Simulation and Optimization of Collaborative Scheduling of AGV and Yard Crane in U-Shaped Automated Terminal Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Based on a simulation platform, a U-shaped ACTs simulation model with a standardized layout and complete operational logic is constructed. In the simulation model, the accuracy of the operation process of AGVs and YCs is mainly considered. For this reason, a refined road network structure for the horizontal transportation area is built, real operational logics such as AGVs charging and parking waiting in buffer zones are implemented, and a refined control logic for YCs single-step actions is designed—all to ensure high-precision reproduction of equipment operations by the simulation model. The high-precision nature of this simulation model provides a reliable data foundation for the subsequent iterative optimization of the multi-objective simulation optimization algorithm.

- (2)

- Aiming at the multi-objective optimization problem of AGVs and YCs collaborative scheduling in U-shaped ACTs, this paper utilizes the powerful learning ability of the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm and the multi-objective optimization ability of the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II), combined with a high-precision simulation model, and for the first time proposes an improved NSGAII multi-objective simulation optimization method based on PPO (INSGAII-PPO). This method uses the simulation model to perform real-time full-process simulation of the scheduling schemes generated by the multi-objective optimization algorithm, and feeds back high-fidelity data to the algorithm for iterative optimization. This ensures that the final solutions obtained are more in line with practical requirements and provide a guiding basis for real-world decision-making.

- (3)

- Considering the complexity of the multi-objective optimization for AGVs and YCs collaborative scheduling, a hybrid initialization strategy integrating Logistic chaotic mapping and Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) is proposed. To enhance the search capability and efficiency of the algorithm, a dynamic genetic operator selection strategy is proposed using the learning mechanism of PPO, which is used to select appropriate genetic operators from different candidate operators; a prioritized experience replay mechanism and an ε-greedy (Epsilon-greedy) strategy are also introduced. Finally, in accordance with the characteristics of multi-objective problems, a preference-based hybrid weighted Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) is designed to select the optimal solution from the Pareto solution set, thereby enabling more accurate and preference-oriented multi-objective decision-making.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Scheduling Research Based on Mathematical Models

2.2. Scheduling Research Based on Simulation Methods

2.3. Scheduling Research Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning

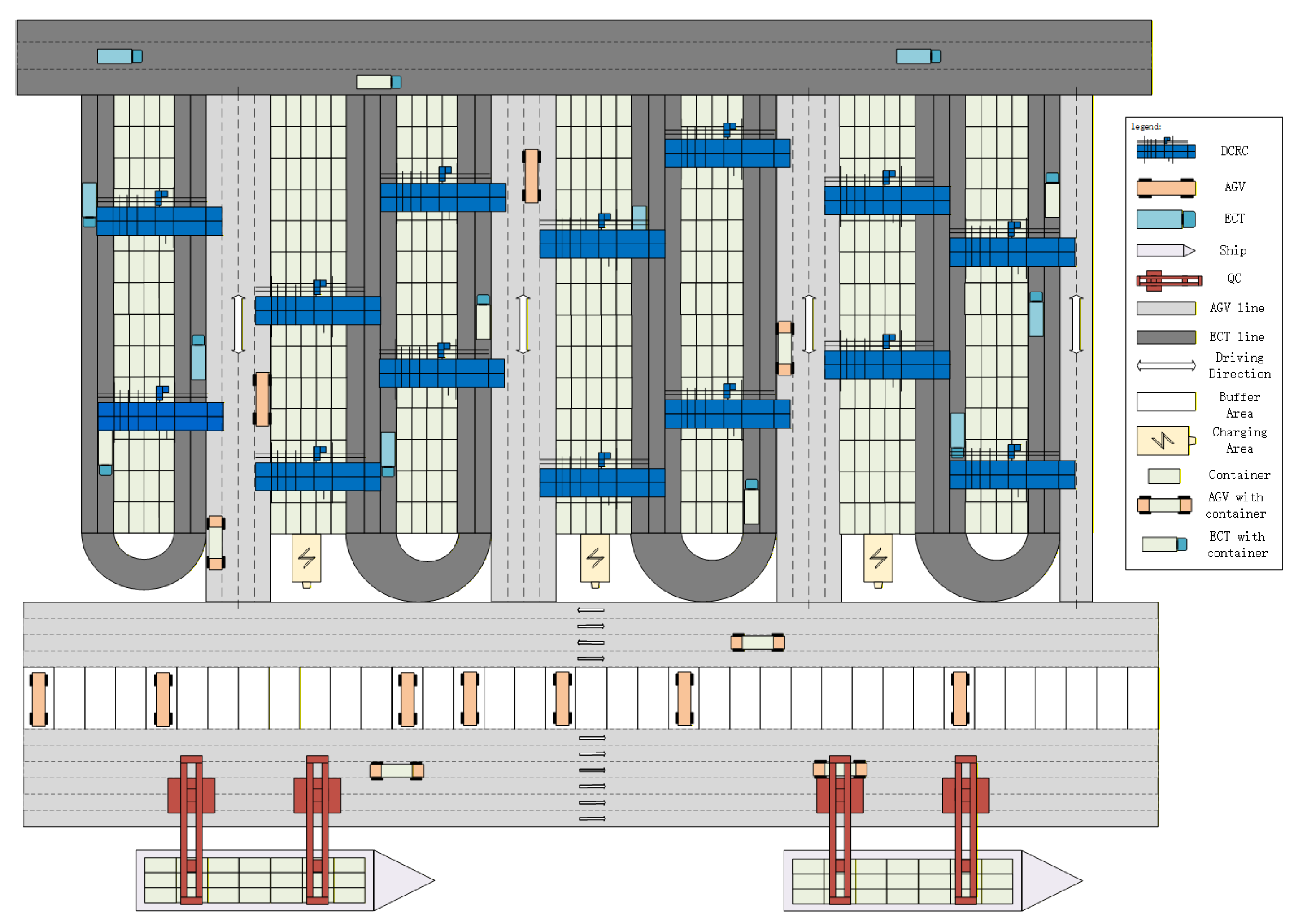

3. Simulation Modeling of U-Shaped Automated Container Terminal

3.1. U-Shaped ACTs Simulation Model

3.2. Simulation Assumptions

- Containers are standardized 20-foot equivalent units (TEUs).

- Container flipping issues are not considered.

- Storage locations for each container are randomly generated.

- All containers are imported.

- Only one container is allowed on each AGV.

- External trucks and their corresponding lanes are not considered.

- All lanes in the horizontal transport zone are one-way.

- A fixed number of QCs and YCs are used in the simulation.

- The yard internal loading/unloading lanes are simulated using multiple loading/unloading points.

- Upon reaching the specified bay position, the AGVs move to a buffer zone. It can only leave the buffer zone and exit the yard after the YC has retrieved the container.

- The parameters and speed of each part of the YC are set in the simulation, which is used to simulate the movement time of each part.

- If the AGV does not need to be charged after completing its task, it will return to the buffer to wait for the next job.

- The AGV travels according to the shortest path principle.

- AGVs operate in either loaded or empty states, with varying power consumption between states; AGVs consume no energy while in a waiting state.

3.3. AGV and YC Control Module

3.4. Charge Module

3.5. Statistics Module

4. Improved NSGAII-PPO Simulation Optimization Method

4.1. Optimization Objective Calculation

4.2. Chromosome Encoding and Population Initialization

- (1)

- Taking AGV1 as an example, it will first transport Container No. 4, then Container No. 2 and No. 7, and finally Container No. 3.

- (2)

- For YCs, taking YC1 as an example, it first unloads Container No. 8 from AGV3, then sequentially unloads Container No. 4 from AGV1, Container No. 5 from AGV2, Container No. 10 from AGV2, and Container No. 9 from AGV3.

- (3)

- Interpretations for other AGVs and YCs follow the same steps.

4.3. Dynamic Operator Selection Strategy

- (1)

- State Space: During the algorithm’s iterative process, the agent’s state space design incorporates several key factors to comprehensively reflect the search state. These factors include diversity within the current population across both the objective space and decision space, indicating whether the population is in an exploration or exploitation phase. The distribution characteristics of the Pareto frontier serve as the core metric for evaluating the quality of non-dominated solution distributions and form the foundational component of the state space. The algorithm’s convergence progress quantifies its approximation to the optimal solution. The state space constructed from these factors provides a comprehensive basis for the agent to assess the population’s state and select appropriate operation operators. Therefore, the agent’s state can be represented as shown in Equation (4):

- (2)

- Action Space: In the dynamic operator selection strategy, agents must choose a combination of operators from 3 crossover operators and 2 mutation operators. The combination of these two types of genetic operators yields a total of 6 possibilities. Thus, the number of actions is equivalent to the product of the number of candidate operators. An agent’s action can be represented as shown in Equation (5):

- (3)

- Reward Mechanism: The design of the reward mechanism is crucial for DRL. For selecting genetic operators in evolutionary algorithms, existing research typically modifies the actual optimization objective value into a fitness value as the reward for the selected operator. However, fitness values gradually decrease or exhibit significant fluctuations as the algorithm iterates, and using them directly as rewards may compromise the stability of agent learning. To mitigate this issue, this paper proposes a novel hybrid reward mechanism. First, if an action improves a specific optimization objective, the reward is set to 1; otherwise, it is 0. Second, the population’s state change reflects the selected genetic operator’s optimization capability. The calculation of rewards relies on the state change pre-action and post-action: a reward of 1 is provided when the state is improved, and 0 if it is not. The reward calculation is shown in Equation (6).

4.4. Selection of the Final Solution

5. Experiments and Results

5.1. Experimental Parameter Settings

5.2. Performance Metrics

- (1)

- Hypervolume (HV) is a comprehensive metric that calculates the cumulative normalized volume covered by a solution set relative to a given reference point. A larger hypervolume value indicates better convergence and diversity of the solution set. Hypervolume is defined as follows:

- (2)

- Inverted Generational Distance (IGD) is a widely used metric for evaluating multi-objective optimization algorithms. It comprehensively assesses the performance of solution sets by measuring aspects such as diversity and proximity. A smaller value indicates better diversity and distribution. Its definition is as follows:

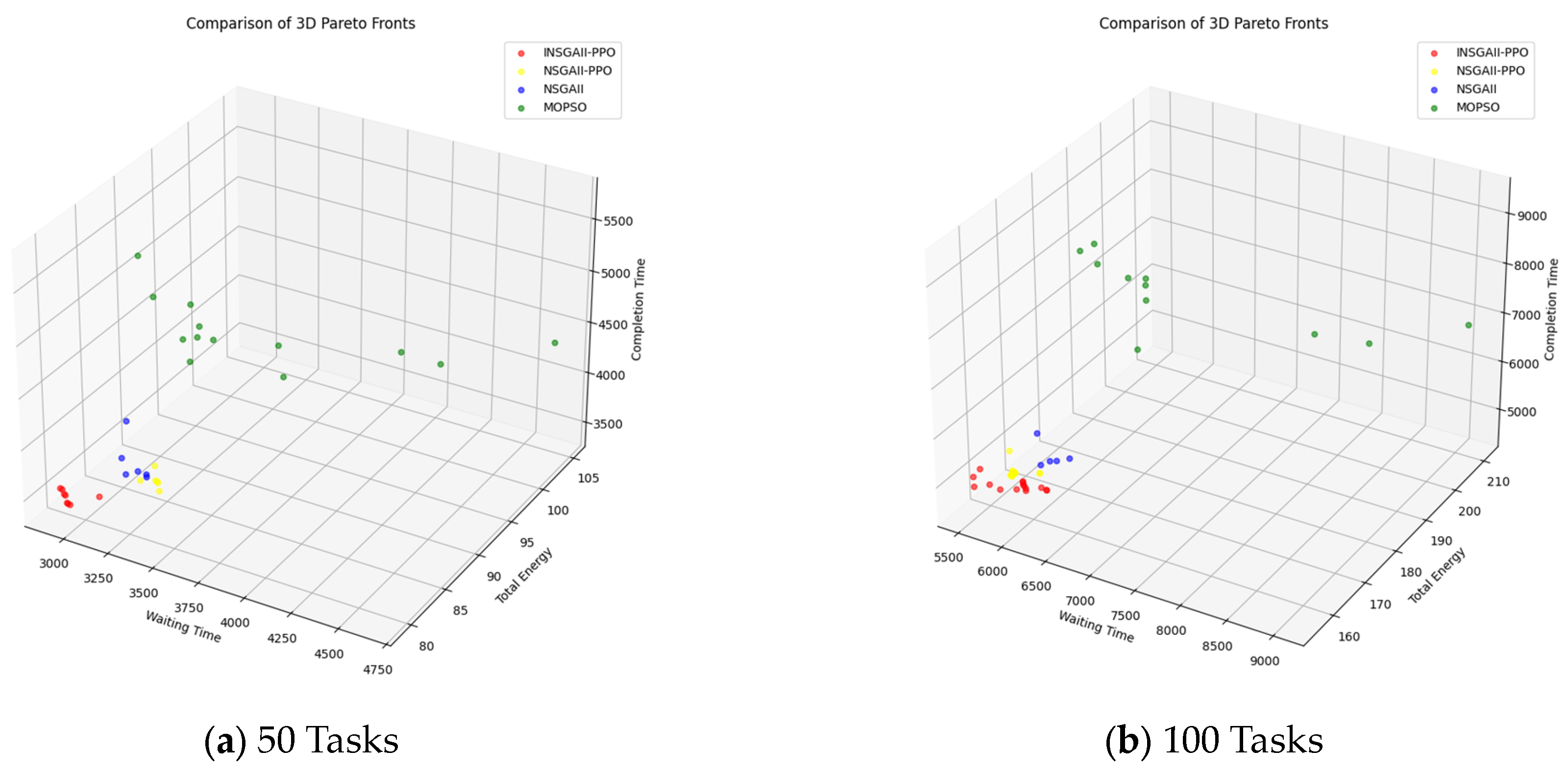

5.3. Comparison and Analysis of Optimization Algorithms

5.4. Comparison of Final Solution Selection Methods

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, X.; He, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tong, L.C.; Shang, P.; Zhou, X. Yard crane and AGV scheduling in automated container terminal: A multi-robot task allocation framework. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 114, 241–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.K.; Lee, L.H.; Chew, E.P. Analysis on high throughput layout of container yards. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 5345–5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Yu, F.; Yao, H.; Yang, Y. Multi-equipment coordinated scheduling strategy of U-shaped automated container terminal considering energy consumption. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 174, 108804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gu, W.; Shang, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, G. Research on dynamic job shop scheduling problem with AGV based on DQN. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Sang, H.; Tian, M.; Yu, Y.; Chen, S. Integrated scheduling problem of multi-load AGVs and parallel machines considering the recovery process. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 94, 101861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Meng, W. Collaborative algorithm of workpiece scheduling and AGV operation in flexible workshop. Robot. Intell. Autom. 2024, 44, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Hu, H.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, C. AGV scheduling in automated container terminals considering multi-load strategy and charging requirements. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2025, 15, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qi, L.; Luan, W.; Ma, H. Double-cycling AGV scheduling considering uncertain crane operational time at container terminals. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, J.; Xu, B.; Yin, W.; Yang, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, Y. A Flexible Scheduling for Twin Yard Cranes at Container Terminals Considering Dynamic Cut-Off Time. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Lee, B.K.; Li, H. Integrated optimization on yard crane scheduling and vehicle positioning at container yards. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 138, 101966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Sheu, J.B. Integrated scheduling optimization of AGV and double yard cranes in automated container terminals. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2024, 179, 102871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Hu, H.; Cheng, C. Collaborative scheduling of handling equipment in automated container terminals with limited AGV-mates considering energy consumption. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhu, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, S. Multiple equipment scheduling and AGV trajectory generation in U-shaped sea-rail intermodal automated container terminal. Measurement 2023, 206, 112262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, S.; Wu, Y.; Feng, J.; Lu, W.; Wu, L.; Postolache, O. Integrating multi-equipment scheduling with accurate AGV path planning for U-shaped automated container terminals. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 209, 111427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhuang, Z.; Qin, W.; Tan, R.; Liu, C.; Huang, H. Systems thinking and time-independent solutions for integrated scheduling in automated container terminals. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.P.; Wang, C.N.; Fu, H.P.; Dang, T.T. Joint scheduling of yard crane, yard truck, and quay crane for container terminal considering vessel stowage plan: An integrated simulation-based optimization approach. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Liu, C. Modeling and analysis for an automated container terminal considering battery management. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 156, 107258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jia, N.; Song, D.; Liu, B. Modelling and analyzing the stacking strategies in automated container terminals. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 187, 103608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, S. Energy-aware Integrated Scheduling for Container Terminals with Conflict-free AGVs. J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. 2023, 32, 413–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, L. A three stage optimal scheduling algorithm for AGV route planning considering collision avoidance under speed control strategy. Mathematics 2022, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junqueira, C.; de Azevedo, A.T.; Ohishi, T. Solving the Integrated Multi-Port Stowage Planning and Container Relocation Problems with a Genetic Algorithm and Simulation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, Y.; Tian, Q.; Feng, T.; Wang, W.; Cao, Z.; Song, X. A decomposition-based optimization method for integrated vehicle charging and operation scheduling in automated container terminals under fast charging technology. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 180, 103338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Su, X.; Li, G.; Jin, X.; Yu, M. A simulation based meta-heuristic approach for the inbound container housekeeping problem in the automated container terminals. Marit. Policy Manag. 2023, 50, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Liang, Z.; Teng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cong, X. The inbound container space allocation in the automated container terminals. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 179, 115014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; He, L.; Wu, H. A deep reinforcement learning based multi-agent simulation optimization approach for IGV bidirectional task allocation and charging joint scheduling in automated container terminals. Comput. Oper. Res. 2025, 183, 107189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Jiang, J.; Shi, Q.; Fu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, L. GA-HPO PPO: A Hybrid Algorithm for Dynamic Flexible Job Shop Scheduling. Sensors 2025, 25, 6736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Huang, Z.; Xiang, X.; Liu, X. Real-time AGV scheduling optimisation method with deep reinforcement learning for energy-efficiency in the container terminal yard. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 7722–7742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, A.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, C. Multi-agent deep reinforcement learning for recharging-considered vehicle scheduling problem in container terminals. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 16855–16868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, B.M.; You, S.S.; Kim, H.S. Efficient routing for multiple AGVs in container terminals using hybrid deep learning and metaheuristic algorithm. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Yang, X.; Xiao, S.; Wang, F. Anti-conflict AGV path planning in automated container terminals based on multi-agent reinforcement learning. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhuo, X.; Lian, Z.; Zhou, X. A Reinforcement Learning—Based AGV Scheduling for Automated Container Terminals with Resilient Charging Strategies. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 19, e70027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Tong, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, C. Integrated Scheduling Optimization for Automated Container Terminal: A Reinforcement Learning-Based Approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 19, 10019–10035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liang, J.; Feng, J. Simulation and Optimization of Automated Guided Vehicle Charging Strategy for U-Shaped Automated Container Terminal Based on Improved Proximal Policy Optimization. Systems 2024, 12, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Guo, Y.; Qi, Y.; Fang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Li, M.; Zhen, Z. Real-time twin automated double cantilever rail crane scheduling problem for the U-shaped automated container terminal using deep reinforcement learning. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Jie, D.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Wen, F.; Song, H. Integrated scheduling optimization of U-shaped automated container terminal under loading and unloading mode. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 162, 107695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.P.; Wang, C.N.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Dang, T.T.; Pan, Y.J. Hybridizing WOA with PSO for coordinating material handling equipment in an automated container terminal considering energy consumption. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 60, 102410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Li, X.; Ma, H.; Zhang, X.; Tan, K.C.; Jin, Y. Deep reinforcement learning based adaptive operator selection for evolutionary multi-objective optimization. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2022, 7, 1051–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Lu, T.; Ma, D.; Wang, D.; Qu, F. Ship route and speed multi-objective optimization considering weather conditions and emission control area regulations. Marit. Policy Manag. 2021, 48, 1053–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhu, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Tan, K.C. Integrated scheduling of yard and rail container handling equipment and internal trucks in a multimodal port. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 25, 2987–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, J.; Espitia, H.; Montenegro, C.; González Crespo, R. Statistical analysis of a multi-objective optimization algorithm based on a model of particles with vorticity behavior. Soft Comput. 2016, 20, 3521–3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Xiang, Z. Adaptive operator selection with dueling deep Q-network for evolutionary multi-objective optimization. Neurocomputing 2024, 581, 127491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Li, W.; Gao, K.; He, L.; Zhou, Y. An improved NSGAII for integrated container scheduling problems with two transshipment routes. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 14586–14599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Description | Parameter | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total energy consumption of AGV operation (kwh) | Energy consumption rate of empty movement (kwh/h) | ||

| Total power consumption of AGV (Ah) | Energy consumption rate of load lifting (kwh/h) | ||

| AGV rated operating voltage (V) | Energy consumption rate of empty lifting (kwh/h) | ||

| Total energy consumption of YC operation (kwh) | Load movement time (h) | ||

| Total energy consumption of the YC movement (kwh) | Empty movement time (h) | ||

| Total energy consumption of YC lifting (kwh) | Load lifting time (h) | ||

| Energy consumption rate of load movement (kwh/h) | Empty lifting time (h) |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Lifting energy consumption rate of the YC under heavy load | 115 kwh/h |

| Mobile energy consumption rate of the YC under heavy load | 55 kwh/h |

| Lifting energy consumption rate of the YC under without load | 55 kwh/h |

| Mobile energy consumption rate of the YC under without load | 55 kwh/h |

| Algorithm | Definition |

|---|---|

| INSGAII-PPO | NSGAII-PPO combines hybrid initialization and other improvements |

| NSGAII-PPO | NSGAII combines the dynamic operator selection of PPO |

| NSGAII | Baseline NSGA-II |

| MOPSO | Baseline MOPSO |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Movement speed of the YC | 1 m/s |

| Mobile speed of the YC trolley | 1 m/s |

| Speed of YC lifting device | 1 m/s |

| AGV operating Speed | 4 m/s |

| AGV battery consumption when load | 1.2%/km |

| AGV battery consumption when empty | 0.6%/km |

| Index | Number of Tasks | Number of AGV | INSGAII-PPO | NSGAII-PPO | NSGAII | MOPSO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HV | IGD | HV | IGD | HV | IGD | HV | IGD | |||

| 1 | 20 | 3 | 0.0018 | 0.0021 | 0.0016 | 0.0051 | 0.0017 | 0.0018 | 0.0016 | 0.0149 |

| 2 | 20 | 4 | 0.0015 | 0.0083 | 0.0017 | 0.0070 | 0.0012 | 0.0194 | 0.0017 | 0.0065 |

| 3 | 30 | 4 | 0.0036 | 0.0104 | 0.0054 | 0.0053 | 0.0022 | 0.0406 | 0.0022 | 0.0651 |

| 4 | 30 | 5 | 0.0046 | 0.0006 | 0.0017 | 0.0406 | 0.0025 | 0.0264 | 0.0029 | 0.0353 |

| 5 | 50 | 5 | 0.0239 | 0.0022 | 0.0189 | 0.0258 | 0.0190 | 0.0257 | 0.0108 | 0.1215 |

| 6 | 50 | 6 | 0.0094 | 0.0087 | 0.0087 | 0.0207 | 0.0118 | 0.0026 | 0.0045 | 0.0971 |

| 7 | 80 | 6 | 0.0769 | 0.0122 | 0.0927 | 0.0010 | 0.0531 | 0.0913 | 0.0294 | 0.2554 |

| 8 | 80 | 8 | 0.0670 | 0.0173 | 0.0637 | 0.0232 | 0.0502 | 0.0498 | 0.0333 | 0.1585 |

| 9 | 100 | 8 | 0.1215 | 0.1143 | 0.1292 | 0.1106 | 0.0517 | 0.2525 | 0.0284 | 0.3720 |

| 10 | 100 | 10 | 0.2772 | 0.0002 | 0.2389 | 0.0199 | 0.2117 | 0.0535 | 0.1119 | 0.2606 |

| 11 | 120 | 8 | 0.1756 | 0.0015 | 0.1555 | 0.0172 | 0.1342 | 0.0568 | 0.0734 | 0.2708 |

| 12 | 120 | 10 | 0.1177 | 0.0018 | 0.0981 | 0.0180 | 0.0184 | 0.2430 | 0.0262 | 0.2774 |

| 13 | 140 | 8 | 0.1934 | 0.0047 | 0.1918 | 0.0119 | 0.0455 | 0.2209 | 0.0635 | 0.3321 |

| 14 | 140 | 10 | 0.4085 | 0.0023 | 0.3593 | 0.0235 | 0.2709 | 0.0971 | 0.0997 | 0.3421 |

| 15 | 160 | 10 | 0.8446 | 0.0304 | 0.9386 | 0.0003 | 0.3872 | 0.3136 | 0.2261 | 0.5016 |

| 16 | 160 | 12 | 1.0668 | 0.0072 | 0.7897 | 0.1064 | 0.2339 | 0.4747 | 0.2826 | 0.5110 |

| 17 | 180 | 10 | 0.9322 | 0.0044 | 0.6860 | 0.0587 | 0.6588 | 0.1211 | 0.1654 | 0.5422 |

| 18 | 180 | 12 | 1.0309 | 0.0124 | 0.7739 | 0.0892 | 0.2699 | 0.4249 | 0.1602 | 0.5963 |

| 19 | 200 | 10 | 1.0097 | 0.0023 | 0.9452 | 0.0250 | 0.4419 | 0.2628 | 0.1904 | 0.5930 |

| 20 | 200 | 12 | 0.5604 | 0.0098 | 0.5433 | 0.0159 | 0.2243 | 0.2219 | 0.1488 | 0.4285 |

| 21 | 200 | 14 | 1.4289 | 0.0078 | 1.2342 | 0.0402 | 1.0743 | 0.1082 | 0.2555 | 0.6481 |

| 22 | 250 | 12 | 2.0329 | 0.0176 | 1.3172 | 0.1952 | 0.3801 | 0.6753 | 0.4843 | 0.6405 |

| 23 | 250 | 14 | 1.4679 | 0.0222 | 1.3331 | 0.0468 | 0.9020 | 0.2025 | 0.4679 | 0.4177 |

| 24 | 250 | 16 | 1.8666 | 0.0074 | 1.6394 | 0.0306 | 0.9282 | 0.3443 | 0.5922 | 0.5202 |

| 25 | 300 | 14 | 2.6819 | 0.0178 | 2.6538 | 0.0243 | 1.0903 | 0.4138 | 0.6514 | 0.6976 |

| 26 | 300 | 16 | 2.0792 | 0.0054 | 1.4998 | 0.1202 | 0.9093 | 0.3389 | 0.4153 | 0.6381 |

| 27 | 300 | 18 | 4.1298 | 0.0169 | 2.9772 | 0.1730 | 1.0055 | 0.7175 | 0.6736 | 0.9410 |

| 28 | 400 | 20 | 2.9982 | 0.0137 | 1.5503 | 0.2518 | 1.0811 | 0.5172 | 0.9517 | 0.5927 |

| 29 | 400 | 22 | 4.9691 | 0.0066 | 3.9364 | 0.1044 | 2.3033 | 0.3785 | 1.7905 | 0.5916 |

| 30 | 400 | 24 | 5.5949 | 0.0253 | 3.8896 | 0.2136 | 1.9027 | 0.5303 | 1.1764 | 0.8565 |

| 31 | 500 | 20 | 11.2545 | 0.0994 | 5.5249 | 0.4835 | 5.8899 | 0.6513 | 4.9769 | 0.6621 |

| 32 | 500 | 22 | 8.1808 | 0.0772 | 4.2320 | 0.3694 | 2.2938 | 0.7760 | 2.5739 | 0.8429 |

| 33 | 500 | 24 | 7.8940 | 0.1045 | 7.4504 | 0.1192 | 2.2318 | 0.8396 | 2.9733 | 0.7800 |

| 34 | 500 | 26 | 5.6274 | 0.0796 | 3.4978 | 0.2525 | 2.1434 | 0.5481 | 1.6391 | 0.6477 |

| MIN | 0.0015 | 0.0002 | 0.0016 | 0.0003 | 0.0012 | 0.0018 | 0.0016 | 0.0065 | ||

| MAX | 11.2545 | 0.1143 | 7.4504 | 0.4835 | 5.8899 | 0.8396 | 4.9769 | 0.9410 | ||

| Average | 2.0371 | 0.0220 | 1.4511 | 0.0879 | 0.8039 | 0.2957 | 0.6257 | 0.4520 | ||

| Std. Dev | 2.7143 | 0.0311 | 1.7685 | 0.1105 | 1.1331 | 0.2405 | 1.0322 | 0.2525 | ||

| HV | Number of Best | Number of Suboptimal | Number of Worst |

|---|---|---|---|

| INSGAII-PPO | 28 | 5 | 0 |

| NSGAII-PPO | 5 | 24 | 2 |

| NSGAII | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| MOPSO | 0 | 2 | 24 |

| IGD | Number of Best | Number of Suboptimal | Number of Worst |

|---|---|---|---|

| INSGAII-PPO | 27 | 6 | 0 |

| NSGAII-PPO | 4 | 26 | 1 |

| NSGAII | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| MOPSO | 1 | 0 | 30 |

| Case1 | Case2 | |||||

| Completion Time | Energy Consumption | Waiting Time | Completion Time | Energy Consumption | Waiting Time | |

| Max | 2925 | 60 | 2550 | 9350 | 224 | 9887 |

| Min | 2260 | 55 | 2253 | 6640 | 170 | 6202 |

| Proposed | 2300 | 57 | 2388 | 7345 | 170 | 6459 |

| TOPSIS | 2300 | 57 | 2388 | 7205 | 174 | 6671 |

| Weighted | 2260 | 58 | 2407 | 7205 | 174 | 6671 |

| Gap1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1.94% | 2.3% | 3.18% |

| Gap2 | −1.77% | 1.72% | 0.79% | −1.94% | 2.3% | 3.18% |

| Case3 | Case4 | |||||

| Completion Time | Energy Consumption | Waiting Time | Completion Time | Energy Consumption | Waiting Time | |

| Max | 5725 | 106 | 4646 | 4940 | 97 | 4285 |

| Min | 4345 | 83 | 3208 | 3730 | 84 | 3325 |

| Proposed | 4705 | 85 | 3396 | 4135 | 86 | 3475 |

| TOPSIS | 4500 | 89 | 3747 | 3900 | 91 | 3736 |

| Weighted | 4480 | 90 | 3709 | 3900 | 91 | 3736 |

| Gap1 | −4.56% | 4.49% | 9.37% | −6.03% | 5.5% | 6.99% |

| Gap2 | −5.02% | 5.56% | 8.44% | −6.03% | 5.5% | 6.99% |

| Completion Time | Energy Consumption | Waiting Time | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average1 | −3.13% | 3.07% | 4.89% |

| Average2 | −3.69% | 3.77% | 4.85% |

| Average | −3.41% | 3.42% | 4.87% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Zhao, F.; Feng, J.; Sun, S.; Lu, W.; Chen, S. Simulation and Optimization of Collaborative Scheduling of AGV and Yard Crane in U-Shaped Automated Terminal Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2344. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122344

Yang Y, Zhao F, Feng J, Sun S, Lu W, Chen S. Simulation and Optimization of Collaborative Scheduling of AGV and Yard Crane in U-Shaped Automated Terminal Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2344. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122344

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yongsheng, Feiteng Zhao, Junkai Feng, Shu Sun, Wenying Lu, and Shanghao Chen. 2025. "Simulation and Optimization of Collaborative Scheduling of AGV and Yard Crane in U-Shaped Automated Terminal Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2344. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122344

APA StyleYang, Y., Zhao, F., Feng, J., Sun, S., Lu, W., & Chen, S. (2025). Simulation and Optimization of Collaborative Scheduling of AGV and Yard Crane in U-Shaped Automated Terminal Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2344. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122344