Abstract

As the global environment continues to deteriorate, water blooms and red tides occur more frequently, making it increasingly important to control eutrophication in water bodies. This study focuses on optimizing an adjustable vortex well alga extractor for deep-well alga removal to reduce the risks associated with algal blooms and red tides. Numerical simulation was employed to model the working process of the vortex well alga extractor and to determine its most efficient structural parameters. The optimal dimensions of the adjustable vortex well alga collector optimized by the PSO-GP model are as follows: during the experiment, the water depth at the suction inlet is 200 mm, the diameter of the suction inlet is 480 mm, the distance of the fence is 2000 mm, and the average flow velocity of the water area is 0.12 m/s. Under these conditions, the working flow rate of the pressurizer can reach up to 18,400 cubic meters per hour at a maximum. Under these conditions, the collection efficiency for blue-green algae can reach 92%. The proposed optimization method can assist project managers in improving the design and operation of deep-well alga removal systems, achieving higher accuracy and efficiency, conserving energy, and enhancing overall alga removal performance.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Status of Algal Bloom Control Technologies

In recent years, there has been a rapid development of efficient removal technologies for algal blooms and their derivatives, with research focusing on improving treatment efficiency, reducing the risk of by-products, and achieving environmental friendliness. Photocatalytic technology has attracted much attention due to its green characteristics, and photocatalytic technology has become a research hotspot because of its environmental friendliness and efficient degradation ability. Yu, P. et al. [1] constructed a ternary Z-type photocatalyst (Ag/AgCl/ZIF-8/SCN) to achieve nearly 100% removal of chlorophyll a within 300 min, and revealed the mechanism by which excess superoxide radicals (O2−) inactivate algal cells through oxidative stress. Similarly, Li, X. et al. [2] developed a Ag3PO4/ZnWO4 modified graphite felt electrode, which achieved a photocatalytic–electrochemical removal rate of 99.21% and 91.57%, respectively, and the efficiency remained stable after recycling. Both studies emphasized the leading role of free radicals, but photocatalytic technology generally has the problems of difficult catalyst recovery and a narrow light response range, which limits its engineering application. In chemical oxidation and advanced oxidation processes, chemical oxidants rapidly inactivate algae through free radical attack. Electrochemical methods such as the electroflocculation flotation (ECF) method of Wang, Y. [3] use an aluminum electrode to achieve 100% alga removal at low energy consumption (0.4 kWh/m3), but their efficiency is highly pH-dependent. Although these techniques are fast and efficient, excessive oxidants tend to induce cell lysis [4], and the dosage needs to be precisely controlled. In the physico-mechanical approach, membrane technology demonstrates reliability through physical retention. Zhang, F. [5] used a two-stage ultrafiltration process (polysulfone hollow fiber membrane + aromatic polyamide spiral membrane) to target algal cells and microcystins (MCs), respectively, with the latter achieving a 96.3% removal rate but requiring high-pressure operation (0.3–0.4 MPa). Park, C. [6] further explored the metal mesh membrane, and the removal rate of suspended solids from the monolayer mesh reached 97%, but the pore size selection needed to be adapted to the algal morphology (e.g., the fibrous structure of spirulina). However, membrane fouling remains a core challenge: LeBlond, G. [7] noted that the efficiency of a 10 μm disc filter drops dramatically under aeration conditions, while a 5 μm filter cloth is stable but has limited flux. These studies highlight the advantages of membrane technology for toxin removal, but also call for the development of anti-fouling materials and low-energy processes. Biological methods are needed to explore the resource utilization and environmental remediation functions of algae. Huang W. et al. [8] showed that the rate of zinc adsorption by green algae (90%) was significantly higher than that of nickel (25–46%). However, the stability of biological systems faces challenges: Kipigroch, K. [9] found that the algal–fungal symbiosis system inhibited aerobic granulation, resulting in a 40–50% decrease in nitrogen and phosphorus removal; Mao, Y. [10] increased the removal rate of pollutants from alga ponds by extending the light exposure to 4 h, but the efficiency of excessive light decreased. These studies highlight the duality of biotechnology, which combines the potential of adsorption and resource utilization and the risk of ecological regulation. The combined process breaks through the single limitation through the complementarity of technologies. In addition, Oh, H.S. [11] compared suspended air flotation (SAF) and dissolved air flotation (DAF) technologies to show that SAF is both economical and feasible in the Dieffenbaker Lake irrigation canal, while DAF is more environmentally friendly but more costly. In terms of engineering applications, despite the progress made in laboratory research, practical applications still face multiple obstacles. Wang, X. [12] developed a multiphase flow pump DAF device with a turbidity removal rate of 56.49% at 0.4 MPa dissolved air pressure, but the long-term operation stability needs to be further verified; Fan G. [13] applied ultrasound technology to the Pengxi River in the Three Gorges Reservoir area, and the alga density in the 500 square meter water area was reduced by 80%, proving its engineering potential. However, most technologies (e.g., photocatalysis, omnidirectional ultrasound) have not yet been scaled up, and there is a lack of long-term monitoring of ecological safety (e.g., residual toxicity of inactivated algae).

In summary, the existing studies have significantly improved alga removal efficiency through mechanism innovation and process integration. However, the technical differences are reflected in the processing speed (photocatalysis takes several hours, while ECF only takes minutes), the risk of by-products (ultrasonic treatment releases AOM vs. no chemical addition of membrane technology), and the cost of scale (expensive photocatalysis vs. metal mesh economy). In the future, it will be necessary to strengthen the actual water experience verification, the quantification of the multi-technology collaboration mechanism, and the ecological safety assessment to promote the transformation of laboratory results into engineering applications.

1.2. Deep Well Pressurized Alga Control Technology

The aggregation of cyanobacteria forms red tides and algal blooms. Cyanobacteria are mononuclear organisms. For their growth and reproduction, they utilize the unique structural characteristics and suspension adjustment mechanism of “pseudo vacuoles” to reduce sinking speed, allowing them to float on the surface of the water body, receive light for photosynthesis, and maximize growth opportunities. According to the cyanobacteria pressure breaking test, when the pressure within cyanobacterial cells exceeds the critical value of 0.7 MPa, pseudo-internal cavitation will occur, causing them to burst and lose buoyancy. If the pseudo vacuole inside cyanobacteria can be effectively destroyed, it can prevent them from floating to the surface of water bodies and accumulating; thus, suppressing outbreaks of algal blooms can help solve problems associated with cyanobacteria. The study found that deep well pressurized treatment methods for cyanobacteria have a significant inhibitory effect on slowing down and eliminating algal blooms and red tides. This method can significantly inhibit pollution from heavy metal ions and other pollutants in water while improving environmental quality related to red tides and algal blooms. It also enhances water quality conditions by reducing bacterial numbers, improving marine ecosystem structure and function, thereby promptly enhancing overall water environment quality. Additionally, this treatment reduces nitrate content in water bodies to meet purification requirements.

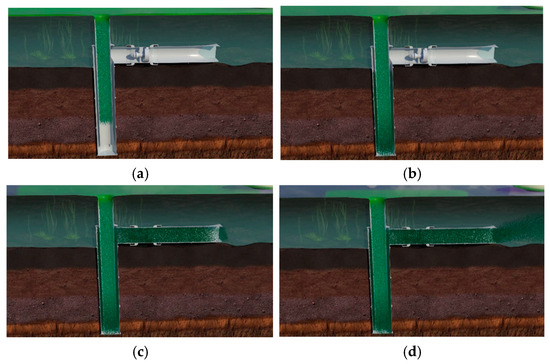

The deep well alga control project mainly includes a high-efficiency adjustable vortex well alga extraction device, negative pressure generator, two-way alga control enclosure, etc., and supporting facilities such as power, communication, and intelligent monitoring. The workflow of the deep well alga control project is shown in Figure 1 below. Under the negative pressure generated by the negative pressure generator, the cyanobacteria are sucked to the bottom of the alga control device (Figure 1a). Under the hydrostatic pressure of 70 m (0.7 MPa), the pseudo cavitation is compressed and loses the ability to float (Figure 1b). The pressurized cyanobacteria are discharged into the lake through the outlet pipe for natural diffusion and purification (Figure 1c,d). At the same time, a channel is added to the outlet pipe of the deep-submersible high-pressure alga control deep well, and a suction pump is connected to transport some of the blue-green algae that have been pressurized by the deep-submersible high-pressure alga control device to the shore alga water separation station for alga water separation. Clear water is then discharged into the lake to reduce cyanobacterial biomass.

Figure 1.

Deep well alga control project workflow. (a) Blue algae sinking. (b) Blue algae being drawn into the intake. (c) Pressurization of blue algae within the system. (d) Discharge of blue algae from the out-let.

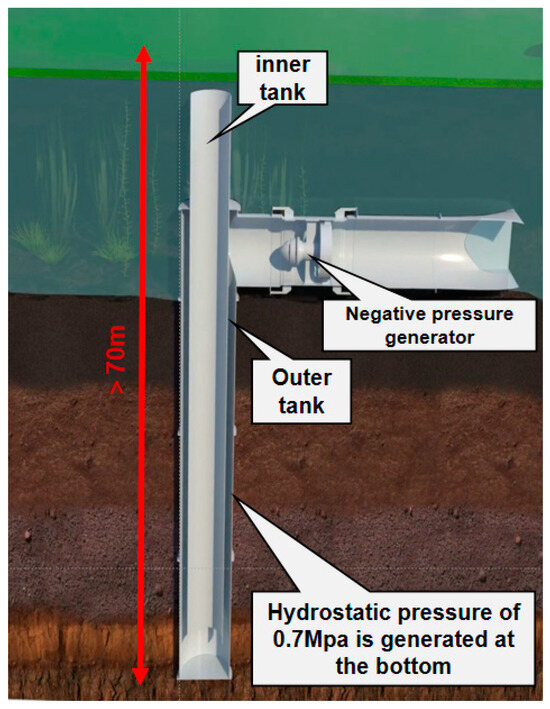

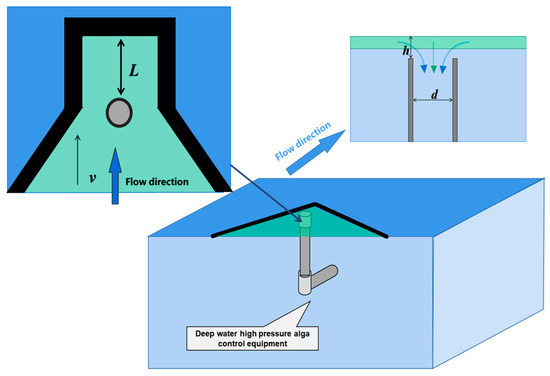

The main body of the adjustable vortex well alga extractor is a double-layer sleeve structure alga suction pipe, including an outer pipe with an open top and an inner pipe with an open bottom. The inner pipe is suspended inside the outer pipe and is sealed and connected to the outer pipe through a sealing device. An adjustment device for adjusting the height of the inner pipe is also provided. The side wall of the alga suction pipeline is provided with an alga outlet for connection to the pump inlet. The diagram of the high-pressure deep well alga control device is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Diagram of the high-pressure deep well alga control device.

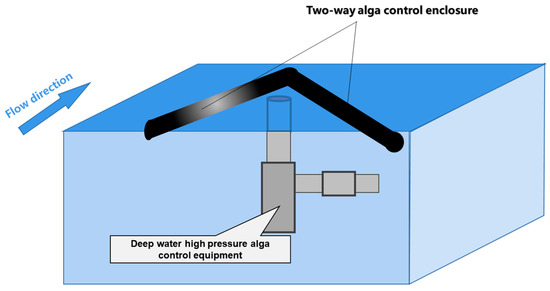

To demonstrate the feasibility of the high-pressure deep well alga control technology path, existing studies have provided strong evidence from both laboratory mechanisms and engineering field levels. At the mechanism level, Ma L. [14] found in an experiment of pressurizing cyanobacterial aggregates that, when the pressure was increased to 0.6 MPa, the removal rate of cyanobacterial biomass could reach 40%, and the removal rate of chlorophyll a could reach 87%, preliminarily verifying the effectiveness of the pressure-breaking technology from the mechanism perspective. Further, at the engineering verification level, Yan Q. [15] conducted a field study on the control of cyanobacteria in aquaculture water by deep well circulation treatment. The results showed that, after deep well pressurized circulation treatment, the concentration of chlorophyll a in the water decreased by 69%, and the total number of cyanobacterial cells decreased by 92%, fully demonstrating the engineering applicability and efficiency of this technology in real environments. The above studies together form a complete evidence chain from principle to practice for this technology, laying a solid theoretical and practical foundation for further optimization research on the structural parameters of the vortex well alga collector in this work. The specific layout is shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3.

The high-pressure deep well alga control device and fence site layout diagram.

1.3. PSO-GP Optimization Algorithm

Benuwa, B.B. [16] employed the Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm for hyperparameter tuning, forming the PSO-GP method. As a global optimization algorithm inspired by social behavior, PSO can identify a superior set of hyperparameters for Gaussian processes, thereby enhancing the predictive performance of the overall model. Hajihassani M. [17] recognized that PSO has been successfully validated in fields such as geotechnical engineering, which deal with complex, multidimensional, and nonlinear problems, and thus utilized the particle swarm optimization algorithm to optimize the hyperparameters of Gaussian processes. These applications demonstrate that PSO is adept at effective optimization in complex spaces fraught with uncertainties. Therefore, its application in determining the key hyperparameters of GP models can effectively circumvent the local optimum trap of traditional optimization methods, thereby obtaining a more robust model for subsequent optimization. When Xi, W. [18] was confronted with complex multi-parameter coupled problems such as the flow state optimization of the forebay in a pumping station, they combined the intelligent optimization algorithm with the surrogate model through PSO-GP, achieving rapid mapping and global optimization of the nonlinear relationship between the structural dimensions of the complex system and the uniformity of the flow field. Practical examples have shown that this method can automatically and efficiently search for the optimal combination of structural parameters, providing a novel and powerful data-driven tool for traditional hydraulic optimization.

1.4. Research Objectives

Although deep well alga control technology has demonstrated potential in engineering applications, the collection efficiency of its core component, the vortex well alga collector, largely depends on the complex matching relationship between its key structural parameters (such as the water depth and diameter of the suction inlet) and external hydraulic conditions (such as flow velocity). Currently, there is a lack of a systematic approach to quickly and accurately determine the optimal parameter combination, which restricts the full performance of this technology. Therefore, we have initiated research on this issue, aiming to achieve the following specific goals: determine the optimal parameter configuration of the vortex well alga collector, and verify the computational efficiency and prediction accuracy of the PSO-GP hybrid model in the optimization of environmental fluid equipment. Through post-analysis of the flow field structure and parameter sensitivity, we explain the principle of achieving optimal performance from the perspective of fluid mechanics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Model Design

To optimize the high-pressure alga control device of the deep submersible, based on the actual engineering and long-term field observation data obtained, it was confirmed that the high incidence period of blue algae in the engineering water area is concentrated from June to September. We particularly focused on the dominant meteorological conditions during this period. The measured data indicated that the southeast wind and south wind were the prevailing winds during this period. Based on this clear periodic pattern, this project has made forward-looking considerations in the overall layout design of the deep well alga control device. One of the core designs is that the overall layout direction of the device is adjustable. The blue alga deep well alga control project is taken as the prototype. The inner tube diameter of the deep submersible high-pressure alga control device is 1.5 m, the depth is 70 m, and the maximum working flow of the pressurizer can reach 18,400 m3/h. The main body of the adjustable vortex alga extractor is a double-layer sleeve structure alga suction tube, including an outer tube with an open top and an inner tube with an open top and bottom. The inner cylinder is suspended inside the outer cylinder and is sealed and connected with the outer cylinder through a sealing device, and an adjustment device for adjusting the height of the inner cylinder is also provided. The side wall of the alga suction cylinder is provided with an alga outlet that can be connected to the pump inlet. The high-efficiency adjustable vortex well alga harvester is made of stainless steel, and the adjustable stroke is 2.7 m. By adjusting the height of the cylinder, the deep-submersible high-pressure alga control device can maintain efficient operation. This study focuses on the optimal operation of the deep submersible high-pressure alga control device under different cylinder heights. Furthermore, UG modeling software was used to establish the geometric model of the river channel. To simplify the simulation calculation, alga suction tubes with double-layer sleeve structures of different heights were constructed, and 10 times the area of cyanobacteria floating on the water surface was established. The specific model design is shown in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4.

Model design of the high-pressure deep well alga control device.

2.2. Eulerian Model

To simulate the working process of the vortex well alga harvester, the unpressurized fresh water and the cyanobacteria floating on the water surface are set as liquids with two densities. The density of unpressurized fresh water is set to 1000 kg/m3, and the density of cyanobacteria floating on the water surface is set to 936.20 kg/m3 [19]. The commonly used multiphase flow models in Fluent mainly include the VOF model, Mixture model, and Eulerian model.

The VOF model is a surface tracking method based on a fixed Euler grid, by establishing two or more fluids (or phases) under the premise of mixing. This model is suitable when one or more fluid interfaces that are immiscible with each other need to be obtained. It is often used to deal with disjoint multiphase flow problems.

The Mixture model is a simplified multiphase flow model that uses the multiphase flow mixing characteristic parameters to describe the field equations of the flow field. Assuming that the coupling between the local phases on a short spatial scale is strong, it can be used to simulate two (multi) phase flows with different velocities in each phase, and it can also be used to simulate isotropic flows with strong coupling and phases moving at the same velocity in two (or multiple) phase flows. It is often used for low-load particle-laden flow, sedimentation, bubbly flow with low gas compatibility, etc.

The Eulerian model is the most complex multiphase flow model, known as the two-fluid model. The Eulerian model establishes a separate conservation equation for each phase, and its continuous phase and dispersed phase are treated as a single continuous medium. The Eulerian model establishes momentum equations and continuity equations for each phase, which are solved computationally by coupling pressure and interphase exchange coefficients. It is commonly used in the simulation of particle suspension. Since the model in this article needs to be in contact with each other, the Mixture model and the Eulerian model can be selected, but the Mixture model needs to solve multiple equations, and its calculation stability is slightly worse than that of the Eulerian model, so the Eulerian model is selected for solution in this article.

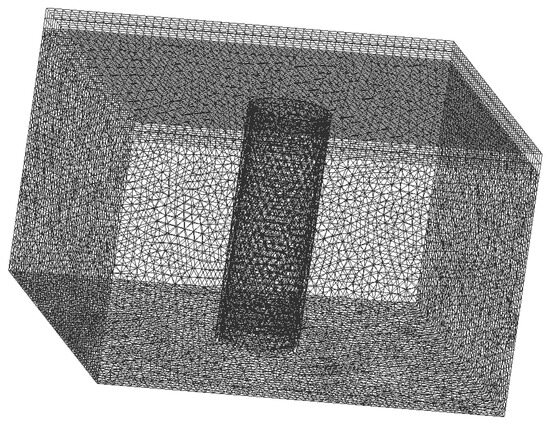

2.3. Mesh

UG modeling software is used to establish the geometric model of the river channel. Unstructured grids are divided and combined with actual engineering observations, selecting flow fields under different fence areas for model building and grid division. Considering the influence of the number of grids on the accuracy of numerical simulation, we first explore the head loss in the calculation domain. The calculation formula for the head loss is as follows:

hf is the head loss based on the average quality; Pin and Pout are the total pressures of the inlet section and outlet section; ρc is the density of water at 4 °C; g is the acceleration of gravity. The results show that the errors of all water levels are within 2%. When the grid number reaches 2,734,552, the water level error does not exceed 1%. Increasing the number of grids has little effect on the water level error calculation results. Considering the calculation accuracy and calculation time comprehensively, 2,730,000 grids are finally used for the calculation. The grid diagram is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Diagram of grid division.

2.4. CFD Numerical Settings

In this study, the CFD numerical simulation was set up as follows: Based on the judgment that the Reynolds number of the flow field is far above 4000, it was confirmed that the flow is in a fully developed turbulent state, so the standard k-ε turbulence model, which is computationally robust and suitable for such cases, was selected. For the free surface, since the core focus of this study is on the capture dynamics of algae near the suction inlet rather than the deformation process of the free liquid surface, the “rigid lid” approximation was adopted to simplify the calculation and focus on the core physical problem. The boundary conditions were set as velocity inlet, pressure outlet (located at the bottom of the alga suction pipe), and no-slip wall. The simulation was carried out in a transient manner, with the convergence criterion being that the residuals of all control equations drop below 10−6, while monitoring the alga collection efficiency to reach a stable state. The above settings aim to ensure the accuracy of the calculation while taking into account computational efficiency and the specificity of the problem.

3. Algorithm Optimization

3.1. Gaussian Process Model

The Gaussian process model can establish the mapping relationship between the training set input x and the output Y, and provide the corresponding prediction value of the test sample z+ according to this mapping relationship. The Gaussian process describes the distribution of a function, which is a collection of infinitely many random variables whose properties can be determined by the mean and covariance functions:

In the formula, is an arbitrary d-dimensional vector; and represent the mean function and covariance function, respectively. Therefore, GP can be expressed as

Assuming a finite training set of , containing n observations, among which represents a dimensional training input matrix composed of n d-dimensional training input vectors, and represents a corresponding training output vector composed of n training output scalars , the model can be expressed as

Additive noise pollutes the observed target value y, which is a random variable subject to a normal distribution. ’s mean value is 0, and the variance is , namely,

X is the input vector, and y is the observation value polluted by noise. The prior distribution of y is

where is the order symmetric positive-definite covariance matrix, matrix elements are used to measure the correlation between and , and the joint Gaussian prior distribution composed of n training sample outputs y and test sample outputs is

In this formula, is the order covariance matrix between the test output sample and n training samples, and is the order covariance matrix of the test output sample itself. The covariance function of the Gaussian process must satisfy the Mercer condition: a non-negative positive definite covariance matrix can be guaranteed for any point set, and the mean square index covariance function is used here:

In this formula, is the amplitude factor and is the distance . The only parameters that a Gaussian process needs to determine are a set of hyperparameters that determine the properties of the mean and covariance functions. According to the Bayesian principle, the most likely output value corresponding to can be predicted on the basis of the training set. We infer the largest possible predictive posterior distribution for y:

The most likely test output value is

3.2. Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm

The goal of the particle swarm optimization algorithm is to enable all particles to find the optimal solution in the multidimensional hyper body. First, we assign initial random positions and velocities to all particles in space. The position of each particle is then sequentially updated based on each particle’s velocity, the known optimal global position in the problem space, and the particle’s known optimal position. Particles gather or aggregate around one or more optimal points as the computation progresses by exploring and exploiting known vantage points in the search space.

3.3. PSO-GP Model

The traditional optimal hyperparameters of the model GP are obtained by the maximum likelihood estimation method. Specifically, the partial derivative of the hyperparameters is obtained by constructing the log-likelihood function of the conditional probability of the training sample, and then the conjugate gradient optimization method is used for the optimal hyperparameter solution. This optimization method leads to a large number of high-order computations during the training of the GP model, which affects the efficiency of the GP modeling. In response to the above problems, this work utilizes the intelligent PSO algorithm to optimize the hyperparameters of the GP model for rapid construction. The number of hyperparameters of the GP model is determined by the selected covariance function and mean function. When the particles are initialized, each particle represents a set of hyperparameters that are sequentially assigned to the covariance function and mean function of the GP model. The mean absolute error (MAE) between the prediction of the GP model and the sample is used as the PSO fitness function for global optimization. The particle position and velocity information is updated in each iteration, and the calculation is terminated when the maximum number of iterations is reached.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. PSO-GP Optimization Processing

After the PSO-GP model for the vortex well alga remover is established, the PSO algorithm is used to optimize the design. In the PSO-GP algorithm, the maximum number of iterations is 1000, with an acceleration constant and inertia weight specified, the initial population is 20, the dimension is 4, and the maximum working flow of the pressurizer can reach 18,400 m3/h. It takes about 6 days to build a numerical model for batch simulation, and the training time for the PSO-GP model is about 480 s. Using PSO-GP to optimize the hollow bottom sill of the forebay of the pumping station, the optimization process takes 300 s, and each generation of 20 particles (each particle represents 4 sets of size parameters) takes 0.3 s, which is far more than the time required by other algorithms, such as the standard Particle Swarm Optimization. The optimal size parameters were obtained through PSO-GP optimization, and the vortex well alga remover with the optimal size parameters was put into the numerical model simulation for verification. After the calculation is stabilized, the untreated cyanobacteria still exist in the waters of the model. To explore the relationship between the effect of alga control, it is determined that the alga content in the model under the initial conditions is . Then, we use the Eulerian method for numerical simulation and calculate the content of cyanobacteria that do not enter the inner pipe after the flow field is stable. The formula for calculating the alga entry efficiency of vortex well alga removers of different specifications is

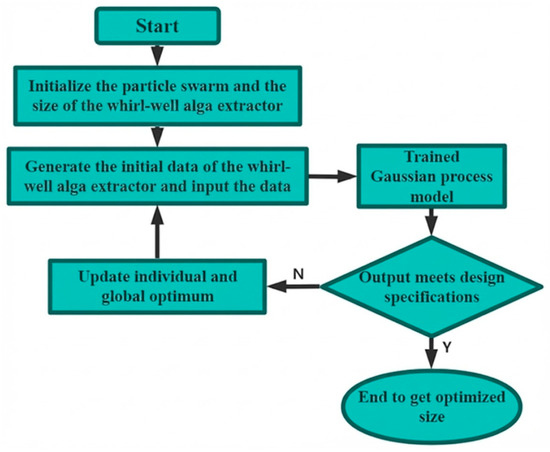

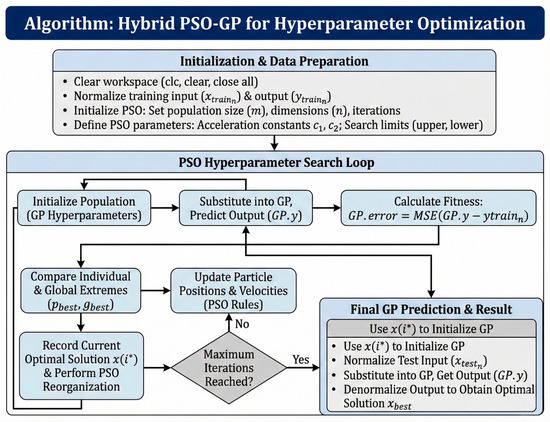

The flowchart and algorithm diagram of PSO-GP optimization are shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7 as follows.

Figure 6.

Diagram of PSO-GP optimization process.

Figure 7.

Diagram of the hybrid PSO-GP optimization workflow.

4.2. Analysis of PSO-GP Model Prediction Errors

When a deep-diving high-pressure alga controller is installed in water bodies, nutrient-rich algae naturally drain through its internal tubes. At 70 m depth, cyanobacteria cells are subjected to 0.7 MPa pressure, forcing them to disintegrate into small clusters or single-cell particles. The compression of gas vacuoles (false vacuoles) within cyanobacterial cells eliminates their buoyancy and biological activity, achieving rapid and efficient removal of surface algae. To ensure that the experimental results are universal, the inlet depth h, suction inlet diameter d, average water flow velocity v and distance of the fence L are selected as the research parameters. The specific parameters are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of the size of the alga eliminator.

In order to study the suction inlet of the deep-submersible high-pressure alga control device, 100 sets of randomly matched data were selected for analysis under conditions such as the water intake depth h, the suction inlet diameter d, the average flow velocity v of the water area, and the distance L between the suction inlet and the fence. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the vortex well alga remover, the water depth range of the suction inlet is 0–300 mm, the diameter range of the suction inlet is 140–480 mm, the average flow velocity range in this area is 0.05–0.2 m/s, and the distance between the center of the pipeline and the fence is 1000–2000 mm.

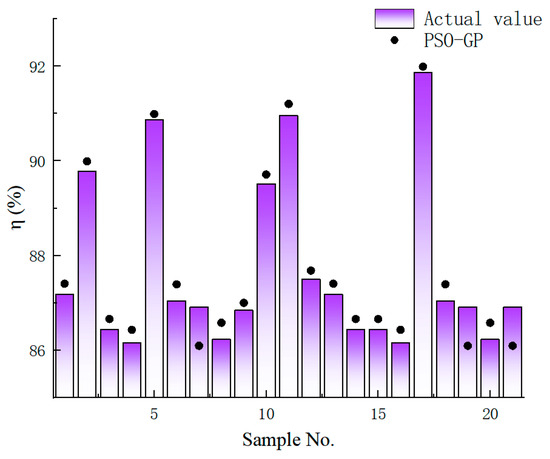

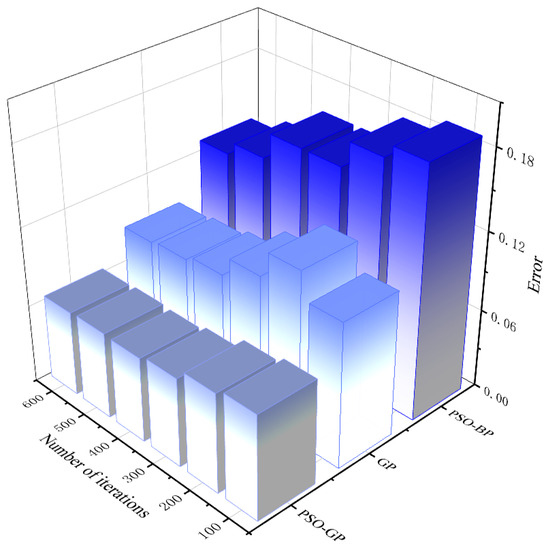

We use the numerical method to simulate the scheme, select 80 sets of data as the training samples of the PSO-GP model, manufacture schemes of the vortex well alga removers with different sizes according to these data, and build a numerical model for calculation. We use Tecplot 360 EX 2024 R1 software for post-processing to obtain the working efficiency corresponding to different sizes of deep well alga removal schemes, and use the working efficiency as the training output data of the PSO-GP model to establish the model. Then, we select another 20 groups as the test samples; the output of the PSO-GP model was , and the output of each group of corresponding physical model test processing was . In the process of establishing the PSO-GP model, the formula of the average absolute error between the predicted output of the model and the 20 sets of test data is used as the fitness function of PSO-GP. The prediction errors of the PSO-GP model on the test set are shown in Figure 9 below:

Figure 9.

Histogram of PSO-GP model prediction absolute errors.

In order to verify the advantages of the PSO-GP algorithm, we select the common PSO-GP algorithm and the Gaussian process algorithm for comparison and study; substitute the flow uniformity index as the training input data, respectively; and perform iterative calculations with different iteration times. The results are compared with the real values, and the results are shown in Figure 10. The calculation results show that, compared with the PSO-GP algorithm and the Gaussian process algorithm, the PSO-GP algorithm has a significantly lower computational cost and smaller errors, especially in the number of iterations. For high-accuracy applications, the PSO-GP algorithm offers a favorable balance of computational speed and precision. The final optimal dimensions obtained are a water depth at the suction inlet of 200 mm, diameter of 480 mm, fence distance of 2000 mm, and velocity of 0.12 m/s. Under these conditions, the efficiency of blue-green alga entry is 92%, which is in line with engineering practice and has been verified in the project. The following text will conduct a further analysis of the blue-green alga removal process under this optimized size.

Figure 10.

Comparison chart of different algorithms.

4.3. Analysis of the Alga Removal Process

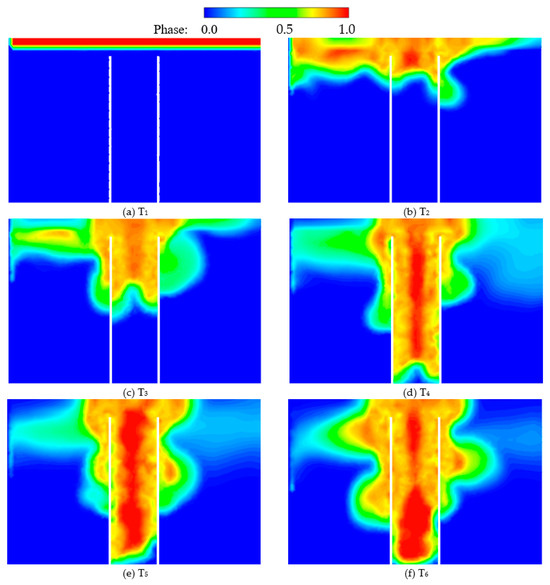

A numerical simulation was conducted on the process of blue algae being drawn into the vortex well of the algae extraction device, and six key moments (T1–T6) were selected for elaboration and explanation. Figure 11 shows the phase change process of cyanobacteria. Figure 11a T1 is the initial state; at the beginning, the cyanobacteria float on the water’s surface. In Figure 11b T2, Figure 11c T3, the booster pump starts to draw water, and the movement state of the surface layer of cyanobacteria begins to fluctuate. Due to the promotion of the water flow, there are more cyanobacteria on the right side, and the middle part of the cyanobacteria begins to enter the pipe, while some cyanobacteria on the right side have not yet entered. The inhaled cyanobacteria are blocked on the outside of the pipe. In Figure 11d T4, the cyanobacteria on the left are blocked by the water surface fence and cannot escape, and they gather at a position slightly below the water surface. The cyanobacteria in the middle pipe are gradually sucked into the booster pump. In the pipe, the cyanobacteria close to the pipe wall drop fast, the cyanobacteria close to the middle of the pipe drop slowly, and the cyanobacteria blocked outside the pipeline diverge and distribute on the right side of the pipe. In Figure 11e T5, Figure 11f T6, the blocked cyanobacteria on the left and right sides gradually move closer to the middle pipe, and then are gradually sucked into the pipe, but there are still some cyanobacteria on the left and right sides that diverge and distribute in the water body.

Figure 11.

Cloud image of phase motion of cyanobacteria. (a–f) represent six moments of the cyanobacteria’s inhalation process.

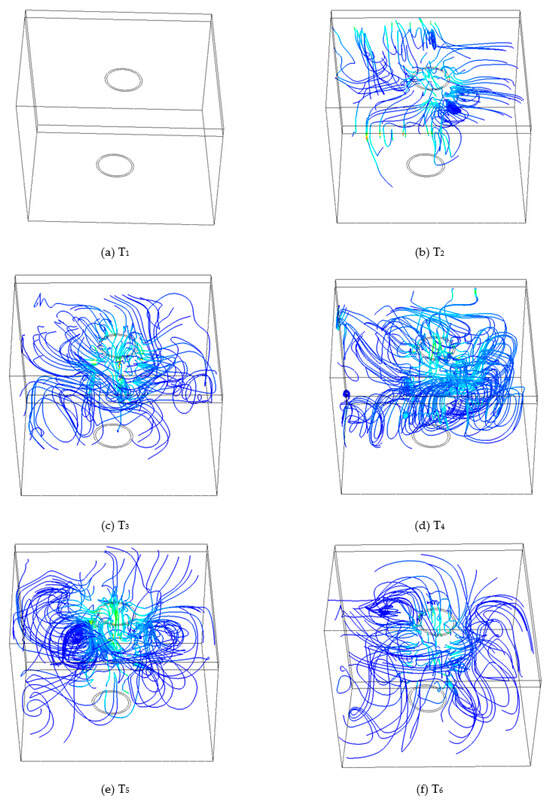

Figure 12 shows the change process of the streamline in the numerical simulation flow field. Figure 12a T1 depicts the initial state, and the algae float on the water surface at the beginning; As the booster pump starts to pump water, the cyanobacteria on the surface in Figure 12b T2 begin to move closer to the central water suction port. In Figure 12c T3, the streamline disturbance intensifies, and some cyanobacteria bypass and sink from both sides of the pipe. It can be seen in Figure 12d T4 that there are long strips of blue-green alga spiral vortex distributed outside the pipe, indicating that the blue-green algae outside the pipe are constantly rolling around the pipe and gradually being sucked into the pipe. It can be seen from Figure 12e T5, Figure 12f T6v that the stream distribution is relatively regular at this time, vertical recirculation zones are distributed around the outside of the pipe, and the cyanobacteria distributed in these recirculation zones are difficult to circulate into the pipe.

Figure 12.

Streamlines of the movement process of cyanobacteria. (a–f) represent six moments of the cyanobacteria’s inhalation process.

The phase change process of cyanobacteria and streamline distribution in the flow field were comprehensively analyzed. It was found that algae floated on the water surface at the beginning and water flowed from right to left in the figure. When the pump began to draw water, the motion state of the surface layer cyanobacteria began to fluctuate. The water on the left side pushed the surface layer cyanobacteria to move to the right, and some of the cyanobacteria entered the pipe, while the cyanobacteria on the right side were blocked outside the pipe.

The cyanobacteria on the left are prevented from escaping by the surface fence. They gather slightly below the surface and move slowly towards the suction inlet on the right under the suction force of the pump. Some of the algae float up into the pipe, while some sink down along the left side wall. As time goes by, the sinking cyanobacteria gradually flow back up to form a reflux area under the influence of buoyancy and suction, and are sucked into the pipe. However, some cyanobacteria still cannot enter the pipe and are distributed in the water.

The cyanobacteria in the middle pipe are gradually sucked into the pump, and the cyanobacteria suction speed is faster at the wall of the pipe. With the cyanobacteria suction movement, the cyanobacteria suction speed is faster at the side wall friction of both sides of the pipe.

The movement of cyanobacteria on the right is similar to that on the left. Affected by buoyancy and suction, the blocked cyanobacteria gradually back flow upward to form a back flow area, before being sucked into the pipe. However, some cyanobacteria are still blocked outside the back flow area on the right and cannot be recycled into the pipe.

It can be seen from the above research that the vortex well algal extractor can effectively remove the surface layer cyanobacteria, but there are some cyanobacteria outside the pipe that cannot be removed.

5. Conclusions

To solve the increasingly serious cyanobacterial bloom problem in oceans and lakes, this study optimized the adjustable vortex well algal extractor in the deep well algal removal project, and simulated the working process of the vortex well algal extractor using numerical simulation methods. It was found that, due to structural limitations, there was a cyanobacterial reflux area outside the vortex well algal extractor pipe, and the vortex well algal extractor could not be pressurized. This limitation will affect the efficiency of the vortex well algal extractor.

The PSO-GP model was established by combining the particle swarm optimization algorithm with the Gaussian process, and the model was used to optimize the design of the adjustable vortex well alga extractor. This effectively reduced the time of regulating the vortex well alga extractor to work efficiently under different conditions, and improving the working efficiency of the vortex well alga extractor. The optimal dimensions of the adjustable vortex well alga remover optimized by the PSO-GP model are as follows: during the test period, the water depth at the suction inlet is 200 mm, the diameter of the suction inlet is 480 mm, the average flow velocity of the water area is 0.12 m/s, and the distance between the center of the pipe and the fence is 2000 mm. A feasibility numerical simulation analysis was conducted on this size of the adjustable vortex well alga remover, and the results showed that, under the optimal size conditions, the blue-green alga entry efficiency could reach 92%. That is, this method has practical value in the optimal design of the adjustable vortex well alga remover.

Author Contributions

Z.F. analyzed the data and wrote the paper; W.X. proposed the method and designed the model; W.X. completed the numerical simulations. Methodology, Z.F.; writing—original draft, Z.F.; writing—review and editing, W.X.; software, W.X.; validation, W.X.; formal analysis, Z.F.; investigation, W.L. (Weigang Lu); supervision, W.L. (Wen Lu); project administration, L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Open Research Fund Program of the State Key Laboratory of Eco-hydraulics in Northwest Arid Region, Xi’an University of Technology (Grant No. 2023KFKT-24); the High-tech Key Laboratory of Agricultural Equipment and Intelligence of Jiangsu Province and College of Agricultural Engineering, Jiangsu University (MAET202304); and the Open Project of Jiangsu Province High Efficiency and Energy saving Large Axial Flow Pump Station Engineering Research Center in 2022 (grant number ECHEAP027).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Wen Lu and Lidong Chen were employed by the company Jiangsu Water Resources Survey and Design Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Yu, P.; Teng, Z.; Wan, H.; Shi, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y. scatalysis: Exploring the mechanism of photocatalytic algal removal. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, C. The performance of several enhanced treatment processes for treatment of algae-containing raw water in typical seasons. Desalination Water Treat. 2017, 60, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xue, J.; Sun, W.; Chen, W.; Liu, B.; Jin, L.; Wang, X. Efficiency and mechanism of ozonated microbubbles for enhancing the removal of algae and algae-derived organic matter. Chemosphere 2023, 312, 137220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; Yang, J.; Tian, J.; Ma, F.; Tu, G.; Du, M. Electro-coagulation–flotation process for algae removal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 177, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, C.; Wu, X.; Tian, Y. Removal of Algae and Algal Toxins from a Drinking Water Source Using a Two-Stage Polymeric Ultrafiltration Membrane Process. Polymers 2023, 15, 4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.; Yoon, D.; Park, S.H.; Park, N.S. An experimental study for removing algae particles using a metal mesh membrane. Desalination Water Treat. 2019, 149, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlond, G.; D’Aoust, P.M.; Kinsley, C.; Delatolla, R. Wastewater lagoon solids, phosphorus, and algae removal using discfiltration. Water Qual. Res. J. 2020, 55, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Li, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lei, Z.; Lu, B.; Zhou, B. Effect of algae growth on aerobic granulation and nutrients removal from synthetic wastewater by using sequencing batch reactors. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 179, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipigroch, K. The use of algae in the process of heavy metal ions removal from wastewater. Desalination Water Treat. 2018, 134, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Tan, H.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Zhao, M.; Zheng, X. Enhancement of algae ponds for rural domestic sewage treatment by prolonging daylight using artificial lamps. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 228, 113031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, H.S.; Kang, S.H.; Nam, S.; Kim, E.J.; Hwang, T.M. CFD modelling of cyclonic-DAF (dissolved air flotation) reactor for algae removal. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2019, 22, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Tian, L.; Ju, L.; Jia, R.; Song, W.; Li, J. Pilot test study on the performance of multiphase flow pump DAF equipment and reservoir water pollution removal by the DAF process. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 46, 102543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, J.; Lin, Q.; Chen, L. Parameter optimization of ultrasound technology for algae removal and its application in Pengxi river of three Gorges Reservoir. Asian J. Chem. 2014, 26, 1165–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Chen, H.; Zhang, L.S. Experimental Study on the Pressure-induced Lysis of Cyanobacterial Microcysts. Environ. Eng. 2023, 41, 201–203. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Q. The Control of Blue Algae in Aquaculture Water Bodies and the Improvement of Water Quality Through Deep Well Circulation Treatment. Master’s Thesis, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Benuwa, B.B.; Ghansah, B.; Wornyo, D.K.; Adabunu, S.A. A Comprehensive Review of Particle Swarm Optimization. Int. J. Eng. Res. Afr. 2016, 23, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajihassani, M.; Jahed Armaghani, D.; Kalatehjari, R. Applications of Particle Swarm Optimization in Geotechnical Engineering: A Comprehensive Review. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2018, 36, 705–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, W.; Lu, W.G.; Wang, C.; Xu, B. Optimization of the Hollow Rectification Sill in the Forebay of the Pump Station Based on the PSO-GP Collaborative Algorithm. Shock. Vib. 2021, 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.X.; Cong, H.B.; Gao, Z.J. Hybrid stress under the condition of cyanobacteria movement characteristics study. J. Environ. Sci. 2014, 35, 1781–1787. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).