1. Introduction

Offshore wind energy has experienced significant growth in recent years, driven by increasing installed capacity and technological advancements. By 2023, global offshore wind capacity had reached 68,258 MW, distributed across 319 operational projects and more than 13,096 turbines. This represented a 10.2% increase compared to the previous year, alongside a substantial expansion of projects under construction, which grew by 64% compared to 2022. Within this landscape, floating offshore wind turbines (FOWTs) still account for a small share of the installed capacity, with a total of 234 MW operational in 2023. However, this represents a 91% increase compared to 2022 [

1], boosted by pilot projects such as the 88-MW Hywind Tampen in Norway [

2], the 50-MW Kincardine Offshore Wind Farm in Scotland, and the 25-MW WindFloat Atlantic project in Portugal [

3]. The approximately 110 MW installed throughout 2023 represents just 1.75% of the total new capacity added that year, highlighting the need for further advancements to accelerate the adoption of this technology.

Despite the current relatively low share of FOWTs, the trend toward expanding into deeper waters is evident in the large number of projects in the pipeline. An estimated 240 GW of offshore wind capacity is planned for installation in the coming years, with approximately 37% corresponding to floating systems. By 2029, cumulative installed FOWT capacity could reach 14,186 MW, according to developer-announced timelines [

1]. However, technical and economic challenges still hinder the large-scale commercialization of this technology, particularly due to high capital (CAPEX) and operational (OPEX) expenditures. Currently, the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for floating wind turbines is more than twice that of fixed-bottom structures, reaching approximately 290 USD/MWh compared to 133 USD/MWh [

4]. These factors underscore the need for engineering advancements and cost reductions to make floating offshore wind energy competitive on a large scale.

One innovative approach gaining attention is the use of shared mooring lines. This system connects multiple turbines using a common set of mooring lines, optimizing load distribution and reducing the number of required anchors and lines. The shared configuration not only reduces installation and maintenance costs but also improves overall system efficiency. Additionally, this setup can enhance the redundancy of the system, providing increased reliability in the event of a line failure.

However, the use of shared mooring introduces complexity to the system’s dynamics by creating couplings between turbines, requiring research to develop efficient and safe configurations. Several studies have explored both the design and dynamic behaviour of shared mooring systems for floating offshore wind farms (FOWFs). Goldschmidt and Muskulus [

5] analyzed different array layouts, including linear, triangular, and rectangular configurations, while Connolly and Hall [

6] used a quasi-static model to assess cost savings across varying water depths, finding significant benefits beyond 400 m. Liang et al. [

7] conducted a static analysis for the shared mooring system for a dual-spar configuration, employing the elastic catenary theory for cable structures. Regarding system dynamics, Liang et al. [

8] studied a dual-spar configuration with a shared mooring line, revealing increased horizontal motions and load fluctuations, including sudden tension spikes that could compromise structural integrity, while more recent work has expanded to comparisons of different shared mooring systems and various wind farm layouts by Biroli et al. [

9,

10]. Zhang and Liu [

11] performed coupled dynamic analyses on floating wind farms with shared mooring under complex conditions, considering hydrodynamic and structural coupling. The dynamic responses after the failure of mooring lines were investigated as well. Experimental tests by Lopez-Olocco et al. [

12] validated these numerical analyses. Later, Liang et al. [

13] demonstrated that implementing clump weights reduced oscillations and mitigated high-tension events. Gözcü et al. [

14] examined shared line length effects in spar platforms with vertical lines and buoys, showing that proper adjustments could allow turbines to perform similarly to single-turbine systems. Sauder [

15] conducted a frequency-domain analysis of a square floating wind farm, highlighting the need to carefully assess damping and resonance effects to avoid inaccurate load estimations and potential resonances. Regarding larger farms, Lozon and Hall [

16] investigated the dynamics and potential failures of a wind farm consisting of two rows with five 10 MW Spar-type platforms, using shared lines and anchors. The results showed that the system was not at risk of cascading failures, demonstrating favourable characteristics compared to conventional designs.

Regarding shared anchor, despite the potential benefits, they introduce additional challenges related to the multidirectional and cyclic loads experienced by mooring anchors, as highlighted in studies by Lovera et al. [

17] and Coughlan et al. [

18]. B. D. Diaz et al. [

19] showed that axially symmetric anchors, such as driven piles and suction caissons, can be adapted for multiline moorings, whereas plate-type anchors require intermediate load rings to distribute forces. Pile-driven and dynamically installed anchors offer versatility across different soil conditions, while drag embedded anchors are limited to horizontal loads, restricting their use in taut or shared-anchor setups. Complementing these findings, Stevenson [

20] highlighted that suction buckets, driven and grouted piles, torpedo anchors, as well as newer solutions like Helical Anchors and JAVELIN, can sustain loads in multiple directions, making them suitable for complex shared mooring layouts.

The implementation of shared anchor systems in floating offshore wind farms remains limited. Hywind Tampen, developed by Equinor in Norway, is the world’s first floating wind farm designed to supply electricity to offshore oil and gas facilities. Located in the North Sea, approximately 140 km off the Norwegian coast, it consists of 11 spar platforms with a shared anchor system, where the turbines are interconnected through a common mooring arrangement [

2]. The COREWIND project [

21] explored shared mooring and anchor concepts for FOWFs at two sites. Shared mooring lines demonstrated significant cost reductions, while shared anchors lowered anchor costs but, in some configurations, increased overall expenses or tensions on mooring lines.

There have been a few reviews on the shared mooring/anchor systems for offshore renewable energy systems [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Xu et al. [

22] reviewed the shared mooring wind farm layout and optimization method, focusing on the dynamic analysis method and the bearing characteristics of shared anchors. Jiang [

23] focused on the design of mooring systems for floating wind turbines, addressing key aspects such as floater-mooring interactions, material and component selection, design methods and guidelines. Saincher et al. [

24] presents a comprehensive review of shared moorings/anchors within the floating offshore renewable energy (FORE) sector, including the floating wind, solar and wave energy sectors. While the review of Paduano [

25] put emphasis on anchor-soil interactions and nonlinearity in mooring system design.

The ESOMOOR project aims to significantly advance the mooring technologies for large-scale FOWFs, substantially lower the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) of FOWTs while optimizing energy conversion efficiency [

26] by considering innovative shared mooring design with synthetic ropes. To support the identification of suitable floaters, mooring configurations and materials, this paper reviews key design aspects relevant to shared-mooring concepts. It summarizes relevant shared-mooring concepts and applications, outlining major design parameters such as platform type, mooring layout and materials, loading conditions and modelling tools. Finally, a cost analysis highlights strategies for reducing mooring-system capital costs and identifies the key cost drivers in shared-mooring configurations.

2. Fundamental Design Aspects of Shared Mooring Systems

The design of FOWT systems involves several critical components that must work together seamlessly to ensure efficient energy production and operational stability. Key elements such as the floaters, station-keeping systems, and power cables play vital roles in the overall performance of these systems in harsh offshore environments. The floaters provide the buoyancy and stability required for the turbines, while the station-keeping systems maintain their position in the water, counteracting forces from waves, wind, and currents. Power cables are essential for transmitting electricity from the turbines to the grid. Designing these components involves addressing challenges related to material selection, structural integrity, dynamic behaviour, and cost efficiency. This section addresses the fundamental design considerations for offshore wind farms employing shared mooring systems, with particular attention to the characteristics of the mooring lines and the environmental loads acting on them.

2.1. Mooring Line Configurations

Mooring lines are generally classified into two main categories: individual anchor lines and shared lines. Anchor lines are conventional mooring arrangements wherein each floating platform is independently secured to the seabed via dedicated mooring lines and anchors. Shared lines, on the other hand, are distributed between multiple platforms, reducing the total number of seabed connections by enabling inter-platform load distribution.

Anchor lines can be classified into three main types based on their geometric profiles and mechanical behaviour: catenary, taut-leg, and semi-taut configurations. In catenary mooring, the stability of the floater is ensured by the weight of the lower section of the mooring chain that rests on the seabed. This configuration allows for flexibility but requires sufficient seabed space. In contrast, taut mooring systems rely on high-tension cables to maintain stability, reducing horizontal excursions and minimizing the footprint on the seafloor. The semi-taut mooring system is a hybrid configuration that combines features of both catenary and taut systems. It uses partially tensioned lines that reduce seabed contact while maintaining flexibility, offering a balance between the high restoring forces of taut moorings and the compliance of catenary moorings. This system is particularly suitable for deeper waters where moderate line tension and controlled seabed contact are required.

Shared mooring lines between platforms are used to optimize space and reduce costs by allowing multiple units to share a common mooring system. This approach can improve stability and performance by distributing mooring forces.

Table 1 presents different configurations of shared mooring lines. In the investigation [

13,

16], the clump weights were applied for the shared line. Results showed that the application of the clump weights reduced the mooring tension on the shared line and the surge and sway natural periods.

2.2. Mooring Line Materials

Mooring lines for offshore applications are typically made from three main materials: chain, wire rope, and synthetic fibre, each offering distinct mechanical properties and performance characteristics suitable for different environments and operational needs.

Chain is the most commonly used material due to its durability and ability to provide effective weight-based restoring forces. Diameters typically range from 25 to 180 mm, and the most common grades for offshore use include R3, K3, R3S, R4, and R5 [

21]. Chains are commonly employed in several parts of a mooring system. In catenary configurations, they are used along the seabed section, where their weight helps prevent excessive vertical loading on drag embedment anchors while also providing abrasion resistance. Within the water column, chains can be selected for their favourable bending characteristics, though their substantial weight restrict their applicability in this region. Closer to the water surface, particularly in dynamic zones, chains again offer advantageous bending properties and additionally enable practical adjustments to the overall mooring line length.

Wire ropes are a lighter alternative while maintaining similar breaking loads and offering greater elasticity. However, they are more susceptible to damage and corrosion. For offshore use, they are typically made from steel and often incorporate an Independent Wire Rope Core (IWRC) design to enhance strength and durability. To further protect against corrosion in harsh marine environments, these ropes are usually coated with High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) or polyurethane [

21]. Despite their lighter weight and flexibility, they require careful handling and maintenance to prevent degradation over time.

Synthetic fibre ropes are becoming increasingly popular for offshore mooring systems due to their low weight and high elasticity [

28,

29]. The most widely used fibre is polyester [

30], although nylon [

31] and High-Modulus Polyethylene (HMPE) [

32] are also common in specialized applications [

21]. This type of rope is particularly advantageous in deep-water environments where reduced weight minimizes vertical loads. Moreover, their elastic compliance makes them an efficient option for shared mooring arrangements, where the redistribution of loads among interconnected units is critical for system performance. However, the deployment of synthetic ropes introduces increased operational complexity. Rigorous handling procedures and continuous monitoring are required to preserve structural integrity and ensure long-term durability.

Although these fibre ropes provide high breaking strength relative to their weight, offering cost-effectiveness [

33], they exhibit a nonlinear load–elongation behaviour, making constant axial stiffness a simplification. Plastic deformation may occur under both planned and unplanned loading (e.g., during installation), highlighting the need for models that account for permanent elongation. In dynamic conditions, stiffness increases significantly compared to the static case, emphasizing the importance of robust axial stiffness modelling [

34]. Accurate modelling of synthetic ropes is critical to effectively simulate their non-linear material behaviour in their mooring applications [

35]. Numerous empirical models have been developed to accurately capture the non-linear, time-dependent behaviours for synthetic mooring lines [

29,

31,

32,

34,

35].

The effects of dynamic axial stiffness on mooring dynamics have also been widely studied for floating offshore wind turbines [

36,

37,

38] and for wave energy converters [

39,

40]. The procedures for adapting laboratory test stiffness results to the Syrope and a bi-linear model were described by Sørum et al. [

36]. The Syrope model accounts for the quasi-static and permanent rope elongation, while performing the analyses with dynamic stiffness. The bi-linear model applies both the quasi-static and dynamic stiffness in the dynamic analyses. Vidal et al. [

40] showed that using four different stiffness models for polyester ropes led to significant variations in mooring tensions and structure responses. All these studies emphasized the importance of including dynamic stiffness effects in coupled analyses of mooring lines. On the other hand, although synthetic ropes are increasingly used in the moorings of floating structures, their fatigue performance remains a concern. Several offshore standards provide parameters for assessing polyester fibre rope fatigue damage [

39,

40]. There have been some investigations on the fatigue life of moorings [

41,

42], however few have focused on synthetic mooring lines, particularly with consideration of their dynamic stiffness in the numerical simulations.

In conclusion, each material presents unique advantages and limitations, and the choice depends on factors such as water depth, environmental conditions, performance requirements and cost considerations. To ensure consistency across the reference designs, a common set of assumed mooring line material properties is defined in [

43].

2.3. Environmental Loads for Shared Mooring Configuration

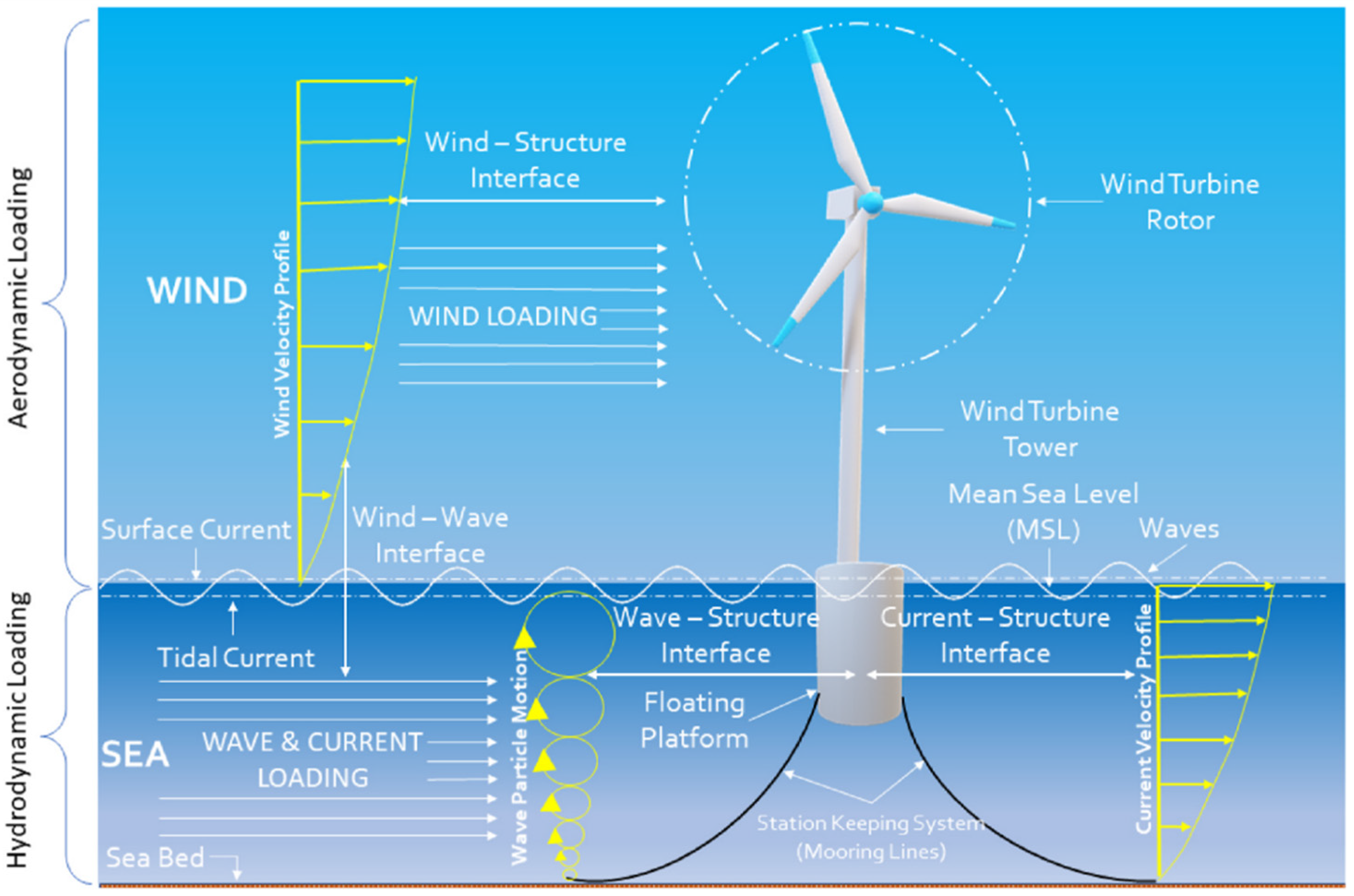

Floating offshore wind turbines are subjected to various environmental loads that affect their performance and structural integrity. As shown in

Figure 1, these loads can be categorized into aerodynamic and hydrodynamic forces.

Aerodynamic Loads: These result from wind interaction, including horizontal and vertical forces acting on the blades and tower. Atmospheric turbulence and variations in wind speed also contribute to load fluctuations;

Hydrodynamic Loads: These arise from waves and ocean currents acting on the floating structure. Such forces influence platform stability and motion, directly affecting the turbine’s performance.

Although numerical simulation software, such as FAST (Fatigue, Aerodynamics, Structures, and Turbulence), typically considers the combined effects of wind, waves, and currents, other environmental factors like tides, earthquakes, ice, soil conditions, temperature and fouling may be critical in specific cases [

45]. Considering these factors in the analysis is essential to ensure the resilience and longevity of FOWTs and mooring systems [

46,

47,

48,

49].

In floating offshore wind farms adopting shared mooring line configurations, the mechanical coupling introduced between adjacent platforms gives rise to additional dynamic interactions beyond the classical aerodynamic, hydrodynamic and current loads. For example, shared-mooring layouts can cause surge, sway and yaw motions of one unit to influence the motion response of neighbouring units, altering their relative displacements and thus their exposure to waves and currents [

50].

Moreover, the coupling between turbines introduces complex aerodynamic interactions that go beyond classical wake effects, such as induced vortices and turbulence. As highlighted by van den Berg et al. [

51], the application of dynamic induction control to floating turbines generates time-varying thrust forces that not only disturb the wake but also induce motions of the floating platform. These motions are strongly frequency dependent, and at certain excitation frequencies they can reduce the effective thrust variation, limiting the intended wake mixing. Consequently, the downstream inflow is modulated by both the aerodynamic wake and the platform dynamics, which can alter turbine-to-turbine interactions and the resulting aerodynamic loads. Therefore, in shared mooring layouts, wake effects cannot be decoupled from platform responses.

Hydrodynamic coupling is similarly affected: the time phasing of wave kinematics and current velocities arriving at each floater connected by shared lines may differ, and the resulting relative motion can modulate drag and lift forces on submerged structures. These coupled effects can lead to amplified mooring line fatigue through multi-point loading and altered anchor loading patterns. In particular, non-uniform currents interacting with moving platforms induce asymmetric forces along mooring lines and dynamic power cables, increasing cyclic stresses and influencing the overall stability of the floating array.

In summary, these coupled aero-hydro-structural-mooring effects highlight the necessity of specially tailored dynamic analyses for floating offshore wind farms with shared moorings, rather than treating each unit in isolation under standard environmental loading assumptions.

3. Concepts and Applications of Shared Mooring Systems in FOWFs

The use of shared mooring systems in floating offshore wind turbines is an emerging approach aimed at reducing costs and simplifying offshore installations. By allowing multiple turbines to share mooring lines, this strategy can decrease material consumption, streamline deployment, and minimize the seabed footprint. However, despite these potential benefits, shared mooring systems present significant technical challenges. The dynamic interaction between turbines, the complexity of ensuring stability and durability, and the need for advanced models to predict hydrodynamic and structural behaviour are key issues to address.

As a relatively new concept, ongoing research focuses on evaluating the feasibility of shared mooring systems under different environmental conditions.

Table 2 presents a comparative summary of the characteristics of the studied systems, providing an overview of current projects and research efforts in this field. The shared mooring or shared anchor layouts, materials of the mooring lines, floater space, environment, water depth and sites are summarized.

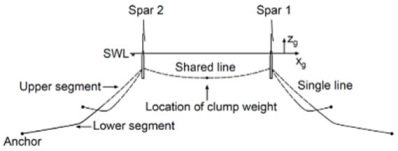

The study of Liang et al. [

8] investigated the dynamic behaviour of a shared mooring system for two OC3 Hywind Spar-type 5 MW floating offshore wind turbines in a water depth of 320 m. The turbines were spaced 1000 m apart (approximately 8 times the floater diameter). The mooring system consists of anchor lines made of chain and wire, while the shared line is composed of wire. Various configurations of the shared line are analyzed. The hydrodynamic coupling between two FOWTs was ignored because of the large turbine spacing. Results indicated that, compared to a single-spar mooring system, the shared mooring layout experienced higher horizontal motions and increased mooring line tensions. Additionally, significant snap loads are observed in the shared line, highlighting the challenges associated with load distribution and dynamic response in such configurations.

Lopez-Olocco et al. [

12] conducted the model scale tests using the concepts in [

8], and compared the dynamic behaviour of a dual-spar floating wind farm with shared mooring to a single floating wind turbine under wave conditions. A water depth of 235 m at a Norwegian offshore site was considered. The turbines were spaced 750 m apart (approximately 6 times the floater diameter). The mooring system featured shared lines composed of chain and wire, while anchor lines were made of wire. Results showed that the shared mooring system led to increased horizontal motion and higher mooring line tensions compared to a single-spar configuration, with significant snap loads observed in the shared lines. Additionally, the surge natural period was 51% longer, while surge displacement was limited to 10% of the water depth, and pitch motion was restricted to a maximum angle of 10 degrees. These findings highlight the challenges and dynamic responses associated with shared mooring layouts in floating wind farms.

To address the high snap loads occurring on the shared line, Liang et al. [

13] experimentally investigated the same concept in [

12] by applying a clumped weight on the shared line. Findings revealed that the use of the clumped weight led to a reduction in the surge and sway natural periods. Additionally, extreme mooring tension on the shared line was reduced by up to 30%, demonstrating the effectiveness of the approach in alleviating dynamic loads. However, the extreme mooring tension on the anchor line increased, indicating a shift in load distribution within the mooring system.

The COREWIND project [

14] investigated a shared mooring configurations for a floating offshore wind farm at the Gran Canaria site, located in 200 m water depth with a catenary mooring system. The study focused on a 15 MW turbine with a turbine spacing of five times the rotor diameter. Two designs were analyzed: Design 1, with a shared line length of 1093.8 m, and Design 2, with a length of 1150.7 m. Results showed that Design 1 experienced 75% higher mooring forces compared to a single turbine, while Design 2 achieved a 23% reduction in mooring line forces, demonstrating the influence of shared line length on load distribution. The second configuration explored in the COREWIND project was a shared anchor mooring configuration for a floating offshore wind farm at Morro Bay, situated in 870 m water depth with a taut mooring system. The study considered a turbine spacing of seven times the rotor diameter, utilizing a combination of polyester and chain mooring lines. Findings indicated that the natural frequency of the shared system could be adjusted to match that of a single turbine by varying line 9, optimizing the system’s dynamic response. In addition, Design 3 resulted in a 30% increase in tension on the upstream mooring line, highlighting the impact of load redistribution in shared anchor configurations.

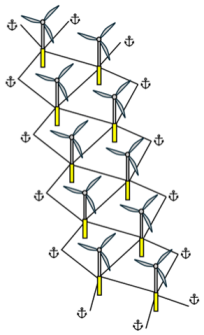

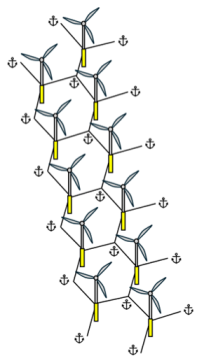

Goldschmidt and Muskulus [

5] investigated the feasibility and advantages of different turbine arrangements, namely the row, rectangular, and triangular, for semi-submersible FOWTs in a 200 m deep North Sea location with a turbine spacing of 640 m. Their study assessed the cost-saving potential and dynamic behaviour of shared anchoring and mooring configurations. Results indicated that these configurations could lead to substantial cost reductions, with mooring system costs decreasing by up to 60% and total system costs by approximately 8%. However, they also highlighted that coupled mooring systems could result in increased turbine displacements, potentially affecting power cable connections and necessitating careful design considerations to maintain system stability and performance.

Lozon and Hall [

16] from NREL conducted a technical study on a 10-turbine shared mooring floating offshore wind farm, evaluating the feasibility of shared mooring systems for deep-water floating wind farms. The study focused on Spar-type floaters with a 10 MW capacity each, deployed along the U.S. Pacific coast in 600 m deep waters. Turbines were spaced 1600 m (nine rotor diameters apart). The mooring system featured a taut mooring configuration, using polyester lines for both shared and anchor lines, secured with suction piles. To mitigate dynamic loads, clump weights were placed on the shared lines. The study found that shared moorings led to higher tension on both the mooring lines and shared anchors, requiring careful design considerations. The results suggested that the shared mooring system was equally suitable for SPAR and semisubmersible platforms, specifically mentioning compatibility with the SWE Triple Spar Platform.

The Hywind Tampen project [

2], developed by Equinor off the coast of Norway, represented a significant milestone in the advancement of floating offshore wind technology. With the water depths ranging from 260 to 300 metres, the project employed a shared anchor system for its 11 turbines, each with an 8 MW capacity. The shared anchor system features a spar platform made of concrete and an innovative anchor design to ensure the stability of the turbines in deep waters. By employing a spar platform made of concrete, 120-ton suction anchors, and a catenary mooring configuration, the project reduced installation costs, simplified mooring arrangements, and optimized space. The shared anchor line system provides the necessary tension to maintain the stability of the turbines in challenging marine environments.

Besides these solutions, honeymooring has recently emerged as an innovative shared-mooring concept for floating offshore wind farms, aiming to improve load distribution, reduce individual line tension, and enhance stability in densely packed turbine arrays. Sandal and Norman [

52] presented the honeymooring as a grid-based solution for sustainable planning of floating wind parks, highlighting benefits such as reduced seabed footprint, simplified installation, optimized cable management, and the possibility of fishing activities within the wind farm. Cluster layouts were shown to be particularly promising, and two reference designs were introduced. Hanssen et al. [

53] evaluated the system at both single-turbine and 20-turbine farm scales, demonstrating significant reductions in peak mooring loads and fatigue on floaters. In terms of economic advantages, studies have shown that honeymooring can reduce capital and operational expenditures by requiring fewer anchors, lighter mooring lines, and lower pretension levels, while allowing simple disconnection and reconnection of individual turbines for maintenance [

53,

54]. Hardware costs are also substantially reduced, with estimates of up to 50% savings and approximately 10% reduction in CAPEX, corresponding to €300,000 per MW in mooring cost reductions [

55]. Additional benefits include mitigation of dynamic loads via buoy-assisted mooring, simplification of turbine–mooring interfaces, potential integration of mooring and power cables, and pre-installation testing of mooring components to reduce schedule risks [

52]. Collectively, these findings suggest that honeymooring offers a viable and efficient alternative to traditional mooring systems.

4. Modelling Methods and Simplifications

The modelling of floating offshore wind turbines involves a wide range of coupled aero-hydro-servo-elastic phenomena. These include the interaction between the rotor–nacelle assembly and the floating substructure, as well as, in multi-unit configurations, the dynamic coupling among turbines connected through a shared mooring network [

22]. Numerical tools play a crucial role in analyzing these mechanisms, and the literature offers a variety of modelling approaches, from simplified low-fidelity schemes in frequency domain, mid-fidelity tools, to fully coupled high-fidelity simulations for FOWTs.

Table 3 summarizes the fidelity levels of some commonly employed methods.

Low-fidelity models are mainly used in the earliest design stages, when fast evaluations of system behaviour, parameter sensitivity, and feasibility are required. They often rely on linearized or quasi-static representations of the mooring system, in which the line is assumed to instantaneously reach a new equilibrium as the floater moves. Quasi-static approaches employ catenary equations to update line geometry, capturing geometric nonlinearity while neglecting inertia and damping. This method, commonly implemented in tools such as MoorPy, is computationally efficient and suitable for early optimization. However, it cannot represent key dynamic effects such as damping, inertia forces, or snap loads, and its applicability is limited in energetic seas or highly nonlinear conditions [

56,

57]. To bridge this gap, quasi-dynamic formulations introduce drag and inertia forces in an approximate manner, often through reduced-order or Morison models, offering improved physical realism with modest computational cost [

57].

As the design advances, mid-fidelity engineering tools become the preferred option. Software such as OpenFAST, HAWC2, SIMA, Bladed, SIMPACK, Orcaflex, and Flexcom enables time-domain simulations of the fully coupled aero-hydro-servo-elastic response of FOWTs, capturing nonlinear interactions with reasonable computational efficiency [

22,

56,

58]. These tools combine aerodynamic solvers, structural models, hydrodynamic modules based on potential-flow or Morison-type formulations, and mooring solvers. They typically require hydrodynamic coefficients precomputed from frequency-domain radiation–diffraction analyses [

56]. Mid-fidelity tools are widely used for operational and extreme-load simulations, fatigue assessment, and evaluation of turbine–platform interaction effects.

Methods based on potential flow and BEM often fail to capture nonlinear interactions among these forces. This has driven the adoption of high-fidelity CFD and FEM frameworks, which can resolve the coupled aero-hydro-structural physics with more accuracy [

59]. These tools usually refer to CFD and structural FEM codes including OpenFOAM, STAR-CCM+, ANSYS, and Abaqus, which can represent strongly nonlinear and fully dynamic behaviour with high spatial and temporal resolution [

56,

60]. However, their computational cost is high, particularly for multi-floater or large farm simulations, which limits their use to final design verification, failure-mode analyses, or calibrating lower-fidelity models. When it comes to the shared mooring system, the modelling is more complex and time consuming.

Studies focusing specifically on shared mooring configurations adopt modelling approaches that differ substantially in scope and fidelity. Reference [

5] models the dynamic behaviour of shared-moored floaters using rigid-body equations of motion. In the frequency domain, the mooring system is represented by a linearized stiffness matrix. In the time domain, a quasi-static catenary mooring model is coupled to the hydrodynamic solver. First-order wave loads are evaluated using the Morison equation, while diffraction effects are approximated with the McCamy–Fuchs method. Second-order mean and slow-drift forces are computed using Newman’s approximation, with transfer functions derived from fixed-cylinder data. Pan et al. [

61] developed a simplified floating wind-farm framework composed of a low-order rigid-body module, a quasi-static mooring module and a Gaussian wake module, with all array-level simulations executed in Simulink to capture interactions between upstream and downstream turbines connected through shared arrangements.

Arramounet et al. [

62] employed OrcaFlex, combined with HAWC2, to investigate the economic implications of shared mooring and shared anchor systems through time-domain simulations, focusing on resulting cost structures and load trends. Reference [

8,

9] also adopted a consistent software environment, using SIMA, modelling spar floaters as six-DOF rigid bodies in SIMO and representing shared mooring lines as nonlinear slender elements in RIFLEX, thereby resolving fully coupled turbine–mooring dynamics. Hydrodynamic properties of the floater are computed in the frequency domain using WADAM, providing added mass, radiation damping, first-order wave forces, and second-order mean drift forces. Reference [

14] used HAWC2 as in part of [

62] but modelled shared-mooring configurations through a multibody Timoshenko-beam formulation, Morison or WAMIT-based hydrodynamic loading. Aerodynamic loads were computed using blade-element momentum theory, the turbine controller was implemented through an external dynamic link library (DLL), and mooring-line dynamics were calculated in a separate DTU-developed DLL.

Zhong et al. [

63] constructed a shared-mooring-ready hydrodynamic and structural model by generating platform meshes in ANSYS, computing first- and second-order wave loads, added mass, damping and stiffness in OrcaWave, and importing these outputs into OrcaFlex to obtain a modified semi-submersible representation. Hall et al. [

64] proposed a methodology beginning with a linearized analysis of array layout options, followed by quasi-static optimization of each mooring line using MoorPy, and finalized through fully coupled time-domain simulations of the entire shared-mooring array in OpenFAST. Hall et al. [

65] also expanded the RAFT frequency-domain model based on FAST tool, to simulate full arrays by assembling system matrices at the array level, applying phase-consistent wave excitation to each platform, and using MoorPy to linearize the mooring stiffness. This approach enables the prediction of tensions in shared mooring lines and was validated through comparisons with FAST.Farm. Coupled dynamic analysis of the shared mooring system was conducted by [

16] using FAST.Farm, an extension to OpenFAST which was used for aero-hydro-servo-elastic dynamics of each floating wind turbine. Two new capabilities were included in FAST.Farm to properly simulate shared-mooring arrays: the dynamic coupling between wind turbines from shared mooring lines and the accurate representation of the timing of wave loads across the array.

In summary, as in conventional FOWT systems, low-, mid-, and high-fidelity methods play complementary roles within a multi-fidelity design workflow. Early-stage screening relies on simplified models, engineering-level simulations support load analysis, control development, and operational studies, and high-fidelity solvers provide the level of detail required for final design, certification, and failure assessment. Integrated software ecosystems are essential for coupled simulations and continue to advance toward supporting farm-scale layouts, multi-body interactions, and shared-mooring configurations.

The literature on modelling approaches for FOWTs with shared moorings shows that mid-fidelity tools remain the most commonly used option. In these frameworks, hydrodynamic coefficients are typically derived in the frequency domain and then assigned to each unit within a multi-body system. However, hydrodynamic coupling effects, especially the contribution of nonlinear wave forces to platform motion, are still crucial for ensuring overall stability [

66], and their importance increases when platforms are interconnected through shared moorings. In the aerodynamic domain, accurately representing the unsteady flow around turbine blades, including turbulence, wake evolution, and their impact on efficiency and structural loading, continues to pose significant challenges. Despite progress on both fronts, the combined influence of turbine–turbine interactions and the nonlinear behaviour introduced by shared mooring systems has yet to be fully addressed. Structural deformation of the substructures and the flexible response of turbine blades introduce additional complexity into the wake behaviour of FOWTs [

67]. Therefore, a fully coupled aero-hydro-servo-elastic framework that integrates CFD, FEM, and open-source tools for mooring dynamics is regarded as the most accurate approach, as it can also account for interactions among multiple floaters and turbines.

For addressing computational challenges while maintaining high accuracy, the Reduced Order Models (ROMs) have emerged as a viable solution, which showed the effectiveness in enabling large-scale wind farm simulations, reducing computational costs, and improving real-time operational efficiency [

68,

69]. Machine learning (ML) has also become an increasingly relevant tool in FOWT modelling, with promising benefits for prediction accuracy, operational optimization, and fault identification. However, Masoum [

70] demonstrated the challenges remain in fully integrating ML-driven models into existing simulation frameworks. Future applications of these techniques to FOWTs with shared moorings could be strengthened by coupling them with mooring dynamics tools, while further research should focus on improving predictive accuracy and adaptability through experimental validation.

5. Mooring Costs Estimation

Floating Offshore Wind Farms represent a promising solution for harnessing wind energy in deep waters, where traditional fixed-bottom turbines are not viable. However, their widespread implementation faces significant challenges, primarily related to high capital expenditures, operational expenditures, and complex installation logistics. The mooring system, essential for station-keeping, contributes substantially to these costs, making its optimization crucial for improving economic feasibility. To enhance competitiveness and accelerate large-scale deployment, minimizing costs through innovative design strategies, shared anchoring solutions, and advanced procurement models has become a key focus of research and industry efforts.

Beiter et al. [

71] and DTOcean+ [

72] developed studies focused on the cost analysis of offshore wind energy components, providing important frameworks for economic assessment. While Beiter et al. [

71] proposed a model tailored to the United States context, DTOcean+ concentrated on European conditions. These work established methodological approaches to estimate procurement and system costs, forming the basis for evaluating the economic potential of offshore wind energy. Their models have since been adopted and adapted in subsequent research, serving as reference tools for comparative cost assessments and techno-economic evaluations in different geographic and technological contexts.

In general, the cost estimation of mooring components is derived from the quantity of material required and the minimum breaking load of the material. Among these components, chains and lines typically represent the largest share of the overall mooring cost, accounting for approximately 50–70% of the total [

73]. For most conventional materials, empirical relationships between these parameters and cost are well established in the literature. However, nylon has only recently emerged as an alternative for mooring lines, and corresponding cost relationships are not yet widely available.

Building on the procurement cost model in [

50], Pan and Cheng [

74] conducted a parametric study on bridles for a 15 MW spar-type floating offshore wind turbine in catenary configuration using chain lines at a moderate water depth site. The study identifies that chain diameter, grade, and line length are critical parameters influencing mooring costs. A set of over 100 cost-effective bridle configurations was produced and their relationships between bridle length and diameter are shown in

Figure 2.

Expanding on this approach, Pan et al. [

75] developed a comprehensive design methodology for shared mooring line configurations at a moderate water depth site, demonstrating that shared lines can significantly reduce procurement costs. The methodology generated many different conventional configurations for single turbine and shared mooring configurations for two- and three-turbine arrays. Chain mooring lines were once again considered in the analysis. The cost distribution based on the generated models is presented in

Figure 3. For shared mooring designs, the cost distribution is skewed toward lower costs and with higher probabilities of occurrence compared to conventional moorings, with the cost-saving benefits increasing as the number of shared lines rises.

Using the cost estimation model from DTOcean+ [

73], Chemineau et al. [

76] investigated the cost implications of different mooring strategies for floating offshore wind turbines, focusing on single-turbine, shared-anchor, and shared-line configurations applied to semi-submersible platforms at sites of moderate and deep water depth. Their analysis highlighted that the shared-anchor layout delivered only limited economic benefits, since reductions in anchor costs were counterbalanced by the increased length and expense of the mooring lines required. In contrast, the shared-line configuration demonstrated clear potential for significant cost savings, primarily because the horizontal inter-platform connections enhanced yaw stiffness and eliminated the need for supplementary buoys, which had been necessary in the conventional design. Beyond the financial advantages, the study also emphasized practical considerations: while shared-line systems can substantially lower procurement costs, they introduce operational challenges associated with surface cables, particularly regarding navigability and long-term maintenance. This dual perspective underscores the need to balance economic optimization with operational feasibility in the design of shared mooring systems. The applied correlations for chain, polyester lines, and drag-embedded anchors were defined as follows:

where

is the minimum breaking load (in kN),

is the mooring length (in m),

is the mass of the anchor (in kg),

is the material cost of the anchor (in €/kg), and

CF is a complexity factor that varies depending on the type of anchor employed.

Housner and Hernando [

77] conducted a comprehensive assessment of the economic implications of adopting shared-anchor systems for floating offshore wind farms at deep-water conditions. Using open-source tools to account for installation logistics, operations and maintenance, and energy production, the study compared pilot-scale and gigawatt-scale projects based on a semi-submersible platform with polyester taut moorings and suction pile anchors. Among the cost evaluations reviewed, installation expenses, vessel requirements and their spatial constraints, installation and transit time, as well as operational and maintenance costs were considered. These encompassed repair and replacement expenses, annual failure rates for different mooring lines and anchors, and the costs associated with moorings, anchors, power cables, turbines, substations, substructures, and other components. Additionally, an estimate of the Annual Energy Production (AEP) was obtained to calculate the LCOE. Results indicated that shared anchors can reduce LCOE at smaller scales, largely through lower operational costs, but these benefits diminish at larger scales due to higher anchor failure rates and associated maintenance expenses.

Weller et al. [

78] developed a multi-objective optimization framework for the design of mooring systems for a 15 MW semi-submersible floating offshore wind turbine, considering platform horizontal excursion, characteristic line tension, and mooring system CAPEX with equal weighting. The analysis evaluated moderate- and deep-water conditions, employing cost factors derived from publicly available data and internal databases for chains, polyester ropes, and connectors. Different mooring configurations, including chain catenary, semi-taut with chain and polyester, and taut with only polyester, were assessed, revealing that taut systems exhibit lower component costs due to reduced line lengths, although installation costs were not considered. Semi-taut configurations occasionally require larger chain sizes to limit platform motions, resulting in CAPEX values comparable to chain catenary systems. The study further indicated that increasing the number of mooring lines can enable the use of smaller-diameter lines, thereby reducing the overall CAPEX of the mooring system.

6. Summary and Conclusions

This study summarizes key findings on shared mooring configurations for FOWTs, and strategies for improving performance and reliability. A review of existing shared mooring and anchor concepts for FOWTs shows that mooring systems are generally classified into catenary, taut-leg, or semi-taut configurations, all of which are suitable for water depths between 200 and 850 metres, typical of most current designs. The most commonly used mooring materials for FOWTs with shared moorings and anchors are chain and polyester. Chain provides high durability and weight, contributing to platform stability, while polyester offers flexibility and a high strength-to-weight ratio, making it particularly suitable for deeper waters.

The selection of mooring materials depends on site-specific conditions and project requirements. One key challenge in shared mooring lines is the occurrence of snap loads. To mitigate excessive tensions and prevent potential failures, clump weights and stiffer mooring lines can be strategically implemented. Adding weights at specific points along the mooring line helps reduce dynamic tension fluctuations, while increasing line stiffness improves energy absorption and limits excessive platform motions under extreme conditions. Shared mooring lines present opportunities and challenges, requiring careful analysis of excitation modes and redundancy mechanisms to ensure operational stability. By incorporating clump weights, stiffer lines, and site-specific sea state analysis, developers can optimize mooring performance and minimize risks associated with extreme conditions.

In the modelling method, mid-fidelity tools such as OrcaFlex and SIMA remain widely used for platform and shared mooring dynamics, providing a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. However, accurately capturing hydrodynamic coupling effects and the complex aerodynamic interaction among multiple turbines remains challenging, making it difficult to fully assess and ensure overall system stability. High-fidelity coupled CFD-FEM frameworks allow for detailed aero-hydro-servo-elastic simulations, capturing nonlinear interactions between turbines, shared mooring systems, and platform motions. Combining these modelling approaches with mooring dynamics tools can enhance predictive accuracy, optimize shared mooring performance, and support the development of more reliable and economically feasible floating wind farms. Reduced Order Models (ROMs) have emerged as effective tools for enabling large-scale wind farm simulations while reducing computational costs and supporting real-time operational decisions. Machine learning (ML) techniques offer further opportunities for predictive accuracy, operational optimization, and fault detection, although integrating ML-driven models into existing simulation frameworks remains a challenge.

On the other hand, the cost analysis highlights several strategies for reducing the capital cost of mooring systems. In some cases, increasing the number of mooring lines can lower overall CAPEX, particularly when taut configurations are adopted. Taut moorings generally reduce expenditures because they require shorter line lengths, making them attractive for projects where material optimization is a priority. Nonetheless, their installation is often more complex and demands specialized procedures and equipment, which must be considered in the cost assessment. Load direction is another critical factor influencing cost. Upwind lines typically carry higher tensions than downwind ones, allowing for differentiated specifications. Using lines with lower minimum breaking loads and smaller diameters in downwind positions, while maintaining stronger lines upwind, can reduce costs without compromising safety or stability.

With respect to anchor strategies, the advantages of shared anchors are less clear. Although they reduce the number of anchor units, they may require additional mooring lines and introduce higher risks of failure, potentially increasing both capital and operational costs. In contrast, shared mooring lines show greater promise: by reducing the number of components such as buoys, weights, and anchors, they can significantly decrease installation and maintenance expenses while maintaining structural integrity.

Overall, cost optimization in floating offshore wind mooring systems can be achieved through careful consideration of taut configurations, directional load effects, and shared line arrangements. However, shared anchors do not consistently yield financial benefits and should be evaluated cautiously within the broader mooring strategy.