Abstract

Rare earth elements and yttrium (REY) are emerging contaminants of concern due to their widespread use in modern technologies, persistence, and unknown ecological effects. This study presents the first assessment of REY in seawater and sediments of Pula Bay, Croatia, a semi-enclosed, industrialized coastal system. Surface seawater and sediment samples were analyzed using ICP-MS, following optimized preconcentration and digestion protocols. PAAS-normalized REY patterns and λ Polynomial Modelling identified natural and anthropogenic fractionation signatures. Dissolved ΣREE in seawater ranged from 17.6 to 45.9 ng L−1, with naturally elevated concentrations from continental runoff and evidence of anthropogenic Gd (up to 33%) linked to sewage outputs. Sediment ΣREE concentrations varied from 134.8 to 218.2 mg kg−1, with spatial variation reflecting terrigenous and anthropogenic inputs. Local MREEPAAS and HREEPAAS enrichment associated with industrial and municipal inputs distinguished anthropogenic contributions from the lithogenic background. While seawater remains largely unaffected, pollution and risk assessments indicate moderate to high sediment contamination by MREEs and HREEs, showing potential concern for benthic organisms near industrial and urban hotspots. These findings highlight the combined influence of natural and anthropogenic processes on REY distribution in coastal systems and underscore the need for further studies of potential REY effects in impacted coastal environments.

1. Introduction

The rare earth elements (REEs) are a group of 15 lanthanides (La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Pm, Sm, Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Yb, and Lu), along with Y and Sc. Yttrium and Sc are often included in the group because they tend to occur in the same ore deposits as the lanthanides and exhibit similar chemical properties. From the lanthanide group, Pm is the only one that is very scarce in nature as a radioactive element that has no naturally stable isotopes. The acronyms REY and YREE are frequently used for lanthanides and Y [1,2]. While Sc has a much lower ionic radius and differs much from other lanthanides, Y mimics the HREE, particularly Ho, because of the similar ionic radius, for which its geochemical cycling has often been studied [3]. Based on the similarities in electronic configurations, REE can be divided into light (LREE, from La to Pm), middle (MREE, from Sm to Gd), and heavy (HREE, from Tb to Lu) [4]. As they obey the Oddo–Harkins rule, their concentrations are often normalized in relation to some natural reference material [3,5], allowing intercomparison between studies and calculation of anomalies, which can be used to draw conclusions about the natural fractionation processes, as well as their anthropogenic sources. Among these, the anthropogenic Gd anomaly is of particular interest, arising from the widespread use of Gd-based contrast agents (GBCAs) in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) since the mid-1980s. These compounds are injected into patients, excreted via the kidneys into the wastewaters, and largely unaffected by conventional wastewater treatment, leading to positive Gd anomalies in receiving waters [4,6,7].

The REYs are characterized by magnetism, luminescence, and electrochemical activity, and, along with the platinum group elements and other technology-critical elements [8,9], their use is vast and includes industry, catalysis, alloying, green energy devices, electronic devices, medical applications, weapons, fertilizers, and others [10,11,12]. As a result, they are increasingly sourced and released from mine tailings, wastewater discharge, industrial effluents, solid waste deposits, and agricultural runoff, entering terrestrial and aquatic systems. The concentrations of REYs in certain parts of the environment and their effects on living organisms are relatively unexplored, largely due to analytical challenges and past lack of interest. Nevertheless, with their growing use in recent decades, the absence of data on toxicological mechanisms, and a lack of regulation, REYs are now considered emerging contaminants. Existing research shows that they can accumulate in aquatic organisms, with benthic species being most affected [13,14,15,16], and can have a harmful effect on both marine life and human health [17,18,19,20].

In this study, REYs were analyzed in seawater and sediments of the Pula Bay (Croatia), addressing the lack of data for this region. The Pula Bay hosts the largest city of the Istrian Peninsula, Pula, with a population of about 60,000. The main characteristic of the bay is its high level of industrialization. Among the major industrial facilities is the cement factory (founded in 1925), a key site in the production of special calcium aluminate cement under Cementos Molins, the world’s second-largest producer. The Uljanik shipyard (founded in 1856) is one of the four largest in Croatia, although it is currently operating at a reduced capacity. The bay also hosts two smaller shipyards, three marinas, a small military port, and a passenger terminal, all of which contribute to the diverse range of potential contaminants. Additionally, until 2015, the bay was the endpoint of a large wastewater drainage system of the city of Pula. Although a new treatment plant is functioning, releasing treated wastewater out of the bay, legacy contamination from decades of untreated effluents persists. Taken together, the cement factory, shipyard activities, and wastewater inputs represent plausible sources of anthropogenic REY through the release of industrial raw materials, processing residues, surface-treatment compounds, and effluents. Calcium aluminate cement production may represent a potential source of anthropogenic REY, as trace elements, including REYs, can be incorporated into aluminate phases from raw materials or industrial residues [21], and these elements can be released through cement leachates or runoff during production, use, or demolition. Shipyard activities may contribute to REY inputs in the bay, as modern shipbuilding relies on REY-containing materials, such as high-strength magnets, specialized coatings and alloys, and high-performance electronics as an integral part of naval ship construction [22], providing a plausible pathway for REY release through wear, abrasion, or runoff. Municipal wastewater represents a potential source of REYs to coastal systems, as they can enter wastewater streams from medical applications and household use and may be discharged into the environment via treated or untreated effluents [23,24,25]. Due to its semi-enclosed nature and a history of anthropogenic activity, including a combination of industrial emissions, shipyard activities, port operations, and urban runoff, the sediment in the harbour is a potentially abundant reservoir of pollutants and can act as their source in the water column [26]. Recent studies have documented elevated levels of trace elements in seawater [27] and sediment [26] from the area, confirming the bay’s status as a heavily impacted coastal system.

Given their recognition as emerging contaminants of concern, it is important to evaluate the status of REYs in coastal systems that are exposed to anthropogenic pressures. The Pula Bay, heavily impacted by industrial and urban activities, represents a particularly relevant site for such an assessment. Additionally, data on REY in the Adriatic Sea are very limited, and while a few studies report REY in sediments [28,29,30], no comprehensive data exist for seawater. This study provides the first dataset of REY concentrations in Adriatic seawater, investigates the natural geochemical controls and the influence of historical and ongoing anthropogenic inputs on REY distribution in the Pula Bay, and assesses the potential ecological risks associated with these elements for the coastal ecosystem.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Seawater Sampling and Sample Preparation

The analysis of REY in seawater was performed after the preconcentration of composite samples collected in August 2023, a dry season in Croatia. Ten sampling sites, nine along the bay’s shoreline and one at the end of the seawall, were selected to represent areas with minimal impact as well as sites influenced by specific anthropogenic sources, as illustrated in Figure 1, with their coastal proximity increasing the likelihood of detecting localized inputs. During a period of six days (144 h), samples were taken daily from the shore or a ship at 0.5–1 m below the surface, using a telescopic pole placed directly into FEP containers. No rainfall events occurred during the days of the sampling. Daily samples were filtered within an hour of sampling through 0.45 µm pore cellulose-nitrate membrane filters (Sartorius) using a N2 filtration apparatus. A mass of 30 g of each sample was taken to create a composite water sample for each sampling site, representing a time-averaged value. Although REY values are expected to be generally stable over short periods, this approach captures the typical seawater chemistry at each site, reducing the influence of isolated fluctuations, as our main interest is the general behaviour of REY and capturing potential steady anthropogenic inputs to the bay. The composite samples were acidified, UV-irradiated, and stored in a fridge until the preconcentration step.

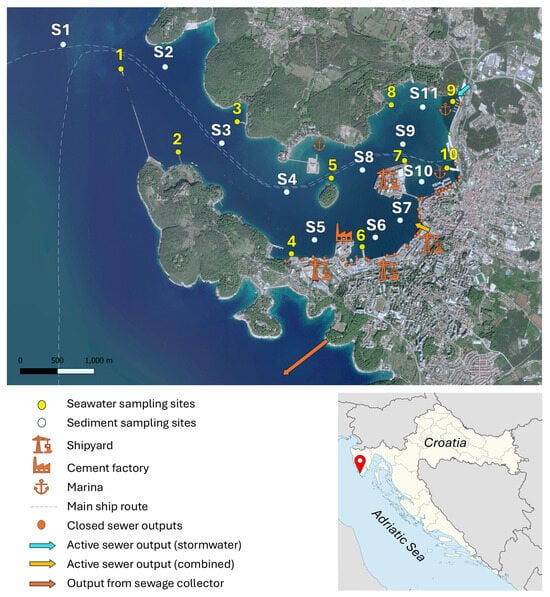

Figure 1.

Map of Pula Bay, with marked sampling sites for seawater (yellow; August 2023) and sediment samples (white; August 2022), along with indicated potential anthropogenic or natural influences.

Very low REY concentrations in seawater and chemically complex sample matrix, spectral interferences, and the lack of certified reference materials make their analyses challenging [31,32]. To overcome some of these issues, preconcentration by solid phase extraction (off-line and in-line) is commonly applied, with NOBIAS Chelate resins and the seaFAST system most frequently applied [33,34,35,36]. In this study, a customized laboratory protocol was developed on a home-made system for sample preconcentration on Nobias Chelate-PA1 resin. Our approach was designed to achieve efficient preconcentration with available resources, allowing parallel processing of two samples with an average preparation time of 1.5–2 h. The system consisted of a closed sample vessel (50 mL centrifuge vial, Sartorius), a commercially available column with an internal volume of 200 µL filled with Nobias Chelate-PA1 resin (seaFAST CF-N-0200, ESI—Elemental Scientific Inc., Omaha, NE, USA), a N2 pressure reservoir, and a capillary system. Under N2 pressure (purity 5.0), the sample from the vial was directed through the column into the receiving vial. An air filter was also installed to prevent possible contamination with particles from the N2 supply system. The preconcentration system was placed in a tabletop laminar flow cabinet (class 100) to avoid external contamination.

Two samples were preconcentrated in parallel on two identical systems. The average time required to prepare two samples was between 1.5 and 2 h, depending on the conditions in the column and the applied pressure. Two-way valves were used to reduce the gas pressure in the system so that the vials could be opened for the addition of solutions. The gas pressure during the preconcentration step was always constant (between 0.8 bar and 1.2 bar), but in some cases, a drop in flow rate was observed during the process due to partial clogging of the column frits. The liquid phase was moved through the system exclusively under N2 pressure. Other preconcentration systems most often use peristaltic pumps, and examples of flow under gravity can also be found in the literature [36,37,38]. The elution was carried out at a slightly lower pressure (0.6 bar to 0.8 bar) in order to reduce the flow, i.e., to extend the retention time. The used vials were washed with diluted HNO3 (10% v/v) (Rotipuran, Roth, Germany) and three times with MQ water before reuse. The pH value in the acidified composite samples after treatment with UV radiation was adjusted to 5.6 (±0.1) by adding an acetate buffer solution. In order to achieve the specified pH values, it was sufficient to add 4 mL of buffer to 40 mL of sample, while significantly larger volumes slightly increased the pH value to 5.7. The first cleaning of the system was carried out several times with methanol (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), MQ water, and diluted HNO3 (0.5 mol L−1). Although it was determined that the elution of all elements of interest was complete, between each sample passing, the system was additionally cleaned with 4 mL HNO3 (0.5 mol L−1) at 0.8 mL min−1. Then 4 mL of conditioning solution (pH of 5.4) was passed through at the same flow rate. The conditioning solution was prepared by mixing 200 mL of MQ water, 50 µL of HNO3, and 2 mL of 4 mol L−1 CH3COONH4 buffer. The conditioning solution adjusted the pH of the resin to about 5.4 by removing any residual acid and converted the resin to the NH4+ form [38]. Preconcentration of REY on the resin was then performed by passing a mixture of 40 mL of sample and 4 mL of acetic buffer at a flow rate of 0.6 mL min−1 to 0.8 mL min−1. Although, at a pH value of about 5.5, the accumulation of alkali and alkaline earth elements is minimal, an additional 5 mL of conditioning solution was passed through the resin before acid elution in order to remove residual ions from the resin. All eluates obtained until the final step were discarded. The final step of preconcentration was the elution of REY, by passing 4 mL of 0.5 mol L−1 HNO3 through the column at a slightly lower flow rate (~0.5 mL min−1). All reagents were passed through the preconcentration column in the same direction in order to reduce the disturbance of the system, avoid the possibility of contamination, and shorten the time of the process. The eluate volume of 4 mL was sufficient for the analysis using ICP-MS, and the ratio of the initial sample volume to the eluate volume resulted in a concentration factor of 10.

2.2. Sediment Sampling and Sample Preparation

Sediment sampling was carried out in August 2022 at ten sites inside the bay and at one site outside the bay (Figure 1). Sampling sites were arranged to cover the expected different zones of sedimentation, runoff, and anthropogenic impact. Water column depths at the sediment sampling sites are provided in Table S1 in the Supporting Information. It should be noted that, although the seawater and sediment sampling campaigns were conducted one year apart and at different sampling locations, these spatial and temporal offsets do not affect the overall geochemical interpretation, as the datasets are complementary and not intended for direct comparison. Both samplings were carried out during the same summer period under comparable meteorological and anthropogenic conditions (i.e., no rainfall, similar temperatures, and comparable industrial and maritime activity).

Sediment cores were sampled with a gravity corer (Uwitec), descending under the influence of gravity. A surface layer of 5 cm thickness was stored in a clean, plastic bag and lyophilized at −50 °C. Microwave digestion was used for further preparation: about 0.15 g of each sediment sample was weighed in clean vessels for microwave digestion, and 10 mL of HNO3 (50% v/v), 2 mL of concentrated HF (Merck), and 2 mL of H2O2 (Merck) were added. After each addition, the sample was left for possible reactions to complete. Samples were then digested at 1200 W (19 °C min−1 to 190 °C and then 12 min at 190 °C). After cooling, 10 mL of H3BO3 solution (4% w/v) was added to each vessel. The vessels were then returned to the microwave oven and a second digestion at 1200 W was performed (17 °C min−1 to 170 °C, 12 min at 170 °C). After cooling, another 10 mL of H3BO3 solution (w = 4%) was added to react with possibly unreacted HF. The contents of the vessels were filtered through 0.45 µm pore size filter paper (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany), with several rinses with MQ. When necessary, the flasks were topped up with MQ water. Each sample was digested in at least two parallels (duplicates), and at least two blanks and samples of reference material of marine sediment NCS DC 75301 (also known as GBW 07314; China National Analysis Center for Iron and Steel) were also digested. Each sample was diluted by a factor of 20 before analysis.

2.3. REY Analyses

Lanthanides and Y were analyzed both in seawater samples and sediment samples at the Teaching Institute of Public Health of the Region of Istria using ICP-MS PlasmaQuant MS Q (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany) equipped with a single quadrupole, ion optics system, and CRC with He and H2 gases. Measurements were automated using an ASX60 autosampler (Teledyne, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA). External and internal standard (In, 10 µg L−1) methods were used. Quality control included the use of SLRS-6 (NRCC) for seawater and NCS DC 75301 (i.e., GBW 07314) for sediment analyses.

Calibration standards (Analytika, Prague, Czech Republic and CPAChem, Bogomilovo, Bulgaria) and a system optimization solution (Reagecon, Shannon, Ireland) were used for ICP-MS optimization. A glass, concentric nebulizer (MicroMist type, 0.4 mL min−1), a Scott spray chamber (3 °C), a Fassel-type plasma generator, Ni cones, and peak hopping mode were used. Information on possible interferences was taken from the literature [32]. Isobaric interferences were eliminated mathematically (an option in the instrument control programme), while He was used as the collision gas to eliminate polyatomic interferences (Tables S2 and S3). Limits of detection (LODs) were calculated as triple the standard deviation of the blank signal (n = 9) (Tables S2 and S3). In some cases, the blank signal was not measurable (Gd, Er, Tm, and Yb in seawater), so LOD was not calculated. In sediment samples, LOD was calculated, taking into account the typical mass of 0.15 g and volume of 50 mL. During the analysis, the internal standard recoveries ranged from 80% to 100%. In the absence of certified values for REY in CRMs (only indicative values are officially provided), we compare our measurements to published values in SLRS-6 from Yeghicheyan et al. (2019) [39] and Ebeling et al. (2022) [40] determined using direct analysis, and in NCS DC 75301 from Fiket et al. (2017) [41], determined after total digestion. All elements agreed with the reference values from these sources within their respective uncertainties, with recoveries of 84% and 110% (Tables S2 and S3). The REY concentrations in 10× preconcentrated samples were one to three orders of magnitude higher than calculated LODs, except for Eu, which approached the method LOD. Additionally, PAAS-normalized seawater REY patterns showed inconsistent Eu anomalies, with some samples displaying negative and others positive anomalies (Figure S1), although the averaged REYPAAS pattern is consistent with the expected absence of the Eu anomaly in seawater of Pula Bay. Namely, Eu redox fractionation that would be reflected as an anomaly in the shale-normalized pattern is limited to strongly reducing, high-temperature conditions where Eu3+ can be reduced to Eu2+, but such conditions are absent in the fully oxic, low-temperature surface waters of Pula Bay, preventing any redox-driven Eu anomalies [42]. For the given reasons, the Eu data in seawater samples were considered unreliable, and EuPAAS anomalies in seawater samples are not discussed further.

2.4. Data Interpretation

Evaluation of REY distribution was carried out using the PAAS reference system from 2012 [43]. Other normalization schemes, including North American Shale Composites (NASC) [44], European Shale (EUS) [45], and Upper Continental Crust (UCC) [46] were also evaluated but the differences relative to PAAS in terms of overall pattern shape were negligible. Anomalies from the normalized pattern are most often estimated either by using values of neighbouring elements in the periodic table or by approximating the series as a geometric progression (extrapolation or interpolation) [5], while some approaches also apply model-based fitting methods that better capture complex patterns [47,48,49,50]. Here, we used the latter approach based on λ Polynomial Modelling (λPM). Ernst et al. (2025) [48] demonstrated that λPM can reliably reconstruct missing REEs and quantify anomalies within the analytical uncertainty of modern ICP-MS (<10%) based on verification with large reference datasets, confirming its suitability for incomplete REE data or imperfect measurements, allowing for accurate calculations of anomalies. The procedure was implemented in R using built-in functions (Supplemental Text S1). The REYPAAS concentrations were first log-transformed to normalize the data and stabilize variance and subsequently fitted as a function of ionic radius using a third-degree orthogonal polynomial. Anomalous elements were excluded from the fit. From this fit, λ-parameters were extracted, providing a compact representation of the REYPAAS pattern for each sample (Tables S4 and S5). Based on the fitted coefficients, complete REYPAAS patterns were reconstructed, including elements not originally used in the fitting procedure. The resulting λ-parameters represent distinct components of the REY pattern: λ0 represents normalized average REY content (vertical offset relative to PAAS), λ1 the slope (enrichment or depletion of HREE relative to LREE), λ2 the curvature (MREE enrichment or depletion), and λ3 higher-order residual deviations without statistical significance. Reconstruction of the REYPAAS curve was achieved by multiplying the λ-parameters by their respective orthogonal polynomials, thereby generating a modelled background trend (Figures S1 and S2).

Specific anomalies were calculated as a ratio of measured PAAS-normalized values and values predicted by the λPM model (e.g., Ce/Ce*), with values below one indicating a negative anomaly and values above one indicating a positive anomaly from the REYPAAS pattern. In addition to anomalies, other geochemical indicators considered include the ratio of HREE/LREE, calculated as the ratio of (TmPAAS + YbPAAS + LuPAAS)/(LaPAAS + PrPAAS + NdPAAS) [51], the molar ratio of Y/Ho, and pollution and ecological risk indices (the geo-accumulation index (Igeo) [52], the contamination factor (CF) [53], and the pollution load index (PLI) [54], presented in Section 3.3 and detailed in Supplemental Text S2). The ratio of HLREE/LREE correlated well with fitted parameter λ2 (r = 0.97, p < 0.001).

Data analysis was performed using R (v. 4.2.1) in RStudio (v. 2022.07.2) [55], and figures were created using QGIS (v. 3.36-Maidenhead) [56] (Figure 1), RStudio (Figure 3 and Figures S1–S3), and Ocean Data View software (v. 5.8.2) [57] with coastline shapefile sourced from European Environment Agency (2017) [58] and using DIVA gridding (Figures 2 and 4).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Drivers of Dissolved REY Distribution in Surface Waters

3.1.1. Spatial Distribution of Dissolved REY

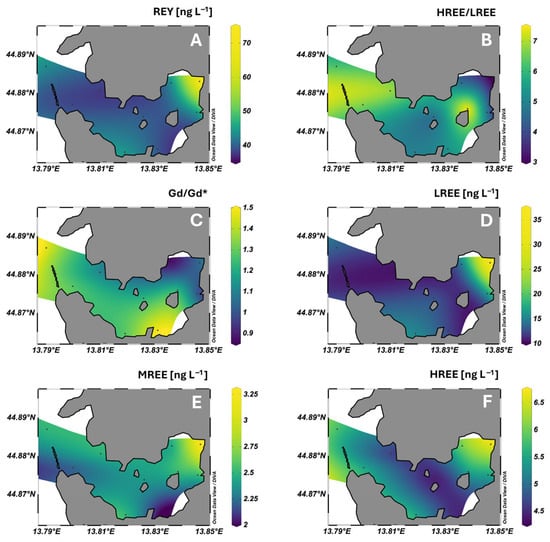

In surface waters of Pula Bay, the highest dissolved REY levels were measured at site 9, directly influenced by freshwater inflow from the stormwater channel (Figure 2A), where total dissolved REE (excluding Y) reached 45.9 ng L−1. In contrast, concentrations across the other sites were markedly lower and exhibited little spatial variability, falling within a relatively narrow range of 17.6–24.3 ng L−1. This pattern indicates that REY distribution in surface seawater of Pula Bay is primarily governed by localized inputs, with freshwater discharge acting as the dominant source. These observations are consistent with other studies, which found freshwater discharge to be the primary source of REY to coastal systems, although wastewater effluents often contribute [24,25,59]. Until 2015, 42 sewage outlets were flowing directly into the Pula Bay. After construction of the coastal collector, most in-bay outlets had been closed or remediated, leaving one combined sewer discharge within the bay, still present at the time of the samplings, near site 6 (Figure 1). The main collector outlet is located south of the bay, and northward currents may transport REY signals along the southern shoreline, contributing to slightly elevated values at site 1, outside the bay. However, the unexpectedly low concentrations observed at site 6, closest to the remaining active sewage outfall within the bay, suggest that this source currently plays a limited role in in-bay REY content and may even exert a local dilution effect on all REE subgroups, especially dissolved MREE (Figure 2D–F).

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of total dissolved REY concentrations (A), HREE/LREE ratios (B), Gd/Gd* anomalies relative to PAAS (C), and of LREE (La–Nd), MREE (Sm–Gd), and HREE (Tb–Lu) concentrations (D–F, respectively) in surface seawater of Pula Bay.

To our knowledge, these data represent the first report of REY concentrations in Adriatic seawater, and, excluding site 9, which was strongly influenced by freshwater inflow, they seem to agree well with the data from Mediterranean Sea [60,61] (Table 1) and are comparable to those reported for surface waters in the coastal ocean, including the North Atlantic [51,62], East China Sea [63], Indian Ocean [64], and Arctic Ocean [65]. Such agreement is striking given the semi-enclosed, industrial, and urbanized character of Pula Bay, where higher contaminant burdens would normally be expected. Studies from highly urbanized coastal systems report substantially higher REE levels. For instance, San Francisco Bay exhibits concentrations up to 188 ng L−1 in its southern reach, a consequence of long water residence times and the accumulation of effluents from medical, research, and high-technology industries utilizing REE [66], whereas plume and adjacent coastal waters contained only 26.8 and 5.9 ng L−1, respectively [33]. Similarly, offshore waters at the end of the Loire River estuary display REE concentrations 2–3 times higher than those measured in Pula Bay [67]. While elevated levels in the Loire estuary were largely attributed to geogenic inputs, the occurrence of positive Gd anomalies indicated a substantial anthropogenic contribution, with estimates suggesting 60% anthropogenic Gd within the estuary and 13% at offshore stations, demonstrating contamination transport to the adjacent Atlantic Ocean. The Gulf of California provides interesting example, where REE concentrations spanned an order of magnitude, from 3.5 to 116.9 ng L−1 [68]. The Bay of La Paz represented an exception, with very low levels linked to limited freshwater supply and weak anthropogenic forcing, while at other sites, values were three- to six-fold higher than in Pula Bay, attributable to both geogenic inputs and effluents from agriculture, aquaculture, urban wastewater, and industrial activities.

Table 1.

Comparison of REY concentration in seawater of Pula Bay (* this study) with reported values from other marine systems (minimum–maximum concentration (mean value) or mean value ± standard deviation, depending on availability). All concentrations are in ng L−1.

3.1.2. Geochemical Signatures and Anomalies

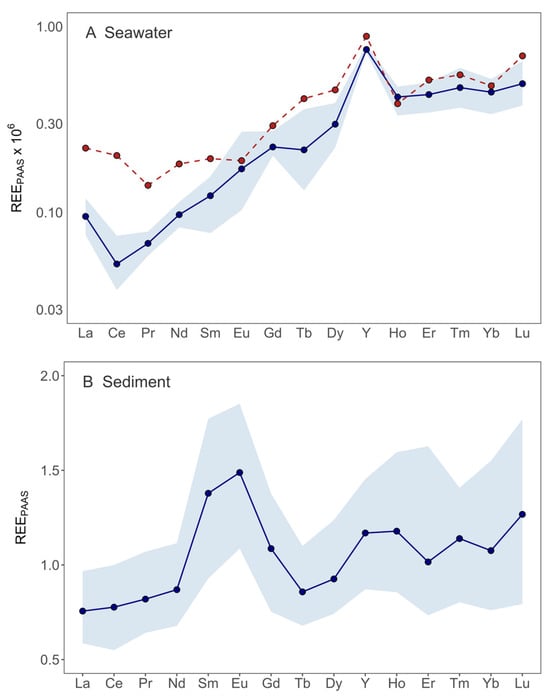

The shale-normalized REYPAAS pattern (Figure 3A) generally displayed an increase from LREE toward HREE, consistent with typical seawater signatures. However, the pattern at station 9 diverged from sites in the rest of the bay, with a markedly lower HREE/LREE ratio of 3.2 (Table 2). This signature reflects the influence of freshwater input from the nearby stormwater drainage (Figure 1), which delivers variable volumes of runoff during rainfall events, as well as contributions from more continuous sources, such as groundwater seepage and urban discharge. These flows pass through the stormwater sewer channel near site 9 and deliver soil material derived from terra rossa, a cover known for its LREE enrichment.

Figure 3.

REY concentrations normalized to PAAS in seawater (A) and sediment (B) of Pula Bay (note the log scale in (A)). Red datapoints and red dashed lines represent concentration at sampling site 9 (A), whereas blue datapoints and blue lines represent average REY concentrations across all other sampling sites, with the shaded envelope showing the minimum–maximum range.

Table 2.

Geochemical characterization of REY patterns in seawater (A) and sediment (B) of Pula Bay: HREE/LREE ratio, observed anomalies from PAAS pattern (X/X*) and Y/Ho molar ratio. For seawater, anthropogenic Gd concentration (Gdant) and anthropogenic Gd proportion (w(Gdant)) are additionally shown.

The influence of terra rossa in shaping local water chemistry has also been observed in Croatian tap waters from karstic regions, where it contributes characteristic LREE-enriched signatures [69]. The geochemical fingerprint at station 9 is further distinguished by the lack of a negative Ce anomaly, normally expected for oxic seawater. In standard natural conditions, Ce is the only REY that undergoes redox transformations, with Ce3+ oxidizing to Ce4+ in oxic waters, which is then readily scavenged by Fe/Mn oxyhydroxides into colloidal or particulate phases. The absence of such a feature at this site suggests that colloidal material is abundant and not yet removed from the water column. Farther inside the bay, colloids are more efficiently flocculated, leaving the dissolved fraction with the characteristic seawater-type pattern: higher LREE-depletion and a distinct Ce anomaly.

Other locations in Pula Bay display REY patterns that align with those of open marine waters [51,61,63]. Ratios of HREE/LREE (4.6–6.9; Table 2) generally increase from the inner to the outer bay (Figure 2B), reflecting the greater stability of HREE carbonate complexes in seawater. LREEs, in contrast, are more often present as free ions and are preferentially adsorbed onto particles, leading to their relative depletion [70]. An exception with unusually strong enrichment in HREE (HREE/LREE of 7.5) was observed at site 7, located closest to the coast in an active shipyard area. The proximity to industrial activity suggests that anthropogenic inputs contributed to this signature. Processes such as welding or the use of REY-containing alloys in shipyard operations may release these elements into the surrounding water [71,72].

Across the bay, the most pronounced anomalies were those of Y and Ce (Table 2). The negative Ce anomaly progressively strengthened from the inner to the outer bay from 1.0 to 0.5, a value typical for coastal seawater [40,51,66], in line with enhanced removal of particle-reactive Ce4+. The positive Y anomaly, one of the most distinctive features of seawater REY pattern, persisted throughout and is also reflected as super-chondritic Y/Ho molar ratios (Table 2), reflecting the preferential retention of Y in the dissolved phase. Lanthanum enrichment was less straightforward to interpret. While a positive La anomaly is widely reported in seawater, our dataset does not provide sufficient confidence for quantification. Nonetheless, positive La anomalies are considered a normal feature of seawater, reflecting the weaker removal and greater release of La in the salinity gradient relative to other LREE [70].

3.1.3. Gadolinium Anomalies and Anthropogenic Tracing

Several sites exhibited positive Gd anomalies (Gd/Gd* > 1; Table 2), with the strongest signals at sites 1 and 6 (Figure 2C), reflecting inputs from urban wastewater. Anthropogenic Gd concentration (Gdant) was calculated as the difference between measured values normalized to PAAS and values predicted by the λPM model multiplied by the Gd concentration in PAAS (6.043 mg L−1) to remove the effect of normalization. The proportion of Gdant is expressed as the percentage of Gdant relative to the total measured Gd. Samples with Gd/Gd* > 1.4 at sites 1 and 6 are indicative of Gdant from wastewater, accounting for 32–33% of total Gd (Table 2). Site 1 records the influence of the main coastal collector located outside the bay and shows the highest absolute Gdant concentration. An in-bay sewer outlet, despite diluting overall REY concentrations, also shows a distinct Gd fingerprint associated with GBCA discharge, with site 6 displaying the highest proportion of Gdant relative to total Gd. From the outlet at site 6, the Gd anomaly extends toward sites 5 and 7 and along the southern shoreline toward sites 4 and 2. The long-term stability of GBCAs in marine environments is not fully understood, and their behaviour after discharge remains an open question [11]. Laboratory studies and field evidence suggest that linear GBCAs are far more susceptible to dissociation [73], while macrocyclic GBCAs are expected to be relatively stable. While linear agents are largely phased out, the behaviour of macrocyclic GBCAs in natural seawater, although considered more stable, remains largely uncharacterized, and their long-term fate in natural seawater is uncertain.

Although Gd anomalies clearly trace wastewater inputs in Pula Bay, wastewaters do not significantly alter overall dissolved REY concentrations in the surface waters. Nevertheless, the persistence of Gd anomalies provides a tracer for other wastewater-derived substances, such as pharmaceuticals, cosmetic products, and endocrine disruptors, and thus offers insight into contaminant transport and behaviour in Pula Bay [74,75,76]. Importantly, other studies have shown that industrial and nautical activities in Pula Bay also contribute to seawater contamination with elevated Cu, Pb, and Zn concentrations in areas influenced by these activities, up to 8.5 times higher than reference sites outside the bay [27]. Taken together, these findings highlight the spatial variability of contamination in Pula Bay, shaped by the combined effects of freshwater inputs, wastewater discharges, and localized industrial and urban activities.

3.2. REY Signatures and Controlling Factors in Sediments

3.2.1. Concentrations and Regional Comparison

Total REE concentration in sediments ranged from 134.8 mg kg−1 at site S2 to 218.2 mg kg−1 at S10 (mean of 171.8 mg kg−1) (without Y), with the predominance of LREE (79–84%). The most abundant element was Ce (48.5–88.2 mg kg−1), followed by La, Nd and Y (23.8–43.1 mg kg−1). The concentrations of MREE and HREE together were on average 31.3 mg kg−1. To place the Pula Bay surface sediment data in a regional context, we compare ΣREE and PAAS-normalized patterns to published Istrian terrestrial and other sediment values along the Adriatic coast (Table 3). The geomorphology of the Pula Bay region is underlain by the Istrian carbonate plateau, composed chiefly of limestones and dolomites and extensively mantled by terra rossa. Terra rossa soils in the region exhibit ΣREE on the order of 200–500 mg kg−1 (mean of 323 mg kg−1) and show characteristic enrichment in LREEUCC along with positive CeUCC anomalies formed under oxidizing conditions [77]. In contrast, the underlain, cretaceous paleosols, formed under reducing conditions, contain almost two times lower REE concentrations that are almost entirely confined in the residual fraction and display a different REE signature, with HREEUCC enrichment and positive CeUCC and EuUCC anomalies [77]. The nearby Rijeka harbour has sedimentary REE content of 58 mg kg−1 (mean value) [30]; however, this study did not use total digestion, but aqua regia, so it is not directly comparable due to REE’s abundance in residual fraction [77]. Sediments from other karstic Adriatic marine systems (Telašćica Bay and Zrmanja River estuary) display ΣREY values much lower than soils, showing common natural dilution of REY signals in carbonate-rich marine sediments, with REYNASC distributions reflecting the combined influence of carbonate bedrock and contributions from terrestrial fine material [28,29]. In the pristine Telašćica Bay, surface sediments have ΣREY concentrations of 56–85 mg kg−1 (mean of 74 mg kg−1) [29], with an HREE/LREEPAAS ratio of 0.5. Surface sediments from the Zrmanja estuary yielded ΣREE concentrations in the range of 30–181 mg kg−1 (mean of 110 mg kg−1) [28], values overlapping with both Telašćica Bay and Pula Bay. In the Zrmanja estuarine system [28], sediment REENASC patterns closely mirrored those of nearby soils (terra rossa and local bauxites), underscoring the strong imprint of land-derived material. The highest concentrations occurred near the former alumina plant, indicating persistent anthropogenic additions of REE-rich material to the estuary. A general increase in ΣREE was observed in the seaward direction, coinciding with the transition to finer-grained, clay- and silt-rich deposits in deeper parts of the estuary below the wave base. This grain-size control also influenced fractionation, as LREE/HREENASC ratios showed that riverine sediments most closely resembled the soil signature, while estuarine and marine sediments exhibited progressively stronger LREENASC enrichment, consistent with the preferential binding of LREEs to fine clays.

Table 3.

Comparison of Pula Bay sediment REY content (* this study) with reported values from surface sediments in other relevant marine systems (minimum–maximum concentration (and mean value) or mean value ± standard deviation, depending on availability). All concentrations are in mg kg−1.

Based on the regional framework, for Pula Bay, it would, thus, be expected for surface sediments to exhibit lower REE inventories compared to surrounding soils, modulated by local carbonate content, grain size, and terrigenous input, and potentially discernible REYPAAS patterns in areas impacted by runoff or anthropogenic inputs. Based on known lithologic and geomorphologic features, Pula Bay sediments may contain a substantial carbonate fraction with possible inputs of fine-grained siliciclastics (e.g., clay minerals and Fe oxides) derived from terra rossa soil and bauxite used in cement production. Generally, low relief and the absence of permanent surface streams suggest limited fluvial supply, so sediment delivery to the bay is controlled by diffuse infiltration and episodic runoff during intense rainfall. Quantitative confirmation of these inferences requires targeted sedimentological and geochemical analyses to determine mineralogical proportions and geochemical signatures, although our results provide some insights.

3.2.2. Geochemical Patterns, Spatial Distribution, and Natural Controls

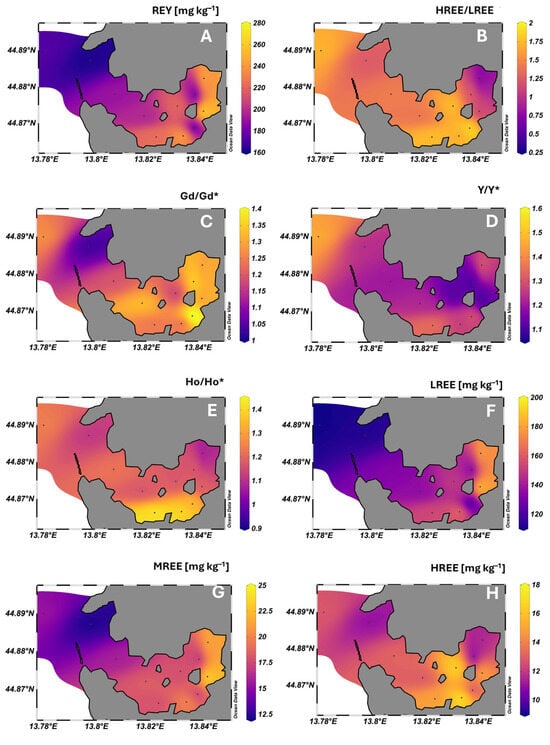

In contrast to local lithology, normalized REY patterns were generally characterized by enrichment of HREEPAAS (Figure 3B; Table 2). The highest HREE/LREEPAAS ratios were observed at sites S1 and S5–S7, while the lowest ratios occurred at S10 and S11, in the most inner bay (Figure 4B, Table 2). Notably, sites S10 and S11, more influenced by runoff and freshwater inputs, exhibited ∑REE concentrations within the range reported for terra rossa soils in the region, indicating the dominance of terrigenous contributions with higher LREE contributions, while other sites had 15–45% lower ∑REE content (Figure 4A). No CePAAS anomaly was detected in our sediment samples, reflecting conditions that were insufficiently oxidizing or reducing to induce measurable CePAAS fractionation. Under oxidizing conditions, Ce, as Ce4+, is preferentially retained in sediments, promoting relative enrichment and positive CePAAS anomalies, whereas under reducing conditions, Ce, as the more soluble Ce3+, can be released from Fe/Mn oxides, leading to negative anomalies [81]. Normalized REY patterns, however, displayed pronounced positive anomalies of MREEs (Eu/Eu* ≈ 1.8, Sm/Sm* ≈ 1.6, Gd/Gd* ≈ 1.3), followed by YPAAS and HoPAAS (Y/Y*, Ho/Ho* ≈ 1.2) (Table 2). Natural enrichment of MREEN has been linked to phosphate or accessory mineral hosts (e.g., xenotime, monazite, resistant phosphates), authigenic or biogenic phosphate precipitation in the water column or at the sediment–water interface, and scavenging onto Fe-Mn oxyhydroxides or organic particles, as well as extensive low-temperature recrystallization of sedimentary minerals [4,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89]. This pattern in Pula Bay sediments may, therefore, be related to in situ geological and diagenetic processes, although, given the setting, anthropogenic contributions are highly plausible.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of total dissolved REY concentrations (A), HREE/LREE ratios (B), Gd/Gd*, Y/Y*, and Ho/Ho* anomalies relative to PAAS (C–E, respectively) (Sm/Sm* and Eu/Eu* exhibited a distribution similar to Gd/Gd*), and of LREE (La–Nd), MREE (Sm–Gd), and HREE (Tb–Lu) concentrations (F–H, respectively) in surface sediments of Pula Bay.

No significant correlations between Co, Fe, Mn, Ni, or Pb and bulk or individual REY or HREE/LREE ratio were found, indicating that REY distribution in surface sediments is largely independent of these common redox-sensitive and particle-reactive lithogenic trace elements and may instead reflect selective mineralogical sources or site-specific anthropogenic inputs (shipyard, cement factory, wastewater). While REYPAAS enrichment patterns and anomalies are not simply controlled by bulk Fe-Mn oxyhydroxide associations or general terrigenous inputs, other natural controls may arise from phosphate minerals and organic matter, which preferentially incorporate the MREE and Y [84,85,88,89]. Comparable MREE and Y enrichment has been attributed to syn-depositional adsorption processes in phosphatic sediments, with enrichment modulated by grain size, depositional setting, and organic matter decomposition [88]. In Pula Bay, however, the Y/Ho molar ratios (41–57; Table 2) were comparable to shales and UCC (47–51) and fall well below seawater samples (85–105), suggesting minimal authigenic contribution. The presence of the HoPAAS anomaly suggests its anthropogenic inputs, which could obscure potential authigenic signatures by artificially lowering the Y/Ho ratio, or both Y and Ho may be anthropogenically enriched, in which case the observed ratios may largely reflect external inputs. While distinguishing between these scenarios requires additional constraints, the data clearly indicate that anthropogenic contributions cannot be excluded in interpreting Y/Ho ratios.

3.2.3. Anthropogenic Influences

Pula Bay is one of the most heavily impacted sites along the Croatian coast. Although partial remediation has been implemented since 2015, including the closure of a large number of untreated sewage outlets, some discharge into the bay was still present at the time of the sampling; shipyard activity has only partially declined; and while the 2025 permit amendment was initiated for the Calucem cement plant, no measures have been taken. Therefore, persistent anthropogenic pressures are highly likely to contribute REY to bay sediments. Uljanik Shipyard may enrich specific REYs through specialized alloys, coatings, magnets, and phosphors used in shipbuilding and electronic equipment [22], while the cement factory may supply REY from alumina-rich raw materials [21], and additional, though likely minor, inputs from marinas and port facilities are also possible [10,71,72,90,91]. The historical sewage discharges may represent a significant source, with active input potentially adding additional REY to the bay [7,24,25,59,66]. This interpretation is supported by recent studies of seawater and sediments in Pula Bay. Besides the specific increase in dissolved Cu, Pb, and Zn concentrations in seawater within the bay [27], sediment analyses revealed that heavy metal concentrations in Pula Bay are significantly higher than in pristine Adriatic sediments [26], with Hg exceeding effect range median (ERM) values even at relatively unimpacted pelagic sites. Other metals, including Ag, Cu, Pb, and Zn, were also elevated in sediments, highlighting anthropogenic contributions via industrial and wastewater effluents. The accumulation of Ag and Pb in marine sediments is a robust indicator of anthropogenic perturbation via sewage and wastewater effluent disposal, while Cu, Pb, and Zn constitute the “triad” of metals most frequently associated with human-induced pollution [26].

The highest HREE/LREEPAAS ratios were observed at sites influenced by outer and inner sewer outputs, the shipyard and the cement factory (Figure 4B). The same can be observed for the spatial distribution of individual anomalies (Figure 4C–E). This pattern indicates that their relative enrichment, compared to other REEs, is associated with both industrial activity and municipal effluents, consistent with other similar settings [2,79]. At the same time, total REY concentrations (including all subgroups, LREE, MREE, and HREE; Figure 4F–H) were comparably lower at the inner-bay sewer outlet, reflecting its overall diluting effect on sediments, as was also observed for surface seawater. Yet, despite this dilution, municipal sewage contributes to the REY composition of sediments, reflecting the input of MREE-enriched particulates, together with dissolved medical Gd found in the dissolved water fraction.

Anthropogenic enrichment patterns of specific REYPAAS similar to Pula Bay have been documented elsewhere. For example, SmPAAS to GdPAAS maxima was observed in Tagus estuary (Portugal) in fine grain sediments near Lisbon’s wastewater treatment plants, as well as in contaminated sediments collected in the harbour of an inactive chemical-industrial complex (pyrite roast plant, chemical plant, and phosphorous fertilizer industries), with the latter also showing major YPAAS anomaly and significant HREEPAAS enrichment [2], similar to Pula Bay. Although less pronounced, MREENASC enrichment and LREENASC depletion were also reported in the Odiel estuary (SW Spain), heavily impacted by acid mine drainage and industrial pollution, including emissions from pyrite roasting, copper smelting, fertilizer production, and petrochemical industries [78]. An anthropogenic origin of Sm, Eu, and Gd was also found in sediments from the Oualidia lagoon, Morocco, affected by urban and touristic activities as well as a nearby phosphate fertilizer-producing facility, with the estimated high ecological risk of these elements on the study area [79]. Another study on coastal sediments along the Egyptian Mediterranean Sea reported shale (PAAS, NAAS) and chondrite normalized patterns with prominent Sm and Eu anomaly, estimating 13% of Sm and 36% of Eu, to be of anthropogenic origin and 48% and 20%, respectively, of mixed geogenic and anthropogenic origin [80]. In comparison with these systems (Table 3), MREE and HREE concentrations in Pula Bay are lower than in Oualidia but are up to 110% higher than in the Odiel estuary and up to 180% higher than in the Tagus estuary, in which their enrichments are strongly affected by both wastewater and industrial discharges, with the largest differences between Pula and Tagus seen for Ho, Tm, and Lu.

3.3. Pollution and Ecological Risk Assessment

In order to quantify the extent of REY pollution in Pula Bay, sediments from Telašćica Bay on Dugi Otok were used as a geochemically analogous reference site [29]. Both locations belong to the Dinaridic carbonate system, characterized by Mesozoic limestones and dolomites, widespread karstification, and residual terra rossa soils, resulting in comparable baseline geochemical signatures dominated by carbonates. Telašćica Bay is situated within a protected nature park and is minimally impacted by anthropogenic activities, with no industry, ports, or urban discharges. While local hydrodynamic and sedimentation conditions may differ, this area as a reference provides a pristine carbonate-rich baseline that reflects natural, unpolluted conditions. It should be noted, however, that Pula Bay may naturally exhibit slightly higher overall REY concentrations than Telašćica, owing to potentially lower relative carbonate content, warranting caution when interpreting pollution indices. Nevertheless, using this reference allows for the identification of deviations from natural conditions that are likely attributable to anthropogenic influence. Sediment contamination was evaluated using several indices, including the geo-accumulation index (Igeo) according to Müller (1969) [52], the contamination factor (CF) according to Håkanson (1980) [53], and the pollution load index (PLI) introduced by Tomlinson et al. (1980) [54], as detailed in Text S2. Based on these indices, contamination can be classified into six categories: 1—no pollution, 2—mild, 3—moderate, 4—moderate to high, 5—high, and 6—very high pollution (Text S2). Our results pointed to mild pollution (category 2) for LREE and Tb and moderate to high pollution (categories 3–4) for most of MREE and HREE, in the order Yb > Ho > Lu ≈ Tm ≈ Er ≈ Y > Dy > Sm > Eu ≈ Gd > Tb > Ce > La ≈ Nd > Pr, with the highest contamination at industrially influenced sites (Table 4). Considering all REYs collectively, the PLI indicated overall moderate to high pollution (category 4), and high pollution (category 5) at specific sites (S5, S6, S8, and S10) located in the shipyard and in close proximity to the cement factory and in the bay sewer outlet. At the same sites, a previous study reported strong sediment pollution by other metals, including Hg, Pb, Zn, Cu, Ag, Ni, As, Cr, and Cd, respectively [26]. As already noted, Hg exceeded ERM (the concentration above which significant adverse effects on biota are expected) at all sites, while Pb and Zn exceeded the ERM at locations coinciding with those showing high REY pollution. These patterns were reflected also in seawater quality reported in a recent study [27], where, based on proposed DGT environmental quality standards and international guideline thresholds, several metals exceeded pollution indices, highlighting risks to marine ecosystems and human health under established protection criteria.

Table 4.

Geo-accumulation index (Igeo) and ecological risk factor (ER) for individual REY and overall pollution load index (PLI) and potential ecological risk index (PRI) in surface sediments of Pula Bay. Results are presented for each sampling site, with the last column showing the mean value ± standard deviation.

As they are mostly new contaminants, at present, there are no established environmental quality thresholds or regulatory guidelines for REYs, and consequently, their ecological risks remain poorly constrained. This lack of reference values highlights the need for alternative approaches, and the potential ecological risk index method has been increasingly applied to assess the possible effects of REY pollution [79,92,93]. Here, we adopted the approach proposed by Chen et al. (2020) [94] to calculate REY toxicity indices in Pula Bay sediments (Text S2). The approach is based on two principles: (i) REYs tend to coexist due to their similar chemical properties, and (ii) their toxicity is determined by elemental abundance and release potential. The ecological risk factor (ER) is calculated for each element, considering its toxic potential and water sensitivity, while the overall potential risk index (PRI) is defined as the sum of the ER values for all REYs collectively. The results showed that Lu posed the highest ecological risk, with ER values ranging from 34 up to 152, corresponding to the high risk level category (Table 4). It should be noted that elevated ER values for Lu primarily reflect the relatively high toxicity coefficient (Tr = 20) assigned to this element in Chen et al.’s (2020) [94] ecological risk assessment method (Text S2) rather than exceptionally high environmental concentrations. While the measured Lu pollution indices in our samples ranked third highest, the ER calculation highlights elements with greater potential ecological impact according to this method. This approach is supported by studies using DGT in sediments, which measured substantially higher labile fractions of HREE, particularly Lu (e.g., the percentage of DGT-labile Lu being ~30× higher than La, Ce, Pr and Nd and ~2× higher than Tm [95]), indicating that the elevated ER values for Lu are consistent with the potential bioavailability rather than an artefact of the calculation. The ER values of other REYs were much lower, showing no risk for LREE, a moderate risk level for MREEs, and moderate to high for HREEs, with the ER decreasing in the following order: Lu > Ho > Tm ≈ Yb > Eu > Er ≈ Tb ≈ Dy > Sm ≈ Gd > Y ≈ Pr > Nd > Ce ≈ La. The overall PRI values, with a mean of 456, ranged from a minimum of 332 at the minimally affected site, S2, to a maximum of 577 at site S6, influenced by both shipyard and cement factory (Table 4). Based on the classification criteria (Text S2), PRI values of Pula Bay were all above the threshold of 220, which indicates moderate to high ecological risk. Among these, the most affected sites in the middle of the bay (5, 6, 7, 8, and 10) had values above the high-risk threshold of 440. As anticipated, the highest ecological risk was observed at stations with elevated pollution, with RI and PLI showing a strong correlation (r = 0.93, p < 0.001).

The ecotoxicological behaviour of REY in sediments is still poorly understood, which contributes to the absence of regulatory guidelines. Compared to the water column, sediments have received little attention as a potential exposure pathway, leaving data inadequate for robust risk evaluation [15]. While sediment-bound REYs are often regarded as immobile, they may become bioavailable when environmental conditions change or when particles are ingested by benthic species. Deposit- and filter-feeding organisms are especially at risk, as dietary uptake constitutes a major pathway of accumulation. Evidence to date indicates that benthic invertebrates accumulate higher REY levels than other taxa [13,15], with bivalves frequently proposed as suitable sentinel species for monitoring contamination in both marine and freshwater environments [18,96,97,98,99]. Most experimental investigations, however, have examined REY toxicity through waterborne exposure. Studies that tested benthic organisms in seawater, including clams, mussels, sea urchins, and macroalgae, largely focused on La and Gd, with few data available for Nd, Pr, Eu, and Dy [18,19,20,100,101,102]. The findings suggest that these elements can induce cellular damage and oxidative stress, strain antioxidant defences, and reduce species fitness, which may compromise the physiological performance (e.g., growth and reproduction), implicating the health of populations. Against this background, the ecological risk profile observed in Pula Bay sediments, negligible for LREEs but rising to moderate and high levels along the REE suite, raises a concern that heavier elements may present disproportionate risks in benthic systems of industrially affected areas, especially considering that studies based on DGT measurements show that the labile fraction relative to the total concentration in sediments tends to increase from LREEs toward HREEs [95,103]. Considering the current scarcity of sediment-based toxicity data, the elevated geo-accumulation of HREEs in industrially impacted Pula Bay, and their dominance in risk assessment, our findings underscore the importance of including HREEs in future ecotoxicological testing and risk assessment frameworks, especially in environments where benthic exposure pathways are likely to be significant.

4. Conclusions

This study highlights the distribution, sources, and potential risks of REYs in Pula Bay, examining seawater and sediment to provide complementary insights. In seawater, REYPAAS patterns largely reflect natural geochemical behaviour. However, localized enrichments of Gd and HREEs indicate minor anthropogenic inputs, suggesting that certain activities leave subtle fingerprints in surface waters without causing widespread REY contamination. Sediment REY patterns reflect a combination of natural and human-driven processes, with anthropogenic influences superimposed on a carbonate background and localized terrigenous input. These activities modify the geochemical patterns, with HREEPAAS enrichment and individual REYPAAS anomalies reflecting the characteristic signatures of historical and ongoing industrial and municipal inputs. In addition to previously recognized trace metal pollution, this has led to moderate to high sediment contamination by MREEs and HREEs and elevated ecological risk, especially for certain high-risk elements like Lu [94]. Seawater did not show contamination by REYs, but elevated Cu, Pb, and Zn in the water column found in a previous study [27] highlight additional anthropogenic pressures from ship traffic and other urban and industrial activities. These findings underscore that, despite recent remediation efforts, industrial and municipal activities continue to shape the REY geochemistry of Pula Bay, with sediments acting as reservoirs of long-term contamination, compromising the overall environmental quality of the bay. However, given the limited understanding of REY ecological effects, future efforts should prioritize improving our knowledge of their environmental behaviour and toxicity before evaluating the need and scope of specific mitigation measures.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jmse13122338/s1, Figure S1: PAAS-normalized REY patterns in seawater samples at all sampling sites. Datapoints indicate measured REYPAAS values: blue for the elements used in fitting, orange for elements where anomalies were expected (Ce, Gd, Y), and white for potentially erroneous measurement of Eu. Modelled REYPAAS concentrations were obtained using λ Polynomial Modelling, performed in R (Text S1). Shaded red areas represent ±10% relative deviation around the modelled REYPAAS concentrations; Figure S2: PAAS-normalized REY patterns in sediment samples at all sampling sites. Datapoints indicate measured REYPAAS values: blue for the elements used in fitting and orange for elements for which consistent anomalies were observed (Sm, Eu, Gd, Y, Ho). Modelled REYPAAS concentrations were obtained using λ Polynomial Modelling performed in R (Text S1). Shaded red areas represent ±10% relative deviation around the modelled REYPAAS concentrations; Figure S3: (A) Geo-accumulation index (Igeo) and (B) ecological risk factor (ER) for each REY in surface sediments of Pula Bay by sampling site. Dashed reference lines represent the thresholds between classes: for A, 1—no pollution; 2—mild; 3—moderate; 4—moderate to high; 5—high; 6—very high risk level, and for B, A—no ecological risk; B—moderate; C—moderate to high; D—high; E—very high risk level; Table S1: Water column depths at sediment sampling sites; Table S2: Measured isotopes, modes of analysis (Ar or Ar and CRC with He), and limit of detection (LOD) (n = 9) in seawater, and measured element concentrations (mean ± standard deviation) in SLRS-6 (n = 2, ICP-MS measurement runs, direct analysis), along with reference values (mean ± uncertainty; k = 2) and average recoveries (ε); Table S3: Measured isotopes, modes of analysis (Ar or Ar and CRC with He), and limit of detection (LOD) in sediment samples, and measured element concentrations (mean ± standard deviation) in NCS DC 75301 (i.e., GBW 07314) (n = 6, ICP-MS measurement runs) along with reference values (mean ± standard deviation) and average recoveries (ε); Table S4: Modelling coefficients (λ0−λ3) of PAAS-normalized REY patterns in Pula Bay seawater: λ0 represents the normalized average REY content (vertical offset of the REY pattern relative to PAAS), λ1 represents the slope (heavy vs. light REE enrichment; λ1 > 0 or depletion; λ1 < 0), λ2 represents the curvature (middle REE enrichment; λ2 < 0 or depletion; λ2 > 0), and λ3 represents higher-order deviations (no statistical meaning) (O’Neill, 2016 [47]; Ernst et al., 2025 [74]); Table S5: Modelling coefficients (λ0−λ3) of PAAS-normalized REY patterns in Pula Bay sediments: λ0 represents the normalized average REY content (vertical offset of the REY pattern relative to PAAS), λ1 represents the slope (heavy vs. light REE enrichment; λ1 > 0 or depletion; λ1 < 0), λ2 represents the curvature (middle REE enrichment; λ2 < 0 or depletion; λ2 > 0), and λ3 represents higher-order deviations (no statistical meaning) (O’Neill, 2016 [47]; Ernst et al., 2025 [74]); Text S1: R script used for REY pattern modelling: (1) Fits 3rd-degree orthogonal polynomial (λ Polynomial Modelling, λPM) to the selected REYPAAS (log-transformed to normalize data and stabilize variance) as a function of ionic radius; (2) Extracts the λ-parameters from the fit, which describe the shape of the REY pattern for each sample (Tables S4 and S5) and (3) predicts the full REYPAAS pattern from the λPM fit, including elements not used in fitting; (4) Calculates an envelope of ±10% around the predicted values (on the original scale) to assess deviations and identify anomalies; Text S2: Calculation and interpretation of pollution indices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M., O.G. and D.O.; methodology, S.M., O.G. and D.O.; validation, S.M. and O.G.; formal analysis, O.G. and A.-M.C.; investigation, O.G., A.-M.C., I.F. and D.O.; resources, O.G. and D.O.; data curation, S.M. and O.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M. and O.G.; writing—review and editing, A.-M.C., I.F. and D.O.; visualization, S.M.; supervision, D.O.; project administration, D.O.; funding acquisition, O.G. and D.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Teaching Institute of Public Health of the Region of Istria and the Croatian Science Foundation within the scope of the project “New methodological approach to bio-geochemical studies of trace metal speciation in coastal aquatic ecosystems” supported under the project number IP–2014–09–7530. S.M. is supported by the Croatian Science Foundation under the Mobility Programme (MOBODL-2023-08-7181).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the captain of the vessel “Helga”, Ivan Perković, for his kind assistance in realizing sampling campaigns.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dang, D.H.; Wang, W.; Sikma, A.; Chatzis, A.; Mucci, A. The Contrasting Estuarine Geochemistry of Rare Earth Elements between Ice-Covered and Ice-Free Conditions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2022, 317, 488–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, P.; Prego, R.; Mil-Homens, M.; Caçador, I.; Caetano, M. Sources and Distribution of Yttrium and Rare Earth Elements in Surface Sediments from Tagus Estuary, Portugal. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 621, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrat, J.A.; Bayon, G. Practical Guidelines for Representing and Interpreting Rare Earth Abundances in Environmental and Biological Studies. Chemosphere 2024, 352, 141487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatje, V.; Schijf, J.; Johannesson, K.H.; Andrade, R.; Caetano, M.; Brito, P.; Haley, B.A.; Lagarde, M.; Jeandel, C. The Global Biogeochemical Cycle of the Rare Earth Elements. Global. Biogeochem. Cycles 2024, 38, e2024GB008125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rétif, J.; Zalouk-Vergnoux, A.; Briant, N.; Poirier, L. From Geochemistry to Ecotoxicology of Rare Earth Elements in Aquatic Environments: Diversity and Uses of Normalization Reference Materials and Anomaly Calculation Methods. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 158890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedreira, R.M.A.; Pahnke, K.; Böning, P.; Hatje, V. Tracking Hospital Effluent-Derived Gadolinium in Atlantic Coastal Waters off Brazil. Water Res. 2018, 145, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerat-Hardy, A.; Coynel, A.; Dutruch, L.; Pereto, C.; Bossy, C.; Gil-Diaz, T.; Capdeville, M.J.; Blanc, G.; Schäfer, J. Rare Earth Element Fluxes over 15 years into a Major European Estuary (Garonne-Gironde, SW France): Hospital Effluents as a Source of Increasing Gadolinium Anomalies. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 656, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggert, R.G. Minerals Go Critical. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 688–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filella, M.; Rodríguez-Murillo, J.C. Less-Studied TCE: Are Their Environmental Concentrations Increasing Due to Their Use in New Technologies? Chemosphere 2017, 182, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaram, V. Rare Earth Elements: A Review of Applications, Occurrence, Exploration, Analysis, Recycling, and Environmental Impact. Geosci. Front. 2019, 10, 1285–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapasso, G.; Chiesa, S.; Freitas, R.; Pereira, E. What Do We Know about the Ecotoxicological Implications of the Rare Earth Element Gadolinium in Aquatic Ecosystems? Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 781, 146273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panichev, A.M. Rare Earth Elements: Review of Medical and Biological Properties and Their Abundance in the Rock Materials and Mineralized Spring Waters in the Context of Animal and Human Geophagia Reasons Evaluation. Achiev. Life Sci. 2015, 9, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereto, C.; Baudrimont, M.; Coynel, A. Global Natural Concentrations of Rare Earth Elements in Aquatic Organisms: Progress and Lessons from Fifty Years of Studies. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 922, 171241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, C.; Grilo, T.F.; Lopes, A.R.; Lopes, C.; Brito, P.; Caetano, M.; Raimundo, J. Differential Tissue Accumulation in the Invasive Manila Clam, Ruditapes Philippinarum, under Two Environmentally Relevant Lanthanum Concentrations. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revel, M.; van Drimmelen, C.K.E.; Weltje, L.; Hursthouse, A.; Heise, S. Effects of Rare Earth Elements in the Aquatic Environment: Implications for Ecotoxicological Testing. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 55, 334–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zocher, A.-L.; Bau, M. Rare Earth Element and Yttrium Behaviour during Metabolic Transfer and Biomineralisation in the Marine Bivalve Mytilus Edulis: Evidence for a (Partially) Biological Origin of REY Anomalies in Mussel Shells. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 958, 178056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouziotis, A.A.A.A.; Giarra, A.; Libralato, G.; Pagano, G.; Guida, M.; Trifuoggi, M. Toxicity of Rare Earth Elements: An Overview on Human Health Impact. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 948041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secco, S.; Cunha, M.; Libralato, G.; Trifuoggi, M.; Giarra, A.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Freitas, R.; Scalici, M. Evaluating the Impact of Gadolinium Contamination on the Marine Bivalve Donax Trunculus: Implications for Environmental Health. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 112, 104580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, C.; Russo, T.; Pinto, J.; Polese, G.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Pretti, C.; Pereira, E.; Freitas, R. From the Cellular to Tissue Alterations Induced by Two Rare Earth Elements in the Mussel Species Mytilus Galloprovincialis: Comparison between Exposure and Recovery Periods. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 169754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, R.; Cardoso, C.E.D.; Costa, S.; Morais, T.; Moleiro, P.; Lima, A.F.D.; Soares, M.; Figueiredo, S.; Águeda, T.L.; Rocha, P.; et al. New Insights on the Impacts of E-Waste towards Marine Bivalves: The Case of the Rare Earth Element Dysprosium. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 260, 113859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borra, C.R.; Blanpain, B.; Pontikes, Y.; Binnemans, K.; Van Gerven, T. Recovery of Rare Earths and Other Valuable Metals From Bauxite Residue (Red Mud): A Review. J. Sustain. Metall. 2016, 2, 365–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.R. Rare Earth Materials: Properties and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kaegi, R.; Gogos, A.; Voegelin, A.; Hug, S.J.; Winkel, L.H.; Buser, A.M.; Berg, M. Quantification of Individual Rare Earth Elements from Industrial Sources in Sewage Sludge. Water Res. X 2021, 11, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atinkpahoun, C.N.H.; Pons, M.-N.; Louis, P.; Leclerc, J.-P.; Soclo, H.H. Rare Earth Elements (REE) in the Urban Wastewater of Cotonou (Benin, West Africa). Chemosphere 2020, 251, 126398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.; Kim, H.; Kim, G. Tracing River Water versus Wastewater Sources of Trace Elements Using Rare Earth Elements in the Nakdong River Estuarine Waters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 160, 111589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cesare, A.; Pjevac, P.; Eckert, E.; Curkov, N.; Miko Šparica, M.; Corno, G.; Orlić, S. The Role of Metal Contamination in Shaping Microbial Communities in Heavily Polluted Marine Sediments. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265, 114823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozdanić, O.; Cindrić, A.-M.; Finderle, I.; Omanović, D. Examining the Impact of Long-Term Industrialization on the Trace Metal Contaminants Distribution in Seawater of the Pula Bay, Croatia. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiket, Ž.; Mikac, N.; Kniewald, G. Influence of the Geological Setting on the REE Geochemistry of Estuarine Sediments: A Case Study of the Zrmanja River Estuary (Eastern Adriatic Coast). J. Geochem. Explor. 2017, 182, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiket, Ž.; Mlakar, M.; Kniewald, G. Distribution of Rare Earth Elements in Sediments of the Marine Lake Mir (Dugi Otok, Croatia). Geosciences 2018, 8, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukrov, N.; Frančišković-Bilinski, S.; Hlača, B.; Barišić, D. A Recent History of Metal Accumulation in the Sediments of Rijeka Harbor, Adriatic Sea, Croatia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.; Kara, D. Determination of Rare Earth Elements in Natural Water Samples—A Review of Sample Separation, Preconcentration and Direct Methodologies. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 935, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocka, I. Determination of Rare Earth Elements Concentrations in Natural Waters—A Review of ICP-MS Measurement Approaches. Talanta 2021, 221, 121636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatje, V.; Bruland, K.W.; Flegal, A.R. Determination of Rare Earth Elements after Pre-Concentration Using NOBIAS-Chelate PA-1®resin: Method Development and Application in the San Francisco Bay Plume. Mar. Chem. 2014, 160, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, M.K.; Muratli, J.; Pradoux, C.; Wu, Y.; Böning, P.; Brumsack, H.-J.J.; Goldstein, S.L.; Haley, B.; Jeandel, C.; Paffrath, R.; et al. Rapid and Precise Analysis of Rare Earth Elements in Small Volumes of Seawater—Method and Intercomparison. Mar. Chem. 2016, 186, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Jiménez, M.F.F.; Martinez-Salcido, A.I.I.; Morton-Bermea, O.; Ochoa-Izaguirre, M.J.J. Lanthanoid Analysis in Seawater by SeaFAST-SP3TM System in off-Line Mode and Magnetic Sector High-Resolution Inductively Coupled Plasma Source Mass Spectrometer. MethodsX 2022, 9, 101625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, H.; Tagami, K.; Aono, T.; Uchida, S. Determination of Trace Levels of Yttrium and Rare Earth Elements in Estuarine and Coastal Waters by Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry Following Preconcentration with NOBIAS-CHELATE Resin. At. Spectrosc. 2009, 30, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sohrin, Y.; Urushihara, S.; Nakatsuka, S.; Kono, T.; Higo, E.; Minami, T.; Norisuye, K.; Umetani, S. Multielemental Determination of GEOTRACES Key Trace Metals in Seawater by ICPMS after Preconcentration Using an Ethylenediaminetriacetic Acid Chelating Resin. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 6267–6273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biller, D.V.; Bruland, K.W. Analysis of Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Cd, and Pb in Seawater Using the Nobias-Chelate PA1 Resin and Magnetic Sector Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). Mar. Chem. 2012, 130–131, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeghicheyan, D.; Aubert, D.; Bouhnik-Le Coz, M.; Chmeleff, J.; Delpoux, S.; Djouraev, I.; Granier, G.; Lacan, F.; Piro, J.L.; Rousseau, T.; et al. A New Interlaboratory Characterisation of Silicon, Rare Earth Elements and Twenty-Two Other Trace Element Concentrations in the Natural River Water Certified Reference Material SLRS-6 (NRC-CNRC). Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 2019, 43, 475–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebeling, A.; Zimmermann, T.; Klein, O.; Irrgeher, J.; Pröfrock, D. Analysis of Seventeen Certified Water Reference Materials for Trace and Technology-Critical Elements. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 2022, 46, 351–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiket, Ž.; Mikac, N.; Kniewald, G. Mass Fractions of Forty-six Major and Trace Elements, Including Rare Earth Elements, in Sediment and Soil Reference Materials Used in Environmental Studies. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 2017, 41, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bau, M. Rare-Earth Element Mobility During Hydrothermal and Metamorphic Fluid-Rock Interaction and the Significance of the Oxidation State of Europium. Chem. Geol. 1991, 93, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmand, A.; Dauphas, N.; Ireland, T.J. A Novel Extraction Chromatography and MC-ICP-MS Technique for Rapid Analysis of REE, Sc and Y: Revising CI-Chondrite and Post-Archean Australian Shale (PAAS) Abundances. Chem. Geol. 2012, 291, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, S.M. Rare Earth Elements in Sedimentary Rocks: Influence of Provenance and Sedimentary Processes. In Geochemistry and Mineralogy of Rare Earth Elements; Bruce, R.L., McKay, G.A., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 1989; pp. 169–200. [Google Scholar]

- Bau, M.; Schmidt, K.; Pack, A.; Bendel, V.; Kraemer, D. The European Shale: An Improved Data Set for Normalisation of Rare Earth Element and Yttrium Concentrations in Environmental and Biological Samples from Europe. Appl. Geochem. 2018, 90, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, R.L.; Gao, S. Composition of the Continental Crust. In Treatise on Geochemistry; Rudnick, R.L., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, H.S.C. The Smoothness and Shapes of Chondrite-Normalized Rare Earth Element Patterns in Basalts. J. Petrol. 2016, 57, 1463–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, D.M.; Vogt, J.; Bau, M.; Mues, M. Polynomial Modelling of High-Quality yet Incomplete Rare Earth Element Data Sets and a Holistic Assessment of REE Anomalies. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.G. Detection of Anthropogenic Gadolinium in the Brisbane River Plume in Moreton Bay, Queensland, Australia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010, 60, 1113–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, P.; Paces, T.; Dulski, P.; Morteani, G. Anthropogenic Gd in Surface Water, Drainage System, and the Water Supply of the City of Prague, Czech Republic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 2387–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobelo-García, A.; Bernárdez, P.; Mendoza-Segura, C.; González-Ortegón, E.; Sánchez-Quiles, D.; Sánchez-Leal, R.; Tovar-Sánchez, A. Rare Earth Elements Distribution in the Gulf of Cádiz (SW Spain): Geogenic vs. Anthropogenic Influence. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1304362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, G. Index of Geoaccumulation in Sediments of the Rhine River. GeoJournal 1969, 2, 108–118. [Google Scholar]

- Håkanson, L. An Ecological Risk Index for Aquatic Pollution Control.a Sedimentological Approach. Water Res. 1980, 14, 975–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, D.L.; Wilson, J.G.; Harris, C.R.; Jeffrey, D.W. Problems in the Assessment of Heavy-Metal Levels in Estuaries and the Formation of a Pollution Index. Helgoländer Meeresunters. 1980, 33, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System (Version 3.36). Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. 2014. Available online: https://qgis.org (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Schlitzer, R. Interactive Analysis and Visualization of Geoscience Data with Ocean Data View. Comput. Geosci. 2002, 28, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. EEA Coastline for Analysis (Polygon), Version 3.0 [ESRI Shapefile]. DAT-132-En. CC-BY 4.0. 2017. Available online: https://sdi.eea.europa.eu/catalogue/geoss/api/records/9faa6ea1-372a-4826-a3c7-fb5b05e31c52 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Al Momani, D.E.; Al Ansari, Z.; Ouda, M.; Abujayyab, M.; Kareem, M.; Agbaje, T.; Sizirici, B. Occurrence, Treatment, and Potential Recovery of Rare Earth Elements from Wastewater in the Context of a Circular Economy. J. Water Process. Eng. 2023, 55, 104223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Solsona, E.; Jeandel, C. Balancing Rare Tarth Tlement Distributions in the Northwestern Mediterranean Sea. Chem. Geol. 2020, 532, 119372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Solsona, E.; Pena, L.D.; Paredes, E.; Pérez-Asensio, J.N.; Quirós-Collazos, L.; Lirer, F.; Cacho, I. Rare Earth Elements and Nd Isotopes as Tracers of Modern Ocean Circulation in the Central Mediterranean Sea. Prog. Oceanogr. 2020, 185, 102340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarde, M.; Pham, V.Q.; Lherminier, P.; Belhadj, M.; Jeandel, C. Rare Earth Elements in the North Atlantic, Part I: Non-Conservative Behavior Reveals Margin Inputs and Deep Waters Scavenging. Chem. Geol. 2024, 664, 122230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, L.D.; Shinjo, R.; Hoang, N.; Shakirov, R.B.; Syrbu, N. Spatial Variations in Dissolved Rare Earth Element Concentrations in the East China Sea Water Column. Mar. Chem. 2018, 205, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Colin, C.; Douville, E.; Meynadier, L.; Duchamp-Alphonse, S.; Sepulcre, S.; Wan, S.; Song, L.; Wu, Q.; Xu, Z.; et al. Yttrium and Rare Earth Element Partitioning in Seawaters from the Bay of Bengal. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2017, 18, 1388–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukert, G.; Frank, M.; Bauch, D.; Hathorne, E.C.; Rabe, B.; von Appen, W.J.; Wegner, C.; Zieringer, M.; Kassens, H. Ocean Circulation and Freshwater Pathways in the Arctic Mediterranean Based on a Combined Nd Isotope, REE and Oxygen Isotope Section across Fram Strait. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2017, 202, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatje, V.; Bruland, K.W.; Flegal, A.R.R. Increases in Anthropogenic Gadolinium Anomalies and Rare Earth Element Concentrations in San Francisco Bay over a 20 Year Record. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 4159–4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rétif, J.; Briant, N.; Zalouk-Vergnoux, A.; Le Monier, P.; Sireau, T.; Poirier, L. Distribution of Rare Earth Elements and Assessment of Anthropogenic Gadolinium in Estuarine Habitats: The Case of Loire and Seine Estuaries in France. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 922, 171385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Salcido, A.I.; Morton-Bermea, O.; Ochoa-Izaguirre, M.J.; Soto-Jiménez, M.F. Geogenic Lanthanoid Signature in Coastal and Marine Waters from the Southern Gulf of California. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 173, 112942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]