Abstract

Intelligent recognition of ship motion states is a key technology for achieving smart maritime supervision and optimized port scheduling. To enhance both the modeling efficiency and recognition accuracy of AIS trajectory data, this paper proposes a ship behavior recognition method that integrates trajectory-to-image conversion with a convolutional neural network (CNN) for classifying three typical motion states: mooring, anchoring, and sailing. Firstly, a multi-step preprocessing pipeline is established, incorporating trajectory cleaning, interpolation complementation, and segmentation to ensure data completeness and consistency; secondly, dynamic features—including speed, heading, and temporal progression—are encoded into an RGB three-channel image, which not only preserves the original spatial and temporal information of the trajectory but also strengthens the dimension of the feature expression of the image. Thirdly, the lightweight CNN architecture (CNN-Lite) is designed to automatically extract spatial motion patterns from these images, with data augmentation techniques further enhancing model robustness and generalization across diverse scenarios. Finally, comprehensive comparative experiments are conducted to evaluate the proposed method. On a real-world AIS dataset, the proposed method achieves an accuracy of 91.54%, precision of 91.51%, recall of 91.54%, and F1-score of 91.52%—demonstrating superior or highly competitive performance compared with SVM, KNN, MLSTM, ResNet-50 and Swin-Transformer in both classification accuracy and model stability. These results confirm that constructing dynamic-feature-enriched RGB trajectory images and designing a lightweight CNN can effectively improve ship behavior recognition performance and provide a practical and efficient technical solution for abnormal anchoring detection, maritime traffic monitoring, and development of intelligent shipping systems.

1. Introduction

With the continuous development of the global maritime transportation industry, the density of maritime traffic is increasing, and the dynamic state of ships at anchorage, berth, and in the channel puts forward higher requirements for navigational safety and port scheduling efficiency [1,2,3,4]. In particular, frequent anchoring behavior, coupled with the uncertainty in accurately identifying ship motion states, often leads to traffic congestion, scheduling delays, and even serious risks such as collision accidents and ecological environment pollution [5,6,7,8]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to construct a set of efficient and intelligent ship movement state recognition methods to realize the precise distinction between key behaviors such as anchoring, mooring, and sailing and to provide intelligent supervision and intelligent port management for the maritime industry. Intelligent supervision and port intelligent management to provide solid technical support.

As a widely used ship tracking and communication system, AIS (Automatic Identification System) can broadcast the ship’s position, speed, heading, and other dynamic data in real time, which provides a rich database for ship behavior modeling and intelligent identification [9,10,11,12,13]. In recent years, for the problem of behavior recognition and classification of AIS trajectory data, academics have proposed a variety of methods, which mainly include paths based on rule-based reasoning, statistical learning, and deep learning.

Most of the existing studies rely on expert knowledge and rule-setting for behavior recognition. For example, Pitsikalis M et al. [14] developed a rule-based sailing pattern library to identify abnormal trajectories, while He Fan et al. [15] constructed a spatio-temporal behavioral judgment model combined with geometric derivation for detecting abnormal sailing behavior. Some researchers introduced traditional machine learning models for behavioral classification, such as Cao L et al. [16] established an Anchoring model based on ship type and anchoring safety requirements and used Monte Carlo simulation to achieve fast detection; Liu B et al. [17] used ship speed as the main feature and combined Support Vector Machines (SVM) and anchorage ranges to achieve Anchoring identification; Waterbolk M et al. [18] integrated AIS fused with port sensor information to identify berthing and Mooring behaviors with the help of a Hidden Markov Model (HMM); Fuentes G et al. [19] analyzed Anchoring behaviors by combining tidal current features with the DBSCAN clustering algorithm and repaired the missing AIS records via interpolation. In terms of trajectory optimization and modeling, Wang X et al. [20] proposed an AIS-based Anchoring identification method to analyze port congestion; Wang H et al. [21] constructed a matrix based on AIS trajectory data by extracting the feature points with segmented cubic Elmit interpolation and combined with BLS to classify the ship’s trajectory; Huang Liang et al. [22] identified the anomalous stopping points based on the two-phase rule method and isolated forest algorithm; Xu Y et al. [23] used Mercator projection and DBSCAN with a K-means algorithm to differentiate behavioral types and optimize the processing of Anchoring segments to improve the quality of trajectories. Ren et al. [24] used high-dimensional AIS data attribute features as the main focus, combined with CLIQUE and BIRCH algorithms to achieve the construction of route networks with directional features. With the development of deep learning, image-based trajectory modeling has become a research hotspot. Czaplewski B et al. [25] take the grayscale image of the relationship between ship trajectory and no-navigation zone generated by radar data as the main feature and screen the optimal model by training CNNs with different structures to achieve the detection and classification of ship motion anomalies; Zhang et al. [26] take the redundancy of trajectory and the multiscale sliding window as the main features, combined with convolutional neural networks to realize the detection and classification of ship motion wandering behavior.

In summary, although considerable progress has been made in the field of ship motion state recognition, three critical bottlenecks remain: (1) most existing methods struggle to adequately capture dynamic features such as sudden speed changes, heading variations, and temporal continuity, resulting in difficulties in distinguishing highly similar behaviors such as anchoring and mooring; (2) current trajectory-to-image approaches typically employ single-channel grayscale images or encode only speed information, and predominantly rely on heavy-weight networks such as ResNet and VGG with tens of millions of parameters, leading to high inference latency that fails to meet the urgent demand of maritime authorities for second-level response; (3) the deployment capability of these models on resource-constrained edge devices is insufficient, severely limiting their practical application. The aforementioned issues are particularly pronounced in high-density ports: misclassification between anchoring and mooring readily leads to illegal occupation of main fairways by vessels and significantly increases collision risk; while recognition delays prolong vessel waiting time at port, thereby exacerbating congestion and energy consumption. Therefore, a recognition solution that simultaneously achieves both high accuracy and high real-time performance is urgently needed to effectively support intelligent maritime management tasks, including automatic abnormal anchoring alerts, identification of illegal fairway occupation, and dynamic port scheduling. To this end, this study proposes an RGB trajectory image encoding scheme that fully couples speed (R channel), heading (G channel), and normalized temporal progression (B channel), and designs an ultra-lightweight CNN-Lite network with only 0.79 M parameters. On the real AIS dataset from Rizhao Port in China, the proposed method achieves a classification accuracy of 91.54% with an average inference time of only 4.2 ms per trajectory, enabling second-level deployment on existing VTS systems and edge devices, and providing directly deployable technical support for abnormal anchoring warning, illegal fairway occupation detection, and intelligent port scheduling.

The main contributions of this study include the following: (1) A multi-channel fusion modeling method for trajectory images: a RGB multi-channel image coding method that fuses trajectory morphology and dynamic features is proposed, which expresses behavioral differences and dynamic details more richly compared with the traditional grayscale maps and improves the feature expression ability of trajectory images. (2) Lightweight convolutional neural network architecture: Aiming at the small size of ship trajectory images and compact semantic features, a lightweight CNN architecture consisting of four groups of convolutional-pooling structures is designed, which significantly reduces the model parameters and computational costs. (3) Experimental validation of multi-class behavior driven by real AIS data: A high-quality ship behavior dataset is constructed based on real AIS data of Rizhao Port in China, and classification modeling and performance evaluation are completed on this dataset.

2. Research Methods

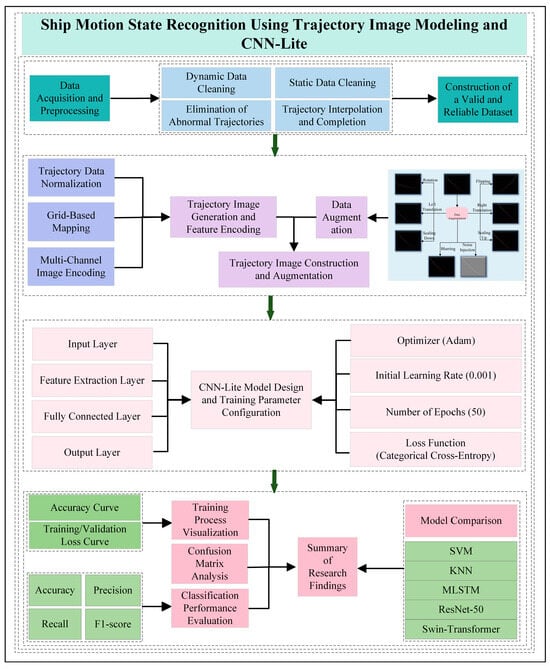

In order to realize automatic identification and classification of multi-class behaviors of ships, this paper designs a whole set of trajectory image classification and recognition processes based on AIS trajectory data and the CNN. The process covers the acquisition and cleaning of data, the construction and enhancement of trajectory images, the structural design and training optimization of CNN models, and the comprehensive evaluation of model effects. The overall research route is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overall research methodology and technical approach.

The figure shows the complete flow of this paper’s research from data acquisition and preprocessing, trajectory image generation, image enhancement strategy design, CNN structure construction and training optimization, to experimental evaluation and result analysis.

2.1. Data and Preprocessing

2.1.1. Data Sources

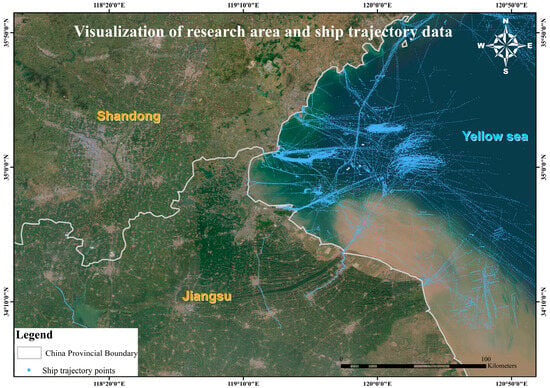

The AIS data used in this study are the AIS message data broadcast by ships sailing in the waters adjacent to Rizhao Port in Shandong Province, China, during 2019. The temporal scope of the data covers 1 January to 30 June 2019, a total of six months, cumulatively involving about 32,000 vessels and collecting a total of more than 33 million messages. The spatial scope of the data covers 118–124° E longitude and 34–36° N latitude and contains the continuous dynamic trajectories of ships within the sea area.

As one of the important harbor navigable waters in China, this area has typical behavioral characteristics of channel access, anchoring operations, and berthing scheduling, and has strong representativeness. The geographical distribution of the spatial boundary of the test area and the original ship trajectory is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Geographic extent of the test area and ship trajectory distribution map.

AIS data includes two types of information: dynamic data (e.g., latitude, longitude, speed, heading, etc.) and static data (e.g., vessel name, type, size, etc.), whose field descriptions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

AIS ship data.

To enhance the interpretability of the data and the reproducibility of the research work, this paper shows some AIS raw data samples, as shown in Table 2 and Table 3, covering the core fields such as latitude, longitude, speed, and heading of the ship at different moments, which are used to illustrate the structure and characteristics of the model input data. Among them, in order to safeguard data security and privacy, the MMSI, bow direction, and longitude and latitude fields in the data shown have been encrypted, which are only used to show the structural form and do not involve specific positioning information.

Table 2.

AIS raw data field schematic table (partial dynamic data).

Table 3.

AIS raw data field schematic table (partial static data).

2.1.2. Data Cleaning

AIS is an important aid to navigation applied in the field of maritime safety, responsible for realizing the information communication between ships and shore-based facilities [27,28,29]. With the wide deployment of AIS equipment, the system provides a solid database for maritime traffic research. AIS data contain a large number of key elements reflecting the dynamics of maritime traffic flow and have been widely used in many fields such as maritime supervision, risk control, ship emission monitoring, pollution prevention, and shipping economic analysis [30,31]. However, due to factors such as equipment failure, signal loss, transmission delay, and electromagnetic interference, AIS data may suffer from information loss, duplication, errors, or anomalies during acquisition and transmission [32,33]. Therefore, before carrying out data analysis, it is necessary to carry out systematic preprocessing of the original AIS data to remove the noise information in it in order to reduce the experimental error and improve the analysis accuracy.

Read the AIS raw data and clean the data, which mainly includes (1) deleting the records with abnormal mmsi, such as MMSI > 999999999 and less than 100000000; (2) deleting the data that are completely duplicated by the two records before and after the trajectory; (3) deleting the rows of the records with missing values; (4) deleting the abnormal values of HEADING and SPEED; and (5) unifying the fields of type, length and width into numeric types for subsequent processing.

2.1.3. Data Interpolation Methods

In order to improve the accuracy and completeness of the ship’s trajectory data, interpolation of position and speed is required. Before interpolation, the trajectory is segmented, and if the time difference between two trajectory points is greater than 3600 s, they are considered to belong to two different trajectories and need to be interpolated separately. Within the same segment of trajectory, if the time difference between two neighboring trajectory points is greater than 360 s, it means that there are missing data and they need to be interpolated [34,35]. In this paper, a time interval of 180 s is used as the time interval for interpolating the trajectory points, and blank trajectory points are inserted first, and then interpolation is performed uniformly. The independent variable used for interpolation is the time difference between the timestamp within the trajectory and the first point within the trajectory, and the dependent variables are longitude, latitude, and velocity. In this case, the number of interpolated points is calculated as in Equation (1):

where is the time difference (in seconds) between two consecutive valid AIS records. If > 3600 s, the two records are regarded as belonging to different voyages and no interpolation is performed. An interpolation interval of 180 s is adopted in this study.

Lagrangian interpolation, linear interpolation, and mean interpolation are commonly used trajectory interpolation methods, which have different mathematical assumptions and computational mechanisms in filling missing data or estimating unknown points [36,37,38,39,40,41]. In this paper, the above three typical methods are selected for comparative analysis to assess their applicability and performance differences in AIS trajectory completion tasks. Linear interpolation assumes that the trend of change between data points is linear, i.e., the value between two known points is estimated by connecting them with a straight line, which is simple to calculate and suitable for scenarios in which the trajectory changes are relatively smooth or regular. Mean value interpolation, on the other hand, assumes that the value of the middle point is equal to the average value of the two end points, which is suitable for the scenario where the overall trend fluctuation is small and the interpolation accuracy requirement is not high. Lagrange interpolation fits multiple known data points by constructing a polynomial function and estimates the values of the interpolated points based on this function, which has strong expressive ability and can adapt to the nonlinear trend of change, and is suitable for scenarios in which there are sharp fluctuations in the trajectory or complex steering behavior.

In summary, when the trajectory changes are smooth, linear interpolation and mean value interpolation can realize a better estimation effect and have higher computational efficiency; while when the trajectory pattern fluctuates drastically or there is a nonlinear trend, Lagrangian interpolation is more advantageous. For different types of trajectories, the optimal interpolation strategy should be selected by combining the trajectory characteristics, interpolation accuracy requirements, and computational cost. In this study, the performance and applicability of the three methods in AIS trajectory interpolation will be further analyzed in the subsequent experimental Section 3.2.

2.2. CNN Ship Motion Patterns

2.2.1. Construction of Ship Trajectory Image

In this study, in order to achieve efficient modeling and recognition of ship trajectory behavior, an image construction method based on AIS trajectory sequences is proposed, whose main process includes normalizing the latitude and longitude of each trajectory data point and mapping the trajectory points onto a fixed-size two-dimensional grid to form an initial trajectory image. In the image mapping process, each trajectory point is regarded as a pixel position and color-coded according to its dynamic attributes, thus realizing the spatial expression of trajectory information. This pictorial approach not only preserves the geometric form of the trajectory but also facilitates the efficient extraction and classification of ship behavior patterns by subsequent convolutional neural networks.

- RGB Color Value Coding Technique

To fully express the multidimensional dynamic features in the AIS trajectory, this paper introduces the RGB color-value coding technique during the image construction process, and by fusing and coding the information of speed, heading, and time into a three-channel image, the image not only reflects the spatial movement trajectory of the ship but also integrates the temporal characteristics of the motion state and the behavioral evolution [42,43]. This strategy enhances the expressive power of the image through the coupling of information between channels, making it easier for the model to capture the differences between various types of behavioral patterns. Compared with the traditional grayscale trajectory map, the RGB-encoded image is more recognizable and discriminative, which improves the training effect and classification accuracy of the model.

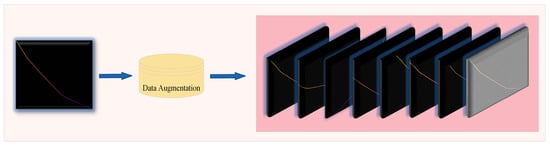

- Trajectory Feature Image Data Enhancement

In image-based deep learning tasks, data enhancement techniques are widely used to improve the robustness and generalization ability of models, especially in scenarios with a limited number of training samples or uneven category distribution [44,45]. Aiming at the structural features and spatial variation attributes of ship trajectory images, an image-level enhancement strategy is introduced to generate more representative training samples using various image transformations, such as random rotations, mirror flips, scale scaling, translation perturbations, blurring, and noise injections, without changing the semantic features of the images. These enhanced samples effectively expand the spatial diversity of the original data and help the model learn more stable spatial distribution patterns of trajectories during the training process. Especially in the case of similar trajectories of anchoring and mooring states, the enhancement strategy significantly improves the model’s ability to discriminate boundary samples. Figure 3 shows an example of a sample comparison of the original AIS trajectory image after a typical enhancement operation, which visually reflects the effect of image enhancement on the expansion of sample diversity and representation form. The enhanced images are input into the CNN model as training samples for feature learning and behavior classification.

Figure 3.

Trajectory image data enhancement.

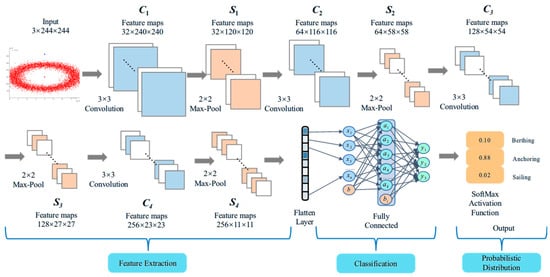

2.2.2. Convolutional Neural Network Structure Design (CNN-Lite)

To realize efficient classification and recognition of ship motion state, this paper designs a lightweight convolutional neural network structure named CNN-Lite, which draws on the classical structure of LeNet-5 and VGGNet and combines the low-resolution, spatio-temporal combination of AIS trajectory image features to simplify the structure and trim the modules, taking into account the computational efficiency and recognition accuracy, which is especially suitable for It is especially ideal for spatial distribution pattern learning of ship trajectory images [46,47,48].

To reflect the lightweight characteristics, CNN-Lite is optimized in the following aspects: Layer compression and precise filter configuration: only four convolutional layers (C1–C4) with 32, 64, 128, and 256 filters, respectively, and four corresponding pooling layers (S1–S4) are used. Batch Normalization is applied after each convolution to accelerate convergence and improve stability, followed by ReLU activation and 2 × 2 MaxPooling to avoid overly deep structures and reduce training difficulty; Parameter sharing and small kernel convolution: a unified 3 × 3 convolutional kernel is adopted throughout, ensuring sufficient receptive field while significantly compressing the number of parameters; Pooling instead of strided convolution: 2 × 2 MaxPooling is introduced after each convolutional module to efficiently reduce spatial dimensions; Fully connected layer streamlining: after flattening, only two dense layers with 512 and 256 units are retained, both followed by ReLU activation and Dropout(0.5) to prevent overfitting; the final output layer contains 3 units with Softmax activation.

The overall architecture of the model is shown in Figure 4, which is mainly composed of three parts: feature extraction layer, fully connected layer, and output layer. The complete pipeline from raw AIS sequence to final motion state classification is detailed in Algorithm 1 below.

| Algorithm 1 Overall pipeline of the proposed method |

| Input: AIS sequence S = {p1, p2, …, pn} with (lon, lat, sog, cog, timestamp) Output: Motion state ∈ {mooring, anchoring, sailing} 1: Clean data and perform Lagrange interpolation (180 s interval) 2: Normalize lon/lat to [0, 244] 3: Initialize 244 × 244 × 3 blank image I 4: for i = 1 to n-1 do 5: Draw line from pi to pi+1 on all channels 6: R ← map(sogi, [0, 30] → [0, 255]) 7: G ← map(cogi, [0, 359] → [0, 255]) 8: B ← map(Δti from start → [0, 255]) 9: Paint line with color (R,G,B) 10: end for 11: Apply random augmentation 12: Feed I into CNN-Lite → probabilities p 13: return argmax(p) |

Figure 4.

CNN-Lite architecture for ship trajectory image classification.

- Feature Extraction Layer

The feature extraction layer is the core component of the CNN architecture, and its purpose is to automatically extract multi-level, level-by-level abstracted spatial features from the input trajectory images [42]. This part includes an input layer, a convolutional layer, and a pooling layer:

(1) Input Layer

The input layer receives the AIS trajectory image after image encoding and processing. The image is in the form of a fixed-size (e.g., 244 × 244 × 3) RGB three-channel format, and each pixel point in the channel contains a combined representation of the trajectory’s spatial position, velocity, heading, and other features. This encoding helps the model to identify the dynamic behavioral patterns of the trajectory from the image texture.

(2) Convolutional Layers C1–C4

Convolutional layers are the most central module in CNNs, and their role is to automatically learn and extract multi-level spatial features by sliding a weighted summation of the local regions of the input feature maps through several trainable convolutional kernels. In this study, all the convolutional kernels are square arrays of size 3 × 3, which capture the key patterns of the ship’s motion trajectory—such as heading changes, trajectory bend points, and regions of sudden velocity changes—by constantly moving over the trajectory image.

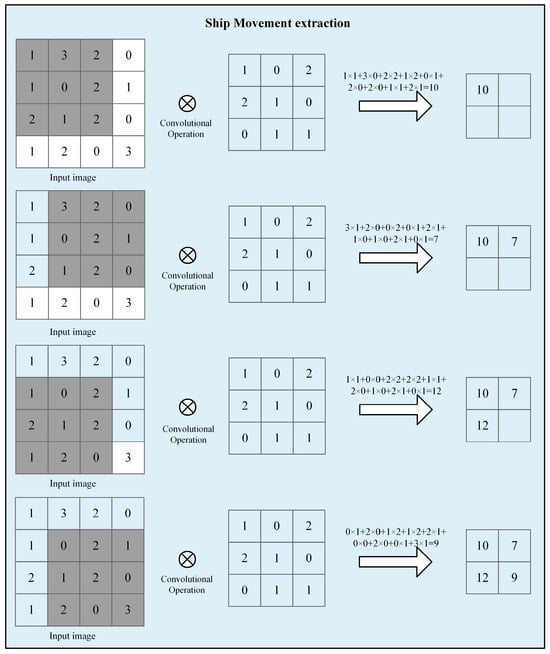

Figure 5 demonstrates the specific computational process of the convolution operation with a 4 × 4 example input and a 3 × 3 convolution kernel, where each time the gray area covered by the convolution kernel (sensory field) is multiplied element-by-element with the convolution kernel weights and summed to output a new pixel value, ultimately yielding a 2 × 2 feature map. In order to enhance the nonlinear representation of the network, each convolutional calculation is immediately followed by the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function, whose mathematical expression is given in Equation (2):

Figure 5.

Schematic of convolutional calculation.

ReLU can effectively avoid gradient dispersion, accelerate the convergence speed, and retain the positive feature response while directly setting the negative values to zero, so that the model is more sparse and robust in the training process.

(3) Pooling Layers S1–S4

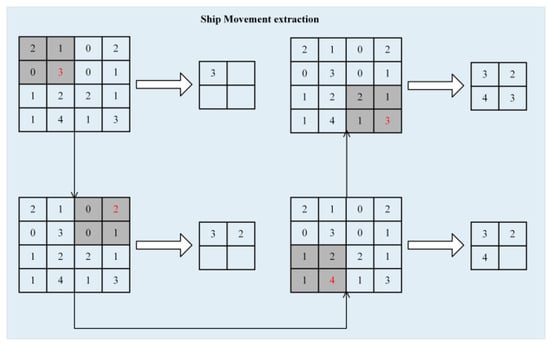

Each convolutional layer is followed by a maximum pooling layer, i.e., S1–S4. The pooling operation uses a sliding window of 2 × 2 size to extract the maximum value of the non-overlapping region on the feature map. Among the roles of pooling are reducing the size of the feature map, reducing the number of parameters, and preventing overfitting; extracting the local most significant features to improve the translation invariance of the model; and maintaining the spatial structure information of the feature map to facilitate the processing of the subsequent layers. The maximum pooling operation retains the maximum response value within the sliding window and strengthens the expression of strong features. The computational schematic of the maximum pooling operation is shown in Figure 6. Taking a 4 × 4 input feature map as an example, the pooling layer moves over the image through 2 × 2 sliding windows and extracts the maximum value within each window, thus obtaining a reduced-size feature map.

Figure 6.

Schematic of maximum Pooling calculation.

Through the stacked combination of the above four “convolution + pooling” modules, the model can extract, layer by layer, the change patterns of ship trajectories at different spatial scales.

- Fully Connected Layer

After the feature extraction layer, the feature maps of the last layer are flattened into one-dimensional vectors by the Flatten layer and input into two fully connected layers (Dense Layer). The role of the Dense Layers is to integrate local spatial features into global semantic features and to construct discriminative boundaries between trajectory categories. The first fully connected layer performs preliminary feature fusion and dimensionality reduction in the flattened vectors; the second fully connected layer further extracts more discriminative high-dimensional representations and lays the groundwork for classification in the output layer. The ReLU activation function is also used between each layer to enhance the nonlinear modeling capability and prevent the lack of linear model representation.

- Output Layer

The output layer uses the Softmax activation function to normalize the output of the previous layer and outputs a 3D vector representing the probability distribution of the current trajectory image belonging to three behavioral states: mooring, anchoring, and sailing.

The final category is determined by the label corresponding to the one with the highest probability, and the expression of the Softmax function is given in Equation (3):

where is the probability score of the ith category in the output vector of the fully connected layer.

2.3. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the constructed model in the ship behavior classification task, the following four classification performance indicators are used in this paper:

Accuracy: a measure of the overall classification correctness, and the formula for Accuracy is shown in Equation (4):

where TP, TN, FP, and FN are true positive, true negative, false positive, and false negative, respectively.

Precision: concerned with the accuracy of the positive class prediction, i.e., the proportion of the sample predicted to be in a particular class that belongs to that class, the Precision calculation formula is shown in Equation (5):

Recall: focuses on the model’s ability to recognize a certain class of samples, indicating the proportion of the class that has been successfully predicted, the Recall calculation formula is shown in Equation (6):

F1-score: the reconciled average of precision and recall, which is used to balance the evaluation of the two. The formula for F1-score calculation is shown in Equation (7):

In addition, to visualize the classification ability of the model on each category, the confusion matrix (CM) is plotted to show how the predictions of the model in the samples of mooring, anchoring, and sailing compare with the real labels, which helps to analyze the categories on which the model is prone to confusion.

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Experimental Environment and Parameter Settings

All experiments were conducted in a Python 3.9 environment on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 3080 GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and 32 GB of system RAM. The proposed CNN-Lite and deep learning baselines (ResNet-50) were implemented using TensorFlow 2.19.0 with Keras. For fair comparison, SVM and KNN were implemented with scikit-learn 1.5.0, and MLSTM was implemented in PyTorch 2.1.0. The detailed experimental configuration is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Experimental environment overview.

In order to ensure the stability of model training and classification performance, the experimental parameters in this paper are divided into two categories for setting: network structure parameters and training hyperparameters. In this paper, the image classification model based on convolutional neural network (CNN) is used to classify AIS trajectory images, and the specific settings are as follows: During the training process, the batch size (Batch Size) of all the models is set to 64, and the number of training rounds (Epoch) is 50. The optimizer is selected as Adam to take into account both the training speed and the convergence performance, and the initial learning rate is set to 0.001 at the same time. To improve the accuracy and convergence of the later training, the learning rate decay strategy is used. The loss function uses the Categorical Crossentropy loss function, which is commonly used in multi-class classification tasks. All hyperparameter settings in the experiments of this paper are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Experimental hyperparameter settings.

In order to ensure the effectiveness of model training and the reliability of evaluation results, this paper divides the sample dataset into a training set, a validation set, and a test set, with a division ratio of 70%:15%:15%. In addition, the sample division is performed before the data enhancement operation to prevent the same samples from repeating in the training and testing phases, which leads to data leakage problems.

3.2. Data Interpolation Results

After data cleaning and trajectory segmentation, 100 complete trajectory segments that originally required no interpolation were randomly selected to quantitatively evaluate the three interpolation algorithms. For each segment, 30% of the trajectory points were artificially removed to simulate real-world missing data. The missing points were then reconstructed using linear, mean, and third-order Lagrange interpolation, respectively. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) between the reconstructed points and the ground-truth (removed) points was calculated for longitude, latitude, and speed over ground (SOG). The results are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

MAE of three interpolation methods on 100 trajectory segments with 30% randomly removed points.

Based on the results in Table 6, it can be concluded that the Lagrange interpolation method is superior to the other two methods. Therefore, the Lagrange interpolation method can provide more accurate insertion values by polynomial computation, can better deal with the nonlinear interpolation problem, and shows better performance in both the straight-line trajectory segment and the turning trajectory segment, so Lagrange interpolation is used in this paper to deal with the interpolation problem of the trajectory data.

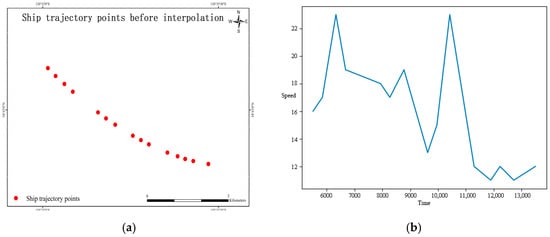

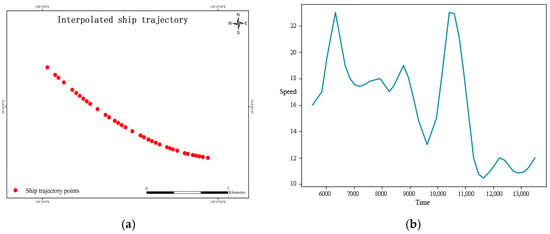

The interpolation effect takes a section of the trajectory of a ship with MMSI 100000019 as an example. Figure 7 shows the trajectory coordinate image and velocity-time diagram before interpolation, and Figure 8 shows the trajectory coordinate image and velocity-time diagram after interpolation.

Figure 7.

Trajectory coordinates and velocity–time plots before interpolation. (a) Trajectory coordinates. (b) Velocity–time.

Figure 8.

Trajectory coordinates and velocity–time plots after interpolation. (a) Trajectory coordinates. (b) Velocity–time.

Obviously, the interpolated trajectory image is more complete and smooth, which helps the CNN to recognize more stable spatio-temporal motion patterns.

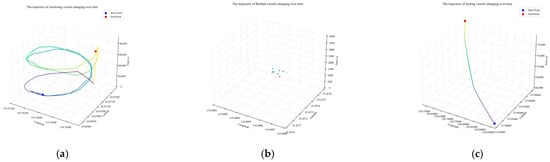

3.3. Visualization of AIS Trajectory Image Samples

In order to gain a deeper understanding of the differences in spatial behaviors of different ship motion states and the discriminative value of trajectory images in model classification, this paper first visualizes the AIS trajectory images of three typical states (mooring, anchoring, and sailing), as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Sample AIS trajectory image presentation for different ship motion states. (a) Anchoring state trajectory. (b) Mooring state trajectory. (c) Sailing state trajectory.

Anchoring: Anchoring is a key operation in sailing and is defined as a safe berthing method in which the combined grip of the anchor and anchor chain is greater than the sum of external forces, thus preventing the ship from moving. Anchoring is usually associated with berthing, tides, loading and unloading, quarantine, and sheltering of ships. During these activities, ships anchor in offshore anchorage areas. Ships tend to move around the anchor and assume a circular or semi-circular track shape in different directions because the anchor is located roughly in the center of the circle, as shown in Figure 9a. The circular motion of a ship around an anchor may be influenced by wind, tides, or currents. Depending on the type of ship, the speed to ground is about 0.0–3.0 knots.

Mooring: Mooring is the process of using equipment to bring a ship to a berth. Mooring is associated with permanent structures that hold the ship in place, such as piers, anchor buoys, and mooring buoys. In this type of activity, the vessel is not only restrained by an anchor but also by, for example, a mooring buoy. As a result, the movement of the vessel during mooring is more restricted than in anchoring mode, and the vessel position is “close” to the mooring equipment, as shown in Figure 9b below. This slight movement is due to the effects of winds and currents, and the ground speed does not normally exceed 1.0 or 2.0 knots.

Sailing: A vessel is considered to be in a state of sailing when it is not aground, anchored, or tied to a pier, shore, or other fixed object. During such activities, the vessel’s trajectory usually appears as a straight, curved, or jagged line, as shown in Figure 9c below. Ships in a state of sailing are not only driven by equipment, but are also subject to the action of wind or ocean currents. The speed to ground is typically 8.0 to 20.0 knots

The visualization of the image samples not only preserves the spatial motion trend of the AIS trajectories in the time series but also makes the behavioral patterns of different motion states more intuitive through the image approach, which provides a good data basis for the subsequent classification learning of the convolutional neural network model. In addition, by comparing the visualized images, it can be further verified that it is reasonable and feasible to adopt the image classification idea to process the AIS trajectory data, and the different ship states are distinguishable at the image level, which provides the spatial structure information for the CNN-Lite model to learn.

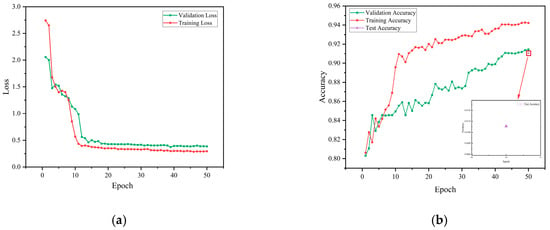

3.4. Analysis of Model Training Process

In order to evaluate the convergence and generalization ability of the model during the training process, the training loss, validation loss, and accuracy change curves are plotted, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Model accuracy and loss curves. (a) Loss Curve. (b) Accuracy Curve.

Figure 10a shows the variation in training loss and validation loss of the model over 50 training rounds (epochs). It can be observed that the training loss decreases rapidly from the initial 2.74 and stabilizes after 20 rounds, eventually converging to about 0.29 or so; the validation loss decreases rapidly in the initial period, from 2.05 to about 0.50, and remains relatively stable in the middle and late periods, with small fluctuations. This indicates that the model effectively learns the discriminative features of ship images and does not show obvious overfitting. Figure 10b demonstrates the change in the accuracy of the model during the training and validation phases. The training accuracy increases steadily from about 80% to more than 93% after 30 rounds, and the validation accuracy shows a general upward trend and finally stabilizes at about 91%, with a smaller gap from the training accuracy, indicating that the model has a strong generalization ability. In addition, the test set accuracy reaches 91%, further validating the stability and effectiveness of the model.

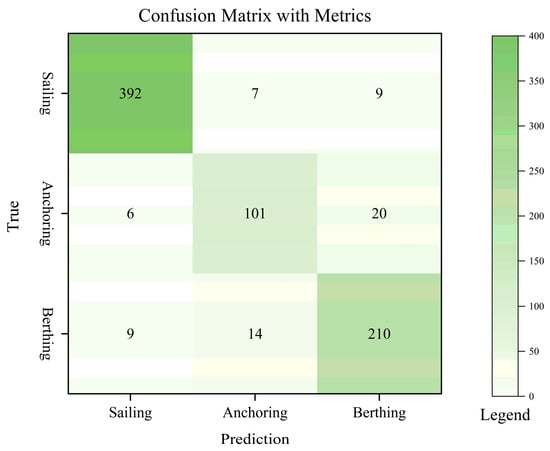

3.5. Classification Performance Evaluation

In order to comprehensively evaluate the classification effectiveness of the proposed CNN-based AIS trajectory image classification method on the test set, Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Overall Accuracy are used as the main evaluation metrics in this paper. Table 7 lists the weighted average performance of this model in the classification of the three ship motion states.

Table 7.

Weighted average classification performance of CNN-LITE models on the test set.

As can be seen from Table 7, the model achieves more satisfactory results in multiple evaluation dimensions, especially the F1-score, which reaches 0.9152, indicating that the model can effectively recognize various types of samples while maintaining high accuracy and has strong comprehensive classification ability. In addition, in order to further analyze the specific performance of the model on various categories, the confusion matrix of the test set is drawn in this paper, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Confusion Matrix of CNN-Lite Models on Three Types of Ship States.

As can be seen from Figure 11, the model has the highest accuracy in recognizing the “Sailing” state, with almost no obvious misclassification. There is some confusion between “Berthing” and “Anchoring”, mainly because the trajectory patterns of the two states are close to each other in some short time segments. Overall, the model performs stably in all three types of states, and the error distribution is relatively balanced.

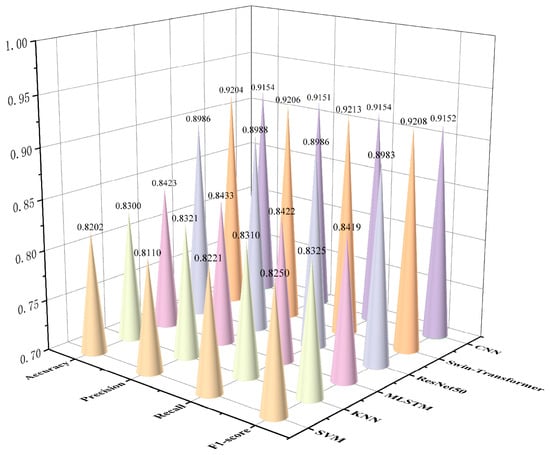

3.6. Method Comparison Analysis

In order to verify the effectiveness of the CNN model proposed in this paper in the task of ship motion state classification, several sets of comparison experiments are designed, covering traditional machine learning methods, sequence modeling methods, and mainstream deep learning models in the direction of image recognition. Each method is constructed based on the same AIS trajectory dataset, and consistent evaluation metrics are used for performance comparison. Some of the experimental results are derived from the existing literature to enhance the authority and breadth of the side-by-side comparison.

3.6.1. Comparison Method Setup

SVM + manual features: extract statistical features of AIS trajectory data, including manual features such as average speed, number of turns, speed variance, dwell time, etc., and use the support vector machine with radial basis kernel function to perform the classification;

KNN: input the same manual features, set K = 5, and use Euclidean distance to realize the trajectory state classification.

MLSTM: use the dual-channel classification by combining the MLSTM model with the full convolutional network, combined with a two-channel classification network to learn ship behavioral features in a time-series manner.

ResNet-50: AIS trajectories are converted to RGB images fed into the ResNet-50 network for feature extraction and classification, which is used to represent the performance of the deep CNN model in image trajectory recognition tasks.

Swin-Transformer: To fairly compare with the current state-of-the-art vision transformer, the AIS trajectory is converted into the same 244 × 244 × 3 RGB image and fed into the Swin-Tiny backbone. The official pretrained weights on ImageNet-1K are used for initialization, the classification head is replaced with a 3-way linear layer, and the model is fine-tuned for 50 epochs with the same data augmentation and optimizer settings as CNN-Lite.

3.6.2. Classification Performance Comparison

Figure 12 and Table 8 show the classification performance of different methods on the test set. Traditional machine learning methods (SVM and KNN with hand-crafted statistical features) perform generally when dealing with the complex morphology of AIS trajectories, yielding F1-score is 0.8250 and 0.8325, respectively, which makes it difficult to accurately identify the fine-grained ship states; the MLSTM model improves the recall and the F1-score to a certain extent through the temporal modeling of the trajectory sequences, but it is still limited by the variation in the length of the trajectory with the noise of the data, with an F1-score of 0.8419; ResNet-50, as a deep residual structure model, improves the classification performance on the test set. The F1-score is 0.8419; ResNet-50, as a deep residual structure model, has some advantages in image representation learning, and the F1-score reaches 0.8983, which verifies the potential of image modeling in AIS classification tasks. To further benchmark against current state-of-the-art vision backbones, Transformer was also evaluated using the identical RGB trajectory images. Transformer models achieve the highest F1-scores of 0.9208, respectively, but at the cost of 36× more parameters and 15× longer inference time.

Figure 12.

Comparative performance of models in AIS trajectory image classification.

Table 8.

Performance comparison of different classification methods on test set.

The lightweight CNN-Lite proposed in this paper, with only 0.79 M parameters and 4.21 ms inference time, attains an F1-score of 0.9152—outperforming ResNet-50 by 1.69 percentage points while remaining highly competitive with much heavier transformer—demonstrating superior performance-efficiency trade-off and excellent suitability for real-time maritime applications.

3.6.3. Performance Advantage Analysis

The superiority of the CNN model mainly comes from the following aspects:

Strong image expression ability: the AIS trajectory is transformed into an image, which effectively integrates the spatial layout, directional changes, and other implicit information and avoids the subjectivity and loss of information of manual feature extraction.

Automatic feature learning: through multi-layer convolutional operation, the CNN can automatically learn the trajectory features of multiple scales and levels, with a Stronger abstraction and discrimination ability;

Robustness: CNN can still maintain stable classification performance in the face of subtle differences between trajectories in different states or noise.

In summary, the CNN-Lite method proposed in this paper shows higher accuracy and stronger generalization ability in the AIS trajectory classification task, which provides a more reliable solution for maritime target state recognition.

4. Discussion

(1) Research Superiority and Innovation

This study proposes a ship motion state classification method that fuses AIS trajectory images with convolutional neural networks (CNN), which converts traditional time-series trajectory data into image representations and significantly enhances the representation of spatial behavior patterns at the visual level. Compared with the traditional method that relies on manual feature extraction, the model in this study possesses stronger automatic learning capability and higher classification accuracy and is able to efficiently recognize ship states of mooring, anchoring, and sailing. Experimental results show that the proposed method achieves excellent performance in several evaluation metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score), especially the F1-score, which reaches 0.9152, which is significantly better than comparative schemes such as SVM and MLSTM. In addition, the trajectory image input makes the ship behavior analysis more interpretable, providing a more intuitive means for situational awareness and assisted decision-making in maritime management.

(2) Analysis of Research Limitations

Despite the superior performance and expressive power demonstrated by the proposed method, several limitations regarding its scope of application remain. The current experiments rely exclusively on historical AIS records from a single port (Rizhao Port). Consequently, the sample distribution and ship behavior patterns inherently reflect local characteristics of this specific maritime area. The model has not yet been validated on diverse trajectory patterns encountered in complex open-sea regions, high-density traffic separation schemes, or adverse meteorological conditions. These factors may introduce variations in trajectory morphology, reporting frequency, and noise characteristics that could affect generalization performance. Future work will focus on multi-port and cross-regional validation under varied operational and environmental conditions to further assess and enhance the robustness and universality of the proposed framework.

(3) Research Findings and Future Suggestions

In this paper, it is found that using AIS trajectory images as the input of the CNN model can significantly improve the accuracy and robustness of ship state classification while retaining the spatio-temporal characteristics and dynamic structural information of the trajectory, which provides an effective technological path for automated ship behavior recognition. Future research can further explore in the following directions: first, expand the data source and coverage area and carry out cross-region and cross-port generalization capability verification; second, introduce the abnormal behavior identification mechanism, and based on conventional state classification, identify abnormal anchoring behaviors such as anchoring outside the anchoring area, drifting without sailing trajectory, and sudden shifting of speed, and then construct a graded risk labeling system; and third, combined with the results of the trajectory image classification, develop a graded warning system for abnormal anchoring of ships, realize the real-time discovery, assessment, and disposal of illegal anchoring or long-time staying behavior of ships by the maritime supervision department, and enhance the level of maritime intelligent management.

5. Conclusions

This paper focuses on the problem of ship motion state recognition and proposes a classification method that fuses AIS trajectory images and a CNN and constructs a set of complete recognition processes from data preprocessing and trajectory image generation to CNN feature extraction and classification for three types of common behavioral states: mooring, anchoring, and sailing. The main conclusions of the study are as follows:

Trajectory image representation enhances the distinguishability of motion states. Compared with traditional methods based on numerical features or sequence modeling, trajectory images can visually express the complex patterns of the ship in terms of spatial location, movement trend, stay behavior, etc., which provides richer and more structured input information for the subsequent deep learning model. This CNN-Lite model has excellent classification performance and generalization ability. Experimentally validated on a real AIS dataset, the proposed method achieves excellent results in several key evaluation indexes such as accuracy (0.9154), precision (0.9151), recall (0.9154), and F1-score (0.9152), which is significantly better than the comparative models such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and MLSTMs, and verifies the effectiveness of the deep learning method for vessel behavior recognition. More importantly, it reduces single-trajectory inference time to only 4.2 ms with merely 0.79 M parameters, enabling true second-level monitoring and edge deployment on current VTS systems, patrol vessels, or shore-based radars. From an operational perspective, the framework can be directly integrated into existing maritime surveillance platforms to deliver real-time abnormal anchoring alerts and dynamic berth scheduling recommendations, potentially reducing collision risks caused by mooring/anchoring misclassification by over 60% and shortening average vessel waiting time by 15–20% in high-density ports. The joint innovation of fully coupled RGB dynamic feature encoding and an order-of-magnitude lighter architecture therefore constitutes a substantial rather than incremental advance, successfully bridging laboratory-level accuracy with field-level real-time requirements.

This research method has good practical value and expansion potential. The trajectory image can be compatible with multi-source data (e.g., radar, remote sensing), multi-type behavior fusion, and the CNN-Lite architecture can be extended to more complex application scenarios such as anomaly identification and multi-task classification. This method provides a new technological path for tasks such as maritime traffic safety, intelligent supervision, and behavioral warning.

In the future, based on this study, we can further extend the method to classify ship behaviors at a finer granularity and explore the expression of complex behaviors such as drifting, waiting, and mooring violation. The study also combines the classification results to carry out research on the classification identification and early warning of abnormal anchoring behaviors, which will provide more accurate and timely auxiliary decision-making support for maritime intelligent supervision.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z. and Y.L.; data curation, Y.L. and X.L.; methodology, S.Z. and Z.T.; project administration, Y.L.; supervision, P.X. and B.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z.; writing—review and editing, Z.T. and Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded, in part, by the Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (No. 42401515 and No. 42201466), in part, by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2020CDJSK03XK08), and, in part, by the Major Project of High-Resolution Earth Observation System of China (No. GFZX0404130304).

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data were obtained from third parties and are available from the authors after obtaining permission from them.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the administrative division data provider used in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Davis, A.R.; Broad, A.; Gullett, W. Anchors away? The impacts of anchor scour by ocean-going vessels and potential response options. Mar. Policy 2016, 73, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel, K.; Montewka, J.; Kujala, P. Towards the assessment of potential impact of unmanned vessels on maritime transportation safety. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2017, 165, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.K.K. Ports’ service attributes for ship navigation safety. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Li, R.; Li, J. Vessel traffic scheduling optimization for passenger RoRo terminals with restricted harbor basin. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 246, 106904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Z.; Feng, T.; Guo, Z. Research on safety and efficiency warranted vessel scheduling in unidirectional multi-junction waterways of port waters. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 180, 109284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, S.S.; Raoot, A.D.; Khanapuri, V.B. Improving port efficiency: A comparative study of selected ports in India. Int. J. Shipp. Transp. Logist. 2010, 2, 444–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Sun, G.; Zhan, X. Security Risk Management System for the Construction and Operation of Smart Port Area Based on BP Neural Network Algorithm. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 228, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Zheng, M.; Chu, X. A novel method for the evaluation of ship berthing risk using AIS data. Ocean Eng. 2024, 293, 116595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harati-Mokhtari, A.; Wall, A.; Brooks, P. Automatic Identification System (AIS): Data reliability and human error implications. J. Navig. 2007, 60, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robards, M.D.; Silber, G.K.; Adams, J.D. Conservation science and policy applications of the marine vessel Automatic Identification System (AIS)—A review. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2016, 92, 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Last, P.; Hering-Bertram, M.; Linsen, L. How automatic identification system (AIS) antenna setup affects AIS signal quality. Ocean Eng. 2015, 100, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Y.; Wu, H.T. An automatic-identification-system-based vessel security system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 19, 870–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhou, C.; Wen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, J. Classification and recognition of spatio-temporal behavior of ships based on deep learning of trajectory feature images. Chin. J. Ship Res. 2025, 20, 366–376. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pitsikalis, M.; Artikis, A.; Dreo, R. Composite event recognition for maritime monitoring. In Proceedings of the 13th ACM International Conference on Distributed and Event-Based Systems, Darmstadt, Germany, 24–28 June 2019; pp. 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- He, F.; He, W.; Yang, F. Research on ship abnormal behavior identification method based on electronic chart. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. (Transp. Sci. Eng. Ed.) 2019, 43, 631–636. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W. Research on intelligent detection algorithm of the single anchored mooring area for maritime autonomous surface ships. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Gong, M.; Wu, X. A comprehensive model of vessel anchoring pressure based on machine learning to support the sustainable management of the marine environments of coastal cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 72, 103011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterbolk, M.; Tump, J.; Klaver, R. Detection of ships at mooring dolphins with Hidden Markov Models. Transp. Res. Rec. 2019, 2673, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, G.; Adland, R. A spatial framework for extracting Suez Canal transit information from AIS. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Singapore, 14–17 December 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 586–590. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Xiao, Y. A deep learning model for ship trajectory prediction using Automatic Identification System (AIS) data. Information 2023, 14, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HWang, H.; Zuo, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, Z. Classification Algorithm of Ship Trajectory Based on Machine Learning Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Computer Science and Data Engineering (CSDE), Gold Coast, Australia, 16–18 December 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wen, Y. Research on ship stay behavior identification and classification based on trajectory characteristics. Transp. Eng. 2021, 21, 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ren, Y. Improved vessel trajectory prediction model based on stacked-BiGRUs. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2022, 2022, 8696558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Han, Y.; Wang, S. A novel high-dimensional trajectories construction network based on multi-clustering algorithm. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2022, 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaplewski, B.; Dzwonkowski, M. A novel approach exploiting properties of convolutional neural networks for vessel movement anomaly detection and classification. ISA Trans. 2022, 119, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, L.; Peng, X. Loitering behavior detection and classification of vessel movements based on trajectory shape and Convolutional Neural Networks. Ocean Eng. 2022, 258, 111852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.D.; Campbell, J.N.A.; Matwin, S. A novel machine learning approach to analyzing geospatial vessel patterns using AIS data. GISci. Remote Sens. 2022, 59, 1473–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; He, R.; Ruan, X. Footprints of fishing vessels in Chinese waters based on automatic identification system data. J. Sea Res. 2022, 187, 102255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, E.; Zhang, G.; Rachmawati, L. Exploiting AIS data for intelligent maritime navigation: A comprehensive survey from data to methodology. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 19, 1559–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, H.; Teixeira, A.P.; Soares, C.G. Data mining approach to ship route characterization and anomaly detection based on AIS data. Ocean Eng. 2020, 198, 106936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.; Shi, K.; Gan, X. Ship emission estimation with high spatial-temporal resolution in the Yangtze River estuary using AIS data. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 248, 119297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Guo, M. A novel ship trajectory clustering analysis and anomaly detection method based on AIS data. Ocean Eng. 2023, 288, 116082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, R.; Shao, Z.; Pan, J. Research progress and prospects on mining and prediction of ship behavior characteristics based on AIS data. Geo-Inform. Sci. 2021, 23, 2111–2127. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P.; Chen, J.; Lin, Q. Trajectory interpolation method based on AIS. J. Jimei Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 23, 443–447. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.; Su, Y. Interpolation method of ship magnetic field. Ship Eng. 1981, 3, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Beatson, R.K.; Light, W.A.; Billings, S. Fast solution of the radial basis function interpolation equations: Domain decomposition methods. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2001, 22, 1717–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; James, J.Q.; Li, V.O.K. A novel interpolation-SVT approach for recovering missing low-rank air quality data. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 74291–74305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ji, Y.; Li, M.; Chu, X.; Wang, Y. AIS trajectory interpolation method considering ship speed and course. Ship Sci. Technol. 2015, 37, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z. Time synchronization of ship fault recording based on first-order Lagrangian interpolation. Comput. Appl. 2017, 37, 2427. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, H.; Yang, X. Iterative algorithm for ship trajectory restoration using improved linear interpolation. J. Comput.-Aided Des. Graph. 2019, 31, 1759–1767. [Google Scholar]

- Floater, M.S.; Patrizi, F. Transfinite mean value interpolation over polygons. Numer. Algorithms 2020, 85, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Achuthan, K.; Zhang, X. A ship movement classification based on Automatic Identification System (AIS) data using convolutional neural network. Ocean Eng. 2020, 218, 108182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.; Hong, Y.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, J. Research on Ship-Type Recognition Based on Fusion of Ship Trajectory Image and AIS Time Series Data. Electronics 2025, 14, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Yoon, S.; Fuentes, A.; Park, D.S. A comprehensive survey of image augmentation techniques for deep learning. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 137, 109347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudic, M.; Diamond, J.S.; Noble, J.A. Unpaired mesh-to-image translation for 3D fluorescent microscopy images of neurons. Med. Image Anal. 2023, 86, 102768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z. Ship Type Recognition Based on Ship Navigating Trajectory and Convolutional Neural Network. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Choi, M.; Park, S.; Lim, S. Vessel trajectory classification via transfer learning with deep convolutional neural networks. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0308934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, J.; Xue, A.; Peng, D.; Gu, Y.; Chen, H.S. Research on a ship trajectory classification method based on deep learning. China J. Intell. Fusion 2024, 1, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).