their method provides disturbance-based hazard avoidance by minimizing changes to the vessel trajectory, thereby improving maritime efficiency, safety, and reliability.

4.2. Methodological Approaches for Maritime Autonomy

4.2.1. Scenario Generation and Collision Avoidance Testing

Risk control scenarios are the main focus of this subcluster. Bolbot et al. (2022) propose a framework for automatic scenario detection using Sobol sampling and t-SNE visualization to systematically capture the vulnerable situations of maritime traffic collision risks [55]. The methodology of the scholars’ clusters risk factors such as time to collision, minimum safety distance, and complex vessel interactions; in addition, they suggest that risk metrics be standardized and explore the complex domain of COLREG compliance. Johansen et al. (2016) proposed a model predictive control-based framework for collision avoidance that systematically evaluates control actions, environmental disturbances, and uncertainties while respecting the COLREGs compliance constraints [67]. Their method computes ship maneuvers to minimize the probability of collision risk and handles multi-object interactions successfully, demonstrating realistic normalcy and adherence to regulatory requirements in maritime navigation cases.

4.2.2. Evaluation Frameworks for Risk and Safety

Maritime risk and safety are the main research elements of this subcluster. Chang et al. (2021) focus on prominent MASS operating risks such as interactions with manned vessels, cyberattacks, human mistakes, extreme weather events, and communication failures [58]. The research adopted an integrative approach based on hybrid FMEA, ER, and RBN, providing a thorough assessment of risk levels from all threats involving interactions with manned vessels, cyber threats, human error, and equipment failure. Meanwhile, Fan et al. (2022) developed a risk-based operational mode framework to perform manual, remote, and autonomous comparison based on interval-valued risk metrics collected from accident records and expert judgment [61]. Their results further highlight the heterogeneous nature of risk across the operational modes and reiterate the notion that safety must be considered in context, while offering suggestions for how to refine the operational rules that govern maritime navigation systems. Wróbel et al. (2020) review safety indicators in the context of collision avoidance, intact stability, and communication in isolation, drawing attention to the lack of integrated maritime safety frameworks. Scholars summarize combining traditional metrics (e.g., GM stability, DCPA/TCPA collision metrics) with modern real-time measures (e.g., velocity obstacle approaches) and cutting-edge secure communications technologies [75].

4.2.3. General Overviews and Technology Landscape

This research subcluster focuses on cross-disciplinary maritime autonomy. Gu et al. (2020) performed a systematic literature review on autonomous maritime vessels and found that the research interest in this field has been consistently increasing [64]. Results indicate that 41% of autonomous vessel research focused on navigation control, while 25% focused on safety concerns, making these the two most prevalent themes in the current literature. Significant research gaps remain across the domains of transportation, logistics, economics, and social impacts—research opportunities thus traverse multiple lines of cross-disciplinary scholarship. Jovanović et al. (2024) employed VOSviewer and CiteSpace to analyze over 1000 publications on autonomous and unmanned shipping (2010–2023), delineating five principal research clusters: navigation and risk assessment, collision avoidance, control systems, machine learning applications, and path planning [29].

4.2.4. Hazard Analysis and System-Theoretic Models

Uncertainty and causal logic integration for proactive autonomous safety is the main focus of this research subcluster. Wróbel et al. (2018) use system-theoretic process analysis to deal with uncertainty, implementing a Virtual Captain module that combines inputs from environmental and internal sensors, as it relates to autonomous ship system safety [79]. Because they are aware of large uncertainties in autonomous ship design, they argue that these should be explicitly incorporated in safety models for the purpose of informed decision-making and to improve proactive vessel control. Zhang et al. (2022) propose a hybrid causal logic model for the early detection of hazards in MASSs. This model is based on event sequence diagrams, fault trees, and Bayesian networks [80]. This layering model presents the vulnerabilities in decision-making, perceptual, and execution phases, where isolated failures can result in catastrophic maritime operational environments.

4.3. Adaptive Maritime Safety Modeling

4.3.1. AI and Machine Learning Approaches

Fiskin et al. (2021) state that human errors are responsible for the majority of maritime collisions, and therefore, they implement a collision avoidance decision-support system based on genetic algorithms and fuzzy logic to help minimize those types of accidents [56]. The framework utilizes both expert-based variable identification, as well as scenario validations, and is successfully applied in simulation environments, as well as in real-world autonomous surface vehicle deployments. He et al. (2023) proposed the MPAPF algorithm to solve the dynamic ship motion planning optimization problem, improving the ability of collision avoidance in a complex multi-obstacle marine environment [62]. MPAPF, while outperforming traditional methods in performing earlier and safer maneuvers, nevertheless, in practice, must be balanced regarding complexity and prediction accuracy tradeoffs. Li et al. (2018) compared twelve trajectory prediction methods and concluded that deep learning is a generalizable and powerful approach for maritime navigation with complex ship trajectories [68]. We confirm that the transformer and Bi-GRU architectures yield the best performance of all investigated deep learning methods, thus establishing their ability to effectively handle highly complex predictions of maritime vessel trajectories.

4.3.2. Safety Zones and Field Dimensions

This subcluster focuses on dynamic collision risk modeling enhancing maritime safety. Gil (2023) proposed a collision avoidance dynamic critical area (CADCA), a dynamic deterministic safety area that adapts its shape based on vessel maneuverability and rudder angle [59]. Data from simulations reveal that rudder angles have a considerable effect on the extent of CADCA dimensions, while vessel speed has a more minor effect, establishing the practical utility of CADCA for both manned and autonomous maritime operations. Qiao et al. (2021) presented a new framework in which a quaternion ship domain (QSD) and asymmetric Gaussian functions are used to represent the instantaneous, interpretable static collision risk for tasks that involve autonomous collision avoidance of ships [76]. This high-fidelity field-theoretic perspective improves maritime safety using explicit collision avoidance regions and thereby provides a physically consistent description of intricate multi-ship, nonlinear, and probabilistic risk scenarios that goes beyond classical methodologies.

4.3.3. Risk Measures and Indices

The main focus of this subcluster is collision risk evaluation. Huang and van Gelder (2020) proposed a total collision risk (TCR) algorithm, overcoming two-ship measurement limitations by testing the algorithm on the ship maneuverability interactions in developing and multi-ship interactions [65]. While earlier methods failed to account for maneuverability, TCR provides a more realistic description of maneuverability considering constraints imposed by the dynamic actions of neighboring vessels that affect available options. Li et al. (2021) proposed the rule-aware total collision risk (R-TCR) concept, adding consideration of COLREGs compliance, seamanship, and maneuverability embedded in a holistic dynamic collision risk assessment framework with an eye on next-generation ethical behavior [70]. R-TCR presents superior interpretability of physical meaning than the previous annotations (with finer sensitivity to multi-ship situations), is more predictive for active prevention of collision and presents fewer false alarms.

4.3.4. Complex Port Environments and Maritime Traffic

The main focus of this subcluster is maritime risk assessment. Xin et al. (2023) propose a multi-scale collision risk assessment framework that combines complex network theory with CPA-based models to evaluate maritime safety at different spatial scales [82]. This approach utilizes multi ship traffic networks and composite risk indices extracted through the fuzzy clustering iterative methodology that can represent density, intensity of interaction, and multi-ship dynamics very effectively. Xin et al. (2023) develop a composite similarity metric which combines conflict criticality and the geographic compactness, creating homogeneous clusters in space for detecting conflicts with improved maritime traffic management [79]. With innovative graph-cut partitioning, this function can help to find optimal vessel routes, separate high-risk clusters, group conflicting vessels, and greatly enhance interpretability and situational awareness in complex waters.

5. Discussion: Clarification of Main Research Questions Regarding MASS Coastal Waters Supply Chain Integration

The content analysis identified four universal categories for MASS collision avoidance: (1) collision risk assessment, (2) collision avoidance method implementation, (3) route planning and real-time adaptation, and (4) system execution and validation. Taken together, these structured tasks succinctly cover the key operational processes and provide insight into the research questions in focus:

- (RQ1) What tasks should be performed in response to collision avoidance in the MASS ship-to-object scenario?

- (RQ2) What tasks should be performed in response to collision avoidance in the MASS ship-to-ship scenario?

- (RQ3) What tasks should be performed in response to collision avoidance in the MASS multi-ship scenario?

5.1. Formal Modeling, Evaluation, and Validation of MASS Collision Avoidance Subtasks

5.1.1. Ship-to-Object (Allision)

Collision Risk Assessment

Static obstacles (e.g., piers, shorelines) are represented by zones where distances and tolerances are calculated as for ship domains [83]. Recent methods utilize uniform risk functions for both static and moving hazards—by way of illustration, a safe reinforcement learning method explicitly characterizes a risk function to mixed object scenarios and is validated to evaluate risks to static objects accurately in simulation [84]. Validation is mainly based on simulated harbor cases since it is very problematic to perform allision tests on a full scale.

Collision Avoidance Method Implementation

The avoidance of immobilized obstacles would generally be carried out using path-planning algorithms to guarantee clearance [85]. Advanced algorithms resolve problems such as the local minimum near the obstacles; e.g., an improved artificial potential field method (taking into account COLREGs priorities) results in 71.8% smoother avoidance around static hazards than the original one, as it eliminates oscillations and deadlocks [86]. These methods are tested on complex maps with static obstacles (e.g., harbor layouts), ensuring that the ship in question can safely reroute around stationary hazards without making impractical detours.

Route Planning and Real-Time Adaptation

Global path planners (graph search or optimization algorithms) compute initial paths which avoid known static hazards and are then adjusted by real-time modules if new obstacles are presented [87]. For instance, many systems will plan based on charted shallow areas and structures but will replan on the spot if the radar/LiDAR sees something uncharted. An adaptive model predictive control strategy is employed to perform early actions based on predicted trajectories around an obstacle [88], and dynamical replanning logic is verified in simulation to handle abrupt stationary obstacles. Success is determined by whether the system can adjust course quickly enough and still arrive efficiently to the destination, a feat that recent simulation efforts suggest is possible with minimal route deviation time.

System Execution and Validation

Allision avoidance capabilities are limited in full-scale trials; however, they implement proxy methods. A half-scale automated ferry in Trondheim successfully conducted automatic crossings and docking, and it avoided piers and other static objects under real port conditions [89]. This field test demonstrates that collision avoidance systems can be implemented on real boats, connecting with sensors and thrusters to avoid static obstacles. As a rule, static-object avoidance methods are first tested on high-fidelity simulators or test basins and verified in field trials before deployment.

5.1.2. Ship to Ship (Collision)

Collision Risk Assessment

Other ship encounters are evaluated with computational risk models based on relative motion and uncertainty. Recent work has used formal methods to address sparse data and complex causation. Ref. [90] established a fault tree analysis–fuzzy Bayesian network model to carry out risk assessment of collisions for MASSs operating in uncertain conditions; the model can convert factors causing fault (sensor failure, human oversight during remote control) into probabilities. The output of this model (collision risk likelihood) is validated in sensitivity analyses and scenario-based tests and identifies the significant risk components with which the thresholds for performing avoidance actions can be determined. In several works, traditional metrics (e.g., closest point of approach) are directly employed as an instantaneous risk signal in the sense that they are related to real encounters or full-mission simulators and are to be calibrated so as to guarantee the issuance of timely alarms by the risk assessment module [86].

Collision Avoidance Method Implementation

Algorithms are required to be able to produce COLREGs-compliant maneuvers for two-ship encounters. The subsets of rule- and learning-based approaches have been formally defined. Ref. [91] incorporates domain knowledge in a deep learning framework (RGVSL), where their vision inputs guided by COLREGs can achieve more than 90% decision accuracy in several encounter situations without retraining. This demonstrates a strong rate of success for collision avoidance decisions. Similarly, a model predictive approach (IQMPC) employs the target ship’s desired course, and a quaternion ship domain, to generate avoidance maneuvers while adhering to give-way/stand-on obligations [92]. Such methods are evaluated using simulation of the ship in question to determine whether deviations of the ship in question are aligned with COLREGs rules, such as turning to starboard in a head-on situation, to prevent and avoid collisions successfully. Validation attempts have proven that these implementations abide by the rules safely and are free of any conflicting behavior at runtime, at least in test scenarios.

Route Planning and Real-Time Adaptation

When targets are moving, the route of a ship has to adjust continuously. Contemporary collision avoidance strategies combine short-term maneuvering with long-term route adjustments. For example, a model predictive control system could predict the trajectory of the other vessel and adjust the path in advance so that last-minute course changes are reduced [92]. Other approaches use velocity obstacles or dynamic programming to update the heading at each time-step as the target moves. Performance is evaluated in metrics such as passing distance and time to collision for the entire encounter [93]. Simulated trials with different course and speed adjustments of the target ship confirm that adaptive planners maintain a safe distance by deforming the route gradually over time rather than making last-minute sharp turns. Thus, formal assessments have demonstrated that algorithms of this type are able to slow down smoothly or make deviations and return to the original route trajectory when the collision threat is clear.

System Execution and Validation

Ship-to-ship collision avoidance, in some cases, has advanced to real-world trials. In particular, full-scale experiments of an autonomous ship targeting a manned ship showed highly successful collision avoidance maneuvers: a system which was aware of other vessels’ intentions via predictive planning and Bayesian intent inference ensured that the unmanned craft followed COLREG Rules 7, 8, and 13–17 in different encounter situations [94]. This can represent a successful example of field validations of a probabilistic avoidance system, and it demonstrated that the modeled logic is consistent with real sensor measurements and ship dynamics [95]. In general, most collision avoidance algorithms undergo extensive simulation (and sometimes man-in-the-loop simulator studies with experienced mariners) before limited field trials. Correspondence between simulation and early sea trial results (e.g., compliance with the collision regulations and no near-misses during trials) provides some assurance of the validity of these decision models for ship-to-ship encounters.

5.1.3. Multi-Ship Encounters

Collision Risk Assessment

Multi-vessel encounters are more complex; therefore, the latest literature considers the collective risk of all neighboring target ships. A representative approach is the regional multi-ship risk model, which initially divides vessels into encounter groups and then calculates a “comprehensive collision risk value” (CCRV) for each ship according to hierarchical classification of the encounter conditions [96]. This makes it possible to quantify the cumulative risk in congested traffic. On a grid map, the model also finds collision “hotspots.” Validated against AIS traffic data, the framework correctly identified high-risk zones and situations, which correspond to some already-known congestion areas in the Yangtze River estuary [96]. Such concordance with actual data lends credence to the model. This type of validation with real-world data helps confirm the trustworthiness of the model. Multi-ship risk assessment logic may be considered plausible if it can predict the past history events of collision clusters and near-misses in traffic intensive waterways and if it can instruct an unmanned ship to make a decision about the length of time that should elapse before it should switch from normal cruising to an avoidance mode based on multi-target warning.

Collision Avoidance Method Implementation

The problem of how to avoid multiple ships in a multi-ship context is generally solved using pairwise decomposition or cooperative multi-agent methods. Conventional approaches decompose the complex situation into several two-ship encounters and solve them iteratively based on priority and CRI, yielding a resolution when the primary ship resolves the most dangerous scenario first (as explained for rule-based systems). The more sophisticated techniques are based on cooperation: for example, that of Xie et al. (2024). Now, in fact, we have a deep reinforcement learning technique for multi-vessel collision avoidance that assumes that all ships are agents, that applies COLREGs-compliant reward function, and that even separates the outmaneuver phase and route recovery phase for each ship [97]. The multi-agent DRL was evaluated in simulation, and all vessels selected safe and rule-compliant maneuvers without deadlock. The assessment included evaluation of new collision-free performance in dense environments, COLREGs compliance rate, and trajectory smoothness, and the DRL-based approach proved to be efficient and generalizable for various randomized multi-ship encounter simulations, representing a potential solution in complex encounters.

Route Planning and Real-Time Adaptation

In multi-ship encounters, adaptive cooperative route planning recalculates optimal paths. Most replanning processes are iterative and refine the routes according to expected target ship movements. Extended A * and RRT algorithms integrate collision prediction in dynamic motion planning [62]. Cost functions combine predicted positions and time to collision to bound safety margins. The course recovery modules ensure a smooth return to the original trajectory after maneuvering [97]. These planners are validated using Monte Carlo simulations with slight variations, considering real-time feasibility.

System Execution and Validation

For safety reasons, multi-ship avoidance systems are very rarely tested at full scale with large numbers of moving vessels, although controlled trials have been conducted. In 2024, a field test of four USVs was performed to demonstrate a proof of concept. An autonomous swarm of USVs was able to coordinate to transit together without colliding with one another. This provided evidence that the decision-making algorithms can scale to many agents in a physical environment, at least for small speeds and simple encounters. In general, multi-ship approaches have been thoroughly tested and evaluated in simulation, using real traffic data playback rather than in real trials at sea. To gain confidence, researchers demonstrate that their algorithms safely avoid collisions in tens of thousands of multi-ship encounter simulations and incrementally scale up the complexity in field demonstrations. The congruence of these findings—no collisions occurred in simulations, and none occurred in real trials at a limited scale—suggest that multi-ship collision avoidance strategies are sound, though they will need to be validated further (including in high-density open-water scenarios).

5.1.4. Allocations by Universal Key Task and Collision Subtype

Table 3 presents the allocations of subtasks, key decision points, and potential failure modes for each MASS scenario.

Table 3.

Allocations by universal key task and collision subtype.

The following research questions are further clarified with the insights presented in Table 3 in the consequent subsections.

5.2. Research Question Number 1: What Tasks Should Be Performed in Response to Collision Avoidance in MASS Ship-to-Object Scenarios?

In the ship-to-object scenario, MASSs detect static hazards, such as piers or offshore structures, using multi-sensor fusion (radar, lidar, AIS, cameras) to accurately update nautical maps and perform precise domain modeling [54]. Upon identifying potential allisions, MASSs apply deep reinforcement learning or modified artificial potential field algorithms to execute minimal-deviation avoidance maneuvers, accounting for mechanical constraints [63]. Sensors then reconfirm safe clearance before resuming planned trajectories [76].

5.3. Research Question Number 2: What Tasks Should Be Performed in Response to Collision Avoidance in MASS Ship-to-Ship Scenarios?

In ship-to-ship collision scenarios, MASSs first receive heading, speed, and intention information of other ships from AIS, radar, and cameras [54,67]. Collision risks are quantified using DCPA/TCPA calculations with COLREGs (Rules 13–17) used for navigation roles [63]. The avoidance subtasks utilize velocity obstacle methods, potential field methods, or multi-agent DRL algorithms, resulting in a coordinated maneuver execution, which is confirmed by sensors to ensure safe return to the initial route after collision risks are avoided [67,80].

5.4. Research Question Number 3: What Tasks Should Be Performed in Response to Collision Avoidance in MASS Multi-Ship Scenarios?

In multi-ship collision scenarios, MASSs combine radar, AIS, and camera data to monitor the positions and intentions of multiple vessels simultaneously [54]. Dynamic collision threats are prioritized to capture the fact that rapid evasive maneuvers toward one vessel may increase the threat from others [55,81]. Using hierarchical and multi-agent DRL frameworks, overlapping velocity obstacles are processed to select either global or segmented maneuvers, with the routes continuously recalibrated and separation effectiveness validated across dynamic maritime environments [63,71].

5.5. MASS Collision Avoidance Hierarchical Task Analysis Framework

Hierarchical task analysis (HTA) decomposes complex tasks hierarchically into goals, subgoals, operations, and plans [98]. The main goal of HTA is to describe the actions and thoughts (intended behaviors) that must be performed by humans to enable the system to meet the desired objectives. HTA entails identification of the overarching system goals and subgoals that can be appropriately subdivided and identified, analysis of required individual operations, and sequencing and conditional interdependencies of these operations [98,99]. HTA is applied across various scientific and industrial contexts as a basis for guiding interface design, job structuring, training, the development of procedural protocols and workload assessments, optimizing human–machine interaction, and enhancing overall system safety [98,100,101].

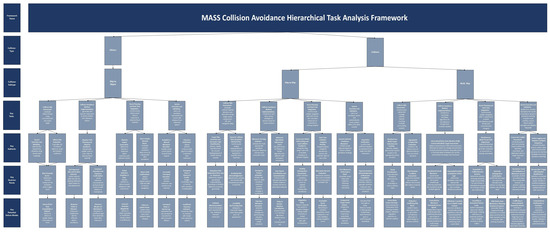

Using hierarchical task analysis (HTA), this study proposed four universal tasks that are vital for MASS collision avoidance, namely, collision risk assessment, collision avoidance method implementation, route planning and real-time adaptation, and system execution and validation. These tasks were broken down into subtasks, decision points, and potential failure modes, yielding 68 unique elements. The framework is developed for three scenarios: ship to object, ship to ship, and multi-ship. As we determined that each scenario requires its own specific analysis, the complex operational dependencies that are important for implementing effective autonomous maritime collision avoidance solutions are highlighted. The MASS collision avoidance hierarchical task analysis framework is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

MASS collision avoidance hierarchical task analysis framework.

Collision avoidance strategies for maritime autonomous surface ships (MASSs) are scenario-dependent depending on the following scenarios: ship to object, ship to ship, and multi-ship. Regarding ship-to-object scenarios, MASSs use multi-sensor fusion techniques to identify obstacles, estimate the risk of allision, and carry out domain modeling—activating risk thresholds only when needed and dealing with sensor errors or delays in recognition appropriately [54,63]. In ship-to-ship collision avoidance, a combination of target vessel detection, activity classification according to COLREGs, collision risk assessment (DCPA/TCPA), and tactical maneuvering for decision-making using, e.g., deep reinforcement learning (DRL) or artificial potential fields (APF) while taking into account possible misinterpretations of regulations or unreliable AIS data, is present [67,69]. Multi-ship encounter scenarios require groupings driven by hierarchical and/or finite-state machine (FSM) strategies that calibrate concurrent risk aggregation, threat prioritization, and coordinated maneuvers, with careful monitoring of sensor fusion overload, contradictory commands, and late alerts. Such structured methods can guarantee solid collision management capabilities in complex maritime scenarios.

5.5.1. Collision Avoidance Algorithm Mechanisms

The collision avoidance concept is based on combining various algorithm types to ensure feasible and safe COLREGs-compliant solutions for MASS navigation. In accordance with the literature, the algorithms are grouped into (1) deep reinforcement learning, (2) multi-agent coordination, and (3) motion planning [55,64,74].

Deep reinforcement learning algorithms model collision avoidance as Markov decision processes and design states, actions, and reward functions which incorporate COLREGs-compliant incentivization and penalty schemes using proximal policy optimization networks [74]. These algorithms are designed to enable reactive collision avoidance strategies by autonomous vessels through interacting with complex maritime systems on a reward basis.

Multi-agent coordination algorithms include coordination methods such as centralized supervisory architectures that plan global avoidance maneuvers at shore-based control centers but require high-latency communication response times and distributed hub-and-spoke models that permit shore-to-ship negotiation for safe MASS trajectories [63]. Phantom-ship models or eccentric-ship domains are presented to satisfy the requirement of Rule 14 under head-on encounters, while vessel-platooning algorithms show possible savings of fuel during multi-vessel convoys [54].

Motion planning algorithms include a grid-based A *, which finds the shortest paths but lacks kinematic realism; hybrid APF–A *, which overcomes local minima by combining artificial potential field algorithms with a heuristic search; model predictive APF, which considers receding-horizon optimization within potential landscapes; rapidly exploring random trees, which sample high-dimensional dynamic spaces for feasible ship trajectories; velocity obstacle algorithms, which define admissible velocity sets for proactive risk mitigation; and model predictive control algorithms, which solve constrained receding-horizon non-linear programs by integrating ship dynamics, maneuverability limits, and regulatory rules. In addition, the ColAv_GA hybridization of genetic searching with fuzzy-logic-defined ship domains can be considered in bridge simulators and autonomous surface vehicle experiments for maneuver optimization in compliance with COLREGs Rules 8(d) and 16. Together, these algorithm types facilitate reasonable tradeoffs between computational efficiency, regulatory conformity, and environmental adaptability, thus laying the groundwork for more comprehensive investigation of MASS collision avoidance in future work [80].

5.5.2. Legal and Regulatory Implications for MASS Coastal Waters Integration

Fully autonomous ships have to adhere to the 1972 COLREGs, even though many of the rules are based on the presence of a master on board and “the ordinary practice of seamen”, which autonomous systems inherently lack [102]. Regulatory reviews have shown significant challenges in applying COLREGs to MASSs and propose only minor definitional changes rather than quantification of normative rules regarding unmanned vessels.

In particular, COLREG Rule 2(a) explicitly mentions ship masters and crew, whereas algorithmic encoding of “ordinary practice” constitutes an unresolved technical problem [103]. The allocation of liability for MASS collisions is a complex matter, since traditional fault-based doctrines, such as negligence, have limited relevancy to situations in which there are no personnel on board vessels [104]. Most scholars agree that responsibility for incidents may be attributed to vessel owners, technology manufacturers, software designers, and remote operators, because of which, new liability regimes will be required. Some commentators suggest imposing strict liability regimes that hold owners and equipment suppliers accountable irrespective of fault to address gaps when human error is absent. At present, no mature certification regime is available for MASSs; however, IMO’s eventual goal-based nonmandatory MASS Code will establish high-level safety objectives and assign verification measures to industry [7].

Classification societies, such as DNV, ABS, and RINA, have introduced provisional class notations using formal safety assessments, failure mode analysis, and strict cybersecurity measures for the verification of autonomous systems [105]. There are still deficiencies when it comes to STCW guidance regarding defining training protocols for remote operators and harmonizing national regulations; thus, calls have been made to seek single pathways to certification and to clarify that further regulatory research is necessary. SOLAS and STCW conventions required amendments to accommodate MASS-specific requirements, highlighting the necessity for international regulatory harmonization [106].

5.5.3. Coastal Logistics Case Studies

In a high-fidelity discrete-event logistics simulation of short-distance feeder shipping in a Norwegian coastal corridor, 60–110 TEU small battery-powered daughter vessels proved to be cost-effective and produced significantly less emissions and external costs in comparison with conventional truck transport [107]. An independent live trial in Belgium validated the “Zulu 4” autonomous barge, which autonomously navigated a 16.5 km inland waterway route—including locks, bridges, and marina approaches—under remote supervision with unsupervised auto-docking and auto-navigation capabilities, reliably proving its capability in high-density nearshore logistics corridors [108]. Moreover, a 2025 high-fidelity project of an under-actuated vessel docking operation under the assistance of autonomous tugboats demonstrated the robustness and stability of the model predictive control-based framework in critical berthing operations under various environmental conditions, demonstrating practical feasibility in complex port operations [109].

The MUNIN project demonstrated the technical feasibility of a feeder dry bulk carrier for autonomous operations, as well as scheduling optimization and reduced operational costs on the basis of machine learning-based route optimization and COLREGs-compliant collision avoidance [110]. Lastly, the Rolls-Royce-led autonomous ferry trial in Finnish coastal waters demonstrated accurate autonomous berth approaches, successfully achieving zero-intervention docking in restricted port environments [111]. These case studies demonstrate that the integration of MASS can improve the reliability, safety, and environmental sustainability of maritime coastal logistics systems.

5.6. Future Research Directions Regarding MASS Coastal Waters Supply Chain Integration

Maritime autonomous surface ships (MASSs) are studied for their potential to improve efficiency and safety in coastal shipping. Technological advancements in the maritime industry are enabling the integration of MASSs into multimodal logistics systems and supply chains—a promising prospect [6]. However, obtaining the benefits of MASSs requires a substantial improvement of port infrastructure; ports are required to develop and apply interoperable systems and automation such as auto-mooring and digital traffic management that can accommodate autonomous ships [20]. Operational safety considerations are relevant as well; development of robust collision avoidance and situational awareness systems that match the human navigator performance will remain a priority for MASS safety [20]. Furthermore, regulatory harmonization is a significant challenge. International organizations such as the IMO are scoping convergent MASS rules that can reconcile potential legal and liability shortcomings across jurisdictions.

Advanced sensor fusion models for challenging coastal short-sea environments are being developed, and automated berthing precision and robustness can be significantly enhanced when LiDAR, RTK, GPS, and inertial information can be suitably integrated [112]. In parallel with this, communication systems such as e-navigation with the VHF Data Exchange System are being developed for resilient real-time data transfer, supporting undisrupted ship–shore data exchange and further contributing to situational awareness. Preliminary cost–benefit estimates suggest that the deployment of MASSs on short-sea routes can increase cargo volumes and reduce road traffic by offloading freight from highways, as well as reduce long-term operating costs [113]. Lastly, human–machine interface strategies for maintaining transparency and decision support for shore control center operators include testing remote-control interfaces that provide clear feedback on system state to shore operators, allowing them to maintain high awareness and to intervene when necessary [114].

6. Conclusions

Collision avoidance, within the context of MASS integration into coastal shipping supply chains, includes methodological approaches that mainly identify, assess, and mitigate navigational hazards to ensure safe autonomous ship operations. This study conducts a systematic literature review via bibliometric analysis on a dataset of 307 peer-reviewed articles sourced from the ISI Web of Science database and selected via the combined application of systematic keywords and Boolean search terms.

Furthermore, the dataset of 307 articles relevant to the study was subsequently filtered via citation counts for bibliographic coupling analysis. Network visualization of 112 articles via bibliographic coupling analysis, each meeting a threshold of 15 bibliographic coupling citations, revealed three distinct research clusters. The three identified research clusters are (1) autonomous collision risk management, (2) methodological approaches for maritime autonomy, and (3) adaptive safety maritime modeling. The content analysis of the identified three research clusters established the conditions for developing the 68-item MASS collision avoidance hierarchical task analysis framework.

The framework is guided by three defined research questions specifically addressing ship-to-object, ship-to-ship, and multi-ship scenarios, respectively, based on observed gaps in the literature. In the ship-to-object scenario, tasks are prioritized regarding static object or obstacle identification, object collision risk calculation, local route planning, and real-time adaptive maneuvers such as autopilot execution, clearance validation, and addressing sensor inaccuracies or delayed responses. In the ship-to-ship scenario, emphasis is placed on target detection, COLREG-based risk assessment (Rules 13 to 17), dynamic maneuver strategy selection, real-time route adjustments, verification of maneuver effectiveness, and proactive resolution of role misinterpretations or AIS-related inaccuracies. The multi-ship scenario integrates real-time concurrent multiple target management, hierarchical decision-making frameworks, simultaneous route adaptation, and multi-threat evaluation and addresses potential computational overload, contradictory ship directives, and complex sequencing errors.

Future research directions on MASS coastal supply chain integration should place an emphasis on transportation system elements such as multimodal logistics connectivity, specialized port infrastructure, regulatory harmonization, tailored collision avoidance technologies, robust communication protocols, economic impact analysis, and human-centered interface development for enhanced safety and operational sustainability of the coastal supply chain system.

The limitations of the study are as follows. The bibliometric analysis employed a cut-off threshold of 15 citations per document and might have omitted recent yet influential studies. The dataset was based only on articles indexed in the Web of Science database, which introduces potential database bias by omitting relevant studies indexed in other notable scientific repositories. The hierarchical task analysis framework is qualitative and not yet empirically tested, thus potentially limiting applicability beyond conceptual synthesis. Thus, future scholarly endeavors should address these limitations via cross-database comparisons, expanded inclusion criteria, and empirical validation processes via expert evaluation, simulation testing, MCDA, Bayesian network approaches, and mixed-method studies to improve the applicability and reliability of the framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J. and M.S.; data curation, A.J. and D.S.; funding acquisition, R.O.; methodology, M.S. and D.S.; project administration, A.J.; resources, R.O.; supervision, A.J. and R.O.; validation, A.J. and R.O.; writing—original draft, M.S.; writing—review and editing, A.J., M.S. and R.O.; software, A.J., M.S. and R.O.; visualization, A.J., M.S., R.O. and D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research endeavor received financial support from the University of Rijeka under the project line ZIP UNIRI, specifically allocated to the following projects: (1) “The Influence of ‘Green’ Maritime Policy on the Development of Seaports and Transport Flows” (UNIRI–ZIP–2103-1-22), (2) “Logistical and economic aspects of the development of regional economies in the coastal area” (UNIRI–ZIP–2103–5–22), and (3) development of an evaluation model of ports of county and local significance (UNIRI-ZIP- 2103-9-22).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Renato Oblak was employed by the Adria Polymers Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MASS | Maritime autonomous surface ship |

| ISI | Institute for Scientific Information (as in ISI Web of Science) |

| WoS | Web of Science |

| RQ | Research question (e.g., RQ1, RQ2, RQ3) |

| SSS | Short-sea shipping |

| HMI | Human–machine interface |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| IMO | International Maritime Organization |

| HTA | Hierarchical task analysis |

| DRL | Deep reinforcement learning |

| APF | Artificial potential field |

| FSM | Finite-state machine |

| VTS | Vessel traffic service |

| CPA | Closest point of approach |

| DCPA | Distance at closest point of Approach |

| TCPA | Time to closest point of approach |

| COLREGs | Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea |

| CADCA | Collision avoidance dynamic critical area |

| QSD | Quaternion ship domain |

| MPAPF | Model predictive artificial potential field |

| MANDS | Maritime autonomous navigation decision-making system |

| S-100 | IHO S-100 communication standard |

| ENC | Electronic navigational chart |

| CPU | Central processing unit |

| MG | Metacentric height (stability) |

| FMEA | Failure modes and effects analysis |

| SCC | Shore control center |

References

- Özkan, E.D.; Sevgili, C. Future Horizons: A Bibliometric Analysis of Autonomous Shipping Technologies. Ships Offshore Struct. 2025, 20, 1407–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, J.; Constapel, M.; Trslic, P.; Dooly, G.; Oeffner, J.; Schneider, V. Ship Anti-Grounding with a Maritime Autonomous Surface Ship and Digital Twin of Port of Hamburg. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2023, Limerick, Ireland, 5–8 June 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder-Hinrichs, J.U. Human and Organizational Factors in the Maritime World—Are We Keeping up to Speed? WMU J Marit Aff. 2010, 9, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heij, C.; Knapp, S. Predictive Power of Inspection Outcomes for Future Shipping Accidents—An Empirical Appraisal with Special Attention for Human Factor Aspects. Marit. Policy Manag. 2018, 45, 604–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel, K. Searching for the Origins of the Myth: 80% Human Error Impact on Maritime Safety. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 216, 107942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamoush, A.S.; Ölçer, A.I. Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships: Architecture for Autonomous Navigation Systems. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO. Autonomous Shipping. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/Pages/Autonomous-shipping.aspx (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- DNV. IMO Maritime Safety Committee (MSC 107). Available online: https://www.dnv.com/news/2023/imo-maritime-safety-committee-msc-107--244383/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Burmeister, H.-C.; Bruhn, W.; Rødseth, Ø.J.; Porathe, T. Autonomous Unmanned Merchant Vessel and Its Contribution towards the E-Navigation Implementation: The MUNIN Perspective. Int. J. E-Navig. Marit. Econ. 2014, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahvenjärvi, S. The Human Element and Autonomous Ships. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2016, 10, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H.; Wijeratne, I.B.; Kontovas, C.; Yang, Z. COLREG and MASS: Analytical Review to Identify Research Trends and Gaps in the Development of Autonomous Collision Avoidance. Ocean Eng. 2024, 302, 117652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Xie, H.; Tao, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z. Human Errors Analysis for Remotely Controlled Ships during Collision Avoidance. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1473367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, E.S.; Merkebu, J.; Varpio, L. Understanding State-of-the-Art Literature Reviews. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 659–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenius, M.; Athanassiou, G.; Sträter, O. Systemic Assessment of the Effect of Mental Stress and Strain on Performance in a Maritime Ship-Handling Simulator. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2010, 43, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porathe, T.; Fjortoft, K.; Bratbergsengen, I.L. Human Factors, Autonomous Ships and Constrained Coastal Navigation. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 929, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porathe, T.; Borup, O.; Jeong, J.S.; Park, J.H.; Camre, D.A.; Brödje, A. Ship Traffic Management Route Exchange: Acceptance in Korea and Sweden, a Cross Cultural Study. In Proceedings of the International Symposium Information on Ships, ISIS 2014, Hamburg, Germany, 4–5 September 2014; pp. 64–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, T.; Veitch, E.A.; Utne, I.B.; Ramos, M.A.; Mosleh, A.; Alsos, O.A.; Wu, B. Analysis of Human Errors in Human-Autonomy Collaboration in Autonomous Ships Operations through Shore Control Experimental Data. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 246, 110080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolbot, V.; Bergström, M.; Rahikainen, M.; Valdez Banda, O.A. Investigation into Safety Acceptance Principles for Autonomous Ships. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 257, 110810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, I.; Aymelek, M. Operational Adaptation of Ports with Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships. Transp. Policy 2024, 145, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]