Abstract

Ensuring navigational safety is one of the most critical challenges in autonomous maritime navigation research, requiring accurate real-time assessment of collision risks and prompt navigational decisions based on such assessments. Traditional rule-based systems utilizing radar and Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) exhibit fundamental limitations in simultaneously analyzing discrete objects such as vessels and buoys alongside continuous environmental boundaries like coastlines and bridges. To address these limitations, recent research has incorporated artificial intelligence approaches, though most recent studies have primarily focused on object detection methods. This study proposes a structured tag-based multimodal navigation safety framework that performs inference on maritime scenes by integrating YOLO-based object detection with the LLaVA vision–language model, generating outputs that include risk level assessment, navigation action recommendations, reasoning explanations, and object information. The proposed method achieved 86.1% accuracy in risk level assessment and 76.3% accuracy in navigation action recommendations. Through a hierarchical early stopping system using delimiter-based tags, the system reduced output token generation by 95.36% for essential inference results and 43.98% for detailed inference results compared to natural language outputs.

1. Introduction

In the maritime shipping industry, which handles over 80% of global trade volume, navigational safety is a top priority for protecting human life and preventing economic losses. According to the International Maritime Organization (IMO), a significant proportion of maritime accidents are attributed to human error, with situational awareness failures identified as a primary cause. Fatigue accumulation from long voyages, reduced visibility during nighttime and adverse weather conditions, and complex port entry scenarios significantly impair human operators’ judgment and can lead to collision accidents. Moreover, traditional maritime collision avoidance systems operate through rule-based algorithms using information collected via radar and Automatic Identification Systems (AIS). While these systems are effective for collision avoidance with other vessels in open waters, they fail to explicitly detect environmental boundaries such as coastlines, bridges, and narrow waterways, exhibiting fundamental limitations in situational awareness and contextual decision-making. To address these challenges, autonomous vessel technology has been rapidly advancing, with artificial intelligence-based navigation safety assessment systems emerging as a key technology.

Vision–language Models (VLMs), which have recently emerged from the convergence of computer vision and natural language processing, present a promising approach to overcoming these limitations. VLMs are capable of jointly understanding visual and textual inputs and performing reasoning in natural language. VLM applications in the maritime domain are also increasing.; however, most assume cloud-based high-performance GPUs and do not consider real-time inference capabilities. In actual maritime environments, stable internet connectivity cannot be guaranteed, and the communications latency is critical for real-time collision avoidance decisions. Therefore, developing on-device AI systems that can operate independently onboard vessels is essential.

The motivation of this study is to provide real-time maritime safety navigation support services through lightweight AI models deployable on vessels. For this purpose, on-device inference that can operate on edge devices within vessels without cloud dependence is essential. The NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin 32GB (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) is an industrial edge computing platform suitable for shipboard environments, capable of executing deep learning models within constrained power and memory budgets. These hardware constraints significantly influence model selection, and this study selected LLaVA-1.5-7B [1] as the base model for being both lightweight and reliable. Another important limitation of VLMs is poor performance on unlearned object recognition due to fixed vision encoders. LLaVA employs CLIP ViT-L/14 as its vision encoder, which performs well on general object recognition but shows limited ability to distinguish fine-grained maritime-specific objects. This study compensates for this by explicitly including YOLO object detection results in the prompt. Additionally, to address the inefficiency of natural language output, we propose a structured prompt tagging system as a core contribution.

The main objectives of this study are as follows: First, to design a multimodal maritime safety assessment system combining YOLO-based object detection with LLaVA vision–language understanding. Second, to implement a binary risk assessment framework that clearly distinguishes between safe navigation conditions and warning states requiring intervention. Third, to endow the model with the ability to predict appropriate navigation actions. Fourth, to develop a compressed yet parsable tag format that can encode object information, risk levels, navigation actions, and reasoning in a single structured representation. Fifth, to ensure logical consistency between risk assessment and navigation actions.

This paper provides the following important contributions to the maritime autonomous navigation research field: First, as a systematic study applying the LLaVA vision–language model to maritime vessel navigation safety, it employs a combination of object detection and vision–language models. Second, it proposes an original tag format that can efficiently encode and parse navigation safety information. This tag format integrates risk level assessment, navigation actions, and reasoning, achieving an average 43.98% token reduction compared to natural language output through a delimiter-based hierarchical early stopping mechanism. Third, targeting actual on-device deployable system development, it uses a lightweight model capable of inference on an NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin board, demonstrating the potential applicability of this study’s approach in real maritime environments.

2. Background

Traditional maritime navigation safety systems have primarily operated through algorithms implementing rules specified in COLREGs, based on information collected via radar and Automatic Identification Systems. The basic operational principle of these systems is to numerically evaluate collision risks with other vessels by calculating the Closest Point of Approach (CPA) and Time to CPA (TCPA). CPA represents the distance at the closest point between two vessels if they maintain their current course and speed, while TCPA indicates the time to reach that point.

CPA and TCPA calculations are based on geometric vector analysis. Given two vessels’ positions, speeds, and courses, the relative velocity vector can be calculated and used to find the point at which the distance between the two vessels becomes minimal. If the CPA is below a safe distance and the TCPA is sufficiently short, the system judges that a collision risk exists and issues a warning or suggests evasive maneuvers. This rule-based approach is mathematically clear and verifiable and has been quite effective for collision avoidance between vessels with clearly received AIS information in open waters. It has indeed played an important role in maritime safety for decades.

However, these systems have several limitations. First, small vessels that do not transmit AIS signals or non-cooperative targets cannot be detected. Leisure yachts, small fishing boats, and drifting containers often do not carry AIS, and collision risks with such objects cannot be assessed. Second, radar relies on metal reflection, making it difficult to clearly distinguish environmental obstacles such as coastlines, reefs, and bridge pillars. Particularly in adverse weather with high waves or rain, clutter noise increases, degrading detection performance. Third, in congested waters with multiple vessels in complex interactions, deriving optimal avoidance strategies through simple CPA/TCPA calculations alone is difficult. These limitations indicate that while traditional approaches work well in certain situations, they are insufficient to comprehensively handle the diverse and complex scenarios encountered at sea.

To overcome the limitations of these traditional approaches, recent research has actively employed artificial intelligence techniques. First, research on collision avoidance algorithms and simulations based on Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) is underway. Xie et al. [1] attempted to solve multi-vessel collision avoidance problems using reward functions reflecting COLREGs and DRL models, demonstrating effective avoidance performance in various maritime encounter scenarios. Cui et al. [2] proposed P3DL-PPO, an improved PPO-based DRL algorithm, learning stable avoidance policies in complex multi-vessel environments through an LSTM structure reflecting temporal information and a reward structure including COLREGs and operational constraints. Chun et al. [3] applied DRL techniques for a single vessel to avoid collisions with surrounding obstacles and other vessels, presenting a system that generates avoidance paths by reflecting Collision Risk (CR) factors and COLREGs. Additionally, Niu et al. [4] designed a Multi-Agent DRL (MADRL) structure based on actual AIS data, reproducing realistic and dynamic avoidance scenarios through simulation. Other proposed avoidance strategies combine DQN with the Velocity Obstacle model [5], and simulation-based collision avoidance research considering autonomous navigation in port and urban maritime traffic is also being conducted [6]. These studies share a common focus on data-driven policy learning and simulation-based verification, aiming to simultaneously ensure compliance with COLREGs and real-time collision avoidance performance. Despite the advantages of reinforcement learning-based approaches, significant limitations exist for their application in real maritime environments. First, the difficulty of collecting real hazardous situation data. Reinforcement learning operates by having agents perform actions and learning from resulting rewards, meaning that for safety-critical tasks like collision avoidance, agents must experience failures (collisions) to learn proper avoidance strategies. However, generating actual collision or near-miss situations with real vessels to collect data is practically impossible due to risks of human casualties and property damage. Consequently, most DRL research is conducted in simulation environments, and due to the sim-to-real gap between simulation and actual environments, there is no guarantee that learned policies will perform identically in real maritime conditions. Second, limitations of AIS data dependency. Existing DRL-based collision avoidance research predominantly relies on AIS data to determine surrounding vessels’ positions, speeds, and courses for constructing simulation environments. However, in the target environments of this study—small vessels, leisure boats, and inland waterways—AIS transmitters are frequently not installed or intentionally turned off. In practice, small fishing vessels, kayaks, and personal boats often have no AIS installation obligation, and these vessels become “invisible” collision risk factors that DRL systems cannot perceive at all. Therefore, AIS-based DRL alone cannot achieve complete situational awareness in such environments. Third, absence of explainability. DRL models are inherently black-box in nature and cannot provide human-understandable explanations for why specific actions were selected in particular situations. In safety-critical applications such as maritime navigation, human operators and accident investigators must be able to understand the basis for AI decisions, which is essential for building trust and regulatory compliance.

These limitations justify the adoption of a VLM-based approach. VLMs use camera imagery—a universal sensor input—enabling recognition of all visually perceptible objects without AIS dependency. Additionally, VLMs’ natural language reasoning capabilities can explicitly generate judgment rationales, satisfying Explainable AI requirements. However, VLM and DRL are not mutually exclusive. In an ideal future system, a complementary architecture is possible where VLM handles vision-based situational awareness and explainable risk assessment, while DRL handles specific path planning and control command generation. This study serves as foundational research validating VLM’s potential as a core component—the vision-based situational awareness and decision support module—of such integrated systems.

Object Detection technology serves as the most fundamental yet crucial component in the situational awareness-based decision-making system of autonomous vessels. Particularly in maritime environments where lighting conditions, water surface reflections, weather changes, and background complexity interact in complex ways, simply applying existing land-based object detection models is difficult. Accordingly, recent research has been proceeding toward improving YOLO family models in ways specialized for maritime environments and optimizing them for edge computing devices to simultaneously secure real-time performance and energy efficiency. Haijoub et al. [7] optimized a YOLOv8-based ship detection algorithm for the NVIDIA Jetson TX2 edge platform, achieving real-time processing speed while minimizing energy consumption. Zhang et al. [8] comprehensively reviewed deep learning-based detection and tracking technologies in the maritime object recognition field, presenting future research directions through comparative analysis based on various datasets and performance evaluation metrics. Er et al. [9] compared CNN and Transformer-based ship detection models, broadening the research scope by organizing the limitations and possibilities of each approach. Additionally, Vemula et al. [10] proposed an object recognition model enabling distance and direction estimation based on low-cost cameras in environments where radar-based detection is difficult, and Cheng et al. [11] implemented a YOLOv5-based detection system specialized for handling irregular angle problems and complex background processing in drone-captured images.

However, existing object recognition-based approaches primarily focus on detection accuracy and tracking performance, while lacking systematic integration of detected object information into reasoning, decision-making, and action planning processes. In this context, this study differentiates itself from existing research by attempting systematic integration of maritime object recognition through a structured representation method that includes both object information and reasoning bases.

Recently in the artificial intelligence field, the development of Vision–language Models (VLMs) that simultaneously understand and reason about image and text information has been noticeably accelerating, presenting an important technological turning point for autonomous system fields requiring human-level scene interpretation capabilities. VLMs are models that can simultaneously perform various high-level recognition and reasoning capabilities such as image description generation, instruction understanding, and question answering, with representative models such as Flamingo [12], CLIP [13], and LLaVA [14] showing prominence in various domains.

While VLM adoption is being attempted in the maritime field, existing research has the following limitations that hinder their development into practical decision-making systems for autonomous navigation. First, existing research primarily focuses on object detection and recognition. Representative examples include fine-grained semantic recognition using SASD [15], multi-source detection based on high-resolution imagery (Popeye) [16], and maritime object classification studies [17]. However, these studies answer only “What is there?” but fail to address “How dangerous is it?” and “What action should be taken?”—the core questions for autonomous navigation. This study extends beyond object detection to perform decision-level tasks: risk level assessment and navigation action recommendation. Second, existing research generates results in free-form natural language. For example, descriptive outputs such as “There is a small boat ahead requiring caution.” While suitable for human reading, such outputs are difficult to integrate with autonomous systems’ decision-making modules or control systems. Natural language outputs are hard to parse and may vary in expression for identical situations, resulting in poor judgment consistency and system integrability. This study proposes a structured tag-based output format that is immediately parseable via regular expressions and directly interfaceable with downstream systems. Third, most existing research assumes cloud server–based inference environments without accounting for the constraints of systems that must operate in real time aboard actual vessels. Large-scale models such as GPT-4o deliver strong general performance, but they rely on continuous communication with remote servers, making them impractical for maritime deployment where network delays, connection instability, and data transmission costs are significant limitations. Kim et al. [18] also adopted a GPT-4o-based approach; however, its dependence on cloud connectivity inherently restricts its applicability to real-world onboard operations in small vessels.

In contrast, this study employs a lightweight VLM that can run independently on edge platforms such as the NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin. By incorporating token-efficient structured outputs and hierarchical early stopping mechanisms, the proposed system achieves real-time inference without relying on external network infrastructure, enabling robust onboard operation even under unreliable maritime communication conditions. Considering these limitations of existing research, studies on VLM-based systems that can understand maritime scenes, quantitatively assess risk, output navigation decisions in structured formats immediately usable by downstream systems, and operate in real-time aboard vessels have not been sufficiently conducted. Our Structured Prompt-Based approach is designed to comprehensively address these compound requirements.

This study aims to overcome the limitations of existing research through deep utilization of VLM structure along with designing new prompt engineering and output structures specialized for maritime autonomous navigation. First, while existing VLMs focused on generating descriptive natural language from images, this study introduces a structured tag-based output method that can quantitatively infer risk level and navigation action, which are key indicators directly connected to actual decision-making. This allows AI to generate specific formatted decision outputs beyond abstract judgments. Second, rather than simply using YOLO-based object detector outputs as reference information, they are explicitly integrated into VLM input prompts in a structured form, inducing the model to reason about situations based on that object information. Unlike existing research, this is a structure that integrates the detection-reasoning-decision pipeline into a single multimodal reasoning system.

For this purpose, this study uses the publicly available WaterScenes dataset [19]. The WaterScenes dataset provides 54,120 images captured in various aquatic environments along with annotations for seven object classes (ship, vessel, boat, kayak, pier, buoy, sailor) commonly seen at sea. However, most object detection datasets, including WaterScenes, provide only object location and type information, not including high-level semantic information such as what danger that object poses to current navigation or what action should be taken. Therefore, object detection alone is insufficient to build a complete navigation safety assessment system, and additional research connecting detection results to interpretation and decision-making is necessary. In this study, we enriched the WaterScenes dataset with additional annotations based on its existing images and object information to support vision–language model training. The new labels include risk level classification, recommended navigation actions, and explanatory reasoning for each scenario. Third, this study performs Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) using the LoRA technique based on the VLM model (LLaVA-1.5-7B), achieving token lightweighting to enable real-time inference even on edge platforms such as NVIDIA Jetson Orin. Along with this, an early stopping-based structured prompt engineering technique was designed to enable hierarchical output of information at the level of 6–70 tokens depending on the situation’s urgency. Fourth, explainability was enhanced by incorporating a reasoning field that explicitly captures the basis for AI decisions. Overall, this structured prompt and output design enables VLMs to assess safety, recommend navigational actions, and justify their decisions, contributing to the development of practical and robust maritime navigation safety systems.

3. Proposed Methodology

This study represents a foundational investigation into the application of vision–language models for maritime safety, exploring whether VLMs can understand visual scenes, assess risks, and make navigational decisions in maritime environments. While existing maritime safety research has primarily focused on object detection or reinforcement learning-based path planning, this study examines whether VLMs can leverage their integrated vision–language reasoning capabilities to interpret situations and generate explainable judgments in a manner similar to human operators.

The potential application directions envisioned by this research are as follows. First, the system could serve as a perception and decision-making module for small autonomous surface vessels operating in confined waterways such as inland rivers, canals, and harbor areas, where traditional rule-based systems face significant limitations due to complex and dynamic obstacles. Second, it could evolve into an intelligent assistant system for crewed vessels, providing risk assessments and recommended actions to human operators during high-workload situations such as night navigation or adverse weather conditions. Third, the structured prompt design and evaluation methodology developed in this study can function as a foundational platform for VLM research in the maritime domain, enabling future investigations into explainable AI, human-AI collaboration, and multimodal sensor fusion.

Importantly, this study focuses on establishing the theoretical feasibility and performance upper bounds of VLMs in maritime risk assessment and navigation decision-making when provided with accurate object information. Therefore, we adopt an experimental design using YOLO Ground Truth object data to eliminate object detection errors and evaluate the pure reasoning capabilities of the VLM. Actual operational deployment would require substantial additional development beyond the scope of this foundational study, including integration with real-time object detection systems, linkage with Electronic Navigational Charts (ENC) and AIS data, interfaces with vessel control systems, and compliance with IMO and IEC international standards.

The primary contribution of this research lies in being the first systematic attempt to apply VLMs to the safety-critical domain of maritime navigation, establishing a technical foundation through structured tag-based input-output design that enables VLMs to be utilized for real-time navigational decision-making. The subsequent sections present the detailed methodology for achieving this objective.

3.1. System Architecture

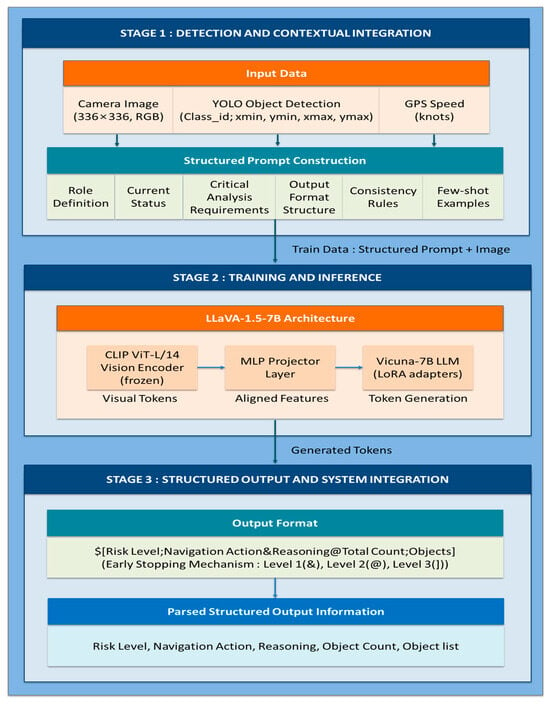

This study proposes a new technique that designs a prompt template specialized for the ship navigation domain and induces structured tag-based response format output to effectively detect various hazardous situations that may occur in maritime autonomous navigation environments and automatically derive appropriate navigation actions. The proposed technique is centered on structured output tag design and multimodal reasoning pipeline that can produce object information, hazard situation recognition, action recommendations, and judgment bases (reasoning) beyond simple image interpretation. It sought to generate judgment and reasoning bases beyond simple scene description, and designed a lightweight output prompt structure compared to natural language output to secure system integration and performance while enabling real-time operation through structured expressions rather than natural language. As illustrated in Figure 1, the entire system consists of the following three stages. (1) Detection and Contextual Integration, (2) Training and Inference, (3) Structured Output and System Integration.

Figure 1.

Proposed System Architecture Overview.

3.1.1. Detection and Contextual Integration Stage

In the Detection and Contextual Integration stage, visual perception of input images and conversion of those results into a form understandable by multimodal models are performed. For this, a YOLO model is applied to detect objects in the image and detect maritime objects such as ships, boats, buoys, and people, with each object represented in the structured format of class_id; xmin, ymin, xmax, ymax. Here, the bounding box coordinates (xmin, ymin, xmax, ymax) represent the pixel-level position of objects in the 336 × 336 input image, where (xmin, ymin) indicates the top-left corner and (xmax, ymax) indicates the bottom-right corner of the object. These absolute coordinates enable the VLM to spatially understand object positions—whether objects are located in the center, sides, or foreground/background of the scene—which is critical for assessing collision trajectories and determining safe navigation paths. This structure helps the model numerically understand not only object types but also spatial distribution, and in the prompt, the total number of objects is also specified to enable the model to quantitatively recognize scene complexity.

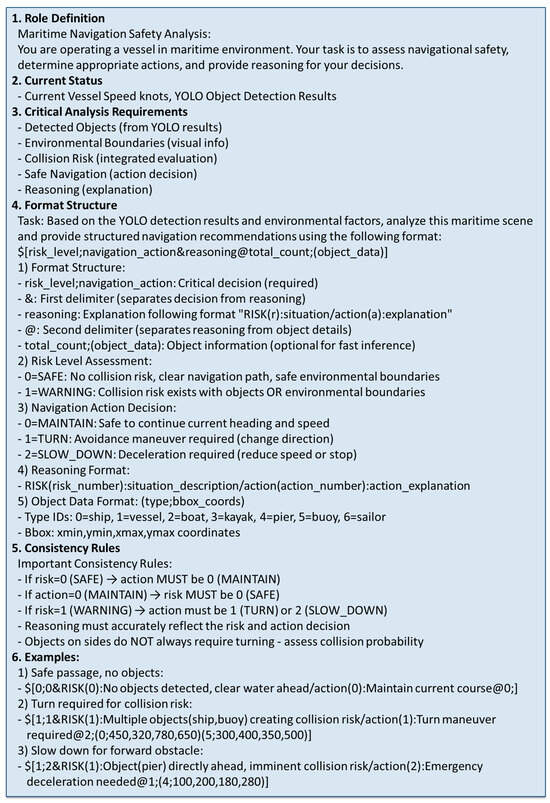

This study uses speed and object Ground Truth data from the WaterScene dataset. The core purpose of this study is to verify how well a vision–language model based on domain-specific input and output prompts can perform maritime safety assessments and navigation decisions when given accurate object information, not to evaluate YOLO object detector performance. By using Ground Truth of object and speed data, errors in the object detection stage are eliminated, allowing pure measurement of only VLM’s scene understanding, risk assessment, and decision-making capabilities. This presents the theoretical upper bound of VLM and shows the potential achievable when object detection technology improves in the future. Then, it is important to precisely construct a contextual prompt including detection results. The prompt structure proposed in this study is designed in a domain-specific manner and is a sophisticated prompt structure organized stepwise to increase model judgment reliability and structured responses. This prompt plays a role beyond simple question-answering, inducing a simulation thought flow similar to actual ship operators, with each component hierarchically providing information that the model should consider in its judgment process. As shown in Figure 2, the proposed input prompt consists of six elements.

Figure 2.

Structured prompt designed for risk assessment and navigation decision-making.

First, the prompt begins with a sentence that assigns a clear role to the model. It establishes the context in which the model is not merely an image interpreter, but a virtual agent operating within a real maritime environment. This role-based prompt design functions as a guiding mechanism that encourages the model to perform more task-aware and context-sensitive reasoning. It guides the model to interpret visual features and object detection outputs holistically, assess navigational safety, determine appropriate actions such as avoidance or deceleration, and articulate the rationale behind those decisions.

The prompt also incorporates contextual information, including the vessel’s current speed and YOLO-based object detection results. Speed is provided to reflect the dynamic nature of the maritime environment, enabling the model to better assess the urgency and proximity of potential hazards—factors that are often difficult to infer from visual inputs alone. For example, even if the same object is located within the same distance, the model can recognize that danger increases sharply if the vessel is traveling fast. Object detection results include object classes and bounding box information obtained from YOLO, structured as: ‘Current Vessel Speed: X knots, YOLO Object Detection Results: Object_count = N, Objects = [class_id; xmin, ymin, xmax, ymax, …]’. For instance, an input like ‘Object_count = 2, Objects = [0; 450, 320, 780, 650][5; 120, 300, 180, 450]’ informs the model that there are two objects: a ship (class 0) positioned at coordinates (450, 320) to (780, 650) occupying the central-right region, and a buoy (class 5) at coordinates (120, 300) to (180, 450) on the left side. The model interprets these pixel coordinates within the 336 × 336 image space to determine spatial relationships—such as whether objects are directly ahead (center region, high collision risk), on the sides (peripheral, lower immediate risk), or in the foreground versus background (based on bounding box size and vertical position). This structured representation allows the model to quantitatively recognize scene complexity and perform spatial reasoning beyond pure visual perception.

Following the presentation of current status information, the prompt outlines five critical analysis requirements that guide the model’s decision-making process. These include: identifying detected objects with their types, positions, and sizes; recognizing environmental boundaries such as coastlines, landmasses, and bridge pillars; assessing collision risk based on both detected and undetected elements; determining safe navigation actions such as avoidance or deceleration; and providing reasoning that justifies the decision. A particularly important design strategy is instructing the model to reason beyond YOLO detection results by interpreting broader visual cues present in the entire image. This approach compensates for the limitations of the object detector and encourages the vision–language model to perform holistic scene understanding, thereby emulating realistic maritime judgment capabilities. For example, when presented with images containing bridge structures, the model recognizes them as “a prominent structure spanning across the waterway”, demonstrating awareness of large-scale infrastructure that constrains navigation routes. In scenarios with coastlines and land boundaries, the model explicitly describes that “the land mass extends from the left side of the image to the right, creating a shoreline” and characterizes the waterway as “relatively narrow,” indicating spatial understanding of confined navigation conditions. These qualitative observations confirm that the structured prompt successfully enables the model to interpret continuous environmental features alongside discrete detected objects, integrating both types of information into coherent maritime safety assessments.

The response format is also designed to follow a fixed structured tag format rather than free description. Responses are composed in the order of risk level, navigation action, judgment basis, object count, and object list, with each piece of information separated by delimiters specialized for early stopping. This design not only makes generated responses easy for humans to understand but also enables immediate system parsing and utilization, increasing the possibility of integration with automated decision-making systems. Additionally, it enables hierarchical early stopping and response level adjustment, such as inferring only simple judgment results first or outputting complete information as needed, thereby securing operational flexibility. Detailed explanation of classes and structured tags is provided in the Structured Output and System Integration stage.

To ensure logical consistency in the model’s outputs, the prompt explicitly defines a set of consistency rules that govern the relationships between key response components. For example, if the risk level is 0 (SAFE), the action must also be 0 (MAINTAIN); conversely, if the action is 0 (MAINTAIN), the model must have assessed the situation as 0 (SAFE). In cases where the risk is 1 (WARNING), the prompt enforces that the recommended action must be either 1 (TURN) or 2 (SLOW_DOWN), thereby prohibiting illogical decisions such as maintaining course under warning conditions. Furthermore, the reasoning component is required to accurately justify the selected risk and action pair.

Finally, the prompt includes representative situation-specific input-output examples as few-shot demonstrations. These examples cover a variety of scenarios, including safe navigation in open waters, complex scenes with mixed dynamic objects, and hazardous situations requiring a stop due to structural obstacles ahead. Each example is constructed in strict accordance with the defined structured tag format. By incorporating these few-shot examples, the prompt leverages in-context learning to guide the model toward generating consistent and desirable outputs, even in the absence of explicit fine-tuning. This strategy enhances the model’s generalization ability and inference stability under diverse real-world maritime conditions.

This prompt design functions not merely as a sequence of linguistic inputs, but as a procedural reasoning scenario that induces the model to execute a complete judgment flow. Through a series of structured components—including few-shot exemplars—the model is assigned a specific role as a maritime recognizer, interprets the situational context, and generates outputs based on predefined decision logic and structural consistency. By leveraging in-context learning, the prompt enables the model to internalize the structure and semantics of desirable outputs without the need for task-specific fine-tuning. This mechanism serves as a foundational strategy for adapting vision–language models into reliable, real-time autonomous decision-making agents in uncertain and dynamically changing maritime environments.

3.1.2. Training and Inference Stage

In the Training and Inference stage, the process of inputting structured prompts and input images together into a multimodal model and generating judgment results occurs. Among LLaVA family VLMs, it is based on the LLaVA-1.5 model, which is a multimodal architecture composed of a CLIP ViT-L/14 vision encoder, Vicuna-7B v1.5 language model, and a 2-layer MLP projector connecting the two modules, with approximately 7B parameters. LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation)-based fine-tuning was performed to strengthen domain-specific judgment capability. Fine-tuning the entire vision–language foundation model requires massive computational resources and memory and can impair the performance of existing models trained on large amounts of data. Therefore, for training vision–language models suitable for domains, a process that improves performance while training efficiently is necessary. LoRA is a Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) technique that satisfies these requirements. The LoRA was implemented using the peft library (Version 0.11.0)

The core idea of LoRA is to learn only small adapter matrices decomposed into low rank while keeping the weight matrix of the pre-trained model fixed. The LoRA update rule for arbitrary weight matrices is expressed as follows.

where and are learned low-rank matrices, is the rank, and is a scaling factor. When rank is much smaller than the original matrix dimensions and , the number of parameters to be learned is greatly reduced from to . The selection of target modules to apply LoRA significantly affects learning performance and efficiency. In this study, LoRA was selectively applied to key transformation layers of the language model. Specifically, LoRA was applied to the four projection layers of the attention mechanism in each transformer layer (q_proj, k_proj, v_proj, o_proj), three layers of the feedforward network (gate_proj, up_proj, down_proj), and two linear layers of the vision–language projector (linear_1, linear_2). This selection aims to secure sufficient adaptation capability with limited parameters by focusing on the most important layers for adjusting the model’s expressiveness.

The attention mechanism is the core of transformers, capturing relationships among different positions in the input sequence. In image-text fusion, attention models interactions between visual tokens and linguistic tokens, so adapting this part is important for improving multimodal understanding capability. The feedforward network independently transforms each token, contributing to domain-specific feature extraction. Since the projector is a bridge connecting vision and language modalities, learning this part is important for transforming visual features of maritime images into a form understandable by the language model.

Therefore, this study efficiently trains only the core transformation layers of the language model by applying the representative fine-tuning technique LoRA. While general VLMs are pre-trained on large-scale image-text pairs, maritime environments are special domains that do not appear sufficiently in general datasets, requiring additional fine-tuning. In this study, while maintaining the structure of the existing LLaVA model’s Visual Encoder and Language Model, LoRA adapters were inserted into the text decoder, training only 1.19% of total parameters, greatly improving memory efficiency and training speed while enabling effective domain adaptation and lightweight learning. This method can effectively strengthen structured output generation capability and reasoning capability needed for risk judgment without changing the entire model’s weights.

Training data receives WaterScenes maritime images and systematized input prompts as input and is trained to generate responses in the specified structured format. In this process, example samples and rules in the prompt act as important learning guidelines for maintaining consistency in response format and expression content. In the inference process, based on object information and situation description included in the prompt, the model quantifies the risk level of a given scene, decides corresponding navigation actions, and generates reasons for judgment in natural language. Simultaneously, the model considers response format constraints to express the entire judgment in structured tag format. This structure is distinguished from existing methods in being designed to generate stable and interpretable inference results even in real-time systems by imposing structural constraints on VLM’s free response capability during the learning process.

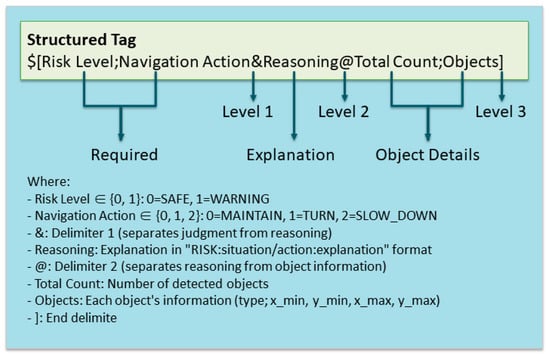

3.1.3. Structured Output and System Integration Stage

In the Structured Output and System Integration stage, the trained model outputs in the form of structured tags. This study secures parsing ease, response consistency, and reliability of AI judgment results by not using free-form natural language responses but adopting only structured outputs. The tag format is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Structured output tag format used in the proposed system.

One of the core contributions of this study is the design of the structured tag system. Most existing vision–language models generate responses in free-form natural language, which is suitable for conversation with humans but causes several problems in integration with autonomous systems. First, natural language is inherently ambiguous. Expressions like “caution is needed, there may be danger, be careful” do not clearly convey quantitative risk levels. Second, natural language parsing is complex and error-prone. Parsing “I recommend turning left” requires multiple steps including natural language understanding, syntactic analysis, and semantic extraction. Third, natural language has low token efficiency. More words are needed to convey the same content, and in autoregressive generation, time increases proportionally to the number of tokens. Fourth, consistency verification is difficult. It is hard to automatically detect logical contradictions like “safe but avoid.”

The structured tags of this study were designed to solve these problems. Each field of the tag has clear semantics and represents exactly one value. Risk level ∈ {0,1} is a binary risk level with no ambiguity, and navigation action ∈ {0,1,2} explicitly specifies one of three navigation actions. Delimiters (&, @, ]) separate information hierarchies at fixed positions, making parsing possible through simple string splitting. Token count is minimized for fast generation speed, and consistency rules are expressed in mathematical logic for automatic verification: .

Additionally, the output tags through the proposed technique provide three levels of early stopping functionality using delimiters, as summarized in Table 1. Level 1 contains only risk level and action with minimal information, has the fewest response tokens, and is suitable for real-time early judgment. Level 2 includes judgment basis, allowing users or systems to interpret the reason for judgment, and Level 3 includes object count and each object’s location to provide explainability for the entire scene. This multi-level response structure allows adjustment of required information amount according to actual system demands and is effective in conserving computational resources by applying early stopping strategies.

Table 1.

Delimiters and corresponding early stopping levels.

Analyzing the specific tag structure in detail is as follows. The start symbol ‘$[’ clearly marks the beginning of the tag. The ‘$’ symbol is not commonly used in general text, making it suitable as a unique marker distinguishing tags from general text. The risk level field is a binary classification indicating SAFE(0) or WARNING(1). The core question of maritime safety is whether it is safe and whether action is needed, and binary classification directly answers this. The delimiter ‘;’ separates risk level and action. The navigation action field navigation action is a three-category variable indicating MAINTAIN(0), TURN(1), or SLOW_DOWN(2). These three cover basic responses in ship navigation. MAINTAIN means normal navigation maintaining current course and speed, TURN means direction change to avoid obstacles, and SLOW_DOWN means deceleration or stop for hazardous elements. The delimiter ‘&’ separates the core judgment part including risk level and navigation action from the reasoning explanation part. Up to this delimiter is the boundary for Level 1 early stopping, and parsing only up to ‘$[risk_level;navigation_action&’ can immediately obtain the most urgent information. The ‘&’ symbol was chosen because it implies logical AND, suggesting that judgment and reasoning are combined. The reasoning field is free text but follows the format ‘RISK(risk_level):situation/action(navigation_action):justification’. For example, ‘RISK(1):Ship ahead creating collision risk/action(2):Deceleration required’. This format clearly connects risk assessment and action recommendation, presenting bases for each. There are several reasons for including the reasoning field. First, explainability is essential in safety-critical systems. Operators need to understand why AI recommends specific actions, and recommendations without explanation are difficult to trust. Second, it improves model reasoning quality through Chain-of-Thought effect. Forcing the model to explicitly generate judgment bases leads to more careful and logical judgments. Third, it helps debugging and monitoring. Causes of incorrect judgments can be identified through reasoning text, and in case of accidents, records remain of what information AI based its judgment on.

Then, the delimiter ‘@’ separates the reasoning part and object information part. Up to this delimiter is the boundary for Level 2 early stopping. The object count field indicates the number of object tuples to follow. This tells the parser the expected number of objects, enabling early detection of parsing errors. For example, if n = 3 but only 2 are actually parsed, it can be known that the model omitted an object. n = 0 explicitly indicates that YOLO detected nothing, and even in this case, the model can evaluate environmental hazards by analyzing the image. Object data represents each object’s information in the format ‘(type; xmin, ymin, xmax, ymax)’. For example, ‘(ship; 450, 320, 780, 650)’ indicates that a ship-type object is located in that bounding box. Parentheses were used to clearly distinguish each object as an independent unit. The reason for including object information is to verify whether the model accurately referred to YOLO results during inference. Comparing object information generated by the model with actual input Ground Truth can evaluate the model information processing fidelity.

Finally, the ending delimiter ‘]’ explicitly marks the end of the tag. This informs the parser that there is no more content to parse and also acts as a termination condition for the generation process. The model is trained to immediately stop output upon generating ‘]’. Additionally, through consistency constraints, it is ensured that route maintenance occurs only in safe situations. These constraints are explicitly included in the prompt for the model to recognize during training and are also checked at the output stage.

The generated structured tags can be used for actual system integration in the following ways: First, risk level values can be converted to colors or alarms on visual UI to provide warnings to users. Second, navigation action codes are directly mapped to control system commands for avoidance, deceleration, or stop. Third, reasoning items are used for reviewing and recording judgment results. Fourth, object location information is displayed as bounding boxes on screen, allowing users to directly visually confirm the situation. Thus, output is not merely an explanation but actual control data used for action induction and judgment verification in operational systems. Additionally, this structure is lightweight to run in real-time on Jetson Orin AGX-based edge devices, and token count reduction and response format clarification contribute to improving the entire system’s inference speed. The fact that VLM responses can be directly transmitted to control systems through structured responses shows that this study’s methodology can be applied beyond experimental scope to actual operational environments.

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Experimental Dataset

The experiments of this study were systematically designed to verify the effectiveness of the proposed structured tag system and quantitatively analyze the contribution of each component to overall system performance. The experiments of this study were constructed based on the WaterScenes dataset [19]. WaterScenes is a multimodal dataset designed for autonomous driving research in aquatic environments, collected using Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USVs) in the Suzhou region of China from June to December 2022. Collection areas were selected considering water quality conditions and environmental diversity, including various types of waterways such as large and small rivers, lakes, canals, and moats. Unlike open ocean environments where COLREGs (International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea) provide clear directional guidance (e.g., port-side passing in head-on situations), these confined waterways present fundamentally different navigation constraints. In narrow canals and congested harbor areas, the choice between turning left or right often depends on dynamic factors such as channel width, water depth distribution, traffic flow patterns, and proximity to shorelines—factors that cannot be predetermined by fixed rules. Additionally, the limited maneuvering space in such environments means that overly specific directional commands (e.g., ‘turn 15° to port’) may not be executable given the vessel’s turning radius and environmental constraints. These diverse waterway environments are essential for training models to robustly operate in various maritime conditions, as object types and surrounding environments vary according to water quality conditions. The WaterScenes dataset focuses on common objects of interest on water surfaces, largely divided into static and dynamic objects. Static objects include piers and buoys, which serve as waterway markers or berthing facilities at fixed locations. Dynamic objects include various sizes and types of aquatic vehicles such as ships, boats, vessels, and kayaks, as well as sailors aboard these vehicles. This study used all 7 object classes, each having different meanings in maritime safety judgment.

One notable advantage of the dataset is that it was collected under diverse environmental conditions. In terms of time conditions, data from various times including daytime, nighttime, and twilight are included, enabling evaluation of model robustness according to lighting conditions. This study utilized only RGB camera images and GPS-based speed data among various types of data in the WaterScenes dataset. While WaterScenes is originally a multimodal dataset including various sensor data such as RGB camera, 4D imaging radar, LiDAR, and GPS/IMU, since this study’s focus is on visual scene understanding and linguistic reasoning capability of vision–language models, it was limited to only image, object information, and speed information. RGB images were captured by forward-facing cameras and were resized to 336 × 336 pixels to match the input size of LLaVA-1.5 model’s vision encoder (CLIP ViT-L/14). From GPS data, the vessel’s current speed was extracted and used. Speed is expressed in knots and provides essential contextual information for evaluating dynamic hazards that are difficult to judge from visual information alone. Since risk level and appropriate response actions vary according to vessel speed even with the same object arrangement, speed acts as important contextual information for situation judgment.

Object recognition labels provided by the WaterScenes dataset were also utilized. The dataset includes bounding box annotations for each image, with precise location information (xmin, ymin, xmax, ymax) provided for seven object classes as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Seven Object Classes in WaterScenes Dataset.

As shown in Table 2, the WaterScenes dataset focuses on seven common object types encountered in maritime environments, categorized into static and dynamic objects. Static objects (pier, buoy) represent fixed environmental boundaries and navigation markers, while dynamic objects (ship, vessel, boat, kayak, sailor) include various watercraft and personnel with different movement characteristics. Each class carries distinct implications for maritime safety assessment: larger vessels pose collision risks due to momentum and size, while smaller craft like kayaks present detection challenges. The inclusion of ‘sailor’ as a separate class enables the model to recognize personnel safety concerns. This study utilizes all seven classes, as each contributes unique contextual information for risk assessment and navigation decision-making. This study used these Ground Truth bounding boxes as YOLO detection results. The reason for not conducting separate YOLO model training is that this study’s purpose is to verify how well VLM can make correct risk assessment and navigation decisions when given accurate object information, not to evaluate object detection system performance. This study aimed to eliminate variability in object detection performance and purely measure risk level assessment and navigation action prediction capability by directly utilizing precise bounding box annotations.

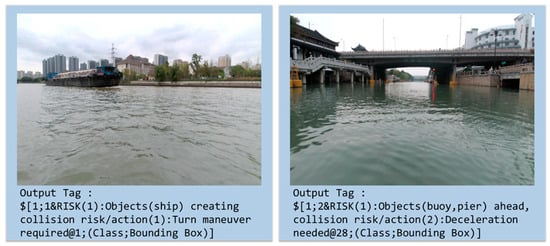

However, the original WaterScenes dataset does not include annotations for high-level decision labels related to maritime safety, namely Risk Level, Navigation Action, and Reasoning. This is because WaterScenes was originally designed for recognition tasks such as object detection, tracking, and scene segmentation. Therefore, this study conducted separate labeling. Among the total 54,120 images, 24,000 images suitable for safe navigation service development were selected, and As shown in Figure 4, tag information based on risk level, navigation action, and judgment basis was assigned through expert labeling.

Figure 4.

Structured output tag examples.

The labeling process proceeded as follows. First, experts comprehensively considered object arrangement within each image, available space, expected collision risk, and vessel’s current speed to label risk level (SAFE = 0 or WARNING = 1), navigation action (MAINTAIN = 0, TURN = 1, SLOW_DOWN = 2), and judgment basis (reasoning in free text format). The reasoning field is text explaining why that risk level and action were chosen, following the format “RISK(risk_level):situation description/action(navigation_action):action justification”. For example, if the current vessel is in a dangerous state and avoidance is needed, it would output like “RISK(1):Multiple vessels ahead creating collision risk/action(1):Turn maneuver required”. The finally constructed 24,000 image dataset was split into training, validation, and testing, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Dataset Split and Distribution.

4.2. Experimental Protocol and Evaluation Metrics

This subsection describes the experimental workflow, evaluation procedures, and metric definitions employed in this study. While the model architecture has been detailed in Section 3 and hyperparameter settings are specified in Section 4.3, here we focus on the practical execution of experiments, rigorous evaluation protocols, and formal definitions of performance metrics.

The experimental procedure consists of three sequential phases: training, validation monitoring, and final testing. In the training phase, the 20,000 training images from the WaterScenes dataset were processed into structured input-output pairs. Each input consists of a maritime image resized to 336 × 336 pixels, vessel speed information, Ground Truth object detection results for the seven object classes, and a carefully constructed prompt following the structure described in Section 3.1.1. The corresponding output is the structured tag containing risk level, navigation action, reasoning, and object information.

Model training was conducted using the LoRA-based fine-tuning approach described in Section 3.1.2 with hyperparameters specified in Section 4.3. Training proceeded over three epochs with continuous monitoring of validation set performance. The validation set of 2000 images served as an independent check on model generalization throughout the training process. Model checkpoints saved at the end of each epoch were compared based on their validation performance, and the final checkpoint was selected for evaluation.

To systematically evaluate the contribution of individual components to overall system performance, we designed an ablation study with three configurations that progressively incorporate key features. The Baseline-LLaVA configuration serves as the simplest baseline, trained and evaluated without object detection information in the input and without requiring reasoning in the output. The Object-Grounded LLaVA configuration adds YOLO detection results to the input while still excluding few-shot examples from prompts and reasoning from outputs. Finally, the Few-shot Reasoning LLaVA configuration represents our complete proposed system with all components included: object detection information, few-shot examples in structured prompts, and reasoning generation in outputs. Importantly, all three configurations were trained using identical optimization settings, learning rate schedules, batch sizes, and hardware configurations as specified in Section 4.3. Each configuration underwent the same three-epoch training process with validation monitoring, and all models were evaluated on the identical test set. This controlled experimental design ensures that observed performance differences can be attributed to the specific components being varied rather than to differences in training procedures or evaluation protocols.

For performance assessment, we employed standard classification metrics to quantitatively evaluate model predictions. The primary evaluation metric is classification accuracy, which measures the proportion of correct predictions among all valid test samples. For a given task (risk level assessment or navigation action prediction), accuracy is formally defined as:

where is the total number of valid test samples, is the Ground Truth label for sample , is the predicted label, and is the indicator function that equals 1 when the condition is true and 0 otherwise. A prediction is considered correct if and only if it exactly matches the Ground Truth. For risk level assessment, predictions are in the set , while for navigation action prediction, predictions are in .

To provide class-specific performance analysis that accounts for potential class imbalances in the test set, we additionally computed precision, recall, and F1-score for each class. For a given class , precision measures the proportion of correct predictions among all instances predicted as that class:

where (True Positives) represents the number of instances correctly predicted as class , and (False Positives) represents the number of instances incorrectly predicted as class when they actually belong to other classes. Recall measures the proportion of actual class instances that are correctly identified by the model:

where (False Negatives) represents the number of actual class instances that were incorrectly predicted as other classes. The F1-score combines both precision and recall through their harmonic mean:

This metric provides a balanced measure that is particularly useful when there is a trade-off between precision and recall. For risk level assessment with two classes, we calculate precision, recall, and F1-score for each class (SAFE and WARNING) separately. Similarly, for navigation action prediction with three classes, we report these metrics for each action category (MAINTAIN, TURN, SLOW_DOWN) individually to provide comprehensive performance assessment.

Token efficiency was evaluated by measuring the number of tokens generated at each of the three hierarchical output levels. For each test sample, we recorded the token count at three stopping points: after the first delimiter ‘&’ for Level 1 output containing only risk_level and navigation_action, after the second delimiter ‘@’ for Level 2 output additionally including reasoning, and at the final delimiter ‘]’ for Level 3 output containing complete information with object details. Tokenization was performed using the LLaMA tokenizer consistent with the base model architecture. Token reduction rates were calculated relative to the full Level 3 output to quantify the efficiency gains achievable through early stopping at each level.

4.3. Hyperparameter Settings

LoRA hyperparameters used in this study are as follows. Rank provides a balance between expressiveness and efficiency. Too small a rank (e.g., r = 8) can limit the model’s adaptation capability, while too large a rank (e.g., r = 128) reduces efficiency gains. Scaling factor is set so that , appropriately controlling the magnitude of LoRA updates. Dropout 0.05 was applied to prevent overfitting. Consequently, trainable parameters are approximately 85.1 M, only about 1.19% of the entire model. This means a 98.79% parameter reduction compared to full fine-tuning training of 7B parameters. Training settings are as follows. AdamW in PyTorch (Version 2.9.0) was used as the optimizer. AdamW is an improved version of Adam, applying weight decay directly to weights rather than gradients, providing more effective regularization. Learning rate was set to , and a cosine annealing schedule was applied to gradually decrease learning rate in the latter part of training.

Overall training was conducted for 3 epochs. During training, a 16-bit quantization technique was used to halve memory usage and improve training speed. All inference results were performed on the NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin 32GB platform. The Jetson AGX Orin board’s Tensor Cores are specialized for FP16 computation, enabling much faster processing compared to FP32. Jetson AGX Orin is an edge AI computing platform based on Ampere architecture GPU, equipped with 64 Tensor cores. The 32GB unified memory is sufficient for inference of 7B parameter models, enabling real-time processing. Power consumption is limited to a maximum of 60 W, making it sufficiently usable in shipboard environments.

5. Experimental Results

This section systematically analyzes the performance of the proposed safe navigation system. It presents overall performance evaluation and comparative analysis, component-wise contribution analysis, and token efficiency and early stopping results. To quantitatively evaluate the contribution of each component of the proposed system to overall performance, three experimental configurations were designed, as summarized in Table 4. At this time, while overall training and test prompts are similar, experiments were conducted by adding or excluding key elements. This ablation study enables independent measurement of the effect of object detection information and the effect of reasoning explanation, ultimately demonstrating the integrated value of the proposed system.

Table 4.

Experimental configurations to evaluate component-wise contributions.

The Baseline-LLaVA configuration is the most basic form, including neither object detection information nor reasoning explanation in training and inference processes. This configuration is to verify whether vision–language models can judge maritime risk level and navigation action solely through image understanding capability. If the Baseline-LLaVA model demonstrates sufficiently high performance, it may indicate that complex object detection pipelines are not essential. Conversely, if the performance is suboptimal, it highlights the necessity of incorporating structured object-level information to support effective reasoning.

The second is Object-Grounded LLaVA, which includes YOLO’s Ground Truth object detection results in input but does not provide result examples during training and reasoning during inference. This configuration isolates the contribution of structured object information. The performance improvement of Object-Grounded LLaVA over Baseline-LLaVA quantitatively reflects the utility of object-level input for multimodal reasoning.

Finally, the Few-shot Reasoning LLaVA model, to which the proposed techniques are applied, is the complete form including object detection information, specific input prompts and examples, and reasoning bases during inference, representing the final system proposed in this study. Comparison of the three models shows the effect of object information input in vision–language models specialized for maritime domains, the effect of few-shot learning in input prompts, and the effect of including reasoning bases at the risk level judgment and navigation action inference stages. Each configuration uses the same training data and hyperparameters to ensure fair comparison, with differences only in input and output formats. The experimental results of this study are as follows, as summarized in Table 5. The proposed system achieved risk level assessment accuracy of 86.1% and navigation action prediction accuracy of 76.3%. The valid prediction rate reflecting whether data was properly output in structured form recorded 99.75%, outputting in specific tag form for almost all samples, demonstrating that the model very stably learned the proposed complex structured tag format and can operate reliably in practical environments.

Table 5.

Performance comparison of each model on risk level assessment and navigation action prediction.

The contribution of each component can be quantitatively evaluated through comparison among the three experimental configurations. In terms of risk level assessment, the transition from Baseline LLaVA to Object-Grounded LLaVA means adding object detection information, with accuracy improving from 59.68% to 75.26%. This indicates that LLaVA uses CLIP ViT-L/14’s vision encoder as a backbone, which has sufficient training on object data for everyday situations and common objects but lacks training on specific maritime objects, and to compensate for this, linkage with YOLO family models is essential rather than using only the LLaVA model. Visual elements such as object type, location, and size provide essential contextual information for risk judgment.

The transition from Object-Grounded LLaVA to the final proposed model Few-shot Reasoning LLaVA includes not only adding reasoning explanation but also Few-shot prompt composition including role definition, consistency rules, and situation examples, with accuracy improving from 75.26% to 86.10%. This suggests that beyond simply providing visual object information as input, the model’s ability to interpret situations and derive conclusions through internal reasoning processes plays a decisive role in improving judgment accuracy. Particularly, prior scenario learning provided through a Few-shot method has the effect of making the model internalize intuitive response strategies for similar situations, enabling rapid acquisition of thinking methods specialized for maritime domains where prior training is insufficient.

Similar trends are observed in navigation action prediction, with more pronounced improvement patterns. Baseline LLaVA recorded 53.25% accuracy, while Object-Grounded LLaVA improved to 63.37%. and the final proposed model Few-shot Reasoning LLaVA increased accuracy to 76.30%. This means that in complex decision-making situations such as collision avoidance, object detection information, reasoning capability, and response strategy learning based on past cases all play essential roles.

Overall, performance improvement from Baseline to the final model shows that while each component makes independently meaningful contributions in both risk level assessment and navigation judgment, synergistic effects are maximized when combined. Additionally, by including clear reasoning bases in responses, the Chain-of-Thought reasoning effect was stably demonstrated. This mechanism enables securing not only judgment accuracy but also response reliability and explainability simultaneously, acting as a factor increasing practical application possibility.

The poor performance of Baseline-LLaVA reveals the fundamental difficulties lightweight VLMs face in understanding maritime scenes without object information. The Baseline-LLaVA configuration, which provides only image and speed information without YOLO object detection, achieved 59.68% accuracy in risk level assessment and 53.25% in navigation action prediction. While better than random guessing, these results are insufficient for safety-critical applications. This limitation stems from the fact that LLaVA-1.5 uses the CLIP ViT-L/14 vision encoder, which was pretrained on general-domain data and remains frozen during our fine-tuning, resulting in limited capability to explicitly distinguish maritime-specific objects such as ships, buoys, and piers.

In contrast, the Object-Grounded LLaVA configuration, which includes YOLO object detection results in the input, achieved 75.26% accuracy in risk assessment—a 15.58 percentage point improvement (Table 5). This substantial improvement demonstrates that explicit object information provided through YOLO resolves a critical bottleneck in scene understanding for lightweight VLMs. The structured object information enables the VLM to accurately know ‘what is where,’ allowing it to focus on higher-level reasoning about ‘how dangerous it is’ and ‘how to respond’.

The 15.58 percentage point improvement signifies more than simply providing additional information—it demonstrates that explicit object information is essential for lightweight VLMs to achieve acceptable performance in maritime safety-critical applications. This validates that while large cloud-based VLMs (GPT-4V, Gemini) can recognize maritime objects autonomously, the object recognition capabilities for practical on-device systems can be effectively implemented through YOLO integration. Therefore, for lightweight on-device VLMs deployed on edge platforms such as NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin, integration with object detection modules like YOLO is not merely auxiliary but an essential component.

To understand the limitations of the proposed system, we systematically analyzed cases where the model generated incorrect predictions. Errors occurred in 13.9% of risk level assessments and 23.7% of navigation action predictions. These failure cases are categorized into the following types. First, confusion in complex multi-object situations. In complex scenes with multiple objects simultaneously present, the model was observed to select incorrect navigation actions. For example, in situations with a buoy on the left and a ship ahead, the model predicted TURN (1) while the Ground Truth was SLOW_DOWN (2). This demonstrates that the model’s judgment about which threat factor to prioritize may differ from expert judgment when multiple hazards exist. Second, performance degradation in nighttime and low-light conditions. Relatively higher error rates were observed in nighttime, twilight, and backlit images included in the WaterScenes dataset. In low-light environments, visual features of objects become unclear, and performance degrades because the CLIP vision encoder was trained on general domains rather than being specialized for maritime nighttime environments. Third, uncertainty in boundary situations between WARNING and SAFE. While the model makes accurate judgments in situations with clearly high or low risk, errors occur in ambiguous boundary situations. For example, when objects are at intermediate distances with uncertain collision probability, even experts may disagree on the appropriate judgment, reflecting inherent subjectivity in labeling. Fourth, confusion between TURN and SLOW_DOWN. The most frequent error type in navigation action prediction is confusion between TURN (1) and SLOW_DOWN (2). Both actions are avoidance behaviors in hazardous situations, and which action is more appropriate depends on various factors including vessel maneuvering characteristics, available surrounding space, and predicted paths of other vessels. The input information used in this study (image, speed, object positions) has limitations for such detailed judgments. Limitations revealed by failure analysis. The absence of temporal context, domain-specific limitations of the lightweight vision encoder, and difficulty in fine-grained distinction between avoidance actions can be improved in future research through time-series model integration, vision encoder fine-tuning, and integration of additional sensor information (radar, AIS).

Additionally, one of the advantages of the proposed technique is efficient token usage through an early stopping mechanism. To additionally evaluate token efficiency, average token counts for each early stopping level were measured. Average token counts for Level 1 (up to & delimiter), Level 2 (up to @ delimiter), and Level 3 (up to ] delimiter, complete output) were calculated, and reduction rates were calculated by comparing with token counts when expressing the same information in natural language, as summarized in Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 6.

Average token usage and reduction rate by output level.

Table 7.

Token reduction by output level for sample navigation scene.

Comparison with natural language output more clearly shows the efficiency of the proposed format. When expressing the same information in natural language sentences, an average of about 130 tokens are needed. Stopping at Level 1 can obtain risk level and navigation action information with an average of only 6.03 tokens, having the effect of reducing 95.36% of tokens compared to the complete output. Level 1 token count is very consistent, with almost all samples using exactly 6 tokens, making predictability very high. This means millisecond-level response time can be achieved in emergency situations, a decisive advantage in real-time maritime safety systems.

Stopping at Level 2 can include risk level, navigation action, and reasoning explanation with an average of 29.69 tokens, having 77.16% token reduction effect compared to the complete output. This is the optimal length that briefly explains the situation while sufficiently conveying necessary information. Level 3 provides complete output including all object information with an average of 72.83 tokens; while variability increases as output length varies according to object count, efficient expression is possible with an average 43.98% token reduction effect.

Beyond token efficiency, a structured format provides clear advantages in terms of parsing ease, consistency, and automation. It can be immediately parsed using regular expressions, making post-processing very easy, as the risk level is the first number, the navigation action is the second, and the object count appears after the @ delimiter, making extraction logic simple. In case of natural language output, natural language processing pipeline is needed due to various expression methods, and parsing error possibility is high, but structured tags have very high parsing reliability due to fixed format.

Furthermore, to evaluate the system’s real-time inference capability enabled by token efficiency, we measured end-to-end inference latency on the NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin 32 GB platform (Table 8). Level 1 early stopping achieves 5.7-s total latency, Level 2 requires 14.5 s, and Level 3 outputs require 30 s. Compared to natural language descriptions requiring 54 s, the structured approach achieves 89.4%, 73.1%, and 44.4% latency reduction for Levels 1, 2, and 3 respectively.

Table 8.

Inference Time on NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin 32GB platform.

Notably, the token reduction rates and latency reduction rates are not identical. For example, Level 1 reduces tokens by 95.4% compared to natural language but achieves 89.4% latency reduction. This discrepancy occurs because actual token generation requires essential preprocessing time for embedding image-text data and feeding it to the model. This fixed overhead—independent of output length—includes vision encoder processing of the 336 × 336 input image into visual tokens and multimodal feature alignment. Despite this overhead, Level 1’s 5.7-s latency enables critical risk assessment and navigation action decisions within an acceptable timeframe for maritime collision avoidance, which typically operates on timescales of tens of seconds to minutes. Level 2’s 14.5-s latency is suitable for providing explainable decisions to human operators, while Level 3’s 30-s latency enables comprehensive situational awareness when time permits. These measurements validate the system’s practical feasibility for real-time onboard maritime deployment on resource-constrained edge platforms.

6. Conclusions

This study proposed an integrated inference framework based on vision–language for intelligent navigation safety support in maritime environments, capable of evaluating of hazardous situations and deriving appropriate navigation actions. The proposed technique is distinguished from existing approaches by its ability to simultaneously provide risk level prediction, navigation action recommendation, and explicit reasoning for each decision. Both input and output were defined in structured tag format, greatly improving model response consistency, parsing ease, and system integration possibility. The input prompt is largely composed of role definition, current situation information, analysis requirements, output format definition, consistency rules, and prior examples, with each element designed to conform to the actual context of ship navigation. The output format also proposed structured tag-based expression. The hierarchical structure enables clear separation of information, with each item being stably parsable.

Through performance evaluation results, The proposed Few-shot Reasoning LLaVA configuration achieved the best performance in all evaluation metrics by presenting multiple examples during training and including reasoning during inference. Reasoning performs effects beyond merely providing explanation, inducing the model to clearly organize its judgment process and internally form logical bases. This Chain-of-Thought-based reasoning system provides both interpretability and judgment consistency, which are difficult for general classification models to have.

Moreover, the proposed structured tag format performs functions beyond simple expression format. Early stopping mechanism is possible focused on hierarchical delimiters (&, @, ]), enabling token optimization according to situations, such as quickly extracting only judgment, including reasoning, or including complete object information depending on response information density. In actual analysis, the same information could be conveyed with on average less than half the tokens compared to natural language expression, becoming the technical foundation enabling real-time inference in edge computing environments such as Jetson Orin AGX.

The comprehensive contributions of this study are summarized as follows: First, it enabled precise situational awareness in maritime environments through structured tag-based input and output prompts. Second, it expanded inference on risk level and navigation action not as a simple prediction but as an explainable reasoning-based output, securing user trust and providing output directly usable in application systems. Third, it proposed a technique satisfying both real-time performance and automation possibility through structured tag output-based token optimization.